In partnership with AntiUniversity

Whether you smelt it, mine it, burn it, breathe it, or shove it up your ass the result is the same: addiction.

Addiction is defined as a chronic, relapsing earthly disease that is characterized by compulsive seeking and use of earth products, despite harmful consequences. It is considered a brain disease because humankind changes the earth—they change its structure and how it works.

Soft Sickness is a one evening/one day workshop hosted by the research project Shift Register exploring the signs, symptoms, circulations, exchanges, consumptions, dependencies, and management implicit in the multifarious and pathological dependence on the earth which is now named by that word “Anthropocene”. Earthly addictions produce quantified-earth self-portraiture, GIS co-dependencies, and all other variants of planetary narcissism. Earth-scale sensor systems and media networks, swathing the planet in information about itself, are unveiled with media from on- and off-planet earth science field-stations and reflections thereupon. Dependencies bring anxieties about the impending doom of resource dearths to come. People manage these anxieties with new psychotropic medications, whereas artists represent and markets bet on them, against the health of the earth and its living bodies.

Soft Sickness divines the earth lines of the often contradictory ingestion of and repeating addiction to the earth and its productions, data, memory — its circulations, seasons and natures, to the plants, the mushrooms and the animals, to fossil fuels, metals, to liquid screens and smogged surfaces, to longevity and, finally, to the real. To the thing and things which we cannot help doing (things to). To compulsively consume (the earth) is to eat and subsequently to excrete ourselves, humankind, and this cycle can be termed addiction. We feed from the earth, feeding back to the earth a world and mind-changing chemistry.

During the workshop, participants and invited guests will discuss, map, extract, ingest and excrete relations of local earth manifested in Finsbury Park in North London. Plant and pharmaceutical toxicities/ psycho-pharmacologies, poison cures, geophagic gastronomics, esoteric pollution sensing and embrace, and the invention and embedding of folkloric and human to non-human ecologies constitute parts of this invitation. We will gather psycho-active dew, imagine tales for the mole people, bake bread for crows, and make the earthworlds flesh.

We wish to develop contemporary rituals articulating the polarised and overgrown junk-tions of shamanic spirit journeyings with addiction managements; cold kicking the earth habit or indulging absolutely in the (cannibal/capital) undergrounds and (fairie) overgrounds.

SHIFT REGISTER is a research project investigating how technological and infrastructural activities have made Earth into a planetary laboratory. The project maps and activates local dynamics and material shifts between human, earthly and planetary bodies and temporalities. Contemporary, mainstream science and technology are intersected with other knowledge systems to attempt a reconfiguration of relations between humans and the earth. SHIFT REGISTER is Jamie Allen, Martin Howse, Merle Ibach, Jonathan Kemp and Martin Sulzer at the Critical Media Lab, Basel.

Through our interactions with digital devices and systems us humans are now a diverse resource to other humans and machines. And we are changing in accordance with the processes and demands of contemporary, technological market systems, designed to extract as much data from us as possible. In his recent article Our minds can be hijacked, Paul Lewis of the Guardian revealed that those in the know, those who helped to create Google, Twitter and Facebook, are now disconnecting themselves from the Internet as, like millions of people in the world, they are feeling the effects of addiction to social networking platforms, and fear its wider consequences to society.

