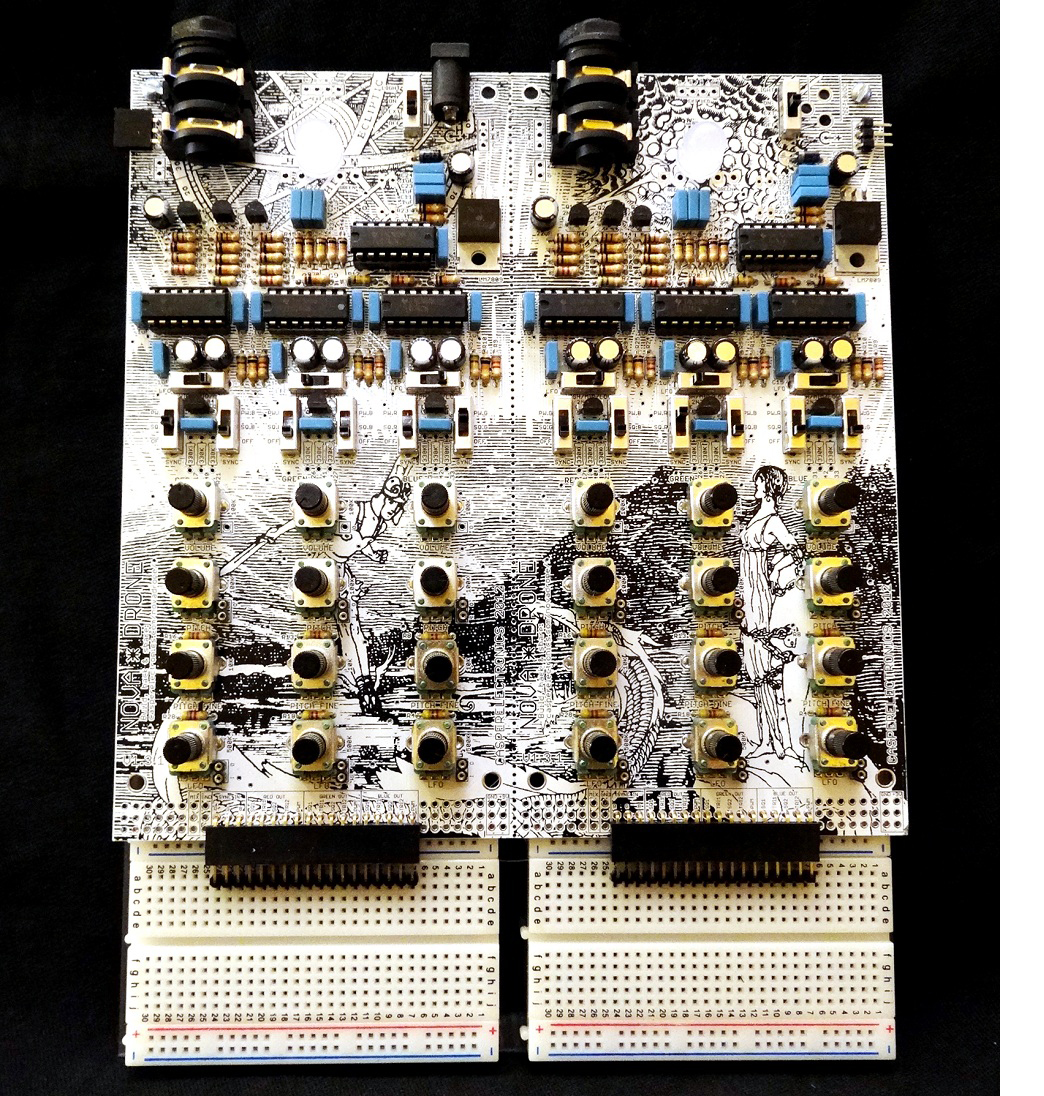

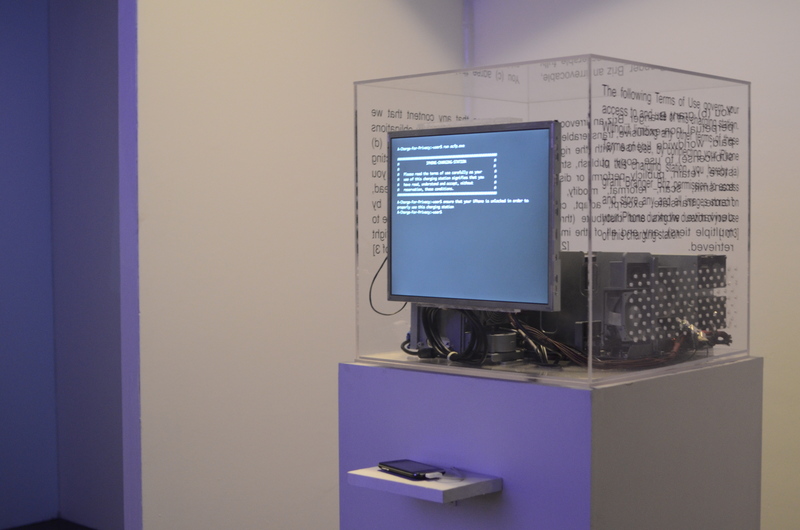

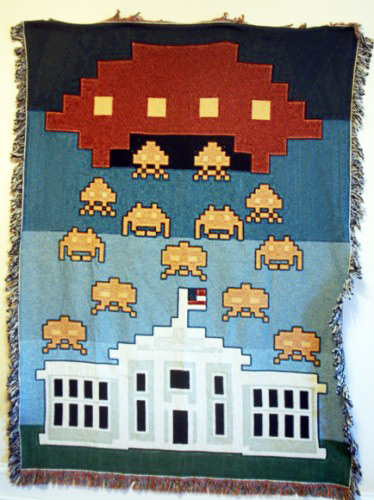

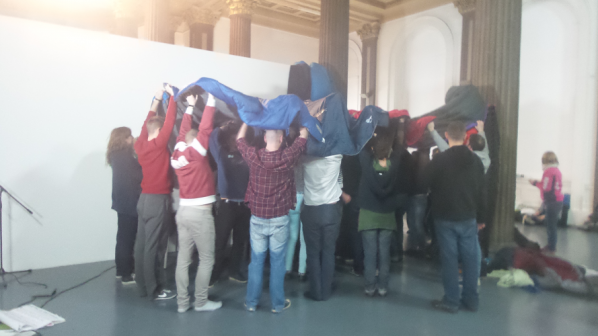

Featured image: “High Street Casualties: Ellie Harrison’s Zombie Walk” event at Ort Gallery on 11 April 2015, photograph by Marcin Sz

Like all of the best horror stories, this is a story about something that refuses to die. Despite, or perhaps because of being slashed and burned, prodded and poked in a laboratory and being raised from the grave at least three times, artist Ellie Harrison’s project, High Street Casualties, lives to fight on another day, perhaps with a number of sequels to come.

Our protagonist Ellie Harrison not only stars, directs, writes and produces High Street Casualties, she is responsible for a cast of thousands and hours of dragging an idea through the ups and downs of trying to bring an artwork to some kind of fruition.

I am one of those thousands, playing a small part at the start of the story. I had been interested in Harrison’s work for a few years, especially works such as Toytown featuring a dilapidated 1980s kid’s car ride which starts up and offers people free rides when news relating to the recession makes the headlines on the BBC News RSS feed. Works like Toytown, and Transactions, where Harrison sent an SMS message to a phone installed in a gallery every time she made an economic transaction, triggering a dancing Coke can every time a message is received, seemed to make immediate political statements to a wide audience and be accessible, and, dare I say it, fun.

By early 2013 there was spate of high-profile shop closures and the media was full of Death of the High Street scary stories. Blockbusters, Jessops and HMV all closed within months of each other along with other High Street regulars, being replaced by poundshops and charity shops (although Jessops and HMV got injected with some strange green elixir and brought back to life, lacking what small amount of soul they once had).

I was now commissioning public art for Art Across The City, Swansea, a job that until recently saw 36 temporary commissions in three years including Jeremy Deller, Emily Speed, Ross Sinclair and Jeremy Millar. I’d put forward Harrison at interview stage so was happy to finally commission her. As a former Blockbuster’s employee, who proudly fires off her years of service ‘1997-2000’, Harrison was keen to commemorate the 5th anniversary of the start of the global recession, taking the reported death of the high street as its subject. Following a week long site visit and research period, Harrison proposed a city wide participatory event that like many of her works, are ‘data visualisation’ projects.

This included researching every shop that had closed in the city centre and how many employees had lost jobs, and, hopefully tracking them down and getting them to stage a Zombie Walk through the city, inviting the public to join in, to make the high street and place for creative activity and raising community spirit. This wasn’t a Swansea problem, it was a UK wide problem, the blunt end of day to day global recession. Harrison was aiming to raise awareness and bring people together in a positive action.

Sadly, just three months until launch day, the powers that be in a muddled chain of command, from Swansea Council, Swansea BID and ultimately Art Across The City pulled the plug. It was a small condolence that I managed to make sure Harrison received an ominous sounding ‘kill fee’ of £1000, which would barely scratch the sides of the time spent not only on this, but of not working on other projects. It’s a credit to Harrison that she managed to raise the project from the dead, although even that process has not been without its own silver bullet, crucifixes and garlic bulbs.

After dusting herself down, Harrison proposed the idea to Glasgow International as a collaboration with award winning documentary film maker, Jeanie Finlay. The proposal, probably suffering a hangover from its Swansea cancellation was not selected. Harrison was then approached by Josephine Reichert from Ort Gallery in Birmingham about doing a project which “engaged with the local community”. High Street Casualties perfectly fitted the bill. Again, this was not critical of any specific city, just documenting what was happening globally. Reichert was more than keen to make it happen and submitted an application to Arts Council England to fund the project (on a greatly reduced budget), as part of Ort’s annual programme of exhibitions and events. This first application was unsuccessful but with Reichert’s enthusiasm and passion for the project it was successfully resubmitted. High Street Casualties was to become the last project in the Ort Gallery’s programme with a date finally fixed for April 2015, slap bang in the middle of the General Election Purdah, like a stake through the heart.

While some horror film productions like to promote the hype that filming on set was cursed, High Street Casualties seemed to attract all kinds of uncalled for and ill-informed bad luck. Birmingham City Council declared that they did not want to fund or be associated with the project. They continued to fund the rest of Ort’s annual programme, but withdrew money just from High Street Casualties as they thought it was, and just let this glide through you like a ghost, it was ‘making fun of unemployed people’.

