Leila Johnston was Rambert Dance company’s first ‘digital creative in residence’ from October 2015 – February 2016, having successfully applied to their residency programme, Sprint. The programme aims to enable Rambert to engage more deeply with the digital world, and is framed as experimental and light touch, with no expectations or goals in mind. One of the outputs of Leila’s residency – and the subject of this review – was a report ‘Hacking Rambert’, an incisive account of Leila’s time on Sprint, as well as a reflection on the nature of the creative residencies, dance and technology cultures.

Leila describes herself as an outspoken critic of current technology culture, resistant to its tendency for ‘digital evangelism’. The report belies her frustrations with technology culture – and indeed is a call to arms for rethinking what that culture needs to become. Her approach to the residency reflects this, emphasizing that its value came from bringing her critical perspectives about tech culture to bear, as much as from introducing dancers to ‘tools’ (though this played an important role too). She stresses how opportunities for growth and learning arose ‘through people (and sometimes tech)’ (my italics), and places human interaction and collaboration at the forefront, alongside, if not over and above, hardware and software. Dance is, she says, ‘about extraordinary relationships on every level – with yourself and then the little halo of space around you at all times, and then with greater and greater halos until it’s with everyone you meet.’ People are at the centre of her thinking and writing, and her residency was underpinned by questions such as ‘Is there a way to use technology to do justice to the human lifetimes that go into dance? Is there a way to dignify individuals, to invite confrontations with real people, to respect something other than the movement and acknowledge the part that individual experience plays in the construction of dance?’

Reflections on the cultures of the dance and technology worlds are also central to the report. Leila was struck by the relative openness and accountability of the dance world, which she saw as ‘a home that opens its doors to anyone that knocks’, in contrast to self-aggrandizing, solution-focused, often misogynistic digital world that is so well equipped to sell itself and its benefits. One of the observations that fascinated me most was about the different approaches to labour in the dance and digital worlds. For the former, hard work is a celebrated and central driver – dancers are ‘efficient’ because no work is seen as wasted. By contrast, the digital world wants to recover ‘free time’ by getting the hard stuff out of the way. While tech wants to make things easier – dance wants to make them harder – so that difficulties and limitation can be mastered and overcome.

The dominant tech world rhetoric that technology – coding especially – is ‘for everyone’ is thrown into relief by its absence in the dance world, where no one would expect ‘everyone’ to be a brilliant dancer, since this is something that requires a lifetime of grit and dedication as well as the right body and innate talent. Leila shows us that we can learn from the dancers’ dedication and commitment that ‘not everyone can do anything, and that there are pursuits that arise from the nuanced world of individual lifetimes and personal, emotional, motivation, the results of which don’t resolve into a formula’.

Although her emphasis was on criticality and personal relations, she drew on an impressive range of kit. She experimented with a thermal camera attached to her iPhone, which enabled her to explore a ‘dance of heat’. She observed that ‘the idea that dancers can be expressed as their invisible heat is strange, but absolutely real’.

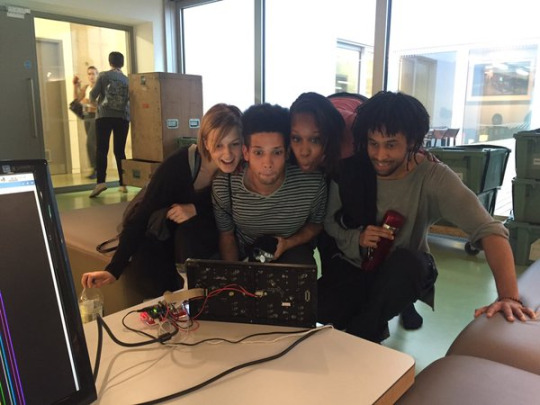

The Point Cloud demo on the Kinect was of great interest to the dancers, for whom it allowed a new kind of 360-degree vision, useful since they are ‘always looking for their own back’. Leila experimented with a Raspberry Pi, using it for a range of experiments including connecting LED panels where she could display words and video. Again though, as well as the tool itself, the Pi gave rise to critical reflection: ‘Why aren’t we teaching dancers and choreographers creative technology skills for their work, rather than reinforcing a hierarchy of expertise by ‘advising’ them on creative direction?’ Emphasizing how accessible and readily available Pis, LED panels and other technologies now are, Leila makes the point that maker culture can be embedded in the dance world at little cost, but this won’t happen organically unless more awareness of each other’s culture is fostered.

Drawing from the residency blog hackingrambert.tumblr.com, Leila reflects on time, truth, and difficulty. She is resolute that time, patience and commitment are needed to make meaningful artistic contributions, and that artists undertaking short term residencies need to be realistic about what can be achieved. Rather than gunning for a finished product, ‘short projects should be about making – what it means to be a creative, and what we learned about the best way to do things in the context of the artificially short creation time.’ Unlike the tech world, quick fix and solutionism will not fare well on a creative residency.

Leila’s reflections on the notion of truth are intriguing; she feels that there is ‘nowhere to hide’ in dance, and draws a parallel between dancers’ bodies and the ‘technical authenticity’ of circuit boards and wires. These forms of hardware offer respite from the slick interfaces that are so characteristic of digital technologies. She notes: ‘I’m interested in the relationship between truth and performance; the unique way in which (dance) performances are honest, how our bodies give away the truth, how things represent what they are very transparently’. These explorations of truth provoke rich questions about authenticity, identity, ‘fidelity’ and representation. The notion of the stripped back body is a striking one, and when one observes a dancer in motion, with their muscles, sinews, bones, sweat, and humanity on display, there can be a powerful connection between the dancer and the audience. However, there is artifice at work in dance too – creating illusions with the body, emphasizing certain lines, creating the appearance of fluidity and ease when the body is being pushed to its physical limits. Can we draw an analogy here to the performance of identity online, where the blood, sweat, tears and humanity are often glossed over with ‘choreographed’ images that appear spontaneous and perfect? Or is the truth of dance and bodies precisely an antidote to this phenomenon? My caution here would be that dancers have identities as well as bodies, and are not immune to the pressures placed on them about their appearance and representation.

Leila argues that the creative tech community needs to work harder to understand dance, but that dance too ‘has much to gain by creatively educating itself in the available tech options’. Introducing dancers and the dance world to creative technologies can be fruitful, but should not be understood in solutionist terms. Technologists must take responsibility for the enormous power they have in society – it is up to them to ‘educate and differentiate’ between the potentially homogenous mass that is ‘technology. Finally, she makes a case for ‘contemporary creative technology’. The notion of the contemporary connotes the historical nature of a given art form and the contingencies of its evolution – conceptually, technically, physically, socio-politically. The relative nascence of technology, she suggests, leaves it unanchored, and subject to the intentions of ‘commercial forces’. She states ‘A contemporary creative technology could lay down the microphone of narrative and exist in the depths of the present. We could stop writing our own story in the cultural canon – indeed stop telling stories about what we’re doing at all – and focus on being demonstrable and accountable.’

There are moments when Leila seems to idealize the dance world as relatively problem-free, without acknowledging its potential problems – not least the subjection of bodies to punishing regimes and the mental and physical problems this can give rise to, and issues of social inequality, accessibility and exclusivity that come with all creative industries. However, there is clearly a lot the technology world can learn from the culture of dance. Perhaps the tech sector should start having dancers in residence…

For more than two decades, Italian artist duo Eva and Franco Mattes have sought to subvert and expose the systems which produce power. Their current exhibition, Abuse Standards Violations at Carroll/Fletcher gallery, looks at who and what is made visible and invisible in the process of producing culture for online consumption.

The artists, who did not receive a formal arts education, describe themselves as “a couple of restless con-artists who use non-conventional communication tactics to obtain the largest visibility with the minimal effort.” They repeatedly worry the edges of technical structures – legal, religious, software – observe the resultant content and feed it back into new structures. It’s a process which acknowledges and seeks to communicate erasure, loss and chaos as well as their inverses. In Abuse Standards Violations, the artists acknowledge that chaos, and slippiness of boundaries in the arrangement of work that collides fragments of different disciplines and practices together.

The central work in the exhibition is Dark Content. When their project No Fun (2010), presented unchallenged in a gallery, was removed from YouTube on the grounds of being ‘shocking and disgusting content’, the Mattes’ began investigating content moderation. The video, image and text content we encounter on platforms like Youtube is there because it has been permitted to be there. To gain permission, content once produced must be approved. The approval process involves a number of decision-making structures. The rules determining which content passes or fails (is good or bad, safe or unsafe) are built by, and entangled with, the organisational framework of the platform. To deploy this framework and enforce its rules, algorithms organise data and trace patterns, and people – working as ‘content moderators’ – are paid to decide which criteria a piece of content belongs to, and act accordingly.

