No archive is perfect. No one, I assume, will contest this claim – especially, in this day and age, where archives are everywhere and everything is miscellaneous (Wiser). It is a reasonable claim that this new way of using archives, socially and privately, has created a new understanding of what archives are – and what they are not. At least, it seems much more logical today to claim that any archive including the ‘grand’ and professional (scientific) archives of national and international libraries and museum are imperfect and even selective. People are selective in their choices and tastes and their archives are a mirror of their biases and behaviours. Personal taxonomies are contextualizing social networks. As a mirror of professional and scientific networks, it is easy to assume similar processes of (in this case academically grounded) choices and tastes taking place in the formation and construction of ‘grand’ archives.

My claim is that there are huge lacunas in the construction of the ‘grand’ archives, as well as in the construction of our ‘collective’ knowledge, and it would be tempting – if we consider the other end of the argument that Mark Wiser makes, which indicates that we may never bridge or fill all of them (the idea would be absurd) – to claim that none of it matters. The ‘homemade’ logic being that there is not anything interesting to find, anyway – and if there were, ‘they’ (the professional and scientific networks) would certainly know about it.

This paper argues that this is certainly not the case. The professional and scientific networks did not find, and do not know everything (!) – a lot of dynamic and significant cultural knowledge remain unheard of. Therefore, it is important and should be a priority to examine the lacunas and gaps (if we can find them) and understand them in a cultural and scientific context. Somehow they were excluded or sifted out of the ‘official’ construction of archived knowledge, and how and why this happened is an important scientific question to ask. Furthermore, the notion (it does not qualify as an argument) that only the important stuff made it into the archives, and that it only made it exactly because it was important, is as absurd as it is, almost, a dangerous (and not scientific) point of view.

In any case, the unheard avant-gardes are a part of the lacunas and gaps of the ‘grand’ archives. However, they are the very stuff of private and social networks and ‘small’ archives – to be considered as precursors (avant-garde) of the social media revolution. Maybe it is not until now that we are able to imagine the formats of an archive for ephemeral and mediated art practices – as well as other innovative and technologically experimental modalities of cultural production.

What is an unheard avant-garde? Of course, the answer may be tautological: no one has ever heard of the unheard avant-garde, as it were.

And then again – rumours and curatorial intuition has it that private and ‘small’ archives around the globe are full of unheard stuff. In this case, I am focusing on the ephemeral, experimental, performative and intermedial art practices and projects by energetic project makers (often long since deceased) that never made it into the ‘grand’ archives – and, after a time, are forgotten, simply.

This project has the anterior purpose to define the modalities needed and methodologies to obtain them in order to reactivate, on a curatorial and humanistic level, the field of the ‘unheard avant-gardes’ (if it indeed is one field) – what are the categories? How do we describe them? Do they manifest themselves into (new) paradigms? And what would be best practice for metadating and documenting the field? Furthermore, these questions also point towards a more fundamental problematic regarding the definition and function of ‘art’ in a mediated cultural context and environment.

What is invested or, indeed, put at risk by reactivating the unheard? This is a question pointing back to the discussion of the transforming ontology of humanstic reception and its modality of ’archiving’ (a discussion I partake in another paper (Flexowriter…).

Some remarks on my use of the Avant-garde concept.

A Classical approach would be to explore the history (of known representations) & theories of the avant-garde, describe and discuss in inter(con)textual views. Fine as this may be, however, there is a tendency to overlook or exclude the experimental practices of the avant-garde artists. Look at it as a production of new meaning or sensuous technologies, as it were, rather than something ‘finished’ and ‘fitting’ the (largely) ocular/text-based production of knowledge in classical academia and/or archives. The Avant-garde is never finished. It is always messy, and still searching, I would say, for the right eyes and ears – even after 40, 60, 80 years.

I would like to propose to make experimental avant-garde practices enhance the debate within the research in & of the History and Theories of Avant-garde Art. My approach – and transdisciplinary take on the avant-garde – is based on the assumption that the avant-garde practices in e.g. technology and sound was, essentially, part of the formation of a ‘media art’ – a kind of off-road history-in-the-making running below the ‘official’ history-as-it-were of art.

The modalities of this subterranean ‘media art’, or experimental avant-garde, are:

My research project focuses on three levels: how and why sound art became unheard (of) in the ‘grand’ archives?; what archive-formats are needed to ‘store’ the unheard avant-gardes (so they do not become unheard (of) again?; and how it may enter the sphere of the general public?

The silence of sound art is symptomatic of certain cultural, aesthetic and scientific paradigms that are inherited via the knowledge systems and epistemologies that define the institutionalized archive competences (Joseph Beuys, Michel Foucault).

