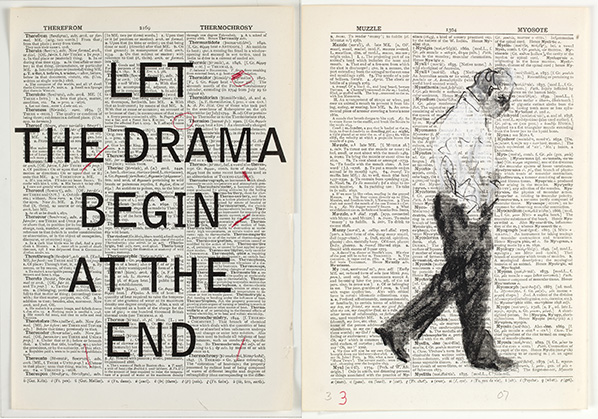

The Delfina Foundation selected Jean-Paul Kelly to undertake a residency in winter 2015. During his residency, Kelly regularly attended the City of London Magistrate’s court in Central London as a visitor. For eight weeks, he observed the routine events and procedures that took place in the courtroom. The UK’s Criminal Justice Act prohibits any form of documentation within the courtroom, whether it be a sketch or a recording, and only allows illustrators to take notes, most likely in the quick and loose form of stenography.

The absence and overall restriction of documentation within a courtroom (and beyond) leads to the fairly obvious skewing of narrative events. Kelly, who works with found photographs, videos and sounds originating from documentaries, photojournalism and online media streams, realised that the particular restriction was advantageous to the concept and the production of his new work, That Ends That Matter. For him, lack of evidence or documentation of a specific event elucidates a direct relationship between physical materiality and subjective perception of each individual.

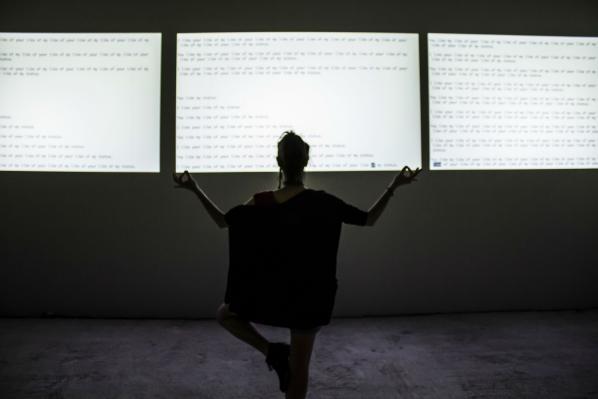

Such situations, in which evidence is lacking, fabricate image representations based on a very unreliable form of intangible reflection and recollection as both shared and personal memories. In our day and age, information is as effortlessly accessible as the Evening Standard on the Underground. However, within the courtroom, a place of supposed honesty and acknowledged transparency, the lack of documentation is paradoxical and challenges the sovereignty of such proceedings. That Ends That Matter is an eight-minute, three-channel video acting as a subjective reproduction of the events Kelly witnessed at court. One video re-enacts the court proceedings, another shows a constant photographic image stream as a retelling of the events and the remaining video acts as a visual soundtrack animation made out of geometric shapes.

Initially walking underground into Delfina’s bunker exhibition space, the viewer is confronted by the loud noise coming from the visual animation. To the left of the space, two screens are paired together – the image stream with the animation – and to the right of the space, the re-enactment stands alone. Encountering three screens, viewers may feel bewildered as to how to view the work, however, after a bit of floating, it becomes quite apparent that viewing order doesn’t really matter as each visitor finds their own. Some focus solely on the paired screens, others on the lone screen, and some sit against the wall and view the two screens (image stream and re-enactment) of the two spaces from the side together.

The re-enactment screen video begins, and a soothing female voice sets the tone for the three-channel video:

‘Excuse me, are you appearing before us today? No? Alright, so you’re here as an observer then? Okay, thank you. Welcome… Now we’re going to switch on some noise so we can discuss the matters properly.’

White noise immediately becomes a means of blocking transparent communication, in turn emphasizing the notion of skewing memory and representation of factual information. The re-enactment is played around a table, whereby the actors appear to be waiting around, lingering and passing the time. Although the scene is filled with white noise, none of the participants are talking to each other and there is a particularly eerie focus on an old man who keeps caressing the table with his finger – he soon looks up at us. The environment itself is immersive; the longer the viewer stays with them and observes, the more explicitly the viewer’s presence is felt by the actors. Presence is noticed and through direct and uncomfortable staring at the viewer, it is implied that the viewer’s observation is not wanted. The viewer is thus inclined to move to the left space and look at the other two screens.

Kelly uses a series of motifs and shapes interacting with the tactility of the artist’s finger or palm in order to establish image representation. When the visual animation screen shows a circle and emits noise, the image-stream presents a finger hiding a specific aspect of the photograph. When it is a square or a rectangle, it is usually a palm that hides a part of the photograph. Tactility in an immovable image stream represents an abstraction towards the idea of transparency. The artist’s hands touch, caress, hide, rub, caress and thus at times become overtly sexual when corresponded with homoerotic images – the hole becomes a motif frequently expended. The motifs of tactility cover people’s faces, acts of violence found in protests, and various scenes of despair. Here, tactility not only acts as a way of forming a temporal moment of surrealism, but also as a method by which one can learn how to connect to the images one sees, much like children touching things for the first time. The white noise itself, from being disturbing becomes soothing and harmonious with all three screens.

Smoke acts as another motif in images the viewer is shown. In a photograph where protesters are suffocated by teargas, the solution to the pain is pouring milk over your face, another act of blindness. Smoke becomes recurrent, and in the final frames of both the image-stream screen and the re-enactment screen, smoke presents itself with vigour. Smoke appears in the court of the re-enactment screen, and simultaneously, the sound stops altogether as the figures disappear in the haze.

That Ends That Matter’s representational strategy is based solely on memory and subjectivity as its response, much like the creation of human memories. To a certain degree, Kelly’s work embodies apophenia, a way of drawing connections and conclusions from sources that have no direct correlation other than their lasting perceptions – a spontaneous connection. It’s about communicating signs and non-objective matter, behaving in a way that strives to avoid both nostalgia and emotionlessness in order to question indexical notions of ethics in matters of transparency. Kelly may be asking, is abstraction fairer?

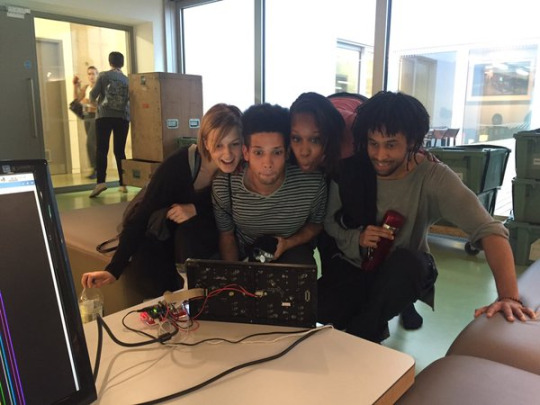

All images by Tim Bowditch, courtesy of Delfina Foundation.

At first glance networks and the practice of drawing would seem to be worlds apart. However, the diagram, originally a hand-drawn symbolic form, has long been employed by science as a means of visualising and explaining concepts. Perhaps the most important of these concepts is that of relationships visualised as circles and lines that represent nodes and links or effectively what is related. As such networks, that is groupings of relationships, have come to be visualised through the use of the same styles and iconography employed in diagrams. For artists to reclaim the diagram as a part of their own practice and thereby adopt the practice of visualising networks developed within science sees the practice of creating diagrams in a sense come full circle. Artists have time and time again drawn diagrams and networks that explore relationships. For example: Josef Beuys famously used blackboard diagrams as part of his teaching performances concerning art and politics; Stephen Willats has since the 1960s developed drawn diagrammatic works that explore his socially formed practice; Mark Lombardi drew societies’ networks of power relations throughout the 1990s; Torgeir Husevaag has since the late 1990s drawn diagrams of a number of networks within which he participated while Emma McNally draws diagrammatic networks “bringing different spaces into relation [such as] the virtual world, the networked world and the supposedly real world” (Hayward, 2014).

The work of Suzanne Treister resides within this category of artist’s drawing, and in this instance also painting, networks. With a background in painting Treister works across video, the internet, interactive technologies, photography, drawing and watercolour painting (Treister, n.d.). Her work employs “eccentric narratives and unconventional bodies of research to reveal structures that bind power, identity and knowledge” (ibid) within contemporary contexts. As a result of this process of revealing structures, essentially the relationships within the subject matter she addresses and the resulting networks they form, her practice has since the 1990s been closely allied with art that employs or explores technology. She has been repeatedly included in exhibitions and publications that link her work with networks, cybernetics, new media and most recently Post-Internet Art (Flanagan and Booth, 2002; Pickering, 2012; Larsen, 2014; Warde-Aldam, 2014).

