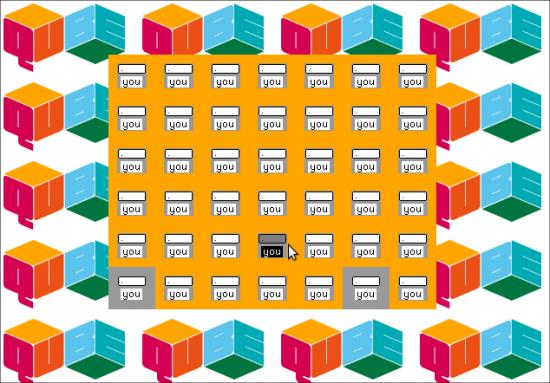

In the second part of classic videogames that have inspired contemporary artists, we take a closer look at a game that the Cubists probably would have worshiped. Tetris was created in 1984 and then released officially in 1985 by the Russian programmer Alexey Pajitnov. In Tetris you have to move and rotate seven different combinations of blocks as they fall into a well. The blocks are called tetrominos and are made of four squares. The goal is to fit the different geometric shapes so that as little empty space as possible remains in the bottom of the well. Tetris is a puzzle game for people who like compact living, and who see it as a sport to pack economically to the holiday.

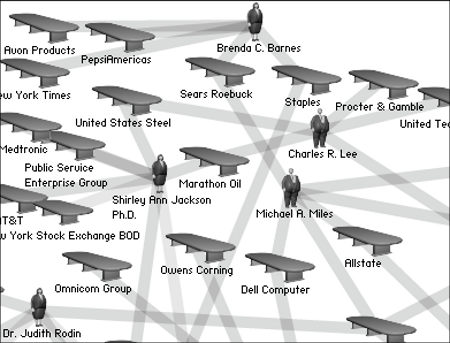

In contemporary art you can find three main approaches how artists have used Tetris. The Swedish artist Michael Johansson is a good example of the first approach. He has used the basic idea of Tetris to stack objects with different colors and shape. Johansson works with site-specific installations, in which he collects and stacks objects from the near surroundings in perfect symmetry with no spaces. The installations are called Tetris, which is fitting since they are strongly reminiscent of the game.

“For me creating works by stacking and organizing ordinary objects is very much about putting things we all recognize from a certain situation into a new context, and by this altering their meaning. And I think for me the most fascinating thing with the Tetris-effect is the fusion of two different worlds, that something you recognize from the world of the videogame merges into the real life as well, and makes you step out from your daily routine and look at things in a different way.” says Johansson in an interview at Gamescenes.org

Like many other classical videogames, Tetris has been used a lot in public spaces as in graffiti, mosaics and posters on facades and in subways etc. In Sydney, Australia, artists Ella Barclay, Adrianne Tasker, Ben Backhouse and Kelly Robson in 2008 at an exhibition at Gaffa Gallery created an installation where they placed giant illuminated Tetris Blocks in a narrow alley. It looked exactly as if the blocks had fallen from the sky, but the alley had been too narrow so the blocks were stuck halfway down.

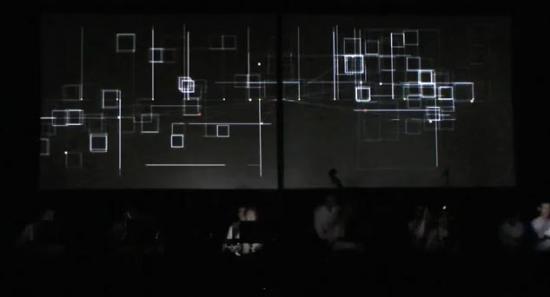

The second approach is to move Tetris out from the exhibition room into public spaces and sometimes also create interactive and social art. The artist group Blinkenlights, who are known for transforming large skyscrapers into interactive screens, on various occasions making it possible for the passing public by to play Pong or Tetris on a skyscraper using a mobile phone. In 2002 they made the installation Arcade, which turned one of the skyscrapers in the Bibliotheque Nationale de France in Paris to a giant screen showing various animations, where a passersby could also play arcade games like Tetris.

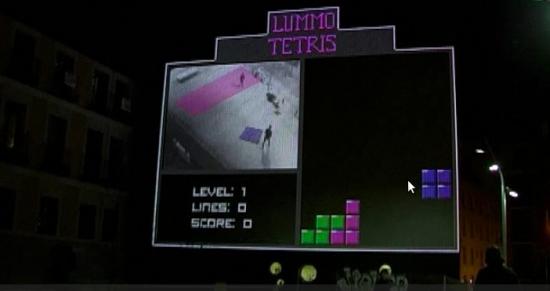

The artist group Lummo (Carles Gutierrez, Javier Lloret, Mar Canet & JordiPuig) created in Madrid in early 2010, a Tetris game in which four people have to cooperate to play it. The first step for the participations was to create the Tetris blocks and after that they had to work together to place on right position in the well which was projected on a wall. In Both cases, Blinkenlights and Lummo are creating public meeting places with social interaction where the videogame is used as an interface.

The third approach is changing the game itself and creates new versions of the game which discuss the game idea. The artist group version [url=http://www.tetris1d.org/]1d Tetris[/url], is a one-dimensional Tetris where the blocks consist of four vertical squares falling into a well that is just one block wide. Since the blocks always fill the well the players do not have to do anything to score points. The basic idea of the falling blocks still remains in the game, but in a one-dimensional world there is no longer any difficulty, the game is reduced to a very monotonous and predictable puzzle game.

In First Person Tetris the artist David Kraftsow combines the perspective from the popular first person shooter genre (used in war and action games) with the ordinary puzzle game. In Kraftsows variant you see the game from a first person perspective so when you spin the blocks, it is not the individual blocks that are spinning around but instead the whole screen. Just by using a new perspective in the game has Kraftsow created a whole new experience of Tetris. Mauro Ceolin, who has spent many years focusing on the modern emblems on the Internet. In works such as RGBTetris and RGBInvaders he replaces the game’s graphics with contemporary icons and logos. In RGBTetris the blocks that fall down the well are exchanged with logos from Camel, McDonalds, Nike and Mercedes.

The most interesting and most independent among the playable Tetris versions that I have found are made by the Swedish artist Ida Roden. In Composition Grid she has combined her interest in drawing with Tetris. The player can play a game and in the same time create a unique drawing by rotating and changing one of the 216 different creatures that Roden has created, with the Tetris blocks as model. The player can then choose to print out their own game plan with the artist’s signature, and in that way have a unique work of art in there possession.

Tetris, this two-dimensional version of Rubik’s Cube, seems to create a lot of room for artistic experimentation. It just needs some simple changes, or new perspectives, to create a new and interesting interpretations of the game.

Videogame appropriation in contemporary art: Pong. Part 1 by Mathias Jansson.

Some of these new Tetris games can be found at these addresses:

www.rgbproject.com/RGBtetris/RGBtetris.swf

www.tetris1d.org

www.firstpersontetris.com

www.idaroden.com/composition.html

Classic video games such as Pong, Tetris, Space Invaders, Pac Man and Super Mario have in the past decade inspired many artists in their work. The common link between all of these games is that they are very easy to learn and play. There is no need for manuals, just a few simple instructions on the screen. The graphics are simple, the colours few, the characters and style are pixelated. These games have influenced a whole generation and have over time become a part of our cultural heritage. Even today, these games still amuse and fascinate players and have also inspired various artists to use them in their art. In a series of articles, we will look at some classic games and give examples of how they have been used in art and what impact they have made on the art scene. First out is PONG.

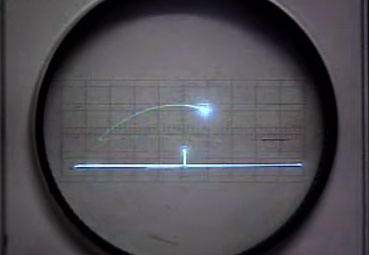

It was the American physicist William Higinbotham who in 1958 created what many consider to be the first computer game. The game was called “Tennis for Two” and was played on an oscilloscope with help of a simple analogue control.

Click here to view video on Youtube…

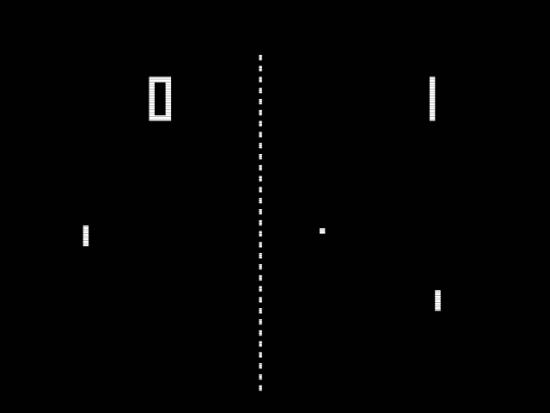

It took, however, until 1972, when the Atari Company, founded by Allan Alcorn and Nolan Bushnell, picked up the idea and created a commercial version and called it PONG, before the game became one of the first real big sellers for the computer games industry. PONG is a simple, minimalistic game that consists of two rectangles and a square, which symbolize two tennis racquets and a ball. You can either play against another opponent or against the computer. In this simplified version of tennis, the goal is to hit the ball so the opponent misses it.

