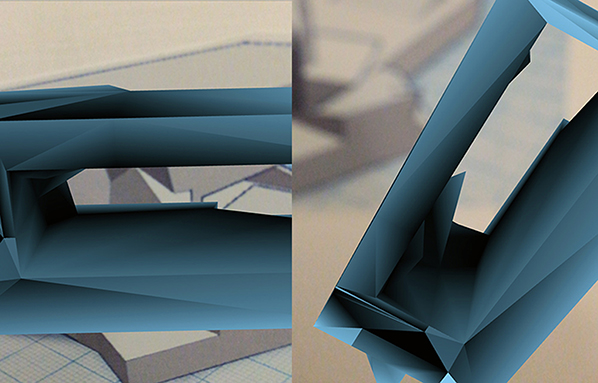

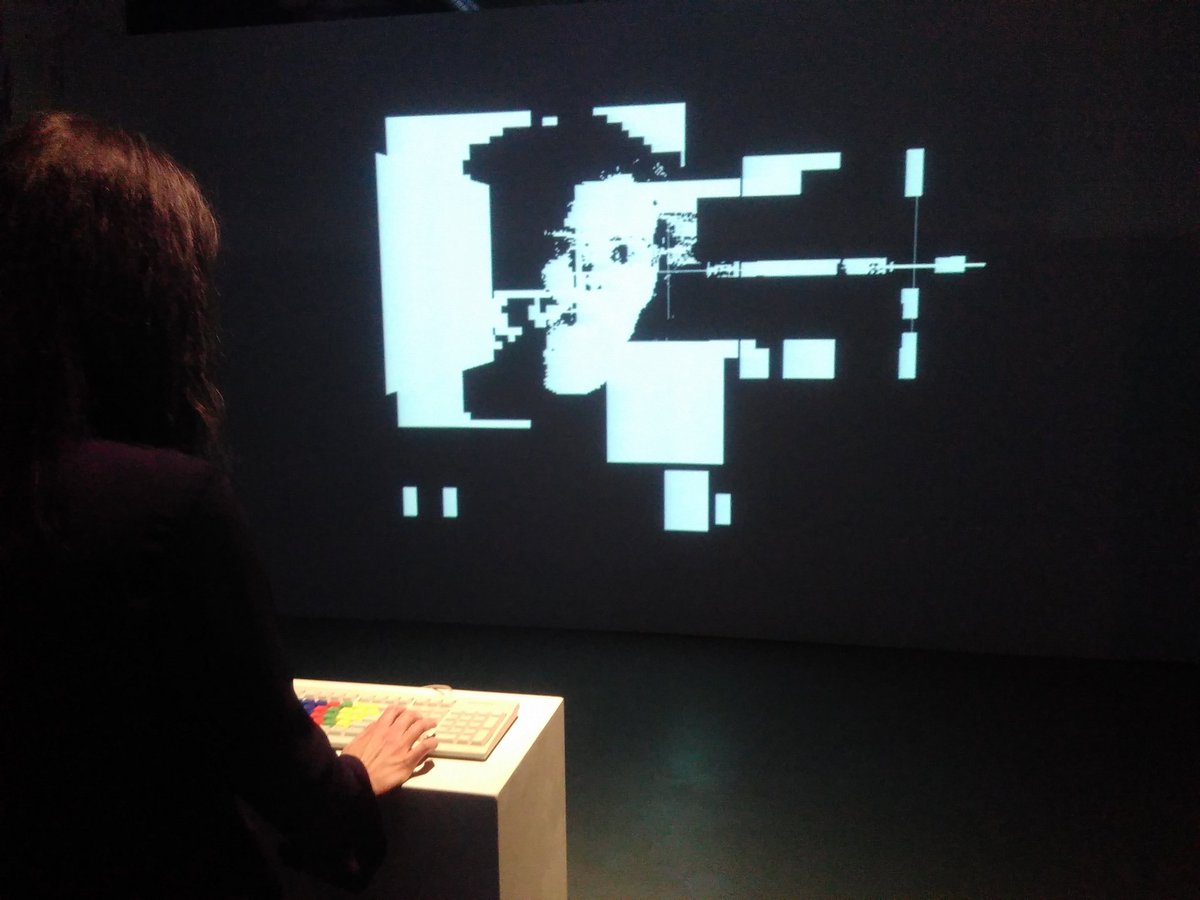

Featured Image: Obscurity (2016), Paolo Cirio

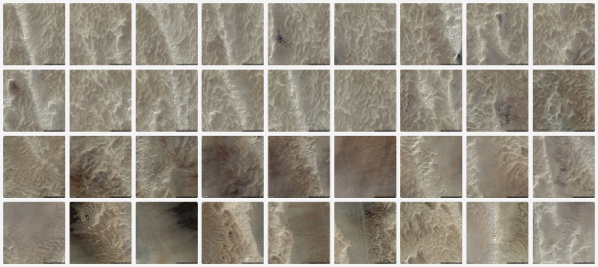

Obscurity, the latest project of Paolo Cirio, targets american mugshot websites. Mugshots are one of the utmost paradigms of the inexorable logic of today’s online economy and its controversial ethics; they collect and expose photos of people who have been arrested in the U.S., irrespective of the type of offence, and they profit by placing reputation management ads or by charging a removal fee. The owners of these websites are often anonymous or based offshore. As part of his project, Cirio cloned some the most known mugshots, scrambled the data profiles of the listed individuals and obfuscated their identities. In addition, he programmed the algorithm so that it boosts the ranking of the cloned websites in order to interfere with the activity of the original ones and to therefore sabotage their function. Mugshots can have a decisive role in someone’s life, reinforcing a new form of social stigmatisation defined by search engines results. When visiting the mugshot duplicates, users are invited to decide whether the listed profiles should be kept or removed. Obscurity brings to the foreground critical and complicated issues around today’s privacy and transparency, discussing the current legislative system in the U.S. in comparison to Europe and other parts of the world.

I talked with Paolo Cirio about the challenges and difficulties behind his -once again- daring act and artistic work.

DD: Mugshot websites are based on the exploitation of the anxiety and fear of people who have been arrested in the U.S. It addresses a new form of monetisation that takes reputation management to its extreme. Could you tell us how ‘big’ is the issue of mugshots in the U.S. and what made you develop a project about it?

PC: There are probably over 50 million mugshots on the Internet, and perhaps more, considering that every year in the U.S., city and county jails admit between 11 and 13 million people, an average that has been steadily increasing in the last twenty years. I personally met people that had their mugshots published on those websites and had to pay a removal fee. I would say that this is a very common issue for non-white and low-income Americans, who are the majority, although they’re often neglected by public attention.

I was surprised that this issue was being ignored and not addressed seriously. I couldn’t find any privacy organization in the U.S. focusing on this issue or making a major case for the Right to Be Forgotten in the U.S.

In particular, the several contradictions and complexities of the situation offered me an exciting subject to intervening practically and conceptually. It was the saddest and most delicate material I had ever worked with. However, it was important to address how the flow of information today can impact lives so directly and how art can do something with that. In most of my artworks, I highlight our information society’s legal, economic, and social implications. These fields are all tightly interconnected in this work: the economic value of sensitive information with the personal interest and the legal system with the public democratic interest. I would say that this work is about society as a whole.

DD: At the heart of your project lies an obfuscation algorithm. Obfuscation is a strategy against datafication which has been very much discussed in the last few years. How is it used as part of your project, and why?

PC: The obfuscation of information became quite a sophisticated operation in this work. The huge dataset I assembled with such delicate material could not be wasted or mishandled. That’s why I decided to apply different layers of obfuscation to protect the privacy of the individuals and, at the same time, keep the data accurate.

The algorithm shuffles first and last names and mugshots based on common gender, race, age, and location, making their obfuscated identities similar to the original ones. Meanwhile, for the profile of the person arrested, all the data concerning the arrest is maintained accurately. The individual records provide the social context of the arrest for public scrutiny without exposing the individual. For instance, you can still count how many people of colour have been arrested in a specific county, but it would be hard to identify individuals.

I believe there is a need to learn how to handle sensitive information very carefully, case by case, and to deal with complexity to provide simplicity and not make it more overwhelming. The notion of privacy and transparency can’t be polarized between fears and utopias of big data.

In past years, I’ve been working on several projects concerning the circulation, appropriation and exposure of sensitive information over the Internet. In particular, I made artwork by recontextualizing photos of individuals on Facebook, Twitter, Google Street View, and other online platforms. These provocative works were meant as a warning regarding social media companies’ privacy policies and the danger of losing control over one’s pictures posted online. However, I never let search engines index this personal information or expose their names in all cases.

I believe in a need for an ecology of information. I see information as water; it should be safe, accessible, and clear for everyone’s sake. Any form of pollution could damage an entire ecosystem. Therefore, for me, obfuscating a particular flow of information is more of a technique to clean a toxic spill into a reserve of data that can be essential for a democratic society. Like when it allows public scrutiny over law enforcement agencies. Imagine some operations trying to obfuscate open data or inject fake stories into WikiLeaks. Wouldn’t it be as shameful an act as polluting spring water? In the future, it’ll be even more important to fight to keep the oceans of data clean, safe, and navigable.

