Featured image: Image from the movie ‘Frankenstein Conquers the World’ directed by Ishirō Honda, a 1965 Kaiju film.

“Nature builds no machines, no locomotives, railways, electric telegraphs, self-acting mules etc. … They are organs of the human brain, created by human hand; the power of knowledge, objectified.” [1] Marx (1857-8)

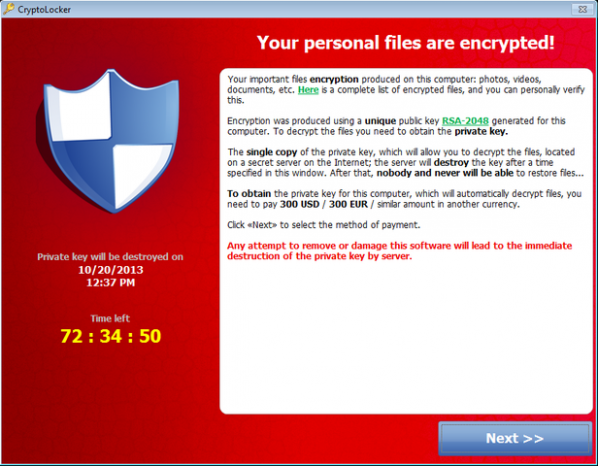

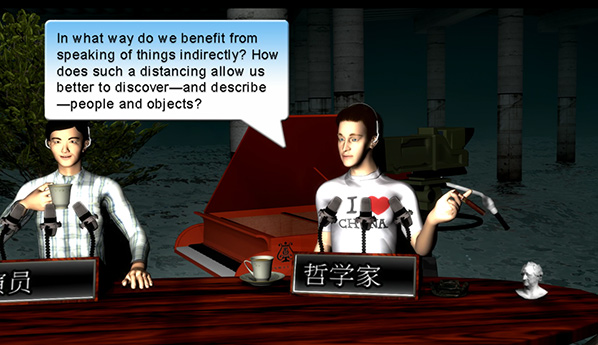

This writing roots out a few ideas concerning science and technological determinism and humanity’s bond with digital media and social networks. The themes are covered in terms loosely as to what they may symbolize. It looks at our fears relating to technology, human-machine relations, cyborgs, theories in cyber-culture, classical and SF literature and contemporary art practices across the fields of media art, hacktivism, activism, feminism and cyberpunk.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is the focus for this text but it also brings into the mix, Greek mythology and Prometheus – the Titan, and what the myth symbolizes, asking, in what form does he exist in the world today? It is a playful assemblage of unresolved contemplations that have been sitting around asking for light in the back of my mind. This is a stripped down version of the original study about mythology, technology, fear and revolution.

Humans have always exploited the raw materials this planet has to offer, and has the power to change the nature of things, whether it is physical or virtual. With constant re-edits and enhancements we transform everything we touch and this is all part of our evolutionary mutation. [2] The word ‘technology’ originally comes from the Greek word tekhne, meaning art and craft, the making of useful or good things. The ‘ology’ part means to discuss something or a branch of knowledge and common form. In Greek Mythology Prometheus was a demigod and a Titan worshiped by craftsmen. “In Greece the Titans were ultimately honoured as the ancestors of men. To them was attributed the invention of the arts and magic.” [3] (Graves 1964)

First, we begin with an apocalyptic vision of what could be and what it looks like when something strange occurs in the oceans. In July 2011, an article in the International Business Times featured a phenomenon we’d normally expect in a science fiction novel or movie. The headline read “Millions of Jellyfish Invade Nuclear Reactors in Japan, Israel” [4] Then the Reuters news web site mentions another jellyfish invasion at a Scottish nuclear power plant, in Torness. “An invasion of jellyfish into a cooling water pool at a Scottish nuclear power plant kept its nuclear reactors offline on Wednesday, a phenomenon which may grow more common in future, scientists said.” [5]

On whether this occurrence is significant and poses future threats, the International Business Times said, “The several [power plant] incidents that happened recently aren’t enough to indicate a global pattern. They certainly could be coincidental, Monty Graham, a jellyfish biologist and senior marine scientist at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab off the Gulf Coast of Alabama stating, told LiveScience.” [7] However, some say jellyfish may be the only species worth fishing in European waters if trends in overfishing are allowed to continue. In an article in the Telegraph in 2008, it said, “scientists have said that unless the system is completely overhauled fish stocks will continue to deplete to the point of extinction by 2048, leaving consumers little option but to eat jellyfish or the small bony species left behind at the bottom of the ocean.” [8]

In September 2013 another mass of jellyfish forced one of the world’s largest nuclear reactors to shut down. The Operators of the Oskarshamn nuclear plant in Sweden had to scramble one of their three reactors after tons of jellyfish clogged the pipes that bring in cool water to the plant’s turbines. “By Tuesday, the pipes had been cleaned of the jellyfish and engineers were preparing to restart the reactor, which at 1,400 megawatts of output is the largest boiling-water reactor in the world.” [9]

“New research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that the rise in jellyfish populations may not only be aided by climate change, but is also contributing to it by making oceans more acidic, thereby disrupting their function as carbon sinks.” [10] (Land 2011)

Since the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 trust of a state’s handling of dangerous technology has taken a dive. We need only to look at Japan’s recent experience of technological disaster with their nuclear power stations. This brings us to the notion of risk and what this means. In the 19th Century risk was no longer about nature, it changed, it extended to us humans and our conduct. “This extension was due in part to the singular appearance of the accident, a kind of mix between nature and will.” [11] (Ewald 1993) […] Thus “no progress without associated damages.” [12]

Gareth Edwards, director of the 2014 Godzilla movie, starts with a 10 minute recap of “nuclear bomb tests from Bikini Atoll featuring voluminous apocalyptic mushroom clouds and a full-blown Fukushima-like nuclear power meltdown.” [13]

Since the 19th century fears about technology and the notion that scientists are meddling with creation itself has been in the public’s consciousness. Many view Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as triggering these long-term concerns. Of course, these fears are subjective, but also include people’s concerns about not having control over how technological decisions are reshaping society. After all, many lives have been lost due to brilliant uses of technological advancement made specifically for the act of killing many, as with the development of nuclear and biological weapons.

“Two international treaties outlawed biological weapons in 1925 and 1972, but they have largely failed to stop countries from conducting offensive weapons research and large-scale production of biological weapons.” [14] (Frischknecht 2003)

Using biological and chemical weapons was condemned by international declarations and treaties, notably by the 1907 Hague Convention respecting the laws and customs of war on land. Efforts to strengthen this prohibition resulted in the conclusion, in 1925, of the Geneva Protocol, which banned the use of asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, usually referred to as chemical weapons, as well as the use of bacteriological methods of warfare. [15]

“Let us now consider what happens when you make the epistemological error of choosing the wrong unit: you end up with the species versus the other species around it or versus the environment in which it operates.” [16] (Bateson 1972)

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has given us much to chew on, ranging across gender politics and history, including symbolic, political, psychological and social themes. Shelley was the daughter of writers Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. Godwin is one of the forefathers of the anarchist movement and most famous for two books published within one year: An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, an attack on political institutions, and Things as They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams, a novel that attacks aristocratic privilege, but also is the first mystery novel. Based on the success of these publications, Godwin was a prominent figure in the radical circles of London in the 1790s. [17]

Mary Wollstonecraft was a writer, philosopher, and advocate of women’s rights. During her brief career, she wrote novels, treatises, a travel narrative, a history of the French Revolution, a conduct book, and a children’s book. Wollstonecraft is best known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), in which she argues that women are not naturally inferior to men, but appear to be only because they lack education. She suggests that both men and women should be treated as rational beings and imagines a social order founded on reason. Wollstonecraft died at the age of thirty-eight, ten days after giving birth to her second daughter, leaving behind several unfinished manuscripts. [18]

Mary Shelley’s publication, Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus published in 1818, was perhaps the earliest representation of science fiction but it was also a gothic novel. Shelley appropriated the various influences and sources available to her at the time. Her novel is an assemblage of discoveries in science and technology, societal change and political upheavals, mixed with personal interests. In the 19th Century the Romantic poets, artists and writers Lord Byron, Percy Shelley and William Wordsworth explored ideas grounded in their shared rejection of Christianity. Percy Shelley in 1811, declared his rejection of a greater all-powerful being in The Necessity of Atheism saying, “It is easier to suppose that the Universe has existed from all eternity, than to conceive a being capable of creating it.” [19]

In 1817, Mary married Percy Shelley who became her second husband. They enjoyed debating many ideas together and had a passionate relationship. In the summer of 1816, a year before their marriage, Mary and Percy visited Claire Clairmont (Mary’s stepsister) in Switzerland, and also met Claire’s new lover Lord Byron and he was accompanied by a physician called John Polidori. During their stay at a nearby mansion Byron was renting next to the shore of Lake Geneva, they became good friends. Together, they all read volumes of German ghost stories, usually when the weather was too stormy for leisurely walks. Inspired by these ghost stories, Lord Byron issued a challenge for each of them to write their own tales of horror. All immediately began writing them out, however Mary struggled for inspiration taking Byron’s provocation seriously and listened to the various conversations the others had on the subject. Then, her ideas began to evolve once she had discussed at length the radical works of Dr. Erasmus Darwin with Byron. Darwin had experimented with electrical stimulation on dead matter, preserving a piece of vermicelli in a glass case “and by some extraordinary means it began to move…” [20] Hindle (2003)

Both of the Shelley’s were fascinated by Sir Humphry Davy’s publications Elements of Chemical Philosophy written in 1812 and A Discourse, Introductory to a Course of Lectures on Chemistry, 1802. Undoubtedly “the most celebrated and iconic figure of this entire Chemical Age was Sir Humphry Davy (1778–1829), who used his chemical discoveries, his wildly popular lecture series, and his general writings on science, to turn the ‘Chemical Philosopher’ (the term scientist not being coined until 1834) into a figure of social and cultural importance in a quite new way.” (Holmes 2012) more about Davy here link.

