First published in Remediating the Social 2012. Editor: Simon Biggs University of Edinburgh. Pages 69-74

—-

The acceleration of technological development in contemporary society has a direct impact on our everyday lives as our behaviours and relationships are modified via our interactions with digital technology. As artists, we have adapted to the complexities of contemporary information and communication systems, initiating different forms of creative, network production. At the same time we live with and respond to concerns about anthropogenic climate change and the economic crisis. As we explore the possibilities of creative agency that digital networks and social media offer, we need to ask ourselves about the role of artists in the larger conversation. What part do we play in the evolving techno-consumerist landscape which is shown to play on our desire for intimacy and community while actually isolating us from each other. (Turkle 2011) Commercial interests control our channels of communication through their interfaces, infrastructures and contracts. As Geert Lovink says ‘We see social media further accelerating the McLifestyle, while at the same time presenting itself as a channel to relieve the tension piling up in our comfort prisons.’ (2012: 44)

Many contemporary artists who take the networks of the digital information age as their medium, work directly with the hardware, algorithms and databases of digital networks themselves and the systems of power that engage them. Inspired by network metaphors and processes, they also craft new forms of intervention, collaboration, participation and interaction (between human and other living beings, systems and machines) in the development of the meaning and aesthetics of their work. This develops in them a sensitivity or alertness to the diverse, world-forming properties of the art-tech imaginary: material, social and political. By sharing their processes and tools with artists, and audiences alike they hack and reclaim the contexts in which culture is created.

This essay draws on programmes initiated by Furtherfield, an online community, co-founded by the authors in 1997. Furtherfield also runs a public gallery and social space in the heart of Finsbury Park, North London. The authors are both artists and curators who have worked with others in networks since the mid 90s, as the Internet developed as a public space you could publish to; a platform for creation, distribution, remix, critique and resistance.

Here we outline two Furtherfield programmes in order to reflect on the ways in which collaborative networked practices are especially suited to engage these questions. Firstly the DIWO (Do It With Others) series (since 2007) of Email Art and co-curation projects that explored how de-centralised, co-creation processes in digital networks could (at once) facilitate artistic collaboration and disrupt dominant and constricting art-world systems. Secondly the Media Art Ecologies programme (since 2009) which, in the context of economic and environmental collapse, sets out to contribute to the construction of alternative infrastructures and visions of prosperity. We aim to show how collaboration and the distribution of creative capital was modeled through DIWO and underpinned the development of a series of projects, exhibitions and interventions that explore what form an ecological art might take in the network age.

In common with many other network-aware artists the authors are both originators and participants in experimental platforms and infrastructures through processes of collaboration, participation, remix and context hacking. As artists working in network culture we work between individual, coordinated, collaborative and collective practices of expression, transmission and reception. These resonate with political and ethical questions about how people can best organise themselves now and in the future in the context of contemporary economic and environmental crisis.

Though this essay draws primarily on artistic and curatorial practices it also makes connections with the histories and theories that have informed its development: attending to the nature of co-evolving, interdependent entities (human and non-human) and conditions, for the healthy evolution and survival of our species (Bateson 1972); producing diverse (hierarchy dissolving) social ecologies that disarm systems of dominance (Bookchin 1991, 2004); and seeking new forms of prosperity, building social and community capital and resilience as an alternative to unsustainable economic growth. (Bauwens 2005) (Jackson 2009)

Furtherfield’s mission is to explore, through creative and critical engagement, practices in art and technology where people are inspired and enabled to become active co-creators of their cultures and societies. We aim to co-create critical art contexts which connect with contemporary audiences providing innovative, engaging and inclusive digital and physical spaces for appreciating and participating in practices in art, technology and social change.

The following artworks, researched, commissioned and exhibited by Furtherfield this year, offer a range of practices exemplifying this approach. A Crowded Apocalypse [1] by IOCOSE deploys crowd-sourced workers in the production of staged, one-person protests (around the world) against collectively produced, but fictional, conspiracies. This is a net art project that exploits crowd sourcing tools to simulate a global conspiracy. The work exploits the fertility of network culture as a ground for conspiracy theories which, in common with many advertisements, are persuasive but are neither ultimately provable or irrefutable (Garrett 2012).