This is another reason why obfuscation is something that should be done carefully.

DD: As part of your artistic practice, you often deploy participatory formats for the audience. Lately, though, you seem to be more and more interested in having the audience take a stance and become more involved in the decision-making or problem-solving process. What made you turn in this direction for this particular project? How does user participation become an indispensable part of the work?

PC: I follow the natural evolution of the Internet. I started research works involving millions of individuals in early 2009 when I noticed how quickly Facebook was becoming popular, thus offering a huge audience for my work, which became the actual material of it. Many apps let us manage our life and everything around it by tapping buttons on screens. At this point, everyone makes decisions on the Internet that affects someone else as they produce changes in concrete reality. The Internet is the best tool and environment for decision-making and problem-solving today. Therefore, the basic sense of civility we developed in the physical space should be learned in the online environment.

Yet, with the Internet, we are in the Paleolithic Period, almost naked in public, and learning about what we can do with primitive tools while not knowing how to live together peacefully and with respect for one another.

In this project, I examine online judgment. The rating that is taken to its extreme is online shaming. I’m interested in the ethics and aesthetics around it concerning algorithms and individuals who rate and score others.

With the participatory model proposed, everyone can decide to keep or remove an individual criminal record. I like to invent systems of participation, as they can be structured to channel flows of social dynamics for creative forms of society.

It is a preposition, “what if” everyone could judge people online accused of a crime like an open jury and give a verdict on whether they should be forgiven or punished by society. The project also questions the necessary information to make a fair judgment. I’d not be surprised if tribunals were to one day have this type of online public forum.

DD: Through your artwork, you are underlining the urge for the ‘Right to Remove.’ How does this differ from what we know in Europe as the ‘Right to be Forgotten?

PC: The Right to Be Forgotten has been largely contested in both the U.S. and the E.U. for its potential to censure, for its lack of transparency on the decision process, and because it makes search engines the only jury on what the public can find online. Yet, in the E.U., although not perfect, the law offers all European citizens some rights since a few years ago.

In the U.S., it’s more complicated, mainly because the First Amendment protecting the Freedom of Expression is supposed to win over any attempt to curb the publishing of public information and opinions. This is the case made to oppose the Right to Be Forgotten in the U.S., and the one pushed forward by many organizations, like those dedicated to lobbying for freedom of the press or governmental transparency laws, that still defend the publishing of mugshots.

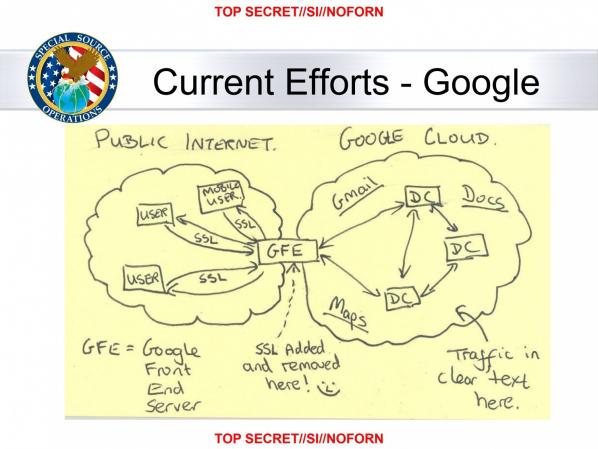

The federal system in the U.S. further complicates this situation. Every state in the U.S. has been approaching issues concerning the online publication of mugshots, revenge porn, and even information on minors differently. In many states, these are still totally unregulated. Talking about the legal and justice system in the U.S. is very hopeless when considering that Google is the company that has spent the most money ever in lobbying the U.S. Congress. Google has always been strongly opposed to the Right to Be Forgotten in both the E.U. and the U.S. They always mention censorship, technical impracticality, and not being accountable for their search results.

However, with copyright and trademark claims, search engine companies can manage huge quantities of takedown requests. Why would they not be able to offer the same for personal information complaints? Ownership rights should not be more important than human rights.

With this project, I made a proposal for a basic list of very specific categories of personal information that ordinary people in the U.S. should be able to remove from search results. With the Right to Remove, I wanted to create a straightforward campaign to inspire a workable form of this right for the U.S. To do so, I researched this legal subject on the campaign’s website. I launched a petition that I plan to have signed by a few key privacy lawyers, academics, and organizations in the U.S. in the coming months, to be finally presented as an open letter to search engine companies and the FTC. However, for me, this proposal is part of the conceptual artwork. I don’t have hopes of being able to effect change as that would require a huge press effort, and so far, I haven’t received any funding or institutional support for this project.

DD: Are you also interested in the aesthetic qualities of obfuscation? Are you planning a physical installation of the artwork?

For me, the aesthetic qualities are mainly conceptual and strategic.

In most of my work, there is also a documentative function, in this case, it’s about bringing attention to mass incarceration and the lack of a privacy policy in the U.S. Because of the research presenting facts with videos, texts, data, and images, the audience can enjoy the artwork as an interactive documentary. I don’t find data visualization an interesting mode of presentation. Still, I did use the database to find gross human rights violations like the mugshots of ten-year-old kids or seniors over ninety-five.

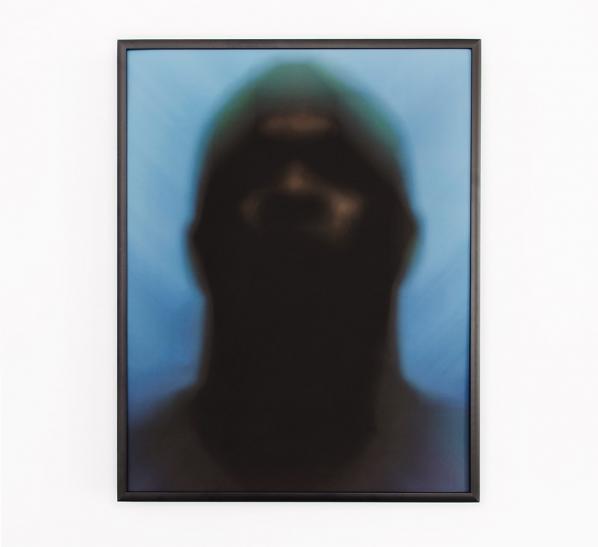

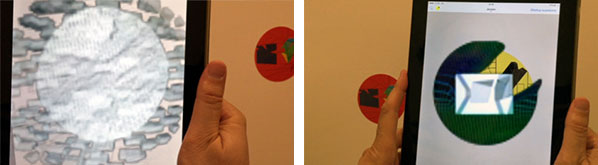

I later realised that the algorithm that manipulates the mugshots created very interesting visual effects. It seems worth it to make prints of them for the installation. The darkness and the blueness recall the obfuscation of data in a visual form. They look scarier or more inoffensive when the colours hide their appearance. This reminds the audience of how difficult it can be to judge someone without having clear and complete information about the individual. In the installation, I would have a paper shredder that destroys mugshots as they are printed based on the audience’s browsing and interactions on the mugshot websites.

With this project, I also suggest a form of Internet social art practice. It’s inspired by many artists I admire that have been doing social practice work in the U.S. In this case, I’m suggesting that artists can make Internet artworks that have a social function for a problematic group of people, communities and the environment.

For instance, with this project, I started to receive an increasing number of emails from people asking me to remove their records because they thought I was behind the real mugshot websites. They are automatically redirected to sign the petition.

What makes an aesthetic difference for me is when artworks live outside the art world and artistic modes of representation. My audience is not really the minority attending the spectacle of art. Instead, it’s real people with real lives and concerns. Even when the artwork is not exhibited, reviewed, or sold, it’s still online, informing, producing reactions, and possibly changing.

project website: https://obscurity.online

cloned websites:

http://Jailbase.us

http://Usinq.us

http://Mug-Shots.us

http://JustMugshots.us

http://MugshotsOnline.us

http://BustedMugshots.us

What does the comic book heroine Wonder Woman have to do with the lie detector? How is the Situationists’ dérive connected to Google Map’s realtime recordings of our patterns of movement? Do we live in Borges’ story “On Exactitude in Science” where the art of cartography became so perfect that the maps of the land are as big as the land itself? These are the topics of the Nervous Systems exhibition. Questions that are pertinent to the state of the world we are in at this moment.

The motto “Quantified life and the social question” sets the frame. Science started out as a the quantification of the world outside of us, but from the 19th century onwards moved towards observing and quantifying human behaviour. What are the consequences of our daily life being more and more controlled by algorithms? How does it change our behaviour if we are caught up in a feedback loop about what we are doing and how it relates to what others are doing? Does this contributed to more pressure towards a normalized behaviour?

These are just some of the questions that come to mind wandering around the densely packed space. You have to bring enough time when you visit “Nervous systems” – it is easy to spend the whole day watching the video works and reading the text panels.