How to change the traditional status of sound art, in archives and elsewhere: it has more often than not gone silent – out of reach for researchers and a general public.

The Unheard Avant-gardes project, then, focuses on a critical re-activating of sound art as an experimental practice – getting and letting the silent Avant-gardes out of the boxes and off the shelves – and into a network of digital distribution where it may be accessed, exhibited and explored – listened to – in detail and in a context.

Thus, I will claim, that to be ’unheard’ is a fundamental condition and premise for performative and mediated art practices – in the ‘grand’ archives (in the sense, that they are not ‘on the shelves’) as well as in the construction of the cultural contexts and social memories (history). I refer to the unheard avant-garde in the sense that it is experimental and in the forefront of a cultural and technological transformation in its day. It formed it’s own networks and worked from there. However, I do not intend to refer to the ‘avant-garde’ in the sense of a specific (artistic) genre or group or period or style or whatever (that may be). My argument will be that the unheard condition, and the reappearance of unheard avant-gardes and their (somewhat) hidden networks, is something that ’mirrors’ a change in the modes and modalities of the production of knowledge in a distributed, post-digital culture. Thus, the unheard condition is as fundamental an aspect in the understanding of the formation of ‘grand’ archives, as it is a key-element in an analysis of change and transformation of paradigms – and how science and art performs in and respond to those transformations. On one level, the existence of unheard avant-gardes is the mark of mediated, fugitive and ephemeral strategies and tactics in the art practices that emerged in the late 1950s and during the 1960s. On another level, it is a true ontological gap – and the reappearance of the unheard avant-gardes may very well prompt us to rewrite history.

It is about time we put an ear to the archive ground.

To limit myself, I am putting a special focus on cases that turned up in my search after the particularly unheard (of) in the ‘grand’ archives: POEX65. First a note on how to search and identify the unheard avant-garde in (or, rather: outside) existing archives. I particularly looked for sound material from collaborative, performative, time-based, intermedia art, media art, and new media art projects from 1920s to present day; and I looked at small and private archives and triangulated what I found here – dates, persons, places, other artists – with the databases (or, in most cases, before 1983, written / printed records) of the Danish Broadcast Company and Statsbiblioteket (The Danish National Library).

I also put an ear to the collection of (inter)media art from 1950s and onwards at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Roskilde, of which I was the Curator between 1999 and 2008. This archive encompasses art, which is practicing “fusions of words, images and sounds”, often in different variations of performative, fluxid, conceptual, and mediated situations. The archival status is marked by varied and fugitive material, to say the least.

In my search I was also preoccupied with finding adequate framings for the categorization and contextualization of the archive (which was being established at the time and still is under construction), which (quite naturally, it seemed) proved inadequate on closer inspection and formulation. This certain affinity with the ear in the archive-context further sparked my interest in finding a systematics and methodology of the unheard; which, in turn, enhanced the attempt to implement a transdisciplinary practice and a sensuous technology into the core of the construction of the archive, allowing a dynamic flow of domains to establish themselves in a real time dialogue with an audience.

The sensuous material of sound, and the modalities of using the ears in new ways – exploring sonic perception – is the issue.

The ontology of an archive of media / sound art. Two ontological factors: 1) Instability of the material (and its contexts); 2) The material is in need of reactive strategies in order to be ’heard’ or merely ’noticed’ by recipients. The unheard status is an unwanted, but nevertheless actual status of most of the media art material that is existing in the archives.

Key-instabilities of sound-based / documented media art:

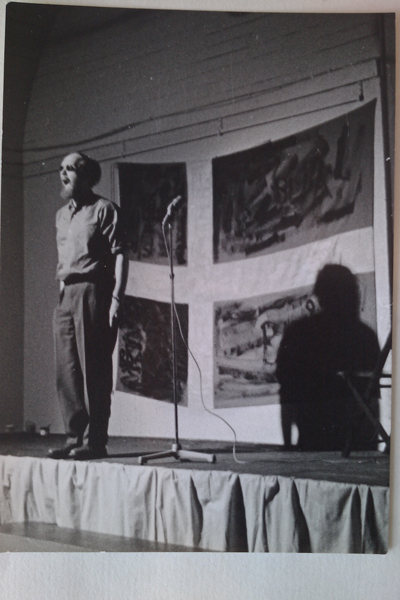

POEX 65 was a transdisciplinary experiment and event, which took place in ‘Den Frie Udstillingsbygning’ (The Independent Exhibition Building) in Copenhagen, December 10-20, 1965. Short for ’POetry EXperiment’, POEX 65 was an exhibition event curated and created by Danish artist Knud Hvidberg (1948-91). It aimed at breaking the boundaries of art genres, the false division of professional and amateur, as well as the autonomy of the ‘work of art’ through the active use of technological and mediated platforms such as Flexowriters, Punch Paper Poetry, and Electronic Visual Music. As such, it was a very important event in Scandinavian media art history with more than 80 participants from 5 countries – many of whom became part of the leading class of artists in Scandinavia.