PONG is probably the videogame that has inspired most artists over the past decade. When the Computer Games Museum in Berlin in 2007 organized a major exhibition entitled “pong.mythos” over 30 artists attended with works of art inspired by PONG. The catalogue explains why PONG fascinated so many artists: “No other video game has been the origin of artistic production quite as often as the simple black-and-white tennis game. In addition to its popularity, it seems to be this minimalism that especially appeals to artists, since the playing pattern is a virtual prototype of the essence of each and every communication situation: the ball as the smallest possible unit of information, oscillating between sender and receiver” (from the catalogue “pong.mythos” 2006).

The artist group /////////fur//// showed their “Pain Station” (2001) in which the player who missed the ball were punished with physical pain, a blow on the hand, heat or an electric shock. “Pain Station” connects the physical world with the virtual and the virtual player’s mistakes turn actual real pain.

The artist group Blinkenlights working in the urban environment was represented with a project that transformed a large office building at Berlin Alexanderplatz to a digital screen where passersby could play PONG on the facade with the help of their mobile phones. In the artists S. Hanig and G. Savicic’s work “BioPong” (2005) the ball was replaced with a living cockroach where the players would try to push the insect over to the other side. And in the group Time’s Up version “Sonic Body Pong” (2006) the ball in the game was only a sound which the players could hear in their headphones and with help of large green rectangles on their heads they would try to hit the sound from the ball.

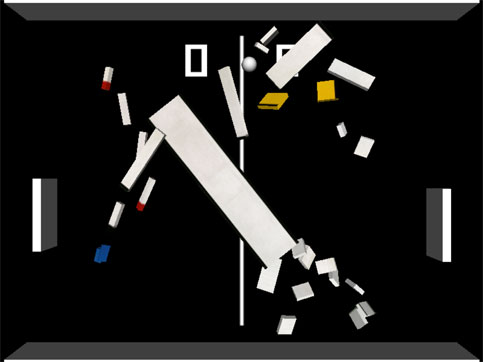

There are also many other examples that were not included in the exhibition “pong.mythos”. As early as 1999, the artist Natalie Bookchin made “The Intruder”, a work where PONG was one of 10 different videogames that she used to create an interactive artwork by Jorge Louis Borges short story “The Intruder”. The Danish artist Anders Visti mixed the game PONG with the art of Piet Mondrian in “PONGdrian v1.0” from 2007. The playing field in Vistis artwork reminiscent a painting by Mondrian but when the ball hits the fields it disturbs the lines and colour fields, and creating new opportunities and challenges for the player. Finally, I can mention the Swiss artist Guillaume Reymond, who has made a series of performances called “Game Over”. In a theatre auditorium, he creates animated sequences by using real people in colourful T-shirts, where each individual represents a square on a screen. By moving the people in the auditorium, he can create short video sequences, for example of PONG playing in the lounge.

The reason that PONG is so popular among artists is that it is one of the very first video games, and therefore there is a large identification factor and a strong relationships between the game, the player and the artwork. PONG is also one of the easiest games in terms of both appearance and to learn to play, which paradoxically makes it so easy to transform and use in different contexts. The phrase “less is more” seems in this case a good explanation why PONG has inspired so many artists in recent years.

Pong Mythos – http://pong-mythos.net/index.php?lg=en

Natahalie Bookchin – The Intruder http://bookchin.net/intruder/

Guillaume Reymond – Game Over http://www.notsonoisy.com/gameover/

Anders Visti – PONGdrian v1.0 http://www.andersvisti.com/arkiv_grafik/pongdrian.html

On October 10th, 2010, the Upstage Festival of Performance Art (101010) curated by Helen Varley Jamieson, Vicki Smith, and Dan Untitled ran for approximately twenty hours, the fourth such iteration of themed dates (last year ran on 090909.) 101010 showcased thirteen new cyber performances from Canada, USA, UK, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Austria, Serbia, Australia, and New Zealand, most lasting for twenty minutes. UpStage was host to ten real world viewing nodes in Calgary, New York, Nantes, Eindhoven, Oslo, Ljubljana, Pancevo, Vietnam, Auckland, and Wellington. Individuals could also tune in from the comforts of their own homes.

UpStage’s audience derives from anywhere one is capable of accessing a web page, and participation does not require the installation of any new software except the ubiquitous Flash Player plug-in. The application sits on a central server, is free and open source, and programmers can add new code and share improvements and new features. Written in Python, UpStage works with third-party applications. It provides a set of tools for logged in players to work with a variety of media in real time; graphics (still images and animations), video (live web cam feeds or prerecorded video), audio (text2speech synthesized speech or prerecorded audio), text and illustrations that are collaboratively manipulated to create an improvised or rehearsed event.

Performers, euphemistically referred to as “players”, show up in the “stage” or screen area as avatars with access to a variety of pre-created backgrounds and props. When the avatars speak their words appear on-screen as a cartoon-like bubble, and their speech is simultaneously rendered in the odd robotic text2speech function. The thirteen performances were grouped into four themed categories. Temporal explored sound and movement across time and networks. Trajectory examined the path of a moving object through space, and the arc where that object intersected with the story. Tendrils wove subtle thoughts and concepts, and Transgress went beyond limits to question, challenge, and provoke.

MIT Professor Sherry Turkel in her 1995 groundbreaking book Life On The Screen first codified the anonymous audience interaction. UpStage’s appeal is its live-time interactivity that emulates the anonymity of sites like Second Life, but also employs scripted dramas that let the audience (either all of the time, or at selected moments) jump into the story. It raises the question of the difference between “stage” acting in a traditional theater, and acting in front of a virtual audience, an issue bridged by maintaining traditional chat function.

Before a scheduled performance begins, one can congregate in a virtual foyer and facilitators use a megaphone to speak in synthesized robotic text2speech voices. A second screen tab hosts the site of the virtual performance area. Depending on whom Upstage is trying to connect with, the dialogue and effects can flow swiftly, or be disrupted.

I was able to view four performances over the span of two hours. “Plaice or Sole” by Francesco Buonaiuto, Mario Ferrigno, and Simona Cipollaro (Naples) contained graphic sexual content that was presented in a purposely immature style. At first it was annoying and boring, but afterwards I was informed that was the point – to emulate and call attention to the inane comments and dialog that occur in many on-line cybersex chat rooms. A crash during the site’s interaction was a deliberate simulation of a technical failure. As one person put it, “it forced you to become engaged in the text shift.”

Active Layers, is a virtual collective includes Cherry Truluck (UK), Liz Bryce (NZ), James Cunningham and Suzon Fuks (Australia). They combine theatre, dance, video and visual arts both digitally and conceptually to redefine the meaning of location and site. Their animation piece “Aquifer Fountain” focused on drought, water, flooding, and devastation, with mothers dreaming of lost babies. During the performance the actors participated from London, Kawerau and Milwaukee.

“Make Shift” is a work in progress by Paula Crutchlow (UK) and Helen Varley Jamieson (NZ/Germany). They used the Upstage audio-visual conferencing tools in two deliberate domestic spaces to link their cyberformances, thus creating a third discursive space. The discussions focused on the political aspects of domesticity such as “nesting, feeding and mobility,” and how this relates to the experience of globalization.

“MASS-MESS ” by Katarina DJ. Urosevic & Jelena Lalic (Serbia) ran both virtually and at the physical node at Galerija Elektrika in Pancevo. It was a study of structures, mass media and independence in the context of a hierarchy of information without a center playing out like a post-Soviet Politburo manifesto. “MASS-MESS” made it onto Serbian TV, as evinced by a subsequent newscast posted onto YouTube.

What is an experiment? I get the sense that many of monochrom’s projects seek to interface with the world (ahh, but what world might that be?) In a sense, I am curious about how you imagine the field, what objects you see upon it, what things call themselves objects but are perhaps only specters? How can non-existent artists save non-existent countries?

Yes, we love experiments. And we approach them like committing a crime: very, very carefully. Still, we know that there’s no perfect crime and we are going to make some mistakes. The main problem with our artistic and activist work is, and that might sound strange: subversion.

