FILE Sao Paulo, Electronic Language International Festival, which took place in Brazil this August is subtitled Two Thousand and Eight Million Pixels. A heading that references the vast resolutions made possible by the 4K digital projection systems that were used to show cinematic work at the festival this year, and forming one of the main themes of the show. Other categories set up in an impressively produced catalogue that accompanied the show included; installations, game art, media art and performance. Works under these categories were exhibited alongside games, and the projects of commercial exhibitors to produce an energetic, rag-tag collection; that was constantly bursting out of the curatorial confines that these groupings defined.

In it’s ninth year, and continuing to expand into other cities around Brazil, FILE offers a particularly south American perspective on the global phenomena that is media art, bringing together artists from Brazil and Argentina, as well as from Japan, North America and Europe. The opportunities for debate and discussion with people of similar interests as well as the camaraderie of working together to put on a show are what made the event particularly memorable for me on a personal level, and also (I hope) helped develop my understanding of Brazilian culture.

In a country that has both 120 and 220 volt electrical circuits, and a working culture (at least in the gallery where we were exhibiting) that has a surfeit of people; each with clearly defined job roles, the ability to work collaboratively is a necessity. Working together with large groups of electricians, carpenters, AV technicians, carpet fitters, painters and decorators, and cleaners; as well as directors, architects, curators, administrators, overseers, and volunteers meant that someone, somewhere in the building would be able to help with your particular problem. While the ability to take on board the opinion of each-and-every person involved, about the merits of, for instance, a particular technique for the securing of a projector, before reaching an agreed solution, is the job of a seasoned negotiator.

The installation process of my own work Aquaplayne, required the complete construction of an installation from scratch, caused by the rather Byzantine customs situation that exists in Brazil. Shipping work extant would have meant it sitting in customs for months, multiple form filling and huge cost to the festival. As this was not then an option, I would have to recreate my work by ordering materials for purchase in Brazil as much as possible, while surreptitiously bringing the more difficult to locally source tech through customs myself. As I later discovered I was not the only artist who had to ‘smuggle’ equipment through customs.

Giles Askham, installation, electronic language. 2008.

Just as my plane was about to land, I was presented with a customs declaration form that asked if I was bringing anything into the country that cost more than $500 US. My laptop is battered to bits, and while it did originally cost more than this, I did not particularly wish to pay the Brazilian government an additional fee for the privilege, and so ticked a different box. With sweaty palms and shifty eyes, I managed to clear airport customs without any further questions. I was later amazed to hear from other artists, that they had had similar experiences, only with highly sophisticated hardware worth many times the cost of my laptop; this did at least help to put my own unease into proper perspective, but I can only imagine how they felt in the arrivals hall.

The installation process took a long time, other artists whose work was supposed to be plug-and-play took three days to get up and running, mine took a week. It often seemed, as Sheldon Brown once commented, that in the southern hemisphere, us northerners would have to ‘spin our electrons in the opposite direction’. This process was not without its advantages however, it did mean there was time to iron out physical and coding glitches and really concentrate on the presentation of the work. It also enabled me to get to know the other people working on the show, many of whom were very generous with their time in assisting in the installation of my work.

As is often the case with these types of shows, there came a moment on the day before the launch when everything seemed to fall into place. Where before there had been bare wires, trailing cables and piles of detritus, now there stood sparkling white, newly painted plinths, and gleaming bright, perfectly calibrated, projections. At the end of the day an army of red-shirted invigilators descended on the show and learnt the ropes by playing with the works.

The launch event itself was packed. While the show was open to the public, numbers were strictly limited, but this was not the case on the opening night. I have never seen so many people in a gallery and actually found it quite intimidating. What it did provide though was a good technical workout for all the exhibited pieces, all of which successfully passed this examination without a hitch.

There were many works of note exhibited, some of my own particular favourites included; Memories by Anaisa Franco, Full Body Games by Jonah Warren and Steven Sanborn, LevelHead by Julian Oliver, The Scalable City by Sheldon Brown and L.A.S.E.R Tag by Graffiti Research Lab.

Anaisa Franco, a Brazilian artist who recently graduated from IDAT Plymouth, exhibited Memories, a sculptural work consisting of two humanoid robotic heads, hung from the ceiling at head height, facing one another. Cast in clear plastic, so that we can see their inner digital workings, and with tiny LCD monitors mounted into the back of their skulls, in order that we might view the animated dreams that they exchanged with each other.

Anaisa Franco, sculptural work, humanoid robotic head, digital.

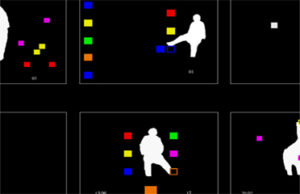

Full Body Games by Jonah Warren and Steven Sanborn requires that we jump in and physically control the game. Through shadow-mapping our image is transposed into a projection, from where we either jump over or duck under simple graphical objects that move across the screen. Selecting one of the three other options enables us to use our silhouette to touch game objects, making full use of our bodily gestures and motions in the works game-play.

Full Body Games by Jonah Warren and Steven Sanborn.