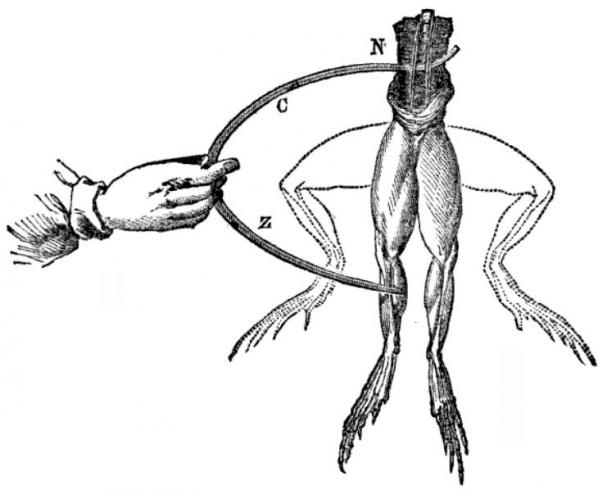

Percy Shelley in his youth “bought and experimented with chemical apparatus and materials and read treatises on magic and witchcraft, as well as more modern scriptures detailing the miracles of electricity and galvanism. [21] Mary Shelley was fascinated with the idea of things being brought back to life via electricity, and also studied the works of the Italian physiologist Luigi Galvini. [22]

Galvini’s experiments convinced him that ‘animal electricity’ resided inside animal creatures. He observed that when using a circuit consisting of a piece of metal attached to the legs of a frog, convulsions would occur. He assumed the spasmodic jolts were an electrical fluid from within the nerves and muscles of the creature. This led to his announcement that he had brought the limbs of the animal back to life. An Italian physicist Alessandro Volta, who in 1800 made the Voltaic Cell, very soon disproved this. The SI unit of voltage is named after him. [23]

Even if creating life out of dead body parts is an unlawful and immoral proposition. Dr. Frankenstein has the whole of history and an extremely well heeled patriarchal system on his side. However, Shelley’s attack is not against all men but a particular type of man. “The first type is the Promethean scientist who uses nature to gain power and abusively alter it, and the second type is the ‘good’ scientist, who respects and celebrates nature and resists the temptation to fundamentally change the way it operates.” [24] (Munteanu 2001) Passages in Frankenstein reveal “Percy Shelley as the initial model for its ultra-ambitious hero, quite apart from the fact that Victory, Frankenstein’s first name Shelley took for himself a number of times in boyhood and later.” [25] (Hindle 2001)

The psychology expressed through the protagonist Dr. Victor Frankenstein is as a man who manages to transform his extreme, radicalized and revolutionary ideals into the form of a monster. This is a personal characterization informed by Shelley’s own experience with Percy Shelley and her father William Godwin. And, even though her love for them is evident, she also had deep concerns about their shared, revolutionary radicalism. Mary Shelley was well versed in the writings of her father Godwin and her mother Mary Wollstonecraft, as was Percy. They both systematically studied the works of Thomas Paine, and this included even conservative thinkers such as Edmond Burke, Abbe Barruel, John Adolphus. [26] (Sturrenburg 1982) Yet, Shelley’s “world view is less political than Godwin’s and Burke’s; it is also far more labyrinthine and involuted when it comes to telling us why things fall apart.” [27] (Ibid)

Prometheus 2.0.

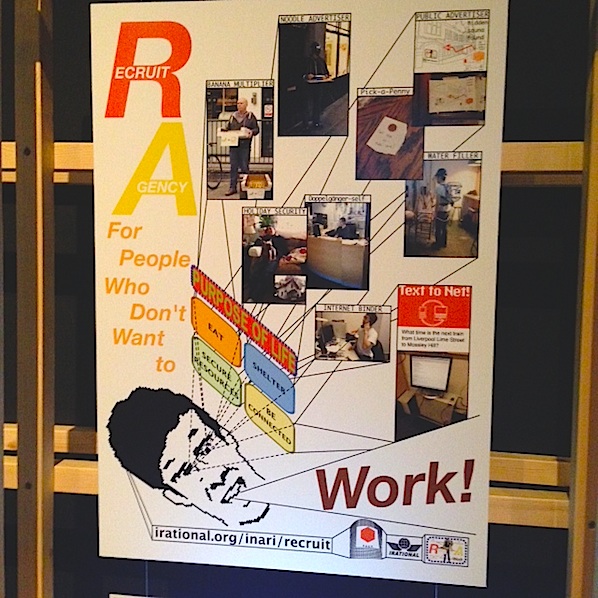

Mary Shelley challenged the cliché narrative of the hero and his belief in the absolute. Her portrayal of Dr. Frankenstein as an egocentric obsessive who will stop at nothing until he completes his mission in bringing his creature to life; represents man’s blind quest in pushing on until the precarious end, at whatever cost. For Shelley, this indicates evident tensions between men and women and their scripted, dualistic roles. This may be an obvious feminist critique now, but in Shelley’s time it was a very different story. Wait a minute! Who am I kidding? The recent interview by Furtherfield’s Ruth Catlow on the New Criticals web site, with the multiple identity female artist(s) Karen Blissett tells us that we are still stuck in this arcane world of male domination. For Karen Blissett, her modern day Frankenstein’s exist in the everyday boardroom in managerial positions as they ‘move forward’ in pushing the top-down, and visionless austerity packages into all aspects of our everyday lives.

“Karen Blissett categorises her most recent artwork Senior Management, An Inspirational Guide, as art for offices […] they demand the impossible. Not in a good way, and not for the enrichment of human futures, but sucking up to power and policy makers – ministers, regulators, corporate leaders – negating their own experiences, demonstrating their loyalty through the implementation of trivial bureaucratic obligations.” [28]

This condition of biopolitics where society is being run by little men affirming their potency through the misleading, heroic trope of managing the life of others can be seen in different areas such as in the military, war, slavery, in education, the media, the economy, religion, technology and science, sex trafficking; on the whole, it is his business to inherit all these power systems from birth. Foucault first mentioned biopolitics on 17 March 1976, during his “Society Must Be Defended” lectures. He described it as a new technology of power and that it exists at a different level, on a different scale, and that it has a different bearing area, and makes use of very different instruments. Foucault’s biopolitics acts as a control apparatus exerted over a population as a whole or, as Foucault stated, “a global mass.” [29]

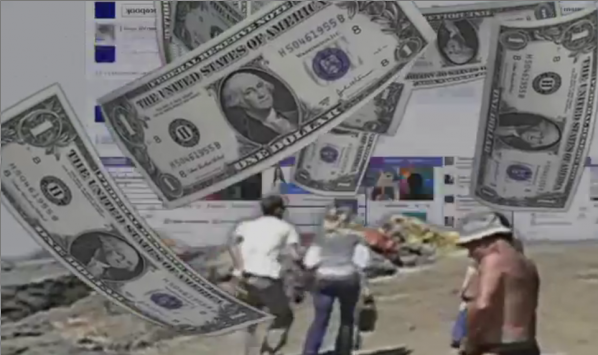

Karen’s monster is neoliberalism, a monster administered by millions of Frankensteins, feeding a globalized monster consisting of networks, machines, weaponry, surveillance, financial control, and elite groups. Keith Fisher in an article called ‘Frankenstein’s Bankers’ on The Global Dispatches web site said “Just as Dr. Frankenstein was responsible for creating a tragic human monster, so are we collectively ultimately responsible for our severely dysfunctional financial system and the activities of its bankers.” [30]

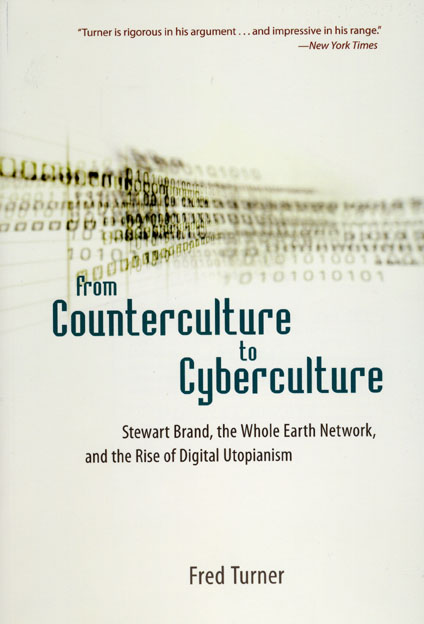

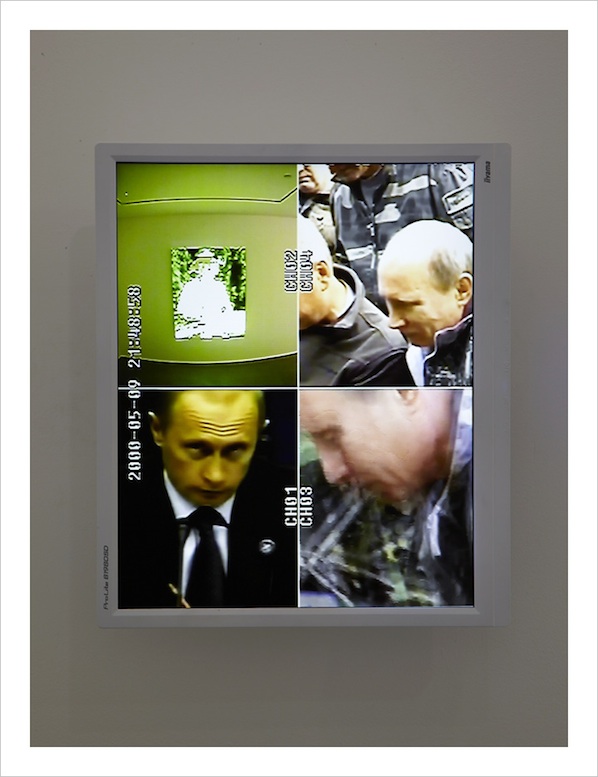

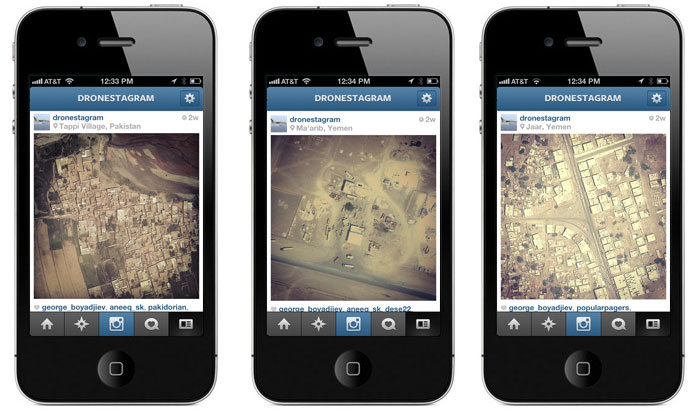

If we take a look at Facebook we can observe that it is an open and free (to use) platform for all, on the Internet. However, the relationship between users and the platforms of Facebook and Twitter are exploitative. In that they treat social media users as consumers of technological services and producers of data, commodities, value and profit. As Simon Penny points out in his essay ‘Consumer Culture and the Technological Imperative’, “One of the classic techno-utopian myths of computers is that access to information will be a liberation, and the results will be, by definition, democratizing.” [31] (Penny 1995) His critique on networked technology and the dreams it once promised us, can now be clearly seen as in dire trouble. Everyday there is a new story about how NSA and Prism are spying on Internet users on mass, Julian Assange sees this as the militarization of cyberspace. [32] (Assange 2012)

