On the 7th September, the Disruption Network Lab opened its 14th conference in Berlin entitled “INFILTRATION: Challenging Supremacism“. The two-day-event was a journey inside right wing extremism and supremacist ideology to provoke direct change, second appointment of the Misinformation Ecosystems series that began in May. In the Kunstquartier Bethanien journalists, activists, researchers, and infiltrators had the chance to discuss the increasing presence of movements that want to oppose immigration, multiculturalism and political correctness, sharing their experiences and proposing a constructive critical approach, based on the motivation of understanding the current debates in society as well as transforming mere opposition into a concrete path for inspirational change.

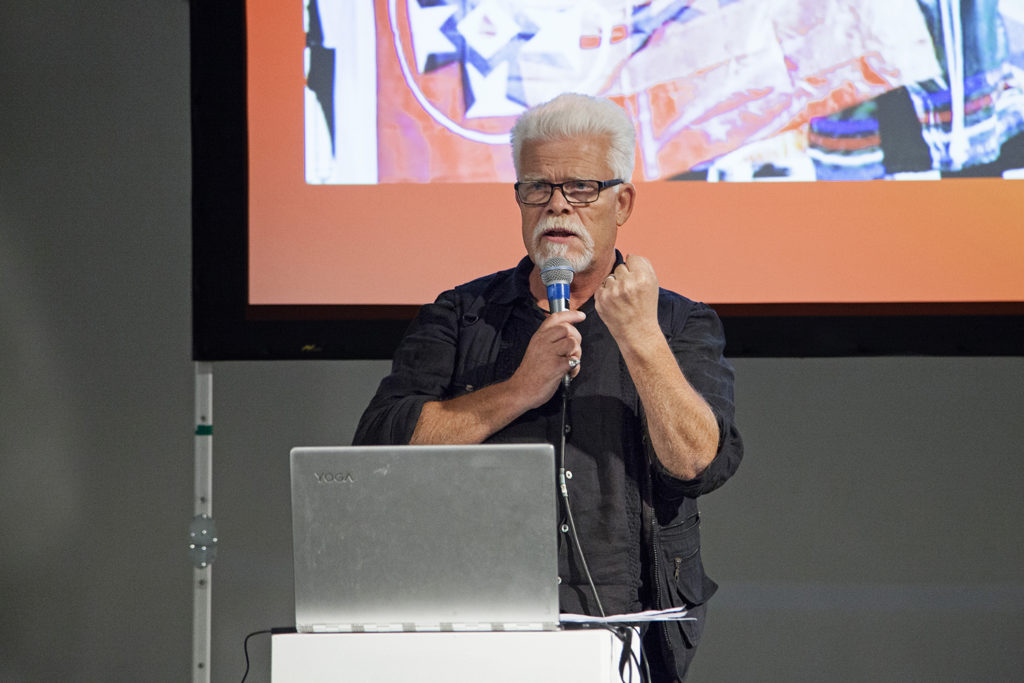

“How can you hate me when you don’t even know me?” With this question Daryl Davis tried to crumble the wall of ignorance and fear that he believes to be the basis of racial hatred. This 65 year-old author, activist and blues man, who played for decades with Chuck Barry, Jerry Lee Lewis and B.B. King, has spent 35 years studying race relations and befriending members of the Ku Klux Klan to turn them away from racism. In the context of increased supremacist ideologies and right-wing extremism, the Disruption Network Lab invited Davis to speak about racism and his interactions with individuals holding racist beliefs.

Growing up, Davis lived a privileged life as the son of a U.S. Foreign Service officer, travelling around the world and studying in an international context surrounded by children of other Foreign Service workers. His first shocking encounter with racism occurred when he was 10 years old in a 1968 Massachusetts. He was marching in a parade carrying the US- flag in front of his scouting group as people yelled racial epithets and threw rocks and bottles at him. His parents later explained that those people were targeting just him because of the color of his skin. Someone who knew absolutely nothing about his person and his life wanted to inflict pain upon him for no other reason than that. Because of this hateful reaction from so many white spectators along the route, Davis started wondering the fatidic question.

Ignorance causes fear and obviously the theses of supremacists and racist groups are built on these two components. Many years ago Davis decided to sit with them and listen to their point of view, contradicting their falsehoods using dialogue. Davis is convinced that if we do not fight ignorance it will escalate to destruction, “ignorance breeds fear; fear breeds hatred; hatred breeds destruction” as he previously stated. So, when someone says he thinks white people are superior, Daryl faces them and answers: “we are equal.” On this basis, Davis befriended hundreds of KKK-members and convinced them to rethink their choices. According to the media, he has persuaded more than two hundred of them to throw away their hoods and robes, their stereotypes and beliefs. His activity became national news as he befriended the KKK-member Roger Kelly and CNN broadcasted a story on their unusual relationship. When they first met, Kelly was “Maryland’s Grand Dragon”. Kelly didn’t know Davis was a black man and agreed to meet him. During their first meeting he spewed a lot of stereotypes, but – as Davis narrates – by the end of the evening they could agree on a few topics. The Grand Dragon told Davis they would never agree on racial issues; he said his Klan views on race and segregation were “cemented.” They continued to meet and converse about difficult and controversial matters for a long period: Kelly would attend Davis’s house and Davis would go to KKK-rallies. It took a few years but Kelly’s cemented beliefs got weaker, until he decided to quit the Klan and run for local elections. He had meanwhile become “Imperial Wizard” – which means national leader of the Klan.

During his key note Davis explained that his search for the answer to his question began one night in 1983. After having played in a country music bar a white man approached him and offered him a drink. The man later told him that it was the first time he had ever sat down and had a drink with a black man because he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Davis thought at first that the man was joking, but he wasn’t. The bluesman decided to talk to him, focusing on the fact that “they are just human beings,” he says “I respect these people when they sit, talk and listen. It’s just about difference of opinion. If you talk with them you can find things in common.” Someone might disagree with Daryl Davis that Fascism, Racism, Supremacism cannot be considered opinions, that they are crimes and that normalizing their cult is dangerous. But Davis prefers dialogue to posturing and fights. Davis believes in addressing ignorance through communication and education, to ease fear and prevent destruction. His efforts at dialogue are represented by his collection of hoods and robes from former Klan members he has befriended over time. Davis thinks that society should give these people a chance to express their views publicly to challenge them and force them to actively listen to someone else, dialoguing, to passively learn something. Many of them are anti-Semitic, neo-Nazi, Holocaust-denial and racist white supremacist, but he sees them mostly as victims of ignorance, fearing something that they just do not know. For these reasons he talks with them trying to overcome their prejudices. “Always keep the lines of communication with your antagonist open, because when you’re talking, you’re not fighting.”

Davis offers an extreme example of breaking down stereotypes to change the minds of white supremacists. It can be deeply understood only in the context of his US-American background and cultural formation. His keynote speech tended to get soaked in clichés, enriched by several “I am proud of my country” and “my country is great.” Maybe it is just a way to subtract right winged racists the monopoly over the patriotic discourse, through a moderate and gentle approach, to disrupt their one-way narrative, that conflates patriotism with rabid nationalism, showing them that he has traits in common with them. All in all his underlying convincement is that racism comes from a lack of personal knowledge of the African American experience and history, for example in music, and from a lack of personal relationships of a certain part of the white community with human beings that are not white. He thinks that by befriending ignorant racists they could relent, change their minds, have a change of heart and learn how to respect others. Davis is conscious about the fact that such an uncommon approach can be considered, at least, controversial. Many disapprove of it, pointing out that he is offering them a prominent stage in the national and international spotlight.

Davis´ activity can also be dangerous. In the past thirty years he has been attacked because of what he does. However, he is not afraid of the Klan or of racist groups. He has cultural tools to face dialectics, he has a strong identity and doesn´t want to fight against someone´s else idea of identity. On the contrary he is convinced that people of all backgrounds shall come together, getting along without losing their sense of identity or individualistic dimension, as no one shall be forced to accept an idea. Matt Ornstein has directed a documentary about Daryl Davis, that the Disruption Network Lab decided to screen during the third day of this 14th Conference. Entitled “Accidental Courtesy: Daryl Davis, Race and America.”

In Germany, individuals and organizations have been mobilizing to prevent the access of neo-Nazi to public platforms and media to spread Negationism and racist propaganda, in a collective lucid reasoning. Dialoguing with neo-Nazis, allowing them to exhibit symbols and to represent reactionary bigotry and hatred as something normal is not accepted by many people in Germany and the audience of the Conference showed reservations about Davis ‘words. Davis replied that his approach pays back. To those who tell him that he is giving racist and violent groups a platform to be normalized and to be part of the public discourse, he reminds them that most of those KKK-members that he approached decided afterwards to quit the group. It took him courage and dedication, he went to KKK-rallies, listened to their hymns, watched them set on fire giant wooden crosses during liturgical rites, witnessing moments of collective frenzy, delirium and hatred.