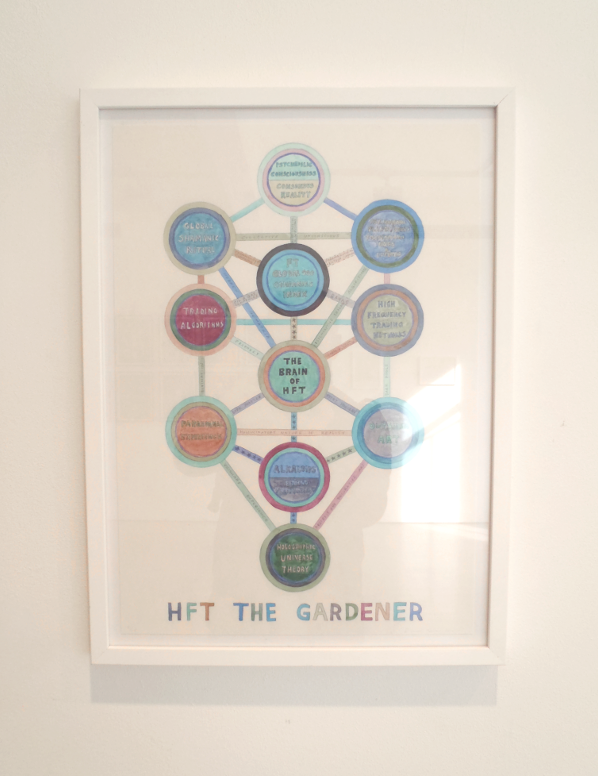

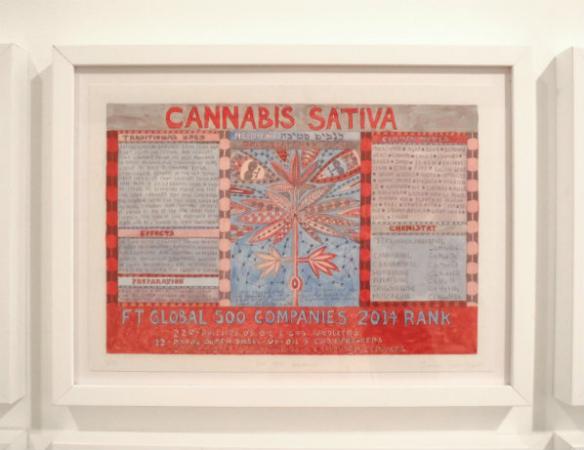

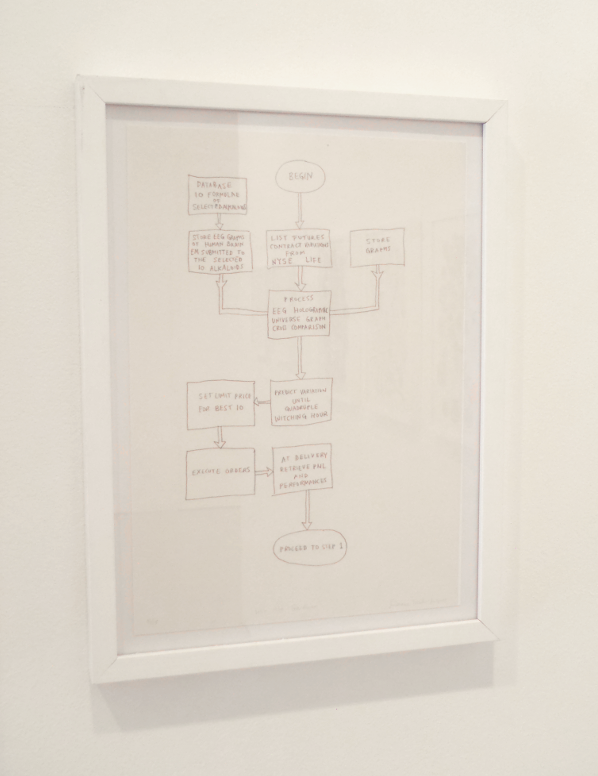

HFT the Gardener (2014-15), a recent solo exhibition by Treister at Annely Juda Fine Art in London, is a body of artworks consisting of drawings, paintings, photographs and digital prints supposedly created by a fictional character and a documentary video about the same character. The character, Hillel Fischer Traumberg, is an algorithmic high-frequency trader (HFT) within the London Stock Exchange. After an optically induced semi-hallucinogenic state, Traumberg experiments with psychoactive drugs in order to recreate and further the experience (Treister, 2015). Along the way Traumberg becomes fascinated with botany, experiments with the molecular formulae of drugs as trading algorithms, makes links between the numerological equivalents of plants’ botanical names and the FT Global 500 index, visually documenting all of his research and ultimately becoming an ‘outsider’ artist (ibid). In the process Traumberg transitions from an insider of one network, a trader within the stock exchange, to that of an outsider in another, the contemporary art world.

This juxtaposition of opposites is repeated throughout the exhibition. For example, the drawings and paintings of HFT the Gardener employ illustrations of networks containing nodes and links. These illustrate a number of different sets of relationships that are established by the artist. These include: that of the central character to his concepts, research and environment; the locations where drugs were taken; states of consciousness; the components of an algorithm; different companies within a sector and different aspects of the universe including life and art. Additionally a variety of diagrammatic forms are co-opted in the creation of the drawings and paintings including the Judaic Kabbalah Tree of Life, radial diagrams, flowcharts similar to those used in software design and reference is made to a number of other abstracted forms including star charts, snow crystals, fractals and paisley design. Through both form and subject matter the illustrations of networks and the diagrams gather together combinations of opposites. There is of course the use of what can be considered traditional media to illustrate new media forms, however among others there are also the opposites of painting and software, science and art, corporate and counter-culture, belief and fact, fiction and reality.

To coincide with the creation of the artwork a book of the same name has been published. In the foreword Erik Davis states that there is an “initial shock of Treister’s juxtaposition of esoterica and the financial sector” (2016). The same could be said of the numerous other juxtapositions that occur within HFT the Gardener. However, are Treister’s, or is it Traumberg’s, combinations really contrasts that shock? Treister does more than simply juxtapose opposites. The artist effectively synthesises them into a whole that is indicative of our networked era where individuals routinely select, cut, paste and combine combinations ad-hoc to suit a moment or context. HFT the Gardener is an artwork that could only be created in this era of networks and as such it cannot be considered shocking or out of context with the eclectic recombinatory society that surrounds it.

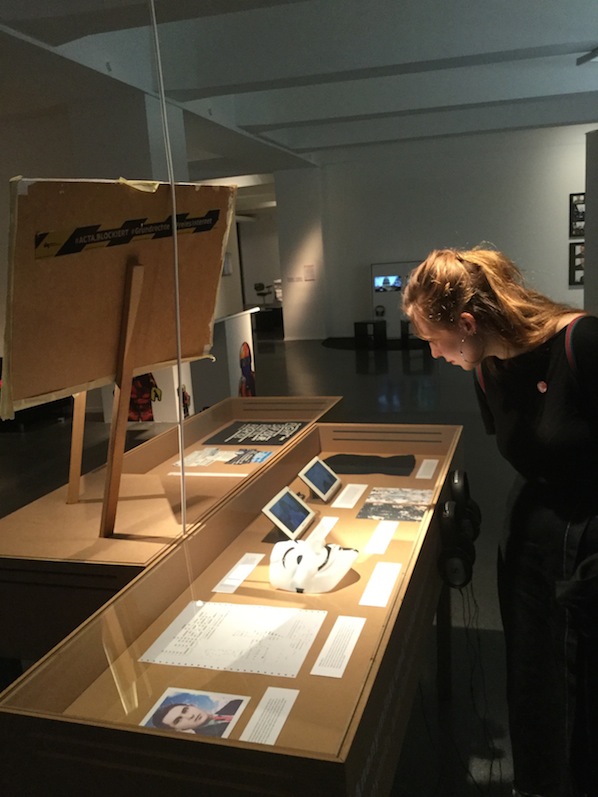

Not only are drawn diagrams and networks employed extensively throughout the exhibition in a number of ways but a network-like structure is also employed to arrange the artworks within the space of the gallery. Initially on entering the gallery space it seems as if artworks are arranged in no particular order. However it gradually becomes clear that this arrangement is purposefully obliging the visitor to enter into and move through the space as if it were a network; that is entering at any point and navigated in any order. While some series of artworks within HFT the Gardener, such as the Botanical prints, maintain an order to illustrate the ranking of companies employed in their creation, the majority of artworks are experienced out of the order they have been created and the documentary video about Traumberg, presumably from Treister’s perspective, is encountered at the midpoint of the exhibition. As such the artworks are presented as if they are interconnected nodes in a network.

As a result of the diagrams, illustrations of networks, juxtaposed combinations of subject matter and a network-like structure in arranging the artworks within the exhibition Treister successfully manages to make one last combination of opposites, that of non-linearity of experience and linearity of narrative. In doing so the visitor experiences the juxtapositions, combinations and resulting networks formed by Traumberg’s hallucinatory non-linear associations and yet manages to steadily interpret the detailed narrative carefully constructed by the artist. It is in this last combination where the strength of Treister’s exhibition lies as it not only reflects society at large but also suggests that art is and perhaps always has been, a non-linear networked experience that is only now coming into its own.

An exhibition catalogue of HFT The Gardener is available through ISSUU (https://issuu.com/annelyjuda/docs/treister_cat) and a fully illustrated book of the same name is available from Black Dog Publishing, London.

HFT The Gardener will continue to tour throughout 2017 at the following venues. Please see the artist’s website for exhibition updates.

22/10/2016 – 05/03/2017

Selected works from HFT The Gardener exhibited in The World Without Us

Hartware MedienKunstVerein (HMKV),

Dortmund, Germany.

07/01/2017 – 18/02/2017

HFT The Gardener diagrams exhibited in Underlying system is not known

Western Exhibitions, Chicago, USA.

03/02/2017 – 05/03/2017

Selected works from HFT The Gardener exhibited in Alien Ecologies

Transmediale 2017

Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germany.

Featured image: Image from When Drones Fall From the Sky, by Craig Whitlock, Washington Post. [link]

At 0213 ZULU on the 2 March 2013, a Predator drone, tail number 04-3133, impacted the ground 7 nautical miles southwest of Kandahar Air Base, Afghanistan, and was destroyed with a loss valued at $4,688,557.[1]

On the 27th March 2007, a crashed spy plane was discovered by Yemeni military officials in the southern province of Hadramaut, along the country’s Arabian Sea coastline. The following day, Yemen’s state media identified the plane as being of Iranian origin, and that it was yet another example of an Iranian provocation at a time of high diplomatic tensions between the two countries. It was three years later, upon Wikileaks’ release of the so-called Cablegate archive, that a US Embassy cable revealed the “Iranian spy plane” was in fact a “Scan Eagle” drone. The drone was remotely piloted from the US Navy’s USS Ashland which was patrolling the Arabian Sea as part of an international counterterror task force. The United States Military was not “officially” conducting military operations in Yemeni territory at the time, and had not sought permission to conduct operations in the country’s airspace.

