Curated by Carolyn Kane for Rhizome September, 2009.

#60605 plus #20101 does not equal black, but it looks like it to me. And despite Newton’s insistence, a rainbow is never made from seven colours in neat lines, nor can I see millions of colours on my calibrated monitor. It is more likely that each day I engage with the screen as a greenish-blue glow infused with hits of magenta. Or as it is today: a summer grey of sea fog glimpsed through the rain. Is that a colour? Carolyn Kane curated HTML Color Codes in order to ask these questions of the relationship between colour, code, and subjectivity. Tracing a carefully structured path through twelve artworks Kane seeks to examine whether artists working with the Internet are limited to a ‘ready-made’ colour palette. Asking if digital colours reflect the programming languages that have been adopted, Kane considers whether the Internet adds its own rules for colour through the adoption of the hexadecimal system of colour values. Does the language determine the content?

The answer is, not quite. It all depends on where and how the viewer approaches the screen. Rather than trying to be paintings these works engage with the materiality of digital colour and the manipulation of a different kind of flat predetermined surface – the screen. Chris Ashley gives us rectangles within rectangles, Dlsan manipulates circles within circles, and Michael Atavar offers the blue screen of an empty window with text written as if in the condensation of a cold morning. It is the noise of the digital image embraced by the inadequacy of a gif representation of a treasure heap of digital gold in Jacob Broms Engblom’s “Gold”, or the absence of any controlling frame in Owen Plotkin’s “Firelight” and the flickering spaces nested within and alongside one another in Rafael Rozendaal’s “RGB” that suggest different rules for the digital image. In these latter works the illusion of immediacy raises a spectre of some kind of phenomenological directness.

Twentieth century colour field painting was never a single set of experiments yet it carried within it a set of cultural and formal presuppositions. The digital colour field has its own baggage set. It is inbetween: inbetween code and software, browser and window, network and bandwith. More often than not the experience of the digital colour field is the result of an image within an image or a screen within a screen. Despite its origins in hexadecimal notation digital colour is not a ready-made, but an experience and a process of light and interaction. Anyone who has attempted to capture or translate a colour between screens knows that accidents occur. Noah Venezia’s “The Rainbow Website” suggests that a kind of synaesthesia can be experienced through the screen, that colour exceeds the values assigned to it. Andrew Venell’s “Color Field Television” mimics the flicker of experimental film from the 1970s. Perception becomes a process of seeing the colours inbetween, the work turns back on itself mirrored within a screen. Structural film experiments were about exploring more than perception they too turned back to the medium. Morgan Rush Jones gets even closer with the phased colour space of “Number of ManufacturingIndustriesbyNumberof Product ClassesinanIndustry”. The work is simultaneously overloaded with image and abstracted from it. There is a strange congruence reflected here: in their formality these works do not push new experimental boundaries but reflect older ones.

Michael Demers explicitly engages the materiality of the digital medium by establishing a series of systems within which abstraction can occur. Sampling Morris Louis’s oil painting “Where” from 1960, Demers generates a sequence of flat colour planes (windows) from left to right that disappear as quickly as they appear. The drip and movement of Louis’s work is rendered temporal. Brian Piana’s “Elsworth Kelly Hacked my Twitter” also addresses the temporality of the digital. Real-time data orders the compositional frame in a direct chronological sequence. Each square is a representation of an invisible network. Manipulation of the scale, size and shape of the frame is left to the viewer. For me it is Elna Frederick’s “@ = landscape” that allows an interactive experience of the subjective dimension of colour that is specific to the digital. The click of a mouse becomes the experience of putting a finger into a stream of water and disturbing the flow. It is not necessarily the colour that makes the rain but the movement and the belief instilled in us from Super Mario that onscreen fluffy white blobs potentially contain rain. There is a cool sensuousness to the trickle of pixels as it becomes water and when left alone returns to simply being yet another onscreen blue.

There is a risk of over determination in this show, the kind of visual parity that results from too many works looking at the same thing and becoming somewhat redundant. It is the quiet spaces between the works, the mutable changing structures of the blue screen that resist this limitation. As long as bandwidth remains with us, and the links stay live, these works are infinite and through their repetition we experience an abyss of generated colour and code. These are predominately forms consisting of colour alone, and surprisingly, that is enough. This is how the medium of digital colour should be approached. There is no translucency, but there is an unlimited interplay of substitutions.

Featured image: An interview with Chris Dooks, a ‘Polymath’ exploring various creative avenues, making his art using different media.

One of the many interesting and rewarding elements of being deeply involved in what, I’ll loosely term as ‘media arts’ practice, is the breadth of imaginative people you meet along the way. We first met Chris Dooks in 2005-6, when he worked with us on a project by Furtherfield called 5+5=5. We commissioned 5 short movies about 5 UK-based networked art projects exploring critical approaches to social engagement. These pieces offered alternative interfaces to the artworks and the every-day artistic practices of their producers. Including the motivations and social contexts of artists and artists’ groups working with DIY approaches to digital technology and its culture, where medium and distribution channels merge. Chris produced a film-work for the project called Polyfaith. A Psycho-Geographical Web Project introducing the beliefs and philosophies of his (invented) friend Erica Tetralix.

“My friend Erica Tetralix died. She gave me the task of fulfilling her dream which was that people would enjoy the parts of Edinburgh that were so dear to her in her life. She also loved tourists and sympathised with people on a budget, so she devised, with my posthumous help, this free way to enjoy the city. It’s a beautiful gift for both transients and residents. It’s popular with backpackers, parents and children, cultural groups and well, basically anyone.”

Later on we discovered that the name Erica Tetralix, is actually a name of a plant. Often called a cross-leaved heath, a species of heather found in Atlantic areas of Europe, from southern Portugal to central Norway, as well as a number of boggy regions further from the coast in Central Europe.

To view Polyfaith visit link below:

http://furtherfield.org/5+5=5/polyfaith.mov

The value of an interview is that it can serve as a useful documentation, a process allowing a kind of unfolding of time, All layed out in front of you. The reader can experience not necessarily a retrospective, but a dynamic and creative life and a personal history openly shared, on their own terms.

This interview reveals various levels and approaches by Chris Dooks. An inquistive and playful mind is at work here, engaged in exploring across different forms of personal agency, as well as redefining his practice in relation to the world he exists in, and the people he comes across in connection to various projects. His art is not a singular activity. Meaning, he does not rest in one particular art genre or movement. Instead, we are asked to acknowledge a personal enquiry formed from different engagements and choice of mediums, which happen to meet his creative intentions and questions at the time. We are all relational beings and Chris Dooks is a clear example of how this can work in an artistic context.

The Interview:

Marc Garrett: Many out there will already know you as a professional film maker, directing arts-based TV documentaries such as The South Bank Show in your twenties. Since then, you have developed other skills involving design, composing and making music, audio visual installations, explorative psychogeographical projects, as well as continuing making films, and you’ve even got a record deal. You have as far as I can gather four different music projects curently on the go, your electronica group BovineLife, an architecture music project known as As Ruby’s Comet, Feible for laptronica and also the Audiostreet project featured at The Leith Festival.

Chris Dooks: It’s amazing how many people still know me from Bovine Life which was a moniker I used for an internet audio project way before broadband in 1999. It’s the tenth anniversary of my bip-hop album SOCIAL ELECTRICS and I would like to make all my albums available for free for furtherfield readers. Don’t let itunes rob me of any money! The transition to musician was down in part to the South Bank Show when working with Scanner. I was really frustrated at making work about musicians. And the technology was making it easier for folks like me without a classical training. Here are three for you for free – check links below for free tunes at the bottom of the interview.

South Bank Show UK television documentary directed by Chris Dooks, featuring Robin Rimbaud speaking about his practice and ideas. 1997. Click here to watch video.

MG: In The Glasgow Herald, in Scotland a journalist called you a Polymath. Even though you were delighted to receive such a compliment in the local press, you decided to re-edit the term, reclaim it so to make it less seemingly mathmatical. Prefering Polymash because it sounds “friendlier, resourceful and potentially charming.” Sticking with this notion of you being a Polymath or rather a Polymash. Your diverse approach in creating art works in a non-singular approach, is a core element of your practice. I was wondering whether this is a deliberate decision or a natural and overall state of being?

CD: It’s weird though, I learned more in my background as a wedding videographer aged 14-19 (35 weddings at weekends!!!) than on any other course. Doing weddings gives you various skills as a digital artist. Fuck a film degree! As a wedding videographer, you need to be able to mike the vows in difficult audio environments (i.e. reverby spaces), film it about fifty feet away, liaise with highly emotional temperaments, be like a war photographer – it’s only gonna happen once, miss it at your peril – and stay sober. Not to mention edit it at a time when non-linear editing was non-existent, (I remember the heady days of “crash editing” between two panasonic VHS machines) white balancing everything on manual heavy equipment and creating all the graphic design and labelling of tapes. I was like a teenage record label!

