This is a collection of artworks, texts and resources about freedom and openness in the arts, in the age of the Internet. Freedom to collaborate – to use, modify and redistribute ideas, artworks, experiences, media and tools. Openness to the ideas and contributions of others, and new ways of organising and making decisions together. This collection is intended to inspire, inform and enable people to apply peer-to-peer principles for making things and getting organised together. We hope that all art lovers, makers, thinkers, organisers and strategists will find something for them from this set of imaginative, communitarian and dynamic contemporary practices.

Commissioned and hosted by Arts Council England 2011

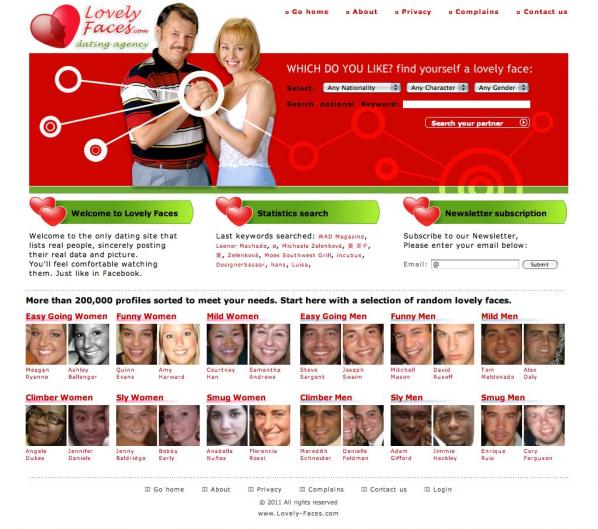

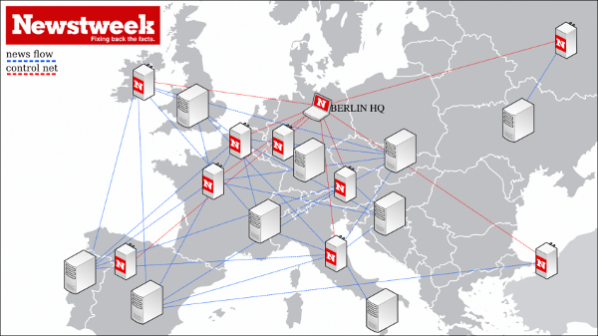

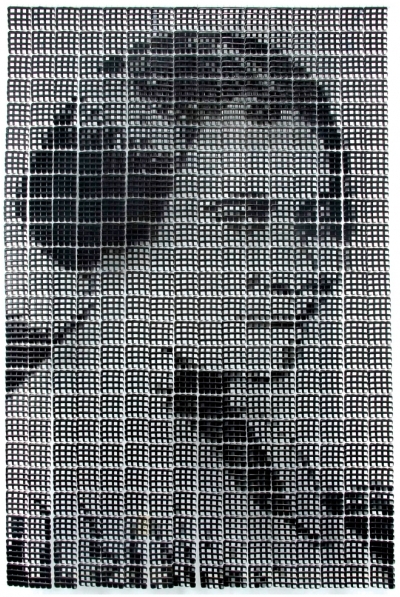

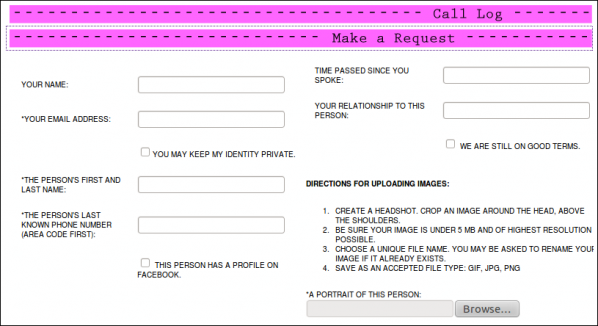

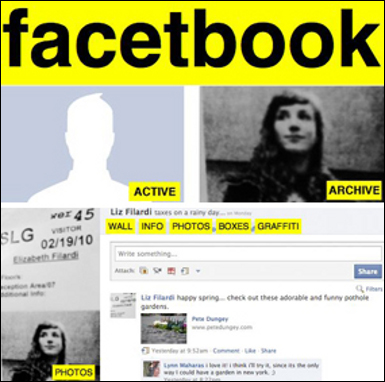

Face to facebook is the final project in a three part series named “Tha Hacking Monopolism Triology” by the two Italian artists Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico. It was launched on the 2nd February 2011, with a mixed media installation at the Transmediale festival in Berlin, and a press release announcing a new dating website called lovely-faces.com.

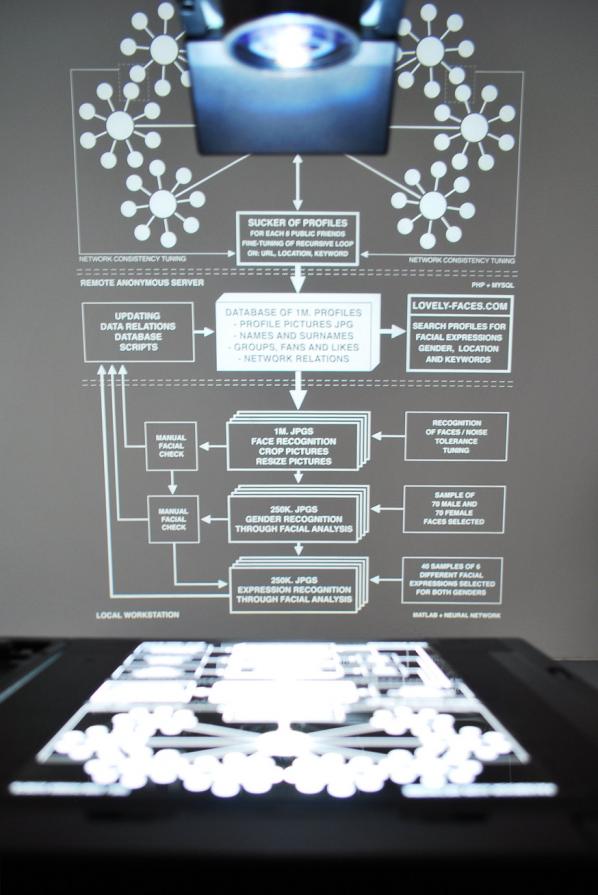

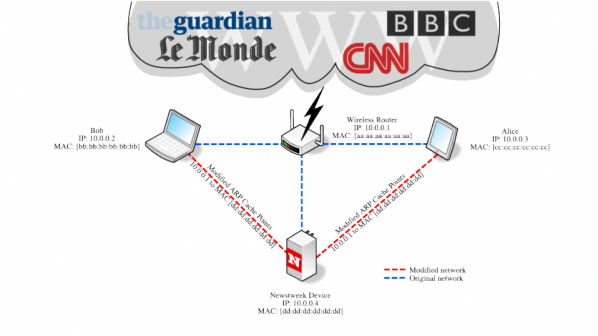

The set-up for the ‘Face to facebook’ project was to steal 1 million facebook profiles and re-contextualize them on a custom made dating website (lovely-faces.com). The data collected from the profiles was only information available publicly on the internet, like the users name and profile picture. No facebook account was needed to access it. The 1 million facebook profile pictures were then checked for images that were usable in a dating webstie context. The remaining 250,000 profile pictures were then fed through various face recognition filters to assign an assumed personality to the subjects and a new profile was created ready for the dating website. Once published on lovely-faces.com, interested pursuers could get in contact with the people behind the original facebook profiles through facebook messages.

On the 10th February, 8 days after its launch, the dating website lovely-faces.com was shut down. This was following a cease and decease letter from Facebook[1]. Back in 1999, the net artist Heath Bunting was also subject to a cease and decease letter, that time from American Express. The letter sent to Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico in 2011 (as PDF) can be seen here, and the letter sent to Heath Bunting in 1999 is published here.

This project, and the ripples it left on the media water, highlights an ambiguous relationship many have with facebook. Many people sign up, upload a smiling profile picture of themselves and declare personal details to the large corporation that is Facebook without concern. Not until these identities and personal images were scavenged and then reused, the ownership and potential audience of this personal data is questioned. As the artists state themselves: “The final step is to be aware that almost everything posted online can have a different life if simply recontextualized. “

“The process is always illustrated in a diagram that shows the main directions and processes under which the software has been developed. We found a significant conceptual hole in all of these corporate systems and we used it to expose the fragility of their omnipotent commercial and marketing strategies. In fact all these corporations established a monopoly in their respective sectors (Google, search engine; Amazon, book selling; Facebook, social media), but despite that their self-protective strategies are not infallible. And we have been successful in demonstrating this.”

