Among twenty snowy mountains,

The only moving thing

Was the eye of the blackbird.

Edward Picot, originally from Hertfordshire in the UK, now lives in Kent with his wife and daughter. He completed his Ph.D in English Literature in 1997 and then published his thesis in book-form ‘Outcasts from Eden: Ideas of Landscape in British Poetry since 1945’. It deals with modern landscape poetry in the context of the environmental crisis, and includes substantial essays on five postwar British poets Philip Larkin, R S Thomas, Charles Tomlinson, Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney. It also examines the recurring myths of Eden and the Fall, which have been used to assert and explain the superiority of the countryside or natural world (seen as Eden) to the urban environment (seen as the result of the Fall).

His day job is with the health service but he makes time in his schedule for self-publishing online, where you will find various types of work. He publishes something new every month; usually a piece of criticism for one month, then followed by a visual work the next. In 2003 he set up another web site called The Hyperliterature Exchange[1], a review and directory of Hyperliterature works for sale on the Web, with links to the places where it can be bought. Featuring works by artists and poets such as Mac Dunlop, Peter McCarey, Martha Deed and many others this is well worth investigation.

Edward Picot’s visually playful, web art interpretation of Wallace Stevens’s poem Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird[2] is a curious artwork for many reasons. Once you have visited the work it lingers in the mind and on each return it maintains a strong freshness. So what is it in this work that compels me to re-experience its particularly strange and magical reasoning?

Most of Picot’s web artwork communicates to a younger generation as well as for adults. For instance the Flash piece created in 2006 called Frog-o-Mighty[3], was a collaboration between himself and his daughter Rachel. In this piece they used as the main props for the story ornaments from their living-room window-sill, and also the window-sill as the setting, the scenery. On his web site Edward says “Many of my recent creative pieces have been either entirely or partially inspired by the games I play with my daughter Rachel. They therefore feature a lot of jokes and toys.” Frog-o-Mighty first appeared online in Autumn 2006 as part of the Art of the Animal Net Art Exhibition, curated and designed by poet and net artist Jason Nelson.

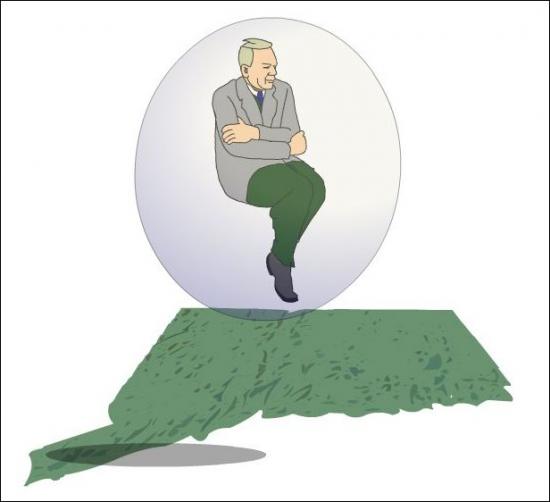

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird is an altogether more complex affair, even though it is as equally as approachable as Frog-o-Mighty when first experienced. The poem was originally written by the American poet Wallace Stevens[4], who was born in Reading, Pennsylvania on October 2, 1879, and died at the age of seventy-six in Hartford, Connecticut on August 2, 1955. Stevens main focus and interest was to write on ideas that “revolved around the interplay between imagination and reality and the relation between consciousness and the world.”

Unlike Frog-o-Mighty, Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird has a little more interaction, but not much. The only two sections where you can interact (as in clicking) are either at the beginning where you can find some interesting information about the work or at the first page, the main interface for the actual piece itself. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not desperately asking for interaction here. In fact, there are many out there who dispute interaction and the process of just habitually clicking away. Interaction itself, can become more of a means to an end. Sometimes it is nice to just let a work appear and happen in front of you.

Picot says “the idea for this version of Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird came to me a couple of years ago, when I was working on my own one Saturday and there was a heavy fall of snow. In the middle of the afternoon, whilst waiting for the kettle to boil for my umpteenth cup of coffee, I happened to glance out of the window. In the carpark outside grows a crab-apple tree, which bears very bright red fruit in winter, and because of the snow the apples were looking particularly vivid. On one branch of the tree perched a blackbird – a startling contrast with both the white snow and the red fruit. Pretentious soul that I am, I was immediately reminded of Wallace Stevens’ poem, and almost as immediately it occurred to me that the crab-apple tree would make an excellent interface for a new media version, with the bright red apples acting as buttons to call up the different sections.”[5]

On first entering, you immediately come across a silhouette of a crab-apple tree. There are few plants that create greater intrigue or visual impact during all four seasons than the flowering of a crab-apple tree. Colours can range from dark-reddish purples through the reds and oranges to golden yellow and even some green. On this occasion they are deep red and the tree itself bares no leaves so we must assume that it is winter. Crab-apples are usually no larger than 2 inches in diameter, a perfect fruity, nature-nurtured confectionary for a blackbird to peck into. The Celtic year has 13 months and each month is associated with a particular tree and its contribution to mankind, together with its forms of healing and associating for the month they represent. “The crab-apple is the ancient mother of all orchard trees and Britain’s only indigenous apple tree. The flowers are valuable to insects and the fruit is important to birds.”[6]

Before we even touch upon the role of the blackbird or delve into specific areas of the work’s inner content, there are some interesting elements of symbolism at play. Whether this is deliberate or not, it is of course the artists’ prerogative to leave different measures of ambiguity hanging loose according to their process and decision making, which of course can add an extra nuance to the whole mix. In the Garden of Eden story in the Biblical book of Genesis God charges both Adam and Eve to tend the garden in which they live, commanding Adam not to eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil – we know the rest. Picot’s decision to use the archetypal image of a tree as the interface, offers some interesting parallels that may be not as binary, absolute or as literal as the Biblical book of Genesis. Yet it introduces us to elements that symbolically touch upon religion and metaphysics, which weave in and out through the whole piece.

