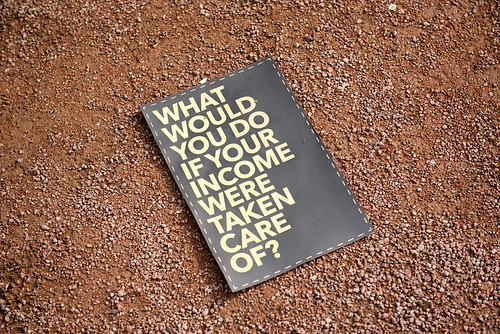

Announcing a new film and groundbreaking collaboration

The Blockchain: Change everything forever WATCH HERE

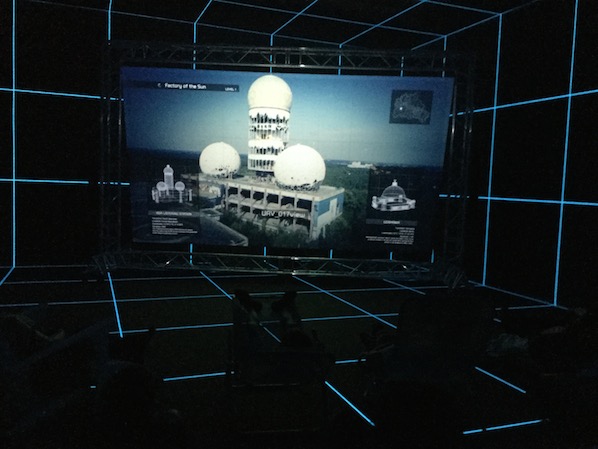

This new film released online on 3 October 2016 by Furtherfield in collaboration with Digital Catapult broadens the current debate about the impact of emerging blockchain technologies.

The underpinning technology of Bitcoin digital currency, the Blockchain is reshaping concepts of value, trust, law and governance. This film sets out to diversify the people involved in its future by bringing together leading thinkers, computer scientists, entrepreneurs, artists and activists who discuss:

What can a blockchain do?

Who builds this new reality?

How will we rule ourselves?

How will the future be different because of the Blockchain?

This is a unique collaboration between Furtherfield, dedicated to new forms of cooperation in arts, technology and society and Digital Catapult, an organisation dedicated to growing the UK digital economy.

DOWNLOAD

PRESS RELEASE (.pdf)

TRANSCRIPT (.pdf)

Directed by Pete Gomes

Concept, research and development by Ruth Catlow, Furtherfield, Co-founder and Co-director.

Contributors: Dr Anat Elhalal, Digital Catapult; Ben Vickers, Co-founder unMonastery and Curator of Digital, Serpentine Galleries; Dr Catherine Mulligan, Research Fellow, Associate Director – Centre for Cryptocurrency Research, Imperial College; Elias Haase, Developer, Thinker, Beekeeper, Founder of B9lab; Irra Ariella Khi, Co-founder and CEO Vchain Technology; Jaime Sevilla, developer, researcher, GHAYA , #hackforgood; Jaya Klara Brekke, digital strategy, design, research and curating, Durham University; Kei Kreutler, Independent Researcher, Co-founder unMonastery; Pavlo Tanasyuk, CEO BlockVerify; Rhea Myers, artist, writer, hacker; Sam Davies, Lead Technologist – Creative Programmes, Digital Catapult; Vinay Gupta, resilience guru, Hexayurt

Pixelache Festival 2016, Helsinki, Finland. 22-25 September 2016

BLOCKCHAIN MEETUP, London Digital Catapult Centre, London, UK. 27 October 2016

INAUGURAL BRISBANE BLOCKCHAIN SYMPOSIUM 2016, Brisbane, Australia. 3 November 2016

The Blockchain – Change everything forever has been made as part of Furtherfield’s Art Data Money programme which seeks to build a commons for the arts in the network age. A book, Artists Re:Thinking The Blockchain in partnership with itinerant publisher and arts organisation Torque will be published in Spring 2017 with the prequel due out November 2016.

Furtherfield is an international hub for arts, technology and social change. Since 1997, Furtherfield has created online platforms and physical places for exhibitions, labs and debates where different types of people explore today’s important questions. Furtherfield is an Arts Council England ‘National Portfolio’ organisation with a Gallery and Lab in London’s Finsbury Park http://furtherfield.org/

Digital Catapult works with SMEs to help them grow and scale faster. It helps larger corporates in their digital transformation. It does this through programmes of collaboration and open innovation, by bringing academic leading edge expertise into the mix combined with the organisation’s own business and technological expertise. https://digital.catapult.org.uk

For any additional materials and interviews

Please contact Ruth Catlow

ruth.catlow@furtherfield.org

@furtherfield

A Furtherfield film made in collaboration with Digital Catapult, with support from Arts Council England and Southbank Centre.

![]()

![]()

Blockchain: Change everything forever

What is the Blockchain?

The Blockchain is the underpinning technology for Bitcoin digital currency, and is said to be at the same stage of development as the World Wide Web in the late 1980s. Its promoters claim that the global deployment of smart contracts via this new decentralised protocol will change everything forever.

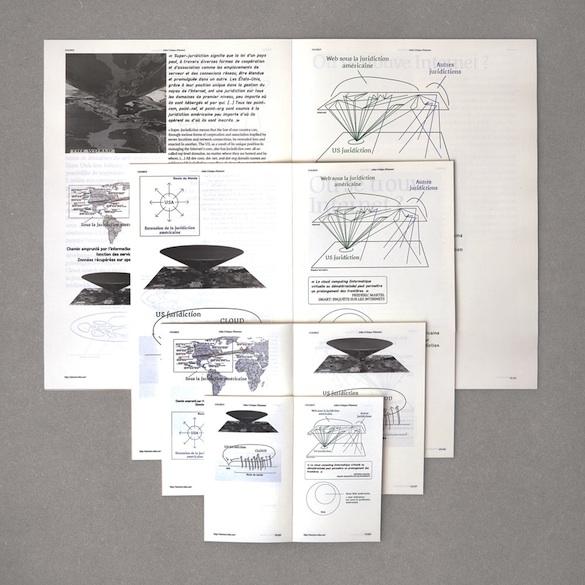

The Blockchain in Context

In 2008 Bitcoin, the first global digital currency was described in a white paper by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto. While the WWW facilitated a worldwide (economic and social) revolution in the global distribution of information, the Blockchain, would facilitate secure, decentralised record-keeping, exchange of digital assets and the mining and exchange of computationally secured value.

Since 2013 blockchains have become a focus for investment by world banks, FinTechs and corporations who predict a fourth industrial revolution of super-automation and hyperconnectivity. This is also accompanied by predictions from the World Economic Forum of increased global inequity.

In this version of the future, code replaces legislation. “Code becomes law”. Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs) route around systems of regulation and taxation via immutable smart contracts, globally deployed across the Blockchain.

The film The Blockchain: Change everything forever proposes that people from diverse disciplines and backgrounds should be involved to work out how Blockchain technologies can be shaped for more decentralised power, diverse needs and interests into the future.

*Jaya Klara Brekke, Digital strategy, design, research and curating, Durham University

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE (.pdf)

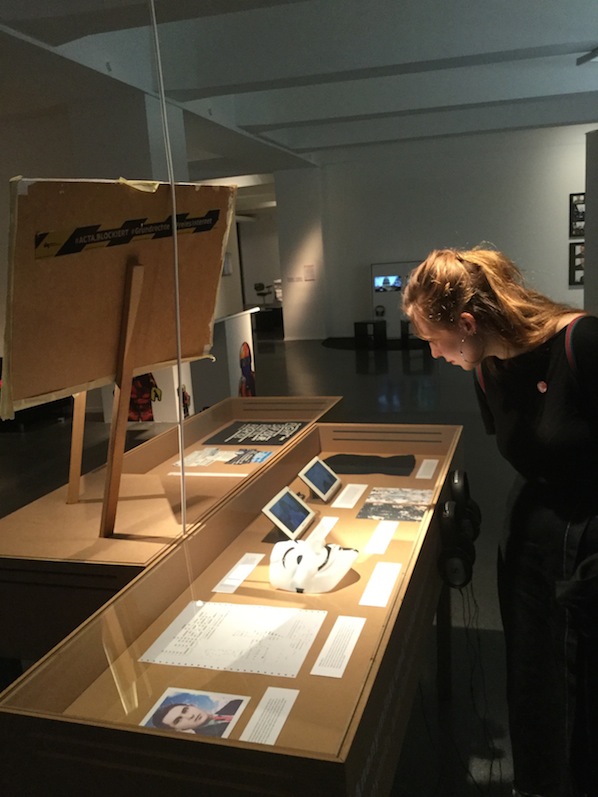

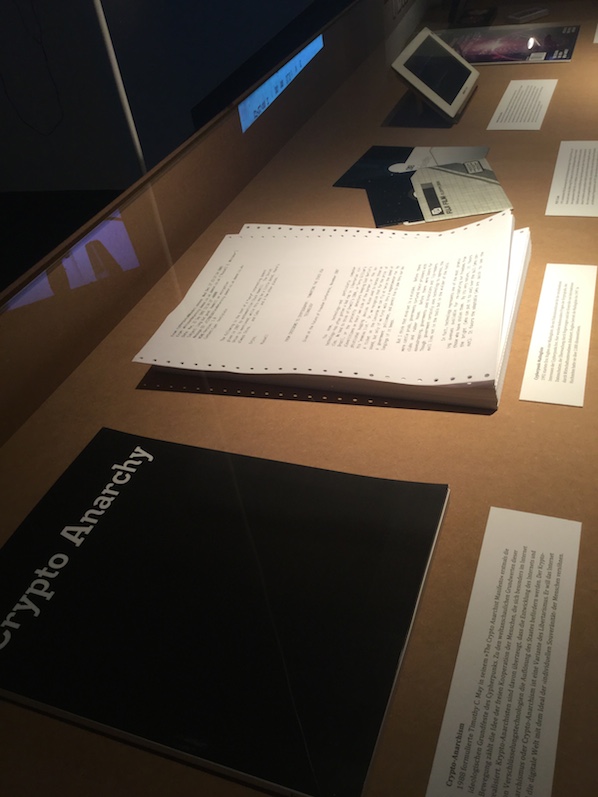

SEE IMAGES FROM ACCOMPANYING EVENTS

LISTEN to a recording of the conversation with John Conomos and Steven Ball at Furtherfield Gallery

