On the 20th of September, Tatiana Bazzichelli and Lieke Ploeger opened the 17th conference of the Disruption Network Lab with CITIZENS OF EVIDENCE to explore the investigative impact of grassroots communities and citizens engaged to expose injustice, corruption, and power asymmetries.

Citizen investigations use publicly available data and sources to autonomously verify facts. More and more often ordinary people and journalists work together to provide a counter-narrative to the deliberate disinformation spread by news outlets of political influence, corporations, and dark money think-tanks. However, journalists and citizens reporting on matters in the public interest are targeted because of the role they play in ensuring an informed society. The work of independent investigation is often delegitimised by public authorities and denigrated in a wave of generalisations against ‘the elites’ and media objectivity, actually designed to undermine independent information and stifle criticism. It appears to be a global process that aims at blurring progressively the boundary between what is fake and what is real, growing to such a level that traditional mainstream media and governments seem incapable of protecting society from a tide of disinformation.

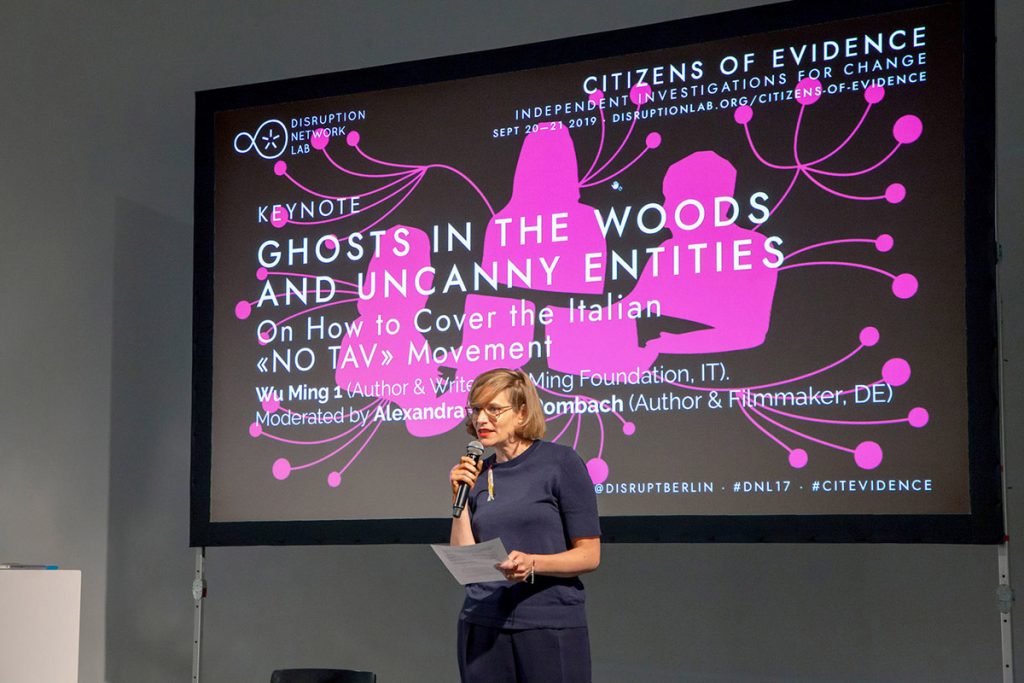

An increasingly Orwellian campaign for the purpose discredit upon them has been built for years against citizens and activists opposing the project of a controversial high-speed rail line for freight trains between Italy and France, which is considered useless and harmful. The Disruption Network Lab conference opened with the keynote GHOSTS IN THE WOODS AND UNCANNY ENTITIES: On How to Cover the Italian «NO TAV» Movement by Wu Ming 1, who spent three years among the people of the Susa Valley opposing this mega-infrastructural project.

