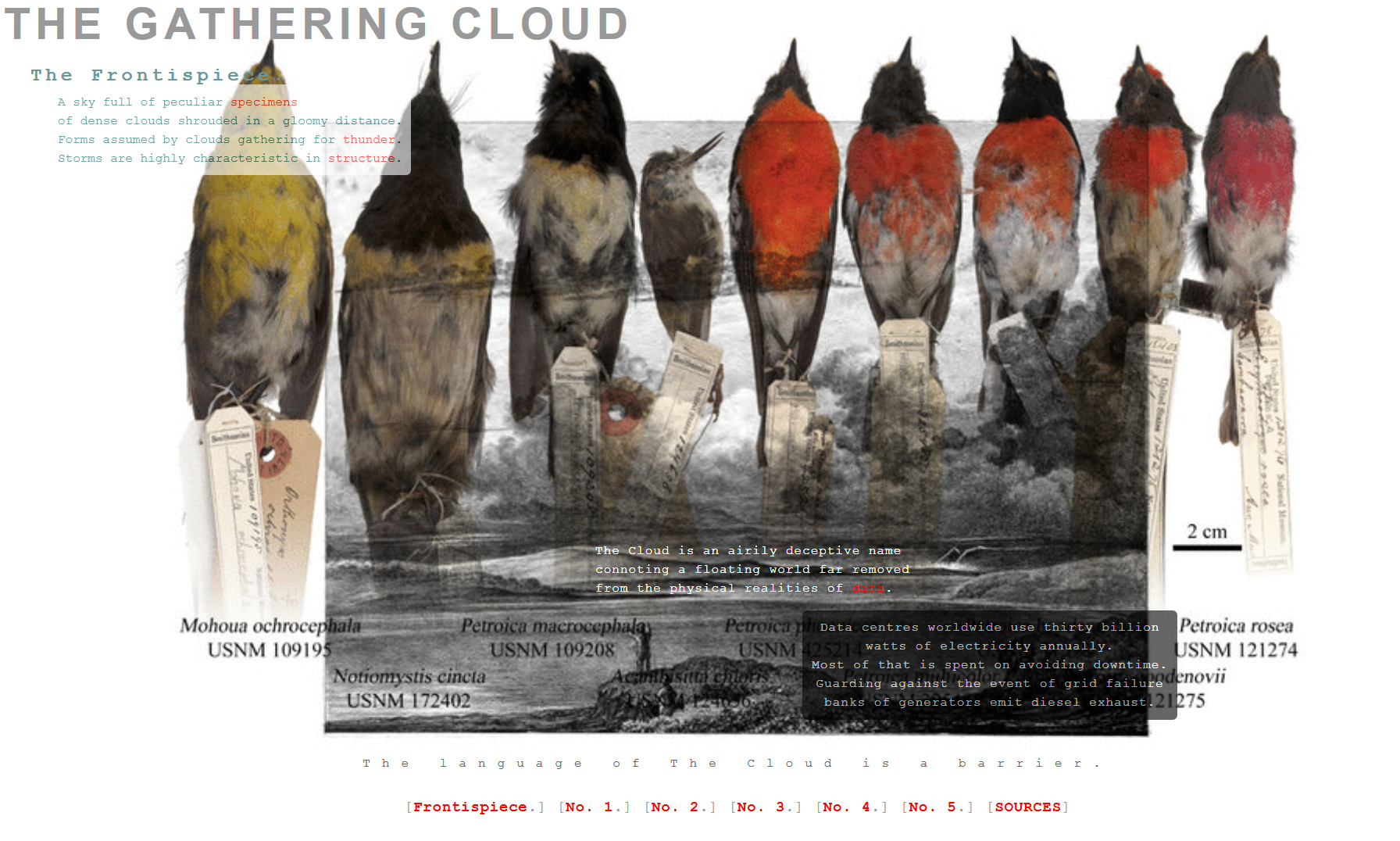

Information wants to be free, and net art is information. Trying to make it harder to copy is like trying to make water less wet. Or perhaps like trying to give it a soul. In “Blockchain Poetics” I described “new kinds of quasi-property” created using the Blockchain as a mis-application of that technology. Ken Wark is similarly unimpressed – “My Collectible Ass“, he complains in e-flux.

The history of Conceptual Art’s dematerialization of the art object shows that the art market loves nothing more than finding ways to make the previously unsaleable into financial assets. As Wark points out, “We tend to think that what is collected is a rare object.” There’s nothing rarer than something that doesn’t actually exist. But the un-ownable and non-or-barely-existent can be represented as property by proxy objects. Financial elsewheres rather than financial futures.

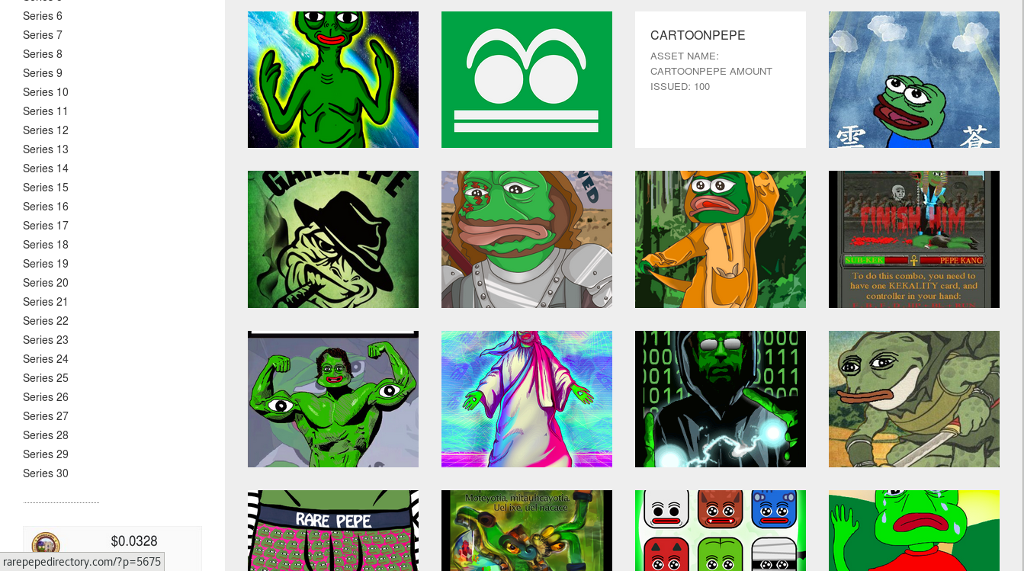

Cryptographic tokens are a generalization of cryptocurrency to represent assets other than money. Such as editions of digital artworks. Wark’s criterion of rarity is reflected in the name of the most successful crypto-token collectibles – “Rare Pepes” are detournements of the “Pepe The Frog” character (previously appropriated by the alt.right) that are sold as CounterParty tokens. CounterParty is a system layered on top of Bitcoin’s blockchain that allows the creation of new tokens with varying properties (different issuance amounts, subdividable or not, locked for further issuance or not, a sub-token of another token) which can then be exchanged and transferred backed by the security of the Bitcoin blockchain. It’s an older system than Ethereum or other platforms that are now used for tokens. It has few major use cases, and Rare Pepes are one of them.

To make a Rare Pepe card you create a CounterParty token with a reference to the image you are using in its metadata, issue as many tokens as you are going to, then lock the token so no more can be issued (making the token “rare”). Rare Pepe quantities, prices and styles vary. There are magazines and virtual galleries devoted to them. There is even a subtoken representing the original physical version of one image (with an edition size of one).

A more singular set of images are the “CryptoPunks” (seen at the top of this page), which exist as an ERC20 token (almost) on the Ethereum blockchain. The “smart contract” that administers the token contains a cryptographic hash of an image of 10,000 bitmapped characters which can be bought and sold using its functions. Like Rare Pepes, the punks have a lighthearted style (they are retro pixellated avatars) and have varying rarity (some features are unique, others appear on dozens of characters) . Unlike Rare Pepes, every punk was created at the start of the project and no more can be added. At the time of writing, punks are available to purchase for 0.12 to 1,010,101,101,110,010,011,000.01 ETH (40.35 to 339,616,193,448,241,111,336,826.06 USD).

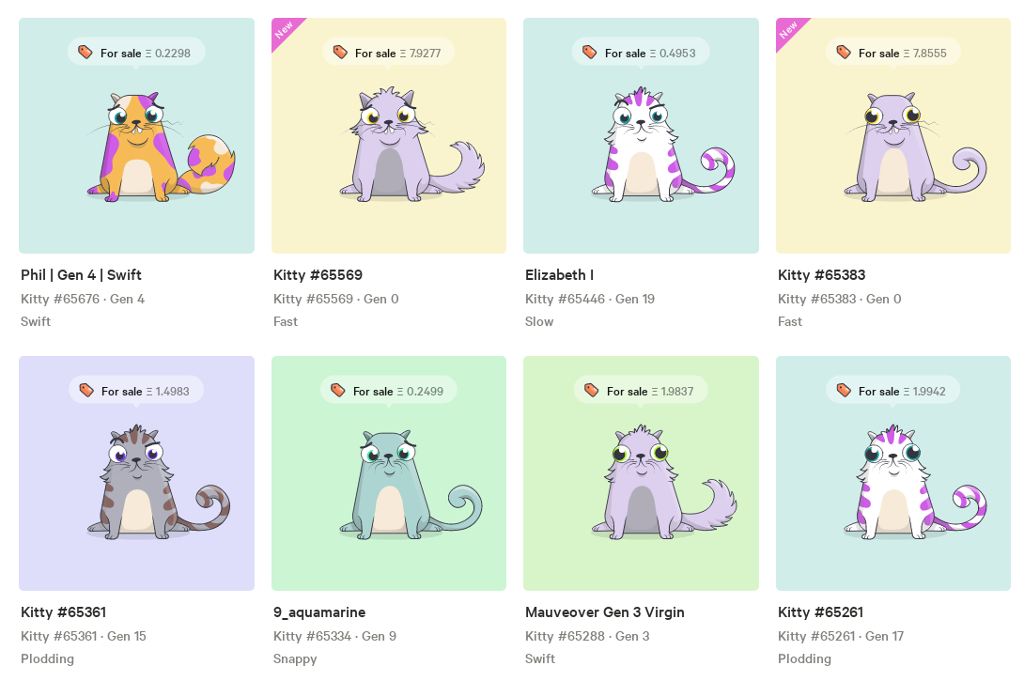

An even more playful approach may be able to take artificially scarce digital collectibles mainstream. CryptoKitties are customized cartoon cats whose appearance is determined by a digital genome (like the old “Cabbage Patch Kids” dolls) that can be interbred to produce more of them (like William Latham’s “Mutator”). At the time of writing they are taking up 13% of the Ethereum network’s capacity, making them the single biggest user of that blockchain, and the most expensive has sold for more than 100,000USD.

Every art is relative to a culture and an economy, whatever its other properties. The ground that tradeable blockchain images are a figure against is a particular moment in the history of cryptocurrency. Trading cards and digital collectibles fit a specific cultural niche, as does their iconography and the socially performative act of dealing in them. Their price may reflect the ability of cryptocurrency early adopters (who in the case of CounterParty and its XCP currency don’t have much else to spend it on) to be more extravagant with their hodlings.