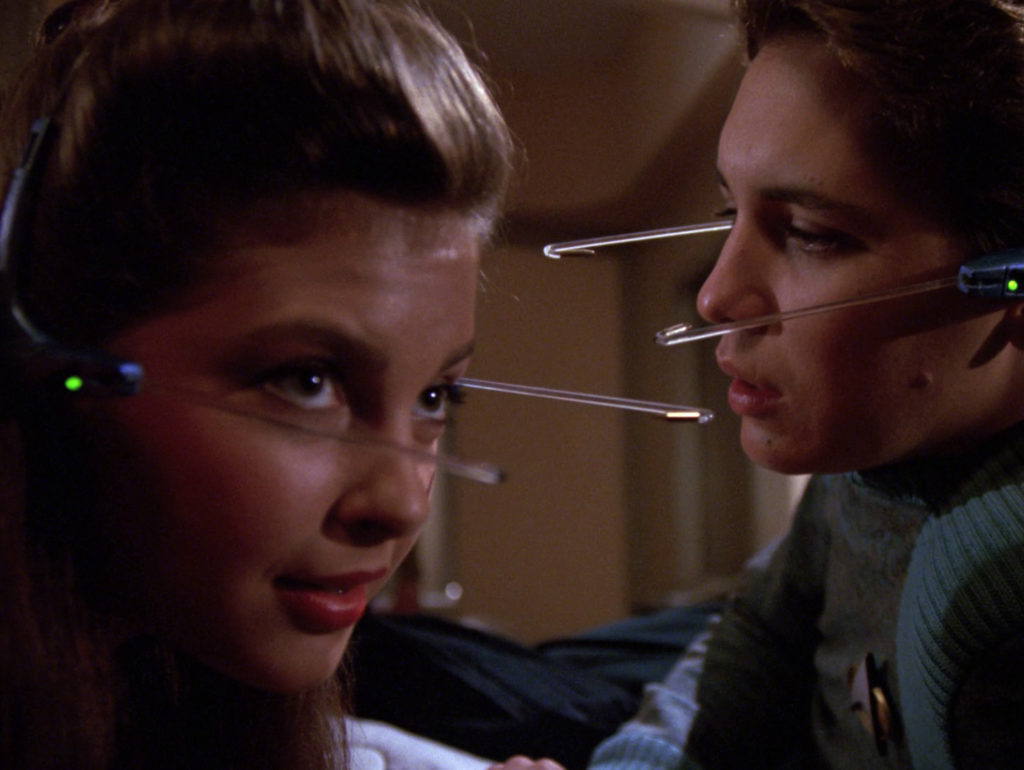

The hazards of this kind of tech-contagion have been the staple food of sci-fi for decades – a mysterious woman shares a strange but simple VR game in the 1991 episode of Next Generation Star Trek, The Game. It spreads like wildfire, taken up with enthusiasm by the crew, only later revealed to be a brainwashing tool invented by an alien captain to seize control of first the ship, and then all of Starfleet. Let’s look at ourselves for a moment – if we can tear our gaze away from our screens. How has our public behaviour changed – on the streets, on public transport, in buildings and parks? Our attention transfixed by our devices, online via our phones and tablets – bumping into each other, and even walking into the road endangering their own and others’ lives.

Professor of psychology Jean M. Twenge studies post-millennials and argues that a whole younger generation in the US, would rather stay in doors than going out and partying. Even though they are generally safer from material harm they are on the brink of a mass mental-health crisis. She says this dramatic shift in social behavior emerged at exactly the moment when the proportion of Americans who owned a smartphone surpassed 50 percent. Twenge has termed those born between 1995 and 2012, as generation iGen. With no memory of a time before the Internet, they grew up constantly using smartphones and having Instagram accounts. In her article Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation? Twenge writes “Rates of teen depression and suicide have skyrocketed since 2011. It’s not an exaggeration to describe iGen as being on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades. Much of this deterioration can be traced to their phones.”

Internet addiction is like having your head perpetually inside a magical mirror of hypnotically disembodying power #addictsnow pic.twitter.com/DFkl1jaKER

— furtherfield (@furtherfield) August 31, 2017

From the #addictsnow Twitter commission by Charlotte Webb and Conor Rigby, 2017

We offer three features as part of Furtherfield’s 2017 Autumn editorial theme of digital addiction, in parallel with the exhibition Are We All Addicts Now? at the Furtherfield Gallery, until 12th November 2017. Artist Katriona Beales has developed the exhibition and events programme in collaboration with artist-curator Fiona MacDonald: Feral Practice, clinical psychiatrist Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones, and curator Vanessa Bartlett. She explores the seductive qualities, and the effects of our everyday digital experiences. Beales suggests that in succumbing to on-line behavioural norms we emerge as ‘perfect capitalist subjects’ informing new designs, driving endless circulation, and the monetisation of our every swipe, click and tap.

Firstly we present this interview with Katriona Beales* from the new book Digital Dependence (eds Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones, 2017) in which she discusses her work and her research into the psychology of variable reward, “one of the most powerful tools that companies use to hook users… levels of dopamine surge when the brain is expecting a reward. Introducing variability multiplies the effect” and creates a frenzied hunting state of being.

Pioneer of networked performance art, Annie Abrahams, creates ‘situations’ on the Internet that “reveal messy and sloppy sides of human behaviour” in order to awaken us to the reality of our networked condition. In this interview, Abrahams reflects on the limits and potentials of art and human agency in the context of increased global automation.

Finally a delicious prose-poem-hex from artist and poet Francesca da Rimini (aka doll yoko, GashGirl, liquid_nation, Fury) who traces a timeline of network seduction, imaginative production and addictive spaces from early Muds and Moos.

