Featured image: Urinal, 2011, 3D printable digital model. Model by Chris Webber, commissioned by Rhea Myers

Rhea Myers is an artist and programmer and keen advocate of the Open Source Software culture and community. Much of the work he creates and the ideas he explores are rooted in sharing; making works that are available for others to use in their own way. This concept can be something of a paradigm shift for a traditional art world – where the notion of an artist as someone visited by the muse and given divine insight into some aspect of the world around us reigns supreme. We imagine said artist sharing their visions through one-off artefacts that become valuable in the competitive marketplace of the consumerist commercial art world.

The Shareable Readymades project works within the realms of Net art, but Shareable Readymades are output as a real-world object. Using a downloadable, freely licensed 3D model of the art work, Shareable Readymades can be printed using modern 3D printing technology wherever the equipment is available. The code for creating the 3D models is available on several websites including Rhea Myers’ own Github account. The artefacts are scalable, which gives the option of deciding what size – up to that of the original item – they print at.

Beyond the idea of a ready-made artefact is the thought, lingering in the air between creation and conception in this work, of the digital blueprint for it: the Blender file (Blender is the 3D software used to model the work). Given the digital and mechanical process involved in creating the work and the tightly wound connection between them, it might seem difficult to know where in the process the work actually comes into existence? Perhaps it is easier to think of the entire process as being the product itself. With 3D printing another possibility emerges: that 3D printing isn’t the total artefact in itself. In industrial design, pieces are created to give real form to objects and allow designers to have a tangible example of what they are trying to develop. They become a step in the production and act as a conceptual point in a longer process. Rhea Myers’ Shareable Readymade Urinals are close to the conceptual nature of Duchamp’s ‘readymades’ – specifically Fountain – because they will never become functioning objects. In our understanding, they increasingly come to represent ethereal objects removed from function, or a discussion about the increasingly fuzzy line between everyday objects and objects defined as ‘art’.

There’s a process of induction into ‘being’ involved and part of this is the commissioning. Myers commissioned the 3D models from Christopher Webber and then made them publicly available for download so that anyone can own an original piece of art.

In Abstract Hacktivism, Otto Von Busch and Karl Palmas lay out an argument for reconfiguring the way we think about the world around us. Tracing a path from Michel Serres through to Manuel DeLanda, they argue that new developments in technology change the language and by corollary, the way we frame our thoughts about the world. As DeLanda has said:

“He [Serres] sees in the emergence of the steam motor as a complete break with the conceptual models of the past. […] When the abstract had been dissociated from its physical contraption [the actual motor] it entered the lineages of other technologies, including the “conceptual technology” of science.”[1]

The essays in this all-too-short book end with the personal computer and how we think about society in terms of hardware. The authors only briefly touch on the emergence of software as a means for constructing metaphors for contemporary life, and Rhea Myers’ ‘readymades’ take this even further, encountering the idea of production.

The digital production and mechanical output perfectly summarise so much about life in the 21st Century. Our understanding of consumerism itself is gradually changing thanks to the growth of Internet shopping. We select our produce from a database of text and imagery. Yet we still believe in the freshness and perfection of the perfect apple – selected according to standards and criteria set by an army of corporate non-entities. The artificiality of the image of the apple could be taken as a reflection of the artifice of the marketplace shopping ‘experience’ we’re led to believe still has some semblance to our forebear’s means of hunting and gathering. Sometime later we take delivery of a perfectly formed apple. The difference between the database version and our own is so insignificant that they may as well be the same thing.

The urinal – the ‘original’ Duchampian urinal – appears in the art history continuum like the database image of the apple. The perfect version waiting to be analysed (read: consumed) by potential shoppers (read: art historians). Every version is now perfect and exactly what we ordered, in exactly the colour we requested. There is little opportunity for malfunction and serendipity in the process. Art becomes exactly what we ordered it to be. Fresh, ripe and leaving no bad taste in the mouth afterwards.

Sadly, what Duchamp missed out on was the final phase in the act of converting everyday objects into art. He should have realised that the real act of art-world transmutation was to then convert them back into everyday mass-produced objects. Thereby proving that art is merely a phase that things can pass through as and when the artist says they do. However, perhaps contextualising Rhea Myers’ project within the marketplace lends itself too easily to the idea that the artworks are for sale? It would be a mistake to imagine that the point of this project is to create a new way of purchasing and owning art. An intrinsic aspect though, is the Open Source and unrestricted dispersal of the idea and ability to create your own version. Ownership, in the traditional sense of that word, isn’t being claimed by Myers. Creating your own version means that you outright own that object. In a more traditional art environment, even though you may have contributed to a piece of work (some Fluxus projects might come to mind. Yoko Ono’s art, to name just one) you still won’t be credited with ownership or creative partnership status. The market relies on the single authorship model. Multiple unnamed authors would just get confusing and complex when copyrights start to be discussed. Locating the project within Open Source means that ownership is not claimed, but credit should be given where credit is due. When art collectors talk about merely looking after a work for the next generation, they’re talking about a continuum of ownership running through the decades. But art reduced to a commodity is saying nothing of any real value, surely?

By choosing to download and print a version for yourself you have the opportunity to own the work and be a part of that disruptive process. Owning a piece of art that comments on the past, present and future of the art world and marketplace must surely be something to desire and possess?

You can find Mark’s original article on Collaboration and Freedom – The World of Free and Open Source Art http://p2pfoundation.net/World_of_Free_and_Open_Source_Art

Part of the Furtherfield collection commissioned by Arts Council England for Thinking Digital. 2011

Featured image: Internet Cache Self Portrait, 2012, Evan Roth

In an essay for the catalog of Collect the WWWorld: The Artist as Archivist in the Internet Age, an exhibition installed most recently at 319 Scholes in Brooklyn, Josephine Bosma announces that the wilderness is back. Though modernity provided the means for humans to sequester themselves safely in comfortable houses, sheltered from nature’s seasons and its bad moods, Bosma points out that the boundaries between the indoors and outdoors, between the private and the public, have been broken down by digital technologies. As data slips into our most intimate spaces, the way rain and wind once ripped through primitive shelters like caves and huts, we return to “a rather basic form of humanity”―an uncanny “21st century version of ancient cultures and traditions.” Sorting through an “erratic, uneven mess” of information, human beings are once again hunters and gatherers. [1]

Yet if hunting and gathering are back in digital form, the foraging is not taking place in a scarce economy. We are not looking across vast space for some edible calories, stalking after evasive prey. Instead, we are flooded with resources in an official archive that grows at almost unfathomable speeds. In his catalog essay, curator of Collect the WWWorld, Domenico Quaranta writes,

“Every time we access a web page… the browser memorizes certain data on our computer… whatever we don’t deliberately delete, we keep. In the cache era, accumulating data is like breathing: involuntary and mechanical. We don’t choose what to keep… but what to delete.” [2]

The artists in the 319 Scholes exhibition appropriated and manipulated images, data, animated gifs, video, clip art, and blogs to create screen projections, net art, prints, and installations. Often they transferred foraged data into sculptural pieces, such as the series of pocket bikes by Jon Rafman and the photocopier run amok in Jason Huff’s Endless Opportunities, suggesting that online information moves in and through our material world. Moving through the gallery made me feel like I had spent too much time online, overwhelmed by too much information. There were hundreds of polaroids in Alterazioni Video’s Olbania, hundreds of images in Evan Roth’s collage Internet Cache Self Portrait: July 17, 2012. The title of the seemingly nonsensical Etsy purchase by Brad Troemel, displayed on the gallery wall, captured the detailed randomness of the internet space: Art Smells Why Wait Grab An Unusually Decadent PINE air freshener with a HOTTOPIC pink to black hair extension attached. The sounds of Eva & Franco Mattes’ My Generation dominated the gallery’s front space. In a pile of smashed computer hardware, a screen displayed videos of hormonal teenage boys freaking out, screaming, and convulsing in front of their computer cams. The collage captures the overflowing, hysterical emotions of adolescents in their now private-public bedrooms but also the frustration that we can feel about life amidst so many networked devices and so much data.