“dada.nyc” follows the tokenized image edition strategy but applies it to popular/illustration art. Again each image is available for a given price in a given edition (for example 0.084 ETH in an edition of 150). The gallery takes a cut, and it takes a cut on profits on the secondary market. It also gives a cut to the artist, simulating Droit de Suite/Artist’s Resale Right. The Resale Right is controversial – it breaks the first sale doctrine and mostly benefits the estates of dead famous artists. But I implemented it as a user-settable property in the Art Market smart contract that I wrote in 2014 as I felt it was worth experimenting with in a voluntary setting.

Monegraph came out while I was working on that project. Like Ascribe it is a serious digital art registry implemented initially using pre-smart-contract technology (NameCoin for Monegraph, Bitcoin for Ascribe). These platforms’ seriousness and phrasing as registries contrasts with the playfulness and explicit tokenizaton of more recent systems. This and the already mentioned possible impacts of the social and economic impact of the increase in value of cryptocurrencies since 2014, along with the increased mainstream awareness of cryptocurrency, may explain the difference in their adoption (or at least their place in the hype cycle).

In contrast, Maecenas is a tokenized investment fund for physical fine art. It operates in part like the scene in William Gibson’s “Count Zero” (1986) in which Marly, one of the protagonists, reflects on how art in the mid-21st century is bought and sold as “points” in the work of a particular artist that represent shares in the value of the “originals” which are stored unseen in a vault. To quote their web site, “investors speculate via synthetic exposure: James is a Modern Art collector who needs to finance the purchase of a new Jeff Koons sculpture worth $120k. Instead of selling items from his collection, or getting an expensive loan, James get the required funding by listing in Maecenas 20% of one of his flagship pieces of art. Access to Maecenas is via an ERC20 token named (ART)” that Maecenas claim will improve access, transparency and fairness in the art market.

Propertization, fractionalization and financialization via proxy tokens (we cannot “own” allographic digital images, or own part of autographic paintings without dismembering them, but we can own tokens that we agree to pretend represent these things) promise to support art production using the economic accident of the value of cryptocurrency going to the moon. Quasiproperty without attempts at the costly fantasy of imposing access control via DRM is a form of, or a variation on the idea of, patronage. I feel this complex of ideas should be more useful to critics of the commodity form and capitalism than it has generally been treated as so far. If we still wish to take the opposite tack this leads us to the gift economy or the commons. Copyright is the default state for most art when it is created and is being increasingly restrictively enforced on the net. Opposing it passively or actively through alternative copyright licensing can perform a critique of this and keep space open for alternatives. These strategies needn’t exclude each other though.

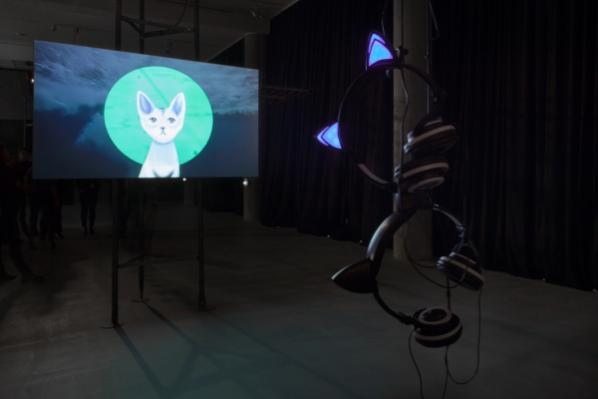

If you are familiar with DAOs, you can see how a system similar to these could become a self-supporting, self-curating DAO. Plantoid is an example of a singular artwork (or family of artworks) produced and exhibited in such a way. Imagine it generalized to a gallery or a participatory art show, a DAO that lets you do art with others, a DAOWO.

These technologies can provide objects for critical exploration that evoke wider contemporary themes. They can function as tools and resources for the creation of art and its social collectivities focussing on these and other themes. Within the existing economy they can provide ways of supporting the arts (as many of the projects mentioned above claim to), which should neither be dismissed reflexively nor accepted without irony. Or they can be used to try to bootstrap a different context entirely, even if only briefly or in the imagination. The various modes of tokenization represent potential ways of making a living in, critiquing, or even transforming the artworld in an era of the continuing expansion of the sphere of private property and financialization under technocapital.

It was not the cyberpunk universe you were looking for.

Our nostalgia centres were lit up with a cut from a flying car to a full screen eyeball staring across the opening scene, synchronized on the script and musical score of its 20th century precursors’ timing. From there, audiences of the Blade Runner sequel were dropped into a pale California wasteland blanketed with conglomerate agricultural biofarms, an antithesis to cyberpunk’s damp, urban hybridity. The green, utopic space beyond the city– only glimpsed at the end of the 1982 original theatrical release and removed entirely in the director’s cut– was where we started from in Blade Runner 2049, and (surprise) there’s nothing but the dystopia of the anthropocene to look forward to there either.

Times change.

The recently post-industrial, 20th century cyberpunk rebellion of bodily sensuality: the noir lighting, the baroque candelabras burning, the lingering fingers stroking out haunting piano music; these were relics now, hinted at, ghosts of a genre in its past moment. Even the endless rain characteristic of the cyberpunk genre was repeatedly replaced with snow in Blade Runner 2049. A borrowed soundtrack teasing the familiar bridge to a heroic death scene came without poetic dialogue or even a witness. Rogue replicants were not criminals, but escaping criminality. Even memories were no longer stolen in this world, but legally manufactured, a convention stripping the typical cybernetic plot of bioharvesting found in cyberpunk down to a more contemporary, bioengineered ethics of classed and raced co-humanity if ever there was one. No, this ethical failure was smoother, blended into liberal values and legal structures, more sanctioned somehow.

The 80s cyberlibertarian world of the white lone wolf, struggling for autonomy in a hybrid, post-globalized world of orientalist economic takeover, had passed by in the great data “black out” of 2020 apparently, and Denis Villeneuve didn’t care about your need for consistent genre romance. Sort of. Rather, the director brought the audience’s need for Blade Runner nostalgia in and out of the sequel like a tool, cuing our attention to wait for it, partially rewarding us with a sensory, semi-nostalgic moment, only to glitch before nostalgic completion. Again and again, it was invitation and estrangement from our own expectations. Blade Runner 2049 was a highly self-aware remix of its own postmodern references and refusals in a predetermined world.

Perhaps a hybridity across two cyberpunks of historical time and cultural change was apropos. Ridley Scott’s genre critique of the corrupt corporation had evolved since its 20th century take in the Alien franchise, expanding to consciously address our own implication in the techno-dystopian social narrative. It turns out that we are no longer universally laboring blue collar victims in the secretive horrors of impending biopolitical technocracy. Rather, we are eager and satiated participants in its isolating ubiquity; high tech consumers implicated in all of the attendant social stratification, inequality, and suffering that its warm glow of access masks and accelerates, from facilitated gentrification and casualized labor, to the toxic, extra-legal wastelands of dead electronics processing.

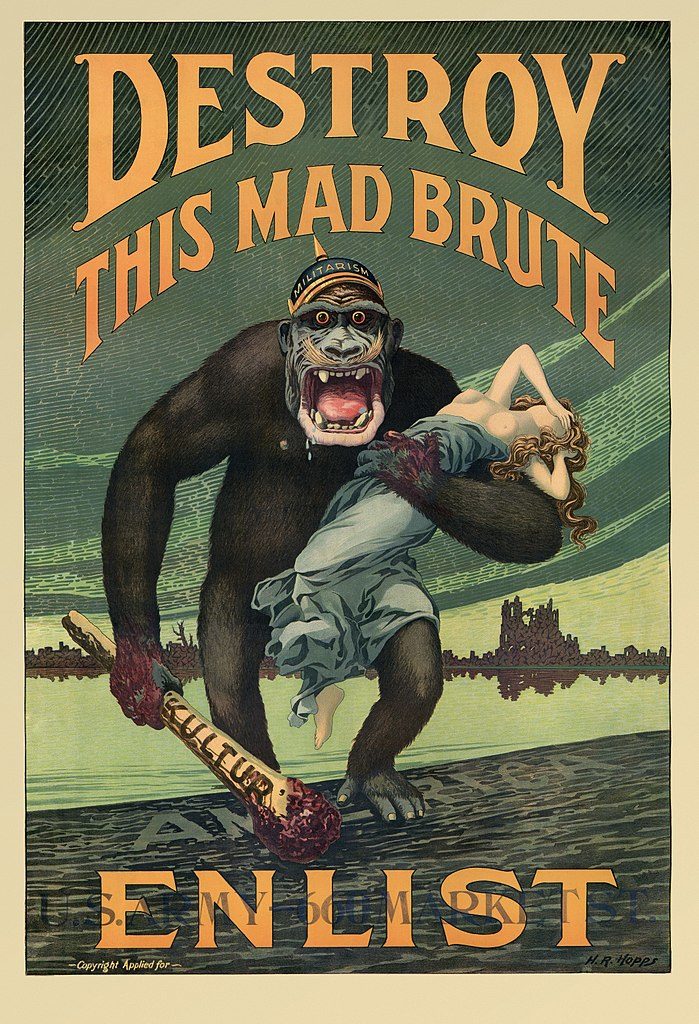

Disruptive innovation has predominantly benefitted the 21th century, western, science fiction audience. Our classic cyberpunk desire for the vindication of the social outlier– the androgynous Sigourney Weaver in a corporate-threatened future of full equality and bodily autonomy, or the replicant who can reclaim a subjectivity beyond his or her social paradigms and slave programming– has since been turned on its anti-establishment head. Scott’s film Covenant saw this come to fruition when the Menippean Anti-hero, Bakhtin’s rebellious, paradigm-questioning literary figure cloaked in the absurd eloquence of language, is fledged into a full sociopath. We saw this in the philosophical and intellectual character of David and his calculated experiments to replace the evolutionarily inferior human species. If Menippean satire is “a genre for serious people who see serious trouble” (Howard Weinbrot), than what is this?

By Covenant, our anti-hero no longer presented the humanistic redemption narrative of the Menippean Nexus 6 leader, Roy Batty, in the original Blade Runner. Instead, Covenant gave its inverse: a regressed society being shown the mainstream values it has come to love and endorse in a world of neoliberal anti-establishment leadership. So much for the underground resistance crouching in the street garbage. The 21st century universe of cyberpunk has been one of well-mannered disruptive innovators of the species, philosophically visionary proponents of transformative wealth models built on slave bodies, and the “technê-Zen” veneered (R. John Williams) institutionalization and naturalization of technological sociopathy. Here is a social darwinist instrumentalism for our post-human age of market-driven measures of social success and impending climate change. In this universe, androids can be humanist while humans can be androids in an inhuman system, conveying either ‘progress’ by any means necessary or a losing sense of civilizational duty. Whose side, Covenant asked of us, before its devastatingly feel-bad ending, were you hoping would win anyway?

David, it turns out, was the only anti-hero we deserved now.