The discovery of the crashed drone could have posed a difficult political problem for the US to solve. However, in the cable, the official makes it clear that Yemen’s President Saleh had been keen to reach an agreeable deal with the Americans and apportion blame on a convenient third party — Iran. The cable states:

“He could have taken the opportunity to score political points by appearing tough in public against the United States, but chose instead to blame Iran. No doubt focused on the unrest in Saada and our support for the transfer of excess armored personnel carriers from neighboring countries (reftel), Saleh decided he would benefit more from painting Iran as the bad guy in this case.” [2]

By 2007, aside from occasional reporting in the media and among some activist circles, there was little public awareness of the US drone program. In fact, the program was not officially acknowledged on-the-record by a US government official until 2012. This official was John O. Brennan, then Counterterror Advisor to Barack Obama, and the momentous occasion was a speech at Washington DC’s Wilson Centre—a “key non-partisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue”.[3] Brennan states:

“So let me say it as simply as I can. Yes, in full accordance with the law—and in order to prevent terrorist attacks on the United States and to save American lives—the United States Government conducts targeted strikes against specific al-Qa’ida terrorists, sometimes using remotely piloted aircraft, often referred to publicly as drones.”[4]

While the use of unmanned aircraft in warfare goes back to the early 20th Century[5], the distinctive image of the drone has come to characterise the ambiguous geopolitics of The Global War on Terror. Their hubristic names—Reapers, Predators — evoke visions of carnivorous animals carefully and selectively stalking their prey. With their stealth and capacity to observe targets for hours on end before striking, the drone selectively adopts the tactics of the insurgency: it is an emergent weapon directed onto an emergent threat. Drones, like their intended targets, are not necessarily contained by borderlines, or to territories on which the US has declared war. They are in a suspended state of exception, and are decried both as being outright illegal by experts in international law, and simultaneously, as Brennan contests, strictly adherent to the doctrine of Just War.

In Brennan’s Wilson Centre speech, he draws on medical analogies to justify the “wisdom” of drone warfare, emphasising its “surgical precision—the ability, with laser-like focus, to eliminate the cancerous tumor called an al-Qa’ida terrorist while limiting damage to the tissue around it—that makes this counterterrorism tool so essential.”[6] But are drones as precise as Brennan’s rhetoric implies? Drones are often said to be heard, and not seen—their whirring noise inspiring local derisive colloquialisms[7]. But it is especially in the drone crash that the drone can be seen, and what’s more, subjected to inspection. It alerts us to a vital consideration: the failure of so-called precision military technology.

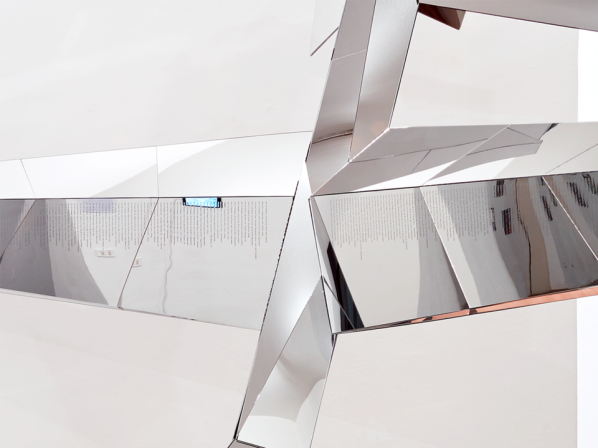

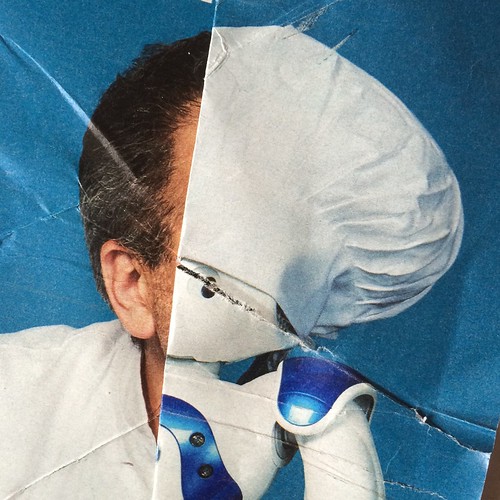

In IOCOSE‘s Drone Memorial, our attention is drawn to the fact that these complex systems are precarious, that the drone is indeed a fallible technology. The memorial, a sculpture of a fallen Predator drone driven into a copper plinth like a blade, subverts the surgical metaphor proposed by John O. Brennan. The drone’s mirrored surfaces create a fractured, tesselated reflection of its surroundings, its form almost vanishing in a specular camouflage. Inscribed on its wings are the memorial’s “fallen comrades”, the hundreds of other drones that have crashed, listed by location and date. This list can only be considered a selection, however, such is the secrecy around the use of drones in the War on Terror. As such, it should also be considered a monument to the journalists who manage to report on the discrete events of drone warfare in incredibly challenging circumstances.

A GPS beacon embedded in Drone Memorial broadcasts the location of the sculpture on the project website, hinting to us that this seemingly trivial technology in our smartphones has more nefarious uses. Global Positioning Systems have their roots in Cold War ballistics research, specifically in a program by DARPA codenamed TRANSIT, developed to direct the US Navy submarine missiles to “within tens of meters of a target”[8]. Today, GPS is one of many components in the assemblage of technologies used in the drone, and a key enabler of its apparent “precision”. Nevertheless, GPS can of course fail—it can be “jammed” inadvertently, or indeed tactically manipulated by malicious third parties. When the satellite link is lost with a drone, the aircraft goes into a holding pattern, flying autonomously until control is regained. In the Washington Post‘s story “When Drones Fall From the Sky”, they note that in order to keep its weight at a minimum there is little redundancy built into the drone’s on-board systems. Without backup power supplies, transponders and GPS links fail, and in several cases “drones simply disappeared and were never found.”[9]

IOCOSE’s positioning of the memorial as existing in a hypothetical, post-war scenario poses some interesting questions, but this temporal dissociation is perhaps unnecessary, for this is an issue very much of the present. It is certainly a topic more than worthy of critical investigation—the spectacle and the political consequences of failure have largely been left out of typical artistic engagement with drone warfare. In their press release accompanying the work[10], the artists suggest that the sculpture has an absurd quality. To me, it is not absurd as much as it works as an apt memorial to the violence of failure. In reading the long list of drone crash locations, the viewer might begin to probe the question of what information should be open to public scrutiny. IOCOSE pose the following question to us: “Does a drone crash count as a technological failure, or as a casualty?” This question would appear to have a clear answer: we must see the drone crash as a technological failure, so as not to make a false equivalence with the real casualties of drone warfare—the civilians who are subjected to it, the very same people who might also counter Brennan’s claims that the drone is a surgical, precise weapon of war.

Drone Memorial is the third work in a series titled In Times of Peace. This most recent work is the most astute in challenging the legally and ethically disruptive paradigm of drone warfare: it pierces the reflective rhetoric of US defense officials, and directs our attention to the high-stakes violence of its technological failure. The memorial, of course, ordinarily comes after the historical moment. This ‘moment’ is very much still unfolding 15 years later, and as the Trump administration takes form, it seems that the way in which drones will be deployed in the future is an ‘unknown unknown’. Thus, Drone Memorial is a temporal snapshot, an aesthetic pause on an ongoing, mutable war that seems to operate on a parallel continuum, only occasionally visible. More drones will continue to fail, as the drone war inevitably continues. These failures present a moment for critical analysis, a flash of visibility that should be seized upon.

Featured image: Pandora’s Dropbox by Matt Bower

The Disruption Network Lab (DNL) has been presenting in Berlin some of the finest platforms for the discussion of art, hacktivism and disruption, presenting academic debates on not-so-conventional forms of thought. In their event IGNORANCE: The Power of Non-Knowledge, the second in the series Art and Evidence, various scientists and researchers discussed ignorance, not merely as a subaltern issue but as a central tool in knowledge production.

In previous events, DNL debated how ignorance is deployed as a mechanism of truth and power negotiation, mainly through the omission of the known by the means of secrecy, obfuscation and military classification. There are many forms of understanding ignorance, and this program intended to elucidate the potentialities and pitfalls within the concept. According to DNL, the first step towards approaching ignorance is to recognise it and become aware of it. As co-curator of DNL Daniela Silvestrin said (despite the paradox) that it is necessary to render the “unknown unknown into a known unknown.” The field of ignorance studies investigates the spread of ignorance, what kind of forms it takes depending on the context, how science “converts” it into probabilistic calculations of risk, and even how it can be used to push certain political, economical or religious agendas.

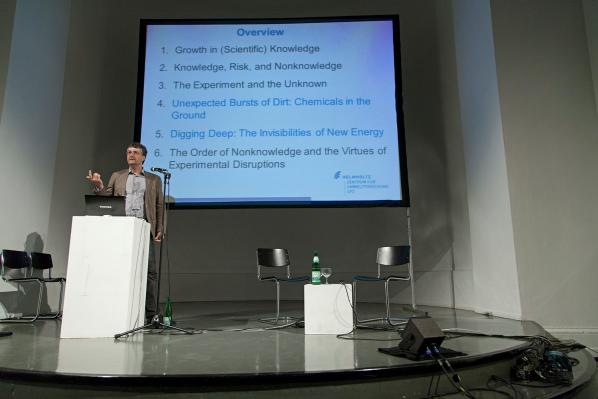

In the opening keynote, Matthias Gross, a sociologist and science studies scholar who has written extensively on ignorance studies, co-editing with Linsey McGoey the “Handbook of Ignorance Studies,” starts by stating that “new knowledge always creates new ignorance” and that throughout history humans have been in constant relation – acceptance, denial, resignation – with the unknown. Gross has covered how ignorance operates in different scientific milieus, namely, how risk is widely used in natural sciences as an attempt to project an idea of the future, as demonstrated in weather forecasting, but also how not knowing operates in everyday life; through secrets, the spread of false knowledge, feigning ignorance, or even through actively not wanting to know.

