The American artist Patrick Lichty is best-known for his works with digital media: as part of the activist group RT Mark and as designer of digital animation movies for their follow-up The Yes Men, he has been recognized as a net artist with a political bend. He has been working with digital media since the 1980s, and has created works with video, for the Web and for Second Life.

At his solo show “Artifacts” at DAM Galerie in Berlin however, the artist, who is teaching at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee and has recently published a book with theoretical essays, does not show media works, but tapestries.

Tapestries? In the following interview Lichty talks about his return to traditional art techniques.

Tilman Baumgärtel (TB): Patrick, you are known for your work with media, and you have created 3D animations, Internet and Second Life works. But at your recent shows both in Berlin and New York you show works in much more traditional artistic media: drawings in New York, tapestries in Berlin. Why the return to these time-honoured modes of production?

Patrick Lichty (PL): I’ve been sitting in front of the screen for almost 30 years, and I’ve been blind several times in my life. This leads me to my belief that, “Mediation is reality.” I have artificial lenses, and I don’t know whether I see the world as it is. I feel like I have this cyborg vision, like I am slightly alien. I’ve had this feeling all my life.

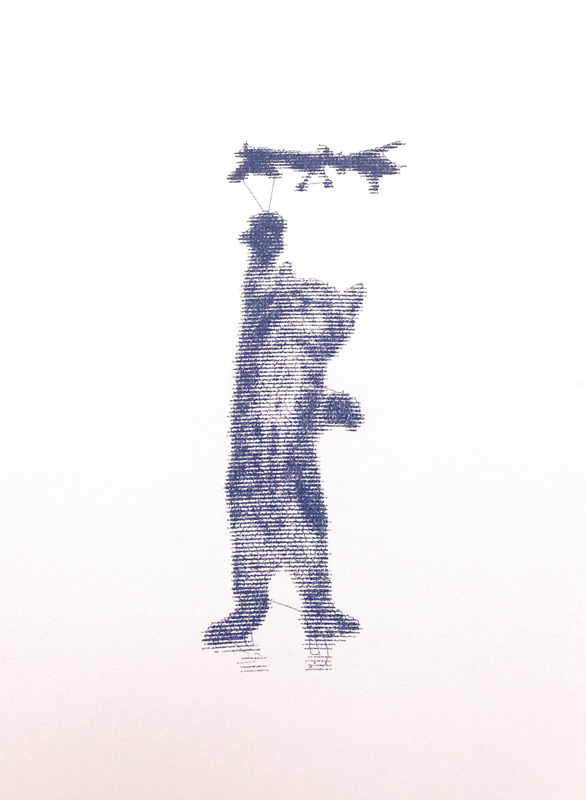

So on the one hand, I have tried to create an alternative reality through mediation, or maybe to see the world for what it is through mediation. That is what happens with the Yes Men for instance: I am helping Mike and Andy to create alternative realities for our fictitious corporate campaigns. And on the other hand I am interested in what Marcus Novak from University of California Santa Barbara calls “Evergence” where virtual things that never existed except in the virtual manifest in the physical. It is almost like William Gibson’s novel “All Tomorrow’s Parties”, where the “printed” virtual J-pop idol Rei Toei idol jumps out of the nano-replicator, and says “Hello”, even though she never existed. I am interested in the tangible digital that manifests from the potential virtual…

TB: The tangible digital?

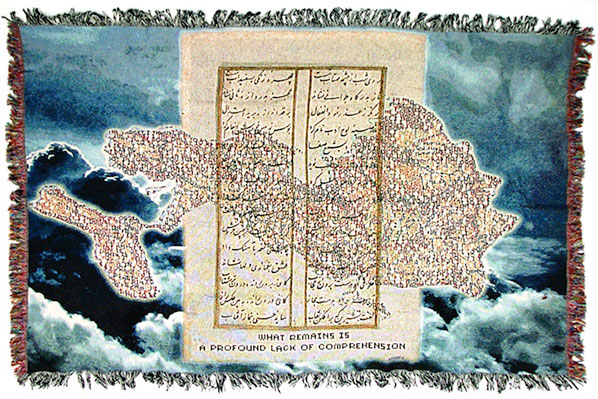

PL: Well, the idea of taking code, and turning it into 3D-objects, or taking things from Second Life and creating artifacts, and I use the US spelling as a double reference to “artifacting” or pixelization of an edge. The whole show here in Berlin is meant to introduce people to this gigantic body of work that I created in the realm of the digital as a cultural explorer, and that the contemporary art world doesn’t know much about, a bit at a time. What we have in the show are artifacts based on some of my more art world-friendly works. Some of my other pieces are definitely not art-world-friendly. I have done tons of prints and tons of video, that can be presented in a show, but a lot of my web work utterly and completely resists any kind of exhibition.

In the show in New York I have ten Roman-Verostko-like plotter prints of random internet cats, which is sort of my answer to post-internet art. By the way, you know what sold? The kitten swatting at the drone flying over it.

TB: How did you pick the motifs for the tapestry that is on display here in Berlin?