Web 2.0 Suicide machine (http://suicidemachine.org/) is another project which deals with your online identity. It allows you to automatically delete all your social network profiles and it simplifies the process – according to their website 8.5h quick then a manual deletion. Incidentially, the facebook is not one of the profiles subject to deletion in the suicide machine anymore, following another cease and decease letter: http://suicidemachine.org/download/Web_2.0_Suicide_Machine.pdf.

Since the lovely-faces.com dating website is still closed down, the project now (September 2011) consists of: documentation of the process used to acquire the facebook profiles; documentation of the global mass media hack performance, in the form of news broadcasts, magazine articles and blog post referring to the project; legal correspondence between the lawyers of the artists and Facebook; a mixed media installation; a touring lecture given by the authors. The latter two being re-performed and installed in various venues around Europe and beyond. The former are all available on the website face-to-facebook.net

The ever changing nature of this project therefore makes it a great example of a piece of contemporary art of variable nature, one which is in constant flux and is formed by the cultural, networked and physical landscape surrounding it. It does not only challenge the ownership of your online identity, it is also a nuisance for a mainstream contemporary art market based on institutional preservation and commercial commodification. These disruptions may also be linked. On the one hand there is an action to copy a system collecting and commodfying people and then use them as assets in one’s art expression and experience. “In all the three projects, the theft is not used to generate money at all, or for personal economic advantage, but only to twist the stolen data or knowledge against the respective corporations.” And then on the other hand, it is an art project which is not straightforward to see what the remaining artefacts actually are, whilst defying the process of being added to traditional art collections.

Other Info:

The Hacking Monopolism Trilogy. Face to Facebook is the third work in a series that began with Google Will Eat Itself and Amazon Noir. http://www.face-to-facebook.net/hacking-monopolism-trilogy.php

Elin Ahlberg is studying Art and Visual culture at the University of the West of England in Bristol. She has been living in the UK, and Bristol, since her move from Sweden in 2006. As an artist, she works in a variety of mediums and produces work which aims to both amuse and provoke. Her practice and research is informed by quasi-anthropological observations and an interest in technology. “One year ago I gave up Facebook for lent. It was quite an interesting experiment and I realised how integrated my life was with the social networking website as I actually felt that I missed out on things.” Ahlberg’s essay Meanings constructed around Facebook can be found here http://elinahlberg.wordpress.com/2011/07/18/essay-meanings-constructed-around-facebook-2011/

Emilie Giles interviews artist Mary Flanagan about Tiltfactor’s latest social game, Pox: Save the People. http://www.tiltfactor.org/pox

Emilie Giles: Can you give an introduction to POX: Save the People, and why Tiltfactor was keen to produce a game which explored issues around immunisation?

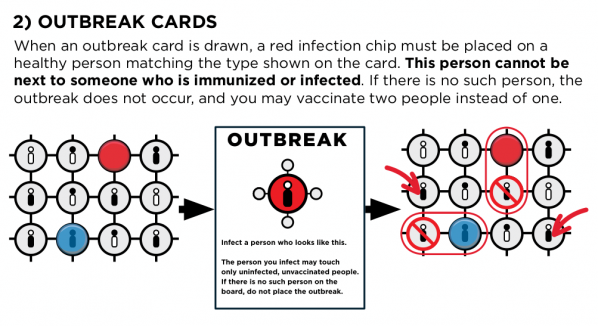

Mary Flanagan: POX: Save the People is a 1-4 player board game that takes on the public health issue of disease spread. We developed the game after wishing to pursue some public health issues and having prototypes games on cholera and HIV awareness at the lab. A local, and quite open, public health group called Mascoma Valley Health Initiative up in the New Hampshire region of the US approached us with the problem of the lack of immunization. At first, a game about getting people immunized seemed like one of the most “un-fun” concepts imaginable. But that sinking feeling of impossibility almost always leads to good ideas later, so I agreed to take the project on. We decided we could make something fun from the topic, and ruled out nothing, from crazed needles to taking the point of view of the disease whose main purpose in life is to spread around.

In our final version of the game, the board is modeled after a community, with the spaces representing people. The game begins with two people being infected with an unnamed disease, and the illness speads. Players try to contain the disease and save lives. There are vulnerable people among the population noted in yellow, and these people — pregnant women, young babies, and those in frail health — cannot be vaccinated.

EG: Schools have the option to download a sample lesson plan which incorporates the game into a science class. Please explain how you feel play can encourage learning in an educational environment.

MF: Play is one of the best ways to learn something — certainly tried and true classrooms such as Montessori method schools use play as a part of the curriculum. In the best scenario, play provides experiment space, where failure is ok. In games related to pedagogy, players can test the rules of the system at hand. POX players, for example, can try to cure all of the people on the board to test if this is a good strategy. They can test out best ways to avoid the spread of a disease. Ultimately, they get to make the meaningful choices from within the game rules. Playing POX while learning about real world diseases makes the phenomena more concrete, and gives the learner agency to think about what he or she might do to solve the problem.

The lesson plan for schools was edited by both trained teachers in US middle schools as well as doctors at Dartmouth’s medical school. Truly, then, the game is produced by a community. We could not have created the game to this level of quality without our partners, friends, and supporters.

EG: In most games, a competitive element is introduced to result in a ‘winner’ and ‘loser’. POX deliberately avoids this convention, encouraging players to work together in order to stop the virus. Why was the game designed for this mode of play?

MF: One of the ethos of Tiltfactor games is cooperative play. We like to make games in which players can use collaborative strategy. We define collaborative strategy games as those in which:

1. Games (or in some situations, components of games) where if one player reaches the lose state, everyone playing also loses;

2. The extent to which players win is positively correlated to the success of other players.

Often the most interesting games do not fit comfortably into stereotypical models of play. And because we make games about less traditional topics — public health, layoffs, GMO crops, and other political and social challenges –it is important that the game model itself reflect that. In educational scenarios or in community development, games mirror more closely the ways in which people work together to solve problems. So, the reason that POX is a cooperative game are deeply set in the lab ethos towards problem solving — we can only solve problems together.

EG: You are working on a digital version of the game for the iPad. What was your rational for approaching the topic through both a digital and physical platform and do you think these result in a different type of engagement?

MF: Yes — we’re also creating an iPad version and have an online version to launch as well. It is fascinating to make multiplatform games like this– we are a small lab so we’re doing most everything ourselves, including packaging, promotion, and research.

The differences between the platforms for the game are so dramatic, we’ve decided to conduct a study with the same game and different platforms, because watching people play the same game, the same rules, on a different platform clearly results in an different play experience. It is clear to me that very different things are going on, and I want to back up claims with data. For example, players play much faster if the game is computer based via an online game or the iPad. Players seem to like pressing buttons fast. In the board game, for example, observation shows us that players pick up pieces and discuss the moves with the other players, considering this option and that. The game piece actually becomes a kind of thinking object, I don’t know for sure, but it is very different. The speed up in time with a computer-based game appears to cut down conversation and meaningful dialogue that we’ve recorded in our last study on the board game. So, this is something that as games makers we’d really like to understand better, and share with others.

As an artist, I’m known to make media art and works that engage with play and game culture. In the laboratory context, I love developing and researching games with my team. I have amazing people to work with: Sukdith Punjasthitkul is my project manager who has a background in underground Asian culture, public health, and tennis; Zara Downs is a graphic designer and rural hipster who loves biology; Max Seidman is my accomplished undergraduate engineering student who has racked up several games in his time at the lab, and he loves wearing vests. Matt Cloyd is working with me, a recent graduate who is involved in sustainability issues in communities. Erika Murillo is a new student team member obsessed with social issues and animation. The list goes on. Part of the mission of what we do is to help the next generation who care about social issues have the tools to push what we do now, further.

EG: Your point about how you’ve found players to engage more in dialogue when involved in a board game is very interesting. Non digital games such as board games and pervasive urban games have become more popular over the past few years; do you think players are desiring a more socially interactive experience?

MF: Board games are enjoying a renaissance, it is true. First, because I think people really like playing together in a physical space. Perhaps the new technologies — Wii and Kinect — remind people of that. Perhaps they played recently at a family gathering and remembered how much fun they are. It is impossible to say. Second, there are some really well-designed games out there right now, and available in many countries (in part, due to online purchase power), that are certainly worth playing. People do really like playing with each other in physical space, and they still enjoy watching sports in person. Technology can help facilitate this as with mobile games and pervasive games, but it is not a requirement for a good game. I think different kinds of conversations may happen over board games as compared to digital games, but this is something that needs some data behind it. So, we’ll be doing a study on these nuances in my lab very soon.