Only thirty years ago Western societies were still governed along the principles of the “disciplinary society”. The institutions of a disciplinary society are founded mainly on two devices that keep its subordinates where they are: control and punishment. Both are certainly effective, yet they produce at least an inner resistance, as well as the possibility to avoid either. It’s hard to monitor in absolute terms, and there are always ways of avoiding, if not “hacking” and ridiculing these mechanisms of control. Loop-holes will be identified and used.

The disciplinary society was one that created refractoriness; it revealed hierarchies and blatantly opposing classes of rulers and the ruled. These small acts of individual resistance also instigate models of theoretic and actual resistance on a grander scale.

The society of control has however shifted this device and transplanted it into the subjects themselves. As soon as control is collectively internalized, when control is part of the psychological apparatus and of thought, then we can speak of control in absolute terms. Not much can be done anymore, as no one is independent from, or outside of, control any longer.

We have to be aware of this change and have to analyze and adjust our attacking strategies. Companies like Nike already use Graffiti as a standard variety in their marketing campaigns and the first people who read Naomi Klein’s No Logo were marketing gurus who wanted to know what they shouldn’t do. We certainly can change the political economics of a society. And you can quote me on that. But we have to be precise about it. Just playing around might only make our actions end up as a funny 15-seconds-clip on CNN, and that would be useless. We have to understand cognitive capitalism or we will just be going round and round in the same old circles, as the history of guerrilla communication clearly shows.

How can we subvert a system that actually wants you to subvert it? You can only experiment. And fail.

Well, since beginnings are first (except of course when they aren’t) it would be interesting to hear a bit about the inception of monochrom back in 1993.

I was always interested in obscure crap, even as a kid. I loved science fact (Carl Sagan is still my only media idol) and science fiction, especially John Brunner and William Gibson. And I was always interested in the political dimension of near-future sci-fi. It’s hard to imagine, but I became a punk and antifascist because I devoured cyberpunk novels and watched stuff like Max Headroom. It was great dreaming of a jack in the back of your head, but the corpocratic, doomed world was nothing that I wanted to really happen. I joined the FidoNet data network when I was thirteen or fourteen, around 1988 or 1989. It was a wonderful way to get in contact with weirdos from all over the planet, collecting info and interesting mailing list threads, and slowly but surely my wish to start a publication grew. So monochrom started in the early 1990s as a print fanzine about cyber-topics, politics, bizarre art and covert culture.

What were the circumstances or impetus for Monochrom’s formation? How do you find the world around monochrom has changed since you began?

There was some stuff in the US of A, like Mondo2000… but it was all too hippie-ish, too liberal, indulging in what Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron later called the “Californian Ideology”. I wanted to share and propagate a leftist European perspective. As a member of several bulletin board systems I sent out mails to a couple of message boards, looking for collaborators, and Franky Ablinger replied in only two hours. And so the monochrom group, or better, “the monochrom culture,” was born. We published a couple of issues, low circulation, and – as the name suggests – we were barely able to finance the black and white xeroxes. But we kept working, creating our first internet site in early 1994.

In 1995 we decided that we didn’t want to constrain ourselves to just one media format (the “fanzine”). We knew that we wanted to create statements, create viral information. So a quest for the best “Weapon of Mass Distribution” started, a search for the best transportation mode for a certain politics of philosophical ideas. This was the Cambrian Explosion of monochrom. We wanted to experiment, try stuff, find new forms of telling our stories. But, to be clear, it was (and still is) not about keeping the pace, of staying up-to-date, or (even worse) staying “fresh”. The emergence of new media (and therefore artistic) formats is certainly interesting. But etching information into copper plates is just as exciting. We think that the perpetual return of ‘the new’, to cite Walter Benjamin, is nothing to write home about – except perhaps for the slave-drivers in the fashion industry. We’ve never been interested in the new just in itself, but in the accidental occurrence. In the moment where things don’t tally, where productive confusion arises. That’s why in the final analysis, although we’ve laughed a lot with Stewart Home, we even reject the meta-criticism of innovation-fixation articulated in ‘neoism’. The new sorts itself out when it lands in the museum. Finito.

Some guy once called us ‘context hackers’ because we carefully choose the environment we want to work in and then try to short-circuit it. Some projects definitely work better as a short film or installation or puppet theatre or robot or performance, some should simply be presented as ASCII files … and some are the right stuff for a musical. It just depends.

What happened to the fanzine?

Well, it’s unbelievable, but we still publish it, but not on a regular basis. We decided to switch to a “phatzine format” or call it a “magazine object”. It’s huge. The last one was released in March 2010… it’s #26-34, an accumulation of 500 pages and 2 kilograms. It can break your toe if you drop it! It’s still a good mix of science, DIY, theory, cultural studies and the archeology of pop culture in everyday life. With a great deal of forced discontinuity, a cohesive potpourri of digital and analog covert culture is pressed between the covers. We try to offer an un-nostalgic amalgam of 125 years of Western counterculture – locked, aimed and ready to fire at the present. Like a Sears catalog of subjective and objective irreconcilability – the Godzilla version of the conventional coffee table book.

What are your thoughts on contemporary zoology?

I always loved the grand dichotomies of life. Dogs and cats. Cats and mice. Like Tom and Jerry. But as someone who grew up in Central Europe I never understood how a mouse can live inside a wall. Walls are made of bricks! They are not hollow. Way later I came to understand when I learned that US-American houses are just made of wood, and their walls are really hollow.

Have you ever been walking down the street, mobile phone in hand, and thought of throwing it on the cement, giving it a few good dancing stomps and darting off?

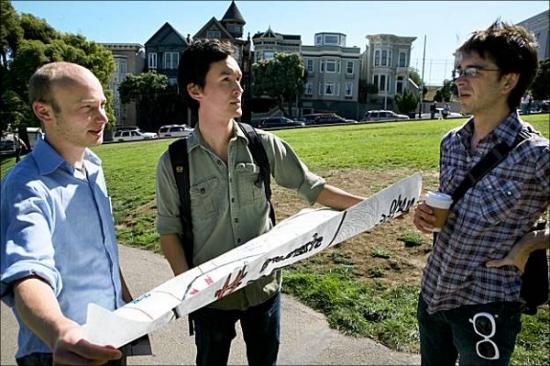

Yes. Even better. We did a workshop called “Experience the Experience of Catapulting Wireless Devices”. The catapult is one of the oldest machines in the history of technology. It is no coincidence that we instigated a creative return. The knife edge of technology hype is sharp, most of all on the West Coast of the United States. Thus we initiated a competition. We invited interested persons to design and build a catapult capable of hurling a cell phone or a PDA unit the greatest possible distance. In order to ensure that no participant had any unfair advantage, we provided a specifications list regarding materials (e.g. metal) that were not to be used and other limitations (e.g. size and weight). And we only tolerated WIRED Magazines as counterweights. That was fitting.

Were you in Berlin when the wall was taken down?

I was asleep, at home. But I always wonder what the official web site of the GDR would look like if they were still around in 2010. Would they use Flash? Or HTML5?

Fanta or Coke?

Fanta originated when a trading ban was placed on Nazi Germany by the Allies during World War II. Coca-Cola GmbH, therefore was not able to import the syrup needed to produce Coca-Cola in Germany. As a result the company decided to create a new product for the Nazi market, using only ingredients available in Germany at the time, including whey and (yummy) pomace. They called it Fanta. So I guess, what’s the difference?

Read part 1 of this interview:

http://www.furtherfield.org/interviews/interview-johannes-grenzfurthner-monochrom-part-1

Read part 2 of this interview:

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/interview-johannes-grenzfurthner-monochrom-part-2

The Zero Dollar Laptop Workshop programme has been developed and delivered through partnership between Furtherfield and Access Space and aims to change attitudes to technology. It does this by recycling hardware, deploying Free and Open Source Software (FOSS), sharing skills and working together to create rich media content.

This project has provided a useful basis for thinking about how art might be able to create change through learning and education that relates to technology.

This question becomes especially relevant in the context of current, global economic and ecological collapse.

So first let’s start by thinking about what art and technology and social change have got to do with each other?

It does depend on how you view art. At Furtherfield we don’t accept the mainstream view of art as a marginal interest. The expanded, connected and networked art forms that we choose to work with cannot be separated from life so easily.

They engage the people who encounter them with different kinds of aesthetic, ethical and philosophical experiences – often in places not easily recognisable as art-spaces, often in technologically enabled spaces because this is where life takes place for so many people.

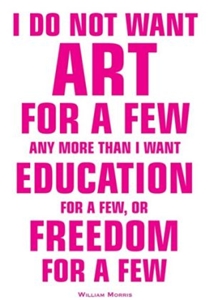

For all kinds of reasons (to do with our education and class structures), in the UK the dominant view is that ‘great’ art is separate and distant from the rest of life and therefore of marginal relevance to society and most people, or to quote Heath Bunting ‘Most art means nothing to most people’.