Since many of the works at 319 Scholes made me feel psychologically unsettled and dispersed, the same way I feel after staring at a screen all day long―a feeling that I can fix only by unplugging and taking my dog for a walk―I asked Quaranta how he differentiates Collect the WWWorld artists from the larger population of people interacting with data as simply just hunter-gatherers on an everyday basis. How did he imagine the exhibition representing something beyond what we all do continually, as naturally as breathing? His response:

“Everybody stores, but just a few collect. Storing means downloading (or tagging, pinning, posting, etc.) something and forgetting about it. Collecting means taking care of what you stored, selecting and ordering it according to a personal criterion, applying a human filter to the inhuman, impersonal archive. If the collector is an artist, his collection may be sometimes understood as art.” [3]

If we keep with Bosma’s ecological metaphor, Quaranta’s exhibition, then, presents artists who are also collectors and archivists who, having explored the digital wilderness, have done some weeding in order to plant a garden of cultivated, nurtured, looked-after data. Their art is a gesture toward trying to make some sense or order out of the wildness. In his catalog essay, Quaranta writes,

“Collect the WWWorld takes as its point of departure the very moment an incoherent mass of ideas turns into a hypothesis.” [4]

Yet ever since digital media emerged on the contemporary art scene, artists have been appropriating found “objects” from the internet’s ever-growing archive, remixing them to create new content. But there is a significant way in which Collect the WWWorld captures a new cultural current. Traditionally, archives were protected spaces, governed by authorities, institutions, the state. They were private, physically and politically remote from the public at large, inaccessible except to sanctioned experts who were able to pass through the proper channels of bureaucracy. Digital technologies upended this sanctified space, producing an unofficial endless archive of internet data, and more recently, with ubiquitous mobile networked devices and social networking applications, anyone can upload any random aspect of their mundane private lives into the public archive. Quaranta explains,

“If in the past, and still in the late Nineties, appropriation and remix were dealing mostly with commercially produced culture, now most of the cultural content we access, consume and remix is produced by so-called amateurs.”

In the Web 2.0 world of YouTube and Facebook, brokers, editors, and even curators are no longer indispensable. There are no intermediaries between public and private in the digital wilderness. Furthermore, Quaranta adds, early generations of digital artists were pioneers. Now, the born-digital artist-collectors are “residents dealing with the stuff left by their ancestors.” [5]

In this exhibition of second-generation digital art, the most intriguing works in the show were those that did not simply repeat and represent the experience of hunting-gathering in the wilderness but rather intervene in this process to suggest the ways that media technologies rewire our culture, our public/private spaces, and our imagination. In Kevin Bewersdorf’s Google Image Search Result for “Exhausted” Printed onto Blanket, an image of an emotionless father holding a passed out son in his arms. (I’m guessing at their roles; the situation could be much less innocuous.) With the printing of this random, private scene onto a blanket, someone could actually sleep in with this odd couple, laying his skin next to theirs. The networking of such intimate moments is at once ludicrous, meaningless, and meaningful―and something that those of us with web access experience all the time.

In need ideass!?! PLZ!!, Elisa Giardina Papa has collected online video of mostly teenage girls excited to make new video content except they have one major problem: they have no ideas. The projection at 319 Scholes showed them speaking intimately into their video cams, begging their viewers to help them, confessing their willingness to do anything asked of them:

“Hi YouTube, Hi you guys, Hey um YouTube…. I wanted to start a web show and I need ideas for it but I don’t know like any ideas. I have the web show maybe an upcoming website, who knows… Hey YouTube. I’m behind my kitty cat right here. If you guys can give me some ideas I’d greatly appreciate it… Hi you guys I’m Vanessa I’m wondering if any of you can give me any ideas….”

need ideas!?!PLZ!!, Elisa Giardina Papa, 2011

One girl sits on her bed in her pajamas, another stands in front of a shower curtain. Most play with their hair, some have done their makeup, one provides a close up of her glossy pink lips. The kids repeat their willingness to “do anything… crazy stuff.” We often hear laments these days about how new media generate a culture without substance. Papa’s collage―or rather, her collection―deepened this question: the kids turned loose in the digital wilderness seemed to be aimless, armed with advanced technologies but with no ideas about what to say or what to do. At the same time, they perform Bosma’s “21st century version of ancient cultures and traditions.” Papa’s anxious teenagers seek attention, community, and space away from their probably boring parents, a rite of passage of American kids; one girl has to yell into her cellphone at her mother, “Mom! I’m in the middle of a video!” But though they are in the privacy of their bedrooms, they are also begging strangers for engagement and uploading themselves into the public space of the internet, where presumably annoying Moms can check on what they are doing.

In environmental theory, the wilderness can be a spiritual refuge, a space of healing respite from the frenzied modern world. But being out there, exposed, in the wildness of the mountains or the woods is comforting only once we have our biological needs met, once we are safe and ecologically emancipated by adequate shelter, clothing, and food. Social ecologist Murray Bookchin explains this well: “without a sufficiency in the means of life, life itself is impossible, and without a certain excess in these means, life is degraded to a cruel struggle for survival.” [6] With Bosma’s language in mind, I have to ask if Collect the WWWorld represents our ecological emancipation and our freedom to play in a mysterious forest, or if the group exhibition represents our desperate grasp for the basic anchors of cultural subsistence? Evan Roth’s Internet Cache Self Portrait: July 17, 2012 asks who we are in the eyes of our computers, in the accumulated images stored in our cache capturing our travels through the web. Are we the sum of our clicks and searches? Are we the archivists or are we the archived? Are we in control here, or are we engaged in a “cruel struggle for survival” in the digital wilderness?

Collect the WWWorld is a show first produced by the Link Center for the Arts of the Information Age and already presented, in different versions, at Spazio Contemporanea, Brescia (Italy) in September 2011 and at the House of Electronic Arts Basel (Switzerland) in March 2012. The presentation at 319 Scholes, Brooklyn, open from 10/18-11/4, 2012, featured a number of new artists and works in a brand-new arrangement. The show relies on an ongoing research project that can be followed online at http://collectheworld.linkartcenter.eu.

Participating artists include at 319 Scholes included: Alterazioni Video, Kari Altmann, Gazira Babeli, Kevin Bewersdorf, Aleksandra Domanovic, Constant Dullaart, Elisa Giardina Papa, Travis Hallenbeck, Jason Huff, JODI, Olia Lialina & Dragan Espenschied, Eva and Franco Mattes, Oliver Laric, Jon Rafman, Ryder Ripps, Evan Roth, Ryan Trecartin, Brad Troemel, Penelope Umbrico, and Clement Valla.

Someone said to me ‘To you football is a matter of life or death!’

and I said ‘Listen, it’s more important than that’.

Bill Shankly

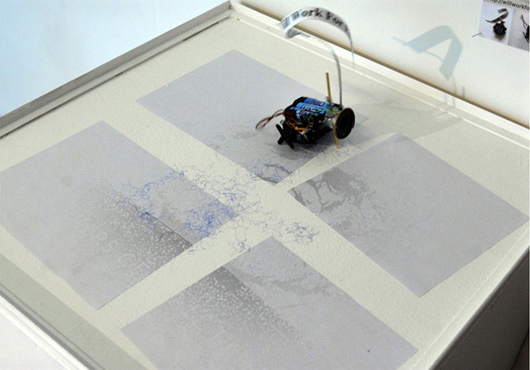

Drawing is one of the two oldest purely cultural – in the sense of playful, not directly concerned with keeping body and soul together like cooking or hunting or shelter – activities that comes down to us today directly in the form of artefacts from between 25 – 35 thousand years ago [1] (the other is music [2]). There is no known human culture that has not made representational and other marks with something, on something, for both fun and survival. Furthermore, as Patrick Maynard demonstrates in his steely eyed and magisterial Drawing Distinctions [3], it can be shown to be the practice which more than any other underpins not only all of present day visual culture (including photography, which, following Maynard [4], we read as a species of drawing) but also the technical developments of our advanced industrial age. With satisfying circularity, drawing, a fundamental tool for engineers and architects, scaffolds the level of production which (by guaranteeing surplus product) is the prerequisite for the very existence of our substantial caste of artists and designers, those useless and indispensable dreamers.

Arguably, then, in a perfect world its study might be counted, with literacy and numeracy, as a genuinely key skill to be studied by all. Certainly, perhaps a more realistic demand, it should be a practice both underpinning and overarching any systematic education in art and design. What concrete shape might this take within the Babel of practices which current art education encompasses?