So in 2009 when I made www.studio1824.com – making a record (netlabel) for an icehouse in Sutherland (remote Scottish Highlands) I got a kind of deja vu experience. Only with an education and life experience in the mix now.

When I was 8 years old, I had two epiphanies. One was that death is really gonna happen, and two, that cinema is wonderful, emotional and that it offers us a naive form of immortality. Cinema was the only artform that even at that age, I felt could make me feel…spiritual, for want of a better term. I became quite religious.

I was obsessed with super 8 cameras and video. And now I am trying to get all my pre-teen works tracked down! But even at this stage there was always a healthy distraction in other areas. I wouldn’t get involved with narrative and this has never been my strong point, even though I was reasonably good with words. My uncle played a lot of classical music and my dad took me all over the UK in his lorry, and at this time I won a scholarship to play the cello at school with the posh kids, being the other three. (It was a working class music “initiative”) But alas, I didn’t realise how lucky this was for me. So I went back to making videos, this “poly” approach was probably set quite early. I remember doing a kind of pre-Blair Witch thing when I was 14 and I would get sidetracked into filming the shapes of the leaves and the sound of the wind. Then I realised that the material didn’t make sense in the conventional sense. So I became an aesthete of kinds at an early age. And in every way, from Granny’s trifles and an early lust for Kate Bush, I was concerned with the sensual world. But until 22 I was monogamous to film projects and would work as a corporate director in the art school holidays to fund my college life, with the odd wedding video thrown in. By the time I did my film degree at Edinburgh College of Art, I was much more interested in people like video artists Bill Viola, Gary Hill and Daniel Reeves – (I met all three) via the “team-building” world of film shoots. Bill Viola’s THE PASSING changed my life.

The Passing, 1991. In memory of Wynne Lee Viola. Videotape, black-and-white, mono sound; 54 minutes.

Pre-degree, in those days (1989-91) you had to REALLY know your kit and be a good all rounder. I trained on huge Umatic machines and did a BTEC before a degree. I was from a part of a culture where there was no film degree, and I was a couple of years behind my peers. But by the time I hit ECA, I could mix radio programmes, edit timecode, black and white balance studio cameras and location kit and I spent most of the time buggering off to the hills to film Scottish waterfalls. I might have been techinically proficient and this was behind the poly approach to an extent, but I had bugger all conceptual skills. These have only really solidified in my thirties…

MG: Lets talk about the Surreal Steyning psychogeographic audio tour, part of the The Steyning Festival in 2009. On the web page for the project is written “This tour is simply a different way to skin the proverbial cat. In this case, the cat is Steyning. In fact, if you think of Steyning as a cat, you are already a psychogeographer. Well done. You’ve engaged your psyche with geography. You’ve mapped the town conceptually. The High Street becomes the cat’s spine with the head chasing Mouse Lane. Now you are in the same company as such artist groups as the Situationists, the Dadaist Movement and other high fallutin ripples in art tourism, and even The Ramblers.” Did those who took part manage to understand and appreciate where you were coming from? Also, how did it work?

CD: There was a tiny degree of spin with the site’s headline Traditional English Town Embraces Conceptual Art Walk but by and large folk did embrace it and it would have been patronising not to drop a little sand in the vaseline, not to deliberately challenge, because the Steyning Festival, was, I felt, in danger of being a little like a tasteful village fete. A good fete I might point out, so this year, there was something brave about them putting a conceptual artist at the heart of a residency in the village. English villages like Steyning were not and are not, all tasteful. Whenever I encounter these tasteful expectations in the arts, I think of that Stereolab song, Motoroller Scalatron with it’s chorus “What’s society built on? It’s built on blood. (some say the lyric is “bluff” not blood but either way it works)” So I saw my role not as a socialist historian, because I wouldn’t have a clue, but as someone who encourages an enquiry per se into unusual histories, paganism, aesthetics and philosophies of very local travel. I mean, I don’t think there’s anything angry or unloving in the tours. In fact, I try to make them about folk being nicer to each other. These activities have a small socialist agenda but as a performer, I am not exactly Stelarc, slashing my wrists in the street. I’m not about shock! However, this tour had a couple of “jaw droppers” (See The Steyning Star on the tour). The main outrages came from people who wanted a straight history tour and were not given one, depsite my first words on the tour saying “this is NOT a history tour!”

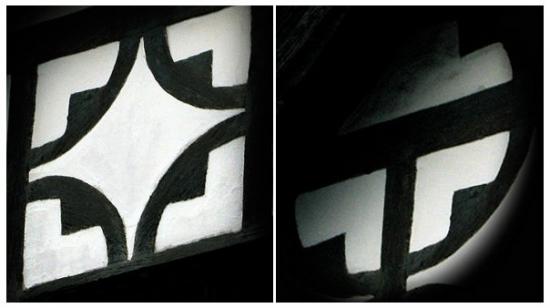

Example taken from section 4 of the The Steyning Star on the tour:

“This is Brotherhood Hall, built in the fifteenth century and now part of Steyning Grammar School. Look closely at the symbols which adorn the gables. They may look like simple decoration to us, but these markings are rather unusual. They have been the subject of no fewer than three PhDs, and for a century the world’s leading symbologists have engaged in hot debate over how to read the meaning of them. One of the most important questions is what shape we are dealing with. While some people see predominantly circles, others see squares and diamonds, rather like those tiles that everyone had in their bathrooms in the 1970s.”

“Was this a pop premonition? For some time it seemed so, and this remains a strong theory. But in the mid 90s the school took part in a German exchange programme, and visiting German students proposed yet another alternative. When they looked at the patterns on the gables they saw a cross drawn within the circles, or a gammadia, to be more precise. A gammadia is a cross voided through, or a cross formed with four of the Greek letter Gamma. It looks a bit like an ‘L’ to us. The swastika is the most famous example of a gammadion. The German students believed that this was not a pop premonition at all, but a foretelling of the success of German heavy metal band Gamma Ray. This theory also gained popularity among members of the school’s very active astronomy club.”

The festival had hired a PR person to market aspects of the festival and commission an artist, and so I was brought there with a little Arts Council of England fund, so felt obliged to make work with the tools I’ve been developing – or my “brand.”

Nothing was watered down simply because it was a village (it’s actually a town but it feels like a village) because it would have meant compromising the ideals or enquiry, of looking deeply and into the areas of my interests of paradolia (faces in chaos) and simulacra formations (things that appear to be other things).

Most of them got it! I mean, it was nearly two hours long and they stayed till the end, although it did split the audience, but not badly. 2-3 out of 20, left. We had to do it again the next day due to popular demand! The ones who stayed had smiles on their faces by and large, which made me very happy. The weird thing was, not once had it been stated that it was a “straight history tour”, and it should have been obvious within the first thirty seconds that I make some of the stories and hypotheses so outrageous that surely this is tongue in cheek? However, I had written some slightly anti daily mail sentiment in it and two or three people angrily walked out of the tour. I got that wrong. It’s a Tory (conservative) heartland, and I don’t think you can be an artist and right-wing, you are just too aware of the world, but I should have considered this aspect more.. My landlady was one of the people present in the audience and she walked out, that upset me a wee bit.

But there’s something about my personality that makes people trust me in my tours, folk are quite sweet and gentle perhaps. The message behind the tours is one of re-imagining everything you hold to be true. The motivation behind these tours is to see travel as something that can be done anywhere. People go to the other side of the world to enrich their lives, many don’t even journey over to the other side of the street, or drive through a different part of town! I find that hilarious. So for me, psychogeography is about the chicken crossing the road..

If we can’t even do that, what hope is there for atheists like me (who find Buddhist philosophy and its practice the only religion without the conceit of the other big hitters) who are forced to approach the world from multiple angles, because we can’t accept the idea of monotheism and monotheistic thinking. This single mindedness of approach, when challenged (not just in religious people, but people stuck in their ways) is bound to create a bit of friction even on a playful level like in Steyning.

I became invloved in Surreal Steyning based on another project, in Brighton, where I made several songs about a building on Brighton sea front. This was a song cycle, based on a very specific bit of geography.

There is this idea that psychogeography is only urban – but I prefer to bring this intense work to the home counties! After all, the whole point of being an artist is to see through the privets, the darkness of the forests. So while I was in Steyning I was reading about Alistair Crowley and witchcraft and when Steyning used to be a port – it’s now land, ten miles inland! In the middle ages everything was different. I think a lot about how many contemporary English folk in these wee villages don’t realise their own foundations. I found Steyning a really charged place and not just a twee place to get (admittedly excellent) cream teas and real ale (a bit flat for my northern British palette).

