The Princess Murderer by Geniwate and Deena Larsen

The Free Culture Game by Molleindustria

The Marriage by Rod Humble

Samorost 2 by Amanita Design

The Graveyard by Tale of Tales

Gravitation by Jason Rohrer

discussed by Edward Picot

This article is co-published by Furtherfield and The Hyperliterature Exchange.

Computer games enjoy a special position in the canon of new media art. One of the most distinctive features of new media is its interactivity, and because computer games are inherently interactive they have always attracted a good deal of attention from new media theoreticians. They seem to offer the opportunity to create artforms which are participative rather than dictatorial in structure, and thus to redefine the relationship between artist and audience. No longer will audience-members simply act as passive recipients of whatever the artist chooses to put in front of them: instead, through their interactivity, they will become co-creators.

Oddly enough this line of thought has been particularly important in the field of hyperliterature. This is partly for historical reasons: in the 1970s and 1980s home computers had little or no graphics capabilities, and an adventure-game interface entirely based on text and imagination was a good way of sidestepping the problem. Early “interactive fiction”, as it became known, derived a good deal of its inspiration and functionality from the hugely-popular dice-and-rulebook role-playing games of the 1970s, notably Dungeons and Dragons – which in turn derived their inspiration largely from Adult Fantasy or Sword and Sorcery novels. Computerised role-playing games, therefore, were literary in style not only because they were initially text-based, but because they had a literary ancestry – and this ancestry remained very much in evidence at least up until Myst, initially released in 1993, which was the biggest-selling PC game of all time until The Sims replaced it in 2002.

The interactive fiction genre was also associated with hyperliterature because it reached its creative peak in the 1980s, at the same time as hypertext fiction was coming into existence via Hypercard (a system of interlinked hypertext pages, created prior to the Web itself, which was pre-installed on Mac computers from 1987 onwards). The students and young academics, mainly American, who embraced hypertext fiction as a new literary form were often quick to embrace interactive fiction too, and it has remained a cornerstone of hyperliterary theory in the USA ever since. The New Media Reader (2003), edited by Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort, included not only a good deal of discussion of early computer games, but a CD with emulations of “Spacewar!”, “Missile Command”, “Adventure”, and “Karateka”. Likewise, Volume One of the Electronic Literature Collection (http://collection.eliterature.org/) (2006) included a number of interactive fictions: “All Roads”, “Whom the Telling Changed”, “Bad Machine”, “Galatea” and “Savoir-Faire”.

The insistence on interactivity as an important element of hyperliterature – and on computerised role-playing games as a paradigm of interactive art – has always begged a number of questions, however. First of all, champions of “traditional” literature are inclined to argue that new media theorists are starting from an incorrect model of the relationship between author and reader. Readers do not receive text “passively” – they interpret it, and many modern(ist) texts, far from spoon-feeding their readers with predigested messages, are deliberately written in fragmented, ambiguous or enigmatic ways so as to oblige the audience to make interpretations. If this is granted, then the claim that interactive fiction is “liberating” its readers by re-defining their relationship with its authors begins to look simplistic.

Furthermore, some new media practitioners themselves have come to the conclusion that far from setting the audience free, involving them in a game rather than simply giving them text to read is trading one form of control for another. Geniwate and Deena Larsen, for example, writing in about their piece The Princess Murderer in 2003, commented that they “wanted to create this frustration of power and powerlessness as a response to early hypertext works that placed readers as coauthor…” (http://tracearchive.ntu.ac.uk/review/index.cfm?article=76). The work – pointedly subtitled “No Exit” – deliberately uses interactivity as a means of entrapping readers or viewers rather than liberating them.

But the fundamental question, which haunts all attempts to create art from computer games, is whether it is really possible to reconcile the two. It could be argued that art requires a different kind of concentration from a game, and uses a different part of the mind – and that the more intensely you play a game, the less inclined you will be to pay attention to any artistic qualities it may possess.

The Princess Murderer exemplifies the problem. It isn’t by any means a fully-fledged computer game, but a hyperfiction which incorporates a number of game-style design elements. It’s cleverly-conceived and well-written, but its Achilles’ heel is the fact that the more you engage with its game-playing aspects – basically, clicking rapidly from one “page” to another in order to change the scores displayed at the bottom of the screen – the more difficult it becomes to pay attention to its literary content.

Another more recent example of the same difficulty is the Free Culture Game (2008), from Italian collective Molleindustria. This game bills itself as “playable theory”, and as the introductory screens explain it illustrates the conflict between the market, where “knowledge is commodified and sold”, and “the common”, where “knowledge is cooperatively created and shared”. The common is a white circle in the middle of the screen, inhabited by a number of green stick-men with lightbulbs popping out of their heads. Round the outside of the white circle prowls “the vectorialist”, a rapacious copyright symbol which magnetises and gobbles up the lightbulbs unless you, the player, can guide them back towards the green men with your cursor. If the vectorialist gobbles up all the lightbulbs, the green men turn grey and stop producing new ones. Again, it’s a nice piece of design, but the first problem is that its meaning is too thoroughly explained in the introductory screens – the vectorialist’s aim is to “copyright ideas and create scarcity in the common”, and “people who can’t access knowledge in the common will stop producing new ideas and turn into passive consumers”. The game itself merely illustrates these statements without developing them. On the other hand, once you start to play, you quickly become absorbed by the slightly-irritating challenge of trying to keep ideas away from the vectorialist, and the trickiness of this task distracts you from the meaning of the game, instead of reinforcing it.

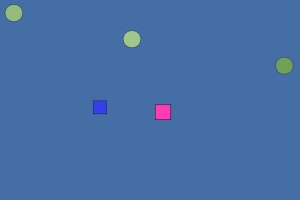

The same problem even haunts Rod Humble’s celebrated computer art-game The Marriage (2006). Humble, according to Wikipedia, “is the executive producer for the Sims division of the video game company Electronic Arts since 2004. He has been contributing to the development of games since 1990, and is best known for his work on the Electronic Arts titles, The Sims 2 and The Sims 3.” The Marriage has been widely written up and generally well received within the gaming community. It starts with a blue square and a pink square floating towards each other until they “kiss” – whereupon the blue square gets smaller and fainter, while the pink one gets larger and more distinct. Through the screen fall a number of coloured circles. Contact with these circles makes the squares larger, unless the circle is black, in which case it makes them smaller. Over time the pink square fades, and can only be made distinct again by contact with the blue one – but this contact makes the blue square smaller and fainter. If either square becomes too small or indistinct, the game will be over. You can make them float towards each other by mousing over them – and the trick is to allow them to drift apart until they have “eaten” some of the circles, and thus enlarged themselves, but to bring them back for a “kiss” in time to prevent the pink square from disappearing. If you can manage to keep this going, then as the game progresses the screen-background will go through a number of colour changes, from blue to purple to green to pink and eventually to black – and your couple will then disintegrate in a firework-display of tiny pink and blue squares, which is the closest you get to “winning”.

The main thing which makes us regard this game as a work of art is its title, The Marriage. If it was called “Keep the Squares Alive” it would probably never occur to us to search for meanings in the game rather than just playing it; but because of the title, we immediately identify the blue square as male, the pink as female, and their drifting-together as the start of a relationship. As a knock-on effect, we feel inclined to interpret all the other game-elements symbolically as well – the falling circles are life-events, the black circles are bad things happening, the differently-coloured screen-backgrounds represent different stages of the marriage, and so forth. The directness with which The Marriage presents itself to us and demands this effort of interpretation is undeniably poetic in its effect – but there are problems. The first one is that the colours blue and pink, although they enable us to identify one square as male and the other as female, suggest a rather stereotypical view of the sexes, and various other aspects of the game seem questionable in the same way. Why does the blue square get larger and better-defined as it drifts around colliding with circles, whereas the pink square gets larger to a lesser degree, and keeps fading? Why can the pink square only become well-defined again by re-colliding with the blue, and why does this contact make pink larger and blue smaller? But the second problem is the familiar one: after you have played the game for a while, you stop thinking about what the various symbols on-screen represent, and just want to keep the squares going for as long as possible. The artistic meaning of the game fades into the background, and the activity of playing it takes over.

