One of my older brothers played a stand-up bass, and unlike my brother I had no formal musical training. The musical notation that my brother could read and the instrument itself were part of a closed, mysterious and privileged society from which I was excluded. But still, I loved to flail away on the thing.

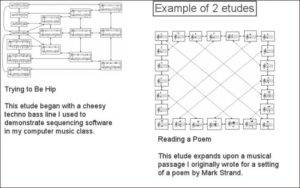

The Piano Etudes project by Jason Freeman, with Akito Van Troyer and Jenny Lin, is a move towards opening the forbidden city of musical composition. The project is based on piano etudes, musical compositions in which the pianist can rearrange connections between some open form pieces. Site visitors are invited to create their own etudes from four short compositions by Jason Freeman. Each etude is transcribed graphically into something that resembles an organizational chart. Each visual component of the chart has a corresponding audio note pattern. The pitch of a note pattern is roughly indicated by the height of a horizontal bar that is part of the graphic. A site user can select graphic elements and arrange them on a time-line to hear the resulting sound piece. Pieces created on the site can be saved and transcribed into musical notation so that pianists can perform pieces created by site visitors.

The Piano Etudes site interface is easy to use. Making the connection between what is possible musically on the site and the visual interface takes a bit of play. But then playing seems to be very much the point of the Piano Etudes project.

Two things that strike me straight off about using visual graphic elements to compose music digitally are remix and re-mediation. The Piano Etudes project invites us to remix the works, to make a new composition from components of the original. Ironically the tradition of open-form musical scores continues in digital mash-ups and other forms of remixing.

Remixing is an admission that all creative product is indebted to other works in some way, and unlike most of the remixing done in the Wild West of popular digital music, in the Piano Etudes site the remixing is done with the authors’ assent and encouragement.

The Piano Etudes project also asks users/composers to re-mediate, to re-write one text in another, completely different medium. Here the musical score becomes visual elements that can be arranged within a rectangular space. The visual mode of composing opens the creative process to those untrained in reading musical scores. That the product – the composition – can then be re-mediated again as musical script, and again re-mediated when performed by a pianist is an amazing expression of digital technology making a creative space.

There are similar spaces for digital composing that do not require formal musical training, the most recognizable being the GarageBand application. The YouTube Symphony Orchestra was competitively constituted by applications/auditions submitted via YouTube. The Pete-Townsend affiliated site and application Method Music (now defunct) came close to offering the kind of creative space for composing music digitally that Piano Etudes makes available. Along the lines of GarageBand and Method music, many of the “opportunities” to create music on the Web are commercial pitches to purchase licensed applications. The free and collaborative nature of the Piano Etudes seems to be quite different.

What makes this project truly wonderful and distinct from other approaches to creating music digitally is that this is a shared creative space. The inherently social nature of the web allows for creative collaboration that dissolves many of the obstacles to creative practices: differences in education, training, language, location, culture and economic status become valuable distinctions among contributors that inform the creative process rather than impede it.

My brother’s stand-up bass offered an opportunity to create something musically, it was a solitary experience, since my playing was dependent on my brother being away from our house. And the product of my flailing away on the bass could be thought of as illegitimate, since I lacked training in music. The Piano Etudes project I feel, values the creative possibilities in us for musical expression. The site also validates those musical expressions by making them available and performative. What is perhaps most valued by the Project Etudes project is play; to discover, to learn and to create through experiences that are enjoyable and interesting – kind of like banging on my brother’s bass fiddle but much more fun, more social and more generative.

——————————–

Special thanks to Turbulence for hosting this web site and including it in their spotlight series and to the American Composers Forum’s Encore Program for supporting several live performances of this work. I developed the web site in collaboration with Akito Van Troyer. Piano Etudes is dedicated to my wife, Leah Epstein. Jason Freeman.

The collaboratively produced on-line encyclopaedia Wikipedia is becoming an important reference resource for art as well as for its traditional strengths in the sciences and popular culture. To help improve the representation of new media art on Wikipedia, more people who are involved in the field should learn about how Wikipedia works and get involved with editing it. This article is a brief introduction to doing so.

Wikipedia’s organization and culture can present a steep learning curve for even experienced new media art practitioners. Don’t be put off, it’s easy to learn how to work with Wikipedia’s organization once you understand the project’s core concepts and the rationales behind its processes.

Becoming a Wikipedia Editor

The technical side of editing Wikipedia is relatively simple, especially if you have experience of writing for other media or of HTML or BBCode editing. To become a Wikipedia editor just register, log in, set up your user profile and start working on a page. As soon as you click “save”, your work will go live on Wikipedia.

The social side of editing Wikipedia can be much more complex, even if you have experience of writing or editing for academia or the art world. Wikipedia is a large project with well established governance structures and its own peculiar terminology. It is important to learn how Wikipedia works at an organizational and social level as well as a technical level in order to write effectively for it.

There are several well written books on Wikipedia that cover all of the various aspects of editing Wikipedia clearly and in depth. Two that are available freely online are –

You can save immeasurable time and frustration by reading at least one of these before you join in editing Wikipedia. I also recommend practicing editing on articles that are unrelated to new media art to start with so you can get a feel for the editing process as an end in itself.

Wikipedia’s organization and processes have their own concepts and terminology (or jargon). The books linked to above should teach you the terminology and concepts you need to know, but if you encounter an phrase in an article or in a discussion you can always find a reference for it on Wikipedia itself.

Notability

The most important concept in editing Wikipedia is “notability“. Notability is Wikipedia’s standard for deciding which topics should be included in an online encyclopaedia. It’s best if you think of it as a strange new quantitative concept that shares only its name with any qualitative concept of notability.

You cannot establish notability in Wikipedia based on personal opinion or unsupported assertion. This would be considered “original research” in Wikipedia’s terminology and rejected. Instead you must establish the notability of your subject by citing multiple reliable third party sources that have in turn found the subject notable enough to comment on.

“Reliable sources” mean established and probably mainstream news or opinion sources such as magazines, journals, or major web sites. “Third party” means not self-published (and not autobiographies).

An additional difficulty when trying to establish notability for any artistic subject, never mind a new media art subject, is that there are no stated notability guidelines for art as there are for music. There should be.

If existing media, books, journals, magazines or the mainstream press cannot provide citations to support the notability of a subject, then it is not notable under Wikipedia’s definition of notability. The solution to this is lies outside of Wikipedia. You will need to write about your subject for reliable sources or to push for other people to do so. This will be of benefit to your subject more generally than just for Wikipedia if they do not already have such coverage.

Conflicts Of Interest

When a subject is suitable for inclusion in Wikipedia, it is important to avoid conflicts of interest. If you are tempted to write or edit an article about yourself or a project or organization you are directly involved with, there is a very simple rule to follow: don’t. This would be a conflict of interests. You can request that such an article be written, and you can contribute links to appropriate sources on its talk page, but you can’t edit it yourself.

Prohibiting conflicts of interest avoids vanity pages, and it avoids censorship. Individuals and corporations can both be tempted to remove negative facts and add positive spin to their Wikipedia articles. As an encyclopaedia, Wikipedia is intended to present a full and balanced view of its subjects. If you have information that you feel could help establish that a subject should be included in Wikipedia, you may be able to contact the editors and provide it, but it must satisfy Wikipedia’s standard for reliable sources (autobiography doesn’t, for example).

What Wikipedia Is Not

As a website Wikipedia can contain far more articles than a traditional printed encyclopaedia, but all of those articles should be encyclopaedic in nature. This means that original criticism, promotional material, reportage and other perfectly valid forms of writing about art have no place in Wikipedia.