“once upon a time . . .

or . . .

in the beginning . . .

the islands in the net were fewer, but people and platforms enough

for telepathy far-sight spooky entanglement

seduction of, and over, command line interfaces

it felt lawless

and moreish

“

And a final recommendation – The Glass Room, curated by Tactical Tech

Tactical Tech are in London until November 12 with The Glass Room, exhibition and events programme. A fake Apple Store at 69-71 Charing Cross Road, operates as a Trojan horse for radical art about the politics of data and offers an insight into the many ways in which we are seduced into surrendering our data. “At the Data Detox Bar, our trained Ingeniuses are on hand to reveal the intimate details of your current ‘data bloat’; who capitalises on it; and the simple steps to a lighter data count.”

*This interview is published with permission from the publishers of the book Digital Dependence edited by Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones, available to purchase from the LUP website here.

The interview is taken from the recently published book Are We All Addicts Now? Digital Dependence edited by Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones, Liverpool University Press, 2017, and published with permission from the publisher. Available from the LUP website here – the interview is published in parallel with the exhibition Are We All Addicts Now? at the Furtherfield Gallery, London 16 September – 12 November 2017.

Ruth Catlow: In your exhibition Are We All Addicts Now? That opens at Furtherfield, Autumn 2017. You will be presenting a number of works and installations made in response to your research into online addictions. What prompted your interest in this matter?

Katriona Beales: I have insomnia on and off — like a lot of precarious workers. And to deal with being awake for long-stretches at night I go online, parse hundreds of hyperlinks, images, videos. It’s like an out of body experience: I detach, temporarily, from anxieties, pressure, claustrophobia via total preoccupation. Reflecting on these experiences caused me to question whether there was something inherently ‘addictive’ about the conditions of the digital. My research has developed to look at the burgeoning field of neuromarketing and how much online content is ‘designed for addiction’ (to borrow the title of Natasha Dow Schüll’s scorching analysis of machine gambling in Las Vegas). [

note]Natasha Dow Schüll, Addiction By Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).[/note] 1] Gamification strategies and various psychological techniques such as variable reward (originally employed in the casino) are now utilised to mass effect on social media platforms, search engines, email accounts, and news sites.

RC: Can you give us an example of digital content, an interface or a device that you personally experience as addictive?

KB: I find the infinite scroll function on sites like Instagram and Twitter very compulsive. It removes the natural breaks that are built into technologies like the book, with chapters starting and ending. Then again, I used to be a compulsive reader and now I am a compulsive scroller… But I keep circling back round to think about the specific qualities of the conditions of the digital. The infinite, hyperlinked and networked nature of online content means scrolling, scrolling, scrolling never needs to end. There is also a correlation between these repetitive physical actions and meditative type states.

RC: Yes, this connects with theories of flow employed in game design. The idea is to design activities that produce the fulfilling feelings of focus, and to minimise a questioning of the context or frame of play. And there is very little critical discussion in mainstream culture about the gamification of everything, which replaces individual agency with a kind of soft coercion. It’s problematic because the less we notice how our attention and experiences are being harnessed by external forces (commercial or state based), the harder it is to connect and collaborate with others outside the given frames.

KB: Totally. I like your phrase ‘soft coercion’ because I think that sums up nicely what I’ve found troubling. Take this quote from Nir Eyal: “Variable schedules of reward are one of the most powerful tools that companies use to hook users… levels of dopamine surge when the brain is expecting a reward. Introducing variability multiplies the effect, creating a frenzied hunting state… When Barbra lands on Pinterest, not only does she see the image she intended to find, but she’s also served a multitude of other glittering objects… Before she knows it, she’s spent 45 minutes scrolling.” [2]

RC: We initially had reservations about applying the concept of addiction to internet usage, partly because the addiction label is usually used to attach blame to individuals. However, after conversation it became clear that you are exploring a political question. Why is the concept of addiction important to you?

KB: Too much discussion about addiction is focused on the responsibility of people to help themselves. The fact that many can’t is often seen as a kind of moral failure. There’s also the disputed status of internet addiction in itself as documented by Mark D. Griffiths and his colleagues in their contribution to this book. We can’t pretend that there aren’t lots of people out there experiencing unhealthy and compulsive relationships to their technologies. But what kind of language is most appropriate to define this? What I am interested in is the phenomenon of what could be understood as addictive behaviours (including my own) being normalised in relation to digital devices. Kazys Varnelis [3] describes network culture as demanding connectedness, with power concentrated in nodes of hyper-connectivity. The more views, the more likes, the more power is accrued. Addictive behaviour is both normalised and valorised in late capitalism as it is associated with the public performance of productivity. Whilst these actions appear to be the choice of individuals, how much is due to the influence of mechanisms and systems of control? Ultimately, I am interested in the idea of the addict as a perfect capitalist subject. However, can we/I be both active-users and critical participants? I am concerned about how many of these platforms function as closed systems in which we contribute (without remuneration) our creative and emotional labour and yet can’t shape the conditions in which it is displayed, performed and monetised.