The documentary shows the efforts to dialogue with representatives from the movement Black Lives Matter too, that sadly ended up in a moment of misunderstanding and dramatic confrontation. Davis and Black Lives Matter have met again and have found a way to work together, going the same way approaching the issue of racism and discrimination with two alternative techniques, that are not mutually exclusive. However, Davis approach is markedly distant from this grassroots movement that organizes demonstrations and protests.

The audience of the 14th DNL Conference challenged Daryl Davis as his approach “we are all human beings” looks fragile in days of uncertainties, when extreme right movements are gaining consensus upon lies and discrimination. Inevitably, the debate after Davis ‘speech focused on the cultural shift represented by Donald Trump´s election and what came after that on a global scale. Davis said that in his opinion what is happening works as a bucket of cold water, that wakes people up and makes them engage and fight for change, reacting with indignation. Davis explained that in his opinion the #MeToo campaign came out as a positive consequence to Donald Trump´s election. “Obama was not elected by black people, who are all in all 12% of the US-population. Things change if we dialogue together, creating the bases for that change. In this way we can accomplish things that just few decades ago were thought to be unachievable.”

The panel of September the 7th represented a cross-section of the research being conducted by journalists, researchers and artists currently working on extreme-right movements and alt-right narrative. By accessing mainstream parties and connecting to moderate-leaning voters, right wing extremists have managed to exercise a significant influence on social and political discourse with an impact that is increasingly visible in Europe. The speakers on this first day of the Conference reported about their experiences with a focus on what is happening in their countries of origin: Sweden, Germany and Slovenia. Interconnecting three methodologies of provoking critical reflection within right-wing political groups, the panel reflected on possible strategies of cultural and political change that go beyond mere opposition.

Recalling all this, the moderator Christina Lee, Head of Ambassador Program and Hostwriter, introduced Mattias Gardell, first panelist of the day, Swedish Professor of comparative religion at Uppsala University, who dedicated part of his studies to religious extremism and religious racism, addressing groups such as the Nation of Islam and its connections to the KKK and other American racist activists, to focus than on the rise of neo-Paganism and its meaning for the radical right. Among his publications, a book on his encounters with Petter Mangs, “the most effective and successful racist serial killer” Sweden has ever encountered, as he writes, and recent analyses of the “lonely wolf” tactic of militant action and groups from the extreme right and the radical Islamism, that are operating under the radar, to avoid being detected and blocked by authorities.

At the time of the Conference, parliamentary elections were about to take place in Sweden. The country was then set for political uncertainty after a tight vote where the far right and other small parties made gains at the expense of traditional big parties. Gardell reported that in Sweden the political and social climate of intolerance has risen. More than half of the mosques have been assaulted or set on fire and minorities are continuously under threat. During his speech he focused on how new radical nationalist parties and movements are investing in narratives built on positive images of love and community, nostalgic sentiments and promises to return the once good society and its original harmony. They are nationalist and ‘identitarian’ groups (as they call themselves), from different nations and united under their belief in separation on the base of national identities. They often portray themselves as common citizens, worried about the vanishing of their country and identity due to a program of multicultural globalism that aims at substituting national identities and people by means of a white genocide: a constant sense of paranoia, that Gardell also perceives in a country like Sweden, where the economy is flourishing, and inequalities hit mostly migrants and non-white population.

These groups work to spread the idea of a “white nostalgia”, a rhetorical discourse based on their efforts to reiterate a rosy, but hazy period, when life was better for the white native population of a certain territory. They ambiguously evoke a moment in history, that has probably never existed, at which national identities were free from external contaminations and people were wealthy sovereign citizens. This propaganda emerges into a multi-faced production in music, film and visual arts. It is not the “angry white men” image alone that can contain such a new fragmented and liquid reality; in fact, explained Gardell, the opposite is true. They often offer a narrative, that appears to be built on love rather than on hate. Love for their nation, love for their hypothetical race, for their selected groups and communities. It is not an imaginary love, it is a deep true feeling that they feel and upon which they construct their sense of collectivity.

Gardell underlined the importance of studying every-day-Fascism, focusing on its essence made up of ordinary individuals that like football, accompany children to school, listen to music and therefore have things in common with their neighbors and colleagues to whom they might appear as moderate people. “You can’t defeat national socialism with garlic. You have to face the fact that Fascism has been supported by millions of ordinary people who considered themselves to be good and decent citizens” he said. It is necessary to unveil the false representation of a political view, evoked through posters of blonde children and pictures of smiling women, that are designed to embody a bright future and a safe homeland. It is necessary to oppose the program of selective love and restricted solidarity that extreme right and nationalist groups promote. Therefore, says Gardell, we need to challenge those representations of love for nation, homeland and family built on a language that is impressive-sounding but not meaningful or sincere at all. And not just because “white nostalgia” is a fictional invention, but – more important – because on the collective and public sphere, love and solidarity are meaningful only if they are universal and express the value of equality unless they are just synonyms for privilege from which just few people can benefit.

At the moment, ultra-nationalist and radical right parties assembling the new political scene, appear to be able to influence traditional parties and vast parts of the population using love as a political weapon, affecting the social and political landscape in many countries, succeeding in making those traditional parties copy their agenda. Their recurrent themes exploit desire for individual social retribution, the tradition of a misogynic masculinity, the enhancement of self-government tendencies and isolation in opposition to openness and solidarity. A rhetoric that exploits the presence of nonwhite minorities and economic instability of this late capitalism, creating hateful propaganda. An intense online activity of manipulation supports the point of view of these ultra-nationalists. As the DNL Conference “Hate News” (May 2018) showed, online facts can become irrelevant against a torrent of abuse, memes and hate.

Online and offline, right extremists can easily find supporters in isolated realities, in the countryside or in close web-communities. Consequently, it is important to act locally and be focused, disrupting their ability to contaminate small groups. Young people are still intrigued by the gruesome and brutal part of the black metal scene, by the fringes of anarcho-fascists and by hooligans, feeding into an international network of neo-Nazi black labels and groups. But there are now also presentable faces, new political formations with attractive slogans supported by glossy music bands and influencers that are building a narrative of love. Mattias Gardell concluded his intervention saying that these groups are currently on the rise throughout Europe, whilst a storm of Fascism is coming again, widely, to hurt exposed individuals and communities, as it is already doing. He is disillusioned and reminded the audience of the Disruption Network Lab that it is necessary to focus and act to defeat it, knowing that it will cause blood.

The analyses of Mattias Gardell introduced topics covered by the second panelist of the day Richard Gebhardt, political scientist and journalist, who gave an insight into Hooliganism based on his direct researches from the last four years in Germany and England, where the Football Lad’s Alliance established itself as a complex reality. He focused on the reasons that pushed this violent collective to become a political movement, connected in Germany to the foundation of Pegida (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West), and the increasing popularity of the parliamentary party AfD (Alternative for Germany), which is today – according to opinion polls and surveys – the second biggest political formation in Germany.

Gebhardt’s intervention began indeed with a quotation by the leader of the alt-right party Alternative for Germany: “We will hunt them down.” The parliament member was suggesting that the new members of parliament from his political formation would use their new powers to hold Angela Merkel’s government to account for its refugee policies “to reclaim their country and people.”

At the time of the Conference only a few days had passed since right-wing extremist thugs and neo-Nazis organized an assault on foreigners in the German city of Chemnitz on the 26th and 27th of August, in reaction to a murder that happened a few days before. It was a shocking moment for many Germans. However, in the following days politicians and members of the German government have tried to downplay the events, showing that big moderate parties tend to favor a certain kind of narration. Far-right violence in Germany has indeed seen a sharp rise in the last period. In this context the guest talked about the group “Hooligans gegen Salafisten” also known as HoGeSa (Hooligans against Salafists) and its origins.

On October 26, 2014, in Cologne the HoGeSa organized its first rally against Salafism. The number of participants can be ultimately estimated around 4.000 people, violent hooligans, who threw stones, bottles and firecrackers. They gathered in Cologne Central Station, with several speakers and live music, and to later march through the streets of Cologne. Xenophobic and neo-Nazi slogans were frequent, and so was the Hitler salute. During the riots dozens of police officers were injured and several police cars were damaged. Police were surprised by the inclination to excessive and unpredictable use of force. In that year thousands of refugees were traveling to Germany from conflict-ridden Middle Eastern countries and the HoGeSa was already targeting them.

In the days immediately after the demonstration, leading German politicians and prominent jurists sought to give a lighter representation of the events. The first official comments to the HoGeSa demonstration were not referring to it as a neo-Nazi demonstration, stressing the fact that hooligans are “for the most part politically indifferent” and that “they are not political but antisocial. They meet just to fight and drink.” The motto “Fußball ist Fußball und Politik bleibt Politik“ (football is football, politics stays politics) was repeated often but did not sound convincing at all. The Hooligans gegen Salafisten represented undeniably a new network of neo-Nazis, that had joined forces with football hooligans, nationalists and other right-wing extremists. Thousands of football supporters appeared to have left their football clubs of choice behind in favor of uniting against a common enemy: Islam. They chose their name HoGeSa hoping to receive popular support by recalling the fight against Islamist extremists.