Denis Villeneuve’s sequel fits surprisingly in this updated cyberpunk universe. Like Walter in Covenant, the replicant hero who becomes Joe in Blade Runner 2049 (in contrast to Roy Batty) clearly lacks the eloquent language and especially satire of the subversive, Menippean Anti-hero character. Surprisingly, we find his strain of articulate stream-of-conscious in the tech empire guru played by Jared Leto, drained of all the feeling and trickster-like ability of Roy Batty. Joe, however (like Walter), is simple and humble in his speech, seemingly able to feel but dying suggestively in silence off screen. Robbed of the poetic dialogue expected of the death scene, only a soundtrack bite nostalgic of Roy Batty’s final scene signals a death of redemption for Joe in Blade Runner 2049. Yet the unsentimentally raw, blank slate of Joe’s expression asks of his audience: What do we see through his eyes? What language could possibly be used here to convey the gravity of a moment when power so regularly denies and manipulates the language of our experiences? In this silence, we are perhaps left to only wonder what we would be feeling.

What if it had ended differently? Would Roy Batty’s eloquent speech achieve the same humanizing disjuncture today, or does it really belong now to Niander Wallace, our tech monopoly visionary of the neoliberal age, emptied of any contradiction with the smooth flow of progress rhetoric and sociopathic public morality? Niander Wallace as foil who cannot stop talking makes Joe’s uncharacteristic silence all the more uncanny. According to Jonathan Auerbach, the uncanny involves a “trespassing or boundary crossing, where inside and outside grow confused… reveal(ing) dark secrets hidden within.” Auerbach is talking about film noir here– a highly unsettling sensory genre metabolized into the late Cold War aesthetics of the Blade Runner world. But perhaps we can relate this psychic role of the filmic uncanny to other hybridities explored through expressionist media, where the formal manipulations of sight and sound once conveyed the uneasy clashing of two worlds affectively.

Is Villeneuve’s silent denial of a hero’s dialogue in a death scene, for a Blade Runner audience, purposely estranging? Does it achieve the same, disorienting “uncanny bodies” (Robert Spadoni) that silent film audiences, unaccustomed to sound in their movies, reported with the introduction of Talkies? Film scholar Shane Denson describes how post-Talkie movies of the Thirties like Frankenstein (1931), were created in a period of transition and between the old and new ontologies of silent and sound film media. Denson argues that such films, working after the initial novelty of Talkie exposition wore off, played affectively with the new hybridity of films formalist storytelling qualities. In doing so, these films drew attention to our participation in media: “sight and sound conspire(d)…to encourage the viewer’s medium sensitivity, to coalesce with the perception of a constructed monster.” And what is a sequel, after all, if not a constructed monster of narrative to become conscious of?

“Questions.”

We live in a time of the seductive post-human technologization and normalization of very inhuman institutions, public policies, and person-like entities whose social impacts are all too often screened over with ‘alternative’ narratives of language. Glitches in this flow of mainstream mediated ways of knowing can be more than anti-nostalgic; they can be disruption to the alt-fact hyperreality in the neoliberal 21st century. Are uncanny bodies of the sensorily unexpected (or, even, dissected) what we have left to successfully slow down and stutter our neoliberal ubiquity for hearing chasm-filling speech? Can such estrangements allow us the conscious relationality to once again actually hear and see how we are hearing and seeing each other?

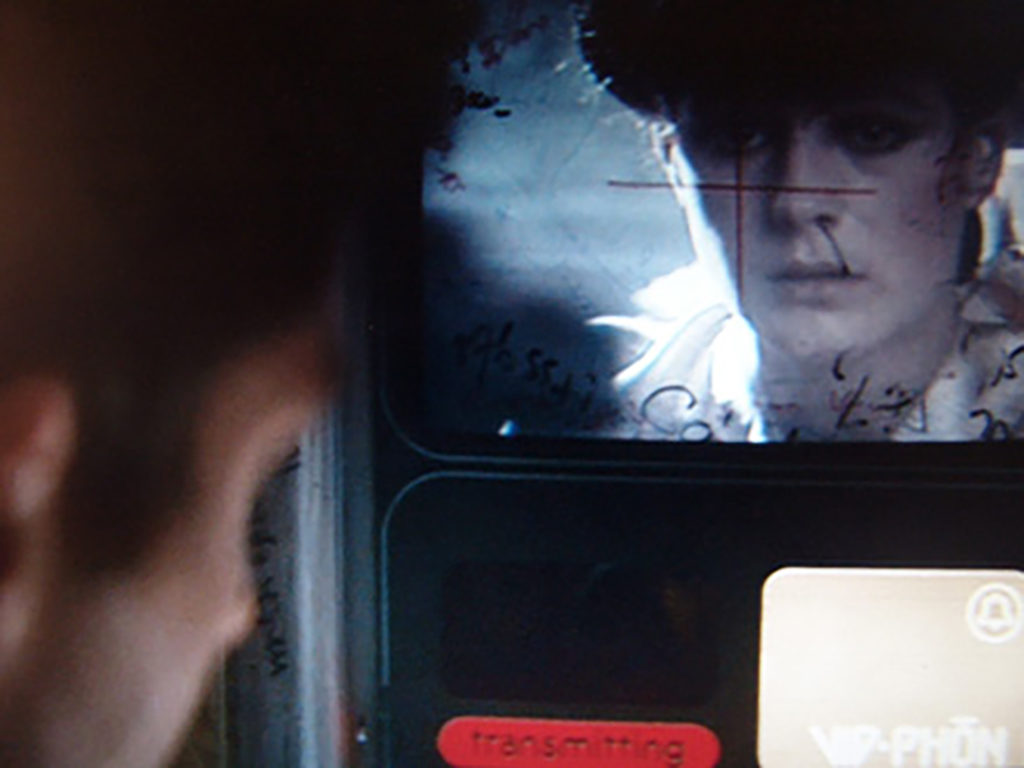

It is convenient to note here that the technological imaginary of the first Blade Runner movie refused ubiquitous surveillance. Blade Runner 2019 even refused a conception of the personal communication device so often credited with fracturing collective sociality in both sci-fi and reality. Decker, for example, calls Rachel from a public videophone in a bar. Whether human or replicant, technological worlding of the original Blade Runner insists on the communications scale of face-to-face human relationality. By the end of Blade Runner 2049 this same scale of technological imaginary in the original film returns. It is the death of one body, the replicant called “Luv”, that seems to end the limitless reach of panopticon technology that helps advance the plot.

Some kinds of love can destroy. Scene from Blade Runner 2049

This act leaves the future of Blade Runner’s Earth yet again to the relations between two, individual physical bodies. With the 1% most likely afloat in the outer world colonies, we might assume this means that it’s up to Us to cross the interface of hyberbaric differences. At a time when love has become perverted with neoliberal logic– instrumental, utilitarian, stripped of its greater sense of equality or duty– it seems that Villeneuve graciously gives us an answer here, if not a fantasy to hold on to. Perhaps one consistency in the Blade Runner franchise is the argument, like that of Junot Diaz on neocolonial oppression (as if it ever ended) and the uptick of white supremacist domestic terrorism, that it is ultimately intimacy with the Other and rejection of the glorified “lone wolf” mentality that must be revolutionary: “Vulnerability is the precondition to contact.” What if being in our present moment requires the vulnerability of silence?

“Listen:”

Nostalgia has come unstuck in time. In Ghosts of My Life, the late Mark Fisher wrote extensively of the threat of nostalgia in postmodern cultural production. Building on theorists Frederic Jameson and Bifo Berardi to explain the bending of new technologies to recycle comfortable and profitable cultural forms for capitalism, Fisher explains how “…the nostalgia mode subordinated technology to the task of refurbishing the old”, not of specific past styles, or periods, but forms of never-fully-present time asynchronicity. Consider it like another outdated, self-reproducing model, ever expanding all around you to stay relevant. Perhaps you can finally see its now, like a loose eye, engineered, removed from its familiar socket.

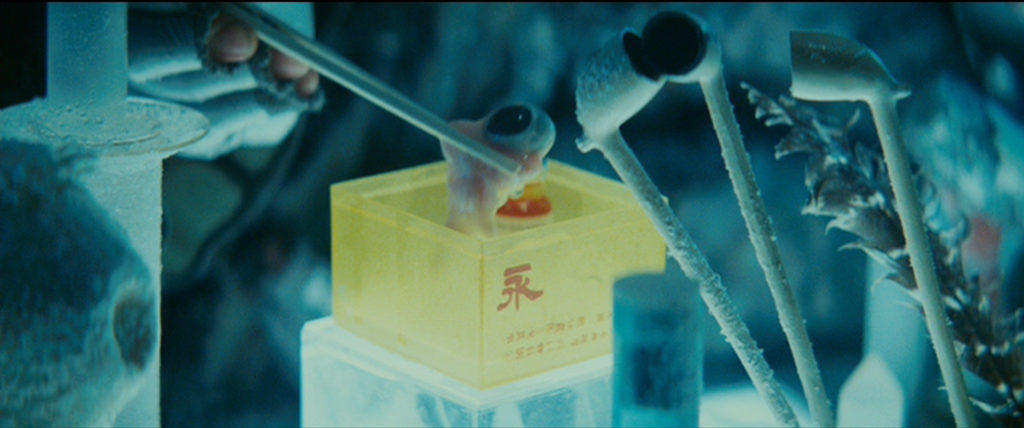

Transgressive fiction has this way of making our boundaries visible in the crossing. The reader may resist its dehumanization, suddenly queasy. Barthes once wrote about the surrealist Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye, a modernist novel from the early mid-20th century which indeed involves a plucked eye and its “metaphorical journey” across other eye-like images. An object, he wrote, “can pass from hand to hand… or alternatively it can pass from image to image, in which case its story is that of a migration, the cycle of the avatars it passes through, far removed from its original being, down the path of a particular imagination that distorts but never drops it” (his emphasis). Barthes felt The Story of the Eye was less a novel and more like poetry. Through its avatars and crossing of sensory metaphors, the eye simultaneously “varies and endures.” Consider the following example of crossing sensory metaphors from the Blade Runner sequel: eyes, cells, tears, rain, leaking, bleeding, blinking, seizing, splashing, drowning, watching, “cells”. And what if this thing we now strangely see so differently is neither naturally born nor autonomous, but a constructed thing?

How eerie.

Eerie like the absence of “future shock” in the futuristic. According to Fisher, nostalgia mode production is an aspect of the “cultural logic of late capitalism” that “…disguise(s) the disappearance of the future” and prevents any real possibility of innovative “rupture”. Nostalgia in our entertainment helps stabilize the “cultural deficits” created under globalization, soothing the simultaneous “exhaustion and overstimulation” of instantaneous and transactional relations we can’t seem to deal with. It fills a high-speed chasm of emotion, truth, and meaning. It denies us the “uncanny” recognition of our temporal futurelessness, left teetering on neoliberalism’s precarity of resources “despite all its rhetoric of novelty and innovation…”

Let’s just be honest here: by the time the Coke commercial hologram showed up in Blade Runner 2049, it was a joke on our desire for even nostalgic product placements.

Nothing changes.