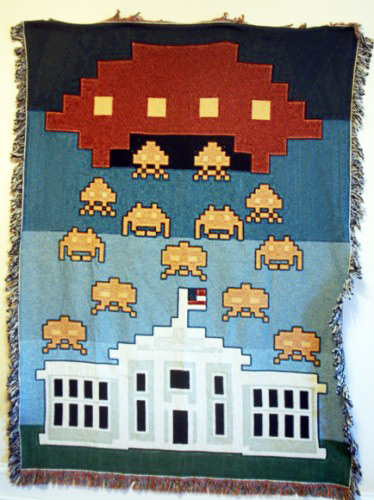

PL: This images come from certain key points in my practice in the last ten years. I send these files to a mill in South Carolina, and they fabricate the tapestry based on my image. These images are the ones that resonate with me very strongly. There is one that is called “Orange Alert”, which has the Space Invaders from the computer game attacking the White House, that I translated into this huge tapestry. It is based on a painting that his since been destroyed, and I think it is actually more interesting that way. We used to have this color code system in the US. “Orange” meant “You better be really scared”, and “Red” meant “You can kiss your ass good-bye.” Five years after 7/11, all the airports in the US were on Orange Alert, and nobody cared.

TB: Weaving was among the first crafts that were mechanized, and the mechanical looms were among the first machines that were controlled with early forms of punched card that in the early days of computing were the first form of memory storage. Is that the reason why you translated these images into tapestry?

PL: On the one hand I am referring to the old, grand art of tapestry weaving, and, maybe, playing a little bit to the gallery. It is a way to express the digital in a very certain kind of materiality that I find interesting and that is historically relevant to our heritage. They are simply a beautiful way to express digital content. And they are easy to display.

TB: The next thing we know is that you will be sitting on the loom again, rather than having these tapestries made for you…

PL: Well, I did that as a child. My mother was an artist and I worked on a loom with her. So there are specific incidents in my life that logically led me to create this work. I am not doing it, because it is hip, or cheap…

TB: …or could be shown in a gallery…

PL: No. There have been specific moments in my life that lead me to this, it was not merely a gallery move, although it made things easier.

The other thing that I am doing is that I am starting to place Augmented Reality on them, but that is not in this show. With the other Augmented works, like my Kenai Tapestry, you can take a device, bring up an app, and you look at it through the device, which recognizes the piece and then the virtual content comes out. The only piece like this in the DAM Berlin show that is like this is one piece that has a QR code on it that just says http:// and it sends you to a 404-error page. It is a Jodi-like piece. I don’t have to keep a server. It is something that actually does engage with technological devices, but I do not have to do this horrible upkeep.

I did a piece called “Grasping @ Bits” in 2000 for which I got a honourable mention for the Golden Nica at Ars Electronica. It was this terribly complex hypertext-essay with hyper browsers and multiple reading paths, that had to do with activism and net art. I did this 15 years ago, and it is almost broken. Unless QR codes become totally defunct, I hope the 404 piece will work for a long time. We still have barcodes after how many years?

TB: In the 1990s, people were thinking that we would somehow upload ourselves into “cyberspace”, as in the “Matrix” movies. What seems to happen now is exactly the opposite: The virtual seems to re-materialise by manifesting itself in physical space, via 3D printers, smartphones etc.

PL: Instead of “The Matrix” it is more like in “All Tomorrow’s Parties” or “The Diamond Age”, in which we have machines that turn everything into what Bruce Sterling refers to as “gomi” or clutter/trash in Japanese. We have this whole explosion of digital content becoming physical again, but to quote Sterling again, most of them are meaningless technical exercises, or “Crapjects”.

This whole issue of re-materialization and corporeality from media to physical objects is of growing importance to me. We are made of material/flesh (points to his arm) rather than this (points to a computer). Moravec hasn’t come true yet; we are not uploading ourselves anytime soon…

I had a phase around 2005, where nobody heard from me much for a year or two because I wanted to reconcile myself with material. I didn’t do much media art, it was mostly material practice. That was when I started to work with iron casting and weaving. I have been interested in the Jacquard loom and 3D printing since 2004, but I am only showing much of that now. I did a 3D representation of a gif in 2005, where the black and white value determine the height of the different pixels. White is high, black is low. I had that cast in iron. It is from a series called “8 Bit Or Less”, that reflected on my blindness. I took samples from the different series of my work and experimented with translating them into a physical form. The idea is that mediation becomes physical reality, and the format of this show is a survey of various works. I thought that was the most logical way yo introduce people to a substantial body of work quickly but in an accessible way.

TB: Let’s talk about your involvement with groups like RTMark, the Yes Men or Second Front. You said that you were interested in creating alternative realities. Was that the reason why you ghelped create these groups?

PL: I have always been a leftist, who – ironically – tries to survive on his work. That´s why I was attracted to the anti-corporate bent of RTMark and the Yes Men.

A little bit back-story is in order here: Imagine an electrical engineer raised by artists and then taught how to do Critical Theory by Ph.D.s in Sociology and Theatre History, and what you get is me.

