“[A] hundred reasons present themselves, each drowning the voice of the others.” (Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations: supra note 11 § 478).

For Part 1 click HERE.

For Part 2 click HERE.

Voice and unintelligibility play a greater, complex role in reasoning than the Left or Right accelerationists are prepared to admit, or fail to see. Establishing ones political voice is far broader and extensive than any of these thinkers take it to be, and is not simply the by-product of a phenomenological given unable to envisage any political alternative. Voice has to take priority here, for how else does one actually communicate? By this, we don’t have to take Voice to be the literal act of saying something out loud, or examining the behaviour for doing so. It can interpreted both as a metaphor and means encompassing every political act to which it can be applied; having a voice, or an opinion, hearing the public representation of someone, or of a community, wanting to being heard, letting someone have a say in the matter, etc. Above all it takes on the force of voicing ones own condition.

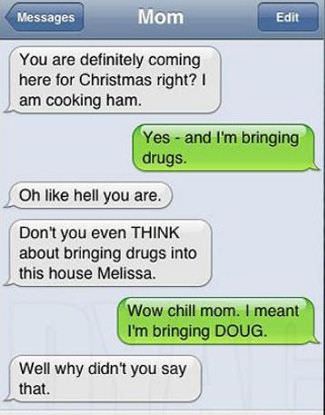

Might every form of modern communication then, be it a WhatsApp message, a bored glance at a meeting, cynical internet comments to nondescript mumbling, be one of ordinarily voicing our own condition? Perhaps even more so when it is mediated by an infrastructure (sometimes especially so). Both Voice and infrastructure are components of communicating indirectly, as most language games tend to do, whether face to face, face to mirror or interface.

The problem with philosophy is that the ordinary gets blamed, largely as the historical list of philosophy’s complaints almost always aim for the ordinary first as if its triviality is, by itself, not to be trusted with political or rational action. Indeed the very task of calling the ordinary to our attention, takes into account that we have lost interest in it. Perhaps it was already assumed that the market silently reduces the depth of ordinary communication and circumstance to capitalist knowledge anyway. Or maybe since ordinary life is increasingly and consistently mediated through online platforms, technology has overtaken its significance.

Yet what Ordinaryism seeks to uncover is that Voice does not constrain freedom because of its vulnerability: it is only because of vulnerability that voice expresses the freedom to reason in the first place. This is the split that severs both the sovereign rationality of Accelerationism (and Sellars), and the non-sovereign self of Ordinaryism (and Cavell). Indeed, this appears to be Cavell’s political lesson: it seems rational to want build a platform for others to air their democratic voice and decry any ineffective basis in favour something more determinate, more grounded, more inhuman. Yet freedom and justice only begins if a community is capable of ‘finding’ their own voice in the face of injustice. Likewise freedom is constrained if other voices repudiate the voice of others. There is no cognitive purchase for this, and no pre-built, implicit, or explicit ground for determining intelligibility either. So we have to ask, how else can the inhuman make itself intelligible unless it gives voice to its own condition? (As an aside, what else is philosophy but a set of specific and singular voices crying out for recognition in their appeal? A voice that may be acknowledged, yet equally repudiated? Just as the sound and look of Voice matter in reasoning, [how it persuades, how it strikes you] so too does the sound and look matter to philosophising arguments and deductions.)

The easiest way to round these political concerns up is to show how the very need to bypass the vulnerability of Voice, the need to provide an ‘answer’ or ‘solution’ to that vulnerability, is the same philosophical question that concerns solving skepticism. This is the heart of Cavell’s philosophy.

Following Naomi Scheman, the heart of transcendental inhumanism to which the epistemic accelerationists follow aims to draw attention to what underlies the possibility of our ordinary lives. But in Ordinaryism, the Cavellian rejoinder must insist that “the ordinariness of our lives cannot be taken for granted; skepticism looms as the modus tollens of the transcendentalist’s modus ponens.” (Scheman, “A Storied World”, In Stanley Cavell and Literary Studies, 2011 p.99). Whereas Accelerationism posits a renewed set of tools to re-determine intelligibility in an era of supposed ‘full automation’, Ordinaryism speaks to these same conditions but where intelligibility routinely breaks down, is endlessly brittle, always delicate, sometimes connects, but is never ensured or determined by philosophical explanation alone. What might it mean to understand the fragmented world of machines as a uniquely literary responsibility?

