Female Icons is a multifaceted project by the artist group known as De Geuzen. Riek Sijbring, Femke Snelting, and Renee Turner are the primary members, and have been making work together under the De Geuzen identity since 1996.

In their FAQs, they state that their name is, “A Dutch term for a negative or derogatory name appropriated and reclaimed as a positive label of empowerment,” which bears an interesting relationship to the Female Icons project.

Female icons includes workshops, an online archive of images and tags, a user-generated collection of photos, and other generative events that the group hosts at events and festivals.

On the project’s website, each icon added to the site has her portrait added to the grid of oval images in the background of the page. When you click on an icon, you are taken to that page for that woman. There, the picture has a set of tags associated with it, and as you mouse-over the icon you have chosen, you can click on any of the tags, and see all the icons associated with that characteristic (i.e., ‘writing’ or ‘radical’). There is a tag cloud on the project homepage, showing ‘strength’ as the most popular trait as of mid-September. If instead of clicking a tag you click directly on the icon, you are redirected to a Google image search of that person.

![]()

The aesthetic of this project’s archive reinforces the idea that an icon or representation is in itself a way of seeing. Seeing the symmetrical grid of images almost evoke a sense of uniformity – they are all of the same size but with radically different contents. De Geuzen does not shy away from the way in which we form collections and stories in the present in an attempt to understand the continuity of what it means to be female through acts of collection, homogenization, discussion, and disambiguation. This provides us with a collective means for seeing the female throughout history, and the resulting collection of hyperlinked media provides a way to draw comparisons and inferences that aren’t always as available when we study a singular biography.

The interesting thing about exploring this project was determining what I thought the mission of the project to be. I wondered what kinds of questions it was asking, and what it was seeking to embody as an endeavor. I initially thought it might be asking the question, What makes an icon an icon? or What makes a female an icon? But as I looked into the project, it didn’t seem that it was seeking to deconstruct the status of the ‘icon’, or to separate a public view of women from private ones. Rather, I think it is taking the icon as a given – embracing the idea that an image and a status exist together – and builds a network of expressions and testimonies on top of this evidential notion. De Geuzen is letting the research, images, and lectures of the Female Icon project reveal something about our social histories. They state that they wish to show the “social underpinnings of the feminine in all its cliche’s, perversities and conventions.” In other words, I think they may be trying to excavate the range of meanings of a recognized ‘icon’ by forming a network of them and letting the emergent dialogue speak for itself.

The tagline for the project, “it’s not the gaze, but the look”, embodies the notion that iconography is in fact, as the term literary means, ‘image writing’. Images perhaps speak more directly than academic vocabularies tend to, and allow us to confront category, characteristic, and aesthetic.

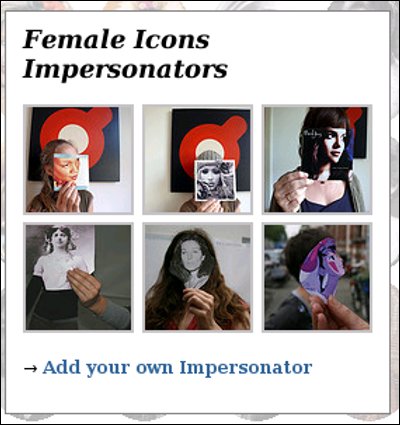

In a sense, they have used the conciseness of the ‘icon’ to build an interactive network of involvement, patterns, and knowledge. Perhaps the most important aspects of the project are the user-contributed images and artifacts. The project asks outside users to take their own picture with the cutout face of an icon of their own, and post the results to their Flickr pool. These images within images signify the heart of the project – that the icon is worn in the present, and we decide how they are preserved and projected, how they ‘look’. Icons express the social and personal distinctions and values that we as a social entity apply to the past at any given moment – the icons present a way to reverse-engineer our present moment. They reveal the nature of our appearance, rather than dwell on analyses of how we are seen.

To me this project shows that thinking about appearance through networked definitions is more empowering than defining ourselves through the gaze that is upon us. History becomes something we put in front of us, rather than something we look back on. In a way, when I looked at the collection of photos, I did not immediately think of women’s issues or controversies – I simply felt the collective images speaking for a group of individuals choosing what makes a female an icon to them. In turn, we get a glimpse of how we all are constructed by the achievements of others.

The ways in which history and its archives help us to define biography have changed with the availability of images and information. The Female Icons project recognizes this milieu of material as our contemporary toolbox for understanding complex and dynamic notions, such as ‘the feminine’.

De Geuzen shows with this media-based project that icons can be used side-by-side (it’s not everyday that we see Paris Hilton in proximity to Judith Butler!), collectively, and distributed among many women, and expose patterns that speak to larger stories and timelines when linked together. Since society does the work of bringing forth the icon, we can use tools of media to think about what is means to us as to why they exist in the way that they do.