Deep Water Web is a free exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery in London’s Finsbury Park, connecting opposite sides of the Earth to understand human impacts on the environment and the wider consequences for people living in both locations.

Artists Steven Ball (London, UK) and John Conomos (Sydney, Australia) have collaborated to present a multi-projection installation where London and Sydney are continuously connected across time zones. The exhibition is an immersive experience which the artists have termed a ‘hyperlandscape’ including real time streaming waterscapes and multiple local manifestations of global ecologies with their own sonic environments and narrated reflections.

Deep Water Web is a poetic meditation around contemporary and historical geopolitical contexts, underscored by London and Sydney’s situation around large bodies of tidal water in the forms of the River Thames and Sydney Harbour. These bodies of water bear material evidence of the local impact of global warming, such as rising tide levels caused by melting ice caps, leading to flooding, and increasingly extreme climate fluctuation. Both cities are also centres of neoliberal capitalism, inscribing the effects of privatisation, fiscal austerity and deregulation of markets across the planet.

Deep Water Web weaves rhetorical explication of postcolonial relationship, elaborating the precarious material forms of climate change, and post-labour late capitalist neoliberal urban developments of waterfronts of former Docklands, considered within the geological and rhetorical ecology of the Anthropocene.

The age of global warming and global neoliberal capitalism are figured here as critical rhetorical realms. These phenomena can be described as what Timothy Morton has called hyperobjects, objects so massively distributed in time and space as to transcend localisation. While they are impossible to comprehend at scale, hyperobjects exert a profound effect at a local level.

Deep Water Web will also become a catalyst for a workshops series at Furtherfield Commons, which will extend its themes through media based excavations. [dates and full details to be confirmed]

Both artists both have long standing moving image based practices and an interest in landscape and the representation of place. As a hyperlandscape this project suggests that questions of relationship to place, and the construction of landscape, can in the Anthropocene no longer be considered as simply pictorial representation or subjective experience, but is constituted from a range of critical, ethical, ecological, and political positions and concerns.

+ MORE INFO: http://deepwaterweb.net

Deep Water Web is supported by Arts Council England.

Exhibition Tour with artist Steven Ball

Tuesday 4 October 2016 – 5:30-6:15pm – Furtherfield Gallery

Revolutions and Complex Systems

Every Tuesday for 6 weeks

6:30 – 8:30pm at Furtherfield Commons – from 27 September 2016

BOOKING ESSENTIAL

A conversation with John Conomos and Steven Ball

2-3pm Saturday 29 October – Furtherfield Gallery

Booking is essential for this free event

Furtherfield in partnership with the antiuniversity and Radical Think Tank are proud to present this new 6-part course led by Graham Jones.

Aimed at people with an interest in social change, the course will apply concepts from complex systems theory to understanding revolutions and social movements. Sessions will involves a mix of speaker presentation and participatory discussions/activities, covering subjects such as ecology, network theory and new materialist philosophy.

Graham Jones is an activist based in East London, working with groups such as Radical Assembly, Radical Housing Network and Radical Think Tank. Booking Essential.

Steven Ball is an artist, writer and academic based in London, working with audio-visual media engaged with landscape and spatial representation, in local and global, social, political and post-colonial spheres. Since 2003 he has been Research Fellow at Central Saint Martins and was instrumental in developing the British Artists’ Film and Video Study Collection.

John Conomos is an artist, critic and writer based in Sydney, Australia. His books, essays and artworks are framed within four traditions of contemporary art: Anglo-American and Australian cultural studies, critical theory and post-structuralism. He is a New Media Fellow of the Australia Council for the Arts, and Honorary Professor at Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne.

Furtherfield was founded in 1997 by artists Marc Garrett and Ruth Catlow. Since then Furtherfield has created online and physical spaces and places for people to come together to address critical questions of art and technology on their own terms.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Visiting Information

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England

Several months ago I stayed in an offbeat Amsterdam hotel that brewed its own beer but refused to accept cash for it. Instead, they forced me to use the Visa payment card network to get my UK bank to transfer €4 to their Dutch bank via the elaborate international correspondent banking system.

I was there with civil liberties campaigner Ben Hayes. We were irritated by the anti-cash policy, something the hotel staff took for annoyance at the international payments charges we’d face. That wasn’t it, though. Our concern was intuitive about a potential future world in which we’d have to report our every economic move to a bank and the effect this could have on marginalised people.

‘Cashless society’ is a euphemism for the “ask-your-banks-for-permission-to-pay society”. Rather than an exchange occurring directly between the hotel and me, it takes the form of a “have your people talk to my people” affair. Various intermediaries message one another to arrange an exchange between our respective banks. That may be a convenient option, but in a cashless society, it would no longer be an option at all. You’d have no choice but to conform to the intermediaries’ automated bureaucracy, giving them a lot of power and a lot of data about the microtexture of your economic life.

Our concerns are unfashionable. Without any explicit declaration, the War on Cash has begun. Proponents of digital payment systems are riding upon technology-friendly times to proclaim the imminent Death of Cash. Sweden leads in the drive to reach this state, but the UK is edging that way too. London buses stopped accepting cash in 2014 but do accept MasterCard and Visa contactless payment cards.

Every cash transaction you make is one that payments intermediary like Visa takes no fee from, so it has an interest in making cash appear redundant, deviant and criminal. That’s why, in 2016, Visa Europe launched its “Cashfree and Proud” campaign to inform cardholders that “they can make a Visa contactless payment with confidence and feel liberated from the need to carry cash.”

The company’s press release declared the campaign “the latest step of Visa UK’s long-term strategy to make cash ‘peculiar’ by 2020.”

There you have it. An orchestrated strategy to make us feel weird about cash. Propaganda is a key weapon of war, and all sides present themselves as liberators. Visa comes across like a paternalistic commander when assuring us that we – like a baby taking first steps – will feel a sense of achievement at liberating ourselves from the burden of cash dependence. Visa technology offers freedom without dependence or dangers.

Other propagandists join Visa. In 2014 Penny for London arrived, an apparently altruistic group set up by the Mayor’s Fund for London and Barclaycard, using charity as a hook to switch people to contactless cards on the London Underground. PayPal plastered cities with billboards claiming that “new money doesn’t need a wallet”, and a video proclaiming: “New money isn’t paper, it’s progress”. Astroturfing campaigns like No Cash Day are backed by American Express, highlighting such anti-cash themes as the environmental impact of banknotes. Other tactics include pointing out that criminals use cash, that it fuels the shadow economy, that it’s unsafe, and facilitates tax evasion.

These arguments have notable shortcomings. Criminals use many things we keep – like cars – and fighting crime doesn’t prioritise maintaining other social goods like civil liberties. The ‘shadow economy’ is a derogatory term used by elites to describe the economic activities of people they neither understand nor care about. As for safety, having your wallet cash stolen pales compared to having your savings obliterated in a digital account hack. And if you care about tax justice, start with the mass corporate tax avoidance facilitated by the formal banking sector.

However, the peculiar feature of this war is that only one side is fighting. Very few media champions defend cash. It is like a taken-for-granted public utility, whereas digital payment platforms are run by private companies with an incentive to flood the media with their key messages. When they fight this war, their target is our cultural belief in cash and the belief that its provision should be a public right.

The UK government does not plan to maintain that right and is siding with the payments industry. Their position is summed up by economist Kenneth Rogoff in his new book The Curse of Cash. He argues that, apart from facilitating crime and tax evasion, cash hampers central banks from setting negative interest rates. In the absence of cash, everyone must keep their money in the form of digital bank deposits. During recessions, central banks could then use the banking system to deliberately corrode people’s deposits via negative charges, ‘inspiring’ them to spend rather than hoard.

The emergent consensus among economic and political elites is that this is the direction to go in, but to manufacture consent for this requires a drip-drip erosion of public resistance. Hearts and minds must be shown that the change represents inevitable and desirable progress.