Nonetheless, not every hooligan is a neo-Nazi. Press reported that in Hannover, for example, hooligans and ultras distanced themselves from the demonstration of HoGeSa and non-fascist football Ultras and that groups in Aachen, Dortmund, Duisburg, Braunschweig and Düsseldorf say they have been threatened, chased down and beaten by these Nazi-hooligans. Gebhardt suggested to the audience of the Conference a book, “Among the Thugs” by Bill Buford, to better understand the dynamics behind hooliganism. The book follows the adventures of Bill, an American writer in England, as he explores the world of soccer hooligans and “the lads”. Setting himself the task of defining why young men in England riot and pillage in the name of sports fandom, Bill travels deep into a culture of violence both horrific and hilarious.

Gebhardt portrayed these extreme right-wing rioters from HoGeSa as men, claiming to be equally distant from conservative and progressive parties, who want to be seen just as football supporters that are not carrying any ideological content, neither that of the Left nor of the Right. However, the nonpolitical hooligan is a myth: they are the heirs of a fascist tradition based on prevarication, arrogance and violence, that plays with the aestheticization of fighting and war, the glorification of militarism and pseudo-heroism. They are not worried citizens, they are thugs “ready for a civil war.” They claim to speak for the silent majority of their community, defending their country and their people. The work of Gebhardt can be seen in a documentary “Inside HoGeSa” (2018) and in his articles online.

The last guest of Friday’s Conference was a member of the project ”Janez Janša, Janez Janša and Janez Janša,” who run for office in Slovenia at the last 2018 elections, confronting the leader of the conservative Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS), and former Prime Minister, Janez Janša. “Old names, new faces” was their motto.

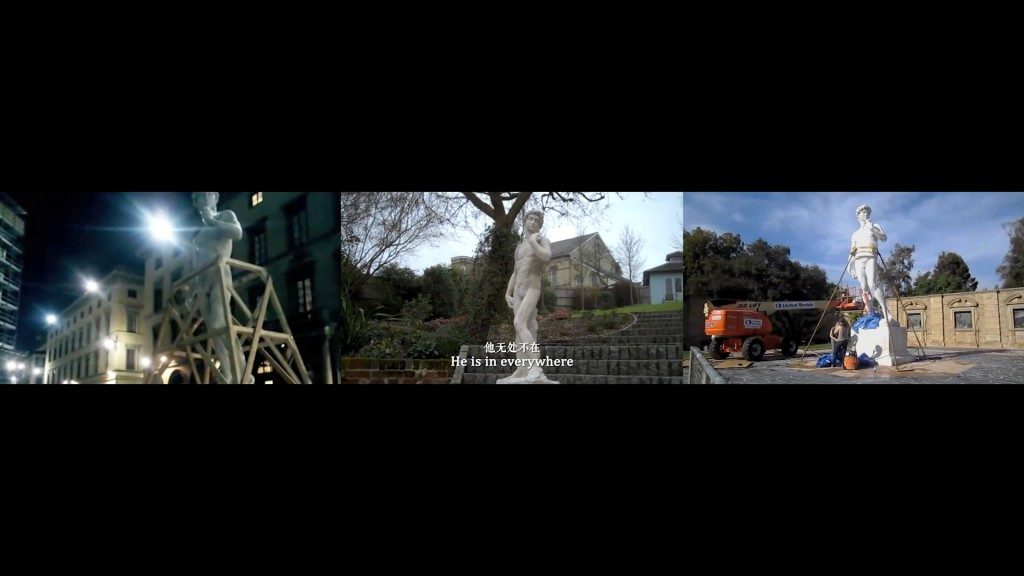

In 2007 three artists decided to legally change their name to Janez Janša and joined the right conservative Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS, which was originally a moderate political formation). Janez Janša is also the name of the former President of Slovenia. All of a sudden, there were at least four Janez Janšas in the country: the three artists and the politician famous for his aggressiveness and contentiousness with the opposition and anyone who dares to criticize his choices. At the time President Janša made a public statement about the artists and pro-government media started to comment on their name change criticising their “politicized art”. The activity inside the SDS of the artists served to explore the bureaucratic and political systems of their home country. Their work of investigation is instead much more complex. It reveals how the perceptual influence of a name can interfere with social dynamics. Both on a collective and subjective dimension, they researched the meaning of identity and sectioned how their private life was affected by such name change. They proved that names are just a convention, an instrument, but with a relevant role. Janša remembered as an example that the Slovenian Democratic Party, despite this name, turned into a radical, right and conservative party between 2000 and 2005. Nowadays it is engaged in anti-migrant rhetoric and populist right-wing propaganda.

The artist illustrated how, in the last decade, the Janšas responded with art, cleverness and culture to campaigns of hate and propaganda, an approach that is the base for their political interventions. Their experience was the subject of the documentary from 2012, “My Name Is Janez Janša” and is internationally known. Artists and academics are still pondering about the meaning of the Janez Janšas experience, political critique, art work, activism, provocation or never-ending joke.

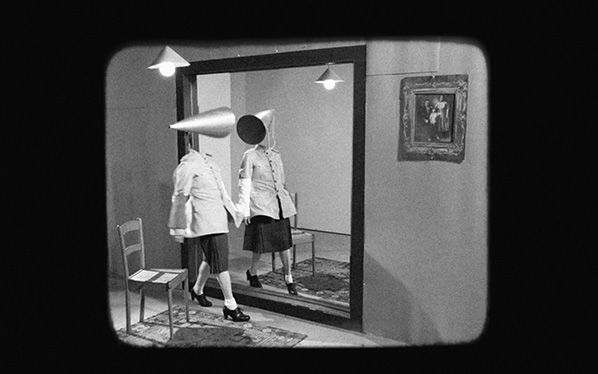

During the conclusive debate all panellists agreed that the world they have been in touch with and that they described in the Conference is mostly a world of men. Women are generally present as an accompaniment and/or an accessory. It is certainly a characteristic of Fascism, described in literature and art, as designated in the book “Male Fantasy” by Klaus Theweleit, where the author talks about the fantasies that preoccupied a group of men who played a crucial role in the rise of Nazism. Proto-fascists seeking out and reconstructing their images of women. Another aspect that all three guests agreed on, is the fact that individuals are massively not voting or taking part in public life, since they are increasingly distrustful of traditional media and politicians. European moderate politicians have on the other side the responsibility of a systematic dismantlement of social rights, they justified and supported an unequal economic system of wealth distribution for too many years. Now, scandals and arrogance in public and institutional life do not seem to affect the popularity of extreme right parties, that are ridiculing the excess of fair play and the interests of those moderate politicians.

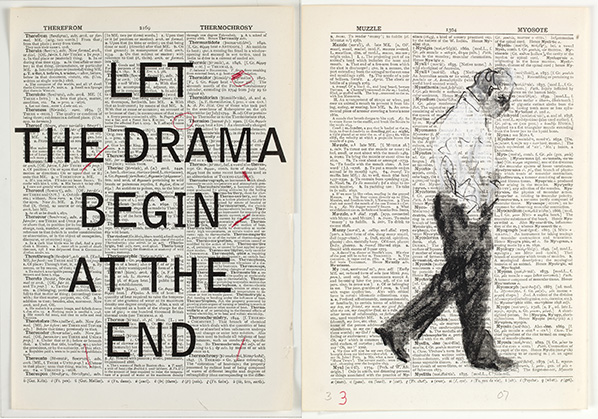

Focusing on new strategies to directly provoke change, the Conference on the 8th of September began with a performative conversation between Stewart Home (artist, filmmaker, writer, and activist from London), and Florian Cramer, (reader in 21st Century Visual Culture at Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam), moderated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, artistic director of the Disruption Network Lab. The universe of the extreme-right seems to have embraced a path of transgression, arrogance and nonconformity, employed to suggest that its members are holders of a new alternative approach in cultural, political and social criticism. What comes out from such a wave of counterculture is an articulated patchwork that flirts with violence, discrimination and authoritarism.

Bazzichelli asked the audience to question the nowadays extreme right self-definition of their political offer as an “alternative,” considering that the issue of transgression and counterculture has been widely developed by academic and artistic Left, and that experimentation, theorisation and political antagonism have been growing together in the left-leaning universe. In such a perspective, “working on something alternative” – explained Bazzichelli – is supposed to be synonymous with creating a strong criticism of media and society, through political engagement, art and intellectual efforts. An alternative that could enhance a positive, constructive contribution in the collective socio-economic discourse. Today, words like “infowar” and “alternative” tend instead to be associated with a far-right countercultural chaotic production. On this basis, Bazzichelli introduced the lecture by Stewart Home and Florian Cramer, that investigated if and to which extent it is possible to affirm that ideas and values driven from the Left are now reclaimed and distorted in an extreme-right alternative narrative.

In an historical excursus on art, literature and subcultures, the two speakers focused on the 1970s-1990s counter-cultural currents that used radical performance, viral communication and media hoaxes and examined the degree to which they may be seen as playbooks for the info warfare of the contemporary extreme right. With their presentation they suggested that it is improper to state that the alt-right has now occupied established leftist countercultural territories. There have been several examples of a parallel development and interpenetration of very opposite points of view over time. Tommaso Marinetti, father of Futurism and its Manifesto about “War, the World’s Only Hygiene,” mixing anarchist rebellion and violent reaction became then a fervent supporter of the Italian Fascism, that glorified the new futuristic approach. However, Futurism means also sound poetry, since discordant sound had a vital role in Futurist art and politics; an experience that developed into the noise movement with an influence that reached post-industrial musicians and further.

