“Flexicity, information city, intelligent city, knowledge-based city, MESH city, telecity, teletopia, ubiquitous city, wired city… [what is] a city that dreams of itself?” (Jones 2016).

This April, 28 brave souls came together for the first time to explore algorithmic ghosts in Brighton — a city known for its blending of new-age spiritualities and digital medias, but perhaps not yet for its ghosts — through the launch of a new psychogeography tour for the Haunted Random Forest festival. Unveiling machine entities hidden within seemingly idyllic urban landscapes, from peregrine falcon webcams to always-listening WiFi hotspots, we witnessed a new glimpse of an old city, one that afforded many strange moments of unexpected (and perhaps even radical!) wisdom regarding the forgotten structures, algorithms and networks that traverse Brighton daily alongside its human inhabitants.

This intervention found its greatest inspiration in the playful, crtitical, anti-authoritarian strategies of the Situationist International group that was prominent in 1950s Europe and birthed the fluid concept of dérive or “drift”, a new method for engaging with cities like Paris through “psychogeographic” walks that charted increasingly inconsistent evolutions of urban environments and their effects on individuals. “Perhaps the most prominent characteristic of psychogeography is the activity of walking,” explains Sherif El-Azma from the Cairo Psychogeographical Society. “The act of walking is an urban affair, and in cities that are increasingly hostile to pedestrians, walking [itself]… become[s] a subversive act.”

Psychogeographical drifts have been interpreted in many ways in many places, from radical city tours with no set destination, to public pamphlets meant to shock people out of their daily urban routines, to unsanctioned street artworks that explore changing architectures and hegemonies of the built environment through direct dialogues. As the Loiterer’s Resistance Movement explains, “We can’t agree on what psychogeography means, but we all like plants growing out of the sides of buildings, looking at things from new angles, radical history, drinking tea and getting lost, having fun and feeling like a tourist in your home town. Gentrification, advertising, surveillance and blandness make us sad… our city is made for more than shopping. We want to reclaim it for play and revolutionary fun.”

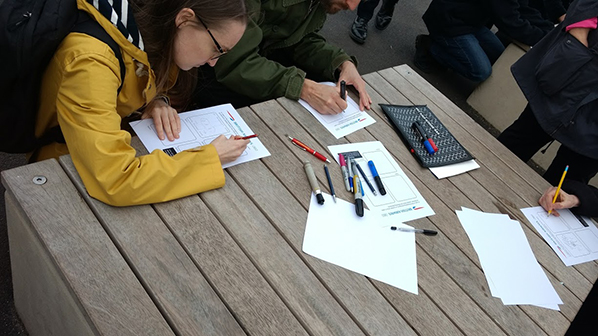

In our own interpretation of the psychogeography “play box“, people from across the UK came together from local community discussion lists, universities and creative networks to join the group. We called them ‘node guardians’ to connote a shared sense of ownership regarding both the tour nodes (which were lead not only by ourselves but also by several other brave participants, who also facilitated hands-on activities to engage listeners more deeply in the lived experiences of each machine node). We were intrigued about the moments of access, control and liberation that might be exposed when the machines, networks and algorithms that we engage with on a daily basis were revealed. In the unearthing of lesser-known instances of code-based activity (and the patterns within), we hoped to meet machine spirits, languages and loves along the way. And meet them we did.

Although the tour aimed to seek out algorithms and machines, we didn’t feel limited to influences from our current digital age. Brighton has a rich history of invention and engineering which has influenced the local geography as well as wider culture. The ghosts of Magnus and George Herbert Volk, father-and-son engineers, can be found all over the city, from Magnus Volk’s seafront Electric Railway which opened in 1883 — making it the oldest working electric railway in the world — to George’s seaplane workshop in the trendy North Laine shopping area, which went on to house a thoroughly modern digital training provider, Silicon Beach Training. Magnus Volk’s most unusual invention, though, only exists as a part of Brighton’s colourful history: the Brighton and Rottingdean Electric Railway, as it was officially called, earned the nickname the ‘daddy-long-legs railway’ as it ran right through the sea with the train car raised up above the waves on 7-meter-long legs. The railway was only in operation for 5 years from 1896 to 1901, but you can still see some of the railway sleepers for the tracks along the beach at low tide.

For a relatively small town, Brighton also played a surprisingly big role in the development of the international cinema industry. In the 1890s and 1900s, a group of early filmmakers, chemists and engineers called the Brighton School pioneered film-making techniques such as dissolves, close-ups and double exposure, and created new processes for capturing and projecting moving images. Key members of the group used the old pump house in local pleasure garden St Ann’s Wells as a film laboratory and shot the world’s first colour motion picture called ‘A Visit to the Seaside’ in Brighton in 1908, using a colour film process called Kinemacolour invented by the group. Although the city’s early passion for cinema is remembered by several blue plaques marking key locations — and the presence of the Duke of York’s cinema, the oldest continually operating cinema in the UK — we wondered how much of Brighton life had been captured in the dozens of short films made at the turn of the century, only to be lost forever?