Anyone defending cash in this context will be labelled as an anti-progress, reactionary, and nostalgic Luddite. That’s why we must not defend cash. Rather, we should focus on pointing out that the Death of Cash means the Rise of Something Else. We are fighting a broader battle to maintain alternatives to the growing digital panopticon that is emerging all around us.

To understand this conflict, we must step back. A monetary transaction involves exchanging specific goods or services for tokens giving access to general goods and services from others. The pub landlord hands me a beer at night if I transfer tokens that allow him to get cigarettes from a shopkeeper in the morning.

There are two ways to implement this, though.

The first is to give the tokens a physical form. In this scenario, ‘getting rich’ means accumulating those physical things and ‘making a payment’ means handing them over to someone else. They are bearer instruments, which means nobody keeps a record of who owns them. Rather, whoever holds them owns them. This is your wallet with notes in it. This is cash.

Alternatively, you can use a ledger. Someone sets up a database with spaces allotted to different people. This is then used to keep a record of who has tokens. These tokens have no physical form but are written into existence. They are ‘data objects’ and are ‘moved around’ by editing the record. The keeper of the ledger thus maintains an account of what money is attributable to you, ‘keeping score’ of it for you. In this system, ‘getting rich’ means accumulating a high score on your account. ‘Making a payment’ involves identifying yourself to the keeper of the ledger via a communications system and requesting that they edit your account and the account of whoever you are paying.

Does this sound familiar? It is your bank account.

Old banks used actual books to maintain these account ledgers, but modern banks use digital databases housed in huge data centres. You then interact with them via your internet banking portal, your phone app, or by going into a branch. This is not a minor part of the monetary system. Over 90 per cent of the UK’s money supply exists nowhere but on bank databases.

It is upon this underlying infrastructure that payment card companies like Visa build their operations. They deal with situations in which someone with one bank account finds themselves in a shop owned by someone else with another bank account. Rather than the pub landlord giving me his bank details for a manual transfer, my card sends messages through Visa’s network to automatically arrange the editing of our respective accounts.

Many fintech – financial technology – startups specialise in finding ways to augment, gamify or streamline elements of this underlying infrastructure. Thus, I might use a mobile phone fingerprint reader to authorise changes to the bank databases. – ‘disruption’ merely involves putting slicker clothes on the same old emperor.

The use of high-speed communications systems to rearrange binary code information about who has what money might be new, but ledger money is as old as any bearer form. The Rai stones of the island of Yap were huge and largely unmovable stones that, while seeming like physical tokens, were a form of ledger money. Rather than being physically moved – like cash would – a record of who owned the stones was kept in people’s heads, stored in their communal memory. If the owners wished to ‘transfer’ a stone to another, they ‘edited the ledger’ of who possessed the tokens by merely informing the community. Why physically roll the stone if you can get everyone to remember that it has ‘moved’ to somebody else? The main reason that we struggle to recognise this as a form of cashlessness is that the ledger is invisible and informal.

Cashless society, though, is presented as futuristic progress rather than past history, a fashionable motif of futurists, entrepreneurs and innovation gurus. Nevertheless, while there are real trends in behaviour and tastes to be spotted in society, there are also trends in behaviour and taste among trend-spotters. They are paid to fixate upon change and have the incentive to hype minor shifts into ‘end of history’ deaths, births and revolutions. Innovation communities are always at risk of losing touch within an echo chamber of buzzwords, amplifying one another’s speculations into concrete future certainties. These prediction factories always produce the same two unprovable sentences: “In the future we will… ” and “In the future, we will no longer… “. Thus, in the future, we will all use digital payments. In the future, we will no longer use cash.

This is the utopia presented by the growing digital payments industry, which wishes to turn the perpetual mirage of a cashless society into a self-fulfilling prophecy. Indeed, a key trick to promoting your interests is to speak of them as obvious inevitabilities already underway. It makes others feel silly for not recognising the apparently obvious change.

To create a trend, you should also present it as something others demand. A sentence like “All over the world, people are switching to digital payments” is not there to describe what other people want. It’s there to tell you what you should want by making you feel in sync with them. Here’s fintech investor Rich Ricci invoking the spectre of millennials, with their strange moral power to define the future. They are repulsed by the revolting physicality of cash and feel all warm towards fintech gadgets. But these are not, on the whole, real people. They are a weapon in the arsenal of marketing departments to make older people feel prehistoric. We’re not pushing this. We’re just responding to what the new generation demands.

And so we get Visa’s Cashfree and Proud campaign. If people really were ashamed of cash, they wouldn’t need ads to tell them. Visa must engineer that shame to teach you that what you want is the same as what they want. And if you don’t want it, just remember that a cashless society is inevitable. Don’t get left behind.

But this system will leave many behind. It is hardwired to include only those with access to a bank account, and bank accounts are hosted by profit-seeking corporations that operate at scale. They have no time for your individual idiosyncrasies. They cannot make a profit off anyone who cannot easily be categorised and modelled on a spreadsheet.

So, good luck if you find yourself with only sporadic appearances in the official books of state, if you are a rural migrant without a recorded birthdate, identifiable parents, or an ID number. Sorry if you lack markers of stability if you are a rogue traveller without a permanent address, phone number or email. Apologies if you have no status symbols or are an informal economy hustler with no assets and low, inconsistent income. Condolences if you have no official stamps of approval from gatekeeper bodies, like university certificates or records of employment at a formal company. Goodbye if you have a poor record of engagements with recognised institutions, like a criminal record or a record of missed payments.

This is no small problem. The World Bank estimates that there are two billion adults without bank accounts, and even those who do have them still often rely upon the informal flexibility of cash for everyday transactions. These are people bearing indelible markers of being incompatible with formal institutional space. They are often too unprofitable for banks to justify the expense of setting them up with accounts. This is the shadow economy, invisible to our systems.

The shadow economy is not just ‘poor’ people. It’s potentially anybody who hasn’t internalised the correct state-corporate narrative of normality and anyone seeking a lifestyle outside of the mainstream. The future presented by self-styled innovation gurus has no scope for flexible, unpredictable or invisible people. They represent analogue backwardness. The future is a world of endless consumer choice built upon an inescapable digital uniformity of automated rules, a matrix outside which you can neither exist nor think.

Back in Amsterdam, I hang out with Ancilla van de Leest of the Netherlands Pirate Party. She only visits establishments that accept cash, true to her political belief in individual privacy from prying eyes.

However, it would be wrong to assume that Ancilla’s primary concern involves surveillance by a Big Brother-style bogeyman. It’s true that your spending patterns reveal much about how you actually live, and the privacy implications of having these recorded in searchable database format are only starting to be uncovered. We know that targeted individual surveillance of payments occurs by the likes of the FBI and NSA, but routinised mass surveillance could become a norm. Imagine automatic flagging systems triggered by anyone engaging in a combination of transactions deemed subversive. Tax authorities are bound to be building systems to flag discrepancies between your spending patterns and your declared profits.

It’s also true that at London fintech gatherings, the exciting visions of a cashless society occasionally come with a disclaimer that we should think about the power granted to those who control the system. Not only can payment intermediaries see every time you buy access to a porn site, but they have the ability to censor your transactions, like Visa, PayPal and MasterCard attempting to choke WikiLeaksby refusing to process people’s donations. We could imagine some harsh sci-fi scenario in which a theocratic regime issues decrees to payment processors to block anyone buying books deemed sexually deviant. Such decrees could be automatically enforced via code, with subroutines remotely triggering smart locks to place the offending miscreant under house arrest while automatically deducting a fine from their account.

Such automated dystopias should ideally be avoided, so a dose of paranoia about digital payment systems is a healthy impulse, even if it might be unwarranted.

But that isn’t really the point. What’s more important to Ancilla and me is the looming sense of an external watcher that ‘assists’, ‘guides’ or ‘helps’ you in your life, tracking and logging your moves to influence you. The watcher is not a single entity. It’s a collective array being incrementally built in stages by startups and companies worldwide as we speak. We feel it seeping deeper into our lives, a mesh of connected devices, cookies and sensors. Whether we visualise it as the benevolent eyes of a parent or the menacing eyes of a tyrant doesn’t matter. The point is that the eyes have the potential to monitor you all the time.

The proclaimed Death of Cash is thus an episode in the broader drama that is the Death of Privacy, the death of the breathing room, and the death of informal, non-measured, unaccounted-for behaviour. Every action you take must forever be attached to your digital persona, dragging a data trail extending back to the day you were born. We face creating an entire generation of people who do not know what it feels like not to be monitored.

For many economists, the War on Cash will be resolved by their favourite mystical demigod, the market. This guiding force prevails when utility-maximising producers and consumers make rational choices with perfect information about their options and total freedom to choose whether or not to exercise them. If digital payment transaction costs are lower, then the cash will rightly die.

The pristine realm of market theory is unfit to assess the dynamics of this situation. Our sense of what constitutes a legitimate choice does not form in a vacuum. We are born into social power structures that tell us what normality is and shame us for not choosing ‘correctly’. You might be a rebel who challenges prevailing cultural norms, but those norms are conditioned by those with the greatest financial and media clout. At this moment, the blaring of propaganda extolling the short-term conveniences of digital payment is dulling our critical impulses to rearrange our cultural DNA. Who is thinking about the longer-term implications of building our lives around these systems and thereby locking ourselves into dependence upon them?

