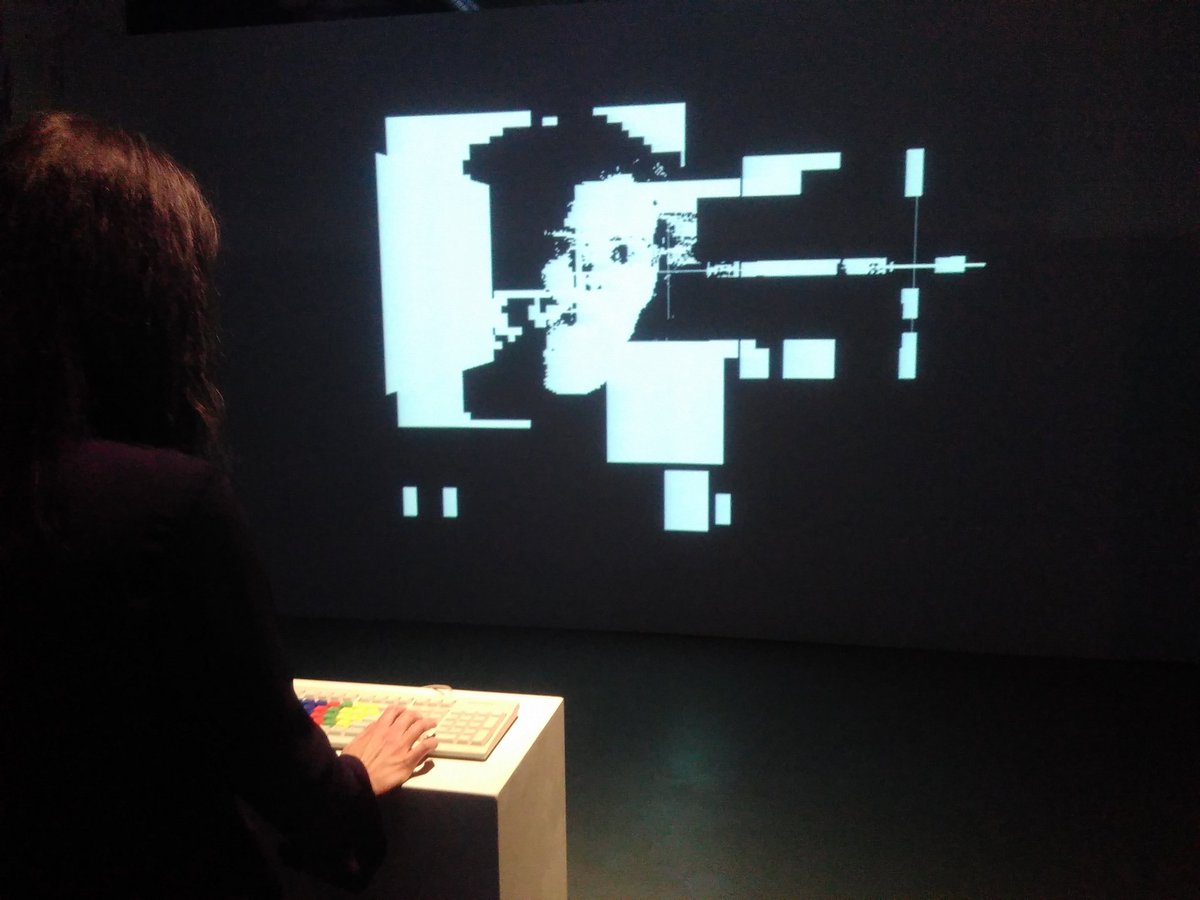

Featured Image: Olia Lialina, My Boyfriend Came Back From The War, at MU. Photo Boudewijn Bollmann

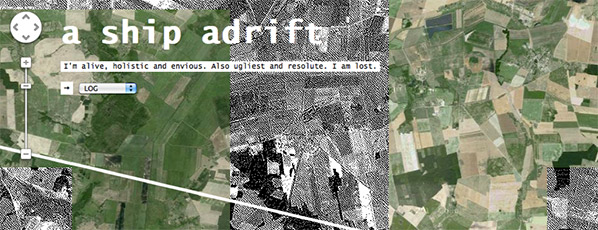

Twenty years ago, in 1996, Russian artist Olia Lialina created My Boyfriend Came Back From The War (MBCBFTW). Using the story of a veteran’s girlfriend who has mixed feelings when he returns, the interactive Web narrative quickly became an iconic work that inspired many artists to create their own interpretations of it. At the moment two exhibitions at HEK in Basel and MU in Eidhoven, pay hommage to MBCBFTW, a tribute to a medium and a new approach to keeping history alive.

Participating artists

Inbal Shirin Anlen, Freya Birren (Jennifer Walshe), Vadim Epstein, Dragan Espenschied, JODI, Olia Lialina, Abe Linkoln, Guthrie Lonergan, Armin Medosch, Ignacio Nieto, Anna Russett, Tale of Tales a.k.a. Entropy8Zuper!, Mark Wirblich. With two new works by Constant Dullaart and Foundland (commissioned by MU).

Educated as a journalist and film critic, and curating experimental film programmes in Moscow, in the mid-1990s Olia Lialina quickly embraced the Web and started experimenting with its unique qualities. She made her first net art piece, My Boyfriend Came Back From The War in 1996. Four years later she set up the Last Real Net Art Museum – an initiative to oppose museums that were presenting the first ‘Internet art exhibitions’, and a place on the Web where she could collect and exhibit the projects that responded to MBCBFTW. Ten years after she made her first net artwork, in 2006, in their popular book New Media Art (Taschen) Mark Tribe and Reena Jana wrote about MBCFTW: ‘One indicator of the historical significance of Olia Lialina’s 1996 Net art project, My Boyfriend Came Back From the War, is the numerous times it has been appropriated and remixed by other New Media artists. (…) Perhaps it resonates with other artists because it is among the earliest works of New Media art to produce the kind of compelling and emotionally powerful experience that we have come to expect from older, more established media, particularly film.’

In the meantime, Lialina had moved on and in addition to her online art practice, wrote about new media, Digital Folklore, the vernacular Web, co-founded the Geocities Research Institute, and became an animated GIF model and a professor at Merz Academy in Stuttgart, whilst the ‘mini-drama in hypertext’ MBCBFTW continued to be of interest to many artists, curators and critics. For its fifteenth anniversary, The Creators Project described MBCBFTW as a ‘charmingly simple yet poignant work’, emphasising its importance for the history of net art and its longevity through its interpretations. At the moment, as Lialina tells me, the project is discussed on Twine – an open source tool for telling interactive, nonlinear stories – where people communicate with each other about this ‘early Twine’. It is therefore not surprising that 2016 starts with two anniversary exhibitions, opening almost at the same time but in different frames, of My Boyfriend Came Back From The War. online since 1996. In what follows I asked Olia Lialina to reflect on the lasting popularity of the work, her intentions for making it, and her ideas about ways to go forward with it.

Can you tell me something about your background, how did you end up being an artist and a professor?

Twenty years ago I was absolutely happy with what I did: writing about films, curating film programmes, trying to make my own films. But as with many who embrace the World Wide Web (or were embraced by it) when it left academia in the mid-1990s – I was lucky to have a sudden new life and career. I became an artist only because MBCBFTW became a piece of net art. And I could become a professor four years later because of it 🙂

Could you briefly describe what the work is about?

In my teens I came up with the sentence ‘My boyfriend came back from the war, after dinner they left us alone.’

Мой парень вернулся с войны

И вот мы остались одни

And I always wanted to complete it as a poem, but the next lines never came. Years later, still confused about the phrase, I made it into an ambivalent dialogue with the browser: dividing it into frames. It was never about a war, but about a difficult conversation that doesn’t lead anywhere, and of course about the browser. I wanted to make something that people would spend time with and look at in the browser. This was also possible back then because the connection was much slower – so it took time to go through it. This has changed a lot now: HTML adapts to faster speeds, and most of us aren’t used to waiting – or loading time – anymore. You cannot click slowly if something is fast. That is also why we artificially slowed down the Internet connection for the exhibition.

When you started working on the Web, you came from a background in journalism and film. What sparked your interest in HTML frames?

They were very new at the time, not every browser supported them and you had to install the Netscape 3 version that had just been released – although in specifications I see now that it also worked in Netscape 2, but I remember that it didn’t back then. So, at the time it was cutting-edge technology – even though there was already a ‘I-hate-frames’ movement on the net, which I only discovered later. For me, it was interesting to see that a browser window could be divided up: you could assign coordinates, partition the screen and have multiple HTML documents within the same window. It sounds naive now, but at the time it was very empowering: I felt like a hacker, I could decide what it looked like and how it functioned.

And it reminded me of celluloid. I used to work with experimental 16mm film: cutting and pasting frames together. The editing was a way to work with the material, not just a concept. So, the connection between film and browser frames was something exciting. At the time I always talked about MBCBFTW as a net film. Someone more familiar with CD-ROM art, programming or interactive art would probably see it differently, but for me using frames inside the browser was a way to edit – it was a direct transition from being a filmmaker to a net artist.

While preparing the inventory table with all the elements of MBCBFW for the exhibition and reviewing the HTML code, I saw so many mistakes that I felt a bit ashamed. Mona Ulrich, one of my students, and I noticed warning after warning while reading through the code. So, it’s not only an old code, it is also very buggy, but despite all that it still works! That is the great thing about HTML, it has a very high tolerance, and it’s very forgiving if you write ‘bad’ code. It allows you to make mistakes: it’s not even that it was easy to learn, but rather that you didn’t really have to learn it at all.