In other words, a future world of increased automation needs a romantic alternative. And it is sorely needed, because in this future order where automation is assumed to outpace human knowledge, or supersede it in any case (amplifying existing industries, or creating new ones) Ordinaryism speaks of new moments of doubt which constitute the skeptical fragments of ordinary life with machines. Perhaps also of machines. It might take on a specific personal form of questioning and living with what these new forms takes on; “what does this foreign mapping of data really know about me”, “what does it know about all of us?”, “Am I just being used here?”, “How can I know whether anyone is spying on me?”, “why are they ignoring me?”, “what on earth does that Tweet mean?”, “what’s happening?”, “what am I supposed to think about this”, “Why would I care about you’re doing?”, “I need to know what they’re doing.”

There are innumerable ordinary circumstances where a life with machines begins to make sense, but also starts to break down in all the same places: how might one suggest that a machine “knows” what it’s doing, or that “it knows” what to do? Where does the scalability of automated systems start to break down, and what sort of skepticism does it engender when it does? What happens when software bugs, and unpredictable acts of mis-texting chagrin habitual pattern? How might such finite points of knowledge exist, so as to understand and inhabit systemic doubt? What are the singular and specific means for how such systems are built, conceived or decided? And most of all, how might we even begin to characterise and acknowledge the voices which emerge within these systems? You might say that Ordinaryism wishes to extract acknowledgement out of the knowledge economy.

What is required then, is both a Cavellian critique of epistemic accelerationism (what potential political dangers might arise if Voice is repudiated) and why its solutions to solve skepticism through collective reasoning and self-mastery are no different from skepticism itself. But to do that, one also has to take account of how Cavell brings an alternate approach to imagining how normative rules are implicit in practice. This is not an act of opposition, more of a therapy, which might be needed, especially as politics is involved.

Now, despite the fact that Cavell’s philosophical questions work (almost) exclusively in the Wittgensteinian domain of articulating and expressing normative concepts which regulate speech and pragmatic action (beginning from his first essays Must We Mean What We Say? and his later magnum opus, The Claim of Reason) these texts don’t appear to be required reading in accelerationist and neo-rationalist circles.

Take the newly released art journal Glass Bead, whose aim is to suggest that any “…claim concerning the efficacy of art – its capacity, beyond either it’s representational function or its affectivity, to make changes in the way we think of the world and act on it – first demands a renewed understanding of reason itself.” If such a change in thinking is motivated by a renewed post-analytic approach to reason in a world of complexity (and an additional capacity for aesthetic efficacy), the continued omission of Cavell’s work into reason and aesthetics, is notable by its complete and utter absence. It’s enough to warrant the claim that certain imaginings of reason – in this case the abstract inferential game of giving and asking for reasons – are to be favoured over other types (usually with a secondary, pragmatist demand that science is the only authentic means for understanding the significance of the everyday).

In fact there’s a good reason for that omission: because Cavell discovered that he wasn’t able to ignore the threat of skepticism entirely, and instead discover it to be a truth of human rationality (is there anything more paradoxical than discovering ‘a truth’ in skepticism?). He instead sought to articulate how such concepts were not inherent features of inhuman ascension by means of inferential connection, but fragmented conditions of differentiated identity. In the eyes of the epistemic accelerationist, it’s as if there isn’t any possible option in-between some half-baked, progressive ramified global plan to expand the knowledge of human rationality, and a regressive fawning over the immediacy of sensual intuition. Fortunately, Cavell’s ‘projective’ approach to rationality questions this corrosive forced choice.

Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations sets up the key differences here. Instead of using Wittgenstein’s text as an introductory tool to show how the public expression of saying something can be explained and correctly applied (as Robert Brandom pedantically attempts), Cavell paid attention to Wittgenstein’s voice, as it invokes a specific and personal literary response to what happens when we are in search of such explanatory grounds (and how they always disappoint us). Perhaps more pertinently, Wittgenstein alluded towards an effort ‘to investigate the cost of our continuous temptation to knowledge.‘ (Cavell, The Claim of Reason, p. 241) Compare this to the current neo-rational appeal which has little to no awareness that the pursuit of certain knowledge (and the unacknowledged consequences for when it will go astray) might itself be inherently unproblematic. Because reason presumably.

It’s no accident therefore that Philosophical Investigations has become one of the oddest literary feats in Western philosophy, insofar that it presents itself as a personal account, rather than a systematic one. Cavell was not only the first to prise out a Kantian insight from Wittgenstein’s text, but also to ask the simple question of why does he write like this? It’s as if every single word, every ordinary word, now takes on the full power and insight as any theoretical term of jargon: as if a theoretical vocabulary isn’t wanted or needed. Why does Wittgenstein provide provocative literary fragments to elucidate his philosophical struggles? (the infamous ‘mental cramps’) Why does he raise literary devices to flag up disappointing conclusions: where a rose possesses teeth, beetles languish in boxes, and lions speak in packs of darkness? It’s an insight which lies in acknowledging that Wittgenstein’s unique literary voice is inseparable from his philosophical ambitions. It is not that he offers an anti-skeptical account to fully fix and explain what it means to say something: nor does he posit an implicit mastering of normative concepts, whereupon said possibilities are subject to further explanation (the conditions under which cognition or experience become possible).