The rest of the stops on our walking tour took in more contemporary machine ghosts, including the last remaining trace of the city’s USB dead drop network — conveniently embedded in a brick wall on the seafront above the Fishing Museum — which prompted us to ask what information people may have passed to each other before these devices were destroyed by weather and vandals. Dead drops were originally set up to be an anonymized form of peer-to-peer file-sharing that anyone could use in public spaces. They have since been embedded into buildings, walls, fences and curbs across the world. Perhaps some of our tour participants will even be inspired to set up new dead drops around the city to keep the potential for off-grid knowledge-sharing alive.

In a reversal of this spirit of anonymous digital communication, a new network of WiFi-enabled lampposts, CCTV cameras and other pieces of ‘street furniture’ has been unobtrusively installed across the city by BT, in partnership with Brighton & Hove City Council. They now eavesdrop on the personal musings of passers-by who connect to them. These hidden devices provide users with a free WiFi service, but the group wondered at what cost. Participants found themselves questioning whether BT can be trusted to keep our information secure in an age where data has become a valuable marketing commodity.

As part of our psychogeographical aim to unveil the hidden lives of once-familiar urban artefacts, we also summoned the machine ghosts of some of Brighton’s most famous (and infamous) landmarks. Looming over the city centre is a towering modernist high-rise called Sussex Heights, a building that sticks out like a sore thumb amidst the classic Regency architecture of the city’s Old Town. Yet atop the concrete tower also live families of peregrine falcons, whose nesting activities are broadcast to the world by an ever-watching webcam. Conservation groups, architects and technologies intersected in 1990 to provide a nesting box that would enable the falcons, extinct in the area at the time, to successfully breed. They now return to the tower block every spring to rear their young (except in 2002, when they chose the West Pier instead). Writing down our best wishes to this season’s hatchlings, we pasted them onto the building for future city ghosts to browse.

The other most visible instance of architectural and structural technologies descending upon the city can be seen in the new British Airways i360 viewing tower, variously described as a ‘suppressed lollipop’, a ‘hanging chad’, ‘an oversized flagpole’, an ‘eyesore’ and a ‘corporate branding post’. Even if you leave the city, you can’t get away from the sight of the 162-metre tall tower, as it is equally visible from the countrysides surrounding Brighton. It overshadows its neighbour, the beloved remains of the burnt-out West Pier, and opened exactly 150 years after the West Pier first opened in 1866. However, the ‘innovation’ in the i360’s name may be a boon to the city, as it’s expected to pour £1 million a year in the local community and potentially inspire the renovation of the West Pier. Our node-guardians bravely attempted a participatory activity outside the i360 which involved sketching out mock flight warnings to those who entered its gates; the mock flight attendants situated at the base of the i360 were less than amused by these efforts.

In most towns, the shopping centre becomes a well-known haunt for both locals and visitors to congregate, yet most people who visit Brighton’s Churchill Square shopping mall pass by the square’s large pair of digital sound sculptures without even a glance. The sculptures look like a pair of matching stone and bronze spheres, and are the type of public art that you can walk past everyday without actually looking at, but after looking into their always-observing faces once, you’ll never miss them again. They quietly interact with the sky every day through a set of complicated light sensors that trigger a series of musical notes tuned in to each orchestration and angle of the sun. As the sun rises, they call out to one another, their combined song fading away as the sky turns dark. Or at least, we are told they communicate; after a group activity to emulate the interactivities of the spheres, we found ourselves quite unsure if we had actually heard ghostly spherical music emanating from spherical mouths, or just the sound of shoppers and buses passing by.

And finally, if you’ve lived in Brighton for a while you’ve probably come across the French radio station FIP, which until a few years ago you could tune into on radios across the city. While standing in the bustling North Laine cultural quarter, we were briefly transported to Paris by one of our node guardians’ melodica renditions of Parisian cafe music, and heard the story of how a local resident introduced Brighton to FIP in the late 1990s when they started re-broadcasting the radio station out over the city. It became one of the most popular radio stations in town and transmissions continued until 2013, even surviving an Ofcom raid on the mystery broadcaster’s house in 2007 when their equipment was confiscated. The story of Brighton’s love for FIP radio, including a monthly fan-organised club night called Vive La FIP that joyously ran from clubs around the city for years, shows that as well as its own ghosts, our city is also haunted by the machines of distant places.

Indeed, from the distant ghosts of rebellions past to those who quietly slip by underfoot as we walk to the pier, the derives of this tour taught us that unearthing hidden histories of a city can bring both good and bad spirits back to life — moments of local liberation and defiance existing alongside a national state of increased surveillance, conglomeration and control. We call for future tours, psychogeographic and otherwise, that challenge participants to think about Brighton through new forms of engagement that focus on grassroots and community efforts, and their implications in the spaces and places we use every day. Only then can we determine whether the ghosts that surround us are in charge of our fates, or whether the myriad past and present struggles of this city can co-exist in collaboration.