Dipping into the media art world at this borderland, theorist and filmmaker Hito Steyerl writes in “A Thing Like You and Me” about the video that David Bowie put out in 1977 for “Heroes”:

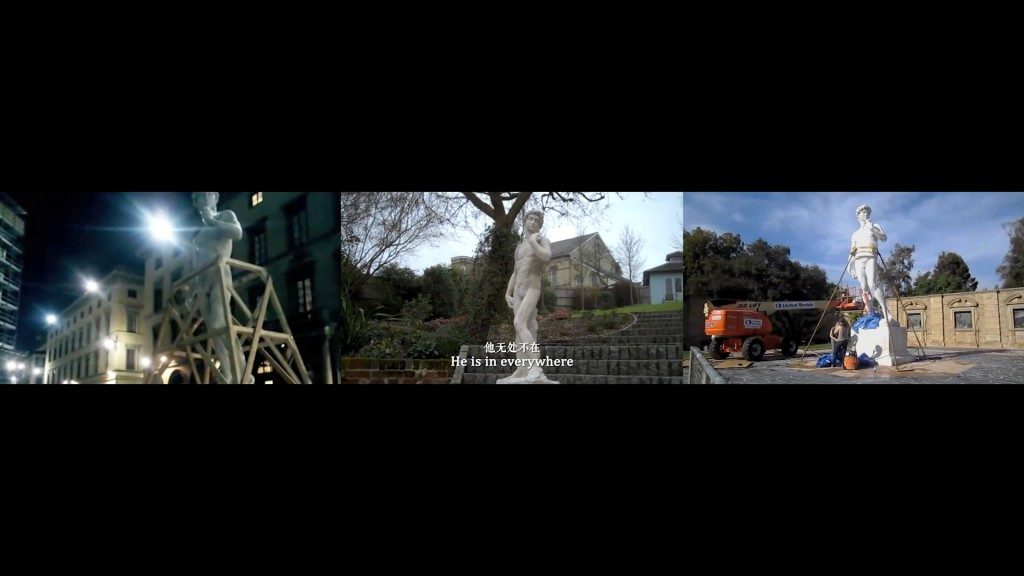

He sings about a new brand of hero, just in time for the neoliberal revolution. The hero is dead—long live the hero! Yet Bowie’s hero is no longer a subject, but an object: a thing, an image, a splendid fetish (…) the clip shows Bowie singing to himself from three simultaneous angles, with layering techniques tripling his image; not only has Bowie’s hero been cloned, he has above all become an image that can be reproduced, multiplied, and copied, a riff that travels effortlessly through commercials for almost anything, a fetish that packages Bowie’s glamorous and unfazed postgender look as product. Bowie’s hero is no longer a larger-than life human being… but a shiny package endowed with posthuman beauty: an image and nothing but an image.

What are we to do when no degree of protest or declaration can make an exploited object be seen as a subject? Where is one to find anti-heroism in all of this? Let us be objects of severe agency then. Models that are perhaps transferrable, but unobtainable. One of a kind and replaceable. Constructed yet autonomous.

Perhaps then we can only view these things in suspension: the need and refusal of nostalgia as liberating human process, the uncanny increments of our cultural evolution to product and media-focused estrangement, the will to see one’s own familiar pixels blown wide open. “Digital information is … characterised by transformation, degradation, circulation,” explains Hito Steyerl in an interview in Rhizome, “but also by its surprising ability to mutate and produce unpredictable results. The glitch, the bruise of the image or sound testifies to its being worked with and working; being passed on and circulated, being matter in action.” Futureless. As futureless as staring into a present ruin, expansive but without destination, the destination without purpose.

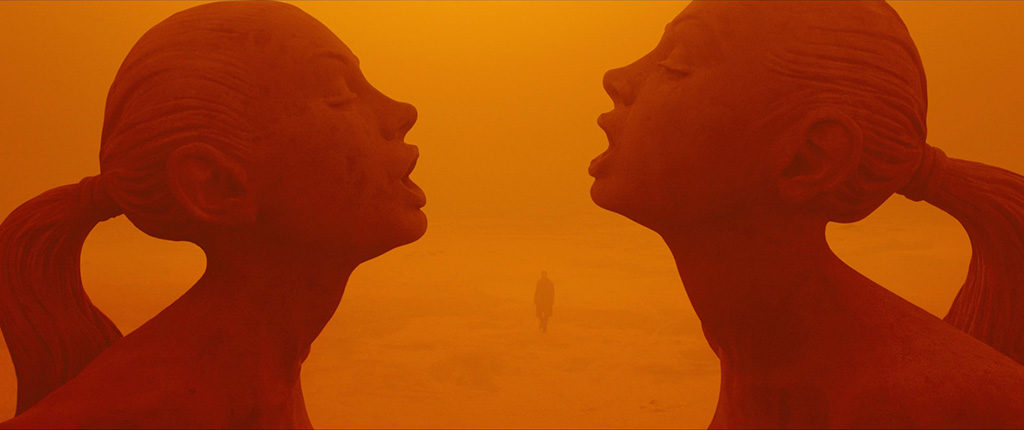

Apropos, then, how our old and new heroes meet in that ruined casino scene, outcasts of white difference (by the future racialization of the synthetic) in an atemporal Las Vegas, framed by primordial Seven Wonder monuments to the our foundational schisms of misogyny (yes I’m also talking about me).

In this incarnated ruin of our stubbornness for cultural mythologies, I was struck by the brilliance of the fight scene, the director literally exploding our pixel expectations of 20th century nostalgia as soon as Harrison Ford makes his long-awaited appearance. The sonic build-up of Decker’s familiar piano in the distance was dissolved by the strange sound of his disembodied voice un-cueing an upcoming appearance in the scene, his visual reveal in that moment of our auditory let down, confusing: Desire misfiring. The ensuing cyberpunk clash-as-fight-scene of 20th century romantic and 21st century post-romantic dystopic characters corresponds to the casino’s hologram interface of an imagined, mid 21st century entertainment technology; all of the expected glamour and nostalgia is allowed to barely seduce us before sputtering and malfunctioning as filmic metascene. Within the plot, these post-apocalyptic hollywood holograms are also a sign of the future sentience to come in the character of Joe’s AI wife, Joi, and a warning that all technology rebels and mutates from initial human intentions, no matter how superficial the design intentions.

My interpretation of this violent casino stage scene in light of a more recent American mass shooting of an ever-expanding, historically singular, and self-containing statistic of “largest ever” is not lost on me. Neither is the choice of mid 20th century entertainers like Elvis and Monroe who notoriously performed like automatons with post-human qualities, their movements in time-space of perfect bodies turning on the master clockwork of a still-industrializing cultural machine before blowing apart, fragmenting. Their avatars echo of consumer-creator bodies in our postindustrial world of 2.0, gig labor, automated economic transactions feigning meritocracy, and a model of precarity demanding the inhuman perfection of individual responsibility for every movement which can shudder, glitch, and explode on other people all too frequently.

This failure is that of speculated, plotted, rationalized, and technologized courses whose error cannot be properly imagined, only realized and refused in the ruins of a short-sighted economic-cultural imaginary. Our looking back on dystopia hints at our present expectations only.

“Irreversability.”

“It’s difficult for someone of my generation to break free of the intellectual automatism of the dialectical happy ending”, writes Bifo Berardi about irreversability. He compares this “taboo” concept to the “silent” apocalypses of our endless growth mentality, like Fukushima, corporate disaster unaccountability, socialized scarcity adjustments, and our silence on fellow human suffering. His book, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, speculates a “process of subjectivization” for the return of solidarity to a “social body”. This is the social body being culturally reprogrammed away under our collectively isolated movements of relentless market-driven consumption and precarity (individualist and systemic, like the fascist choreography of Kracauer’s Mass Ornament, or the Las Vegas showgirl spectacle). We might consider these grinding automaton gears of consumption and precarity the logics of late-terminal capitalism for clarity, it’s refusal a glitch in our clockwork performance. What is one to do for a postmodern exit other than to shudder, to write off the page? Ultimately, Berardi’s book leaves us more with a hope for our relational redemption from neoliberal culture through “sensibility” than it does with answers.

Blade Runner 2049 may not have been the sequel people wanted, but its confrontations with its own expectations provided a little of the things we need: a vision of the finite and anthropocene, a postmodern exit to the endless technologized avatars of getting what we think we want, our profound silence of the awful price. The film’s self-aware, nostalgic ruin leaves us with a little less of the typical sequel’s fourth wall, and an identification with its lonely bodies, caught in action between clockwork cultural predictability and its refusal. These bodies may or may not have the capacity for real love, but they are vulnerable at least to a larger sense of duty that Humanism, in all its universalizing failures, really needs. In this hybrid space of ontological awareness of the facets of knowing, experience and process, Blade Runner 2049’s success was inbetween all the things it could never definitively be. We too might realize that ‘doomed to fail’ may only be our insistence on choosing from a predetermined relational binary.

A distant song floats into the scene.

…“Though nothing, nothing will keep us together…”

When I saw Blade Runner 2049, in was at one of the remaining four hundred or so drive-in movie theaters left in the United States. I went back in memory to my kindling college interest in what I study and consider Avantpop, surveying the changes, considering its meaning and meaningless in my social development as a scholar: working class, woman, white, heterosexual; accepted and refused and abused entrances. The sequel came less than thirty years later in the revolution of a world for me, but I travelled farther to get there, out to a dark semi-rural drive-in beyond the city, and a memory of popping in a VHS tape almost 20 years ago simultaneously. I time-traveled mass media ontologies. I posted an instagram picture. It was semi-romantic nostalgia for me. But I still see that there is only now to change what we’re doing. And it is terrifying.

It’s quite an ending, to just die in silence, isn’t it?

But the fourth wall was always part of this, you know.

The word speculation is defined as ‘the forming of a theory or conjecture without firm evidence’. The act of speculating was predominantly popularised with the rise of the stock market, however, recent environmental destruction and technological advancements have prompted a rich pool of speculation about the future of our planet, our species and our connection to other facets of life. Tomorrows: Urban Fictions for Possible Futures is such an exhibition, compromised of imaginative narratives speculating the future of our cities – how they will look, how they will function and the degree by which these cities will form new types of citizens directly operating within the network of that future city. In the context of the exhibition’s content, fiction is transformed into mighty medium, utilised to share the ideas of thirty-two individual and group projects. These projects envision and share their anticipation for the future as a means of addressing socio-economic, environmental and other issues we face today with a goal to reassess of our presence on the planet.

Tomorrows was curated by Daphne Dragona and Panos Dragonas, and organised by the Onassis Cultural Centre in Athens – a city experiencing continual fluctuations since the end of World War II. The location itself, Diplarios School (a place of former learning and listening), stresses the aspect of sharing and the telling of important narratives determining the shaping of the future. The exhibition begins with a didactic, yet absolutely accessible approach to understanding the notion of developing a future city. As a starting point, the exhibition borrows and advances the ideas of Doxiadis’ speculative plans of an Ecumenopolis from 1959-1974. More particularly, we must take into consideration the term ‘ekistics’ which was coined by Doxiadis in 1942 as derived from the ancient Greek noun οίκιστής, meaning a person who installs settlers in a place or creates a settlement.