As well as such writing not fitting Wikipedia’s stated purpose, Wikipedia is not the most effective way of distributing it. People who are interested in new media art are far more likely to find an audience and get useful input in more appropriate forums. There are many alternative outlets for writing about art, from web sites such as Furtherfield and mailing lists such as Netbehaviour to hosted blogs and Facebook groups. Using a more focused platform or setting up your own resource can be better for promotional purposes as well.

Deletion Reviews

When other editors think that an article does not meet Wikipedia’s notability criteria, they will list it for a deletion review. A deletion review is not a personal attack on the innermost being of the article’s author or subject, it is an opportunity to improve an article for readers by answering the concerns of Wikipedia’s editors. When you have created or edited a page, watch it for deletion review notices so that you can get involved in the process.

The formula for a successful deletion review is simple. Write a well structured article about a notable subject. Then answer any queries with reference to how the article itself satisfies people’s concerns about how it may not follow Wikipedia’s guidelines. If it does not already answer those concerns, edit the article so that it does. If the article cannot be edited to meet Wikipedia’s standards, then harsh though it may seem it should not be on Wikipedia.

It can be difficult to explain precisely how the subject of articles on new media art projects or organizations should be evaluated. Often other editors will evaluate online artworks or pages for community projects simply as web sites and argue that their low Google pagerank means that they are not notable. This is listed as an argument to avoid in Wikipedia’s own guidelines.

Even the longest running and most widely distributed art computing and new media art journals may be unfamiliar or inaccessible to the majority of Wikipedia editors who will vote on whether to delete an article or not. This can create problems for new media artists and galleries as perfectly valid sources may require explanation during a deletion review.

How To Write A Good Wikipedia Article

The formula for a successful Wikipedia article is surprisingly simple. State what the article’s subject is, state why that subject is notable and support this with links to multiple citations from reliable sources, then place the citations at the bottom.

This makes for an article that is informative for Wikipedia’s readers, that is easier for Wikipedia’s editors to review, and that because of this is more likely to remain on Wikipedia.

If you click on Wkipedia’s “Random Article” link you will see that most articles follow this formula (and that those that don’t have most likely drawn the attention of Wikipedia’s editors).

How To Improve The Representation Of New Media Art On Wikipedia

Establishing standards for notability for art and improving the quality of citations for art are tasks that will require involvement in the organization of Wikipedia as well as in the technical side of the editing of individual articles. Organization around a topic on Wikipedia is done through WikiProjects. There isn’t a New Media Art WikiProject (yet), and the Contemporay Art one is moribund. The Visual Arts Wikiproject is very active, and should probably be the starting point for any new-media-art-related developments –

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:WikiProject_Visual_arts

The best argument for keeping an article on Wikipedia is an article structured to quickly make the case that its subject is notable with multiple citations from reliable sources. With a group dedicated to better provision of reliable sources, more articles about new media art topics will satisfy Wikipedia’s standards and be accepted as part of the online encyclopaedia.

And that, galling as it can be when sitting out a deletion review of an article on your gallery or yourself, is the point of editing Wikipedia. For articles to remain on Wikipedia they must satisfy its standards. Those standards exist to make Wikipedia a worthwhile resource for society. New media art should definitely be a part of that resource. It is artistically and socially notable, and we can work to establish this within Wikipedia’s guidelines.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Franz Thalmair interviews Daphne Dragona.

“Tagging”, “posting”, “sharing”, “commenting”, “rating” and … once again, the other way around: affective and opinion-driven practices of exchange seem to be essential key issues for the everyday behaviour on the so called Social Web. But, what happens with us, the users of commercially hosted platforms, when we share our experiences and comment on opinions and statements brought in by other users? Do those mechanisms of interaction have any effect on the clever systems of pre-defined templates we move in? Tag ties and affective spies is the title of an online-exhibition which presents a selection of Internet-based artworks that highlight different aspects of the Social Web. With the exhibition, hosted by the National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens (EMST), curator of the show Daphne Dragona asks if we are really connecting or if we are also forming the structure of the Social Web itself?

The linked artworks reflect some of the controversies brought up by the inflationary use of Facebook, YouTube, Flickr and Delicious, just to name a few of the most popular examples of Web 2.0: We Feel Fine (2006) by Jonathan Harris and Sep Kamvar, for example, refers to the Social Web’s most basic human and affective character, its influence on our everyday lives and the inability of the users to transcend mental and physical borders, as do Gregory Chatonsky’s L’Attente – The Waiting (2007) and Folded-In (2008) by Personal Cinema & The Erasers. Wayne Clements’ IOUs (2008) tests the possibilities of forming content, whereas Internet Delivers People (2008) by Ramsay Stirling visualises the fact that a user still remains a victim of the companies, offering now his subjectivity as a product. Furthermore, the presented artworks point out how Social Media themselves can record and reflect the current trends of the users employing their own contributions (A Tag’s Life (2008), by George Holsheimer, et al) and how they can construct fake realities (The Big Plot (2008/2009), by Paolo Cirio). With a sense of humour, Christophe Bruno refers to the redemption of language by the internet companies in Dadameter (2008) and finally Jodi (Delicious – Winning Information, 2008) and Les Liens Invisibles (Subvertr, 2007) encourage users to escape the conventions and the formalisms the Social Net cleverly imposes.

Who is wearing ties? Who are the spies?

The title of the exhibition, Tag ties and affective spies, is referring to us, the users of the social media and to our current modes of connecting and socialising. I think tagging is one of the most interesting features of the social web. Have we entered the “I tag therefore I am” period? Maybe, as tagging seems to imply a number of issues for the social web. It refers to our subjectivity as it is a process of naming, defining, highlighting our uploaded material. Our choices and order of tags, our taxonomies known as folksonomies, create interrelations and interactions for the users on today’s web. Tags are about associating content, and therefore about sharing, linking with others. They are about attracting attention, connecting and building relationships. Tags are about us and the others.

Spying is a fundamental issue in this relationship and it is basically a form of surveillance based on affection. As we are given so many opportunities to express our feelings in the social platforms today, as we are exposing ourselves constantly with our own will, surveillance is becoming a unconscious habit. Exposure justifies it all. In this complex environment that there could be no better instance for the market to observe, to evaluate and to take advantage of the data offered in order to cover our “needs” and encourage the continuous growth of new ones.

In the exhibition concept you raise the question if users of Social Media sites are really connecting or if they are also forming the structure of those sites. What is the difference between the two activities?

This is one of the main contradictions the social web presents. What are we being promised by all these platforms? That we can be creative, that we can be ourselves and that we can connect with others. While great possibilities might be opening up with the social web, at the same time we are asked to play double roles; to be spectators but also actors; to be consumers but also producers. There is no social web without us. There is no content and no structure without our participation. We are no longer in the web era of the 90s when pages were static and we were discussing authorship and access. Now in the user generated period, the web in constantly being formed by us, by our images, our videos, our posts, our tags, our networks, our tastes, our friends, our own voluntary input. It is very interesting to see how the political notions of immaterial labour and affective labour, as defined by Lazzarato and Hardt respectively have found their expression in the social web. Leisure and work have become one today because it is our own will, interest and affection that are being invested to support the social platforms. We are all cultural workers in the internet.

Many of the presented artworks do have a playful approach to Social Media. Is this characteristic for nowadays use of Social Media in general, or is it the artistic point of view?

I find that play has a central role in the social media. Not only because most of our activities within them have a playful side – lets think about the ways of interacting, of playing roles and of competing in the social platforms. But also because we have the tendency to play, to cheat, to doubt, to transcend the norms and the rules that the social media impose.

The works presented are playful in this sense. They examine the features of the social media, in order to decode them and reverse them; I see their processes as playful tactics that succeed in revealing their mechanisms and functioning. They somehow remind us of our right to disobey that we often forget. So, this aspect refers to us all – no it is not an artistic point of view exclusively. Irony and humour merged with play are introduced to form a critique that can be exercised by any user.