Unlike a battle fought using violence, hegemony is the assertion of power by getting people to believe in it, to see it as inevitable, unassailable and normal. Visa’s four-year plan is one such exercise, and once we’ve internalised it, we’ll choose to build their power. We’ll feel strangely comforted by the MasterCard billboard endorsed by the Mayor of London. We’ll find ourselves downloading ApplePay like a dazed child accepting a gift.

So, let’s prepare for the War on Cash. Remember, this is not about romanticising the £10 notes with the Queen. This is about maintaining alternatives to the stifling hygiene of the digital panopticon being constructed to serve the needs of profit-maximising, cost-minimising, customer-monitoring, control-seeking, and behaviour-predicting commercial bureaucrats. And fear not, the Germans are onside, along with the criminals, the homeless, the street-side buskers and an army of people whose lives will never get a five-star rating on a mainstream reputation scoring system. We will forge alliances with purveyors of non-bank alternative currency systems and maintain the option to use our payment cards. Because what we fight for is precisely that. The option.

When looking at the many artistic projects focused on how and why we use the internet, it’s easy to find yourself lost in a field which doesn’t show obvious, strong ties with what we normally know as “traditional art history”. This is due to historical and social reasons that emerged between the 80s, 90s and early 2000. These artists were at the vanguard of art culture and pushed at the edges of what art could be, whilst living in a post-punk and postmodernist era, and on tip of this, the arrival of the Internet in 94 changed everything. Many artists took on the challenge of what the Internet offered the world creatively, and explored it not merely as a marketing tool or a place to upload images and videos, but as a medium in its own right, inventing new technically informed, artistic tools and also building grass root led, networked art groups with new infrastructures as cultural platforms. Turning away from anything relating to the mainstream art world and what was seen as outmoded and tired traditions.

In the last decade, we’ve seen the expansion of the Internet and its use by younger generations where the medium is no longer something you exploit to change the culture, but more to integrate in traditional terms, canonical contexts.However, artist Jan Robert Leegte (born in 1973) is a very important figure to reflect upon, in order to understand this transition; while other artists of his generation were taking the internet for a non-hierarchical distributed system, he chose to explore it from a classical studies background that forged the cardinal points of his artistic research. He reflects an Internet art influenced practice which not only exists online but also in physical space. In fact, we can safely say he can be considered as one of the first Post-Internet artists. This makes him a pivotal figure in this historical segment and it’s under this light that one must visit the online exhibition On Digital Materiality (Carroll / Fletcher Onscreen, 3 August-12 September 2016). It’s a retrospective show presenting some of the most important and representative works of the Dutch artist, who wrote for the occasion an essay in which describes some of the most important aspects of his work.

Leegte says, the “materials I first used were basic HTML objects, buttons, scrollbars, frame borders, table borders, and also plain color fields and found images. I questioned what it was that rendered this practice similar to making installations rather than collages. At first it was the simulacrum of real world interactive elements (buttons, window frames, etc.). The operating system extended this haptic strategy with traditional paper-based forms, like check boxes, text fields, lists, etc, and, along with the form elements and the interactive document, led to an ecosystem of fake 3D, interactive objects.”

The work fluctuates between working on the surface and thinking in three dimensions. The same difference can be found with his use of Photoshop and HTML. If in the former case an image editing software operates directly on the final result, for the latter there is the need to know how to write code while at the same time imagine what the potential results will bring via its translation in the public space, the internet. In this sense, we do not hesitate to define Leegte as an artist who studies and uses the tools of the sculptor; he wonders how to place objects in the space, he feels the problem of contextualising a work in relation to a public and physical environment.

The perception of a substantial difference between surface and space is also proven with his interest in the basic elements of composing the digital interface (scrollbars, mouse pointers, etc). His research examines the artificial environment built by Microsoft and Apple designers. The colours and the shapes were designed to not be perceived as evident mediating agents between the user and the content – in this sense, it is interesting to note that Microsoft has often chosen a minimalist style (shades of grey, square shapes) while with Apple systems the style is usually more exuberant.

However, we should not look at the former as a less culturally relevant product. In the same way, we should not take the white cube exhibition space as a synonym of neutrality (unless we want to think that the whiteness and emptiness stay for an objectivity). This is an aspect that the artist does not seem to detect (in the text, he writes that he “preferred the aesthetics of the Windows classic interface design because of its minimalistic design – no rounded corners and ribbings like the OS 9 design, but simple beveled grey rectangles and a button object was merely a highlight and a shadow, nothing more”).

The artist reflected on how specific design elements may in some sense be preserved, as reflections and products of a particular aesthetic and cultural taste: “In Memory of New Materials Gone” (2014) is a work made by a print of the OS9 scrollbar placed in a transparent case in the same way you would do with an object no longer fashionable. This project and all the other works belonging to The Scrollbar Composition Series programmatically address the perception of virtually anonymous and transparent objects on the screen in a three-dimensional space. In a situation where their significance must be noticed; it’s the artist himself who begs to not see in this a disruptive act, an action that reveals the subtle ways in which they influence us. It is, however (but not “in opposition to”), a reflection on the artist’s activity; as we previously noted, these works are shown on the internet in the same manner in which they would be set up in a gallery space.

Perhaps, the highest point of the artist’s reflection on the differences you meet working on a surface or in three dimensions is The Photoshop Marquee Selection Series. “Random Selection in Random Image” (2012), in which a randomly generated selection marquee is shown within an image randomly obtained from the net. It is the most important work of this series because it opens three-dimensional gaps which have been created sculpturally in two-dimensional images – a dynamic that has echoes of “Scrollbar Composition” (2000), in which the Web browser’s monodimensional space is broken down and reassembled in many windows, many independent spaces sharing only the mathematical material they are made of.

The works featured in this exhibition are related to questions that go beyond the historical and cultural contingency in which they have been created. This makes many of them feel very much alive even 20 years after their creation (a novelty in digital art, I would say). This allows a healthy dialogue between different generations of artists to exist as common ground. It also engages art experts who want to be introduced to artistic issues linked to the internet. It is a dynamic that makes this exhibition a special opportunity for us all to relook at this so-called digital culture and its traditional and non-traditional art theories and its practice under a peculiar and exciting light.

On Digital Materiality – an Internet exhibition is online at Carroll / Fletcher Onscreen until 12 September 2016

Artist collective THEY ARE HERE invite you to play with and test software that allows wireless-enabled computers and mobile devices to directly form a spontaneous communication network independent of the internet.

Across a series of drop-in sessions facilitated by THEY ARE HERE, games and experiments will be trialled as part of the development process for their forthcoming exhibition at Furtherfield in October 2016.

These activities will take place online & offline around Finsbury Park.

Please bring a wi-fi enabled device to the workshop and if possible download the software Qaul.net in advance (qaul.net/software.html.)

No experience is necessary. Each session will be a discrete event, so you can attend as many or as few as you care to.

Join THEY ARE HERE at any of the following meetings at Furtherfield Commons, Finsbury Gate, Finsbury Park.

Session 1: 3pm Sunday 14th August 2016

Session 2: 3pm Sunday 28th August 2016

Session 3: 3pm Sunday 11th September 2016

Session 4: 3pm Saturday 24th September 2016

You must be aged 16 yrs +

Email contact(at)theyarehere.net for further information.

Date:NOW

Venue:HERE Links:http://www.crowdfunder.co.uk/artists-rethinking-the-blockchain?tk=208334da9b174c..

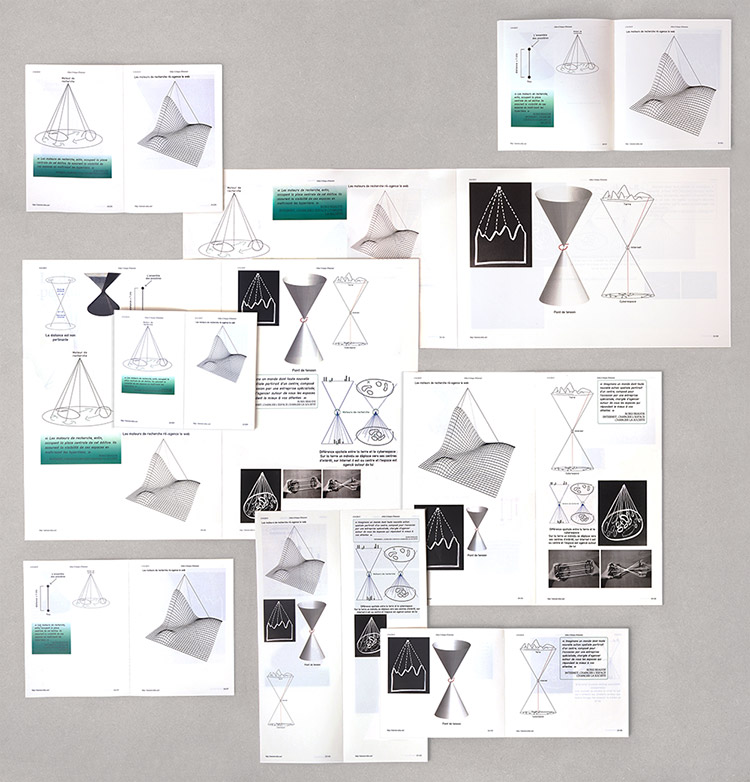

WE WANT your submissions to this landmark publication marking and augmenting the arrival of a new technology on the cultural landscape.