Eva and Franco spoke to a number of content moderators about their work. These interviews give insight into a role which is simultaneously powerful and socially stigmatised (one moderator does not tell their partner what they do); which, despite actively forming culture, is in many ways concealed. Following the neoliberal pattern, process is skipped over to reach the content; moderators are scarcely mentioned by the culture in whose production they are thoroughly implicated. This is unsurprising given that the moderators are people like you and me, as well as being points through whom the governing structures of social media can be accessed.

The Mattes’ interviews with content moderators are presented in the exhibition as stock avatars, preserving the anonymity of the speakers; away from the exhibition, the interviews can be seen only on the Darknet. The avatars in Dark Content are displayed on screens within booths constructed from office furniture; structures designed for typing and filing are flipped around like tetris blocks to become a new kind of structure. The furniture is simultaneously recognisable, and out-of-place – particularly, no doubt to the freelance, self-employed person who often works from the sofa or cafe.

BEFNOED (Be Everyone For No One Every Day), deploys unusual positioning of screens in the gallery space. Visitors are required to lie on their backs, crouch down or otherwise contort themselves in order to watch videos of other people carrying out banal tasks such as putting a bucket on their head. The latter group of people has been paid for their work, the tasks having been advertised on crowdsourcing websites. Both groups have spent energy and time on their endeavours, and now both come together in a space. The intimacy is an interface which suggests the connectedness of gallery visitor and global networks and their mutual implication in the way culture is produced.

The works in Abuse Standards Violations relate and separate different lives, different cultures and different kinds of labour. They muddle contexts and objects, creating spaces and structures that are – clearly and disconcertingly – no less strange than those already available in contemporary society. These spaces and structures complicate the difference between reality and simulation. They also make the distribution of power painfully clear. For a powerful structure to appear trustworthy it is useful to appear impartial, logical, scientific; to appear trustworthy it is useful to destabilise or dismantle other structures by choosing what is made visible and what is not, what to make public and what to keep private. Those who are unfamiliar with the regulatory structures become implicated unknowingly. One of the moderators interviewed for Dark Content did not consider their work censorship since they worked for the government. Another comment ran along the lines of ‘I am only enforcing the rules; I don’t make them’.

In making clearer the arrangements of power behind YouTube, the arrangements of power in the art world – one of the routes to cultural production – are necessarily also challenged. The aesthetic choices the artists have made have clear social and political implications which create uncomfortable questions about concepts such as privacy. The complicated act of content moderation makes some information unavailable in order to communicate other information. This process is by no means limited to the world of content moderation – it applies wherever there is a message to pass on.

Invisible labour and visible outputs are separated by social stigma, sophisticated regulatory systems and other factors, local and global, which create a powerful invisibility. The works in Abuse Standards Violations combine objects, images, texts and concepts in surprising ways which give some substance to this invisibility. The job of the content moderator is part of culture, as is the expenditure of energy by bodies, as are rotas, as are company regulations, as are artists and galleries and gallery visitors. Thinking about how such things relate leads to challenging and powerful questions.

Abuse Standards Violations is at Carroll/Fletcher gallery in Soho until 27 August alongside Planetary-scale Computation by Joshua Citarella.

http://www.carrollfletcher.com/exhibitions/55/overview/

Featured Image: Ubermorgen, “Vote-Auction”, 2000. Installation view from the exhibition “Whistleblower & Vigilantes”

It has been a long time since an exhibition shocked and confused me. In fact, I cannot even remember when it last happened. Yet the exhibition Whistleblowers & Vigilanters has managed to do just that. Curators Inke Arns and Jens Kabisch of the Dortmund art institution Hartware Medienkunst Verein (HMKV) have put up a show in which complete nut cases are presented side by side with political activists, artists and whistleblowers a la Edward Snowden. This makes the exhibition ask for quite some flexibility from the audience. Visitors have to work hard in order to understand the connection made here between, for example, racist conspiracy theories expressed through YouTube videos and the ordeal of a whistleblower like Chelsea Manning.

The very short introduction text to the exhibition guide is part of the puzzle we are presented with. The basic premises of the exhibition are explained in what I think is not the best possible manner, because it leaves out any mentioning or analysis of the huge political differences among the people and works presented. At the same time the use of words like higher law and self-legitimization easily creates a feeling of unease about each practitioner or type of activism in the show:

“The exhibition asks what links hacktivists, whistleblowers and (Internet) vigilantes. What is the legal understanding of these different actors? Do they share certain conceptions? Who speaks and acts for whom and in the capacity of which (higher) law? Among other issues the exhibition will examine the differing legal conceptions and strategies of self-legitimisation put forth by activists, whistleblowers, hackers, online activists and artists to justify their actions.”

By placing the revelations of Edward Snowden next to the complete print out of the manifesto of the Unabomber or (more harmless but still of a different level of impact) the battle over a hostile domain name takeover in Toywar the first impression is a levelling of the practices and people involved. To make some sort of distinction between the various represented rebellious or activist positions in the exhibition guide the whole is divided into sections. The sections however do not indicate socio-political position or relevance, but rather imply the ways people legitimize their actions (1).

The spatial design and mapping of the exhibition seem to give some indication of political direction, but it is accidental. To the far right of the entry we find all installations labeled ‘Vigilantes’: a website collecting images of online fraudsters (419eater.com), two videos about Anders Breivik and Dominic Gagnon’s collection of mostly right-wing extremist YouTube videos. Slightly controversial is how the Vigilantes section puts together these quite obvious nut cases and criminals with Anonymous and what the curators call ‘Lulz’, the near troll-like jokesters who ridicule anything they don’t like with razor sharp memes. I am not sure whether these two products of the online forum 4chan deserve this simple pairing to YouTube hate preachers. A finer distinction between the various Internet underbelly representatives might have been better here. That this could have been done is shown by Lutz Dammbeck’s archive on the Unabomber’s placement in the Vigilante section, which has two labels. It is the sole representative of the Critique of Technology section as well. Another strange pairing happens in the Antinomism section, where an installation around a video with Julian Assange and a rightwing terrorist bomb disguised as soda machine are the only examples.

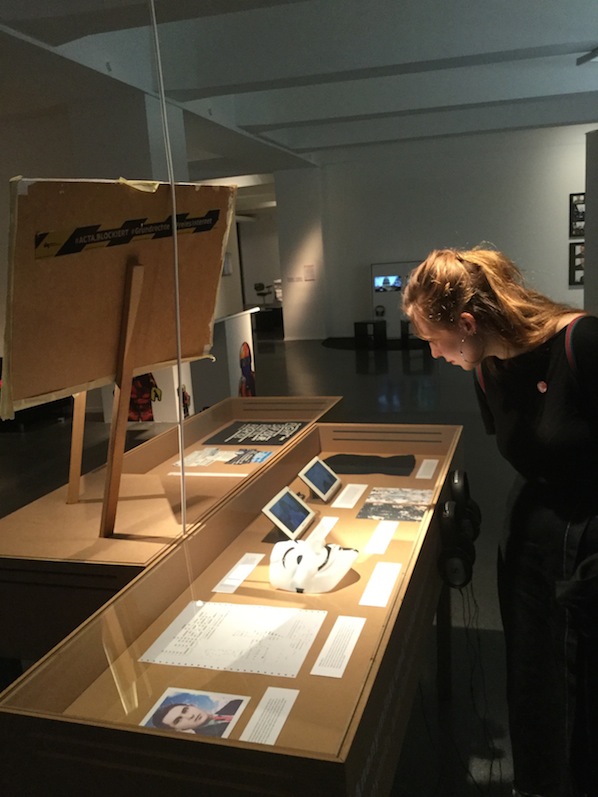

The middle ground of the exhibition shows a mix of artist activism and hacker culture. Mediengruppe Bitnik are here with a video of their Delivery for Mr. Assange. Black Transparency by Metahaven is represented through one utopian architecture model and printed wall cloths. The Peng! Collective’s Intelexit: Call-A-Spy has a telephone stand in the exhibition. The provocative sale of US votes in Vote-Auction by Ubermorgen is here as docu-installation. Etoy’s legendary Toywar is represented as well, with -in my opinion- too small a stand. Traces of many other art works and activist projects are presented in display cases, which give some more background or context to the theme. These were one of my favorite parts of the exhibition, next to the amazingly diligent and meticulous hand-drawn documentation of the Manning trial by Clark Stoeckley.

The display cases are dedicated to freedom of speech, tools of online resistance, the Netzpolitik case, anonymity and collective identities and cypherpunk and crypto-anarchism. They provide an important insight into the context within which the other practices in the exhibition exist.

Here we find Luther Blissett, the Italian born collective online identity, with a name borrowed from a former football player. The Blissett identity is related to pre-Internet art practices, in particular Neoism, and has been used for various art pranks and activist projects, particularly in Southern Europe.