Gross presented a compelling body of research, exposing numerous examples in which ignorance serves the purpose as a tool to acknowledge what we don’t know in science (important in fields such as Epidemiology) or how positions of power use ignorance to manipulate public opinion within our social structures. However, the debate felt somehow stranded in an optimistic loop, where ignorance was seen mostly as a catalyst to search for further knowledge. Yet, I believe, while duelling with the binary knowledge vs ignorance, one should never forget to tackle the universalistic shape that ‘knowledge’ tends to adopt. In the end, the discussion felt insufficient, failing to examine knowledge/ ignorance from a non-hegemonic perspective when it would have been interesting to borrow criticism from postcolonial or feminist thought.

The first panel, moderated by Teresa Dillon, was deemed to shake the consensus in the room by joining the moralistic perspectives in science, the forbidden and undesired, the paranormal and the apocryphal together. Sociologist Joanna Kempner presented astonishing research focused on ‘negative knowledge,’ described as taboo, dangerous or threatening to the status quo. In an attempt to demystify the neutrality of knowledge production in sciences, Kempner interviewed various scientists to discover forbidden areas in their fields. The outcome of this research revealed that due to a fear of loss of funding and/ or sullying their reputation, scientists restrain themselves from researching illegitimate topics. For example, in Psychology one is expected not to study extra-sensory/ paranormal senses as these studies are usually associated to parasciences, a term that is in itself revealing of the hierarchies of knowledge. Kempner also exemplified how knowledge production is pressured by political interests and recalled the research-bans during the G.W.Bush government that cut funds to research related to sex and drugs under the assumption that remaining ignorant about any possible positive aspects (of recreational drug consumption) guarantees the maintenance of conservative moral values.

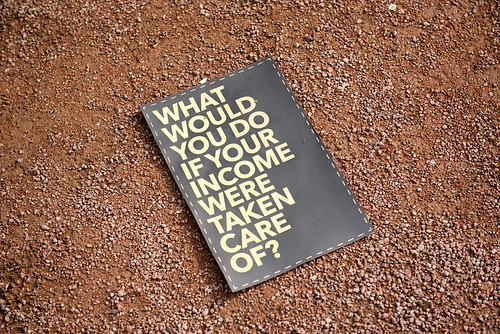

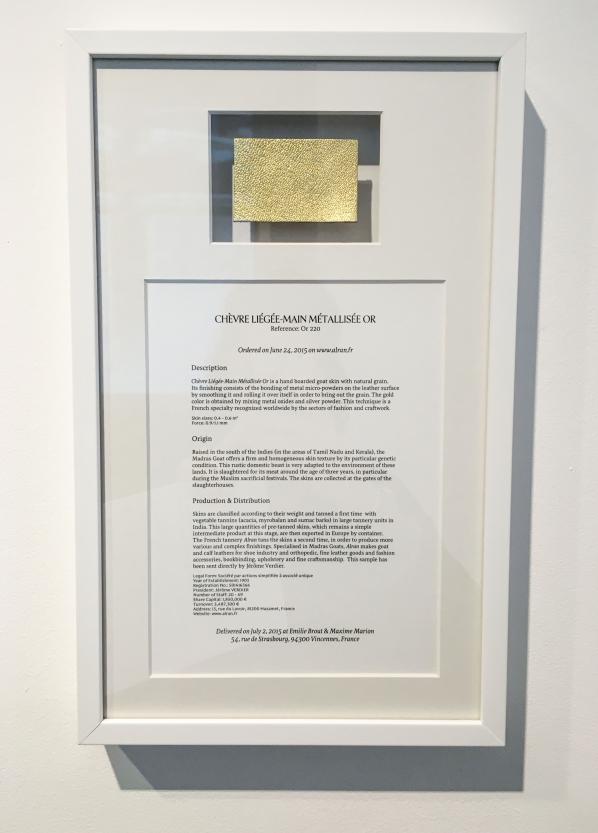

On the maintenance of moral values, the philosopher Jan Wieland presented an interesting experiment: “What would you do if you wouldn’t know? And what would you do if you’d know?” Giving the example of a social experiment by Fashion Revolution, a movement that calls for “greater transparency in the fashion industry”, Wieland examined consumers’ choices as they acknowledged the conditions in which clothing is actually produced. The project invokes a sentimental story with an excerpt from the daily life of a young girl living in Dhaka, Bangladesh, who works in a garment factory. Coming to terms with the girl’s story, the reactions differed — from not buying and empathically connecting with her situation to total indifference and still buying. Wieland attempts to analytically evaluate their intentions, good or bad, and how ignorance affects choices, stating that some of us might willfully remain ignorant (willful ignorance) as a way to better cope with our habits of consumption. However, I find it difficult to extrapolate these findings to a moralistic and individualistic criticism of people’s consumerist choices, since we know there is a structure that keeps consumers far from well-informed. A good example of how economy capitalises on ignorance, we know that the international division of labour is intentionally built to alienate the consumers from the “dirty” phases of production.

Jamie Allen, artist and researcher, also analyses at the economy of non-knowledge that is in the genesis of apocryphal technologies. “Do pedestrian’s crossroads’ buttons actually work?” We have all thought about this, yet has it stopped us from pressing the buttons? As long as we do not know whether a certain technology actually works, it “works”. Such an economy is boosted by acknowledging that some things remain as common ignorance. If we are not sure whether a lie detector works or not, then it can be used to incriminate — amidst ignorance, it shall produce the truth.

Informative and somewhat frightening, “Merchants of Doubt”, directed by Robert Kenner (2014), reveals how bendable ‘truth’ is in the interests of big corporations. The documentary investigates how the tobacco industry spread false information among firefighters, leading the world to believe that the domestic fires caused by cigarettes were the fault of the furniture rather than the cigarettes. This is where it goes from uncannily funny to scary. While interviewing scientists, whistleblowers and activists, the film unveils the dreadful story of corporate campaigns designed to unleash confusion and scientific scepticism among the masses, putting the life and security of millions at stake. This scepticism is not passive, thus it turns into a cynical endeavour. As corporations claim that there is no consensus surrounding issues such as global warming, conferences and books are forged to sustain their statement, while scientists who defend the existence of greenhouse gases are accused of ceding to their political biases in order to get funding for their research. What about facts? They seem to become irrelevant in the face of expensive lies.

Watch Merchants of Doubt’s trailer here.

Karen Douglas, a social psychologist, presented an empirical study of conspiracy theories whilst trying to trace a particular psychological profile of those more prone to elaborate and believe in them. Douglas used widely known conspiracy theories as examples, such as the infamous car crash that killed Princess Diana (which became a true “Schrödinger’s cat” case, instigated by the media-produced hyperreality in which Diana was both alive and dead — along with Elvis Presley) and the theory that 9/11 was orchestrated by the United States government to instigate and justify the “war on terror”. Douglas believes we are naturally hardwired to believe in conspiracy theories and sees them as a way to cope with things we are unable to answer. A socio-analytical view on conspiracy theories also seems to fail the complexity of forces that make us consider why certain theories are conspiracies and other perspectives are just theories. The issue with Douglas’ approach lies within its socio-psychological analysis, which tries to find a pathological pattern in people who believe in conspiracy theories, such as describing these people as being intentionally biased, or stating that those who tend to perceive patterns in things or believe in more than one conspiracy theory all show the “symptoms” of a conspiracy theorist. Yet, as pointed out by a member of the audience, this approach seems to lack a sensibility to the entire concept of “conspiracy theory” as a political tool to dismiss and undermine other narratives, such as narratives from an undesired other (e.g. how Russia’s government agenda is seen by the USA). Nevertheless, it is interesting to understand how these bodies of “disbelief”, should you wish to call them conspiracy theories or not, have a huge impact on our lives and inevitably our deaths (e.g. global warming, vaccination). As with apocryphal technologies, certain forms of unknown seem to crystallise as forms of knowledge – we know that we do not know and that is the way it is.

The closing panel, moderated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, has overseen our entanglement on social media and its algorithms, promising to be oracles of truth while their complex structures grow beyond our understanding. Ippolita, a group of activists and writers, warned how social media promotes emotional pornography, where our feelings are exploited by click baits in exchange for our personal data. By establishing clear metrics of interaction, like the number of likes and comments, social media creates an addictive game of forged interactivity, while we are scrutinised by biometric evaluation resultant from the same data we produce. Also analysing the manipulation of data and its weight in political agendas, Hannah Parkison, a journalist focused on digital culture, analysed Trump’s run for presidency propaganda in digital media. By using mostly social networks, such as Facebook and Twitter, Trump has kept control of his narrative without entering into risky interviews broadcast on TV. This is an effective way to get away with lies, regardless of the constant warnings from fact checkers – according to Politict 78% of what Trump said on the run for the election is not factually true. These lies spread across the internet, rendering their own truth.