Cramer remembered that Futurism represents also an avant-garde and counterculture from the 1900s, that had similarities with Dadaism. In fact, though Dadaism was anti-war and antibourgeois, they shared a spirit of mockery and provocative performances, mixing distant genres and a massive use of communication, experimental media and magazines. Always considering the beginning of the 20th Century, the lecturers recalled the production of the painter Hugo Höppener Fidus, expression of the Life Reform Movement, linked both to the left- and the right-leaning political views, that strongly influenced Hitler and Nazism, showing roots of an alternative counterculture that went both into the political extreme right and left.

In the 1970s and 1980s, in subcultural production and artistic performances it was frequent the use of fascist symbols as provocation and transgression, for example in the punk scene, which ranged notoriously from left wing to right wing views as pseudo-fascist camp in post-punk culture turn into actual Fascism. A conscious ambiguity, part of experimentation, that – particularly in the U.S. – meant also leaving space to things that were in contrast to each other. In the context of US underground culture, the speakers mentioned publications like those from Re/Search “Pranks!” on the subject of pranks, obscure music and films, industrial culture, and many other experimental topics. Pranks were intended as a way of visionary media manipulation and reality hacking. Among the contributors, you could find artists from the industrial movement, like the controversial Peter Sotos and Boyde Rice, who became today established part of right-winged countercultural movement.

Talking about the present, Cramer and Home also mentioned Casa Pound, a neofascist-squat and political formation from Rome, that adopted the experience described by the anarchist writer Hakim Bey of the “temporary autonomous zones,” that redefined the psychogeographical nooks of autonomy – as well as appropriated the name of Ezra Pound, a member of the early modernist poetry movement.

All this suggests that the so-called alt-right has probably not hijacked counterculture, by for example deploying tactics of subversive humour and transgression or through cultural appropriation, since there is a whole history of grey zones and presence of both extreme right and left in avant-garde and in countercultures, and there were overlooked fascist undertones in the various libertarian ideologies that flourished in the underground. Home and Cramer reminded their common experience in the Luther Blissett project, based on a collective pseudonym used by several artists, performers, activists and squatter collectives in the nineties. The possibility to perform anonymously under a pseudonym gave birth to a mixed production, with undefined borders, in few cases expression of reactionary drives. An experience that we can easily reconnect to the development of 4chan, the English-language imageboard very important for the early stage of Anonymous, that today is very popular among the members of the Alt–Right scene,

Cramer illustrated so how Libertarianism can sometimes flip into a reactionary ideology. The same can be for Anarchism (with the Anarcho-Capitalism) and Cyberlibertarianism, just like for the subcultures. In the Chaos Computer Club – explained Cramer – there is a strong cyberlibertarian component, but we might find also grey zones where a minority of extreme-right can find ways to express itself. Spores of extreme-right and fascist-anarchical degeneration can so be found in the activities of political and art collectives from the Left and, in this sense, it looks necessary to expose their presence in relation to those grey areas, that could become a context for spreading ambiguous points of view within cultural production.

Marinetti, Pound, Heidegger, have a general relevance that cannot be denied. Home and Cramer underlined that, at the moment, nothing of what we see internationally in the extreme-right panorama can be considered culturally relevant. The alt-right is not re-enacting counterculture. This “alternative” of the extreme right consist mostly of a cluster of media outlets producing hate and propaganda, within a revisionist narrative. It picks up an old rhetoric about heroic rebellion, arrogance, overbearing masculinity, mythization of war and the use of violence, in most cases using new definitions for old concepts. Home and Cramer concluded that there is no intrinsic value in being transgressive, and transgression alone cannot be enough to gain any kind of attribute of quality. Because transgression is just a tool. Artists and activists cannot stop experimenting and using the tool of transgression to criticise society, building alternatives and being alternative. The moderate approach in an era of political correctness is a way to enchain the Left; moreover people have the right to hate their condition, hate their job and the inequalities that affect their lives. This feeling is legitimately generated by a critical thinking.

The panel of the second day of the conference reflected on the practice of political, journalistic and activist infiltration as a way of better understanding extremist groups. The moderator explained how from one side infiltration maps extremist groups from the inside, and from the other, it analyses how extremist groups are building their networks, becoming widespread in online and offline. The aim is to explore such groups from within, analysing the reason for people to join them, as well as understanding their inner dynamics.

Rebecca Pates, Political Anthropologist from the University of Leipzig, moderated the discussion and introduced the four guests, commenting that a number of different things can be done when infiltrating. The activities and the achievements can differ, and so the technique, from total concealment in infiltration to openness about it. Pates suggested that from the inside it is possible to understand for example the reason why young people are attracted by groups that from the outside look so angry and violent, and it could be defined the sense of comradeship and belonging that convinces individuals to participate into these movements.

Julia Ebner is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) and author of the bestselling book The Rage: The Vicious Circle of Islamist and Far-Right Extremism. She opened the panel explaining how, after the terroristic attacks from right extremists in Europe and in the US, she decided to get a better understanding of the world of the far-right and their narrative. She infiltrated both online and offline, undercover, with fake identities and avatar accounts, changing her appearance. Her goal was to get into groups that are very different ideologically one from the other, like the neo-Nazi, the old conservative fascist movements and the counter Jihad movement. During her speech she described how she built up a new identity and made connections necessary to her purpose.

To get in touch with active members she used some social media and crowdsourcing platforms available for the extreme-right, such as “Gab”, the alt-right equivalent of twitter, “Wasp love”, a place to date “reformed Christians, confederate, home-schooled, white nationalists, alt-right and sovereign singles.” She was asked to send a full account of her genetic ancestry to be accepted or to share a picture of her skin colour. She had voice chat interviews to enquire about her ideological background or sexual orientation. Ebner entered an alternative universe of disinformation ecosystems and accessed subcultures that interact in parallel as a part of a same bigger network. When she was asked to justify fresh profiles, that she just created, she could benefit from the fact that many far-right users are removed and banned for what they post. She started frequenting all the different tech platforms considered a safe environment for far-right extremism, where they could very openly cultivate antisemitic and conspiracy theories, anti-left rhetoric, coordinate doxing and harassment activities. In 2016 the writer and researcher joined undercover the English Defence League and went to a rally of theirs against what they would call Muslim grooming gangs. A year later she was then recruited into the movement Generation Identity or Identitäre Bewegung, always as part of the new European alt-right (alternative right) and was invited to join them in public and private meetings, like a secret meeting in an Airbnb location in Brixton. In that occasion she was sitting among 20 white nationalists discussing their strategies to launch a British branch of their group, with a manifest focus on optics and media strategy briefings, to learn how to deal with tough questions from journalists about anti-Semitism and racism. They discussed about their political background and their selection procedures in order to achieve a good branding and quality in their membership. The obsession of appearing as decent citizens in public was and is very important in rallies like Charleville. Reports attest indeed that far right groups were concerned about how to dress and even told some people, not particularly good looking, that they could not join the event as they would not make a good impression. Events like Chemnitz, Charlottesville’s “rally to unite the right” or the experience of Defend Europe – an illegal far right ship that sought to hamper the rescue of refugees in the Mediterranean in 2016 – represent a cross-border collaboration between movements that until few years ago were not communicating. These events bring them together on the basis of their lowest common denominator for the sake of having a bigger impact.

After Ebner wrote an article for the Guardian and for the Independent she got backlash from the far-right and the English Defence League. Its founder, Tommy Robinson, ended up storming into her office with a cameraman, filming the whole confrontation and live streaming it to Rebel Media, a far-right news outlet in Canada. The influencer has 300.000 followers and these channels are very popular too. They gave immediate resonance to the aggression and set off a long chain reaction among other far-right and alt-right news platforms, globally. Her whole life got under attention, they used all available data to publicly discredit her. The researcher realised how much it is possible to do with online data to intimidate political opponents or people who criticize. Ebner and her colleagues experienced the hate campaign machine. She noticed that women are more attacked and threats, symptom of the wide anti-feminist and mesogenic culture. It seemed to her that the whole universe was against her activity of infiltration and that she had no supporters. Many different groups and networks were creating a distorted representation of her engagement, and this pushed her to embark on a research project about the interconnectedness of the variegated far-right media galaxy.

With other colleagues Ebner analysed about 5.000 pieces of content, accomplishing a lot of linguistic analysis, and studying interactions with social media monitoring tools. Thanks to this work the researcher can describe the mainstreaming strategies of the extreme right and how its members try to create compelling and persuasive countercultural campaigns using humour, satire and transgression and co-opting Pop Culture. An attitude common with the fundamental Islamism is they are creating content that has appeal on young people on the Internet but they are also concentrated on the traditional media, to make sure that they pick up on their provocations or fake news. They trigger media to report on them by staging online complaints that would go viral. Ebner has also started a project in collaboration with the organisation #ichbinhier e.V., discovering that this technique of coordinated interactions often creates the illusion that they represent the majority of the users. The research shows something different: 50% of the interactions or of the hateful comments below news articles, that they analysed, came from just 5% of all active accounts. A small but very loud minority of people that is now dominating the whole discourse amplified by bots or a media outlet sometimes also Russian ones, staging online psychological operations, jokes and meme to hide extreme right hatred campaigns behind humour-images.