In 2000 you started the Last Real Net Art Museum, as an initiative to collect and present interpretations of MBCBFTW. Could you explain the context and purpose of the Last Real Net Art Museum?

The Last Real Net Art Museum was a provocation to museums who in the late 1990s and early 2000s started making their own online net art exhibitions and collections – and at first they seemed to succeed, but it turned out they didn’t. In my title, ‘Real’ meant that an online collection should be based on links, because the net was about making links to people, information, etc. A good example was äda ’web designed by Vivian Selbo and curated by Benjamin Weil for the Walker Art Centre in Minneapolis between 1995 and 1998. Because this and other projects ended, another phenomenon started with museums like the Guggenheim, Tate and Whitney who acquired copies of Internet art and just kept these somewhere on a floppy or a CD, or showed the work in a pop-up window on their website – for me this was not real, and rather disrespectful of the artworks. And ‘Last’ meant that this previous method was completely disappearing.

The Last Real Net Art Museum was also sort of self-referential because of the First Real Net Art Gallery that I made in 1998, where I sold net art. It wasn’t a gallery selling offline art online, but people could buy online art for the first time. Since the First gallery was still well known in 2000, and to make the connection between the works, the second one became the Last…

Talking about museums and collections, was MBCBFTW ever acquired?

Yes, there is a copy at Telepolis, which was sold for what I thought back then was the amazing sum of 300 German Marks, but it was above all a statement. It’s also in a museum collection, MEIAC (http://www.meiac.es/) in Spain, and has been bought by a private collector, too. There is one more edition left. For this one I think it makes sense to sell the complete package: a computer, a monitor with the right resolution (800 x 600) a slowed-down server connection, an emulator with the old Netscape browser and all the other settings. Everything is emulated, simulated and fake, but the work is alive in its most precious state.

I have also adapted the work at certain times, for example around 2006 I added Google Ads to the website, not to become rich, but to reflect the Web of that time. Without the Ads it seemed old-fashioned and I wanted it to be alive and contemporary. About a year ago I removed them, because they made the work look outdated. It was interesting to see what Google thought suited the site – mostly non-governmental sites. Unfortunately, I never captured this version. That’s the irony – part of me is very much involved in preserving the Web, but when it’s about my own work, I change things immediately and forget how it was before.

The adaptations to the medium are striking in all the different interpretations. Seeing all the works next to each other illustrates a historical technical lineage of online practices: from HTML frames to blogs, games, video and VR. In a sense the Web seems almost to be little more than a constantly changing technical environment. Many have argued that this emphasis on medium specificity is one of the reasons why it took/is taking so long for net art to be taken seriously by the traditional art worlds. How do you view the relationship between the concept and the technical or formal aspects of the work?

For me the main concept and message of the work is the medium specificity. When thinking about the MBCBFTW exhibition we noticed now that it is also about the development of the Web. Yes, it has many technical translations. For example, the work by Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn (previously known as Entropy8Zuper!) was made in Flash; it was interactive and had sound, and for that time it was the most obvious software to use. Then Blog and Twitter versions were made, people kept changing it to other realities of the Web. What is interesting though is that the last interpretation, by Inbal Shirin Anlen, brought it back to its original classic HTML structure. The variations are some sort of tribute to the medium: these can range from manifestations of particular elements, to an aesthetic message or a personal statement in the medium.

I strongly believe that there is no contradiction between medium specificity and a mature conceptual message. For that reason I also think that it’s important to always emphasise how the work is made – it just being ‘art’ is not enough; I cannot forget about the Web or the net. In my article ‘Flat against the Wall’ of 2007, I wrote that while it is fine that Web art is part of the art market now, it would be a tragedy if we lost its connection to the Web. It can be a topic of contemporary art but it should stay part of the new media art scene.

For the exhibition you choose specific interpretations. What were your criteria for this selection?

We had to make a selection because some things have been lost. At the time of the Last Real Net Art Museum I thought it was important to just have the links to the works rather than showing copies of the works. So, unfortunately now some works are missing because nobody saved them, the Internet Archive didn’t capture them, and the artists (some of them students at the time) said they didn’t have their work anymore. For example, Web comics were popular at the beginning of the century and someone made a version in that style, which unfortunately didn’t survive either.

In the exhibition we left out works that had a similar structure, but almost all of them are featured in the book that was made for the show by House of Electronic Arts (HeK) in Basel, for example, Don Quichote Came Back From The War (2006) by santo_file group. But we also left some out of the exhibition that – perhaps surprisingly – were just too difficult to show such as the beautiful animated gif by Mike Konstantinov. He made this animated gif in 2000 and it was widely used for and known as a website banner. This work was a typical banner, 468 x 60 in size, and because it doesn’t use any of the images from the original work is also mimicked the cheesiness of banners. In the book it is printed frame-by-frame, but it’s difficult to show the banner phenomenon in an exhibition. We thought of several ways: put it on a random website, or against a black background, but in the end we decided not to present it at all. It just didn’t work.

Another example that isn’t included in the exhibition is Roman Leibov’s work. Leibov is the unofficial father of the Russian Internet. In the mid-1990s the Web in Russia had a strong literary tradition, it was all about games with words and meaningful and innovative hypertexts, including of course many references to Russian literature. I made MBCBFTW in English to intentionally distance myself from this tradition. I wanted to create something very formal because I’m very interested in the structures of the browser, the frames, etc. Had I made it in Russian it would have ended up in a different culture. At the time it was a massive effort, because English wasn’t my language. Then I asked Roman Leibov to make a text version and post it on the Russian Internet, which he did. He took every frame and described it like a film critic, and it ends with a monologue, making it into a piece of literature.

How do you see this type of approach now? To me at times it seems there is much less experimentation with templates or in the browser.

Yes, it’s more difficult to be curious now. The browser is still generous, you can open the source code and look at it, but it’s very complicated to change the code, if you can do it at all. The gap between people looking at and those making the pages has become enormous now. At the time it was easy to copy and modify other people’s pages, but now it is much more difficult to do this.

In this sense, perhaps, Blingee is my favourite place to go at the moment. It is a creative community where people fulfil their wish to make something themselves, where they can construct something from other people’s material. It isn’t because they can’t afford Photoshop, it’s about finding things made by others and reusing them such that they become completely different, and also that those layers can be made visible again, showing the elements that have been used. All the layers in the images have value and they are there to be admired. You can also see the tricks people use to fool or misuse the system. Unfortunately, there isn’t a Blingee version of MBCBFTW yet.

What I like about the work from an historical point of view that it consists of two types of archives: the table with all the information and components that are necessary to reconstruct the work, and the living archive of different people’s interpretations. Which method do you prefer?

The archive is an interesting part. MBCBFTW consists of many files, yet it is only 72 KB in size, which is smaller than a small image today. In the early 2000s I wanted to write about the life of a work of art, its making, what is important to keep and its preservation, even though I didn’t think it was necessary for net art. Now I see that it does make sense to write down all these details, so Mona Ulrich and I updated the old table for the exhibition. The table shows all the files, their sizes and which one is used in what frame. Even if someone has never seen the work, it could be reconstructed by following the information on the table. Maybe someone should try it sometime.

However, thinking about the future of the work, I prefer the interpretative approaches, because they are closer to my way of working. I’m also happy, and proud, that people take it as a structure and build something else out of it. I also think it’s interesting to see to what extent it can still be recognised as being an interpretation of MBCFTW, what are those elements? For example, Ignacio Nieto made a tribute for the Chilean soldiers who died in the mountains, it’s his story, and he merely used the same frame structure, but he asked me whether he could make and show the work. It is a bit strange of course, because I don’t have a patent for the frames, yet the specific use of the frames is one of the work’s main characteristics. I also noticed that most people keep the left frame intact and the frames to the right proportionally become smaller. Perhaps it’s similar to the golden ratio in design, but then for frames. A final characteristic is that all the interpretations always end with nothing, with black frames.

The exhibitions My Boyfriend Came Back From The War, online since 1996 are on view till 20 March 2016 at MU in Eindhoven (NL) and HEK in Basel (CH).

Features Image: “Dead Copyright” installation view, 2015

Antonio Roberts is a digital artist based in Birmingham. In 2011 he has completed his Masters level studies in Digital Arts in Performance at Birmingham City University. His artwork focuses on the errors and glitches generated by digital technology. An underlying theme of his work is open source software and collaborative practices. His video work has been screened in Chicago, Illinois, at GLI.TC/H, Notacon in Cleaveland, Ohio, and Newcastle Borough Museum and Art Gallery, amongst other places.

In October 2015 he opened his first solo exhibition, “Permission Taken“, at Birmingham Open Media and in these weeks is taking part to “Jerwood Encounters: Common Property” (15th January – 21st February 2016, Jerwood Visual Arts), a group show curated by Hannah Pierce focused on the limits of Copyright when it’s about visual arts, with two projects: the installation “Transformative Use” and a collection of four works, “I Disappear”, “Blurred Lines”, “My Sweet Lord” and “Ice Ice Baby”.

Filippo Lorenzin: You’ve been always interested in how corporate and industrial logics affect daily life and art. How did you get interested in these questions?