This was, without a doubt though, the most successful public psychogeography tour I had done, even more than Polyfaith. There have only really been three tours – Polyfaith, Select Avocados and Surreal Steyning. And Surreal Steyning learned from the other two – so I had my schtick by then. I think it’s the best executed one so far. Let me be clear, I care about the audience. I adapted to their demographic, their language and their refinery in this tour, but I really care about people, but what I hate is bigotry and there was a little bit of friction about some of the left-wing ideas in the work and some of my own goals. But they needen’t be upset by a Middle East reading of a thatched cottage, the similarities of Tudor graphics and the 1990s version of the Take That logo, and the roof of some flats that might look like an arrow.

MG: This critical approach of consciously making room within yourself to understand or at least appreciate the sensibilities of others, surely it must be a difficult task to accomplish? What I find fascinating about your engagement with the public is the measure of respect for them, mixed with a healthy level of detournement.

Thanks! I actually think it’s a big complement to have the public stay on a tour for up to two hours, or buy one of my records. So I’ve really tried to attack attention-deficit tendencies whenever possible. It’s also my grammar. I don’t really do critical theory, although to apply for money you need to know where your bit of culture fits in with others. I really dig a good bit of popular culture. I think the best stories in our culture in the UK can all be seen on Jimmy McGovan’s The Street. He is a master of audience respect. Also, I feel confused by a lot of art, so I like to call a spade a spade, unless I am in a surreal mood and I’ll call it a Sad Ape (Sad Ape is an anagram of A Spade).

I had a slightly uncomfortable childhood and adolescence That “public” thing comes from Teesside. I also particularly like North of England humour – and actually I really like it when “clever shits” (to quote my Granny RIP) get usurped by that kind of spit-and-sawdust philosophy. There’s something survival-like and super-clever about grass roots humour because it comes out of neccessity. So I think my own personality is a bit of art school but with angry chips on both shoulders. It’s why working in Scotland is great, because the Scots hate bullshitters – especially the Nathan Barley set. I always found that very attractive. I remember seeing and being heavily inspired by Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer’s first series and thinking, this is a dangerous combination! Northern swagger and charm! Dada! but with more academic kudos than might appear at first glance. And it was bloody funny! It was both alienating and accessible at the same time.

I grew up in Teesside and North Yorkshire and school never encouraged me really. I never had a bohemian upbringing, but I believed in the soul and went to Sunday School (my own choice – I was very religious for a kid). But I probably owe my interest in orchestral and “difficult” music to my uncle, and this was partly my first exposure to other worlds – I was particularly inspired by Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. And I liked that piece because it had something I could relate to (the church organ), it felt something otherworldly – both the sustained drones and mechanical math-like, transcendental nature about it. And no words. I remember talking to my music teacher about it. She got all excited and presumed I could play it so she got me the sheet music to learn it. But I could never do it, I had no discipline. Anyway, that piece was amazing, spiritual to me. When you thought it couldn’t end, it changed scale and key and ascended to even more articulate heights, clever and gorgeously aesthetic at the same time.

I failed art. I grew up around lorry drivers, grandma’s trifle and Christmas at working men’s clubs. A lot of nice memories but I’ve always been looking for ways to sweeten the sour ones. And then, a huge affliction came. Around twelve, I started to have these really strong life changing shocks, like my psyche being ripped to shreds – just by thinking, enquiring, looking deeper. I would call them “dark epiphanies” later. They are still with me. Adulthood has not softened them. I’m always on the lookout for liberation! Like Russel Crowe in A Beautiful Mind he learns to live with his Demons and accept they are there! I’ll never get over these mortal messengers, but it’s what underpins all the puns and humour in the work. Tears of a Clown maybe? At the time, (aged 12-15) there were pennies dropping about mortality – real hopelessness of mortality. I’m still dealing with it. The problem is, because these visceral thoughts will never go away, I have started trying to make them my teachers. And all I want to do across all of my works is reduce anxiety – mainly my own – and look at multiple universes – and I think we forget that your street is part of the universe. That’s where the work begins, in your block, your local Lidl – these places should teach you as much about our ridiculous situation as anywhere else. It’s like that idea that “the environment” is outside somewhere, when really it’s in the most mundane places. The mundane is “supramundane” at the same time. It’s no wonder I became a Buddhist in my early thirties. I need to get back into it. I’m getting somewhere maybe.

MG: Perhaps, it is not just about re-inventing a selection of different mythologies, histories in relation to localities, whilst exploiting contemporary mediums; which includes elements of satire, a certain level of hyper-reality.

CD: I think it’s about a hatred of authority, not because we don’t need order, I think we do, but authority takes all the colour out of our history and culture. I watch X-factor, like Peter Kay (underrated surrealist like most comedians – despite the professional Northerner get up). I never liked punk and thought anarchy was really stupid! Civil disobedience maybe. I hate it when I see musos on the telly talking about punk, getting all nostalgic. Maybe the Clash. Maybe it’s the patronage of culture by high fallutin’ types I don’t like. Because patronage kills proper culture doesn’t it? And because of that, I never got passionate about history at school. It was a bit grey. So what do I do without the arsenal of the passionate historian? I make bits up and flirt with it. These projects mean I have to know bits of history now. And this bit is really telling – the bizarre thing about the hyper-reality aspects of my tours and other works – is that the bits I make up and flirt with – those bits are often scarily close to the truth. Also you say I’m really respectful to the public, but I like to push it a lot. In Edinburgh, on the Polyfaith tour, folk were swallowing my wildest tales about the city when they’d lived there all their lives! I came in under the radar I suppose. I like usurping the pompous stuff with a passion though, I really do, I feel it’s my duty!

MG: There seems to be a kind of niggling question in this work. I get a sense that this question does not only relate to asking those who take part, but also yourself. It touches upon something quite raw, authentic and complicated, and untouchable at the same time. I am not referring to the sublime here, it relates to all of our collective histories, on this earth. A Genealogical form of re-assembling, re-knowing and perhaps not knowing. Are you trying to make contact, or reconnect some how to a type of authenticity; if so, what does this look like in respect of your intentions?

CD: I want to find spiritual relief. That’s a terrible word – maybe the sublime is better. Fuck it, I want it back from the New-Agers. Even though I am a total Dawkins fan, and am partly liberated by looking deeply, I just want a bit of peace really. And the tours train me to think outside the box, that’s it. I suppose it’s like doing my own philosophy degree “in the field.” But there’s a bigger box I am being prepared for (see what I did there!). There’s not much relief. I am a highly charged person – some would say high maintenence! I’ve just seen the Andromeda galaxy from the back garden. I want more of that. This is a really hard life. I want to be less fat. I’m sick of having M.E. My wife is pregnant. Christ, I am going to be a father. Maybe that will help my afterlife woes. Men aren’t supposed to moan. I’m being genuine here though. I forgot to mention Derren Brown. I’d love to do a project with him. I am sorry these answers are not very articulate. It’s in the tours! Do them!? Seriously, do the tours.

MG: What qualities and values do you think or feel this form, process and working offers yourself, the world, art and culture on the whole?

CD: I look at my place in the digital arts as a priest being sent to a remote parish – so hopefully we’ll clean up here in Ayr, our new home! ha ha! A lack of funding might make that difficult but it hasn’t stopped me before. My current thoughts are… Paradolia and Simulacratic Forms as narrative agents for psychogeographical tours. The benefits of the sustained drone in music. “Dayglow” hues and man made fibres in landscape photography. High hills. The idea, place and value of the troubador in the present age and the potential of “singing the news” as a deterrent for media-saturation. My next project may be about folk-music and psychogeography, using local folk clubs to make popular songs based on themes by bloggers. Some of the things I think of, I sometimes see being made around the time. A bit of Zeitgeist, collective unconsciousness awareness maybe! I am also still digging around popular atheism and the atheistic roots of Buddhism. Folk-Art and the search for genuine Scottish culture as opposed to the much-touted facsimile. These are my daily concerns. A project that I should mention is Ayrtime. A series of eclectic cultural events presented in the heart of Ayr, Scotland. Gigs, Theatre, Literature, Astronomy & more – on this site you can find archives of the events with beautifully crafted podcasts!

My work offers me the stuff I was told at school really. No different to building or plumbing on one level. Just a sense of achievement and pride I suppose. Quite traditional aims. I remember a conversation with my dad in the last few years (we row a lot) in The Ship Inn in Marske. I asked him why he never wants to know about all these fantastic projects I’d done! And he said “Well that’s your work isn’t it? If you were a plumber we wouldn’t be sat here discussing U-bends” and at first, I felt slighted, I’m not a plumber I’m an ARTIST goddammit!! It made me think of The Cohen’s Barton Fink, human and pretentious character “The life of the mind, there’s no roadmap for that territory” but on reflection it’s quite good to be making this mad work in working class areas, to take my artist ego down a peg or two. Lord knows I need it sometimes because I have two fights generally – the first is the fight to get work funded and made and promoted and so on and it be stimulating work. The second is the fight with M.E. which I feel like I am totally on my own with a lot of the time. I get really unpleasant symptoms, often with no break for weeks on end. Sometimes I can only do 30 minutes of work in a day. Sometimes, even that is a pipe dream. I’ve had twelve years of this shit. I was directing arts documentaries for telly when I was well. The upside of the M.E. is that it is humbling. I’d probably be that Nathan Barley wanker by now, and I wouldn’t have touched the Buddhism, the philosophy, proper art and gotten arts council funding without the lessons I have learned.