Folded-In, one of the projects presented in the show, is a multiuser online game by Personal Cinema & The Erasers where content as well as form are generated from YouTube and related to the topic of war. Why do you think it is important for Internet-based art to reflect the mechanisms of the medium it is settled in?

This is an issue that reminds us of the net art of the 90s and of other forms of media art – game art mods is another characteristic example- where creators are using the platforms so as to critisize them. Such an approach presupposes a good knowledge from the side of the creators. They need to be participants, residents, players in the social web in order to comment on it, to transform it, to reveal it. So my answer to your question is positive but principally for one reason; for the audience. Who do we – or most accurately the creators- want to address this to?

The main audience would probably be the users of the social media, the people who use them as a tool of communication, of socialisation, as a mode of entertainment, of information and education. It would be absurd to talk about social media through sculpture or painting – although this also does happen… -. If you want to talk to poeple directly you talk to them in their own language and within their natural environment.

How could the online exhibition be presented in a physical setting? Do you think this would add any value – as well as to the art/artists as for the spectators?

This period the exhibition is presented physically in two venues: at the media lounge of the National Museum of Contemporary Art – Athens, and in the exhibition space of Enter festival in Prague. Yes, I believe it does add value for several reasons that interconnect. Firstly, I believe that through a physical installation, institutions can communicate the information to a wider audience that might not be familiar with net based art. Secondly, acknowledge and support in terms of presentation is very important for an art that is contradictory to institutions by its nature and it is out of the marketing system. Furthermore, such works, as the projects on social media, can raise fruitful discussions about issues of art, society and politics and build bridges between institutions, artists and visitors as they are based on platforms that the people know and use.

The project is settled within an institutional framework: How do you think that a museum like the EMST can come to terms with the artworks the 21st century “networked society” develops when “everything becomes changeable, interconnected and rhizomatic; personified, exposed and exploitable”?

That’s a good bet for the future. Will it work? We shall see. Because in a way we are talking about vertical versus horizontal structures. If one absorbs the other, then their nature will fatally alter. I think changes occur and adaptations happen that bring edges closer together. Museums are not what they were in the past. You can not have a network museum – at least not yet – but museums do work in networks today. They also aim to work as public spaces, as environments open to collaborations and discussions. They are trying to bring more people in and allow them to have roles, to be active spectators. I think that museums are learning from the forms of interaction from the virtual public spaces and are developing environments that respond to today’s needs. Artworks are not the peculiarity we should pay attention to – they are only part of the phenomenon. Museums are changing as society is changing itself in an interconnected world.

What was the latest Social Media site you opened an account at?

Dont ask! It was my blog believe it or not… a month ago… I wanted to start it for a couple of years now and I only recently decided to go ahead…

Do you still use it?

Well yes… but as a site mostly. I’ve uploaded the info I wanted and sometime soon… I hope i ll make it more lively. Blogs need energy… I was always admiring bloggers for the time they were giving into this.

About Daphne Dragona

Daphne Dragona is a media arts curator, based in Athens. Her exhibitions and events the last few years have focused on the notion of play and its merging with art as a form of networking and resistance. She has been a collaborator of Laboral Centro de Arte y Creacion Industrial (Spain) for the international exhibitions “Gameworld” and “Homo Ludens Ludens” and of Fournos Center for Digital Culture (Greece) for the International Art and Technology Festival, Medi@terra. She is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Mass Media & Communication of the University in Athens conducting a research on social media and a member of the Media Arts Collective Personal Cinema.

The 4th Radiator festival. Going Underground – Surveillance and Sousveillance.

“The more perfect civilisation is, the less occasion has it for government, because the more does it regulate its own affairs, and govern itself…”

The Rights of Man by Thomas Paine.

Many readers will remember their fave sci-fi, fantasy and social-political movies, exploring and relating to themes of humanity’s civil liberties threatened by technological means. One movie which springs to mind is Enemy of the State, starring Will Smith as Robert Clayton Dean, released in 1998. The film was about a group of rogue NSA agents who kill a Congressman in a political-related murder, and then try to cover up the murder by destroying evidence and intimidating witnesses. It explored and exploited our worries, fantasies and paranoias around technology being used against us by those who have power within the realms of government agencies. In contrast to such adventurous and playful films with their stylish visions and high-octane, scenarios; we are presently faced with something less imaginative and sadly, more predictable. In the real world, as in ‘real’ digital networks and everyday human environments, the creep of surveillance has entered everyday life.

We have emerged into a complex world, inter-meshed in digital and virtual technologies, harbouring social networks and on-line communities, alongside the ever expansive growth of mobile and portable platforms; facilitating us to share with others our moments of immediacy. The convenience of connecting with others has opened a multitude of doors to a complicated era. We have become part of a larger world which is also shrinking at the same time. We are globalized citizens, united not only through economic work-related directives, but data. Behaviour related products for markets thrive on trying to find out what we are doing and thinking. We are a rich resource, fresh territories for knowledge. Digital data about us, ‘civilians’ is big business. Many individuals and organisations including artists, are cashing in on the rush to make money out of our digital identities and behaviours. Whether it be in the supermarket, with I.D cards, on the Internet or by tracing people’s movements on the streets.

The Radiator Festival and Symposium was curated and organised by Anette Schafer and Miles Chalcraft, co-founders and continual main instigators of Trampoline with support from Matt Davenport. Trampoline has hosted and curated events in both Nottingham and Berlin since 1997. Exploits in the Wireless City is the 4th Radiator festival and symposium to date, which lasted from 13th to 24th January 2009, 10 days of Exhibitions, Events, Screenings, Music, Artists’ Talks and more. This time the main theme was about engaging in an active shared dialogue, around the development of digital networks transforming and effecting people’s everyday lives, whether it be public or private space. “In its critique, Radiator will question the opportunities, future strategies and implementations that artists and communities face when learning to act within these new hybrid city spaces.”

My visit was on a different day from the symposium and even though I usually enjoy a good hearty debate, it felt important not to dilute my experience. Nottingham was given a quality treat outside of its usual, consumer orientated vices in witnessing and being part of this festival. The art was accessible from different venues around the city, the Surface Gallery, Hand and Heart gallery, Broadway Media Centre and also the QUAD in Derby.

For the festival a commission was set up, called Going Underground, inviting artists to submit work about surveillance and Sousveillance. The artists selected, were Glenn Davidson (exponentially), N55 Intelligence Agency (NIA), Folke Kobberling & Martin Kaltwasser, The Office of Community Sousveillance, Christian Nold, as well as the guest artists Stanza, Sebastian Craig and Candice Jacobs.

Before we move straight into exploring some of the work featured as part of the Going Underground commission. I need to lay out some context…

In 2006 a research document called A Report on the Surveillance Society For the Information Commissioner was published. Produced by a group of academics called the Surveillance Studies Network. The report was presented to the 28th International Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners’ Conference in London, hosted by the Information Commissioner’s Office. The publication begins by saying “Conventionally, to speak of surveillance society is to invoke something sinister, smacking of dictators and totalitarianism. We will come to Big Brother in a moment but the surveillance society is better thought of as the outcome of modern organizational practices, businesses, government and the military than as a covert conspiracy. Surveillance may be viewed as progress towards efficient administration, in Max Weber’s view, a benefit for the development of Western capitalism and the modern nation-state.”[1]

To deny that Surveillance is systematically effecting a modern day panopticon[2] for UK citizens, more highlights where their priorities lie. One priority seems to be an unquestioning protocol in support of the needs of a market system over the needs of civilian rights. Such a stance communicates a behaviour which is complicit in promoting a hegemony that lacks compassion or empathy of the very real circumstances of public freedoms being eroded for the sake of corporate economics rather than nurturing human, social contexts. Make no mistake, this is the privatisation of our public spaces, civil liberties are pushed aside as a secondary factor, rather too easily at whatever price.