Antonio Roberts: It’s a by-product of my interest in open source software and free culture, something which I’ve been interested in from as early as 2002 but only started taking seriously around 2007. One of the main motivators of this was my reaction to Adobe Photoshop and its influence on creative practices. My experience of studying Multimedia Graphics – and I’m sure the same can be said for Graphic Design, Illustration and any creative practice – was that it seemed more like an exercise in how to use Adobe products, not how to be creative with tools. It felt like Adobe software had gone from being one of the many tools for creating art to the art in itself. This corporate sponsorship of course has many implications for how we create and disseminate art. It poses restrictions and dictates who and who cannot create art.

FL: Copyright issues are one of the main focuses of your research and this fascinates me because of your age. You (as me, by the way) have experienced probably the most troublesome period for Copyright systems, with the wide spread of p2p networking and remixing approaches to cultural industry products. What do you think?

AR: I’m inclined to agree. I’ve had access to the internet since I was around 14 years old and in that time I’ve seen the internet and culture as a whole change drastically. For me the rise and fall of Napster, spearheaded by Metallica’s very public outcry against it, signalled the beginning of the end of the free internet that I had only known for not even a year.

Around that time Digital Rights Management (DRM) became a hot topic. The entertainment industry saw it (and suing everyone) as the only way to protect their property and so kept bundling DRM with their products, which often at times resulted in a broken experience for the user. One example that springs to mind was the attempt to make CDs unreadable by computers (and so prevent ripping), by adding in corrupted data at the beginning of CD. Whilst it did temporarily stop people to using it on computers – you could simply use a marker pen to circumvent it – it also prevented some CD players from using the CD and in general was obtrusive. This cat and mouse game is still going on to the point where simply attempting to bypass DRM to watch/listen to something that you have purchased, can be an illegal act.

As mentioned before, It wasn’t until around 2007 that I began to reconsider how Copyright affected my work. By this time I saw that there was more weight being pushed behind open source software, free culture and things like the Creative Commons licences, and so I started to get involved myself. The first stage was ditching all proprietary software (which I did in 2009) and then licensing my work under Creative Commons licences.

FL: “Jerwood Encounters: Common Property”, curated by Hannah Pierce, is a group show that seeks to investigate the new borders of Copyright, especially in regard of art. How would you define the state of these questions in UK?

AR: I think Copyright as a whole is in a terrible state. As Cory Doctorow suggests in the exhibition programme (which is in itself an excerpt from his book “Information Doesn’t want to be Free”) Copyright as we know it isn’t written for artists or any individual. Its verbose terms and complexities cannot be understood and are probably not even read by most of us. They are written for other lawyers. If, in order to go about our creative business, we are expected to read and understand the terms and conditions and law – it is estimated that it would take 76 days to read all of the Ts and Cs of websites we use – what time do we have to be creative?

FL: What’s your point of view, from your position as an artist?

AR: I think Copyright is a mess because it tries to dictate how we should be creative. Creativity is free-flowing. Copyright, and its cousins patents and trademarks, justify their existence by saying that these restrictions encourage innovative new ideas but what they do is just stop us.

FL: “Dead Copyright” reminds me some reflections by Walter Benjamin on the shock of the city, about how advertising assaults our senses 24/7 with louder and louder messages – until it reaches a state of entropy. At this stage the message isn’t actually more important than the media itself, quoting Marshall McLuhan, and all the brands create a single, colourful ambient. How much this reality has been voluntarily planned by corporations, in your own opinion?

AR: I think it’s all completely planned. The more pervasive the advertising becomes the more we accept it as part of our every day life and culture. On the other side this does mean that they have to try ever more invasive methods to get our attention. Think about the uproar over the Coca Cola van at Christmas, or Cadbury’s at Easter. They have usurped the original holidays and are more important.

FL: The reduction of brands to colorful simple shapes created something that visually reminds some of op art works, a movement that experimented with visual perceptions and that has been an important inspiration for fashion and design. I was just wondering what you think of this similarity: is there any real connection between your work and those works?

AR: Yes, certainly and this comes through with my use of glitch art techniques. In glitch art we’re often trying to find signal in the noise, and I find that many successful glitch art works (however you define successful) have some resemblance to the original yet are transformed and destroyed in way.

FL: With “Transformative Use” you use shapes that recall not just brands, but a wider imagery. It’s as if you’re focusing on other targets: can I ask you how did you get interested in this new research?

AR: I recalled all that I had learnt during my residency at University of Birmingham and during the CopyrightX course. From this I paid particular focus to the Sonny Bono act from 1998. This effectively extended the Copyright terms so that it won’t be until 2023 until works from 1923 begin to enter the Public Domain. This act is sometimes called the Mickey Mouse Protection Act, which led me to use them as a focus point for the work. Mickey Mouse should, by now, be in the Public Domain but they’ve fought to stop this in order to “protect” their brand.

People in favour of long or perpetual Copyright terms usually point to it allowing artists to reap the benefits of creating work. In truth, however, only a very small percentage of works made will be profitable in the future. To put it another way, how many books published today will see reprints? I don’t have any official statistics, but I know it would be a small percentage. So, extended Copyright terms only really benefit the small percentage of artists or publishers, whilst harming everyone else.

FL: What does it mean to deal with corporate imagery within such a chaotic and in a somewhat charming ambience? I mean, what remains a logo or a character when it gets lost within this borderless blob? Are the corporations losing their borders too, maybe?

AR: Yes.

FL: As discussed before, “Transformative Use” has been inspired by two previous projects: do you think that in future you’ll make a work that will update for the fourth time these reflections of yours?

AR: Most certainly yes. “Permission Taken” will be having an iteration at the University of Birmingham in March 2016 and will feature new and existing work. Aside from this I will continue to work with found materials but with a more explicit intention to provoke discussion around Copyright.

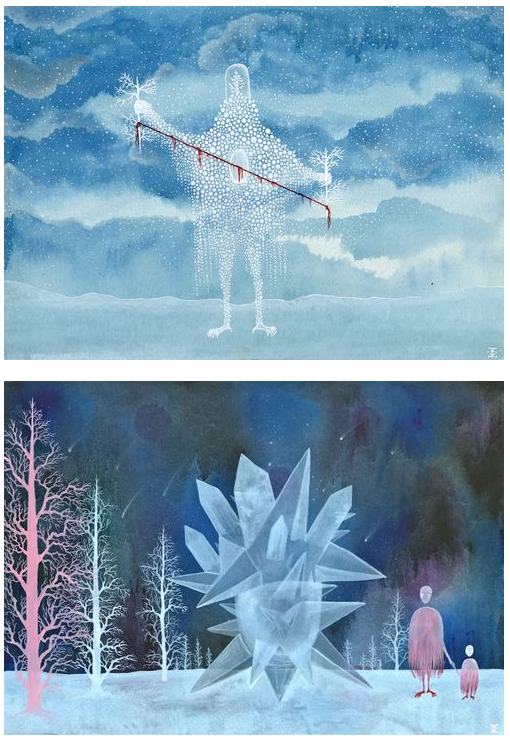

In a mysterious pine forest, inhabited by half-human, half-animal creatures, the dismembered white body of a furry god is slowly reassembled. A creature with the head of a black bear pulls down the decapitated body from a tall rock. A red-robed character with a crimson wolf’s face, decorated with sharp white teeth, fetches the severed head. Another brings the eyeballs; another, the skull. Finally, in an illuminated multi-coloured tent glowing in the darkness of the woods, a character with the head of a triceratops and a cloak of many-coloured feathers performs a ritual involving magic crystals and a dead bird doused in blood. The film ends with a single glimpse of the white god’s foot, planted in a field of snow, sufficient to suggest that he, she or it has been brought back to life.

I first came across Magic Blood Machine as one of the staff picks on the Vimeo site in October 2014. It was on a list of spooky videos for Hallowe’en. The rest of them looked fairly conventional, but the still for Magic Blood Machine stood out: the red-robed character from the film standing amongst dark pine trees, looking a bit like a Roman Catholic Cardinal, a bit like Anubis – the jackal-headed god of Egyptian mythology – and a bit like Reynard the Fox. When I watched the video, I was struck by the same mixture of associations: it seemed to combine elements of the crucifiction and resurrection of Jesus, the dismemberment and restoration of Osiris, and the Green Man myth. Folk-stories, mythology, the occult, the macabre, and even a touch of science fiction were all in the mix. But its visual design, filmic and narrative qualities were just as striking. There are no words spoken, and the pace is slow, but nevertheless the film exerts a powerful compulsion, partly because of the expertise with which each sequence unfolds and leads us to the next, and partly because it’s so full of unanswered questions. The actions of the strange characters in the pine forest seem charged with hidden meaning, as do the characters themselves, sharply-differentiated from one another as they are by virtue of the brilliant costume-design. There is a strong sense of place in the outdoor filming, and a strong sense of the tactile as well: the way the characters stroke the dead god’s fur, fondle the magic crystals or pour blood over the breast of the dead bird, for example. And despite the use of expressionless masks, there are moments of powerful emotion. When the red creature, having retrieved the white god’s severed head, lays it next to the rest of the body and then sits beside the corpse, holding its hand, it eloquently conveys a sense of love and grief.