A series of distributed performances called Make-Shift, by Helen Varley Jamieson and Paula Crutchlow, is a collective narrative about the human role in environmental stresses, developed with participants who build props for the ‘show’ using all the plastic waste they have produced that day. Makeshift is an ‘intimate networked performance that speaks about the fragile connectivity of human and ecological relationships. The performance takes place simultaneously in two separate houses that are connected through a specially designed online interface.’ [2]

Moving Forest London 2012 [3], initiated by AKA the Castle (coordinated by Shu Lea Cheang), employs the city of London as it prepares for the grand spectacle of the 2012 Olympic Games, expanding the last 12 minutes of Kurosawa’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth “Throne of Blood” (1957), with a prelude of 12 days, and durational performance of 6 acts in 12 hours. The Hexists (artists Rachel Baker and Kayle Brandon) perform Act 0 of this sonic performance saga, with 3 Keys – The River Oracle, a game of chance and divination [4].

Other notable works in this vein include Embroidered Digital Commons [5] by Ele Carpenter; Invisible Airs and Data Entry [6] by Yoha; Web2.0 Suicide Machine [7] by _moddr_ and Fresco Gamba; The Status Project [8] by Heath Bunting; and Tate a Tate [9], an interventionist sound work by Platform, infiltrating one of the largest art brands of the nation using a series of audio artworks distributed to passengers on Thames River boats, to protest the ongoing sponsorship of Tate Modern exhibitions by British Petroleum. Also relevant is the realm of ludic digital art practices that facilitate new socially engaged aesthetics and values such as Germination X [10] by FO.AM and Naked on Pluto [11] by Dave Griffiths, Marloes de Valk, Aymeric Mansoux.

The term “DIWO (Do It With Others)” was first defined in 2006 on Furtherfield’s collaborative project Rosalind – Upstart New Media Art Lexicon (since 2004) [12]. It extended the DIY (Do It Yourself) ethos of early (self-proclaimed) ‘net art heroes’, who taught themselves to navigate the web and develop tactics that intervened in its developing cultures.

The word “art” can conjure up a vision of objects in an art gallery, showroom or museum, that can be perceived as reinforcing the values and machinations of the victors of history as leisure objects for elite entertainment, distraction and/or decoration – or the narcissistic expression of an isolated self-regarding individual. DIWO was proposed as a contemporary way of collaborating and exploiting the advantages of living in the Internet age that connected with the many art worlds that diverge from the market of commoditised objects – a network enabled art practice, drawing on everyday experience of many connected, open and distributed creative beings.

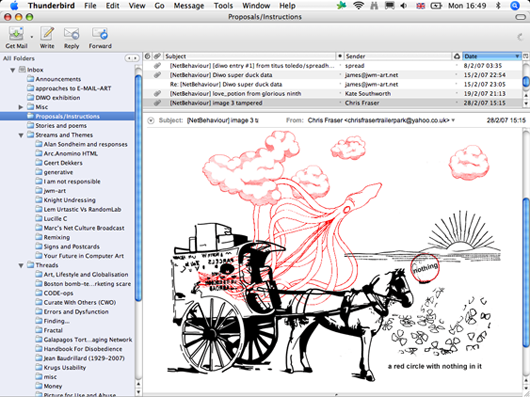

Mail box showing Netbehaviour contributions to DIWO Email Art project 2007

DIWO formed as an Email Art project with an open-call to the email list Netbehaviour, on the 1st of February 2007. In an art world largely dominated by elite, closed networks and gatekeeping curators and gallerists, Mail Art has long been used by artists to bypass curatorial restrictions for an imaginative exchange on their own terms.

