As a Furtherfield intern, I recently began a research project to find and investigate net.art originating from Asian countries. Coming from an Asian background myself, I thought it would be worthwhile to explore the field in hopes of making some self-reflexive connections. Before undergoing my research, it was clear that such net.artists are quite under-represented – even less-so than the “traditional,” Western net.artists like the Heath Buntings and Olia Lialinas of the digital world. But it was exactly this lack of representation that made the search even more compelling.

However, after nearly a month of research, I came to the conclusion that Asian net.artists are virtually impossible to find. The few that I kept running into during Internet searches were the net.art heavyweights – groups like Young Chae-Heavy Industries or Soiizen Art Labs. I wondered where the underdog was hiding. I was looking for the under-represented, the under-exposed, perhaps an underground, grassroots art community that needed to get their message out. All I found were dozens of broken hyper-links and unfortunately, websites with potential that were in languages I couldn’t understand.

Feeling quite defeated and frustrated, I realized that this blind spot in net.art might have something to do with me being based in the UK, where I am unable to take to the streets and explore word-of-mouth recommendations. There was also the possibility, and this was a complete assumption, that certain Asian countries such as the Philippines (my personal ethnicity), are culturally less likely to make net.art for its original purposes – as a method of social change or political/philosophical discourse, or to crack and manipulate the digital cipher. Artists in poorer countries like the Philippines seem to be largely more concerned with commercially orientated art – graphic design and animation for marketing and advertising industries. This was the type of work that was easily accessible. Thus, I was quite unsuccessful in gathering a list of what I deemed profound Asian net.art sources that weren’t already being picked up by the radar.

Just when I thought I was hitting a roadblock, my colleagues at Furtherfield suggested that I broaden my research requirements, to search within what I already knew was available. What I came up with was a compromise between the two worlds of Asian art and Internet-based work. The result was an investigation on the concept of identity within these works. These works are not necessarily net.art in the traditional sense, but they have two things in common – they are by Asian artists and they explore the concept of identity through digital means on the Internet.

Virtual Identity – CJ Yeh (Taiwan)

“Where a human is reduced to data, data is converted to values, values are transformed into art.” – CJ Yeh, myData=myMondrian 2004

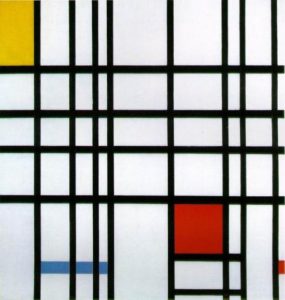

In 2004, Taiwanese artist CJ Yeh created several digital interfaces known as The Equals Series, in which the participants input personal data in order to produce modernist-style artworks that are aural, visual or both. The Equals Series explores the ideas of taking fragmented personal computer data and using it to create artworks that mimic styles of modernist greats, such as Jackson Pollock and Piet Mondrian. New York Arts Magazine described Yeh’s work as a combination of “the principals of painting with the programming of the digital image.” Essentially, the works represent a merging of old and new styles, coupled with the uniqueness of personalized mathematical data.

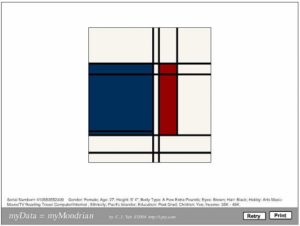

One work of The Equals Series, called myData=myMondrian, transforms basic personal data into a digital painting modeled after Piet Mondrian’s modernist style – straight, horizontal and vertical lines forming blocks of white space and primary colors. Upon launching the interface, users are prompted to fill out a digital survey form that asks for basic information; such as age, height, weight, education level and ethnicity. After submitting the form, the data is then transformed into a mathematical code to generate a visual rendering of a Mondrian-like painting. As Yeh said himself, the human is reduced to data, which is then reduced to values, and transformed into works of visual art.

The rendering takes a similar form to Piet Mondrian’s compositions. Although the screenshot above is missing the color yellow, it is because the data transformed does not call for that particular color. In a way, myData=myMondrian plays on the idea of personal identity. Someone who answers the survey form differently will have a different visual result. Therefore, the artwork is completely personalized by the user – and is made possible solely from the capabilities of the Internet.