Despite these flaws, The Marriage undeniably has an artistic impact. Humble himself has written an extremely suggestive article about the artistic potential of games – “Game Rules as Art”, published in The Escapist in April 2006. In this article he argues that

…the rules of a game can give an artistic statement independent of its other components.

– and as an example of what he means, he cites (amongst others) Snakes and Ladders:

As a lesson about life’s nature, Snakes and Ladders is interesting work: Firstly, it is entirely luck based, and secondly, no matter how well someone appears to be doing, there is always a chance he will land on a snake… and be whisked back down the board.

So far so convincing, but Humble is on less certain ground when he argues that the power of game-rules derives from childhood psychology:

I believe that childhood play is about practising within the rules designed for adulthood, testing them out in a pretend world first. Later on, grownups deconstruct literature or art for rules (and the ways they have been tested) in a similar fashion.

This seems rather a simplistic view, both of childhood play and its purposes, and of grownup attitudes towards literature and art. Humble would like to establish rules as the common denominator between games and art, but although some types of creative work are undoubtedly rule-governed – a sonnet, a fugue, a lumiere video or an Oulipo project, for example – the rules in these cases differ from game-rules, in that they affect the artists and their endeavours, rather than the audience and their interactions; and it remains far from clear whether rules are a defining characteristic of the arts right across the spectrum. But Humble goes on to categorise different types of game in terms of whether their rules are created in advance or on-the-fly, suggesting that there are four categories:

1. Rules are created in advance, and fully understood by the players as they play (eg. Snakes and Ladders)

2. Rules are created in advance, but too complex to be remembered, and therefore a book or umpire is required to clarify them during play (eg. Dungeons and Dragons)

3. Rules are created in advance, but modified during play (eg. “professional military umpired war games”)

4. Rules are created when the game starts, and modified during play (“This type includes children’s play or make believe”)

It is in the fourth of these categories that Humble’s over-emphasis on rules becomes problematic. “Children’s play or make believe” is not necessarily rule-governed at all. To a child, the phrase “Let’s play!” means something different from “Let’s play a game!” The second phrase means “Let’s play a game with predefined rules”, whereas the first means “Let’s have fun”, and may involve rules or may not. When my brother was six or seven years old, his favourite pastime was digging holes in the back garden. Rules were imposed on him – “Don’t you dig up my flowerbeds!” – but these were nothing to do with his enjoyment of the activity. Nor was it in any direct way a preparation for adult life. Was digging holes a game? Not by any normal definition. Was it play? Certainly. Running and jumping, make-pretend, pulling faces, standing on one leg, skipping, singing, painting and playing Monopoly are all types of play, but not all of them are games, because not all of them have rules. In other words, games – recreational activities defined by their rules – are a subset of play; and play is a spectrum of behaviour which also includes the arts (such as painting and make-pretend).

Humble’s attempt to create a link between games and art by suggesting that both activities are rule-governed is ultimately unconvincing. But this is not to say that there cannot be common ground between the two, or to deny that – as in the Snakes and Ladders example – rules can sometimes convey meaning. And where Humble’s analysis is really useful is that it allows him to see through what most people regard as the most important aspects of computer games – “representation systems” and “simulation”, as he puts it – to the inner structure. It is this insight which allows him to drastically strip away so many of the computer game’s most familiar gizmos and strategies – the levels, the lives, the point-scoring systems, the sound-effects and most of the visual effects too – in The Marriage, until he arrives at something which combines some of the visual qualities of abstract art with some of the economy of suggestion of a modern poem.

Simplification of format seems to be a common feature amongst the more successful computerised art-games. Samorost 2 (2005), from the Czech company Amanita Design, is another example. It’s basically a puzzle-solving game. A little cartoon man lives on a small planet with a dog and a pear-orchard. The game begins with two aliens landing in a rocket, stealing his pears and abducting his dog. The little man launches his own rocket and sets off in pursuit. The rest of the game takes us through a number of screens as the little man attempts to get his dog back, but finds himself confronted by one difficulty after another. In each screen there is a puzzle which has to be solved before he can make any further progress – in one, for example, he comes to a flooded chamber and has to work out how to drain away the water before he can reach the submerged exit. This is accomplished by pulling a flush mechanism and then turning a stopcock to prevent the water from coming back.

One reason why Samorost 2 works in artistic terms is because it doesn’t hurry us. You can take as much time as you want (or need) working out the puzzle on each screen, which means that your attention isn’t dragged away from the game’s artistic aspects by the need to get on with playing it. And the artistic aspects are well worth noticing. The graphic design is wonderfully quirky, full of textures such as bark, moss and rust which give the Samorost universe a unique identity – small-scale, retro and homely – not at all what you would normally expect from a science-fiction computer game. There are also numerous flashes of humour. At the start of the game, for example, the little man has to bang a dozing robot over the head to make him open an iron gate; in order to do this he has to steal a mallet from a slug-monster; and he obtains the mallet by concocting a potion which makes the slug-monster drunk.

What takes the game one step further into artistic territory, however, is that as the little man reaches the end of his quest we learn why the aliens stole his pears and abducted his dog in the first place. He finds himself in a pear-pickling factory. The aliens, it turns out, serve a hedonistic slug-king addicted to pickled pears, and they have imprisoned the dog in a treadmill (with a sausage just out of reach to keep him running), which drives a fan to keep the slug-king cool. It’s all very light-hearted, but even so it does give us the feeling that in playing Samorost we are doing more than just solving a series of puzzles: we are exploring a world, and unearthing its secrets.

One last aspect of Samorost worth noticing is our relationship with the little man himself. Because he has quite a distinct character of his own, when we play the game we don’t really feel that we are inside him. Again, the pace of the game helps with this effect. When you play a high-pressure game in which, so to speak, you are constantly having to fight or run for your life, there is no room for a sense of separation between yourself and your avatar. In Samorost, on the other hand, there is an odd and persistent sense that it’s the little man himself who is solving the puzzles on each screen – even though it’s really us. In the flooded chamber, we’re the ones who have to work out how to pull the flush and turn the stopcock in order to get rid of the water – yet when we succeed, we feel as if the little man has done it. And this sense of watching a character from the outside as he makes progress through the game is part of what makes Samorost feel more like a story than a conventional computer game.

Interestingly, this sense of separation from the central character is also a feature of Tale of Tales’ 2008 game The Graveyard. In this game, our task as players is simply to guide an old lady along a path through the middle of a cemetery, until she comes to a bench in front of a chapel. When she sits on this bench the game enters a non-interactive sequence, in which a song on the theme of mortality is sung in Flemish, with subtitles. After the song is over we are able to control the old lady again, and our task is to walk her back out of the cemetery, which completes the game. The only variation is that if we pay $5 for the full version, the old lady may die while she is sitting on the bench.