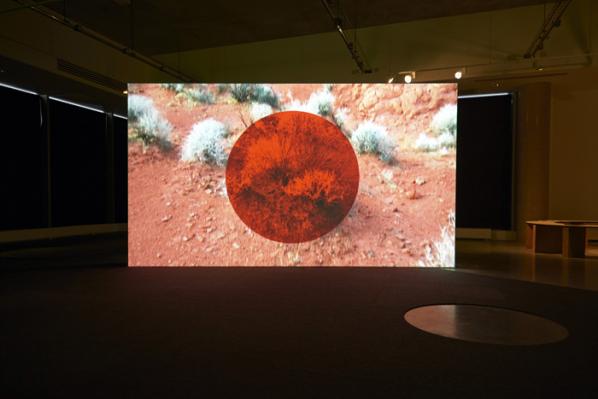

There are three distinct parts: the Grid, Triangulation and the White Room. Each treats these questions from a different perspective. The Grid is the art part of the show and features younger artists like Melanie Gilligan with her video series “The Commons Sense” where she imagines a world where people can directly experience other people’s feelings. In the beginning this “patch” allows people to grow closer together, increasing empathy and togetherness, but soon it becomes just another tool for surveillance and optimizing of work flows in the capitalist economy – an uncanny metaphor of the internet.

The Swiss art collective !Mediengruppe Bitnik rebuilt Julian Assange’s room in the Ecuadorian Embassy – including a treadmill, a Whiskey bottle, Science Fiction novels, mobile phone collection and server infrastructure – all in a few square metres. The installation illustrates the truism that history is made by real people who eat and drink and have bodies that are existing outside of their role they are known for. Which is exactly why Assange is confined since 2012 without being convicted by a regular court.

The NSA surveillance scandal does not play a major part in the exhibition as the curators – Stephanie Hankey and Marek Tuszynski from the Tactical Technology Collective and Anselm Franke, head of the HKW’s Department for Visual Arts and Film – rather concentrate on the evolution of methods of quantification. For this reason we are not only seeing younger artists who directly deal with data and its implications but go back to conceptual art and performance in the 1970s and earlier.

The performance artist Vito Acconci is shown with his work “Theme Song” from 1973 and evokes the Instagram and Snapchat culture of today by building intimate space where he pretends to secrets with the audience. Today he could be one of the Youtube ASMR stars whispering nonsense in order to trigger a unproven neural reaction.

Harun Farocki’s film “How to live in the FRG” on the other hand shows how society already then used strategies of optimization in order to train the human material for the capitalist risk society.

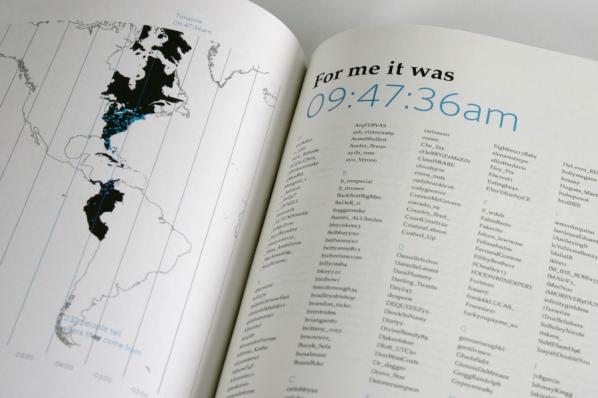

Triangulation is the method to determine the location of a point in space by measuring the angles from two other points instead of directly measuring the distance. As a method it goes back to antiquity. In the exhibition the Triangulation stations give a theoretical and cultural background to the notion of a quantified understanding of the world. Here the exhibition give a rich historical background mixing stories about the UK mass observation project where volunteers made detailed notes about the dancing hall etiquette with analyses of mapping histories and work optimization.

The triangulations in the exhibiton are written by eminent scholars, activists and philosophers. The legal researcher Laurence Liang writes about the re-emerging forensic techniques like polygraphs and brain mappings that have their roots in the positivism of the nineteenth century. Other triangulations are about Smart Design (Orit Halpern), algorithms, patterns and anomalies (Matteo Pasquinelli) and quantification and the social question where Avery F. Gordon together with curator Anselm Franke speaks about the connection of governance, industrial capitalism and quantification.

“Today’s agitated state apparatuses and overreaching institutions act according to the fantasy that given sufficient information, threats, disasters, and disruptions can be predicted and controlled; economies can be managed; and profit margins can be elevated,” the curators say in their statement. We see this believe everywhere – the state, the financial sector, in the drive towards self-optimization. A lot of the underlying assumptions can be traced back to the 19th century – the believe that if we have enough information we can control everything.

Like Pierre Laplace and his demon we believe that if we know more we can determine more. The problem is that knowing is only possible through a specific lens and context so that we become caught up in a feedback loop that only confirms what we already know to begin of. Most notably this can be seen in the concept of predictive policing which is also present in the triangulation part of the exhibition. Algorithms only catch patterns that are pre-determined by the people who program them.

Going through The Grid of the art works (the exhibition architecture by Kris Kimpe masterfully manifests a rectangular gridlike structure in the exhibition space) and reading the Triangulation stations the visitor is left a bit bereft. Is there still hope? One feels like at the end of George Orwell’s 1984 – the main character is broken and Big Brother’s reign unchallenged. This is where the White Room comes in. Here the visitors can be active. The Tactical Technology Collective provides a workshop programme where one can learn about how to secure one’s digital devices, how to avoid being tracked – on the web or by smartphone, what the alternatives are to corporate data collectors like Facebook or Google.

In the end the nature of internet is twofold and conflicting: on the one hand it allows for unprecedented observation and monitoring, on the other it is a tool for resistance connecting people who were separated by space and time. It is not yet clear if this is enough or if (like the radio and other technological media before) it will be co-opted by the one’s in power.

This leads me to one problem of an otherwise very necessary and inspiring show: For all its social justice impetus that narrative that is presented here is very androcentric – there are few if any feminist, queer or post-colonial perspectives in the exhibition. If they are presented then from the outside. This is not a theoretical objection as women, people of colour and other minorities (who are actually majorities) are especially vulnerable to the kind of hegemonic enclosures on the basis of data and algorithms. In a talk in the supporting programme the feminist philosopher Ewa Majewska gave some pointers towards a feminist critique of quantification: the policing of women’s reproductive abilities, affective labour or privacy as a political tool. More of this in the exhibition itself would have gone a long way.

The exhibition is accompanied by an interesting and ambitious lecture programme. The finissage day, May 8, is bound to be especially interesting. Franco Berardi, Laboria Cuboniks, Evgeny Morozov, Ana Teixeira Pinto and Seb Franklin are invited to think further about digitial life, autonomy, governance and algorithms.

Nervous Systems. Quantified Life and the Social Question

March 11 – May 9, 2016

Haus der Kulturen der Welt Berlin

Opening hours and information about the lecture programme on the website.

Featured Image: Smoke Signals at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation, Manchester

Red floodlights illuminate the silhouette of a grand piano standing in the centre of a darkened room. As musician and composer Jonathan Hering begins to strike the keys of the late Anthony Burgess’ piano, a hidden bank of machines cough a sequence of smoke rings into the air, which catch in the red light above. The room fills with a ghostly red mist, all but obscuring the source of the beautiful music. The irregular pattern of smoke puffs suggest it’s some sort of message or code. In fact, it’s a sequence based on email data from seven arts organisations, put through a Polybius cipher.

Smoke Signals places digital communication in context, as simply the latest in a line of our approaches to long-distance forms of communication,” explains co-creator Ed Carter. “I was very interested in the way that as the smoke, or ‘data’, filled the room it became more and more dense. At the beginning, you can decipher it if you understood the code, but eventually it becomes more of a fog – which is a nice analogy for the way data works on a big scale.”

This performance of Smoke Signals at Manchester’s International Anthony Burgess Foundation captures much of what FutureEverything festival is all about: looking simultaneously backward and forward through technology, fusing the analogue and the digital, the theoretical and the artistic, and uniting practitioners across disciplines.

FutureEverything is an innovation lab for digital culture and an annual ideas festival exploring the space where technology, society and culture collide. Featuring thought-provoking panel discussions, original commissions and parties, this year it took place in arts venues across the city, from Wednesday 30th March to Saturday 2nd April.

This summary explores how the festival encourages multi-disciplinary collaboration between different creative communities through interviews with artists who embody this collaborative ethos in a variety of different ways. How do they bridge the divides between disciplines to break new ground and meet the challenges of the future?

Commissioned for FutureEverything, artist Ed Carter created Smoke Signals with engineer and technologist David Cranmer. Musicians Sara Lowes and Jo Dudderidge & Harry Fausing Smith and Hering, then devised original compositions in response to the piece, taking each performance in a new direction. “Working with a collaborator or collaborators is like working with a process or working with a data set,” Ed says. “You create a framework but leave a degree of openness which allows for the unexpected.”

Newcastle’s Occasion Collective chose to deconstruct the collaboration process behind their Babble series of improvised performances at Islington Mill in a lively workshop on the final day of the festival. The collective invited participants to get hands-on with improvised dance and live-sampling in sound and video, to help reveal the feedback loops between artists at the heart of their multilayered performances.

The concept grew from musician Jamie Cook’s final-year music degree performance, where he played with a saxophonist and manipulated her audio live, creating loops, sampling, applying effects and changing speed. “I wanted to use electronics in a very tactile way, so that the audience weren’t shut out between me and the computer screen,” he says. “They could see all of the sounds I was creating, they could see them being taken and then transformed. Over time I added more members from other media, like dancers and visual artists, which grew into this ensemble where everyone improvises live and feeds off each-other’s ideas.”