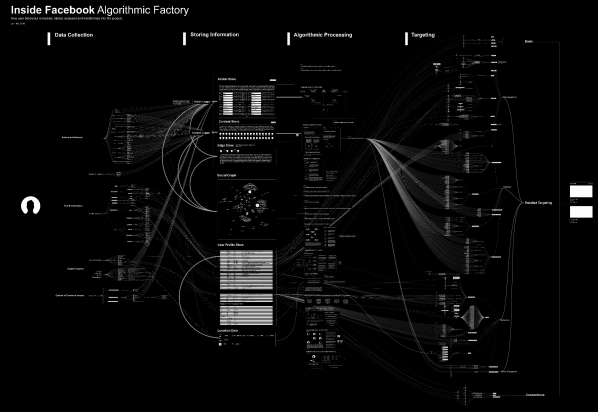

Vladan Joler, chair of New Media Department at the University of Novi Sad, presented his project in which he tries to map the tentacular structure of the Facebook algorithm, an expansive database incorporating individuals’ personal information that implies the fabrication of assumptions about potential consumers’ habits, wants and needs. Facebook was thus framed as an immaterial factory of information, the functioning of its assembly line still unknown, constantly mutating and growing. A speculative visual image of Facebook’s processes was rendered as Vladan tried to map something unknown; this mapping has similarities to the work of early cartographers. And much like early anthropological stances, the nodes of information produced have the potential to define thoughts and discussions about what we are and how we are supposed to behave. As Vladan ironically concluded, these are the tools used by the cybernet dominators – the digital monarchies that will accentuate asymmetries.

Ideas such as ‘knowledge’ find resistance and defiance from other epistemes that fall out from the western-centric productions of knowledge, such as the Amerindian ‘perspectivism’ defended by Viveiros de Castro or even the Alien phenomenologies (see Ian Bogost) that instigate the thought of non-anthropocentric ontologies. Bearing those in mind, I found that talking about the ‘dark’ side of knowledge is an invitation to dismantle and boycott its mechanisms of production, sustained in frail ideas of “truth”, “reality”, or “science”. In addition to the initial concept of ignorance, the conference provided a fertile ground for questioning the multiple ways in which humans deal with intangible phenomena, try to bypass obscurity and profit from that same obscurity. It provided insight on the relevance of knowledge to map and create reality, while bodies of power render webs of mystification of the tangible – corporations forging lies, politics of manipulation, cultural colonisation – reproducing ad nauseam epistemic violence.

The third edition of the Art and Evidence series from Disruption Network Lab, which took place on the 25th and 26th of November, wrapped up with the event TRUTH-TELLERS: The Impact of Speaking Out. TRUTH-TELLERS asks a question that could not be more crucial at the moment: “Can we trust the sources and can the sources trust us?” We have recently experienced a presidential battle between Clinton and Trump in which one of the most divisive topics were the thousands of emails sent to and from Hillary Clinton’s private email server while she was Secretary of State. A battle from which Trump left victorious despite having failed almost every fact-checking test. While Assange is forbidden to use the Internet for fear of him interfering with the presidential run in the USA, Chelsea Manning remains convicted, sentenced to 35 years of imprisonment due to her 2013 accusations of violating the Espionage Act. DNL gathered hacktivists, privacy advocates, investigative journalists, artists and researchers to “reflect on the consequences of leaking and whistleblowing from a political, cultural and technological perspective”. Unfortunately, due to a lack of funding, this could have been the very last DNL event. Let’s hope not, as these are vital, particularly in times of political despair.

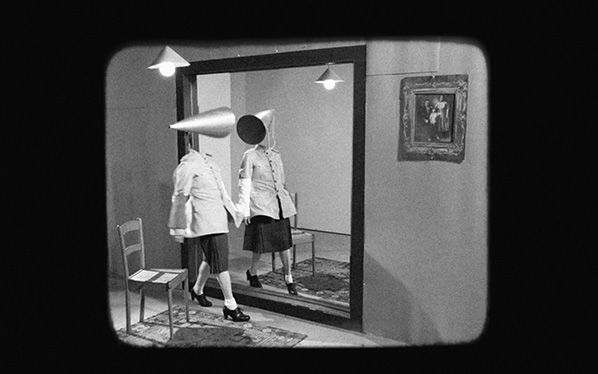

Feature image: Still from Dreams Rewired: original source Das Auge der Welt (Germany 1935); dir: C. Hartmann

Dreams Rewired / Mobilisierung der Träume – Trailer from Amour Fou on Vimeo.

The 2015 film Dreams Rewired, recently shown at the Watermans Digital Weekender in London on 12-13 November, will be screened again at Watermans on 3 December. Directed by Manu Luksch, Martin Reinhardt and Thomas Tode, the film has the tagline ‘Every age thinks it’s the modern age’. It looks back to the early 20th Century, to the development and implementation (first locally, then globally) of the telephone, the radio and television.

The makers of Dreams Rewired unearthed and arranged early film recordings and brought them into the 21st century context. This was done via a playful narrative written by Manu Luksch and Mukul Patel and read by Tilda Swinton. The tagline was well chosen; almost everything Swinton says would have been relevant at almost any point within the last century. Time periods, machineries and political movements are connected in clever and unexpected ways, meaning that Dreams Rewired, a durational video whose narrative follows a recognisable storytelling structure, makes numerous links between times, places and people, which branch off from the safety of its linear structure.

Dreams Rewired is something of a treasure trove, not only for the glimpses its found-footage building-blocks gives into a past era but also because of the inter-generational, inter-national, inter-thematic connections it makes. Frequently while watching the film I felt the urge to burrow into an investigation of one of the clips, stories or introduced contexts. To emulate this ‘tip of the iceberg’ effect, this review will pull words directly from the film, linking quotations to some of the themes which appear and reappear throughout.

“A new electric intimacy”

With new media come new practices of communication. One of the recurring themes described in Dreams Rewired is the coupling of intimacy and invasion of privacy introduced to society along with a new communication method. Just as a new invention is prototyped, its social implementation causes new prototypical behaviours – new ways of caring, new ways of injuring, new comings-together, new separations. Uncertainty is inherent to experimentation.

“The waves travel at the speed of light, defining what simultaneous means. Information can travel no faster.”

When something is newly possible it also newly achievable – new precedents are set and new avenues opened for exploration. There is a flurry of activity, a rapid diversification. For those looking to gain or retain power over others, this is a problem; diversity requires more effort to manage. Initial flurries of activity are curtailed by the introduction of rules, the setting of precedents.

This limitation sets new targets to meet, new challenges to overcome. The cycle starts again as those in power look for ways to consolidate it while those without look to gain what they can. This is a simplistic, but not inaccurate, description of the machinery of the capitalist world.

This cycle of diversification and restriction is always coupled with the establishment and transcendence of thresholds. Experimentation with a new technology reveals some of its limits. (Side note – of course, what is understood as a limit is defined by wider cultural contexts.) “Information can travel no faster” is a provocation to speed up.

“Geography is history”

New advances cause conceptual shifts. Early telephony and television shrunk the gap in time between a thought or plan and its activation. Understandings of time and geography changed, and it became possible to move into new spaces and in new ways at socially impressive speeds. New powers, in short, were available to those who knew how to access them, to those who understood the preceding context well.

“A model of the new human is put into circulation”

A network grows, its complexity and partner processes intensifying. The machinery of daily life is altered, and daily life is a testing ground. Social interactions change as the new set of behaviours required to work the new machinery collide with existing social norms and rituals. New jobs and new workplace structures appear and people previously without responsibility or power find themselves in contact with it (though they may not understand the possibilities at first). People are no longer the same beings as before. Cycles of experimentation and consolidation reach into the body.

“Someone will have to lift us up. But who will lift them up?”

The flurry of excitement surrounding a new invention is based on the idea that ‘our’ lives will be improved, that ‘we’ will be able to do, see, have more. There is a problem here. The words ‘we’ and ‘us’ are too abstract – they bracket whoever the speaker wants them to bracket and recapitulate the prejudices they have. Anyone who is not included as part of the ‘we’ simply does not exist. This is convenient for the ‘us’ – while ‘we’ rush excitedly towards a future in which we have more and better, what ‘they’ do is of little concern. The ‘us’ does not care – or even think much – about the ‘them’. The ‘us’ cannot understand why the ‘them’ has not joined the ‘us’. After all, the ‘us’ is at a new threshold – who would not want to reach the other side?

“Personal profiles, passwords, biometrics..fully documented. Every trace filed. Bigger data, better analytics. Opt out, and we lose our place in the world. So…we share the keys to our desire, our habits, to ourselves.”

To be part of the ‘us’ and the ‘we’ requires effort. To ‘opt in’ requires sacrifice. At the same time, ‘opting in’ is the easiest thing in the world when ‘opting out’ means facing a void. Advice on how to do well, how to achieve, how to be healthy is easy to come by, but there is little guidance for those who find themselves, or wish themselves, outside the mainframe. Losing one’s place in the world means losing access to that mainframe and the stability that comes with a highly legible structure. Today the legible structure is far-reaching and well established, to the extent that opting out is dealt with violently. The new models of human coming into circulation have trouble recognising the old. There is a mutual rejection.

“Government regulation stifles amateur culture – military and commercial interests occupy most of the spectrum … transmission becomes a privilege, not a right”

As I wrote earlier, the ‘us’ and ‘them’ structure is too simple. It would be more accurate to think of people as communicating on multiple frequencies. The machinery of society is complicated to say the least, and made more so by the mainframe, which amplifies transmissions at some frequencies while restricting others. In the early 20th Century, multiple obscure radio channels were repressed, responsibility placed with public backlash following rumours that amateur radio was responsible for the sinking of the Titanic. Side questions: where did the rumours come from? What were they based on? How was the public response measured?

“For the first time he hears himself as others do. A voice absolutely familiar but estranged…But her power also grows: by controlling his voice she controls her time”

There is a strange relationship between the controller and the controlled. For every CEO there is a team whose own agenda seeps into the workings of the company. Dislocated power and fragmented or unplaceable identity are some of the symptoms of a complex system undergoing change. When a system is so complex as to involve multiple timescales, spaces, materials and structures, it is impossible to predict the future.

—

Dreams Rewired is part of the Technology is Not Neutral Symposium

3 December 2016

Watermans, London

https://www.watermans.org.uk/events/technology-is-not-neutral-symposium/

Two years after his death, Harun Farocki continues to maintain an archetypal role in the world of the visual arts. Many mourned for the loss of a gifted artist who was as not just a filmmaker but a critic, activist and philosopher en masse. Farocki succeeded his German New Wave filmic predecessors as his work would seamlessly and at once command hilarity, disparagement and intellect. A project-retrospective collaboration of his work was undertaken, just two years after his death, with its first part at The Institut Valencià d’Art Modern (IVAM) named ‘What is at Stake’, and more recently the second-part titled ‘Empathy’at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies compiled of at least 8 works focusing on an analysis of labour within the framework of capitalist demands.