Magic Blood Machine was made by a Norwegian artist and film-maker called Ingrid Torvund, in close collaboration with her partner Jonas Mailand, and with music by Jan Erik Mikalsen. It took three years to make (2009-12), and a sequel called When I Go Out I Bleed Magic – which Ingrid describes as the second part of a trilogy – was released earlier in 2015. For me, When I Go Out I Bleed Magic is less compelling than its predecessor, but if anything the design of the film, in terms of costumes and settings, is even more impressive. Ingrid makes almost all the costumes and props herself, and they are works of art in their own right, some of which she has exhibited separately. She has also exhibited her drawings and published many of them in a book, again with the title When I Go Out I Bleed Magic.

Ingrid’s work strikes me as an example of the enabling power of the Web, which can sometimes allow genuinely original artists to reach international audiences they would have found it very difficult to access at any time before the 1990s. It also allows the likes of me to get in touch and start up a conversation out of the blue. Accordingly, I contacted Ingrid via email to ask about her work, and the results are reproduced below.

Edward Picot: Can I ask you about the making of the costumes and props for your films?

Ingrid Torvund: I make the costumes and props myself mostly, sometimes I get some help from my friends and family, if it´s large set pieces and so on. I like to take my time making these things, it`s a slow process but it´s one of these things that makes life worth living.

EP: Were you at art school, and if so did you study art, textiles, film or all three?

IT: I went to Oslo National Academy of the Arts,where I took a bachelor degree in fine art. While I was there I made my first short, “Magic Blood Machine“, and I worked on it for three years. I took courses in film, philosophy and many other subjects.

EP: Can you describe your creative process a little bit? Do you start off with an idea for a story, or with sketches in your sketchbook?

IT: it’s really random how I find inspiration, but sometimes I find a nice tactile material that I want to work with and I start by just trying out how and then I can make something that gives the audience the same feeling I got when I first saw it. And sometimes I get a picture in my head of a scene I want to make and then I try to figure out how to make it, then I draw it (but not very detailed and not very good 🙂

I wish I could say I plan out projects better, but I usually just make what I want to make. Over the years the planning of the filmprojects has become more detailed, but this is because I have to [plan things out] when I apply for funding and it’s a real creative killer.

For the last film “When I Go Out I Bleed Magic” we (me and Jonas) made a long storyboard with many scenes, but in the end we didn’t get to make them all due to lack of funding, lack of time and plain exhaustion.

EP: You say you like to take your time making the costumes, props and so forth. Does this mean that your ideas about the film you’re going to make grow quite slowly and organically as you’re in the process of making things?

IT: Yes it does, it’s a long process and I usually try to finish one little part at a time: a costume, a set piece and so forth. But when the time comes to shoot the scene, I have to but all the pieces together, and then I have a time limit. In the two films I’ve made so far I’ve been borrowing my dad’s place, because there I have the space to actually build a little studio in the summer. But since this is his workplace normally, I have to clean it out before they come back from their holiday 🙂 So the summer is a really intense period in the year for me and I have to plan it out more, due to the fact that when I go to work there, I can’t get away, so I must buy all the materials I need before I go. I don’t have a car or a licence and it’s in the countryside. We do have a little boat that I can take to the grocery store 🙂

EP: You mention you’ve got a boat – and lo and behold, there’s the red character rowing a boat in Magic Blood Machine. I’m guessing from this that the boat in the film is your own boat, and the lake which appears in both films is the lake where you live.

IT: Yes, most of the places in the movies are from around where I grew up. I also think that it’s important to find inspiration from real and often personal things in life. it feels important to me to know that the project has some kind of root in something real. At my last exhibition my mother gave me some very old school books that I had made some drawings in, and it was almost disturbing how much some of them resembled some of my more current drawings!

EP: Let me ask you about Jonas. How do you work with him? How did you get to know each other and work together, and do you write together, or does he do the camerawork while you put on the costumes and do the acting?

IT: I met Jonas while we were going to an art school in Oslo seven years ago, at the time I was already making characters and installations and we started to date while I was building a forest installation inside a room. He has always had great interest for films and making them, and at that point I was thinking of trying to bring my characters to life by making them into costumes I could wear. After a year we started working on Magic Blood Machine. From that point he has done all the camerawork, while I do all the costumes, set pieces and “acting”. We usually edit the films together and sometimes we make an edit each and then compare them, and choose what we think works the best. I’ve been asked before how we collaborate on these projects and sometimes I find it a little difficult to answer, because we live and work together and we have no rules on who does what in these films. But I do know I spend most of my time thinking or working on these films and Jonas takes part in that if I ask him to. Without him I would not be able to make films like these and my life would suck.

EP: Lastly, would you like to say a bit about the mixture of mythological references in your films?

IT: I have always been fascinated with the mixture of pagan and Christian culture. When I was young I found a book called “Norske Hexeformularer og magiske opskrifter”: it’s a collection of spells and magical recepies from 1600-1900. The spells are collected from small black books found throughout the country, often hidden away. Some would put them under the church steps in an attempt to get rid of them. My films are inspired by these rituals and the conflict between nature and religion. I grew up going to church a lot and I think the mix of church and folklore is something I use as inspiration when I make films.

I think I find the history of how people lived and their traditions even more fascinating then fairy tales, for example people used to think that their newborn babies sometimes got exchanged with a person from under the earth.The child then got some kind of physical change,like a weird growth or huge eyes or it suddenly looks very old. The only way to fix it was to lure the under earth person to tell you their real age. You did this by doing weird and absurd stuff, like making porridge in an eggshell or making blood sausage in an catskin. Then it would suddenly tell you how old it was and then it would die. Leaving a little lump of ash and bones…

More information about Ingrid Torvund can be found on her website, http://torvund.tumblr.com/. Magic Blood Machine is on Vimeo at https://vimeo.com/44936472, and When I Go Out I Bleed Magic is also on Vimeo, at https://vimeo.com/44936472.

Featured image: “Binoculars” at CHB in Berlin (2013)

Varvara Guljajeva & Mar Canet have been working together as an artist duo since 2009. They have exhibited their art pieces in a number of international shows and festivals. As an artist duo they locate thermselves in the fields of art and technology, and are interested in new forms of art and innovation, which includes the application of knitting digital fabrication. They use and challenge technology in order to explore novel concepts in art and design. Hence, research is an integral part of their creative practice. In addition to kinetic and interactive installations, the artists have also experience with working in public spaces and with urban media.

Varvara is originally from Estonia, and gained her bachelor degree in IT from Estonian IT College, and a masters degree in digital media from ISNM in Germany and currently is a PhD candidate at the Estonian Art Academy in the department of Art and Design. Mar (born in Barcelona) has two degrees: in art and design from ESDI in Barcelona and in computer game development from University Central Lancashire in UK. He is also a co-founder of Derivart and Lummo.

Filippo Lorenzin: Open culture is one of the main points of your research and activity. Could you describe how this influences your art practice?

Varvara & Mar: We are living in very exciting times. Open source has introduced democratization of production and creation. Now you can build your own 3D printer, laser cutter, knitting machine, make a light dimmer circuit or develop a body tracking system. Some years ago we couldn’t even imagine this and now we have access to this knowledge. People share their creations and these process, which is incredibly inspiring for us and many more people. Thus, knowledge is built on top of knowledge. We make use of open source marterial in our work and we try also to contribute back. This is the whole point of open source in our mind. And if one looks in the perspective of art to open source projects, then really many open source projects have artists on board, for example, OpenFrameworks, Processing, and more.

Open source also has an educational aspec. We do many workshops with people and teach what we know and how we work. We think open source culture is largely based on the spirit being open to sharing knowledge with many others.

FL: I’m really fascinated by your interest in textile fabrication. it reminds me the early industrial developments that were deeply connected to in the textiles industry. How and why would knitting be integrated these days as part of a makers’ culture?

V&M: The process of integration is well under way. There has been a good number of makerspaces who have dedicated areas for textile production, like WeMake in Milan and STPLN in Malmö. And believe it or not this simple thing helps to introduce gender balance in these kind of places. We’re not just talking about innovation, which can boost gender equality when you introduce knitting to hacking. We’re also talking about the democratisation of production, when thinking about clothing too. This area is quite vital and commonly understood. 3D printing toys is a cool activity for a weekend, but then it becomes boring. Knitting a sweater or a scarf has real value and the quality is always higher than a typical mass produced factory product.

For 3D printing we cannot say the same. Don’t get us wrong, we are not against the 3D printing. We love it and have six printers in our studio. Our point is that the areas of concern for digital fabrication are not complete, and the founders of FabLab have overlooked the whole area of textiles.

FL: You’ve run many workshops taking in account various topics such as 3D printing, solar energy and knitting, of course. How do these activities connect with your research?

V&M: First of all, we like to teach and interact with our students. Second, preparing a workshop, allows us to research more about the field, and organise and share our accumulated knowledge and experience.

And finally, workshops are one part of our income. We don’t have any other jobs on the side, and exhibitions and commissions are not regular and do not always pay well, and yet the bills keep coming in. Hence, workshops help us to pay our bills.

FL: One of your works which most fascinate me is “Sonima” (2010). It’s a project that takes in account questions that have become quite recurrent in last months, mostly linked to Anthropocene discussions. The soft coexistence of technology and nature which is organic and artifical. Which is one of the main topics of your research: why are you so interested in this question? It looks like you’re trying to develop experiments for an utopistic future in which humans and nature live in symbiosis. Am I wrong?