Social Electrics 10 year Anniversay edition 1999 – bip-hop.

You Know, You Love Something Little – Lost Vessel 2002.

The Aesthetic Animals Album 2008 – benbecula records.

www.eleanorthom.com

www.karencampbell.co.uk

www.alanbissett.com

http://www.louisewelsh.com

Digital Pioneers

Victoria And Albert Museum

7 December 2009 – 25 April 2010

(Illustration – Herbert W. Franke, Squares (Quadrate), screenprint, 1969/70)

Digital Pioneers is a deceptively modest exhibition hidden away in two rooms upstairs at the Victoria and Albert Museum. It contains some of the earliest examples of art produced using electronic devices and computing machinery along with some creative later work.

The bulk of the art in the show was produced between the 1950s and the 1970s. This means that it was produced or recorded as photographs from cathode ray tubes or as print-outs from teletypes and pen plotters. Some of this work will be familiar to students of the history of art computing through reproductions but as with most art reproductions do not tell the whole story.

Seeing the actual work itself is as important for art made using the paraphernalia of early digital computing as it is for art made with linseed oil and cotton duck. What Digital Pioneers drives home is just how deeply and intentionally involved early computer artists were in manipulating the aesthetically limited but socially and ideologically key technology of computing machinery. This leaves both social art historians and code aesthetes with some explaining to do, or at least some catching up.

The show starts in the 1950s with the algorithmic and electronic but non-digital and non-computational photographs of oscilloscope patterns by Ben Laposky and screen-prints of photographs by Herbert W. Franke. Most of the works included in the show are prints of one kind or another, and these are no exception. They record the movement of a beam of light on a cathode ray tube as other prints in the show record the movement of a plotter pen or a laser in a laser printer.

If Constructivism was socially realistic for revolutionary Russia then these works are socially realistic against the backdrop of NATO’s military-industrial-educational complex. They turn the technology of that culture back on itself, using it not to produce weapons or market products but to produce aesthetics. This reclaims a space for perception and contemplation that is not simply militarily or economically exploited. The obsessively quantitative managerial culture of spreadsheets and inventories yields uncomfortably to the qualitative culture of aesthetics, productively so. These strategies continue through the show. Technology is pushed beyond its intended uses to address cultural tasks.

Many of the prints in the show have a similar number of stages of production to Franke’s process of screen, then photograph, then silkscreen prints. His later plotter-drawn work is also screen printed, as are Klee-inspired generative images by Frieder Nake, and Charles Csuri’s random montage of flies. I don’t know what to make of this. It feels like something should have been lost in the move from an original to a print but plotter drawings aren’t particularly originals, being already representations of data structures in the computer’s memory.

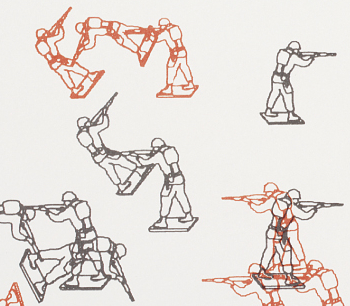

Csuri’s lithograph of randomly placed vector outlines of toy soldiers was produced in 1967 during the Vietnam War, a war that ran as long as it did in no small part due to game theory and computer simulation. There are two armies, one plotted in red and one plotted in black. They meet and presumably battle inevitably but only by chance. There’s more of the outside world in art computing than is often assumed.

William Fetter’s wonderful three dimensional vector images of human figures produced for the aircraft manufacturer Boeing, a lithograph from the Cybernetic Serendipity show of 1968, also deal with the human figure within the military-industrial complex. We should not be confused about the status of such images as art by the use and funding of computer graphics by corporations any more than we should be confused about the status of painting as art by the use and funding of oil painting by the Catholic church.

Ken Knowlton’s cheeky nudes and other typographic images of the 1960s and 1980s are an effective escape or release from the constraints of corporate information culture. I’d seen them many times in reproduction but again they are much richer visually as prints.

More detailed systems-based patterns emerge in the 1970s in the work of artists such as Manfred Mohr, Paul Brown, and Vera Molnar. This era that epitomises the approach of rule based serendipity so beloved of later Generative artists. These images are pleasurable to look at but also contain visual or psychological complexity. They also continues to push the performance of computer systems outside of their intended use cases.

By the late 1980s the technical achievements of computerised mass media were exceeding those of art computing. Pen plotters, where they were still used, were no rival to laser printers. Rendered images had to compete with the earliest rumblings of Pixar and Adobe. The increasing availability of digitally designed fashion and entertainment meant that far from being the exception, digital elements in the lived visual environment were becoming the rule.

The reactions to this that art computing in general have made are the subject of the Decode show that is also running at the V&A. Digital Pioneers instead follows the printmaking thread of art computing into the present day where artists such as Roman Verostko, Mark Wilson and Paul Brown have continued with the systems art all-overness of print-based art computing.

To continue in this way marks such work out as something different from the all-pervasive presence of digital imagery in the visual environment. The work has to look different from graphic design and new media rather than from CAD plots or teletype reports, and it does. These works remind us of the history and of the wiring under the board of digital culture. They successfully resist any attempt to reduce them to digital mass media images comparable to the output of the design software that they exist in the same era as.

This switch away from early adoption is necessary to maintain a figure/ground relationship (or a critical distance, or a constructive difference) between the general level of technology in society and the level of technology in art computing. It is not the only solution to this problem, as the Decode show demonstrates, but it is not a retreat.

As a long time fan of Harold Cohen, I found the show’s inclusion of computer generated works from his very earliest 1960s felt-tip-on-teletype-print experiments with generating figure and ground relationships computationally to a recent large-scale full-colour inkjet abstract was a real treat. Plotter drawings of abstract shapes from the 1970s and of human and plant forms from the 1980s show the progress that Cohen made in using computers to rigorously explore how art and images are created and function. Being able to study this work close-up reveals details such as debugging information in the teletype prints and the operation of the collision-detection algorithm in the 1980s images. And it provides the pleasure of seeing detailed, well-composed drawings.

This is a recurring experience in Digital Pioneers. Despite the uniformly dismissive attitude of both popular and academic criticism towards art computing the fact is that when you actually see the work in the flesh it rewards sustained attention. Not as historical or technical curiosities, but as images with cultural and aesthetic content and resonance. To ignore this and to continue to claim that this art is less than the sum of its parts would ironically be to fall prey to a particularly extreme attitude of technological determinism.

The show also contains displays of ephemera including magazines and books such as back issues of the Computer Arts Society’s “PAGE” and William Gibson’s supposedly self-erasing story on a floppy disk “Agrippa”. I’d not seen an actual copy of “Agrippa” before. PAGE back-issues are available online, but their presence here flags an important point.

The revived Computer Arts Society has been key in promoting and deepening understanding of the history of art computing in the UK. The Digital Pioneers show and its excellent accompanying book are a good example of how CAS’s project has spread out into more traditional cultural institutions, and many of the images and exhibits in the show come from the archives that CAS has donated to the V&A.

The “Digital Pioneers” book (by Honor Beddard and Douglas Dodds, V & A Publishing, 2009) serves as a catalogue for the show . It contains an informative introductory essay and printed images of many of the works on display as well as a CD-ROM with 200dpi scans of them. These scans are high-resolution enough to be able to examine the images in some detail, although they are no substitute for seeing the images in the gallery. A slightly excessive copyright licencing notice is the only indication that the book has in fact been produced as one in a series of pattern books from the V&A. It’s a must-have if you enjoy the show or have any interest in early art computing.

Digital Pioneers is an opportunity to really look at the work of early computer artists and to evaluate that work directly rather than through the medium of poor reproductions or through the fog of received critical opinion. As a slice of artistic history that just so happens to have been produced on computer it contains much to reward both the eye and the mind.

Update: Two recently published books provide more extensive background to the period covered by the show, making the history of this fascinating era available to current practitioners –

White Heat, Cold Logic: British Computer Art 1960-1980‘ edited by Charlie Gere et al covers the history of British computer art and the Computer Arts Society.

A Computer in the Art Room by Catherine Mason describes the relationship between British art schools and computing (which is how I became interested in this area in the first place).