EG: Looking at Huizinga’s idea of ‘the magic circle’, there is a clear boundary between play and non-play. What were the challenges in designing a game which straddles this boundary, on one hand trying to entice participants through play and interaction, and on the other attempting to create real life social change?

MF: Emilie, this is the riding question for all of game design engaged with social issues, and behind all of the debates on how gamification can incite real behavioural and social change. You’ve hit the nail on the head! There are many forms of play, some which stay within the game in a nice neat package, like our board game, and some that bleed over into real life, such as ARGs. But one should not be fooled into thinking that this means that the former is useless for education and social change, and the latter is obviously better at it. We are about to release our pilot study on the learning in the game, and the results are surprising, showing that learning transfers out of the game as players can apply concepts in the game to new topics. We’re careful researchers. As artists, and as people critical of flippant comments about games and change, we don’t take research lightly. We don’t, for example, cite major gains on attitudinal change and make assumptions on long term behavioural change from a 40-minute game play session. That would be bad science. So we scale our questions accordingly, and in fact, are still surprised and pleased by the effect the game has. I’ll update you on the specifics when the paper is published this autumn!

The deeper issues on the limits of how games can incentivise real behavioural and social change can get rather dark. How Pavlovian do we want to be in influencing people? Even those in social change arenas have to pause and think. Education and influence for good is what we strive for. Designers and companies can only go so far before we have something much more sinister at hand. This is why our team’s work on the Values at Play project (http://www.valuesatplay.org) remains relevant.

The Philosophy Of Software

Code and Mediation in the Digital Age

David M Berry

Palgrave Macmillan, 2011

ISBN 9780230244184

http://lab.softwarestudies.com/2011/04/new-book-philosophy-of-software-code.html

“The Philosophy Of Software” is an ambitious book by David Berry, who has turned his attention from the social relations and ideology of software (in “Rip, Mix, Burn”, 2008) to the question of what software means in itself. The philosophy that he has in mind isn’t the mindless political libertarianism attributed to hackers or the twentieth-century foundational mathematics that is the basis for the structure of many programming languages. It is a serious and literate philosophical reading of software and its production.

Software is an important feature of contemporary society that is rarely considered as a phenomena in its own right by philosophers. Software permeates contemporary society, Berry gives the examples of Google’s profits and the “financialisation” of the economy through software as examples of software’s importance in this respect. In reading this review on a screen you have used maybe a dozen computers, each containing multiple programs and libraries of software directly involved in serving up this page. Digital art and cyberculture often use and discuss software and philosophy (or at least Theory), but usually to illustrate a point about something other than software. The software itself is rarely the subject.

Rather than devote each chapter to a different philosopher’s views on software or adopting a pre-existing description of software Berry develops a novel and insightful philosophical approach to understanding and considering software. After providing an introduction to the foundational ideas and culture of software (Turing, Manovich, Cyberpunk), Berry presents a way of thinking through different aspect of software. The source code, the comments, the compiled program. Each stage and product of the lifecycle of software is given a philosophical context.

Heidegger emerges as the philosopher whose ideas first underwrite Berry’s approach to software. Latour and, in a surprising way, Lyotard play pivotal roles in later chapters. If these are not philosophers you were well inclined towards before then you are in for a pleasant surprise.

Berry presents some typographically appealing and culturally interesting code in order to demonstrate different features of the production of software. The swearing placed in Microsoft’s Windows source code comments by its programmers will mirror the frustration of many of its users. The Diebold voting machine code that illustrates the assumed social and gender roles of its human subjects show that code is very much a product of the social biases of its human authors.

Much of the code illustrated in the book is code poetry or obfuscated code. These are double-coded programs, where source code that can be run by a computer is written and formatted to be not just understandable but evocative and meaningful to human readers as something read rather than run. As with the comments in the Windows and Diebold code, a criticism that might be levelled at such code is that such textual decoration does not affect the compiled (or executed) form of the code.

But comments and formatting are what Berry refers to as commentary code and delegated code in his grammar of code. It has been said that code is written primarily for human beings to read and only secondarily for computers to execute, and obfuscated or poetic code is regarded as high art by many programmers. It must exemplify some of code’s salient features to them, and so it can be used to do so to a more general audience. And the cultural assumptions of code can survive from its source code into its execution and interface: witness the relief of many of Diaspora’s users than “Gender” was a free-form text field rather than a simple binary choice of “Male” or “Female”.

The final chapter on network streams provides a strong critical philosophy of social networking and other software that reduces human experience to a stream of software representations of events. After discussing what it means for a human being to be a “good stream”, Husserl’s idea of “comets” as a precedent for lifestreams and Lyotard’s idea of the stream (both of which predate the streams of the Internet by many years), Berry presents the idea of Dark Streams as a way of resisting the demands of Web 2.0. I would single this out as the most timely and invigoration section of the book and a must-read for anyone involved in producing, consuming, or critiquing networked software culture.

What doesn’t the book cover? There is no visual coding or livecoding. Berry explicitly avoids “screen essentialism”, where the output of code is concentrated on to the exclusion of its production and execution, but despite following programs from their writing through compilation to first assembly code then machine language, running software and algorithms (at the micro level) are not considered, nor (at the macro level) are the architectures of applications or of operating systems. Nor is testing except in passing. But this fits with the emphasis of the book on code as text, and the framework that it provides can be extended to these topics. Hopefully by Berry.

“The Philosophy Of Software” is particularly inspiring as a spur to further research. Each page is brimming with references in the style of the academic papers that many of the chapters were first produced as and whilst this style can be distracting at first (compared with popular science books for example) it is ultimately rewarding and gives the reader any number of fascinating leads to follow up.

What is important about “The Philosophy Of Software” is that it really is about what it claims to be about. Rather than trying to shoehorn software into an existing philosophical or political agenda it considers software as a thing in itself and finds those philosophers and philosophical ideas that best address the vitally important phenomenon of software. However much philosophy, computer science or cybercultural theory you may know this is a book that will set you thinking about software anew.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Featured image: Installation Speed. Public Space Exhibition Plattform Bohnenstrasse in Bremen September 2006. Aram Bartholl.

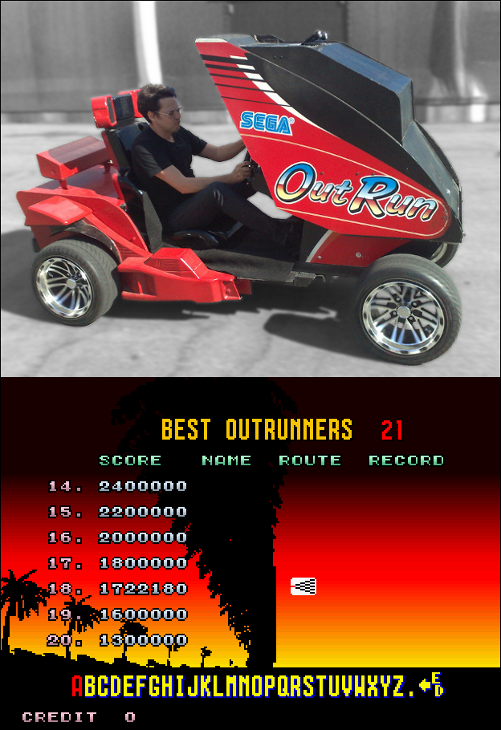

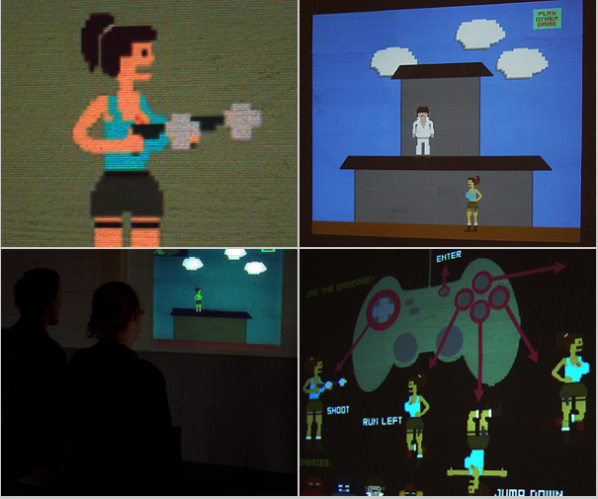

Pole Position, Outrun, F1 Racer and Need for Speed are some of the countless racing games that have attracted artists to explore a world of speed and burning rubber. In 2004 Cory Arcangel hacked the old Japanese Famicom driving game F1 Racer and removed, in the same way as he did in Super Mario Clouds, cars and other objects so that the only thing that remained of the game was the road and the landscape rushing toward the viewer.