A lot of the discussion about this game has focussed on two questions: firstly whether it’s really a game at all, and secondly whether it would have been just as effective as a short film, given that the middle section is non-interactive, and that your options as a player are strictly limited even when you are supposedly “in control” of the avatar. On the first question, Michael Samyn himself (one of the co-founders of Tale of Tales, the other being Aureia Harvey) responds by attacking the boundary which separates games from art:

We don’t mind calling our work games because we believe that contemporary computer games have already crossed the borders of traditional games. Most of them just don’t realize it yet. They don’t realize that the most interesting aspect of their design is the way in which they express the story: through the environment, the animations, the colour, the lighting, etc… [But] when we talk about “story” … we don’t mean linear plot-based narrative constructions… we refer to the meanings of the game, the content, its theme… With Tale of Tales, we try to develop a new form of interactive entertainment. One that exploits the medium’s capacity of immersion and simulation to tell its story… It is the experience that matters, not the length of the game or the number of levels or enemies or weapons, etcetera. (http://tale-of-tales.com/blog/the-graveyard-post-mortem/)

These remarks also shape an answer to the second question – whether The Graveyard would have been just as effective as a short film. Samyn’s argument is that a computer game possesses qualities of interaction, immersion and simulation which cannot be reproduced in other media, and which make players experience the content of the game quite differently from a film or a written narrative. Interactivity is the key ingredient, but not the only one. In The Graveyard, the three-dimensional environment also plays a very important part. The virtual cemetery through which we guide the old lady is displayed on the screen in two dimensions, but it was created using 3D software, and the sense that we are moving into the cemetery as the old lady walks, rather than looking at a framed picture of it, is central to the feel of the piece. The 3D modelling gives a feeling of perspectives changing all around us as we move. As in Samorost, playing the game is a way of exploring a world: and as in Tale of Tales’ other games, The Endless Forest and (most recently) The Path, this sense is greatly augmented not only by effects of light and shade – clouds passing overhead, turning the environment from sunny to shady and back again – and by the sound-environment – the noise of traffic from outside the cemetery, birds twittering, a dog barking – but also by a sense of what we can’t see: a feeling that the three dimensional structures in the game are blocking our view at times, which implies that there is more in the game-world than we are being shown.

In some respects the game’s most important qualities are negative ones: it makes its statement as much in terms of what it isn’t, and what it doesn’t do, as in terms of what it is and does. It is such a deliberately dialectical and provocative piece, a poke in the eye for “traditional” computer games design, that it’s really no wonder it has provoked howls of outrage from the diehard gaming community. (“The Graveyard… infuriates me. I think it’s a pretentious, ineffective waste of the interactive medium, and I hate it.” – Anthony Burch, http://www.destructoid.com/indie-nation-39-the-graveyard-110611.phtml, July 2008.) It’s a game set in a cemetery; the central character is a decrepit old lady; you can’t make her jump or fly or even walk very fast; there’s no point-scoring, no way of winning, no challenge to be overcome and no skill involved in playing. Furthermore the range of things you can do as a player is so strictly limited that the word “interactive” is almost a misnomer. Almost, but not quite. What nobody seems to have picked up on is that the tension between what we expect to be able to do as computer-game players and what we are allowed to do within The Graveyard is one of the game’s most important messages. The sense of frustration, thwarted expectation and powerlessness is intentional. This is what old age and death are like: you run out of options: all you can do is follow a pre-ordained path. But within this grim message there is a hint of positive philosophy. Life, the game seems to be saying, is not necessarily about doing, achieving and winning: it’s about experiencing. Your aim should not be to overcome the universe in which you find yourself, not to win prizes from it, but to attune yourself to it. Beyond The Graveyard’s critique of “traditional” computer-game design lies a wider critique of our consumerist, achievement-oriented, individualistic society.

In The Graveyard it isn’t just the content of the game which is significant, but the underlying structure: it isn’t just the fact that we recognise the gaming environment as a cemetery and the avatar as a little old lady; it’s also the fact that our options as players are very strictly limited and it’s impossible to make the game go very fast. This use of structure to convey meaning is something which The Graveyard shares with Jason Rohrer’s Gravitation. In Gravitation, your avatar is a pixellated man, who you initially discover standing next to a fireplace, in a small illuminated square surrounded by blackness. If you walk to the left, the square travels with you, and you discover a yellow-haired child with a red ball. The child throws the ball towards you, wanting you to play. If you get underneath the ball and bounce it back towards the child, the child starts to emit love-hearts, the illuminated screen around your avatar expands, and you can see that above the room in which you are playing there is a maze of upper levels. After you have played with the child for a bit, the illuminated area around your avatar expands to its maximum, flames start to come out of the top of your avatar’s head, and by pressing the space-bar you can jump up into the upper levels and explore them. They are full of stars, which tumble down to the bottom as soon as you touch them. After a short while the illuminated square begins to shrink again, and your jumping power declines, which means you have to go back down to the bottom to refresh your powers.

When you get there, you find the child walled in by the stars you have collected, which have turned to blocks of ice with scores on them. You can free the child – and collect your points – by pushing these blocks into the fireplace, where they melt. Then if you play with the child again your powers of inspiration come back, and you can once more leap into the upper levels. You can only do this a couple of times, however, before you find that when you return to the bottom of the game the child has vanished and there is nothing left but the red ball. This is the game’s most intensely emotional moment: the illuminated square has shrunk back to its smallest dimensions, and you find yourself walking your avatar up and down in the dark, in an attempt to discover where the child has got to. The game is time-limited (at eight minutes), but it normally goes on for a while after the child’s disappearance. Furthermore, the illuminated square expands again after a while, and your leaping power comes back – which gives you a chance to reflect on how different the leaping and star-collecting feel when there’s nobody else in the game apart from yourself.

Rohrer describes this as a game “about mania, melancholia, and the creative process”. It’s also, of course, about the relationship between a parent and a child. Playing with your child fills you with inspiration, but in order to pursue your ideas (or, to put it another way, in order to use them as a means of earning points) you have to abandon the child and risk not only disappointing but losing him or her. As in The Graveyard, the limits placed on what you can do as a player are integral to the meaning of the piece – you can only acquire the ability to jump to the upper levels of the game, and thus to score points, by playing with your child; but when you get into the upper levels you can’t see the child any more. Unlike The Graveyard, however, Gravitation has more of the attributes of an orthodox computer-game: point-scoring, a time-limit and an element of skill (jumping from ledge to ledge in the upper levels requires some dexterity). Where the game departs from orthodoxy is that it seems to suggest that point-scoring may be a waste of time, or perhaps even harmful. It doesn’t really get you anywhere – it doesn’t, for example, earn you access to another level – and when you return to the bottom level you will either find that the stars you collected have walled your child into a corner, or that your child has disappeared entirely.

In this way, like The Graveyard, Gravitation seems to be offering a critique of the normal game-playing mindset. If you don’t go into the upper levels at all, you can spend the entire game playing with the child, and the child won’t disappear – but you won’t score any points. Thus you can play the game “safely”, but only by resolutely ignoring much of its potential. As soon as you fully engage with it, and start trying to score points, you gain in one way but lose in another. The effect is one of irony and complexity. Instead of the usual game-playing credo, that winning equates with virtue, Gravitation seems to be suggesting that in life there are no clear-cut winners and losers, only difficult questions with no correct answers.

From these examples there seems little doubt that the answer to the question whether computer games can also be art is yes. It may be possible to object that The Graveyard pushes so far in the direction of art that it ceases to qualify as a game, but this accusation cannot be levelled at The Marriage, Samorost or Gravitation. Furthermore, although there is an ever-present danger that game-play and artistic appreciation may be at odds with one another, these games show that there are various strategies which can be used to get around the difficulty. The first is to use the structure of the game itself for symbolic purposes. The second is to slow the game right down, eliminate time-constraints and do away with the need for players to display skill or dexterity – thus allowing them more freedom to concentrate on the game’s artistic aspects. The third is to create a sense of separation between the player and the game’s central character, so that the unfolding of the game becomes less like a personal challenge and more like the unfolding of a story.

But the most obvious strategy, used by all of these games, is simply to choose an unusual game-scenario and develop it in an unorthodox manner: a marriage, a little man trying to get his dog back from aliens, an old lady visiting a cemetery, or a man getting inspiration by playing with his child. All of these games make us stop and think simply because they are different from what we would normally expect.