It’s as if the theoretical problem doesn’t come with fully understanding norms implicit in practice, but the very situation in which using words like “rules”, “freedom”, “determine”, “correct” and so on, do not have the desired theoretical effect (in the accelerationist case, freedom). These are very nice words after all, but the neo-pragmatist theory is found wanting in their full expression, sufficient to the limits given when they are spoken not as a licensed inference, but as a creative effect. Cavell’s take on language thus, is that there is always something more to words than the current practice in which they are put to use.

The appeal to Wittgenstein’s literary conditions is what motivates Cavell to suppose that his theory of norms in practice isn’t something to which words are used to line up a certain conclusion, rather, the specfic and singular non-formal ordering of ordinary words in themselves provide a certain crispness and perspicuity, as well as difficulty and confusion. As Paul Grimstad suggests:

“Cavell wonders what one would have to do to words to get out of them a certain kind of clarity; to ground their meaning in an order. A kind of literary tact—the soundof these words in this order—would then serve as the condition under which we are entitled to mean in our own, and find meaning in another’s, words. The sort of perspicacity striven for here is not a matter of lining up reasons (it would not be “formal” in the way that a proof is formal), but of an attunement to arrangements of words in specific contexts.”

As Sandra Laugier chooses to describe it, Cavell’s posing of the Ordinary Language Philosopher’s question – “What we mean when we say” arises from “what allows Austin and [the later] Wittgenstein to say what they say about what we say?” For Cavell jointly discovered a radical absence of foundation to the claims of ‘what we say’, and further still, that this absence wasn’t the mark of any lack in logical rigour or of rational certainty in the normative procedures that regulate such claims. (Laugier, Why we need Ordinary Language Philosophy – p.81)

If agreement in normative rules becomes the presupposition of mutual intelligibility, then any individual is also committed to certain consequences whereupon certain rules might fail to be intelligible. Therein lies a simple difference: the espousal of following a universally applicable rule (as Brassier holds) and everyone else wondering whether that same rule has been correctly followed.

To mean exactly what we say, or to mean anything in fact, might be contingently mismatched to the specificity of what we say and project in any given context, hence one must bare the normative challenge that *what* we mean may differ from what we say.

The ordinary is saturated with these innumerable variations of mismatch through specific and singular situations, to which our attunement is threatened: when a co-worker fails to turn up to a meeting because they misunderstood someone’s directions or when a poor sap fails to get the joke he or she is the brunt of, or when a close friend misunderstands a name in a crowded bar. These moments are not insignificant wispy moments of human limitation swallowed up in a broad history of ascension, but become the necessary exhaust that emanates from a social agreement in which the bottom of our shared communal attunement falls away. With a language, I speak, but only insofar as we are already attuned in the projections we make.

As Cavell put it in this famously long (but necessarily long) passage;

We learn and teach words in certain contexts, and then we are expected, and expect others, to be able to project them into further contexts. Nothing ensures that this projection will take place (in particular not the grasping of universals nor the grasping of books of rules), just as nothing ensures that we make, and understand, the same projections. That on the whole we do is a matter of our sharing routes of interest and feeling, modes of response, sense of humour, and of significance and of fulfilment, of what is outrageous, of what is similar to what else, what a rebuke, what forgiveness, of what an utterance is an assertion, what an appeal, when an explanation – all the whirl of activity that Wittgenstein calls “forms of life”. Human speech and activity, sanity and community, rest upon nothing more, but nothing less, than this. It is a vision as simple as it is difficult, and as difficult as it is (and because it is) terrifying. (Cavell, Must We Mean What We Say? p.52)

If the reader might allow a Zizekian-style joke here (apologies in advance), it might elucidate Cavell’s insight further than the lofty quote above: “Two guys are having an heated exchange in a bar. One goads to the other, “what would you do if I called you an arsehole?”, to which the other replies “I’d punch you without hesitation.” The first guy thinks on his feet: “well, alright, what if I thought you were an arsehole? Would you hit me then?” The second guy reflects on his reply, “well, probably not” he says, “how would I know what you’re thinking?” “That settles it then,” says the first guy, “I think you’re an arsehole.”

Although the mismatch is played to (a rather ludicrous) comical effect, it offers a way into Cavell’s strange appreciation of skepticism’s lived effect. We intuitively know these ordinary situations, ordinary utterances and yet such acts are not instances of reason ascending its limits through knowledge, but are necessary and specific instances where reason’s endless depth and vulnerability enacts itself within such limits. The intelligble process by which the concept of “I think you’re an arsehole” arises, does little only to serve how brittle the semblances between saying and thinking portray. This for Cavell produces an anxiety; and it “… lies not just in the fact that my understanding has limits, but that I must draw on them, on apparently no more ground than my own.” (Claim of Reason, p. 115).