Each Babble performance refers to a short poem written by Charlie Dearnley, based on stories told by his grandmother, which “all grapple with a point of death or unburdening,” he explains. While performing, sensors on his costume feed to digital artist Sean Cotterill, whose software translates the movement into light and sound. “The idea of digital communities, using digital technologies to gather creative communities around them, is important to me,” Sean explains. Written in the supercollider language, Sean has put all his code for the show online, in the hope of developing further feedback loops beyond the live performance.

While process is an explicit part of Occasion Collective’s performances, each one feels stirring and organic. “It’s an attempt at honest expression which is heightened and realised through collaboration and working with others,” Charlie says, “acknowledging, for myself, the inadequacy of words in genuinely conveying experience; trying to create something that is more engaging.”

Engaging people is the challenge at the heart of Nelly Ben Hayoun’s work, as she explained after her talk at the Intelligence panel. The so-called ‘Willy Wonka of design’, Nelly is a one-woman nexus of collaboration who creates experiences to generate social action around science and technology, often space exploration. She assembled the International Space Orchestra, the world’s first orchestra composed of space scientists from NASA’s Ames Research Center and the SETI Institute (Search for Extraterrestrial Life). Featuring original music by Beck, Damon Albarn, The Prodigy, Penguin Cafe, Two time Grammy award winner Evan Price and Bobby Womack, she convinced scientists and astronauts to participate in an ambitious musical retelling of the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969.

Video embed: The International Space Orchestra_ Official IFFR selection 2013 (https://vimeo.com/57863847)

“There are audiences that are not keen to be transported or play any part, but it’s my role to then force them into it,” she explains. “Most of the public is becoming quite lethargic, so it’s really difficult to get them to move. My way of doing things is what I call total bombardment: getting to people through the fields of music, design, arts, theatre, tech, digital and architecture. Even though you might not want to be engaged with the issues or the questions I’m raising, you will find yourself confronted, in any case.”

Nelly studied at the Royal College of Art under Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, who inspired her problem-finding rather than problem-solving approach to design, particularly with regard to future challenges and the potential impact of evolving technology. Her most recent project, Disaster Playground, investigates the planet’s emergency procedures through attempts to stage a simulation of an asteroid strike. Soberingly, Nelly finds that only about 20 ageing scientists are charged with planning for disasters such as asteroid collisions and meteor showers.

Video embed: Disaster Playground Teaser (https://vimeo.com/107466074)

“I’m applying critical thinking and critical design, but also looking at a range of artistic fields to see how we can merge all of these different disciplines to aim for social action,” Nelly says. “I apply Antonin Artaud’s theory of the Theatre of Cruelty to the way I engage members of the public with scientific research, looking for much more extreme and visceral ways to engage them, which you open up through collaboration. Whenever I work with scientific partners or sociologists or philosophers, I pick the ones who will fight with me. I believe that conflict generates innovation.”

The Turner Prize-winning Assemble collective prefers a more harmonious atmosphere. Comprised of 18 members, Assemble’s collaborative approach to architecture and urban development puts local people at the heart of development, implementation and ultimately the long-term life of each project. They also work on sustainable principles, choosing where possible to work with pre-existing local materials, reusing or repurposing them to better serve the area’s needs.

Assemble’s Mat Leung posed new ways to think about communities in a thought-provoking panel discussion with science fiction writer and futurist Madeline Ashby and new communication technologies expert Sarah Kember at FutureEverything’s Community panel. “[Sarah, Madeline and Assemble] understand community not as a monolithic term,” Mat explains. “Obviously there are loads of different elements to it. The term community is difficult because it assumes a single kind of identity, but together we wanted to interrogate that.”

Multiple communities can exist simultaneously and overlap in a given area, such as a community of residents, who Assemble empowered through the Turner Prize-winning Granby Workshop project, creating jobs through rebuilding a neglected area of Liverpool from the grassroots up; or a community of makers and artists, with whom they worked on the Blackhorse Workshop project in East London.

The Community panel developed a theme that ran through the festival: that no one individual or group is capable of meeting the challenges of the future alone. Finding ways to positively engage multiple stakeholders with a variety of knowledge and skills is vital to finding solutions that meet the needs of the wider community.

“Our successful collaborations come from an understanding that there’s a diversity of stakeholders, skills and knowledge,” Mat says. “We’re interested in a broad range of things, but we acknowledge we’re not amazing at everything. Each different member of Assemble has their own training and expertise, but when we work with a community, people who’ve been there for 15 years know more than we do – they’re experts in a different way. They might not know about which materials to use for a given job, but they can tell you the effect of a layout or the practical implications of what you’re doing. You have to acknowledge that people are experts in different fields”.

Projecting a vision into the future can be one of the hardest challenges for architects – but Assemble have developed what appears to be a powerful and effective way of ensuring the longevity of projects. “When you say ‘Let’s talk about the near future’, architects get hysterical, designers go into meltdown,” Mat explains. “As soon as you say community, legacy, or things like that, it brings up a set of expectations. But what you’re really saying is that you want your idea to be taken on and exist beyond the period you’re directly involved in its life. So we’ve found that collaborating with the community throughout the process, through workshops for example, is a great way to encourage people to continue using spaces after we’ve moved on.”

The enthusiastic spirit of collaboration fostered by FutureEverything transcended each event and sparked conversations between practitioners from a variety of different fields, who gave each other new perspectives through which to consider their own work. Drawing on the participatory ethos of progressive digital communities, the festival encouraged a refreshingly open atmosphere. But how to keep this energy going once the festival comes to an end? Many of the artists involved shared their processes in the hope that others can build on their achievements. The vibrant creative melting pot FutureEverything presided over will ensure that the new connections created will lead to even more inspiring projects in the years to come, from networks that extend far beyond Manchester.

Find out more about FutureEverything.

Featured Image: Stock photography from Google Image search “happy creative tech startup”

Neoliberal Lulz: Constant Dullaart, Femke Herregraven, Émilie Brought & Maxime Marion, and Jennifer Lyn Morone.

Showed at the Carroll/Fletcher Gallery 12 February – 2 April 2016.

Neoliberal Lulz asserts to have born witness, arm-in-arm with rest of us, to an unprecedented shift in the volatility and increasing speculative power of financial markets and the dissolution of value indexing to physical commodities. This relationship has been made particularly palpable in the realization that investment banks and corporations hold a tremendous sway (perhaps even tremendous to an unknowable degree) over our lives. The four artist/groups brought together make work as a way of trying to bring this dynamic into knowing.

Neoliberal Lulz is not so much about this relationship, or the realization of this relationship, between market forces and lived experience. It’s more accurate to say that the exhibition and the artworks contained within it rather serve as a populist blueprint for how individuals can talk to the market. If political economies speak in the limited language of supply and demand, then how can we make ourselves heard?

New media is a particularly good way of addressing this question because of the way hardware and software must constantly negotiate the terms of inter-communication. The success of media is dependent on this trafficking in translations, between file formats, online and IRL, technical apparatuses, outdated and current softwares. So when artists like Constant Dullaart, Femke Herregraven, Émilie Brought & Maxime Marion, and Jennifer Lyn Morone make themselves “corporate,” mimicking the neoliberal virus, this move feels right at home with the kinds of techno-alchemist work being displayed.

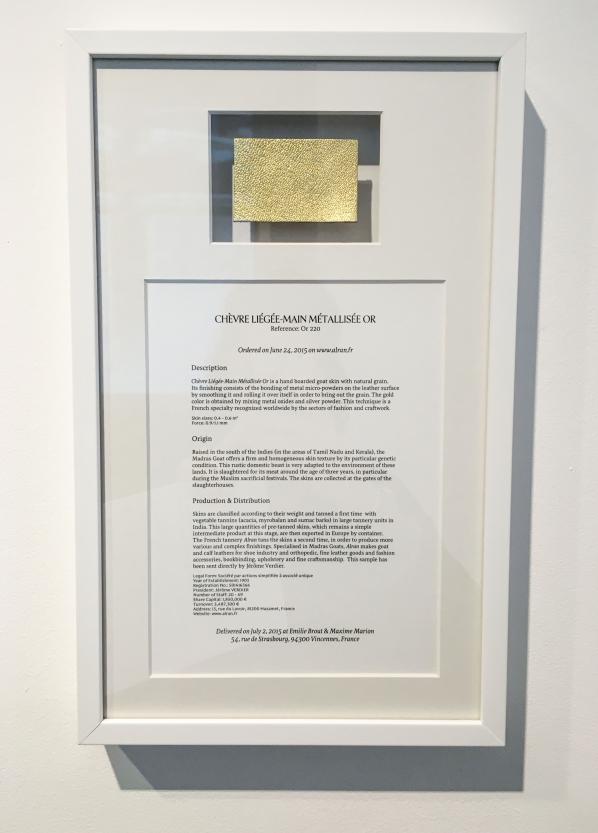

Femke Herregraven makes the mystifying lifespan of high frequency trading material, which feels a lot like spinning straw into gold (or perhaps the other way around). Her works rehearse this slippery, ambivalent relationship between value and objects, indexes and standards. In this way Herregraven’s works ground the exhibition in a similar way as does Constant Dullaart’s Most likely involved in sales of intrusive privacy breaching software and hardware solutions to oppressive governments during so called Arab Spring: by memorliaizing in cold, clunky materiality the “immaterial” processes that are active under the banner of neoliberalism everyday. Three of the four artists on display have incorporated—Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc, Untitled SAS (that’s Émilie Brought & Maxime Marion), and DullTech™ (Constant Dullaart). Between these companies the process of how to become a company is cracked open, revealing how sophomorically simple and complicated the process is, how much paper detritus and nondescript stuff is secreted as byproduct. Constant Dullaart here adds a lesson on the aesthetics of startups with an entire room dedicated to the oddly-familiar B-roll shots of airplanes cut with inspirational platitudes. Jennifer Lyn Morone adopts the the aesthetics of a kind of good life marketing that is gender-targeted, and operates by corroding away what’s already there (mental health, well-being) to make its own market gap.