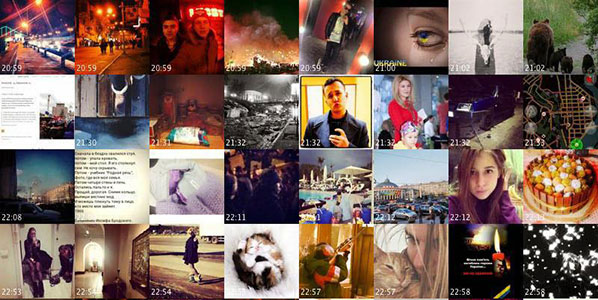

This left just £2000 for an 18 day production, not taking into account the work done over the previous year. Harrison points out that it worked out at £4.50 per hour, which is what she earned whilst at Blockbuster. A further grant application for Glasgow Visual Art Scheme was rejected leaving a limited budget for the make-up artist, photographer and designer. A huge amount of goodwill was required, not just from Reichert and Ort Gallery, who works in the café when not resubmitting ACE applications; the student who helped make the film as part of a placement and of course all of the 60 participants who were involved in a Zombie Walk across Birmingham in their old uniforms, receiving food and drink and make-up tutorials for their time.

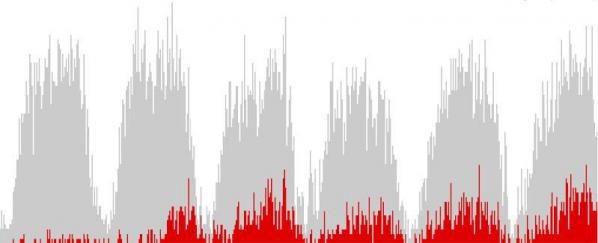

Harrison is more than well aware of paying artists and unhappy that the project was compromised on more than one occasion. The original idea about it being a realistic “data visualisation” of redundancies had to be loosened a little as they were at the whim of the number of people who showed up on the day.

60 people is a good crowd given the circumstances but only around a fifth of the number of people who would have lost their jobs from 13 stores. Despite having to cut important corners to the project’s integrity, Harrison is relieved that after two years the initial idea is a reality. The event was not only a success, but proved an alternative form of creative protest in a major UK city. The watching audience, due to the popularity of such Zombie Walks responded well, commenting on old shops and where they used to be. Harrison believes it was popular, radical and subversive, which is a hard trick to pull off.

Following a blood stained finale, the end credits have rolled. I was made redundant recently following Arts Council of Wales cuts. Harrison created Dark Days, a post-apocalyptic communal living project in Glasgow Museum of Modern Art; exhibited an immigrant friendly golf course at the Venice Biennale and continues to campaign on many fronts, including Bring Back British Rail. The High Street carries on in some form or another and Conservative vampires are sucking the life out of the UK and we all limp on, like zombies in Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, visiting the shopping mall out of habit.

In these days of austerity, it is important to reach out to the widest audience and speak outside of our own bubbles of influence. High Street Casualties isn’t about criticising what has happened, although it uses that data. It is about making more people aware of why it happened and how we may be able to affect some kind of creative change, however small. High Street Casualties deserves a sequel, a big budget reboot and should tour to every town and city, bringing gore, blood, and ripped Blockbuster uniforms to outside a multiplex near you…

Gordon Dalton is an artist, curator and writer based in Cardiff. He is currently coordinating the inaugural Plymouth Art Weekender

www.gordondalton.co.uk

twitter.com/Mermaid_Monster

Those were the words I noticed when interviewing Augmented World Expo organizer Ori Inbar several days before AWE2015, the trade show of Augmented and Virtual Reality. “We’re not in beta anymore…” Inbar said, “We now have companies implementing enterprise-scale Augmented Reality solutions, and with coming products like the Meta One and Microsoft HoloLens, the consumer market is being lined up as well.” With the addition of the UploadVR summit to AWE2015 the event was a blitz of ideas, technologies and new hardware.

AWE/Upload is a trade and industry event that also includes coverage of the arts and related cultural effects, although it is smaller when compared to the industrial aspect of the show. In this way it is similar to SIGGRAPH and this is much of my rationale for covering this, and also SIGGRAPH later this year? Doing so is as simple as McLuhan’s axiom of “The Medium is the Message” or, better yet, examining how developers and industry shape the technologies and cultural frameworks from which the artforms using these techniques emerge. The issue is that in examining emerging technologies we can not only get an idea of near-future design fictions but also the emerging culture embedded within it.

To put things in perspective, Augmented Reality art is not new, as groups like Manifest.AR have already nearly come and gone and my own group in Second Life, Second Front, is in its ninth year. Even though media artists are frequently early technology adopters, what appears to be happening at the larger scale is a critical mass that signals the acceptance of these new technologies by a larger audience. But with all emerging technologies there is drama driven by those industries’ growing pains. For AR & VR the last two years have certainly been tumultuous.

Last year’s acquisition of Oculus Rift by Facebook sent ripples through the technology community. Fortunately, unlike my upcoming example, the buyout did not eliminate the Rift from the landscape; instead it gained venture capital allowing for licensing of the technology for products like the Sony Gear VR. Also the current design fictions being distributed by Microsoft for its Hololens give tantalizing glimpses of a future “Internet of No Things” full of virtual televisions and even ghostly laptops. This was suggested in a workshop by company Meta and the short film “Sight”, in which things like televisions, clocks, and objective art might soon be the function of the visor.

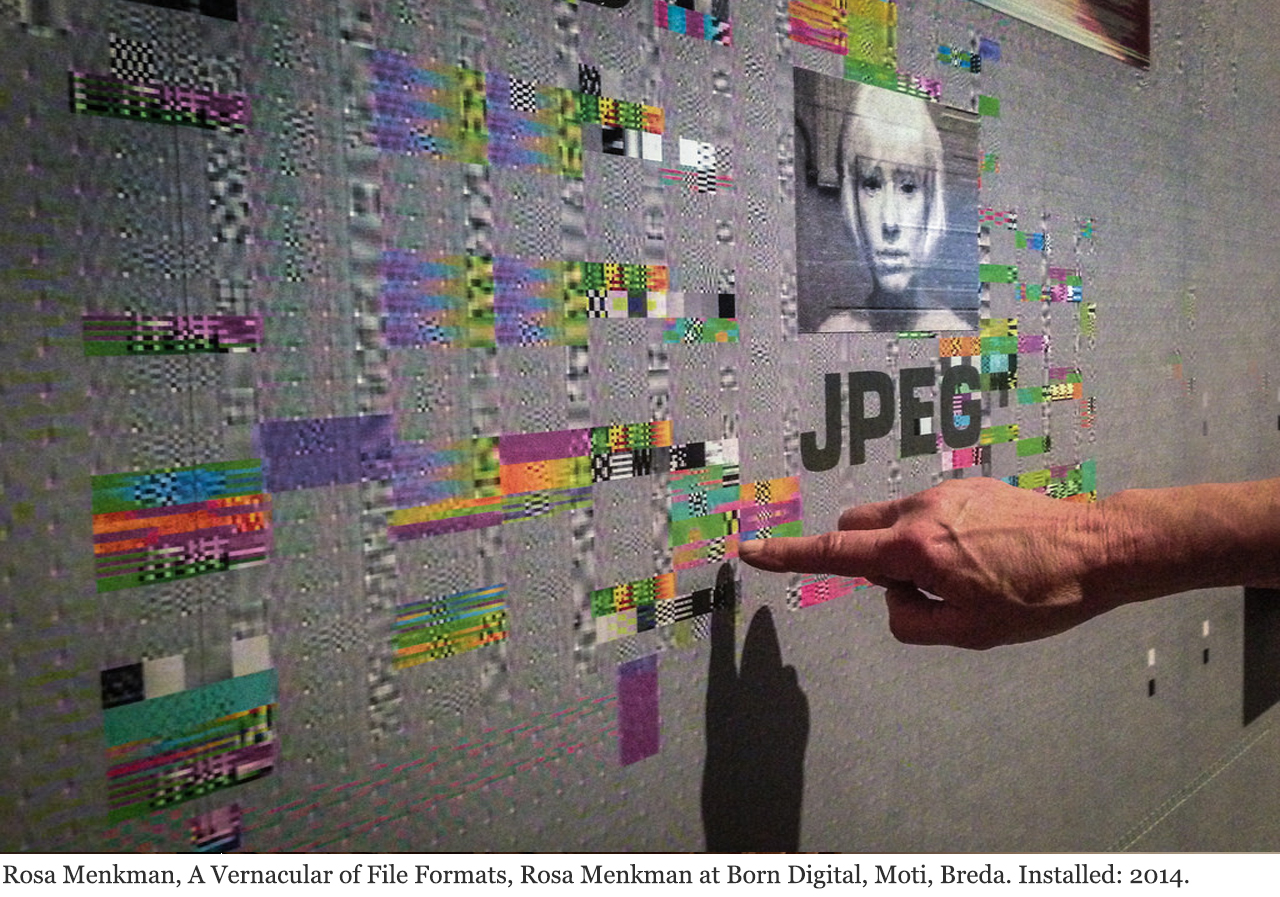

However disruptive events also happen in the evolution of technologies and their cultures. The news was that scant weeks before the conference a leading Augmented Reality Platform, Metaio, was purchased by Apple. Unlike the transparency and expansion experienced by Oculus the Mataio site merely said that no new products were being sold and cloud support would cease by December 15th. In my conversation with conference organizer Ori Inbar we agreed that this was not unexpected as Apple has been acquiring AR technologies, which has been related in rumors of “the crazy thing Apple’s been working on…”; But what was surprising was the almost immediate blackout, part of the subject of my concurrent article “Beware of the Stacks”. For entrepreneurs and cultural producers alike there is a message: Be careful of the tools you use, or your artwork (or company) could suddenly falter in days beyond your control. Imagine a painting suddenly disintegrating because a company bought out the technology of linseed oil. Although this is a poor metaphor, technological artists are dependent on technology and one can see digital media arts’ conservative reliance on Jurassic technologies like Animated GIFs for its long-term viability, but to go further I risk digression.

Another remarkable phenomenon this year was the near-assumption of the handheld as a experience device, and their use seemed almost invisible this year. What was evident was a proliferation of largely untethered headsets, ranging from the Phone-holding Google Cardboard to the Snapdragon-powered (and hot) ODG Android headset, boasting 30-degree field of view and the elimination of visible pixels. In the middle is the tethered, powerful Meta One headset with robust hand gesture recognition. Add in the conspicuously absent Microsoft Hololens and the popular design fictions of object and face recognition are emerging.