Peers connect, communicate and collaborate, creating controversies, structures and a shared grass roots culture, through both digital online networks and physical environments. Strongly influenced by Mail Art projects of the 60s, 70s and 80s demonstrated by Fluxus artists’ with a common disregard for the distinctions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ art and a disdain for what they saw as the elitist gate-keeping of the ‘high’ art world…’ [13]

The co-curated exhibition of every contribution opened at the beginning of March at HTTP Gallery [14] and every post to the list, until 1st April, was considered an artwork – or part of a larger, collective artwork – for the DIWO project. Participants worked ‘across time zones and geographic and cultural distances with digital images, audio, text, code and software. They worked to create streams of art-data, art-surveillance, instructions and proposals in relay, producing multiple threads and mash-ups. (Catlow and Garrett, 2008)

‘The purpose of mail art, an activity shared by many artists throughout the world, is to establish an aesthetical communication between artists and common people in every corner of the globe, to divulge their work outside the structures of the art market and outside the traditional venues and institutions: a free communication in which words and signs, texts and colours act like instruments for a direct and immediate interaction.’ (Parmesani 1977)

So it made sense that the first DIWO project should be a mail art project that utilised email, enabled by the Internet; a public space with which anyone with access to a computer and a telephone line could use to publish. Because an email could be distributed (with attachments or links) to the inboxes of anyone subscribed to the Netbehaviour email list, subscribers’ inboxes became a distributed site of exhibition and collaborative art activity: such as correspondence, instruction, code poetry, software experiments, remote choreography, remixing and tool sharing.

This and later DIWO projects used both email and snail-mail and (in line with the Mail Art tradition) undertook the challenge of exhibiting every contribution in a gallery setting.

The DIWO Email art project was liberally interspersed with off-topic discussions, tangents and conversational splurges, so one challenge for the co-curators was to reveal the currents of meaning and the emerging themes within the torrents of different kinds of data, processes and behaviour. Another challenge was to find a way to convey the insider’s – that is the sender’s and the recipient’s – experience of the work. These works were made with a collective recipient in mind; subscribers to the Netbehaviour mailing list. This is a diverse group of people; artists, musicians, poets, thinkers and programmers (ranging from new-comers to old-hands) with varying familiarity with and interest in different aspects of netiquette and the rules of exchange and collaboration. This is reflected in the range of approaches, interactions and content produced.

In a number of important ways the email inbox guarantees a particular kind of freedom for the DIWO art context, as distinct from the exchange facilitated by the ubiquitous sociability, ‘sharing’ and ‘friendship’ offered by contemporary social media. Facebook, Myspace, Google+, etc, provide interfaces that are designed to elicit commercially valuable meta-data from their users. They are centrally controlled, designed to attract and gather the attention of its users in one place in order to monitor, process and interpret social behaviour and feed it to advertisers. As demonstrated during the disturbances of the Summer of 2011, these social media are an extension of the Panoptican and can also become tools of state surveillance and punishment as Terry Balson discovered on being detained for 2 years after being found guilty of setting up a Facebook page in order to encourage people to riot. (BBC News, 2012)

The DIWO Email Art and co-curation project is fully described and documented elsewhere [15] but it is outlined here as it gives an example of how our networked communities may intersect with everyday experience and with mainstream art worlds while also creating their own art contexts. We may be playful, critical, political and may work as possible co-creators with all the materials (stuff, ideas, processes, entities – beings and institutions – and environments) of life. This DIWO approach provides the fundamental ethos for the Furtherfield Media Art Ecologies programme.

Furtherfield’s Media Art Ecologies programme (since 2009) brings together artists and activists, thinkers and doers from a wider community, whose practices address the interrelation of technological and natural processes: beings and things, individuals and multitudes, matter and patterns. These people take an ecological approach that challenges growth economics and techno-consumerism and attends to the nature of co-evolving, interdependent entities and conditions. They activate networks (digital, social, physical) to work with ecological themes and free and open processes.