But I tell you this: the best part of the exhibition isn’t on display. Ask the front desk about buying shares of either Untitled SAS or Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc. This is the heart of the exhibition, and it’s either lamentably sidelined or a brilliantly premeditated that just inquiring about the purchase can reveal so many gaps and uncertainties.

When I visited the exhibition, gallery attendants very kindly filled me in on the bold point details of buying shares, to the best of their ability. They explained that Unititled SAS shares sold for €30.00, with a €25.00 admin fee that went straight to Émilie and Maxime. It is not split with the gallery, as often the the sales of an art object are. Was the gallery entitled to any part of the sale of shares of Untitled SAS? Sort of: fifty-percent went to the French government, twenty-five percent went to Émilie and Maxime, and half of the remaining twenty-five percent went to the gallery. Did a new contract have to be drawn up to negotiate the profit negotiations between the gallery and artists who had incorporated some capacity? No, the normal consignment contracts were used (they did not share what the terms of these contracts are; I did not inquire).

What about shares of Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc.— how much did they cost? This was a decidedly trickier question, with nationality and class-based restrictions and allowances. The general gist was that since Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc. is registered in the U.S.A., that American citizens are subject to tax; English citizens are not. For English citizens there are also different price points and clauses for lower-income prospective investors. This does not apply to U.S. citizens, who are required to prove salary requirements before purchase can be approved.

Had anyone bought any shares yet, for either company? No.

Eventually, the attendants printed me a Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc. Instructions for Prospective Investors document: four-pages single-sided, unceremoniously stapled together. For those unfamiliar with this kind of legalese, it’s a bizarre artifact from another planet. Everyone should ask for a copy.

The title Neoliberal Lulz might tip its hat to the tradition of online trolls and their persistent, agnostic vitriol, but the exhibition itself feels like it sets out some very real stakes. This is a good thing, because an exhibition interrogating the asymmetrical relations of production and profit taking place at a prominent art gallery in Fitrovia (a borough in itself that is paradigmatic of these inequities) could have really been smug, smarmy, shit. The hypocrisy of an exhibition that singularly railed against the unmitigated growth of big business while standing amongst its spoils would be too much. But Neoliberal Lulz is not this: it is far more nuanced in its message, far more unclear on its value judgments. As an art exhibition Neoliberal Lulz did well to espouse the artist-as-researcher model. It helps make sure that the exhibition has legs outside of the exhibition space. The fact that most of these artworks have a life outside of the domain of art, circulating within the very thing they’re critiquing, legitimates their output. The other thing that Neoliberal Lulz does well is not to dwell on the narrative of the disenfranchised. I don’t say this because it’s not important but rather because it just simply wouldn’t read.

Neoliberal Lulz feels like a prompt that comes at a timely moment, slotting in to conversations like this, this, and this. It criticizes at the same time as it offers options, which seems like a rare combination these days. “What is to become of the future for young artists?”–the people wail, lamenting that much of the young, creative elite inevitably ends up siphoned off into the tech startup culture. Neoliberal Lulz seems to say this doesn’t have to be a bad thing, and I’m inclined to agree. All’s not lost when artists adopt an if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em ethos, particularly when they do so with a critical bent. Deeply sardonic and ruthlessly interrogative, Neoliberal Lulz is a successful venture into addressing the malleability of contemporary political economies to more progressive ends.

Carroll/Fletcher Gallery

56-57 Eastcastle St.

London W1W 8EQ

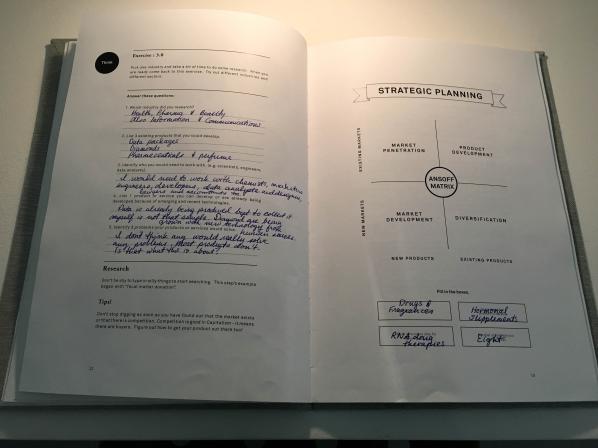

Despite its image of rapid technological change, progress under capitalism has stalled. Spinning ever faster is not the same as going somewhere. Contemporary Accelerationism wants to take off the brakes, and it is enlisting art’s help to do so.

Taking its name (like every good movement) from one of its critics – Benjamin Noys claims credit for naming the historical tendency in 2008 – contemporary Accelerationism has both a philosophical and a political form with the latter only weakly related to the former. What Epistemic (philosophical) and Left (political) Accelerationism have in common is an attitude of “prometheanism”, of amplifying our capabilities, of rationally overcoming intellectual and material limits. Of hacking the systems of philosophical and political thought to find the exploits that will allow us to increase our knowledge of them, our control of them, our reach through them. Hopefully this will work out better than it did for the original Prometheus of Greek myth (or for Ridley Scott).

Contemporary Accelerationism may seem heretical compared to the “folk politics” and philosophy that it contrasts itself with but it is not (however some people may start essays) the capital-intensifying Accelerationism of 1970s continental philosophy or its killer-robot-welcoming successor in 1990s cyberculture. From the point of view of the former it is too immediately critical of capitalism and from the point of view of the latter it is an off-ramp on the road to the singularity. It is also not the pure speed of Paul Virilio’s dromology, or the experience of lack of time of the overworked neoliberal subject.

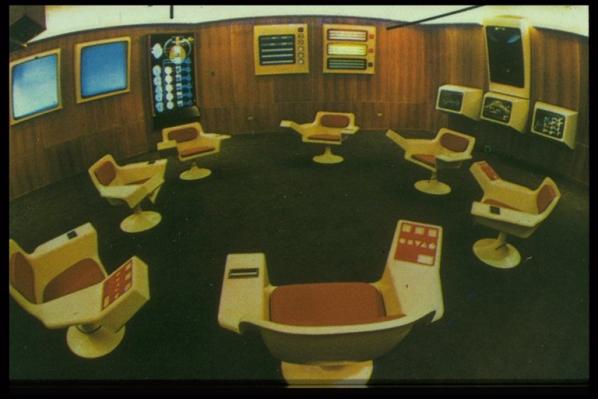

Accelerationism is a progressive attitude towards the liberation of reason and production – and therefore selectively technology – rather than the fetishisation of them. The “real” accelerationists in these senses aren’t working at Google, although they might in time exploit technology developed there. Chile’s early 1970s Cybersyn project provides an informative precedent. It sought to accelerate transition to a socialist economy using limited and almost obsolete mainframe and teleprinter technology. Its Accelerationism lay in the attempt to rationally analyse and spur growth in industry to increase the rate at which it developed, not in technofetishism.

Philosophical Accelerationism is “Epistemic Accelerationism”, represented in the writing of Ray Brassier, Reza Negarestani, Peter Wolfendale and others. This is a neo-rationalist philosophy, a programme of “maximizing rational capacity” and the ability to reason about or navigate our knowledge of the world. This is a self-revising, non-monotonic, socially situated reason very different from the logicism of 20th century rationalism and its detractors (although logics have advanced considerably as well).

Two new journals are taking an Epistemic Accelerationist approach to art and culture. In the UK, “After Us” shares a designer with former CCRU member Kode9‘s Hyperdub record label. In France, “Glass Bead” takes its name from Herman Hesse’s imaginary game of knowledge described in his novel of the same name. Both are haunted by the legacy of C. P. Snow’s 1950s “Two Cultures” of science and the humanities, with “After Us” explicitly invoking the need to reconcile them. This isn’t the first time such a move has been called for, and previous attempts make clear that scientists tend to make as bad artists as artists make scientists. The contemporary artworld is also not under-populated by transversal and interdisciplinary research and its aesthetics. Regardless, both provide thought-provoking cultural insights and resources. And the first issue of Glass Bead features, among other articles and interviews, Colombean mathematician Fernando Zalamea, whose accessible promotion of contemporary mathematics and production of a synthetic philosophy based on it deserves much wider attention.