Hacking and modifying videogames is one artistic approach, another approach in Game Art is to transfer virtual objects into real objects. The Swedish artists Simon Goldin and Jakob Senneby in an exhibition called Objects of virtual desire (2005), introduced virtual objects from players in Second Life. The object was then reproduced as physical art as limited edition in an exhibition, exploring immaterial production in a virtual world and how this can be transferred into an economy of material production. “Objects of Virtual Desire exploits the augmented value of immaterial objects to create and market tangible products, thereby reversing the process and highlighting the materiality of the immaterial.” Goldin & Senneby.

In a similar way both Aram Bartholl and Brody Condon have used virtual objects from Speed racing games. In Speed (2006) Bartholl made a 1:1 scale sign with red flashing arrows and placed the sign at a street in Bohnenstrasse in Bremen. The model to the arrows had he found in the game Need for Speed Underground NFSU where the red blinking signs leads the player on the right track. Condon on the other hand made an exact replica of a Lamborghini Countach from 1985, a model that he found in the game Need for Speed. The big different was that the car was made of plastic branches and there was only the outline of a car, in a 3D program you would say it was the wireframe of a car. What Bartholl and Condons does is that they investigates and problematizes the borderline between the virtual world and the reality by moving virtual and real objects between these two worlds. Worlds that today are more and more integrated and harder to distinguish.

The Dutch artists Marieke Verbiesen is also mixing elements from the virtual and real world in her work Pole Positon. Pole position was a racing game released in 1982 by Namco and was one of the first games to use the rear-view racer format, where the player’s view is behind and above the vehicle. In her installation the background in the game created by a realtime recording of a miniature landscape in perspective. Visitors can interfere in the landscape and be a part of the game by passing by the camera filming the landscape.

The ultimate combination of real and virtual game play is found in Garnet Hertzs work OutRun. Outrun was a game that was created by Sega 1986. Some arcade versions of the game were presented in a red sit down cabinet that looked like a car. Garnet Hertz has used this cabinet version as a model for his work and made a red real car where the front window is replaced with an aracde cabinet. With help of augmented reality the road ahead of you is an 8-bit video game, so at the same time you are playing the game you are driving down the road.

OutRun – Garnet Hertz. Images/video: http://www.conceptlab.com/outrun

“where game simulations strive to be increasingly realistic (usually focused on graphics), this system pursues “real” driving through the game. Additionally, playing off the game-like experience one can have driving with an automobile navigation system, OutRun explores the consequences of using only a computer model of the world as a navigation tool for driving.” Hertz

One thing that you could not blame racing games for is air pollution. In the installation “Colorless, odorless and tasteless” from 2011 this is exactly what you can blame Eva and Franco Mattes for.

They modified an old Pole Position game and installed a real engine in the arcade cabinet. When the player is driving the virtual car on the screen the room is filled with carbon monoxide from the real engine. So the risk is not only that you run out of coins but you are also gassed.

More of Mathias’s reviews on Furtherfield & bio : http://www.furtherfield.org/user/mathias-jansson

Featured image: Remixthebook Cover

“For us, art is not an end in itself … but it is an

opportunity for the true perception and criticism

of the times we live in.” Hugo Ball.

The challenge in trying to review a book like Mark Amerika’s Remixthebook, is the feeling you can only do justice to the text by doing the same with your review. The apparent simplicity coupled with the multifarious outcomes are intoxicating. You could be mistaken for believing that every possible remix would produce fresh and exciting outcomes. The key of course, is to have good source material in the first place. Also, to have developed a keen eye for what blends and meshes together and what doesn’t. Even the most disparate work requires judgment and prior awareness. Remixthebook asks us to consider the idea of remixology as part of the work of modern artists. The tone and style of the book is a blend of ideas, voices and thoughts with a myriad of concepts, which attempts be the very embodiment of the ideas it espouses.

Amerika explores various precedents for the remixological concept and draws on some known practitioners from the past: amongst them, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin. He explores existing ideas and welds them into his own armoury. Their ideas considered as part of his own creative practice, brought back to the now with new life, in our contemporary networked culture.

Other than just being a systematic breakdown of the different types of remixing and their potential outputs (or artifacts, as they might be better known in an art critical framework?) Amerika considers the pathways and theoretical underpinnings of remix culture. Having taken this beyond his own practice of the written word and web-based projects, he considers his recent and ongoing VJ work. Blending and collage-making with images during live music performances suggests some of the instinctive, instantaneous ideas that come out of a lifetime’s collecting, collating and absorbing of diverse imagery, words and cultural concepts. It’s within this process that he believes more novel outcomes can arise, against the constant flux of media creation and dissemination. It is the ‘becoming’ of the media artist that is revealed in the live remixing performance.

Reflecting on this process of cultural assimilation Mark Amerika, situates remixology within a wider creative output and theoretical framework. This involves a cross hybrid of everyday, mainstream references with high art and ‘high’ theory, all written in his at once complex and convoluted, yet easily read and enjoyable writing style. But like remixology, what looks simple is the result of deep reading and heavy conceptual thinking. This isn’t to say that you won’t have trouble decoding the writing and getting to the heart of his thinking, but it helps if you spend time with the text and allow the rhythms and structures to become second nature to you. Close reading allows the text to fall into place. For example, consider the following extract from the section eros intensification:

Here is where we enter the realm of

what I have been calling intersubjective jamming

which is different than the idea of a Networked Author

or Collaborative Groupthink Mentality that preys

on the lifestyles of the Source Material Rich

and seemingly forever Almost Famous.

It is worth remembering that Mark Amerika is a creative writer first and foremost. He uses theory as a palette from which to draw out ideas and situations for further reflection and to help give some context to the point he is trying to make. The text of remixthebook is an example of his creative practice in action, as much as it is a personal reflection on his attempts to develop a thought process for it. Theory becomes entwined in critical reflection and creative output. You don’t necessarily come to remixthebook for philosophical answers and hard academic points of view, instead you ride the maelstrom of thoughts and conceptualizing to gain a better handle on a way of considering artistic practice.

The website of the book (probably a ubiquitous extra for any media art-related publication these days) follows a natural path of inclusion and invites artists to take sections of the book and remix them according to their own aesthetic and remixological preferences. While some of the work brings in extra visuals and places itself in a flowing context of media streams, allowing different work to become part of the project, Rick Silva’s The Isarithm sources Amerika’s Sentences on Remixology 1.0 and explodes them out of the screen and into a layered and playful vortex of shapes and lines.

Will Leurs uses some captured footage taken directly off the tv screen for A Pixel and Glitch Hotel Room and combines it with some source material supplied by Amerika from several ‘lectures’ he has supplied. These lectures appear within several other contributors work as well. The point of some of these remixes and the varied forms they take (the collection includes some purely audio work) is that, as well as being interesting works themselves, they are exemplars and guides to even further potentials of the remixological principle.

Mark Amerika’s Remixthebook at times may leave you looking beyond it to the appendix or for any footnotes that would fill out spaces or help make conceptual leaps for you. That isn’t the point of the book. The idea is to take the book as a starting point and expand on your own creative process. Possibly the best approach is to literally cut-up the book and try some experimentation of your own, Brion Gysin style. Flex the covers back and pull out the pages. Through destruction and reconfiguration, the book might be bent to your will and become something that you can use. Perhaps the sight of a ripped and destroyed book would strike horror into some authors. I can’t help thinking that Mark Amerika would take great joy in the image and say that he’d planned it all along.

The remixthebook.com website

http://www.remixthebook.com

The remixthebook Blog

http://www.remixthebook.com/theblog

Remixology by OpenMedia.ca – a national, non-partisan, non-profit organization working to advance and support an open and innovative communications system in Canada.

http://openmedia.ca/remixology

Society of the Spectale (A Digital Remix)

By Mark Amerika On August 16, 2011.

http://www.remixthebook.com/society-of-the-spectale-a-digital-remix

REMIXTAPE 2.0 //

Remixology is a music blog based in Paris (France) devoted to remixes friendly music.

http://remixology.tumblr.com/

REFF- Remix the world! Reinvent reality! exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery between 25 February and 26 March 2011. http://www.furtherfield.org/exhibitions/reff-remix-world-reinvent-reality

Visitorsstudio – an online place for real-time, multi-user mixing, remixing, collaborative creation, many to many dialogue and networked performance and play.

http://www.visitorsstudio.org/x.html

Brion Gysin. Essays & Stories, Interviews, Excerpts & Publications

http://briongysin.com

Peter Lunenfeld’s book “The Secret War Between Downloading & Uploading: Tales Of The Computer As Culture Machine” (MIT Press 2011) presents a new way of looking at the cultural struggle for control of the Internet. Although the conflict between uploading and downloading may not seem secret since the Napster case a decade ago, and is indeed a common feature of net political debate, Lunenfeld is using the concepts of downloading and uploading to discuss not the copyfight but how human beings relate to each other culturally and socially through technology.