THE BLOCKCHAIN is widely heralded as the new internet – another dimension in the ever-faster ever-more-powerful interlocking of ideas, actions and values. [1]

It’s nothing more than a ledger distributed across a large array of machines. An apparatus that enables digital ownership and exchange without a central administering body. But from these simple premises, it has been credited with the potential to transform everything, from trade, to cultural production, to the way we’re governed.

Among other things, we are suspicious of cultural production being brought under the same regime as finance.

Even as we write, this “new dawn” for transactions is being re-imagined as the next sleep-cycle taking us deeper into the neoliberal dream of complete financialisation. In this dream, Finance and Technology quicken their demented mining of value tokens from phenomena, while the grammars of culture, family, nature, politics and spacetime itself evaporate into a flurry of question and exclamation marks in their wake.

“It’s going to change everything!” (The Guardian)

The permanence and irrevocable automation of blockchain systems wedded to the irrationality and sweep of techno-financial hybrids has led to forecasts ranging from ‘fully automated luxury communism’, to our ultimate cryptological enslavement to machines, or the collapse of time itself, as the feature of algorithms to make-happen overtakes the temporal concerns of flesh and earth.

Artists Re:thinking The Blockchain

This book is not a site for a ludic cynicism or uncritical valorisation, though it celebrates the energies of these excessive forms of thinking. We welcome the potentials for ever more nuanced democratic apparatus, and the decentralization of power from state-corporation cabals, while rejecting the notion that any single technology would automatically enact these ideological transformations. We seek also to register and amplify the leakages, weirdness and side-effects that this new technology inaugurates.

Imagined as a future-artefact of a time before the blockchain changed the world, and a protocol by which a community of thinkers can transform what that future might be, Artists Re:Thinking The Blockchain acts as a gathering and focusing of contemporary ideas surrounding this still largely mythical technology.

The book will include examples and discussions of current artistic projects making use of and illustrating the potentials of the blockchain, theorisation from some of the leading figures in the global blockchain conversation, and practical discussions which artists can use to guide their first steps towards this new technology.

We welcome submissions of

· book-based artworks which reflect on blockchain themes

· science fictions and theorisations, particularly in their hybrid form

· proposals for documentation of online and irl artworks

· poems, particularly based on the ‘new book’ and formal constraint txtblock [2]

The publication is a collaboration between Torque and Furtherfield, connecting Furtherfield’s Art Data Money project with Torque’s experimental publishing programme.

Alongside an illustrated print edition, the project includes a range of public-participation and debating sessions in towns and cities up and down the UK, and the first-ever book launch taking place on the blockchain itself.

DEADLINE FOR PROPOSALS 15th August

– up to 500-word abstract, description or sample of your proposed submission

– a short bio

– website link (optional)

mail to: mail@torquetorque.net

DEADLINE FOR FINAL SUBMISSIONS will be 1st October

torquetorque.net || furtherfield.org

https://www.facebook.com/torquebooks

#artblockbook

Contact: mail@torquetorque.net

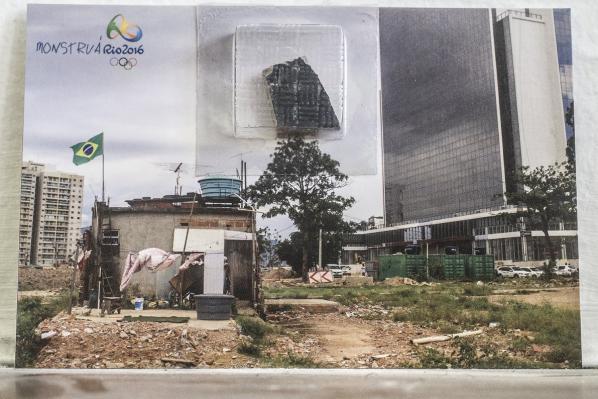

Featured image: ToolsForAction.net / Artúr van Balen and QueerSport.info / Zeljko Blace, ‘POP-UP RAINBOW’, 2014

Zeljko Blace is working in(-between) contemporary culture, media technologies and sport, cross-pollinating queer, media and social activism. He is one of the initiators and a co-curator of the project ‘contesting/contexting SPORT 2016.’

to reclaim the field with art and activism

exhibition and program in Berlin (08.07-28.08.2016)

at nGBK and KunstraumKreuzberg/Bethanien

http://ccSPORT.nGbK.de

www.facebook.com/cc.sport.2016/

www.twitter.com/CcSPORT2016

The exhibition and program contests the field of SPORT through critical art and activist practices. Coming from feminist and queer practices, the project aims to challenge discrimination and encourage emancipation. SPORT is contextualized from its declarative neutrality and autonomy, rendering diverse influences, but also experiences and conditions of SPORT realities visible.

Organized by the ccSPORT international working group of the nGbK including also: Caitlin D. Fisher, Carmen Grimm, Mikel Aristegui, Sarah Bornhost, Stuart Meyers, Imtiaz Ashraf, Andreea Carnu, with support from: Tom Weller, Alexa Vachon, Ilaa Tietz, Tabea Huth, Barbara Gruhl, Steffy Narancic, Tristan Deschamps, Coral Short, Gegen Berlin, Schwules Museum, and advisors: Alex Brahim, Jennifer Doyle, Philippe Liotard, Jules Boykoff, Stephane Bauer and †Frank Wagner.

BOSMA: The ‘contesting/contexting SPORT 2016’ exhibition and program shows a wide range of uncommon perspectives on sports, questioning cultural systems embedded in them we hardly ever think about. Why did you make this exhibition?

BLACE: In this ‘networked’ and globalized time we paradoxically live out a multiplicity of highly fragmented realities, niched in specialized interest groups, while ‘others’ feel they can not contribute or even relate to them. It felt like this to me in my work during the late/post 90s with tactical and net media activism/art – fully disconnected from queer politics and sports organizing for which I had an increasing interest. In general the field of sport has not been part of the lives of many intellectuals, activists and creatives. Many had bad (even traumatic) experiences with sport in childhood and adolescence, feeling alienated, or simply not recognizing it as a possible field to develop work in (unlike right-wing populists in tribal fan cultures). Simply put, the sport system has been taken for granted in its current form. Hence, my first curated sport exhibition title, paraphrased ‘sport hater’ Chomsky, in ‘Another SPORT is possible?!.’ (2012, Galerija NOVA, Zagreb, Croatia). My Berlin colleagues and ccSPORT co-founders Caitlin Fisher, Tom Weller and Carmen Grimm felt the same about the separation of sport from arts, activism and academic research. Together (with the support of exhibition spaces nGbK and Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien) we made plans to instigate and support intersections, cross-pollinate practices and perspectives between these fields through an exhibition, program and media work. We strongly felt the field of sport would never become self-critical and reform, nor would it engage with a wider audience beyond a given consumerist mode, if left to the managerial mentalities and the opportunism of its leaders. We need to reclaim the field of sport together to change it.

Is this the first ever exhibition criticizing the cultural and political dimensions of sports, and if not, how does your perspective relate or differ from earlier approaches?

I can not say with complete certainty what other group exhibitions on sport critique have taken place before. There have been many on a small scale, marginal in comparison to the huge exhibitions that ‘celebrate’ sports and are used as decor and entertainment accompanying sport spectacles (a notable exception is the seminal work ‘Electronic Café’ by K. Galloway & S. Rabinowitz at the 1984 LA Olympics, that actually provides space for interaction/discussion in between different city locations). There were also a few archival exhibitions looking at historical artifacts and documentation critically, as well as some that were experimental and playful (such as the Fluxus Olympiad, scripted as non-competitive multi-sports event) but these approaches were somewhat one-sided. We aspire to create a basis for both critical reflection and informed envisioning of possible developments, by looking at personal perspectives and artistic visions, next to grass-root alternatives and interventions.

The main threads in the exhibition seem to be gender, queerness and the connection between culture, commerce and rules in sport. Are these the main issues at hand?

Indeed our starting points were feminist and queer positions, but we were also very interested in the wider range of intersections and systemic issues within the field of sport that we could connect, rather than focusing on single-issues like homophobia or racism as is often done in mainstream sport campaigns. We decided very early on that the project would not be about identity politics, but rather about the multiplicities of axes of discrimination. There is a spectrum of emancipation efforts and practices that inspire us to think outside of gender norms, result-focused competitions, spectacle creating events and omnipresent ‘development’ narratives – which ignore for example that women had more access to certain sports historically in different geographies then they did in past 30 years of globalized neoliberalism.

augmented_profile from Diego Grandry on Vimeo..

How do you see the role of the media in the perception of sport?