So, if we cannot rely on our governments and local councils to do the honourable thing and take responsibility in effectively challenging this encroachment on our civil liberties, who can we turn to? Thankfully, there has been much debate around the subject in the media the last few years. Whether the government is able to step outside of its current mind-set, and become less blinkered is another thing. So, there needs to be as many different forms of communication around the issue so others from all walks of life can be included to share a critique from their own perspectives. In this context, regarding the festival we have artists who also happen to be experimenting with activism as part of their dialogue, initiating imaginative forms of expression to enable and facilitate varied processes in, getting their critical thoughts on subjects which matter, out there. “…artists using CCTV are critical of the present level of surveillance, but they’re also interested in establishing a dialogue about what is typically a secretive arrangement”[3]

The Surface Gallery successfully presented a dynamic and varied collection of art on the subject. Stanza’s ‘Stars of CCTV’, hung on the wall were representations of the ‘Big Brother’ generation, re-mediated as history paintings representing a social portrait of England. Displayed in expensive white frames, these works showed ghostly, chilling blurred images “each picture has a narrative, a history of time and place”.

Stanza. Stars of CCTV.

Stanza. Stars of CCTV.

The images depict the last whereabouts of a lawyer, the July bombers, happy slappers beating someone up, people drunk in the street, thefts at gunpoint, sex in car, running someone over, stealing from a shop and trying the stuff on first. Other images include police abuse, child abduction, senseless fighting and terrorists using public transport.”

Stanza. We Dont Want No Education.

Stanza. We Dont Want No Education.

Anonymous faces stare back at the CCTV cameras during their drunk and disorderly activities, like acts of defiance, whilst being snapped, trapped within the visual flicker of the ever spying eyes.

Stanza. The Rise of the Urban Surfe.

Stanza. The Rise of the Urban Surfe.

As soon as they are captured for us to observe, they become shadowy reflections of our own selves. Feral representations of strange creatures in an urban zoo. The darkness of these collected images allow us to observe our own subterranean fears, resting closely at the edge of what we as a supposedly decent society, accepts as normality. Yet there is a contradiction at play informing us that this is all too normal, part of the everyday. We are those people within these selected frames, as we scrutinize them, we judge ourselves.

One group who got their teeth stuck into the complex mess of community security and surveillance were The Office of Community Sousveillance, with the project PCSO Watch (Police Community Support Officer).

Upon entering the venue, just before stepping into the main gallery was a help desk for the visiting public to use, offering a kind of alternative community service, where visitors input information regarding their own personal experiences of being watched or hassled by local authority security. On the desk it read “PCSO Watch will be appointing its very own ‘sousveillance officers’ to co-ordinate an information gathering exercise in the period leading up to the festival. The findings of this serious-piece-of-research-completely-unmotivated-by-revenge will be made public and interactive during the festival and will be presented in collaboration with guest undercover officers operating from a mobile field unit placed temporarily in hotspots around the city.”

There is even a blog where you can observe or contribute to the continuing number of incidences, experiences with ‘official’ security in the Nottingham area. This art, transcends the formal realms of being objects or items of installation within an art context alone, and seeks not to be fashioned within what it sees as a limitation. It exploits the ‘imaginative’ frameworks and infrastructures of art culture itself as a creative and polemic space, considering our every day lives and relationships with the world as part of its ingredients, as an interface; allowing a certain amount of flexibility and freedom to express their own particular methodologies and political voice. It rests on the edge of what many would consider to be art and this is where its main strength lies, for it if became ‘gallery’ art, the messages and spirit of it would be lost. For it to remain in its essence vital, it needs its own agency of raw presence. This work is angry, it demands an immediacy which is direct and resolutely challenges institutional hegemony, harbouring an angst which was not uncommon with the early nineteenth century Luddites. It is art performance and direct action.

Officer B report of incident

Incident report (ref 230)

15.15-15.45 Thursday 15 January 2008

LOCATION – PCSO WATCH mobile unit parked legally (with landowners permission) on private land at the edge of Sneinton Market. Officer B was staffing the mobile unit.

LOCATION – PCSO WATCH mobile unit parked legally (with landowners permission) on private land at the edge of Sneinton Market. Officer B was staffing the mobile unit.

This work rests between legality and illegality. By posing as security officers, PCSO Watch imaginatively play at the borders of what is typically deemed right and wrong, real and unreal, pushing their expression in the form of political enactments and direct action. This is a paradigm shift that is not particularly interested in the art critic’s perspective. Their approach deliberately bypasses art dialogue and is more interested in connecting with every day people’s lives. The audience they wish to make contact with is all of us. By relocating their particular creative practice and placing it in the streets, it opens up a more cultural dynamic. Tapping immediately into the murky depths of what our society is dealing with locally, nationally and in fundamental ways – it is about reality. At the same time this work helps us to realise that outside, out there, we need more than just shops as social environments; that we need more creative and wholesome experiences in our cities coming from the ground up. Through their work, one is also aware of how vulnerable we all are to forces imposed by those who say that they care for us. Solutions to social problems need not always have to be based around monetarily orientated processes and a presumption that all civilians are potential villians, tarred with the same brush.

The energy and spirit of this work reminds me of the The Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army “…we refuse the spectacle of celebrity and we are everyone. Because without real names, faces or noses, we show that our words, dreams, and desires are more important than our biographies. Because we reject the society of surveillance that watches, controls, spies upon, records and checks our every move. Because by hiding our identity we recover the power of our acts. Because with greasepaint we give resistance a funny face and become visible once again…”

Another artwork worth highlighting is Blind Spot by Folke Kobberling & Martin Kaltwasser. I remember a day project/event that they collaborated on with Heath Bunting in Warsaw, 2008 called Fence Challenge. A one day performance of Kobberling & Kaltwasser and Bunting, an ironic play with architectural borders which get higher and steeper as a kind of obstacle run. Building fences and gates of found materials for Heath Bunting to climb over.

This time round they built small temporary structures out of building waste, with panels of wood and doors in Nottingham. These structures were designed and made to fill in spaces, blind spots where the gazes of CCTV cameras did not reach. When I saw these pieces they were exhibited in the gallery itself, but even imagining them in the streets brings a smile to one’s face.

These mini- architectural builds were human scale, you could go inside and close the door behind you. Offering a haven to those who wished to avoid the perpetual gaze of cameras, to hide away for a little while when in the street, in order to reclaim some sense of privacy.

A contemporary enactment of the Orwellian vision is now here and for real, millions of lensed spectres watch our every move around the country in the streets, as the constant drone of shopping serfs waddle around in their state imposed panopticon daze. In George Orwell’s visionary novel Nineteen Eighty-Four the Thought police could view and control citizens at any moment via a tele-screen, no one knew whether they were being watched or not. Today, the UK Government is so rabid in its support of a more technocratic solutions to control its citizens, we are now the most watched soap opera by the powers that be on the planet. Us, who live in Britain are presently monitored by 4 million CCTV cameras, and if you happen to be living in London you are probably viewed on camera about 300 times a day.

A simple, search on the Internet for CCTV cameras will take you to thousands of web sites, offering you up to the minute, hi-tech CCTV equipment for the viewing of people in offices, work environments as well as the more lucrative business of selling CCTV for street surveillance. If we take a moment and consider the financial crisis, the repeating wars and climate change. It should not be a surprise to anyone that art in its various mediums and forms will naturally take account of it all and question what this means. Yet much art, whether it be performance based, activist or media art related are pushing things further in their processes, much of it challenging the very infrastructures of our institutions and their purposes for existence. This is not because they wish for a revolution, but more because they demand a better life for all, asking our institutions to become more human regarding their interaction with civilians and offer more progressive approaches. Our society needs an upgrade, pretty quick!