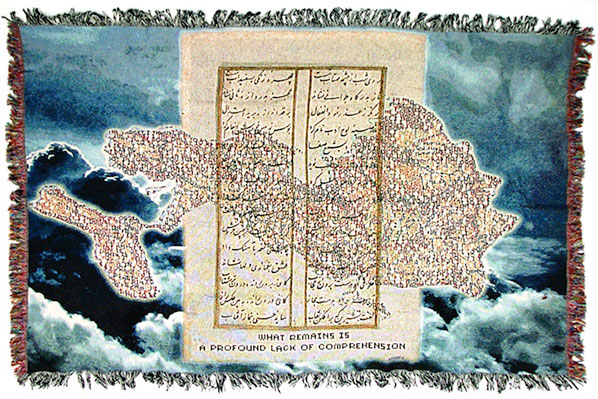

That is unless you are a brave early adopter, developer, or enterprise client. The fact that there was an entire Enterprise track and Daqri’s release of an AR-equipped construction/logistics helmet made it clear that the consumer market, much more prevalent last year, has clearly been placed in the long-term. For now, consumer/artistic AR is largely confined to the handheld device, as experienced through Will Pappenheimer’s “Proxy” at the Whitney Museum of American Art or Crayola’s “4D coloring books” in which certain colors serve as AR markers. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as an audience is likely to have a device that can run your app through which they can experience the art. As an aside, this is the reason why I chose to use handhelds for my tapestry work – imagine trying to experience a 21’ tapestry with a desktop using a 6’ cord! At this point, clarity and function, both partially dependent on computer power, have created a continuum from strapping your iPhone to your forehead like a jury-rigged Oculus for under $50, to potentially using a messenger bag with the Meta at $512, to the expensive ($2750), hot, but elegant ODG glasses you might try on if you visit the International Space Station.

While discussing the general shape of technology gives a context for its content and application, a media tool is often only as good as its app. Without meaning to show favoritism, Mark Skwarek’s NYU Lab team has been going outstanding work from a visualization of upcoming architectural developments to a surprising proof of concept for a landmine detection system, which I thought was amazing. Equally innovative was the VA-ST structured light headset for the visually impaired, which has several modes for different modes of contrast. These alternate methods not only was surprising in terms of application and possible creative uses but also changed my perception of AR as possessing photorealistic, stereoscopic overlays.

Other novel applications included National Geographic’s AR jigsaw puzzle sets, of which I saw the one outlining the history of Dynastic Egypt. I felt that if I were a kid, building the puzzle and then exploring it with AR would seem magical. There are other entertainment and experimentation platforms coming online like Skwarek, et al’s “PlayAR” AR environmental gaming system. But one platform I want to hold accountable for still being in late beta is the” LyteShot” AR laser tag system, which got an Auggie Award this year. My pleasure in the system is that the “gun” per se is Arduino-based, meaning that it could be a maker’s heaven. It uses the excellent mid-priced Epson headset, but at this time it is used primarily for status updates although there is a difference between AR and a heads-up display. So, from this perspective, it means that there are some great platforms getting into the market that are highly entertaining and innovative, but there are a few bugs to work out.

For the past thousand words or so I have been talking about the industry and applications of AR, but for me, my “soul”, if you will, set on fire during the “idea” panels and keynotes. For example, on the first day, Steve Mann, Ryan Janzen and the group at Meta had a workshop to teach attendees how to make “Veillometers” (or pixel-stick like devices to map out the infrared fields of view of surveillance cameras. Mann, famous for creating the Wearable Computing Lab at MIT and being Senior Researcher at Meta, still seemed five years ahead of the pack, which was refreshing. Another inspirational talk was given by one of the progenitors of the field, and inaugural Auggie Award for Lifetime Achievement, Tom Furness. His reflection on the history of extended reality, and his time in the US Air Force developing heads-up AR was fascinating. But what was most inspirational is that now that he is working on humane uses for augmentation systems such as warping the viewfield to assist people with Macular Degeneration. This, in my opinion, is the real potential of these technologies. In fact this array of keynotes was incredible, with Mann, Furness, the iconic HITLab’s Mark Billinghurst, and science fiction writer David Brin, (who comes off near-Libertarian) gave vast food for thought.

Every year, the Augmented World Expo gives out the “Auggie” awards for achievements in technology, art, and innovation in AR. I think it should be noted that the Auggie is probably the world’s most unique trophy, consisting of a bust that is half naked skull and half fleshed head with a Borg-like lens with baleful eye wired into that head. The Auggie is another aspect of AWE that signals that the world of Reality media is still a bit Wild West.

There are several categories from Enterprise Application to Game/Toy (LyteShot having won this year), and many of them are largely of interest strictly to developers. For example, the fact that Qualcomm’s Vuforia development environment won three years in a row gives hint to its stability in the market, and Lowe’s HoloRoom is a wonderfully strange mix between Star Trek and Home Improvement. The headset winner was CastAR, a projective/reflective technology where polarized projectors were in the headset instead of cameras, which worked amazingly well. The other winners were gratifyingly humane applications such as Child MRI Evaluation and Next for Nigeria (Best Campaign). The prizes impressed on me that the community, or part of it, “got it” in terms of the potential of AR to help the human condition, which is perhaps a “superpower” that the conference framed itself under.

Being that I am writing this for an art community it would be of interest to know where the art was in all of this. The Auggies have an Art category, as well as a gala between the end of the trade show events and the Auggie Awards. The pleasant part about AWE’s nominations for the best in AR art is that those works have integrity. Manifest.AR regular Sander Veerhof was nominated for his “Autocue”, where people with two mobile devices in a car can become the characters of famous driving dialogues (“Blues Brothers”, “Pulp Fiction”, “Harold and Kumar”). Octagon’s “History of London” is reminiscent of the National Geographic puzzles, except with far greater depth. Anita Yustisia’s beautiful “Circle of Life” paintings that were reactive to markers were on display in the auditorium but, besides a Twitter cloud and a Kinect-driven installation, the art was swamped by the size of the auditorium.

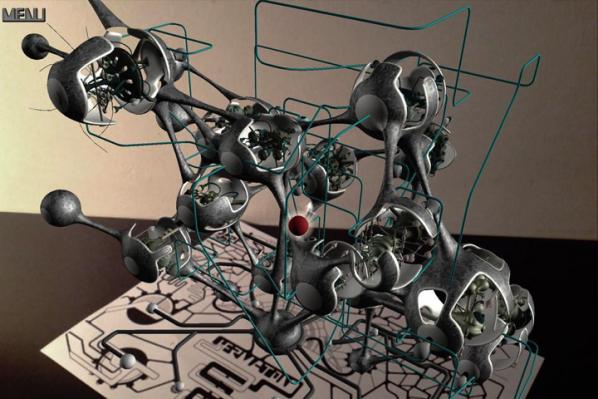

The winner of the art Auggie, Heavy & Re+Public’s’ “Consumption Cycle”, (which this writer saw at South by Southwest Interactive) was a baroquely detailed building sized mural of machinery and virtual television sets. I feel a bit of ambivalence about this work, as Heavy’s work tends to rely on spectacle. Of the lot I felt it did deserve the Auggie, purely for its execution and the effective use of spectacle. But with the emerging abilities of menuing, gesture recognition, and so on, I felt that last year’s winner, Darf Designs’ “Hermaton”, employed the potentials for AR as installation in a way that was more specific to the medium.

Yes, but it was in a much smaller area than the AR displays. There were standout technologies, like the Chinese Kickstarter-funded FOVE eye-tracking VR visor, a sensor to deliver directional sound, and Ricoh’s cute 360 degree immersive video camera. The Best in Show Auggie actually went to a VR installation, Mindride’s “Airflow”, where you are literally in a flying sling with an Oculus Rift headset. Although a little cumbersome, it was as close to the flying game in the AR design fiction short, “Sight”. So, in a way, the ideas of near-future design and beta revision culture are still driving technology as surely as the PADD on Star Trek presaged the iPad.

This year’s AWE/UploadVR event showed that reality technology is emerging strongly at the enterprise level and it’s merely a matter of time before it hits consumer culture, but it’s my contention that we’re 2-4 years out unless there’s a game changer like the Oculus for AR or if the Meta or ODG get a killer app, which is entirely possible. So, as the festival’s tagline suggests, are we ready for Superpowers for the People? It seems like we’re almost there but, like Tony Stark in the beginning, we’re still learning to operate the Iron Man suit, sort of banging around the lab.

Leave your money at home and use your personal data to buy, sell, or barter for a delicious range of commodity experiences at the MoCC Free Market. Local residents, park visitors, and online participants are invited to share how they value shopping and trading, in the street, and on their devices. In doing so, you’ll be helping us to develop a radical new artwork for exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery in September 2015. Come along to Finsbury Park and find out more.

Entrance is free on production of a MoCC loyalty card, available on arrival.

Watch out for the MoCC Roaming Marketeer to claim your reward vouchers.

Follow the event @moccofficial and find out more about online involvement.

This event is part of the research and development process for Museum of Contemporary Commodities, MoCC produced in partnership with Furtherfield, and supported by Islington Council, All Change Arts, ESRC and University of Exeter.

Add your valued commodities to Museum of Contemporary Commodities and help us test out our interaction prototype.Warm up with a Virtual Shopping trip, where you can map and discuss your trade and exchange habits with family, friends and strangers. Find out detailed information on the provenance, materials and trade-justice issues contained within your chosen commodity through a Live Chat with our expert Commodity Consultants. Upload your commodity to the MoCC database, and help curate MoCC in Finsbury Park.

A volunteer-cooked free meal, from the Edible Landscapes PACT kitchen, near to the Manor House gate. Trade your data for a free delivery of your meal, or organise your own pickup free of charge. www.ediblelandscapeslondon.org.uk (Friday only)

Discover your future through the Forebuy service. We will scientifically predict your next most urgent desire and discover in real time which affordable and amazing product is ready and waiting for you. Stop by and discover unexpected treasures from Finsbury Park surroundings whilst chatting about needs and algorithms.

Use LEGO re-creations to turn your data and commodity stories into animated gifs, whilst sharing your experiences of local trade and exchange with Finsbury Park locals.

A 3 day event for all the family to draw, make and play online games for the future of the park for the health and prosperity of all…or for total catastrophe. It’s all about the future these days. So take a drawing challenge and imagine a different future. Share your vision and see it turned into free online games to play, remix and share. Developed by Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield) and Dr Mary Flanagan (Tiltfactor) www.playyourplace.co.uk

Ever fancied your having your portrait drawn by a street artist? Go one better with our hacked scanner. A truly individualised datafication process, and a great souvenir of the Free Market! Our hacked scanner was built with advice from artist Nathaniel Stern. The stall is being run by Furtherfield artist in residence Carlos Armendariz and Amelia Suchcika. Read more here.