As the moderator, author, and filmmaker Alexandra Weltz-Rombach explained, Wu Ming is a pseudonym for a group of Italian authors formed in Bologna after the experience of the Luther Blissett project. For almost 20 years the literary collective has been writing essays, meta-historical novels, and creative narrative, using often the techniques of investigative journalism. Today it is widely appreciated for its capability to deconstruct and analyse complex aspects of social and political life, challenging long-existing paradigms and traditions and synthesizing the views of different minds, to build an alternative narration on facts, inspiring unconventional critical process. Wu Ming 1 explored the Susa Valley and the woods occupied by police and wire fences, experiencing the struggle of a community in its territories, to write a history-as-novel take on the most enduring and radical environmental protest in contemporary Italy, known as No-TAV (TAV stands for Treno Alta Velocità – High Speed Train). To do so, he walked, mapped the territory, and ‘evoked ghosts’. The history of a country can be described by the history of its borders and the Susa Valley is a borderland in the mountains. Probably where Hannibal walked with his army to cross the Alps, since the early 90s it has been projected another huge tunnel inside the mountains, in a long-standing tradition of railroad-tunnels built sacrificing lives and health.

To understand the No-TAV struggle we can go back in time. To when the TAV-railway was first projected, and contextually the opposition of local communities started. But also, back in time to all the conflicts that have been fought on these mountains, which are “full of ghosts” as the author said. Wu Ming 1 explained that in literature and popular tradition, a ghost appears when there is an unresolved story, a wasted life that ended badly. Borderlands are the places where the most of ghosts are to be found. In the Susa Valley, ghosts are suppressed memories of wars and of social conflicts that shaped the territory.

Wu Ming published several works on environmental and climatic issues and wrote a lot about mountains too. Almost 78% of Italian territory is covered by mountains or hills. Their iconic representation has been at time twisted by nationalism, militarism and machismo. The Alps were “sacred borders of the fatherland” – nature to conquer, a symbol of virility and power in fascist propaganda. Today those mountains are an obstacle to economic growth; a growth that might put at risk the whole Susa Valley. Thus, instead of tackling legitimate concerns, project Stakeholders have been seeking for 20 years to delegitimize those leveling the charges against the high-speed railway, despite the masses of evidence to support their claims, using intimidation and violence against them. But the no-TAV collectives’ claims have always been proven to be right, and the project has been declining in size over time. However, the fight within the Valley is still on and the TAV-project is far from being archived.

The panel on the first day, EXPOSING ABUSES: Citizens Recording Human Rights Violations from the US to The Gambia, introduced by Michael Hornsby of Transparency International, opened with a presentation by Melissa Segura, journalist of BuzzFeed News from the US. She documented allegations proving that the Chicago police officer Reynaldo Guevara had framed dozens of innocent people for murder. The reporter put a light on forgotten judiciary cases, giving voice to families and communities affected by injustices, hit by a profound brokenness that she experienced herself when her nephew was framed and arrested years before.

A group of black and Latino mothers, aunts, and sisters knew that their beloved were innocent, but no officials wanted to take up their cause. Segura met these women after they had been fighting for decades in search of justice. They began when the journalist was at her elementary school: “at the time they had already gathered in a team, collecting data and writing spreadsheets on Lotus” she recalled. They had no chance to be heard, no PR, no lobby, no support from media were available to them. Segura realized soon that the story she had to cover wasn´t just the conviction of a 19-year-old-boy sentenced in 1999 with 110 years of prison for a murder he did not commit. It was also about the community of women that were fighting for justice, it was about their lives.

She learnt soon that her sources were able to cover their own stories much better than how she could, showing her new paths to the truth. The journalist dedicated time to building a trusting relationship with them, giving full reassurance that their story would be fairly reported. After an intense three-year investigation, she succeeded in wearing down a key witness to testify, cracking the wall of impunity. This process, she said, “did not expose the harm of people, but tried to connect to it.”

Reynaldo Guevara has been beating up people, framing them, extorting false confessions and false witnesses for years. Since publishing Segura’s articles, seven innocent men have been freed, and dozens more convictions are under review.

In the context of the major movements that draw attention on issues such as injustice and police violence targeting specific communities and minorities in the US, policy and data analyst Samuel Sinyangwe decided to join the work of justice activist groups formed after the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. He is now part of the Police Scorecard project, and of the Campaign Zero independent platform he co-founded, designed to facilitate and guarantee the collection of data on these violations. Sinyangwe explained that, as of today, the US government has implemented neither collections of data on police misconducts, violence and killings, nor public database of disciplined police officers. In his view, US law enforcement agencies have failed to provide even basic information about the lives they have taken, in a country where at least three people are killed by police every day and black people are 3 times more probable to end up victims of brutal use of force by the police.