Traditional broadcast media are the key stakeholder in the Olympics and similar sporting-spectacles. They have made the organizers of large sport events addicted to their huge broadcast contract revenues, but then inherently push for the spectacle of mega-events even further at the cost of other aspects. Newer sports that have evolved around this economy of attention have often sexed athletes (most visible with female beach volleyball) or at least contributed to enforcing gender stereotyping (like the feminization of soccer/football to the point that there are almost no short haired players at the Olympics). Instead of actively evolving with the progressive trends in sport, most broadcasters deepen the stereotypes; too often commenting on the marital status and appearance of female athletes, or referring to them as girls. Athletes from smaller countries, and sports that receive the least coverage are often looked down on, projecting neo-colonial relations on them (or hosts as in Brazil).

With internet networks and ‘social’ media the situation it is more complex as the interactive nature of media often allows for feedback and multiple standpoints in the same, or various foras. These media diversity brings to the surface and exposes critical minority voices and individuals who are able to argue against norms and question their necessities. For example, the tokenizing of muslim female athletes during these last Olympics received great reactions including historical facts about muslim women winning medals in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Also the outing of gay athletes by one reporter, was widely criticized online and the media hype reboot around Caster Semenya was compensated by internet and hybrid media (i.e. AJ+) publishing numerous expert articles and even giving voice to many (including former opponents critics converted to supporters as in case of Australian runner Madeleine Pape).

The connection between rules and cultural systems in sports is fascinating to me. You have worked as an organizer/curator in Multimedia Institute/MaMa before focusing on sport. What is your perspective on the rise of technological systems in the enforcement of rules, like for example drug testing or electronic goal-line and court line tracking?

Actually, the technological aspects of sport are the ones that still need to be addressed more specifically (technology centered single sport competitions exist since years, with The Cybathlon as their olympics premiere in Zurich, October 8th 2016). They not only re-enforce certain types of (measurable) norms, but also reduce the complexity into what appears to be arguable ‘logic’ and ‘common sense,’ while hiding other aspects (psychological and even aesthetic). Drug testing is an important measure of control, but is usually focused on the supra-performance of medal-winning athletes, rather than concerning itself with more generally applicable questions: what are the drugs, who has access to them and why. As long as the prevalent ‘production’ of results at all costs is dominating sports, the goal of ‘clean’ sports regardless of technological advancements in control will remain impossible. Gender policing at the Olympics has had a lengthy technological path, starting with visual and medical inspections, moving on to DNA and hormone testing and nowadays being fully questioned. Measuring and tracking technologies have the most interesting potential, not only for confirming line calls but for reshaping sports into allowing potentialities of variable norms and measuring based on generative fields/infrastructures. However, this kind of innovation is more likely to develop in the edges of eSports industry (that is pushed by novelty rather than burdened by traditions and conventions) and then maybe get normalized into traditional sport competitions once existing sport federations and regulatory bodies start losing young markets.

It was important for us to initiate conversations and collaborations that were not in place before, especially between those excluded from the mainstream sport system. We stirred up some interest from academic researchers for immediate follow-ups, but also informed some activists and artists of each other’s work. Ideally this could be developed further to elevate the critical and creative work in the field of sport and address issues in multifaceted ways.

We hope the exhibition and program enabled visitors to develop a more articulate position rather than just LOVING / HATING SPORTS, maybe supporting our platform — and ideally also inspired them to build personal or collective proactive relationships to sports. Maybe through practices of engagement against mega-spectacles and hyper-commercialization of sports, while supporting/partaking in grass-root sports or reforming the mainstream system.

Now we look forward to have the time for reflection after the intense work of materializing the exhibition and the extensive events program, as well as to see what future sport events could be interesting to contest and/or contextualize. One of the most important follow-ups is establishing an online space for sustainable communication, exchange and sharing information, know-how, methods, most likely using wikis, maps and media that came out of our research and workshops during the summer exhibition program.

This will be ncluding video of closing lecture by prof. Jennifer Doyle on art, sports and questioning the origins and need for the gender segregation in sports! More info will be appearing on our working website http://www.ccSPORT.link/

What is the relationship between state corruption and economic collapse in Greece?

Lina Theodorou, artist and creator of the board game ‘Pawnshop- Days of Mistrust’, talks with Furtherfield’s Ruth Catlow about Grexit, Brexit and crisis in Europe.

I met Lina Theodorou, the artist and creator of Pawnshop, in her apartment on a sunny Sunday morning in Berlin. It was just one week after the UK referendum resulted in a vote to leave the EU. I was in Berlin to take part in an event called Art, Money & Self Organization in Digital Capitalism, the first in a series of events called Arts and Commons, organised by Supermarkt.

Theodorou and I quickly got onto the topic of Brexit. We compared notes. She wondered if, like Greece, the UK government would choose to ignore the result of the referendum, fail to invoke Article 50, and stay in Europe after all. That possibility had not occurred to me. She talked about her memories surrounding the Grexit debate- the distress, the uncertainty, the shocking hatred and hostility expressed between family members and people previously considered friends. I had been deeply shaken by the upsurge of street-level racism on the streets of Britain.

Pawnshop, the artwork that is also a board game, was set up for play, laid out on a table in her studio. It is an inversion of Monopoly: the same square board, the pieces, the bank, the cards, the dice. However in this game the player starts the game with no money, only property – jewelery, a bouzouki, antique furniture, a flat- and pays a European tax of €1500 when they pass Go (if they get that far).

Players proceed around the board, according to the luck of the dice, along a path strewn with dilemmas. A second row of squares is used to keep track of the time spent dealing with the consequences of their choices- jail sentences, or hospitalizations for example. As they move around the board, they pick one of the cards, depending on their landing square, and must choose how they will respond to the given dilemmas.

Theodorou tells me that the game is based entirely in fact. For years she has collected newspaper stories in Greece. And here they are gathered in four categories of cards – Dilemma, Involvement, Debt and Luck- to encapsulate the experience of daily life, for everyone, in modern day Greece. ”If you are honest you lose” she says.

On her website are photos of engrossed players at Bozar, Center for fine arts, Brussels; at the exhibition TWISTING C(R)ASH; at Bâtiment d’Art Contemporain « Le Commun » in Geneva; and at the exhibition It’s Money Jim, but not as we know it, at Mario Mauroner Contemporary Art Vienna, and As Rights Go By, Museumsquartier, Vienna. She says it’s important that at the beginning players laugh… but because of ”synesthesia”, the longer they play, the more uncomfortable they become, they feel the ethical discomfort in their bodies.

Theodorou and I digress again, coming back to the Europe question. Because I’m in Berlin I think about Germany’s role. Germany at the heart of Europe is perhaps more part of the problem than they realise. The style of bureaucracy is molded to reflect the German mentality and their industrial system.This is coupled with a confidence in the correctness of the system – that Theodorou points out, is accompanied by the Northern European, Calvinist attitude – anyone who does not comply is wrong and must be punished. “But what is good for Germany is not necessarily what is good for Greece” she says. In Greece for many years the economy was made up of many small entrepreneurs, small businesses, shops, and a community focus” Why must we suddenly give this up in favour of big business. “Why do you have to destroy something that is healthy?”After the banking crisis in 2008 pawnshops started popping up on every street in every town in Greece.

Theodorou tells me that Pawnshop is the Greek reality board game.

“Your father is sick, do you pay his hospital bill?

Yes: pay €3000 and he lives for another 6 years,

No: unfortunately he dies, but you receive a life insurance pay out of €75,000”

Picking an ‘Involvement’ card means that that player’s decision will have consequences for other people too; Debt (is the biggest pile of cards).

Gentrification strategies have failed in Athens. Back in 2006 the rich Greeks, many of whom were also art collectors, started to organise the large scale art events, (in which of course the artists worked for free), but it didn’t take. Then in 2008 the banks collapsed, the economy became surreal, but somehow, Athens remained the same. Perhaps this because regeneration does not have the ever-rising bubble of property prices to support its economy. In Greece everyday people do not speculate on the housing market (as we do in the UK). Rather a house is something you keep for ever in the family.

Theodorou describes the real world Greek tax system as “insane”. It changes every 3 months, Even the accountants have difficulty keeping up with the laws. This alone forces many people into the black market. Then the web of bureaucracy protects the hierarchical status quo and people in higher positions hold onto their power by putting obstacles in the way of others.

The only way to win this game (on the board and IRL in Greece) is with good luck. Good luck is the only way to avoid ethical discomfort or financial ruin.

The Luck cards (also based on fact as reported by the newspapers) are hilarious. “A politician hits you with her car, but fortunately the accident is witnessed by the media – collect €2500”.

“Some rich ladies wish you a Merry Christmas and hand you €100”.

Apparently Athens newspapers have reported tales, for the last few years, in which “ladies” have distributed money to “the poor” from black windowed limousines.

Pawnshop is a polemic on corruption. Small corruption. Long standing, Greek-style, everyday corruption from which no-one can escape. The universal, forced collusion in corruption, and its corrupting effect on the spirit of Greek citizens and society, is set out in the game mechanics. The playful and social medium of the game means that the impact of contemporary Neoliberal politics on the Greek ‘everyman’ is made legible, feelable and discussable: unending, ethical traps; the impossibility of old-style moral political clarity; the flushing of righteous action, solidarity, resistance or even survival. Corruption all the way up and down.