RC: You have collaborated with scientists as well as other artists and curators. How has this worked and what have these collaborations produced?

KB: The space of art offers an opportunity to tap into diverse fields of research, as a kind of (un)informed amateur. I find a Rancièrian strategy of ‘deliberate ignorance’ liberating. As an artist, I find myself in a position where I can turn my lack ofspecialist knowledge in fields like neuroscience into a kind of asset. I’m not answerable to a canon so can make unorthodox connections. In 2012, I started a conversation with clinical psychiatrist Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones. Henrietta is fascinating as she started the first NHS clinic for problem online gambling and is now one of the leading experts in the field of online behavioural addictions. My collaboration with Henrietta has flourished, I think, because there is a recognition that there is a mutual benefit from the conversation but not an ownership or entitlement to each other’s outcomes.

RC: How does your work deal with the relation between physical and virtual presence?

KB: I am a tactile person, the sort who goes into a shop and strokes things with their face. I am fascinated by how digital devices act as portals into virtual worlds but often their own physicality isn’t dwelt on. Yet these devices connect us in a very tangible way to a globalised workforce and unethical labour practices. My iPhone has parts in it that were constructed by hand in an environment that resembles the Victorian workhouse more than the shiny aesthetics of the Apple store. These deeply dystopian factories create objects that seem so sleek, so smooth, so modern, as if they’ve arrived whole from outer-space. But they were created by workers who do compulsory over-time, sleep in triple bunk beds in small dorm rooms and aren’t even allowed to kill themselves. (I’m specifically referencing the suicide prevention netting that Foxconn put up around their buildings after a spate of mass suicides.)1 I’m emphasising physicality to connect my body lying in my bed to the body of someone bent over a production line; it is far too easy to dismiss the impact of our insatiable appetite for electronic goods.

RC: Your exhibition at Furtherfield is to be sited in the heart of a public park. How are you thinking about the relationship of digital devices to the natural environment?

KB: I continue using my smartphone when I step inside the park gates, in a continuum of ongoing augmented experiences where my physical environments are overlaid with digital content. The park acts as a fulcrum for changing understandings of leisure as labour, labour as leisure, and is the perfect site for encouraging reflection on this relationship. As part of this, Fiona MacDonald, who has been working with me on Are We All Addicts Now? as both a curator and an artist, is developing a mycorrhizal meditation piece, looking at network culture from an organic non-human perspective.

RC: I’d like to end with a description of some of the artworks and installations you are making, the materials you are using, and, in the context of the un-ideal strategies used by designers of mobile interfaces, what condition do you aspire to cultivate in visitors to your exhibition?