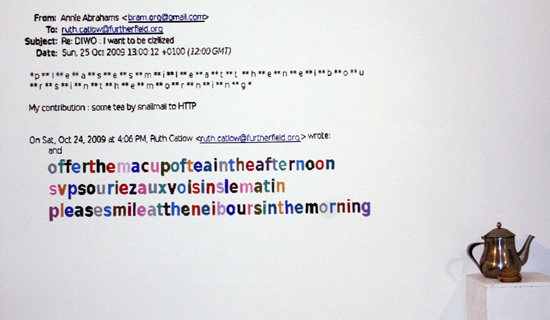

The programme has included exhibitions such as Feral Trade Café by Kate Rich and If Not You Not Me by Annie Abrahams, an art world intervention by the authors We Won’t Fly For Art and workshop programmes such as Zero Dollar Laptop workshops (in partnership with Access Space in Sheffield). It has supported research projects such as Telematic Dining by Pollie Barden and developmental artist residencies, such as Make-Shift by Helen Varley Jamieson and Paula Crutchlow.

These projects and practices have a number of things in common:

Through the Internet we all now have access to data about historic and contemporary carbon emissions. We also find visualisations of this data that provide concise and accessible graphical arguments for thinking, feeling and acting in a coordinated way at this historical moment [17] [18].

Data shows an exponential rise in global carbon emissions since the 1850s, starting with the UK. UK carbon emissions have dropped as a percentage of global emissions by region (CDIAC 2010). At the same time the quantity of carbon dioxide emitted by the UK has steadily increased since the start of the industrial revolution to annual levels now higher than 500 million tonnes (Marland, Boden and Andres 2008). This data shows how successful the UK was, during the industrial revolution, at spreading the production methods that would turn out to promote a model of sole reliance on economic growth and fossil fuels. The logic and infrastructures of capitalism are now collapsing in tandem with the environment (Jackson 2009). At the same time networked technologies and behaviours are proliferating. Social and economic transactions take place at increased speed but our existing economic and social models are unsustainable and the consequences of continuing along the current path appear catastrophic for the human species (Jackson 2009). This is a critical moment to reflect on how the technologies we invent and distribute will form our future world.

Michel Bauwens, of the Foundation for Peer to Peer Alternatives, works with a network of theorists, activists, scientists and philosophers to develop ideas and processes to move beyond the pure logic of economic growth [19]. He observes that by transposing what has been learned by sharing the production and use of immaterial goods, such as software, with strategies for developing sharing in other productive modes, the community comes to own its own innovations, rather than corporations. This puts peer production at the core of civil society. The fabrication laboratory or ‘fab lab’ system, developed at MIT in collaboration with the Grassroots Invention Group and the Center for Bits and Atoms, offers an example; a small-scale workshop that facilitates personal fabrication of objects including technology-enabled products normally associated with mass production. The lab comprises a collection of computer controlled tools that can work at different scales with various materials. Early work on the Open Source car shows how open, distributed design and manufacturing points to a possible end of patenting and built in obsolescence; constituent principles of our unsustainable consumer-based society. (Bauwens 2012)

‘[Bauwens] recognises that peer to peer production is currently dependent on capitalism (companies such as IBM invest huge percentages of their budgets into the development of Free and Open Source Software) but observes that history suggests a process whereby it might be possible to break free from this embrace. He suggests that by breaking the Free Software orthodoxy it would be possible to build a system of guild communities to support the expansion of mission oriented, benefit-driven co-ops whose innovations are only shared freely with people contributing to the commons. In the transition to intrinsically motivated, mass production of the commons, for-profit companies would pay to benefit from these innovations.’ (Catlow 2011)

A peer to peer infrastructure requires the following set of political, practical, social, ethical and cultural qualities: distribution of governance and access to the productive tools that comprise the ‘fixed’ capital of the age (e.g. computing devices); information and communication systems which allow for autonomous communication in many media (text, image, sound) between cooperating agents; software for autonomous global cooperation (wikis, blogs etc); legal infrastructure that enables the creation and protection of use value and, crucially to Bauwens’s P2P alternatives project, protects it from private appropriation; and, finally, the mass diffusion of human intellect through interaction with different ways of feeling, being, knowing and exposure to different value constellations. (Bauwens 2005)