The independent observatory built by Sinyangwe seems to be quite effective. It is described as the most comprehensive accounting of people killed by police since 2013 in the US. A report from the US Bureau of Justice Statistics estimated that approximately 1,200 people were killed by police between June 2015 and May 2016. The database identified 1.179 people killed by police over this same time period. These estimates suggest that it was able to capture 98% of the total number of police killings that occurred. Sinyangwe hopes these data will be used to provide greater transparency and accountability for police departments as part of the ongoing campaign to end police violence in black and Latino communities, leading to a change of policies.

With data able to map the situation in the US, it has also been possible to make comparisons and drew analyses. The Campaign Zero researches show that there is a whole false narrative about criminality rates, based on numbers that just mirror a system based on different federal policies regarding police forces, and that levels of violent crime in US cities do not determine rates of police violence.

According to data, cities with the same density of population have very different rates of violence, and very different rules regulating the activity of police agents. Starting from this, Sinyangwe and his team decided to look for different policy documents from different police department. These policies determine how and when a local policeman is authorized to use force. With a closer look, the Campaign Zero team could easily determine that there is no federal standard. Some documents live a grey area, others discourage the use of force, and particularly of deadly force, limiting it to the most dangerous scenarios after all lesser means of use of force have failed. Some seem to openly encourage it instead.

The group listed eight types of restrictions in the use of force to be found in these policies, consisting of escalators that aim at excluding, as far as possible, the use of violence. Comparisons show that a combination of these restrictions, when put in place, can produce a large reduction in police violence. Policies combining restrictions predicted indeed significantly lower rate of deathly force.

Data about unarmed people killed by police in major American cities show that black people are three times more likely to be killed by police than white people (2013-2018). Movements such as Black Lives Matter started also because of this. Another problem is that it is extremely difficult to hold US police members accountable.

Sinyangwe underlined how it is necessary to research the components that predict police violence, and that can help hold officers accountable, to be sure that they are enforced by police departments.

Police union contracts – for example – can be considered an obstacle on the way to accountability and transparency. It is extremely rare to have a policeman convicted for a crime in the US. It is a systematic fact and it cannot be reduced just to the individuals, who are acting using brutal and deathful force. It is a matter of lack of training, lack of policies enhancing non-violent solutions, but there is also legislation that protects policemen from legal consequences. It is not easy even to sue a US policeman, as they are shielded by qualified immunity and often by confidential police records, limiting how officers are investigated and disciplined. As of today, this makes impossible to identify and punish misbehaviours, abuses, and responsibilities in most cases. According to Mapping Police Violence, a research collaborative collecting comprehensive data on police killings to quantify the impact of US police violence in communities that Sinyangwe set up, 99% of cases in 2015 have not resulted in any officer involved being convicted for a crime.

The Campaign Zero platform is designed to be a tool able to enhance participation, foster accountability and transparency. It is an instrument to prevent killings and it calls for the adoption of a comprehensive package of urgent policy solutions – informed by data, research and human rights principles – that can change the way police serve communities.

The last panellist of the day was the participatory video facilitator from the UK, Gareth Benest, who presented the “Giving Voice to Victims of Grand Corruption in The Gambia” participatory video project. It is an initiative implemented on behalf of Transparency International in reaction to “The Great Gambia Heist” investigations by OCCRP (Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project) revealed in March 2019, which allowed those affected by grand corruption to share their stories and present their truths in carefully edited video messages, and to give voice to those Gambians who are deprived from access to basic health, education, agriculture, and portable drinking water.

In Gambia, a truth and reconciliation commission has begun to investigate rights abuses during the 22-year-long dictatorship of Yahya Jammeh ended in 2017. OCCRP has exposed for the first time how the corrupted dictator and his associates plundered nearly 1 billion US$ of timber resources and Gambia’s public funds. Thousands of documents dated between 2011 and 2016, including government correspondence, contracts, and legal documents, bank records, internal investigations able to define in detail the level of corruption and impunity of the Gambian system.

After the end of Jammeh’s rule, authorities have declared they will shed light on corruption, extrajudicial killings, torture, and other human rights violations. It is an important process of reconciliation, but still the voices of the marginalized and rural citizens are not heard. ‘Giving Voice to Victims of Grand Corruption in The Gambia’ was meant to facilitate a process with Gambian community members to express their perspectives on local problems and ideas, translating them into a film.