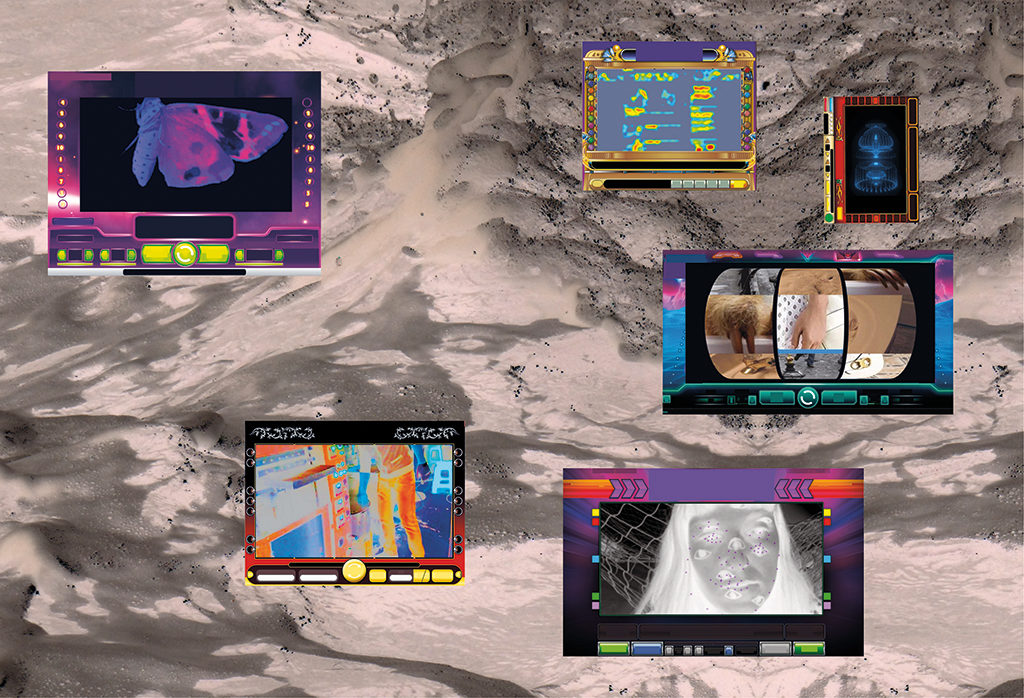

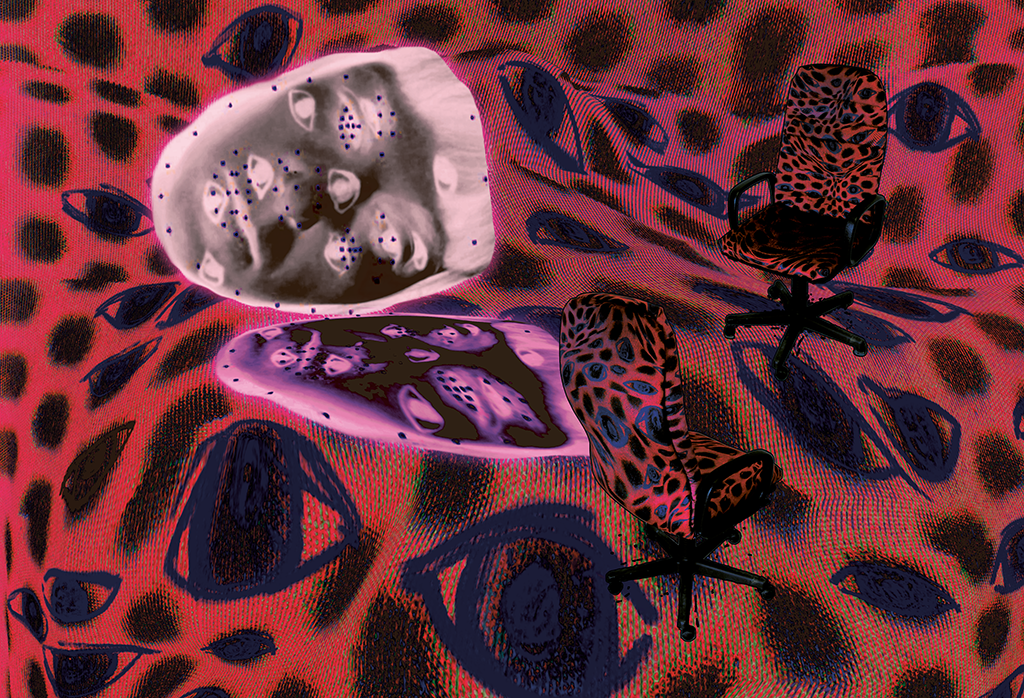

KB: I’m making a sunken plunge pool of a networked nest-bed, with glowing screens on which moths flutter embedded in glass orbs. Bed hangings embroidered with dichroic screens stripped from smartphones shimmer overhead, iridescent in the reflected light. I’m trying to communicate how seductive I find the screen in that dark, warm space – in those moments when I am more intimate with my device than my partner. There will be some participatory sculptures referencing pachinko and prayer beads, rhythmic movement, trance-like repetition, lulled into endless hypermobility in the closed systems of ‘communicative capitalism’. [5] I’m also working on some moving image works in which makeup is used as a tool to undermine eye tracking software, which I am hoping will incorporate some specialist hardware generating a live-feed of eye-tracking data from audience members. A series of table-top glass sculptures and embedded screens will explore interfaces that are ‘designed for addiction’ and the way notifications, for instance, are neuromarketing strategies seeking to ‘awaken stress — the mother of all emotions.’ [6] I’d like the audience to share in my disquiet, and hopefully leave encouraged to engage more critically with shaping their online worlds.