These developments in peer to peer culture provide a backdrop to the projects presented as part of the Media Art Ecologies programme which, in turn, proposes that a focus on the networked cultures in which the work is produced, supports ecological ways of thinking, privileging attention to complex and dynamic interaction, connectedness and interplay between artist viewer/participant and distributed materials. Its projects have been developed within independent communities of artists, technologists and activists, theorists and practitioners centered around Furtherfield in London (and internationally, online), Cube Microplex in Bristol and Access Space in Sheffield. They identify the simultaneous collapse of the financial markets and the natural environment as intrinsically linked with human uses of, and relationships with, technology. They take contemporary cultural infrastructures (institutional and technical), their systems and protocols, as the materials and context for artistic production in the form of critical play, investigation and manipulation. This work, at the intersection of artistic and technical cultures, generates alternative spaces and new perspectives; alternative to those produced by (on the one hand) established ‘high’ art-world markets and institutions and (on the other) the network of ubiquitous user owned devices and social apps. These practices play within and across contemporary networks (digital, social and physical), disrupting business as usual and the embedded habits and attitudes of techno-consumerism.

We will end this essay by describing an early project developed as part of this programme, Feral Trade Café [20] by Kate Rich, an exhibition that was also a working café. Feral Trade Café served food and drink traded over social networks for 8 weeks in the Summer of 2009 and exhibited a retrospective display of Feral Trade goods alongside ingredient transit maps, video, bespoke food packaging and other artifacts from the Feral Trade network. Since 2003 participants in the project (usually travelling artists and curators) have acted as couriers, carrying edible produce around the world with them on trips they are taking anyway and delivering them to depots (friends’ and colleagues’ flats or workplaces), mostly independent art venues in Europe and North America. Rich has crafted a database through which couriers can log their journeys, tracking the details of sources, shipping and handling for all groceries in the network ‘with a micro-attention usually paid to ingredient listings’ (Catlow 2009). This database [21] is at the heart of the artwork, with special attention given to the day to day challenges and obstacles met in its distribution – tracking the on-the-fly street level tactics employed, out of necessity, by a distribution network with no staff, vehicles, storage facilities or business plan.

‘Courier Report FER-1491 DISPATCHED: 13/05/09 DELIVERED: 15/05/09 – ali jones spent a few hours trying to start a car using various techniques. eventually got it moving with a push start with the help of a stranger who was leaving behind a night of print-making.convoyed to cube where friend took parcel in her van while i parked dubious car at garage for fixing.’ [21] (Feral Trade Courier, 2009)

The café stocked and served a selection of Feral Trade products from a menu including coffee from El Salvador, hot chocolate from Mexico and sweets from Montenegro, as well as locally sourced bread, cake, vegetables and herbs. Diverse diners – local residents and long-distance lorry drivers (from Poland and Germany) – were served their food along with waybills (drawing information from the database) documenting the socially facilitated transit of goods to their plate.

The invitation to the exhibition promised visitors a convivial setting from which to “contemplate broader changes to our climate and economies, where conventional supply chains (for food delivery and cultural funding) could go belly up.” The café provided a local trading station and depot for the Feral Trade network, and a meeting place for local community food activists for research and discussion. It’s worth noting that a year later a Government Spending Review announced a cut of nearly 30% to the Arts Council of England’s budget. (BBC News 2010) Two years later global food prices were up by over 40% and set to rise another 30% in the next 10 years. (Neate 2011). A number of small new projects continue to develop from meetings between the gallery community and local community activist groups working on sustainability issues.

The materials and methods employed by this artwork, that is also a functioning café, are diverse and non-standard. The café is not scaleable and generates no jobs or surplus, let alone profit. It may build ‘social capital’, what Bordieu defines as a form of capital ‘made up of social obligations (‘connections’) which is convertible in certain conditions into economic capital and may be institutionalised in the form of a title of nobility.’ (Bordieu1986) However, it is uncertain whether this will apply to Rich as any ‘nobility’ she might acquire is undermined by her purposeful maintenance of the project’s ambiguous status as an artistic project.