Lunenfeld immediately establishes both technical and poetic meanings for each term. Downloading is fetching data from a central server, or an animal eating. Uploading is sending data to a server and to other devices. It is also animal excretion and nesting, and the human creation of “superfluous” material goods such as paintings and experiences such as philosophy. Downloading for Lunenfeld is consumption, and in its current state dominated by broadcast media it is overconsumption leading to “cultural diabetes” in which mass culture plays the role of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS).

This is vivid, but the very definition of uploading that Lunenfeld starts with (sending data to other devices) also involves downloading (…to other devices). The “slow food” movement that he contrasts with super-sized, HFCS-laden American diets is a product of broadcast culture like any other hipster franchise. And outside the US, HFCS has never replaced sugar and state and independent television has provided an alternative to the HFCS of the brain that he describes network television as. If I am critical of this, and a (very) few of Lunenfeld’s other arguments, it is only because of the clarity with which the rest of them are presented and with which they are all developed. This is a serious, ambitious and forward-looking book about human use of networked computing machinery in an age when cybercultural lullabies and recanting cyberprophets have turned the field into an inward- and backward-looking one. It deserves serious critique.

As the subtitle of the book, “Tales Of The Computer As Culture Machine”, claims the computer, and particularly the networked computer, is indeed a culture machine. Computing machinery can imitate any other machine, and so any mechanically reproducible media (that is to say, all mass media) can be created, distributed and reproduced by computers. That the wide availability of computers and network access changes the balance of power in the media is a common claim, and one that it is easy to view cynically in the face of an Internet of lolcats and conspiracy theory blogs. But Lunenfeld takes us beyond this.

Lunenfeld builds up concepts and weaves them together into a coherent and thought-provoking worldview. Affordances, mindfulness, information triage, sticky vs. teflon objects, tweaking, toggling, continual partial production, unfinish, WYMIWYM, MaSAI. Some of these are standard in cyberculture and its critiques. Others are Lunenfeld’s own coinage. They build up to form a new vocabulary and a conceptual framework for new critical take on network culture. And, crucially, new possibilities for action on the basis of that critique. Like all the best Theory, Lunenfeld’s concepts identify something important in the real world and afford new ways of thinking about it and acting on it.

Having exhorted us to download mindfully through info-triage and to upload meaningfully, to make unimodernist media sticky and unfinished and to move beyond the revolutionary rhetoric of Web 2.0 to an evolutionary Web n.0, Lunenfeld describes a world of bespoke futures (“Creatively misusing scenario planning as a means toward crafting visions of the future”) and plutopian meliorism (the pluralistic pursuit of happiness within an open society).

The ultimate destination that emerges in the final pages of this new take on network culture is surprisingly high stakes. It is nothing less than an appeal to use the means of the aesthetics of the culture machine to pursue the ends of plutopian meliorism in the face of the closures of would-be theocrats and other totalitarians. That is, to use the net to reaffirm the enlightenment in all its ambition and seriousness leavened with and strengthened by the pluralism of postmodernism’s critique of modernity.

Is the framework that Lunenfeld has built up in the course of the book up to this task? Can it be used to address left and right-wing criticism from within and without mainstream Western society that Western culture is just, well, entertainment? Lunenfeld’s achievement is to build his framework from many small measures that can easily be applied practically and evaluated against vivid concepts. By the end of the book you can see how to act on this and to evaluate whether your actions succeed. And the effects of those actions, although not revolutionary (and Lunenfeld rightly points out that the rhetoric of revolution has been appropriated by theocratic and corporate reaction), will be in the direction of considered lives in a society that is more than simply entertainment as a result.

Lunenfeld finishes the main argument of the book by proclaiming that he will write utilities rather than manifestos. But he has written a fine example of both here: a call to action with a conceptual and practical toolkit to support it. With cyberculture at its most nostalgic and despondent at precisely the moment where network culture is showing its potential for both progressive and reactionary political change, the modesty of Lunenfeld’s means and the ambition of his ends are a much needed and easily embraced positive step forwards.

http://mitpress.mit.edu/catalog/item/default.asp?ttype=2&tid=12452

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

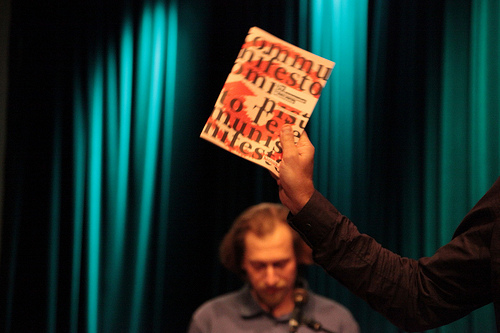

Marc Garrett interviews John Jordan and Gavin Grindon about their collaborative publication, A Users Guide to (Demanding) the Impossible.

Published by Minor Compositions

“This guide is not a road map or instruction manual. It’s a match struck in the dark, a homemade multi-tool to help you carve out your own path through the ruins of the present, warmed by the stories and strategies of those who took Bertolt Brecht’s words to heart: “Art is not a mirror held up to reality, but a hammer with which to shape it.”

Marc Garrett: In the introduction of your publication it says that it, “was written in a whirlwind of three days in December 2010, between the first and second days of action by UK students against the government cuts, and intended to reflect on the possibility of new creative forms of action in the current movements. It was distributed initially at the Long Weekend, an event in London to bring artists and activists together to plan and plot actions for the following days, including the teach-in disruption of the Turner Prize at Tate Britain, the collective manifesto write-in at the National Gallery and the UK’s version of the book bloc.”

I think readers would be interested to know how the ‘teach-in disruption’ and the ‘collective manifesto write-ins’ went?

John Jordan: I was not at the first Turner teach-in so can’t give first hand account. From what I’ve heard it was a wonderful moment where the sound of the action penetrated into the room where the Turner Prize were being held, as the back drop of the channel 4 live link up. Kind of perfect, because it was a sound artist who got the award.

As for the National Gallery event – this was held during the evening after one of the big days of student action. Having spent the day being trampled on by her majesties police horses, a load of us went up to the National Gallery and mingled in front of Manet’s Execution of Emperor Maximillian, opposite a corridor that held a Courbet painting. It was a perfect placement as Courbet of all the 19th artists was really the one who understood the role of art within an insurrection, putting down his paintbrushes to apply his creativity directly to the organising of the Paris Commune of 1871 just as the impressionists fled the city to the quiet of the countryside. Only to return a few years later when Impressionism was launched, as a kind or artistic white wash over the massacres of the Commune, a return to normal bourgeois representation. Courbet had used the rebel city, a “paradise without police” as he put it, as a canvas to create new forms of social relationships and new ways of public celebration, including the destruction of the monument to Empire and Hierarchy, the Vendome column.

Several hundred artists and art students at a given moment sat down and occupied room 43, telling the staff that we would leave once a collective manifesto had been written. Which is what happened. Small groups of 10 or so were formed as the guards and director of the gallery paced up and down unsure of how to react, each group worked on points for the manifesto which were then read out and merged in ‘The Nomadic Hive Manifesto’ – http://www.criticallegalthinking.com/?p=998 – it was an extraordinary moment of collective, emergent intelligence, a reclaiming of a public cultural space from the realm of musefication and representation.

MG: ‘A Users Guide to (Demanding) the Impossible’ features quotes by individuals and groups, who have inspired many of us in the networked, Furtherfield community. But, I am also aware that you may be part of a younger generation, presently experiencing the brunt of education cuts imposed by the current government coalition. Could you explain how these cuts are effecting you and your peers?

JJ: Well I wish I was a younger generation !!! I’m 46 years old, it was written for the youth !! You should talk to some arts against cuts folk, I can put you in touch if you need to?

Gavin Grindon: I’m not exactly ‘the younger generation’ either, but I guess I’m in a strange position between. I recently finished my PhD, so a lot of my friends are either students or just becoming teachers. There aren’t many jobs about, academic or otherwise, and most of them are doing multiple part-time, short-term jobs to make ends meet, without the assumed security or career progression of a generation before, and the cuts are only going to exacerbate that situation. I guess what’s new is a recession on top of these kind of precarious work conditions, which extend far beyond the University. With part-time, hourly-paid and non fixed positions, replacing real jobs.