Other art projects include the influential book Electronic Civil Disobedience by Critical Art Ensemble, the German hacker art collective Foebud’s battle for free speech and privacy (presented with one of Addie Wagenknecht’s anonymity glasses), and the Electronic Disturbance Theater’s Floodnet. The latter is a DDoS attack software that was used in actions for the Mexican freedom fighters the Zapatistas, by the Yes Men and for Etoy’s Toywar project.

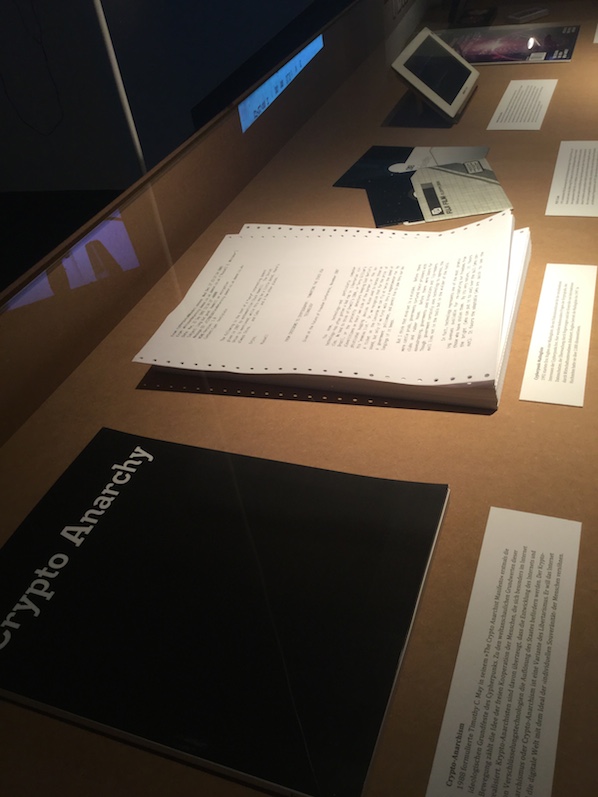

There is also a print out of the Cypherpunk mailinglist. The cypherpunk crypto-anarchist community is responsible for some of the most influential elements of the free Internet. They produced the PGP encryption technology, cryptocurrency such as Bitcoin, TOR, the idea of WIKI and torrent platforms and marketplaces like the Silk Road. Julian Assange was one of its members.

Last but not least the presentation of the Netzpolitik.org case, which covers a German censorship scandal from last year, had to be part of this exhibition. Journalists from the online magazine Netzpolitik were arrested for treason after they had published about classified Internet surveillance plans of the German secret service. A copy of the accusation letter from the state prosecutor is oddly signed with ‘Mit freundlichen Grüßen’ (‘With kind regards’).

All in all the display cases made me happy to see some of the events and works that have been so hugely influential to the development of the Internet (and thus to the development of our current culture and politics) represented in a physical cultural space. They show a side of Internet culture that is heavily underrepresented in the general discourse around new media technologies in both mainstream media and art. During a private tour of Whistleblowers & Vigilantes for visitors of the simultaneously running Hito Steyerl exhibition Inke Arns explained how for her this exhibition is long overdue as well. According to Arns the threat to our freedom through abuse of new technologies should receive as much attention in art as the anthropocene. HMKV sees it as its responsibility to do something about it.

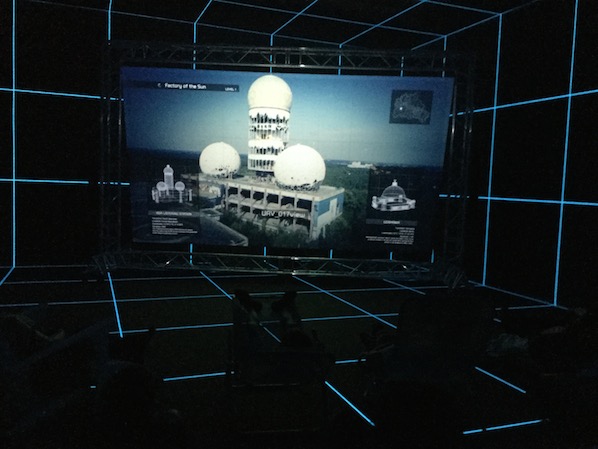

Whistleblowers & Vigilantes however does not make a straightforward statement. Its structure, both physically and content-wise, is too complex for that. This does not mean it is a bad exhibition. The bringing together of the ‘Lulz’, Anonymous, the Unabomber, net art, hacktivism, hackers and Manning, Snowden, Assange and even Breivik in one space definitely creates a lively exhibition, which cannot leave a visitor unaffected. This strange assembly then needs to be unraveled and this is where the curators take quite some risk. The addition of Hito Steyerl’s installation Factory of the Sun, an exhibition that runs simultaneously on a different floor, could help to bring the serious, crazy and light elements of the show together for that part of the audience that loses its way. In her smart playful manner Steyerl blends science fiction, humor and critique of the surveillance society in a faux holodeck cinema experience. The exhibition also includes a few live events that steer the whole into safe waters. Netzpolitik journalist Markus Beckedahl has given a presentation and so has Jens Kabisch. Kabisch wrote a text about whistleblowers that is available on the website, but this text is unfortunately only available in German. My advice to the non-German audience is to download the press kit in order to get more background information.

Whistleblowers & Vigilantes is a challenge to the audience. It asks for more reflection and time to take in than most exhibitions. After getting some more grip on it the complexity and scope of the exhibition, however, is impressive. It not only brings together many important, interesting and sometimes scary examples of contemporary forms of resistance and rebellion. What is also represented is the space of resistance and play that escapes attempts at systematic control, even in a full-on surveillance state. Once recovered from my initial shock this is what stayed with me the most. The wide-ranging documents, objects and installations reveal the system’s shadow spaces and vulnerabilities. Whistleblowers & Vigilanters differs from the flood of other art exhibitions themed around surveillance and control by reflecting on the legitimacy of online autonomous political action in general. Indirectly this means it also reflects upon the space of life that exists beyond all control. Rather than create another horror show around the future of privacy and freedom, with Whistleblower & Vigilanten we are presented with the persistence of fringe cultures and of free thinkers. For me this makes this an exhibition of hope.

Whistleblowers & Vigilantes. Figures of Digital Resistance

HMKV, Dortmund

9/4/16-14/8/16

https://www.hmkv.de/_en/programm/programmpunkte/2016/Ausstellungen/2016_VIGI_Vigilanten.php

https://www.hmkv.de/_pdf/Ausstellungsfuehrer/2016_VIGI_Kurzfuehrer_Web.pdf

There is a common sense in place about the fact that civil rights are undermined by a various amount of ‘exceptions’; exceptions which are based on a system, in which governmental decision-making processes are increasingly determined by the rule of money, or else the market. The idea of a constant ‘crisis’ leads to a ‘state of exception’. Regardless of established legal standards – in the name of financial, economical or security measurements – civil rights are constantly taken away. As a result, the social and legal relations between the different members of society and between nation states are increasingly out of balance. This creates an endless pool of watering down legal standards in postdemocratic societies and produces harmful sociopolitical asymmetries. The exhibition “As rights Go By” which took place in freiraum Q21 this spring 14th April – 12th of June 2016 aimed to exactly pinpoint these asymmetries and to unfold the irregularities of a ‘regular legal system’.

The 15 works in the exhibition, curated by Sabine Winkler, focused directly on the complex dynamics between the sources and consequences of disappearing civil rights under the global neoliberal umbrella. The show, which was very well set, had strong internal and external references and what really could struck somebody was the content. The exhibition could be experienced as a single piece, inviting the visitors to discover more more than just the visible tips of the il/legal iceberg and to bring these issues of discussion to schools, universities, festivals, shopping malls and the mainstream media. Of course this doesn’t mean not to exhibit – but it means not to stop there.

As Rights Go By was an exhibition which stays in mind ; the visitors could produce their own individual collages, making sense of the gravity of the problematics involved.

The works presented were the following:

Silvia Becks, who worked with the privileges in the art world, presented an installation which discussed how the special rights in place, like the information accessibilities, the funding resources and the leveling up of the societal status, are at the same time leading to a certain loss of legal rights.