For this essay we present Feral Trade Café alongside Bauwens’ proposal for alternative P2P infrastructures. We propose that while the work is not a design, formula or practical, alternative business model (either for an artwork or a café) for mass adoption, it can be considered an ecological system for ‘mass diffusion of intellect’ (Bauwens 2005). Interaction with the project engages participants in different ways of sensing, operating and valuing the world. It is a most inefficient way of trading.

The work poses strange questions as it oscillates between artwork (sensual, expressive, rhetorical) and catering (utilitarian, literally nourishing) and to consider the meaning of our lives and vocations in local communities and a functional future society. ‘Understanding that prosperity consists in part in our capabilities to participate in the life of society demands that attention is paid to the underlying human and social resources required for this task.’ (Jackson 2009: 182) Feral Trade focuses our attention on the truly pleasurable aspects of social exchange that are lost in our quest for affluence. ‘Creating resilient social communities is particularly important in the face of economic shocks.[…] The strength of a community can make the difference between disaster and triumph in the face of economic collapse.’ (Jackson 2009: 182)

Feral Trade is both art and a lived, alternative co-created system for trading and serving food that refuses commercial exploitation, contributes meaning and strengthens bonds across an existing community. A distinctive, memorable and sensual way for people to interact, to socialise and savour the socio-political ingredients of a meal eaten while discussing strategies for avoiding ethical discomfort. Most powerfully, it is a lived critique and reinvention of a fundamental aspect of everyday life (feeding ourselves) through the subtle tactics of manipulation and play (by its many participants).

It is our contention that by engaging with these kinds of projects, the artists, viewers and participants involved become less efficient users and consumers of given informational and material domains as they turn their efforts to new playful forms of exchange. These projects make real decentralised, growth-resistant infrastructures in which alternative worlds start to be articulated and produced as participants share and exchange new knowledge and subjective experiences provoked by the work.

Conclusion – Ecological Media Art promotes participation in social ecology

Social scientist Tim Jackson has shown that the establishment of ever more efficient and productive systems of control and growth, owned by fewer, more centralised agents, is both unjust and environmentally unsustainable (2009). The reverse also applies; that the distribution of freedoms and access to sustenance, knowledge, tools, diverse experience and values improves the resilience of both our social and environmental ecologies. (Bateson 1972) (Bookchin 1991) (Jackson 2009)

Ecological media artworks turn our attention as creators, viewers and participants to connectedness and free interplay between (human and non-human) entities and conditions. It builds on the DIWO ethos. On the one hand we resist the elitist values and infrastructures of the mainstream art world and develop our own art context, on our own terms, according to the priorities of a collaborating community of creative producers (which may include diverse participants and audiences). On the other, we deal critically with the monitored and centrally deployed and controlled interfaces of corporate owned social media; wherever possible working with Free and Open Source Software to privilege commons-based peer produced artworks, tools, media and infrastructure.

Humanity needs new strategies for social and material renewal and to develop more diverse and lively ecologies of ideas, occupations and values. For this to happen more of us need to be able to freely participate more deeply in diverse artistic or poetic and technical world-forming processes and to exchange what we create and learn.

‘Those who share our ‘analysis of the contemporary political moment may also perceive a possible role for themselves in the generation of mutual commons-based interfaces for engagement that go beyond solely textual formats to arrays of performance, narrative (fact and fiction), image, sound, database, algorithm, music, theory, sculpture – to explicitly re-conceive inalienable social relations’ (Catlow 2011)[23].

Remediating the Social 2012. Editor: Simon Biggs University of Edinburgh. Published by Electronic Literature as a Model for Creativity and Innovation in Practice, University of Bergen, Department of Linguistic, Literary and Aesthetic Studies PO Box 7805, 5020 Bergen, Norway.