A couple of years ago the two of us, both from a background in digital art/moving image, started teaching on two consecutive courses – a Foundation degree in Digital Art and Design and its top-up, a BA (Hons) degree in Art and Design Practice. Much of the formal documentation of the courses specified the use of particular kinds of software and allegedly real-world reasons for deploying them (many involving the demands of “industry”). From the start we were antagonistic to this approach. We wanted to “artify” the course – introduce as much experimental, speculative, exploratory, pleasurable and downright pointless (in the way that the best art is both pointless and hugely important) activity as possible. We didn’t abandon the idea of teaching design, but we did decide that the core course programme would henceforth be art/design agnostic – it would deal with ways of making and thinking about images (as well as sound, performance, interactions or concepts) that could be used with profit by students moving in either or both or other directions. It would not be training; work would be driven by the imagination and shaped by the ambitions of students. Teachers would introduce new technical processes, but these would be embedded in thematically organised investigations of historic and contemporary precedents. Help with technique or software might be part of what teachers did, but this would be part of an organic investigation/development by student and teacher together. If a teacher knew something they would help; if they didn’t, they might know where to look; if neither knew, they might search together; if the student knew, they could teach other students and the teacher too. In short we identified a peer-learning process as the only sensible approach sufficient for developing the necessary skills, knowledge and flair in a rapidly-developing field.

Moreover we wanted a course that integrated the digital with every other sort of visual (and conceptual, performative and sonic) practice. We were both impatient with the idea that work made using digital tools, or work created within and distributed across a network, was somehow qualitatively different from all that had preceded it (a not uncommon view often allied to a species of digital mysticism). Indeed we realised we both sensed, and gradually came to articulate clearly, that there was a continuum – a chain – from the cave painter to the contemporary artist. Not to say that social and historical concreteness plays no explicatory role, but that there is some still human centre to mark making (and to allied practices – singing, the telling of tales, etc.) which has persisted and will persist and is part of the territory of being human. ’A chain’ is no loose metaphor, but a precise account of the reality. Inspiration and technique pass continuously from generation to generation. And this is cumulative – making much of the past of art available to its future. In a sense the terrain of art accretes, expands, as time passes. Even what is lost to famine or war, proscription, taste and changes in technology leaves traces, the possibility of reconstruction and re-use (and, often most creatively, misuse). This is what we wanted to instil in our students.

Our drawing sessions link to and are inspired by earlier instances of art powered pedagogy that place cross-form conversation at the heart of learning together. Joseph Beuys made drawings throughout his artistic life – often enigmatic constellations of media, concepts, entities, political figurations and material properties. However of particular relevance here are his extended works, Office of the Organization for Direct Democracy by Popular Vote for 100 days at documenta 5, 1972 and Honey Pump in the Workplace for documenta 6 in 1977, in which he demonstrates his expanded notion of art that is exactly congruous with his philosophy of teaching – ‘to reactivate the “life values” through a creative interchange on the basis of equality between teachers and learners.’ [5] Both pieces required the involvement of many people in processes outside of the realms of ordinary action (such as the maintenance of the plastic pipes of the honey pump as it circulated 2 tonnes of honey through the building) in order that they might connect with unfamiliar concepts and experiences. The artworks integrated many different categories of work (some, but not all, associated with art making) including performance and the practice of various disciplines (of dialogue, rhetoric, democratic processes of exchange and decision making). And yet, in an interview with Achille Bonito Oliva, Beuys makes it clear that he has no interest leading audiences towards an “activism devoid of content” [6]. The liberation of humankind through art (Beuys proposes that everyone is an artist and society is to be sculpted by everyone) depends on a more deliberate engagement of individual energies.

Drawing was particularly important to both of us. It was something Ruth had always done from an early age. Collections of drawings made by her between the ages of six and thirteen depict public street scenes of everyday social groupings and activities (a group of kids running with a dog, two mothers with two prams, businessmen waiting for a bus). The figures are too small to carry facial expressions. Nevertheless their interactions, mood, social status and relationships are expressed by their outfits, gaits, their gestures and their proximity to each other and other elements of the scene. Ruth now looks back on these as evidence of an early growing fascination with sociality. Through school she learned that ‘drawing well’ meant producing an image as much like a photograph as one might render. Praise and grades were awarded accordingly. Later, at art school, drawing became a liberating process of discovery. She generated abstract marks, as traces of energies within the body, rather than to create a deliberate composition within a pictorial plane. In this way she produced surfaces such as might be produced by soot covered animals (think monkey, gazelle, seal, tiger, crow) thrown together into a white room. This surface would then serve as a mirror (or crystal ball) from which entities, gestures and forms of light and shadow emerged to be drawn out in further explorations of aspects of her unconscious.

Drawing was something that Michael aspired to. Because he had come to moving image work – to “being an artist” – by a strange route through theatre, maths and music, he had both a fascination with and a terror of drawing. He had been the kid in the class who couldn’t draw, and yet had loved the feeling, the deep engagement with both the act and with what it awoke inside him –his mind’s eye – that it brought. In his moving image work he had attempted to confront this. The inverted commas that came with a certain species of conceptualism were a great help because he could frame himself performatively, comically almost, as an uncertain but oh-so-willing draftsperson, one with no eye or dexterity, a technical schlemiel.

In his secret heart, though, he knew he wanted to do this thing without (or at least largely without) irony.

Arising out of this obsession, in the early years of the new millennium, Michael had launched a little provocation where he challenged digital artists, as they were then still called, to create self-portraits, on the sole condition that this be done using non-digital means, and subsequently to photograph them for display in an online archive. Those who didn’t baulk at the task produced a touching and intriguing panorama, of pen and paint and pencil but also of bathroom tile, egg tempera and iron filings… [7]

As part of a discussion about this Michael had opined on some listserv or other that the barriers between artistic practices were porous and that the true measure of anyone aspiring to be an artist (musician, film maker, poet) was that, if lost in a deep forest or desert isle, with only a rock to make some marks on and another rock to make those marks with, the putative artist would eventually produce something of interest, depth and value.

Early on we introduced chunks of drawing as an occasional workshop – Ruth introduces, and then builds on familiar art school, Bauhaus type exercises that attempt to separate process from outcome-anxiety, allowing students to engage with an inner dialogue about their looking and representation un-disrupted by fears of inadequacy. These include:

drawing without looking at the paper; from memory; without removing pencil from paper; drawing with the “wrong” hand; drawing in five minutes or five seconds; drawing only negative space; having the pencil trace the movement of the eyeball as the drawer observes an object, etc.

Michael felt the centrality of drawing calling him but these sessions still felt like a slightly naughty holiday, an activity that did not necessarily link to his background and formation as an artist. The teacher, like the student, was still exploring.

The big epiphany came with the introduction of a weekly drawing session for all three years of the course. It happened and happens every Monday of term, without fail, and everyone in the room takes part, staff included. As many days as possible where more than one member of staff is present in the room, to make for debate, thus modelling civilised disagreement and forcing students, ultimately, to make up their own minds; there are usually two members of staff and occasionally more present. Each drawing session is led by a student who brings in an object, procedure or puzzle for the rest of us to address.

What happened is that we were rapidly out-Bauhaused by our students. Byzantine sets of instructions for tasks that we as teachers would have rejected out of hand as overly complex, impractical or confusing were carefully explained by students and then carried out by all of us in utter silence.

Half an hour elapses, we place our sets of images on the floor and we process around them all, discussing them. The important thing is that everyone has drawn. Everyone is both vulnerable and admirable. Teachers are not privileged. For students, it is understood that although the process carries course credit, what is being marked eventually is a series of drawings – some “good”, some “bad”, most neither – and that technique – whatever that is – is not the focus. There must be room for play in creative education; hence, for this part of the course, taking part in all of the sessions is enough to secure a pass.

With respect to collective feedback, our experience has been that perceptive kindness predominates. We search for the wonderful things, speculating on why they are wonderful, maybe asking questions of the person who has made this thing, trying to elicit that week’s secret or lesson. The drawings are a pleasure to behold. We have no intention of reproducing any of them here, though many would bear reproduction – we do not want to betray the egalitarian, labouring-together ethos of the thing by selecting outside the sessions and group. We are not sentimentalists – it is precisely because we understand the necessary element of brutality involved in the fair administration of an assessed course that we want to create oases, visions of how things could be other. It is the collective production of shared work that matters – it is not, let us emphasise though, a privileging of “process over production”. The production matters – desperately so. [8]

Over the weeks, our drawings are diverse in category, style, media and technique including: illustrations of the set task, abstractions, naïve figurations, diagrams, signs; some are performances of processes made in pencil, pen, paper, wood, charcoal, paint, collage, arrangements of plastic objects, paper-constructions; they reveal our choices and learning. Some students advance arguments in their drawings either with each other or with their own earlier work. As new tasks are set we each decide in the moment whether we understand the activity we are to involve ourselves with is mundane, ritualistic (perhaps even sacred), mad or wise, pointless or significant – our conclusions shape our drawings. In this way collective drawing has become central to the ethos of our courses as an integrative practice for negotiating a shared studio culture and shaping our learning together, our movement towards collegiality. Doing the drawing means the week has a start to it – we affirm ourselves as folk with a common interest, different but equal. The sessions have helped to provide a social glue, too, across the three years of the course.