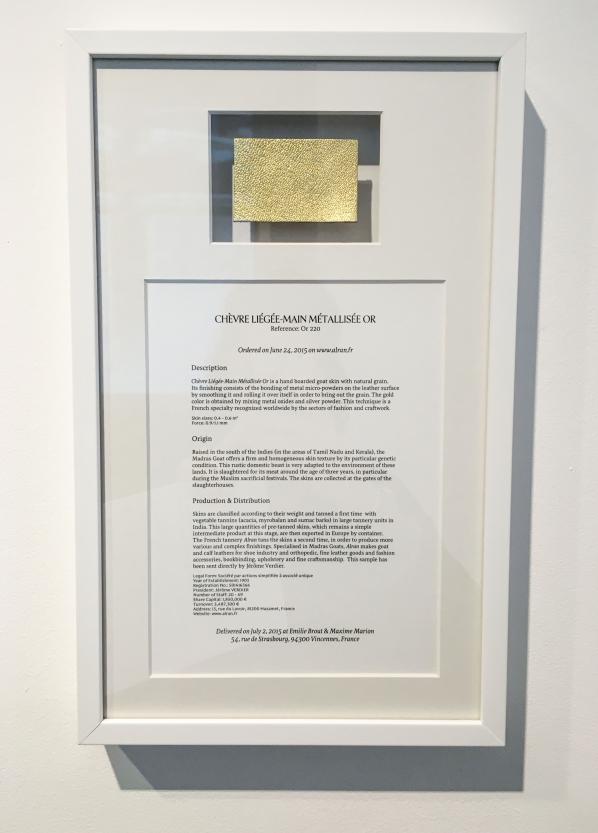

James Bridle, with his video animation “Seamless Transitions”, tried to visualize the physical spaces of the unknown arrest, the legal decision making processes and the juridical judgments involved, offering a virtual insight into the secret spaces of il/legality. His work questioned not only the surveillance strategies of physical space but also the secrecy about trading agreements and legal treaties.

George Drivas’ film‚ “Sequence Error” referred to a typical business setting where a sudden crisis has lead to a collapse. A fictional situation with a more than real deal: The crisis serves as the exception for legal rights to be erased.

Özlem Günyol and Mustafa Kunt, overlaid the portraits of the hundred wealthiest people of the world fading into one collage of one single passport image projected to the wall. A symbol for lost identities and unidentifiable legal entities.

Adelita Husni-Bey video documentation gave a very detailed insight into an urban planning process in Cairo (“Land”) including gentrification processes, which go not only against Egyptian law but actually threaten a huge amount of informal dwellings. The notion ‘participations’, in particular, delivered a learning lesson about contemporary urban development strategies and their methods.

Nikita Kadan used a “Popular Medical Dictionary” of the Soviet era in his work “Procedure Room”. Painting torture methods on ceramic plates, he showed how physical and psychological violence can be justified for a ‘higher’ political order.

The Collective Migrafona reported via Comic strips about the Austrian migration politics. Imaginary Heroes are delivering identities in order fight for political rights.

Vladimir Miladinovic’s research focused on multinational companies and their strong connections to pre- and post-war power structures. His work discussed the power relations, which are in place during setting up regulations between states and their legal standards.

In his film “1014” Yuri Pattison mixed fictional Hollywood scenes with documentary footage from the hotel room where Edward Snowden gave his first interview. The work offered an insight into the conscious loss of legal rights when fiction becomes reality and vice versa.

Lorenzo Pezzani and Charles Heller raised the question about acting against human rights while being aware of the refugee tragedies based on surveillance technology. Their forensic reconstruction of a boat disaster offered a clear insight into the thin borderline between socio political responsibilities and legal settings.

Julien Prévieux work “What Shall We Do Next? 2006-2011“ showed how close technology, law and our bodies are connected; the fact that international corporations obtain patents for specific movements such as scrolling moves on a tablet shows how unaware we are about our daily il/legal routines.

Andrea Ressi related the notion of loss onto her work; loss of living space, loss of rights, loss of freedom, loss of security and represented these losses in her pictograms with modules of exception.

Judith Siegmund’s text based installations produced discomfort. Newspaper quotations about violence against refugees were set up opposite to philosophical text fragments, triggering associations about the relation between violence and competitiveness assuming that people take advantages from others who find themselves in a lawlessness situation.

Lina Theodorou’s project was one of the most intriguing works in the show. Her board game club offered a playful insight into the crisis in Greece and the social and legal consequences of austerity measurements up leading to losing well established rights. The setting would be funny if it wouldn’t be real.

Carey Youngs’ work “Obsidian Contract” transformed the visitor into an affiliate. The public space and the legal space were imagined and lost rights were reconstructed fictionally while watching the contract text through a mirror.

The exhibition did not refer directly to any political action, artivism, hacktivism or any other form of resistance but it implied the embedded hegemonic power structures pointing where it all begins.The exhibition was not a subversive act but it showed how subversion as an act of societal struggle became something illegal. Up to around 15 years ago the notion of ‘subversion’ was relatively easy to connect to counter-cultural productions. But a subversive act wasn’t nesessarily illegal – it was done in a grey shadow light between established settings in order to shake up presumably fixed sociopolitical surroundings. An unclear task under clear conditions.

In the era of global capitalist hegemony, shadows turned straight into black or white areas; no grey is involved anymore. Subversion dissolved into two parts: the legal one, which consists of what is now understood as innovation – or ‘creativity’ as the motor for an ‘idea based economy’- and the illegal one, what now labels all the ‘unwanted’ realities: terror, refugees, homeless; etc. Therefore subversive thinking and acting is no longer part of a cultural discourse but is simply illegal. Why?

The unlimited governmental practices which are today in place show that decisions are made as it happens in the financial markets; everything becomes a derivate, something to speculate with. The future has consequences on the present before anything happens. In times where potentials are seen as threats, the subversive process is turned upside down: subversions themselves become clearly defined and legal settings are turned into grey areas. A clear task under unclear conditions.

The exhibition encouraged, motivated and gave an insight into the power of rights including the absence of it. Focusing on how rights are either set or (il/legally) undermined by their exceptions and on how well these tendencies are sold as (inter)national necessities, it underlined the urge for a collective awareness of these i/legal practices and their consequences.

‘As Rights Go By’ was a very important exhibition; as mentioned above – what was visible was just the tip of the iceberg. As in many shows which include a huge amount of artistic research, a retrospective view in the future will show that this is just the beginning of a different kind of political engagement which most of all is a call for action.

Rights go by and are not falling from the sky.

Featured Image: With 69.numbers.suck by Browserbased

Athens Digital Arts Festival (ADAF) returned this year on the 19th to the 22nd of May with its 12th edition to bring Digital Pop under the microscope. Do machines like each other? Does the Queen dream of LSD infused dreams and can a meme be withdrawn from the collective memory?

Katerina Gkoutziouli, an independent curator and this year’s program director together with a team of curators proposed a radical rethinking of digital POP, placing the main focus on the actors of cultural production. From artists to users and then to machines themselves, trends and attitudes shift at high speed and the landscape of pop culture is constantly changing. What we consider POP in 2015 might be outdated in 2016, as the Festival’s program outlines, and that is true. But even so, in the land of memes, GIFs, likes, shares and followers what are the parameters that remain? ADAF’s curatorial line took it a step further and addressed not just the ephemerality of digital POP. It tackled issues related to governance and digital colonialism, but in a subtle and definitively more neon way.

450 artists presented their work in a Festival that included interactive and audiovisual installations, video art, web art, creative workshops and artist talks. Far from engaging in the narrative of crisis as a popular trend itself though, ADAF 2016 was drawn to highlighting the practices that reflect the current cultural condition. And the curated works were dead-on at showcasing those.

How are we “feeding” today’s digital markets then? Ben Grosser’s sound and video installation work “You like my like of your like of my status” screened a progressive generative text pattern of increasingly “liking” each others “likes”. Using the historic “like” activity on his own Facebook account, he created an immersive syntax that could as well be the mantra of Athens Digital Arts Festival 2016.

Days before the opening of the exhibition, Ben Grosser was asked by to choose the image that defines pop the most. No wonder, he replied with the Facebook “like” button. What Ben Grosser portrayed in his work is the poetics of the economy of corporate data collectors such as Facebook with its algorithmic representation of the “Like” button as the king pawn of its toolkit, that transform human intellect as manifested through the declaration of our personal taste and network into networking value.

Speaking of taste, what about the aesthetics? From Instagram and Snapchat filters to ever updated galleries of emoticons available upon request, digital aesthetics are infused with social significance. In the Queen of The Dream by Przemysław Sanecki (PL) the British politics and the Royal tradition were aestheticized by the DeepDream algorithm of Google. In an attempt to relate old political regimes and established technocracies, the artist places together hand in hand the political power with the algorithmical one, pointing out that technologies are essential for ruling classes in their struggle to maintain the current power balance. The representation of the latter was placed there as a reminder that it’s dynamic is to obscure this relation, rather than illuminate it.