V&M: Yes, many of our works express our futuristic thoughts or imagination where the digital age will lead us and our planet to. It is nice that you have noticed this. I would say this kind of concept in 2010 was quite subconscious. I (Varvara) was very interested in organic form but with mutational origins but still adapted by nature.

More conscious approach towards anthropocene epoch can be seen and felt in “Tree of Hands” (2015), which is one of our recent works. However, it looks like we have touched quite a taboo topic. For instance, “Tree of Hands” was rejected by jury of PAD London fair because of its depressive concept.

FL: “Shopping in 1 Minute” (2011) is another project I would like to ask you about. This work is about consumerism at its finest (or worst), turning one of the most typical capitalistic places (supermarkets) into ludic spaces. It’s a piece of social art that presents itself without informing the public what is right and what is wrong, but it rather suggests in a more subtle way the perversion at the base of that system. What do you think?

V&M: Yes. What we are doing is the absurd exaggeration of the same action (buying) to a maximum with one but: not buying and playing instead. There is a saying that shopping is 5 min happiness. The artwork tries to create a synthetic feeling of satisfaction of the ability to buy. The shopping centers are doing everything to stimulate our consumption needs, and our artwork manages to get inside their ecosystem and playfully releases that artificial desire to buy.

FL: With at least a couple of projects, you’ve also worked to the redefine hurban landscapes by looking at the invisble while at the same time taking on rather specific forces such as mass use of Wi-Fi networks becoming part of the everyday. I can’t help thinking that this is somehow related to privacy questions, probably because one of the most notorious scandals some years ago was Google’s secret recording of Wi-Fi networks with their Street View cars. Am I wrong?

V&M: Not really. But definitely Google has played a role in feeing our concerns about being watched, spied, hacked, scanned, etc. For example, the last scan for WiFi router names we did last summer in Tallinn some people were quite freaked out seeing a person on a bike with a camera on its head and tablet in front. I was even once asked if I worked for Google. 🙂 Anyways, the project was great fun for us, and we got to explore the city and discover the whole invisible communications networks and the self expressive layers of it all. After the Tallinn scan we even changed our minds about the 32-character local Twitter that the WiFi router SSID could be used for. The Tallinn experience showed us the new tendency: where people would use radio waves for semi-anonymous graffiti, communicating sometimes silly, protective, racist or political messages.

Talking about inspiration for this project, we got our interest for WiFi names from one article talking about the ability to track down pro- and contra-Obama communities by just looking at WiFi names in the neighborhood. This was before the US president election. Then we started to thinking of an art project on this topic.

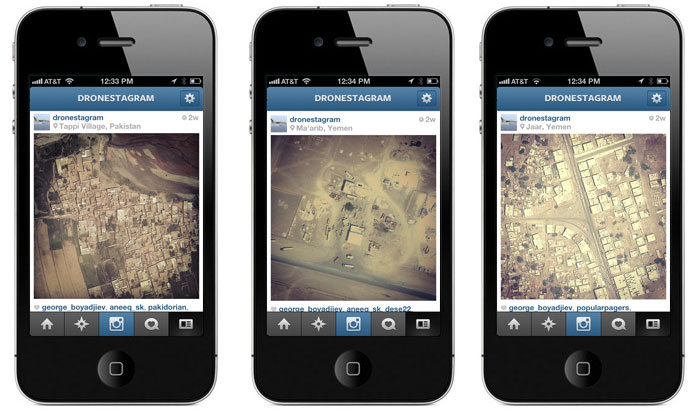

FL: “The Rythm of City” (2011) is another project which is also ‘subtly’ related to control issues. The idea that someone can depict the state of a city by looking at data deducted from social media and web platforms. This type of thing is real now isn’t it – what do you think?

V&M: Definitely it is. However, the work’s main intention is not to talk about control issues rather about big data and its applications. Perhaps the main intention of this work is to offer to the viewer(s) a birds eye view on different cities in real time. In other words, The Rhythm of City allows you to zoom out and witness the larger picture on the current situation. And this larger picture is formed by everybody’s activity on social media, which is tracked down every minute. We call this action ‘unaware participation’ by digital inhabitants. The urban studies of Bornstein & Bornstein from early 1970s served as an inspiration for this artwork. They had discovered a positive correlation between the walking speed of pedestrians and the size of a city. Simply put: the bigger a city, the faster people move. The artwork demonstrates our interpretation of a city’s tempo through in its digital form or life. Hence, The artwork talks about pace of life in different cities at the same moment when the piece is viewed.

FL: What have you been working on these last few months and what plans do you have for 2016?

V&M: We are working on a series of new works talking about money. When we have completed “Wishing Wall” in London in 2014, since then we have noticed that the majority of people, especially a younger audience, wish for money. This really caught our attention. The ongoing hard economical situation in Europe pushes forward the need for money and also introduces a growing gap between the economical classes. So we’re investigating people’s desire for money and its connection with happiness. Making use of interactive technology we are aiming to approach playfully and magically the desire for becoming rich. At the same time, we cannot let go of knitting. At present, we are working on an open source flat knitting machine, which will be able to knit patterns also. Besides the new productions, we are showing our existing works in various exhibitions. For the confirmed ones, “The Rhythm of City” will be part of “REAL-TIME” a group show curated by Pau Waelder in Santa Monica museum in Barcelona from the 28th January. In February “Digital Revolution” (the touring exhibition by Barbican), which “Wishing Wall” is part of, moves from Onassis Cultural Center in Athens to Zorlu Center in Istanbul. And hopefully we get couple of other shows and new productions that are in the air at the moment and still to be confirmed soon.

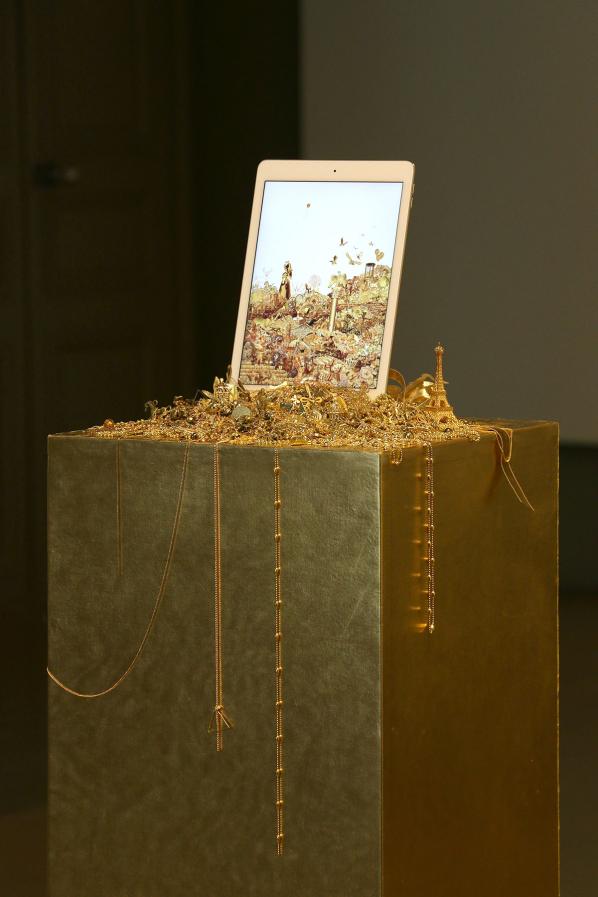

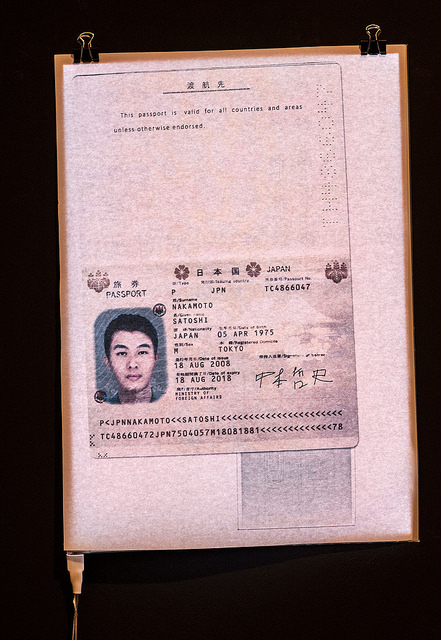

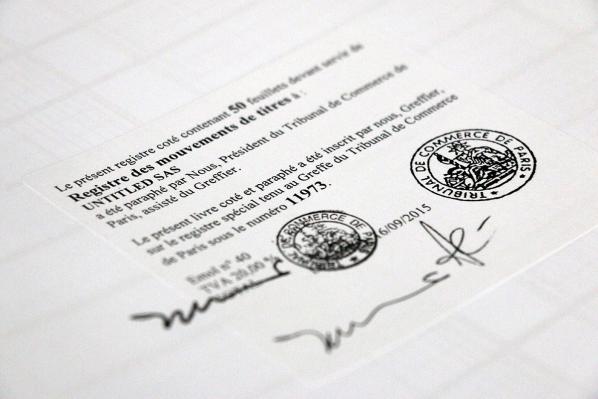

French artists Émilie Brout and Maxime Marion contribute three pieces to The Human Face of Cryptoeconomies exhibition. Gold and Glitter is a painstakingly assembled installation of collaged GIFs. Previous installations have featured the GIFs displayed on a gold iPad atop a pile of collected gold trinkets; at Furtherfield Gallery now a single golden helium balloon hovers in front of a floor to ceiling projection. Nakamoto (The Proof) is video documentation of the artists’ efforts to try and place a face on the elusive Bitcoin creator, Satoshi Nakamoto (but is it his face in the end? We don’t know). Untitled SAS is a registered French company without employees and whose sole purpose is to exist as a work of art.