There were many other works at the festival worth writing about but this article would have been even longer, so I hope this will do for now. My main aim was to pull together the issues proposed by the festival commission Going Underground and discuss some of the artworks exhibited.

Regarding the Going Underground commission itself? It was successful, a much needed project and festival that desperately needed to happen. It has contributed to the larger debate on surveillance. Instead of choosing to treat art like a conveyor belt as a singular and banal process. Trampoline took a risk and moved things on further and this is to be commended. Hopefully, this endeavour will leave a legacy in Nottingham with some thought provoking challenges for all to reflect upon.

References:

[1]’A Report on the Surveillance Society For the Information Commissioner by the Surveillance Studies Network.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/02_11_06_surveillance.pdf

[2]The Panopticon is a type of prison building designed by English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in 1785. The concept of the design is to allow an observer to observe (-opticon) all (pan-) prisoners without the prisoners being able to tell whether they are being watched, thereby conveying what one architect has called the “sentiment of an invisible omniscience.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panopticon

[3]Keep an eye on our growing surveillance culture

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2009/feb/09/surveillance-privacy

Other links of interest:

Talking CCTV Launch.

http://www.nottinghamcdp.com/index.asp?pageid=pageid183.xml

Watching the Watchers.

Right under Big Brother’s nose, artist-hackers are using surveillance images for their own purposes.

Christopher Werth. NEWSWEEK From the magazine issue dated Sep 8, 2008.

http://www.newsweek.com/id/156339/output/print

Notes on Surveillance, Sousveillance and Inverse surveillance:

Sousveillance, originally a term French, as well as inverse surveillance are terms coined by Steve Mann – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steve_Mann (Toronto, Canada) to describe the recording of an activity from the perspective of a participant. “Surveillance” denotes the act of watching from above, whereas “sousveillance” denotes bringing the practice of observation down to human level (ordinary people doing the watching, rather than higher authorities or architectures doing the watching).

Inverse surveillance is a proper subset of sousveillance with a particular emphasis on “watchful vigilance from underneath” and a form of surveillance inquiry or legal protection involving the recording, monitoring, study, or analysis of surveillance systems, proponents of surveillance, and possibly also recordings of authority figures and their actions. Inverse surveillance is typically an activity undertaken by those who are generally the subject of surveillance, and may thus be thought of as a form of ethnography or ethnomethodology study (i.e. an analysis of the surveilled from the perspective of a participant in a society under surveillance). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sousveillance

“There is something liberating about robots created just to enjoy themselves.”

“Neurotic” was a performance by Fiddian Warman featuring three robots and a number of Punk bands over three nights at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art. Warman and the bands performed for the robots which shared the dance floor with the audience. Powered by hydraulic pistons whose motions simulate Punks’ deliberately artless pogo dancing, the robots activated when the neural net system running on the computer-controlled them decided that a band sounded Punk enough to dance to.

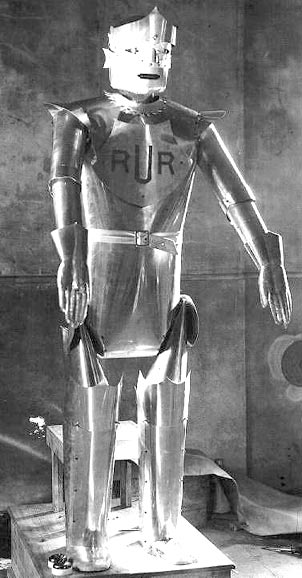

The word “Robot” comes from Karel Čapek’s 1921 play “Rossum’s Universal Robots”. As the artificial workers of the title become increasingly human, the human characters become increasingly mechanical in their words and actions. Jay David Bolter’s 1984 study of how technology informs humanity’s conception of itself, “Turing’s Man”, provides a historical context for this idea; the conception of human beings as computers replaces earlier ideas of clockwork and fire as the “enabling metaphor” of civilization.

Rossum’s Universal Robots – Karel Capek (1890-1938).

Rossum’s Universal Robots – Karel Capek (1890-1938).

The inversion of the roles and characteristics of master and servant from Čapek’s play is reflected in a contemporary technological culture where computer games such as Guitar Hero allow computers to demand that human beings perform effectively with robotic precision through simplified simulations of musical instruments. This is a logical progression from earlier games where computers instructed human subjects to dance with mechanical timing. Such games are enjoyable and have the performance-enhancing effect that is often part of the enjoyment of computer games. But they make a Tamaogitchi-style reversal of the presumed relationship of human master to computer servant.

Dancing Punk robots might replace human players in such a game. But they would have to have some inner life in order to simulate what a human being experiences when playing the game rather than just mechanically performing the game’s tasks. Or alternatively, they might turn any live bands that they dance to (or not) into performers in such a game, making a presumably authentic social experience into a game of matching their performance to a computerised idea of what ideal performance is.

Robots, music and audience interaction have a history. The robots in the 1983 video for Herbie Hancock’s “Rockit” were built by Jim Whiting using pneumatic systems controlled by a ZX spectrum with a parallel I/O board. They were not music-responsive and acted out pre-set animations encoded into the controlling computer’s program. Edward Ihnatowicz’s “Senster” of 1970 was sound-responsive but used ultrasonic range-finders rather than music to react to its audience.

Herbie Hancock – Rockit.

Herbie Hancock – Rockit.

Beyond science fiction, robots are functional replacements for human beings rather than entities with any kind of inner being or experiential self. They may look very different to a human being and perform a task very differently. Robot arms assembling cars could not be mistaken for human welders. But what happens when robots are built to replace human experience rather than human activity?

Philosophical debates aside, human experience is processed and stored in the brain. The most direct way of physically simulating a human brain is to simulate the neurons that make it up. Such a system is known as a neural net.

Neural nets were developed in the 1950s, implemented first in hardware and later in software. They appeared in popular culture by the early 1960s with a television news report on a neural net that could correctly identify the gender of faces in photographs. It could even tell that The Beatles’ long-haired pop music stars were male (no mean feat in an England that was only just beginning to swing).

A neural net is a simulation of a simple system of biological neurons, simpler than the brain of an earthworm, that is “trained” on certain inputs to give certain outputs. In the case of Neurotic, the input was Fiddian Warman’s Punk record collection, and the output was the command to the robot’s hydraulics that makes them pogo.

The problem with neural nets compared to more rule-based Artificial Intelligence approaches like expert systems is that they are effectively a set of meaningless numbers. We cannot know how the nets have learnt what they have learnt. Or even if they have learnt what we think they have learnt, as the Cold War anecdote about a neural net that learnt how to spot forests on sunny or cloudy days rather than with or without Soviet tanks illustrates. If they are trained for a task, they need testing to ensure they function well.

The best-known general test for artificial intelligence is a performance measure in a constrained social setting. Alan Turing’s “Turing Test” uses a human judge to compare two subjects hidden in a different room and communicate through a teletype (today, we would use a chat or instant messaging program). One subject is human, and the other an artificial intelligence. If the judge cannot tell which is the human and which is the AI, the AI is declared to have passed the test.

The Turing test is an evaluation of functional performance. It tests for intelligence, not emotion. But where the function a robot performs is an effective one, an emotional one, such as dancing to Punk music, the careful separation of inner life and outer effect that the Turing test creates breaks down. Emotional performance is a matter of behaving in an emotionally authentic manner.