According to an article Esquire magazine published about Jason Rohrer in 2008,

Clint Hocking, a designer at Ubisoft best known for Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell, was so blown away by Passage [Rohrer’s previous game] that he made it a focus of his Game Developers Conference talk earlier this year. In front of an audience full of the industry’s most influential game designers, Hocking growled, “Why can’t we make a game that fucking means something? A game that matters? You know?”… Then he put up a slide of another small indie game, the Marriage, coded by Rohrer’s friend Rod Humble. “I think it sucks ass that two guys tinkering away in their spare time have done as much or more to advance the industry this year than the other hundred thousand of us working fifty-hour weeks,” said Hocking. (www.esquire.com)

But the fact that these games are produced by individuals or small teams is significant in itself, of course. It’s far easier for individuals and small teams to come up with something really original than for large organisations working fifty-hour weeks and locked into an industrial cycle of production and mass-marketing. The problem in the past has always been that such small-scale individualistic work has found it difficult to reach an audience: but the Web has changed the laws of the marketplace to some extent; and the Web’s potential for bringing really original work to the attention of interested parties right across the developed world may be the real key to the future development of computer games as art.

copyright – Edward Picot, May 2009

Art and Revolution – Transversal Activism in the Long Twentieth Century

Gerald Raunig

Semiotext(e) 2007

ISBN 1584350466

“Art and Revolution – Transversal Activism in the Long Twentieth Century” by Gerald Raunig is a book that presents and contextualises artists engagement with revolutionary moments over the last one hundred and fifty years. The history of artists’ involvement with the revolutionary movements of the modern era that it presents is compelling for artists looking for something more than the art market. And the theoretical framework that it uses as the context for this history is surprisingly pertinent to the post-credit-crunch new world order.

Starting with a youthful revolutionary called Wagner who after struggling to bring about the revolution in Germany later went on to write the occasional opera, focussing on the Paris Commune and the Bolshevik counter-revolution, then continuing through the Situationists and May ’68 to the anti-globalization movement, Raunig presents the moments in modern history where real artists and real revolution, or at least its potential, have touched. The more recent moments, notably the anti-globalization protests at the G8 summit in Genoa, are less convincing as moments both of revolutionary and artistic potential. But they contrast informatively with the earlier examples.

I have studied both European History and History of Art but within the first few pages Raunig had told me things I had not even suspected about well known cultural figures and tied their activities into a critical framework that added to understanding of their activities rather than judging them as simple failures to live up to an imagined revolutionary ideal. Raunig does use the language and concepts of contemporary academic Marxist criticism but this is standard for current art writing and the history he presents is explicated rather than obscured by the social and political historical context that this provides.

Raunig neither romanticises nor dismisses the very real achievements and failings of artists caught up in the revolutionary moments of what he calls the long Twentieth Century. When art and revolution meet the result can be folly, careerism, empty gestures, cowardly complicity or false dawns. But there are moments where artists have helped to make the new social order not just concrete and visible. Iconoclasm such as Courbet’s tearing down of the Vendome Column in the Paris Commune, and iconography such as Stalinism’s Socialist Realism have both played their very real and very effective part in destroying old political and social orders and introducing new ones.

“Transversal Activism” was written after Francis Fukayama’s risible neoliberal end-of-history claims had been proven wrong by the rise of political Islam but before it had also been proven wrong by the credit crunch. The credit bubble bursting has made it harder to claim that the revolutionary moment has entirely passed. Revolution is not imminent, but nor does a world where it might be possible seem unthinkable any more when the global economy has recently been described as being months or even just hours from collapse. And the clear class content of the act of socialising private losses of fictitious capital have started even the most Fukuyaman observers conscious of class politics once more.

Aileen Derieg’s translation for the Semiotext(e) English language edition deserves recognition for its clarity and flow. Semiotext(e)’s mission to bring the best continental philosophy to an Anglophone audience is well served by such competent translation.

Revolution may not be imminent, but with the art market, the global economy and the planet’s ecosystem all in danger of collapse more and more artists are looking for models for genuine political engagement in art rather than “career building bullshit that cares”, to quote Art & Language. “Transversal Activism” provides engaging and instructive case studies of political and artistic success and failure at moments of political possibility contextualised for a contemporary artworld and academic audience. Raunig has produced a very readable and instructive set of historical case studies not so much of praxis as of actually doing something.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

The first NODE.London Season of Media Arts in 2006 was conceived as an experiment in tools and structures of cooperation as invented or adapted by artists, technologists, and activists, many of whom were committed to ideas of social change through their practice. It was to be an experiment in radical openness. Not just to be confined to participatory artistic processes and events but also applied to the method of organisation.

This text by Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett is a reflection on the NODE.London “experiment”, its context, its cultures and the make up of its events, infrastructure and organisation. It points to some earlier grassroots media arts festivals in London and gives a bareÂbones description of the components of the NODE.London 2006 season. Taking Felix Stalder’s analysis of the difference between Open Source and Open Culture, this text looks at how different ideas and approaches to networks and openness were played out in the first season. With a focus on organisational matters, it further makes some judgements about where these were fruitful and where they were problematic. Finally it looks at the work of OpenOrganizations as one example of alternative frameworks for grassroots organisations and suggests that by directly addressing the particular problem of organisation, it might be possible and worthwhile to support the development of grassroots media arts infrastructure in London, including the possible iterations of a NODE.London season.

Download full text here (pdf 640k)

Furtherfield in support of Ada Lovelace Day

Ada Lovelace Day was conceived of and promoted by Suw Charman-Anderson as a way of “bringing women in technology to the fore”. It was successful in motivating nearly 2000 people to publish a blog post about a woman in technology whom they admired. In support of Ada Lovelace Day we invited women working in media arts to join the NetBehaviour.org email list for a week, between 23rd and 30th March. They were invited to post information about their own work alongside the work of other women who had inspired them in their own practice. Some names came up a number of times but with different stories and for very different reasons. NetBehaviour provided a context for sharing and discussing influences and tracing connections: artistic, practical, theoretical, technical, historical, personal. For readability this edited list does not include all of the discussion but this can be traced back through the NetBehaviour archives. Some contributors were anxious about the many excellent people who may have been missed out. We know this is not a definitive survey or list but it is an excellent resource and just one possible starting point for anyone wanting to know more about women working in media art.

A big THANKS to all of those – women and men – who contributed to this tribute!

Click here to view project:

http://www.furtherfield.org/ada_lovelace.php

Pall Thayer’s Microcodes are short code art pieces written in Perl and presented on a website for viewers to read, download, and execute. Each code piece encapsulates tasks performed by artworks such as portraiture or memento mori. They follow on from Thayer’s earlier “Exist.pl”, which allegorized life, death and being using running Perl code.

This is a Romantic use of code, a projection of human experience onto mere material existence. Processes become lives or individuals, network sockets become voices or eyes. And in a Nietschean twist some of the code can be genuinely destructive for data. But it works the other way round as well, demonstrating that meaning can be found in or recovered from mere processes.

The program listings are presented on a modern, neutrally styled, website for download and execution. The code is licensed under the GNU GPL version 3 (or later), so everyone is free to use, study, modify and redistribute it. The use of the GPL should be a given for code art, but far too many artists are happy to take the freedom that they are given by other hackers and not pass it on. Thayer deserves credit for doing the right thing.

You can send modified versions back to be published on the Microcodes website, something that resembles social media and collaborative web projects, but this isn’t yet the focus of the project. Given the opposition between social media and computer programming that some commentators have tried to establish (myself included), it is refreshing to see a project that uses elements of both where both can add to it.