But it also presents a shift from the commonness of ordinary language to the question of a community where that commonness resides. And for Cavell if it is the case that there’s no firmer foundation than shared practices of common speech and community, there cannot be a shared conceptual framework, so as to collectively determine an objective intelligible method of treating and avoiding skeptical claims. Thus, any instability between what we find intelligible (what we cognitively understand or grasp) and how it is expressed in what we say, is also indicative of the social and cultural conditions that sustain such vulnerabilities. This is why for Cavell, the social conditions of a language game are fundamentally aesthetic in character, because we are both attuned to the conditions of a game and the experimental moments in which one tries out new and progressive literary arrangements that push against the game’s limits.

Which is why the history of the inhuman is constitutive of skepticism as barbed wire is constitutive of blood stained fences. And in conclusion, we’ll begin a preliminary move towards a bona fide Ordinaryist alternative to epistemic accelerationism (to be fleshed out in the final part). Key to this alternative is to understand that reasoning is not explainable by rule-governed inhuman rationality, but has a hand in the general projection of words, criteria and concepts in ordinary language (and moreover how inhuman Exit threatens this reasoning). Just because political action within reasoning can often fail to be intelligible, does not render it subject to inhuman ascension.

Nonetheless, Accelerationism operates as if there’s no other type of future worth wagering on, nor any method other than the force of reason suitable enough to supply the tools required. The morality put forward hence is that the more we are able to harness our knowledge of our social and technical world, the better we will be able to effectively rule ourselves and the greater chance of a strategy to overcome capitalism. The chief rejoinders that usually face criticisms of renewing the Enlightenment, consist in labelling detractors as complicit with skepticism, misunderstanding skepticism, languishing in sophism, abandoning reason for irrationality, justification for complicity, and trading off modern knowledge for theological assumption. Brassier recently referred to this skeptical questioning as the “unassailable doxa” of the humanities, constitutive of an influential strand of 20th Century European philosophy (from Nietzsche onwards), where the desire to know is “identified with the desire to subjugate”. Brassier goes on;

This is skepticism’s perennial appeal: by encouraging us to give up the desire to know, it promises to unburden us of the labour of justification required to satisfy this philosophical desire. Thus it is not certainty that skepticism invites us to abandon, but the philosophical demand to justify our certainties.

What Brassier takes for granted however, is that refusing to adhere to the force of reason and the ongoing project of attaining knowledge does not instantly amount to embracing skepticism, or that such knowledge will always be inadequate (and a violent act). What is at stake is not *simply* an inadequacy of knowledge as a cognitive resource. To view it as this, is what Cavell associates as skepticism, even if the desire is to then overcome it, or, in some way pushing skepticism to a deeper conclusion. The issue is not sophism, but skepticism.

Cavell’s romantic inclinations towards ordinary language philosophy offers a way out of this forced choice: skepticism simply cannot be refuted in favour of a renewed inhuman anti-skepticism. Entertaining skeptical doubt isn’t something which philosophers are especially adept at, treating it as an intellectual error to refute or ward off afterwards. Skepticism inhabits itself as an everyday, ordinary occurrence, equally puzzling and troubling, eternally unsatisfied and yet utterly enticing. It is a strange, yet equally relentless human drive to repress and reject the very attuned conditions that sustain intelligibility: conditions which also contain the ability to attune to one another’s projections.

In consideration of the fact that Accelerationism wants to conceive our conditioned intelligibility as a product of rule-governed knowledge this poses problems worthy of the best tragedies the humanities have to offer. Here’s Cavell’s take on the matter (my emphasis):

I do not […] confine the term [“skepticism”] to philosophers who wind up denying that we can ever know; I apply it to any view which takes the existence of the world to be a problem of knowledge […]. I hope it will not seem perverse that I lump views in such a way, taking the very raising of the question of knowledge in a certain form, or spirit, to constitute skepticism, regardless of whether a philosophy takes itself to have answered the question affirmatively or negatively. (Cavell, The Claim of Reason, p.46).