Of course it’s damaging, but it’s also been inspiring to see students responding to turning over lessons to discuss the cuts and seeing them on the streets. It’s politicised a lot of young people, and there’s an opportunity there. At one of the University’s I work at, it was great to see the art students working together to make protest banners, not in their studios but in the foyer, where other people could see and join in. And when I started talking with them, we began to realise that with all the technical resources of an art school at their disposal, it was possible to be much more ambitious and imaginative than just making banners or placards, the standard objects of protest. But the history of a lot of art-activist groups who had these kind of ambitions isn’t taught, never mind the more popular history of the arts of social movements itself. And it’s not just about knowing and being inspired by some great utopian tales of adventure, or understanding yourself as part of a historical legacy – it leaves you strategically disadvantaged about what can be done. So starting a conversation with these students, was, as JJ says, kind of the idea behind the guide.

MG: There are various other creative protest groups such as UK Uncut (http://www.ukuncut.org.uk/) and the University for Strategic Optimism (http://universityforstrategicoptimism.wordpress.com/), whom I interviewed live on Resonance FM, December last year (http://www.furtherfield.org/radio/8122010-university-strategic-optimism-and-genetic-moo). Are you connected to any of these creative activist groups, and are there any others in the UK you would like us to be more aware of?

JJ: Yes – I’ve worked with UK Uncut, and was unfortunately arrested in Fortnum and Mason, whilst recording the BBC 4 afternoon play, but that’s another story! There are lots of interesting groups that work on the edge of art and activism, right now a space to keep an eye out for and to visit is THE HAIRCUT BEFORE THE PARTY – http://www.thehaircutbeforetheparty.net/ – set up by two radical young art activists who have opened a hair dressers that offers free hair cuts and political discussion about organising and friendship, rebellion and the material needs to engage in it. The salon is in 26 Toynbee Street, near Petticoat Lane and open till November. It’s an interesting example of a medium to long term, art activist project that attempts to create new forms of relationship and affinity, and sees itself as building radical movement and not simply representing them.

GG: Yeah, again the idea of the text was to build on the connections that are already there, which THBTP does too in a more informal, social way. And for sure, you shouldn’t be seen at the June 30th strikes or UK Uncut’s support actions without a flash new haircut. I should also get a plug in for Catalyst Radio – http://www.catalystradio.org/ a new 24/7 DIY UK-wide activist radio station, which started up the other week and is still growing, and brings together a lot of radical radio projects from around the country.

MG: Do you share a mutual empathy and respect for other protesters elsewhere such as those in Spain and in Greece, and in the Middle East?

JJ: Of course. Although it feels like the camp protests are lacking a conflictual approach and without the mixture of conflict and creativity, protest can easily be ignored, which is a bit what has happened with all the European camps. Although sitting here in the British library its easy to be critical ! Whatever happens, those involved in the camps will have tasted politics, new friendships, alternative ways of organising etc… As for the middle east, its all still in flux, who knows what will happen and the role of artists and musicians has been pretty key in setting the powder kegg alight there..

GG: Yeah, though I think there’s a tension between the symbolic solidarity of occupying city squares and the strategic differences between activist practices in different countries. I think solidarity between these struggles is massively important, though I’m personally not sure how it’s best to manifest that here right now.

MG: In the User’s guide, it mentions the workshops in art and activism at the Tate Modern, held by the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (Labofii), entitled it ‘Disobedience makes history’. And that Laboffii “was told, in an email, by the curators that no interventions could be made against the museum’s sponsors (which happen to be British Petroleum) [..] decided to use the email as the material for the workshop. Projecting it onto the wall they asked the participants whether the workshop should obey or disobey the curator’s orders.”

What I find interesting regarding this episode is both that a big institution would take the risk of inviting in art and activist culture to their usually, protected environment whilst being sponsored by British Petroleum; and the different forms of controversies reaching the public from such situations. I am surprised that Laboffii would even consider doing such a project in the Tate Modern in the first place, but also pleased, because of the dialogue that has come out of the clash of different political contexts. So, isn’t it the case that we need to explore issues of corporate corruption further within these big institutions so that those who would not usually consider such things are suddenly faced with the issues?

GG: I’m sure JJ has plenty to say about this. But more generally, it depends *how* they function as a platform. An art gallery or a university can be a great discursive space to explore issues, but the bounds of that debate are also strictly limited in lots of ways. This is a problem with the idea of a bourgeois public sphere. Most often, that boundary is that you can debate whatever you like but questioning the basic systemic assumptions on which such spaces rest isn’t possible, at least not in a practical way. The lab’s workshop at the Tate tried to question exactly that kind of assumption about what culture is for, and who it benefits. But for many activists from social movements, who have less faith in the public sphere and its institutions to resolve issues by discussion, that neutered debate is more of a problem than a benevolent gift to the public, and they have to take a different approach. Its not necessarily opposed to those institutions as a whole, but just asks them to make good on what they claim to be.

JJ: It’s a long story, but the key is to be able to put one foot inside these institutions and to be not frightened to KICK. But not to KICK symbolically, to really kick, to really shake them up and to be able to let go of one’s cultural capital. The Labofii will NEVER be re-invited to do anything at the TATE, bang goes all our chances of a retrospective in the fashionable art activism world !!! 😉 But, what we gain is that we were free ! When the curators told us that we could not do anything, could not take action against BP and we refused to obey them, we were free, we could do what we wanted because they could not give us anything in return. The Zapatistas say, “we are already dead so we are free” – when power can give you nothing you want, you can do anything.. this is a very powerful moment. To see the faces of the curators, the head of public, the head of security etc during the meeting where they tried to censor the lab, was priceless – they had always had power over artists, because artists will normally do ANYTHING to get their work in the Tate, but we did not care, we cared about the politics, about the actions, about climate change and social injustice – we were more powerful than the institution in that moment because we were no longer dependent on them.. it was one of the most beautiful moments… and now the movement against oil sponsorship is spreading everywhere. The message is simple, give up your cultural capital throw away your dependence on these institutions and be free…

MG: I come from a background of hacking, social hacking and D.I.Y culture, and instead of going to University I chose to be self-educated, creating alternative groups for self discovery and art with dedication to social change. And even though, many are fighting the education cuts right now, what are your own ideas around self-education, do students really need to go to college now that there are so many different forms of information and ways in creating one’s own place in the world ‘with others’?

GG: A lot of experiments with autonomous self-education have sprung up recently which ask just this question, like the Really Free School (http://reallyfreeschool.org/), there are even some more institutional business-model experiments online with peer-to-peer education. But at the same time the catchment of both of these is relatively narrow at the moment, so I think there’s still a place for these kind of education institutions, and there are interesting radical experiments going on all over, either by individuals or whole departments, although the cuts to institutional funding for education by the government changes the playing field again, so there’s an opportunity for something like this to become less marginal, both inside and outside the university.

MG: JJ, In 2005 you wrote, Notes Whilst Walking on “How to Break the Heart of Empire”, in it you write “Radicals are often vulnerable souls. Most of us become politically active because we felt something profoundly such as injustice or ecological devastation. It is this emotion that triggers a change in our behaviour and gets us politicised. It is our ability to transform our feelings about the world into actions that propels us to radical struggle. But what seems to often happen, is that the more we learn about the issues that concern us, the more images of war we see, the more we experience climate chaos, poverty and the every day violence of capitalism, the more we seem to have to harden ourselves from feeling too much, because although feeling can lead to action we also know that feeling too much can lead to depression and paralysis…” How the hell do you remain positive when you know how many horrible and disgusting things are being done to decent folks and the planet all of the time?

JJ: Unfortunately there are no magic recipes that can protect us from such feelings, a lot depends on context on our particular situations etc. But here are a few tips that have helped me keep the despair of capitalism at bay:

1) Resist the spell of individualism that capitalism tries to weave around us, a spell that chains us to the fantasy of autonomy and keep us in a state of sadness and paralysis. Break this spell and its toxic chains by realising that you are part of a greater whole, that working with others gives us strength, that seven minutes making real friendships (face to face) is more political than seven days glued to a computer browsing social networks in a trance, that inevitably fails to shake the loneliness of modern life.

2) Build a gang, a group, a collective, a crew – remember the joy of plotting things together, the power and possibilities when work and imagination is shared. In fact, imagination finds it’s insurrectionary potential when we share it, when it’s freed from the privatised ego, escapes from shackles of copyright and the prison’s of the art world.

3) Learn the skills to work together with others, consensus decision making, group facilitation, conflict resolution etc. We need to re learn collective working methods, capitalism has destroyed all our tools of conviviality and we need to reclaim them back, recreate new forms of being together.

4) Redefine Hope. Not as something that will come and save us, like a saviour, but as something that comes from not knowing what will happen next, something that takes place when we act in the immediate moment and don’t know what will happen and trust that history is made from acts of disobedience that did not necessarily have any idea of what the next step was…

5) Remember that victory is not always what happens, but what did not happen. Social movements tend to forget this. Look at all the nuclear power stations that WERE not built, all the wars that did not happen, the laws that were never passed, the free trade agreements that were never agreed on, the repressions that the state could not get away with, the gmo’s that were never planted. One of my favourite books, what I call prozac on paper, is Rebecca Solnit’s HOPE IN THE DARK (http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/28048.Hope_in_the_Dark) – it’s a lovely little book which redefines hope in the most beautifully optimistic way, recommended reading when capitalism seems irresistible.

