Liz Filardi is a New York City-based performance artist who often works in public space. She was recently awarded a Turbulence Commission for a networked performance piece called I’m Not Stalking You; I’m Socializing, exploring the anxieties of social networking in three modules. “Status Grabber,” the first module, is a satirical online service that extends the status update phenomenon to participation over the telephone. “Black & White,” the second module, is a Facebook-like website, consisting of two interlinked profiles, that tells the story behind one of the original cases of criminal stalking in America. “Facetbook,” the final module, is a performance piece in which the artist compiles a series of archives of her live Facebook profile to illustrate the tension of online identity– between the façade of a profile and the more telling story of how the profile changes over time. The interview was conducted by Taina Bucher, PhD fellow in the Department of Media and Communication at the University of Oslo, Norway. Bucher and Filardi met in Greenwich Village, New York City in May, 2010.

Taina Bucher: How prominently do your friends feature in your work?

Liz Filardi: Well, my only “in” to a social network like Facebook is my own profile, my own network. I think I have about 900 friends. I could start over with a new profile, but I would still only be able to access people that I know or know of. So the people who participate in works based in existing networks, like “Facetbook,” are my friends, and in this context, that includes any Facebook “friend” who feels comfortable commenting or interacting with me. I suppose there is also a subset of “friends” who are made aware of my activity without necessarily caring or wanting to interact with me. In that respect, networked performance on Facebook is very much like performing in public space—I get ignored a lot.

But I would love to find a way to reach a completely different audience on a social network, ideally a subset of users who have stumbled upon my profile without really knowing me or maybe only knowing me from the context of the network because I’m a “friend” of someone who they have “friended.” I have been thinking about starting over on a network like Facebook with this goal in mind, just to see what is possible. It would also be fun to create a new profile controlled by a collective of artists who want to play and experiment.

Why not just make a group on Facebook?

Groups have limitations. Individuals have the most access and mobility on Facebook, because it is designed with the individual’s activity in mind. Groups are like, “I’m here, come over here,” while individuals can say, “I like this, I am doing this, you and I are friends,” which is obviously what drives the site. I am also more compelled by putting a face on a group and speaking from the first person, mixing individual voices and sensibilities and presenting that as one person. It feels a little more subversive. I am interested in playing with the expectations of “friends” on Facebook. For some reason, there is a lot of trust that everyone, that is every non-celebrity, is exactly who they say they are.

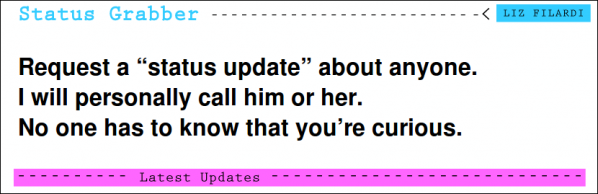

Can you tell us a little about your project “Status Grabber?”

“Status Grabber” was created as a satire on the obsession with status updates. I wanted to know how people would react to a telephone-based service that essentially mimicked the way people use Twitter. So I called people and told them that someone they knew had anonymously requested a status update, and that they should provide me with a brief statement that I could post to the internet. I set up a website where people could actually make those requests and hear the responses. But I also made cold calls to random people listed in the telephone book.

My interest in status updates lies in the disconnect between the author’s intention and the follower’s intention as they engaged in a fairly consistent relationship mediated by a service like Twitter. On Twitter, you can post one message immediately visible to your followers, and those people can discover something about you and experience the feeling of a connection without ever having to say a word or reciprocate. In fact, as you post your update, you often do so with a vague idea of audience, not necessarily of personal connection. So the relationship between a Twitter author and follower can feel smug, but it is artificial—it is a designed experience. Apparently, if popular social tools fill a vacuum of desire, as we often believe, people actually prefer this designed experience on some level. We tend to prioritize the feeling of a connection over the actual value of the connection. In making the calls for “Status Grabber,” I’m basically confronting people with this cultural value.

I visited the site and listened to the call records you posted. It seems that people don’t have a clue about the notion of status updates.

Yeah, the concept of a status update obviously doesn’t translate to the telephone. On the phone, there is much more opportunity to communicate beyond the 140 characters allowed in a Twitter status update, so that became a humorous limitation to the updates that people were encouraged to provide. As a totally believable service, Status Grabber suggests that people actually do not want to have a full conversation or hear a complete update on your status, but instead prefer the abridged version so they can get on with their lives. Of course, most of the call recipients seemed slightly disappointed or appalled for that reason, and in that way, it felt like a good prank phone call.

Call recipients that were willing to participate seemed to feel anxious about the pressure of submitting a status update verbally. They were on the spot to say something substantial or witty as if posting to their Twitter or Facebook account. Most of the updates reflect more spontaneity, less density than can be read in Twitter feeds. I often felt that I was invading their privacy to demand a status update by telephone.