Brassier would probably lambast this certain condition as a conformist view of ‘I should or ought to live my skepticism’, such that it hides an implicit refusal to investigate or question these forms (leading to various, inexorable ‘end of’ philosophies). But in doing so he takes on, at least in Cavell’s eyes, the compulsive epistemic assurances that skepticism compels. By implication Brassier’s endorsement of an anti-skepticism hides the fragility and depth of normative claims, and that claims are always voiced and projected. The problem with espousing rules for generating normative freedom is that a rule is neither an explanation nor a foundation – it is simply there (note that in saying this Cavell does not deny any rigour, moral or political commitments to normative rules). What Brassier and Accelerationism share is to answer a source of disquiet; that the validity of our normative claims seem to be based on nothing deeper than ourselves, or how words are put. And this attempt to reject Cavell’s insight, to erase skepticism once and for all, backfires only by reinforcing it.

Cavell’s treatment of skepticism is that it must be reconfigured away from an entrenched view of epistemological justification as a product of certainty: or that the existence of other minds, objects, procedures, processes and worlds can be reduced to problems of (and for) knowledge. The head on effort to defeat skepticism allows us to think we have explanations when in fact we lack them. Or put better, the idea that we can theorise a clean break from skepticism is itself a form of skepticism. The point is that we clearly can approach communities, other minds, systems and communities which often appear incomprehensible, unintelligible; but such appearances are features of vulnerability, and vulnerable grounds which we depend on nonetheless. Yet change only occurs not because we’re certain about the knowledge we possess, but in response to others whose involvement happens to be beyond my intellectual attempt to know them with certainty. There is nothing more uncertain than a response to alterity.

Politics operates exactly in this way, coming to terms with ones immediate response to injustice, not in “knowing” it or offering an explanation, but by acknowledging it. The “folk” vulnerabilities that Srnicek and Williams find ineffective are constitutive of intelligible injustices that we must acknowledge in order to engage at all. Nothing guarantees this. This is the central point: reasoning with the inhuman, requires a human appeal to acknowledge another – or put differently, making the inhuman intelligible requires that we acknowledge the voice of the inhuman (and equally that this same voice can reject our appeals). After all, what use is a politics based on the epistemic assurances of knowledge, if such knowledge can be regularly doubted?

What Brassier doesn’t acknowledge is that both his position and the skepticism he attacks, are guilty of the same premise: the longing for a genuine inhuman knowledge, without acknowledgment. This appeals to something greater than the everyday which gives voice to such justifications. Nihilism might be fun, but at some point its political actions soon becomes silent to its own screams, as it spins into a void of its own making. The ordinary prevails.

Cavell suggests that this philosophical impetus towards the inhuman is inherent to the skeptical habits of philosophical drive, for there is:

…inherent to philosophy a certain drive to the inhuman, to a certain inhuman idea of intellectuality, or of completion, or of the systematic; and that exactly because it is a drive to the inhuman, it is somehow itself the most inescapably human of motivations. (Conant, “An Interview with Stanley Cavell,” in Fleming & Payne, eds., The Sense of Stanley Cavell, 1989)

Unlike most ordinary language philosophers, Cavell has always been clear that the appeal to ordinary language is not the same as refuting skepticism (as some disciples of Wittgenstein might have it). Nothing is more skeptical, more aversive to the everyday that the “human wish to deny the condition of human existence” and that “as long as the denial is essential to what we think of the human, skepticism cannot, or must not, be denied.” (Cavell, In Quest of the Ordinary, 1988, p. 5) In fact, most of Accelerationism’s Promethean attempts in fully maximising the human drive to transcend itself, were preempted by Cavell: as the skeptics’s treatment of the world (and others) is endless, completely prone to acceleration. One might say, acceleration is built into skepticism when the human mind convinces itself that the world is divorced and devoid of meaning – it encounters nothing but the meaningless of itself. It becomes a tragic temptation which the human creature carries out, an internal argument that it can’t quite relinquish. Or as Cavellian scholar, Stephen Mulhall puts it simply. “the denial of fintiude is finitude’s deepest impulse.” (Mulhall, The Self and its Shadows, 2013, p.48)

Accelerationism becomes a tragedy. A tragedy of never quite knowing what knowledge is enough, or when (it’s tragic enough that in theorising the emancipatory potentials of technology, it hasn’t appeared to go any further than incessantly arguing about it with others on blogs and Facebook threads – this author included).

However this shouldn’t be too much of a surprise when you have a political movement which shares an enthusiasm for building AI systems that are (quoting Mark Zuckerberg early last year); “better than humans at our primary senses: vision, listening”. When Facebook’s CEO thinks it’s unproblematic to invent a future sending unmediated telepathic thoughts to each other using technology (and your response to this is that it’s merely constrained by neo-liberal market forces) skepticism has reached a new apex. Ordinaryism makes no conservative attempt to preserve some fabled image of humanism located outside of technology, nor provide any Heideggerian technological lament, but instead reflect on what this tragic apex of skepticism will mean for us, what it says about our condition, and how the vulnerabilities of Voice make themselves known nonetheless. More than anything, how will this new apex of skepticism change the ordinary?