Escaping the radial velocity of asset-class zombie formalism is the focus of Suhail Malik’s “On the Necessity of Art’s Exit from Contemporary Art” (I’ll be reviewing the book for Furtherfield). Malik describes Contemporary Art’s self-image of escape (from society and art’s own limitations into a space of freedom) that disguises an inescapable and complicit recuperation of novelty. To move beyond this he proposes a strategy of exit (which contrasts interestingly with designer Benedict Singleton’s discussion of traps). This is not a seasteading-style fantasy of libertarian secession, rather it is an attempt to identify the next move in the game of art after a long impasse and to return art to a more grounded and constructive role in society.

A group centred around The New Centre For Research (whose events and video archives I cannot recommend highly enough) are seeking to apply neo-rationalism to art in order to effect just such an escape from the outsideless beige singularity of Contemporary Art. This would be an art intentionally constructed to make the rules of contemporary art and of its own construction explicit, allowing artists to reason about this and to thereby come to understand how to escape the seemingly irresistible aesthetic and political cage of contemporary art. Amanda Beech‘s “Final Machine” (2013) prefigures this kind of analysis of the structure of images and their situatedness in the networks of power that produce contemporary art. Diann Bauer‘s collaboration on the art and finance R&D project “Real Flow” is another good example. Bauer has also produced videos for Laboria Cuboniks (see below) and for accelerationism-related events. Beech, Bauer and others have held a series of discussion panels on the subject of “Art and Reason” (one) (two).

Curator and critic Mohammad Salemy has curated a series of art shows with Epistemic Accelerationist themes – “Encyclonospace Iranica” in Vancouver, “For Machine Use Only” in Vienna, and most recently “Artificial Cinema” in Prague. Each of these has created an artistic critical context for networked systems of perception and knowledge, engaging with the political possibility of their being repurposed to more emancipatory ends in the future.

A self-aware, critical, politically committed art aware of its institutional context that is nonetheless still recognisable as art may sound like a stretch but there are precedents in the work of veteran conceptual art collective Art & Language, most obviously in their early “Index” installations and in their later “Incident In The Museum” paintings. There is another way in which Art & Language provide a precedent for the New Centre group – a decade ago they theorised genre as a means of interrupting the frictionless misrepresentations of Contemporary Art, similarly to Malik’s (and, as we shall see, Beech’s) emphasis on recategorisation.

Contemporary political Accelerationism is “Left Accelerationism”, exemplified by the writing of Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams. Initiated by the “Manifesto For An Accelerationist Politics” and fleshed out in the book “Inventing The Future“, Left Accelerationism claims that some of the technologies created by capitalism can be repurposed and even intensified to enable an achievable socialist future and unleash the creative forces in society that they currently repress. As Srnicek and Williams make clear in “Inventing The Future”, this is not in opposition to other struggles but rather a means of materially supporting them.

As a group that often struggles with basic material support, the Left Accelerationist project can hold some appeal for artists. Universal Basic Income (pursued as Srnicek and Williams propose – within rather than as a reason to dismantle the rest of the Welfare State) for example would benefit artists (and musicians, actors and other creatives) in much the same way as earlier welfare state provisions. Artists can support this, rather than having to make the specific moral case for artworld subsidies, as an effective means of solidarity.

Full automation, another of Srnicek and Williams’ proposals, is the theme of the show at Kunsthalle Wien. The diverse work included drives home that art and curation needn’t be propagandistic, uncritical or overly serious to promote or engage with Accelerationist themes.

In their essay in the book “Speculative Aesthetics” (2014), Nick Srnicek proposes an Accelerationist aesthetics of transforming a “data sublime” into forms comprehendible by human beings, an aesthetic of user interface-style efficiency and transparency rather than beauty. The example Snicek gives is of transforming a complex economic model into a tool for the manipulation of economies. In the same volume, Amanda Beech (again) argues that rather than “asking what images mean, or if it is possible to mean what we say” we should produce an art that leaves behind the category of the uncategorisable in order to unravel the political project that contemporary art is subject to.

Likewise Alex Williams’ consideration of Accelerationist aesthetics in the article “Escape Velocities” (2013) emphasises aesthetics as a means of presentation of conceptual spaces, rendering them tractable to the human imagination, as well as explicitly discussing interface aesthetics with reference to Cybersyn. They also mention the concept of Hyperstition, which we will return to below.

Laboria Cuboniks are a pseudonymous collective who have produced the “Xenofeminism” accelerated feminist manifesto. It’s a strikingly designed production (the website was designed by artist Patricia Reed) that is already inspiring artistic production. The “3rdspace” show describes itself as “a response to XF and an exploration into the potentials of technology to escape modern structures of control”, building on Promethean themes.

Morehshin Allahyari & Daniel Rourke have produced the Additivist Manifesto for art in the Anthropocene (the video for it features the “Urinal” 3D printable model I commissioned from Chris Webber). They “…call for you to accelerate the 3D printer and other technologies to their absolute limits and beyond into the realm of the speculative, the provocative and the weird”. This is the kind of acceleration through (and into) art that works as both epistemic and left accelerationism without merely illustrating the program of or being instrumentalised by either. It is accelerated critical theory.

And beyond the visual arts, musician Holly Herndon’s most recent album was described by collaborator Mat Dryhurst as being designed to support Left Accelerationism.

While contemporary accelerationism is at pains to signal how far removed it is from CCRU-era Nick Land (let alone their contemporary work), the CCRU’s instrumentalised mythological theory-fiction has resources that are of interest. The slippery concept of “hyperstition”, essentially self-creating science fictional or mythical entities, is key. Cyberspace is hyperstitional, as was the writing of H. P. Lovecraft, as was Neoliberalism, and the music of Hyperdub. They are all unreal entities that bootstrapped themselves into reality via the human imagination. Hyperstition is an example of rational irrationality, or at least rationalised irrationality.

Seeking to harness hyperstition for a moral or political programme has something of the air of trying to summon Cthulhu for social justice, or to turn Skynet into a phone tree, but Williams’ “Escape Velocity” mention of Hyperstition as a means of creating visions of a better future as something that will have been possible is compelling. Hyperstition should be more (mis-)used in art than it currently is, and its creation all but demands activity outside the existing artworld.

International art collective (and CCRU collaborators) Orphan Drift‘s autopoietic mythologies realised in glitch art videos, installations and writing provide a historical point of reference here.

The earlier work of Reza Negarestani serves as a bridge between the CCRU era and the present. His novel of theory-fiction “Cyclonopedia“, 2008, evokes hyperstitional entities from the layers of trauma present in the politics and geology of oil and the Middle East.

In art, reason and rationality may inspire memories of dry conceptualism or stern Soviet abstraction but contemporary art’s hidden and totalising rules are no less binding and are in desperate need of exposure and critique. The task of uncovering and overcoming them presents a challenge to perception and representation that meeting will amount to much more than “art about art”. Perhaps we can use Deep Learning and neural nets to pull the ghosts of genre and medium specificity out of contemporary art then intensify them rather than make puppyslug kitsch… but that’s another story.

Left Accelerationism’s design tasks and the hyperstitional making of its future seems to have always been possible to provide more challenging alternative projects to the manufacturing of yet more zombie formalism, and as “The Promise Of Total Automation” demonstrates this needn’t take the form of uncritical propaganda.

In contrast to these approaches, I feel it’s worth asking what a direct equivalent to Left Accelerationism for Contemporary Art would look like. Which aspects of the contemporary artworld would be worth intensifying, appropriating and pushing further to create an alternative? And what would the vanishing point for such an art be in order to avoid recuperation into the generic space of Contemporary Art?

Accelerationist art is working out how to climb over the event horizon of contemporary art, helping to make a better future seem possible, analysing and transforming technocapital, and ironically intensifying the trajectories of new technology to critical excess. As the logic of neoliberalism colonizes personal space, time and identity, suggesting that we need to move faster in any way may seem perverse or complicit. Accelerationist art is part of a project to grab the wheel rather than slam on the brakes and to thereby move beyond the exhausted constraints and artistic apologetics of the logic that is eating the world.

(Updated 2016-05-18 to include more examples.)

Accelerationist Art by Rhea Myers is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The global financial dictatorship presents us with a paradox: while the economic transactions capable of shifting the destinies of entire countries are the result of performative language, it is language itself that, in turn, is transformed and subjected by the flows of financial markets. Such a paradox may be understood as a negative feedback loop: a relational process in which one of the actors of the relationship is amplified and expanded (the economy) while the other is weakened and submitted (language). The effects of this paradoxical feedback loop on politics are evident and clear: the linguistic exchange which feeds the public sphere, and therefore the possibility of thinking about the democratic organization of society, diminishes and becomes neutralized because of its submission to the market, up to the point of canceling politics itself. Politics, considered as a space where daily life becomes realized, is reduced to an engine which merely executes the algorithms of finance. In this reconfigured field, the common good becomes increasingly unimaginable as individuals are transformed into cellular automata: inside their bodies, the code of economic behavior and the flat, mutilated language that capitalism requires to operate frictionlessly are already inscribed.