There are areas where we as teachers know more than the students; both of us have track records of work in the art world, but the drawing sessions level us all – they enable a mutually supportive but acute look at progress on a common task. Since the drawing started we have also incorporated its lessons to other disciplines; staff and students share their photography work in a more horizontal way than the demands of the course would normally allow. We use new forms of social media, and have Flickr accounts in which all participants are contacts.[9] We comment on and “favourite” each other’s works as equals and collaborators.

Both drawing and photography in these contexts devolve to something similar – filling a blank space by mark making, with valuable, experiential knowledge accrued: repeating processes many times over to find out what constitutes skill and when (often, it turns out, much more often than is often acknowledged) to accept the gifts brought by chance; discovering that the art happens in a social space between the maker, the wider world and the viewer; understanding the work of others because we do it side by side; and, finally, coming to grips with the question of personal style and the diversity of ways of doing things well and meaningfully.

Each week reveals both artistic phylogeny and ontogeny – we solve the problem here and now, as if for the first time ever and this illuminates the historical chain, the intertwining of theory and practice, our mutual dependence, all of us artists and all of us nourished by art too.

—-

Originally written for Drawing Knowledge (2012). Tracey, The Journal of Drawing and Visualisation Research, Loughborough University.

Revised and republished Miller, A & Strong, J. (eds). (2012) Research-Led and Research-Informed Teaching. CREST Publishing.

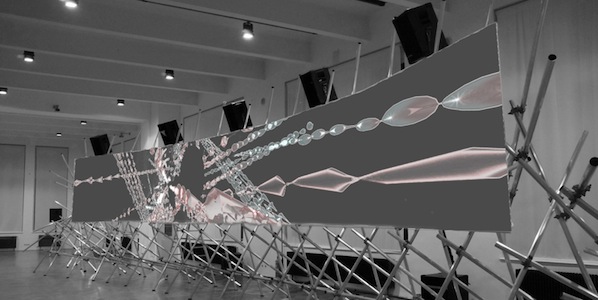

THE CRYSTAL WORLD

The White Building, London

3 August – 30 August 2012

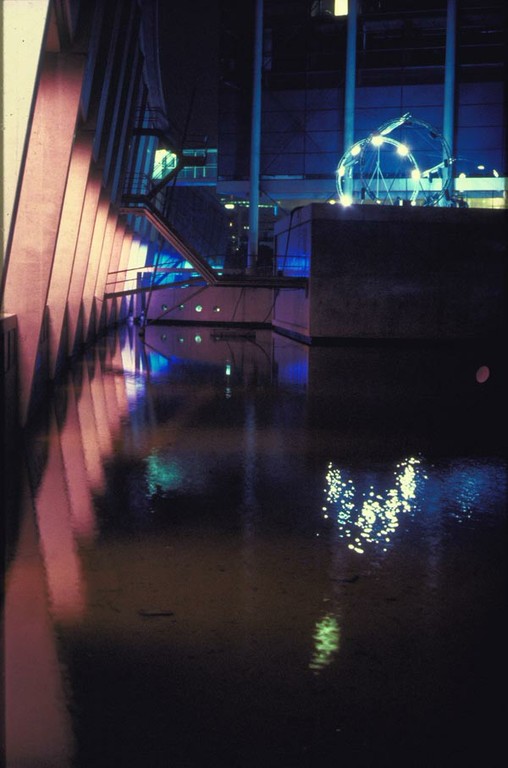

The Space’s White Building cultural centre is within walking distance of the 2012 Olympic stadium in post-industrial, post-regeneration London. As I walked down the steps that lead to it I saw a diesel locomotive pulling a train of cargo containers across an old railway bridge over the canal nearby. Millions of these rational forms will be in transit around the world at any given moment, arranged in two or three dimensions like crystalised capital on trains and docks and ships.

The logistics of their production and distribution are determined by computing machinery using algorithms that operate with inhuman speed and complexity. This same economic logic warps the architecture of the area around The White Building, with old factories and warehouses retro-fitted as office space and as gallery space.

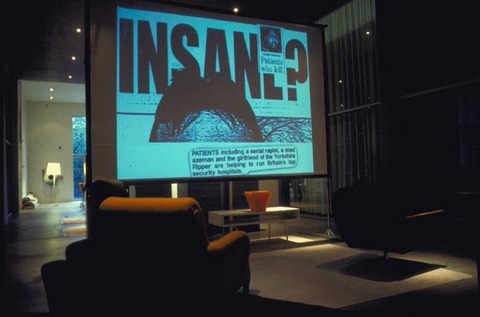

Inside the White Building’s project space the computational enabling technology of the global economy is the subject of a show by Martin Howse, Ryan Jordan and Jonathan Kemp. It takes the title of J. G. Ballard’s novel “The Crystal World” as its starting point. In Ballard’s novel a virus progressively turns all life – vegetable, animal and human – into crystal forms frozen in time. It is a Cold War allegory of the catastrophic imposition of rigid order.

For Howse, Jordan and Kemp these imaginary crystals become the very real minerals refined in the production of the computing machinery used to structure our contemporary world. Inside every digital computer are wires, circuit boards, integrated circuits and other components. They are made from iron, copper, phosphorous, boron, tantalum and other rare earth elements. The central processing unit of a computer keeps time using a quartz crystal. The products of deep geological time are suddenly unearthed and set to pulsating millions of times a second.

Computers are crystal engines. They are mineral fetishes that we use to manipulate powerful unseen forces that we believe we have mastered, like crystal healers working with a patient’s energy grid. But they are so invisibly familiar to us as our smartphones and laptops and their use in logistics and media is so pervasive that it takes an effort for us to perceive their operation or their implications.

It takes almost two tonnes of raw materials to make a desktop PC. Unlike “Tantalum Memorial” (2008), by Harwood, Wright and Yokokoji, “The Crystal World” focuses on these raw materials geologically and temporally rather than geopolitically. But computing waste is toxic and valuable. The former makes disposing of old computers a growing problem, the latter makes recycling old computers a growing business. The minerals that computers contain can be recycled where they are valuable enough, or left to leach into the water supply in e-waste dumps where they are not.

Or in the case of “The Crystal World” an open laboratory and the resultant art installation can re-extract them from their components and printed circuit boards using acid, water, electricity and heat in order to re-crystalise them and return them to geological time. The gleaming silent boxes that organize and mediate our lives are returned if not to the earth from whence they came then at least to their raw materials.

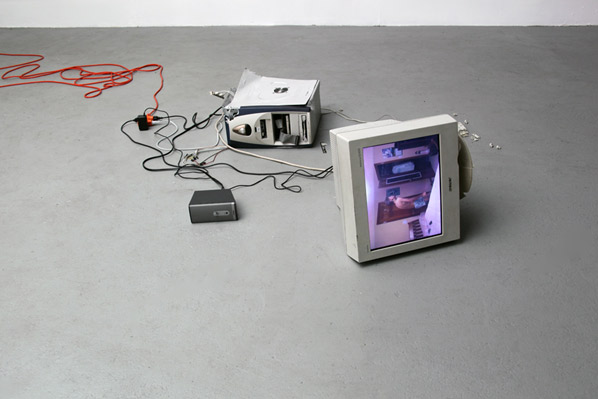

Tables edge the White Building project space, covered with the equipment and results of five days of workshops (and one with books, including Ballard’s, giving any spectators unsure of what is happening a conceptual framework to proceed from). Table after table of crystals, circuit boards, jars, electical equipment, and wires are overwhelming in the details of their appearance and implication. These traces of human activity and inquiry frame the flow of water and electricity in the center of the space, convincing the viewer of the creative intent of its production and drawing them in to its logical universe.

The centre piece of the show is a favela chic water feature that drips acid-loaded water through calcinous rock fragments, over e-waste, into two cut plastic-drum tanks. Next to it an array of smaller plastic containers contain circtuit boards having their copper leeched from them by acid, fungus growing on the by-prodcucts of the project, and other watery deconstructions of computing machinery. It looks dangerous and uncertain, deconstructing both the physicality and the meaning of computers. Seeing the innards of an IBM ThinkPad computer becoming encrusted with calcium like a digital stalagtite, or CPUs branching feathery crystals, returns computing machinery to its raw mineral state. FLOPS give way to eons once more. Neither is a human timescale, yet we must live between them at the moment.