6) When everything appears useless, try to change your conception of time… think deep time, not shallow modern now time, but think about the generations that went before you and those that will come after you. Try to imagine what the generations of the future will think about your actions, imagine those from the past that fought for the emancipation of slaves and yet never saw the results of their actions, those who died for the eight hour day, for the right to build a union, the right to vote or publish an independent magazine. Spend time imagining how those alive in 50, 100 years will view your life and work…

MG: In the publication, you mention Marx and Debord. “We can all be engineers of the imagination”…”that our “general intellect”, all the collective knowledge and skills we use in making things, are taken away from us and embodied instead in the machines of our work. What would happen if we somehow re-engineered these machines if we did what Guy Debord argued and started, “producing ourselves… not the things that enslave us.” Do you see the recent cuts across the board as an example of how the powers that be are actively dis-empowering the working classes?

GG: Definitely. The cuts aren’t just about an experience of ‘austerity,’ however long term, but constitute a historical attack on poor and working people. They’re an attempt to technically recompose the material of the institutions, structures, ideas and habits people live through, in order to limit their ability to resist and remake them for themselves. In factory production, that involved the local restructuring of machine-labour, but later at a wider level Keynesian economic restructuring. This neoliberal restructuring of education is an extension of capitalist discipline into a new area, an attack on a social space which has historically been a base for social change. The government has made this pretty clear by, for example, David Willetts’s dictate amidst these massive cuts, to the Arts and Humanities Research Council, that the Tory party’s vacuous advertising slogan “the big society” become a core research area, replacing the less ideologically narrow area of ‘communities and civic values’; and the Department for Business and Innovation’s concomitant rewriting of the 1918 Haldane principle, that research directions are best decided by researchers through peer review.

The optimistic take on this is not that it’s an inevitable recuperation of resistance, which was the position Debord tended towards in the end, but that capital is always on the back foot – that its own developments are driven by and a response to social movements. That it’s an open dialectic (or if you prefer, not a dialectic at all). There’s a kind of neurosis to it, although rather than excluding the other to maintain its ego, the state is including everything to stave off other possibilities – you can see this in the language. The whole discourse of ‘participation’ and networks in business (and since the 1990s, also in art), is as Boltanski and Chiapello observed in their book the New Spirit of Capitalism, a recuperation of the language and terms of 1960s social movements – movements which first properly gave birth on a mass scale to the kinds of self-consciously autonomous and creative politics, or art-activism, which we talk about in the guide. Likewise, the big society is focused on mutuality, and there’s a strange recuperation of libertarian and radical thought by the thinkers behind it like Phillip Blonde. In this case, you’re left with a stunted vision of the anarchist idea of mutual aid, without any institutional aid, and structurally limited mutuality. But rather than simply critique this, I’m interested to look at how we might otherwise structurally and materially embody other kinds of social relation. Obviously this starts on a much smaller scale, and is often more directly materially embodied. University departments’ attempts to support radical philosophy within existing institutions and setting up new autonomous radical art institutions are two possible, but not mutually exclusive, directions here. As, of course, at the most local, accessible level, are the art-activist practices and objects we discuss in the guide.

Our new book-film is out “Les Sentiers de L’utopie”

Free online (in french) : http://www.editions-zones.fr/

Our blog: http://lessentiersdelutopie.wordpress.com/

our twitter: @nowtopia

3 different links to download the publication:

http://www.minorcompositions.info/usersguide.html

http://artsagainstcuts.wordpress.com/2010/12/06/a-users-guide-to-demanding-the-impossible

http://www.brokencitylab.org/notes/required-reading-a-users-guide-to-demanding-the-impossible

The Font used was Calvert is by Margaret Calvert, designer of our road signs.

Words: Gavin Grindon & John Jordan Design: FLF Illustration: Richard Houguez Original Cover: The Drawing Shed Produced by the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination, London, December 2010. www.labofii.net Anti-copyright, share and disseminate freely.

More about Minor Compositions – a series of interventions & provocations drawing from autonomous politics, avant-garde aesthetics, and the revolutions of everyday life.

http://www.minorcompositions.info/

Crude awakening: BP and the Tate. The Tate is under fire for taking BP sponsorship money. Does corporate cash damage the arts — or is it a necessary compromise? We asked leading cultural figures their view. Interviews by Emine Saner and Homa Khaleeli. guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 30 June 2010. http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/jun/30/bp-tate-protests

The first interview with Jake Harries, took place on one of Furtherfield’s Radio broadcasts on Resonance FM, earlier this March 2011. Fascinated by the historical context that came out of the radio discussion, we asked Jake for a second interview, this time it took place via email.

Jake Harries has been making music in Sheffield since the 1980s and is a sound artist, musician/producer, composer and field recordist with a strong interest in media art and the practical use of Open Source audio-visual software. He was a member of electronic funk band Chakk which is best known for building Sheffield’s first large recording studio, FON Studios, in the mid 1980s. He is currently one of “freestyle techno” trio Heights of Abraham and The Apt Gets, a band which uses guitars and only Open Source software on recycled computers to create songs from spam emails. He is Digital Arts Programme Manager at open access media lab, Access Space, and the current curator of the LOSS Linux Open Source Sound a website dedicated to music made with FLOSS.

Marc Garrett: Lets talk a bit about your own history first. You were in a band in the 80s called Chakk, could you tell us a bit about that?

Jake Harries: Chakk was based in Sheffield during the mid 80s and we are best known for building a heavily used facility, FON Studio, Sheffield’s first large commercial recording studio. Chakk made “industrial funk” music, a mix of funk base lines and drums with influences ranging from punk to soul to free jazz and electronica. Our music was aimed squarely at the dance floor. We believed that technology, in this case the recording studio, was the most important instrument a band could have both creatively and financially.

MG: So, you are part of the electro music history of Sheffield with bands like Cabaret Voltaire & The Human League in the late 70s – 80s?

JH: Yes, but the band itself didn’t have too much commercial success, a couple of indie chart top 10s and a couple of low 50s in the main UK chart, so few people remember us now. People are more likely to remember FON Studio.

Recently a documentary has been made, called The Beat Is Law, about Sheffield music at that time, so perhaps there will be a bit more interest in the band.

MG: Open Source software is freely downloadable from the Internet for free and Linux is the most widely used Open Source operating system. How long have you been using Linux operating systems and Open Source?

JH: I had heard of Linux before, of course, but I came across music applications which were developed only for Linux in 2002-3 while searching for new software tools. These intrigued me sufficiently to install the operating system on a pc which I had fixed where I was working at the time.

MG: Do you feel that artists, techies and others are choosing Free and Open Source resources for reasons which connect with ethical and environmental issues and concerns?

JH: Well, I’d like to integrate into this answer the general themes of openness and transparency. FLOSS is akin to an encyclopedia of how to make things in the software realm because all the code is available for anyone to download and develop; closed, proprietary software is like a “sealed box” which it is illegal to prise open.

But it goes a bit deeper than that: in the world we are living in now the “sealed box” is increasingly becoming the mode of choice for all kinds of products, most of which, because they are designed to be superseded, have built in obsolescence. When something goes wrong with a product, you are unable to fix it yourself because you can’t get inside it, and even if you could you can’t find out how to fix it. If it is out of warranty, either you pay a lot of money to get it fixed or you throw it away; then you buy a new one! (Which is what the market wants you to do…)

So, it feels very much as if we are surrounded by technology we are not encouraged to understand and products with a limited life span: the obvious environmental concern is, “what happens to my ‘sealed box’ when I throw it away?”

Using a Linux operating system can increase the useful life of a computer by several years, and perhaps, if you can hack into them, other products too. So it is great if both hardware and software are open.

We also know that sharing knowledge is generally considered to be a good thing as it allows people to build on what has already been discovered. Being able to give the people in workshops the software they have been learning to use because it is FLOSS, rather than them having to pay several hundred pounds because it is only available on a commercial license, is great and often the idea of this kind of freedom takes a while for people to get used to if they’ve not come across it before.

MG: Why is it important as a creative practitioner to be using Open Source?

JH: Well, personally, I have realised that what I’m interested in is freedom, not just as a hypothetical, but the practical reality, finding out how to achieve some of it and if it is possible to sustain it. Free & Open Source operating systems and software are one way of stepping out side of the constant pressures of the commercial market places which dominate our culture.