Whoever refuses to enter life as a mere cellular automaton will be annihilated by the financial dictatorship, which is currently passing through an extremely murderous stage: necrocapitalism. Achille Mbembe claimed that the ultimate expression of sovereignty lies broadly in the power and the capacity of deciding who may live and who must die. This was known as necropolitics. Today, the dictatorship of finance prescribes a progressive and quick reduction of the sphere of politics, with the aim of canceling the restrictions that laws and codes used to impose on the flow of capital. And governments have indeed shrunk, turning thus into little more than facilitators of the unstoppable progress of capitalism. However, they have not stopped to exercise their operational capacity to kill and let live. True power has been transferred directly into the hands of capital, who now determines which lives should be halted and which should continue. The power of capital has increasingly turned into a murderous one that, nevertheless, is still executed by the officers of the old sphere of politics.

Mexico passed from necropolitics to necrocapitalism not by force but by the signatures of the presidents and ministers of finance of Mexico, the United States of America and Canada who, in 1992, signed the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). What has happened in Mexico since then? A chaotic chain of privatizations, looting and crime, all of which have been executed with a hitherto unknown intensity thanks to the almost complete destruction of the former sphere of politics.

After the forced disappearance of the 43 students of Ayotzinapa, Elisa Godínez wrote that “it is not surprising that the corporate sector is heading the demands to repress all social protests which directly affect their properties and interests, arguing that the rule of law should be respected.” [1] It is true that, in the post-NAFTA era, such a position comes as no surprise. However, the true novelty lies in the fact that now the Mexican State no longer defends only the interests of national corporations, but also those of multinationals. And this is not a minor novelty: all sorts of extraction industries, for example, have multiplied their concessions and profits thanks to such a defensive stance. And they have done so while devastating lands, ecosystems and people with almost complete impunity. According to data collected by the Red Mexicana de Afectados por la Minería (Mexican Network of Persons Affected by Mining), 450 tons of gold have been extracted from Mexico, a quantity almost three times larger than the 185 tons extracted during Spain’s colonial domination. This unprecedented looting has particularly benefited Canadian and North American companies, who make up almost 85% of all private mining concessions, while paying back a mere 1% of what they extract to the Mexican government [2].

Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution deals with the property of land, water and natural resources. It originally established that “the property of lands and water resources inside the limits of the national territory corresponds to the Nation.” Obviously, this vision had to change radically under necrocapitalism since, instead of recognizing the primordial nature of private property and the right of capitalists to posses it, it indicated that “the Nation” was, in principle, the sole owner. Now, thanks to recent reforms to Article 27, “the Nation” has acquired the right to transfer the dominion over lands and territorial waters (and, consequently, over the humans and non-humans who inhabit them) into private hands. Article 27 is today the red carpet extended by the Mexican State to welcome the financial and linguistic flows and algorithms of necrocapitalism in grand fashion.

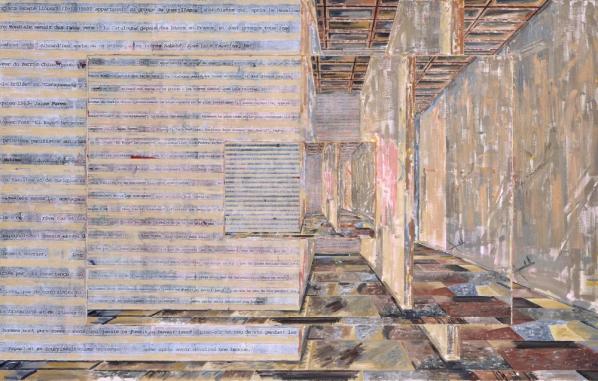

The piece “El 27 | The 27th” is an example of what algorithmic politics can be. Far from trying to point to a possible escape from the horror and exploitation of necrocapitalism, algorithmic politics deepens its murderous potential instead. Despite its relative usefulness as a hired murderer, the traditional sphere of politics is terminally ill: it is too old to carry out rapidly and efficiently the demanding tasks of necropolitics. So, once exhaustion has completely died out its powers, politics made by humans will have to be substituted by algorithmic politics, that is: politics made by machines.

In this piece, an algorithm operates directly on the text of Article 27 in the following way: every night, after the activity at the New York Stock exchange has come to an end, a robot obtains its last closing price and its respective percent variation. If the variation is positive, another robot chooses a fragment of Article 27 randomly, translates it into English automatically, and inserts the translation into its corresponding place within the original text written in Spanish. Given enough time, the algorithm will produce a version of Article 27 fully readable in an effective – yet incorrect – English. An automated English that will already have attempted to displace humans brutally, even though they might still be fighting for a territory delimited by language only, and refusing to die. An automated English that will have already eroded a land delimited by language only, rendering it unrecognizable: torn, exploited, almost dead.

“El 27 | The 27th”: http://motorhueso.net/27

“[A] hundred reasons present themselves, each drowning the voice of the others.” (Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations: supra note 11 § 478).

For Part 1 click HERE.

For Part 2 click HERE.

Voice and unintelligibility play a greater, complex role in reasoning than the Left or Right accelerationists are prepared to admit, or fail to see. Establishing ones political voice is far broader and extensive than any of these thinkers take it to be, and is not simply the by-product of a phenomenological given unable to envisage any political alternative. Voice has to take priority here, for how else does one actually communicate? By this, we don’t have to take Voice to be the literal act of saying something out loud, or examining the behaviour for doing so. It can interpreted both as a metaphor and means encompassing every political act to which it can be applied; having a voice, or an opinion, hearing the public representation of someone, or of a community, wanting to being heard, letting someone have a say in the matter, etc. Above all it takes on the force of voicing ones own condition.

Might every form of modern communication then, be it a WhatsApp message, a bored glance at a meeting, cynical internet comments to nondescript mumbling, be one of ordinarily voicing our own condition? Perhaps even more so when it is mediated by an infrastructure (sometimes especially so). Both Voice and infrastructure are components of communicating indirectly, as most language games tend to do, whether face to face, face to mirror or interface.

The problem with philosophy is that the ordinary gets blamed, largely as the historical list of philosophy’s complaints almost always aim for the ordinary first as if its triviality is, by itself, not to be trusted with political or rational action. Indeed the very task of calling the ordinary to our attention, takes into account that we have lost interest in it. Perhaps it was already assumed that the market silently reduces the depth of ordinary communication and circumstance to capitalist knowledge anyway. Or maybe since ordinary life is increasingly and consistently mediated through online platforms, technology has overtaken its significance.

Yet what Ordinaryism seeks to uncover is that Voice does not constrain freedom because of its vulnerability: it is only because of vulnerability that voice expresses the freedom to reason in the first place. This is the split that severs both the sovereign rationality of Accelerationism (and Sellars), and the non-sovereign self of Ordinaryism (and Cavell). Indeed, this appears to be Cavell’s political lesson: it seems rational to want build a platform for others to air their democratic voice and decry any ineffective basis in favour something more determinate, more grounded, more inhuman. Yet freedom and justice only begins if a community is capable of ‘finding’ their own voice in the face of injustice. Likewise freedom is constrained if other voices repudiate the voice of others. There is no cognitive purchase for this, and no pre-built, implicit, or explicit ground for determining intelligibility either. So we have to ask, how else can the inhuman make itself intelligible unless it gives voice to its own condition? (As an aside, what else is philosophy but a set of specific and singular voices crying out for recognition in their appeal? A voice that may be acknowledged, yet equally repudiated? Just as the sound and look of Voice matter in reasoning, [how it persuades, how it strikes you] so too does the sound and look matter to philosophising arguments and deductions.)

The easiest way to round these political concerns up is to show how the very need to bypass the vulnerability of Voice, the need to provide an ‘answer’ or ‘solution’ to that vulnerability, is the same philosophical question that concerns solving skepticism. This is the heart of Cavell’s philosophy.

Following Naomi Scheman, the heart of transcendental inhumanism to which the epistemic accelerationists follow aims to draw attention to what underlies the possibility of our ordinary lives. But in Ordinaryism, the Cavellian rejoinder must insist that “the ordinariness of our lives cannot be taken for granted; skepticism looms as the modus tollens of the transcendentalist’s modus ponens.” (Scheman, “A Storied World”, In Stanley Cavell and Literary Studies, 2011 p.99). Whereas Accelerationism posits a renewed set of tools to re-determine intelligibility in an era of supposed ‘full automation’, Ordinaryism speaks to these same conditions but where intelligibility routinely breaks down, is endlessly brittle, always delicate, sometimes connects, but is never ensured or determined by philosophical explanation alone. What might it mean to understand the fragmented world of machines as a uniquely literary responsibility?

In other words, a future world of increased automation needs a romantic alternative. And it is sorely needed, because in this future order where automation is assumed to outpace human knowledge, or supersede it in any case (amplifying existing industries, or creating new ones) Ordinaryism speaks of new moments of doubt which constitute the skeptical fragments of ordinary life with machines. Perhaps also of machines. It might take on a specific personal form of questioning and living with what these new forms takes on; “what does this foreign mapping of data really know about me”, “what does it know about all of us?”, “Am I just being used here?”, “How can I know whether anyone is spying on me?”, “why are they ignoring me?”, “what on earth does that Tweet mean?”, “what’s happening?”, “what am I supposed to think about this”, “Why would I care about you’re doing?”, “I need to know what they’re doing.”