I actually worked an electronic engineer for a while, and did not go to art school until I needed a degree to be an academic, as a lot of early New Media artists did. My mother was an artist, she trained me in the arts. I got my first electronics kit in 1970, when I was eight years old. And then I got my first computer and started drawing on it in 1978 – that was an Atari 800 (I still have it). And I got on the internet in 1983, 11 years before the web. So who is the “digital native” here?

I was doing computer art in the 1980s, but only started showing my work in 1990. By that time I had fallen in love with a theatre historian and through her I had fallen in love with theory. My best friend even to this day, Jonathon Epstein, is a sociologist, who got me interested in visual sociology. We started a collective called Haymarket RIOT that made Social Theory proto-meme gifs in 1990-94 which Baudrillard loved, by the way. Later, we did these post-modern social theory-based industrial rock videos that were all 3D-animated. And I send these to Jacques Servin and Igor Vamos, when they were about to found RTMark. They did a cross-country tour across the US as Igor moved to Troy, NY, and they came to meet me in Ohio. They told me what they wanted to do, and I said: “Wow, you’re weird!” So we started RTMark, and the rest is history.

RTMark then turned into the Yes Men. I am not so central any more, but I still do all the animations for the movies and interventions. I think they became so noted that it is hard for them to do direct actions any more. Their actions became sort of theatre rather than activism. I think that’s why there’s much more emphasis on things like The Yes Lab and The Action Switchboard, so they can empower other people. The “Action Switch Board”, by the way, reminds me a lot of a much more refined version of RT Mark’s “Mutual Fund”, but much more robust.

TB: RT Mark, The Yes Men, Second Front – it seems like you prefer to operate in groups rather than developing your own personal Oeuvre.

PL: Not really, but certainly that is what is more visible to the public. Because I live in this world of mediation, it’s almost as if these groups have been my social groups. And I have always felt that in regards to getting traction in the cultural milieu, there has been strength in numbers. In groups, there are more people to jump on the soap box.

However, since the time when we founded Second Front, I’ve been very vocal in keeping the group into an almost ego-less form, patially from my experience with collectives, partially by the Zen/FLUXUS influence Bibbe Hansen brought to the group. I wanted a way to keep our group as logistically “flat” as possible. Which is ironic, because now Bibbe Hansen is one of our members, who has this huge legacy. Right now we are doing performances of Virtual Fluxus. We are also exploring Al Hansen´s (and other historical FLUXUS artists) work in Second Life.

TB: Are you “re-enacting” them, which is a trend in the art world right now?

PL: I would say “re-mediate”. What we are actually doing is performing un-produced texts by Al, pieces that could have never been done in real life. So we are not re-staging, we are creating works that have been unrealized. That is pretty exciting. One piece we have been doing is “Car Bibbe II”, a successor to his performance “Car Symphony” from 1968 that was never realized because of liability issues. He wanted to explode some Cadillacs.

TB: Why are you using Second Life? There has been a lot of criticism because this system leaves little liberty to the users…

PL: It is actually very fluid. It has a huge amount of possibility. Yet, we are currently investigating “Open Sim”, the open source alternative to Second Live. Any of the money that we are earning with the videos I have editioned at DAM will go to buy a permanent server and a static IP. I don’t want to go to another server farm. I want a modem in my living room with our world on my computer. It will be cheaper, and then we do not have to deal with Linden Labs’ oppressive policies any more.

TB: The attractive thing about Second Life was that at one point there was a ready audience, because it was so popular. But I do not think that this is the case any more…

PL: The important thing is that we used to do it as a function of community, and now we are using it as a representational tool. So the main results now are prints and videos. We want people to hear the tree fall, and this the way we get people to hear the tree fall in the woods: We take videos of it. The community has changed so much, it isn’t as important to us as artists any more.

TB: Second Life seems like Atlantis these days – a sunken, forgotten continent…

PL: It is kind of a necropolis for old technocrats. It is actually a very cyber-punk-thing. It is “Snowcrash”, 15 years later. But I am very interested in using Jurassic technologies and doing Media Archaeology. I also work a lot with pixelization, because at this point we don´t have to have it any more; it’s a choice. I did these pixilated nudes, that are barely recognizable as figures any more. You know, every artist needs to have a phase, where he is doing nudes, you know? (laughs) So I wanted to make them materially manifest a couple of years ago by laser cutting them into wood, expressing their materiality as surely as flesh does.

For the past ten years I have been doing media archaeological research into reviving Slow Scan Television as an art form. It is a video art form from the early days of Telecommunications Art. It is very low res, it only has four grey scales and a resolution of 120×120 pixels. It is a pretty specific and anachronistic art form. I am working with Hank Bull and Western Front right now to decode the audio track of the Slow Scan “Wiencouver” interventions of the 1980’s. I think I am one of the few members of my generation that knows how to run this equipment and how to repair these things. Many of my colleagues, who talk about dirty media and low tech, are still relying on the web… Well, they can have the Web. I am going back to networked art before the web. I am going back to the telephone network, but I use Skype now!