We tried this in Chakk in the 80s with FON Studio, attempting not only to personally own the means of producing our music, the studio (allowing us to be outside the corporate system of production), but also to be able to explore our creativity in the way we wanted to. In the case of Chakk it didn’t work out. We had, rather cheekily, persuaded a giant corporate (MCA Records, owned by Universal) to bank roll it all and they found ways of scuppering our plan by making our product conform to their idea of the market place: transforming it into something “radio friendly” and bland, taking the energy and urgency out of the music. We were quite a politicised band and that energy was essential to our musical integrity.

However, when MCA dropped us we had a recording studio which could help nurture new music without too much external pressure, and this led to records produced there by local acts fulfilling their potential and going into the charts.

I think it is important for artists to have certain freedoms, to have ownership over the means with which they create their work. The fact that FLOSS allows you the user the potential of customising the tools you use and to distribute them freely via the web or other means is quite profound. And one of the real benefits of using FLOSS as a creative practitioner are the use of open standards and formats.

MG: OK, let’s move onto your own band: The Apt Gets. Now, since The Human League & Cabaret Voltaire, a whole generation has experienced the arrival of the Internet. Your group seems to reflect this aspect of contemporary, networked culture – a kind of Open Source rock band. Could you tell us about this band The Apt Gets, how you all got started and why?

JH: It began with workshops I was leading for musicians on FLOSS audio tools in 2007. The idea of an “open source rock band” came up – at the time we didn’t think there was one so a couple of the workshoppers and myself formed one. The Internet was the main source of inspiration really: we used recycled computers with Linux we’d downloaded, as well as guitars and vocals. I’m interested in re-purposing junk as raw material for creative processes and decided to re-use some of my spam emails as lyrics. We all hate spam, but re-contextualising it like this is fun, as is introducing a song by saying, “Here’s a classic Nigerian email asking for your bank details”. The themes of spam emails are generally things like greed & money, status & sex appeal as well as “meds”, so there’s more to them than you might think.

MG: Now, I personally know why, but others who are not as familiar with Linux and Open Source Operating systems, will not immediately know this. The naming of your band’s name – it’s specific to installing software. Could you tell us more about that?

JH: On a Debian Linux based operating system one can install software from the internet using an application called apt. One could type apt-get install the-name-of-the-software into the command line and apt will get the software from what is called a repository on the Internet, where the software is stored for download. We thought that if you called someone an Apt Get it could be interpreted as an insult meaning something like, clever bastard. So, that’s why we named the band The Apt Gets.

MG: How long has your research project with FLOSS been going?

JH: The research project started in 2007. Ever since I began to use FLOSS I’ve been interested in the practical realities of using it, particularly as an every day set of tools, as an ordinary computer user would use it: for instance, when I do work on the arts programme at Access Space I don’t use anything else. So, it made sense to discover how a number of non-Linux using musicians would find using FLOSS audio tools – if I was being an advocate for FLOSS I ought to look at it from the new user’s angle and discover how far they could go and what kind of time scale they need.

MG: And the web site address is?

JH: http://audiotools.lowtech.org

MG: How easy is it for someone with little or no experience of Open Source software and Linux based operating systems to install it?

JH: It is quite easy nowadays. A Linux distribution like Ubuntu has an easy to follow installer which allows you to create a dual boot if you want it, that is, keeping your Windows system as well so you have the choice of both.

MG: At Access Space in Sheffield, you are curator and researcher of LOSS (Linux Open Source Sound) a website dedicated to music made with FLOSS – which is basically LOSS with the letter ‘F’ added, meaning ‘Free Linux Open Source Sound’ – FLOSS!

JH: Yeah! Free is the word! It is a repository for music made with FLOSS tools and released under a Creative Commons license. You can freely download and upload tracks. Initially it was based around two projects, a physical CD issued in 2006 curated by Ed Carter, and LOSS Livecode, a mini conference and gig curated by Alex McLean and Jim Prevett based around the international livecoding community. The website is at http://loss.access-space.org.

MG: What is Access Space and what is different about them as a group?

JH: Access Space is an open access media lab, based in central Sheffield. It uses reused and donated computer technology to provide Internet access and Open Source creative tools, free of charge, five days a week. It started in 2000 and has become the longest running free Internet project in the UK.

We recycle computers, put on art exhibitions, creative workshops and sonic art events. We’re currently developing a DIY Lab, modelled on MIT’s FabLab or fabrication laboratory. This will be an interface between the physical and digital domains where new kinds of creative activity can be developed.

MG: What operating systems would you suggest to newbies coming to Linux for the first time?

JH: Ubuntu or its derivative, Linux Mint, are both very user friendly for everyday use. For audio try Ubuntu Studio, 64 Studio or Pure:dyne.

MG: And regarding yourself, what are you using?

JH: I have set up eight Ubuntu Studio pcs for use in audio and video workshops at Access Space; and I use Pure:dyne live DVDs if I’m out and demonstrating on other people’s pcs. For everyday use, again Ubuntu Studio with a few additional applications like OpenOffice.

MG: Thank you for a fascinating conversation.

JH: It was a pleasure…

Open Access All Areas: an Interview with James Wallbank about Access Space by Charlotte Frost

http://www.metamute.org/en/Open-Access-All-Areas

Ubuntu Studio 11.04 release.

http://ubuntustudio.org/

64 Studio Ltd. produces bespoke GNU/Linux distributions which are compatible with official Debian and Ubuntu releases. http://www.64studio.com/

Puredyne is the USB-bootable GNU/Linux operating system for creative multimedia.

http://puredyne.org/

Pure:dyne Discussion, interview by Marc Garrett & Netbehaviour list Community 2008.

http://www.furtherfield.org/interviews/puredyne-discussion-netbehaviour

“You Are Now the Electronic Man” are the words that appear before even opening the website for The Electronic Man, a project initiated by Salvatore Iaconesi and Oriana Persico of Art is Open Source (AOS) and FakePress. And by becoming part of The Electronic Man, sharing your emotions as they become linked through QR Codes and help to build the frame of The Electronic Man, you are participating in a real time global performance.

This real time global performance relates to conceptual experiments by AOS and FakePress, in remixing reality and creating new sensual experiences with technology. The email interview took place after their recent exhibition at Furtherfield’s gallery in London, called REFF – REMIX THE WORLD! REINVENT REALITY!, which happened during February, March 2011, and during their current project The Electronic Man. We discuss AOS’s ideas and intentions, regarding their activities of performance and use of technology, and their methods of engagement with anthropology and biology.

Renee : The Electronic Man is quite an ambitious project. What inspired you to begin building the Electronic Man?

Salvator and Oriana: The Electronic Man is actually a very simple project (if quite a difficult one in terms of “making it happen”) as it is a direct poetic interpretation of a theory by Marshall McLuhan that goes by the same name. We decided to take the famous statement by Marshall McLuhan quite literally and transform it into something that is really happening in the world: “Electronic man like pre-literate man, ablates or outers the whole man. His information environment is his own central nervous system.”

What we wanted to do was to make our statement for the centennial of McLuhan’s birth, but to avoid the form of the “conference presentation” for it, and to show in a powerful way how the ideas expressed by McLuhan are really taking place in the world which we experience every day. So we decided to produce a performance, a global performance.

With the wonderful support of Derrick de Kerckhove, and of the MediaDuemila magazine (and the Associazione Amici di Media Duemila and the Osservatorio Tuttimedia, and the Department of Communication and Social Research of Rome’s University “La Sapienza”, who were organizing the official event for the centennial in Rome, under the fundamental guidance of Maria Pia Rossignaud) we were able to make it happen and everyone involved was really happy to include this experience in the official celebrations.

Renee Carmichael: I find the methodology behind this project really interesting. From what I understand it’s about going beyond the analogue vs. digital debate and really going in between and just experiencing and experimenting. Do you think this methodology is important to use in today’s world? How and why might this be so?

Salvatore and Oriana: We are living in a really complex scenario, complex, fast and ever changing. Digital technologies and networks are starting to pervade our analogue reality, transforming it and opening up entirely new possibilities. There are forms of (digital) interaction that are starting to be widely accessible from physical space. These forms of interaction are really peculiar as they allow for a transformation of (physical) reality, making it interactive, reinventing it, remixing it, and adding content to it. The world itself becomes a performance and a very specific form of performance: involving remixes, mashups, recontextualizations and reenactments as its main practices. This has drastic effects, not only as our reality multiplies and reshapes, but also attitudes, perceptions, skills, knowledge and approaches of the people involved change. In this process methodologies, practices and theories remix as well, bringing forth various possible scenarios, in which collaboration practices emerge as the only viable way to perform significant actions.