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

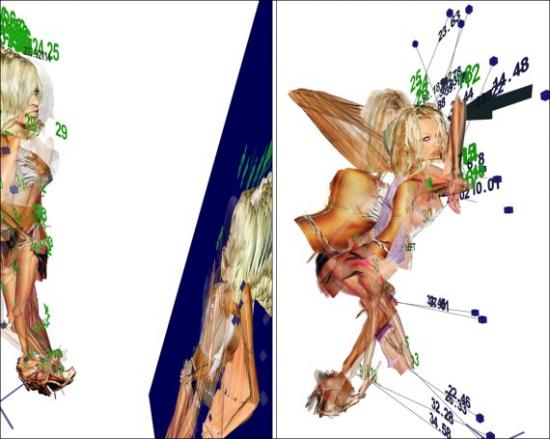

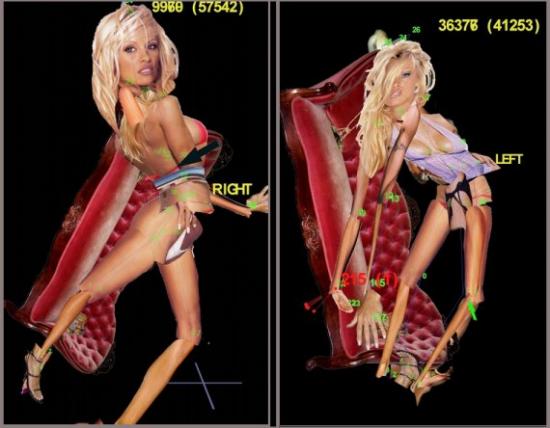

Mark Napier’s Venus 2.0

Angela Ferraiolo

February 5, 2010

“Now that I’m done’ I find the artwork disturbing. It freaks me out. Maybe I’ll do landscapes for a while to detox.” — Mark Napier

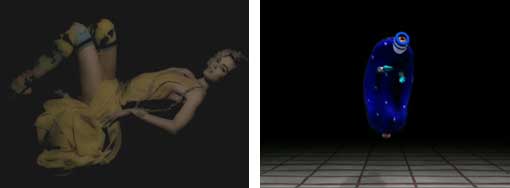

Artist Mark Napier, well-known for the net classics Shredder, Riot, and Digital Landfill, recently exhibited his latest work Venus 2.0 at the DAM Gallery in Berlin. A sort of portrait via data collection Venus 2.0 uses a software program to cross the web and collect various images of the American television star Pamela Anderson. These images are then broken up, sorted by body parts put back together and — as this inventory of fragments cycles onscreen, a leg, a leg another leg — the progressive offset of each rendering of Anderson’s head, arms, and torso makes her reconstructed figure twist, turn and jerk like a puppet. It’s odd looking. Even her creator is a little afraid of her:

“I have to say’ if I ever meet Pamela Anderson in real life I think I’ll completely freak out and run away. I don’t think I could have a conversation with the woman after this project … I started with a sympathetic view of the actual Pamela Anderson. She is part of the spectacle of sexuality in contemporary media. She’s caught in that ‘desiring machine’ as much as any other human’ probably even more so. She has surgically modified her body in order to have greater leverage in the media. Does this put her in control? I think not.”

Napier’s project doesn’t answer or intend to answer the question of who is in control either, but it plays with the possibilities. Although I wasn’t able to see the portrait at its exhibition. I did track down part of the series Pam Standing at a private location here in New York. Napier has also posted video excerpts of the work online. Unfortunately, these still images and clips are a bit too static to really do the piece justice. If you get to see the real thing and if you look for a while, you’ll see what I mean. Venus 2.0 is an amazing jigsaw puzzle, a deceptive surface of shifting layers – part painting and part search result.

The effect is translucent, lyrical, mathematic and creepy. When I implied that it must have taken an awful lot of precision and calculation to get something like this to come together, Napier insisted that focusing on the technology behind Venus 2.0, its algorithm, or even on the unique materiality of networked art in general, is a way of missing the point. The way he relates to Venus 2.0 is through the painter’s hand. What counts is not the data feed, but who were are, what we want and how we behave:

“The artwork is a riff on sexuality as an elaborate hoax played by a precocious molecule that builds insanely complex sculptures out of protein, aka, meat puppets or more simply, ‘us’. These animate shells follow a script that’s written and refined over the past half billion years. And that script is in a nutshell: 1) survive 2) reproduce 3) goto #1. So sexual attraction is the carrot to DNA’s stick. Attraction is part of the machine. In art history this appears as the tradition of Venus. And more recently: Duchamp’s ‘Bride’. Magritte’s ‘Assasin’. Warhol’s ‘Marilyn’. The focus of digital art is still the human being. Don’t be distracted by the gadgets.”

Hi-tech or not, new media artists are by now well-practiced in the technique of unraveling a familiar image to expose an occluded, yet equally valid identity. In Distorted Barbie, Napier relied on a repeated process of digital degradation to blur both the literal and conceptual fiction of the Mattel franchise. Another early project stolen, took the female body apart, presenting attraction as database. Years later these kind of approaches, pixel manipulations and indexing without comment, as well as parsing and remixing have become a sort of standard operating procedure in new media. So much so that as technique becomes more well-known and more accessible, it can be hard to tell one work from another or one artist from the next. With this in mind’ it seems important to note that in the case of Venus 2.0 it is not so much a choice of subject or an organizational scheme that guarantees the final effect, but the manner in which Napier investigates the image and the ways in which Napier illustrates and manipulates both the visual elements of portraiture and his relationship to the figure involved.

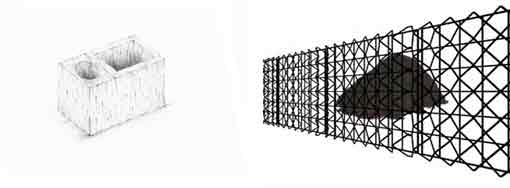

Napier builds and destructs, assembles and tears apart, but in doing so tries his best to keep us focused on these activities as processes. At times Pam’s contortions are allowed to expose the wireframe which allegedly guides her construction and at certain key points on the interface, there is also a steady stream of vector coordinates to embody the idea of data. But Napier makes less of technology than another artist might by effacing what some would tend to elaborate on, in order to draw our attention elsewhere – usually towards evolution, gradation and the ways in which images evolve, and by extension the ideas that inspire those images which reflect how unstable elements are, even treacherous:

“I work at probabilities: what is the likelihood that the figure will be totally opaque? How often does it get murky and undefined? How often should I let that happen and for how long? How often does the figure jump? How long till the figure lands and stands up again? How much time is spent in chaotic motion and how much in stillness? How often does something completely messy happen? Like the figure gets tangled up in a ball that has no structure. I don’t know how the piece will play out each minute, but I know what kind of situations will arise in the piece. I can plan those likelihood, and then let the piece play and see what it does.”

So, like the woman who inspired her. Pam Standing is beautiful, but more unsettling. What makes Pamela Anderson the most frequently mentioned woman on the Internet? Why do we mention her? What is it we want when we give our gaze to celebrity? What has celebrity done to attract us? Whatever your answers, what Napier privileges in his response is not a fixed portrait of a star, but a cloud of iteration that produces its own image and reproduces that image, jangled, confused and full of surprises. A portrait whose finest moments are accidental and whose design is an accumulation of fragments that tense and dissolve, floating like clouds one instant and then sinking like lead the next. This is where the imagination takes a step forward and Napier the artist or Napier the geek becomes Napier the puppetmaster, a networked Dr. Coppelious:

“My favorite moment with the PAM series was when I finally got all the math to work so that the body part images displayed correctly and the correct side of the body showed at the right time and the stick figure suddenly started to look like a ‘real’ puppet that was starting to come alive in the golem-esque way that I thought it could when I was sketching out the idea. I had that Dr. Frankenstein moment: ‘She’s aliiiiiiiiiive!!!!!!!!!!!!!’ which was really the point all along, to create this virtual golem that is clearly not alive at all and yet teases us all with this false appearance of life. Venus 2.0.”

Until the layers of arms, legs, breasts and hips collapse in on themselves and Pam is back where she started, a manipulated beauty unable to escape presentation as a collaged monstrosity.

Note: Mark Napier has been creating network art since 1995. One of the earliest artists to deal thematically and formally with the Internet, Napier has been commissioned to create net art by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. His work has appeared at the Centre Pompidou in Paris’ P.S.1 New York’ the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis’ Ars Electronica in Linz’ The Kitchen’ Kunstlerhaus Vienna’ ZKM Karlsruhe’ Transmediale’ iMAL Brussels’ Eyebeam’ the Princeton Art Museum’ la Villette’ Paris’ and at the DAM Gallery in Berlin.