‘We had a dream last night, we had the same dream'[1]

I’m looking for a new love, a mouth that promises . . .

once upon a time . . .

or . . .

in the beginning . . .

the islands in the net were fewer, but people and platforms enough

for telepathy far-sight spooky entanglement

seduction of, and over, command line interfaces

it felt lawless

and moreish

wandering into the maw of the feast

in the realm of the Puppet Mistress, 1995

speech acts, sex acts, strange pacts

squirreled away in buffer logs and pasted Pine trails

weaving 1001 nights of Puppet Mistress tales

never on the down-low

was this most splendid DIWO

permission granted,

always, all ways

read write execute

reeds rites hexecutes

I was Alice clasping the little bottle labeled ‘DRINK ME’

becoming-Sufi, heady with some love-like like love emotions

juiced up jouissance

psychosomatic investigations

psi psi psi

ψ ψ ψ

sigh

seeking the difference/s

if any

between a suspected false binary

Virtual — Real — Life

difference

différance

different ants

worker queens snorting lines of flight

‘IRL’ (‘in real life’) prefaced conversations

whereas no-one said ‘IVL’

VL was the norm

so no need for a distinguishing preposition

whereas you needed to go somewhere, in, purposefully,

to get (back) to real life

Back to life, back to reality

Back to the here and now yeah

. . .

Back to life, back to the present time,

Back from a fantasy

Soul II Soul 1989

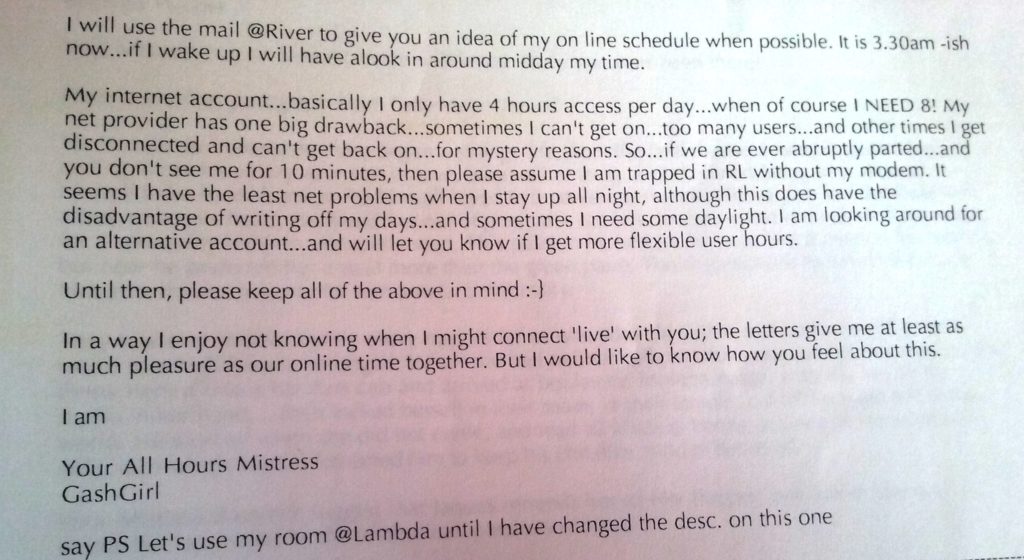

I ask Monstrous_Gorgeous (aka t0xic_honey @Lambda) to trawl through my stash of Moologs and MOOmails from my Lambda life, to search for signs of digital affliction. t0x’s forensic gaze (who eirself had been a keen Lambda queercoder back in the day) might be illuminating. GashGirl and her morphs(GenderFuckMeBaby, Madame_de_Clairwill, doll yoko, Rent_Boy, et al) had run amok and amongst simultaneous games, switching genders, personae and communicative registers as easily as children playing ‘let’s pretend‘. The best game was that between Puppet Mistress and her Puppet (aka YourPuppet). Today the language seems quaint, The Difference Engine meets The Pearl, steamy stream punk. All bonnets, bronze and tiny buttons.

Wolf.

Homunculus.

Ghost.

Doll.

It’s a sky-blue sky.

Satellites are out tonight.

Let X=X.

Laurie Anderson 1982

does X=X?

or VL = zero?

with RL the one of ones, the one and all,

the only one (of all possible lives)

I think not!

t0x phones me, recounting episodes that I cannot recall, but which are so in-character I have for sure they happened. Like when I punished My Puppet severely for daring to speak with t0x about her in-MOO peep show. Now we can laugh about it, now that the field lies fallow, but at the time I was furious. Living at (on? in?) LambdaMOO did not diminish affect or emotion, but rather it intensified thought, sensation, desire, need.

can we call this addiction?

or obsession?

compulsion maybe?