Historically, “microcode” is the inner programming of microprocessors such as the ARM or Pentium, the level below machine code. Thayer’s Microcodes are short (micro) programs (code) written in the programming language Perl. Perl is a well-established and popular language for scripting and for web programming. It is a more typographic language than many, with a rich and intentionally ambiguous syntax. This makes it ideal both for expressive programming and for visually interesting program listings.

Perl is installed on modern operating systems by default (and can easily be installed on Windows). Running a Perl script in 2009 therefore requires minimal geekery. But Perl is a strange-looking enough language, even compared to newer scripting languages and other C-style-syntax (curly-brace-based) languages, that using it emphasizes the strangeness of code and makes its structures visually noticeable.

Like any Perl script each Microcode creates a composition of relationships between operating system resources such as processes, network sockets and files. Unlike most Perl scripts this is the intended end result of the code, not a side effect of its execution or the means to the end of the program’s effects as for example a UNIX command-line tool. The process of executing the code is intended for contemplation rather than for instrumentalization. The incidental or contingent becomes the primary or key.

Information workers spend at least eight hours a day “in” the digital landscape of the computer or the network. This is their landscape. Software that depicts this environment is in a way the landscape or land art of the UNIX hegemony. It functions as paintings of Venice or as stone circles for hackers and for anyone whose life is touched by technology.

Software is both performed, as something that is written by a programmer, and performance, as something that performs a task. Making that performance the focus of the software’s execution makes the software the intended result and subject of both acts. Software debuggers observe and present the inner working of the operation of other pieces of software, but not of themselves. It’s a bad old joke in aesthetics that art is defined by its inutility. But it is true that code that does nothing other than what it does must in some way be doing (or being) itself and that if this is the intended result of executing the software then this must be intended to be interesting in some way.

When I was at art school I took up programming as one means of resisting the local hegemony of art-as-text under the stultifying academic regime of semiotics-and-Marxism. Programming is a specific, technical competence that cannot be replaced with “generic” textual or managerial skills. Artistic practice also consists at some level of technical competences. This upsets both managerialistic critics and curators (who need interchangeable and easily ventriloquised art) and managerialistic artists (who need interchangeable and easily ventriloquised artisans to actually make the products of their semiotic genius).

I, and others, have claimed that artists who use computers need to be able to program. Artists who, whatever their intent, accept computers as closed tools are often offended by this. But mastery of tools is a prerequisite for competent expression. There is the question of at what level this mastery needs to be demonstrated, though. If one wishes to be an Impressionist should one master colour theory while using pre-mixed oil paint in tubes or does one need to master molecular chemistry?

Thayer’s work is competent programming but as a project it is socially open. You don’t need to be able to program to appreciate or add to it. It can be taken and modified as an aesthetic as well as executable resource. Its framing as code is clear, but its presentation on a social site and its licensing under the GPL leave its use by other artists, whether programmers or not, open. It frustrates those of us who hoped to use code to draw a line in the sand by using code effectively as a social product and resource.

The creation of software that does nothing useful as a command-line tool is not comparable to too many artists’ technically incompetent use of medical equipment, mathematical equations or scientific theories as mere imagery in aesthetically competent artworks. Software has to run. Thayer’s Microcodes run, run correctly, and perform as specified.

A hacker and free software activist I know asked me what exactly makes the Microcodes code listings art (interestingly, they didn’t ask why they are code). I gave two reasons:

Firstly, the text of each program listing is short enough to be taken in as a single visual composition. When presented under the claim that they are art they therefore fall into the tradition of conceptual text-as-art. The tension between appearance and meaning that this implies is a live issue in art history and in art. There is an immediate and historical aestheticism or artistic-ness to the code.

Secondly, the behaviour of each program when it runs achieves no practical task as a command-line utility. It is therefore either useless or intended for some other purpose. The user must evaluate it using on their knowledge of what it does and how this relates to their experience of software. That is, on its aesthetics and iconography rather than on how it performs as a tool for some other external end.

This is exemplary code art. It makes strange the environment of the operating system and the command line. It creates an aesthetic representation, a meaningful resemblance in appearance but not function, of it in code as an object for contemplation. Microcodes has a balancing social component, but by being at its core unashamedly about code it allows that code to be about something of interest rather than the ostensive social or political content of the project just being an excuse to write code. This is code about the experience of being human in society in a time when being human in society is in no small part about the experience of code.

http://pallit.lhi.is/microcodes/

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Jorn Ebner’s “(sans femme et sans aviateur)” is an atmospheric time-based multi-window web-browser image work that presents an evocative exploration of contemporary Paris.

It consists of four series of pop-up browser web windows containing image slide shows which are programmatically arranged in turn on the desktop. The content of each window is static but animated by blurring or scrolling. The frames of the windows are also animated, being opened, closed and placed. Window choreography in net art has a long history, but there’s something subtle and satisfyingly compositional about Ebner’s windows. They are part of the flow of the story, or absence of story.

The build-up of windows on the desktop resembles the way that windows accumulate during the average computer user’s working day, only arranged with more intent and precision. Instead of word processor and spreadsheets or web pages and emails the windows present what looks as if it should be a narrative told using photographs of the streets, alleys and parks of contemporary Paris.

But there are no characters and nothing happens. It becomes obvious that the people who appear incidentally in the background of the images really are just people who appear incidentally in the background. There is no foreground. There is an absence of presence. This is alienating, like being a stranger in a unfamiliar big city.

I didn’t know precisely what was absent, though, not being familiar with Eric Rohmer’s film “The Aviator’s Wife” which the launch page for (sans femme et sans aviateur) explains is its inspiration. Would this familiarity improve the experience of the piece? It would definitely change it. But (sans femme et sans aviateur) is a very successful as an alienated portrayal of a city even without that extra point of reference. A viewer who does not spot the references to the film can still spot the references to Paris and to the haunted empty spaces of a modern city.

I did have to struggle with Firefox’s popup blocker to start the piece, but the instructions on its page at Turbulence explained what I needed to do. (sans femme et sans aviateur) uses Flash but it’s a mark of how far web technology has progressed since FutureSplash was first released that it could as easily be made entirely in JavaScript and HTML using the new “canvas” tag. This isn’t a technology demonstration, though, it is a work of art that uses technology to embody its aesthetic.

The wandering of a city guided by an incongruous text, especially if that city is Paris, evokes Situationism. (sans femme et sans aviateur) has the feel of a modern psychogeographic investigation, a tour of a city guided by a film rather than an inappropriate map. The measured pace of (sans femme et sans aviateur) allows it to deliver an increasingly strong feeling of immersion in its made-strange world. Repeated watching only increases this.

Whether as a homage to a film or as a psychologised depiction of urban space, (sans femme et sans aviateur) is worth taking the time to watch unfolding on your monitor. And to watch repeatedly, to let it draw you in. It is mature work of net art, relying not on visual or technical pyrotechnics but on the viewer’s visual competence to present a compelling meditation on the meanings we give to places.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

The early experimental video art scene in Chicago, and its indispensability in developing an understanding of contemporary New Media practices, is something that I learned from jonCates and that jonCates learned from Phil Morton. Well, maybe it’s not quite that simple, but that is one possible set of connections that can be traced from jonCates’ COPY-IT-RIGHT project.