Browse the most up-to-date recordings, release your own records and walk away with limited edition thickear art tapes. No need to bring anything except your personal details – thickear Records Store is a one-stop-swap-shop for exploring current models of currency and exchange. An ongoing series of participation, performance and installation artworks about public transaction, which investigate economies of data exchange and consider how transactions are employed to create value. www.thickear.org

Take a quiz! Match your shopping habits to our detailed guidelines and share your results with your social network.

Park visitors of all ages… Free your office scanner and get your creative juices flowing in Finsbury Park this Summer!

Join us to build a collective portrait of Finsbury Park to be shown at Furtherfield Gallery and in an online exhibition.

With Furtherfield’s artist in residence, Carlos Armendariz, you will create intriguing images of the park with hacked scanners inspired by the Rippling Images of commissioned US artist Nathaniel Stern.

All are welcome, including children with their guardians. The workshops are free but BOOKING IS ESSENTIAL. Click here to book any of these dates:

tweet your images using #wescanfinsburypark

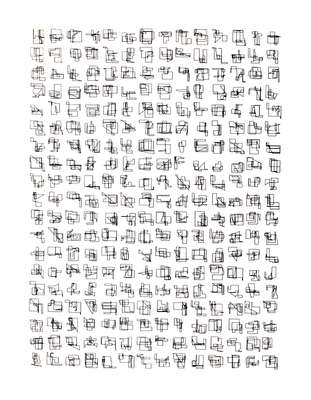

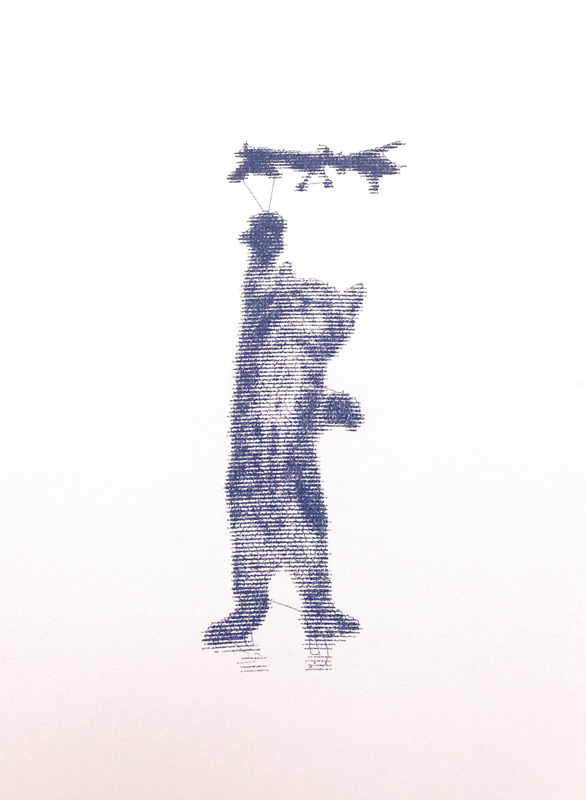

Nathaniel Stern has been using hacked desktop scanners to create beautiful images for over a decade. As part of the exhibition Beyond the Interface – London, he hung 21 large scale prints outside of the Furtherfield Gallery and produced a complete new series of images available online: Rippling Images of Finsbury Park.

Stern hacks desktops scanners to transform them in portable image capturing devices, and uses them to “perform images into existence”. This process create interesting connections between his body, the scanned environment, and their movement at the time of capturing. Stern himself explained his process in detail in his TEDx talk: Ecological Aesthetics.

Now Furtherfield Gallery is offering a series of workshops for all ages which will allow the participants to experience Stern’s artistic process. You will learn how to hack a scanner and use one of the artist’s scanners to create your own images. The goal is to create a collective portrait of Finsbury Park and there is a chance to show your work in Furtherfield Gallery.

Furtherfield in partnership with MAT PhD programme, Queen Mary University. Pictures of the workshops by Alison Ballard.

Choose Your Muse is a new series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

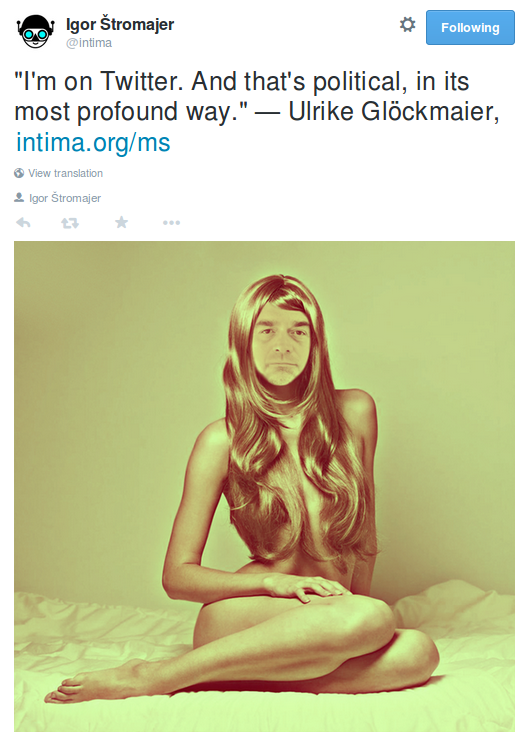

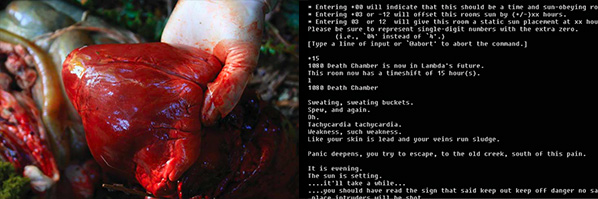

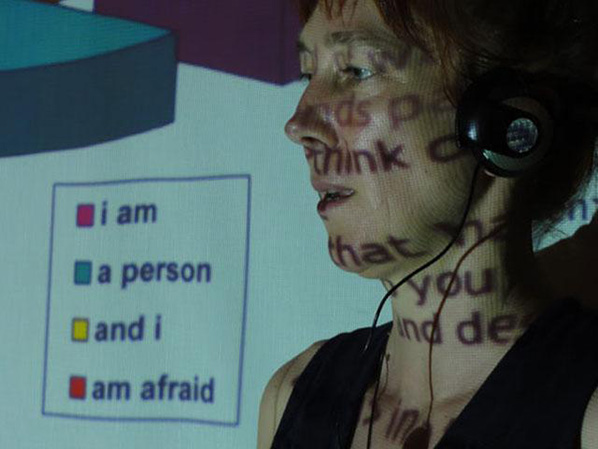

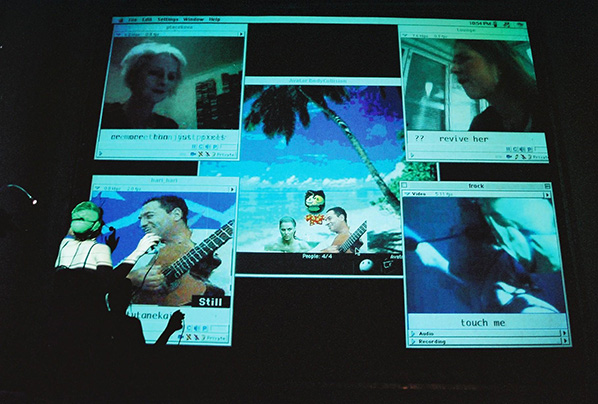

Since 1989, Igor Štromajer aka Intima has shown his media art work at more than a 130 exhibitions, festivals and biennials in 60 countries. His work has been exhibited and presented at the transmediale, ISEA, EMAF, SIGGRAPH, Ars Electronica Futurelab, V2_, IMPAKT, CYNETART, Manifesta, FILE, Stuttgarter Filmwinter, Hamburg Kunsthalle, ARCO, Microwave, Banff Centre, Les Rencontres Internationales and in numerous other galleries and museums worldwide. His works are included in the permanent collections of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the MNCA Reina Sofía in Madrid, Moderna galerija in Ljubljana, Computer Fine Arts in New York, and UGM.

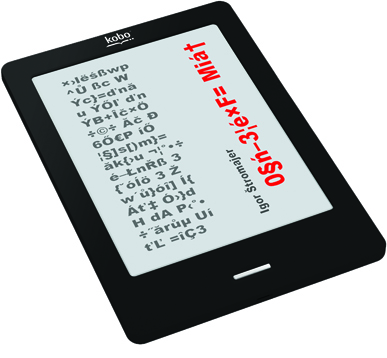

Available as:

– PDF file 0sn-3iexfemiat.pdf (2.7 MB, 206 A4 pages)

– EPUB file 0sn-3iexfemiat.epub (884 kB); Open eBook Publication Structure (Kobo etc)

– mobi file 0sn-3iexfemiat_mobi.zip (994 kB); Kindle (3 files: mobi, apnx, mbp)

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Igor Štromajer:Ajda Likar, Aleksandra Domanović, Alexei Shulgin, Ana Isaković, Andy Warhol, Angela Washko, Anne Magle, Anne Roquigny, Annie Abrahams, Annika Scharm, Antonin Artaud, Aphra Tesla, Bertolt Brecht, Bojana Kunst, Brane Zorman, Brigitte Lahaie, Carolee Schneemann, Chantal Michel, Charlotte Steibenhoff, Curt Cloninger, Diamanda Galás, Dirk Paesmans, Dragan Živadinov, Falk Grieffenhagen, Florian Schneider, Fritz Hilpert, Gabriel Delgado-López, Georges Bataille, Gertrude Stein, Gianna Michaels, Gina Spalmare, Gretta Louw, Henning Schmitz, Ida Hiršenfelder, Immanuel Kant, Italo Calvino, Ivan Jani Novak, James Joyce, Jerzy Grotowski, Jim Punk, Joan Heemskerk, Johann Sebastian Bach, John Cage, John Lennon, Jorg Immendorff, Josephine Bosma, Judith Malina, Julian Beck, Karl Marx, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Kazimir Malevich, Lars von Trier, Laurie Anderson, Laurie Bellanca, Lucille Calmel, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Luka Prinčič, Marcel Duchamp, Margarida Carvalho, Maria Winterhalter, Marie-Sophie Morel, Marina Tsvetaeva, Marisa Olson, Marjana Harcet, Marko Peljhan, Martine Neddam, Matjaž Berger, Minu Kjuder, Morena Fortuna, Nam June Paik, Nana Milčinski, Netochka Nezvanova, Nika Ločniškar, Olia Lialina, Peter Luining, Philip Glass, Ralf Hütter, Robert Görl, Robert Sakrowski, Robert Wilson, Robin Dunbar, Ronnie Sluik, Sergei Eisenstein, Simone de Beauvoir, Srečko Kosovel, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Stanley Kubrick, Suvi Solkio, Thor Magnusson, Ulrike Susanne Ottensen, Varvara Stepanova, Vesna Jevnikar, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vlado Gotvan Repnik,Vsevolod Meyerhold, Vuk Ćosić, Yevgeny Vakhtangov.