Much of the religious flavour does echo from Wallace Stevens himself, although not with obvious traditional or orthodox values. He believed that God was a human creation. Yet he was interested in something as equivalent which ruled the universe, our hearts and minds. Through his poetic reasoning he found that complete contact with reality was a closer conduit towards discovering the truth of what we really are. Proposing that, ‘with the right idea, we may again find the same sort of solace that we once found in divinity.’ He felt that humanity could find truth and our own heaven(s) through sensuous apprehension of the world. “This supreme fiction will be something equally central to our being, but contemporary to our lives, in a way that god can never again be.” [7] Whether he felt that god was ever a reality is not clear, yet it is interesting that he believed that humanity could replace whatever void with something equally significant and relevant. He also thought that reality was and is a product of our imagination, this shapes the world.

The various contexts created throughout the “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” might be considered from the romantic point of view as haphazard attempts at defining or identifying the writing subject’s relation to an object that is already ambiguous in itself and is a symbol rich in potential for producing hopes and fears. On ‘Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird’. Helen Vendler.

This mixture of existential realism, metaphysical and spiritual reflection through the process and practice of poetic discourse settles neatly with Picot’s own contemporary version of, Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird. As you explore the various audio/visual presentations within each section, which feature stanzas from the poem. Each of the Stanzas introduces or guides you into a specific theme or micro-journey that unfolds before your eyes. The first one begins quite simply, with the visitor being taken to a cartoon image of a mountainous vista then the blackbird, then a zooming into its eye. From then on as you move through the different sections you are taken into different worlds and situations.

It consciously acknowledges the original spirit of the text, whilst introducing a response that at the same time attempts to deal with what these words may mean today. This interpretation of the poem not only gives us the opportunity to appreciate how special the original work is by following the text, whether in order, or haphazardly, but it also creates a moment in time that opens up a rare experience of two creative minds as a kind of collaboration.

There are various other clues within the whole work which can enlighten you of the different influences to Picot’s work. If you click on the eighth crab-apple you are taken to a bookshelf. One of the books on the shelf is called ‘Seeing Things’ which is Oliver Postgate’s autobiography. In the UK, Oliver Postgate [8] was responsible right from the late 1950’s to this day for, the most imaginative and magical children’s television. “He is the creator and writer of some of the most popular children’s television programmes ever seen in Britain. Pingwings, Pogles’ Wood, Noggin the Nog, Ivor the Engine, The Clangers and Bagpuss, were all made by Smallfilms, the company he set up with Peter Firmin, and were shown on the BBC between the 1950s and the 1980s, and on ITV from 1959 to the present day. In a 1999 poll, Bagpuss was voted most popular children’s programme of all time.” My personal favourites are Noggin the Nog, Bagpuss and The Clangers.

Moving away from the mystical and magical elements that reside in the piece, there are a few darker moments to experience. One of them is the portrayal of the real-life disaster such as the Hurricane Katrina disaster on Louisiana and connected regions. Images of newspaper reportage, snippets of the carnage and the hurricane are shown, as well as the blackbird flying across the scenery.

The blackbird whirled in the autumn winds.

It was a small part of the pantomime.

The role of the blackbird seems to me a kind of spectre, a shadow of ours, Stevens’s and Picot’s consciousness. It takes us through the scenes, introducing with each stanza various points of reference, like a guide. It sees what we see, but opens our eyes to re-imagine or remember certain things, letting us come to terms with our own conclusions alongside the poetry, an important trigger and voice of the work.

I am hesitant in continuing with unearthing more of this work. What I will conclude with is that, what I find personally interesting in Picot’s version of Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird. Is that, it is connected to so many different things that exist outside of the work itself. There are jokes, puns, and some darker moments but all presented in a playful light. The world is a backdrop yet at the same time it still manages to maintain a fresh and simple narrative that can be understood at many levels. It revels in its small bites of aspects of human nature; simple yet profound. On the whole, it is a delightful and beautiful experience that can move you and have you thinking about metaphysical matters as well as real situations. It breaths life into our grey and seriously battered worlds, shining a kind of light which asks us to slow down a little and let go of our socially engineered sensibilities and open ourselves up to a snippet of richness that is not trying to impress how clever it is but how imagination can also be about play.

The Hyperliterature Exchange[1]

http://hyperex.co.uk/

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird – Wallace Stevens [2]

http://www.english.uiuc.edu/maps/poets/s_z/stevens/blackbird.htm

Frog-o-Mighty – 2006, Edward Pictot. [3]

http://www.edwardpicot.com/frog-o-mighty/

Wallace Stevens: Biography and Recollections by Acquaintances:[4]

http://www.english.uiuc.edu/maps/poets/s_z/stevens/bio.htm

Thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird – notes [5]

http://edwardpicot.com/thirteenways/notes.html

Celtic Tree Alphabet (Ogham Calendar). [6]

https://orders.mkn.co.uk/tree/birthdaytree/$USD

Southworth, James G. Some Modern American Poets, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1950, p. 92.[7]

http://teenink.com/Past/2001/April/Books/13Ways.html

Oliver Postgate [8]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_Postgate