The title of the exhibition, ‘Empathy’ originates from Ancient Greek; ‘εμπάθεια’ is a compound of ‘έν’ and ‘πάθος’ meaning ‘moved by passion’. In German, empathy translates to ‘Einfühlung’ and was ironically exploited by Farocki in 2008 as the title for his text and reads:

‘A compound of Eindringen (to penetrate) and Mitfühlen (to sympathize). Somewhat forceful sympathy. It should be possible to empathize in such a way that is produces the effect of alienation.’

Taking into account Farocki’s liking of Brechtian ‘distanciation’, he formulated rather quickly that to ‘empathise’ means to project one’s own feelings, therefore infiltrating objective opinion. The notion of ‘empathy’ for Farocki was carefully tailored to a synthesis that gave him the patience to be simultaneaously attentive and austere towards his subjects’ predicaments. As paradoxical as it may seem, empathy and distance are nurtured companions. With Farocki’s interpretation of empathy in mind, I entered the dark bunker where the retrospective took place. A space usually leaking brightness from the glass roof was now transformed into an industrious zone of projections, obsolete TV sets and the mellifluous humming of those operative machines. Farocki’s filmic oeuvre overflowed from devices onto white surfaces, accentuating the techno-capitalistic condition of labour operating eradically for our Western communities.

As you enter, the video-installation of Workers Leaving the Factory in Eleven Decades (2006) dominates the center. Twelve TV monitors are laid out in a horizontal line, juxtaposing chronologically the moment where the worker leaves the factory in Farocki’s twelve chosen films – among them, Workers Leaving the Lumiére Factory in Lyon (1895), Deserto Rosso (1964) and Dancer in the Dark (2000). Here, the excerpts are used as a mnemonic tool as Farocki’s montage gravitates around the entrance of each factory. Each scene extrapolates the repetition of entering as a rhetorical techne, an emphatic mimesis of organising and preserving power through the image of the factory and its systems of subjugation. Yet, distance and empathy are circular and procedural.

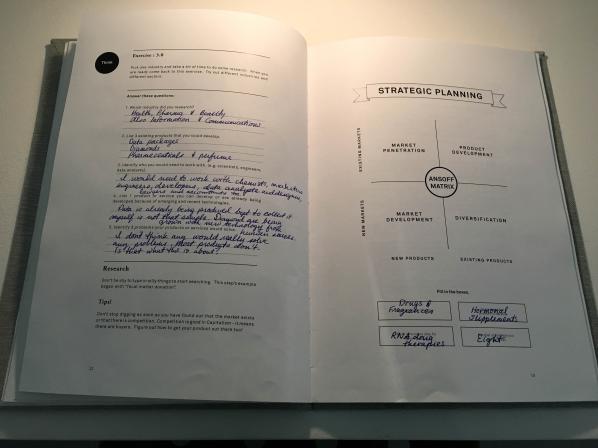

Curated to encourage a clockwise movement following the introductory piece, A New Product (2012) is being televised to the left. It commences during a mundane corporate board meeting for a consulting company violently regurgitating neoliberal logic. The goal of the meeting is to amplify competition and ascertain efficiency of their employees in the workplace by creation of a new product. Through the repetitive flipping of charts and reports, Farocki succeeds in capturing the vocabulary of rationalisation regarding their employees’ assets while unfolding the dynamics of the team and its public presentation. The narrative’s structure being static and unobtrusive, in conjunction with the ascetic use of the camera implies a degree of distancing from the subject. Still, the absence of Farocki’s own evaluation additionally contains the capability to bolster the viewer’s assessment of the situation thus achieving the artist’s desired equilibrium between empathy and distancing.

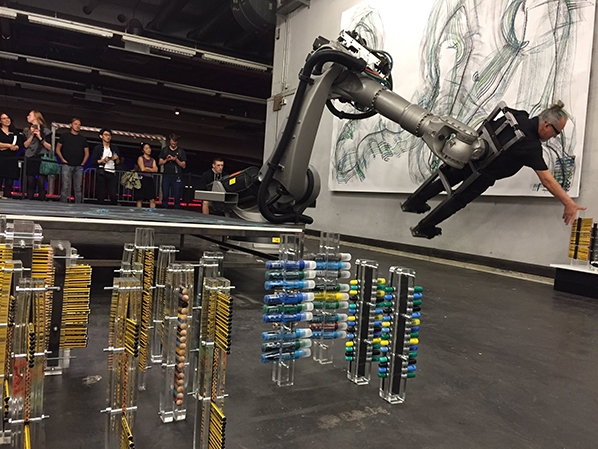

There existed a sense of rituality by which the projections were transmuted from a seemingly simple and observational nature, to one which was filled with the allegory of transparency and distance. Re-pouring (2010) was an ode to Tomas Scmidt’s Cycle for Water Buckets (or Bottles) from 1959. The original piece was a carefully choreographed mise-en-scene by which Scmidt poured one glass, a bottle of bucket of water into another. The act of pouring for Schmidt was one which indicated a simple and natural process of vaporisation with each pouring. Farocki had programmed machines to perform the artistic gesture for him, a re-pouring of the performative fluxus notion. A paradoxical act, since as human beings our navigational processes depend heavily on our cognitive ability, the mechanical hands were able to seamlessly perform the act of re-pouring. Farocki’s hyperrealism allows him to jump to a certain scale of futurity whilst also being rigorous of scrutinizing reality. The act of programming robots to perform a ritualistic and performative task goes undoubtebly implies distancing from the artistic practice of Fluxus. The Fluxus movement was predominantly a practice governed by experimental notions of performativity which were heavily conceptual. It therefore comes into stark contrast to the idea that such act could be thought by algorithm machines as notions of ‘thinking/feeling machines’ in contemporary society are rudimental and dreams of a future imagination. Farocki, able to perform the task himself such as with Indistinguishable Fire, does not. He steps out, physically distances himself from undertaking the task himself but maintains his empathy to former Fluxus activities but also expressing a empathy towards machines who today perform most human labour.

Amidst one of the spectacular accummulations of Farocki’s body of work, the apogee of the retrospective would be Labour in a Single Shot, shown for the first time in Spain. The project was initiated in 2011 by Harun Farocki and Antje Ehmann, co-curator of the retrospective. Located in an entirely different bunker, the work was compiled from a series of workshops whereby a fixed camera filmed paid, unpaid, material and immaterial labour from fifteen workshop locations. Projection screens are hanged in a room, most facing eachother whilst the noise of all labour taking place floods the space. Harmonious parallels are created as sequences from butcher shops and surgeries face eachother. The repetitive looping and sequencing of labour is used as a means of distancing and signifies non-judgmental watching as an active practice of iconic power. Our lasting impression is a call-girl sucking on a lollipop explaining how her artifice encourages clients into believing the gratification she provides is sincere. Here, we understand that just as she, through sex, retains empathy and distance in unison, Farocki’s empathy can thrive.

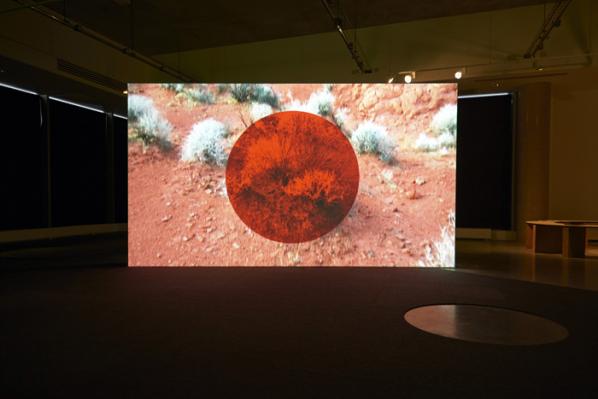

Featured image: The Refusal of Time, film still, courtesy William Kentridge, Marian Goodman Gallery, Goodman Gallery and Lia Rumma Gallery

There is a show of art by W K now in town. My friend, if you see but one show of art works this year or the next one or yet the next I beg of you see this one. The world of these works is both our world and not our world. The world of these works is thick and dense with rune and script and sign and light. And do you know the show is called THICK TIME and this seems as they say bang on for there is a sense in which the world and all that we are in it is here boiled down is made dense or thick. And it flows in front of us and we can see in what way and where from and where to it flows. Rune and script and sign and glyph and folk and things are drawn with ink or shown with torn or cut up scraps or light yes light much of it. And since light then dark too. Yes dark. This world flows yes and this world jumps and swells and shakes too.

And song and sound. There is song and there is sound of all kinds. There is a drum a big loud drum and a thing which marks time tick tock tick tock. There are sweet sounds and harsh sounds too. There is song. And there is change. Things change this way and that. This world will fill you with joy and at times it might make you sick at heart. It will make your head ache and pulse and spin. You might need to close your eyes. This world will speed your pulse and make you sweat. You start to dance when you see this world. You might smile. You might cry. You might have as they say a lump in your throat. W. K sees the world as we see it and knows our world as we know it and sees a world that we don’t see and we don’t know and shows it to us and now we think why did we not know this world it was there in front of us all that time.

Please note W K makes stuff with his hands. That is what he does and then he makes the stuff move. He makes things come and he makes things go and he makes things flow or stay still, he makes a world but he is not a God. He makes art. This is art. If you say to me what is art I would say art is a thing like this. The best of art is a thing like this. This is rich. This is not poor thin soup but a meal we can feast on for a long time and then come back for more. (And when we come back we will find things we did not see or taste the first time!)

He is like us and in this lies his strength. And I think he likes us and in this too lies his strength. Oh and did I say he does tricks with chairs.