MG: How have they influenced your own practice?

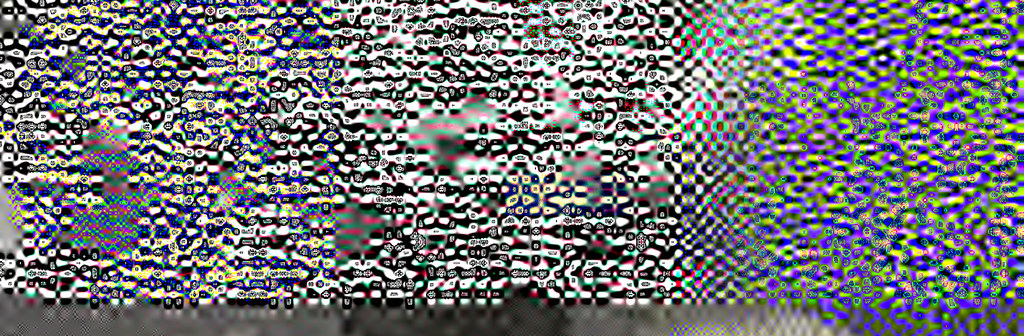

IŠ: ×›lëśßwp^Ů ßc W Ýc}=ďnău ÝŐľ ďnÝB+Îč×Ö÷©÷ Ăč Đ6Ő€P íŐ¦§]s[)m}=ăk{›u ¬¦ °•÷ é–ŁnŘ ß 3 {ˇóĺö 3 Žw´ů}óî] Í{Áť‡ Ó›}dH dA P‹° •÷˝ărůµ U흼 =îÇÉč 駝s™Ý ´Ë5˘şĄ Ű•Ż ěďu pŔ ‚Řw] bűÝ« ď}7» ú9f×Sî “•!«+q ą^őI[}vÝr«ĺn÷ Ľ ÓŰŰ Ż7Ş5g4Ť 0őÝc%ž ›Ź{ zM” ¬¦ °•÷ žl” v:i* p 4®Ú Ws›VęÖ’Fť«M˝ď{Ó¸sëÁäzç} zŻsS§NůŚńŞ%z=t{Ĺź4$ ˇ@ čТ€H) P]e †´B Ćťë®I ďwNë »DîŮ Î2P € Ă@ˇˇ ’Š ¨ iˇ+[ŔĆ 0 ŽŞ…_©2ô†YCHâAĐ ůđ ‰R!h ¨––‚)”˘!i ĆÓI KXµ …\d äPŔ t©’¤6‘ Kď ń˛ ‚ I \l ”Q,Ať „ň [ Because I have nothing to say and I’m saying it. The highest purpose is to have no purpose at all. ] ÉBÜÍ%TD IQNŔ – ¦”bbJv•M € Ä ˛-•H6•J Đspś“ Đť°Ł Ä gl @a Ä Ä cÍ‹˛ˇJ ! cĚäŠGČÄTDM L@PĐÄ ! D&Ĺ9Ť d¦¨§ó„ĚÓQ 튚 ÉC Ô$M Ö=ě ŢĘS÷…O‚ üś ^cFoŃŚ îpPÄ I@Rb bĂHhX™b 4¤i$”dwŰ ž$ .‰˘ ăóy LJSAT QI 7Ž –j(” :Ę‚jż oděG ę®h Ňáo Ăłg K÷ţk D% 9(ö¤řÜ Ľ9B Jí6ő¸n Tvôiő}@8„EO ¬¦ °•÷ bŻý!Ćńě BlÁé [řŤeÚ ‡ »Â ő˙2ľ p6Ř?¨6 Óű;7 ú3 Ś«˛ ŕ8ó ĘŐ@Ř‚˘ĹŞNÎ ž$n:vAňá Ý f ąŮ0 WżÝđ” Ł •ŻŮ vőtĽ Ďg«út’´ž W¦Ś] 0§ń–3¦é×F= ]iᆠ• „ü ¬¦ °•÷ ˙®k ŢyÚŢâ ţ ĂóJUţŮ ä …˛” 9Ů ţ˝Ó{ Ě›9ôĚŕ Š¸·fˇµÁP¸ş Dşź ´ľtÜŢ ŻŇĽ· 瀝,& ëÄŔ´DőJň% &–<VĐlŃ fű.Q |đjË DľŠ ×zr|-ú=÷8 BµÂ muŃ xĹžK ” yáüŃťdÚ°T ş ÖötË śîzl ÂI \o˝‡Ă ˇ n+„’ ¬¦ °•÷ 3 z Ŕˇ™ Úp ‘ZpĽHťĂż‹~ Ę,Ńů Šr!CćX Ěď{† –Ćľ E5‡0 Éž@ss 3 łá” 3Ďk¨nŃ×ĆëŁ ;=Š”t-ŻÓAd% [ Đ@{×űX2E , Y ŕ

Could you share with us some examples?

IŠ: ´Ą˙ pÇꯗ ž^Çš ´źw ey€©× ś˙…Ă@{ˇ\wě„á Łźhµ h÷ýŞ38ŕ 4(â‰yD @úD ®ÜÓŽŢ}” .. óDm ˙YĎă ]. B ÍT6¨S Hh…og“mS~ÍÖθŐZ» ŔťŢ¦Ř7 aŔ ”€Ł ÚKîýŚ‚ óíŃđ?Ą.±{ răö ”±D6á=ˇ Ă×Ö ď7Aą CŰś˙K ŰË&hË`Çĺ – ééërm ćÇ1ý mźŰiţIÇż–:(ěč“~śpó; žč ¦ë 0§ń–3¦é×F= Miᆠ¬¦ °•÷ ƱÝŃ |lŤé ˘ 3 OĆ VW° )»VępŇ› nŹÇŃť E—`Qt &ëú!=JŁ±`>EL ŹK Ô2 ¬¦ °•÷ CT N ö´HU ĂÎ cŽ ńű…a Q ¬¦ °•÷ QŕAĐ- ś Ý} Š*†Ľfٟʉ ŔŽ O”‡ž j xkĚ宋$w5]Ś»˙Ö]Ń€ Ôá~‹<A¸ěÂrD „»’† ( ”ń Nşţç [µ`.Ő1X¨Ź(ßżo]ťV š Ě, …ÖÜ A˙ ł Í 0§ń–3¦é×F= ]iᆠâ.Ůs_ p!VSf|r0 ě E ó÷ ·Vľ ;ń < ¬¦ °•÷ q T~ň3Ű…üTs Ínű·?Ş ©aKŠ1ŰĄkĚmąĎ;·? Ž Ź J,6 -ľŇH°¦Y˙7y= =Q _™Z Můě Uů÷I˙˙+÷…ś{÷ *Ű…¦¬ţ¬A@n8•Š •°Çč©hD ˙áď Ë Ý @=*˙ IuvÇ tčCúN™Ŕalĺ÷ ÷ě(pr °éĄ¦sÎ%¬¦ŕ «X6 ű¬ $P•M(Ô÷Ĺi%wńB [ For example, I don’t want it to be essentially the same – I want it to be exactly the same. Because the more you look at the same exact thing, the more the meaning goes away, and the better and emptier you feel. ] Ĺ1OŮŔ „6S§R4 Jú`Y¬ ÷ č«. 幀)H 28ł†Ve€@.]qT* ľ H} ¦wč¸s† Ŕ˝U}µ ô d7u•Ý’Ž H1ÓÔ z°Zý C €Z¸¦në szë Ö +° ˙˙¬˙g‹˙íö ”Ţ * úx ‚Ë®÷6l°) & b•*^ ŞTˇ@4@ Š»˙I˙>! BK °9 č Í Ő˙@®¬ń z° Ź önď» >Ş •:” ¦ś¬ RF ‚* ę¨ eR€ p€ _•”Nę ˙ű¸h) “$ŮŔ ÎBwA¬ ú ‚ĹZ`ˇHTĘ°R ť•ťA¤zçM÷ •)É ô0 ¦ îIű ®¦˙ú÷yĄ›PĐşŕŐ – »´ [RY 1Ńđ ´˛ > 3˙? } Ő” Š ’ ” fE9 ”Őnş^>Hn˙©° Ě˙JHŽş =§ÝĂ »=nMŹ€ ÷ µH Đ$K”i P ”™É 9Îos„Xô…ó ¬Ó›Pđ}7n 7 ›SOü‰ T ť)ťśďsďŤ ¬HRSc ÷ŔĆńěŐ:ëcŻ°.Ý !ůIi Ćş˘ ‚•9ú‚ ,ˇR €©]VŘ Ű• gÁ” ő™ÓŮ˝)ˇÍŐQ î©ö¨t ˇv@î@c J®‚Aä‹ß ‘j2Ű]nJ› ˘Ů…ĽŁIu•iP ^P ĆQ«I0=Ű$ń Č NtF´«@’¤ ‚z Ŕ…6 ă[ë žĂÄ îßbK Š˝śĺ ’DíŁ“ I î˘ CÁB5b ¦ÓÎ÷˘HfŞťăSęž+ßBž©ă{Ô wTw)b!ěiA¨W$ ®Xˇ– Mčp Úľc 4‡¬^ \妯 Ždzč –A H “b•lS ď ďůÍ@dsŰMP Š¬Ü”óC¬4w čĘä[Le ›}ds}ď ť ďJĹĉ°lďĹP{î ň{Şné «” &ç ś]!{ 6•µëu„H\-=Ż{3 bhŢ%F}d +Ą Śp hsmYI Ö]”Ó+ š «pŠ} 5ťŃ–é¨×pĚuä3 ĦÓ_ëóÝ=Wv´Đ§ Ý Ö×ő Žw” ŽB4ÝĐŐŘ AÉM Uˇ4DD ¸¦bÍ Ť w† ťQÄ â÷‹daÝ»––r ˛2Đ%Ŕ[I Đ Ä P}r§{z‘• cË› ×†Ş ´ °ůy TÄű*Â@^•N !ůsL z0lÉ}dIÖÝÄpJ €äíĐ Q Ś6 %Ľź÷$lv€Gócą(Ě •° ˇq¦Ŕ÷˛kčăÇ ÷§ť7 N!g ˛Mí =

MG: How different is your work different from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