SF can pull us into imaginary settings, in the past, present and future, while relating to scientific or technological advances. Some SF looks at major social and environmental changes or portrays space and time travel, and life on other planets. SF has been a generous gift to the world via the minds of original thinkers, showing us a playful side in dealing with the social contexts of technological determinism. It is a third space or outer region where our imaginations can open up different ways to try and understand scientific and technological impacts on society. It is a place where anything goes whether it relates to reality or not. In contrast to the heroic male warrior who is swashbuckling against a mass of aliens to save the world from total extinction or a large-scale catastrophe. Women’s SF has mainly expressed its cultural identity by using “the figure of the alien to describe systems of difference and domination,” [33] (Flanagan & Booth 2002) and Women’s SF and cyberfiction combines exploring the creation of an alien, as the ‘other’. Representing ‘her’ own collective states of alienation in a world consisting of structures maintaining patriarchal dominance, with the female as a techno-product for men to control for their own sexual, financial, administered and power related needs.

Women’s cyberfiction deals with inclusion of the female in societal frameworks where traditionally the male’s tools for engineering, building and use of machinery typically reflect their own practical needs and an industrial and techno-culture designed for them selves. “This dominant class, which is exclusively white and male, operates on a logic of profit and maintaining their control over society, […] it is also shared by white working-class and minority men who are not so well served by it…” [34] (Benston 1992) While many women have jumped into the SF and cyberfiction field they have somehow bypassed the spectacle of techno-utopian rhetoric.

Alongside the growth of technology we are experiencing similar anomalies as with the jellyfish invasions. It is a period where fantasy and reality and the boundaries which once separated them, are breaking up. It’s as if the natural world has now caught up with it’s own version of a post-modern realization. Reflecting back at us a psychosis into material form, the dysfunctional and nihilistic relationship we’ve had with it since our emergence as a race on this planet. Monsters have always demarcated the limits of human folly, telling us when we have pushed things too far. Whether in the form of Godzilla, a nuclear explosion, mutant jellyfish, a war, mining the earth’s resources, and drone technology, spying networks or Frankenstein; they are poignant symbols screaming back at us a painful message. As all the disasters humanity has created pile up, if nature could talk to us in another way and not in the form of our own making – the language of disaster. What would it say and would we even listen?

However, some are recognizing the cultural value of neoliberal monsters. In an interview with Tatiana Bazzichelli on Furtherfield, we discussed her publication Networked Disruption: Rethinking Oppositions in Art, Hacktivism and the Business of Social Networking. Bazzichelli puts forward the notion of disruptive business and that it “becomes a means for describing immanent practices of hackers, artists, networkers and entrepreneurs”, and sheds “light on two different but related critical scenes: that of Californian tech culture and that of European net culture – with a specific focus on their multiple approaches towards business and political antagonism.” [35]

“Monsters have always defined the limits of community in Western imaginations. The Centaurs and Amazons of ancient Greece established the limits of the centred polis of the Greek male human by their disruption of marriage and boundary pollutions of the warrior with animality and woman. Unseparated twins and hermaphrodites were the confused human material in early modern France who grounded discourse on the natural and supernatural, medical and legal, portents and diseases — all crucial to establishing modern identity. The evolutionary and behavioural sciences of monkeys and apes have marked the multiple boundaries of late twentieth century industrial identities. Cyborg monsters in feminist science fiction define quite different political possibilities and limits from those proposed by the mundane fiction of Man and Woman.” [36] (Haraway 1991)

Patchwork Girl was a hypertext fiction created Shelley Jackson in 1995. It is a retelling of the story of Frankenstein. The emphasis is about appropriation and transformation and the female monster is completed, or rather assembled by Mary Shelley herself. “The conflict highlights the monster’s nature as a collection of disparate parts. Each part has its story, and each story constructs a different subjectivity. What is true for the monster is also true for us, Jackson suggests in her article “Stitch Bitch: the Patchwork Girl.” “The body is a patchwork,” Jackson remarks, “though the stitches might not show. It’s run by committee, a loose aggregate of entities we can’t really call human, but which have what look like lives of a sort… [These parts] are certainly not what we think of as objects, nor are they simple appendages, directly responsible to the brain” [37] (Hayles 2000)

Karen Blissett and Patchwork Girl both express more than one part or selves. Haraway proposes that, “The proper state for a Western person is to have ownership of the self, to have and hold a core identity as if it were a possession.” [38] (Haraway 1991) And that “Not to have property in the self is not to be a subject, and so not to have agency.” [39] (Ibid) Blissett is a living collective of female activists expressing themselves as part of a multitude critiquing male dominance and neoliberalism directly.

So, can we re-mutate ourselves in order to loosen the stranglehold of these neoliberal defaults and forge new or alternative states of agency and psychic freedom? Bazzichelli, says “we should stop looking for the enemy, because who is the enemy today when disruption and its opposition are feeding the same machine?” [40] I do not see it as us feeding the same machine in the absolute sense. Sometimes breaking the loop can be more inline to finding meaning and values with others, and yes this can be difficult. But it does not mean that it’s the wrong thing to do.

For me, Bazzichelli’s proposition is an ideal situation if you are not suffering from pressing societal upheavals. As Blissett points out, there are urgent social situations that need attention. Of course, there are those who’ve fallen so deeply into the void of no return, they will happily serve or become a Prometheus monster without a glimmer of soulful insight. Yet, there is always hope for humanity and the artists and thinkers we’ve explored here have proven this. If this article is about anything it is about how the imagination can forge out new ways in becoming something different than the script we’ve been given. The spirit of the Shelleys, Bazzichelli, the Karen’s, Haraway and Jackson, show us that alternatives are out there available for exploration while at the same time we can still maintain our dignity.

References:

[1] Karl Marx. Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy. Penguin Classics; New Ed edition (29 April 1993). Martin Nicolaus (Translator). Page 706.

Note: Written during the winter of 1857-8, the Grundrisse was considered by Marx to be the first scientific elaboration of communist theory. A collection of seven notebooks on capital and money, it both develops the arguments outlined in the Communist Manifesto (1848) and explores the themes and theses that were to dominate his great later work Capital. Here, for the first time, Marx set out his own version of Hegel’s dialectics and developed his mature views on labour, surplus value and profit, offering many fresh insights into alienation, automation and the dangers of capitalist society. Yet while the theories in Grundrisse make it a vital precursor to Capital, it also provides invaluable descriptions of Marx’s wider-ranging philosophy, making it a unique insight into his beliefs and hopes for the foundation of a communist state.

[2] Note: The words ‘evolutionary mutation’ refer to ‘technology’ as a default changing process. This includes the constant appropriation and reinvention of human cultures; altering our psychology, perceptions, traits, anatomy, physiology, our DNA, individual and collective behaviour, relations with: objects, machines, work environments, leisure, tools, tribalism, domestic habits and changing attitudes.

[3] Robert Graves. Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology. Paul Hamlyn, London. 5th Edition, 1964. P.92.

[4] Article. Millions of Jellyfish Invade Nuclear Reactors in Japan, Israel. IBTimes. Jul 09, 2011.

http://www.ibtimes.com/articles/177027/20110709/millions-jellyfish-invade-nuclear-reactors-japan-israel-2011-power-plant-shut-down-unusual-growth-tr.htm

[5] Jellyfish keep UK nuclear plant shut. Jun 29, 2011.

http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/06/29/us-britain-nuclear-jellyfish-i…

[6] Millions of Jellyfish Invade Nuclear Reactors in Japan, Israel (PHOTOS). 9 July 2011.

http://www.ibtimes.com/millions-jellyfish-invade-nuclear-reactors-japan-israel-photos-707770

[7] Ibid.

[8] Jellyfish on the menu as edible fish stocks become extinct. The Telegraph. Louise Gray, Environment Correspondent. 15 Dec 2008.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/3776788/Jellyfish-on-the-menu-as-edible-fish-stocks-become-extinct.html

[9] Jellyfish Cluster Shuts Down Nuclear Reactor. Sky News, 1 October 2013

http://news.sky.com/story/1148872/jellyfish-cluster-shuts-down-nuclear-reactor

[10] Are we entering ‘The Age of the Jellyfish’? Graham Land. Jun 13th, 2011. Greenfudge.

http://bit.ly/1jOMXrw

[11] Francios Ewald. Two Affinities of Risk. The Politics of Everyday fear. Brian Massumi, editor. University of Minnesota Press. 1993. P.226.

[12] Gareth Edwards, director of the 2014 Godzilla – find link

[13] Ibid P.226.

[14] Friedrich Frischknecht. Human experimentation, modern nightmares and lone madmen in the twentieth century. EMBO Rep. Jun 2003; 4(Suppl 1): S47–S52. Science and Society. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1326439/

[15] Efforts to ban biological weapons.

The latter are now understood to include not only bacteria, but also other biological agents, such as viruses or rickettsiae which were unknown at the time the Geneva Protocol was signed. However, the Geneva Protocol did not prohibit the development, production and stockpiling of chemical and biological weapons. Attempts to achieve a complete ban were made in the 1930s in the framework of the League of Nations, but with no success.