Memetic warfare and gamification are two very relevant aspects, as frequent as quotations from the movies Matrix and Fight Club, with the rhetoric of the red pilling to see the truth. Most of the accounts active in this activity were coordinating posts and hashtags so that their content could get prioritised in the feeds and create viral campaigns, striving to dominate the whole social media discourse. They have very clear hierarchies, which could be ascribed to the gaming dimension too. Hateful comments and negative interactions appear in a flow, getting soon in the top section due to a high degree of coordination. Generation Identity is known for sharing content according to the tactics of the so-called media guerrilla warfare manual, based on a very militarised language, that describes actions, goals and sniper-missions to target and intimidate political opponents exploiting media. All comes in a very gamified way, as they talk about a virtual battlefield and electronic items, where a good performance allows to grow of level. During the German elections in 2017 members and followers of Reconquista Germanica (an extreme-right channel running on the Discord platform) were quite successful in spreading extreme-right topics and making politicians and media pick up on them. Some of their hashtags were often listed in the top 5 trends in the two weeks before the vote. In the meantime, they were evaluating and analysing their activity, celebrating successful “generals” or “soldiers” that were promoted into higher levels. Ebner expressed her concerns as this reflects in in real-world practice what they would do if they manage to establish their own vision and get in power. Since Trump was elected we’ve seen a growing ecosystem that repeats itself, where extreme-right is certainly reappearing. It is indeed possible to spot similar tactics and vocabulary among several European far-right groups, in the campaigns of Italian, German, French, Swedish and Dutch elections. She underlined how important it is to understand far-right extremism better and the relationship between Islamist and far-right extremism, as they have a lot in common and are reinforcing each other.

Anti-racist activist and “Hope Not Hate” researcher Patrik Hermansson reflected on the meaning of radical right-wing practices today bringing his direct story as undercover activist inside the international Alt-Right, and published in The International Alternative Right Report. Starting in the fall of 2016 he joined a London based organisation and then travelled through many other related groups, living a dual life. He described his year of infiltration inside an international secret formation called London Forum, for which you need to be vetted, background checked and have someone who lets you in. Hermansson works as a researcher for Hope Not Hate, an organisation established to offer a more positive and engaged way of doing anti-Fascism. This 26-year-old man has been “Erik”, a fascist who came to London inspired by Brexit and to get away from the liberal prejudice of Swedish universities. He entered and investigated the Forum, discovered members, techniques and goals, until he witnessed the terrible violence in Charlottesville, Virginia. To do so, Hermansson had to become a Swedish teacher of a member and was quickly driven into the world of the extreme right. From former Tory Party members to famous alt-right influencers, he met people in different countries and different social context. It was a safe space of anonymity, that you do not find on Social media.

Hermansson described to the audience of the Conference the social aspects animating the group, where members can feel part of a community, make new friends even overcoming political differences until they have anything else outside. Conspiracy theories have a relevant role too. Holocaust denial, addressed as “the biggest PR event in history”, or the chemistry rails, are important part of their theorization. They feel part of a group that is bound together by secrets that allow you to see behind the curtain and make you understand more than the rest of the population. Hermansson pointed out that the activity of infiltrate is a difficult and immoral business. It exploits people’s trust. It is justified by the need to expose techniques of recruitment, data, but we should not romanticize, not to go too far not to be ruthless. Hermansson infiltrated for a purpose, to get a closer image of right extremism and decided to expose the top players of the organisation, musicians and influencers. The most effective part of the activity, he said, was the sabotage. Infiltration makes people point fingers, paranoia spread in the movement and things broke apart. Hermansson explained that it was a conscious decision: the anti-fascist part of the research. The London Forum is not active anymore, people left it showing that the method of exposure is quite effective. He found out that his activity raised the cost of their recruiting process, which is now much tighter.

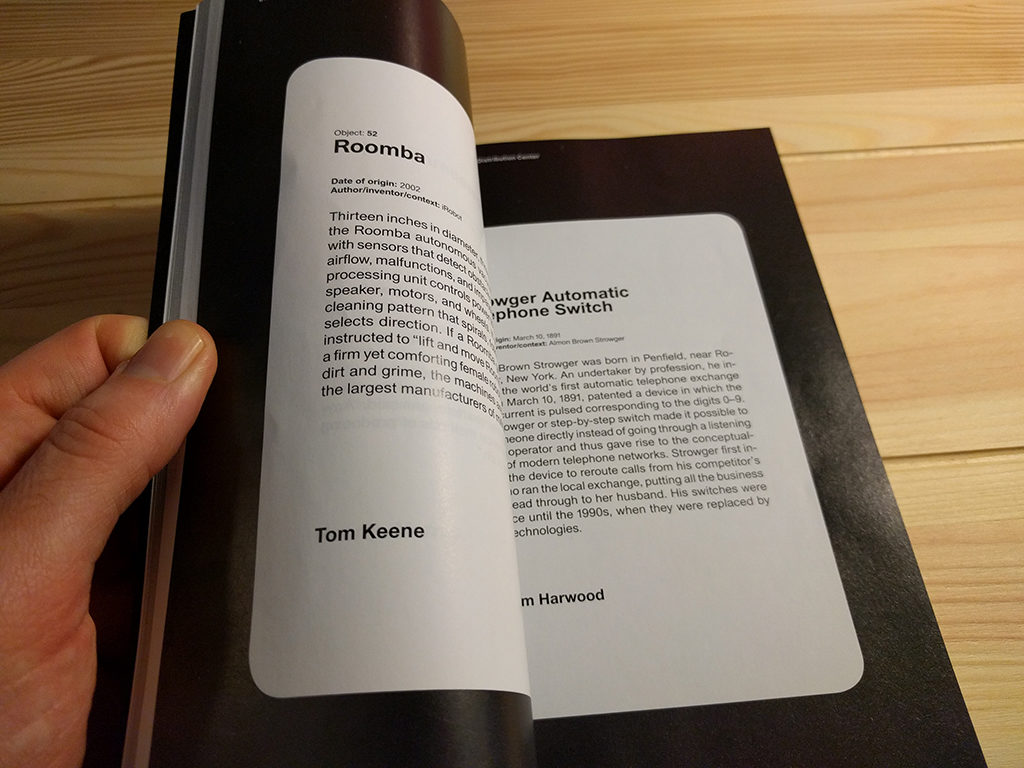

The panel was concluded by a member of the Unicorn Riot collective, “a decentralized non-profit media organization of artists and journalists, dictated to exposing root causes of dynamic social and environmental issues through amplifying stories and exploring sustainable alternatives in the globalized world.” The investigative journalist Christopher Schiano presented his work of analysing and publishing of leaked messages from white supremacist, neo-Nazi and various alt-right fascist groups in the US – followed by an introduction of the DiscordLeaks platform by the developer Heartsucker, who is working as an affiliated volunteer for the Unicorn Riot. The guests talked about how Unicorn Riot has obtained hundreds of thousands of messages from white supremacist and neo-Nazi Discord chat servers after the events in Charlottesville, and decided to organise and open a far-right activity centre to allow public scrutiny through data journalism.

Discord is a voice-over-Internet Protocol (VoIP) application for video gaming communities, offering text, image, video and audio communication between users in a chat channel. The US non-profit media organisation with its Discord Leaks has exposed hundreds of thousands of chats from alt-right and far-right servers received. Parker was receiving screenshots of real-time communications between alt-right activists involved in planning the Charlottesville rally and got a “general orders” document, along with audio recordings of a planning meeting ahead of the rally. The screenshots kept then coming throughout the following days.

As reported by the Washington Post, Discord allowed the organizers and participants of the rally to convene in private, invite-only threads shrouded in anonymity – with usernames such as “kristall.night” and “WhiteTrash.” On a Discord server called “Charlottesville 2.0,” they planned everything from car pools, dress code and lodging in Charlottesville to how one might improvise weapons in case of a fight. Some suggested using flag poles as a makeshift spear or club. Many of these things took place. The collective received also internal logs, which enabled them to better see the scope of plans for the Unite the Right rally. Since its founding, Unicorn Riot has gained relevance among people looking for alternative news sources, principally covering protests with an on-the-ground perspective that many mainstream outlets miss. Unicorn Riot was for example among the first media outlets to get to the rally in Charlottesville and cover it. Through their investigation they explained how the far right tries to recruit new member via Discord, or they unveiled the attempts of extremists to look like ordinary Trump’ supporters, building a victim narrative to insinuate the idea that they are targeted citizens. Some of them are supporting the police and members of the police force have been exposed for leaking information to far-right members. They exposed the movement Anticom, anti-communist action, active mostly in shitposting, and the group Patriot Front, whose members unite under the motto “we are Americans and we are Fascists.”