No doubt the Left-Accelerationist’s hearts are in the right places: but nonetheless, the dangers become obvious. If the solution to overcoming capitalism takes on the same inhuman skeptical impulses for epistemological certainty that constitute it, what exactly stops the Left-accelerationist’s proposals from being used for reactionary purposes? What sort of decisions must it undertake to control the ordinary, and to that effect, the ordinary voices of others who might doubt their knowledge?

This is why Cavell takes skepticism to not only be the denial of reason having any epistemic certainty, but the entire explanatory quest for epistemic certainty tout court. Both are latent philosophical expressions of what he calls ‘the skeptical impulse’ and both inhabit the very denial of this impulse whilst also becoming its mode of expression. The problem with attaining knowledge of the world, isn’t knowledge, but its theoretical desire for knowledge as certainty. Brassier would have you believe that any deviation from the emancipating Platonic discipline of ascending human finitude – the desire to know – risks disengaging reason from mastering the world. Whereas in the ordinary, reasoning becomes essential because it can never master the world, only inhabit its projections. Under ordinary circumstances reason can only appeal, in numerous and multifaceted paths, experimenting with different kinds and types of intelligibility taken from a shared linguistic attunement. It’s ability to appeal is never achieved as ascendancy, but by the endless vulnerabilities of ordinary language. Intelligibility is a continual, vulnerable task, who failures become the engines for relentless re-attunement with others and the world. Exactly ‘what’ is said, ‘how’ something is said, can make all the difference: and in politics, especially so.

Reason shouldn’t and doesn’t progress by ascending itself, it progresses by tiptoe. It re-engages with the world critically, and can only appeal to others in doing the same. The moral desire of Ordinaryism is exactly this: not to exit the world, but to be in it, to be present to it, and give it and others a voice which might make that desire intelligible, so as to modify the present situation. This is why we always have to acknowledge what we say when. To show how the world attracts itself to us and how it does so in each singular and specific case. When the future comes, it’ll emerge (as it always does) in some sort of vulnerable ordinary way.

Refuting skepticism, is in itself a performative expression that simply repeats skepticism; it denies the very truth and reality of living a skeptical existence, that knowledge as certainty is an ongoing disappointment. Quoting Sami Pihlstrom, “…there is no skeptical failure here requiring a “solution”; the attempt to offer a solution is as misguided as the skeptic who asks for it.” (Pihlstrom , Pragmatic Moral Realism: A Transcendental Debate, 2005, p. 76). Once the fight to close down skepticism is enacted, accelerationism encourages its major conditions – that the problem of knowledge about the world, of other minds, of systems, global insecurities, economics becomes a problem of certainty. And yet, at the same time, Accelerationism neglects skepticism’s fundamental insight that there are specific and important problems about the role of knowledge which might have to be acknowledged. It neglects the truth of skepticism. We live our skepticism. Daily.

The surprising conclusion that arises from this quagmire, is that the skeptic is in fact right – and yet, simultaneously, skepticism is fundamentally wrong. Well, not exactly wrong: just a refusal to accept that the human creature is also a finite creature, or as Cavell put it, skepticism manifests itself as “…the interpretation of metaphysical finitude as intellectual lack.” (Cavell, In Quest of the Ordinary, 1988, p.51). As Áine Mahon puts it, “Cavell’s strategy is paradoxical: he strips s[k]eptical doubt of its power precisely by showing that it is right…. the skeptic’s doubt results from a *misunderstanding* of the truth she discovers.” (Mahon, The Ironist and the Romantic, 2014, p. 23). He takes skepticism to not only be a standing menace that denies an ordinary intimacy with the world, but also as a necessity to acknowledge ones finitude. For Ordinaryism too, also challenges political immediacy that Srnicek and Williams lament, but does so on the grounds of renewed intimacy with the ordinary. The issue is not binary: either of knowing or not-knowing, but of acknowledging (and regrettably, failing to acknowledge). The ordinary is grounded, not on knowledge (implicit or explicit), explanation, proof, logic, nor material, it’s grounded on nothing more and nothing less, than the acknowledgement of the world.

For the skeptic is in fact right, because everyday knowledge is vulnerable: the existence of the external world, other minds, and God falls outside the scope of what language can prove. Wittgenstein’s criteria can tell us what things are, but not whether things actually exist or not. This, however, does not mean that Cavell doubts the existence of things, and especially not the existence of other minds. It means that ultimately, such modes of existence must be accepted and received: moreover they have to be recovered and acknowledged.