[16] Gregory Bateson. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Anthropology, Cybernetics. Publisher: University of Chicago Press. 1972. P491-2.

[17] Bertrand Russell. A HISTORY OF WESTERN PHILOSOPHY And Its Connection with Political and Social Circumstances from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Chapter VI. The Rise of Science. Page 512. Allen & U.; New impression edition (Dec 1961).

[18] Percy Bysshe Shelley. The Necessity of Atheism. C. and W. Phillips in Worthing. 1811.

[19] Note: Erasmus Darwin (12 December 1731 – 18 April 1802) was an English physician who turned down George III’s invitation to be a physician to the King. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave trade abolitionist, inventor and poet. His poems included much natural history, including a statement of evolution and the relatedness of all forms of life. He was a member of the Darwin–Wedgwood family, which includes his grandsons Charles Darwin and Francis Galton. Darwin was also a founding member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, a discussion group of pioneering industrialists and natural philosophers. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erasmus_Darwin

[20] Maurice Hindle (Editor). Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus. Mary Wollstonecraft (Godwin) Shelley. Publisher: Penguin Classics (May 6, 2003). Revised edition, Maurice Hindle (Editor) Author’s Inroduction. P. 8.

[21] Ibid P.8.

[22] Note: Luigi Galvani. During the 1790s, Italian physician Luigi Galvani demonstrated what we now understand to be the electrical basis of nerve impulses when he made frog muscles twitch by jolting them with a spark from an electrostatic machine.

[23] Alessandro Volta. Oxford Dictionary of Science. Sixth Edition. Oxford University Press, 2010.

[24] Anca Munteanu. Shelly’s Frankenstein. Commentary by Anca Munteanu Ph.D. Edited by Dr. Stephen C. Behrendt. CliffsComplete published by Hungry Minds 2001. Chapter 3. P.53.

[25] Maurice Hindle. Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus. Mary Wollstonecraft (Godwin) Shelley. Publisher: Penguin Classics (May 6, 2003). Revised edition. P.XXIV (24).

[26] Lee Sturrenburg. Mary Shelly’s Monster: Politics and Psyche in Frankenstein. The Endurance of Frankenstein. Edited by George Levine and U.C. Knoepflmacher. University of Californian Press. 1982. P.153.

[27] Ibid P.157.

[28] Karen Blissett is Revolting. Interview by Ruth Catlow. New Criticals May 24, 2014. http://www.newcriticals.com/karen-blissett-is-revolting/print

[29] Biopolitics. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biopolitics

[30] Frankenstein’s Bankers By Keith Fisher. The Global Dispatches. November 26, 2013.

http://www.theglobaldispatches.com/articles/frankensteins-bankers

[31] Simon Penny. Consumer Culture and the Technological Imperative. Critical Issues in Electronic Media. State University of New York Press. Editor, Simon Penny. 1995. P.63.

[32] The Militarisation of Cyberspace. Publication — Cyperpunks: Freedom and the Future of the Internet. Julian Assange, Jacob Appelbaum, Andy Moller-Maguhn and Jereme Zimmerman. Or Books, New York and London. (2012) P.33.

[33] Mary Flanagan and Austin Booth. Reload: Rethinking Women and Cyberculture. The M.I.T Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London England. 2002. P.31.

[34] Margaret Lowe Benston. Article 1.2. Women’s Voices/men’s Voices: Technology As Language. Publication – Inventing Women: Science, technology and Gender. Edited by Gill Kirkup and Laurie Smith Keller. Polity Press, 1992. P.35.

[35] We Need to Talk About Networked Disruption, Art, Hacktivism and Business: An interview with Tatiana Bazzichelli. By Marc Garrett – 13/02/2014.

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/we-need-talk-about-networked-disruption-and-business-interview-tatiana-bazzichel

[36] Donna Haraway. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Free Association Books. 1991. P.180.

[37] Flickering Connectivities in Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl: The Importance of Media-Specific Analysis. N. Katherine Hayles. 2000.

http://pmc.iath.virginia.edu/text-only/issue.100/10.2hayles.txt

[38] Donna Haraway. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Free Association Books. 1991. P.135.

[39] Ibid P.135.

[40] We Need to Talk About Networked Disruption, Art, Hacktivism and Business: An interview with Tatiana Bazzichelli. By Marc Garrett – 13/02/2014.

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/we-need-talk-about-networked-disruption-and-business-interview-tatiana-bazzichel

[41] Karen Blissett is Revolting. Interview by Ruth Catlow. New Criticals May 24, 2014. http://www.newcriticals.com/karen-blissett-is-revolting/print

Featured image: Jane and Louise Wilson – ‘False Positive, False Negative’ (2012 Screen print on mirrored acrylic)

The Negligent Eye the Bluecoat Liverpool Sat, 08 Mar 2014 – Sun, 15 Jun 2014 http://www.thebluecoat.org.uk/events/view/exhibitions/1971

Featuring artists: Cory Arcangel, Christiane Baumgartner, Thomas Bewick, Jyll Bradley, Maurice Carlin, Helen Chadwick, Susan Collins, Conroy/Sanderson, Nicky Coutts, Elizabeth Gossling, Beatrice Haines, Juneau Projects, Laura Maloney, Bob Matthews, London Fieldworks (with the participation of Gustav Metzger), Marilène Oliver, Flora Parrott, South Atlantic Souvenirs, Imogen Stidworthy, Jo Stockham, Wolfgang Tillmans, Alessa Tinne, Michael Wegerer, Rachel Whiteread, Jane and Louise Wilson.

The Negligent Eye revolves around the way a digitally-native generation of artists – particularly printmakers – are questioning their relation to the digital, using the notion of ‘scanning’ as a kind of mid-state of the creative process of the human-digital hybrid. The show is co-curated curated by the Bluecoat’s Sara-Jayne Parsons and head of printmaking at the RCA, Jo Stockham, and features several works by her graduates, and other artists from around the RCA, such as Bob Matthews and Christiane Baumgartner. “The relationship between the material and virtual worlds is a question, a set of contradictions we are all inside and how technical images exert their influence on our everyday experience is of ever increasing importance.” Jo Stockham.

In her article Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead? Hito Steyerl asks what happened to the internet, after it died – that is, in an era of the “post-internet” after it stopped becoming a possibility, even in the midst, because of, and symptomized by, its permeation of everything. Steyerl is a major force in understanding our relationship to digital images, and her use of ‘death’ occurred to me often during viewings of this show and surrounding events, particularly as it could be applied to the post-digital.

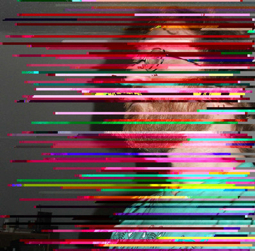

So in a sense, I experienced the show as an autopsy of the digital image. From the tragic, simian face looking out from the first ever digital image, taken by Russell Kirsch of his son in 1950, exhibited at two points in the exhibition like an insistent memory. To Marilène Oliver’s figures from her 2003 Family Portrait series where bodies have been evoked as series of horizontal cross-section prints layered on acetate, so that they appear as though stored, but only partially in this world; the exhibition continually references, exemplifies and unpacks the death of its medium.

The post-digital is a paradoxical term – at once assuming the reliance of all contemporary culture in digitality, but also looking past it; affirming the death of a form, while embodying its afterlife. This is what Elizabeth Gossling’s images of a dead comedian says to me, when it is scanned from a computer screen and printed back on to archival paper, with his image waving from behind an ether of static, living in the solid pulp. The best works in this show, Gossling’s included, speak very eloquently about the post-digital, and how artists are motivated into hybrid forms of production, always acknowledging and working in a context of the saturation of the digital.

The notion of saturation, and its implications of the dissolution and liquidity, itself saturates the show: the first work, Maurice Carlin’s monumental print, scrolling down from the ceiling of the vide space is in one sense a spectral ancestor of Monet’s waterlilies, but with gashes and pustules of CMYK colour oozing up from behind the serine blue and greens of the pond, and white pixel-like rectangles plugging up the gaps; London Fieldworks’ 3D image of data collected from Gustav Metzger’s brain while he thought of nothing, is presented on a screen with a trickling sound – perhaps of information leaking inexorably back in?

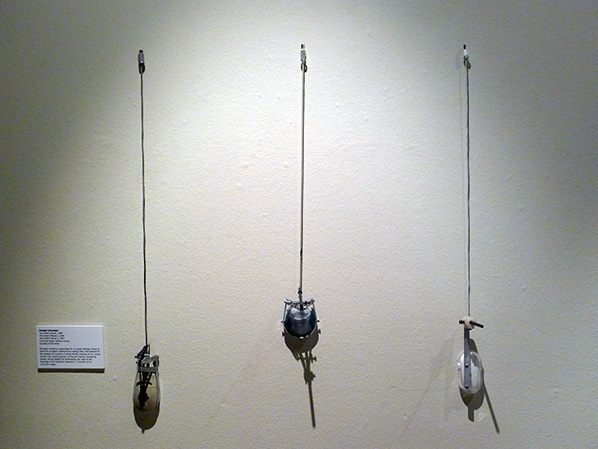

Marilène Oliver’s glitch-sculpture of body parts fused in the heart of the 3D scan/print machine hang in the chute of the gallery corridor, their surfaces mid-ripple as though submerged; Jo Stockham’s etherized black and white shot of an element of the London skyline, seen perhaps through a teary bus window, but now writhing with red in its afterlife as a veined and depthless skin.

Using damage and error to expose the affectivity of a medium, particularly in the context of the digital is the central mode of Glitch Art. I have already used the term glitch to describe the aesthetic of Marilène Oliver’s sculptures, and the traces of digital-to-digital scan in Gosling’s work and the rich material pixilation of Christine Baumgarner’s inscription of CCTV camera stills into largescale wood prints, also contain these signatures.

If there is a criticism to be leveled at these admirable and, frankly gorgeous, works. It is in their distance from what Rosa Menkman refers to as the moment(um) of the glitch. In the medium of print-making, the material fact of the object dominates, and with this show, no-matter the stated and playful interest in the ‘between-state’ of scanning, there remains the focus on material production – and therefore an irrefutable commodification.