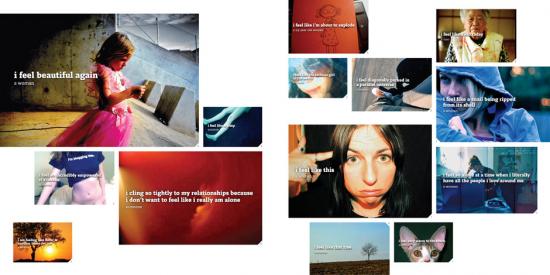

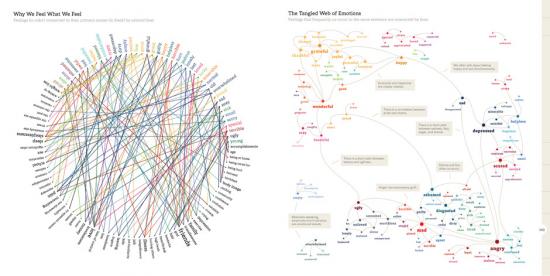

Featured image: Annie Abrahams creates an Internet of feeling – of agitation, collusion, ardour and apprehension.

This essay accompanies If not you not me, an exhibition of networked performance art by Annie Abrahams at HTTP Gallery in London. Where social networking sites make us think of communication as clean and transparent, Abrahams creates an Internet of feeling – of agitation, collusion, ardour and apprehension. This exhibition presents three new collaborative works alongside documentation of recent networked performances created and curated by the artist.

2002. My expectations and behaviour have been shaped by years of work and play at my personal computer. I have habitually ignored my hunched body whilst my attention is projected through key-stroke and mouse click into a social space made of people, digital technologies and the cables, hubs and protocols of the global network.

separation/séparation: A click on a blank web page, displayed in a tall, thin browser window, is like a poke at the body of a sleeping animal. “Do something then!” On the first two clicks, the words “lonely soul” appear in a standard font at the top of the screen. More clicking calls up the following words “…not knowing how to differentiate between you and me, you don’t feel my pain…” Accelerated mouse taps provoke an imperious message on a new screen. “You don’t have the right attitude in front of your computer, either you clic (sic) too fast or with too much force…” With more measured interaction I am allowed to continue with the soliloquy, interspersed with instructions drawn from Workpace, an exercise programme used to assist in the recovery and prevention of Repetitive Strain Injury. The first illustrates a facial work-out. An animated download bar sets the duration of the exercise. I wrangle with the regimen to find a way to skip the prescribed exercises, to get to the end of the story. Finally I comply, performing the therapeutic stretches by the light of my machine. In my imagination other viewers/participants, located around the world in their various domestic settings, are roused from their physical inertia, illuminated by their PCs, in animated, undulating fleshy frills at the edges of the Internet. Returning to the screen for the next chapter, one gentle click at a time, a story of unrequited love unfolds; between an implacable machine and a human-being laid low by their own computer-inspired dreams of control and unlimited power.

This is the first time that my body has been directly addressed, indeed disciplined, by a Net Art work. This is made possible by its complex composition. separation/séparation is made of many parts: a web interface, an economical visual aesthetic, texts (the monologue, the instructions, the commands), human-to-machine interaction. Most of these ingredients are also active in the real-time installations and documentary videos exhibited seven years later in If not you not me at HTTP Gallery. The addition of human-to-human interaction, physical space and objects produces ever more complexity in the structure of the work. However while its many different parts often remain visible, separate and present for the viewer/participant, the effect is not one of disconnected components. Abrahams continues to connect them with the sociality of viewers/participants, generating powerful, singular, artistic affects. More recently her favoured vehicle for artistic exploration is collaboration without which there is no relationship: no me, no you, no other and therefore no artwork. If not you not me asks visitors to explore how relations constitute identity and consider the corporeal implications of an emerging human sociality mediated by complex digital networks.

In 2007 One the Puppet of the Other/ L’un la poupée de L’autre explored the experience of solitude on the Internet while straddling both physical and virtual public space. In this collaborative telematic performance at the Pompidou Centre, Paris, Abrahams and co-author Nicolas Frespech each sat in an igloo tents on stage. Their shadows could be seen moving about within, and who communicated via a system of webcams and microphones. They improvised according to a simple rule where each had to respond to the other’s instructions – “sing a song” or “say something sweet” – to make each the living doll or avatar of the other. The webcam images and amplified conversations were streamed into the auditorium and displayed on a simple double screen projection above the tents. The hazy, flesh-tones of the webcam images had a unifying effect giving the impression of a shared dream. At the same time their physical proximity on stage reemphasised the way in which they were separated by their attempts to control and resist each other as they chose whether or not, as Abrahams writes, “to give flesh to the projections of the other.”

The artists collaborated to negotiate the co-evolution of both a relationship and a performance. This was the first of Abrahams’s networked performances that scrutinised real-time intersubjectivity. More recent works in this area include The Big Kiss with Mark River and Double Blind (Love) co-authored with Curt Cloninger. Distinct from pointing and clicking to control a machine or a game, performers adopt the more complex and subtle rituals and tuning-in techniques of improvising musicians and lovers. This requires them to acknowledge the similarities and differences in the nature of the sentient-other and to accept the other’s autonomy. Unlike Paul Sermon’s reassuring installations such as Telematic Dreaming that invite participants to cooperate within familiar and intimate domestic spaces connected by videostreams, Abrahams’s stark interfaces amplify the performers’ awareness of their solitude. They are alone in their physical space and yet they are responsible for co-constructing an image or a soundscape to express their experience of a relationship with a distant other. The unexpected result for the viewing public can be a disconcerting impression of intense intimacy. Viewers (as voyeurs) witness the emergence of boundaries as they are made and remade in the co-creation of the performance – each piece is a dynamic double portrait of every negotiation, every partnership.

Abrahams’s fascination with collaboration and participation means that she has a strongly developed sense of the context for artwork (not uncommon with artists who work with the Internet – think Jess Loseby’s Digital Kitchen, Andy Deck’s Panel Junction, Avatar Body Collision’s Upstage). She understands the many subtle ways in which curatorial and technical infrastructures impact on the meaning of the work and others’ experience of it. She knows that in order to best familiarise herself with the mechanics and affects of collaboration she has to move through all positions from initiator and director, to participant, to viewer. Her two series of curated performances Breaking Solitude and Double Bind (which she created with technical partner Clement Charmet and Panoplie.org) are remarkable in that they demonstrate the power of a simple interface, a curatorial frame and an extended community of artists experimenting across networks. Breaking Solitude was simply set up as “Web-meetings of about twenty minutes long using chat and streaming to experiment (sic) new ways of being together.” For Double Bind Abrahams creates a more focused context based in her own earlier experiences as a biologist, where she came across the concept of the Double Bind; “a situation with no exit, whatever one chooses one looses [which] leads to illogical, inhibited, ambivalent and misplaced behaviour. Double bind is the result of conflicting cues about a particular situation. An animal that cannot decide between attack and flight is going to eat or scratch.” For this series she asked six artists to reflect on whether double bind describes our relation to technology, within a double webcam performance which could be viewed online and commentated on by up to thirty visitors within a simple message window. Abraham asks: “Is our relation to the computer and internet double bind, bound, bond?…Remote presence, ubiquity, multiple personality, absence of the body? Does this make us schizophrenic? How do we adapt?”

We are unaccustomed to experiencing either art or online social interaction in this way. Most artworks do not require us to participate with so many aspects of ourselves. Most social media interfaces are designed to smooth out the disconcerting glitches and vacuums created by the inevitable interruptions in data-flow. They aim at transparency to give an impression of irrepressible and unproblematic social exchange – as if the last thing we should be aware of when “using” technology is its impact on our physical and psychological well-being. On the one hand this transparency creates an exciting speed of exchange and a froth of production. On the other, however, the bandwidth of our communication is eroded and along with it the range of things that might be conveyed and relations evolved. If it can’t be said in 140 characters, it can’t be said. A voice disappears – no-one notices; the babbling stream of confabulation bypasses, drowns out – bleaches out – absences and depressions. With these ubiquitous interfaces we interact less with other people than with the social utility itself and with our ideas of ourselves.

Abrahams’s work always invites us to acknowledge, feel and imagine in our interactions the many aspects of the machine and the other human being speaking through it. Her current artistic research project Huis Clos / No Exit directly addresses how each person will react in a context of collaboration, at the same time as studying its technical and formal limits and possibilities. Her work’s place in the proliferating network of machines and human-beings (their emotions, desires, even their hormones) makes us aware of the artwork’s simultaneous openness and resistance to our contribution. It encourages us to bring our whole selves to the question of the part we play in the co-evolution of future relations.