However, could there be some space for some creative civil disobedience? Browserbased took us for a stroll in the streets of Athens, or better to say in the public phone booths of Athens. There, the city scribbles every day its own saying, phone numbers for a quick wank, political slogans, graffiti, tags and rhymes. With 69.numbers.suck Browserbased mapped the re-appearance and cross-references of those writings, read this chaotic network of self-manifestation and reproduced it digitally in the form of nodes. Out there in the open a private network emerged, nonsensical or codified, drawn and re-drawn by everyday use, acceptance and decline.

Can virality kill a meme? Yes, there is a chance that the grumpy cat would get grumpier once realized that its image would be broadcasted, connoted and most possibly appropriated by thousands. But how far would it go? The Story of Technoviking by Matthias Fritsch (DE) was showcased at the special screenings session of the Festival. It is a documentary that follows an early successful Internet meme over 15 years from an experimental art video to a viral phenomenon that ends up in court. Once the original footage was uploaded, it remained somehow unnoticed until some years later that it was sourced, shared, mimified, render into art installation, even merchandised by users. As a cultural phenomenon with high visibility it fails to be deleted both from servers around the world and from the collective memory even though that this was a court’s decision. In his work Matthias Fritsch mashes up opinions of artists, lawyers, academics, fans and online reactions marking the conflict between the right of the protection of our personality to the fundamental right of free speech and the direction towards which society and culture will follow in the future in regard to the intellectual property.

It’s the machines alright! Back in the days of Phillip K. Dick’s novels the debate was set over distinctions between human and machine. Since then the plot has thickened and in memememe by Radamés Ajna (BR) and Thiago Hersan (BR) things were taken a step further. This installation, situated in one of the first rooms of the exhibition, of two smartphones seemingly engaged in a conversation between them through and incomprehensible language built on camera shots and screen swipes is based on the suspicion that phones are having more fun communicating than we are. Every message is a tickle, every swipe a little rub. In memememe the fetichized device was not just a mechanic prosthesis on the human body, it was an agent of cultural production. The implication that the human might not cause or end of every process run by machines was promoted to a declaration. Ajna and Hersan have built an app that allows as a glimpse into the semiotics of the machine, a language that we can see but we can’t understand.

How many GIFs fit in one hand? If one were to trace all subcultures related to pop culture, then he or she would have to stretch time. Since they are multiplying, expiring and subcategorized not by theorists but by the users themselves and with their ephemerality condemning most of which into a short lived glory. Lorna Mills (CA) explores the different streams in subcultures through animated GIFs and focuses on found material of users who perform online in front of video cameras. In her installation work Colour Fields she is obsessed on GIF culture, its brevity, compression, technical constraints and its continued existence on the Internet.

Global pop stars, a blueprint on audience development. Manja Ebert (DE) in her interactive video installation ALL EYES ON US, one of the biggest installations of the Festival, embarked on an artistic analysis of the global pop star and media phenomenon Britney Spears. Based on music videos of the entertainer that typecast Spears into different archetypical female characters, Ebert represented each and every figure by a faceless performer. All nine figures were played by a keyboard, thus allowing the users to recompose these empty cells decomposing Spears as a product into its communicational elements.

Going through the festival, more related narratives emerged. Privacy and control, the representation of the self and the body were equally addressed. People stopped in front of the Emotional Mirror by random quark (UK/GR), to let the face recognition algorithm analyze their facial expression and display their emotion in the form of tweets while they were photographing and uploading in one or more platforms the result at the same time.

Τhe Festival presented its program of audiovisual performances at six d.o.g.s. starting on May 19 with the exclusive event focus raster-noton, featuring KYOKA and Grischa Lichtenberger.

ADAF 2016 brought a lot to the table. Its biggest contribution though lies in offering a great deal of stimuli regarding the digital critical agenda to the local digital community. ADAF managed to surpass the falsely drawn conception of identifying the POP digital culture just as a fashionable mainstream. On the contrary it highlights it as a strong counterpoint.

Featured Image: Julian Rosefeldt Manifesto, 2014/2015 ©VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016

Entering the darkened gallery space in the side wing of Berlin`s Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, the visitor first encounters a projection showing the close-up of a fuse cord burning in the dark. Shot out of focus its sparks are flying in slow motion, a firm clear female voice comes in beginning a monologue which includes familiar lines and passages: “I am against action; for continuous contradiction, for affirmation too, I am neither for nor against and I do not explain because I hate common sense. […] All that is solid melts into air. […] I am writing a manifesto because I have nothing to say.”. The fuse cord gradually exstinguishes without leading to an explosion.

Quoting parts of the manifesto of the Communist Party, Tristan Tzara`s Dada Manifesto as well as pieces of Philippe Soupault`s “Literature and the Rest”, the 4-minute video in its function as “Prologue” sets the tone of Julian Rosefeldt`s exhibition “Manifesto”. The opulent 13-channel installation is a homage to the textual form of the artist manifesto – in Rosefeldt´s words “a manifesto of manifestos”. Inspired by the research for his previous work “Deep Gold”, Rosefeldt began looking further into the genre and its poetics. From about sixty popular art manifestos – the earliest from 1848, the latest from 2004 – he collaged twelve new powerful and entertaining manifestos. Said manifestos serve as the source for each of the thirteen videos (a prologue and 12 scenarios) delivered and performed as monologues by Oscar-winning actress Cate Blanchett.

In every film, an extremely versatile Blanchett morphs into another role: From homeless man to broker, newsreader to punk, puppeteer or scientist. Obviously these roles do not represent the manifesto`s authors, they rather show contemporary types chosen by the artist to counterpoint or stress the ideas and attitudes of the text passages they are reciting. As a CEO at a private party, Blanchett is orating in front of an affluent audience, praising “the great art vortex”. Continuing her celebratory speech, she changes the tone to amuse her crowd quoting more passages of the Vorticist manifesto: “The past and future are the prostitutes nature has provided.”. Polite laughter, glasses are clinging. Another scene shows a bourgeois American family sitting at the dining table about to say grace. Blanchett in the role of the conservative mother is leaning her head, folding her hands but instead of the usual blessing, she begins to fervently recite Claes Oldenburg`s Pop Art Manifesto which consists of a series of propositions starting with “I am for an art …” and includes such gems as: “I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum.” or “I am for the white art of refrigerators and their muscular openings and closings.”.

All 10-minutes-long videos in the exhibition work according to the same principle: the art manifesto collages are delivered as monologues by Blanchett at first in voice-over introducing the scene, then in filmed action and at its climax as speech to camera. Shown in parallel and installed without spatial division, the monologues interfere with one another, and the visitor is always confronted with more than one narration. While watching Blanchett in the role of a primary school teacher softly correcting her pupils quoting Jim Jarmusch: “Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination.”, one can at the same time hear her in the role of an eccentric choreographer slamming the rehearsal of a dance ensemble with the words of Yvonne Rainer, “No to style. No to camp. No to seduction of spectator by the wiles of the performer.” From somewhere else the sound of a brass band appears, introducing the funeral scene in which Blanchett is holding a eulogy consisting of a collage of several Dada manifestos. Sounds and voices overlap and compete for attention until a point in each video when all characters in sync turn towards the camera falling into a chorus-like liturgical chant, filling the dark gallery space with a polyphony – or cacophony – of interfering monologues. It is an impressive experience, but simultaneously the installing method makes it very hard to concentrate on words and ideas expressed in the manifestos.

In general, the exhibition and each of the videos are aesthetically pleasing and entertaining to watch, which is equally due to the scenography with its amusing artifices, the strong selection of text passages as well as its its star power. Rosefeldt´s opulent, multi-layered and choreographed installation blurs the lines between narrative film and visual art. Commissioned by a unique group of partners that include the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Hamburger Bahnhof and Hanover `s Sprengel Museum, “Manifesto” is in no way inferior to most cinematic productions made in Hollywood. But here´s the problem: Although Rosefeldt claims in his intro text and again in the video interview accompanying the exhibition online, that he wanted to emphasize and celebrate the literary beauty and poetry of artist manifestos, the texts are outshined by the cinematic staging of actress, setting and choreography of space. The attention of the viewer is drawn to speaker and theatrical performance, instead of focusing on the poetics and messages contained in each one of the thirteen art manifesto texts.

Another stylistic element that Rosefeldt uses attempting to highlight the manifesto texts is creating tension between text and image. Most of the settings and characters in “Manifesto” deliberately break with the performed text, which can for example be witnessed in the scene of the conservative mother reciting Oldenburg. Both were conceived by Rosefeldt to intensify the contrast between the rebellious rhetoric, idealism and radical notions of the manifesto form and the realities of today´s world. This does not work out at all times, sometimes the performances seem so exaggerated that they tip over and border on the ridiculous, the staging turns into travesty. It reinforces the impression that the exhibition is not in the first place about the texts, their content and reflective presentation, but rather aimed at the maximum achievable effect. But Rosefeldt succeeds in his intention to show how surprisingly current the demands of some of the manifestos presented are, most of them written in the 20th century. A century which was defined by historian Eric Hobsbawm as the short century and “The Age of Extremes” which saw the disastrous failures of state communism, capitalism, and nationalism. The world has more or less continued to be one of violent politics and violent political changes, and as Hobsbawm writes most certainly will continue like that.

