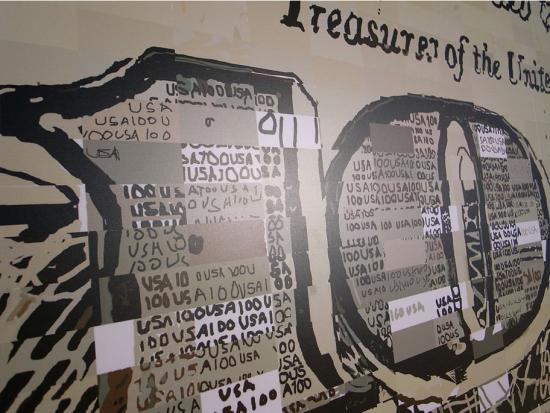

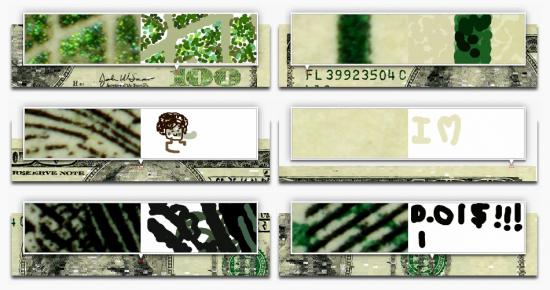

Arriving at the homepage of Ten Thousand Cents, an Internet artwork by Aaron Koblin and Takashi Kawashima, a mottled image of a one hundred dollar bill slowly fades into view. Ben Franklin looks out sedately. Mousing over the large image, the cursor is replaced with a small red rectangle. And here lays the beauty of the project; with the click of each rectangle, a zoomed in portion of the one hundred dollar bill is revealed. On the left side is a high-resolution photograph of that tiny portion of the bill. On the right side, a real-time moving image plays, revealing how the image was drawn by a human hand in a drawing program created by Koblin and Kawashima. There are, in fact, 10,000 such rectangles and each was created by a Turker through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk marketplace.

Over the course of five months (from November 2007 to March 2008) Koblin and Kawashima posted tasks, known as HITs, Human Intelligence Tasks, on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk site. Having broken down an image of a one hundred dollar bill into 10,000 sections, Turkers were tasked with redrawing their assigned section. Each Turker was paid $.01 for the task, making the total payment of drawing a one hundred dollar bill one hundred dollars. (Prints of the project can also be bought for one hundred dollars. All proceeds are donated to the One Laptop per Child (OLPC) project) Each Turker worked anonymously, unaware that what they were drawing was a section of a bill or that their work would eventually be combined with other Turkers’ work to create an art project. The variability is endless. Some Turkers methodically draw in the lines and painstakingly shade in boxes. Some quickly slash the paint tool across the page; one imagines they felt they had better things to do with their time. Some are cheeky, using the space for digital graffiti or messages like “I love U.” Most copy the image exactly. Yet, with the differing movements and tempos, every one suggests a different story and different person behind the tool. I suggest you take a few minutes and watch the unfolding scenes. They are oddly, satisfyingly banal and beautiful.

The project and its presentation on the website are undoubtedly elegant. Yet, the conceptual work behind the piece is a bit murkier. The project description states, “The project explores the circumstances we live in, a new and uncharted combination of digital labor markets, ‘crowdsourcing,’ ‘virtual economies,’ and digital reproduction.” Big and important themes. What are the implications of crowd-sourcing for creative work? For any kind of paid work? Where is the distinction between work and play? Creativity and re-presentation? In this deeply networked age, what are the evolving relations between individual and collective action?

The Mechanical Turk, made by Wolfgang de Kempelen in 1769, caused a sensation in 18th and 19th century Europe, first for its existence as a seemingly intelligent chess playing automaton – one who could beat Ben Franklin and even Napoleon in chess – and subsequently, for being an infamous hoax. Inside of the automaton was in fact a man, a skilled chess player. The Mechanical Turk was no thinking machine. It was an elaborate performance of concealment and human skill.

In 2005, in an ironic (and some might say distasteful) turn of events, Jeff Bezos of Amazon named a new business venture, Amazon Mechanical Turk. The idea was to make a digital marketplace that capitalized on the unique intelligence of human agents. Broken down into microtasks, known as HITs, Mechanical Turk provides a means to accomplish those tasks that humans can do quickly but which would take computers much longer to do, for instance, tagging images, taking surveys or transcribing audio recordings. This Mechanical Turk is also a performance of human skill, one that revels in its basis in human intelligence – Bezos calls it “artificial artificial intelligence” – but one that also operates within a mode of concealment and indeed, alienation.

As Katharine Mieszkowski of Salon wrote about Mechanical Turk in 2006, “There is something a little disturbing about a billionaire like Bezos dreaming up new ways to get ordinary folk to do work for him for pennies.” Critics of Mechanical Turk abound, and their objections point to the insidious labor relations that Mechanical Turk enforces, implying that Mechanical Turk approaches a virtual sweatshop. The system was designed for employers, not employees. The earnings of Turkers fall within a gray area of digital labor, officially being classified as contractor work, subject to high self-employment taxes and no option for benefits. Although a rating system protects employers, in so far as employers can choose to reject a work offer from a Turker or refuse to pay a Turker if the work is completed unsatisfactorily, no such system protects Turkers. As advocates of a Turker Bill of Rights have pointed out, there is no effective outlet within Mechanical Turk for Turkers to voice grievances against employers. What does exist is a vibrant community forum, Turker Nation, where Turkers advise each other on known scammers.

Moreover, although anecdotally Mechanical Turk is understood as more game or past-time than employment, a recent study out of University of California, Irvine’s Informatics Department points out that almost a third of Turkers rely on Mechanical Turk as a source of income. Another study found that nearly half of Turkers report their motivation for working as income related. For this population of Turkers, it is troubling to consider the possibilities of exploitation and unfair labor practices.

In this light, I find the artists’ neat appropriation of the mechanisms of Mechanical Turk unsettling. The implications and the stakes of Mechanical Turk as an economic system are left untouched. And considering that the artists chose to create a representation of money and employ Turkers, these dimensions of economy and labor are present but disappointingly unaddressed.

Yet, the moments in the project that remain in my mind’s eye like lovely specters as I glance at the dollar bill that I traded for coffee this morning, are the movements of the individuals who drew each section. On this level, the project is like a fantastic cabinet in which each drawer opens onto a new wonder. Perhaps what Ten Thousand Cents effectively offers is not a statement about labor politics or late capitalism’s continuing ability to provide structures for domination and exploitation. Perhaps Ten Thousand Cents asks us to take a different step toward understanding “the circumstances we live in,” revealing the endless variability of individual expression. In this networked age, we often act collectively, that is, together, parallel, most often without knowledge of the larger directions toward which our actions will lead. Collaboration, laboring together, is notion whose meaning is expanding and changing in the 21st century. What remains, even among protocols and code, is individuality. Though we are subsumed by larger structures, we do have spaces for self-expression and self-formulation. Leave an exploration of the limits of these spaces to others – and I surely believe we must consider the limitations. Yet we must also explore and value the spaces of possibility and the domains where we are active agents. We are called to remember that every artifact is irreducible to its mere instance in the world – it is a sum of processes and individual actions.

Of course, “the circumstances we live in” also requires us to keep in mind the bottom line. It’s all about the Benjamins, as the phrase goes. In response to a HIT, no less, requesting an answer to the question, “Why do you complete tasks in Mechanical Turk” one Turker wrote, “I do it for the money!”