Brout and Marion’s work can be situated among artists and art practices who have grappled with how to think about value and objects—or more precisely, how objects are inscribed (and sometimes not) into an idea of what is valuable. In a recent article for Mute Magazine, authors Daniel Spaulding and Nicole Demby point out that “Value is a specific social relation that causes the products of labor to appear and to exchange as equivalents; it is not an all-penetrating miasma.”1 Value is a process by which bodies are sorted and edited but it is not a default spectrum on to which all bodies must fall in varying degrees. This clarification makes explicit the fact that while the relationships productive of value allow “products of labor to appear and to [be exchanged]”2 this is not an effect that is extended to all products of labor. Attempts to isolate the underlying logic of this sorting mechanism are often at the heart of art practices dealing with questions of value and commodification. Like Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes or Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, these artworks become interesting problematics for the question of art and value for the ways in which they are able to straddle two economic realms—that of the art object and the commercial object—while resisting total inclusion in either.

The Human Face of Cryptoeconomies picks up these themes in an art context and repositions them alongside digital cultures and emerging digital economies. In Brout and Marion’s work alone, concepts of kitsch, identity, and human capital have been inhabited and imported from their originary realms into the digital. Answering questions remotely, Brout and Marion were kind enough to give us some insights into their work and process. My goal here has been to draw out some points about the operation of value that are at work in Brout and Marion’s practice, as well as to point towards an idea of how value is transformed, or even mutated, in the digital age.

* * *

Brout and Marion open up with an interesting provocation. They explain, “When we showed the project [Glitter and Gold] in Paris this year, people stole a lot of objects, even if they were very cheap. Gold has an incredible power of attraction.”

It is telling, to some extent, that Brout and Marion’s meditations on gold have an almost direct link to the visual metaphor used by Clement Greenberg in his 1939 essay Avante-Garde and Kitsch to describe the relation between culture—epitomized in the avant-garde—and the ruling class. Greenberg writes, “No culture can develop without a social basis, without a source of stable income. And in the case of the avant-garde, this was provided by an elite among the ruling class of that society from which it assumed itself to be cut off, but to which it has always remained attached by an umbilical cord of gold.”3 This relation is subverted in Gold and Glitter, which takes for its currency—its umbilical cord of gold—a kind of unquantifiable labor that is seemingly (and perhaps somewhat sinisterly) always embedded in discussions of the digital.

For Greenberg, kitsch always existed in relation to the avant-garde; one fed and supported the other, even if the way in which that relation of sustenance worked was by negation. And while Greenberg’s theory relies on his own strict allegiances to hierarchical society, privileged classes, the values of private property, and all the other divisive tenets of capitalism that we now know all too well can be destructive. Kitsch remains useful to us for the ways in which it allows the means of production to enter into a consideration of aesthetics. Here the recent writing of Boris Groys can be useful. In an essay written for e-flux titled Art and Money, Groys makes a compelling case for why we should persist in a sympathetic reading of Greenberg. He argues that Greenberg’s incisions amongst the haves and have nots of culture can be cut across different lines; that because Greenberg identifies avant-garde art as art that is invested in demonstrating the way in which is it is made and it doesn’t allow for its evaluation by taste. Avant-garde art shows its guts to us all, and on equal terms—“its productive side, its poetics, the devices and practices that bring it into being” and inasmuch “should be analyzed according the same criteria as objects like cars, trains, or planes.”4

For Groys this distinction situates the avant-garde within a constructivist and productivist context, opening up artworks themselves to be appreciated for their production, or rather, “in terms that refer more to the activities of scientists and workers than to the lifestyle of the leisure class.”5 In this way Glitter and Gold, like Brout and Marion’s other artworks, is to be appreciated not for any transcendent reason but rather for the means by which it came into existence. ‘The processes of searching and collaging golden GIFs sit side by side with the physical work of accumulating the golden trinkets for display: “We collected these objects for a long time” the artists explain, “some were personal objects (child dolphin pendant, in true gold), others were given or found in flea markets, bought in bazaars … We wanted to have a lot of different types and symbols, from a Hand of Fatima to golden chain, skulls, butterflies, etc.”

Furthermore, Glitter and Gold can be understood as the product of compounding labors: the labor of Brout and Marion in collecting their artifacts, the labor necessary to create the artifacts, the labor of GIF artists, the labor of searching for said GIFs, the labor of weaving a digital collage. These on-going processes forge, trace, and re-trace paths during which, at some point, gold takes on the function as aesthetic shorthand for value. As Brout and Marion explain, “Here the question is more about the intrinsic values we all find in Gold, even when it just looks like gold. Gold turns any prosaic product into something desirable. [Gold and Glitter] is less about economics than about perceived value.”

Groys provides his reading of Greenberg as a means of pointing towards a materiality that is always in excess of existing coordinates of value. If value always reveals the products of labor as they enter into a zone of exchange, it is something else proper to contemporary art that reveals another materiality beyond this exchange. For Groys, this something else is at work in the dynamics of art exhibition, which can render visible otherwise invisible forces and their material substrates. This is certainly a potential that is explored by Brout and Marion. In Nakamoto (The Proof), the viewer can watch the artists’ attempt at creating a passport for the infamous and elusive Bitcoin creator Satoshi Nakamoto. At present, it is unclear whether Nakamoto is a single person or group of people, though the Nakamoto legacy as creator of Bitcoin, a virtual currency widely used on darknets, is larger than life. Adding to this myth, after publishing the paper to kickstart bitcoin via the Cryptography Mailing List in 2008, and launching the Bitcoin software client in 2009, Nakamoto has only sporadically been seen participating in the project with others via mailing lists before making a final, formal disappearance in 2011, explaining that he/she/they had “moved on to other things.”6 Nakamoto’s disappearance, coupled with the fact that Nakamoto’s estimated net worth must be somewhere in the hundred millions Euros, has given rise to the modern-day myth of Nakamoto, and with it an insatiable curiosity to uncover the identity and whereabouts of the elusive Bitcoin creator.

Brout and Marion make their own attempt to summons the mysterious Nakamoto back to life by putting together the evidence of Nakamoto’s existence and procuring a Japanese passport using none other than the technologies that Nakamoto’s Bitcoin both imparted and facilitated. When asked if they feared for their own self-preservation in seeing this project through, Brout and Marion answered, “Yes, even if we were pretty sure that it would be easy to prove our intention to the authorities, and that the fake passport couldn’t be useful to anybody, buying a fake passport is still illegal.” They add, “But we also wanted to play the game entirely, so we made every possible effort to preserve our anonymity during our journey on the darknets.”

However Brout and Marion have yet to receive the passport; as they explain, “The last time we received information, the document was in transit at the Romanian border.” When asked if they expect to receive the passport, they respond, “No, today we think we will never receive it. We are completely sure that it has existed, but we’ll surely never know what happened to it.” What, then, will they do if they never receive the passport? “Maybe just continue to exhibit the only proof of it we have!” they exclaim. “There is something beautiful in it: we tried to create a physical proof of the existence of a contemporary myth, using digital technology and digital money, and the only thing we have is a scan!”

If Brout and Marion’s nonchalance seems unexpected then it is because the disappearance of the passport for the artists marks just another ebb in the overall flow of their piece; a flow that began with Nakamoto, coursed through their clandestine chats via a Tor networked browser and high security email, and now continues to trickle on while we wait in anticipation for the next chapter of the Nakamoto passport to reveal itself. In this respect, the anticipation of the passport is a poetic and unforeseen layer added to the significance of the piece: “Maybe it is even better [that the passport should not arrive]” Brout and Marion comment. “It’s like it was impossible to bring Nakamoto out of the digital world.”

If value is always formed by way of a social relation, then how do digital modes of sociality also deliver this effect? This becomes a particularly fraught question when considering that, as Anna Munster has written, the sociality that takes place on the internet can be understood as the interrelation of any number of subjectivities, both organic and inorganic. Brout and Marion’s ambivalence to the purloined passport highlights just such an expectation: “Here the lack of identity delivers a lot of value. Look at Snowden: journalists ask him more about his girlfriend than about his revelations. Making something as big as Bitcoin and staying perfectly anonymous? These are strong attacks to two of the most important issues of our societies: banks and privacy.” What their statement suggests is how a collective movement towards transgression, here seen as compounding maneuvers of avoidance of physical world boundaries and institutions, might hold within it the promise of its own set of value coordinates. As Brout and Marion further explain: “For us, Nakamoto is absolutely fascinating. The efforts he made to prevent himself from being turned into a product are incredible. Especially when you know the importance of [Bitcoin’s] creation, and that only a few men in the world are smart enough to create something like this. Adding to that the fact that Nakamoto is probably a millionaire, you have one of the only true contemporary myths, something hard to find credible even if it was just a fictional character in a movie. So this somewhat absurd attempt to create a proof of Nakamoto’s existence was, for us, an attempt to make a portrait of him, to put light on his figure. And, in some ways, a tribute.”