The Phil Morton Memorial Research Archive was initiated in 2007 by jonCates and is housed in The Film, Video & New Media Department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. It exists to organize and freely distribute Phil Morton’s new media artwork, and also to perpetuate the COPY-IT-RIGHT ideal that Morton advocated. As you can read on the blog for the COPY-IT-RIGHT project, Morton sought to disseminate an anti-copyright attitude towards media and its distribution, especially artwork that is based in digital technologies. By referencing these ideals under the phrase ‘COPY-IT-RIGHT’, Morton sought to completely replace ingrained notions of copyright law by re-framing the term’s meaning as a call to action. Make copies! It’s the right thing to do! jonCates states that COPY-IT-RIGHT ranges in meaning from copyright reform to pro-piracy. “The COPY-IT-RIGHT ethic is presented by Morton as a value, even as a moral imperative, to share and freely exchange media,” he said.

jonCates began researching Morton’s work shortly before he learned of Morton’s death from Jane Veeder, one of Morton’s collaborators. Veeder put him in contact with Morton’s surviving partner, Barb Abramo, who later entrusted all of Morton’s archived material to him. jonCates said that this took place after a couple years of correspondence and a developed understanding. The creation of the archive is, “a personal and subjective process that involves developing trust and friendships.”

The personal degrees of separation enabling this archive, however, should not betray it’s larger goal, which, according to jonCates, is to facilitate discourse. “This discursive work is intended to be productive, engendering the development of theory/practices that are informed by these archives and contributing to ongoing conversations,” he states. The archive is a central point of investigation, but also exists as a mediating voice within existing networks and issues, in both form and content. The intermingling of the archive’s personal and institutional roots is exemplary of how individual archives might begin to bridge recognized authority and the histories that are important to individuals.

Because COPY-IT-RIGHT is a project that seeks to freely distribute media art, as well as create a networked discourse around it, we are invited to explore ideas such as influence and the generative origins of our knowledge. This process eclipses antiquated visions of the archive as a static source of ‘knowledge’ or ‘history’.

COPY-IT-RIGHT’s latest web entry is a transcript of a talk jonCates gave at McGill University on anti-copyright approaches to media. In that talk, he refers to “the artistic role of archives”. jonCates provided some further examples of “artistic archives”, such as Emily Jacir’s Material for a Film and Walid Raad’s The Atlas Group, which both seek to illuminate history and contemporary contexts through materials that might not be automatically absorbed into our stateliest cultural institutions. They represent an independent approach to information collection, at the same time that they contain material that is itself a challenge to dominant cultural and historical knowledge. Likewise, COPY-IT-RIGHT is a lesser-voiced exploration of Chicago’s art history, but also an open-ended call to discuss and develop material on the future of media copyright attitudes.

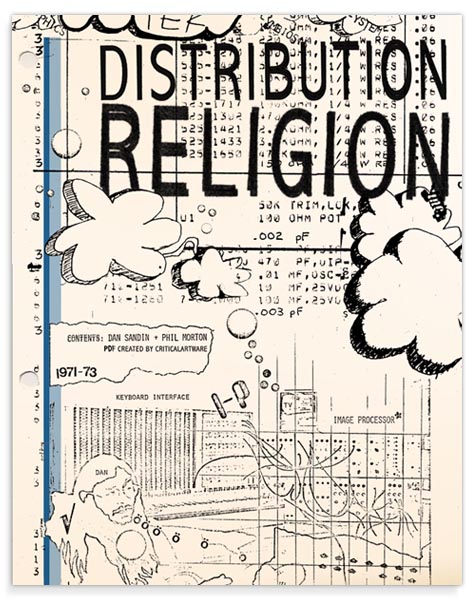

The COPY-IT-RIGHT project, as mentioned, also exists to provide entry into Morton’s media art, for study or copy. The work he did with Dan Sandin, creator of the Sandin Image Processor – an analog computer for video image processing. Morton and Sandin’s “Distribution Religion” is a project that documents the process of duplicating the Sandin Image Processor. Morton wanted to create a duplicate of the processor itself, and in the process, created an outline of the method for others. The documentation became part of the copying process, and also includes remarks on the COPY-IT-RIGHT ethic.

The Distribution Religion is archived on giorgiomagnanensi.com. Examining this document and reading its prefatory statements seem to get at the heart of COPY-IT-RIGHT’s significance. jonCates is interested in the fact that Morton and Sandin’s work “predates The Pirate Party, Free and Open Source Software, Creative Commons and/or the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.” Although most copyright initiatives are steeped in political and legal challenges, COPY-IT-RIGHT offers an inaugural stance on issues that are at the forefront of contemporary culture: interdisciplinary desires, open information, and the democratic malleability of our cultural memory.

We have come to expect that information is distributed, and available. But we don’t necessarily employ it for our own purposes with the intent of ‘copying’ it. But this is, in essence, a direct form of preservation. In a 2004 lecture, Florian Cramer cited a parallel between artists who step outside of copyright law, and the sciences. Scientists, he says, have mostly been free to use formulas and proofs in the generation of new discoveries. In this light ‘copying’ has now become synonymous with ‘usage’ and the natural role this plays in the development of ideas become even more obvious. COPY-IT-RIGHT, by existing as an explicitly anti-copyright project and by making Morton’s materials available for the generation of new works, aligns the idea of copying with progress rather than piracy or plagiarism. As jonCates states in his own lecture, the ethic “opposed private property, ownership and economic exploitation on the basis of technologies.” COPY-IT-RIGHT suggests that the availability of resources is, as jonCates puts it, “not simply for study, but also for creative cultural uses by artists.”

Having attended some of the exhibition events at Transmediale.09 Deep North, in Berlin over the weekend of 29th January to 1st February this year I write this article from the departure lounge of the Berlin Schonenfeld airport. A blast of cold arctic weather has enveloped the UK, leading to the cancellation of all flights in and out of Stanstead airport and provided me with some down time in which to reflect on the festival.

Transmediale.09 Deep North purports to construct an impression of the polar regions as a place that can be “imagined but never truly captured”. In seeking to move beyond prevailing notions of catastrophic environmental change and to examine its broader cultural consequences, the festival aims to adapt and explore creative technologies and point the way to political transformation and creative sustainability. Such lofty ambitions are commendable though how attainable they are through the engine of an arts festival remains to be seen. Furthermore the festival organisers can be in no doubt of the irony that the success of their event is largely predicated on the numbers of media arts professionals flying in from across Europe to consider such issues, and as such anyone making too strong an argument for political and social action might be construed of as a little hypocritical.

If the festival sets itself philosophical objectives that are difficult to achieve, then the works exhibited around Berlin as part of the event stand or fall on their own individual merits, their abilities to provoke thought and reflection, while the exhibitions in which they are showcased must provide a context for there inclusion and a link to the wider aims of the festival.

The main site at The House of World Cultures in the Tiergarten has been transformed into a “makeshift zone of cultural shelter” by the Berlin design group raumtaktik. Different works occupy the buildings foyer, some of its anterooms and it’s main exhibition space. The gallery charged a five euro fee for entry, while works in other parts of the building were freely accessible. There were guides on hand in all areas, but while most were helpful and allowed photography this was strictly limited to accredited press at the paying show. Whatever the intention was, this practice produced a hierarchical construct, with the works within the boundary of the paying show being effectively corralled off from those outside and thus somehow being given an authoritative stamp.

Overall the works exhibited in the paying show were less interesting than those displayed outside. This was with the exception of Jan-Peter E.R. Sonntag’s Amundsen / l-landscape (which I was unable to photograph). This work required you to stand on a podium and don a pair of headphones while watching a video projection of a rain spattered watery scene. The footage for this was shot in Norway close to the home of Amundsen, the famous polar explorer. another aspect of the same exhibit was a huge block of ice, sitting on a board suspended from cables in space and illuminated by a heat lamp. Sensors fitted into the board picked up data from the melting block and this was digitised and fed-back to the viewer via their headphones. The ice produced the sound of a deluge, the soundtrack to the film making our experience of the whole work simultaneously deeply mediated and intensely poetic.