The most fantastical artifact along the walls of the project space is the “Earth Computer”. It’s a battery-like construct of recycled copper and zinc in a tray of silver nitrate attached to lightning conductor-style copper strips. Sitting in earth on a plastic sheet and surrounded by the left-over materials of its creation for the duration of the show, it will be buried nearby afterward. Such a device can function effectively, but not literally. It is more likely to spring to life in the mind of the viewer than if it is struck by lightning. It is effective art, psychic engineering rather than technological cargo culting.

Acid, water and electricity mixed together with e-waste look and feel dangerous. The recycled ad-hoc materials and equipment containing and channeling them reinforce this feel and leaven it with an aura of creative investigation. The form of the show is timeless, the workshop of the alchemist, outsider scientist, or mad inventor. Its content is very contemporary, from Ballard’s rising cultural stock and the social and environmental costs of e-waste to Long Now deep time and posthuman philosophy. Art symbolically resolves the gaps between ideology and reality, and computing is so pervasive and key to society that most people don’t even regard it as ideological never mind conceptualise its failings as such.

The water and abandoned human artefacts of some of the installations is more “Drowned World” than “Crystal World”, and the broken machinery is more “Crash”. Ballard’s catastrophes provide a modern mythology that is a more useful resource for art than its literary roots might suggest. It achieves the defamiliarising and critical impact of hauntological art without requiring its supernaturalism or nostalgia. There is a Ballardian attitude at play here.

I found “The Crystal World” mind-blowing. It relates the tools of our human existence to non-human substances and timescales, providing the kind of corrective to anthropocentric vanity that object-oriented philosophy aspires to. It achieves this profound insight and presents it in an accessible way precisely because of the modesty of its materials and aesthetics, and because of the resonances of the cultural materials chosen as its starting point.

http://spacestudios.org.uk/whats-on/events/the-crystal-world-open-laboratory-exhibition-

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Dual

Nottingham Playhouse

5 September – 30 October

After a glorious false start in the 1990s, the previously over-hyped technologies of virtual reality have been quietly reclaimed in a more sustainable and democratic way through Free Software and Open Source hardware. The show “Dual” at Nottingham Playhouse showcases art that mostly uses these new technologies. A theatre is the perfect setting for the reality play of virtual reality. Curatorial collective The Cutting Room (Clare Harris and Jennifer Ross) have organized the funding, production, and presentation of artworks that mix the virtual and the real in creative ways.

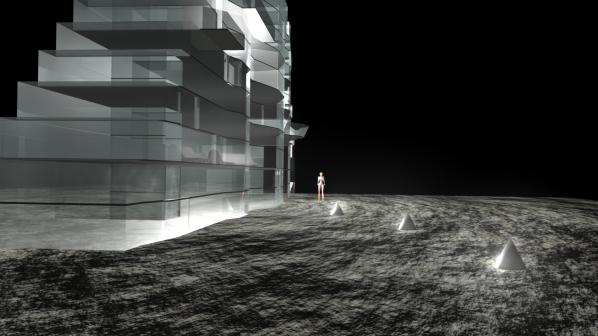

Michael Takeo Magruder’s “Deconstructed Metaverse” (with Drew Baker and Erik Fleming), 2012, is installed on the upper landing of the theatre. The windows on the landing have been glazed with images of warmly coloured softly undulating colours. On closer inspection they are pixellated and have endless lines of computer code superimposed over them in small white type. The code is XML representing a virtual world, and that virtual world can be seen and interacted with on monitors in front of the windows. They display a ceiling-less ultra-modern rotunda with windows glazed in images of the views that could originally be seen through the real windows that are now glazed with images of the site-specific virtual world.

The first, smaller, monitor sits on a plinth alongside the circuit board that runs the virtual world using OpenSim under GNU/Linux from a single USB memory stick. You can use a keypad to explore the world, your presence there represented by a generic default human avatar that walks and flies around the island. Or you can visit the virtual world over the Internet. In either case, a large screen further along shows a rotating view of the island, its architecture and inhabitant(s).

Magruder has worked with virtual environments since the VRML era, and “Deconstructed Metaverse” continues some recurring themes while bringing them to a new level. There are multiple layers of reality and presence to this work that the viewer can find themselves looking into and out from, relating to other onlookers as part of the audience or part of a performance in the virtual world themselves.

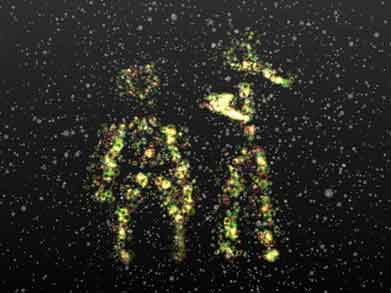

Brendan Oliver’s “Particulation” uses a Microsoft Kinect to capture the poses and motion of pairs of patrons walking through the Playhouse’s ground floor bar. A laser-scanning motion tracker and the software to process its input would have been unobtainable for most artists a decade ago. Oliver makes good use of hardware that was liberated against the wishes of its manufacturers and of software frameworks that are shared more freely.

Oliver uses them to capture and evoke the movements of two people who may not realise that they are the inspiration for the visual art on the wall. They are translated into a particle system of bubbling circles of light projected just far enough away from the sensor that monitors them that the connection between captured movement and animated image is not immediately obvious from all angles. Particulation has the feeling of joyous discovery and exploration that the best interactive multimedia art can bring to a space.

Below ground, “Mirror On The Screen” by Charlotte Gould and Paul Sermon uses similar technology to Deconstructed Metaverse to create a pocket universe of symbolic scenery and objects from children’s stories. In order see the screen presenting the virtual world and use the keypad to move your avatar around it you must stand in front of a printed backdrop where you are watched by a webcam. The resulting video stream is fed into the virtual world and superimposed onto cracks in its reality.

In addition to seeking the highest place in the forest, the edges of the world, and all the objects and characters within it, you find yourself hunting your own reflection. The tables are turned as the avatar you are watching starts watching you, and your purpose becomes seeking out further reflections. The setting of the theatre puts the viewer in a frame of mind open to the drama of the virtual world and its looping back on reality. Far from jolting you out of the experience, suddenly being faced with your own image in the virtual world draws you in further.

Finally, Kim Stewart’s “Sigma 6” is a 3D computer animated film set in a dystopian high modernist moonbase-like environment of harsh architecture and harsher treatment. The virtual world-like quality of the animation, and the avatar-like quality of its persecuted protagonist have their reality punctured in a way that continues the theme of mixed realities in a way that turns towards body horror.

These common themes of blurring virtual environments with real bodies and places allow the works to complement and distinguish themselves from each other artistically and technically. The Cutting Room are to be applauded for assembling such a thematically tight and technologically competent show that both serves and is served so well by the context of the institution that it is staged in.

http://www.nottinghamplayhouse.co.uk/about-us/the-cutting-room/

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

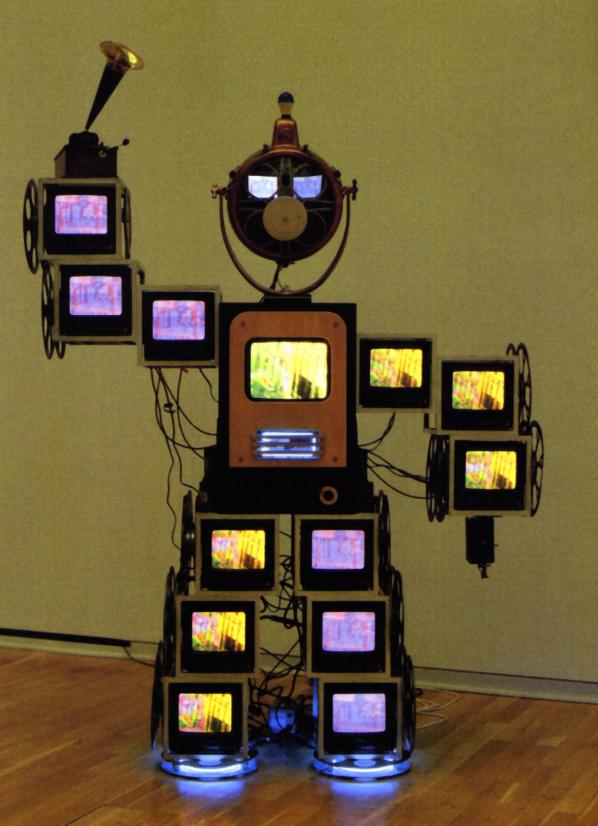

The activist initiatives of this art group from Vienna seem fascinating due to its art-tech philosophy, and it puts a smile on my face due to its pop attitude. In May 2011, Günther Friesinger, one of the creators of monochrom, gave a lecture to Media Art Histories students of the Donau Universität, which inspired me to arrange an interview with him. The first question I asked was about establishing monochrom. Günther explained that “monochrom came into being in 1993 as a fanzine for cyberculture, science, theory, cultural studies and the archaeology of pop culture in everyday life. Its collage format is reminiscent of both the early DIY fanzines of the punk and new wave underground and the art books of figures such as Dieter Roth, Martin Kippenberger and others. For a while now, monochrom has been venturing further than publishing alone and has been responsibly influencing people’s minds via film production, performances and festivals. If you are in Vienna in autumn by chance, look at the paraflows festival – one of the main projects run by monochrom.