Benest explained how such a project is supposed to enable these communities to focus on the issues they are affected by and move towards changing their circumstances.

The participatory video is a technique that has been used to fight injustice in different contexts for many years. Benest recalled recent projects involving a community displaced by diamond-mining, young people excluded from poverty eradication strategies, widows made landless by customary leaders, and island residents threatened with forced evictions by land grabbers. In his work, the facilitator encourages equal participation and rotation of rules within the team. Participants control every aspect of the video making, from the process to the final result. Self-directed and self-organised videos become a communication tool that allows participant to build a dialogue for positive change.

The second day of the Disruption Network Lab conference opened with the keynote speech of Matthew Caruana Galizia, WHAT INDEPENDENT INVESTIGATORS DON’T USUALLY DISCLOSE, in which he addressed issues freelancers investigating high-level corruption face in silence and isolation, often with tragic consequences. The journalist, in conversation with Crina Boros, talked about the background of his mother, the Maltese reporter and blogger Daphne Caruana Galizia, who was killed on the 16th of October 2017, outlining the risks and the outcomes of her dangerous and brave work.

Her murder had been planned in detail for a long time. Killers were arrested, but the mandators haven’t been identified yet, and the criminal investigation is not moving forward. Daphne Galizia’s family is pushing the issue internationally and within Malta, knowing that without doing something this case would just disappear from news headlines without solution. Anti-corruption investigative journalists are arrested, threatened, and killed everywhere. People just vanish, and no justice is done.

For the 15 years before her death, Daphne Caruana Galizia had been appearing in 65 court cases filed against her. Her bank account was frozen; she was a victim of media campaigns against her; and she was sued by politicians, businessmen, and other journalists too. Her son recalled when he was nine that their dog was found slaughtered, then the front door of their house was burnt down. Later on, one of their dogs was shot, and another poisoned. Threats and violence continued until their whole house was set on fire. No investigation was ever effectively put in place to find out the perpetrators of these crimes, though the journalist and her family had always pressed charges against unknown.

It is hard to be confronted with the pain and memories of personal events on a stage in front of an audience, but the issue of justice is too urgent. Even if talking about her gets more and more difficult every time, Matthew is travelling the world to keep fighting and demand justice for his mother.

Matthew had spent the last years working with his mother. The International corruption revealed by the Panama Papers – on which they were investigating – was not cause of resignations and public assumption of responsibility in Malta. Involved politicians and news outlets attacked with all available means independent journalists covering the cases. The pressure on Daphne intensified in such a way, that she was sued 30 times just in the last year before her death. In those moments she kept repeating to his son Matthew that, no matter how hopeless the situation, there is an urgency to strive to make corruption and responsibilities publicly known. The Maltese blogger was not naive, she was well aware that there was the risk of getting killed, as it happened to Anna Stepanowna Politkowskaja and many colleagues all over the world. But she did not give in.

Reviewing his mother’s life, Matthew mentioned a further aspect to consider: Daphne had to use much of her time and money to defend herself inside trials against her, which were long and very expensive. She had passion and abilities. She was so talented that she could publish a magazine about food, architecture, and design – on which she spent just a couple of days a month – to earn money enough to carry on with her independent investigation work, and pay for her legal defence.

When there is a whole system against you, you need very good lawyers, you need expertise, you need money to pay for it. The Maltese blogger spent a whole career overcoming the obstacles of a corrupted system and she self-sustained economically, making sacrifices. Although all this, still, his son Matthew and her family are convinced that the solution must come through the judicial way, using available legal instruments, and making pressure on EU institutions at the highest levels. That is why Matthew Caruana Galizia asks everybody for commitment in a demand of radical change. Malta is part of the European Union, as he keeps on repeating.

Someone has been trying to silence Daphne for years before her murder. They must have gotten to the conclusion that the only way to shut her up was an assassination, for the purpose to cancel her stories with her, as her son Matthew sadly commented. To avoid this happening, several newspapers and investigative organisations joined the «Daphne Project» a global consortium of 18 international media including Reuters, The Guardian, and Le Monde, to continue the work of the Maltese journalist. They are led by the group Forbidden Stories, whose mission is to continue the work of silenced journalists. They stand together because they think that even if you kill a journalist like Caruana Galizia, her investigations cannot be buried with her. Thanks to the Daphne Project, and the courage and determination of Daphne Caruana Galizia’s family, her investigation lives on.