Punk is the epitome of authenticity in contemporary Western culture. Actual Punk was a youth culture of the latter half of the 1970s born of social and economic discontent and a do-it-yourself ethos. To this day, the mass media seem to believe that adding Punk to something makes it seem edgy and vital, whether science fiction (Cyberpunk, Steampunk) or manufactured pop music (Green Day, Pink).

Contemporary Punk is a strange beast. Thirty years after Punk’s youthful historical moment, it must be inauthentic, but a good live Punk band has an energy that mass-produced corporate indie lacks. Those of you who remember Punk will have opinions on which bands were for real and which weren’t. Despite attempts to reduce Punk to a saleable canon, for many people, real Punk wasn’t The Sex Pistols. The history of Punk is necessarily untidy, incomplete and personal to those who lived it.

This sense of style is an aesthetic of what was and wasn’t really Punk. The aesthetic of the robots’ neural net is Fiddian Warman, derived from his collection of Punk records. The robots are being tested as embodiments of Warman’s Punk sensibilities. Or perhaps the bands are.

Neurotic robot. Institute of Contemporary Arts in London (3-5 July 2008). Fiddian Warman.

Neurotic robot. Institute of Contemporary Arts in London (3-5 July 2008). Fiddian Warman.

For “Neurotic”, the Punk bands, three per night, performed on a stage. Behind them was a projection of a visual representation of the sound and the neural net’s responses to it projected on the wall behind the band. The representation was a pixelated grid of greys representing sound frequencies, each row a slice of sound that scrolled past over a label that told the audience whether the net thought the sound was “Punk” or “not Punk”.

In front of the stage at the front of the dance floor, the robots mixed with the audience. Health and safety concerns aren’t very Punk, but the “bodies” of the robots lifted the hydraulic rams out of harm’s way, which was just as well when some of the audience started slam dancing around them.

A nightclub is a constrained social setting, with the roles of performer and audience well defined and communication between audience members limited to what you can hear above the bass and see through the strobes. When you put affective robots into this scenario, it becomes a kind of Turing Test, but I’m not sure who for. The audience was evaluating the robots. The robots were evaluating the Punks, and the Punks had their eye on both.

Mr Andrew Tweedie and the PVCs

Mr Andrew Tweedie and the PVCs

The bands played competently, working the crowd and conjuring the energy of Punk into the project space of a twenty-first-century art gallery just out of spitting distance of Buckingham Palace. When the robots judged a band insufficient to pogo to, the band seemed genuinely offended and worked harder to get their attention.

Watching the projection of the robots’ neural network visualisation, I couldn’t see what exactly in the sound input caused the robots to pogo. Once or twice, I thought I’d worked it out, only to be confounded by what the robots did next. The neural net is the robot’s aesthetic and the self (however simple). If I could have found a pattern to how they reacted, then the network would lack internal complexity, so from the point of view of the robots having a simple analogue to an inner life, it is better that I could not work out the relationship. It is not always true that to explain something is to explain it away, but in this case, to explain it too simply would have reduced it. The knowledge that a process that I could not follow was nonetheless reacting in a coherent way was familiar from dealing with living things.

The robots’ lack of self-awareness about their state and actions makes their experience and expression of that experience authentic. They do not know that Punk’s historical moment has passed. They know that they are hearing music they like and that there’s only one thing you do when you hear it. When robots are so often treated effectively as slaves, and now sometimes as masters, there is something liberating about robots created to enjoy themselves.

The robots pogo-ing.

The robots pogo-ing.

Robots and neural nets might seem to belong to the Cold War rather than the era of Web 2.0, but as computer games and military robotics show, both are still current technologies. And it is the Web 2.0 strategy of using technology to capture and create social behaviour that is at the heart of “Neurotic”.

The robots are designed to perform as participants in a social event. They are designed to participate in and be part of a spectacle. They are not in themselves the spectacle or passive spectators. They are part of a series of feedback loops and social interactions, inserted into and intensifying the relationship between performers and the audience. They do so very successfully.

At one point during the gig, I spotted the stage door open and made my way through the crowd to take a look backstage. Through the strobes, I saw movement out of the corner of my eye and turned to see jumping figures in front of the stage. “People in the mosh pit”, my subconscious assured me before I realized that it was the robots. Had they passed the Turing Test, or had I failed it?

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Welcome to the June 08 issue Furthernoise.org where we are pleased to announce the launch of our new net release compilation Explorations in Sound, Vol 3. Music of Sound.

For some, a spiritual experience is sending thoughts and feelings, prayers and even curses into the ether, hoping to receive a response or reply or perceiving some effect. However, what is received due to that projection can be difficult to assess and measure.

The project Meditation for Avatars enlists personal computers to make such spiritual projections. Participants in this project donate processing time on personal computers; the computers process mantras and send them through the Internet. A mantra is a repeated chanted sound that is used to focus one’s concentration during meditation. Personal computers are used because if there is one thing computers are good at, it’s undeviating repetition.

The goal of the project, which the creators describe as an “artistic experiment”, is to raise the spiritual consciousness of those donating processor time… “they [computers] meditate to raise our consciousness” proclaims the website. Participants can select which mantra is to be processed and see, on a screen wallpaper, the current mantra is “chanted” by the computer. According to the project developers, computers in this experiment become charged with positive energy, and this energy can be passed on to the users of the computers. By watching their computer “meditate”, participants will be encouraged to practice their own meditation.

![]()

Mantra Screen shot.

Like other forms of meditation or prayer, the consequences of devoted computing are best perceived through a filter of faith. “In order to be able to receive this energy, we need trust and faith in the positive” the website proclaims. This reviewer must lack such faith because I am compelled to wonder about assessment: how can anyone know if this works? But then, having faith eliminates the need to measure this experiment’s result. Still, many forays into the spiritual are done to realise some change on the earthly plain. The change that Meditation for Avatars seeks is “… in terms of our experiment, the greater the number of computers online, the more powerful the energy within the network. This energy can positively influence everything connected with it – the individual computers, the community network, and the Internet”. The spiritual energy in this experiment is meant to influence another non-substantial artefact – the Internet positively.

![]()

The parallel this project draws between the Internet and spirituality I find intriguing. Like many perceptions of what a spiritual realm would be like, the Internet is not wholly concrete. It has a real impact on human affairs but in ways that are not easy to gauge. As spaces, the Internet and spiritual realms both provide private and communal experiences; cyberspace is immaterial, but like a spiritual realm, it is accessed through material practices.

When we open our browser, we project ourselves into a non-corporeal space and the responses to our projections are sometimes hard to fathom. Indeed, the Internet can be downright ethereal at times. For example, those cryptic emails from an unknown source, like voices from beyond, give us the power to enlarge our body parts. Or those invitations to friends on Facebook that remain mysteriously unconfirmed; how like an unanswered prayer an unfulfilled Internet communication can be. Google acts as a Delphic oracle, an intermediary between the elusive spiritual and the actual. When we consult the Google oracle, 30,500,000 responses to the search prompt “why doesn’t anyone love me?” become available. Google performs as oracles have always done – Google will lead us to directions on how to make toast but can’t make clear the really big issues. I wonder what a Google search for “the benefits of positive spiritual energy in my computer” would turn up.

Meditation for Avatars draws a line connecting spirituality and the Internet and I ask the project to connect the material practice of computer processors chanting mantras and some measurable impact on the human condition. But perhaps the concept of the Internet as a spiritual space is where I can resolve my difficulty with the Meditation for Avatars project. If computers, as avatars, chant our behalf, perhaps the performance of our other avatars on the Internet has real consequences. Maybe the mayhem that is perpetrated in World of Warcraft corresponds to violence and intolerance in real life. Maybe Second Life is really a Second Chance, and instead of accumulating stuff and gratifying appetites, digital space is where avatars can perform differently, more nobly, than we do in Real Life.