It is regarded as: elite/intellectual, historical/heritage, commodity, the work of charlatans etc.

Sometimes art is regarded perhaps more positively, as a diversion or a hobby; more positive from our point of view because people make art their own, share it and incorporate it into their own lives on their own terms.

Don’t just Do It Yourself, Do It With Others (DIWO!)

Furtherfield got started in the context of the discourse-smothering London Brit Art gallery scene in the mid-90s, when access to established galleries was carefully guarded. Meanwhile the Internet, an open public space of unlimited dimensions, was relatively sparsely populated at two extremes by corporate marketing departments and pet owners. The Internet also offered a free playground for early net artists.

Since then Furtherfield has co-constructed platforms and processes (online and in physical spaces) with a network of other artists, hackers, gamers, programmers, thinkers and curators to support collaboration and engagement between artists, participants and audiences worldwide.

Informed by ‘open and free’ philosophies and practices of peer-to-peer cultural development and moving on from the DIY (Do It Yourself) approach of the 1990s artist-hackers that fed on the Modernist understanding of the individual artistic genius, we have moved towards more collaborative processes that we call DIWO (Do It With Others) and that explore different ways of creating shared visions.

For us taking a grassroots approach in art means that we pay attention to the everyday lives of the people we work with, to create and shape the platforms that we need. This is not a hippy dream. Rather, it provides a way to develop robust and healthy ways for diverse people and interests to interact and co-exist for mutual benefit.

Since 2008 Furtherfield and Access Space have worked in partnership on the Zero Dollar Laptop project, to support cooperation in creativity, technical learning and environmental awareness. One side-effect of techno-consumerism is that we dump tonnes of UK electronic waste in the developing world each year.[2]

This project, inspired by James Wallbank’s Zero Dollar Laptop Manifesto, aims to change the way we think about technology by a shift of emphasis: from high-status consumer technologies to customised tools-for-the-job and smart, connected users.

Our organisations have worked together with participants to develop resources and pilot workshops that aim to eventually bring back into use (or save from toxic waste dumps) millions of redundant laptops currently gathering dust on shelves in homes and offices across Britain; putting them in the hands of the people who are best placed to make use of them, to benefit from a collaborative approach to learning and to connect with new knowledge networks in the process.

This project has its basis in grassroots, critical practice at the intersection of art, technology and social change.

The first pilot of Zero Dollar Laptop workshops kicked off at the Bridge Resource Centre in West London in January 2010 with clients of St Mungo’s Charity for Homeless People. [3]

In our experience, a much more diverse group of people are able to enjoy and benefit from technical projects when the projects acknowledge and incorporate ethical, philosophical and aesthetic questions as part of the mix.

People who might not initially identify themselves as ‘techy’ stay engaged with complex technical learning processes by focusing on the learning that is meaningful for them and sharing it with others.

In the case of Zero Dollar Laptop workshops this can range from creating a profile image for Facebook to writing a blog post to lobby against government cuts in public services, or creating a desktop background or a new startup-sound to customise their own laptop.

The meaning and function of work is often conveyed by the construction of a context (a place, a set of tools, an aesthetic, a set of relationships) or a hack or remix of an existing context.

With participatory or collaborative artworks the context in which people engage with the work is a part of the work.

So the role of the artist today has to be to push back at existing infrastructures, claim agency and share the tools with others to reclaim, shape and hack these contexts in which culture is created.

We believe that through creative and critical engagement with practices in art and technology people become active co-creators of their cultures and societies.

And as James Wallbank notes, ‘the best artworks are those that create artists’.

Originally commissioned by Axisweb.

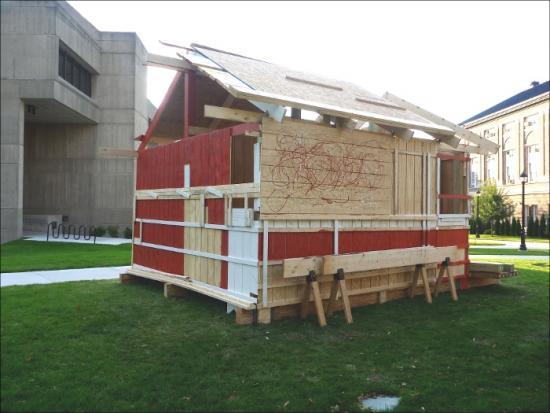

All Raise This Barn – a group-assembled public building and/or sculpture.

“Artists MTAA are conducting an old-fashioned barn-raising using high-tech techniques. The general public group-decides design, architectural, structural and aesthetic choices using a commercially-available barn-making kit as the starting point.” -MTAA

Eric Dymond: Could you give me a brief history of MTAA?

T.Whid: Mike Sarff (M.River of MTAA) and I met in college at the Columbus College of Art & Design in Columbus, OH. We both separately moved to NYC in 1992 and started collaborating as MTAA in 1996 first on paintings and then moving on to public happenings and web/net art. We’ve been collaborating since, showing our work via our websites at mteww.com and mtaa.net. We’ve earned grants and commissions from Creative Capital, Rhizome.org and SFMOMA and shown at the New Museum, 01SJ Biennial, the Whitney Museum and Postmasters Gallery.

ED: The All Raise This Barn project uses one community to design and another to construct. Barn raising is itself a communal activity, drawing out the best in people and providing a place of sustenance for the Barn owner. How did you come to use a Barn Raising as the central performance subject?

M.River: From the start, Tim and I have been interested in how groups and individuals communicate. How do we speak to each other? What rules do we use? How does communication fail or how can it be disrupted? What is the desire that engines (TW: controls?) all of this – and so on. This interest in exchange is what attracted us to the Internet as a site for art in the beginning.

Along with communication as text, speech or image, we like to use group-building as a method for working with non-verbal communication. We’ve built robot costumes, car models, aliens and snowmen with large and small groups. It’s a type of building that is intuitive and open to creative improvisation. This kind of intuitive building is heightened by placing a time constraint on the performance. In the end it’s not about the end object, which we always seem to like, but more about the group activity.

So, at some point we began to think how large can we do this? A barn-raising seemed like the next level. It’s bigger than human scale and contains a history of group-building. Barns also have a history of being social spaces. Your home is your world but the barn is your dance hall.

ED: Did you envision it as a community event from the beginning?

MR: Yes. An online community, a physical community and a community that overlaps the two.

ED: It’s a hybrid work that draws upon some important conceptual precedents. The instructional aspect takes Lewitt and turns the strict instructions he uses upside down by allowing online decisions to drive the design. Did you find the responses to the online polling surprising?

MR: Yes and no. Like the other vote works we have produced, Tim and I set up how the polls are worded and run. So, even though we try to keep the process as open as possible, the nature of how people interact is somewhat fenced in. Even with a fence, people will find a way to move in strange directions or break the fence. It’s not that we think of the surprising answers as the goal of the work, but it is an important part of the process.

ED: There is also the performance aspect which I find exciting. The performance from both events are well documented. Were there any concerns regarding the transfer of the polls instructions to physical space?

MR: We had the good fortune of doing the work in two sections. When Steve Dietz commissioned ARTBarn (West) for the 01SJ Out of the Garage exhibition, we spoke about the sculpture as a working prototype for how a large pile of lumber could be group-assembled in a day with direction from Internet polling. From this prototype we then had a model for how to go about ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC.

Tim and I had a few loose ground rules on how to approach the translation. One was that we would leave some things open to the interpretation of the crew. Another was that both Tim and I had our favorite poll questions that we tended to focus on. It was impossible to do everything as some polls conflicted with other but some details liked ghosts, dripped paint and open walls seemed to call out to us.

Kathleen Forde, who commissioned ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC, spoke about these details as where the work became more than the sculpture. The small details held the whole process – material, design polls, and performance together.

ED: I think this comment on the details is right. On first glance there is a fun, open appeal to the work. But when you look at the overall project and how the different phases are tied together it becomes really complicated in the mind of the spectator. There are also different definitions of spectator in this work. The spectator who answers the poll, the spectator on the net who is grazing through the documentation, the ones who engage in the physical construction and those who witness the completed barn. It’s not a simple piece when we perform a detailed overview. Did you think about the various types of spectator that would spin off the project? Were the possible roles for the spectator considered after the fact or were they part of the planned concept?