At the end of the three the panellists reasoned on the importance of infiltration, as a means to study the extreme right and expose their networks and members, their strategies and tactics. It can also be helpful to try to predict what these groups are about to do, foreseeing their next step. It means getting in touch with them, entering their circles based on comradeship and exchange of personal experiences. Ebner commented that the use of lies and distortion is the cost of it, wondering, however, about what the cost of inaction is instead. Hermansson reported about the effects of infiltration in terms of the desensitisation he went through, taking part in conversations without reacting. The same desensitisation process can be described in the memetic warfare.

As part of the Disruption Network Lab thematic series “Misinformation Ecosystems” (2018), this 3-days-conference concluded the 2018 programme of the Disruption Network Lab. The series began with a focus on hate-news, manipulators, trolls and influencers, that investigated online opinion manipulation and strategic hate speech in the frame of a growing international misinformation ecosystem, and their impact on civil rights. HATE NEWS focused on the issue of opinion manipulation, from the interconnections of traditional and online media to behavioural profiling within the Cambridge Analytica debate. This second conference took the process further by pointing to specific researches and investigations that illustrated how a process has clearly set in motion, whereas radical right is currently working on an international level, building cross-national connections and establishing global cooperation.

Not just Steve Bannon and a galaxy of media outlet and online platforms are pushing for a new authoritarian turnaround, based on discrimination and ultra-nationalism, having factual impact on political systems. On a grassroot level, there are local networks and formations able to unite different realities and backgrounds, melt together under new trendy labels, slogans and influencers. A new scene that is carefully designed to be appealing to moderate-leaning electorate, where you can find hooligans, hipsters, neo-Nazi and politicians dressed in suits and ties, all striving to appear like conscious citizens and decent members of society, part of a new generation of activists. However, beyond the facade, the majority of far-right groups shows to be against an open, multicultural society as well as against inter-religious and inter-cultural togetherness. They play with economic uncertainties, fear, anger and resentment to spread hate, attack opponents and discriminate minorities, often through a meme-driven alt-right humour, designed to cover with dark hilarity their racist propaganda and fascist drives. Jokes are used by public figures and influencers to promote misogyny, homophobia, a distorted idea of masculinity, racism and justify unacceptable statements. Too often mainstream media and newspapers pick up staged news from such misinformation ecosystems, enforcing a revisionist narrative built on manipulated facts and interactions, arrogance and violence.

Conspiratorial and paranoid thinking acts like a catalyst, provoking participation and fascinating individuals, who want to become warriors and custodians of knowledge. Alongside the image of the angry white man, there is a whole narrative of love and solidarity for their chosen group, the community they decide to protect, identified on utilitarian basis.

Despite of what is represented in media, many speakers at the conference pointed out that there is neither something alternative nor innovative in what they are offering. However, mainstream parties and media tend to follow their reactionary narrative, enforcing the idea that it is competitive. The guests of the Disruption Network Lab came from Africa, Europe, North and South America and exposed an intertwined scenario of transnationalism of the radical right. The direct engagement of activists, that decide to infiltrate, together with the work of researchers, journalists and artists, allowed for a clearer image of what is going on at a global as well as local scale, to understand how it is possible to interrupt this process working actively within the civil society. Sabotage and exposure are instruments useful to disrupt and unveil strategies aimed at sending the world back of a hundred years of human rights achievements. Thanks to Tatiana Bazzichelli and the Disruption Network Lab team, who offered a stage to learn about constructive practices that can be activated in order to change the course of things.

–

INFILTRATION: Challenging Supremacism

SEE VIDEO DOCUMENTATION OF THE CONFERENCE

SEE PHOTOS FROM THE CONFERENCE

On the day of the General Data Protection Law (GDPR) going into effect in Europe, on the 25th of May, the Disruption Network Lab opened its 13th conference in Berlin entitled “HATE NEWS: Manipulators, Trolls & Influencers”. The two-day event looked into the consequences of online opinion manipulation and strategic hate speech. It investigated the technological responses to these phenomena in the context of the battle for civil rights.

The conference began with Jo Havemann presenting #DefyHateNow, a campaign by r0g_agency for open culture and critical transformation, a community peace-building initiative aimed at combating online hate speech and mitigating incitement to offline violence in South Sudan. More than ten years ago, the bulk of African countries’ online ecosystems consisted of just a few millions of users, whilst today’s landscape is far different. This project started as a response to how social media was used to feed the conflicts that exploded in the country in 2013 and 2016. It calls to mobilize individuals and communities for civic action against hate speech and social media incitement to violence in South Sudan. Its latest initiative is the music video #Thinkbe4uclick, a new awareness campaign specifically targeted at young people.

In Africa, hate campaigns and manipulation techniques have been causing serious consequences for much longer than a decade. The work of #DefyHateNow counters a global challenge with local solutions, suggesting that what is perceived in Europe and the US as a new problem should instead be considered in its global dimension. This same point of view was suggested by the keynote speaker of the day, Nanjala Nyabola, writer and political analyst based in Nairobi. Focusing on social media and politics in the digital age, the writer described Kenya´s recent history as widely instructive, warning that manipulation and rumours can not only twist or influence election results but drive conflicts feeding violence too.

The reliance on rumours and fake news was the principal reason that caused the horrifying escalation of violence following the Kenyan 2007 general election. More than 1,000 people were killed and 650,000 displaced in a crisis triggered by accusations of election fraud. The violence that followed unfolded fast, with police use of brutal force against non-violent protesters causing most of the fatalities. The outbreak of violence was largely blamed on ethnic clashes inflamed by hate speech. It consisted of revenge attacks for massacres supposedly carried out against ethnic groups in remote areas of the country. Unverified rumours about facts that had not taken place. Misinformation and hate were broadcast over local vernacular radio stations and with SMS campaigns, inciting the use of violence, animating different groups against one another.

The general election in 2013 was relatively peaceful. However, ethnic tensions continued to grow across the whole country and ethnic driven political intolerance appeared increasingly on social media, used mainly by young Kenyans. Online manipulation and disinformation proliferated on social media again before and after the 2017 general election campaign.

Nyabola explained that nowadays the media industry in Kenya is more lucrative than in most other African regions, which could be considered a positive aspect, suggesting that within Kenya the press is free. Instead a majority media companies depend heavily on government advertising revenue, which in turn is used as leverage by authorities to censor antagonistic coverage. It should be no wonder Kenyans appear to be more reliant on rumours now than in 2007. People are increasingly distrustful of traditional media. The high risk of manipulation by media campaigns and a duopoly de facto on the distribution of news, has led to the use of social media as the principle reliable source of information. It is still too early to have a clear image of the 2017 election in terms of interferences affecting its results, but Nyabola directly experienced how misinformation and manipulation present in social media was a contributing factor feeding ethnic angst.

Rafiki, the innovative Kenyan film presented at the Cannes Film Festival, is now the subject of controversy over censorship due to its lesbian storyline. Nyabola is one of the African voices expressing the intention to support the movie’s distribution. “As something new and unexpected, this movie might make certain people within the country feel uncomfortable,” she said, “but it cannot be considered a vehicle for hate, promoting homosexuality in violation of moral values.” It is essential not to confuse actual hate speech with something labelled as hate speech to discredit it. Hate speech is intended to offend, insult, intimidate, or threaten an individual or group based on an attribute, such as sexual orientation, religion, colour, gender, or disability. The writer from Nairobi reminded the audience that when we talk about hate speech, it is important to focus on how it makes people feel and what it wants to accomplish. We should always consider that we regulate hate speech since it creates a condition in which social, political and economic violence is fed, affecting how we think about groups and individuals (and not just because it is offensive).

Nyabola indicated few key factors that she considers able to increase the consequences of hate speech and manipulation on social media. Firstly, information travels fast and can remain insulated. Whilst Twitter is a highly public space where content and comments flow freely, Facebook is a platform where you connect just with a smaller group of people, mostly friends, and WhatsApp is based on groups limited to a small number of contacts. The smaller the interaction sphere is, the harder it is for fact-checkers to see when and where rumours and hate speech go viral. It is difficult to find and stop them and their impact can be calculated just once they have already spread quickly and widely. Challenges which distinguish offline hate speech and manipulation from online ones are also related to the way information moves today among people supporting each other without a counterpart and without anyone being held to account.

Nowadays Kenya boasts an increasingly technological population, though not all rural areas have as yet been able to benefit from the country being one of the most connected ones in sub-Saharan Africa. In this context, reports indicate that since 2013 the British consulting firm Cambridge Analytica had been working in the country to interfere with elections, organizing conventions, orchestrating campaigns to sway the electorate away from specific candidates. It shall be no surprise that the reach of Cambridge Analytica extended well beyond United Kingdom and USA. In her speech, Nyabola expressed her frustration as she sees that western media focus their attention on developing countries just when they fear a threat of violence coming from there, ignoring that the rest of the world is also a place for innovation and decision making too.