Natascha Fuchs: How much has monochrom’s aims changed since 1993?

Günther Friesinger: We didn’t really develop a concept back then; monochrom has evolved. In the beginning, there was only the idea of publishing a fanzine – lots of other things resulted from that. At some point, we started doing performances. In the Internet’s primordial age, we developed a robot that could be controlled via the web, and so we began entering the art scene. Our first exhibition was in 1998 in the Secession, Vienna. Unfortunately, they didn’t have Internet access back then, so our little robot stood in a corner, immobile. The people visiting the exhibition back then still considered it interesting enough to some extent, but many things back then didn’t work the way we’d have liked them to work.

NF: Art, technology and philosophy – are they equal for monochrom? What is the starting point for monochrom’s particular initiatives?

GF: We are a political group that gives statements through different means, those of art in all its varieties. I think it is important for us to find a fitting medium for the right story. This is something that specifically characterises us as a group. There are many different actions implicated by that, such as writing plays, making a movie, producing a music CD or writing a book. Normally, people try to achieve excellence in one medium. With us, it’s the other way round. That’s why we’re active in so many different areas.

NF: Which historical background concerning the relationship of philosophy, art and technology is especially meaningful for you?

GF: A difficult question. I think that Guy Debord and the Situationists are those one could consider most fitting. Certainly also some parts of Fluxus are of relevance.

NF: To which media theoreticians do you refer in your practice?

GF: I think that as a theorist, artist and curator in media art, net art, digital art and culture, it is important to confront oneself with theorists like Kittler, Luhmann, Flusser, McLuhan, Rheingold and many more. However, it is not the case that we refer to one theorist or another in all our works. I think that this system of self-affirmation through referral is quite interesting – but I think that for myself, monochrom and for our audience, there is a value added by self-generated theories for our projects and the discourses they cause.

NF: What are international projects of monochrom? And what is the difference between monochrom audiences in Vienna and abroad?

GF: There are too many of those to be listed here. Since our big USA tour of 2005 we produce most of our projects bilingually in German and English, or only in English, in order to be able to have an international impact. Of course, many members of monchrom live and work in Vienna, and we also produce projects in Vienna, but our main focus is on our international presence. One of the big international projects, running since 2007 in San Francisco, is the Arse Elektronika: a conference on pornography, sci-fi, games and the development of technology. I would say that with the San Franciscans we’ve found the ideal community for such a conference.

NF: You call yourself “edu-hacker”. Why that and how is it connected with your studying and teaching experience?

GF: I have always loved reading, learning and continuing to further myself intellectually. I really enjoyed my studies and I enjoy sharing my knowledge and skills with my students. Universities are, in my book, places where it is possible to acquire knowledge, to reflect upon it, places of discussion and freedom. Because of the process of universities becoming more like schools, among other things caused by the Bologna Accords, those in my opinion are important areas that enable students to become self-reliant, critical people are struck from the curriculum. I’m trying to counteract this in my classes, trying to cause rifts in the school-like system, by using other methods of transmitting knowledge, using a great deal of humorous elements, and by always meeting the students eye to eye as equals.

NF: What is philosophical society in contemporary Austria now?

GF: Alive and kicking as always, I’d say 😉 One of the exciting things is that exactly now there are a lot of young, fascinating philosophers out there. The topics that I mostly concern myself with are, however, copyright, intellectual property, culture, art, media and technology.

NF: Is paraflows one of your biggest current projects? What’s the concept of this festival? Is it independent from monochrom activities?

GF: paraflows is surely one of the biggest projects that I am working on at the moment, apart from monochrom. monochrom helped to start and grow the festival in the first two years, as monochrom has done with many other projects worldwide. „paraflows – festival for digital art and culture“ has been established in the last seven years as a new annual festival situated between the Ars Elektronika and the Steirischer Herbst. It serves as both a platform for the young, local scene of digital art and culture and as an interface to international and renowned media art.

NF: How is monochrom activity is financed?

GF: We do get occasional subsidies for some projects, we get money from performances, the sale of our publications and sometimes the sale of a work of art, and recently we have also acquired crowdfunding. I’d say, however, that around 80% of the projects we do are not financed in any way and are purely done because we have fun doing them.

NF: Do your own curatorial projects serve in some way as a research method for you?

GF: I take the liberty that I only curate projects that I am very interested in myself. That is to say, projects where I have a very strong urge to explore the topic, to read, write and of course also to do research. That is probably the reason why I try to achieve a publication for each project that I curate, in order to give those who are interested in it some sort of preliminary report, a possibility to expand upon.

NF: Is activism capable to envision the future or does it just reflect, react on what is and has happened?

GF: It is getting increasingly difficult to be subversive. monochrom is fundamentally critical of the bourgeois world view. We examine it from a distance, dissociating ourselves from it. The question is: How do we get out? Our current late-capitalist aims for transgressions. That is to say that capitalism requires transgressions as a principle. Viennese Actionism, the most relevant cultural statement in Austria for the last hundred years, was doomed to fail at a certain point, because in the 60ies Austria still had a society based on discipline. One of the central strong points of monochrom: Finding the right story for the right medium could be a opportunity to deal with this situaltion.

NF: Which publications about monochrom you would recommend to read?

monochrom’s ISS. In space no one can hear you complain about your job. (2012)

monochrom’s Zeigerpointer. The wonderful world of absence (2011)

Urban Hacking. Cultural Jamming Strategies in the Risky Spaces of Modernity (2011)

monochrom #26-34: Ye Olde Self-Referentiality (2010)

Do Androids Sleep with Electric Sheep? (2009)

Pr0nnovation?: Pornography and Technological Innovation (2008)

monochrom: www.monochrom.at

paraflows festival: www.paraflows.at

(c) Natascha Fuchs is an independent expert in cultural projects management and international public relations, graduate of the University of Manchester (Cultural Management) in 2008. She has been living in Vienna, Austria, studying History of Media Arts at the Donau-Universität and collaborating with sound:frame Festival for audio:visual expressions, since her move from Moscow, Russia in 2011. In Russia she was related to MediaArtLab and Media Forum — the special program of the Moscow International Film festival dedicated to media arts, experimental films and digital context with more than 10 years history. As a researcher and practitioner, she works in a variety of topics and participates in different international projects focused on media arts, cinema and sound. Columnist and writer for several online magazines.

12 Remixes, by Michael Szpakowski

From August 2011 to July 2012, the video artist and musician Michael Szpakowski entered a remix competition every month, and compiled his remixes (some of them with accompanying videos) on his website. “I’m 54 years old,” he explained at the beginning of the project, “and although I’m musically reasonably deft I know little about the culture in which I’m attempting to intervene. I know none of the specialised vocabulary, can’t distinguish genres and although I understand what is being said, just about, I don’t speak the language in which posts or comments on this kind of work are framed.” The project, in other words, was a deliberate step outside his “comfort zone”.

The results are often startling. It’s worth comparing the remixes with the original tracks from which they derive, because it provides some insight into Szpakowski’s working methods, and makes you realise the extent of some of the transformations he has achieved.

One of the most striking examples is the remix of “Sandwiches” by the Detroit Grand Pubahs. The original track is a grotesquely overstated hyper-lecherous rap. A synthesised-drum-and-bass arrangement underpins a chipmunk-style speeded-up vocal, warbling lyrics of such obvious symbolism that they hardly qualify as suggestive: “I know you wanna do it/You know I wanna do it too/Out here on the danceflo’/We can make sandwiches…/You can be the bun/And I’ll be the burger, girl…/Make your thighs like butter: easily spread…” The effect is quirky, irritating and compulsive; tongue-in-cheek, deliberately outrageous, blatantly sexist and borderline pervy all at the same time.