So it is no wonder that the manifesto, also serving as a signal of crisis, is experiencing a revival. With the internet as an easy means of dissemination, the manifesto form has been revisited by a great number of single artists and artist activist groups, it spread out in every niches of the art world, and was adapted by academia and beyond. So when Rosefeldt in his statements nostalgically praises texts from the “Age of Manifestos” and states that he misses this thoughts focus in today´s discourses, one cannot but wonder if he missed the current debates sparked by texts like the “#ACCELERATE MANIFESTO for an Accelerationist Politics”, “The Coming Insurrection” by the anonymous Invisible Committee, “Xenofeminism: A Politics for Alienation” authored by Laboria Cuboniks collective or texts by individual artists like Hito Steyerl which became important points of reference.

Rosefeldt´s selection of manifesto texts seems random and inconsistent with his expressed intentions: Why was the manifesto of the Communist party included in an assortment of art manifestos? Or why were Jim Jarmusch`s “Golden Rules of Filmmaking” from 2002 and Sturtevant`s ”Man is Double Man is Copy Man is Clone” from 2004 chosen in a selection concentrating on 20st century texts? Instead of concentrating on canonic art movements and a few single artists, it would been more convincing to reflect how the art field since then has been trying to re-position itself within the shifting boundaries of activism, technology and aesthetics. With a subjective selection of simply “the most fascinating, and also the most recitable” texts, “Manifesto” is caught up in an acritical nostalgia to the disadvantage of coherence and focuses rather on text as performance as on persuasive messages and reflection.

As Mary Ann Caws in her anthology “Manifesto: A Century of Isms” states, the manifesto is “a document of an ideology, crafted to convince and convert”. Naturally, there also is some discomfort with or even suspicion of the manifesto form. The obvious example being the Futurists, who in their manifesto glorified speed, machinery and war. Their text largely influenced the ideology of fascism which they supported in the run up to World War II. In the exhibition, the macho-male tone of the Futurist manifestos fittingly and amusingly is performed by Cate Blanchett in the role of a female stockbroker. Rosenfeldt met Marinetti`s dream of an engineered society showing us the violent creator and destroyer financial capitalism.

Julian Rosefeldt. Manifesto

Curated by Anna-Catharina Gebbers & Udo Kittelmann

10.02.2016 to 10.07.2016

Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin

http://www.smb.museum/en/museums-institutions/hamburger-bahnhof/exhibitions/detail/julian-rosefeldt-manifesto.html

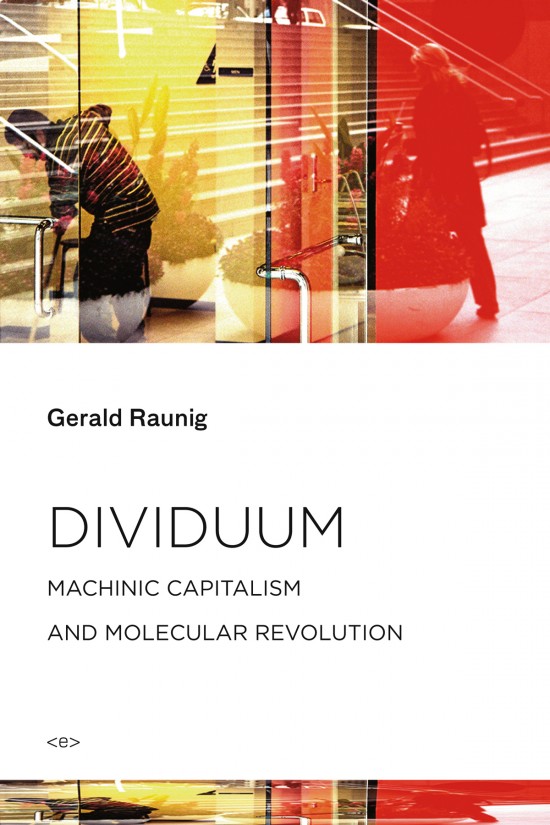

Featured Image: Gerald Raunig, Dividuum, Semiotext (e)/ MIT Press

Gerald Raunig’s book on the concept and the genealogy of “dividuum” is a learned tour de force about what is supposed to be replacing the individual, if the latter is going to “break down” – as Raunig suggests. The dividuum is presented as a concept with roots in Epicurean and Platonic philosophy that has been most controversially disputed in medieval philosophy and achieves new relevance in our days, i.e. the era of machinic capitalism.

The word dividuum appears for the first time in a comedy by Plautus from the year 211 BC . “Dividuom facere” is Ancient Latin for making something divisible that has not been able to be divided before. This is at the core of dividuality that is presented here as a counter-concept to individuality.

Raunig introduces the notion of dividuality by presenting a section of the comedy “Rudens” by Plautus. The free citizen Daemones is faced with a problem: His slave Gripus pulls a treasure from the sea that belongs to the slave-holder Labrax and demands his share. Technically the treasure belongs to the slave-holder, and not to the slave. Yet, in terms of pragmatic reasoning there would have been no treasure if the slave hadn’t pulled it from the sea and declared it as found to his master. Daemones comes up with a solution that he calls “dividuom facere”. He assigns half of the money to Labrax, who is technically the owner, if he sets free Ampelisca, a female slave whom Gripus loves. The other half of the treasure is assigned to Gripus for buying himself out of slavery. This will allow Gripus to marry Ampelisca and it will also benefit the patriarch’s wealth. Raunig points out that Daemones transfers formerly indivisible rights and statuses – that of the finder and that of the owner – into a multiple assignment of findership and ownership.

We will later in the book see how Raunig sees this magic trick being reproduced in contemporary society, when we turn or are turned into producer/consumers, photographers/photographed, players/instruments, surveyors/surveyed under the guiding imperative of “free/ voluntary obedience [freiwilliger Gehorsam]”.

The reader need not be scared by text sections in Ancient Greek, Ancient Latin, Modern Latin or Middle High German, as Raunig provides with translations. The translator Aileen Derieg must be praised for having undertaken this difficult task once more for the English language version of the book. It can however be questioned whether issues of proper or improper translation of Greek terms into Latin in Cicero’s writings in the first century BC should be discussed in the context of this book. This seems to be a matter for an old philology publication, rather than for a Semiotext(e) issue.

It is, however, interesting to see how Raunig’s genealogy of the dividuum portraits scholastic quarrels as philosophic background for the development of the dividuum. With the trinity of God, Son of God and the Holy Spirit the Christian dogma faced a problem of explaining how a trinity and a simultaneous unity of God could be implemented in a plausible and consistent fashion. Attempts to speak of the three personae (masks) of God or to propose that father, son and spirit were just three modes (modalism) of the one god led to accusations of heresy. Gilbert de Poitiers’ “rationes” were methodological constructions that claimed at least two different approaches to reasoning: One in the realm of the godly and the other in the creaturely realm. Unity and plurality could in this way be detected in the former and the latter realm respectively without contradicting each other. Gilbert arrives at a point where he concludes that “diversity and conformity are not to be seen as mutually exclusive, but rather as mutually conditional.” Dissimilarity is a property of the individual that forms a whole in space and time. The dividual, however, is characterized by similarity, or in Gilbert de Poitiers’ words: co-formity. “Co-formity means that parts that share their form with others assemblage along the dividual line. Dividuality emerges as assemblage of co-formity to form-multiplicity. The dividual type of singularity runs through various single things according to their similar properties. … This co-formity, multi-formity constitutes the dividual parts as unum dividuum.”

In contemporary society the one that can be divided, unum dividuum, can be found in “samples, data, markets, or ‘banks’”. Developing his argument in the footsteps of Gilles Deleuze, Gerald Raunig critically analyses Quantified Self, Life-Logging, purchases from Amazon, film recommendations from Netflix, Big Data and Facebook. “Facebook needs the self-division of individual users just as intelligence agencies continue to retain individual identities. Big Data on the other hand, is less interested in individuals and just as little interested in a totalization of data, but all the more so in data sets that are freely floating and as detailed as possible, which it can individually traverse.” In the beginning “Google & Co. tailor search results individually (geographical position, language, individual search history, personal profile, etc.” The qualitative leap from individual data to dividual data happens when the ”massive transition to machinic recommendation [happens], which save the customer the trouble of engaging in a relatively undetermined search process.” With this new form of searching the target of my search request is generated by my search history and by an opaque layer of preformatted selection criteria. The formerly individual subject of the search process turns into a dividuum that is asking for data and providing data, that is replying to the subject’s own questions and becomes interrogator and responder in one. This is where Gilbert de Poitiers’ unum dividuum reappers in the disguise of contemporary techno-rationality.