Bracketing the abstraction here, one can immediately look to timely instances of ordinary life, in which Cavell’s ideas on skepticism seem at first distant, and then suddenly intuitive. Consider the natural, anxious reality of parenting for example (interwoven within a broad tapestry of anxiousness). I speak of first time parenting predominantly here: for doesn’t the very task of living with skepticism, responsibility and finitude, become central to the activities of childrearing and all attempts to find clear answers to the contingency, uncontrollability and unpredictability it engenders? It’s not the normative fault of parents for wanting to find something deeper, clearer and surer in order to solve the anxiousness that childrearing brings: but yet equally nothing solves it either. But there isn’t any normative basis, or universal demand for suggesting that a parent ‘ought’ to know, or ought to justify an explanation on the act of learning how to parent effectively. One simply does so, but in doing so, skepticism is not refuted, or made to temporarily vanish by competent practices alone: it is lived. More importantly, it is lived with others who also live it.

This is what Brassier’s anti-skeptical demands of accelerationism gets wrong: it makes the wrong normative demands on what ‘ought’ or ‘must’ be attained for the conditions of intelligibility to function. He makes little contention in suggesting that skepticism might also be understood as a failure to accept human finitude (Cavell, In Quest of the Ordinary, p.327), than it is a failure to justify one’s certainty in knowing. Nothing is more skeptical than the precarious efforts to reconstruct human language and communication on a more ‘rational’ or more ‘justified’ foundation, one which would avoid any need for a less tidy, ambiguous, disruptive – and above all – vulnerable aspect of ordinary expression.

It completely bypasses any option that having access to other minds and the things of this world can operate on anything other than certain knowledge. No doubt we have knowledge, and it runs deep, but it also has clear limits. As Cavell brilliantly words it; “the limitations of our knowledge are not failures of it.” (Cavell, The Claim of Reason: p. 241) Is there anything that undermines the accelerationist premise more than the ill-fated attempt to pit human knowledge against an inhuman idea of knowledge? Or if it appears that computation has no limits, neither should humans? Of course the issue here is staked in the idea that computational reason is a transcendental destiny of human knowledge, when in ordinary practice, it automates all the same vulnerabilities that chagrin us daily.

By implication any form of skeptical utterance or speech becomes unintelligible, meaningless, and thus not amenable to normative, rational ascension. By another, machines operate in a weird inhuman world of untapped knowledge, which humans are yet to match their conditions to. But this is not just an accurate reflection of ordinary speech, it’s not even an accurate reflection on how computers work as a specific and singular thing.

Epistemic Accelerationism falls into a skeptical trap – whilst all the while, masquerading itself in as a new heroic anti-skeptical saviour of reason: when knowledge becomes disappointing or fails, it flips into a binary skeptical register of an either/or: either we have knowledge or not at all. But whilst the skeptic realises that true knowledge cannot be attained, they opt for the total withdrawal from any access to the world whatsoever. Anti-skepticism takes on the basic contours of this view, and opts to simply refute skepticism wholesale, reducing the world to laws of thought.

The result of unexpectedly reinforcing skepticism is not (as the skeptic and anti-skeptic thinks) that the world becomes unknowable, or we lose the capacity to claim anything, but that we ourselves become unintentionally mute and unknowable to others. In political terms, this has much to do with how the sovereign usurps the voice of its subjects, rejecting the acknowledgement and attunements of a shared world, evading the responsibility of others to speak politically for themselves by losing the ability to express a political voice. It omits the possibility of an alternative exemplar voicing injustice on behalf of members within a community.

A claim’s meaning is a function, only in its specific use in a specific context but a specific speaker. Epistemic Accelerationism, in speaking to a universal inhuman knowledge evades any sort of position that attempts to speaks on behalf of others, or allowing others to speak, by speaking on behalf of no-one. Except probably machines. With speaking in general, claims of reason are more about saying something as a literary responsibility for what we say (and the specific literary insecurities for how it will be treated, communicated) than it is playing a game of giving and asking for reasons (in what sense is there even a ‘we’ in a game of giving and asking for reasons?). Making claims intelligible means paying attention to such ordinary literary conditions.

For Cavell, acknowledgment operates as a wider form of knowledge which cannot be a function of certainty. Acknowledgement is a delicate concept, specifically created to oppose the idea that intellectualist knowledge attains entirely new information about the world. Instead we acknowledge, that is, re-conceptualise things that have always been before us: what (or that) we already know. What we ordinarily know, as if we approached it for the first time, can suddenly become vulnerable. Therein perhaps provides a putatively solid difference for what aesthetic claims do, separate to scientific ones; science provides new knowledge about the world, aesthetics re-conceptualises what we already know. Influenced by Cavell (and equally Arendt and Butler), Rosine Kelz, encourages this insight, stating that;

…it is precisely when we come into contact with others that the finitude of knowledge and understanding most sharply comes into focus. [Cavell] maintains that communication can not only potentially fail, but that indeed the failure to grasp and communicate ‘fully’ is a defining feature of the human condition, [and]… is mired by our inability to control not only what the other understands or acknowledges, but also by an unwanted ‘excess’ where what we say always reveals more than what we intend. (Rosine Kelz, The Non-Sovereign Self, 2015, p.80).