Szpakowski’s remix has an entirely different feel. The vocals have been slowed right down from warbly chipmunk to entombed Darth Vader; correspondingly, the bassline has slowed too, from a prefabricated booty-shaker to something subterranean and slightly menacing; and in the space above there are echoey keyboard-notes floating and pulsing like luminous jellyfish. The effect of the lyrics is no longer leeringly voracious, but mournful, obsessive and introspective. There is an instrumental coda with a vaguely Scottish Highlands flavour to it. The feel of the track has changed completely, and so have its texture and geometry. We find ourselves in a darker, much larger space.

Another good example is “OK good stand clear”, based on “110%” by Laura Vane and the Vipertones. The original song is efficient, well-assembled funk/soul, complete with a punchy horn section and a sassy female lead vocal. It’s slick, sharp and professional, but hard-working rather than inspired. Szpakowski’s remix dispenses with almost everything except the rhythm section, which is slowed down slightly to give it more depth and a thumping creaky quality like an elephant in new walking-boots. To this he adds a sampled American voice saying “OK? Good” and “Stand clear of the closing doors!”, and a hammering piano-figure. Again the effect is to open the track out, to give it a more three-dimensional feel, and also to make it much less derivative, much less obviously the product of a particular genre.

In almost every instance Szpakowski’s remixes have a more resonant and spacious feel than the originals; the sounds are dirtier, fuzzier, more textured; and the rhythms are more complex. These changes may not always be entirely to his advantage. As he admits himself, “I don’t dance (or haven’t for twenty years or so), which actually makes a big difference in how one experiences popular music…” Certainly there is one track – a remix of “Paradisco” by Charlotte Gainsbourg and Beck – where Szpakowski’s version has a spiky, angular, echoey jazz feel, but loses out to the original in terms of finger-clicking compulsiveness. It’s true that his remix puts a stronger focus on Gainsbourg’s voice and lyrics than does the original; but whereas Gainsbourg and Beck’s version stays within the disco format and gives it an iconoclastic indie makeover, Szpakowski’s remix takes us beyond that format altogether, and comments on it from the outside.

In some of the tracks there is a move from the USA to Europe in terms of feel. One example is the remix of “What happens in Vegas” by Chuckie ft. Gregor Salto – a histrionic slab of USA club music. Szpakowki’s version (“Shit happens in Vegas”) has a distinctly Kraftwerk-esque, European-techno slant. Also, because the remixes are often crackly, fizzy and hissy, they tend to feel “older” than the originals. At times we seem to be listening to badly-tuned radios in the pre-digital era, or to vinyl LPs smothered in dirt and played through a fluff-laden needle. But this “distressed finish” effect is in keeping with a broader sense that Szpakowki’s remixing technique involves a kind of deconstruction or breaking-apart of the tracks on which he is working. They become less smooth and shiny, less self-contained. The original tracks are often tightly-focussed in terms of their musical styles, with a narrow range of subject-matter, and often with manipulative designs on the audience – wanting to make them feel like dancing, wanting to make them feel sexed-up, or trying to tug at their heart-strings (“Try to Stay Awake” by Frank Friend, “Trojans” by Atlas Genius and “Jigsaw” by Mimi Page are all relationship-based heartstring-tuggers). The remixes, on the other hand, aren’t looking for such straightforward reactions. Their subject-matter is less easy to pin down, and their ingredients bespeak a mixing-together of disparate materials, different cultures, and even different eras.

Non-musical ingredients are one noteworthy feature. In “OK good stand clear”, the voice saying “Stand clear of the closing doors!” comes, as Szpakowki explains, from “New York subway recorded announcements… grabbed, I think, from YouTube”. He is also fond of introducing a voice intoning random numbers – this occurs in several of the tracks. Usually the voice has a foreign accent, and sometimes the numbers are spoken in a foreign language. These number-sequences, says Szpakowski, come from “the so called ‘numbers stations’ which are believed to have been used by various intelligence agencies… they’re available at the internet archive“.

On “I’m getting a cat” the words come from mashed-up Tweets which have been run through a voice-to-text synthesiser. “I am that I am” borrows its vocal from the painter and sound poet Brion Gysin – a voice-sample which, until it begins to distort, sounds rather like a 1950s announcement on the BBC. “Speaking in Tongues” reverses the vocal on a hectoring soul track by Colonel Red called “Rain a Fall”, so that it ends up sounding as if it’s in some unspecified European or possibly Middle Eastern language. And “Sugar Plum Fairy on the Dancefloor” introduces the chiming melody from Tchaikovsky’s Sugar Plum Fairy into a rap called “Disco Technic” by Stan Smith, to surprisingly good effect. There is a genre-busting transgression of boundaries, a throwing-together of cultures, a jumbling-up of eras, and a deliberate use of incongruous material.

The videos Szpakowski has produced to accompany some of these tracks show similar traits. Again his admission that he doesn’t dance is relevant here, because the starting-point for many music videos – a very tight and emphatic synchronisation of visual effects with the beat of the track – is not a particularly dominant feature in his work. The one which succeeds best in this respect is the video for “OK good stand clear”, which projects text versions of the words onto the screen in big letters precisely as we hear them. There is also a lovely moment in the video for “I’m getting a cat” where, in a bit of old black-and-white footage, some youngsters sitting on chairs on a stage start to sway from side to side, apparently in time to the music.

But synchronisation to the beat isn’t Szpakowski’s priority. “I’m getting a cat” provides a good example of the kind of effect he achieves instead. The synthesised vocal for the track first announces that it’s getting a cat, then starts to ask absurd questions about cats and cat-care – “Does your cat try to style your hair?”; “What is your funniest and yet painful cat story?” – which are gradually infiltrated, first by other subject-matter – “Become a big brand on Facebook!” – then by symbols – “Poundsign poundsign poundsign” – and sequences of numbers. What starts off as funny, ironic and nostalgic develops or breaks down into a kind of digital fragmentation, and eventually into wordlessness. The end of the track is a wistful instrumental coda, embellished with piano and strings. And the video follows much the same path. It starts with old footage from the 1960s White House, in which President Lyndon B Johnson seems to be announcing his intention to get a cat to his slightly-bemused aides. Then there are some outtakes from what seems to be an instructional video in which a troubled youngster is being given helpful advice (presumably cat-care advice) by a reassuring and helpful older man. By the end of the track – the coda – we are watching teenagers playing music, drinking coffee and dancing. Again, humour and irony have been replaced by something more wistful and hard-to-define.

“Found” materials, often quite disparate materials spliced together by digital means, are just as important to the videos as they are to the remixes: they feature archive footage of the Whitehouse; shots of groovy teenagers from the Fifties or Sixties; Japanese Noh theatre; imagery based on Little Red Riding-Hood; square-dancing American kids; old claymation footage of teeth wearing boxing gloves; big black lettering; jumbles of coloured pixels; and images of Las Vegas captured from Google Maps, reconstituted into a long sun-baked backwards drive from the middle of town into the desert. Like the musical tracks they accompany, these videos cull their materials from many disparate places; they are full of little jolts of incongruity, slightly-bizarre juxtapositions; they lead us not only inwards towards the music but outwards towards different cultures and different eras; and they also call our attention to the digital medium itself, the Web on which all these materials are available, and the computer software which slices and splices them.

Perhaps most remix artists are more influenced by the work of their immediate peers than by art theory, art history, or inspiration drawn from other cultures. Not so with Szpakowski. As mentioned before, one of these remixes (“I am that I am”) uses a vocal track from Brion Gysin; and the words “OK good”, from “OK good stand clear”, are sampled from a recorded talk by William Burroughs. Burroughs and Gysin were the first proponents of cut-up and fold-up techniques in literature: Gysin was also an experimental painter and sound artist. This link with the two of them hints at a connection between Szpakowki’s remix style and modernist or post-modernist art. Remix culture itself is closely related to mash-ups, which in turn (whether remix artists are aware of it or not) can trace their ancestry not only to cut-ups and fold-ups but to the collages, bricolage, decalcomania and other mixed-media, mixed-genre experiments of the Modernists: experiments which reflected not only an urge on the part of Modernist artists to break free from received genres and formal conventions, but a feeling that the modern mind did not belong to a single era, a single unified body of belief or a single point of view – instead it contained many disparate perspectives, and ideas or images from many different eras and cultures, all thrown together into a jumble. For the modernists, this jumble was itself both one of the joys and one of the symptoms of modernity.

