DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

The blockchain is widely heralded as the new internet – another dimension in an ever-faster, ever-more powerful interlocking of ideas, actions and values. Principally the blockchain is a ledger distributed across a large array of machines that enables digital ownership and exchange without a central administering body. Within the arts it has profound implications as both a means of organising and distributing material, and as a new subject and medium for artistic exploration.

This landmark publication brings together a diverse array of artists and researchers engaged with the blockchain, unpacking, critiquing and marking the arrival of it on the cultural landscape for a broad readership across the arts and humanities.

Contributors: César Escudero Andaluz, Jaya Klara Brekke, Theodoros Chiotis, Ami Clarke, Simon Denny, The Design Informatics Research Centre (Edinburgh), Max Dovey, Mat Dryhurst, Primavera De Filippi, Peter Gomes, Elias Haase, Juhee Hahm, Max Hampshire, Kimberley ter Heerdt, Holly Herndon, Helen Kaplinsky, Paul Kolling, Elli Kuru , Nikki Loef, Bjørn Magnhildøen, Rhea Myers, Martín Nadal, Rachel O Dwyer, Edward Picot, Paul Seidler, Hito Steyerl, Surfatial, Lina Theodorou, Pablo Velasco, Ben Vickers, Mark Waugh, Cecilia Wee, and Martin Zeilinger.

Read a review of the book by Regine Debatty for We Make Money Not Art

Read a review of the book by Jess Houlgrave for Medium

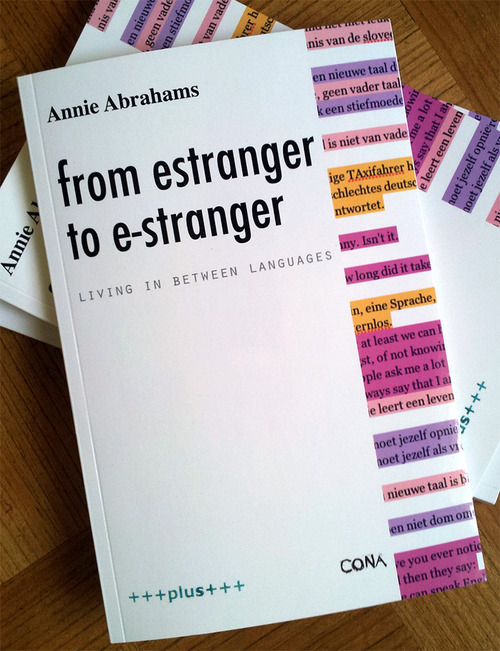

Gretta Louw reviews Abrahams’ book from estranger to e-stranger: Living in between languages, and finds that not only does it demonstrate a brilliant history in performance art, but, it is also a sharp and poetic critique about language and everyday culture.

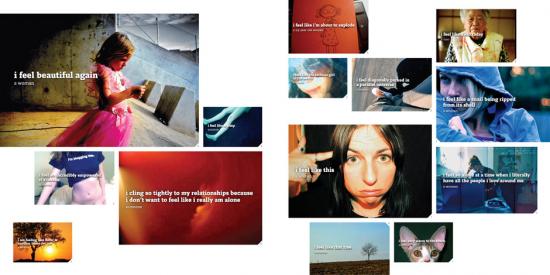

Annie Abrahams is a widely acknowledged pioneer of the networked performance genre. Landmark telematic works like One the Puppet of the Other (2007), performed with Nicolas Frespech and screened live at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, or her online performance series Angry Women have solidified her position as one of the most innovative net performance artists, who looks not just at the technology itself but digs deeper to discover the ways in which it impacts human behaviour and communication. Even in the present moment, when online performativity is gaining considerable traction (consider the buzz around Amalia Ulman’s recent Instagram project, for example), Abrahams’ work feels rather unique. The strategy is one of contradiction; an intimacy or emotionality of concept and content, juxtaposed against – or, more accurately, mediated through – the technical, the digital, the screen and the network to which it is a portal. Her recent work, however, is shifting towards a more direct interpersonal and internal investigation that is to a great extent nevertheless formed by the forces of digitalisation and cultural globalisation.

(E)stranger is the title that Abrahams gave to her research project at CONA in Ljubljana, Slovenia, and which led to the subsequent exhibition, Mie Lahkoo Pomagate? (can you help me?) at Axioma. The project is an examination of the shaky, uncertain terrain of being a foreigner in a new land; the unknowingness and helplessness, when one doesn’t speak the language well or at all. Abrahams approaches this topic from an autobiographical perspective, relating this experiment – a residency about language and foreignness in Slovenia. A country with which she was not familiar and a language that she does not speak – regressing with her childhood and young adulthood experiences of suddenly being, linguistically speaking, a fish out of water. This experience took her back to when she went to high school and realised with a shock that, she spoke a dialect but not the standard Dutch of her classmates, and then this situation arose again later when she moved to France and had to learn French as a young adult.

There are emotional and psychological aspects here that are significant and poignant – and ‘extremely’ often overlooked. The way one speaks and articulates oneself is so often equated with intelligence and authority – and thus the foreigner, the newcomer, the language student, is immediately at a disadvantage in the social hierarchy and power distribution. Then, there are the emotional aspects and characteristics requisite for learning a language; one must be willing to make oneself vulnerable, to make mistakes. This is a drain on energy, strength, and confidence that is rarely if ever acknowledged in the current discourse around the EU, migration, asylum seekers, and – that dangerous word – assimilation. Abrahams lays her own experiences, struggles, and frustrations bare in a completely matter-of-fact way, prompting a re-thinking of these commonly held perceptions and exploring the ways that language pervade seemingly all aspects of thought, self, and relationships.

Of course this theme is all the more acute in a world that is increasingly dominated by if not the actual reality of a complete, coherent, and functioning network, then at least the illusion of one. In a world where, supposedly, we can all communicate with one another, there is increasing pressure to do so. Being connected, being ‘influential’ online, representing and presenting oneself online, branding, image – these are factors that are becoming virtues in and of themselves. Silicon Valley moguls like Mark Zuckerberg have spent the last five or six years carefully constructing a language in which online sharing, openness, and connectivity are aligned explicitly with morality. Just one of the many highly problematic issues that this rhetoric tries to disguise is the inherent imperialism of the entire mainstream web 2.0 movement.

Abrahams’ book from estranger to e-stranger: Living in between languages is the analogue pendant to the blog, e-stranger.tumblr.com, that she began working on as a way to gather and present her research, thoughts, and documentation from performances and experiments during her residency at CONA in April 2014 and beyond. Her musings on, for instance, the effect dubbing films and tv programs from English into the local language, or simply screening the English original – how this seems to impact the population’s general fluency in English – raise significant questions about the globalisation of culture. And the internet is arguably even more influential than tv and cinema were/are because of the way it pervades every aspect of contemporary life.

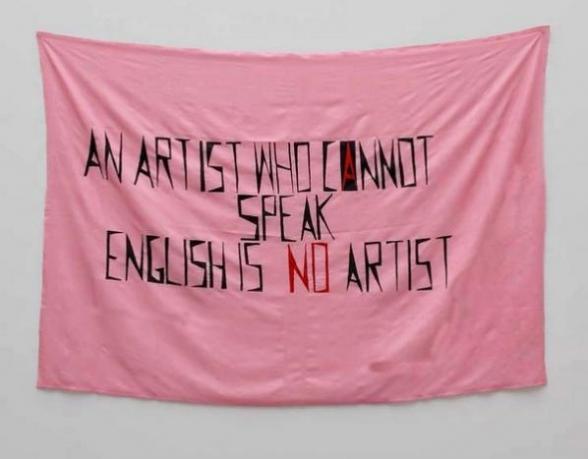

This leads one irrevocably to consider the digital colonialism of today’s internet; the overwhelming dominance of western, northern, mainstream, urban, and mostly english-speaking people/systems/cultural and power structures. [1] Abrahams highlights the way that this bleeds into other areas of work, society, and cultural production, for example, through her citation of Mladen Stilinovic’s piece An Artist Who Cannot Speak English is No Artist (1994). In a recent blog post, Abrahams further reveals the systematic inequity of linguistic imperialism and (usually English speakers’) monolingualism, when she delves into the language politics of the EU and its diplomacy and parliament [http://e-stranger.tumblr.com/post/139842799561/europe-language-politics-policy].

from estranger to e-stranger is an almost dadaist, associative, yet powerful interrogation of the accepted wisdoms, the supposed logic of language, and the power structures that it is routinely co-opted into enforcing. It is a consciously political act that Abrahams publishes her sometimes scattered text snippets – at turns associative or dissociative – in a wild mix of languages, still mostly English, but unfiltered, unedited, imperfect. A rebellion against the lengths to which non-native speakers are expected to go to disguise their linguistic idiosyncrasies (lest these imperfections be perceived as the result of imperfect thinking, logic, intelligence). And yet there is an ambivalence in Abrahams’ intimations about the internet that reflect the true complexity of this cultural and technological phenomena of digitalisation. Reading the book, one feels a keen criticism that is justifiably being levelled at the utopian web 2.0 rhetoric of democratisation, connection etc, but there are also moments of, perhaps, idealism, as when Abrahams asks “Is the internet my mother of tongues? a place where we are all nomads, where being a stranger to the other is the status quo.”