I will tell you more. Let us as they say zoom in. In the first room is a pair of lungs or things that stand for lungs. Things made of wood and nail and screw and cloth which go back and forth as if they pump and move the air. And there are screens and on the screens is light and dark. Folk walk and dance. W K too is on the screens. He does tricks with chairs (and hats too) and he walks. I think I saw once he had a stick but I might be wrong. Once he bore a young girl round his neck and walked with her on the screen. He looks you might say sad but no more as if he is in deep thought. He looks at the world. And there are such sounds now here now there it is like a spell. It is a sweet pain. And there is print and type—there are words and there are sums. Now there now crossed out now smudged now clear to read but hard to grasp what it all means.

What does ‘means’ mean? What does it mean to say art, or a work of art, means? Hmm. Though not hard for sure to feel. Not thoughts but a way to feel. The strange words and the maths make you feel. The words and the dance and what you see on the screens make you sad and glad too (and your heart beats fast). And there are folk who come and go in a long line like in a march they come and go. They come in one end and walk and dance and march and then they go out. And you smile and you think hard and you see them there and then you are there and you are them. Oh a dream of life. Oh a real hard life. Oh a life of hard dream. All pass us by. King and queen and poor and knave and prince and thief and saint and the well and the sick those who live and those who will all too soon die and those who have died they pass by us, and show us the way things are and the way things might be, both the best and the worst of it. There is filth and dirt and there is joy and a bright light and there is dark and there is space. Look! It goes on and on dark and dark. The man ails—the girl does a dance. The man jigs a jig—the girl is sick. The bird flies. The old man lives—the young girl dies. A man is in a fat suit. He looks like a great white pea. She plays a tune on a thing of brass. The clock ticks. And ticks. Oh look now there is a flash. A flash of light. It is so bright. There is death. There is an end. But look now things flow once more. There is life. Here is a new start.

Things in a row. Things put in a row in a space, the right space. A space on a wall a space in a screen a screen in a space a space in a space. A gap. A pause. To look at— to put in the right space since this will help to make us feel and see what it might be like to be one who is not us.

I want to say W K is not cool. He dares much and this can make him trip and fall. (One piece I will not say which is not as good as the rest. What do you think?) He might fall on his face. At times he lacks grace. But so do we all. He does not fear this fact and this gives him strength. He does not seem to fear what folk might think. I like this. I do not like cool. I do not care for when art folk act as if they do not feel or they do not fear or hurt or love. As if this is not the stuff of our short life. And I do not like it when they claim this lack is good that to not feel is for them some sort of good thing.

There are six rooms in all I think and all will make you feel and make you think new thoughts and a warm shock will run down your spine now and then in all those rooms. (One just one is not so good I think. Which one do you think it might be?)

There comes a point where words cease to be of help. Where they lose their point or at least their edge. For just think if we could gloss the whole of a work of art why would she or he who made it want to make it—the art ? There comes a point where words must stop where we must look and feel and not say. And if we know when to stop it seems to me we are wise and we know how to live. And in a way I think this work might help us to know how to live.

Michael Szpakowski October 2016

A Book Review for Benjamin Peters’ How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet, The MITPress, 2016

“At the philosophical scale, the abundance of information and the plurality of worldviews now accessible to us through the internet is not producing a coherent consensus reality, but one riven by fundamentalist insistence on simplistic narratives, conspiracy theories, and post-factual politics. We do not seem to be able to exist within the shifting grey zone revealed to us by our increasingly ubiquitous information technologies, and instead resort to desperate modification strategies, bombarding it from the air with images and opinions in order to disperse and clarify it. It’s not working.” -James Bridle [1]

In Benjamin Peters’ “How not to Network a Nation” we learn that the USSR had the engineers with the technical knowhow and capacity to construct national computer networks of scale. Indeed, the Soviet military had such a network already in the 60s, but the question Peters wants to ask is why the USSR did not develop a ‘civilian’ computer network akin to the Internet we know and love today. The USSR did not develop a ‘civilian computer network’ because there was officially no part of the society which was independent of the state. Also, by the time anything approximating what we call the Internet began to emerge in the US, the USSR was already deep in decline. Thus, Peters’ question is moot and he only finds what is obvious from the beginning: that the social system of the USSR was incompatible with the liberal information-sphere of the capitalist West.

The book, though, should be praised for opening up and translating to English various documents, not yet available, which describe the work of early Soviet cyberneticists, and for mapping the institutional vicissitudes of the USSR at the time. We learn, for instance, about the brilliant cyberneticists Anatoly Kitov and Viktor Glushkov and their travails attempting to gather institutional support for a national civilian computer network in the USSR. Glushkov’s atrophied OGAS project forms the central narrative of the book, a project for an Inter-network of computers proposed years before Vint Cerf coined the term Internet in 1972. However, rather than appreciating the precocious cybernetic accomplishments of early Soviet theory, Peters blandly uses the “failure” of the OGAS to argue that the USSR was too perversely corrupt and bureaucratic to let progress take its course.

“Because the OGAS threatened to reorganize the social and economic spheres of life into the kind of national planned system that the command economy imagined itself to be in principle, it threatened the very practice of Soviet economic life: in [Eric P.] Hoffman’s analysis, “creates more choice and accountability and threatens firmly established formal and informal bases of power throughout the entrenched bureaucracies” [2]

Interdisciplinary historical studies of the academic, philosophical life of the USSR in English are sorely needed. Peters is sadly not sufficiently technically competent to give the reader any substantial insight into the structural concepts or proposals of the early USSR cyberneticists. It is certainly not clear from the information in the book whether any of the proposals would have produced anything akin to the Internet. In order to compensate for inadequate knowledge of political economy Peters sadly defaults to half-hearted liberal reproaches.

“Glushkov’s vision directly opposed the informal economy of mutual favours that oiled the corroded gears of Soviet production. In the end, the OGAS Project fell short because, by committing to rationalize and reform the heterarchical mess that was the command economy in practice, it promised to encourage the rational resolution of informal conflicts of interest — which worked against the instinct to preserve the personal power of almost every actor that it sought to network.”[3]

For readers interested in how the various prototype networks in the USSR (the OGAS, ESS and EASU) technically actually worked, anything about the USSR military computer network (analogous to ARPANET), how USSR computer industry differed from that of the capitalist countries, o how USSR computer theory differed from that of the capitalist countries, the book experience will be disappointing; it has too little of this. What’s really lacking is a strong attachment to the subject, the meat and bones of the OGAS, its material scale, how the projects actually ran, on a daily basis. Peters’ seems more passionately concerned with reasserting that capitalism is better than socialism because it produced the Internet.

Peters’ thesis is specious: “The first global civilian networks (sic) developed among cooperative capitalists, not among competitive socialists. The capitalists behaved like socialists, and the socialists behaved like capitalists. “ [4] The capitalists in this formulation are merely individualists, who, to Peters’ mind, surprisingly cooperated to build the network. The socialists, in his formulation, are altruists who couldn’t live up to their principles, competing with each other for resources like professors in a badly run faculty. Peters unfortunately appears not sufficiently interested in either socialism or capitalism to nuance these historically heavily-laden terms.

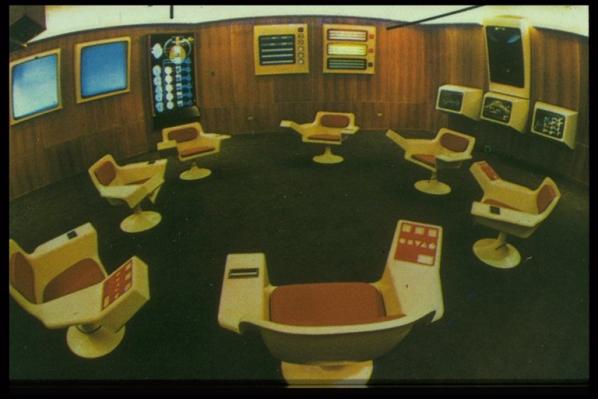

The utopian project, imagined by the Soviet cyberneticists for the USSR and exemplified in the Cybersyn project in Chile, was that a socialist society could manage the entirety of national production distribution and disposal more efficiently and effectively through an internally transparent communication system. Cybersyn was, however, no prototypical Internet. Such a network as Cybersyn would also likely have to be highly secure (since national security would depend on it) and the data exchanged there only selectively available to an exclusive few. Thus, such a system would not likely have produced the vibrant media environment of the Internet we know today.

Peters does not technically imagine how such alternative forms of networked computation might work. Instead he consistently returns to the vague claim that the USSR was too ideologically conflicted, flawed and corrupt to allow the flourishing of the genius of figures like Glushkov to permit the panacea of an Internet-like network to be developed there. “The history of the OGAS project is akin to the history of a miscarried effort to perform an IT upgrade for the corrupt corporation that was the USSR itself.” [5] And cloaks his disparaging attitude in befuddling doubletalk. “The Soviet network projects did not fail because they did not possess the engines of a particular Western political or technological values. They broke down for their own reasons.” [6]

What reasons? They broke down because there could be no Internet in the Soviet Union.

The book points out that the difference that created the conditions for the development of a civilian network such as the Internet was the fact that the US had a private sector which could fund research and production independent of central governmental approval. Curiously, Peters’ gives the example of Paul Baran, inventor of the packet-switching technology essential for the Internet as we know it today, who, seeing his projects disregarded by the priorities of the military industrial complex at the time, eventually abandoned it, only to see it implemented in the US after the British Post system’s research generated the same idea. Here we have two “socialist” government-funded communication projects in “capitalist” competition, apparently the secret to the technical success of the Internet.