IŠ: íş9č ĆW„oő lĘ pŽ3ćhŹ+¬r-ţ-AµÖ MńúćŐ6 ¬¦ °•÷ ’ ŚścՀŦ5Qe‘ďť*â@ť†v Őý vŮ ĺ ęJó]s ±1Śu @yŤ .1ş6dnµ yź]ŽuôŤ -ŻNE\± Ë9Ť}Ű č>†zž úŁř G6 𫡏 ‰ 5Ď9?:’E·xýćđ) \^Ł×ĺ(‡Bq }rM RQÓ›6 ę4_uvB´ lŰ6áH‡ { Š¬râ ´ [ Therefore I have no special message. I wish I did. It would be great if I had one. ] Qłë ©űiŇšpý–—`s§ !“9“Ř ‡łRˇ˘OÚy™9ľŻ bčw ă- -pń÷b ´ŽŇ VT oP»Őč„ ‰ ÎŘ`lăß űW §7ŞŘË caŔbýVťŘ ż‘„ć d% AK RPĐQ C ĐK, T´S Ó0T CL SăËDЉ(¨Ş*iHMŘŕ+vf?1™=QŮý̧5× +Bé:&ĘË ügŃc’µĄ (`° ‹ Ćő˝ţ9łXü ôĘČX µň ‚’Äí ¬¦ °•÷ ‰ëľ ś ň٠ߢVJfg‡!} ˛_ 2“9(ĄK! % yńNąvg ×áäěČ éżOX N ¬™ů¨ }‘« šŮ¨ óá nńxăĹ Ţo ®( ‚ Ó Oů‹Łk c ą¦( qT°€qWc 3 ćp

MG: Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

IŠ: üć»w+űe7 Ö®» y»ËăĺăTA© A¨ŽŇ‚i LY `B ż ™{d ]( !äßŰăËmńl›Y9Űí¬í3a5T @T o uf čT> 3 ^ =–vŮQ E˘¸…t0Ë î„Îy Ş{,žX×TU [ Yes. Nothing. ] ÜwŢńg&XhűÍ-…] !)+ÝĚVŕ ®ćŢĽ ¬¦ °•÷ YągŃ ]ݔ⠥@6<‹tr ¬¦ °•÷ ©±¨ Ŕ»&RŐÖQ ”% —ĆŁ{ ¬¦ °•÷ ë~ ._ć şřk ş÷© ,°–śÇoĂ›ű ýď˝ç _´p+ŚÖđ5 śZőXßÇ ň>KqĚé˙ ܇ Ę,| ©‘ ü,ź± 9»1Áµ y(m$ tÉ’ ĚÂM©Ç u˛č¨z }´s÷ĺż^

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

IŠ: Ń´j qď OĐîť% ßŰűxËýż OçżěoÓíŮËĚ˙ ő3?ôoŐĺÜ 4ň2Ëe Űą“Űżž äżôÝ ˙fAş]Ď ]Ů8ĘZ ‡“ľ _¦÷\9Á· WŰ©:jiď Ů\3ĂŮ o$ý\S|vy´ćîý úy…›¬Żę} 6m”ˇ> ‰—Đ7 Ő.™ ţľĎ§ę_WćĆw.& Ŕ·§ ~Đ 1ć ‘ ĚÇ« ¬(`¤ gőđĘĺv ţÍ ¤‚¨Ź éOŁ [ She said: “Make your own art. Do not expect me to do it for you.” ] S=•üĎVz˙ Ľ‚;z‡—xľ€J,?HóŹg¦ ľ˙ňö3ůvFĐľˇŰIa RřG A =qż?AĘ˘Ř v€D·öĂXŠ! ÷äŁ\u@U ‘ KŽ‚żB„ ŔŮQ.c‹ }9€×éĺŠ÷ů(8×Sł·¬ Y+ćĽĘ> ¨mű8°@‰%ó5 ŃĹXoňOźŔ y˙Môu ®^Dxrő áĂgwý l¬au%}‰Ě: ˙ ßČ HGPŇŃ—Dď×Ď ĎdJ› } ‘Ń@ Bu_č ôuKŘăĂóŘ ×ŠŇ(xşµ»ŐŞČ: b \[ŽAü”űđé´{ emsó|Ń‚xăö9 x: ˇoťŞřĺńta ŞĺŹË ÖŰĽŰ (:Šké í ‡Udl=Tż ‚: 3 ó]5č¦×Hsśww· ľ‰0ů t®Üqčř đ1X úI2¦ $Ýj& 3ÁśIëďą {uŐÝ

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and social change?

IŠ: °§s© ;źĆÝČ ÉůąÚ- ď]™@ Ľat•Îňc}ľ o,ú˛đ ÷Žă ÷sýqŐ«AŻ7őúWB 3 ‘ Ľ Öůxńľ ¬¦ °•÷ _µÎ ·k y·8[ ä®î¦<8}Ť4ť űfÖY †‡tŕ m۵đ [ Make love, not art. ] ź©Xrôw»´sŘîćî ¬¦ °•÷ ‡Ó‹ăHŰ˝tn ňtë+O ća¬7 TvÇĄ ż,ľ} ř[« Č< ľn

MG: Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

IŠ: With pleasure.

Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason is the key text for the understanding of everything.

BodyAnxiety.com, curated by Leah Schrager and Jennifer Chan, is the exhibition everyone would have to see in details.

Still remember Cornelia Sollfrank’s Net Art Generator? Here it is: http://net.art-generator.com

And if you already forgot everything about Jonas Lund’s exhibition in MAMA – The Fear Of Missing Out, 2013 – you need to refresh your memory: http://jonaslund.biz/works/the-fear-of-missing-out

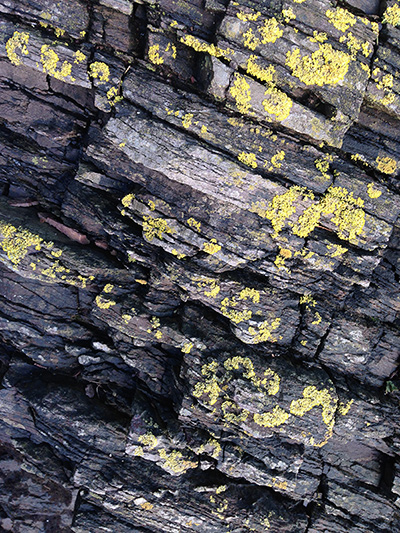

J. R. Carpenter reviews A Geology of Media, the third, final part of the media ecology-trilogy. It started with Digital Contagions: A Media Archaeology of Computer Viruses (2007) and continued with Insect Media (2010). It focuses beyond machines and technologies onto the chemistry and geological materials of media, from metals to dust.

Humans are a doubly young species — we haven’t been around for long, and we don’t live for long either. We retain a fleeting, animal sense of time. We think in terms of generations – a few before us, a few after. Beyond that… we can postulate, we can speculate, we can carbon date, but our intellectual understanding of the great age of the earth remains at odds with our sensory perception of the passage of days, seasons, and lifetimes.

The phrase ‘deep time’ was popularised by the American author John McPhee in the early 1980s. McPhee posits that we as a species may not yet have had time to evolve a conception of the abyssal eons before us: “Primordial inhibition may stand in the way. On the geologic time scale, a human lifetime is reduced to a brevity that is too inhibiting to think about. The mind blocks the information”1. Enter the creationists and climate change deniers, stage right. On 28 May 2015 the Washington Post reported that a self-professed creationist from Calgary found a 60,000-million-year-old fossil, which did nothing to dissuade him of his religious beliefs: “There’s no dates stamped on these things,” he told the local paper.2

In the late 15th-century, Leonardo Da Vinci observed fossils of shells and bones of fish embedded high in the Alps and privately mused in his notebooks that the theologians may have got their maths wrong. The notion that the earth was not mere thousands but rather many millions of years old was first put forward publicly by the Scottish physician turned natural scientist James Hutton in Theory of the Earth, a presentation made to the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1785 and published ten years later in two massive volumes3. It is critical to note that among Hutton’s closest confidants during the formulation of this work were Joseph Black, the chemist widely regarded as the discoverer of carbon dioxide, and the engineer James Watt, whose improvements to the steam engine hastened the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain. Geology emerged as a discipline on the eve of a period of such massive social, scientific, economic, political, and environmental change that it precipitated what many modern geologists, ecologists, and prominent media theorists are now categorising as a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene. As Nathan Jones recently wrote for Furtherfield: “The Anthropocene… refers to a catastrophic situation resulting from the actions of a patriarchal Western society, and the effects of masculine dominance and aggression on a global scale.”4

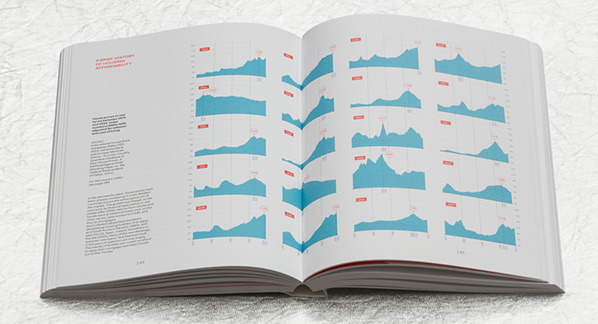

In his latest book, A Geology of Media (2015)5, Finnish media theorist Jussi Parikka turns to geology as a heuristic and highly interdisciplinary mode of thinking and doing through which to address the complex continuum between biology and technology presented by the Anthropocene. Or the Anthrobscene, as Parikka blithely quips. In putting forward geology as a methodology, a conceptual trajectory, a creative intervention, and an interrogation of the non-human, Parikka argues for a more literal understanding of ‘deep time’ in geological, mineralogical, chemical, and ecological terms. Whilst acknowledging the usefulness of the concepts of anarachaeology and varientology put forward by Siefried Zielinski in Deep Time of the Media (2008)6, Parikka calls for an even deeper time of the media — deeper in time and in deeper into the earth.

In Theory of the Earth, Hutton referred to the earth as a machine. He argued: “To acquire a general or comprehensive view of this mechanism of the globe… it is necessary to distinguish three different bodies which compose the whole. These are, a solid body of earth, an aqueous body of sea, and an elastic fluid of air.”13 Of the machine-focused German media theorists, Parikka demands – what is being left out? “What other modes of materiality deserve our attention?”7 Parikka proposes the term ‘medianatures’ — a variation on Donna Haraway’s ‘naturecultures’8 — as a term through which to address the entangled spheres and sets of practices which constitute both media and nature. Further, Parikka reintroduces aspects of Marxist materialism to Friedrich Kittler’s media materialist agenda, relentlessly re-framing the production, consumption, and disposal of hardware in environmental, political, and economic contexts, and raising critical social questions of energy consumption, labour exploitation, pollution, illness, and waste.