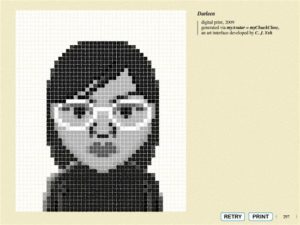

In another of the series works, titled myAvatar=myChuckClose, the participant works from an interface that looks much like the avatar interface of the Nintendo Wii gaming console. The user chooses from sets of basic head and body shapes, gender, skin color, hair, eyes, etc. After the user is finished creating his or her avatar, the image is transformed into a digital print mimicking the portraiture style of American artist Chuck Close – a fragmented photo-realist painting of the head and shoulders.

In contrast to myData=myMondrian, this work in The Equals Series takes an even more visually personal approach to identity. From the very beginning of the process, the participant is able to choose exactly which elements to include in the portrait. The ending result in myAvatar=myChuckClose comes as less of a surprise, as opposed to the other works in the series, which have more abstract results.

The rest of the artworks in Yeh’s Equals Series are similarly lighthearted. There are a total of five, including myParticipation=myMagritte (which utilizes a viewer’s movement in front of a webcam to trigger a work based on Rene Magritte’s The False Mirror) and myBirthday=myPhillipGlass (a computer program that generates musical compositions based on a user’s birthdate). In myTune=myPollock, the computer keyboard is used like an electric piano. While sounds are generated through pressing the various buttons, “splatters” of paint appear on the canvas. A Pollock-style composition is generated right on the screen according to the note, octave and the tempo in which the viewer plays the keys.

Each of the works in The Equals Series is significantly user-friendly. Upon launching each project, participation is self-explanatory, making the works easy to use. The works take an interesting approach on how virtual identity can be manipulated – while they may lack more profound messages and lean towards aesthetically “fun” results, Internet users are able to explore how personal portraits can take less-traditional forms. Although the artwork being generated through these interfaces are more or less established styles, today’s participants are able to express themselves in ways that were once reserved only to the muses of these artists. The Equals Series gives the audience a chance to be hands-on, and to customize and evaluate their own digital portraits for their own pleasure or reflection.

Racial Identity – Dyske Suematsu (Japan)

“Remember, we are not here to make a statement; it’s a question.”

-Dyske Suematsu, All Look Same, 2001-2009

In the ongoing artwork All Look Same, Japanese artist Dyske Suematsu poses a question regarding racial identity. He explores the way Asians are sometimes socially stereotyped by their facial characteristics or cultural traditions – such as architecture or food – and it offers us a way to test our knowledge on how to tell different Asian nationalities apart. The purpose of the work is less offensive than it sounds, and more so serves to provoke thoughts on how Asian nationalities are categorized throughout the western world. It can also be seen as a work attempting to dispel certain misnomers about Asian cultures.

All Look Same is presented to the user in the form of a digital exam room that holds a total of eight quizzes, where users can test their knowledge about various Asian cultural elements. In the first exam, different faces are displayed on the screen, where users are to choose from a multiple-choice menu of Chinese, Japanese and Korean. All the people in the photographs are residents of New York City, but are of 100% pure Asian descent. At the end of the exam, the correct answers are given to the test-taker for comparison, and the results are quite thought-provoking when a participant realizes he or she has used certain stereotypes to answer the questions.

The other seven exams in All Look Same involve Asian art, architecture, landscapes, urban scenery, food and decorative patterns. The artwork as a whole examines elements that are often thought of as easy to differentiate, but in fact, the results are often quite the opposite.

Based on average test results, which are given at the end of each exam, test-takers are generally bad at telling the difference between Chinese, Japanese and Korean characteristics. But the work does not mean to be taken as a way of calling people out on their lack of familiarity with Asian cultures. Suematsu writes on his website:

“I’ve always thought that it was one of those urban myths that you can tell different Asians apart. Especially if I can’t see what they are wearing, I don’t think that I can tell them apart. And, I’m an Asian myself. I’ve been living in the US for over 15 years and I’ve heard some people tell me I definitely look Japanese, while others thought that I don’t at all. Some people boastfully claim that they can tell the difference no problem, while others quietly admit that they can’t. Even with those who claim they can, is it really true that they can? Maybe there is something to be said about someone saying ‘You guys all look the same!’ Or, maybe they just don’t know any better. This site, therefore, is a way for me to demystify this issue once and for all.”

Like Suematsu said before, All Look Same is not trying to make a statement. It’s asking a question – is it really possible to tell the difference? And should Asians take offense when someone can’t tell the difference?