Raunig succeeds in creating a bridge from ancient and medieval texts to contemporary technologies and application areas. He discusses Arjun Appadurai’s theory of the “predatory dividualism”, speculates about Lev Sergeyevich Termen’s dividual machine from the 1920s that created a player that is played by technology, and theorizes on “dividual law” as observed in Hugo Chávez’ presidency or the Ecuadorian “Constituyente” from 2007. The reviewer mentions these few selected fields of Raunig’s research to show that his book is not far from an attempt to explain the whole world seamlessly from 210 BC to now, and one can’t help feeling overwhelmed by the text.

For some readers Raunig’s manneristic style of writing might be over the top, when he calls the paragraphs of his book “ritornelli”, when he introduces a chapter in the middle of his arguments that just lists people whom he wants to thank, or when he poetically goes beyond comprehensiveness and engages with grammatical extravaganzas in sentences like this one: “[: Crossing right through space, through time, through becoming and past. Eternal queer return. An eighty-thousand or roughly 368-old being traversing multiple individuals.”

It is obvious that Gerald Raunig owes the authors of the Anti-Œdipe stylistic inspirations, theoretical background and a terminological basis, when he talks of the molecular revolutions, desiring machines, the dividuum, deterritorialization, machinic subservience and lines of flight. He manages to contextualise a concept that has historic weight and current relevance within a wide field of cultural phenomena, philosophical positions, technological innovation and political problems. A great book.

Dividuum

Machinic Capitalism and Molecular Revolution

By Gerald Raunig

Translated by Aileen Derieg

Semiotext(e) / MIT Press

https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/dividuum

Artists to my mind are the real architects of change,

and not the political legislators who implement change after the fact

(William S. Burroughs)

A large-scale model of a CCTV camera made from recycled cardboard peers through the window of the Seventeen Gallery out onto Belmont Street in Aberdeen, alive with passers by. This is the main piece of Under New Moons, We Stand Strong (2016), the project conceived and designed by Teresa Dillon to prompt reflections on solidarity, literacy and symbolism within digital civic governance.

If one gets close enough, it is evident that the eye of this camera is blind for there is no actual watching and recording apparatus inside. Still, the sensation of being watched remains. Bird spikes are mounted on top of the camera. The first thing one notices is the scale of the model: for the first time, what is an almost impalpable and invisible presence (surveillance technologies tend to be increasingly difficult to spot in the urban space) gets amplified, taking a physical presence that invites us to explore our personal relationship with surveillance and the multiple technologies that embody it.

The enlarged cardboard CCTV camera not only reminds passers-by of surveillance, its visual presence, eye to eye and the size of an other, functions to interpellate the viewer as an active gazer. Instead of us being the object of its gaze, the large-scale model allows us to look at the CCTV camera up-front. The exchange of gazes between the two subjects, the surveillance apparatus and ourselves, occurs on an equal level: we occupy a position that is not anymore subservient to the mechanical all-seeing-eye. In the act of looking at the CCTV cardboard model, we can also recognise our own complicit capacity to become overseers.

Teresa Dillon’s installation invites us to become aware of the change occurred in contemporary social and technological developments in the relationship between surveillance and society. This change is subtler than it might appear at first. The Panopticon, Bentham’s prison architecture, was discussed by Foucault in his Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975) as an exemplar, among others examined in the book, of the mechanisms of social control that become permanent and interiorised. The prisoners, in fact, have no need to be actually watched, they know that they might be being watched. The condition of being potentially under surveillance transforms the dynamics of the gaze, causing an interiorisation of the watchtower’s gaze, in such a way that the prisoner becomes her own overseer.

Surveillance studies have pointed out how the Foucauldian metaphor of the Panopticon fails to describe the multi-faceted contemporary figurations of surveillance. It is not anymore a matter of keeping the prisoners in a certain space, but much more of keeping them away. The movement from the Panopticon to the Banopticon, for example, exemplifies the attempt to use profiling techniques to determine who should be placed under surveillance for security purposes. The Banopticon can be described as the attempt to keep away certain social groups (asylum seekers, migrants, suspected terrorists) in the context of global security and border control. This ban, interestingly, is not exercised exclusively upon certain groups or in extraordinary circumstances, but also upon those individuals who do not have the resources (for example credit cards and smartphones) to promptly respond to the enticement of consumer spaces such as shopping malls.

We need to take responsibility for the way in which we exercise the power to look. This was the sense of the two talks arranged as part of Urban Knights, a program of events conceived to provoke and promote practical approaches to urban governance and city living by bringing together people who are actively producing alternatives to our given city infrastructures, norms and perceptions. Programmed during the opening of Under New Moons, We Stand Strong, the first talk saw Keith Spiller, a lecturer in criminology at Birmingham City University, discussing state surveillance and individual rights in the context of his practical experiences of accessing CCTV data in London. Heather Morgan, a Research Fellow at the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, presented her on-going research on sousveillance (in the context of health self-monitoring wearable technologies). In the middle of our smart cities, caught up in the illusion of being in control of smart technologies we are actually constructing our own prison.

Dillon’s interventions successfully unfold what the two talks left implicit at theoretical level, that is the passage from Foucauldian surveillance to “surveillant assemblage”. Deleuze’s and Guattari’s concept of surveillant assemblage makes visible processes in which information is first abstracted from human bodies in data flows and then reassembled as “data doubles” (Deleuze and Guattari 1987). Thus, a new type of body is formed, whose flesh is pure information transcending corporeality. The body is an assemblage, comprised of component parts and processes that need to be observed. Moving away from a hierarchical top-down gaze, in a rhizomatic-fashion, surveillance expands in multiple fractured forms.

Going back to Dillon’s installation, on the gallery wall there is a digital print portraying a snowy owl in mid-air flight. This is a special edition print related to an episode on January 3rd, 2016 in Quebec, where a CCTV camera captured a stunning image of a snowy owl in mid-air flight. Four days later the images were tweeted by Quebec’s Transport Minister and went viral, turning the snowy owl into an “Internet star”. In Greek mythology the owl represents or accompanies Athena, the goddess of wisdom – and military strategy. Curiously, the next generation of surveillance technologies developed by the United States military bears the names of Greek mythological creatures. Argus Panoptes, which recalls the all-seeing giant monster with a hundred eyes, is a monitoring system that allows the constant surveillance of a city. Gorgon Stare, an array of nine cameras attached to an aerial drone, takes the name of the monstrous feminine creature whose appearance would turn anyone who laid eyes upon it to stone.

The owl is a highly metaphorical and yet ambiguous presence in the exhibition. On the one hand, the owl symbolises knowledge, wisdom and perspicacity. With its appearance, “flying only with the falling of the dusk” to paraphrase and transpose the famous passage from Hegel where the owl incarnates the appearance of philosophical critique and appraisal, the owl of Minerva (the Roman goddess identified with Athena) makes explicit the ideas and beliefs that drove an era but could not be fully articulated until it was over. Therefore, the owl is revealing something to us about our own epoch – it is our task to decipher the content of the message.

On the other hand, the owl is also the physical medium through which collaborative interspecies strategies of resistant actions to surveillance can be organised. Dillon’s techno-civic intervention, as the artist herself calls her work, is ideally connected to another artistic project, Pigeonblog, made by Beatriz da Costa, artist, academic and activist, member of the Critical Art Ensemble and graduate student of philosopher and science and technology scholar Donna Haraway. Pigeonblog was a grassroots initiative designed to collect and spread information about air quality to the public. Pigeons were equipped with small air pollution sensing devices capable of gathering data on pollution levels. The data could be then visualised and accessed by means of Internet (da Costa and Kavita 2008). Da Costa’s Pigeonblog was inspired by a photograph depicting a technology developed in Germany during wartime but then never implemented: a small camera, carried by a pigeon and set on a timer, was designed to take pictures at regular intervals of time as pigeons flew over specific regions of interest – possibly military targets. Pigeons were participating agents in this early surveillance technology system. Da Costa resuscitated that idea to create a surveillant assemblage formed by a living animal and technology but with civilian and activist goals.