Matthew stressed the fact that it’s not about the future of one politician, or of a specific criminal group. It is about the future of Malta and the EU. Journalists who defend democracy are alone when they face the repercussions of what they do. It is necessary to make sure that when there are outcomes due to effective journalism, a society trained to react and self-organise can pick up the investigative work, defend independent investigation, and ask for political accountability within a public discussion. In Malta, nothing of this ever happened, and Daphne became more isolated.

Grassroot citizens organisations are fundamental to boost activism inside local communities and demand for justice. In cases like Daphne’s, no one is going to do it if not organised citizens, together with independent journalists and organisations. Many killed journalists had neither a family nor an organisation that could fight on for them. Maltese Police seem to have never developed professional skills to effectively work on this kind of criminal cases, and the few results from recent years were from the FBI in the USA. Criminals within a system that guarantees impunity can easily develop better skills.

Moreover, in Malta, investigations have a very poor rate of success and in Daphne’s case, we just know how she was murdered. But the political atmosphere, in which this murder matured, has been untouched for these last two years, and the journalist’s family is worried the official inquiry that just started in the country is neither independent nor impartial. Members of the Board of Inquiry, they claim, have conflicts of interests at different levels, either because they were part of previous investigations or because they have ties to subjects who may be investigated now.

In the last panel of the conference, as Bazzichelli explained, the discussion focused on the connection between grassroots investigations and data analysis, and how it is possible to make sensitive data accessible without restriction and open them to the public, facilitating the publication of large datasets.

M C McGrath and Brennan Novak, introduced by moderator Shannon Cunningham, presented a tool designed to enable the publishing of data in searchable archives and the sorting through large datasets. The group builds free software to collect and analyse open data from a variety of sources. They work with investigative journalists and human rights organisations to turn that into useful, actionable knowledge. Their Transparency Toolkit is accessible to activists and citizen journalists, as well as those who lack resources or technical skills. Until a few years ago only big media organisations with particularly good technical resources could set up such instrumentation. The two IT experts decided to increase the use and the impact of open information, considering participation as a key factor to reduce the difficulties caused by relying only on media outlets or single journalists to cover complex facts or analyse large datasets.

As M C McGrath and Novak explained, Transparency Toolkit uses open data “to watch the watchers” and to hold powerful individuals and groups accountable. At the moment, their primary focus is investigating surveillance and human rights abuses, like in the case of the Hacking Team leaks in July 2015.

Hacking Team is an Italian company specialising in surveillance software and in very effective Trojans able to slip into computers and smartphones, allowing a secret and total surveillance. Four years ago, 400 GB of their data was anonymously published online, showing how the IT company had been working for authoritarian governments with questionable human rights records, to ensure they can use such software to spy on activists, journalists, and political opponents, in countries like Morocco, Dubai, Ethiopia, Mexico and Sudan. Transparency Toolkit mirrored the full Hacking Team dataset to make it more available to journalists and security researchers investigating these issues. It released a searchable archive of 200GB of emails categorized by companies, countries, events, and other subjects discussed.

Other important projects from the Transparency Toolkit team are the Surveillance Industry Index (SII) developed together with Privacy International (a searchable archive featuring over 1500 brochures about surveillance technology, data on over 520 surveillance companies, and nearly 500 reported exports of surveillance technologies), the Snowden Document Search (the first comprehensive database of Snowden documents initiated which aims to preserve its historical impact), and ICWATCH – a platform born to collect and analyse resumes of people working in the intelligence community, contractors, the military, and intelligence. These resumes are useful for uncovering new surveillance programs, learning more about known codewords, identifying which companies help with which surveillance programs, examining trends in the intelligence community, and more. ICWATCH provides a collection of over 100,000 of these resumes from LinkedIn, Indeed, and other public sources, and now searchable with a search engine called LookingGlass.

The last part of this panel was than dedicated to the Dictator Alert project, a website that tracks the planes of authoritarian regimes all over the world. Available networks censor the information about planes of intelligence, military, authorities, and heads of state. This project, run by Emmanuel Freudenthal and François Pilet with support from OCCRP, began as an open-source computer program to identify planes belonging to dictators flying over Geneva. The program mined data from a network of antennas used by plane spotters and shared its alerts via Twitter. Today, Dictator Alert uses data from ADSB-Exchange, as well as several antennas installed by the team of researchers themselves. The details of each plane captured by the antennas are compared with a list of aircrafts registered or regularly used by authoritarian regimes. When a match is found, a message is published on the website.

Freudenthal presented the methodology of acquiring information behind Dictator Alert. Some people in the audience disagreed with the panellists, arguing that a reductive definition for ‘dictator’ might questionably influence the outcomes of the project, considering that some elected leaders from countries listed as democracies are also responsible for crimes, secrets, and human rights violations. The investigative journalist responded by explaining that Dictator Alert is orientated using the Democracy Index published by The Economist. The Index appeared first in 2006, categorising countries as full democracies, flawed democracies, hybrid regimes, and authoritarian regimes, based on 60 indicators grouped in different categories, measuring pluralism, civil liberties, and political culture.

The Disruption Network Lab organised the workshop Berlin’s Sky, An Afternoon Investigation on the day following the 17th Conference. Participants gathered in the former Berliner airport Tempelhofer Feld to conduct guided research using antennas and laptops to track the sky and spot anomalies above the city.

The conference closed with the investigation by Forensic Architecture – Horizontal Verification and the Socialised Production of Evidence. Team member Robert Trafford presented the organisation founded to investigate human rights violations using a range of techniques, flanking classical investigation methods including open-source investigation video analysis, spatial and architectural practice, and digital modelling. They work with and on behalf of communities who have been affected by state and military violence, producing evidence for legal forums, human rights organisations, investigative reporters and media, as well as for arts and cultural institutions.

In Trafford´s analyses, conflict, violence, and human rights violations have become heavily mediatised and because of the “open source revolution” and smartphones, facts are often documented and relayed to the world by fragments of video material. Media sometimes report about these facts in ways which seem to make them less clear, instead of allowing better understanding. Forensic Architecture is in part a set of technical and theoretical tools for unpacking those mediatised facts, to access the truth which often exists behind and between the fragments of files that are released or leaked, to prove human rights violations. It relies on the prevalence of open source video material and tries to put an order in the fake-news and post-truth communication, offering a new model for collectively and collaboratively constructing truths. Trafford pointed out how people today, who seem to be widely rejecting the idea of institutions that they might previously have trusted to assemble facts and information, are still able to accomplish this delicate task. Often truth seems to be created elsewhere, possibly behind a wall of closed sources. The Internet and the consequent open-source revolution exploded the stability of that classic system of information, and those institutions are no longer providing truths around which people are willing or able to orient themselves. For better or worse, the vertical has been supplanted by the horizontal, Trafford said.

As those institutions falter, there is a certain breed of political actors – largely from populist and far-right parties – that have been gaining mediatic and institutional power all over the world for the last five years, encouraging the public to believe that our societies are soaked in misinformation, and that there is no possibility of reaching out and acquiring reliable facts we can all agree on and orient ourselves with.

More and more often, online and offline, we read of individuals saying that we should not trust traditional news outlets or institutions that encourage us to believe that they can guarantee independent and free information. It is under this cover of equivocation and uncertainties that the human rights violations of the 21st century are being carried out and subsequently concealed.

Forensic Architecture’s challenge is to expose this misrepresentation of things, and to offer a kind of counter truth to official versions of relevant facts. Its researchers collect little grains, clues they find inside videos, pictures, and articles that try to organise in certain ways, reassembling them into an independent analysis. By using different perspectives into ongoing practice in which the development of facts and evidence is socialized, the project encourages open and horizontal verification.

The moderator of this last session of the conference, Laurie Treffers, mentioned the idea of counter forensics. By integrating and working across different forms of knowledge, and across different institutions and disciplines – which may at times appear like they have nothing in common or that they speak in entirely different registers – horizontal verification is about unifying those for reasons of mutual protection, mutual security, and mutual reinforcement.

Trafford gave examples of Forensic Architecture’s work, such as working closely with the Gaza-based Al Mezan Center for Human Rights, the Tel Aviv-based Gisha Legal Center for Freedom of Movement, and the Adalah Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Haifa, when they examined the environmental and legal implications of the Israeli practice of aerial spraying of herbicides along the Gaza border.

To this end, the investigation sought to define if and how airborne herbicides travel into Gaza; how far into its territories they entered; what concentration of herbicide and what damage to the farmland on the Gazan side of the border can be calculated. The analysis of several first-hand videos, collected in the field, revealed that aerial spraying by commercial crop-dusters flying on the Israeli side of the border generally mobilises the wind to carry the chemicals into the Gaza Strip at damaging concentrations. This is a constant primary effect.

The videos used for the investigations supported the testimonies of farmers that, prior to spraying, the Israeli military uses the smoke from a burning tire to confirm the westerly direction of the wind, thereby carrying the herbicides from Israel into Gaza.

Forensic Architecture modelled the Israeli flight paths and geo-located them, compared metadata and video material, and engaged fluid dynamics experts from the University of London to look at what the potential distribution of those chemicals would be from the heights that the plane was flying, in the wind conditions that could be calculated. The investigation proves that each spray leaves behind a unique destructive signature.

“Along with the regular bulldozing and flattening of residential and farmland, aerial herbicide spraying is one part of a slow process of ‘desertification’, that has transformed a once lush and agriculturally active border zone into parched ground, cleared of vegetation,” Trafford said.

Analyses of the evidence derived from vegetation on the ground, civilian testimony, and the environmental elements mobilized in the spraying event showed that the Israeli practice of aerial fumigation at times when the wind is blowing into Gaza causes damage to farmland hundreds of meters inside the fields.

Once again, the Disruption Network Lab created a forum for discussion, to define the role of citizens in making a change in the information sphere, highlighting local and international stories, tools, and tactics for social change built on courageous grassroots reporting and investigations. The Disruption Network Lab invited guests to challenge laws that effectively criminalise journalism and whistleblowing. The conference went beyond the usual dichotomy between journalists and activists, official media and independent media, and opened up a dialogue among different expertise to discuss and present opportunities of collaboration to report misinformation, corruption, abuse, power asymmetries, and injustice.

CITIZENS OF EVIDENCE presented experts working on anti-corruption, investigative journalism, data policy, political activism, open source intelligence, video storytelling, whistleblowing, and truth-telling, who shared community-based stories to increase awareness on sensitive subjects. Bottom-up approaches and methods that include the community in the development of solutions appear to be fundamental. Projects that capacitate collectives, minorities, and marginalized communities, to develop and exploit tools to systematic combat inequalities, injustices, and impunity are to be enhanced.

Moreover, on the 29th of October, the CPJ published the 2019 Global Impunity Index, putting a spotlight on countries where journalists are slain and their killers go free. During the 10-year index period, 318 journalists were murdered for their work worldwide and no perpetrators have been successfully prosecuted in 86% of those cases. Last year, CPJ recorded complete impunity in 85% of cases. Historically, this number has been closer to 90%. All participants at the conference expressed their concern about this situation.

It is important to doubt and require a double-check over relevant news, as governments and private corporations have proved too often, that they prefer secret and manipulation to transparency and accountability. It is also important to verify constantly if media outlets, or a single journalist, are actually independent. But this shall not be used to weaken independent information and undermine the principles of particular constitutional importance regarded as ‘higher law’ on which it is based. Journalists and citizen reporters are already alone in their work.

CITIZENS OF EVIDENCE was curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, developed in cooperation with Transparency International. It was the third in Disruption Network Lab’s 2019 series ‘The Art of Exposing Injustice’. Videos of the conference are also available on YouTube. For details of speakers and topics, please visit the event page here: https://www.disruptionlab.org/citizens-of-evidence.

To follow the Disruption Network Lab, sign up for its newsletter with information on conferences, ongoing researches, and projects. You may also find the organisation on Twitter and Facebook.

The next Disruption Network Lab event ‘ACTIVATION – COLLECTIVE STRATEGIES TO EXPOSE INJUSTICE’ is planned for November 30th, in Kunstquartier Bethanien Berlin. More info here: https://www.disruptionlab.org/activation

Image Credit:

Elena Veronese for Disruption Network Lab

Featured Image:

Graphic courtesy of Disruption Network Lab