Jan-Peter E.R. Sonntag – AMUNDSEN / I-landscape (de, 2009). Photo: Jonathan Granger

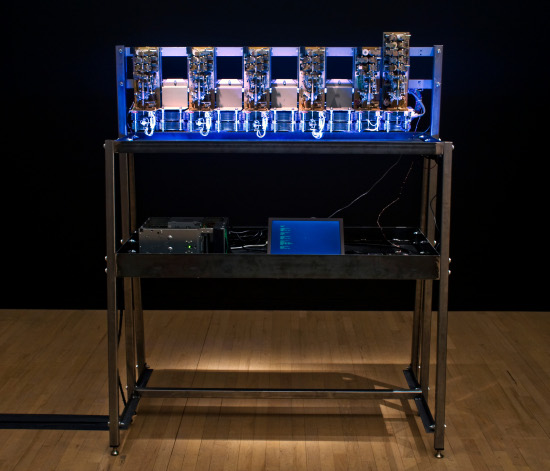

Other works within the House of World Cultures but outside the paying exhibition that were of note included; Harwood, Wright and Yokokoji’s Telephone Trottoire, a project which enables the worldwide Congolese community to reformulate a form of traditional communication via networked technology. The work, which won this years jury prize had a material, almost sculptural quality, made manifest through its use of redundant analogue telephone exchange equipment. “For ‘Telephone Trottoir’, we recorded twenty short monologues or clips focusing on life both in the UK and back home in the DRC. These clips were intended to pose questions, impart information, highlight factual events, and to provoke the listener into making a comment or just to think about their lives and the future of the Congolese community in the UK. All stories and dialogue were recorded and played back in Lingala/French, which meant that listeners were much more inclined to accept the calls and participate in the project.”[1]

Graham Hardwood, Richard Wright, Matsuko Yokokoji (uk) Telephone Trottoire -Tantalum Memorial (2008)

Petko Dourmana’s Post Global Warming Survival Kit is an installation inviting the audience to explore it in a darkened space with night vision headsets. Ready to be discovered inside the space were projections of a bleak, featureless landscape and a small mobile caravan which you were able to enter and survey. Set up as an imaginary post apocalyptic world in which human vision has adapted to the nuclear winter, the experience of the work is deeply unsettling, requiring the audience to use their sense of sight to somehow ‘feel’ their way around the space. “Confrontation with the bare necessities for survival provided by Dourmana quickly makes viewers aware that more is needed than mere material goods to ensure emotional survival as well. In his post-apocalyptic world, Dourmana allows viewers to experience other visual worlds or aspects of our reality that are invisible without the aid of high-tech devices. Without technology, we would be blind in his world.”[2]

Petko Dourmana – Post Global Warming Survival Kit. Photo: Petko Dourmana

There are of course many other partner organisations involved in a festival as large as this, with many other workshops and exhibitions taking place at fringe venues and it is here that much of the more interesting experimentation takes place. Club Transmediale in particular offered interesting content, with groups such as Bank of Common Knowledge providing inspirational support to those interested in collaborative production practices and soundmuseum.fm an audio repository.

The Collegium Hungaricum Berlin, another partner venue in the festival provides a site for an ambitious architectural project. Corpora In Si(gh)te Architecture as an environmental, spatial measuring machine presents several projected video screens that map in real-time the flows and eddy’s of air currents around the building. Data is gathered through a mesh network set up in the vicinity of the building and presented within it as a form in a state of constant flux.

In the UK the weather used to be a safe subject for conversation, people could discuss it without the need to make cultural references, and thus revealed little about themselves, or their backgrounds, it was a subject upon which you were allowed to disagree. All this has changed, as global warming becomes climate change, the traditional late January cold snap for which we are totally unprepared takes on other overtones. While on the one hand there is a temptation to dismiss much of what is argued as our effect on the planet as humanist arrogance, the ethical questions of how we behave and act still require more exploration.

I am now stranded at Dublin airport en rout to the UK, the battery on my laptop about to give out, while an almighty snow storm rages across Western Europe. At times like this The Deep North seems much less an abstract concept and much more a hard reality, to be weathered, and dealt with as best we can, as we are jolted out of our everyday lazy reliance on our global communications infrastructures and our perceived ability to somehow exist outside of ‘nature’ is distinctly thrown into question.

[1]WHY TELEPHONE TROTTOIRE?

http://www.tantalumexploration.net/pages/trottoirehistory.php

[2]Text by Sabine Himmelsbach Artistic Director of Edith Russ House for Media Art.

http://www.dourmana.com/node/104

SwanQuake: House

igloo (Ruth Gibson & Bruno Martelli)

v22 Ashwin Street

Thursday October 16, 2008 to Monday November 3, 2008

Igloo’s “Summerbranch” was an ultra-detailed virtual reality environment depicting a woodland landscape populated by incorporeal dancing figures as day changed to night. Their new work “House”, the first part of the ongoing “SwanQuake” project, has an urban setting but it is is no less uncanny. As installed at v22 Ashwin Street the realisation and presentation of House continues and intensifies some of the most successful aspects of Summerbranch.

House features the penthouse apartment of the title overlooking a stormy street, the stairwell of an apartment block, the tunnels of a Tube station, and more fantastic elements such as a burnt-out tube train that leads to a portal to hell. Occasionally, ghostly female figures dance endlessly through graceful choreography trapped in time and space.

The darkly lit corridors, tunnels and rooms rendered by a first-person shooter (FPS) game engine and haunted by impersonal ghostly figures immediately call to mind the survival horror genre. There’s an unsettling feel to the environment, even when the feeling of threat gives way to a sense of wonder in the underground warehouse filled with joyfully dancing figures.

The gritty realism of stairwell and underground are joined to House’s more fantastic elements almost casually. Hell, the underground hangar and rocky tunnels lead to and from the haunted almost reality closer to the surface. One element that hangs between the real and the unreal it the burnt out tube train that brought the terror attack on the tube of 2005, or further back the damage of the Blitz, to mind. But the Tube station sign reads “Fackin Ell”.

House is rendered using the proprietary FPS game engine “Unreal Engine”, despite SwanQuake’s title reference to a more famous FPS game engine. The dancing figures are animated from motion capture data taken from real dancers.

On a technical level, the modelling of the environments and the smooth motion of the animated figures is superb. This technical competence marks igloo’s work out aesthetically compared to the shaky, performance-destroying motion capture of Hollywood movies and compared to the limitations of combat games that must balance the complexity of environments with the complexity of network-controlled player character and monster models. Control of the medium is vital for expression, and igloo demonstrate this.

On a conceptual level, there is something about taking the aesthetics of dance and real-time 3D games as a point of departure that reverses the aestheticization of the bodily movement of violence through technology of the Matrix films or the fragmenting body horror of FPS and survival games that is so prevalent in popular culture. Dance is a grammar of living bodies, shooting games are the choreography of dying bodies. SwanQuake achieves a critical distance from a pervasive and important part of contemporary popular culture in this way that many artists are happy to ironise only for nostalgia or shock value.

Summerbranch was presented as video projections on walls in a darkened gallery, with the track-ball controls on podiums on the floor. House has a more modest scale but a unique means of presentation. A wide screen on a wooden dresser or desk, with the trackball and buttons set into its surface. It looks like a bedroom Memex, Vannevar Bush’s imagined prototype knowledge work device that would have been a desk with a microfiche reader built in. It provides a domestic frame for House even in the gallery space, taking control of the presentation and interaction with the virtual environment. This is a successful solution to some of the issues of how exactly to display new media art in a gallery. And it’s great fun to use, if even more prone to producing motion sickness than Summerbranch.

Igloo’s environments are site-specific in a way that is surprising for VR. Summerbranch was developed at Artsway Gallery in the New Forest and depicts an area of that forest. House depicts Igloo’s own apartment and the gallery that it is being exhibited in among its other elements. It’s a shock to realize that you have wandered in the game into the gallery that you are physically stood in.