Kenya has one of the highest rates of Internet penetration in Africa with millions of active Kenyan Facebook and Twitter accounts. People using social media are a growing minority and they are learning how to defeat misinformation and manipulation. For them social media can become an instrument for social change. In the period of last year’s election none of the main networks covered news related to female candidates until the campaigns circulating on social media could no longer be ignored. These platforms are now a formidable tool in Kenya used to mobilize civil society to accomplish social, gender and economic equality. This positive look is hindered along the way by the reality of control and manipulation.

Most of the countries globally currently have no effective legal regulation to safeguard their citizens online. The GDPR legislation now in force in the EU obliges publishers and companies to comply with stricter rules within a geographic area when it comes to privacy and data harvesting. In Africa, national institutions are instead weaker, and self-regulation is often left in the hands of private companies. Therefore, citizens are even more vulnerable to manipulation and strategic hate speech. In Kenya, which still doesn’t have an effective data protection law, users have been subject to targeted manipulation. “The effects of such a polluted ecosystem of misinformation has affected and changed personal relationships and lives for good,” said the writer.

On social media, without regulations and control, hatred and discriminations can produce devastating consequences. Kenya is just one of the many countries experiencing this. Hate speech blasted on Facebook at the start of the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar. Nyabola criticized that, as in many other cases, the problem was there for all, but the company was not able to combat the spread of ethnic based discrimination and hate speech.

Moving from the interconnections of traditional and online media in Kenyan misinformation ecosystem, the second part of the day focused on privacy implications of behavioural profiling on social media, covering the controversy about Cambridge Analytica. The Friday’s panel opened with the analyses of David Carroll, best known as the professor who filed a lawsuit against Cambridge Analytica in the UK to gain a better understanding of what data the company had collected about him and to what purpose. When he got access to his voter file from the 2016 U.S. election, he realized the company had been secretly profiling him. Carroll was the first person to receive and publish his file, finding out that Cambridge Analytica held personal data on the vast majority of registered voters in the US. He then requested the precise details on how these were obtained, processed and used. After the British consulting firm refused to disclose, he decided to pursue a court case instead.

As Carroll is a U.S. citizen, Cambridge Analytica took for granted that he had neither recourse under federal U.S. legislation, nor under UK data protection legislation. They were wrong. The legal challenge in British court case that centred on Cambridge Analytica’s compliance with the UK Data Protection Act of 1998 could be applied because Carroll’s data was processed in the United Kingdom. The company filed for bankruptcy not long after it was revealed that it used the data of 87 million Facebook users to profile and manipulate them, likely in contravention of UK law. Professor Carroll could never imagine that his activity would demolish the company.

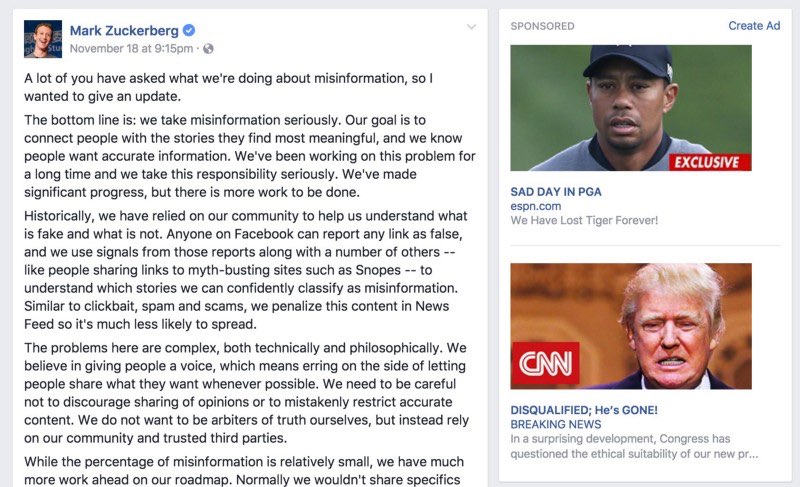

Cambridge Analytica, working with an election management firm called SCL Group, appears to have been a propaganda machine master, able to manipulate voters through the combination of psychometric data. It exploited Facebook likes and interactions above all. Its technique disguised attempts at political manipulation since they were integrated in the online environment.

Carroll talked about how technology and data were used to influence elections and popular voting for the first time in countries like USA and UK, whereas for a much longer time international campaign promoters were hired to act on an international scale. In Carroll’s opinion Cambridge Analytica was an ‘oil spill’ moment. It was an epiphany, a sudden deep understanding of what was happening on a broader scale. It made people aware of the threat to their privacy and the fact that many other companies harvest data.

Since 2012 Facebook and Google have been assigning a DoubleClick ID to users, attaching it to their accounts, de-anonymizing and tracking every action. It is an Ad-tracker that gives companies and advertisers the power to measure impressions and interactions with their campaigns. It also allows third-party platforms to set retargeting ads after users visit external websites, integrated with cookies, accomplishing targeted profiling at different levels. This is how the AdTech industry system works. Carroll gave a wide description of how insidious such a technique can be. When a user downloads an app to his smartphone to help with sport and staying healthy, it will not be a secret that what was downloaded is the product of a health insurance or a bank, to collect data of potential customers, to profile and acquire knowledge about individuals and groups. Ordinary users have no idea about what is hidden under the surface of their apps. Thousands of companies are synchronizing and exchanging their data, collected in a plethora of ways, and used to shape the messages that they see, building up a tailor-made propaganda that would not be recognizable, for example, as a political aid. This mechanism works in several ways and for different purposes: to sell a product, to sell a brand or to sell a politician.

In this context, Professor Carroll welcomed the New European GDPR legislation to improve the veracity of the information on the internet to create a safer environment. In his dissertation, Carroll explained that the way AdTech industry relates to our data now contaminates the quality of our lives, as singles and communities, affecting our private sphere and our choices. GDPR hopefully giving consumers more ownership over their data, constitutes a relevant risk for companies that don’t take steps to comply. In his analyses the U.S. professor pointed out how companies want users to believe that they are seriously committed to protecting privacy and that they can solve all conflicts between advertising and data protection. Carroll claimed though that they are merely consolidating their power to an unprecedented rate. Users have never been as exposed as they are today.

Media companies emphasize the idea that they are able to collect people’s data for good purposes and that – so far – it cannot be proved this activity is harmful. The truth is that these companies cannot even monitor effectively the Ads appearing on their platforms. A well-known case is the one of YouTube, accused of showing advertisements from multinational companies like Mercedes on channels promoting Nazis and jihad propaganda, who were monetizing from these ads.

Carroll then focused on the industry of online advertisement and what he called “the fraud of the AdTech industry.” Economic data and results from this sector are unreliable and manipulated, as there are thousands of computers loading ads and making real money communicating to each other. This generates nowadays a market able to cheat the whole economy about 11 billion dollar a year. It consists of bots and easy clicks tailor-made for a user. The industries enabled this to happen and digital advertising ecosystem has evolved leading to an unsafe and colluded environment.

Alphabet and Facebook dominate the advertising business and are responsible for the use of most trackers. Publishers as well as AdTech platforms have the ability to link person-based identifiers by way of login and profile info.

Social scientists demonstrated that a few Facebook likes can be enough to reveal and accurately predict individual choices and ideas. Basic digital records are so used to automatically estimate a wide range of personal attributes and traits that are supposed to be part of a private sphere, like sexual orientation, religious beliefs, or political belonging. This new potential made politicians excited and they asked external companies to harvest data in order to generate a predictive model to exploit. Cambridge Analytica’s audience-targeting methodology was for several years “export-controlled by the British government”. It was classified as weapon by the House of Commons, at a weapons-grade communications tactics. It is comprehensible then that companies using this tech can easily sell their ability to influence voters and change the course of elections, polarizing the people using social networks.

The goal of such a manipulation and profiling is not to persuade everybody, but to increase the likelihood that specific individuals will react positively and engage with certain content, becoming part of the mechanism and feeding it. It is something that is supposed to work not for all but just for some of the members of a community. To find that small vulnerable slice of the U.S. population, for example, Cambridge Analytica had to profile a huge part of the electorate. By doing this it apparently succeeded in determining the final results, guiding and determining human behaviours and choices.

Bernd Fix, hacker veteran of the Chaos Computer Club in Germany, entered the panel conversation describing the development from the original principle of contemporary cybernetics, in order to contextualize the uncontrollable deviated system of Cambridge Analytica. He represented the cybernetic model as a control theory, by which a monitor compares what is happening into a system with a standard value representing what should be happening. When necessary, a controller adjusts the system’s behaviour accordingly to again reach that standard expected by the monitor. In his dissertation, Fix explained how this model, widely applied in interdisciplinary studies and fields, failed as things got more complex and it could not handle a huge amount of data in the form of cybernetics. Its evolution is called Machine Learning (or Artificial Intelligence), which is based on the training of a model (algorithm) to massive data sets to make predictions. Traditional IT has made way for the intelligence-based business model, which is now dominating the scene.