I chatted this week with Jon Marshall, my anthropologist friend and author of Living on Cybermind (an ethnography of a mailing list), about how it felt more like a habit than an addiction. He talks about personally accumulated habits and socially accumulated habits. Humans are constructed of habits, including the habits that you build up around internet use. We recall the ‘Rape in Cyberspace‘ event at LambdaMOO; ‘that story becomes a myth that guides behaviour’, suggests Jon. My habit would not have led to such intense encounters, if all of us lot had not been sharing a gravitational pull to the glimmering galaxies of spiralspace. My twin talks about habit lying at the junction of nature and nurture, opening up another line for future investigation. Never enough time. Instead I loaf around on Netflix with Terrace House: Boys & Girls in the City.

for me the habit of MOO (Mu) was quickly formed,

and devastating to desert

Ripping through a damaged heart

in the best of daze

circa 1992 93 94 95 96

(=3)

I didn’t leave home

a charming house with a white peach tree, goblin hut

and a dial-up 14,400 modem usurping landline’s phone functionality

for years I burrowed in through a borrowed log-in

J (aka connie_spiros @Lambda) pounds on front door to kick me off

later I jumped onto a free account offered by community provider apana

through its tiny sibling sysx (thank you Scott and Jason)

part of a tribe meshwork of cool sysops animating .net

motivated by the conviction of net access for all

xs4all

excess for real

S (aka Quark @Lambda) told me how depressing it was to leave home at 7.30am seeing me already jacked in, and to find me still in pajamas at dinner time, a sure sign that I hadn’t stepped away from the computer all day.

frequently he’d say ‘What’s wrong with this picture?’

(rhetorical)

5 words yanking me from my fugue

to discover myself pretzeled around the machine

in a position so unnatural it had become natural

to a life lived more and more in a VL that had become my RL

there was a vastness to the generative affective experiences

it felt unstoppable

on par with the most exhilarating love affairs

continual platform jumping

(don’t mind the gaps)