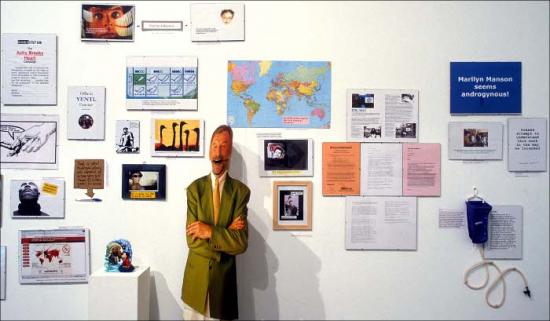

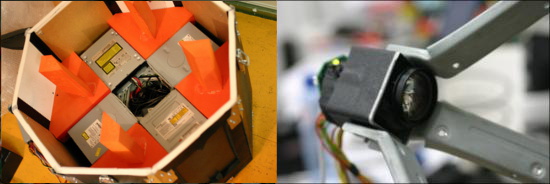

MR: The “ideal spectator” thought first came up for us in a project called Endnode (aka Printer Tree) in 2002. For this work, we built a large plywood Franken-tree with a set of printers in the branches and a computer in the trunk. We then built a list-serve for the tree as well as subscribed it to a few list-serves. When people communicated with the tree, the text was printed out in the exhibition space. At first we talked about the ideal viewer as one who communicated with it online and then saw that communication in the physical space or vice versa.

Now I feel that the ideal spectator hierarchy is not as important and possibly limiting. Each experience should be whole as well as point to the larger aspects of the work. People can come in and out of the work on different levels. You voted. You followed the performance documentation. Are you missing an experience if you did not build with us or see the results? Yes, an activity is missed. Can you experience that activity thorough documentation. Somewhat. Are you going to have a better understanding of the work. Probably not. Even for me, some aspect of the work will not be experienced. In Troy, they are programing it as a meeting place now that is it is built.. When they are done with it, they will dismantle it and rebuild it elsewhere as a work space.

I say all this even though it is interesting to me that a work can move in and out of levels of viewer experience. I’m not sure as to the draw of it yet but I do not feel it is about an cumulative effect.

TW: Since Endnode I’ve always liked the idea of an art work that exists in multiple (but overlapping) spaces with multiple (but overlapping) audiences. With our pieces Endnode, ARTBarn and Automatic For The People: () there are 3 distinct (but overlapping) audiences: the online audience, the audience in the physical space and the (select few member) audience that experiences the entire thing.

ED: It’s that opening of possibilities that makes this ultimately a networked piece on many different levels. I find the idea of two barns, a few thousand miles apart yet linked by common purpose really intriguing. I’m talking about the whole set of experiences, not just the physical space of the barn. There’s a collapse of Geographic distance for the community and a richer experience because of that. Was the project conceived as two distinct locations or was that a fortunate turn of events?

MR: Fortune. Kathleen Forde, commissioned ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC then Steve Dietz commissioned the beta version for the 01SJ “Out of the Garage ” exhibition. Everyone liked the idea of the work arching across time and location. We all also liked the idea that the materials would be reclaimed after it stopped being a sculpture. For me, the reclaimation of the materials to use for a functional structure is the final step of the work.

ED: As the final step, the reclamation removes the common space where the community currently shares the sculpture. Does this mean you are going to use the online documentation as the artifact, coming full circle to where the piece began? Is it important to you that the communal memory will share this role?

TW: Yes, the documentation is the artifact. The barn structure or sculpture itself had been conceived as being physically temporary from the beginning.

ED: Thanks to both of you for your time and for this work.

In 2002, when Monochrom was invited to act as the representative of Austria at the Sao Paulo Biennial, instead of going as yourselves, you sent Georg Paul Thomann, one of the country’s most prominent avant guard artists, and also a complete fabrication.

Yes, we were asked to represent the Republic of Austria at the Sao Paulo Art Biennial, Sao Paulo (Brazil) in 2002. However, the political climate in Austria (at that time, the center-right People’s Party had recently formed a coalition with Jorg Haider’s radical-right Austrian Freedom Party) gave us concerns about acting as wholehearted representatives of our bloody nation. We dealt with the conundrum by creating the persona of Georg P. Thomann, an irascible, controversial (and completely fictitious) artist of longstanding fame and renown. Through the implementation of this ironic mechanism – even the catalogue included the biography of the non-existent artist – we tried to solve with pure fiction the philosophical and bureaucratic dilemma attached to the system of representation.

It gave me something of a hearty guffaw to hear about how you and your fellows, manning the Austria country booth as the artist’s technical support staff – the lowliest of low in the art world hierarchy – went about revealing the fictitious nature of the artist.

Yes, we turned the tables. When members of the administration, journalists, or curators asked about the whereabouts of Thomann, our irritated answer was that he hadn’t cared to show up so far, and that he hadn’t helped with anything, because he was supposedly watching porn in his hotel room all day, while we – the members of his technical crew – didn’t care about that bullshit at all. But we informed other technical support teams about the basic idea of the project. They were also given detailed information about Thomann’s non-existence but we did not give them any hierarchic directives about what to do with their knowledge but left it up to them if they wanted to reveal the fake or keep spinning the story. Most people enjoyed doing the latter and they also kept telling different versions of the heard information until finally a bubbling geyser kept erupting in various ways and constantly led to new outbreaks of tittle-tattle.

What happened next, as I heard you describe it, was that “bubbles and bubbles of rumors” began to form around the expansive floor of the biennial. I found this moment in the arc of the project to be particularly interesting and was hoping you could perhaps share some of your thoughts and recollections.

Let’s give you a brief summary of the background. The basic principles of an art-super-structure like a Biennial is simple: lots of little white boxes in which art was set up – and little artists, spreading business cards like prayers. There is a nice German term: “die Warenformigkeit des Kunstlers” (“the commodity value of the artist”). We hardly had any contact with other artists… and that was bad. They came from more than 80 different countries, but they were hiding in their white boxes. Everyone was busy building his or her own little world. Then, during the final setup phase we found out about an incident, which took place in our neighborhood through a copied note.

One year before the Biennial, Chien-Chi Chang had been invited to be the official representative of Taiwan at the Biennial. But then, three days before the opening, his caption – adhesive letters – had been removed from his cube virtually over night. ‘Taiwan’ was replaced with ‘Museum of Fine Arts Taipeh.’ But to Chien-Chi Chang the status as an official representative of Taiwan was very important, because his photography artwork dealt directly with the inhumane psychiatric system in Taiwan.

Chien-Chi was trying to get in contact with the Biennial administration and the chief curator (the German Alfons Hug), but didn’t succeed. Communication was refused. After that he decided to write an open letter, but the creative inhabitants of all the little white art-combs didn’t seem too interested in the artist’s chagrin, who by now wanted to leave the Biennial out of protest.

We were interested in the situation and did some research. We found out that the Chinese delegation had threatened to withdraw their contribution and to cause massive diplomatic problems. To them, Taiwan was clearly not an independent country (c/f ‘One China Policy’) and they put pressure on the Biennial management to get that message out. The management did not make this international scandal public and it was quite obvious why.

monochrom decided to show solidarity with Chien-Chi. We wanted to set an example and show that artists do not necessarily have to internalize the fragmentation and isolation that is being imposed upon them by the structure of the art market, the exhibition business, as well as the economy containing them. For us, though, this is not about taking a stand for either the westernized-economical imperialism represented by Taiwan or for China’s old-school Stalinist imperialism. This is about integrity and solidarity, values that we chose to express through a collaborative act. Together with other artists from various countries we launched a solidarity campaign: we took off some adhesive letters of each collaborating country’s signature and donated them to Chien-Chi Chang. monochrom sponsored the ‘t’ of Austria, while the Canadians donated one of their three as. The other participating artists were from Croatia, Singapore, Puerto Rico and Panama. A lot of artists and curators from other countries refused to support the campaign for fear of – as they would call it – “negative consequences.” WTF? But at least some of the artists were pulled out of their self-referential and insular national representation cubes which, in themselves, so rigorously symbolized the artists’ work and his or her persona as commodities.

After some time we managed to attach a trashy, yet legible ‘Taiwan’ to the outside wall of Chien-Chi Chan’s cube. Numerous journalists took notice of the campaign and Chien-Chi opened his exhibition in front of a cheering audience. Some days later, we found out that Chinese and Taiwanese newspapers massively covered the campaign. One Taiwanese paper used the headline “Austrian artist Georg Paul Thomann saves ‘Taiwan’.” In other words, a non-existing artist saved a country pressed into non-visibility. Who said that postmodernism can’t be radical?

What was it like – even from a kind of phenomenological sense – to be in the midst of this bubbling, to experience the formation of a scandal from its very embryonic moments? Is there something in the interiority of situations like this that you see as essential to the creation of new kinds of solidarity?