Machine learning can prognosticate with high accuracy what it is asked to, but – as the hacker explained – it is not possible to determine how the algorithm achieved the result. Nowadays most of our online environment works through algorithms that are programmed to fulfil their master’s interests, whereas big companies collect and analyse data to maximize their profit. All the services they provide, apparently for free, cost users their privacy. Thanks to the predictive model, they can create needs which convinces users to do something by subtle manipulating their perspective. Most of the responsibilities are on AdTech and social media companies, as they support a business model that is eroding privacy, rights and information. The challenge is now to make people understand that these companies do not act in their interest and that they are just stealing data from them to build up a psychometric profile to exploit.

The hacker reported eventually the scaring case of China’s platform “social credit,” designed to cover every aspect of online and offline existence and wanted by the national authorities. It is supposed to monitor each person and catalogue eventual “infractions and misbehaviours” using an algorithm to integrate them into a single score that rates the subjective fidelity into accepted social standards. A complex kind of ultimate social control, still in its prototype stages, but that could become part of our global future where socio-political regulation and control are governed by cybernetic regulatory circuits. Fix is not convinced that regulation can be the solution: to him, binding private actors and authorities to specific restriction as a way to hold them accountable is useless if people are not aware of what is going on. Most people around us are plugged into this dimension where the bargain of data seems to be irrelevant and the Big Three – Google, Facebook and Amazon – are allowed to self-determine the level of privacy. People are too often happy consumers who want companies to know their lives.

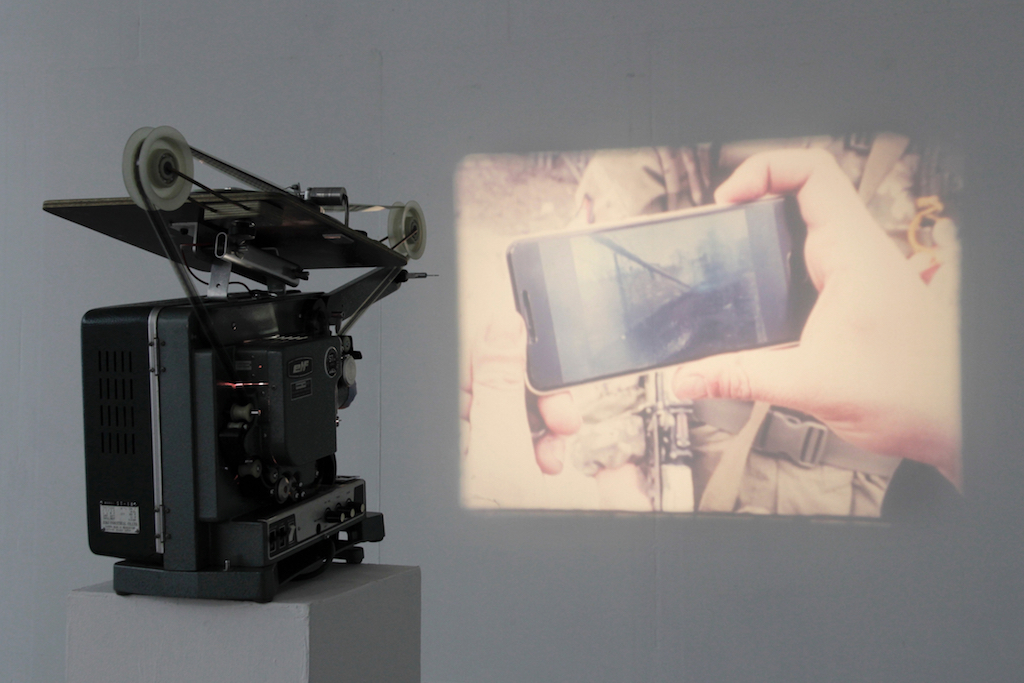

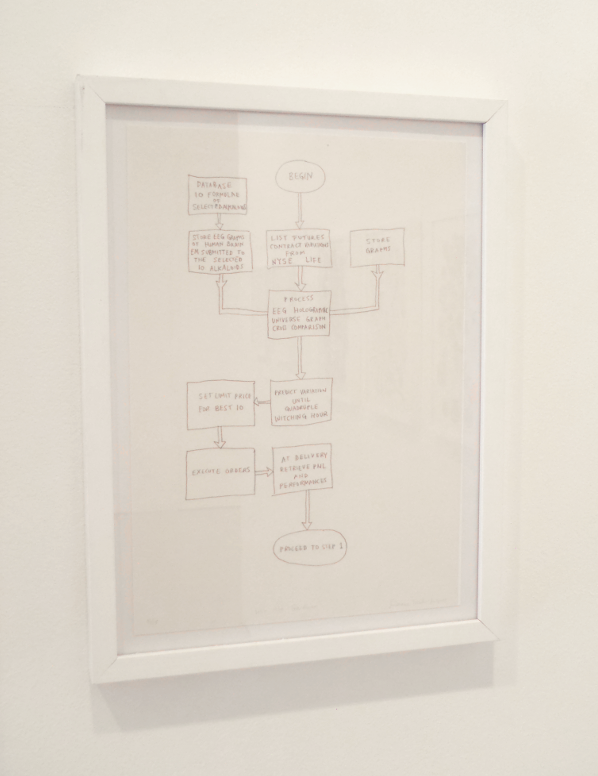

The last panellist of the afternoon was the artist and researcher Marloes de Valk, who co-developed a video game for old 1986 Nintendo consoles, which challenges the player to unveil, recognize and deconstruct techniques used to manipulate public opinion. The player faces the Propaganda Machine, level after level, to save the planet.

“Acid rains are natural phenomena”, “passive smoke doesn’t affect the health,” “greenhouse´s effects are irrelevant.” Such affirmations are a scientific aberration nowadays, but in the ‘80s there were private groups and corporations struggling to make them look like legitimate theorizations. The artist from Nederland analysed yesterday´s and today’s media landscape and, basing her research on precise misinformation campaigns, she succeeded in defying how propaganda has become more direct, maintaining all its old characteristics. De Valk looked, for example, for old documents from the American Tobacco Institute, for U.S. corporations‘leaked documents and also official articles from the press of the ´80s.

What remains is a dark-humoured game whose purpose is that of helping people to orientate inside the world of misinformation and deviated interests that affects our lives today. Where profit and lobbyism can be hidden behind a pseudoscientific point of view or be the reason rumours are spread around. The artist and researcher explained that what you find in the game represents the effects of late capitalism, where self-regulation together with complacent governments, that do not protect their citizens, shape a world where there is not room for transparency and accountability.

In the game, players get in contact with basic strategies of propaganda like “aggressively disseminate the facts you manufactured” or “seek allies: create connections, also secret ones”. The device used to play, from the same period of the misinformation campaigns, is an instrument that reminds with a bit of nostalgia where we started, but also where we are going. Things did not change from the ‘80s and corporations still try to sell us their ready-made opinion, to make more money and concentrate more power.

New international corporations like Facebook have refined their methods of propaganda and are able to create induced needs thus altering the representation of reality. We need to learn how to interact with such a polluted dimension. De Valk asked the audience to consider official statements like “we want to foster and facilitate free and open democratic debate and promote positive change in the world” (Twitter) and “we create technology that gives people the power to build community and bring the world closer together” (Facebook). There is a whole narrative built to emphasize their social relevance. By contextualising them within recent international events, it is possible to broad the understanding of what these companies want and how they manipulate people to obtain it.

What is the relation between deliberate spread of hate online and political manipulation?

As part of the Disruption Network Lab thematic series “Misinformation Ecosystems” the second day of the Conference investigated the ideology and reasons behind hate speech, focusing on stories of people who have been trapped and affected by hate campaigns, violence, and sexual assault both online and offline. The keynote event was introduced by Renata Avila, international lawyer from Guatemala and a digital rights advocate. Speaker was Andrea Noel, journalist from Mexico, “one of the most dangerous countries in the world for reporters and writers, with high rates of violence against women” as Avila remembered.

Noel has spent the last two years studying hate speech, fake news, bots, trolls and influencers. She decided to use her personal experience to focus on the correlation between misinformation and business, criminal organizations and politics. On March 8, 2016 it was International Women’s Day, and when Noel became a victim of a sexual assault. Whilst she was walking down the street in La Condesa (Mexico City) a man ran after her, suddenly lifted up her dress, and pulled her underwear down. It all lasted about 3 seconds.

As the journalist posted on twitter the surveillance footage of the assault commenting: “If anyone recognizes this idiot please identify him,” she spent the rest of the evening and the following morning facing trolls, who supported the attacker. In one day her name became trend topic on twitter on a national level, in a few days the assault was international news. She became so subject of haters and target of a misogynistic and sexist campaign too, which forced her to move abroad as the threat became concrete and her private address was disclosed. Trolls targeted her with the purpose of intimidating her, sending rape and death threats, pictures of decapitated heads, machetes and guns.

In Mexico women are murdered, abused and raped daily. They are victims of family members, husbands, authorities, criminals and strangers. Trolls are since ever active online promoting offensive hashtags, such as #MujerGolpeadaMujerFeliz, which translates as ‘a beaten woman is a happy woman’. It is a spectrum of the machismo culture affecting also many Latin American countries and the epidemic of gender-based violence and sexual assault.