Book is available for download as PDF in a full version suitable for print or screen reading (14mb) and a somewhat smaller file size screen-only version (11mb) http://www.elmcip.net/story/remediating-social-e-book-released

Bateson, G., 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind University of Chicago and London: Chicago Press

Bauwens, 2005. The political economy of peer production. Available [online] at http://www.informatik.uni-leipzig.de/~graebe/Texte/Bauwens-06.pdf [Accessed 28th June 2012]

Bauwens, 2012. Blueprint for P2P Society: The Partner State & Ethical Economy. Shareable. Available [online] at http://www.shareable.net/blog/a-blueprint-for-p2p-institutions-the-partner-state-and-the-ethical-economy-0 [Accessed 28th June 2012]

BBC News, 2010. Arts Council’s budget cut by 30%. 20 October 2010 Last updated at 17:40. Available [online] at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-11582070 [Accessed 20th December 2011]

BBC News, 2012. Facebook riots page man Terry Balson detained. 8 May 2012 Last updated at 19:57. Available [online] at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-11582070 [Accessed 28th June 2012]

Bookchin, M., 1991. The Ecology of Freedom. The emergence and dissolution of hierarchy. Montreal, New York: Black Rose Books.

Bookchin, M., 2004. Post- Scarcity Anarchism. Edinburgh, Oakland, West Virginia: AK Press.

Bordieu, P., 1986. The Forms of Capital. English version first published in Richardson J.G., 1986. Handbook for Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, pp. 241–258. Available [online] at http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/fr/bourdieu-forms-capital.htm [Accessed 29th June 2012]

Catlow, R., and Garrett, G., 2008. Do It With Others (DIWO) – E-Mail Art in Context. Vague Terrain. Available [online] at http://vagueterrain.net/journal11/furtherfield/01 [Accessed 26th June 2011]

Catlow, R., 2009. Ecologies of Sustenance. Catalogue essay for Feral Trade Café – an exhibition that was also a working café by Kate Rich. 13 June – 2 Aug 2009, HTTP Gallery. Furtherfield, London.

Catlow, R., 2011. Re-rooting digital culture at ISEA 2011. Available [online] at http://www.furtherfield.org/blog/ruth-catlow/re-rooting-digital-culture-isea-2011 [Accessed 28th June 2012]

Catlow, R., 2012. We Won’t Fly For Art: Media Art Ecologies. Culture Machine, Paying Attention, July 2012

CDIAC, Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, 2010. Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions. Columbia University. Available [online] at http://www.columbia.edu/~mhs119/Emissions/Emis_moreFigs [Accessed 26th June 2012].

Feral Trade Courier, 2009. Import, export database created by artist Kate Rich. Available [online] at http://www.feraltrade.org [Accessed 26th June 2012]

Garrett M., 2012. CROWDSOURCING A CONSPIRACY an Interview with IOCOSE. Available [online] at http://www.andfestival.org.uk/blog/iocose-garrett-interview-furtherfield [Accessed 28th June 2012]

Garrett M., 2012. Heath Bunting, The Status Project & The Netopticon Available [online] at http://www.furtherfield.org/features/articles/heath-bunting-status-project-netopticon [Accessed 28th June 2012]

Jackson, T., 2009. Prosperity Without Growth, Economics for a Finite Planet. London: Earthscan

Lovink, G., 2012. Networks Without a Cause. A Critique of Social Media. University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Marland, G., T.A. Boden, and R.J. Andres. 2008. Global, Regional, and National Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions. In Trends: A Compendium of Data on Global Change. Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, Tenn., U.S.A.

Neate, R., 2011. Food price explosion ‘will devastate the world’s poor’. Guardian, Friday 17 June 2011 18.42 BST. Available [online] at http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2011/jun/17/global-food-prices-increase-united-nations [Accessed 20th December 2011]

Parmesani, L., 1997. Poesia visiva, in L’arte del secolo – Movimenti, teorie, scuole e tendenze 1900-2000 . Giò Marconi – Skira, Milan 1997

Turkle, S., 2011. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. Basic Books