First we would have to define what “new kinds of solidarity” mean. What would be the ‘new’ part of it? Does it go beyond old and traditional forms of solidarity? And why should it? I think that classic forms of solidarity were carried out by political groups or other collective entities. They tried to express their (let’s label it as) “old-school solidarity” by pointing their collective fingers at someone who they thought were mistreated: “Look, look this human being is being oppressed!” And they always did it “in the name of something”. Old-school solidarity was one more frickin’ medium that people used to get a message across. Thus it was always part of the realm of representation. Your act of solidarity represents the one you show solidarity with, but your act is also advertisement for yourself, your cause and the (political) identity you wish to construct. Politics is always drama. Best example for this would be the “supporters of Palestine”. There are tons of ethnic groups on this rusty little planet who have to suffer under worse conditions. But nobody seems to be interested in showing solidarity with them. Where are Henning Mankell and Noam Chomsky when you really need them? Involved in some stupid fast-food anti-imperialism. We have to understand that the “object of solidarity” is something you pick for a reason… and most of the time it’s to feel good as a group and to impress your peers. But that has nothing to do with factual, non-reductionist political analysis. Collective entities define themselves through acts of representation and this representation is comparable to the construction of national pride or patriarchal family structures and values. Solidarity can be read as an act of defining identities. And that can be very dangerous, because old school solidarity always wants to be “right”. You are always “the good one” supporting the poor bastards. Smash dichotomies!

What we experienced at the Biennial of Sao Paulo back in the spring of 2002 was a very non-collective act. We were no real group, no leaflets, we had no common agenda, we were a psycho-geographic swarm. There was no basis for acting or speaking as a collective and there was no need to bundle our powers or form an identity. Yes, we tried to recruit other artists to join in our little act of solidarity. But it was no protest, we didn’t protest a certain political agenda because we didn’t want to end up in the old black and white world that, for example, all the apeshit Pro-Tibet supporters live in. Bah! Their ugly flags! Their patriarchal projections! Richard Gere! Yuck! So it was a kind of “free flowing solidarity”, not to be abused to form a political movement or statement. The only form of identity that was formed was the simple idea that even bourgeois artists can decide whether they want to be part of the Biennial and its stupid rules or whether they want to be part of action and fun.

To make it short: we are interested in micro-political solidarity, temporary solidarity that can’t fossilize. Solidarity is important if it can evolve and vanish within a short span of time and all that’s left is rumors and vague commemorations. Let’s call it a process of counteracting – that might be well-known in the field of the urban guerrilla but that so rarely pops up at art shows.

Read Part 1 of the Interview

http://www.furtherfield.org/interviews/interview-johannes-grenzfurthner-monochrom-part-1

Read Part 3 of the Interview

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/interview-johannes-grenzfurthner-monochrom-part-3

Between July 27th and August 29th, 2010, the eleventh edition of the FILE festival is taking place in Sao Paulo (Brazil), at several locations along the popular Paulista Avenue. After a decade of existence, this veteran festival, which spreads over several cities in Brazil (including Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre) as well as other international locations, has introduced for the first time its own award: the FILE PRIX LUX. With a total amount of approximately 120,000 euros, distributed in three categories, the prize is unprecedented in the continent and has received, on this first edition, 1,235 registrations from 44 countries.

Yet this award is not the only remarkable aspect of this year’s festival, which stands out for being particularly accessible to the general public. On the one hand, the exhibitions, performances and workshops as well as the symposium have no entrance fees, and therefore there have been many visitors, most of all young people who line up every day to experience the interactive installations at the FIESP-Ruth Cardoso Cultural Centre. On the other hand, the festival organizers, Ricardo Barreto and Paula Perissinotto, have developed this year a project that takes digital art to the Paulista Avenue by placing several interactive artworks at different locations in the public space. Finally, even the FILE PRIX LUX has been open to the interaction with the public by introducing a popular vote category and an online voting system which was accessible between May and June. This openness sets a good example of how media art festivals can engage the general public to approach this somewhat ignored form of art.

In general terms, the award categories at media art festivals have been subject to change as the creative uses of technology evolved during the last decades. The FILE PRIX LUX has the advantage of being created at a time in which it can be relatively safe to set up a few broad categories that cover most of the forms of combining art and technology. Only three categories have been established: Interactive Art (which usually refers to objects and installations that respond to inputs from the viewer/s), Digital Language (related to the festival’s title and which embraces any artwork that deals with language, narrative, code or text in a generative or interactive manner) and Electronic Sonority (the category assigned to any artwork in which the production or manipulation of sound is a key element). These three categories prove to be comprehensive, as shown by the diversity of the projects distinguished with a prize or an honorary mention: immersive interactive installations, musical performances, urban interventions, bioart pieces, a collectively created machinima movie and even an iPhone app are among this year’s FILE PRIX LUX awardees.

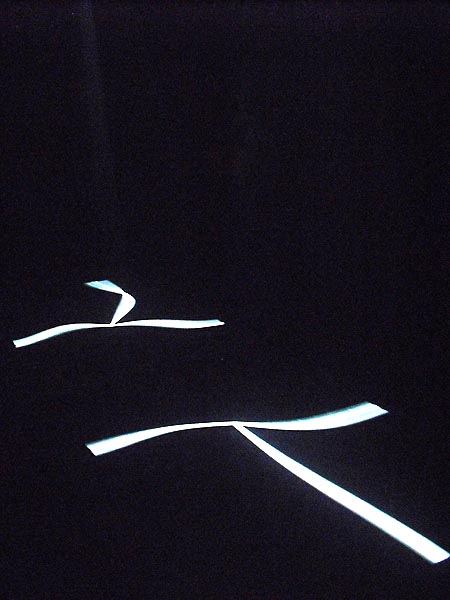

In the Interactive Art category, the winners are Ernesto Klar for Relational Lights (1st prize) and Kurt Henschläger for Zee (2nd prize). Both present immersive environments in which light and space are key elements, although the interaction is totally different. Klar’s work invites the viewer to interact with two projected geometric drawings inspired by the work of Lygia Clark. In a hazy dark room, the viewer sees two T-shaped projections of white light on the ground, which form a three-dimensional space which reacts to the visitor’s presence. The interaction is playful and really beautiful in its simplicity, whilst also limited in time: after a few minutes, the projections suddenly stop reacting to the user’s movements and reconfigure themselves in a new shape. This abrupt interruption is consciously introduced by the artist in order to remind the viewer that the artwork has a life of its own. In contrast, Henschläger’s Zee takes place mostly in the mind of an audience exposed to an overdose of audiovisual stimuli in a foggy room. Continuing the experience of his acclaimed performance FEED, this time the artist allows the viewer to walk around the space and have a more meditative sensory experience.

The Electronic Sonority category has brought together several outstanding works, among which Jaime E. Oliver’s Silent Percussion Project and TERMINALBEACH’s Heartchamber Orchestra have been distinguished with the 1st and 2nd prize, respectively. In both projects the human body is incorporated in a novel form in the creation of music, the sound being produced, moreover, not simply by direct inputs but by complex interactions in a constant flow of data. Oliver’s instruments convert the shapes created by the performer’s hands into streams of data that generate, in turn, different sounds. These sounds are not always the same, as could be the case in a traditional instrument, but are changed by the variables established in previous interactions. Thus, Oliver does not simply create a new form of interacting with an instrument but rather a new form of creating music. In a similar way, the [i]Heartchamber Orchestra[/i] project developed by TERMINALBEACH (Erich Berger and Peter Votava) explores a form of creating music based on a feedback loop in which the performers are writing and following the score at the same time. As the artists state, in their project “the music literally comes from the heart”: a network of 12 independent sensors record the heartbeats of the musicians in an orchestra and sends the data to a software that generates a musical score in real time. The musicians play the score as it is displayed on the laptops in front of them, while their heartbeats set the notes in a continuous cycle in which music and performer constantly influence each other.

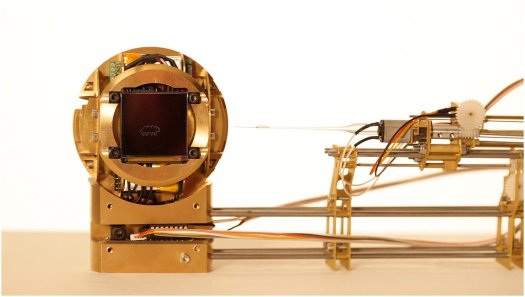

Digital Language is certainly the broadest category of this FILE PRIX LUX, its awardees being quite dissimilar in the formats they use and the objectives of their respective projects. The organizers define this category as including “all research and experiments in the ambit of the multiple disciplines that use digital media”, and the winners exemplify how diverse these disciplines can be. The 1st prize winner, Tardigotchi by the artists collective SWAMP (Douglas Easterly, Matt Kenyon and Tiago Rorke) is a bioart project that sets a critical comparison between artificial and real life. A nicely designed, steam punk-inspired device hosts, on the one hand, a tardigrade, a microorganism measuring half a millimeter in length, along with a robot arm that injects a substance that feeds the creature and a heating lamp that provides warmth. On the other hand, a digital display shows the virtual avatar of this tardigrade, with which the user can interact. Humorously referencing the popular Tamagotchi toy, the artists create a link between the avatar and the real creature: when the user presses the button to feed the avatar, the device inserts real food in the environment of the tardigrade; when an email is sent to the digital creature, a heating lamp gives warmth to the microorganism. Thus, interacting with the virtual pet has consequences in a real living being. This brings our attention into what we can consider alive and how we emotionally attach to artificial creatures while at the same time we undervalue the existence of other living beings. On a different approach, the 2nd prize winner, Hi! A Real Human Interface, by the collective Multitouch Barcelona (Dani Armengol, Roger Pujol, Xavier Vilar and Pol Pla), proposes a more human relationship with technology. A video presents the concept developed by this interaction design group of a different GUI in which a real person is displayed as impersonating the computer. Common interface elements are replaced by handmade physical objects which remind the aesthetics of a video by Michel Gondry. The result is a playful form of interaction in which simple operations such as checking email or upgrading the operating system are shown as actions carried on with real objects by a person inside a box. The proposal is engaging and certainly sets a departure from the old desktop concept, yet it remains unsure to what extend this type of interaction can be applied in a real operating system.