In the face of political injustice, acknowledgement might take on the marginalisation of race, gender, migration, class. We can only know these political injustices, not through certainty, but by paying attention to particular situations we already acknowledge and respond to (in the same way the ordinary language philosopher responds to how the literary responsibility of ordinary language is specifically voiced and projected). As Cavell puts it in this famous passage:

How do we learn that what we need is not more knowledge but the willingness to forgo knowing? For this sounds to us as though we are being asked to abandon reason for irrationality… or to trade knowledge for superstition… This is why we think skepticism must mean that we cannot know the world exists, and hence that perhaps there isn’t one… Whereas what skepticism suggests is that since we cannot know the world exists, its presentness to us cannot be a function of knowing. The world is to be accepted as the presentness of other minds is not to be known, but acknowledged. (Cavell, Must We Mean what We Say?, p. 324)

‘Justification’, ‘political change’ and ‘practice’ in this regard, must also be reconfigured by the same method of acknowledgement and presentness. Because skepticism and anti-skepticism start from the same desire, they provide greater explanatory positions than they actually can. Anti-Skepticism’s “self-portrait […] tends to [..] scientize itself, claiming, for example greater precision or accuracy, or intellectual scrupulousness than, for practical purposes, we are forced to practice in our ordinary lives.” (Cavell, In Quest of the Ordinary, 1988, p. 59). Or is accelerationism still pretending that philosophers, futurists and scientists have special access to knowledge that bearers of ordinary language fail to possess?

Cavell’s point is that there is knowledge in acknowledgment, but one that is ethically responsive and politically culpable in projecting political change into the world. This is politically significant insofar as acknowledging someone or something isn’t a practice of seeing what we had previously missed, or not known, but takes on the role of an admission: a confessional quality to it. After all in confessing, you don’t offer an explanation for your reasons and claims, you can’t be certain about them: you can only persuade, or at best describe how it is with you. But there is a wider, ethical and political issue that splits apart the task of certainty in knowledge and the vulnerability faced (and facing) us in acknowledgment – and it has a polarising effect when reason is limiting. As Cavell puts it;

A ‘failure to know’ might just mean a piece of ignorance, an absence of something, a blank. A ‘failure to acknowledge’ is the presence of something, a confusion, an indifference, a callousness, an exhaustion, a coldness. (Cavell, Must We Mean what We Say?, p. 264)

This is at the core of Ordinaryism’s return to a progressive romanticism. Having the philosophical demand to justify our reasons is perfectly respectable: but in attempting to force this task because the demands of thought have failed to know the world, is something else entirely.

It will require a Romantic return for philosophy to become literature, not in the literal sense of imprisoning a subject in language, but the complete opposite, insofar as “literature” names the tension between the projection of words and their future applications. Nowhere is this more perspicuous than in the use of online platforms, and our increasing reliance on them for sharing communities. In this new sense, Ordinaryism – in its most romantic set of moods – sets itself an alternative task, which as Cavell puts it, “the task of bringing the world back as to life.” (In Quest of the Ordinary, p.52f) as if we became astonished with a quiet, naive disbelief that the world and ordinary communication existed at all, or took it to be obvious. But a more helpful way to look at it, is that Ordinaryism is open to modes of expression that require acknowledgement of something beyond the reach of conceptual assertion, both of human creatures that reason in a shared social practice and of the world. Regrettably these are possibilities which Accelerationism and the history of the Enlightenment rule out a priori.

The question that follows, one that for Cavell was too early to consider, is why our current technological situation has made us think otherwise? To what extent has the freedom to Exit become entirely obsessed with a certainty of knowledge that smart technologies supposedly provide? And why is Voice, (understood in these terms as ‘ineffective’ and indirect ‘human’ communication) now viewed with suspicion and redundancy? To provide an insight requires understanding how the eventual ordinary can arrive under the hood of explicit awareness: and how such Cavellian themes of projection, acknowledgment and attunement now play different, albeit, new defining roles in lives insatiably entangled with digital culture, infrastructure, automation and computation.

By any standard, our response to the future will be established by our changed attitude to reason and freedom. When faced with the onslaught of the Anthropocene, and diminishing opportunities to establish a progressive alternative of change, we might need to be clearer with how reasoning comes to emerge: is it through the self-determination of ascension or the persistent acknowledgement of its vulnerabilities?