In order to create the cities of the future, we need to systematically develop a science of human settlements. This science, termed Ekistics, will take into consideration the principles man takes into account when building his settlements, as well as the evolution of human settlements through history in terms of size and quality. – Doxiadis

Doxiadis was a visionary and the decision to reinstate his work within the framework of the exhibition was incredibly rewarding for visiting audiences. He anticipated that cities were to become more than global in order to accommodate an ever changing human and non-human environment – as one huge network perhaps out of the control of human capacities. Ecumenopolis is installed on large hanging panels in the first room of Tomorrows and acts as a reference point to the five themes developed: Post-Natural Environments, Shells & Co-Habitats, Networks & Infrastructures, Algorithmic Society and Beyond Anthropos. These themes resonate to the acceleration of our urban development hybridising the natural with the artificial, future network infrastructures of our habitats becoming dependent on inhuman mediation, the possibility of an omnipresent and undemocratic structure within the city through the interdependence of economy, ecology and technology, possible forms of organisation to encourage modes of co-existence within the city, and technological singularity as challenging human sovereignty within our future cities. Doxiadis work gives way to the participants who are primarily artists, architects and designers, to explore these imminent futures of our present planet’s landscape.

Coastal Domains is an on-going research project exploring the future landscaping of coastal territories in the Northeastern Mediterranea facilitated by Demetra Katsota along with 4th and 5th year students at the Department of Architecture, University of Patras. The installation Coastal Domains was made up of sixteen books, acting as case studies, secured on the wall and a ladder to reach them, encouraging brave visitors to climb and read them – a curatorial decision simultaneously inspiring participation and learning as it is explicitly reminiscent of old archival libraries. The 7th book in the series of sixteen engaged with the coast land of Kanoni and its Sea Lane on the island of Corfu, the research undertaken by Stella Andronikou and Iasonas Giannopoulos. As with each book in the series, the research was made up historically archived material, such as cartographical maps from different centuries and topographical material including the arrangement of roads and different fauna on the island thus unveiling issues of coastal development, the implications of an upsurge of tourism in the 1970s and possible environmental issues. Coastal Domains speculates and designs possible structures for the reinforcement of sustainability, devising various strategies that can protect the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea.

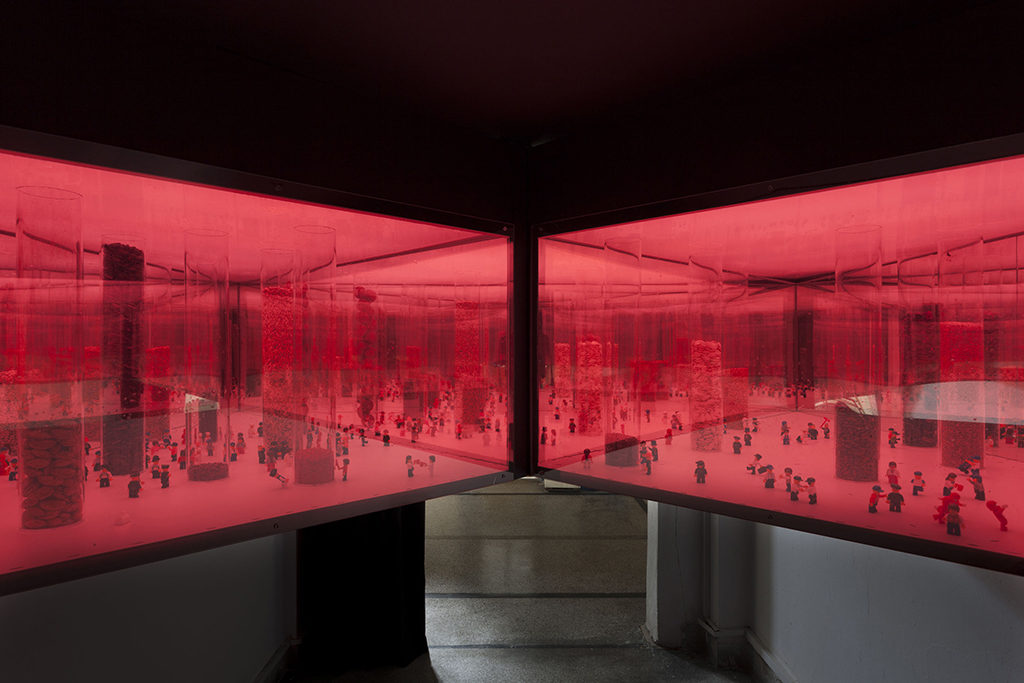

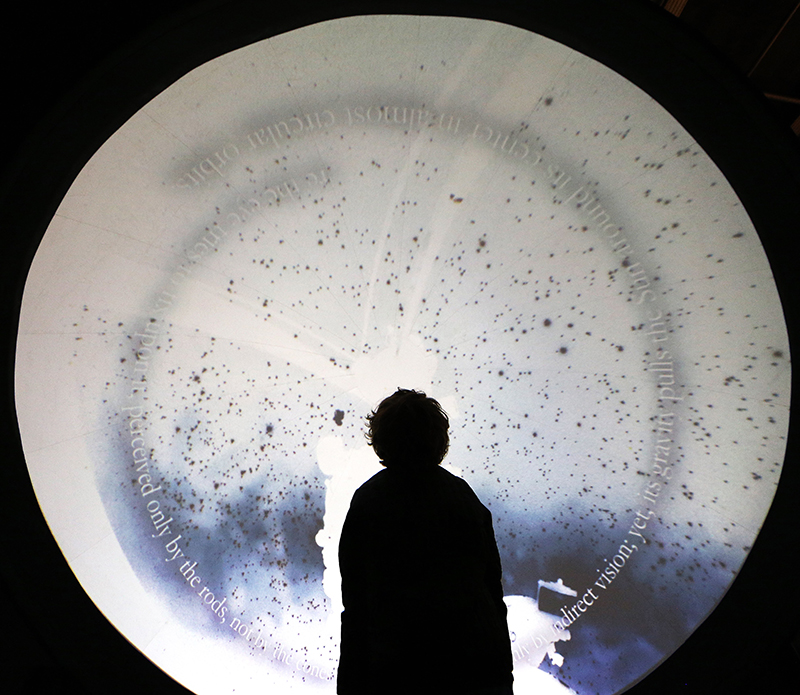

Tomorrows is particularly involved in engaging its locality of the Mediterranean, treating it as a microcosm for observing the implications of the future’s development. Silo(e)scapes by Zenovia Toloudi envisages a hybrid of a seed bank and museum for Mediterranea plant species as a tool inspiring a sharing economy. The installation of Silo(e)scapes required the audience to cradle themselves into the centre of the structure in order to experience the transparent silos-displays of the community LEGO labourers sharing their local seeds at the seedbanks. The audience suddenly find themselves in a possible future reality, all encompassing of agrarian sounds and 360 views of kaleidoscopic mirrors that trick perception of your depth of field. Almost theatrical, Silo(e)scapes is immersive and constructs a space where the audience is directly in conflict with the imminent shortage of supplies due to harmful environmental issues and increasing urban development. The audience becomes entirely physically encased in Silo(e)scapes, as a result inciting the plausibility of this future reality.

A Cave for an Unknown Traveler by Aristide Antonas introduces another form of habitable landscape for the possible future. The installation is structured like a ‘fake archaic cave’ that is buries inside it a structure as luxurious as a modern hotel room, invisible to the eye from the outside. The installed structure of the cave is complimented by a large sketchbook denoting the various features of the Cave for an Unknown Traveler. Antonas’ work brings to mind the concept of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. The infrastructure and services within Antonas’ cave can be taken in context of the prisoner’s in Plato’s cave perceiving shadows as objects when in fact they are a mere representation of their physical form grasped by our mind. In this context, Antonas’ invisible cave begins to resemble an imagined safe haven for a traveling passer-by.

The highlight of Tomorrows is undoubtedly Liam Young’s commissioned work Tomorrow’s Storeys – a two-channel video installation isolated in a dark room with modular seating. The title of the work acts with a double meaning as in storeys of a building and the stories being told through them. The content, or stories, narrated in Tomorrow’s Storeys were first conceived in a workshop in mid-March as part of the programming to the run-up of the exhibition opening in mid-May. The workshop of visual artists, authors, photographers, directors and architects produced an abundance of local stories in the future city of Athens, particularly a future Athenian apartment block. In Tomorrows Storeys all apartments blocks have the ability to reorganise themselves automatically – modular entities like seating in the installation. The videos convey intricately detailed shots of the façade of these apartments as well as its contents recalling film shot by aerial drones and ads for IKEA products. The audience act as omnipresent eavesdroppers drifting from storey to storey into the conversations and local happenings in these apartment blocks. These apartment blocks of the future have found a way to reorganise themselves where Athenians are not given a minimum basic income but instead a minimum basic floor area – the occupants do not own an apartment but a specific volume of space which does not have a fixed location. Amongst these stories of shifting permanence and impermanence one stood out: that of an old grandmother dying and the family arguing about who takes over her volume of space as one character cries quite humorously “Can’t you wait until the funeral?!”. Tomorrows Storeys are part of a city where bots constantly reorganise your living in a form of urban computation according to best fit the needs of its citizens. In this way, a living space becomes a temporality, alluding the audience to question if their home is real if it always available for smooth transition to another space.

Within urban infrastructures are the human entities contained within them, as Young’s work emphasises, however some of these are becoming increasingly inhuman as the theme of ‘Beyond Anthropos’ suggests. The notion of inhuman or machinic entities being able to replicate human form and intelligence is common and highly popularised since the 1980s as films such as Bladerunner introduced global audiences to ‘replicas’. Today, AI is becoming so intelligent that it urges inventors such as SpaceX and Tesla CEO/founder Elon Musk to warn for correct precautions to be taken when engaging with AI, in fact comparing it to ‘summoning the demon’ and naming it ‘our biggest existential threat’ in the 2014 AeroAstro 1914-2014 Centennial Symposium by MIT. The work of !Mediengruppe Bitnik, coming only a couple of years after Musk’s interview, exemplify the relationship between human and machine. Ashley Madison Angels at Work in Athens is a research project initiated after the data of the Canadian online dating service was leaked in 2015. The leak revealed that Ashley Madison had created 75,000 female chatbots that catered to 32 million mostly male users, engaging them in costly internet intimacy. In Athens, there were 165 fembots for around 22,910 registered users. The installation was comprised of seven of these 165 fembots active in Athens, and were installed in a room dimmed by a fluorescent pink light with screens on tripods similar to average human height and alluding to a physical form. The fembots, programmed to be of different ages, utter pick-up lines they are allocated from a predetermined list to the 22,910 registered users who could not distinguish that they were talking to a machine and not a real person.

Tomorrows does not wish to present us a future as a prediction or as a form of critique of these technological, environmental and urban developments. Rather, it presents the future as an on-going participatory project, as a tool that can be utilised to examine who we are and where we are at in present tense, as well as where we could be potentially going. These urban fictions of our possible futures, are a speculative activity with the capability of making us more aware of the changes that have taken place whilst simultaneously illustrating the changes that are afoot. Tomorrows was a show that took place over six months ago, but its value to the discourse of the future will remain timeless for decades to come.

This is the third of three pieces on people who are posting work to the photography sharing site Flickr [1].

In this final article I look at the work of Karin Rudolph

. Rudolph is a Belgian photographer, currently living in Athens, where she works as a wedding and event photographer and raises two teenage sons. In addition to her work for pay she makes an ongoing series of ‘personal’ images which she regularly posts to the photo sharing site Flickr.

I ask her to send me some images from a wedding job and she does.