I question Theodorou carefully, because I have long been suspicious of the narrative that says that corruption is the cause of Greece’s economic problems. But the corruption is a fact. While it is not necessarily the only or even the primary cause of its economic distress – which is very very real- the lack of trust in the state is debilitating and has a stagnating effect on the economy.

Pawnshop sits in an honourable tradition of artist’s activist games: to change mindsets and attitudes by actively implicating players in a reconstruction of values – see Mary Flanagan persuasive research about crticial play and the many attitude-hacking games coming out of her lab Titlfactor. Also Brenda Romero’s chilling Train game, Yoko Ono’s Play it by Trust. And for games that train for resistance and solidarity in games such as Escape from Woomera, Debord’s Game of War, and my own pacifist chess hack, Three Player Chess.

A look around Theodorous portfolios of works reveals a long practice that crosses agitprop, video, installations, and networked pieces.

The work all builds on close observations of contemporary political and social systems. Through graphical exuberance and humour these observations are rendered just (barely) bearable so that we are able to spend time with complex, difficult situations and suspend our certainties. And this is necessary and important. We need to face the complexities and ethical contradictions of contemporary politics. There’s no time to lose.

Before the referendum, I found myself uneasy about actually campaigning for “Remain” in spite of my desire for a pan-European peoples’ alliance. This was because I couldn’t ally myself with the dominating political arguments proposed by the Conservative party (and backed up by big-business and the establishment). I also didn’t want to participate in a binary campaign that stamped on the dignity of the layer of people in the UK who are already so disenfranchised by the effects of austerity cuts (and many years of other systemic injustices). This moment revealed for me, and for many others in the ‘social liberal’ layer, a chasm between my own values and experience and those who voted to ‘Leave’. And a desire to find a way to connect. PostBrexit the reality board game may be just the thing we need to help us come together and play our way through the effects, consequences and possibilities.

Furtherfield in partnership with the antiuniversity and Radical Think Tank are proud to present this new 6-part course.

Aimed at people with an interest in radical social change, the course will apply concepts from complex systems theory to understanding (and creating) revolutions and social movements.

The course is directed at a general rather than academic audience, although a desire for radical social change will be assumed.

6.30 – 8.30pm at Furtherfield Commons, inside the park near Finsbury Gate

Booking essential – Please book here

Tue 27 Sept – Introduction to Complex Systems

Tue 4 Oct – Smash the System – Creating and Harnessing chaos

Tue 11 Oct – Erode the System – Building the New World in the Shell of the Old

Tue 18 Oct – Escape the System – Bodily Affect and Surviving Oppression

Tue 25 Oct – Tame the System – Reforms without Reformism

Tue 1 Nov – Bringing it All Together – A Trajectory for Revolution

Sessions will involves a mix of speaker presentation and participatory discussions/activities, covering subjects such as ecology, network theory and new materialist philosophy.

Other familiar concepts will be re-examined through this framework, including the commons, chaos, structural oppression and reform.

The ultimate goal is for this knowledge to be put into practice to create more effective activism, to contribute to better understanding the workings of contemporary society and to help inspire projects for building future utopian alternatives.

Graham Jones is an activist based in East London, working with groups such as Radical Assembly, Radical Housing Network and Radical Think Tank.

For those unwaged or on low income the course is free (or donate what you can). Choose either the Free Ticket or Donation ticket in the links above.

For everyone else, individual sessions are £5 + booking fee. A prebooking of all 6 sessions is available for £25 + booking fee.

During my visit to Ars Electronica I was humoured by the excessive amount of ‘hello world’ creativity that is often produced when science and technology meet and exhibit interactive spectacles that make very little claim other than an enchanting proof of concept. What I thought would be an interesting media festival turned out to be a robotics road show. This tech road show attracts over 90,000 people from Europe and Asia to wonder at the latest innovations in robotics, VR, bio-hacking, 3d printing, drones and anything that glossed the pages of Wired magazine as the next big thing.

The alchemists of our time, or as I like to call them ‘Dumb wizards’, are continuing to design and exhibit technological achievements in self-fulfilling speculative words that have very little concern, consideration or critique with any relevant social issues of our time. Excluding the CyberArts exhibition (curated by Genoveva Rückert), which I thought was a top selection of some of the best media art works of the last years, Ars Electronica is predominantly occupied by interactive spectacles that neglect to examine the social & political impact of technology.

To overlook how smart phones, big data and network computing are changing privacy & security, or how cloud based services are transforming the labour market or how Silicon valley start up culture has convinced a sizeable amount of the population that for every problem, there is an app based solution. In the bazaar of innovative design and interactive art I struggled to identify any work (be it art, product, or concept/agency) that voiced or articulated concern or criticism with technology, politics or social change. The most provocative aspects would be the whimsical one liner that is planted to introduce some speculative design projects, showcasing some daft prototype with a splash page and a quote in large font to grab the attention of the viewer.

What is the gold of our time?

How do we build a social relationship with others?

Innovation: Where do we go from here?

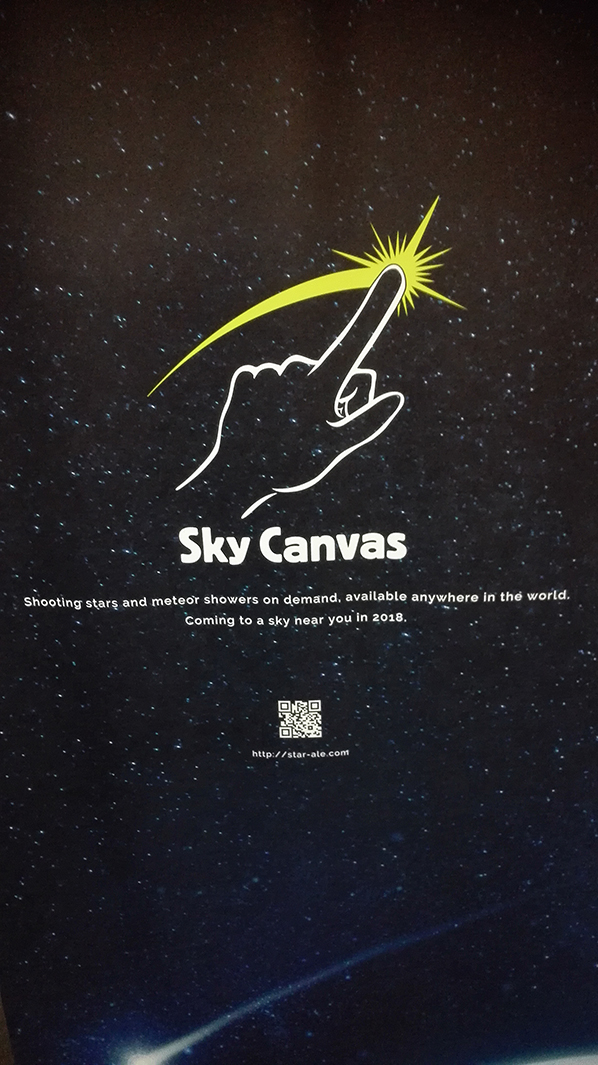

My favourite example of this was the disastrous ‘sky canvas: Shooting Stars. On demand’, an initiative to re-create the magic of a shooting star with satellite technology and glowing bits of plastic that can be shot into the night sky at the tap of a mobile app. The Alchemists of our time have fixed the magic of shooting stars. Great, thanks.

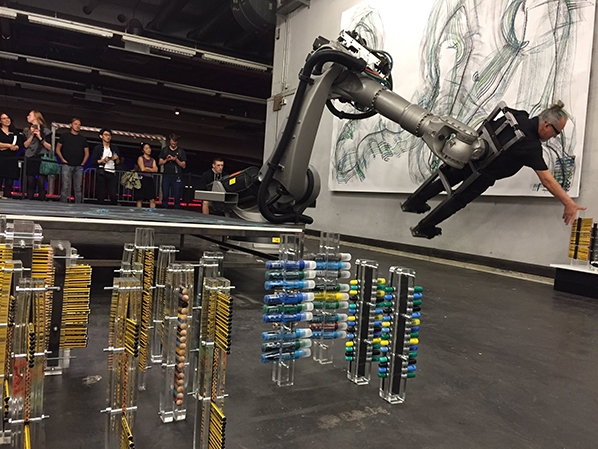

Much of the programme was better suited as light-hearted evening entertainment, drone racing, robot cooking, and endless drawing automaton. This robot, which I called ‘Human Pencil’ would throw around its inventor while he held 20 pencils and tried to make a drawing. Simultaneously inventive, pointless and entertaining; these robotic meme installations are better suited to robot fail video compilations on YouTube than to an art exhibition. The rejection of a critical consideration or a socio-political framing of the role of technology leads to what I call ‘enchantment art’, where the same devices used to execute mass killings in war zones become family friendly evenings entertainment.