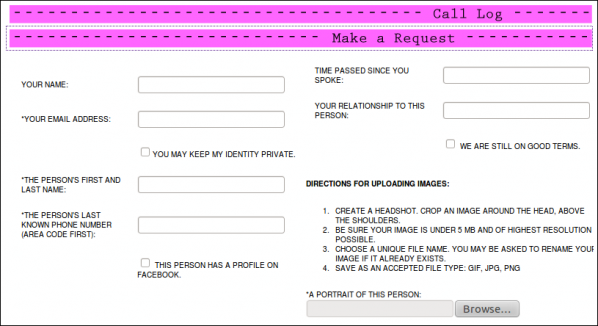

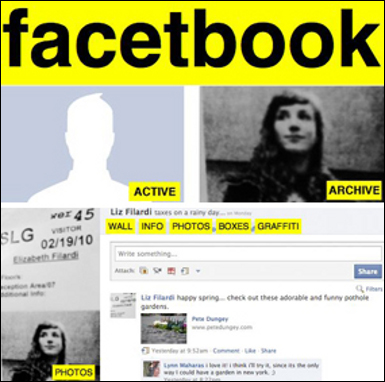

Let us jump to your third module “Facetbook.” How did you come up with the idea?

My day job is in design and I work with the content management system and blog software WordPress. When you edit a blog entry, a new entry is simply added to the database like an appendix to the original entry, so that you’re never editing the existing content of the database but merely adding to it. There is an archive of all your revisions. I started to imagine Facebook having a similar structure. It is possible that we are creating an archive of our life just by being active users, and yet, we have no ownership or access to it. Meanwhile, we present a singular identity within the construct of the profile. We update our profiles to project an idealized representation of ourselves. But if anyone could see the archive of these profiles and be privy to how they have evolved over the years, they would get a much more accurate sense of who we are, and maybe they would be able to see that truth far more clearly than we ourselves can see it.

With that in mind, I started to imagine that Facebook actually provides a literal construct of identity. Is this why it’s so addictive and popular? It’s not as if we can go back in time in real life and see written archives of every conversation we have had with friends, and every song we quoted in high school, and every trend we followed. We understand our own identities based on our memories and the occasional ephemera- diaries, photographs, videos, concert tickets, old clothes. In some senses, we don’t own our past, but only the precious ephemera. And in the space between the ephemera and reality, we get to imagine our own story. On Facebook, we can flip back through our activity and photos, and we construct our profiles based on how we see ourselves and who we would like to be. But we can never see old profiles, ones that we’ve since replaced, or content that we’ve removed. We get to curate our identity, manage the expectations of “friends” and find privacy by hiding behind the content we chose to share. That feels real.

And yet, there is something distinctly unreal about Facebook, which is that it is essentially a document, a record in and of itself. Facebook users live on a document. What if everything ever deleted, in fact, lived on? That makes me anxious. So I started looking for software that would allow me to archive my Facebook profile, and I found an experimental Firefox plugin developed by a group of computer scientists at Old Dominion and Harding University. Using their plugin, I started to archive my profile every time I wanted to change it. I wanted to see what it would be like to own an archive—to at least know what it would contain, even if I couldn’t control what Facebook did with my content.

The truth was that I was far more invested in my image and my Facebook life when I was in college than I am today. Maybe it would have been more insightful to capture that early period. But ultimately, the “Facetbook” performance became about investing in Facebook again and thinking about the stakes of participation. Knowing that I would be creating this archive and could delete my profile at any time, I tried to confront the extent of how people actually use Facebook. I wrote things like, “For brief periods of time, I have favorite profiles that I like to check,” and “even if you never change your profile, I will look at the same three pictures more than once. It gives my mind something to work with.” It feels strange to perform on a site where only a very acute mix of authenticity and performance is acceptable as a voice—you know, in posting status updates that display some charming aspect of yourself without exposing that you’ve given any thought to it. With “Facetbook,” I’m trying to expose Facebook as a site that serves a more libidinal function for people.

How do you see performance art changing in an environment where performance has, to some degree, become commonplace?

That’s a bold statement—one could argue that public life has always been about performance and that performance is no more commonplace today than in the past—but maybe it is more commonplace. The prominence of the social web—especially for younger generations who have restricted access in the real world—pushes public life online and into the realm of performance. People who are growing up with social networks are justifiably feeling like the center of the world with daily evidence to that effect. The lives of prominent, young YouTube vloggers are filled with connections to near strangers who make up coveted audiences across geographic boundaries. Any time someone has an audience, they become a performer. I think of Natalie Bookchin’s Testament, which is a multi-channel video essay that appropriates YouTube vlogs to speak to themes like work, economy, and war. The video diaries that are used in her piece exemplify a personal, confessional approach as seen in television shows like The Real World, and yet they are beyond television—these people are acutely aware that they are sharing their daily life not necessarily with friends but with an audience. The vloggers use common buzzwords and phrases that Bookchin pulls out to create the sensation that they are speaking in unison, just as news anchors and talk show hosts speak in an established language and tone. And that has become a normative way to socialize.