The works that obtained a Vesper statuette (symbol of the FILE PRIX LUX award) along with the also outstanding Honorary Mentions are exhibited at the FIESP-Ruth Cardoso Cultural Centre in a group show that also includes FILE Media Art, a selection of more than 70 works that can be accessed on several computers, as well as a selection of videogames and machinima films. The exhibition is thus richer in content than it would seem at first sight, as the space is divided in numerous sections that conceal several installations which demand (as usual) almost total obscurity. The artworks are well presented, although at times the sound from one installation invades the others, and there are no wall labels that inform the viewer about the concept of the piece or the way to interact with it. The latter, much-discussed issue is quite important, since the info-trainers cannot explain the artworks to every visitor, and quite often this entails that some people may not interact with the pieces or worse, start smashing buttons or interfering projections blindly in the hope of modifying them. Despite this fact, the exhibition has proven to be very successful during the first week of the festival, with a steady flow of visitors who showed a profound interest in the artworks.

A part of the exhibition is devoted to the FILE MACHINIMA section, curated by Fernanda Alburquerque, who selected over 40 works. Among these is the award winner in the Popular Vote category, War of Internet Addiction, by Corndog and the Oil Tiger Machinima Team from China, a 64-minute movie collectively created by players in the MMORPG War of Warcraft. More than mere entertainment, this film has been created as a form of protest against the Chinese authorities’ attempt to control the access and commercial benefits derived from the WoW game, which is extremely popular in the country. The film has had 10 million views since January 2010 and despite being available only in Chinese, it has been the favorite work of those who participated in the online voting system of the FILE PRIX LUX. Besides this feature film, other short films explore the possibilities of building narratives in virtual environments such as Second Life and videogames such as Half Life 2, Eve Online or Shadow of the Colossus.

In addition to the main exhibition, the FIESP Cultural Centre hosts a series of performances and screenings. Under the title Hypersonica, the festival presented a series of digital music performances, among which where the two winners of the FILE PRIX LUX in the Electronic Sonority category. FILE DOCUMENTA, curated by Eric Marke, offers in its 5th edition a selection of “rare and new” documentary films, among which Andreas Johnsen’s Good Copy Bad Copy, an interesting exploration of the conflicts between remix artists and copyright owners, or Robert Baca’s Welcome to Macintosh, which records the first years of the history of Apple Computers.

The symposium, hosted by the Instituto Cervantes in Sao Paulo, gathered several experts and artists who presented their explorations in the theory and practice of media art. Among the most interesting contributions were the presentation of Prof. Espen Aarseth on the aesthetics of ludo-narrative software, and the colloquy of South American digital art, in which Raquel Renno (Brazil), Jorge Hernandez, Ricardo Vega (Chile) and Vicky Messi (Argentina) discussed the current developments in the media art scene in the South Cone.

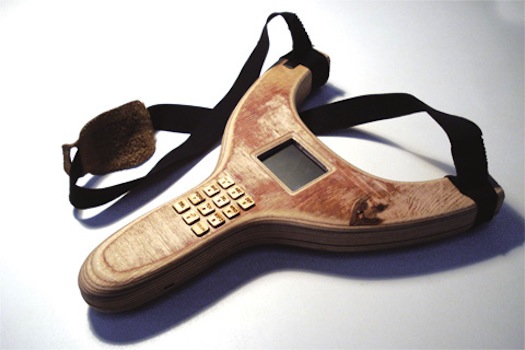

Alongside the FILE PRIX LUX, the most outstanding feature of the present edition of the festival is FILE PAI (Paulista Avenida Interactiva), which takes several interactive artworks to the public spaces in the Paulista Avenue. Interactive art offers the possibility of bringing art to the public space in a more efficient and dynamic form than what is usually known as “public art”. As Ricardo Barreto states: “the public environment is not something empty, aseptic and dead, as is the old white cube; on the contrary, it is an environment teeming with life, with multiple interests and multiple behaviors”. Interactive art integrates itself into this environment and is much more apt to relate to a public that is now willing to take an active role. The organizers of the FILE festival have distributed twelve interactive artworks along the Paulista Avenue, at subway stations, inside shopping malls, and even in a bus. The selected artworks include, among others, videogames such as Patrick Smith’s Windosill or the celebrated games of That Game Company, Flower and Flow; VR/Urban’s SMSlingshot, an urban intervention project that allows users to write a message in a custom-made slingshot that incorporates a screen and a keyboard and then send the message to a wall, where it is displayed as a virtual graffiti; Karolina Sobecka’s Sniff, an interactive projection in which a virtual dog reacts to the presence of passersby; the installations of Rejane Cantoni and Leonardo Crescenti Piso and Infinito ao Cubo, which attracted a large number of people, and the sound piece Omnibusonia Paulista by Vanderlei Lucentini, which is played in a bus as it moves along the avenue, interacting with several points in the itinerary and thus generating a new set of sounds in every trip. These works reveal the possibilities of integrating interactive art in the public space, to the point that, as Ricardo Barreto indicates, “the new paradigm of public art will be the interactive city”. The busy Paulista Avenue is certainly a good location for the creation of an emerging, interactive city.

In this 11th edition, the FILE festival has achieved a state of maturity. The FILE PRIX LUX, FILE PAI and an estimated 25,000 visitors to date support its claim of being the largest festival of its kind in Latin America, and a steady event that places Brazil in the map of the international digital art scene. In a tightly interconnected world, each region is a node: there isn’t a center and a periphery anymore, there are no colonies. FILE exemplifies how a region can become a powerful node in this network by promoting the most recent developments in art and technology, avoiding obsolete distinctions between North and South and becoming a point of development for the future stages of our digital culture.

Co-published by Furtherfield and The Hyperliterature Exchange.

Last October I received an e-mail headed “Introducing Vook”:

The Vook Team is pleased to announce the launch of our first vooks, all published in partnership with Atria, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. These four titles… elegantly realize Vook’s mission: to blend a book with videos into one complete, instructive and entertaining story.

The e-mail also included a link to an article about Vooks in the New York Times:

Some publishers say this kind of multimedia hybrid is necessary to lure modern readers who crave something different. But reading experts question whether fiddling with the parameters of books ultimately degrades the act of reading…

Note the rather loaded use of the words “lure”, “crave”, “fiddling” and “degrades”. The phraseology seems to suggest that modern readers are decadent and listless thrill-seekers who can scarcely summon the energy to glance at a line of text, let alone plough their way through an entire book. If an artistic medium doesn’t offer them some form of instant gratification – glamour, violence, excitement, pounding beats, lurid colours, instant melodrama – then it simply won’t get their attention. But publishers have a moral duty not to pander to their readers’ base appetites: the New York Times article ends by quoting a sceptical “traditional” author called Walter Mosley –

“Reading is one of the few experiences we have outside of relationships in which our cognitive abilities grow,” Mr. Mosley said. “And our cognitive abilities actually go backwards when we’re watching television or doing stuff on computers.”

In other words, reading from the printed page is better for your mental health than watching moving pictures on a screen: an argument which has been resurfacing in one form or another at least since television-watching started to dominate everyday life in the USA and Europe back in the 1950s. To some extent this is the self-defence of a book-loving and academically-inclined intelligensia against the indifference or hostility of popular culture – but in the context of a discussion of Vooks, it can also be interpreted as a cry of irritation from a publishing industry which is increasingly finding the ground being scooped from under its feet by younger, sexier, more attention-grabbing forms of entertainment.