By means of this mythological creature, the owl, Teresa Dillon asks us to learn to look at those technologies of surveillance, to re-adjust our gaze in order to be ready to face them upfront. The role played by mythology is evident not only in the installation but in the procession that accompanied the exhibition on Saturday May 7th. The public were invited to gather together and take part in a “forensic anthropological walk”, as the artist labelled it, throughout the city of Aberdeen, with participants holding hand-held models of two-dimensional CCTV cameras. Stopping in front of the CCTV cameras encountered in Castle Square during the walk, the artist revisited the world history of CCTVs, starting from the first documented use of surveillance cameras in Germany in 1942 for the documentation of Test Stand VII, the V-2 rocket testing facility, through the introduction of CCTVs in the urban landscape in the US in 1968, and more recent examples of surveillance technologies in the UK.

Dillon blends story-telling techniques with an emotional urban cartography created by means of walking together. Namely, the walk cannot be described in the guise of a city tour: the performative element transformed the walk into a procession, a collective rite, consumed on the Aberdeen beach where the paper cameras were set alight by participants. The history of surveillance technologies is in fact interwoven with mythological, symbolic and ritual elements, from the owl to the closing ceremony on the beach. Like in Cities of the Red Night, written by Beat Generation novelist William S. Burroughs, Dillon’s multiple interventions combines history with rituals and performance to evoke magical elements, doomsday scenarios and our phobias about the powers that control and enslave us.

The different interventions conceived and designed by the artist (the artwork itself, the performance, the walking tour through the city, the talks that accompanied the opening of the exhibition) can be read as artistic enactments of the cut-up and fold-in literary technique used to re-arrange and combine the pieces of a text to form new narratives. The technique can be traced back to the Dadaists of the 1920s. It was then popularised by Burroughs in the 1960s as a radical and creative method of socio-political subversion. It is evident that the cut-up and fold-in technique can be applied to contexts other than literature as Dillon demonstrates. It helps overcoming conventional associations (in this case, surveillance as a merely technological apparatus) to create new ones (the literacy infrastructure of surveillance), transforming the reader/player/visitor from a passive consumer of other people’s ideas into the architect of her own knowledge and action.

Under New Moons, We Stand Strong allows citizens to become not only more aware of the technological power infrastructure at work in our cities but also to learn how to read it, confront it, possibly resist it. The beach, at the outskirt of the urban space, a liminal site, nowadays often associated with the refugees crisis, becomes a space of freedom and catharsis. To set the cardboard cameras alight is, simultaneously, an act imbued with mythology – Prometheus’ gift of fire, the first techne, to humankind for their survival – and a collective gesture of transformation and renewal. Having freed ourselves from the idols, from all-seeing eyes, we can stay up-front, together, as a community, to face the darkness of our time.

Seventeen, Art Centre, 17 Belmont St, AB10 1JR, Aberdeen

Supported by Scotland’s Festival of Architecture, Peacock Arts Centre & Aberdeen City Council

Date: Thurs 5 – Sat 28 May 2016

Location: Seventeen, 17 Belmont St, AB10 1JR, Aberdeen

Opening: Thurs, 5 May, 6pm with special edition of Urban Knights

Procession: Sat 7 May, 8pm from Seventeen, 17 Belmont St, AB10 1JR, Aberdeen

Credits

Model & assistance: Jana Barthel

Commissioned by: Festival of Architecture, Scotland, 2016; Peacock

Visual Arts, Aberdeen & Seventeen Gallery, Aberdeen

What does the comic book heroine Wonder Woman have to do with the lie detector? How is the Situationists’ dérive connected to Google Map’s realtime recordings of our patterns of movement? Do we live in Borges’ story “On Exactitude in Science” where the art of cartography became so perfect that the maps of the land are as big as the land itself? These are the topics of the Nervous Systems exhibition. Questions that are pertinent to the state of the world we are in at this moment.

The motto “Quantified life and the social question” sets the frame. Science started out as a the quantification of the world outside of us, but from the 19th century onwards moved towards observing and quantifying human behaviour. What are the consequences of our daily life being more and more controlled by algorithms? How does it change our behaviour if we are caught up in a feedback loop about what we are doing and how it relates to what others are doing? Does this contributed to more pressure towards a normalized behaviour?

These are just some of the questions that come to mind wandering around the densely packed space. You have to bring enough time when you visit “Nervous systems” – it is easy to spend the whole day watching the video works and reading the text panels.

There are three distinct parts: the Grid, Triangulation and the White Room. Each treats these questions from a different perspective. The Grid is the art part of the show and features younger artists like Melanie Gilligan with her video series “The Commons Sense” where she imagines a world where people can directly experience other people’s feelings. In the beginning this “patch” allows people to grow closer together, increasing empathy and togetherness, but soon it becomes just another tool for surveillance and optimizing of work flows in the capitalist economy – an uncanny metaphor of the internet.

The Swiss art collective !Mediengruppe Bitnik rebuilt Julian Assange’s room in the Ecuadorian Embassy – including a treadmill, a Whiskey bottle, Science Fiction novels, mobile phone collection and server infrastructure – all in a few square metres. The installation illustrates the truism that history is made by real people who eat and drink and have bodies that are existing outside of their role they are known for. Which is exactly why Assange is confined since 2012 without being convicted by a regular court.

The NSA surveillance scandal does not play a major part in the exhibition as the curators – Stephanie Hankey and Marek Tuszynski from the Tactical Technology Collective and Anselm Franke, head of the HKW’s Department for Visual Arts and Film – rather concentrate on the evolution of methods of quantification. For this reason we are not only seeing younger artists who directly deal with data and its implications but go back to conceptual art and performance in the 1970s and earlier.

The performance artist Vito Acconci is shown with his work “Theme Song” from 1973 and evokes the Instagram and Snapchat culture of today by building intimate space where he pretends to secrets with the audience. Today he could be one of the Youtube ASMR stars whispering nonsense in order to trigger a unproven neural reaction.

Harun Farocki’s film “How to live in the FRG” on the other hand shows how society already then used strategies of optimization in order to train the human material for the capitalist risk society.

Triangulation is the method to determine the location of a point in space by measuring the angles from two other points instead of directly measuring the distance. As a method it goes back to antiquity. In the exhibition the Triangulation stations give a theoretical and cultural background to the notion of a quantified understanding of the world. Here the exhibition give a rich historical background mixing stories about the UK mass observation project where volunteers made detailed notes about the dancing hall etiquette with analyses of mapping histories and work optimization.

The triangulations in the exhibiton are written by eminent scholars, activists and philosophers. The legal researcher Laurence Liang writes about the re-emerging forensic techniques like polygraphs and brain mappings that have their roots in the positivism of the nineteenth century. Other triangulations are about Smart Design (Orit Halpern), algorithms, patterns and anomalies (Matteo Pasquinelli) and quantification and the social question where Avery F. Gordon together with curator Anselm Franke speaks about the connection of governance, industrial capitalism and quantification.

“Today’s agitated state apparatuses and overreaching institutions act according to the fantasy that given sufficient information, threats, disasters, and disruptions can be predicted and controlled; economies can be managed; and profit margins can be elevated,” the curators say in their statement. We see this believe everywhere – the state, the financial sector, in the drive towards self-optimization. A lot of the underlying assumptions can be traced back to the 19th century – the believe that if we have enough information we can control everything.

Like Pierre Laplace and his demon we believe that if we know more we can determine more. The problem is that knowing is only possible through a specific lens and context so that we become caught up in a feedback loop that only confirms what we already know to begin of. Most notably this can be seen in the concept of predictive policing which is also present in the triangulation part of the exhibition. Algorithms only catch patterns that are pre-determined by the people who program them.

Going through The Grid of the art works (the exhibition architecture by Kris Kimpe masterfully manifests a rectangular gridlike structure in the exhibition space) and reading the Triangulation stations the visitor is left a bit bereft. Is there still hope? One feels like at the end of George Orwell’s 1984 – the main character is broken and Big Brother’s reign unchallenged. This is where the White Room comes in. Here the visitors can be active. The Tactical Technology Collective provides a workshop programme where one can learn about how to secure one’s digital devices, how to avoid being tracked – on the web or by smartphone, what the alternatives are to corporate data collectors like Facebook or Google.

In the end the nature of internet is twofold and conflicting: on the one hand it allows for unprecedented observation and monitoring, on the other it is a tool for resistance connecting people who were separated by space and time. It is not yet clear if this is enough or if (like the radio and other technological media before) it will be co-opted by the one’s in power.

This leads me to one problem of an otherwise very necessary and inspiring show: For all its social justice impetus that narrative that is presented here is very androcentric – there are few if any feminist, queer or post-colonial perspectives in the exhibition. If they are presented then from the outside. This is not a theoretical objection as women, people of colour and other minorities (who are actually majorities) are especially vulnerable to the kind of hegemonic enclosures on the basis of data and algorithms. In a talk in the supporting programme the feminist philosopher Ewa Majewska gave some pointers towards a feminist critique of quantification: the policing of women’s reproductive abilities, affective labour or privacy as a political tool. More of this in the exhibition itself would have gone a long way.