In the 1990s the idea of the virtual idol singer escaped from Macross Plus’s Sharon Apple and William Gibson’s Rei Toei into the cultural imagination. Blank slates for market forces and projected desires, virtual idol singers differ from Brit School drones only in that there is no meat between the pixels and the data.

Hatsune Miku is a proprietary speech synthesis program with an accompanying character whose singing the software notionally renders. Miku the software is a “Vocaloid” synthesizer using technology developed by Yamaha and the sampled voice of voice actor Saki Fujita. Released in 2007, with additional Japanese voices in 2010 and an English version in 2013, the software topped the charts in Japan on release and has led to spin off games and 3D modelling software. It’s claimed the software has been used to produce over 100,000 songs.

Hatsune Miku the character is a cosplayer’s dream, a sixteen year old (with a birthday rather than a birthdate) Anime young-girl with impossibly long aqua hair (there are male Vocaloids as well). She’s had a chart-topping album, “Exit Tunes Presents Vocalogenesis feat. Hatsune Miku” (2010), and started performing “live” on stage in 2009 with Peppers Ghost-style technology. She’s available as (or represented as) figurines, plushes, keychains, t-shirts, and all the other promotional materials produced for successful Anime characters, pop stars, or both. Her likeness can be licensed automatically for non-commercial use. This makes her fan-friendly, although not Free Culture, and means that fan depictions and derivations of her are widespread. The majority of “her” songs are by fans rather than commercial producers.

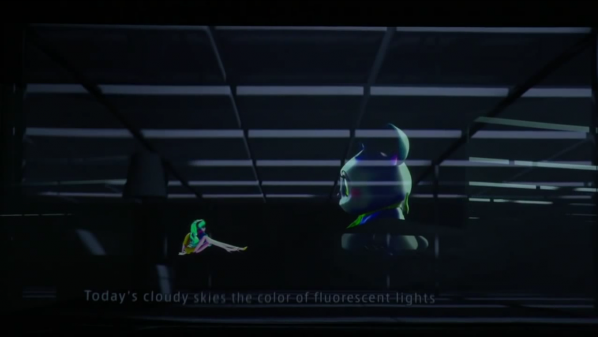

She is now appearing in “The End” (2013), a posthuman Opera (with clothes by a designer from artist-suing fashion company Louis Vuitton) where she takes the stage as a projection among screen-based scenery without a live orchestra or vocalists. Which means that someone programmed the software to produce synthesized vocals and someone else negotiated the rights to use the likeness of the characted commercially dressed in a particular designer’s virtual clothing. “She is now appearing” is easier to say, but like Rei Toei this is an anthropomorphised representation of the underlying data.

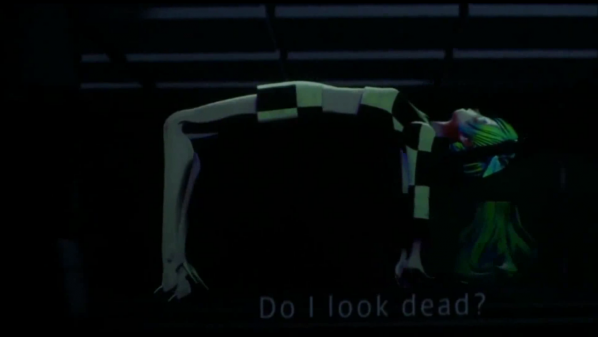

It’s getting rave reviews, and the music is competent, enjoyable and affecting: strings, electronica and Supercollider-sounding glitches and line noise under breathily cute synthesized vocals. The visuals are CGI with liberally applied glitch aesthetics, mostly featuring Hatsune Miku and a cute chinchilla-ish animal sitting in or falling through space. The plot is a meditation on what mortality and therefore being human can possibly mean to a virtual character. To quote the soundtrack CD booklet notes:

Miku, who has had a presentiment of her fate, talks with animal characters and degraded copies of herself to ask the age-old questions ‘what are endings?’ and ‘what is death?’.

The phantom in this particular opera is composer Keiichiro Shibuya, who appears onstage largely hidden by two smaller projection screens. As the man behind the curtain it’s tempting to read him as the male agent responsible for the opera’s female subject’s troubles. His presence onstage also threatens to make him the human subject of what is intended to be a repudiation of opera’s European anthropocentrism. But without such an anchor the performance would seem less live and perhaps become cinema rather than opera. It seems that a posthuman opera needs a human to be post.

Music production is uniquely suited to the creation of virtual characters through tools, brands and fandoms. Hatsune Miku functions as a guest vocalist, a role combining artistic talent and social presence with a well understood standing in the economics of pop. In art, Harold Cohen‘s sophistiated art-generating program AARON was licensed as a screensaver anyone could run to create art on their Windows desktop computers, but despite its human name and human-like performance, AARON is never anthopomorphised or given an image or personality by Cohen. Could a virtual artist combining software and character similar to Hatsune Miku function in the artworld or in the folk and low art of the net and the street?

The license for Hatsune Miku the character is frustratingly close to a Free Culture license. Could a free-as-in-freedom Hatsune Miku or similar character succeed? Fandom exists as an ironisation of commercial culture, appropriating mass culture in a bottom-up repurposing and personalisation of top-down forms. Without the mass culture presence of the original work, fandom has no object. Perhaps then without the alienation that fandom addresses, shared artistic forms would not resemble fandom per se.

There are precedents for this. Collaborative personalities abound in art, such as Luther or Karen Blisset. And in politics there is Anonymous. There are also existing Free Culture character like Jenny Everywhere, or even the more informally shared Jerry Cornelius. So it is possible to imagine a Free Software Hatsune Miku, but it’s less easy to imagine what need this would meet.

Unlike the idol signers of literature and television, there’s no pretence that Hatsune Miku is an artificial intelligence. But she is an artifical cultural presence, created by her audience’s use of her technical and aesthetic affordances. Like the robots in Charles Stross’s “Saturn’s Children” (2008), Miku’s notional personhood (such as it is) is defined legally. As a trademark and various rights in the software rather than as a corporation in Saturn’s Children, but legally nonetheless. Heath Bunting’s “Identity Bureau” shows how natural and legal personhood interact and can be manufactured. It’s tempting to try to apply Bunting’s techniques to software characters. If Hatsune Miku had legal personhood, would we still need a human composer onstage?

“The End” was written by that human composer, but software exists that can generate music and lyrics and to evaluate their chances of being a top 40 hit. Combining these systems with software made legal persons would close the loop and create a posthuman cultural ecosystem that would be statistically better than the human one, which I touched on here. It’s not just our jobs that the robots would have taken then. Given the place of music in the human experience they would have taken our souls.

Or the soullessness of Fordist (or Vectorialist) pop. Such a posthuman music system would exclude the human yearning and alienation that fan producer communities answer. It would be an answer without a question. Hatsune Miku is in the last analysis a totem, the products incorporating her are fetishes of the hopeful potential that pop sells back to us.

Despite “The End”, Hatsuke Miku has no expiry date and cannot jump a shuttle offworld. It’s not like she’s going to marry a fellow pop star or come tumbling out of networked 3D printers. But human beings are becoming less and less suitable subjects for the demands of cultural and economic life. In facing our mortality for us Hatsune Miku may have become more human than human.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.