Nevertheless, POEX 65 somehow was forgotten – and almost erased from the academic memory and public archives.

The Danish Broadcast Company (DR) did broadcast two programs, of which at least one was dedicated to POEX65: ‘A Sunday’s Walk w. Ella Wang’. However, the tape with this particular program was not in the archives of DR anymore – erased or reused, or?… no one can tell from the records. It is simply not there: Truly, an unheard avant-garde!

Long story short: I managed to locate a taped copy of the program in the private collection of one of the participants at POEX65, Kirsten Lockenwitz. From that tape, I managed to get a number of other information that led me to other recordings – and, suddenly, we had sound! Slowly, POEX65 came ‘alive’ again – for the first time in more than 40 years.

A very important part of the POEX65 event was the large number of experiments with cross-overs between musical artforms, from electronica to beat, to other artforms. This may also explain why the event never became part of official records or archives – and was erased from the DR broadcast-archive: It was transdisciplinary before that word even existed… it was way ahead of its time.

From the sources available to us, it seems fair to establish as a fact that five ‘stages’ were active in POEX 65: The ante-room (visual poetry), the Large Exhibition Room (Happenings and Live Music), the Centre Hall (Theatre), the expanded poetry space (+ Flexowriter), and the so-called ‘Co-ritus’ Environment by Jørgen Nash, Jens Jørgen Thorsen, Hardy Strid and Carl Magnus). (Hvidberg, Invite to participate in POEX 65 (in danish) 1965) (Barbusse 1991) (Rubin 1987)

From the program, it is possible to collect a list of ‘new’ concepts for these crossover categories:

This is just a loose collection of the terms mentioned in the program and in other material… and it shows, I think, the boundary breaking range that the POEX65 experiment had as well as the amount of collaborative artistic, creative and intellectual efforts that were put into the project. They really sought to work across the different artistic sections as well – Fluxus, Situationists, EKSskolen, DUT, as well as Jazz, Beat, and Electronic Music, and amateurs and technicians / engineers etc..

There was a heated discussion over the issue of artists’ autonomy, which was written down by Knud Hvidberg. The Danish EKSskole wanted a space they could control, however Knud Hvidberg did not want that – but insisted on an open space for everyone (including audience and ‘amateurs’) where anything might happen. Finally, the EKSskole did not participate as a group in POEX65, but a number of the artists (more loosely) associated with EKSskolen did participate individually.

It is a fact, however, that POEX65 did manage to bring together a large variety of artists from all kinds of art genres and ‘ideologies’. And they did work together in a number of ways. So far, I have identified some 128 ‘actors’ – artists, engineers, dancers, musicians, active audiences etc. – that were part of POEX65.

Together with Knud Hvidberg and the Danish Visual poet Vagn Steen, Karsten Vogel was at the ‘centre’ of the POEX65 event. Since the early 60s, and together with two other Danish semioticians and theoreticians, Peter Madsen and Per Aage Brandt (the latter was also a jazz pianist), Vogel had run an informal ‘study-group’ of new tendencies and theories of collaborative work-formats and actions of art. POEX65, in many ways, fed into the ideas and thoughts coming out of that group – who also participated with an event during the 10 days of activies. Vogel, however, had his main role as the experimental jass-musician who inspired the music-paint-light situated works happening at POEX65. A short clip from Jazz News in december 1965 was recovered from the personal archive of Kristen Lockenwitz, from which you may hear a ‘glimpse’ of what was going on. From this recording we hear Vogel and Brandt playing in a set-up, where certain ‘signals’ or ‘motions’ by the painters or light-artists, triggers a chaotic outbrake of sounds from a number of acoustic instruments.

Another important (artistically experimental) grouping was centred around Knud Hvidberg, William Soya, and Hans Sandmand. Together, those three artists had made a number of technology-based exhibitions and projects since 1957 – and, even though William Soya did not participate in person at POEX65, it is him who introduced the Flexowriter into the context, and experimented with how to use it for art purposes (see Flexowriter…). Hans Sandmand, however, participated with a number of interactive sound installations – most noteworthy, perhaps, the Radar which was standing (and turning) in the central hall where people entered the space. When you pushed a button on the radar, a voice said: ‘I am looking for the great intuition’. In another work, a pile of used car tires revealed a mirror when you looked down into the pile – and, as you looked, a voice recording was activated, saying: ‘poetry is something you carry in yourself’.