Prints on archival paper and tempered steel, casts in plaster and large-scale hardwearing plastics, each speak of an appropriation of the tactical and fluid glitch, and its migration into commodifiable form. Maurice Carlin’s large-scale printwork could adorn a restaurant wall, just as Monet’s waterlilies functioned during his era, and Oliver’s sculptures also speak and modernise the language of sculpture as produced for private collections through the ages.

There are works also which say nothing of the ‘post-digital’, such as Imogen Stidworthy’s Sacha, a deeply thoughtful study of a wire-tap transcription ‘artist’ Sacha van Loo. Stidworthy’s enigmatic works are often hard to pin down thematically, and here it feels like the loft-type space of Gallery 3 has been used as an outer limit to the reach of the show. And then there are other works that say nothing at all and lessen the show’s conceptual rigor. I see Jeaneu Project’s peice, and think ‘smudge lawn’. I see a Cory Archangel print and a Rachel Whitereed miniture and their names flash through my consciousness like a Google Glass press release.

Truly though, this is a really refreshingly vibrant and precient show at the Bluecoat, and a great partner to the Mark Lecky exhibition featured at the venue last year in its pressing contemporaneity. The exhibition has also been a fulcrum for a really interesting series of events which have dealt with image production – including a day of talks and presentations, i-Scan, artist talks from contributing artists such as Imogen Stidworthy, and independently curated events such as the second in Deep Hedonia’s excellent Space/Sound series, where artists such as Madeline Hall, Jon Baraclough, Simon Jones and Andy Hunt explored the multiple angles from which digital scanning can be exploited as a performance and av medium. As with the Mark Lecky show, there is something about the context of the Bluecoat, as Liverpool’s most paradoxical space, which delivers an archival retrospective out of the most up-to-date material, and this tension is what pulls appart the body of works before us.

The Rubik’s Cube is not just a forgotten toy from the 80’s. The fact is that it’s even more popular than ever before. You can play with this great puzzle here.

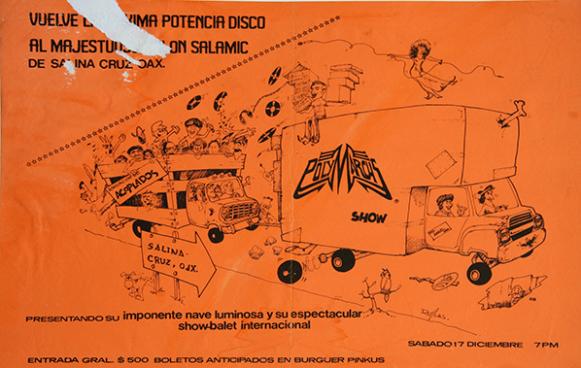

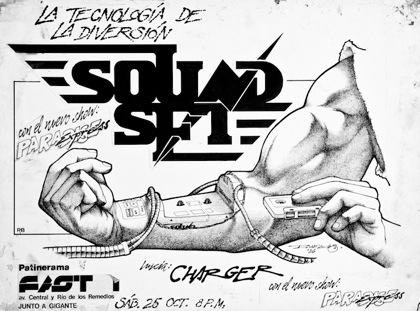

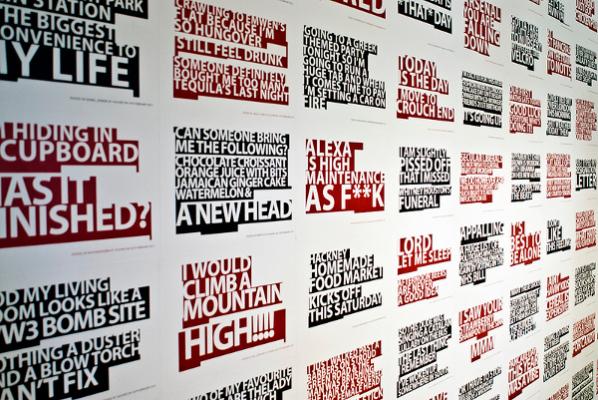

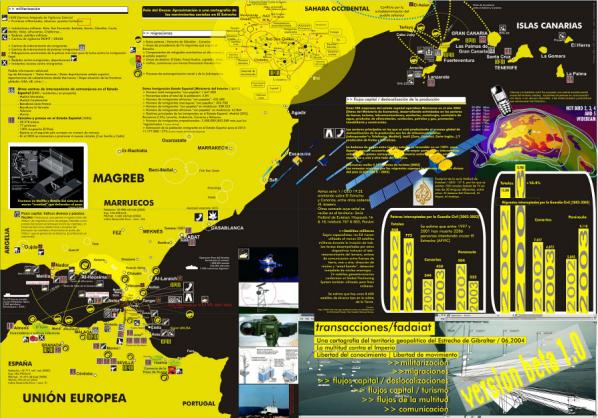

First of 6 articles as part of the Piratbyrån and Friends exhibition at Furtherfield. Mariana Delgado, Coordinator of El Proyecto Sonidero (Mexico), writes about the Polymarchs posters (1980-1990) by Jaime Ruelas. Translation by Tess Wheelwright.

Panther / Jaime Ruelas / Polymarchs. On How We Came To a World of Legend By Mariana Delgado, Coordinator of El Proyecto Sonidero, I met José Luis Lugo in 2009 in the office above the Publicidades Panther print shop in Mexico City. Lupita La Cigarrita introduced us: sonidera, collaborator and number one follower of Sonido La Changa, el Rey de Reyes – the King of Kings. Later we learned from Lupita that José Luis had an important collection of sonidero event posters and flyers. Marco Ramírez, the co-founder of El Proyecto Sonidero, grew enthusiastic.

As soon as we released the book Sonideros en las aceras, véngase la gozadera (roughly Sonideros on the Sidewalks: Bring on the Revelry) in 2012, we began to see what should come next. In 2013 we launched the Proyecto de Gráfica Sonidera, in association with Panther, and in collaboration with draftspeople, poster artists, graphic designers, graffiti writers, sign painters, printers, promoters, collectors and researchers.

We are taken back to the origins of the tropical sonidero movement, which began in the 60s with turntables and LPs – loudspeakers and tweeters set up in the streets, dances thrown in the barrio. Over time various sound systems are added, each with its own crew; soon the multicolored Aztec or robotic lights are streaming. The biggest parties feature close to 50 systems at once, working simultaneously for hundreds of thousands of people. Music is introduced and mixed the Mexican way. Equipment is fiddled with; beats are slowed. Bass rumbles out from walls of speakers. Followers take their places and multiply along with vernacular genres. Transsexual dance clubs form circles on the dance floor; here a family, there a group of insiders – la banda – make their way through the crowd. The mic starts up, amplifying the shout-outs that will circulate the continent on CD and DVD, through streaming, links, posts. From Peñon de los Baños aka Colombia Chiquita to Neza York; from the barrio Tepito aka Puerto Rico to Chimalwaukee, out to all the brothers in Illinois.

In this world, all hatched from La Sonora Matancera. Cumbia and salsa are the queens of a grand court of rhythms. The Virgin of Guadalupe reigns supreme; it’s her congregation. Changó, San Judas Tadeo, and the Santa Muerte share the power thereafter. Epic is important, and family, too. What begins as a passion for Cuba soon builds: music from Colombia, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, the Dominican Republic, Buenos Aires, New York… The sonideros leave behind the established Mexican labels and their standardizing limitations, heading out on their own to comb the continent. They become vinyl diggers, import records, discover bands and musicians; they turn into promoters, create record companies and pirate labels, compile mixtapes to disseminate in the street markets and plazas, at parties and on commercial stands, through the internet.

In the margin within – those more notorious neighborhoods of the Distrito Federal – embroidered logo jackets circulate, lending publicity to the sonidos along with their cards, posters, flyers, banners. Nonetheless, fewer and fewer dance parties are thrown. The city government has issued a discretionary ban of sonidero events in public spaces, canceling even traditional dances like the anniversary celebrations of Tepito’s markets. In the outer margins, ringing the DF and beyond, painted walls announce upcoming events and sonido trailers take over the streets. The dances go on.

We aren’t as familiar with the electronic scene, headed by Polymarchs. Our inroad is through the graphic materials comprising the collection Panther has amassed since 1979, which he rightly considers his primary asset. It all began in the Zona Rosa, where he used to go to trade posters, leaflets, stickers. At thirteen he formed part of the Polymarchs crew, coiling cables. Later he became a publicist, promoter, producer. He never stopped his gathering; stacks of paper tower in the office. Hundreds of posters and dozens of original drawings from the golden age of Hi-NRG pass in front of the camera, as José Luis remembers key scenes and events from this world: when they brought Gloria Gaynor to Mexico for the first time, when Sylvester came, when they packed the World Trade Center.

We are introduced to the world of artists and designers who created an imaginary to suit the precursors of the genre: pharaonic, galactic, utopian, spectacular, and futuristic. Always epic. Tailored to the moment, to the experience of the fans. The posters of the electronic sonidero movement are unique in format, employing unexpected techniques and materials; they are distinct, painstaking, sensational, new. In contrast, the works of tropical sonidos follow in the typographic vein of Mexico’s Gráfica Popular – reminiscent of the wrestling, taking the freedoms of the tropics, whether with box cutter or in full pixel. In the world of disco, Hi-NRG, and techno, the graphics are like the sound system: cult objects, concepts, myth.

“Do you want to meet Jaime Ruelas?” asks José Luis. The master of ink drawing, creator of logos and illustrations as iconic as La Changa or Polymarchs themselves. Of course we do. We are his fans, and we are an army. We arrive nearly punctually to the interview, with photography, audio and video gear in tow. Nearly punctually, because Jaime is already waiting; the son of a watchmaker, he knows machines, design and sound from the inside. He also knows the history of Polymarchs well, and from the beginning. Polymarchs’s first gig took place in his apartment in Tlatelolco. Later, Jaime became the sonido’s first DJ, before switching his focus to images.