Annie Abrahams was born to a farming family in a rural village in the Netherlands. She obtained a doctorate in biology in 1978 and found that her observations of monkeys inspired curiosity about human interactions. After leaving an academic post, she trained as an artist and moved to France, where she became interested in using computers to construct and document her painting installations. She began experimenting with networked performance and making art for the Internet in the mid 1990s. Her work has since returned to the questions raised by the monkeys, concentrating on the possibilities and limitations of communication on the Internet. She has performed and shown work extensively in France, including at the Pompidou Centre, Paris, and in many international galleries including among others Espai d’Art Contemporani de Castello, Spain; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo; and the Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art, Yerevan; festivals such as the Moscow Film Festival and the International Film Festival of Rotterdam, and on online platforms such as Rhizome.org and Turbulence.

Data Soliloquies

Richard Hamblyn and Martin John Callanan

London: Slade Press, 2009

112 pages

ISBN 978-0903305044

Featured image: Data Soliloquies is a book about the extraordinary cultural fluidity of scientific data

Although much has been said about C.P. Snow’s concept of a “third culture”, we haven’t actually reached an understanding between the spheres of science and humanities. This is caused in part by the high degree of specialisation in each field, which usually prevents researchers from considering different perspectives, as well as the controversies that have arisen between academics, exemplified by publications such as Intellectual Impostures (1998) in which physicists Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont criticise the “abuse” of scientific terminology by sociologists and philosophers. Yet there is a growing mutual dependency of both fields of knowledge, as the one hand our society is facing new problems and questions for which the sciences have adequate answers and on the other scientific research can no longer remain isolated from society. Some scientists, such as the astronomer Roger Frank Malina, have even argued that a “better science” will result from the interaction between art, science and technology. Malina presents as an example the “success of the artist in residence and art-science collaboration programs currently being established” [1], and considers the possibility of a “scientist in residence” program in art labs.

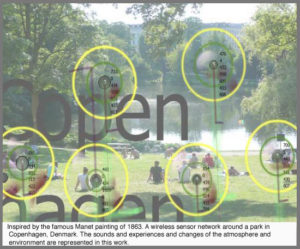

Our relationship with the environment is certainly one of the main problems we are going to face during this century and it is also a subject that brings up the necessary communication between science and society. The UCL Environment Institute [2] was established in 2003 to promote an interdisciplinary approach to environmental research and make it available to a wider audience. While being representative of almost every discipline in the University College London, it lacked an interaction with the arts and humanities. This gap has been bridged by establishing an artist and writer residency program in collaboration with the Slade School of Fine Arts and the English Department. Among 100 applications, writer Richard Hamblyn and artist Martin John Callanan were chosen for the 2008-2009 academic year: Data Soliloquies is the result of their work.

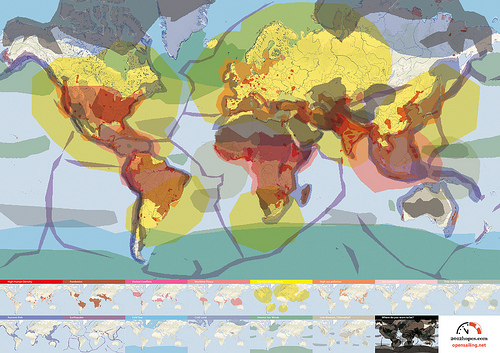

Despite “belonging” to the field of art and humanities, neither Hamblyn nor Callanan are strangers to science and technology. Richard Hamblyn is an environmental writer and historian who has developed a particular interest in clouds, and Martin John Callanan is an artist whose remarkably conceptual work merges art and different types of media. This may be the cause that Data Soliloquies is by no means a shy penetration into a foreign field of knowledge but a solid discourse which presents a richly documented critique of the apparently ineffective ways in which scientists have made society aware of such a crucial problem as that of climate change. The title of the book has been borrowed for a term that Jon Adams, researcher at the London School of Economics, coined to refer to Michael Crichton’s novels, who uses “scientific” facts to give his imaginative plots an aura of credibility. With this reference, the authors state that the way scientific data is presented actually constitutes a narrative, an uncontested monologue: “…scientific graphs and images have powerful stories to tell, carrying much in the way of overt and implied narrative content (…) these stories are rarely interrupted or interrogated.”[3]

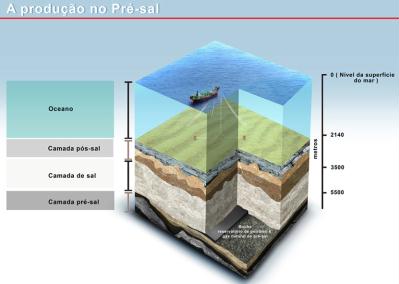

As the amount of data regularly stored in all sorts of digital supports increases exponentially, and new forms of data visualisation are developed, these “data monologues” become ubiquitous, while remaining unquestioned. In his text, Hamblyn exposes the inexactitude in some popular visualisations of scientific data, which have set aside accuracy in favour of providing a more eloquent image of what the gathered evidences are supposed to tell. On the one hand, Charles D. Keeling’s upward trending graph of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration, which according to Hamblyn is “probably the most important data set in environmental science, and has become something of a freestanding scientific icon”[4], or Michael Mann’s controversial “Hockey Stick” graph are illustrative examples of the way in which information displays have developed their own narratives. On the other, the manipulation of data in order to obtain a more visually effective presentation, such as NASA’s exaggeration of scale in their images of the landscape of Venus or the use of false colours in the reproductions of satellite images, call for a questioning of the supposed objectivity in the information provided by scientific institutions.

In the field of climate science, the stories that graphs and other visualisations can tell have become of great importance, as human activity has a direct impact on global warming, but this relation of cause and effect cannot be easily determined. As Hamblyn states: “climate change is the first major environmental crisis in which the experts appear more alarmed than the public” [5]. The catastrophism with which environmental issues are presented to the public generate a feeling of impotence, and thus any action that an individual can undertake seems ineffective. The quick and resolute reaction of both the population and the governments in the case of the “ozone hole” in 1985 points in the direction of finding a clear and compelling image of the effects of climate change. As Hamblyn underscores, this is not only a subject for engineers: “the reality of ongoing climate change has yet to be embraced as a stimulus to creativity –in the arts as well as the sciences– or as a permanent and inescapable part of human societal development” [6].

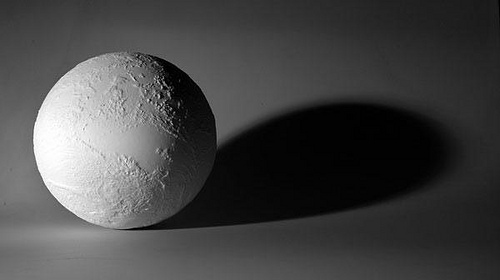

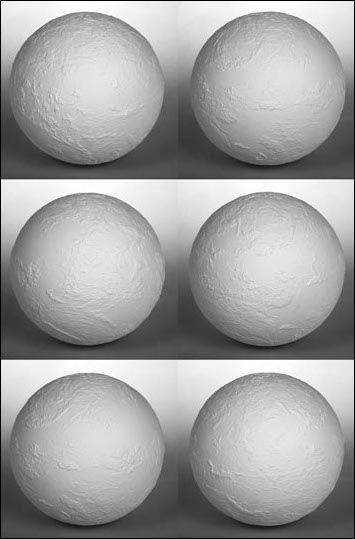

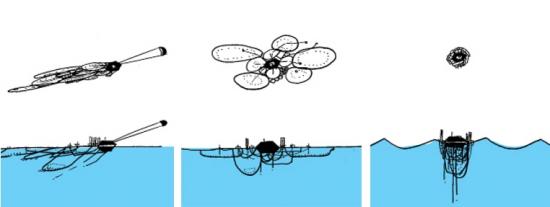

Martin John Callanan took upon himself to develop a creative response to this issue, and has done so, not simply by creating images or objects but by depicting processes. He states: “I’m more interested in systems –systems that define how we live our lives” [6]. A quick look at his previous work [7] will show how appropriate this statement is: he has visited each and every station of the London underground, collected every command of the Photoshop application in his computer, officially changed his name (to the same he already had), gathered the front page of hundreds of newspapers from around the world and engaged himself in many other activities that are as systematic and mechanical as ironic, poetic or simply nihilistic. During his residency, Callanan created to main projects. The first one, Planetary Order, is a globe in which the patterns of the clouds on a particular date (February 6th, 2009) have been sculpted. The artist composed the readings of NASA’s cloud monitoring satellites in a virtual 3D computer model, which was then laser melted on a compacted nylon powder sphere at the Digital Manufacturing Centre at the UCL Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment. The resulting object is a sculpture, an artwork more than any sort of model in the sense that it develops a discourse beyond the actual presentation of data. An impeccable white sphere textured by its subtle protuberances, the globe evokes the perfection of an ancient marble sculpture while presenting us with an uncommon view of the Earth, covered with clouds. The clouds, which are usually erased in the depictions of our planet in order to let us see the shapes of the continents (the land which is our dominion), become an icon of climate change and the image of an order which is, in all senses, above us. Callanan freezes the planetary order of clouds in an impossible map, a metaphorical object which appears to us as a faultless, yet fragile and inscrutable machine.