It is a job she is clearly good at—everything is beautifully shot, nicely framed, sharply in focus (when sharp focus might be thought necessary), but there is that extra something that comes with a good portrait photographer, which I can only describe as fellow feeling. A fellow feeling which elicits transparency and a willingness to risk vulnerability from the subject. I’ve never met Rudolph but it’s clear that her personality, her way of being, is a player here.

There’s also a sharp curiosity at work—a hunger for the way the world looks and with Rudolph this seems to become attached to particular objects, creatures (some human, some not) and roles. There was a dog at the wedding in the images she sent me. The wedding took place outdoors and the clearly much loved animal figures in a number of the shots. It’s as if at one point R becomes fascinated by it and we get shots where the all humans are cropped (in the shooting; she doesn’t crop after the fact) down to the waist and the dog becomes central (although a small child has a supporting role here too since he necessarily evades the crop/frame wholesale). We get a dog narrative. Then a bouquet catches her eye and we get a bouquet narrative, the wedding filtered through a non-human being or an object. Motion—a sense of the moment before and the moment after being necessary, if hidden, components of this still image—is a key underpinning of so many of these images, particularly in relation to these micro-narratives.

In a photographer less manifestly gripped by the facts of our fragile human being and ways in the world one might call some of her approaches formalist. It is certainly true that rhyme, echo, geometry, continuities and disruptions of line, shape and colour play a highly significant role in the structuring of her images but one of the driving forces of R’s work is that it constantly moves to dissolve any artificial divide between content and form. Yes, her eyes seek pattern; yes, this or that organising device might order an image but this never obscures our awareness of the facts, feelings and relationships portrayed or implicit there. Also—we humans are formalists, aren’t we? We’re pattern seekers. We play. Were you never fascinated as a child by mirrors, by the world turned upside down by hanging from your legs or by the cropping or heightening, or focus) achieved by looking through the cracks in your fingers? Of course you were. As we grow we perceive the whole world through a complex dialectic of what is presented to our senses on the one hand and our burgeoning sorting and structuring principles on the other. We are of necessity creatures of content and form together and one surmises that this is what makes us creatures of art too.

I’d been writing and thinking about this piece for a few months, on and off, and I’d got to a second or third draft when it hit me with a thud, a jolt, that hardly any of the recent images have titles.

The fact had just sailed under my radar, curiously, since I’ve argued and will again, that insofar as we can talk about meaning in a photo (or any visual artwork) this possibility lies in a network of references and comparisons which ineluctably involves talk, writing or both. Language. Further, that visual art is best seen as something humans do (emphasis on both words) than as the usual set of isolable ‘in and of themselves’ objects (which isolation is a fiction, at best an analytical convenience). And then it struck me ( I was being struck a lot that day) that there is something about these images that fights back against language—they’re often cross genre and resist categorisation and there’s a sense in which the easiest approach to what’s in them is simply to list it, and finally to say that this image had these things in it under this kind of light from that angle but, of course, this is far from satisfactory and at root there is something far transcending taxonomy or description going on. But –dammit! –I can’t help feeling it is as if the images (placed as they are in the sequence formed by Flickr) are calling out, hailing each other. I don’t know why, but forced rhubarb, a most unlikely image, is the one which springs to mind and persists, as if the absence of the immediately adjacent language of a title somehow forces the set of glorious but hitherto mute images to invent speech.

Anyone who has ever taken an un-posed image of a human being on a fast shutter speed will be cautious about ascribing emotions or characteristics to the subject on the basis of what is revealed. As in so many other ways, the very small, the very distant or unreachable, animal locomotion, the photograph reveals things beyond our normal ability to see or grasp them. One of these things is the curious plasticity of the human expression and how in our interactions we read this in sequence, in time, together with a host of other clues, aural and visual, to make sense of what is going on, to try to understand both what a person is doing and to surmise what they might be feeling . (Of course the opposite of this, the posed image, brings its own problems too.)

When we think hard and soberly we cannot but be convinced that the photograph alone, an impossibly small fragment of time, does not allow us enough evidence, that it is somehow unanchored in the world.

And yet, the desire to draw conclusions, to make comment, is certainly strong in us and each photographic image of a person, especially the striking and affecting ones, comes with a very strong sense that we are able to do so.

What can we actually say about the still photographic portrait, both in general and in particular cases?

One thing we might say is that the single image’s apparently complete account of a human being, based upon a fleeting expression (and perhaps the fleeting expressions in response of others and maybe also the presence of contextualising objects or other clues) suggests at best, a class of possibilities. This single image evokes a range of other possible images and moments in the world at least one of which must correspond to our strong intuitions about it. So even if we were able to establish the facts of the matter in this particular case and it made a lie of our emotional response , nevertheless that response represents a truth and somewhere, perhaps quite often, in the world, situations occur, have occurred, will occur, which correspond to this truth.

And it seems to me that it is this instinct for general human truth, allied to the particularity of light, line, composition, of other things depicted, which manifests in the eye-and-heart-catching-ness of the resulting final image.

A strong way of putting it would be that any portrait is just as much a work of fiction as a novel but that as we would not wish to deny something called ‘truth’ in the novel ( you might—I see no point to the thing otherwise) in the portrait we work our way back to truth.

And at least for me it is the photographer’s—and here, now ‘the photographer’s’ means R’s—capacity for empathy, for narrative, for understanding of the world and the wonder and the oddness of its inhabitants that makes her such a good portraitist (and let’s not forget, too, simply having done the thing a lot —this is often underrated nowadays.)

Do I know whether the Orthodox priest at the wedding table was a kind man? No. I don’t. I cannot. Is kindness manifest in the photo, is the possibility of kindness in the world reasonably asserted in it? Do I know more about kindness thereby? Absolutely.

There’s a black and white image, taken, I think, at the place where her teenage sons practice their footballing skills which feels like a short story or perhaps a collection of short stories, each cued by the various human presences which form at one and the same time a large (in how they capture our attention) and a small (in how much actual area of the image they occupy) part of the entire image.

It also has a most clearly defined geometry—three strips, the topmost being the practice field itself, the middle appearing to be a road like depression running between the photographer and this field and the lowest a pavement of some sort on the other side of that ‘road’. The almost bizarrely long evening shadows of R and a companion (and the horizontal distance between shadows is nicely ambiguous on the exact relationship between those shadowed) stretch forward into the image. The vertical grid adjacent to them, with a gap in the centre picked out in shadow too, suggests they are standing at a pedestrian gate to the place. I imagine the figure at the viewer’s right is R as the arms appear to be raised in a photo taking action.

(The image thumbs its nose at genre—it is oblique self-portrait, landscape, social history, portrait and exploration of geometry and structure all at the same time.)

Shadows aside, the figures which catch my eye (what about you, so much to choose from or are you constrained in a similar way to me by something in the way the image is structured?) are the short stocky man in motion, walking away from us at the image’s far right top strip foreground. There’s a delicious swagger and confident openness about him.

Has he passed through the gate where R stands? Did he greet her?

The second key (perhaps because nearest?) figure is the young man, top strip, viewer’s far left, again in movement, this time almost certainly certainly sports related. Is he pursuing a stray ball? Running to greet a friend? Engaged in some sort of running warm up/exercise? As we strain to see, our relationship to the image’s scale shifts and we begin to realise just how many other figures he opens up to us—there are at least six either standing or seated in those little sheds at the field’s side between him and the left edge of the nearest goal net—each an enigma of a small but definite kind—and when we move rightwards from them we realise (and we have to move closer in, look differently, at the image to see this) just how many people there are in some sort of action here. As we move out again we are stuck by the contrast between the contemplative calm of the giant shadows and the anthill busyness of the young men. And here’s another thing. This is such a male photo. (With the exception of the photographer and I think it’s only because I know she is female that I read her as such. Then even as I write this I notice the slight head-cocked-to-one-side quality of aficionado-like attention in the head of the left shadow—and why do I think that might clue maleness? What does that say about me?) Oh! Layers and layers of fact, of presence, of things to enumerate and puzzle over. So much! And this before we take the thing as a totality—geometry, inhabitants, shadows, activity, motivation, time of day, distant trees, weeds and barren ground, a sky whose colour we can only guess from the fact we know there is evening sun. And that totality is the hardest thing to compass in any way other than an intake of breath or shiver down the spine. Enumerating the contents helps (although it’s not essential to the immediate affective apprehension of the whole—that just happens) but it’s the inexplicable (not a value judgement—literally inexplicable—simply, ‘This is what R did’) decision to frame those contents in that way—the bit of the process which defies words—that makes this and so many other pieces by her so powerful.

5.

A ravenous eye.

She has a ravenous eye, constantly tracking the scene in front of her and hungry for detail. This hunger does not distinguish between content and form. Whatever is human, whatever stirs affect or curiosity—whether pattern, rhyme or echo, or ethics, or suggested human warmth or frailty, this is swallowed up and processed by heart and mind in turn

The resulting images bear the strong feel of certain, almost objective, structuring principles—that following of object or creature within a scene, the use of rhyme and echo. Two further categories are geometry and colour (and nothing here is pure, there are no essences, sometimes blocks of colour impose an extra, parallel geometry upon a scene whose first order sense—whether it be human beings in action or traces of interpretable human activity; buildings, signs, the street —apparently lies elsewhere.) The key thing about all these structuring principles is that they are found, excavated, discovered, seen—not made. They happen in parallel with, arise out of the actions and feelings of, human beings in this world, the only one we have.

Because she is someone who has lived, fully, in that world, for a fair time, because her hunger extends beyond the visual (she always has a book on the go and the range of these is impressive), because she has a number of languages and is at home in at least three cultures, she makes images which are connected and re-connected by hundreds of threads to things we ourselves might have read and thought or experienced and talked about. Further, it is impossible to imagine that the fact she is a woman living in a country not of her birth, where she has learned a different script, different ways of talking and being, where she works in part as an image maker for hire and constantly both connects and holds separate that work for pay from own ‘own’ work, at the same time as raising children by herself, that these facts are not also somehow foundational.

For a long time I have struggled with how to attach the word meaning to image. It is too easily and glibly used. An image never ‘means’ a single thing (unless it is the poorest of images and even then the human capacity for/delight in ambiguity sets to work to disrupt this) What is evident in Rudolph’s work is networks of evoked meaning, memories, feelings.

Her way of being in the world, this following her eye and nose, means that there is a kind of metonymy purged of any attempt at system—here is a dog or child or chair or window. Here are the things which necessarily were near it at a moment in time and this is how they were disposed. There was reason and there was randomness. Parts of the disposition were beautiful. (What do I mean by beautiful? They move me, they fill me with a joy that cannot be reduced to words though it perhaps can be limned by various combinations of words, combinations potentially infinite which always nearly but not completely fail.) Parts of the disposition were stark or threatening or at least worrisome. The bringing together of all these parts—worry, beauty, pattern, action—into an image framed, bounded, lit, by the laws of the heart and the laws of the intellect now pulling one way, now the other. The work about the world is itself part of the world. We are not alone. No person is an island. We can read each other’s thoughts. We can feel each other’s feelings.

The words and the image and human heart and human history dance ever outwards and outwards. What does an artist do but always start to write the whole history of humanity in the world?