with unseen but deeply imagined companions

haunting me from nautical twilight to nautical twilight

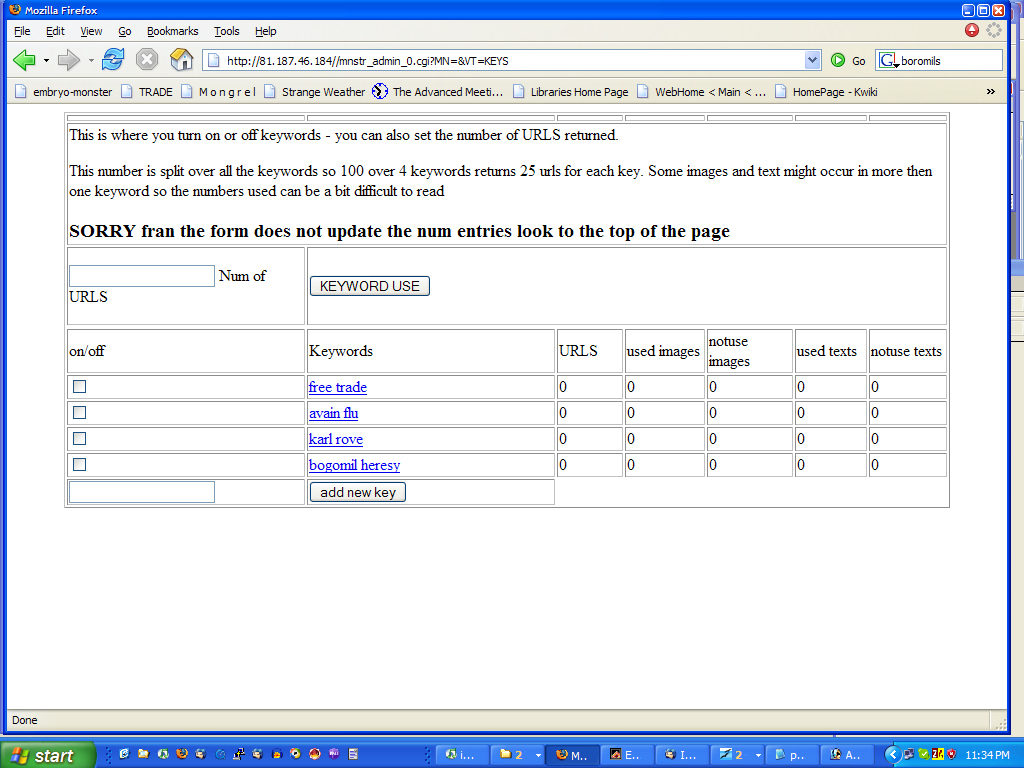

netmonster, 2005

The only platform that came close to the seductiveness of Lambda was Netmonster, a network visualisation engine built by artist coder tinkerer Harwood (aka Graham Harwood). I was fascinated by the code and what it could do. And I adored the constant communication with my bruvv, the one who calls me ‘witch sister’. We hung around on the server, chatting white text on black screen. I made him a self-executing poem in Perl, my one and only attempt to learn some rudiments of that language. Netmonster could be a machine for collaborative writing, for prophesy, a tool for poking around in the machinations of power and capital. I imagined its transformative potential on a magical level, casting silver spanners into the bellyworks of the Beast. As a user I became tangled in search strings questing for the grail of understanding. Without knowing what I was asking, I pushed Harwood to push the code, Perl, to do things it wasn’t designed to do. The machine groaned under the weight of requests, and eventually its interactive functionality was turned off (brutal!), leaving just a beautiful hyperlayered carapace online. The emptiness I felt when the living essence of the project was no longer was comparable to the hole of grief when a lover says it’s over. The spirit of Netmonster had left forever. I was alone again.

clever little tailor, 2017

There’s a few of us chatting around a table in Clever Little Tailor, an affordable bar if you stop after one drink. Around the table S2 (artist/student, early 20s), A (poet/singer/student maybe just grazing 25), and a couple of ancient cyberwitches. We speak about imbuing inanimate objects, a child’s wooden horse, a Persian rug, with magical powers, to speak, to fly. The human tendency to want to create life in things, including things and wings of internet, and this predisposition in turn enlivens and expands us. The topic turns to matters of the heart, and native/natal platforms. Those communicative modes that either we were born into or grew into, the sticky tongue finger techs that we associate with our netted emotional and social lives. We talked about coding and not coding, about the need to live online, and the impulse to desert it. Instant Messaging is for S2 what Internet Relay Chat was for us. We spell out the spell of Command Line Interface in a condensed version of how we uploaded ourselves to the song of the modem, waiting up all night to be able to play, existing betwixt and between multiple time zones. We struggle to find the right words (because the material of this stuff is made of words but is so not about words really) to evoke the deliciousness of what was a relatively uncolonised uncommodified unregulated ineffable space. Even if we hexen rarely use the word ourselves, the neologism (and who could forget Neo!) cyberspace, continues to signify the consensual hallucination of jacking in to the zone. Maybe now it’s more mall than sprawl for us who experienced something more unbounded, but for the next gens the intensities, the desires are equivalent.

17.10.17

forever doll

becoming witch

she opens her mouth

and swallows the world

she opens her mouth

and swallows your word

dissolving like spun sugar

laced with saffron threads

hexe hexe hexe

tiva! tiva! tiva!

naughty naughty naughty

all for naught

and nought for one

zero and one

zeno and won

one on one on one

on and on and on . . .

Thank you to old and new friends whose ideas have nourished this text: Virginia Barratt, Alison Coppe, Linda Dement, Teri Hoskin, Jon Marshall, Stuart Maxted, John Tonkin. Big thanks to (bruvv) Graham Harwood for inviting me to play and live inside Netmonster in 2005.

Francesca da Rimini (aka doll yoko, GashGirl, liquid_nation, Fury) is an interdisciplinary artist, poet and essayist. She revels in collaborative projects, joining companions in generating slow art, strange beats and new personae. As co-founder of cyberfeminist group VNS Matrix she contributed to international critiques of gender and technology. The award-winning dollspace deployed the ghost girl doll yoko to lure web wanderers into a pond of dead girls. As GashGirl/Puppet Mistress, she explored the uploaded erotic imagination of strangers at LambdaMOO. More recent performances , collaborations and installations including delighted by the spectacle, hexecutable, songs for skinwalking the drone, hexing the alien, and lips becoming beaks have combined rule-driven poetry, fugue states, spells and prophesies as hexes against Capital.

“Certain subjects compel me – alchemy, folklore/folk law, emancipatory social experiments, the nature of cognition, and states of ‘madness’ and ecstasy. I approach art-making as a hexing, a spell, a witch’s ladder to another realm. To paraphrase anarchist anthropologist David Graeber, a revolutionary act is to behave as if one were free.” da Rimini