Like the sonidos thriving now in the capital, Polymarchs began in Puerto Ángel, on the Oaxaca coast, with a modest set-up – just a single Telefunken console and two baffles. The collective was formed by three siblings in 1975: Apolinar, Elisa and María de los Ángeles Silva Barrera. In 1978 they moved to Mexico City. Apolinar took charge of the sonido, and with Jaime Ruelas he discovered disco and Hi-NRG. The tenacity of Polymarches transcends mere selection of musical genres; the approach here is different. With tropical sonidos, the music, the equipment, the role of DJ and MC are the purview of one person, a single all-powerful figure operating from behind the console. Polymarchs is coming from somewhere else, assembling great towers of scaffolding, creating a spectacle, an experience, an environment. Neither DJ or MC, this is an entire machine. Polymarchs designs, produces and operates structures of light and sound as have never been seen before, radiant vessels that travel, carrying immense tech crews and companies of retro-futuristic dancers, from Tenochtitlan to outer space. There are explosions in the cosmos. On the floor all hands are up, cellphones by the thousands.

When Apolinar Silva and the Polymarchs team arrive at the Centro Cultural de España to give a conference in the context of the Proyecto de Gráfica Sonidera, the auditorium is brimming. Followers sport the distinctive t-shirts and jackets, hold up posters they’ve collected, wave cellphones. Apolinar is glowing; he is the supreme authority and, more than mythic, he is mystic. The audience takes the microphone to share their experiences. Like the time a Polymarchs event was organized in Mexico City’s Zócalo and what people thought was an earthquake turned out to be the earth shuddering under such dance. Below, in one of the exhibition spaces, Polymarchs set up a kind of black-light temple, aglow with, among many others, the visions we now share now with you.

The Proyecto de Gráfica Sonidera was an intensive program that resulted in records and research, specialized workshops and others for children, the painting of walls, the exhibition of graphic, photographic, and video material, and a series of talks along with book and documentary releases. We had the honor of including a drawing by Jaime Ruelas, and we kicked off with a dance party dedicated to Polymarchs… which was epic. There was a little boy who stole the dance floor, winning it against the odds from the more seasoned dancers.

All this was made possible thanks to many people and institutions. Shout-outs to the following generous collaborators: Marco Ramírez, José Luis Lugo, Javier Echavarría, Jaime Ruelas, Livia Radwanski, Mark Powell, Mirjam Wirz, Rocío Montoya, Tonatiuh Cabello, Diego Delgado, Alan Lazalde, Sonido Fajardo, Luis Sánchez, Héctor Rubí, Julio Díaz Corona, Sonido Leo, Christian Cañibe, Eduardo “Aníbal” Dueñas, Eleazar “Canuto” Escobar and the shop personnel of Publicidades Panther, Publicidades Lupano, Aisel Wicab, Citlali López Maldonado, Pedro Sánchez, Marisol Mendoza, Lupita La Cigarrita, Sonido Pío, Víctor Hernández, Edgar Ramírez, Laura Zárate, Griska Ramos, Mirna Roldán. Official respects to FONCA, to CONACULTA, to the Fundación Alumnos 47 and to the Centro Cultural de España.

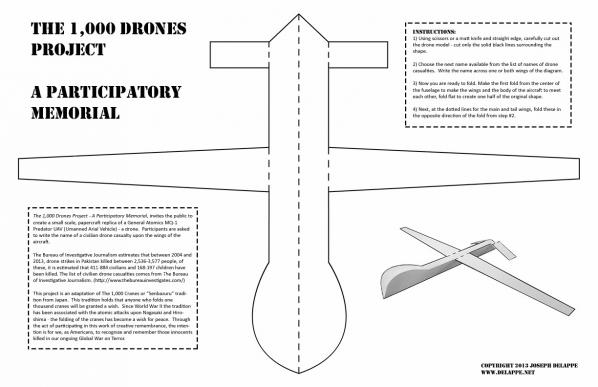

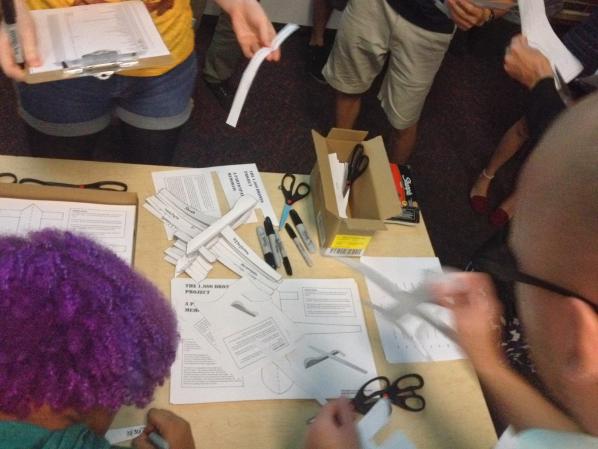

Featured image: Screen capture of Joseph DeLappe’s intervention in America’s Army

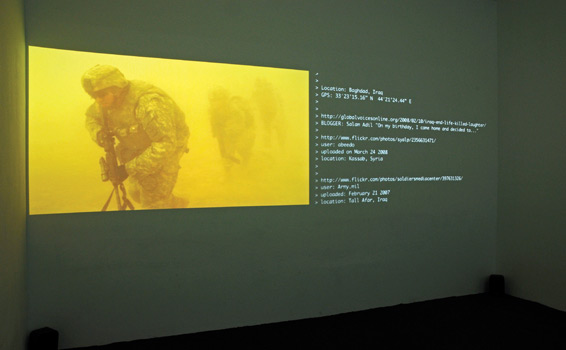

The Fresno Art Museum, in collaboration with the Fresno State Center for Creativity and the Arts, is exhibiting “Social Tactics,” a mini-retrospective of the work of Joseph DeLappe, a new media artist and director of the Digital Media Program at the University of Nevada, Reno. The exhibit has been running alongside the construction of a to-scale sculptural reproduction of an MQ1 Predator Drone on the campus of Fresno State, coordinated by DeLappe and executed by students and volunteers. I had the opportunity to interview DeLappe about his work, and the way it connects to militarism, memorialization, and embodiment. His work has been an ongoing critique of games that look like war, and warfare that looks like gaming – insisting that, within the hall of mirrors that forms “simulation culture,” reality still must be accounted for, and attended to.

The earliest work in the show is a series of riffs on the computer mouse. The “Mouse Mandala” (2006) splits the difference between a trash heap and an object of meditation – a small sargasso of computer mice is ringed by a circle of yet more mice. The outer radius, tethered to the central mass by extended mouse cords, makes the whole sculpture resemble a dingy grey sun – one that has been pawed by innumerable, invisible fingers. His “Artist’s Mice,” first begun in 1998, are a series of mice that have drawing implements attached to them, so that the mice can draw while being utilized for their normal activities. The drawing attachments resemble braces, as though the mice are being rehabilitated from an injury – the drawings produced by them are beautiful abstractions, circular or square scribblings that give the illusion that, while working or gaming or goofing off, we could also be making art – skimmed off the surface of our interface with our machines.

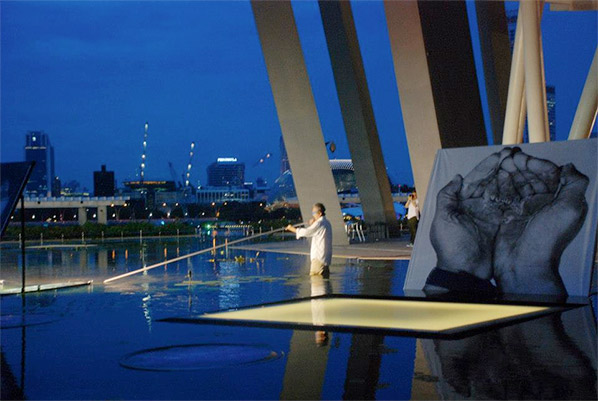

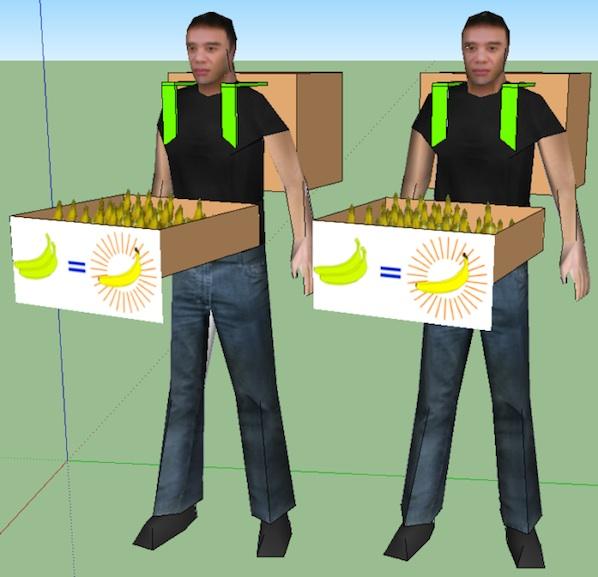

All these mice, removed from the context of their guiding hands, inevitably – if ambiguously – echo with a pair of outsized sculptural hands, titled “Taliban Hands” (2011). Modeled from white plastic polygons, the left hand in particular looks as if it could be cradling an invisible, equally outsized mouse. The right hand has its pointer finger extended, as if it were about to press a button. The fact that the hands are upturned short-circuits those prosaic possibilities of gesture, turning them into gestures of supplication. The hands were constructed from 3D data extracted from the model of a Taliban fighter in the game “Medal of Honor,” and once you learn that, it’s easy to imagine the right hand gripping a gun, the extended finger wrapped around the trigger. The disembodied nature of the hands is discomfortable – it feels like a dismemberment, a pair of hacked war trophies offered up for display.

DeLappe also used polygon modeling for a small replica of a US military Drone that hangs in the gallery, which served as a prototype for the life-size drone constructed as a memorial on the grounds of Fresno State. Where the “Taliban Hands” and drone prototype are white and pristine, the Drone Memorial was designed to be inscribed upon. In a public ceremony, volunteers wrote the names of 334 civilian casualties of drones on the faceted surface of the sculpture.