There are innumerable ordinary circumstances where a life with machines begins to make sense, but also starts to break down in all the same places: how might one suggest that a machine “knows” what it’s doing, or that “it knows” what to do? Where does the scalability of automated systems start to break down, and what sort of skepticism does it engender when it does? What happens when software bugs, and unpredictable acts of mis-texting chagrin habitual pattern? How might such finite points of knowledge exist, so as to understand and inhabit systemic doubt? What are the singular and specific means for how such systems are built, conceived or decided? And most of all, how might we even begin to characterise and acknowledge the voices which emerge within these systems? You might say that Ordinaryism wishes to extract acknowledgement out of the knowledge economy.

What is required then, is both a Cavellian critique of epistemic accelerationism (what potential political dangers might arise if Voice is repudiated) and why its solutions to solve skepticism through collective reasoning and self-mastery are no different from skepticism itself. But to do that, one also has to take account of how Cavell brings an alternate approach to imagining how normative rules are implicit in practice. This is not an act of opposition, more of a therapy, which might be needed, especially as politics is involved.

Now, despite the fact that Cavell’s philosophical questions work (almost) exclusively in the Wittgensteinian domain of articulating and expressing normative concepts which regulate speech and pragmatic action (beginning from his first essays Must We Mean What We Say? and his later magnum opus, The Claim of Reason) these texts don’t appear to be required reading in accelerationist and neo-rationalist circles.

Take the newly released art journal Glass Bead, whose aim is to suggest that any “…claim concerning the efficacy of art – its capacity, beyond either it’s representational function or its affectivity, to make changes in the way we think of the world and act on it – first demands a renewed understanding of reason itself.” If such a change in thinking is motivated by a renewed post-analytic approach to reason in a world of complexity (and an additional capacity for aesthetic efficacy), the continued omission of Cavell’s work into reason and aesthetics, is notable by its complete and utter absence. It’s enough to warrant the claim that certain imaginings of reason – in this case the abstract inferential game of giving and asking for reasons – are to be favoured over other types (usually with a secondary, pragmatist demand that science is the only authentic means for understanding the significance of the everyday).

In fact there’s a good reason for that omission: because Cavell discovered that he wasn’t able to ignore the threat of skepticism entirely, and instead discover it to be a truth of human rationality (is there anything more paradoxical than discovering ‘a truth’ in skepticism?). He instead sought to articulate how such concepts were not inherent features of inhuman ascension by means of inferential connection, but fragmented conditions of differentiated identity. In the eyes of the epistemic accelerationist, it’s as if there isn’t any possible option in-between some half-baked, progressive ramified global plan to expand the knowledge of human rationality, and a regressive fawning over the immediacy of sensual intuition. Fortunately, Cavell’s ‘projective’ approach to rationality questions this corrosive forced choice.

Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations sets up the key differences here. Instead of using Wittgenstein’s text as an introductory tool to show how the public expression of saying something can be explained and correctly applied (as Robert Brandom pedantically attempts), Cavell paid attention to Wittgenstein’s voice, as it invokes a specific and personal literary response to what happens when we are in search of such explanatory grounds (and how they always disappoint us). Perhaps more pertinently, Wittgenstein alluded towards an effort ‘to investigate the cost of our continuous temptation to knowledge.‘ (Cavell, The Claim of Reason, p. 241) Compare this to the current neo-rational appeal which has little to no awareness that the pursuit of certain knowledge (and the unacknowledged consequences for when it will go astray) might itself be inherently unproblematic. Because reason presumably.

It’s no accident therefore that Philosophical Investigations has become one of the oddest literary feats in Western philosophy, insofar that it presents itself as a personal account, rather than a systematic one. Cavell was not only the first to prise out a Kantian insight from Wittgenstein’s text, but also to ask the simple question of why does he write like this? It’s as if every single word, every ordinary word, now takes on the full power and insight as any theoretical term of jargon: as if a theoretical vocabulary isn’t wanted or needed. Why does Wittgenstein provide provocative literary fragments to elucidate his philosophical struggles? (the infamous ‘mental cramps’) Why does he raise literary devices to flag up disappointing conclusions: where a rose possesses teeth, beetles languish in boxes, and lions speak in packs of darkness? It’s an insight which lies in acknowledging that Wittgenstein’s unique literary voice is inseparable from his philosophical ambitions. It is not that he offers an anti-skeptical account to fully fix and explain what it means to say something: nor does he posit an implicit mastering of normative concepts, whereupon said possibilities are subject to further explanation (the conditions under which cognition or experience become possible).

It’s as if the theoretical problem doesn’t come with fully understanding norms implicit in practice, but the very situation in which using words like “rules”, “freedom”, “determine”, “correct” and so on, do not have the desired theoretical effect (in the accelerationist case, freedom). These are very nice words after all, but the neo-pragmatist theory is found wanting in their full expression, sufficient to the limits given when they are spoken not as a licensed inference, but as a creative effect. Cavell’s take on language thus, is that there is always something more to words than the current practice in which they are put to use.

The appeal to Wittgenstein’s literary conditions is what motivates Cavell to suppose that his theory of norms in practice isn’t something to which words are used to line up a certain conclusion, rather, the specfic and singular non-formal ordering of ordinary words in themselves provide a certain crispness and perspicuity, as well as difficulty and confusion. As Paul Grimstad suggests:

“Cavell wonders what one would have to do to words to get out of them a certain kind of clarity; to ground their meaning in an order. A kind of literary tact—the soundof these words in this order—would then serve as the condition under which we are entitled to mean in our own, and find meaning in another’s, words. The sort of perspicacity striven for here is not a matter of lining up reasons (it would not be “formal” in the way that a proof is formal), but of an attunement to arrangements of words in specific contexts.”

As Sandra Laugier chooses to describe it, Cavell’s posing of the Ordinary Language Philosopher’s question – “What we mean when we say” arises from “what allows Austin and [the later] Wittgenstein to say what they say about what we say?” For Cavell jointly discovered a radical absence of foundation to the claims of ‘what we say’, and further still, that this absence wasn’t the mark of any lack in logical rigour or of rational certainty in the normative procedures that regulate such claims. (Laugier, Why we need Ordinary Language Philosophy – p.81)

If agreement in normative rules becomes the presupposition of mutual intelligibility, then any individual is also committed to certain consequences whereupon certain rules might fail to be intelligible. Therein lies a simple difference: the espousal of following a universally applicable rule (as Brassier holds) and everyone else wondering whether that same rule has been correctly followed.

To mean exactly what we say, or to mean anything in fact, might be contingently mismatched to the specificity of what we say and project in any given context, hence one must bare the normative challenge that *what* we mean may differ from what we say.

The ordinary is saturated with these innumerable variations of mismatch through specific and singular situations, to which our attunement is threatened: when a co-worker fails to turn up to a meeting because they misunderstood someone’s directions or when a poor sap fails to get the joke he or she is the brunt of, or when a close friend misunderstands a name in a crowded bar. These moments are not insignificant wispy moments of human limitation swallowed up in a broad history of ascension, but become the necessary exhaust that emanates from a social agreement in which the bottom of our shared communal attunement falls away. With a language, I speak, but only insofar as we are already attuned in the projections we make.

As Cavell put it in this famously long (but necessarily long) passage;

We learn and teach words in certain contexts, and then we are expected, and expect others, to be able to project them into further contexts. Nothing ensures that this projection will take place (in particular not the grasping of universals nor the grasping of books of rules), just as nothing ensures that we make, and understand, the same projections. That on the whole we do is a matter of our sharing routes of interest and feeling, modes of response, sense of humour, and of significance and of fulfilment, of what is outrageous, of what is similar to what else, what a rebuke, what forgiveness, of what an utterance is an assertion, what an appeal, when an explanation – all the whirl of activity that Wittgenstein calls “forms of life”. Human speech and activity, sanity and community, rest upon nothing more, but nothing less, than this. It is a vision as simple as it is difficult, and as difficult as it is (and because it is) terrifying. (Cavell, Must We Mean What We Say? p.52)

If the reader might allow a Zizekian-style joke here (apologies in advance), it might elucidate Cavell’s insight further than the lofty quote above: “Two guys are having an heated exchange in a bar. One goads to the other, “what would you do if I called you an arsehole?”, to which the other replies “I’d punch you without hesitation.” The first guy thinks on his feet: “well, alright, what if I thought you were an arsehole? Would you hit me then?” The second guy reflects on his reply, “well, probably not” he says, “how would I know what you’re thinking?” “That settles it then,” says the first guy, “I think you’re an arsehole.”

Although the mismatch is played to (a rather ludicrous) comical effect, it offers a way into Cavell’s strange appreciation of skepticism’s lived effect. We intuitively know these ordinary situations, ordinary utterances and yet such acts are not instances of reason ascending its limits through knowledge, but are necessary and specific instances where reason’s endless depth and vulnerability enacts itself within such limits. The intelligble process by which the concept of “I think you’re an arsehole” arises, does little only to serve how brittle the semblances between saying and thinking portray. This for Cavell produces an anxiety; and it “… lies not just in the fact that my understanding has limits, but that I must draw on them, on apparently no more ground than my own.” (Claim of Reason, p. 115).