Through our interactions with digital devices and systems us humans are now a diverse resource to other humans and machines. And we are changing in accordance with the processes and demands of contemporary, technological market systems, designed to extract as much data from us as possible. In his recent article Our minds can be hijacked, Paul Lewis of the Guardian revealed that those in the know, those who helped to create Google, Twitter and Facebook, are now disconnecting themselves from the Internet as, like millions of people in the world, they are feeling the effects of addiction to social networking platforms, and fear its wider consequences to society.

The hazards of this kind of tech-contagion have been the staple food of sci-fi for decades – a mysterious woman shares a strange but simple VR game in the 1991 episode of Next Generation Star Trek, The Game. It spreads like wildfire, taken up with enthusiasm by the crew, only later revealed to be a brainwashing tool invented by an alien captain to seize control of first the ship, and then all of Starfleet. Let’s look at ourselves for a moment – if we can tear our gaze away from our screens. How has our public behaviour changed – on the streets, on public transport, in buildings and parks? Our attention transfixed by our devices, online via our phones and tablets – bumping into each other, and even walking into the road endangering their own and others’ lives.

Professor of psychology Jean M. Twenge studies post-millennials and argues that a whole younger generation in the US, would rather stay in doors than going out and partying. Even though they are generally safer from material harm they are on the brink of a mass mental-health crisis. She says this dramatic shift in social behavior emerged at exactly the moment when the proportion of Americans who owned a smartphone surpassed 50 percent. Twenge has termed those born between 1995 and 2012, as generation iGen. With no memory of a time before the Internet, they grew up constantly using smartphones and having Instagram accounts. In her article Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation? Twenge writes “Rates of teen depression and suicide have skyrocketed since 2011. It’s not an exaggeration to describe iGen as being on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades. Much of this deterioration can be traced to their phones.”

Internet addiction is like having your head perpetually inside a magical mirror of hypnotically disembodying power #addictsnow pic.twitter.com/DFkl1jaKER

— furtherfield (@furtherfield) August 31, 2017

From the #addictsnow Twitter commission by Charlotte Webb and Conor Rigby, 2017

We offer three features as part of Furtherfield’s 2017 Autumn editorial theme of digital addiction, in parallel with the exhibition Are We All Addicts Now? at the Furtherfield Gallery, until 12th November 2017. Artist Katriona Beales has developed the exhibition and events programme in collaboration with artist-curator Fiona MacDonald: Feral Practice, clinical psychiatrist Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones, and curator Vanessa Bartlett. She explores the seductive qualities, and the effects of our everyday digital experiences. Beales suggests that in succumbing to on-line behavioural norms we emerge as ‘perfect capitalist subjects’ informing new designs, driving endless circulation, and the monetisation of our every swipe, click and tap.

Firstly we present this interview with Katriona Beales* from the new book Digital Dependence (eds Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones, 2017) in which she discusses her work and her research into the psychology of variable reward, “one of the most powerful tools that companies use to hook users… levels of dopamine surge when the brain is expecting a reward. Introducing variability multiplies the effect” and creates a frenzied hunting state of being.

Pioneer of networked performance art, Annie Abrahams, creates ‘situations’ on the Internet that “reveal messy and sloppy sides of human behaviour” in order to awaken us to the reality of our networked condition. In this interview, Abrahams reflects on the limits and potentials of art and human agency in the context of increased global automation.

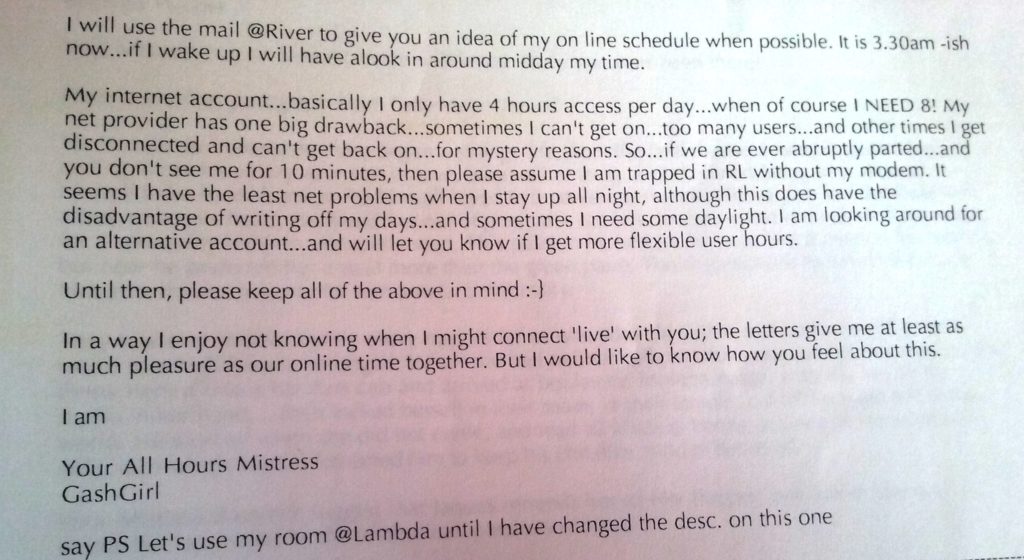

Finally a delicious prose-poem-hex from artist and poet Francesca da Rimini (aka doll yoko, GashGirl, liquid_nation, Fury) who traces a timeline of network seduction, imaginative production and addictive spaces from early Muds and Moos.

“once upon a time . . .

or . . .

in the beginning . . .

the islands in the net were fewer, but people and platforms enough

for telepathy far-sight spooky entanglement

seduction of, and over, command line interfaces

it felt lawless

and moreish

“

And a final recommendation – The Glass Room, curated by Tactical Tech

Tactical Tech are in London until November 12 with The Glass Room, exhibition and events programme. A fake Apple Store at 69-71 Charing Cross Road, operates as a Trojan horse for radical art about the politics of data and offers an insight into the many ways in which we are seduced into surrendering our data. “At the Data Detox Bar, our trained Ingeniuses are on hand to reveal the intimate details of your current ‘data bloat’; who capitalises on it; and the simple steps to a lighter data count.”

*This interview is published with permission from the publishers of the book Digital Dependence edited by Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones, available to purchase from the LUP website here.

‘We had a dream last night, we had the same dream'[1]

I’m looking for a new love, a mouth that promises . . .

once upon a time . . .

or . . .

in the beginning . . .

the islands in the net were fewer, but people and platforms enough

for telepathy far-sight spooky entanglement

seduction of, and over, command line interfaces

it felt lawless

and moreish

wandering into the maw of the feast

in the realm of the Puppet Mistress, 1995

speech acts, sex acts, strange pacts

squirreled away in buffer logs and pasted Pine trails

weaving 1001 nights of Puppet Mistress tales

never on the down-low

was this most splendid DIWO

permission granted,

always, all ways

read write execute

reeds rites hexecutes

I was Alice clasping the little bottle labeled ‘DRINK ME’

becoming-Sufi, heady with some love-like like love emotions

juiced up jouissance

psychosomatic investigations

psi psi psi

ψ ψ ψ

sigh

seeking the difference/s

if any

between a suspected false binary

Virtual — Real — Life

difference

différance

different ants

worker queens snorting lines of flight

‘IRL’ (‘in real life’) prefaced conversations

whereas no-one said ‘IVL’

VL was the norm

so no need for a distinguishing preposition

whereas you needed to go somewhere, in, purposefully,

to get (back) to real life

Back to life, back to reality

Back to the here and now yeah

. . .

Back to life, back to the present time,

Back from a fantasy

Soul II Soul 1989

I ask Monstrous_Gorgeous (aka t0xic_honey @Lambda) to trawl through my stash of Moologs and MOOmails from my Lambda life, to search for signs of digital affliction. t0x’s forensic gaze (who eirself had been a keen Lambda queercoder back in the day) might be illuminating. GashGirl and her morphs(GenderFuckMeBaby, Madame_de_Clairwill, doll yoko, Rent_Boy, et al) had run amok and amongst simultaneous games, switching genders, personae and communicative registers as easily as children playing ‘let’s pretend‘. The best game was that between Puppet Mistress and her Puppet (aka YourPuppet). Today the language seems quaint, The Difference Engine meets The Pearl, steamy stream punk. All bonnets, bronze and tiny buttons.

Wolf.

Homunculus.

Ghost.

Doll.

It’s a sky-blue sky.

Satellites are out tonight.

Let X=X.

Laurie Anderson 1982

does X=X?

or VL = zero?

with RL the one of ones, the one and all,

the only one (of all possible lives)

I think not!

t0x phones me, recounting episodes that I cannot recall, but which are so in-character I have for sure they happened. Like when I punished My Puppet severely for daring to speak with t0x about her in-MOO peep show. Now we can laugh about it, now that the field lies fallow, but at the time I was furious. Living at (on? in?) LambdaMOO did not diminish affect or emotion, but rather it intensified thought, sensation, desire, need.

can we call this addiction?

or obsession?

compulsion maybe?

I chatted this week with Jon Marshall, my anthropologist friend and author of Living on Cybermind (an ethnography of a mailing list), about how it felt more like a habit than an addiction. He talks about personally accumulated habits and socially accumulated habits. Humans are constructed of habits, including the habits that you build up around internet use. We recall the ‘Rape in Cyberspace‘ event at LambdaMOO; ‘that story becomes a myth that guides behaviour’, suggests Jon. My habit would not have led to such intense encounters, if all of us lot had not been sharing a gravitational pull to the glimmering galaxies of spiralspace. My twin talks about habit lying at the junction of nature and nurture, opening up another line for future investigation. Never enough time. Instead I loaf around on Netflix with Terrace House: Boys & Girls in the City.

for me the habit of MOO (Mu) was quickly formed,

and devastating to desert

Ripping through a damaged heart

in the best of daze

circa 1992 93 94 95 96

(=3)

I didn’t leave home

a charming house with a white peach tree, goblin hut

and a dial-up 14,400 modem usurping landline’s phone functionality

for years I burrowed in through a borrowed log-in

J (aka connie_spiros @Lambda) pounds on front door to kick me off

later I jumped onto a free account offered by community provider apana

through its tiny sibling sysx (thank you Scott and Jason)

part of a tribe meshwork of cool sysops animating .net

motivated by the conviction of net access for all

xs4all

excess for real

S (aka Quark @Lambda) told me how depressing it was to leave home at 7.30am seeing me already jacked in, and to find me still in pajamas at dinner time, a sure sign that I hadn’t stepped away from the computer all day.

frequently he’d say ‘What’s wrong with this picture?’