But let’s admit it – like Real Life, our projections into cyberspace can be far from noble. The list of egregious digital ugliness people bring to the Internet is long. The violence and corruption of Real Life is mirrored in hacks and assaults on sites and in pernicious child pornography: victims of cyber crimes experience feelings of violation and helplessness that mimic the feelings of those subjected to Real Life crimes of violence. A counterbalance to the uglier side of the Internet might be the tasks we assign our computers. The steadfast churning out of mantras may work to detoxify our systems and us. And while the processors drone on, the Meditation for Avatars wallpaper provides a tally of our computer’s (and therefore our) contribution to the good, a measure of gentle sanity in the cyber-world.

As a project, Meditation for Avatars asks us to consider the ramifications of our projections into digital space to imagine that the time and energy to which we devote our computers affect users and the network community. This is another way of asking us to be responsible for what we do with the Internet. The Internet is ultimately a communal space: we need to care about how we treat each other in that space. If, in an experiment to raise spiritual consciousness, our awareness of others is heightened, then Meditation for Avatars might be on to something.

A review of THE THIRD MIND at Le Palais de Tokyo

Curated by Ugo Rondinone

THE THIRD MIND

Le Palais de Tokyo

13, avenue du president Wilson 75116 Paris

September 7th – January 8th

I first want to congratulate the guest curator Ugo Rondinone and the new director of Le Palais de Tokyo, Marc-Olivier Wahler, for mounting a really high-quality group show (*) that criss-crosses an assortment of generational frontiers and stylistic barriers. Ugo Rondinone is an artist known for his talent for building systems of connections and given the visual results of this exhibit; he has, in large part, very good taste in art. I particularly enjoyed his assembling excellent works of Brion Gysin – William S. Burroughs, Ronald Bladen, Lee Bontecou, Andy Warhol, Nancy Grossman, Cady Noland, Martin Boyce, Paul Thek and Emma Kunz.

I think what might be interesting about this disquieting show, is to look at how this group show differs in its conjoining (or not) from other group shows by pinning it to the collaborative work of Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs from the early 1960s known as The Third Mind. Also we can place THE THIRD MIND in the context of wider connections and ponder at what point does homage turn into exploitation?

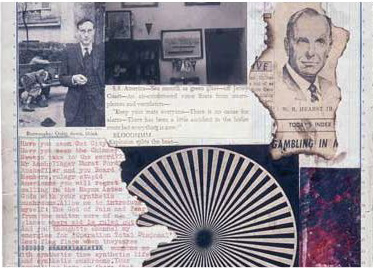

First some background. Beat writer Burroughs and the artist Brion Gysin, known predominantly for his rediscovery of the Dada master Tristan Tzara’s cut-up technique and for co-inventing the flickering Dreamachine device, worked together in the early 1960s on a publishing project that used a chance based cut-up method. A cut-up method consists of cutting up and randomly reassembling various fragments of something to give them a completely new and unexpected meaning. 1+1=3 (**) In the recent biography of Allen Ginsburg, Celebrate Myself, Ginsburg’s archivist, Bill Morgan, excellently recounts some of the genesis of Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs forays into radical Dada cut-up technique and collaboration based on Ginsburg’s diary entries.

Gysin in the mid 1950’s pointed out to Burroughs that collage technique has been a regular tool in painting and graphics since half a century. This came as late news to the young Beat writers of that time, so it is perhaps not surprising that Ginsburg’s first exposure to Burroughs’s use of the cut-up was met with distain – Ginsburg considered it something along the lines of a parlor trick. (p. 318) Even more, Ginsburg speculated from NYC that Burroughs had lost his mind through lack of sex (note: Burroughs lusted after Ginsburg in vain). As a joke, Ginsburg and Peter Orlovsky cut up some of their own poems and rearranged them and sent them to Burroughs with the note ‘Just having a little fun mother’. (pp. 318 – 319). However Burroughs was so dedicated to the random cut-up method that he often defended his use of the technique. When Ginsburg and Orlovsky arrived in Tangiers in 1961, Burroughs was working on an even more advanced use of the cut-up; he and Ian Sommerville were cutting and splicing audiotapes and Burroughs was making collages from newspapers and photographs while proclaiming that poetry and words were dead. (pp.331-332)

Burroughs however soon began work on a cut-up novel, the Soft Machine – drawing material from his The Word Hoard. (**) This manuscript was soon being ‘assembled’ and edited by Ian Sommerville and Michael Portman; Burroughs’s companions. Sommerville was regularly speaking of building electrical cut-up machines.

Burroughs would soon begin collaborating on a book project with Brion Gysin using the cut-up method; cutting up and reassembling various fragments of sentences and images to give them a new and unexpected meaning. The Third Mind is the title of the book they devised together following this method – and they were so overwhelmed by the results that they felt it had been composed by a third person; a third author (mind) made of a synthesis of their two personalities.

Ginsburg remained highly skeptical for some time, but following his travels in India came to appreciate the cut-up technique; even while never employing it.

Now for THE THIRD MIND show itself. Two major works (themselves multitudinal) advance well Rondinone’s thesis of the third mind. Of course, foremost is the Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs collaboration The Third Mind. An entire gallery is devoted to the maquettes for this unpublished book from the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art – and it does not disillusion the 4th mind: that of the viewer/reader. It is a golden hodgepodge

feast and serves as the underpinnings of the exhibit.

Then there is the glamorous video installation/accumulation of Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests from 1964-1966: a group of silent b&w three-minute films in which visitors to the Warhol factory try to sit still. Here we see an interlaced presentation that visually connect the youthful faces of Edi Sedgwick, Susan Sontag, Nico, John Giorno, Jonas Mekas, Gerald Melanga, Jack Smith, Paul Thek, Lou Reed and the distinguished Marcel Duchamp. The presentation is structurally connectivist given its 4 directional presentation as a low laying sculpture. It is incredibly enjoyable. Plus the room is ringed with black haunting photograms called Angels by the fascinating Bruce Conner from 1973-75.

In terms of a more traditional synthetic associational curatorial fission, the strongest effect was achieved for me in the Ronald Bladen, Nancy Grossman, Cady Noland gallery. Everything here is screaming in harmony of power, sex and violence. The entire space felt hard as nails ? most all of it a macho silver and black. Bracketing the huge gallery were long rows of Nancy Grossman’s famous black-leathered heads, aggressively sprouting phallic shapes like picks and horns. Ronald Bladen’s 1969 minimal masterwork The Cathedral Evening aggressively dominates the interior space with a mammoth triangle breach. This is backed up by his famous Three Elements from 1965. Then, giving the gallery a sense of an almost palpably Oedipal contest, is a large group of superb black on silver Cady Noland anthropological silkscreens on metal from the early 1990s.

The other room that really collectively worked for me held Paul Thek and Emma Kunz. Three wonderful Paul Thek Meat Piece are there; weird post-minimal sculptures that sickly encase flayed body sections in wax in long yellow transparent plexiglas shrines that literally shine. This meat-machine mix is counter-pointed with the healing magnetic-field ephemerality of Emma Kunz’s geometric drawings, done with lead and colored pencils or chalk on graph paper. It was easy to envision some fierce spiritual forces zapping each other throughout that area.

Other rooms bring the connectivest bent to a jolting halt. I simply admired Martin Boyce’s huge neon sculpture (Boyce channeling Dan Flavin), but it produced no associative effects with what else was in the room. Worse of all was a room entirely devoted to the work of Joe Brainard. What was that doing there? One strains to see (or imagine) even a 2nd mind in that space. So the unavoidable thought arises, well, Rondinone must like this stuff – so that is at least two minds in synch. But does Rondinone think there is anything still interesting in a Gober sink? His The Split-up Conflicted Sink from 1985 also played a huge flat note for me in this supposed visual symphony, as did the overly unembellished black crosses of Valentin Carron, the stupid car bashed installation by Sarah Lucas, and the cloying faux-naive canvases of Karen Kilimnik. How to connect this boring, stupid and naive work to the third mind connectivity theme?