The gallery, the real gallery, includes elements of the game in return. The lighting of the gallery has been carefully set low, and at first you might not notice that some parts of the wall next to the desk in the first room is not actually brick but is actually bitmaps of bricks printed on vinyl and mounted on panels. The second room has an entire wall replaced with a bitmap.

The textures are from the game engine representation of the gallery and have the slightly contrasty, mach-banded, pixelated but smoothed and blurred look of compressed photographically derived bitmaps. At first, they look real, then a sneaking suspicion is followed by the shock of realization that they are unreal. The show is structured as a linear series of environments that increase the real space’s unreality and the virtual space’s reality each time.

Between the second and last rooms in the real gallery is a darkened corridor that screams “survival horror FPS”. At one end of it an oval mirror frame surrounds a projection of a scene from the VR version of a corridor, slowly moving (Igloo tell me that it is seen from the point of view of one of the dancers). A single bare light bulb, reflected in the projection, hangs at the other end. There’s an unsettling feedback between the real and the unreal.

The final room has only its ceiling and floor uncovered. Printed bitmap panels completely cover the walls. It’s a shock to realize that they are unreal. It is as if you have passed through the mirror in the corridor. One of the bitmaps is a reflection of the one opposite; even the light switch is a texture map. Returning to the other rooms and using the virtual environment again is a different experience after this crescendo of tension between reality and virtuality.

House is a more difficult virtual environment to navigate than Summerbranch. I missed entire areas, including, vitally, the gallery, and I couldn’t steer the camera through the door to the penthouse. The competence of the viewer is always a variable in the experience of art, but interactive multimedia makes this explicit and a matter of the practical performance of the viewer. Seeing the real and projected light bulb-lit corridors without seeing the gallery in the virtual environment was unsettling. But having seen the corridor in the environment was head-spinning. Is it unfair that some viewers will miss this, or is it just a technological reflection of the fact that every viewer will experience every artwork differently modulated by their competences? House exposes these issues in a way that the more open environment of Summerbranch didn’t so such a degree.

The relationship between reality, representation and unreality is at the core of the installation of House, expressed through a tangent to the aesthetics of one of the paradigmatic embodiments of that relationship: FPS games and the other of its hyper-masculine body choreographies and Bond Villain fantasy architecture. This remains a key part of the experience of contemporary culture. igloo’s effective combination of real and virtual space embodies and opens it up. It is a satisfying spectacle in itself, and it rewards extended viewing and reflection.

SwanQuake: House

igloo (Ruth Gibson & Bruno Martelli)

v22 Ashwin Street

Thursday October 16, 2008 to Monday November 3, 2008

Igloo’s “Summerbranch” was an ultra-detailed virtual reality environment depicting a woodland landscape populated by incorporeal dancing figures as the day changed to night. Their new work, “House”, the first part of the ongoing “SwanQuake” project, has an urban setting, but it is no less uncanny. As installed at v22 Ashwin Street, the realisation and presentation of House continues and intensifies some of the most successful aspects of Summerbranch.

House features the penthouse apartment of the title overlooking a stormy street, the stairwell of an apartment block, the tunnels of a Tube station, and more fantastic elements such as a burnt-out tube train that leads to a portal to hell. Occasionally, ghostly female figures dance endlessly through graceful choreography trapped in time and space.

The darkly lit corridors, tunnels and rooms rendered by a first-person shooter (FPS) game engine and haunted by impersonal ghostly figures immediately call the survival horror genre to mind. The environment has an unsettling feel, even when the feeling of threat gives way to a sense of wonder in the underground warehouse filled with joyfully dancing figures.

The gritty realism of the stairwell and underground are joined to House’s more fantastic elements almost casually. The underground hangar and rocky tunnels lead to and from the haunted reality closer to the surface. One element that hangs between the real and the unreal is the burnt-out tube train that brought the terror attack on the tube of 2005, or further back the damage of the Blitz, to mind. But the Tube station sign reads “Fackin Ell”.

House is rendered using the proprietary FPS game engine “Unreal Engine”, despite SwanQuake’s title referencing a more famous FPS game engine. The dancing figures are animated from motion capture data taken from real dancers.

Technically, the environment’s modelling and the animated figures’ smooth motion are superb. This technical competence marks igloo’s work out aesthetically compared to the shaky, performance-destroying motion capture of Hollywood movies and compared to the limitations of combat games that must balance the complexity of environments with the complexity of network-controlled player characters and monster models. Control of the medium is vital for expression, and igloo demonstrates this.

On a conceptual level, there is something about taking the aesthetics of dance and real-time 3D games as a point of departure that reverses the aestheticization of the bodily movement of violence through the technology of the Matrix films or the fragmenting body horror of FPS and survival games that is so prevalent in popular culture. Dance is a grammar of living bodies, and shooting games are the choreography of dying bodies. SwanQuake achieves a critical distance from a pervasive and important part of contemporary popular culture in this way that many artists are happy to ironise only for nostalgia or shock value.

Summerbranch was presented as video projections on walls in a darkened gallery, with the track-ball controls on podiums on the floor. House has a more modest scale but a unique means of presentation. A widescreen on a wooden dresser or desk, with the trackball and buttons set into its surface. It looks like a bedroom Memex, Vannevar Bush’s imagined prototype knowledge work device that would have been a desk with a built-in microfiche reader. It provides a domestic frame for House, even in the gallery space, taking control of the presentation and interaction with the virtual environment. This is a successful solution to some of the issues of how exactly to display new media art in a gallery. And it’s great fun to use, if even more prone to producing motion sickness than Summerbranch.

Igloo’s environments are site-specific in a way that is surprising for VR. Summerbranch was developed at Artsway Gallery in the New Forest and depicts an area of that forest. House depicts Igloo’s apartment and the gallery it is being exhibited in, among its other elements. It’s a shock to realize that you have wandered into the game into the gallery that you are physically standing in.

The gallery, the real gallery, includes elements of the game in return. The lighting of the gallery has been carefully set low, and at first, you might not notice that some parts of the wall next to the desk in the first room is not actually brick but are actually bitmaps of bricks printed on vinyl and mounted on panels. The second room has an entire wall replaced with a bitmap.

The textures are from the game engine representation of the gallery and have the slightly contrasty, mach-banded, pixelated but smoothed and blurred look of compressed photographically derived bitmaps. At first, they look real, then a sneaking suspicion is followed by the shock of the realization that they are unreal. The show is structured as a linear series of environments that increase the real space’s unreality and the virtual space’s reality each time.

Between the second and last rooms in the real gallery is a darkened corridor that screams “survival horror FPS”. At one end of it, an oval mirror frame surrounds a projection of a scene from the VR version of a corridor, slowly moving (Igloo tell me that it is seen from the point of view of one of the dancers). A single bare light bulb, reflected in the projection, hangs at the other end. There’s an unsettling feedback between the real and the unreal.

The final room has only its ceiling and floor uncovered. Printed bitmap panels completely cover the walls. It’s a shock to realize that they are unreal. It is as if you have passed through the mirror in the corridor. One of the bitmaps is a reflection of the one opposite. Even the light switch is a texture map. Returning to the other rooms and using the virtual environment again is a different experience after this crescendo of tension between reality and virtuality.

House is a more difficult virtual environment to navigate than Summerbranch. I missed entire areas, including, vitally, the gallery, and I couldn’t steer the camera through the door to the penthouse. The competence of the viewer is always a variable in the experience of art, but interactive multimedia makes this explicit and a matter of the practical performance of the viewer. Seeing the real and projected light bulb-lit corridors without seeing the gallery in the virtual environment was unsettling. But having seen the corridor in the environment was head-spinning. Is it unfair that some viewers will miss this or is it just a technological reflection of the fact that every viewer will experience every artwork differently modulated by their competences? House exposes these issues in a way that the more open environment of Summerbranch didn’t so such a degree.