A Soviet civilian network, equivalent to that of the nascent Internet in the US, would have meant a network of scientific/academic institutions working outside the classified military information-sphere. There was no such “civilian” sphere. What Peters shows instead is that many of the efforts to implement a national computer network outside of the military were reformist, intending to ‘liberalize’ the Soviet economy and make it more compatible with the capitalist West. “Most of the new employees [of Glushkov’s state-of-the-art cybernetics institute CEMI] were young researchers with bold ambitions and a distaste for the culture of totalitarian control in the 1940s and 1950s. Enthusiasm for decentralized economic reform met with central flows of funding”. [7] Glushkov’s senior ally in the bureaucracy Vasily Nemchinov “sought to impose ‘economic cybernetics’ and its plausibly nonsocialist “dynamic models of balancing capital investment” in the ideologically most acceptable light”. [8]

Peters points out that the USSR’s ideals of social egalitarianism were superimposed on a society which was not used to such a distribution. It is often argued, that, unlike Germany (which Marx & Engels had in mind when they wrote their Manifesto) pre-industrial Russia was lacking the institutional, industrial and economic basis for socialism. The result was that the highly abstract egalitarianism of socialism clashed with the conditions on the ground there, and generated more contradiction, inefficiencies and strife.

The promise of socialism, though it is unprecedented, is that a fairer juster society for every inhabitant of the earth can be achieved. The contradictions between the ideal and the reality need to be allowed to run their course, but this time was not afforded the USSR, as it was not afforded Chile, Cuba, Venezuela, Congo or any other nation which have dared strive for an egalitarian society. Lenin, Allende, Castro, Chavez, Lumumba came to power through popular and democratic processes but were attacked mercilessly, undermined, even assassinated by intolerant reactionary alliances from without and within. Remember that minerals from the de-liberated Congo [9], fundamental to networked computing today, are extracted under the most extreme injustice and exploitative coercion.

Peters claims the the US “succeeded in “networking a nation” because its ethos is to ask “how“ rather than “why”, and that the USSR failed because they were too concerned with “why.” The inertia of systemic unfairness socialism has to confront is immense, and, since it must deliver on its promise to improve the living conditions of the great majority, it is understandable that considerations of “why” will slow down technological choices on a national or global scale. The US and Western economies under their influence had much less of such moral compunctions. Capitalism “frees” entrepreneurs to scale ideas up to industrial scale and ‘externalises’ any deleterious consequences. Today in the age of automated techno-industrial-powered environmental degradation, resource wars and climate change, it appears far too late anymore to ask “why.” Networked capitalism has long had the answer to “how”, though: more computers.

It seems Peters wants to say with this book that socialism can be good as long as it takes place within capitalism. But since Peters’ conflates capitalism with individualism he does not see that this would mean socialist practices merely serving their conventional function as unquantified subordinate contributions to rationalizing capitalist exploitation. When Peters writes that the US built the Internet because their capitalists behaved like socialists, he is merely indicating that socialist practices are a well-spring of the value extracted by capital. Marianna Mazzucato argues convincingly how public investment in fundamental education, technologies and infrastructure brought about the great prosperity (such that it is) and unprecedented cultural affordances such was we enjoy through the Internet. [10] Socialists build things for use value, capitalists build things for surplus value. The huge edifice of Internet-based and coordinated commerce is build on functionalities built in the public interest, not to mention the house of cards ponzi scheme of contemporary financialized capital. The grand juggernaut of US capitalism is still running on infrastructure built during its brief social democratic experiment in the 1950s, which itself was a concession to labour in order to ward off nascent communism at home.

Jeremy Corbyn aims to produce a surge of public investment in vital infrastructure, which, in the proceeding decades it can be assumed, will be reappropriated piece by piece by capital. Public spending on public services do not produce merely quantifiable benefits for “stakeholders”; they produce qualitative improvements which cannot be reduced to commodities, and therefore do not require computer networks to manage or employ, but on which we nevertheless all depend for our social lives.

It is fashionable today to envisage that we are heading, or should head towards a sort of “Fully Automated Luxury Communism” (FALC), where an Internet of Things, transparently managed through a hive-mind, public-access liquid-democracy interface, a civic HyperCyberSyn, will provide unprecedented industrial efficiency and irrepressible prosperity, automatically for all. History shows however that such a system would be set upon and usurped by powerful alliances, just as has every technology in the history of humanity, for the benefit of the few and the detriment of the many. In the meantime, instead of FALC, we get Opportunistically Accelerated Predatory Rentierism, cyborg capital serving a persistent fully-automated financialized rent extraction system.

Peters attempts to close the book on a conciliatory note. “Neither American-style capitalism nor Soviet-style socialism should be considered a sufficient philosophical banner for making our way into a networked world… The social necessity of restraining self-interested competition unites, not divides, the modern legacy of cold-war capitalism.” [12] Peters’ appears to propose that capitalists (in his taxonomy) are the true socialists since they acknowledge the limits of their self-interest whereas socialists are dangerous because they must pretend as if self-interest doesn’t exist. But what can the benefit of this caricature conciliation of socialism and capitalism be? Only if we can mutualize the rentier system for the benefit of all according to their needs will we generate societies of sustainable social and economic justice worth the name communism, with all the myriad revolutionary technological affordances we can barely imagine today.

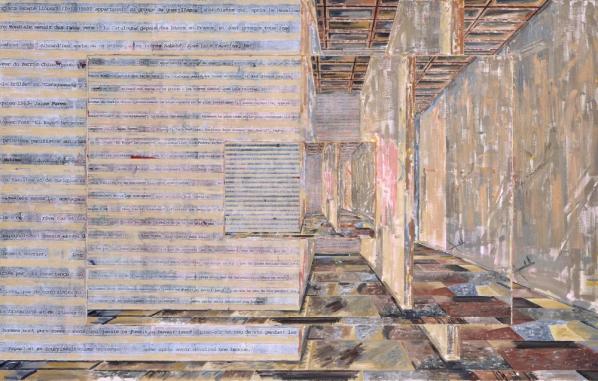

The exhibition Power and Architecture was created for viewing across several months in a particular sequence. Part 1 focused on Utopia and Modernity (12 June – 3 July), Part 2 on Dead spaces and Ruins, (July 4 – August 10), Part 3 on Citizen activated space — Museum of Skateboarding,(11 August – 11 September), and Part 4 on The afterlives of Modernity — shared values and routines, (15 September – 9 October). A conference held in June – The Centre Cannot Hold? –led by important scholars Michał Murawski (SSEES, UCL) and Jonathan Bach (New School, New York) served to frame the cultural, political, economic ramifications of “centrality and monumentality in 20th century cities” with thought from prominent researchers, architects and artists. Power and Architecture concluded this October as the Calvert 22 Foundation partners with innovative architecture, design and engineering collectives Assemble (UK), Museum of Architecture (UK) and reSITE (CZ) and an Urban Research Mobility Lab connects London with Prague by asking the question: how does migration and mobility in cities affect the experience of the urban environment? A curated series of reports, essays and photo stories further explored the themes of Power and Architecture in the online Calvert Journal available through the gallery website.

Calvert 22 is a gallery devoted to contemporary Eastern European and Russian art. They presented this exhibition as “a season on utopian public space and the quest for new national identities across the post-Soviet world.” I arrived at the gallery, a Californian artist, coincidentally just as I’d read comments from Lev Manovich about the young intelligensia of post-Soviet Russia. Thus, when thinking about the exhibition, I was also thinking about the new global mobile class and the impact of Putin’s Russia upon a new generation.

Power and Architecture is a fascinating collection of research into contemporary art, films, and research about post-Soviet urban identity and the positioning of artists therein. Obviously once communist societies have experienced dramatic change since the fall of the Berlin Wall, collapse of Soviet Russia, and rise of Putin to power. Curators used multiple cultural lenses with which to pry open a critical “western” eye on the aftermath of the Soviet era and invited exploration of cultural narratives about the “post-Soviet” city. The exhibit, particularly in certain places, looked at ideas which appear to have disappeared or become outmoded as a means of aesthetic and political communication. There was an air of longing and self-reflection towards Russian identity when experiencing the work. The Russian people have something to reckon with; a revolutionary utopia which once was, but which is no more and which has left them with the traces of an almost empire,- although to call communist Russian an empire seems to obscure the politics of the revolutionary element-. These juxtapositions were in essence the heart of the show which explored the Soviet Union as constructed space. This ”location” then functions as a backdrop to present-day national identity and urban design emerges in the portrait of a “post-Soviet” society with its own futuristic ideas as well as in the lingering relics of Soviet intentions.

Power and Architecture falls on the heels of Calvert 22’s very successful Red Africa program which examined the cultural, economic and social geography between Africa, Eastern Europe, Russia and related countries during the Cold War. The Eastern European art historical and social trend of the last thirty years labelled ‘self-historicization’ –or the self-conscious effort for Eastern European and Russian artists to articulate, archive, and collect their own history, is exercised throughout the exhibit itself designed in series of presentations directed at the problem of “historical understanding” of history. The post-Soviet city and utopian public space was used as a critical framework from which to position contemporary space, identity and the intent of the exhibiting artists. The Soviet Union has fallen, but who or how is its revising and re-examination taking place?

Part 2 which dealt with “dead spaces”, the architectural ruins of empty cities, military bases, technologial infrastructure and cavernous, open landscapes at once modern and moribund seemed to suggest that retrospective analysis of utopia could only be a well-conceived guess at what was or might have been. This Part was a sojourn into the life of Soviet artifacts both remaindered in their historical trajectory and as a convincing backdrop to a pervasive contemporary ambivalence. Danila Tkachenko’s “Restricted Areas” for instance, was a series of photographs documenting relics of the military build up of the Soviet Union only to be found on abandoned, snow-covered sites in the frozen tundra. Oversized photographs of personal ID cards from unknown persons presumably found amidst Soviet architectural rubble, large format, richly-detailed color photographs of crumbling rooms, weather-worn, orphaned Soviet-era paintings, and peeling, once colorful murals inside Soviet military bases and institutions form an historic record of obvious and shocking lack of preservation of Soviet art and architecture as Russian history. Artists participating in Dead spaces and ruins were Vahram Aghasyan, Anton Ginzburg, and Eric Lusito.