For modernist and post-modernist artists, formal perfection is often a secondary consideration, compared with the excitement of putting things together in new ways, seeing things from new angles. T S Eliot (in “Tradition and the Individual Talent”) described the mind of the artist as a “medium…in which special, or very varied, feelings are at liberty to enter into new combinations”. He made the same point in “The Metaphysical Poets”: the artist, he argues, “is constantly amalagamating disparate experience”; and modern art is bound to be more complicated than the art of earlier centuries, because modern life itself has become more complicated: “Our civilization comprehends great variety and complexity, and this variety and complexity… must produce various and complex results.” It was also argued, by various theorists, that modern artists found it increasingly difficult to belong wholeheartedly to a particular tradition, or to stick to a particular working method or lexicon of forms, because mass reproduction had made so many different traditions and examples, from so many different eras and cultures, available to them. If these observations were true at the beginning of the twentieth century, they are most certainly true now, at the beginning of the twenty-first, when life is characterised not just by “variety and complexity”, but by information-overload, and when the work of other artists, other eras and other traditions is available not only in museums, libraries, books and prints, but online at the click of a mouse or the blink of a Google query-screen. So one way of understanding Szpakowski’s remixes – his particular take on what a remix ought to be like – is to look at them in the light of modernist, post-modernist and digital-modernist aesthetics.

Another neo-modernist aspect of these remixes is their reluctance to woo the audience. There are moments when the arrangements are slightly unsympathetic to the listener. One example of this is “I’m getting a cat”, where the voice-over stops asking absurd questions about cat-care and starts coming out with fragmentary nonsense about Facebook, number-sequences, and “poundsign poundsign poundsign” instead. The “poundsign poundsign poundsign” sequence, in particular, goes on to a point where a lot of listeners might find themselves wishing it would stop. Similarly, on “I am that I am”, the voice-over, which starts with a sequence of variations on the theme of identity –

I AM THAT I AM

AM I THAT I AM

I THAT AM I AM

THAT I AM I AM

AM THAT I I AM

– soon gets speeded-up and distorted into an incomprehensible babble, and this babble is so loud and frenetic that it’s quite hard to hear the music. Again, some listeners may find themselves wishing that the voice-over would stop.

As already mentioned, the vocal track in “I am that I am” is based on an original piece by Brion Gysin, and Szpakowski has actually cut it down in order to re-use it – so although Szpakowski’s track may seem a little bit tough on the audience, it’s actually quite a bit less demanding than Gysin’s original. But the link with Gysin provides a clue to the aesthetics which are apparent throughout the whole “12 Remixes” project. “I am that I am”, as a text, is based on the idea of reordering a five-word line into all its possible variations, as can be seen from the extract above. As such, it has a mathematical quality. It resembles “ordinary” poetry in the same way that a peal of bells resembles “ordinary” music, and its structure and length are determined, not by any particular ideas about what may sound good to an audience, or what may provoke a certain emotional effect, but by the need to run through all the possible variations of a certain sequence in a certain order.

As a sound-poem the piece progresses in a similar way: Gysin takes his sequence of statements, and gradually adds echo to them and speeds them up until they become a frenzied babbling noise. In other words he performs a set of mechanical distortions on them, and increases or redoubles those distortions until they have reached a logical conclusion. Again, he is not particularly thinking about what will grip, entertain or move his audience: his attention is fixed on the materials, the medium and the process. This is not to say that “I am that I am” does not have any affect. It is delivered in the ringing tones of a self-important orator, and when the first layer of echo is added we imagine that the speaker might be addressing a rally in a great hall, like Citizen Kane, Mussolini or Hitler. But the self-assertion of the words is then turned into nonsense as the layers of distortion pile up. We feel firstly that great leaders and orators and being mocked, and then that identity itself is being called into question. But we also feel, as listeners, that these reactions may belong to us at least as much as to the piece itself: it has not been designed primarily with the purpose of producing them, and if we failed to experience them the piece would still have a purpose and meaning of its own beyond them, as a peal of bells has its own purpose and meaning whether we enjoy the sound of it or not.

This concern with sequence and process, with breaking things down into their constituent elements and then reorganising those elements according to mathematical rules, can again be related to the experiments of modernism – to the modernists’ determination to question and rearrange the materials and media from which works of art are made – but as the example of the peal of bells indicates, it can also be linked to much older forms of art; and at the same time it has a particular relevance for artists who are working with computers and code. Five words being reorganised into every possible sequence will produce a flicker of recognition in anyone who has every attempted code-poetry. It’s the kind of experiment which sits very naturally in the digital environment and the new media art genre.

Szpakowski’s remixes cannot be described as mathematical sequences or coded music, but they certainly do show evidence of a Gysin-like interest in variations and logical progressions. This may make them seem a bit unsympathetic in places, but it also gives them a certain air of toughness and detachment. As already mentioned, if they are compared with the original tracks on which they are based, one difference to emerge is that they don’t seem to have such obvious designs on their audience. But it’s also true that they don’t tend to follow such obvious paths in terms of musical development. If we look at “In Paradiscos”, for example, the original track has a very strong feeling of moving up a gear when it comes to the chorus, whereas Szpakowski’s remix doesn’t follow the same pattern. Another example is “the moon is inside the snow”, a remix of “Blindsided” by Luke Leighfield and Jose Vanders (which is itself a cover of an original track by Bon Iver). In Leighfield and Vanders’ version, there is a definite sense of drama and progression, as the female vocal is joined by piano and violin, and then by a male voice singing in harmony. By the end of the song, we feel that we have been taken on an emotional journey. It has a narrative arc. Szpakowski, on the other hand, dispenses with the male harmony altogether, and also with large sections of the song’s lyrics. He cuts up and rearranges snippets of the female vocal to create quite a different impression – more of a Haiku than a romantic poem – and he alternates the original vocal with a second female voice talking in Japanese. The end result is just as beautiful as the track on which it is based, but in a quite different way. It’s more austere and contemplative, less narrative and dramatic. It seems to be less about recounting a personal experience, and more about organising disparate elements into an aesthetically satisfying pattern.

Modernism, cut-up techniques, digital experimentation – perhaps these are big perspectives from which to view what is essentially a fairly modest project. Szpakowski didn’t set out on this series with any particularly grandiose ambitions: he set himself the task of producing one remix a month for a year because he thought it would be something interesting to do: it would build on his strengths as a musician and technophile, but it would also set him a series of new challenges. As it turns out, he has risen to those challenges to great effect and produced something really special – a collection which shows variety of tone and pace, wit and inventiveness, along with unity of design and a distinctive “voice”. Whether it’s a digital-modernist take on remix culture or not, anybody who is interested in experimental music could do a lot worse than put their headphones on and give it a try. It certainly repays close attention.

Featured image: Jon Satrom (left) and jonCates at Intuit, Sept. 20, 2012 (right). image: Shawne Michaelain Holloway

Post-Static: Realtime Performances by jonCates and Jon Satrom @ Intuit, the Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art (Chicago). September 20, 2012. Programmed by Christy LeMaster

“Alchemy; the science of understanding the structure of matter, breaking it down, then reconstructing it as something else. It can even make gold from lead. But Alchemy is a science, so it must follow the natural laws: To create, something of equal value must be lost. This is the principle of Equivalent Exchange. But on that night, I learned the value of some things can’t be measured on a simple scale.”[1]

In 1966, Bell Laboratories scientists and engineers collaborated with artists to construct several performance-based installations under the title 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering. Works included Variations VII by John Cage and performance engineer Cecil Coker, in which a sound system pulled sounds from radio, telephone lines, microphones and musical instruments, and Carriage Discreteness by Yvonne Rainer and performance engineer Per Biorn, a dance event controlled by walkie-talkie and TEEM (theatre electronic environment modular system). Critic Lucy Lippard was wrote that the event was filled with technical problems and that the artists involved allowed the technology to take precedence over the art. She pointed out that no theatre people took part in the event and suggested that while this event did not offer a specific design for a new approach to theatre, it revealed the possibility that new approaches to theatre might be born from the combination of art and technology:

A new theater might well begin as a non-verbal phenomenon and work back towards words from a different angle. Departing from Samuel Beckett’s highly verbal, single-image emphasis, it could move into an area of perceptual experience alone, its tools a more primitive use of sight and non-linguistic sound. Such a theater would not necessarily be the amorphous carnival of psychedelic fame but could be as rigorously controlled as any other.[2]

She also observed that it was often impossible to understand the relationship between the technology and the events it triggered without reading the program, mentioning one such missed connection in Open Score, by Robert Rauschenberg and performance engineer Jim McGee. In this piece, tennis rackets were wired such that each impact of the ball on a racket turned off one light in the performance hall. Lippard wrote that this connection was not noticeable and thus the conceptual framework of the piece was lost to the audience.