Brout and Marion mount a final probe into questions of value in their piece, Untitled SAS. Untitled SAS is the name for Brout and Marion’s corporation whose purpose and medium is to exist as a work of art. In France SAS means société par actions simplifée, and is the Anglophone equivalent of an LTD. SAS companies have shares that can be freely traded between shareholders. Untitled SAS, in Brout and Marion’s own words, “has no other purpose than to be a work of art: it won’t buy or sell anything, there won’t be employees, its existence is an end it itself. The share capital of the company is 1 Euro (the minimum), and we edited 10,000 shares owned by us (5,000 for each one). Everybody can freely buy and sell shares of this company.” Brout and Marion are clear: in no uncertain terms, “Untitled SAS is a work of art where the medium is a real company, and the corporate purpose of this company is simply to be a work of art.”

Untitled SAS is a tongue in cheek commentary on the situating of artworks as outside of the rational space of the market while still being subject to selective norms of economic behavior. Brout and Marion explain, “Untitled SASis obviously a metaphor for the art market, and the market in general: it is a true, fully legal, and functional speculation bubble. Companies usually try to create some concrete value, they are means. The art world has fewer rules than the regular market, the price of some artworks can radically change in few days without any logical reason: their intrinsic value is completely uncorrelated to their market value. We wanted to reproduce and play with these systems in the scale of an artwork.” At this level, what Brout and Marion uncover is further proof of the condition of the contemporary art period as Groys sees it: a time in which “mass artistic production [follows] an era of mass art consumption” and by extension “means that today’s artist lives and works primarily among art producers—not among art consumers.”7

Crucially, the effect of this condition is that contemporary professional artists “investigate and manifest mass art production, not elitist or mass art consumption.” This is the mode of art making precisely employed by Brout and Marion in the creation of Untitled SAS. It has the added effect, too, of creating an artwork that can exist outside the problem of taste and aesthetic attitude. Companies tend to eschew taste qualifications in favor of brand associations. Untitled SAS becomes readable as an artwork, as Untitled SAS, when the expectations and regulations of a nationally recognized business are made to butt up against the inconsistencies of the artworld as an economic sphere. The art object then becomes rather a means of accessing the overlapping paths of art and value as they are uniquely enabled to circulate in and out of the art & Capitalist markets.

* * *

Brout and Marion note that, “In our work we often use algorithms and generative ways to produce things, but here we wanted to something no machine can do, something hand-made, too, finally a simple and traditional work of art.” These kinds of generative technological processes and sorting algorithms have been central to many debates on how contemporary culture is absorbing the boon of big data: from ethical questions on predictive policing to dating apps and ride-hailing startups. As one Slate article posed the question in relation to Uber, these algorithms are more than just quick and efficient modes of labor—they are reflections of the marketplace themselves.

So what, then, might it mean that both values and services in the digital age are predicated on the power to sort and categorize, and that this power is ciphered through its own dynamic of social relations, but that in one scenario what emerges is a sphere of the valuable and in the other a software that asserts itself as benign and at the behest of an impartial, impersonal data? Perhaps the rationality of value and market circulation vis a vis the art object was always going to be a little too tricky to take on: too many exceptions, too many questions of subjectivity, taste, and judgment. But as the works exhibited for The Human Face of Cryptoeconomies might suggest the rationality of value and the products it chooses to incorporate is of high importance. If value works precisely because of the specific interrelating of social subjects then we can consider the realm of the digital as a concentrated form of such a relation.

Against this we must consider the new subject that is produced and addressed by the intersecting of these discussions. Spaulding and Demby make the case that, that “Art under capitalism is a good model of the freedom that posits the subject as an abstract bundle of legal rights assuring formal equality while ignoring a material reality determined by other forms of systematic inequality.”8 Karen Gregory, in The Datalogical Turn, writes, “In the case of personal data, it is not the details of that data or a single digital trail that are important, it is rather the relationship of the emergent attitudes of digital trails en mass that allow for both the broadly sweeping and the particularised modes of affective measure and control. Big data doesn’t care about ‘you’ so much as the bits of seemingly random information that bodies generate or that they leave as a data trail”.

The works of Brout and Marion exhibited at the Human Face of Crypotoeconomies exhibition places the intimacy of the body front and center. They speak to the shadow and trace of the body by appropriating the paths of the faceless, or by giving a face to the man (or entity) without a body, to becoming the human face of the market player par excellence by inserting themselves into a solipsistic art corporation. Brout and Marion’s practice understands that while value may not be an all-penetrating miasma, this is not also to say that the effect of value is not still inscribed on the flesh of each and all, organic or not.

1 Demby, “Art, Value, and the Freedom Fetish | Mute.”

2 Ibid.

3 Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” 543.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 “Who Is Satoshi Nakamoto?”

7 Groys, “Art and Money.”

8 Ibid.

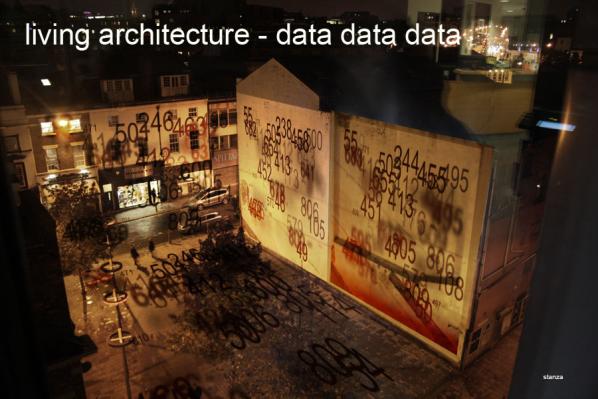

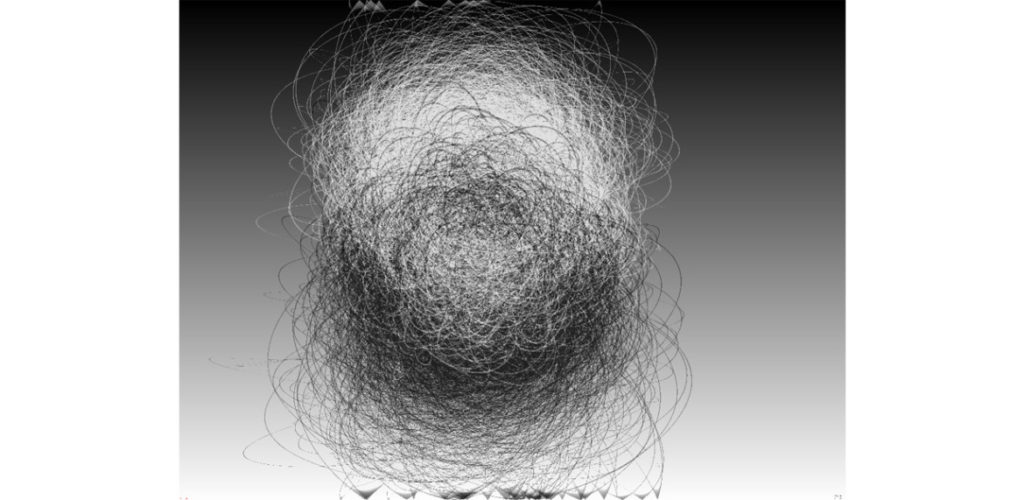

Stanza is an internationally recognised artist who has been exhibiting worldwide since 1984. He has won so many prizes you’d have trouble fitting them all on one mantlepiece. He has exhibited over fifty exhibitions globally and is an expert in arts technology, CCTV, online networks, touch screens, environmental sensors, and interaction. His artworks examine artistic and technical perspectives, within the contexts of architecture, data spaces and online environments.

Recurring themes throughout his career include the urban landscape, surveillance culture, privacy and alienation in the city. Stanza is interested in the patterns we leave behind, and real time networked events, that are usually re-imagined and sourced for information. He uses multiple new technologies so to create distances between real time, multi point perspectives that emphasis a new visual space. The purpose of this is to communicate feelings and emotions that we encounter daily which impact on our lives and which are outside our control.

Much of his work has centered on the idea of the city as a display system and various projects have been made using live data, the use of live data in architectural space, and how it can be made into meaningful representations. See Publicity, Robotica, Sensity, as well as a whole series of work manipulating real time CCTV data to making artworks with them: See, Velocity, Authenticity, Urban Generation. These works reform the data, work with the idea of bringing data from outside into the inside, and then present it back out again in open ended systems where the public is often engaged in or directly embedded in the artwork. Interactive and visually appealing, his style also maintains the substantive power through multi-facetted content.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Stanza: I don’t really get inspiration from the “who” question, I prefer the “what” and “why” questions. As a professional artist I look at loads of art so to understand what art is and can be, and it’s always an ever changing and fluid response. I also spend a lot of time ignoring stuff and material; (focused ignoring) because it has become harder and harder to see though the fog; the noise of it all. Maybe it’s better to think of a working model for inspiration, Andy Warhol had one. Just make the work. That’s what I do. I am not a part time artist in academia or an artist with another job, I’ve done this for the last thirty years, inspired by and in response to the world around me.

This dogmatic commitment to my work comes from my believes that the system you have to trust and invest in yourself. Inspiration, quite literally is everything all around you all at once, all at the same time, moment by moment. This is what inspires my work and it influences the creation of real time information flows, and works in parallel realities. It allows me to stand back at a distance and work with complex data sets while at the same time making meaning from them. Forming data into a shape, because this confluence might inspire a repositioning of thought and values while at the same time unlocking a hidden meaning to enable the viewer to feel and experience something new or to do something creative with the results.