Congratulations Dragan Ilić & team. Next performance at 10pm #Arselectronica16 #Artandscience @ArsElectronica pic.twitter.com/HgYXEctsYN

— GV Art (@GV_Art) September 8, 2016

So how has Ars Electronica, one of the longest standing and biggest media arts festivals in the world, found itself so far distanced from the political concerns surrounding technology? The first reason perhaps is that science does not bode well with critical theory. Many of the projects at Ars Electronica (again, excluding the CyberArts exhibition) feel like science museum artefacts that simply demonstrate technical (in)capability.

This attitude can be personified by the man I saw wearing a t-shirt stating “SCIENCE – It works, bitches”. Take for example this robotic arm reprinting Michelangelo sculptures which can only underline the immense technical potential of technology. Another possible reason perhaps that many of the works at Ars lacked social awareness is because they are produced by scientists & programmers in isolated laboratories. In this working methodology the viewer is rarely considered apart from in user tests, case studies and de-bugging. I found many maker lab types standing next to their large laser cutters avoiding eye contact while they printed out modular components and hoped for the next entrepreneur to walk past and slam down an investment fund. The lack of social awareness and engagement of issues surrounding our time have begun to impinge on the festival itself and an awareness campaign called #kissmyars is voicing concerns over the lack of female representation at the festival, particularly in the prix art prize which is awarded to men 9/10 times. The gender diversity in technology sector should no longer be ignored; this is one example of a socio-political issue not only overlooked at the festival program but also exacerbated by the organisation itself. I hope that the #KissMyArs campaign will not only rebalance the gender inequality at the event but also encourage the organisers to address other alarming realisations that operate within and around the application of technology in the social, political and economic sphere. Perhaps the Alchemists of our time should stop staring into the night sky planning the next life saving app and begin addressing the issues that applications can’t fix.

#KissMyArs

Leila Johnston was Rambert Dance company’s first ‘digital creative in residence’ from October 2015 – February 2016, having successfully applied to their residency programme, Sprint. The programme aims to enable Rambert to engage more deeply with the digital world, and is framed as experimental and light touch, with no expectations or goals in mind. One of the outputs of Leila’s residency – and the subject of this review – was a report ‘Hacking Rambert’, an incisive account of Leila’s time on Sprint, as well as a reflection on the nature of the creative residencies, dance and technology cultures.

Leila describes herself as an outspoken critic of current technology culture, resistant to its tendency for ‘digital evangelism’. The report belies her frustrations with technology culture – and indeed is a call to arms for rethinking what that culture needs to become. Her approach to the residency reflects this, emphasizing that its value came from bringing her critical perspectives about tech culture to bear, as much as from introducing dancers to ‘tools’ (though this played an important role too). She stresses how opportunities for growth and learning arose ‘through people (and sometimes tech)’ (my italics), and places human interaction and collaboration at the forefront, alongside, if not over and above, hardware and software. Dance is, she says, ‘about extraordinary relationships on every level – with yourself and then the little halo of space around you at all times, and then with greater and greater halos until it’s with everyone you meet.’ People are at the centre of her thinking and writing, and her residency was underpinned by questions such as ‘Is there a way to use technology to do justice to the human lifetimes that go into dance? Is there a way to dignify individuals, to invite confrontations with real people, to respect something other than the movement and acknowledge the part that individual experience plays in the construction of dance?’

Reflections on the cultures of the dance and technology worlds are also central to the report. Leila was struck by the relative openness and accountability of the dance world, which she saw as ‘a home that opens its doors to anyone that knocks’, in contrast to self-aggrandizing, solution-focused, often misogynistic digital world that is so well equipped to sell itself and its benefits. One of the observations that fascinated me most was about the different approaches to labour in the dance and digital worlds. For the former, hard work is a celebrated and central driver – dancers are ‘efficient’ because no work is seen as wasted. By contrast, the digital world wants to recover ‘free time’ by getting the hard stuff out of the way. While tech wants to make things easier – dance wants to make them harder – so that difficulties and limitation can be mastered and overcome.

The dominant tech world rhetoric that technology – coding especially – is ‘for everyone’ is thrown into relief by its absence in the dance world, where no one would expect ‘everyone’ to be a brilliant dancer, since this is something that requires a lifetime of grit and dedication as well as the right body and innate talent. Leila shows us that we can learn from the dancers’ dedication and commitment that ‘not everyone can do anything, and that there are pursuits that arise from the nuanced world of individual lifetimes and personal, emotional, motivation, the results of which don’t resolve into a formula’.

Although her emphasis was on criticality and personal relations, she drew on an impressive range of kit. She experimented with a thermal camera attached to her iPhone, which enabled her to explore a ‘dance of heat’. She observed that ‘the idea that dancers can be expressed as their invisible heat is strange, but absolutely real’.

The Point Cloud demo on the Kinect was of great interest to the dancers, for whom it allowed a new kind of 360-degree vision, useful since they are ‘always looking for their own back’. Leila experimented with a Raspberry Pi, using it for a range of experiments including connecting LED panels where she could display words and video. Again though, as well as the tool itself, the Pi gave rise to critical reflection: ‘Why aren’t we teaching dancers and choreographers creative technology skills for their work, rather than reinforcing a hierarchy of expertise by ‘advising’ them on creative direction?’ Emphasizing how accessible and readily available Pis, LED panels and other technologies now are, Leila makes the point that maker culture can be embedded in the dance world at little cost, but this won’t happen organically unless more awareness of each other’s culture is fostered.

Drawing from the residency blog hackingrambert.tumblr.com, Leila reflects on time, truth, and difficulty. She is resolute that time, patience and commitment are needed to make meaningful artistic contributions, and that artists undertaking short term residencies need to be realistic about what can be achieved. Rather than gunning for a finished product, ‘short projects should be about making – what it means to be a creative, and what we learned about the best way to do things in the context of the artificially short creation time.’ Unlike the tech world, quick fix and solutionism will not fare well on a creative residency.

Leila’s reflections on the notion of truth are intriguing; she feels that there is ‘nowhere to hide’ in dance, and draws a parallel between dancers’ bodies and the ‘technical authenticity’ of circuit boards and wires. These forms of hardware offer respite from the slick interfaces that are so characteristic of digital technologies. She notes: ‘I’m interested in the relationship between truth and performance; the unique way in which (dance) performances are honest, how our bodies give away the truth, how things represent what they are very transparently’. These explorations of truth provoke rich questions about authenticity, identity, ‘fidelity’ and representation. The notion of the stripped back body is a striking one, and when one observes a dancer in motion, with their muscles, sinews, bones, sweat, and humanity on display, there can be a powerful connection between the dancer and the audience. However, there is artifice at work in dance too – creating illusions with the body, emphasizing certain lines, creating the appearance of fluidity and ease when the body is being pushed to its physical limits. Can we draw an analogy here to the performance of identity online, where the blood, sweat, tears and humanity are often glossed over with ‘choreographed’ images that appear spontaneous and perfect? Or is the truth of dance and bodies precisely an antidote to this phenomenon? My caution here would be that dancers have identities as well as bodies, and are not immune to the pressures placed on them about their appearance and representation.

Leila argues that the creative tech community needs to work harder to understand dance, but that dance too ‘has much to gain by creatively educating itself in the available tech options’. Introducing dancers and the dance world to creative technologies can be fruitful, but should not be understood in solutionist terms. Technologists must take responsibility for the enormous power they have in society – it is up to them to ‘educate and differentiate’ between the potentially homogenous mass that is ‘technology. Finally, she makes a case for ‘contemporary creative technology’. The notion of the contemporary connotes the historical nature of a given art form and the contingencies of its evolution – conceptually, technically, physically, socio-politically. The relative nascence of technology, she suggests, leaves it unanchored, and subject to the intentions of ‘commercial forces’. She states ‘A contemporary creative technology could lay down the microphone of narrative and exist in the depths of the present. We could stop writing our own story in the cultural canon – indeed stop telling stories about what we’re doing at all – and focus on being demonstrable and accountable.’

There are moments when Leila seems to idealize the dance world as relatively problem-free, without acknowledging its potential problems – not least the subjection of bodies to punishing regimes and the mental and physical problems this can give rise to, and issues of social inequality, accessibility and exclusivity that come with all creative industries. However, there is clearly a lot the technology world can learn from the culture of dance. Perhaps the tech sector should start having dancers in residence…

Basic Income is often promoted as an idea that will solve inequality and make people less dependent on capitalist employment. However, it will instead aggravate inequality and reduce social programs that benefit the majority of people.

At its Winnipeg 2016 Biennial Convention, the Canadian Liberal Party passed a resolution in support of “Basic Income.” The resolution, called “Poverty Reduction: Minimum Income,” contains the following rationale: “The ever growing gap between the wealthy and the poor in Canada will lead to social unrest, increased crime rates and violence… Savings in health, justice, education and social welfare as well as the building of self-reliant, taxpaying citizens more than offset the investment.”

The reason many people on the left are excited about proposals such as universal basic income is that they acknowledges economic inequality and its social consequences. However, a closer look at how UBI is expected to work reveals that it is intended to provide political cover for the elimination of social programs and the privatization of social services. The Liberal Party’s resolution is no exception. Calling for “Savings in health, justice, education and social welfare as well as the building of self-reliant, taxpaying citizen,” clearly means social cuts and privatization.