DeLappe’s years-long project “dead-in-iraq” (2006-2011) is represented by a machinima video and a large-scale digital print modeled after his fallen avatar in the US Army recruitment game America’s Army. Over the course of the American war with Iraq, DeLappe entered the multiplayer first person shooter game, and at the start of each mission threw down his weapon and began typing in the names of US military personnel who had been killed in Iraq. His avatar was invariably shot, either by the opposing team or by members of his own team. In the latter case, it’s as though his killers are trying to gun down an itch of conscience – or the nuisance of reality itself. In the machinima of this intervention, when Delappe positions his camera above his virtual corpse, there is sometimes a very profound effect of quietude. The body occasionally twitches, in a gruesome effluvium of game physics, or puffs of smoke are kicked up by stray bullets – but those filigrees of activity only heighten the feeling that the game has moved on. It brings to mind bodies left on real battlefields, unattended to, abandoned to the weather and the birds and the insects while the important business of fighting continues.

“Project 929: Mapping the Solar” (2013) echoes the circularity of the Mouse Mandala. For the project, DeLappe rode a bicycle 460 miles in a circuit around Nellis Air Force Base in Southern Nevada. The bicycle was outfitted with an apparatus that held a series of pieces of chalk to the road – DeLappe was both marking a chalk outline around the base, and mapping out the dimensions of a solar farm that could power the entire United States, based on a size estimate from the Union of Concerned Scientists. The project is shown through a series of photographs, a video, and the modified bike itself, with a circle of chalk stubs positioned under the frame. In some ways, the piece expands the logic of the “Artist’s Mice” to a different scale. Instead of the hand being the driving force, the whole body is the recorded object, and rather than being confined to the top of a desk, the drawing itself is allowed to range across hundreds of miles. In this case, the drawing is the opposite of accidental – it’s utopian.

Not represented in the show – but a point of discussion in our interview – was the “Salt Satyagraha Online” (2008), a 26-day durational performance which used a customized treadmill to control the movement of a Second Life avatar modeled after Mahatma Gandhi. On the treadmill, installed at Eyebeam Art and Technology in New York, DeLappe walked the 240 miles Gandhi marched in protest of a British Salt tax – driving his avatar, step by step, across the territory of Second Life. That project was yet another of DeLappe’s exploratory reconfigurations of the relationship between protest, performance, and physicality.

Chris Lanier: With the mouse-derived work, from the “Mouse Mandala” to “The Artist’s Mouse” and the drawings that are made as you’re playing a game – what was it like putting those things together at this time, when it’s possible to imagine the disappearance of the mouse? Right now there is eye-controlled software , and even thought-controlled software…

Joseph DeLappe: Part of my thought process when doing the mouse pieces was doing a sort of reverse engineering, and trying to figure out what that thing is, because it really is a useless little object otherwise. It’s not a hammer, it’s not a screwdriver, it doesn’t have a function beyond plugging into a computer to allow you to move around this detached marker on a screen. There’s already something separate happening, and so attaching a pencil to it was a way of perhaps returning it to its roots. It’s sort of a drawing device, a pointer, all these things that a pencil might be, but I was intrigued by the possibilities of extracting some kind of meaning out of it.

CL: It’s funny because it’s an extension from the computer to the human, like an organ that extends itself to us, and I wonder what you think of that interface becoming even more disembodied. If the hand is taken out of that circuit, what do you think that says about our relationship to the screen?

JD: I think it will change it. I can really only speak from my experience, not having played the wii, or things like that. I messed around with the kinect a little bit. When you’re putting the body into works like what I did in the Gandhi project (which is something that’s not in the exhibition) – I placed myself on a treadmill to actually interact with Gandhi, walking him through Second Life. My body became the game controller in a kind of way, the mouse – or however you want to refer to it. I didn’t realize it at first but there was an intrinsic alteration of my relationship to the experience going on, on the screen. I wonder if that deterioration of that awkward physical thing you have to do with the mouse or track ball, if that’s going to bring us closer to our machines. As it becomes gestural and everyday, I suspect it will become more naturalistic.

CL: Listening to you talk about the Gandhi project, it seemed to bring you more directly and somatically into that virtual world.

JD: Which was very unexpected. I went into that project from a conceptual durational performance ideation – this would be an examination of “performance,” in quotes. Performance and protest. It was done at Eyebeam in New York, and I was thinking about the many durational performances that had taken place in New York, from Tehching Hsieh, to Linda Montano, to Joseph Beuys. I had done performance works online for almost a decade prior to that piece, but that action that the body involves, that was just transformative. It was amazing and intriguing and kind of disconcerting in a way, because I found myself completely drawn into that experience, and connected to my avatar in a way that I never had previously. I was walking in Second Life, which you’re really not supposed to do – you’re supposed to teleport – so I was navigating over mountains and in places people don’t generally walk. And Gandhi would fall off a mountain-side into the next region, and I’d find myself almost falling off the treadmill. Or, after finishing the performance for the day, walking to the subway and thinking I could click on someone to get information. It became this mixed reality in my head.

CL: Embodiment seems to be a crucial part of your practice. With “Taliban Hands,” you extracted hands from Medal of Honor, and brought them into physical space. In the “dead-in-iraq” project you brought the names of the dead soldiers into the game space of America’s Army. It seems that bringing bodies into that space, or extracting bodies out of that virtual world, is important to you.

JD: Well, each of those pieces had different but connected intents. With the America’s Army project, “dead-in-iraq,” the intent was to embody the reality of the war, to bring it to this virtual space. So when you’re dying and or you’re killing in that virtual space, and you see these names go across the screen, you realize that this is an actual person that died in that conflict. That might change another player’s thought process about what they’re doing, and about that visualization – when you get shot you end up hovering over your fallen avatar. So there is this attempt to change how one considers that experience.

CL: It’s interesting, with the self-portrait as dead soldier – the way of marking yourself as dead is to show the body within the game. Moving you from a first-person space, a first-person-shooter space, into a third-person space. The body becomes a marker of death.

JD: That is certainly a problematic aspect of that game. I think the vast majority of the people playing the game – certainly there are some veterans and active military – but there are more people who aren’t in that situation. So there is this kind of temporary inhabiting of the US military. Bringing this out into real space is an attempt to drive home the connection of that fantasy pretend space to a very real space. It’s like bringing it to a sort of mid-ground. The America’s Army game is in fact official US military virtual space. I mean they own it. It is federal space – it’s part of the system of hundreds of bases around the world.

With the Taliban hands, it’s a similar attempt, but with a different thought process. With the America’s Army game, one of the most devilish things they did with that game is that they’ve created a system where everybody gets to be a good guy. There are two teams, and you see your team of 2 to 12 cohorts playing against 2 to 12 other cohorts. You always see yourself as Americans. They always see themselves as Americans, but you see each other as terrorist enemies. So there’s this digital switching, where they see your avatar as a Middle Eastern terrorist and vice versa.

CL: The strange thing that happens is that you’re inhabiting two bodies.

JD: Yeah, at the same time, exactly. But in the Medal of Honor game it’s not like that. That was a controversial game when it came out in 2010 because you could play as a Taliban killing American soldiers. It was the only game that was actually banned from military bases. They ended up changing it before they released it – they weren’t called “Taliban,” they were called OP 4, which stands for opposition forces. But you’re still Taliban. So anytime that game is being played as an online match, 50% of the players are being American and 50% are being Taliban.

I found that really curious. I started extracting these maps from that particular game, and then diving into this incredible morass of 3-D data. I would have to dig through all of this wireframe stuff to find these objects, and I found the Taliban and started deleting everything else, and landed at one point with the hands. It was just so intriguing – these hands were gorgeous. When they became disembodied from their source and I started visualizing them in the 3-D software, they took on a kind of Da Vinci-esque quality – like the hand of God or something.

CL: There is a gestural quality to it.

JD: Yeah, exactly.

CL: I’m curious if this work has brought you more into contact with the idea of simulation. Simulation can be useful, obviously – it allows you to think through a situation before it’s actually encountered. But then it can actually introduce errors into the actual [situation], because the simulation doesn’t correspond absolutely to reality.

JD: I don’t know if this connects to your question at all, but if you die in America’s Army – this is standard in most shooter games – they have something called the ragdoll effect. It’s a simulation of your body going limp. It’s meant to give a naturalistic [simulation of] you collapsing, and you’re dead. But the effect is actually quite different – there are points where your avatar, in that space – it can be almost comical, like you’re going to do a somersault. And every time you actually die, your body – because of that ragdoll effect – you watch the video and the avatars do this kind of shaking thing, that’s part of this ragdoll effect. When I first saw it I thought it was this macabre death spasm, but it’s just part of the simulation. It’s not meaningful in the context of the game, but it becomes meaningful in the work that I did and in the recording of it.

CL: It’s funny that a simulation can have these unintentional, almost poetic, effects – if you are attuned to it.

JD: And that’s a good metaphor for the whole project, right? It’s taking this simulated wargame – this recruiting tool – and re-branding it, remaking it. It’s a way to say: “No, let’s see if we can make this game be about this, not about that.” I appropriated the space – I took it over in a simple way, and I think it was quite effective.

CL: You frame yourself as an activist as well as an artist.

JD: Yeah, and sometimes uncomfortably. I drift in and out of that. There’s a difference between being an artist and activist. And right now I’m feeling rather reticent [about the “activist” label] – but I’m an artist at base. It’s a little bit more symbolic I guess…

CL: Making a political act in a virtual space – is that inherently symbolic?

JD: That’s a really interesting question because in the progression of my work, I think my work has slowly emerged towards existing in a real space – with the bike-riding around the Air Force base, and now building a life-sized predator drone down in Fresno.

As an artist you do deal with a kind of symbolic reality – metaphor and symbolism, and things that communicate ideas through form. As an activist it seems there would always be a goal of actually fostering change, making change happen in the world. Whether activism is effective at doing that – that’s a really big question too, right? I’m not sure sure if that’s the case these days. That’s one of the reasons I was interested in going into the America’s Army project. It was seeing the – I wouldn’t say the complete failure – but the invisibility of traditional forms of protest. You had the world’s largest worldwide gatherings of protest, a year before we started that war, which was totally under-reported…

CL: And under-counted.