But performance art is entirely different from the spirit of performance on the social web. For one thing, the moment you disseminate over the internet or design your work for an internet based reception, you are creating media art, or networked performance, as Turbulence has preferred to call it. As far as my own experience with performance art, every time I perform something in public, I imagine being interpreted in two camps: an amateur throwback to the founding artists like Abramovic and Ono and Shneemann (young performance artists always seem so nostalgic for the power of the body and the live act, but it’s rare to pull off something powerful and new) and/or an urban prankster looking for attention in the local paper or city blog (a la the clever performance troupes like Improv Everywhere who disrupt city life with the exciting treat of surrealism). So I think the challenge for contemporary performance art is to find a place that is at once culturally relevant and striking, and to champion public space in a compelling way. It’s too easy to just take your actions to the streets of New York like plop art. People are already used to that. Lately I’ve been trying to create works that don’t come across as one-liners, but instead inspire the viewer to question what is going on, or to hold on to one particularly poignant affect or visual. The last thing I want to say—it gets problematic when one begins to qualify performance art as something that happens in galleries and museums because it was meant to defy the commodification of art, but I do want to say that I see it forging ahead in small galleries like Recess in SoHo.

Can you speak a little about your second module, “Black & White?” How did that come about?

That project started with research into the history of criminal stalking, as it relates to the popular contemporary idea of “Facebook stalking.” I wanted to explore the relationship between the tongue and cheek use of the word stalking to describe fairly typical activity on social networks and historical accounts of serious stalking in a time less saturated by social web technologies. I was fascinated by a famous case from 1988 between two co-workers at a Silicon Valley software engineering company. A young woman, a 22 or 23 years old Laura Black, started working at the company as one of the few female engineers. She sparked the unhealthy interest of a male engineer, Richard Farley, who became suddenly deeply obsessed with her. He stalked her for years, and while she sought help at her company when she feared for her life, she had trouble getting any real protection. She changed addresses and phone numbers, which only provided temporary relief, and got a temporary, ineffective restraining order. He would send letters, arrive at her house unannounced, and once joined her gym. In her anger and fear, it seems that she also wanted to show him that he couldn’t control her and that she was still going to enjoy her life and stay in the area. So there really wasn’t a collective intelligence about the threat of stalking at the time. Farley eventually arrived at the office with an arsenal of weapons and attacked the entire company. Black was shot in the shoulder and survived. Farley was arrested. Shortly after, the first anti-stalking law passed in California in 1989 and the story, along with a couple of other violent stalking cases, made national news.

Today, we don’t hear about cases like that because we have a lot more information and legislation to prevent that kind of thing. I can only assume that potential incidents are resolved before escalating to that level. We live in a different climate, where we share a lot more information about ourselves on the social web, and “stalking” is a hyperbolic term that describes the ultimately harmless activity of focusing on the available information of a single person without their knowledge or consent. The use of negative hyperbolic terms like “stalking” indicates a safer cultural climate, but also a latent guilt that may be rooted in cases such as the one illustrated in “Black & White.”

This makes me think of Twitter and the term “followers.”

Yes, it’s similar. Perhaps there’s a greater cultural need to be leader, with a collection of commoditized “followers” in tow. On the social web, we are less often ordinary humans and more often celebrities or actors splintered by various interests and audiences.

In “Black & White,” why do you transpose the stalking case into the paradigm of a social network?

Black&White is the name of a fictional network that looks much like Facebook, but it only contains two members: Laura Black and Richard Farley. Creating this site was a way to call attention to collective intelligence, to speak the language that we (on Facebook) have all learned so well. I knew that most people would intuitively be able to navigate the format and learn the story between the two people involved. In the context of the vast network of Facebook, it is striking that there are only two people in this network. Their content is linked through their job and location, despite their apparent lack of friendship. Underneath the relatively unassuming public profiles is a horrifying, one-sided correspondence in their message in- and outboxes. I wanted to dramatize their loneliness and emphasize the lack of will in their connection, which is how they will be remembered in the American collective consciousness. Hopefully this leads viewers to consider how and why the term “stalking” or the act of “stalking” has changed since the 1980s.

In terms of creativity on social networks, I think a lot of us are just filling in forms. The template of the social network is limiting. Will this have any affect on the direction of your work?

That’s a good question. I have felt confined by the structure of social networks, and even with the content of art that speaks directly to social networks. With I’m Not Stalking You; I’m Socializing, I started with the easiest form of art made to respond to social networks: a satire perpetrated through mimicry in other medias or dimensions, as seen in “Status Grabber.” This has been done in other works, as well. I guess I needed to make that piece so that I could see what was beyond it, and I believe I went a little further and yielded more insight in the other two modules. But now I’m starting to see how the social web simply permeates our consciousness and I believe I may find more insight if I take a step back from art on social networks altogether. As someone who has grown up on social networks, I’m interested to see how the themes that I’ve honed in my work with social networks will surface and return in works and areas of practice that move in a new direction.