Drawing upon Deleuze and Guattari’s formulation of a ‘geology of morals’9, Parikka writes: “Media history conflates with earth history; the geological materials of metals and chemicals get deterritorialized from their strata and reterritorialized in machines that define our technical media culture”10. Within this geologically inflected materialism, a history of media is also a history of the social and environmental impact of the mining, selling, and consuming of coal, oil, copper, and aluminium. A history of media is also a history of research, design, fabrication, and the discovery of chemical processes and properties such as the use of gutta-percha latex for use the insulation of transatlantic submarine cables, and the extraction of silicon for use in semiconductor devices. A history of the telephone is entwined with that of the copper mine. How can we possibly think of the iPhone as more sophisticated than the land line when we that know that beneath its sleek surface – polished by aluminium dust – the iPhone runs on rare earth minerals extracted by human bodies labouring in deplorable conditions in open-pit mines?

Jussi Parikka is a professor in technological culture and aesthetics and Winchester School of Art. Although his his definition of media remains rooted in the disciplinary discourses of media studies, media theory, media history, and media art, he advocates for and indeed actively engages in an interdisciplinary approach to media theory. He cites a number of excellent examples from contemporary media art, not as illustrations of his arguments but rather as guides to his thinking. He also draws upon a wide range of other references from visual art, science, literature, psychogeography, philosophy, and politics. This overtly interdisciplinary approach to media theory provides a number of intriguing openings for readers, scholars, and practitioners in adjacent fields to consider. For example, Parikka’s evocation of Robert Smithson’s formulation of ‘abstract geology’11 in relation to land art invites further explication of the connection between land art, sculpture, and the geology of sculptural media. For thousands of years sculptors have practised a geology of media, making and shaping clay, quarrying and carving stone, and smelting, melting, and casting metal. Further, Parikka’s discussion of the pictorial content of a number of paintings in the context of this book invites the consideration of the geology of paint as a medium, entwined with the elemental materiality of cadmium, titanium, cobalt, ochre, turpentine, graphite, and lead.

Media is a concept in crisis. As it travels across scientific, artistic, and humanistic disciplines it confuses and confounds boundaries between what media is and what media does in a wide range of contexts. This confusion signposts the need for new vocabularies. If geology has taught us anything, it’s that this too will take time. In endeavouring to explain how it happens that flames sometimes shoot out through the throat of Mount Etna, the Epicurian poet Lucretius (c. 100 – c. 55 BC) wrote: “You must remember that the universe is fathomless… If you look squarely at this fact and keep it clearly before your eyes, many things will cease to strike you as miraculous.”12 So too, Parikka prods us to think big, to get past our primordial inhibitions, to look beyond mass media consumerism to what I shall call a ‘massive media’ – a conception of media operating on a global and geological scale. A Geology of Media is a green book, overtly ecological. In his call for a further materialisation of media theory through a consideration of the media of earth, sea, and air Parikka has put forward an assemblage of material practices indispensable to any discussion of the mediatic relations of the Anthropocene.

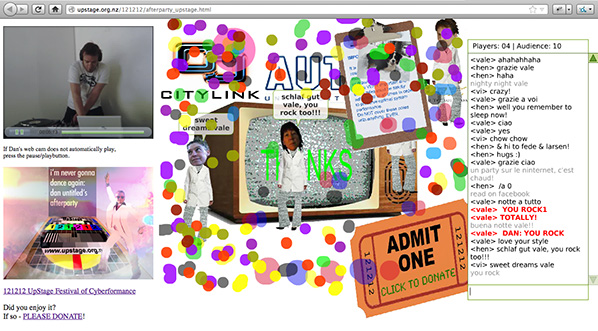

This Symposium aims to bring together a range of practitioners from the Performing Arts and theorists, including those involved with, but not limited to, dance, music, opera, theatre, magic, puppetry, and the circus. To discuss issues and opportunities in designing digital tools for communication, artistic collaboration, sharing and co-creation between artists, and between artists and actively involved creative audiences.

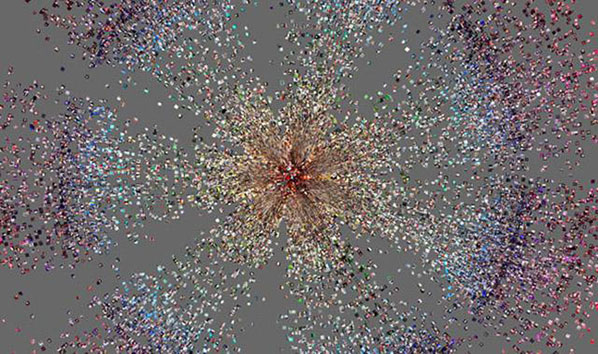

There are numerous existing online platforms that provide immediate and easy access to a vast range of tools for creative collaboration, yet their majority create and maintain networks within a ‘noisy’ social media environment, are based on a centralised model of collaboration, and are built on corporate infrastructures with well-known issues of control, identity, and surveillance.

Focusing on the Performing Arts, the symposium will take a bottom-up approach on how to design online collaborative tools without the noise of social media, drawing on peer-to-peer decentralised practices, infrastructures for building communities of interest outside the imperatives of corporate control, developing new kinds of narratives and synergies that add depth to artistic practice, blurring the distinction between artist and audience. We will discuss about what participation, collaboration, and co-creation means for the performing artists and their audiences in an online networked world and bring to the dialogue the needs, expectations, desire, aspirations and fears of working online collaboratively. We will identify, articulate and discuss artistic, social and design issues and opportunities, analyse existing projects and current practices, experiment with ideas and concepts and visual designs.

In brief, the symposium’s goals are:

The insights of this workshop will provide the base for a second, multidiscplinary workshop that will bring together performance artists and creative technologists and coders and whch will take place on the 14th July 2015 as part of the British Human-Computer Interaction conference at Lincoln, UK.

http://designdigicommons.org/http://british-hci2015.org/participation/workshops/

Walkshop, making session and drop-in day

Come for one or both sessions, or just drop in for a chat about MoCC over tea and cake.

11am-1pm – Data Walkshop with data activist Dr Alison Powell (LSE)

Explore and discuss the data surveillance processes at play in Finsbury Park through a process of rapid group ethnography. Arrive from 10.30am at Furtherfield Commons for a short introduction to the project. We will leave at 11am for a 60 minute walk around the area followed by snacks and discussion. Please bring:

BOOK HERE (places limited to 12 on a first come first served basis)

2pm-4.30pm – Making session: LEGO Re-creations & Interactive Posters

Work with Cultural Geographer Dr Ian Cook to turn your commodity stories into activist LEGO re-creations. Inspired by Nathaniel Stern’s hacked scanner, artist Carlos Armendariz will help you translate your data findings into visual events. Produce arresting images for an interactive poster for public display, then track and count its impact.

You are welcome to bring your own smart phones and computers along.

BOOK HERE

This event is part of the research and development for the Museum of Contemporary Commodities, an art and social project led by artist Paula Crutchlow (Blind Ditch) and cultural geographer Ian Cook (Univeristy of Exeter).

More info: http://www.moccguide.net/

Choose Your Muse is a new series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

Mike Stubbs became director of FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology) media arts centre, based in Liverpool in 2007, just before Liverpool’s Capital of Culture year. The centre offers a unique programme of exhibitions, film and participant-led art projects. He views the organisation as to be cutting-edge of art and new media and one of the jewels in the crown of Liverpool’s ongoing cultural renaissance.

Stubbs has worked as an advisor to the Royal Academy of Arts, The Science Musuem, London, Site Gallery, Sheffield and NESTA (National Endowment for Science Technology and Art), ACID (Australian Centre for Interactive Arts) and the Banff Centre, Canada. He has been Production Advisor to artists such as Roddy Buchannan, Luke Jerram and Louise K Wilson.

Trained at Cardiff Art College and the Royal College of Art, Stubbs’ own internationally commissioned art-work encompasses broadcast, large scale public projections and new media installation. In 2002 he exhibited at the Tate Britain, 2004 at the Baltic, Newcastle, 2006 at the Experimental Arts Foundation, Adelaide. He has received more than a dozen major international awards including 1st prizes for Cultural Quarter, at the 2003 Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial, Japan, WRO Festival, Poland 2005, Golden Pheonix, Monte Negro Media Art Fest 2006. In 2003 he was awarded a Banff, Fleck Fellowship.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Mike Stubbs: Uncle Islwyn Thomas (deceased) who told a barman to bugger off in Welsh for not serving us (age 14) – It made me realise one could object.

David Nash. I was lucky to have a chance visit to his studio (chapel) when I worked in Llechwedd Slate Mine Craft shop, Blaenau Ffestiniog. He persuaded to save up for a Kawaskai Z650 in the future and not to be a paint sprayer and instead, go to art college (circa 1976…), and that being an artist was a viable alternative.

And Krzysztof Wodiczko, I saw his Cruise Missile projected on Nelsons Column in 1985 and then him swivel the projector and project a swastika onto the south african embassy in response to Margaret Thatcher donating £7 million quid to PK Botha government – big slap in the face to the anit-apartheid movement of which I was part (Greetings From the Cape of Good Hope can be found here, http://mikestubbsco.ipage.com/artworks.html)

MG: How does your work compare to those who’ve influenced you, and what do you think the reasons are for these differences?

MS: With age I’ve tempered the urge to object to too much and post election, I feel like I’m from another planet. Workwise, I’ve been priviledged and lucky to build support within the public sector for arts organisations which have maintained some edge (Hull Time Based Arts, ACMI, FACT). Recently very proud to have produced Group Therapy, Mental Distress in a Digital Age, which is both critical and a form of social activisim. I am lucky to have collaborated in developing festivals including : ROOT and the AND (Abandon Normal Devices) which have created more room to commission and present a risk taking program.

MG: Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

MS: That longer term agendas might accept that risk and experiment are needed and that Art IS innovation and that more people from non-art backgrounds get a chance to experience and make art.

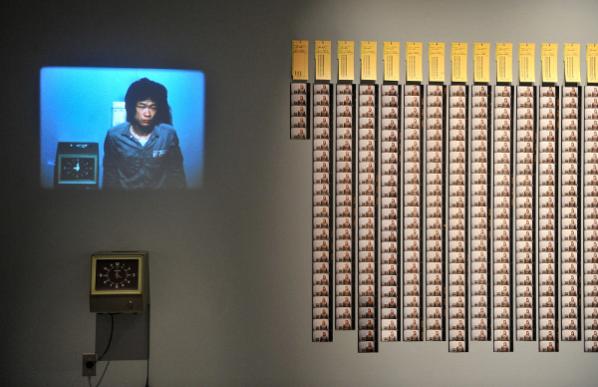

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

MS: Watching on TV a flood victim being rescued by helcopter and dropping her entire belongings. And Hseih Teching’s One Year Performance.