OK. I will. On thinking about the show on my way home, I concluded that the show’s relationship to connectivity is gravely naive and passe (if pleasant in a quaint, charming way) in lieu of the multi-networked world in which we now reside. By now various theories of complexity have established an undeniable influence within cultural theory by emphasizing open systems and collaborative adaptability. One ponders if Rondinone has ever even heard of the theories of Tiziana Terranova, Eugene Thacker or other cultural workers involved in the issues of human-machine symbiosis as interface within our inter-network media ecology. So yes, part of the pleasure for me was bathing in this old fashioned naivety, having just spent some serious time reading and writing on the topics of conspiratorial shadow activities (****) and viral software logic based on complex inter-connectionism (*****). Placed against issues of avant-garde cybernetics, the coupling of nature and biology via code, media ecologies, distributed management teams, internet mash-up music, artificial life swarms, the political herd mind, and Negri/Hardt’s multitudes; THE THIRD MIND played in my mind like a romp through a kindergarten playpen. Nice. It felt good to forget about that pervasive nagging political/cultural feeling of stalemate created by the resilience of our current reality in that it assimilates everything.

But no, Ugo Rondinone did not randomly cut and reassemble art to create a new third meaning. He did not cut-up anything. He did, like every music dj, fashion designer, and group show curator, remix contemporary expression from recent decades to permit new meanings to emerge from the mix. The ideas in the collaborative work of Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs were not needed to achieve this end – and perhaps they were poorly intellectually served here (even though it was great to see the work). There was no use of chance or randomness evident here (even the re-shuffled catalogue pages I heard was rather suspiciously non-random) that is necessary for a really unexpected – and perhaps disastrous – result. This show did not go that far. There was no randomly reassembling of various fragments of something to give them a completely new and unexpected meaning (like I saw in the show Rolywholyover: A Composition for Museum by John Cage at the Guggenheim Museum in Soho NYC in 1994). THE THIRD MIND is just a standard, but good, heterogeneous art show where the whole is greater than its parts. Which is as it must be.

The show contains work from: Ronald Bladen, Lee Bontecou, Martin, Boyce, Joe Brainard, Valentin Carron, Vija Celmins, Bruce Conner, Verne Dawson, Jay Defeo, Trisha Donnelly, Urs Fischer, Bruno Gironcoli, Robert Gober, Nancy Grossman, Hans Josephsohn, Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs, Toba Khedoori, Karen Kilimnik, Emma Kunz, Andrew Lord, Sarah Lucas, Hugo Markl, Cady Noland, Laurie Parsons, Jean-Frederic Schnyder, Josh Smith, Paul Thek, Andy Warhol, Rebecca Warren, and Sue Williams. Also applause to Marc-Olivier Wahler for cutting Le Palais de Tokyo into large but manageable discrete spaces. What a relief from the prior cavernous chaos.

(**) Recently I heard Martin Scorsese speak about how any editing together of two shots in a film creates a third subjective image effect in the mind of the viewer.

(***) The Word Hoard is a collection of Burroughs’s manuscripts written in Tangier, Paris, and London that all together created the super mother-load manuscript that served as the basis for much of Burroughs’s cut-up writings: The Soft Machine, Nova Express, The Ticket That Exploded, (together referred to as The Nova Trilogy or Nova Epic). Even Naked Lunch was taken from sections of The Word Hoard. There was also produced a text called Dead Fingers Talk in 1963 which contains excerpts from Naked Lunch, The Soft Machine and The Ticket That Exploded – combined together to create a new narrative. Also, via Burroughs’s artistic collaborations with Brion Gysin and Ian Sommerville, the cut-up technique was combined with images, Gysin’s paintings, and sound, via Somerville’s tape recorders. Some of these recordings can be heard here.

There were also a number of cut-up films that were produced which can

be seen here:

http://www.ubu.com/film/burroughs.html

William Buys a Parrot (1963)

Bill and Tony (1972)

Towers Open Fire (1963)

Ghost at n?9 (Paris) (1963-72)

The Cut-Ups (1966)

Twisting Fistfuls of Time with David Rokeby

An Interview with David Rokeby, in conjunction with his first UK retrospective Silicon Remembers Carbon, FACT, Liverpool, (20th April – 10th June), by Charlotte Frost.

2nd part of the interview.

CF: That makes me want to ask whether ‘interactive’ is the right word? I was thinking about how it became a promotional buzz-word, and although undoubtedly you are a pioneer in works which developed unprecedented levels of interactivity, are there other terms that you think – perhaps today at least – better apply? For example I was thinking of proposing ‘integration art’, by way of highlighting the slippage between human and artificial intelligence in your work. Is interactivity still a term that you think works? Or is it even important to have a label for it?

n-cha(n)t

DR: I’ve never found a comfortable label for what I do. I have a very complicated relationship with language which is why I spent so much time doing [url:http://www.rokebyshow.org.uk/names.html]The Giver of Names[/url] and [url:http://www.rokebyshow.org.uk/nChant.html]n-cha(n)t[/url], which were so involved with language. I think my role is usually more to dodge descriptors as much as possible and to survive in a world between descriptors; my job is always to slip between the cracks. If someone tries to define something that’s dear to me too closely then I will probably come up with what I think is something that both fits and doesn’t fit and messes with the existence of the category.

The giver of Names

“Interactive” is useful, it certainly doesn’t apply to all my work, some of my work is very explicitly non-interactive. Some of it that could be interactive is intentionally not because there are times when interaction is not the correct mode of reception, it engages a different part of the viewer, it puts them in a different space and that’s not always the appropriate space for the work. As you noted in the previous question I have sometimes hidden interaction in works because interactivity is sometimes very useful to set-up the relationship with the artwork and the audience and if they don’t know about it then they don’t become self-conscious about it, they don’t spend time thinking about it, and it just does its thing and makes sure the audience has as close an experience with it as possible.

“Integration art” is fine except it only works if you already understand the technology framework, or rather understand that there is a technology framework around the work because integration has a lot of different meanings in a lot of different contexts. In fact one half of the work [url:http://www.rokebyshow.org.uk/watch.html]Watch[/url] is specifically integration art because it uses integration as a mathematical function to compute the image, so there are lots of different layers to that. The term ‘integrated’ is interesting because the new media section of the Canada Council for the Arts in the 1980s was called the “integrated media department”, and it was interesting because in those days new media was such a sprawling thing – sparse and sprawling – and the department ended up receiving the applications which didn’t fit anywhere else.

CF: To pick up on something you were saying on how people interact with the works, I’m wondering about the gallery space and – I know you’ve talked about your works being intimate – how intimate you think an interactive work can be in a gallery? And to what extent the artificial set-up of a gallery codes people’s behaviour, in much the same way as a computer does. It makes me think of the gallery as a Graphic User Interface for art information, can you comment on that?

DR: I like galleries, I’ve also done a fair amount of work in unmarked public space, but I like galleries for works that are designed for galleries. There is a certain space that you have in a gallery that you have almost nowhere else in our culture, which is nice. There is a kind of focus that is possible in a gallery that isn’t very common in our culture. There is a kind of mental shift that happens when you go into a gallery space – it can shut you down, you can feel threatened by it – but I tend to feel like I’m breathing a little more oxygen in the air and that I can pay a different kind of attention. I appreciate that frame around a fair number of my works. On the other hand there also tends to be a fairly small flow of people through galleries most of the time, which means it is possible often to have a fairly intimate experience.