(rhetorical)

5 words yanking me from my fugue

to discover myself pretzeled around the machine

in a position so unnatural it had become natural

to a life lived more and more in a VL that had become my RL

there was a vastness to the generative affective experiences

it felt unstoppable

on par with the most exhilarating love affairs

continual platform jumping

(don’t mind the gaps)

with unseen but deeply imagined companions

haunting me from nautical twilight to nautical twilight

netmonster, 2005

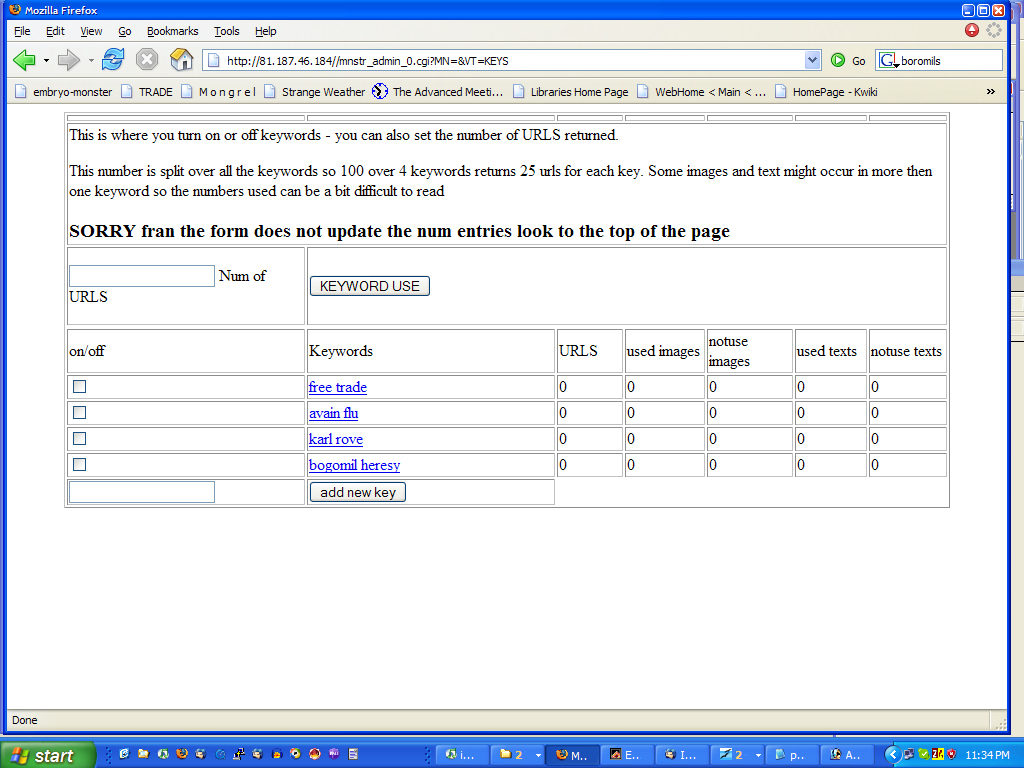

The only platform that came close to the seductiveness of Lambda was Netmonster, a network visualisation engine built by artist coder tinkerer Harwood (aka Graham Harwood). I was fascinated by the code and what it could do. And I adored the constant communication with my bruvv, the one who calls me ‘witch sister’. We hung around on the server, chatting white text on black screen. I made him a self-executing poem in Perl, my one and only attempt to learn some rudiments of that language. Netmonster could be a machine for collaborative writing, for prophesy, a tool for poking around in the machinations of power and capital. I imagined its transformative potential on a magical level, casting silver spanners into the bellyworks of the Beast. As a user I became tangled in search strings questing for the grail of understanding. Without knowing what I was asking, I pushed Harwood to push the code, Perl, to do things it wasn’t designed to do. The machine groaned under the weight of requests, and eventually its interactive functionality was turned off (brutal!), leaving just a beautiful hyperlayered carapace online. The emptiness I felt when the living essence of the project was no longer was comparable to the hole of grief when a lover says it’s over. The spirit of Netmonster had left forever. I was alone again.

clever little tailor, 2017

There’s a few of us chatting around a table in Clever Little Tailor, an affordable bar if you stop after one drink. Around the table S2 (artist/student, early 20s), A (poet/singer/student maybe just grazing 25), and a couple of ancient cyberwitches. We speak about imbuing inanimate objects, a child’s wooden horse, a Persian rug, with magical powers, to speak, to fly. The human tendency to want to create life in things, including things and wings of internet, and this predisposition in turn enlivens and expands us. The topic turns to matters of the heart, and native/natal platforms. Those communicative modes that either we were born into or grew into, the sticky tongue finger techs that we associate with our netted emotional and social lives. We talked about coding and not coding, about the need to live online, and the impulse to desert it. Instant Messaging is for S2 what Internet Relay Chat was for us. We spell out the spell of Command Line Interface in a condensed version of how we uploaded ourselves to the song of the modem, waiting up all night to be able to play, existing betwixt and between multiple time zones. We struggle to find the right words (because the material of this stuff is made of words but is so not about words really) to evoke the deliciousness of what was a relatively uncolonised uncommodified unregulated ineffable space. Even if we hexen rarely use the word ourselves, the neologism (and who could forget Neo!) cyberspace, continues to signify the consensual hallucination of jacking in to the zone. Maybe now it’s more mall than sprawl for us who experienced something more unbounded, but for the next gens the intensities, the desires are equivalent.

17.10.17

forever doll

becoming witch

she opens her mouth

and swallows the world

she opens her mouth

and swallows your word

dissolving like spun sugar

laced with saffron threads

hexe hexe hexe

tiva! tiva! tiva!

naughty naughty naughty

all for naught

and nought for one

zero and one

zeno and won

one on one on one

on and on and on . . .

Thank you to old and new friends whose ideas have nourished this text: Virginia Barratt, Alison Coppe, Linda Dement, Teri Hoskin, Jon Marshall, Stuart Maxted, John Tonkin. Big thanks to (bruvv) Graham Harwood for inviting me to play and live inside Netmonster in 2005.

Francesca da Rimini (aka doll yoko, GashGirl, liquid_nation, Fury) is an interdisciplinary artist, poet and essayist. She revels in collaborative projects, joining companions in generating slow art, strange beats and new personae. As co-founder of cyberfeminist group VNS Matrix she contributed to international critiques of gender and technology. The award-winning dollspace deployed the ghost girl doll yoko to lure web wanderers into a pond of dead girls. As GashGirl/Puppet Mistress, she explored the uploaded erotic imagination of strangers at LambdaMOO. More recent performances , collaborations and installations including delighted by the spectacle, hexecutable, songs for skinwalking the drone, hexing the alien, and lips becoming beaks have combined rule-driven poetry, fugue states, spells and prophesies as hexes against Capital.

“Certain subjects compel me – alchemy, folklore/folk law, emancipatory social experiments, the nature of cognition, and states of ‘madness’ and ecstasy. I approach art-making as a hexing, a spell, a witch’s ladder to another realm. To paraphrase anarchist anthropologist David Graeber, a revolutionary act is to behave as if one were free.” da Rimini

“Hello, I’m Riz Lateef. Tonight our top story: Instagram travel-star Amber Hinton is missing in Indonesia. Initial reports suggest she has been kidnapped by an ISIS faction operating in the region. We’ll have more on that after the headlines.”

In 2014 Amber Hinton left a lucrative job in finance to follow her ‘dream’ of travelling the world. Like many young women she recognised the potential inherent in her looks; she had an ability to tap into veins of social media, and grasped the appeal for people to ‘follow’ in her footsteps. Educated, professional and dedicated she began by surveying Twitter and Instagram; filtering by hashtags she categorised countries by cultural capital (aka likes, retweets, comments) and then cross referenced with existing coverage. Logic followed that if Thailand was hot right now it might not be hot in a year’s time. Novelty and newness would be essential to getting a foothold in the market.

After months of post-work spread-sheeting, Amber was ready. At a brunch with friends she introduced a mood-board and sales-pitched her new life. I say mood-board, but really I mean a highly aestheticised business strategy. She’d categorised hundreds of travel lifestyle pics and identified core principles of success. With Google Analytics she’d examined the lifespan of a hashtag. She’d reviewed where successful Instagram travellers had been, which countries were oversaturated and which were primed to explode. She’d mapped a route, ensuring a balance between city, beach and country, simultaneously factoring in cost efficiency. She’d prototyped a website and employed a graphic designer to mock up a look and feel for her personal ‘brand identity’. She’d run financial predictions, how long her start-up capital would last, how she expected to turn a profit through funding websites, travel blogging, and eventually as an advertising service for hotels and travel companies.

It was, in short, a stunning piece of work. If Amber had been inclined towards the monastic life of a PhD researcher, she could have turned it into four years paid writing, then subsequently taught her findings at Oxbridge without ever leaving the UK.

With her friends’ enthusiasm and her parents’ consent Amber left for Italy. Between 2014 and 2017 she travelled across the world, first moving in small steps, from Italy to Slovenia, to Bulgaria and Turkey. From Turkey she jumped around the Middle East and North Africa, avoiding conflict zones and skipping countries whose religious codes might frown upon her displayed body. Everywhere she went she befriended new contacts to utilise, chic twenty-somethings who’d invite her to their parents’ villas, rich bankers who’d get her into rooftop parties. Courting the cultural elite was vital; she didn’t have the financial reserves to fund a lavish lifestyle, but she could enter those worlds and achieve an image of effortless glamour.

By the time she reached the Moroccan coast she’d amassed over 75K followers. Enough to be on the radar of international PR girls. Invitations started flying in: five star luxury hotels and exotic adventures. Whilst sipping alcohol-free cocktails and bronzing her skin, she strategised her next move.

She flew to Malta, then across the Atlantic, island-hoping round the Caribbean. In America she visited boutique ranches and hunted down bohemian culture. Down to Mexico, then South America, a perfect blend of high class living and poverty porn. From South America she crossed the Pacific, stopping in at Hawaii on the way, then modern China and finally, in early 2017, Indonesia.

The world first knew something had gone wrong for Ms Hinton was when she posted a unusual message on Twitter. For three days she’d been five star eco-glamping in the rain-forested hills of Lombok, swimming in waterfalls, taking selfies with monkeys and then suddenly:

@amber_abroad

I heard a gun shot! What do I do! HELP HELP HELP

Minutes later a second tweet followed:

@amber_abroad

They said my name, tell me parents I love them

Within minutes a storm of activity was echoing around the Twitter-sphere and #saveamber was the number one trending topic on social media. Facebook campaigns began and Indonesian public officials were receiving flak from latte drinking yuppies in North London. By the second day the Foreign Office had publicly announced that British tourists in Indonesia were advised to leave the country immediately. Typically slow to respond, but then absolutely committed, ISIS announced that Ms Hinton’s abduction had been orchestrated by them, despite it obviously being carried out by a unassociated cell with little to no connection with the upper echelons. For three consecutive days BBC Breakfast News dedicated a half hour to the unfolding crisis; they even flew Naga Munchetty out to Bali to goad tourists into overreactions.

Five days of media fixation were followed by a week of not giving a damn; then out of the blue something very odd began to happen. Instagram accounts operating out of the Indonesian and Philippine ISIS territories started taking on a much more aesthetically sensitive tone. Poorly photoshopped images were replaced with a wave of creative shots. Against verdant jungle foliage, handsome young fighters were pictured topless, sweat glistening on their ripped pecks, rifles casually held over their shoulders. Puppies were photographed wrapped in ISIS flags. Trope travel images, ‘everyone jumping on the beach together’ and ‘girl leading boy’, were bastardised into calls to martyrdom.

At first Amber’s family was relieved; their daughter was alive and communicating with the world. Security services reassured them that eventually she would reveal her position, then they’d be able to plan her rescue. Weeks developed into months and still it seemed Amber was so tightly under the thumb of her captors that she couldn’t encode a message. All they could do was watch her PR strategy unfold.