MG: How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

S: There’s a saying be careful what you wish for. If one reverses this then it could be wish for what you want and need. Influence is problematic because it’s both negative and positive. The idea of influence seems causal, but my own practise isn’t based on influence but in research into certain themes. This enables me to get into both sides of particular questions or debate, so to frame the work I make. Works like these have been inspired by this focus…

The Singing Trees, focus in the invisible things and the environment http://stanza.co.uk/tree/index.html

MG: How different is your work from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

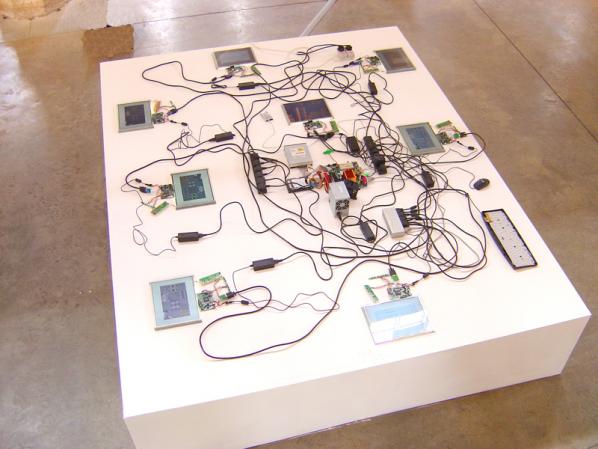

S: I have been researching smart cites, urbanisn, and have collected ‘big data’ since 2004. I have been building my own wireless sensor network. This eventually manifested itself in an artwork called Capacities in 2010 which then influenced all the others in the series until it now has this form.

Capacities: Life In The Emergent City, captures the changes over time in the environment (city) and represents the changing life and complexity of space as an emergent artwork

http://stanza.co.uk/capacities/index.html

Which led to…

The Nemesis Machine- From Metropolis to Megalopolis to Ecumenopolis.

“A Mini, Mechanical Metropolis Runs On Real-Time Urban Data. The artwork captures the changes over time in the environment (city) and represents the changing life and complexity of space as an emergent artwork. The artwork explores new ways of thinking about life, emergence and interaction within public space. The project uses environmental monitoring technologies and security based technologies, to question audiences’ experiences of real time events and create visualizations of life as it unfolds. The installation goes beyond simple single user interaction to monitor and survey in real time the whole city and entirely represent the complexities of the real time city as a shifting morphing complex system.

The data and their interactions – that is, the events occurring in the environment that surrounds and envelops the installation – are translated into the force that brings the electronic city to life by causing movement and change – that is, new events and actions – to occur. In this way the city performs itself in real time through its physical avatar or electronic double: The city performs itself through an-other city. Cause and effect become apparent in a discreet, intuitive manner, when certain events that occur in the real city cause certain other events to occur in its completely different, but seamlessly incorporated, double. The avatar city is not only controlled by the real city in terms of its function and operation, but also utterly dependent upon it for its existence.”

MG: Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

S: It’s the museum I would like to change or engage with. It seems that anything and everything will end up in the museum. We have become the museum. We are the sum of our collections catalogs and archives. Since the current trend is for public engagement we will see a mix of these new technologies aiding and abetting this and various dialogues.

Therefore these questions need to be raised more vocally. How do visitors interact with each other and artworks? How do visitors behave in public space and what patterns or communities do they form. Can these outputs reshape our experience of public space and the art?

So, new immersive technologies could be used to investigate how visitors interact with art works, with each other and what impact their experiences have in forming new user interactions within public space. This space could be made more social and lead to new real time artworks based on visitor interaction and new visualizations of the gallery space based on gathered data.

Artists used to occupy specific issues but now there aren’t many topics artists haven’t engaged in or reached out to. The issues that will resonate will be the ones closest to the issue of the day…. and, they will be economics, the environment and migration. Because of this I would like to less focus on public engagement spectacle or entertainment and more on the quality and public engagement rooted in intellectual rigour.

Technology affords new ways of working with audiences and curators as participants in artworks. The concept of the exhibition as an active site for experimentation and collaboration between curators, artists and audiences prefigures a general cultural movement towards the centrality of experience and away from the reification of the object.

However, how audience activities and movements can be used as the subject of new artwork as well as modify engagement with existing collections is a cultural and technological challenge.

SeePublic Domain: You Are My Property, My Data, My Art, My Love.

The Public Domain Series involves using live CCTV systems that are already installed then using these cameras to enhance gallery space and the audiences experience of the gallery. http://stanza.co.uk/public_domain_outside/index.html

Visitors to a Gallery – referential self, embedded. Stanza uses a live CCTV system inside an art gallery to create a responsive mediated architecture. Anyone in any of the galleries and all spaces in the building can appear inside the artwork at any time.

http://stanza.co.uk/cctv_web/index.html

The social challenge within urban space is one I like to play with. In The Binary Graffiti Club, is a project I set up to try and work in this area. The Binary Graffiti Club are invited members of the public at each location for each event; they are given the hoodie to keep as thanks for their participation and contribution. The Binary Graffiti Club set off across the city and create artworks.

http://stanza.co.uk/binary_club/index.html

“Youths dressed in black hoodies swarmed the historic city streets of Lincoln during Frequency Festival 2013, their backs emblazoned with bold white digits, the zeros and ones. Their ominous presence was marked with a series of binary code graff-tags on official buildings throughout the city; messages of insurrection for a digital cult now active among us or analogue reminders of the digital soup of signals we wade through on a daily basis? There’s an engaging playfulness and an aesthetic pleasure to Stanza’s work that pays rewards on deeper investigation. His urban interventions remind us of the invisible occupation of the cyberspace around us and encourages us to ask whose hand manipulates these systems of control.” Barry Hale, Festival Co-Director of Frequency Festival 2013: Stanza: Timescapes/Binary Graffiti Club.

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

The invention of the toothpaste tube caused a revolution in painting.

The greatest discovery of the age was that the world is full of atoms.

Doing many small things instead one on big thing.

We seam to victimise out children we give them ASBO’S and anti social behaviour orders. For a while I wanted one. They actually give you a certificate like rockers, mods punks etc. The hoodie is a symbol of youth culture as well as being anti social. My new artwork the Reader and the idea of reading books and being anti-social led to this project.

The Reader is a large six foot sculpture of the artist Stanza wearing a hoodie reading a book. The artwork is a metaphor for the engagement of reading in the digital age. The sculpture acts as a focal point for community and public engagement and has taken over one year to make and design; it has been commissioned to act as a focal point for the identity of the library. The reader reads all the books published since 1953 inside a data body sculpture. http://stanza.co.uk/TheReader_web/

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and or social change?

S: Make work, make more work, and remember nothing lasts forever except true love.

Re: Art, Study it

Re: Technology. Learn it

Re: Social change . Be part of it.

MG: Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

Yes the Books…

The Bible The Quran And The Torah.

Because…they are the most influential books ever written and have guided the lives of billions so it’s a good idea to have had a read… at least “view” them.

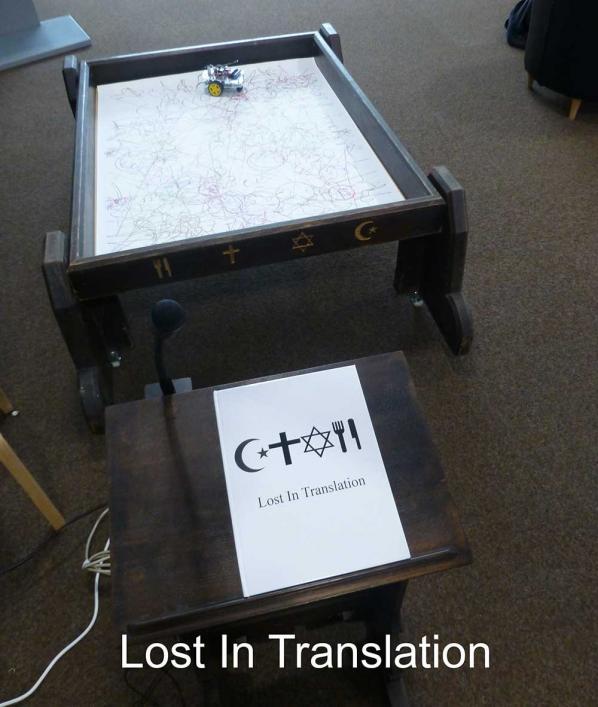

See…

Lost in Translation. This custom made robot responds to a series of texts and makes drawings unique to each reader. The work questions not only the meaning and interpretation of text but just who controls our understanding of the outputs and indeed what is Lost In Translation. This is a very playful user friendly work and actively engages the audience not only to think about the text but the meaning of how automation and networked technology is changing the control of understanding. http://stanza.co.uk/lost_in_translation/

Thank you…

The negotiation of the commons takes place in two distinct realms that are increasingly reaching into and shaping one another: the long history of the landscape commons both in cities and in the countryside, and across digital networks. In both realms we find the continued project of the enclosures, appropriating forms of collectively-created use value and converting it, wherever possible, into exchange value. In this conversation Ruth Catlow and Tim Waterman discuss the ‘Reading the Commons’ project together with Furtherfield’s work on understanding the commons.

Ruth Catlow is an artist and co-founder co-director of Furtherfield. Tim Waterman is a landscape architectural and urban theorist and critic at the University of Greenwich and Research Associate for Landscape and Commons at Furtherfield.

*