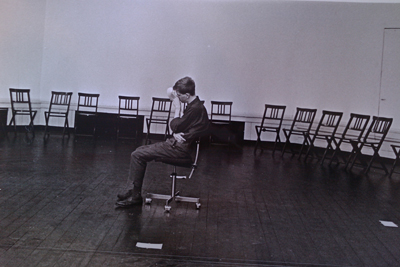

Not all artists participated on the same level of collaboration. Not everyone was ‘living out’ the radical ideas of Knud Hvidberg about collaboration, loss of autonomy, and the ‘exhibition as show’. Even so, they all seem to adopt some element of the conceptual framing of POEX65, like the processuality and audience participation. A good example would be the Danish Fluxus artist Eric Andersen. He contributed to POEX65 with a number of original works. Among them, ‘Her Bathing Suit Never got Wet’ and ‘I Regret the Bad Circumstances for Recording’ were all sound recordings and part of the ‘record bar’. ‘Opus 51’ was a performative event operating within the Fluxus methodology and aesthetics. Photos exist showing Eric Andersen sitting in the ‘central hall’, waiting for the audience to arrive. This event made the audience actively collaborate in realizing the work by running through a combination of operations based on rules defined by Andersen.

Time and chance would make Eric Andersen well-known (and well-represented) in Danish archives, whereas William Soya, Hans Sandmand, and Knud Hvidberg – despite their visionary and innovative use of technology and sound as media in visual arts at a very early stage (for DK as well as internationally) – more or less went into obscurity. Lost in translation… from moving media and sound to text and (still) images.

From all this, it appears that the Unheard Avant-gardes project is more than ‘just’ an archive project. It is as much a re-investigation of the fundamental conditions and status of ‘media art’ – the experimental avant-garde. As such, it may also be viewed as an attempt to re-configure (the academic ideas about) the relations between technology, media, and art, and write a theory of this re-configuration.

The reconfiguration is being put to a test when a number of ‘interfaces’ to the unheard avant-garde is presented (in a special section with focus on Scandinavia) at the exhibition TONKUNST – Sound as Medium for the Visual Arts in the 20th Century at ZKM (opens March 17, 2012).

The unheard avant-garde section will present three platforms. Each platform presents a notable and important ‘hub’ for the experimenting Scandinavian scene, in which technology, media and artistic practices are mixed and remixed into ‘sound art’.

The platforms are presented and designed by invited artists, as an independent work of art, or a new artistic platform, in such a way that the unheard avant-gardes get a voice in (the construction of) history.

For that purpose, I am operating with a methodology in three steps. 1) Instead of reENactments, which would focus on restaging artworks, I want to reactivate an entire event and context – including its ideas and methodologies. 2) I am dividing the reactivation-strategy into two modalities, Enacts and Reacts, which are focused on, either, the works and contexts of a single artist (enacts), or the idea and context of an entire event. 3) I am using ‘new’ media artists to reactivate the unheard media artists – adding a third element into the reactivation-strategy: that of re-working and re-actualizing works, technology, events and processes.

The first platform will focus on EMS (Elektronmusikstudion, Stockholm). Since 1964, EMS, formerly known as Electroacoustic Music in Sweden, prior to that known as Elektronmusikstudion, is the Swedish national centre for electronic music and sound art.

The second platform will reactivate the particular electronic aesthetics of Finnish Electronic Music Studio & Errki Kurenniemi (FIN). Errki Kurenniemi’s Electronic Music Studio was set up in 1962 with the vision of an automated composition system. In the 1960’s Kurenniemi built Integrated Synthesiser and in the 70’s, a series of custom built music instruments called DIMI.

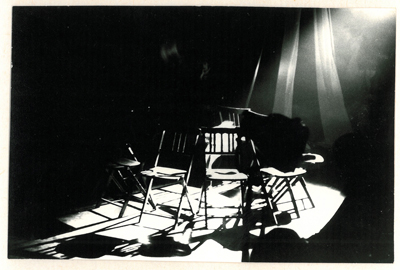

The third platform will re-activate POEX65. It will include reactive radar, collaborative chairs, and a giant TONEHEAD as sensuous interface for an archive of the unheard avant-garde.

It is from this unheard status of experimental media art that the re-activation of the unheard avant-gardes finds its momentum: Not only in giving the unheard a voice in a number of ways, but also in addressing some fundamental issues concerning the way new transdisciplinary domains are renegotiated across disciplines and boundaries of competences. History will never be the same (again).

For more information visit: http://www.sondergart.dk