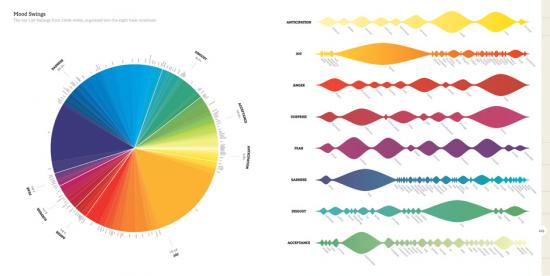

The second of Callanan’s artistic projects is the series Text Trends. Using Google data, the artist has collected the number of searches for selected terms related to climate change in a time range of several years (from 2004 to 2007-2008). With this data, he has generated a series of minimalistic graphs in which two jagged lines, one red and the other blue, cross the page describing the frequency of searches (or popularity) for two competing terms. The result resembles an electrocardiogram in which we can see the “life” of a particular word, as opposed to another, in a simple but eloquent dialogue of abstract forms. Callanan has chosen to confront terms in pairs such as “summer vs. winter”, “climate change vs. war on terror” or “global warming”. Simple as they may seem, the graphs are telling and constitute and visual summary of the book whilst suggesting many other reflections. The final conclusion is presented in the last graph, in which the perception of climate change is expressively described by the image of a vibrant line for the word “now”, much higher in the chart than the flat line for the word “later”.

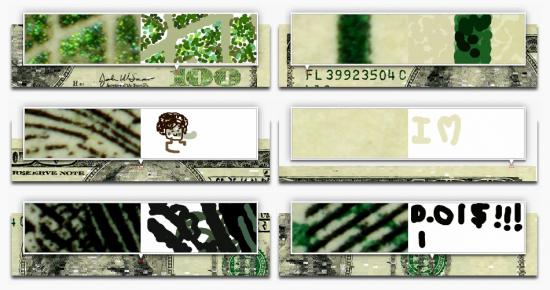

Pau Waelder

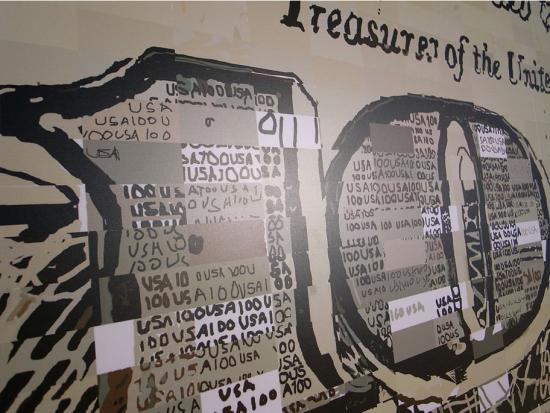

Arriving at the homepage of Ten Thousand Cents, an Internet artwork by Aaron Koblin and Takashi Kawashima, a mottled image of a one hundred dollar bill slowly fades into view. Ben Franklin looks out sedately. Mousing over the large image, the cursor is replaced with a small red rectangle. And here lays the beauty of the project; with the click of each rectangle, a zoomed in portion of the one hundred dollar bill is revealed. On the left side is a high-resolution photograph of that tiny portion of the bill. On the right side, a real-time moving image plays, revealing how the image was drawn by a human hand in a drawing program created by Koblin and Kawashima. There are, in fact, 10,000 such rectangles and each was created by a Turker through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk marketplace.

Over the course of five months (from November 2007 to March 2008) Koblin and Kawashima posted tasks, known as HITs, Human Intelligence Tasks, on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk site. Having broken down an image of a one hundred dollar bill into 10,000 sections, Turkers were tasked with redrawing their assigned section. Each Turker was paid $.01 for the task, making the total payment of drawing a one hundred dollar bill one hundred dollars. (Prints of the project can also be bought for one hundred dollars. All proceeds are donated to the One Laptop per Child (OLPC) project) Each Turker worked anonymously, unaware that what they were drawing was a section of a bill or that their work would eventually be combined with other Turkers’ work to create an art project. The variability is endless. Some Turkers methodically draw in the lines and painstakingly shade in boxes. Some quickly slash the paint tool across the page; one imagines they felt they had better things to do with their time. Some are cheeky, using the space for digital graffiti or messages like “I love U.” Most copy the image exactly. Yet, with the differing movements and tempos, every one suggests a different story and different person behind the tool. I suggest you take a few minutes and watch the unfolding scenes. They are oddly, satisfyingly banal and beautiful.

The project and its presentation on the website are undoubtedly elegant. Yet, the conceptual work behind the piece is a bit murkier. The project description states, “The project explores the circumstances we live in, a new and uncharted combination of digital labor markets, ‘crowdsourcing,’ ‘virtual economies,’ and digital reproduction.” Big and important themes. What are the implications of crowd-sourcing for creative work? For any kind of paid work? Where is the distinction between work and play? Creativity and re-presentation? In this deeply networked age, what are the evolving relations between individual and collective action?

The Mechanical Turk, made by Wolfgang de Kempelen in 1769, caused a sensation in 18th and 19th century Europe, first for its existence as a seemingly intelligent chess playing automaton – one who could beat Ben Franklin and even Napoleon in chess – and subsequently, for being an infamous hoax. Inside of the automaton was in fact a man, a skilled chess player. The Mechanical Turk was no thinking machine. It was an elaborate performance of concealment and human skill.

In 2005, in an ironic (and some might say distasteful) turn of events, Jeff Bezos of Amazon named a new business venture, Amazon Mechanical Turk. The idea was to make a digital marketplace that capitalized on the unique intelligence of human agents. Broken down into microtasks, known as HITs, Mechanical Turk provides a means to accomplish those tasks that humans can do quickly but which would take computers much longer to do, for instance, tagging images, taking surveys or transcribing audio recordings. This Mechanical Turk is also a performance of human skill, one that revels in its basis in human intelligence – Bezos calls it “artificial artificial intelligence” – but one that also operates within a mode of concealment and indeed, alienation.

As Katharine Mieszkowski of Salon wrote about Mechanical Turk in 2006, “There is something a little disturbing about a billionaire like Bezos dreaming up new ways to get ordinary folk to do work for him for pennies.” Critics of Mechanical Turk abound, and their objections point to the insidious labor relations that Mechanical Turk enforces, implying that Mechanical Turk approaches a virtual sweatshop. The system was designed for employers, not employees. The earnings of Turkers fall within a gray area of digital labor, officially being classified as contractor work, subject to high self-employment taxes and no option for benefits. Although a rating system protects employers, in so far as employers can choose to reject a work offer from a Turker or refuse to pay a Turker if the work is completed unsatisfactorily, no such system protects Turkers. As advocates of a Turker Bill of Rights have pointed out, there is no effective outlet within Mechanical Turk for Turkers to voice grievances against employers. What does exist is a vibrant community forum, Turker Nation, where Turkers advise each other on known scammers.

Moreover, although anecdotally Mechanical Turk is understood as more game or past-time than employment, a recent study out of University of California, Irvine’s Informatics Department points out that almost a third of Turkers rely on Mechanical Turk as a source of income. Another study found that nearly half of Turkers report their motivation for working as income related. For this population of Turkers, it is troubling to consider the possibilities of exploitation and unfair labor practices.

In this light, I find the artists’ neat appropriation of the mechanisms of Mechanical Turk unsettling. The implications and the stakes of Mechanical Turk as an economic system are left untouched. And considering that the artists chose to create a representation of money and employ Turkers, these dimensions of economy and labor are present but disappointingly unaddressed.

Yet, the moments in the project that remain in my mind’s eye like lovely specters as I glance at the dollar bill that I traded for coffee this morning, are the movements of the individuals who drew each section. On this level, the project is like a fantastic cabinet in which each drawer opens onto a new wonder. Perhaps what Ten Thousand Cents effectively offers is not a statement about labor politics or late capitalism’s continuing ability to provide structures for domination and exploitation. Perhaps Ten Thousand Cents asks us to take a different step toward understanding “the circumstances we live in,” revealing the endless variability of individual expression. In this networked age, we often act collectively, that is, together, parallel, most often without knowledge of the larger directions toward which our actions will lead. Collaboration, laboring together, is notion whose meaning is expanding and changing in the 21st century. What remains, even among protocols and code, is individuality. Though we are subsumed by larger structures, we do have spaces for self-expression and self-formulation. Leave an exploration of the limits of these spaces to others – and I surely believe we must consider the limitations. Yet we must also explore and value the spaces of possibility and the domains where we are active agents. We are called to remember that every artifact is irreducible to its mere instance in the world – it is a sum of processes and individual actions.