Abrahams’ project is timely, especially now that we are all (supposedly) living in an infinitely connected, post-cultural/post-national, online society, we are literally “living between languages”. The book is an excellent resource, because it is not a coherent, textual presentation of a thesis; of one way of thinking. It is, like the true face of the internet, a collection, a sample, of various thoughts, opinions, ideas, and examples from the past. One can read from estranger to e-stranger cover to cover, but even better is to dip in and out, and or to follow the links and different pages present, and be diverted to read another text that is mentioned, to return, to have an inspiration of one’s own and to follow that. But to keep coming back. There is more than enough food for thought here to sustain repeated readings.

Charlie Gere is a Media Theory and History professor in the Lancaster Institute for Contemporary Arts, Lancaster University. Co-curator of FutureEverybody, the 2012 FutureEverything exhibition in Manchester. In 2007 he co-curated Feedback, a major exhibition on art responsive to instructions, input, or its environment, in Gijon, Northern Spain. He has given talks at many major arts institutions, including the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, the Architectural League in New York, Tate Britain, and Tate Modern. Gere’s new book, Community without Community in Digital Culture (Palgrave MacMillan, 2012), is out now.

Previous titles include: Digital Culture (Reaktion Books, 2002), Art, Time and Technology (Berg, 2006), Non-relational Aesthetics, with Michael Corris (Artwords, 2009). Gere was co-editor of White Heat Cold Logic (MIT Press, 2009), and Art Practice in a Digital Culture (Ashgate, 2010), as well as writing many papers on questions of technology, media and art. He is also co-editing with Robin Boast an anthology entitled Allegories of the Information Age (forthcoming).

Marc Garrett: Digital Culture was originally published in 2002, which happens to be the version I’ve had all these years. In 2008 it was republished, revised and expanded. Now the book has an extra chapter ‘Digital Culture in the Twenty-first Century’. Of course, we already know that digital technology and society has changed dramatically since 2002. So, what themes and historical contexts did you choose, as necessary to include in this new and last chapter?

Charlie Gere: What happened after the first edition’s publication was of course, the rise of so-called Web 2:0, which was simply the greater exploitation of the reciprocal possibilities of the Web. I tried to reflect on how this reciprocity was visible beyond the Web itself and was becoming part of a more general culture of engagement and exchange, not that I share some of the more utopian visions of this phenomenon. Indeed, in my new book Community without Community in Digital Culture, I try to counter the, for me, more naive visions of community in relation to digital technology. I advocate a more ‘non-relational’ approach that does not deny the transformative effects of new media in terms of community but thinks of it more in terms of hospitality to the other.

MG: Many of the artists we have worked with are using new media to explore and critique the utopian assumptions you discuss: YOHA, IOCOSE, Liz Sterry, M.I.G (Men In Grey, Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev), Heath Bunting, Face to facebook (Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico), Annie Abrahams and more. Each of them work in a deeply relational way to intervene in the mythologies projected about digital technology; and, with a knowingly crtical eye of the technical limitations and the social controls at work when using networked technology. At different levels, all are producing work that ‘consciously’ incoporate relational contexts, in some way or another, this includes ideas and approaches with autonomy as part of their art, but not necessarily advocating technology as a singular, saving grace.

How do you view the role of this practice in the context of the wider corporate and state impact on the way technical cultures are evolving. How do you see the notion of hospitality working between the arts and these other more mainstream cultures?

CG: I greatly admire and like the work of the artists you mention and others doing similar things. For me they exemplify the complexity of the idea of hospitality. In general the Web is about exchange, whether that of money for goods, social links and relational exchanges in social networks, or the exchange of speech and dialogue in on-line fora. The work of these artists refuses this demand for exchange and profit within a restricted economy. Thus they are in a sense parasitical on the Web. The word ‘parasite’ comes from ‘para sitos’, meaning ‘beside the grain’, and refers to those animals that take advantage of grain stores to feed. They are the creatures to who must be offered hospitality, as a gift, without expectation of return, which means that while they are bound up with the technological systems that comprise the Web, they are not part of the restricted economy of exchange, profit, and return that is at the heart of capitalism, and to which everything else ends up being subordinated and subsumed. Thus they find an enclave away from total subsumption not outside of the market, but at its technical core.

MG: Many are aware that technology and digital culture have changed the world we live in and appreciate their immediate effects on our everyday behaviours and situations. But there is a bigger story to tell, and history can offer us insightful glimpses, important clues and ways into this story about our relationship with technology and digital culture. One of the arguments outlined in your book ‘Digital Culture’ is that digital culture is neither radical, new nor technologically driven. With this in mind, which past developments do we need to acknowledge and be reminded of and why?

CG: For me the emergence of digital technology is part of a much longer story of abstraction, codification, quantification and mathematisation that can be traced back to numerous points in the history of the West, from Ancient Greece, to early Modernity to the rise of industrial capitalism. Here one might think of Heidegger’s use of ‘cybernetics’, a word we normally associate with post-war computing culture, to describe the technology and calculative enframing of modern society which he traces back to the Ancient Greeks and especially to Plato. I am not a particular advocate of digital technology, and while I appreciate its uses, I also think we must try to be aware of how it determines the way in which we think, and in which we conceive of the world. Above all we should not regard it as merely a conduit to an uncomplicated world simply out there, but rather the means by which a particular world comes to be for us. That said, this is very hard, given that in my view, and to adapt a well-known phrase from Derrida, il n’y a pas de hors-media, there’s no Archimedean point outside of our medial condition, from which we can understand it as from a god’s eye view. ‘Media determine our situation’ as Friedrich Kittler put it.

MG: In Digital Culture, you write about the composer John Cage and how he “has had the most profound influence on our digital culture”, and how his influence has opened up various different avenues of creative engagement. And, many of his ideas on interactivity and multi-media not only “have repercussions in the art world”, but also a strong influence on how computers are used as a medium. Which art movements in particular did he influence and what kind of legacy did he leave for others in relation to computers?

CG: Actually Cage’s influence on those using computers in the arts is probably less to do with what he himself did with such technology and more to do with his use of aleatory methods in many his different projects across many artforms. Also there is something about Cage’s own refusal of a normative Western subjectivity that is also consonant with aspects of our hyper-technologised existence with its emphasis on decentering the individual. Both the refusal of such subjectivity and the aleatory work together to produce a new model of the artist as conduit of contingent social forces rather than protean demi-urge or genius.

MG: Your new book ‘Community without Community in Digital Culture’, has come out at the same time as Geert Lovink’s ‘Networks Without A Cause: A critique of Social Media’. Lovink asks “How do we overcome this paradoxical era of hyped-up individualization that results precisely in the algorithmic outsourcing of the self? How do we determine significance outside of the celebrity paradigm and instead use intelligence to identify what’s at stake?” [1]

Where are your thoughts in regard to Lovink’s question, and does it relate to what you propose in terms of “hospitality to the other?”

CG: I haven’t read Geert’s book, yet at least… But I am highly sympathetic to what I take to be his position. My view is that the Web is part of a broader set of developments that apparently concern relationally, but actually emphasize the sovereign individual and autonomous subject of modernity, as well as promoting spectacular and image-bound forms of presentation and relation. The problem is that one alternative to this individualization is a kind of fascistic identification with the mass, in the form of fusion that negates the individual. A solution maybe to engage with the idea of the other in terms of difference, as both relational and separate, and yet also that which we depend on for our identity in a process of differentiation; thus the idea of hospitality as a reception of the other in difference.

MG: Community without Community in Digital Culture, is a curious title. It proposes contradictory meanings and these contradictions are clearly explained in the introduction. Although, the last sentence says “In this such technologies are part of the history of the death of God, the loss of an overarching metaphysical framework which would bind us together in some form of relation or communion. This can be understood in terms of contingency, which has the same root as contact.”

Could you unpack this last sentence for us, I’m especially interested in what contingency means to you?

CG: I owe my understanding of contingency to the work of philosopher Quentin Meillassoux, whose book After Finitude is causing a stir. Meillassoux is one of a small number of young philosophers sometimes grouped together under the name ‘speculative realism’, mostly because of their shared hostility to what they call ‘Kantian correlationism’, the idea that there can be no subject-independent knowledge of objects. Meillassoux follows the work of David Hume, who questioned the whole notion of causation; how one can demonstrate that, all things being equal, one thing will also cause another. For Hume causation is a question of inductive reasoning, in that we can posit causation on the grounds of previous experience. Meillassoux pushes the implications of Hume’s critique of causation to a point beyond Hume’s own solution, to propose the only necessity is that of contingency, and that everything could be otherwise, or what Meillassoux calls ‘hyperchaos’.

![Community without Community in Digital Culture [Hardcover]. Dr Charlie Gere. Palgrave Macmillan (2012) http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/community-without-community-in-digital-culture-charlie-gere/1110025572 See on Amazon.](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/179510500.jpg)

I use his ideas to think through the implications of the ‘digital’. According to the Oxford English Dictionary ‘digital’ has a number of meanings, including ‘[O]f, pertaining to, using or being a digit’, meaning one of the ‘ten Arabic numerals from 0 to 9, especially when part of a number’, and also ‘designating a computer which operates on date in the form of digits or similar discrete data… Designating or pertaining to a recording in which the original signal is represented by the spacing between pulses rather than by a wave, to make it less susceptible to degradation’ (the word for data in the form of a wave being ‘analog’).

As well as referring to discrete data the dictionary also defines ‘digital’ as ‘[O]f or pertaining to a finger or fingers’ and [R]esembling a finger or the hollow impression made by one’, thus by extension the hand, grasping, touching and so on. Much of the book concerns deconstructing the ‘haptocentric’ implications of contact, and communication, especially in relation to the claims made for social networks, and to engage with what I understand as the relation between ‘contact’ and contingency’. ‘Contingency’ is derived from the Latin con + tangere, to touch. ‘Contingency’ enables us think through the implications of the term digital, by acknowledging both its relation to the hand and touch and also to the openness and blindness to the future that is a concomitant part of our digital culture after the death of God.

MG: What other subjects can we expect to read about in the publication?

CG: Touch in Aristotle and medieval theology, cave painting, mail art, Darwin and Dawkins, Luther Blissett, On Kawara, Frank Stella, Bartleby the Scrivener, Christianity – among other things… oh, and a lot of Derrida.

MG: If there is a message you’d like to send to the world, as it carries on regardless with its “permanent exposure of life, of all lives, to ‘all-out’ control […] thanks to computer technology” [2] (Virilio 2000), and it was printed on a banner, or on a billboard in the streets, what would it be?

I am reading Blanchot at the moment, so perhaps something like ‘the disaster has already happened’ (it’s suitably enigmatic to annoy people).

<———————————- The End (for now) ——————————>

White Heat Cold Logic

British Computer Art 1960-1980

Edited by Pal Brown, Charlie Gere, Nicholas Lambert and Catherine Mason

ISBN 9780262026536

MIT Press 2008

This is the third and last in a series of reviews of the results of the CACHe project. The first review was of the V&A’s show and book “Digital Pioneers“, the second was of Catherine Mason’s “A Computer In The Art Room”. Where “A Computer In The Art Room” concentrated on the history of art computing in British educational institutions up to 1980, “White Heat Cold Logic” gives voice to the individuals who made art using computers in that period more generally.

Charlie Gere’s introduction explains the source of the book’s title, referring to the British Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s famous 1963 speech that a new Britain would be forged in the white heat of the scientific and technological revolution. Gere provides an overview of the history of art computing in the era that may be familiar from “A Computer In The Art Room” which is much needed, for it provides useful context for what follows in this volume. He also argues for the value and interest of the history of art computing, in terms that make it clear for academia.

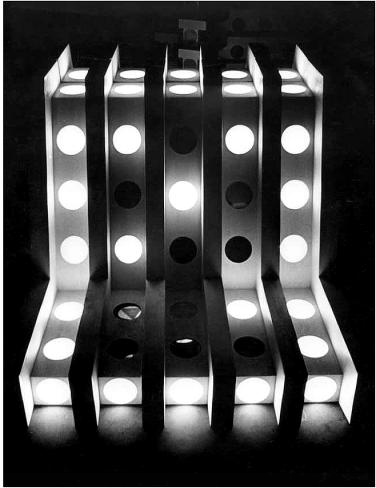

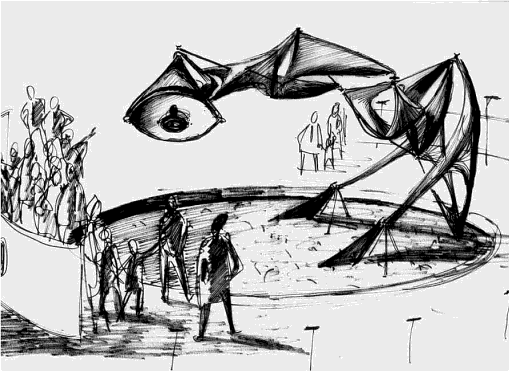

Roy Ascott describes the emergence of pre-computational art informed by cybernetics, systems theory and process against the background of the emergence of “Grounds Course” art education. Adrian Glew documents Stephen Willats’ use of computing in the processes of his art of cybernetic social engagement, the first but not the last more mainstream British artist to appear. John Hamilton Frazer describes the unrealised interactive architecture of the 1960s “Fun Palace” and 1980s “Generator” and of the technology and social legacies of these nonetheless influential projects.

Maria Fernandez puts the figure of Gordon Pask centre stage. As John Lansdown (to whom this book is dedicated) emerged as a major figure behind educational arts computing in “A Computer In The Art Room”. Gordon Pask also emerges in this volume as the cybernetic prophet of the 1960s, mentioned by many in the early essays in this book. His own interactive theatre and robotic mobiles complement his involvement in planning the Fun Palace and as a source of ideas and support for more projects.

Jasia Reichardt provides a theoretical and practical insight into the genesis of her foundational “Cybernetic Serendipity” show at the ICA in 1968 and considers what came next. Brent Macgregor provides an outside view of the same. Neither attempts to mythologize this much mythologized show, the reality of its achievements is more than impressive enough.

Edward Ihnatowicz is the subject of two essays, one with tantalising images of preparatory and documentary material by Aleksandar Zivanovic and an insightful but more personal essay by Richard Ihnatowicz. Hopefully his reputation will continue to increase towards the level it deserves.

Richard Wright follows the ideas of Constructivist art into Systems Theory, which alongside cybernetics is one of the guiding ideas of the art of the period overdue for rediscovery both within art computing and more generally.

Harold Cohen remembers the origins of his “AARON” painting program in a tale of the struggle of art against bureaucracy. Tony Logson’s tale is surprisingly similar, although his systems-based art is very different from Cohen’s cognitively-inspired forms. Simon Ford reveals Gustav Metzger’s involvement with early computer art and with the Computer Arts Society (CAS). CAS also feature large in Alan Sutcliffe’s description of his computer music compositions, one of many essays that left me wishing I could see the code and experience the art as well as reading about it.

George Mallen also touches on CAS, and on Pask’s System Research Ltd. as he explains the art and business of the production of the unprecedented environmentalist interactive multimedia of the “Ecogame”. The Ecogame is one of many works in the book that people simply need to know about. Doron D. Swade makes the idea of the “two cultures” of art and technology that came together for the Ecogame more explicit in an attempt to recover the art of the Science Museum’s first computing exhibit.

Malcolm le Grice and Stan Heyward each describe the institutional travails of making some of the first computer animation in the UK. Catherine Mason draws together the history of many of the institutions already mentioned in what is both a recap and an extension of the history she presented in “A Computer In the Art Room”. Stephen Bury and Paul Brown bring the influence of the Slade to the fore in their chapters, revealing the Slade as an important piece in the puzzle of British Computer Art.

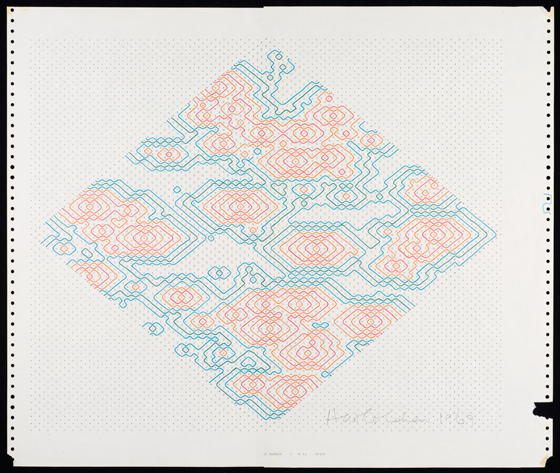

Stephen Scrivener, Stephen Bell, Ernest Edmonds and Jeremy Gardiner each describe their personal artistic journeys through the era of FORTRAN and flatbed plotting, illustrated by images of their work that again made me wish I could also see the code. Graham Howard describes how conceptual artists Art & Language didn’t use a university computer to generate the 64,000 permutations of one of their “Index” projects of the 1970s, instead gaining access to a local produce distribution company’s mainframe across several weekends.

The different strands of technology, institutions, ideas and economics are all drawn together in John Vince’s history of the PICASO graphics library, which spread from Middlesex Polytechnic to many other educational institutions and the successor to which, PRISM, was used to make the first logo for Channel 4.

Brian Reffin Smith makes clear, artists were as affected by the idea of computing as by computers themselves, especially when they didn’t have access to them. The Fun Palace was influential despite never being realized, Senster was influential despite being lost. It is important to realize just how limited access to computing machinery was in the era covered by the book, and to recognize how ideas of computing and its potential were part of the broader intellectual environment of the time.

Finally, Beryl Graham’s postscript covers the history of UK arts computing after 1980. I lived through some of the period covered and I recognise Graham’s description of it. The critical irony that she identifies in UK net.art and interactive multimedia is of key importance to its art historical value. Although I would question how uniquely British this is, the UK certainly took it as a baseline. As with Gere’s introduction, Graham presents the case for art computing in a way that the art critical mainstream should not just be able to understand but should be inspired by. Cybernetics, systems theory, environmentalism, socialisation, the content of conceptual art, and the political concerns and developments of the Cold War all illuminate and are in turn illuminated by this history.

For a book about art computing it is frustrating how little art and source code is illustrated in the book. Much work has been lost of course, and “Digital Pioneers” does illustrate art from this period. But for preservation, criticism and artistic progress (and I do mean progress) it is vital that as much code as possible is found and published under a Free Software licence (the GPL). Students of art computing can learn a lot from the history of their medium despite the rate at which the hardware and software used to create it may change, and code is an important part of that.

White Heat, Cold Logic presents hard-won knowledge to be learnt from and built on, achievements to be recognised, and art to be appreciated. Often from the people who actually made it. What was previously the secret history or parallel universe of art computing can now be seen in context alongside the other avant-garde art movements of the mid-late 20th century. I cannot over-emphasise the service that CACHe has done the art computing community and the arts more generally by providing this much needed reappraisal of early arts computing in the UK.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Featured image: Remixthebook Cover

“For us, art is not an end in itself … but it is an

opportunity for the true perception and criticism

of the times we live in.” Hugo Ball.

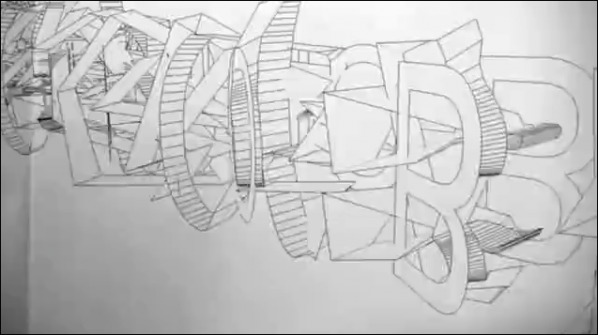

The challenge in trying to review a book like Mark Amerika’s Remixthebook, is the feeling you can only do justice to the text by doing the same with your review. The apparent simplicity coupled with the multifarious outcomes are intoxicating. You could be mistaken for believing that every possible remix would produce fresh and exciting outcomes. The key of course, is to have good source material in the first place. Also, to have developed a keen eye for what blends and meshes together and what doesn’t. Even the most disparate work requires judgment and prior awareness. Remixthebook asks us to consider the idea of remixology as part of the work of modern artists. The tone and style of the book is a blend of ideas, voices and thoughts with a myriad of concepts, which attempts be the very embodiment of the ideas it espouses.

Amerika explores various precedents for the remixological concept and draws on some known practitioners from the past: amongst them, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin. He explores existing ideas and welds them into his own armoury. Their ideas considered as part of his own creative practice, brought back to the now with new life, in our contemporary networked culture.

Other than just being a systematic breakdown of the different types of remixing and their potential outputs (or artifacts, as they might be better known in an art critical framework?) Amerika considers the pathways and theoretical underpinnings of remix culture. Having taken this beyond his own practice of the written word and web-based projects, he considers his recent and ongoing VJ work. Blending and collage-making with images during live music performances suggests some of the instinctive, instantaneous ideas that come out of a lifetime’s collecting, collating and absorbing of diverse imagery, words and cultural concepts. It’s within this process that he believes more novel outcomes can arise, against the constant flux of media creation and dissemination. It is the ‘becoming’ of the media artist that is revealed in the live remixing performance.

Reflecting on this process of cultural assimilation Mark Amerika, situates remixology within a wider creative output and theoretical framework. This involves a cross hybrid of everyday, mainstream references with high art and ‘high’ theory, all written in his at once complex and convoluted, yet easily read and enjoyable writing style. But like remixology, what looks simple is the result of deep reading and heavy conceptual thinking. This isn’t to say that you won’t have trouble decoding the writing and getting to the heart of his thinking, but it helps if you spend time with the text and allow the rhythms and structures to become second nature to you. Close reading allows the text to fall into place. For example, consider the following extract from the section eros intensification:

Here is where we enter the realm of

what I have been calling intersubjective jamming

which is different than the idea of a Networked Author

or Collaborative Groupthink Mentality that preys

on the lifestyles of the Source Material Rich

and seemingly forever Almost Famous.

It is worth remembering that Mark Amerika is a creative writer first and foremost. He uses theory as a palette from which to draw out ideas and situations for further reflection and to help give some context to the point he is trying to make. The text of remixthebook is an example of his creative practice in action, as much as it is a personal reflection on his attempts to develop a thought process for it. Theory becomes entwined in critical reflection and creative output. You don’t necessarily come to remixthebook for philosophical answers and hard academic points of view, instead you ride the maelstrom of thoughts and conceptualizing to gain a better handle on a way of considering artistic practice.

The website of the book (probably a ubiquitous extra for any media art-related publication these days) follows a natural path of inclusion and invites artists to take sections of the book and remix them according to their own aesthetic and remixological preferences. While some of the work brings in extra visuals and places itself in a flowing context of media streams, allowing different work to become part of the project, Rick Silva’s The Isarithm sources Amerika’s Sentences on Remixology 1.0 and explodes them out of the screen and into a layered and playful vortex of shapes and lines.

Will Leurs uses some captured footage taken directly off the tv screen for A Pixel and Glitch Hotel Room and combines it with some source material supplied by Amerika from several ‘lectures’ he has supplied. These lectures appear within several other contributors work as well. The point of some of these remixes and the varied forms they take (the collection includes some purely audio work) is that, as well as being interesting works themselves, they are exemplars and guides to even further potentials of the remixological principle.

Mark Amerika’s Remixthebook at times may leave you looking beyond it to the appendix or for any footnotes that would fill out spaces or help make conceptual leaps for you. That isn’t the point of the book. The idea is to take the book as a starting point and expand on your own creative process. Possibly the best approach is to literally cut-up the book and try some experimentation of your own, Brion Gysin style. Flex the covers back and pull out the pages. Through destruction and reconfiguration, the book might be bent to your will and become something that you can use. Perhaps the sight of a ripped and destroyed book would strike horror into some authors. I can’t help thinking that Mark Amerika would take great joy in the image and say that he’d planned it all along.

The remixthebook.com website

http://www.remixthebook.com

The remixthebook Blog

http://www.remixthebook.com/theblog

Remixology by OpenMedia.ca – a national, non-partisan, non-profit organization working to advance and support an open and innovative communications system in Canada.

http://openmedia.ca/remixology

Society of the Spectale (A Digital Remix)

By Mark Amerika On August 16, 2011.

http://www.remixthebook.com/society-of-the-spectale-a-digital-remix

REMIXTAPE 2.0 //

Remixology is a music blog based in Paris (France) devoted to remixes friendly music.

http://remixology.tumblr.com/

REFF- Remix the world! Reinvent reality! exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery between 25 February and 26 March 2011. http://www.furtherfield.org/exhibitions/reff-remix-world-reinvent-reality

Visitorsstudio – an online place for real-time, multi-user mixing, remixing, collaborative creation, many to many dialogue and networked performance and play.

http://www.visitorsstudio.org/x.html

Brion Gysin. Essays & Stories, Interviews, Excerpts & Publications

http://briongysin.com

“At the dawn of the new millennium, Net users are developing a much more efficient and enjoyable way of working together: cyber-communism.” Richard Barbrook.

Dmytri Kleiner, author of The Telekommunist Manifesto, is a software developer who has been working on projects “that investigate the political economy of the Internet, and the ideal of workers’ self-organization of production as a form of class struggle.” Born in the USSR, Dmytri grew up in Toronto and now lives in Berlin. He is a founder of the Telekommunisten Collective, which provides Internet and telephone services, as well as undertakes artistic projects that explore the way communication technologies have social relations embedded within them, such as deadSwap (2009) and Thimbl (2010).

“Furtherfield recently received a hard copy of The Telekommunist Manifesto in the post. After reading the manifesto, it was obvious that it was pushing the debate further regarding networked, commons-based and collaborative endeavours. It is a call to action, challenging our social behaviours and how we work with property and the means of its production. Proposing alternative routes beyond the creative commons, and top-down forms of capitalism (networked and physical), with a Copyfarleft attitude and the Telekommunist’s own collective form of Venture Communism. Many digital art collectives are trying to find ways to maintain their ethical intentions in a world where so many are easily diverted by the powers that be, perhaps this conversation will offer some glimpse of how we can proceed with some sense of shared honour, in the maelstrom we call life…”

Marc Garrett: Why did you decide to create a hard copy of the Manifesto, and have it republished and distributed through the Institute of Networked Cultures, based in Amsterdam?

Dmytri Kleiner: Geert Lovink contacted me and offered to publish it, I accepted the offer. I find it quite convenient to read longer texts as physical copies.

MG: Who is the Manifesto written for?

DK: I consider my peers to be politically minded hackers and artists, especially artists whose work is engaged with technology and network cultures. Much of the themes and ideas in the Manifesto are derived from ongoing conversations in this community, and the Manifesto is a contribution to this dialogue.

MG: Since the Internet we have witnessed the rise of various networked communities who have explored individual and shared expressions. Many are linked, in opposition to the controlling mass systems put in place by corporations such as Facebook and MySpace. It is obvious that your shared venture critiques the hegemonies influencing our behaviours through the networked construct, via neoliberal appropriation, and its ever expansive surveillance strategies. In the Manifesto you say “In order to change society we must actively expand the scope of our commons, so that our independent communities of peers can be materially sustained and can resist the encroachments of capitalism.” What kind of alternatives do you see as ‘materially sustainable’?

DK: Currently none. Precisely because we only have immaterial wealth in common, and therefore the surplus value created as a result of the new platforms and relationships will always be captured by those who own scarce resources, either because they are physically scarce, or because they have been made scarce by laws such as those protecting patents and trademarks. To become sustainable, networked communities must possess a commons that includes the assets required for the material upkeep of themselves and their networks. Thus we must expand the scope of the commons to include such assets.

MG: The Manifesto re-opens the debate around the importance of class, and says “The condition of the working class in society is largely one of powerlessness and poverty; the condition of the working class on the Internet is no different.” Could you offer some examples of who this working class is using the Internet?

DK: I have a very classic notion of working class: Anyone whose livelihood depends on their continuing to work. Class is a relationship. Workers are a class who lack the independent means of production required for their own subsistence, and thus require wage, patronage or charity to survive.

MG: For personal and social reasons, I wish for the working class not to be simply presumed as marginalised or economically disadvantaged, but also engaged in situations of empowerment individually and collectively.

DK: Sure, the working class is a broad range of people. What they hold in common is a lack of significant ownership of productive assets. As a class, they are not able to accumulate surplus value. As you can see, there is little novelty in my notion of class.

MG: Engels reminded scholars of Marx after his death that, “All history must be studied afresh”[1]. Which working class individuals or groups do you see out there escaping from such classifications, in contemporary and networked culture?

DK: Individuals can always rise above their class. Many a dotCom founder have cashed-in with a multi-million-dollar “exit,” as have propertyless individuals in other fields. Broad class mobility has only gotten less likely. If you where born poor today you are less likely than ever to avoid dying poor, or avoid leaving your own children in poverty. That is the global condition.

I do not believe that class conditions can be escaped unless class is abolished. Even though it is possible to convince people that class conditions do not apply anymore by means of equivocation, and this is a common tactic of right wing political groups to degrade class consciousness. However, class conditions are a relationship. The power of classes varies over time, under differing historical conditions.

The condition of a class is the balance of its struggle against other classes. This balance is determined by its capacity for struggle. The commons is a component of our capacity, especially when it replaces assets we would otherwise have to pay Capitalist-owners for. If we can shift production from propriety productive assets to commons-based ones, we will also shift the balance of power among the classes, and thus will not escape, but rather change, our class conditions. But this shift is proportional to the economic value of the assets, thus this shift requires expanding the commons to include assets that have economic value, in other words, scarce assets that can capture rent.

MG: The Telekommunist Manifesto, proposes ‘Venture Communism’ as a new working model for peer production, saying that it “provides a structure for independent producers to share a common stock of productive assets, allowing forms of production formerly associated exclusively with the creation of immaterial value, such as free software, to be extended to the material sphere.” Apart from the obvious language of appropriation, from ‘Venture Capitalism’ to ‘Venture Communism’. How did this idea come about?

DK: The appropriation of the term is where it started.

The idea came about from the realization that everything we were doing in the free culture, free software & free networks communities was sustainable only when it served the interests of Capital, and thus didn’t have the emancipatory potential that myself and others saw in it. Capitalist financing meant that only capital could remain free, so free software was growing, but free culture was subject to a war on sharing and reuse, and free networks gave way to centralized platforms, censorship and surveillance. When I realized that this was due to the logic of profit capture, and precondition of Capital, I realized that an alternative was needed, a means of financing compatible with the emancipatory ideals that free communication held to me, a way of building communicative

infrastructure that was born and could remain free. I called this idea Venture Communism and set out to try to understand how it might work.

MG: An effective vehicle for the revolutionary workers’ struggle. There is also the proposition of a ‘Venture Commune’, as a firm. How would this work?

DK: The venture commune would work like a venture capital fund, financing commons-based ventures. The role of the commune is to allocate scarce property just like a network distributes immaterial property. It acquires funds by issuing securitized debt, like bonds, and acquires productive assets, making them available for rent to the enterprises it owns. The workers of the enterprises are themselves owners of the commune, and the collected rent is split evenly among them, this is in addition to whatever remuneration they receive for work with the enterprises.

This is just a sketch, and I don’t claim that the Venture Communist model is finished, or that even the ideas that I have about it now are final, it is an ongoing project and to the degree that it has any future, it will certainly evolve as it encounters reality, not to mention other people’s ideas and innovations.

The central point is that such a model is needed, the implementation details that I propose are… well, proposals.

MG: So, with the combination of free software, free code, Copyleft and Copyfarleft licenses, through peer production, does the collective or co-operative have ownership, like shares in a company?

DK: The model I currently support is that a commune owns many enterprises, each independent, so the commune would own 100% of the shares in each enterprise. The workers of the enterprises would themselves own the commune, so there would be shares in the commune, and each owner would have exactly one.

MG: In the Manifesto, there is a section titled ‘THE CREATIVE ANTI-COMMONS’, where the Creative Commons is discussed as an anti-commons, peddling a “capitalist logic of privatization under a deliberately misleading name.” To many, this is a controversy touching the very nature of many networked behaviours, whether they be liberal or radical minded. I am intrigued by the use of the word ‘privatization’. Many (including myself) assume it to mean a process whereby a non-profit organization is changed into a private venture, usually by governments, adding extra revenue to their own national budget through the dismantling of commonly used public services. Would you say that the Creative Commons, is acting in the same way but as an Internet based, networked corporation?

DK: As significant parts of the Manifesto is a remix of my previous texts, this phrase originally comes from the longer article “COPYRIGHT, COPYLEFT AND THE CREATIVE ANTI-COMMONS,” written by me and Joanne Richardson under the name “Ana Nimus”:

http://subsol.c3.hu/subsol_2/contributors0/nimustext.html

What we mean here is that the creative “commons” is privatized because the copyright is retained by the author, and only (in most cases) offered to the community under non-commercial terms. The original author has special rights while commons users have limited rights, specifically limited in such a way as to eliminate any possibility for them to make a living by employing this work. Thus these are not commons works, but rather private works. Only the original author has the right to employ the work commercially.

All previous conceptions of an intellectual or cultural commons, including anti-copyright and pre-copyright culture as well as the principles of free software movement where predicated on the concept of not allowing special rights for an original author, but rather insisting on the right for all to use and reuse in common. The non-commercial licenses represent a privatization of the idea of the commons and a reintroduction of the concept of a uniquely original artist with special private rights.

Further, as I consider all expressions to be extensions of previous perceptions, the “original” ideas that rights are being claimed on in this way are not original, but rather appropriated by the rights-claimed made by creative-commons licensers. More than just privatizing the concept and composition of the modern cultural commons, by asserting a unique author, the creative commons colonizes our common culture by asserting unique authorship over a growing body of works, actually expanding the scope of private culture rather than commons culture.

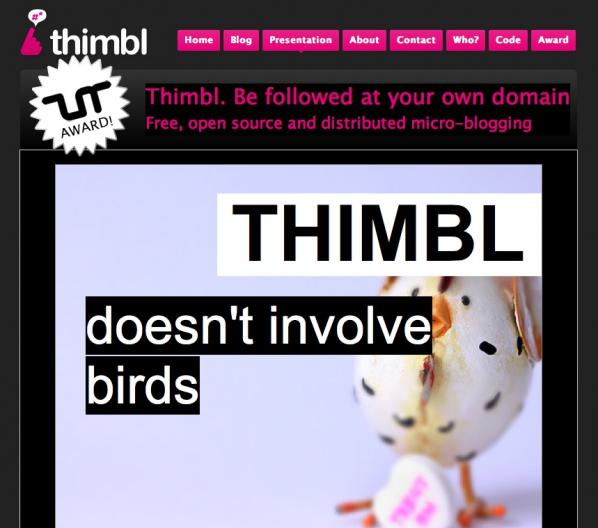

MG: So, this now brings us to Thimbl, a free, open source, distributed micro-blogging platform, which as you say is “similar to Twitter or identi.ca. However, Thimbl is a specialized web-based client for a User Information protocol called Finger. The Finger Protocol was orginally developed in the 1970s, and as such, is already supported by all existing server platforms.” Why create Thimbl? What kind of individuals and groups do you expect to use it, and how?

DK: First and foremost Thimbl is an artwork.

A central theme of Telekommunisten is that Capital will not fund free, distributed platforms, and instead funds centralized, privately owned platforms. Thimbl is in part a parody of supposedly innovative new technologies like twitter. By creating a twitter-like platform using Finger, Thimbl demonstrates that “status updates” where part of network culture back to the 1970s, and thus multimillion-dollar capital investment and massive central data centers are not required to enable such forms of communication, but rather are required to centrally control and profit from them.

MG: In a collaborative essay with Brian Wyrick, published on Mute Magazine ‘InfoEnclosure-2.0’, you both say “The mission of Web 2.0 is to destroy the P2P aspect of the Internet. To make you, your computer, and your Internet connection dependent on connecting to a centralised service that controls your ability to communicate. Web 2.0 is the ruin of free, peer-to-peer systems and the return of monolithic ‘online services’.”[2] Is Thimbl an example of the type of platform that will help to free-up things, in respect of domination by Web 2.0 corporations?

DK: Yes, Thimbl is not only a parody, it suggests a viable way forward, extending classic Internet platforms instead of engineering overly complex “full-stack” web applications. However, we also comment on why this road is not more commonly taken, because “The most significant challenge is not technical, it is political.” Our ability to sustain ourselves as developers requires us to serve our employers, who are more often than not funded by Capital and therefore are primarily interested in controlling user data and interaction, since delivering such control is a precondition of receiving capital in the first place.

If Thimbl is to become a viable platform, it will need to be adopted by a large community. Our small collective can only take the project so far. We are happy to advise any who are interested in how to join in. http://thimbl.tk is our own thimbl instance, it “knows” about most users I would imagine, since I personally follow all existing Thimbl users, as far as I know, thus you can see the state of the thimblsphere in the global timeline.

Even if the development of a platform like Thimbl is not terribly significant (with so much to accomplish so quickly), the value of a social platform is the of course derived from the size of it’s user base, thus organizations with more reach than Telekommunisten will need to adopt the platform and contribute to it for it to transcend being an artwork to being a platform.

Of course, as the website says “the idea of Thimbl is more important than Thimbl itself,” we would be equally happy if another free, open platform extending classic Internet protocols where to emerge, people have suggested employing smtp/nntp, xmmp or even http/WebDav instead of finger, and there are certain advantages and disadvantages to each approach. Our interest is the development of a free, open platform, however it works, and Thimbl is an artistic, technical and conceptual contribution to this undertaking.

MG: Another project is the Telekommunisten Facebook page, you have nearly 3000 fans on there. It highlights the complexity and contradictions many independents are faced with. It feels as though the Internet is now controlled by a series of main hubs; similar to a neighbourhood being dominated by massive superstores, whilst smaller independent shops and areas are pushed aside. With this in mind, how do you deal with these contradictions?

DK: I avoided using Facebook and similar for quite some time, sticking to email, usenet, and irc as I have since the 90s. When I co-authored InfoEnclosure 2.0, I was still not a user of these platforms. However it became more and more evident that not only where people adopting these platforms, but that they were developing a preference for receiving information on them, they would rather be contacted there than by way of email, for instance. Posting stuff of Facebook engaged them, while receiving email for many people has become a bother. The reasons for this are themselves interesting, and begin with the fact that millions where being spent by Capitalists to improve the usability of these platforms, while the classic Internet platforms were more or less left as they were in the 90s. Also, many people are using social media that never had been participants in the sorts of mailing lists, usenet groups, etc that I was accustomed to using to share information.

If I wanted to reach people and share information, I needed to do so on the technologies that others are using, which are not necessarily the ones I would prefer they use.

My criticism of Facebook and other sites is not they are not useful, it is rather that they are private, centralized, proprietary platforms. Also, simply abstaining from Facebook in the name of my own media purity is not something that I’m interested in, I don’t see capitalism as a consumer choice, I’m more interested in the condition of the masses, than my own consumer correctness. In the end it’s clear that criticizing platforms like Facebook today means using those platforms. Thus, I became a user and set up the Telekommunisten page. Unsurprisingly, it’s been quite successful for us, and reaches a lot more people than our other channels, such as our websites, mailing lists, etc. Hopefully it will also help us promote new decentralized channels as well, as they become viable.

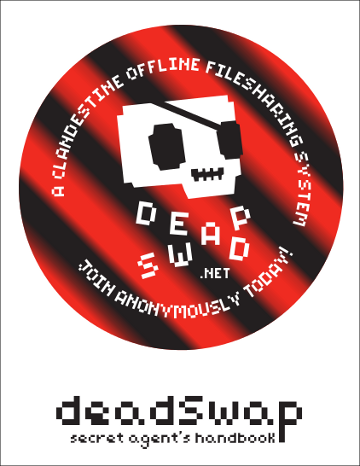

MG: So, I downloaded deadSwap (http://deadSwap.net) which I intend to explore and use. On the site it says “The Internet is dead. In order to evade the flying monkeys of capitalist control, peer communication can only abandon the Internet for the dark alleys of covert operations. Peer-to-peer is now driven offline and can only survive in clandestine cells.” Could you explain the project? And are people using it as we speak?

DK: I have no idea if people are using it, I am currently not running a network.

Like thimbl, deadSwap is an artwork. Unlike thimbl, which has the seeds of a viable platform within it, deadSwap is pure parody.

It was developed for the 2009 Sousveillance Conference, The Art of Inverse Surveillance, at Aarhus University. deadSwap is a distopian urban game where participants play secret agents sharing information on usb memory sticks by hiding them in secret locations or otherwise covertly exchanging them, communicating through an anonymizing SMS gateway. It is a parody of the “hacker elite” reaction to Internet enclosure, the promotion of the idea that new covert technologies will defeat attempts to censor the Internet, and we can simply outsmart and outmaneuver those who own and control our communications systems with clandestine technologies. This approach often rejects any class analysis out-of-hand, firmly believing in the power of us hackers to overcome state and corporate repressions. Though very simple in principal, deadSwap is actually very hard to use, as the handbook says “The success of the network depends on the competence and diligence of the participants” and “Becoming a super-spy isn’t easy.”

MG: What other services/platforms/projects does the Telekommunisten collective offer the explorative and imaginative, social hacker to join and collaborate with?

DK: We provide hosting services which are used by individuals and small organizations, especially by artists, http://trick.ca, electronic newsletter hosting (http://www.freshsent.info) and a long distance calling service (http://www.dialstation.com). We can often be found on IRC in#telnik in freenode. Thimbl will probably be a major focus for us, and anybody that wants to join the project is more than welcome, we have a community board to co-ordinate this which can be found here: http://www.thimbl.net/community.html

For those that want to follow my personal updates but don’t want don’t use any social media, most of my updates also go here: http://dmytri.info

Thank you for a fascintaing conversation Dmytri,

Thank you Marc 🙂

=============================<snip>

Top Quote: THE::CYBER.COM/MUNIST::MANIFESTO by Richard Barbrook. http://www.imaginaryfutures.net/2007/04/18/by-richard-barbrook/

The Foundation for P2P Alternatives proposes to be a meeting place for those who can broadly agree with the following propositions, which are also argued in the essay or book in progress, P2P and Human Evolution. http://blog.p2pfoundation.net

In the essay ‘Imagine there is no copyright and no cultural conglomerates too…” by Joost Smiers and Marieke van Schijndel, they say “Once a work has appeared or been played, then we should have the right to change it, in other words to respond, to remix, and not only so many years after the event that the copyright has expired. The democratic debate, including on the cutting edge of artistic forms of expression, should take place here and now and not once it has lost it relevance.”

Issue no. 4 Joost Smiers & Marieke van Schijndel, Imagine there are is no copyright and no cultural conglomorates too… Better for artists, diversity and the economy / an essay. colophon: Authors: Joost Smiers and Marieke van Schijndel, Translation from Dutch: Rosalind Buck, Design: Katja van Stiphout. Printer: ‘Print on Demand’. Publisher: Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam 2009. ISBN: 978-90-78146-09-4.

http://networkcultures.org/wpmu/theoryondemand/titles/no04-imagine-there-are-is-no-copyright-and-no-cultural-conglomorates-too/

Featured image: Games/03 Paul Sermon, Peace Games, © der Künstler 2008.

Das Spiel und Seine Grenzen: Passagen des Spiels II ed. Mathias Fuchs and Ernst Strouhal, (Springer Verlag, 2010), German language only.

Fuchs, Mathias; Strouhal, Ernst (Hrsg.)

1st Edition., 2010, 272 S. 16 Abb., Softcover

ISBN: 978-3-7091-0084-4

Versandfertig innerhalb von 3 Tagen

Mathias Fuchs is considered to be one of the first artists to explore the combination of videogames and art. Today he is a senior lecture at Salford University in England and a leading researcher on Game Art and ludic interfaces. Social and political context in videogames and how they affect our society has been a major topic in Fuch’s research. Last year he published, together with Ernst Strouhal, an anthology of videogames and its borders and how this genre is changing and influencing society. The background to the anthology was an exhibition held at Kunsthalle Wien in 2008 about art and politics in videogames.

It has been 60 years since Johan Huizinga’s now classic book Homo Ludens, the playing human, was published. Games are no longer just entertainment; it’s a major industry that is affecting our society in every aspect. In the foreword Fuchs states that the main issue for the 15 essays in the anthology is how games have changed and affected our society both politically and socially since they crossed over from the realms of entertainment into everyday experience.

Today we can find many different genres in videogames, such as serious games and persuasive games, that discuss current issues, news and social problems, artistic games which address existential and aesthetic aspects, and so on. The gaming community has grown enormously and created on-line worlds with strong virtual economics, attached real world economics. In her essay Daphne Dragona says “The virtual environments of our times therefore can be seen as social institutions with social, political and economic values resembling those of real life.”

In a similar way Tapio Mäkelä’s essay about locative games describes how the gamescene has entered the real world in the form of cos-players and social gameplays where videogames as Pacman are performed in the city streets or games as “/Noderunner/, where participants run to find open WiFi Networks, take a photo of themselves at the location and send the info via e-mail to the project’s website.” This begins to close the gap between networks and everyday experience through the practice of social gaming. The game as object is less of an obvious conclusion now that technology enables us to explore ourselves within networked, gaming contexts and mobile technologies.

The borders between game and reality have now become even more blurred and integrated, especially if we consider how technology itself also crosses over into administrational activites which have already been traditional elements of controlling, processing parts of our lives. One example is how authorities around the world are supervising these new socio-economics, such as collecting taxes from virtual incomes by using similar tools and networks. There are many questions about how games will continue to affect and change our society in the future and the anthology takes an interesting and comprehensive look into what games have to offer and what could be potential threats to our future societies.

Today games are serious business. It is not impossible that in the future a bankruptcy of an on-line gameworld could shake the real world and create an economic depression. On the other hand, could on-line game economies bring prosperity and create new jobs, an economic boom in ways we have not witnessed before? If games move into a new period of changing social experience in even more connected ways than before, then we need to understand what the consequences of these are and how to navigate through this shifting terrain. One thing is for sure, it was a long time ago that games were just entertainment.

http://www.springer.com/new+%26+forthcoming+titles+%28default%29/book/978-3-7091-0084-4

Editors Ruth Catlow, Marc Garrett, Corrado Morgana.

Digital games are important not only because of their cultural ubiquity or their sales figures but for what they can offer as a space for creative practice. Games are significant for what they embody; human computer interface, notions of agency, sociality, visualisation, cybernetics, representation, embodiment, activism, narrative and play. These and a whole host of other issues are significant not only to the game designer but also present in the work of the artist that thinks and rethinks games. Re-appropriated for activism, activation, commentary and critique within games and culture, artists have responded vigorously.

Over the last decade artists have taken the engines and culture of digital games as their tools and materials. In doing so their work has connected with hacker mentalities and a culture of critical mash-up, recalling Situationist practices of the 1950s and 60s and challenging and overturning expected practice.

This publication looks at how a selection of leading artists, designers and commentators have challenged the norms and expectations of both game and art worlds with both criticality and popular appeal. It explores themes adopted by the artist that thinks and rethinks games and includes essays, interviews and artists’ projects from Jeremy Bailey, Ruth Catlow, Heather Corcoran, Daphne Dragona, Mary Flanagan, Mathias Fuchs, Alex Galloway, Marc Garrett, Corrado Morgana, Anne-Marie Schleiner, David Surman, Tale of Tales, Bill Viola, and Emma Westecott.

In collaboration with FACT – http://www.fact.co.uk

http://www.furtherfield.org

http://www.http.uk.net/

Publisher: Liverpool University Press (31 Mar 2010)

Language English

ISBN-10: 1846312477

ISBN-13: 978-1846312472

http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/offer-listing/1846312477

A Computer in the Art Room: The Origins of British Computer Arts 1950-1980

Catherine Mason

ISBN: 1899163891

JJG Publishing 2008

Computing anywhere else but its history often seems like a carefully guarded secret. This has been alleviated by activity around the resurrected Computer Arts Society in the 2000s, notably the acquisition of CAS’s archives by the V&A and the CaCHE project at Birbeck College which ran from 2002-2005. CaCHE, run by Paul Brown, Charlie Gere, Nick Lambert and Catherine Mason, produced conferences, exhibitions, and publications including the book “A Computer In the Art Room”, by Mason.

The art room of the title is the art department of British educational institutions prior to art becoming a degree-level subject. From the 1950s to the 1970s, when the cost of computing machinery dropped from the level where only major government and corporate organizations could afford them to the level where you only needed a second mortgage to afford one, the best way for artists to get access to the enabling technology of computing machinery was usually in an educational institution.

Mason starts out by describing the artistic and art educational situation in the UK at the time of the Festival Of Britain and the foundation of the ICA in London in the early 1950s. She then explains the structure and significance of the emergence of Basic Design teaching, the impact of the Coldstream report on art education, and the rise of the polytechnic colleges over the next thirty years. This provides vital context for the emergence of art computing teaching in the UK. It is also of more general interest for British art history. Conceptualism, performance, Land Art, the Hornsey Art School occupation, and the educational and media graphics that are currently being used as the basis of “hauntological” art all share this background and can better be understood and critiqued with better knowledge of it.

Basic Design courses started in London but didn’t remain there for long. They spread and matured throughout the UK, becoming entangled with the earliest teaching of art computing in provincial technical colleges. Mason traces the family trees of art computing teaching over time through these institutions and back to London-based institutions. Some of the names are familiar from art history (Richard Hamilton, Stephen Willats), some from art computing history (Harold Cohen, John Latham). Where the people involved cross over with cybernetic art, Conceptualism or other artistic currents Mason shows how their ideas fed into and from their art computing work.

The conceptual content of art computing followed the Bauhaus, cybernetics, systems, sociological and environmental influences on art from the 1950s to the 1970s. Its technological forms likewise followed those of mainstream computing. In the 1960s time was leased on mainframes or computers were built by hand. In the 1970s, minicomputers became available and art domain-specific software frameworks or programming languages were written by their users. In the 1980s, workstations with touch tablets, framebuffers, and increasingly proprietary software brought previously unprecedented power and ease of use at the cost of more fixed forms.

The history that I had to piece together as a student from hearsay and from hints in old publications, of the PICASO graphics language at Middlesex University that I found a print-out of the manual for when I was there in the 1990s, of Art & Language’s use of mainframe computers, of early cross-overs between art computing and dance, of cybernetic systems and games that attracted mass audiences before disappearing, is detailed, illustrated and contextualized in page after page of descriptions of hardware, software, institutions, courses and projects. The detail would be overwhelming where it not for Mason’s ability to bring the human and broader cultural aspect of it all to life.

There’s Jasia Reichardt’s Cybernetic Serendipity show at the ICA, Andy Inakhowitz’s Senster robot, John Latham’s dance notation experiments, The Environment Game, and computer graphics drawn with the languages and environments developed in UK art institutions. There’s pictures of the computer systems at the Slade, the RCA, Wimbledon and other art schools that serve as insights into the artists’ studios. There’s the Computer Arts Society, IRAT, APG. And, crucially, there’s the links between them told in a narrative that is coherent while still presenting the breaks and false starts in the story.

The history of “A Computer In The Art Room” reads all too often as brief moments of individuals triumphing against the odds to produce key works of art computing then fading into obscurity, academia or commerce. But any art history that considers a specific context at such a level of detail will look like this. Mason describes works, institutions and artists that deserve broader recognition, although she is under no illusion about how far the road to that recognition may be, citing the example of how long it has taken for photography to be recognized as art in the culturally conservative UK.

The social and pedagogical changes of the period covered by “A Computer In The Art Room” reflect a time of hope and ambition for education in society that made the academy less remote. Mason provides the social, technological and educational context needed to appreciate the very real achievements of art computing that she describes against this backdrop. As a slice of art history this is richly detailed. It touches on subjects far beyond art computing that will help any art student of history better understand the period covered. And it is both a relief and an inspiration to finally have a public record of this important aspect of the history of art computing in the UK.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Co-published by Furtherfield and The Hyperliterature Exchange.

Last October I received an e-mail headed “Introducing Vook”:

The Vook Team is pleased to announce the launch of our first vooks, all published in partnership with Atria, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. These four titles… elegantly realize Vook’s mission: to blend a book with videos into one complete, instructive and entertaining story.

The e-mail also included a link to an article about Vooks in the New York Times:

Some publishers say this kind of multimedia hybrid is necessary to lure modern readers who crave something different. But reading experts question whether fiddling with the parameters of books ultimately degrades the act of reading…

Note the rather loaded use of the words “lure”, “crave”, “fiddling” and “degrades”. The phraseology seems to suggest that modern readers are decadent and listless thrill-seekers who can scarcely summon the energy to glance at a line of text, let alone plough their way through an entire book. If an artistic medium doesn’t offer them some form of instant gratification – glamour, violence, excitement, pounding beats, lurid colours, instant melodrama – then it simply won’t get their attention. But publishers have a moral duty not to pander to their readers’ base appetites: the New York Times article ends by quoting a sceptical “traditional” author called Walter Mosley –

“Reading is one of the few experiences we have outside of relationships in which our cognitive abilities grow,” Mr. Mosley said. “And our cognitive abilities actually go backwards when we’re watching television or doing stuff on computers.”

In other words, reading from the printed page is better for your mental health than watching moving pictures on a screen: an argument which has been resurfacing in one form or another at least since television-watching started to dominate everyday life in the USA and Europe back in the 1950s. To some extent this is the self-defence of a book-loving and academically-inclined intelligensia against the indifference or hostility of popular culture – but in the context of a discussion of Vooks, it can also be interpreted as a cry of irritation from a publishing industry which is increasingly finding the ground being scooped from under its feet by younger, sexier, more attention-grabbing forms of entertainment.

The fact that the Vook publicity-email links to an article which is generally rather sniffy and unfavourable about the idea of combining video with print no doubt reflects a belief that all publicity is good publicity – but it is also indicative of the publishing industry’s mixed attitudes towards the digital revolution. On the whole, up until recently, they have tended to simply wish it would just go away; but they have also wished, sporadically, that they could grab themselves a piece of the action. But those publishers who have attempted to ride the digital surf rather than defy the tide have generally put their efforts and resources into re-packaging literature instead of re-thinking it: and the evidence of this is that the recent history of the publishing industry is littered with ebooks and e-readers, whereas attempts to exploit the digital environment by combining text with other media in new ways have generally been ignored by the publishing mainstream, and have therefore remained confined to the academic and experimental fringes.

The publishing industry’s determination to make the digital revolution go away by ignoring it has been even more evident in the UK than in the US. The 1997 edition of The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, for example, contains no references to ebooks or digital publishing whatsoever, although it does contain items about word-processing and dot-matrix printers. On the other hand, Wired magazine was already publishing an in-depth article about ebooks in 1998 (“Ex Libris” by Steve Silberman, http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/6.07/es_ebooks.html) which describes the genesis of the SoftBook, the RocketBook and the EveryBook, as well as alluding to their predecessor, the Sony BookMan (launched in 1991). Even in the USA, however, enthusiasm for ebooks took a tremendous knock from the dot-com crash of 2000. Stephen Cole, writing about ebooks in the 2010 edition of The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, summarises their history as follows:

Ebook devices first appeared as reading gadgets in science fiction novels and television series… But it was not until the late 1990s that dedicated ebook devices were marketed commercially in the USA… A stock market correction in 2000, combined with the generally poor adoption of downloadable books, sapped all available investment capital away from internet technology companies, leaving a wasteland of broken dreams in its wake. Over the next two years, over a billion dollars was written off the value of ebook companies, large and small.

After 2000, there was a widely-held view (which I shared) that the ebook experiment had been tried and failed: paper books were a superb piece of technology, and perhaps a digital replacement for them was simply never going to happen. There were numerous problems with ebooks: too many different and incompatible formats, too difficult to bookmark, screens hard to read in direct sunlight, couldn’t be taken into the bath, etc. But ebooks have always had a couple of big points in their favour – you can store hundreds on a computer, whereas the same books in paper form demand both physical space and shelving, you can find them quickly once you’ve got them, and they’re cheap to produce and deliver. Despite the dot-com crash and general indifference of the reading public, publishers continued to bring out electronic editions of books, and a small but growing number of people continued to download them.

Things really started to change with the launch of Amazon’s Kindle First Generation in 2007. It sold out in five and a half hours. With the Kindle, the e-reader went wireless. Instead of having to buy books on CDs or cartridges and slot them into hand-helds, or download them onto computers and then transfer them, readers using the Kindle could go right online using a dedicated network called the Whispernet, and get themselves content from the Kindle store.

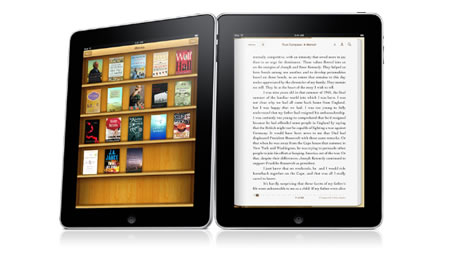

Despite this big step forward, the Kindle was still an old-school e-reader in some respects: it had a black and white display, and very limited multimedia capabilities. The Apple iPad changed the rules again when it was launched in April 2010. The iPad isn’t just an e-reader – it’s “a tablet computer… particularly marketed for consumption of media such as books and periodicals, movies, music, and games, and for general web and e-mail access” (Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I-pad). Its display screen is in colour, and it can play MP3s and videos or browse the Web as well as displaying text. For another thing, it goes a long way towards scrapping the rule that each e-reader can only display books in its own proprietary format. The iPad has its own bookstore – iBooks – but it also runs a Kindle app, meaning that iPad owners can buy and display Kindle content if they wish.

It seems we may finally be reaching the point where ebooks are going to pose a genuine challenge to print-and-paper. Amazon have just announced that Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has become the first ebook to sell more than a million copies; and also that they are now selling more copies of ebooks than books in hardcover.