LevelHead by Julian Oliver offers an intriguing interface, consisting of a simple set of cubes placed on a plinth in front of a projection. The resulting effect of our engagement with these cubes is remarkable. Upon walking into the room, we are presented with our own mirror image and that of the plinth projected onto the far wall. Where we might however expect to see images of the cubes, we glimpse a digital world. Taking the place of the cubes in the projection is a set of three dimensional rooms, doors and stairways, populated by a single, shadowy figure. The object of the exercise quickly becomes apparent. By picking up the cubes and gently tilting them backwards, forwards and side-to-side we are able to direct our figure through the maze that is its little world, between rooms and from one cube to another in order to find the exit. A simple idea executed with sophistication, pattern recognition software is used to detect the position of the cubes within three-dimensional space, it then relays this information back to the program which then directs the character in its Kafkaesque wonderings.

LevelHead by Julian Oliver.

The Scalable City by Sheldon Brown equally pushes our perceptions of what technology is capable of, while also making use of a cube in its interface, by creating with the aid of satellite mapping, distopian versions of six different cities around the world, each situated on one face of the cube. A trackball enables our navigation between the cities, but our use of this also creates the infrastructure of each plane. Our movement through the space lays down roads as we cut through the virgin landscape, in a tornado of suburban housing, quickly creating each city in a photorealist sprawl of nondescript neighbourhoods. Using state-of-the-art hardware and software systems, we are reminded of what we are capable of doing to our planet using this technology, as we gleefully create our very own Borg cube.

The Scalable City by Sheldon Brown.

Sheldon Brown is also very involved with the 4K cinema project that FILE is highlighting this year, and presents a narrative version of The Scalable City, one of 14 newly commissioned films, that makes use of the technology at the festival. With an extended essay by Lev Manovich in the exhibition catalogue on the subject, in which he likens the onset of the technology that has 8 million pixels of resolution, to that of Seventeenth Century Dutch painting, in terms of its clarity of representation. The experience of watching the films from the audience is certainly eye-popping. Starting the sequence of films with an homage to the Lumiere brothers, we are confronted with what appears at first to be a high-resolution stills photograph of a desert landscape. Everything is still, there is not a cloud in the sky, and then in the distance we see smoke, is this digitally generated? No, the work is actually a live action video, and it is the steam from a train, one which is bearing down on us, in crystal clarity, all of the highlight and shadow detail in the image perfectly resolved in each and every frame, then the train passes and the screen returns to its stillness and calm. What follows are a series of films, ranging from computer animations of milky-way fly-throughs, mathematical modelling routines, and ray-traces of molecular growth, to narrative and national geographic style work, all of which perfectly reveals the technical brilliance of the imaging system being used. An additional, unintentional effect of this hyper-real presentation is that it makes us ultra-sensitive to the occasional frame that gets dropped from the film sequence. As well as the single pixel line that dissects the centre of the screen in this particular setting. The clarity of detail provided by such systems of representation, conversely makes us even more aware that what they offer us are still mere shadows on the wall.

L.A.S.E.R Tag by Graffiti Research Lab an ‘open-source weapon of mass defacement’. in contrast, uses a 5000K projector, (in old money, the K here refers to the number of lumens of power the projector uses, rather than the number of lines of pixels projected, which in this case is likely to be a more traditional 1024 or so). The purpose being to open up the cities buildings to the work of it’s graffiti artists. By using a green laser pen to draw and write onto the sides of offices, the pilings of bridges, and the plinths of Sao Paulo’s monuments. The L.A.S.E.R Tag re-projects these lines in a single red, green, or blue channel, with the addition of the line weight and drip patterns that would accompany them if they were applied with a spray-can; and in so doing opening up inaccessible private space to public comment.

L.A.S.E.R Tag by Graffiti Research Lab.

The works exhibited at FILE could be categorised in terms of their models of production. Much of the work exhibited was created within the emerging European lab system, concentrating on collaboration and the use of open source software, with work from Spain in particular being well represented. In contrast to this is the highly funded US university system, which in terms of the works exhibited here was making full use of cutting-edge hardware systems in their productions. While the 4K cinema screenings takes pride of place in the catalogue, it can be described as leading edge technology, and will certainly receive widespread coverage over the coming years, other interesting patterns of production emerge. There were also contributions from commercial Brazilian producers of interactive experiences, work created using open source software. The programming languages these companies used were not chosen for political or critical reasons, but simply in order to keep down the cost of production. Perhaps FILE provides with its mixture of forms and tropes, unlikely combinations of artistic and commercial projects – a more valid appraisal of a global scene than we might first imagine.

FILE SAO PAULO 2008

http://www.file.org.br/

Memories- Anaisa Franco

http://anaisafranco.blogspot.com/2007/12/building-connected-memories-heads.html

Full Body Games – Jonah Warren and Steven Sanborn

http://www.feedtank.com/fbg.html

Levelhead – Julian Oliver

http://julianoliver.com/levelhead

The Scalable City – Sheldon Brown

http://crca.ucsd.edu/sheldon/scalable/

L.A.S.E.R Tag – Graffiti Research Lab

http://graffitiresearchlab.com/?page_id=76