JD: Right. And I’m not saying that I never want you to go protest in these places, but you do have to push that envelope into places where people would not expect it, to actually reach people. And that was a surprise actually, that that piece resonated so powerfully with others – and became a viral thing that, by accident, was disseminated to a huge audience. That was good. But I’m not sure how I feel about it as a kind of permanent venue for trying to do that kind of thing.

With the “dead-in-iraq” project, there were some people who were criticizing it, saying, “Well, you’re just sitting there at your keyboard.” It’s like: “Yeah? Right. I know that – that’s part of the point. Everybody playing that game is sitting at their keyboard.”

CL: And the people who are manning drones are sitting at their keyboards.

JD: Precisely, and that’s exactly one of the reasons I’m so interested in drones. Speaking of embodiment, the drones –it’s like a perfect synthesis of computer gaming culture, and our militarism, and our love for the latest possibilities of technology. It’s like somebody bashed those things together and out came this perfect system for blowing shit up on the other side of the planet – sitting in your comfortable gamer’s chair.

CL: The way you’re activating the Drone Memorial as an extension of your art activism – I’m wondering if part of the appeal is doing it within an educational institution, where you’re enlisting students to help you out, so it actually becomes part of an educative process. How much do they know about the drone policy?

JD: What’s interesting with that project is that they brought up these different groups – art students, design students, and there has been a group of activists from Fresno called Peace Fresno who’ve come out to work. There have been some TV interviews, and there’s a journalism class – they’re taking turns, every day there’s a different crew and they’re documenting the process and interviewing the people that are involved. And it’s been interesting talking to some students because there have been a number of students that are like: “What, drones? We can blow stuff up in Pakistan, from sitting in Las Vegas at Creech Air Force Base?” They don’t know about it, so there is a kind of basic informational aspect of the project.

But what I’m finding most interesting is that the students and volunteers – and myself – at this stage of the work we’re so absorbed in the embodiment, if you will, of the physical sculpture. It’s a building process and there’s a kind of pleasure in that. There’s the hands-on aspect of building, and seeing this form come into being. What I’m waiting for is that realization when we get the whole thing together, and it has this 48 foot wing span and 27 foot fuselage, sitting on the ground at the campus – and then we write the names [of the civilian casualties on the sculpture] – we have 334 names in English and Urdu.

I think that’s going to have a powerful impact, that’s going to completely flip the equation. Not just to give them a sense of their making something as a community build – but that we own these drones – we are this policy. These victims that are on the drone are connected to us, right? There’s a direct lineage from that pilot sitting in Creech Air Force Base, from the missile that rained down on that village and killed a 12-year-old girl, to you and me. It may be tentative, but it’s our government – it’s us.

Conclusion.

The interview was conducted several days before the completion of the Drone Memorial. After the sculpture was assembled and installed, there was a public ceremony at the site. Afterward, I asked Joseph if the effect of the ceremony was in fact what he envisioned, and he sent me the following reply via email:

We finished the drone just as the ceremony was scheduled to commence. There was a crowd of about 75 people – I made some brief comments thanking the volunteers and the CCA. The actual ceremony was being coordinated by a wonderful group, “Peace Fresno”, who coordinated the creation of individual, hand written index cards, each with the name, date of death and age (if available), of each of the 334 Pakistani drone victims. These were read aloud by individuals from Peace Fresno of Pakistani or Indian descent to ensure that the names were correctly pronounced. Those gathered for the event stood in line to take possession of a name after it was read aloud – walking towards the drone where they were given a pen. Each name was written with the associate dated of death and age of the victim when available. Several volunteers followed this process by filling in the names translated into Urdu.

I personally completed the process of standing in line, taking a pen and writing names on the drone 7-10 times, I lost count. The most memorable was that of an 8 year old girl – I don’t recall her name but after writing on the drone the realization of the death of a child was quite overwhelming. Others had similar experiences – there were several walking away from the drone after writing their name who were in tears. This cycle of writing, standing in line and continuing the process went on for perhaps 45 minutes until all 334 names were written upon the drone. All the while there were passersby stopping, asking what we were doing, some joined us. I recall a father on a bicycle have a discussion with his young son about drones, “are you ok with being surveilled 24/7?”, that kind of thing.

In my exhaustion after working 2 weeks followed by an additional weekend of 11 hour work days, the experience was moving and quite overwhelming. There was indeed a palpable realization of the nature of the project. The camaraderie established among the workers and volunteers evolved into a collaborative process of memorialization.

“Social Tactics” runs through April 27, and the Drone Memorial will be on display through May 31.

Joseph DeLappe’s website: http://www.delappe.net

A previous furtherfield interview on another drone-related project by DeLappe:

The 1,000 Drones Project, by Marc Garrett – 05/02/2014, furtherfield.org

http://furtherfield.org/features/interviews/1000-drones-project-interview-joseph-delappe

News story on US Military objections to ‘Medal of Honor’:

Sales of new ‘Medal of Honor’ video game banned on military bases, by Anne Flaherty – 09/09/2010, Washington Post

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/09/08/AR2010090807219.html

News story and video on the Drone Memorial:

Drone project at Fresno State a call for ‘contemplation’ (video), by Carmen George – 03/26/2014, The Fresno Bee

http://www.fresnobee.com/2014/03/26/3845089/drone-project-at-fresno-state.html

Fresno College Newspaper story on the Drone Memorial:

Drone sculpture construction begins, by Collegian Staff – 03/18/2014, The Collegian at Fresno State

Drone sculpture construction begins

Essay on the visualization of the “Enemy” in military games, with a focus on “America’s Army”:

The Unreal Enemy of America’s Army, by Robertson Allen – 01/2011, Games and Culture 6(1):38–60

http://www.academia.edu/231295/The_Unreal_Enemy_of_Americas_Army

Featured image: Pablo Garcia’s presentation at Resonate 2014

Resonate, the Belgrade, Serbia digital arts and design festival, now in its third year unfolds over a long week at the start of April. Its central tenet is to bring together “artists, designers and educators to participate in a forward-looking debate on the position of technology in art and culture.” It is also an emerging and challenging festival that raises many more questions than it answers. The festival starts off with a number of workshops held by practitioners for practitioners. Foregrounding the demystification of the creative process immediately sets it apart from any number of other media arts festivals. Whereas many festivals might be broader in their approach to what the digital can include, and focus on themes that don’t always feel like they directly influence what happens in the festival, Resonate doesn’t give itself a curatorial focus. But, and so, the workshops set the festival off with a focus on making. Most people who come to Resonate are just that: makers of work. It feels as though there are fewer curators, producers and academics here than you would expect.

Resonate, the Belgrade, Serbia digital arts and design festival, now in its third year unfolds over a long week at the start of April. Its central tenet is to bring together “artists, designers and educators to participate in a forward-looking debate on the position of technology in art and culture.” It is also an emerging and challenging festival that raises many more questions than it answers. The festival starts off with a number of workshops held by practitioners for practitioners. Foregrounding the demystification of the creative process immediately sets it apart from any number of other media arts festivals. Whereas many festivals might be broader in their approach to what the digital can include, and focus on themes that don’t always feel like they directly influence what happens in the festival, Resonate doesn’t give itself a curatorial focus. But, and so, the workshops set the festival off with a focus on making. Most people who come to Resonate are just that: makers of work. It feels as though there are fewer curators, producers and academics here than you would expect.

This year, shifting location from 2013’s Dom Omladine, perhaps learning from some of the problems of last year’s over-heated and occasionally too-tightly packed events, they have moved to a spread of venues, with the base being the Kinoteka Cinema, a sleek-looking modern building with a number of different spaces. Any decent festival has a spread of overlapping events making it impossible for one person to attend everything. Resonate makes no apologies for being just as packed with events as any other festival. The one time it might be possible to sit and spend a day in one place is if you’ve managed to get on to a workshop event that takes place on the Thursday. Once the workshops are over though, Friday kicks off with the panels and presentations. Choreographic Coding discussion, led by NODE Forum’s Jeanne Charlotte Vogt opened the panel discussions. A broad ranging talk with Raphael Hillebrand, Florian Jenett, Peter Kirn (CDM), Christian Loclair and Klaus Obermaier, (returning again after last year’s Resonate, possibly being an ongoing presence at the festival). All of the panel talks took place in the central lobby of the Kinoteka, which proved to be a terrible choice for anyone who wanted to actually hear the speakers. At times the discussions descended into a barrage of mumbles blending with the sound of people emerging from surrounding presentations and the poor choice of PA equipment placements. A shame, as the themes for these were well chosen, including Ways of Seeing, chaired by Greg J. Smith of HOLO magazine, and Generative Strategies, across the Friday and Saturday. The best laid plans of mice and journalists. I had planned to interview a number of presenters during the event, key amongst them was Pablo Garcia, who was on a panel and presented his own work on the Saturday. Apart from a brief conversation, we finally caught up over email several days later. I fired a number of questions at him, which are dotted across the rest of this review.

Do you find that Resonate offers something different than some other digital festivals? If so, what might that be? “It feels a lot like some of the better festivals I have seen, like EYEO. It is selecting from the best digital artists/makers out there, and giving them free reign on the stage to talk and share. The city has a great vibe and the overall feel is truly a “festival”, and not so much a conference or academic gathering.” ~ Pablo Garcia.

Friday’s talks included Cedric Kiefer (Onformative) giving a presentation in Gallery of Frescos, a short hop and stumble from Kinoteka Cinema. I’ve always enjoyed the juxtaposition that occurs when digital media is presented in contrast to, in this case, a venue “exhibiting in one place the highest achievements of Serbian Mediaeval and Byzantine art.” In other words, old stuff that enforces the modernity of the digital work we are being shown. Kiefer’s presentation covered some of their major projects including their work for Deutsche Telekom which used the company’s Facebook interactions to create beautiful data visualisations (Facebook Tree – 2013). There’s an unabashed acceptance of the interaction between corporate funding and creativity on display with many of the presentations. It’s something which never provokes debate, at least not in any of the conversations I had with participants or the panels I attended. Maybe that’s no longer ‘a thing’ that concerns creatives and the money required for some of the bigger projects has to allow for corporate sponsorship? I’m not suggesting we shouldn’t embrace funding from wherever it comes, it would just have been nice to have some debate around it.