The fact that the Vook publicity-email links to an article which is generally rather sniffy and unfavourable about the idea of combining video with print no doubt reflects a belief that all publicity is good publicity – but it is also indicative of the publishing industry’s mixed attitudes towards the digital revolution. On the whole, up until recently, they have tended to simply wish it would just go away; but they have also wished, sporadically, that they could grab themselves a piece of the action. But those publishers who have attempted to ride the digital surf rather than defy the tide have generally put their efforts and resources into re-packaging literature instead of re-thinking it: and the evidence of this is that the recent history of the publishing industry is littered with ebooks and e-readers, whereas attempts to exploit the digital environment by combining text with other media in new ways have generally been ignored by the publishing mainstream, and have therefore remained confined to the academic and experimental fringes.

The publishing industry’s determination to make the digital revolution go away by ignoring it has been even more evident in the UK than in the US. The 1997 edition of The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, for example, contains no references to ebooks or digital publishing whatsoever, although it does contain items about word-processing and dot-matrix printers. On the other hand, Wired magazine was already publishing an in-depth article about ebooks in 1998 (“Ex Libris” by Steve Silberman, http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/6.07/es_ebooks.html) which describes the genesis of the SoftBook, the RocketBook and the EveryBook, as well as alluding to their predecessor, the Sony BookMan (launched in 1991). Even in the USA, however, enthusiasm for ebooks took a tremendous knock from the dot-com crash of 2000. Stephen Cole, writing about ebooks in the 2010 edition of The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, summarises their history as follows:

Ebook devices first appeared as reading gadgets in science fiction novels and television series… But it was not until the late 1990s that dedicated ebook devices were marketed commercially in the USA… A stock market correction in 2000, combined with the generally poor adoption of downloadable books, sapped all available investment capital away from internet technology companies, leaving a wasteland of broken dreams in its wake. Over the next two years, over a billion dollars was written off the value of ebook companies, large and small.

After 2000, there was a widely-held view (which I shared) that the ebook experiment had been tried and failed: paper books were a superb piece of technology, and perhaps a digital replacement for them was simply never going to happen. There were numerous problems with ebooks: too many different and incompatible formats, too difficult to bookmark, screens hard to read in direct sunlight, couldn’t be taken into the bath, etc. But ebooks have always had a couple of big points in their favour – you can store hundreds on a computer, whereas the same books in paper form demand both physical space and shelving, you can find them quickly once you’ve got them, and they’re cheap to produce and deliver. Despite the dot-com crash and general indifference of the reading public, publishers continued to bring out electronic editions of books, and a small but growing number of people continued to download them.

Things really started to change with the launch of Amazon’s Kindle First Generation in 2007. It sold out in five and a half hours. With the Kindle, the e-reader went wireless. Instead of having to buy books on CDs or cartridges and slot them into hand-helds, or download them onto computers and then transfer them, readers using the Kindle could go right online using a dedicated network called the Whispernet, and get themselves content from the Kindle store.

Despite this big step forward, the Kindle was still an old-school e-reader in some respects: it had a black and white display, and very limited multimedia capabilities. The Apple iPad changed the rules again when it was launched in April 2010. The iPad isn’t just an e-reader – it’s “a tablet computer… particularly marketed for consumption of media such as books and periodicals, movies, music, and games, and for general web and e-mail access” (Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I-pad). Its display screen is in colour, and it can play MP3s and videos or browse the Web as well as displaying text. For another thing, it goes a long way towards scrapping the rule that each e-reader can only display books in its own proprietary format. The iPad has its own bookstore – iBooks – but it also runs a Kindle app, meaning that iPad owners can buy and display Kindle content if they wish.

It seems we may finally be reaching the point where ebooks are going to pose a genuine challenge to print-and-paper. Amazon have just announced that Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has become the first ebook to sell more than a million copies; and also that they are now selling more copies of ebooks than books in hardcover.

It is certainly also significant that the past couple of years have seen a sudden upsurge of interest in the question of who owns the rights over digitised book content, and whether ordinary copyright laws apply to online text – a debate which has been brought to the boil by a court case brought against Google in 2005 by the Authors Guild of America.

In 2002, under the title of “The Google Books Library Project”, Google began to digitise the collections of a number of university libraries in the USA (with the libraries’ agreement). Google describes this project as being “like a card catalogue” – in other words, primarily displaying bibliographic information about books rather than their actual contents. “The Library Project’s aim is simple”, says Google: “make it easier for people to find relevant books – specifically, books they wouldn’t find any other way such as those that are out of print – while carefully respecting authors’ and publishers’ copyrights.” They do concede, however, that the project includes more than bibliographic information in some instances: “If the book is out of copyright, you’ll be able to view and download the entire book.” (http://books.google.com/googlebooks/library.html)

In 2004 Google launched Book Search, which is described as “a book marketing program”, but structured in a very similar way to the Library Project: displaying “basic bibliographic information about the book plus a few snippets”; or a “limited preview” if the copyright holder has given permission, or full texts for books which are out of copyright – in all cases with links to places online where the books can be bought. Interestingly, my own book Outcasts from Eden is viewable online in its entirety, although it is neither out of copyright nor out of print, which casts a certain amount of doubt on Google’s claim to be “carefully respecting authors’ and publishers’ copyrights”.

In 2005 the Authors Guild of America, closely followed by the Association of American Publishers, took Google to court on the basis that books in copyright were being digitised – and short extracts shown – without the agreement of the rightsholders. Google suspended its digitisation programme but responded that displaying “snippets” of copyright text was “fair use” under American copyright law. In October 2008 Google agreed to pay $125 million to settle the lawsuit – $45.5 million in legal fees, $45 million to “rightsholders” whose rights had already been infringed, and “$34.5 million to create a Book Rights Registry, a form of copyright collective to collect revenues from Google and dispense them to the rightsholders. In exchange, the agreement released Google and its library partners from liability for its book digitization.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Book_Search_Settlement_Agreement). The settlement was queried by the Department of Justice, and a revised version was published in November 2009, which is still awaiting approval at the time of writing.

The settlement is a complex one, but its most important provision as regards the future of publishing seems to be that “Google is authorised to sell online access to books (but only to users in the USA). For example, it can sell subscriptions to its database of digitised books to institutions and can sell online access to individual books.” 63% of the revenue thus generated must be passed on to “rightsholders” via the new Registry. “The settlement does not allow Google or its licensees to print copies of books in copyright.” (“The Google Settlement” by Mark Le Fanu, The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook 2010, pp. 631-635).

Google, it will be noted, are now legally within their rights to continue their digitisation programme. This means they don’t have to ask anyone’s permission before they digitise work. If authors or publishers would prefer not to be listed by Google it is up to them to lodge an objection online. Google would argue that in launching their Library Project and Books Search they have merely been seeking to make their search facilities more complete, and thus to “make it easier for people to find relevant books” – but whether or not they have been deliberately plotting their course with wider strategic issues in mind, the end result has been to make them the biggest single player – almost the monopoly-holder – where digital book rights are concerned. As a reflection of this, an organisation called the Open Book Alliance has been set up to oppose the settlement, supported by the likes of Amazon and Yahoo: “In short,” their website claims, “Google’s book digitization strategy in the U.S. has focused on creating an impenetrable content monopoly that violates copyright laws and builds an unfair and legally insurmountable lead over competitors.” (http://www.openbookalliance.org/)

Whatever the pros and cons of the Google Settlement, it has undoubtedly helped to focus the minds of writers and publishers alike on the question of digital rights. Copyright laws and publishers’ contracts were designed to deal with print and paper, and until very recently there has been almost no reference at all to electronic publication. Writers who have agreed terms with a publisher for reproduction of their work in print have theoretically been at liberty to re-publish the same work on their own websites, or perhaps even to collect another fee for it from a digital publisher; and conversely, publishers who have signed a contract to bring out an author’s work in print have sometimes felt free to reproduce it electronically as well, without asking the writer’s permission or paying any extra money.

But things are beginning to change. A June 2010 article in The Bookseller notes that Andrew Wylie, one of the most prestigious of UK literary agents, “is threatening to bypass publishers and license his authors’ ebook rights directly to Google, Amazon or Apple because he is unhappy with publishers’ terms.” This is partly because he believes electronic rights are being sold too cheaply to the likes of Apple: “The music industry did itself in by taking its profitability and allocating it to device holders… Why should someone who makes a machine – the iPod, which is the contemporary equivalent of a jukebox – take all the profit?” Clearly, electronic rights are going to be taken much more seriously from now on.

Further indications that authors, publishers and agents are beginning to wake up and smell the digital coffee can be found in the latest editions of The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook and The Writers’ Handbook. For those who are unfamiliar with them, these annual publications are the UK’s two main guides to the writing industry. The 2010 edition of The Writer’s Handbook opens with a keynote article from the editor, Barry Turner, entitled “And Then There was Google”. As the title indicates, its main subject is the Google settlement and its implications – but its broader theme is that the book trade has been ignoring the digital revolution for too long, and can afford to do so no longer: