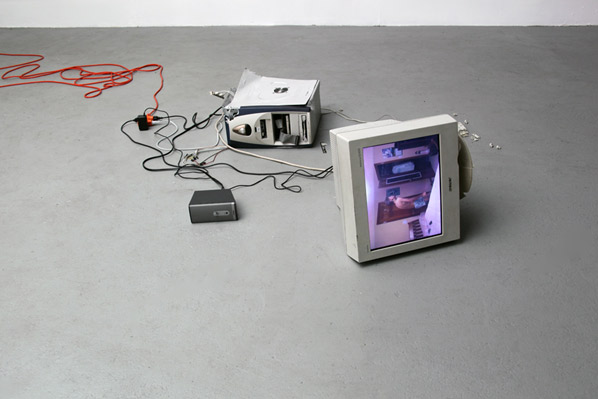

Featured image: Internet Cache Self Portrait, 2012, Evan Roth

In an essay for the catalog of Collect the WWWorld: The Artist as Archivist in the Internet Age, an exhibition installed most recently at 319 Scholes in Brooklyn, Josephine Bosma announces that the wilderness is back. Though modernity provided the means for humans to sequester themselves safely in comfortable houses, sheltered from nature’s seasons and its bad moods, Bosma points out that the boundaries between the indoors and outdoors, between the private and the public, have been broken down by digital technologies. As data slips into our most intimate spaces, the way rain and wind once ripped through primitive shelters like caves and huts, we return to “a rather basic form of humanity”―an uncanny “21st century version of ancient cultures and traditions.” Sorting through an “erratic, uneven mess” of information, human beings are once again hunters and gatherers. [1]

Yet if hunting and gathering are back in digital form, the foraging is not taking place in a scarce economy. We are not looking across vast space for some edible calories, stalking after evasive prey. Instead, we are flooded with resources in an official archive that grows at almost unfathomable speeds. In his catalog essay, curator of Collect the WWWorld, Domenico Quaranta writes,

“Every time we access a web page… the browser memorizes certain data on our computer… whatever we don’t deliberately delete, we keep. In the cache era, accumulating data is like breathing: involuntary and mechanical. We don’t choose what to keep… but what to delete.” [2]

The artists in the 319 Scholes exhibition appropriated and manipulated images, data, animated gifs, video, clip art, and blogs to create screen projections, net art, prints, and installations. Often they transferred foraged data into sculptural pieces, such as the series of pocket bikes by Jon Rafman and the photocopier run amok in Jason Huff’s Endless Opportunities, suggesting that online information moves in and through our material world. Moving through the gallery made me feel like I had spent too much time online, overwhelmed by too much information. There were hundreds of polaroids in Alterazioni Video’s Olbania, hundreds of images in Evan Roth’s collage Internet Cache Self Portrait: July 17, 2012. The title of the seemingly nonsensical Etsy purchase by Brad Troemel, displayed on the gallery wall, captured the detailed randomness of the internet space: Art Smells Why Wait Grab An Unusually Decadent PINE air freshener with a HOTTOPIC pink to black hair extension attached. The sounds of Eva & Franco Mattes’ My Generation dominated the gallery’s front space. In a pile of smashed computer hardware, a screen displayed videos of hormonal teenage boys freaking out, screaming, and convulsing in front of their computer cams. The collage captures the overflowing, hysterical emotions of adolescents in their now private-public bedrooms but also the frustration that we can feel about life amidst so many networked devices and so much data.

Since many of the works at 319 Scholes made me feel psychologically unsettled and dispersed, the same way I feel after staring at a screen all day long―a feeling that I can fix only by unplugging and taking my dog for a walk―I asked Quaranta how he differentiates Collect the WWWorld artists from the larger population of people interacting with data as simply just hunter-gatherers on an everyday basis. How did he imagine the exhibition representing something beyond what we all do continually, as naturally as breathing? His response:

“Everybody stores, but just a few collect. Storing means downloading (or tagging, pinning, posting, etc.) something and forgetting about it. Collecting means taking care of what you stored, selecting and ordering it according to a personal criterion, applying a human filter to the inhuman, impersonal archive. If the collector is an artist, his collection may be sometimes understood as art.” [3]

If we keep with Bosma’s ecological metaphor, Quaranta’s exhibition, then, presents artists who are also collectors and archivists who, having explored the digital wilderness, have done some weeding in order to plant a garden of cultivated, nurtured, looked-after data. Their art is a gesture toward trying to make some sense or order out of the wildness. In his catalog essay, Quaranta writes,

“Collect the WWWorld takes as its point of departure the very moment an incoherent mass of ideas turns into a hypothesis.” [4]

Yet ever since digital media emerged on the contemporary art scene, artists have been appropriating found “objects” from the internet’s ever-growing archive, remixing them to create new content. But there is a significant way in which Collect the WWWorld captures a new cultural current. Traditionally, archives were protected spaces, governed by authorities, institutions, the state. They were private, physically and politically remote from the public at large, inaccessible except to sanctioned experts who were able to pass through the proper channels of bureaucracy. Digital technologies upended this sanctified space, producing an unofficial endless archive of internet data, and more recently, with ubiquitous mobile networked devices and social networking applications, anyone can upload any random aspect of their mundane private lives into the public archive. Quaranta explains,

“If in the past, and still in the late Nineties, appropriation and remix were dealing mostly with commercially produced culture, now most of the cultural content we access, consume and remix is produced by so-called amateurs.”

In the Web 2.0 world of YouTube and Facebook, brokers, editors, and even curators are no longer indispensable. There are no intermediaries between public and private in the digital wilderness. Furthermore, Quaranta adds, early generations of digital artists were pioneers. Now, the born-digital artist-collectors are “residents dealing with the stuff left by their ancestors.” [5]

In this exhibition of second-generation digital art, the most intriguing works in the show were those that did not simply repeat and represent the experience of hunting-gathering in the wilderness but rather intervene in this process to suggest the ways that media technologies rewire our culture, our public/private spaces, and our imagination. In Kevin Bewersdorf’s Google Image Search Result for “Exhausted” Printed onto Blanket, an image of an emotionless father holding a passed out son in his arms. (I’m guessing at their roles; the situation could be much less innocuous.) With the printing of this random, private scene onto a blanket, someone could actually sleep in with this odd couple, laying his skin next to theirs. The networking of such intimate moments is at once ludicrous, meaningless, and meaningful―and something that those of us with web access experience all the time.

In need ideass!?! PLZ!!, Elisa Giardina Papa has collected online video of mostly teenage girls excited to make new video content except they have one major problem: they have no ideas. The projection at 319 Scholes showed them speaking intimately into their video cams, begging their viewers to help them, confessing their willingness to do anything asked of them:

“Hi YouTube, Hi you guys, Hey um YouTube…. I wanted to start a web show and I need ideas for it but I don’t know like any ideas. I have the web show maybe an upcoming website, who knows… Hey YouTube. I’m behind my kitty cat right here. If you guys can give me some ideas I’d greatly appreciate it… Hi you guys I’m Vanessa I’m wondering if any of you can give me any ideas….”

need ideas!?!PLZ!!, Elisa Giardina Papa, 2011

One girl sits on her bed in her pajamas, another stands in front of a shower curtain. Most play with their hair, some have done their makeup, one provides a close up of her glossy pink lips. The kids repeat their willingness to “do anything… crazy stuff.” We often hear laments these days about how new media generate a culture without substance. Papa’s collage―or rather, her collection―deepened this question: the kids turned loose in the digital wilderness seemed to be aimless, armed with advanced technologies but with no ideas about what to say or what to do. At the same time, they perform Bosma’s “21st century version of ancient cultures and traditions.” Papa’s anxious teenagers seek attention, community, and space away from their probably boring parents, a rite of passage of American kids; one girl has to yell into her cellphone at her mother, “Mom! I’m in the middle of a video!” But though they are in the privacy of their bedrooms, they are also begging strangers for engagement and uploading themselves into the public space of the internet, where presumably annoying Moms can check on what they are doing.

In environmental theory, the wilderness can be a spiritual refuge, a space of healing respite from the frenzied modern world. But being out there, exposed, in the wildness of the mountains or the woods is comforting only once we have our biological needs met, once we are safe and ecologically emancipated by adequate shelter, clothing, and food. Social ecologist Murray Bookchin explains this well: “without a sufficiency in the means of life, life itself is impossible, and without a certain excess in these means, life is degraded to a cruel struggle for survival.” [6] With Bosma’s language in mind, I have to ask if Collect the WWWorld represents our ecological emancipation and our freedom to play in a mysterious forest, or if the group exhibition represents our desperate grasp for the basic anchors of cultural subsistence? Evan Roth’s Internet Cache Self Portrait: July 17, 2012 asks who we are in the eyes of our computers, in the accumulated images stored in our cache capturing our travels through the web. Are we the sum of our clicks and searches? Are we the archivists or are we the archived? Are we in control here, or are we engaged in a “cruel struggle for survival” in the digital wilderness?

Collect the WWWorld is a show first produced by the Link Center for the Arts of the Information Age and already presented, in different versions, at Spazio Contemporanea, Brescia (Italy) in September 2011 and at the House of Electronic Arts Basel (Switzerland) in March 2012. The presentation at 319 Scholes, Brooklyn, open from 10/18-11/4, 2012, featured a number of new artists and works in a brand-new arrangement. The show relies on an ongoing research project that can be followed online at http://collectheworld.linkartcenter.eu.

Participating artists include at 319 Scholes included: Alterazioni Video, Kari Altmann, Gazira Babeli, Kevin Bewersdorf, Aleksandra Domanovic, Constant Dullaart, Elisa Giardina Papa, Travis Hallenbeck, Jason Huff, JODI, Olia Lialina & Dragan Espenschied, Eva and Franco Mattes, Oliver Laric, Jon Rafman, Ryder Ripps, Evan Roth, Ryan Trecartin, Brad Troemel, Penelope Umbrico, and Clement Valla.