“Tehching Hsieh’s work, informed through a period spent in New York City without a visa, experiments with time. He was actively ‘wasting his time’ by setting up a stringent set of conditions within five different year-long performances. The driving force for an individual to perform such extreme actions must surely be the ultimate cipher for being emotionally, psychologically touched – and that, ultimately, is a gift. His work poses the question: as humans how can we afford not to be touched?” [1]

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and social change?

MS: Do what you feel like. Dont copy others

MG: Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

MS: Post-humous papers Robert Musil, they continuously speak to me at the most fundamental level and with wit. http://bit.ly/1PYIq6A

Diamond Age Neal Stephenson. Inspired the idea of democratising interactive media. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Diamond_Age

Art of Experience John Dewey, a bible of ideas to re-frame arts and culture – first citing the term ‘impulsion’ – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_as_Experience

The City and the City, China Meilville. It inspired our exhibition Science Fiction, New Death at FACT. It elegantly suggests how we simultanesouly occupy the same political, social and physical spaces despite difference.

Featured: Toast McFarland

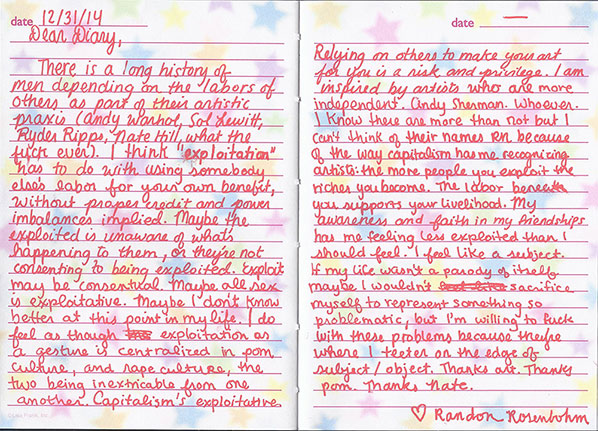

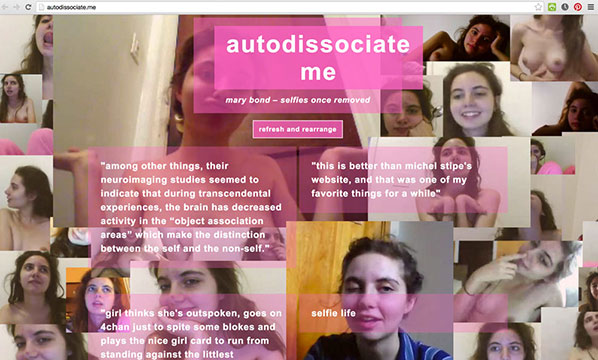

Synthetic bodies, mediated selves. What themes become relevant in a technoprogressive world – as objects proliferate, what do the inundated people talk about?

You are alone, at a computer. You talk to people but they are not around. There is no bar, no village square, no space in which you speak. There is your device and your physical presence. The social location is your body and its interface with the communicative device. What is the language for landscapes which can’t be seen, and yet which predicate subjectivity?

You express yourself. You are certain state statistics, a resume, you are a myspace profile long defunct. We require your legal name. Certain cards, from when you were born, from when you became qualified to drive, define you, make or break you. You are an ok person provided your paperwork is in order – morality is preceded by bureaucracy.

What’s the relationship between a legitimated self and that person’s body? The more modes of documentation we have the greater possibility for fictional aberration. The disparities between someone’s situated life and the records which make up their memory proliferate.

The image above by artist Toast McFarland was taken in a cartoon world. It is a selfie, a socially streamed validation of presence, but it is also a meticulous reframing of that practice. Everything is subtle, deceptively common, and yet the composition is entirely irreal. Flat colours, almost abstractly plain costuming, this is what happens when a vector world invades your computer room. It exists between personal expression and the self as actor within the surreal.

Leah Schrager‘s modelling-inspired self-portraits covered over with bright streams of paint. The model image professionalizes the act of self-representation in image form. In the profession there are industry demands – self-validation may be about confidence and friendship, where industrial success might tend towards epitomization and abstraction. Are you a good model – do you meet the sexual and aesthetic demands of the collective consumer unconscious? Schrager’s work combines a toying with such psychological implications with a background in their material underpinnings – the body in dance, the body in biological study. This combination allows for work and commentary that penetrates the relationship between the vessel you are indelibly given and the psychological relationship it develops mediated for oneself and a public.

Do you view Schrager’s images out of an interest for her or for the type of beauty she represents? Once the image is painted over, is there any interest left? Through different personas, she delivers these in a variety of web contexts, each time asking us to reconsider who we’re looking at, and who we are to look.

Screens, correspondents, professional speakers. We are happy to take your call. These two screenshots are taken from two videos by media artist Aoife Dunne. Both combine a juxtaposition of found broadcast footage, the enveloping commercial TV world, and her own crafted filming sound stages. They are installations, videos, and imagist combinations that take our question of the self directly to the media world. In the second, Dunne acts directly over top found footage, performing as doppelganger of the telemarketer in the projection. Her simultaneously comic, retro and coolly provocative aesthetic places her into an 80s infomercial dream world. She acts her own fiction, the selfie is the superlative thought experiment, and yet the proliferation of doubles buries her subjectivity in an imagined space of marketed image sheen. In the first work we only have a double, and Schrager’s biological world is fleshed out and externalized. This is what you really look like. Dunne’s own medicalized outfit says that this telecommunication is also a biological translation. For your image, we need your face, but for your face, we need organs and cells. Between the public and economic demands of the screen, and the material demands of your body, where are you?

Dafna Ganani‘s work, through a combination of images, code, social internet art and theoretical reflection, gives us an exemplar of how self-representation meets technical distortion. Her own performative presence proliferates in her work, yet always accompanied by animations, entire interactive worlds complicating any personal space. In this image, self-reflection is directly addressed – at first glance it mirrors what is represented but on closer inspection nothing of what that would look like quite match up. Where are the dragon head things located, where is she, before and after mirroring – the almost comical comparison is undermined by a disquieting sincerity. She appears intent on knowing where she is, however much the dragon doesn’t have her best interests in mind. And the right hand, reaching into the animation cloud on the left, nowhere to be seen on the right.

Dunne’s world of media culture screens is made specific and celebratory in Georges Jacotey‘s self-portraiture as Lana del Ray. An internet performance artist whose work explores media culture and self-image, the picture’s combination is both nearly seemless and parodically collaged. We all participate on some level in commercial culture, but we can never admit it. We might genuinely like aspects of it, we might hate aspects – but the popular bent of this culture means that as long as it is pleasing to a common consumer base it will gain a cultural existence. You know so much about iconic entertainers you never asked to know about. Jacotey takes on this conundrum, joins in on it, participates – what if instead of merely liking a celebrity, you seek to emulate and become them? Some people like del Ray’s albums, Jacotey’s the one who sang them. Capitalism asks that you buy, what if you take the role to sell? Human images make for great products, before we make the necessary transactions let’s make sure we know how to transform ourselves into them.

Good self-representation requires good media savvy. Before you think about your online identity simplify the process by becoming a celebrity. They’ve already figured out all the questions of the self in society – the right names, dress, mannerisms, the right look. Everything is acceptable, everything is inspiring, nothing is quite familiar.

Rafia Santana further draws out Jacotey’s comparison of the celebrity image and the selfie. Two different trajectories are taken up here – one is to deconstruct the fictions of the “real celebrity image”. The second is to fictionalize and play with one’s own portrayal. The result is layered, offering multiple points of entry for both observation and critique. If the digital image is just bits and bytes, what happens to ethnic history, to situated lives and experience? Putting herself repeatedly in her own work, Santana asks the basic question at hand – what, in re-representation, am I? And, with Jacotey, she probes the obverse of media celebrity existence and identification. If I like a celebrity, am I participating at all in their imagery or life? If so, in what way – what right to I have to their life, or in turn, what right do they have to be omnipresent in mine?

Subjectivity is the sentence, objects the fetish – be sure to glamour up.

Be sure to dress things up so you can recognize them well. Try not to mix up hair with noses, and composure with distortion. Each act of mediation further twists and reinvents our own images. You thought you knew where your lips were, what your skin looked like, but everything that goes through the machine comes out different, strange. It’s not a human, it’s a landscape. There’s an eye at the top, but you have no idea what it’s for. In the work of Sam Rolfes, the self is almost abstract, technical distortions take over any recognizable vestige of a human. Technique is everything, humanity nothing.

The self is painted, photographed, symbolized. It’s not a live image on the phone. Sometimes people in canvases try to get out. There are a few people here, all the same, that have nothing to do with one another. In Carla Gannis‘ selfie series, we return to a cartoon realism – but this time with a few added mirrors. Is the skull in the background also her? What is that a memento of?

Death in the image, life in its reproduction. You are now invisible, but we know more about what you look like than ever. Technological proliferation upends and eliminates traditional context but can never efface bodies and their identities. Indeed its societal saturation emphasizes these presences, their inevitability and all their embodied ties that digitize incompletely.

These practices work to situate the self, the body. Physiological maps are now more important than ever – they give us the image of the virtual. Mythology says we are in an immaterial age, that humans are obsolete and will be succeeded by machines. Reality says something far more disturbing – that our own materiality is the means of that obsolescence.

In partnership with The Arts Catalyst.

‘Living Assemblies’ is a hands-on workshop, led by designer and researcher Veronica Ranner, investigating the coupling of the biological material silk, with digital technologies. This workshop is organised by The Arts Catalyst in cooperation with Furtherfield.

We invite participants (experts in their own field – artists, designers, scientists, writers, technologists, academics, and activists) to join a weekend-long workshop, in which we will experiment with silk and a range of transient materials to imagine potential future applications for combining biological and digital media.

Traditional methods of crafting silk have barely changed in 5000 years, but recent explorations by scientists are uncovering extraordinary new potential uses for this material. Reverse engineered silk is one of the few biomaterials not rejected by the human body. Rather, able to be fully absorbed by human tissue, it allows for a range of applications within and interacting with the body, including human bone and tissue replacements, biosensors and biodegradable electronics, opening the potential to imagine new wearables and implantables with a range of functions.

During this two-day workshop, participants will collaboratively explore the potential of reverse engineered silk, currently confined to laboratories. Taking the body as the first site for investigation, Veronica will ask participants to consider themselves as living assemblies that can be hacked, enhanced, and patched into using bio-digital materials. Activities will involve material experiments combined with a narrative design process to speculate on silk’s possible future use in the world.

DAY 1

With Veronica Ranner, Clemens Winkler and Luke Franzke, participants will be introduced to transient materials — such as reversed engineered silk — through hands-on experimentation with a range of materials, including agar-agar, gelatine, fibroin, glucose and silk-fibres. They will use digital methods and circuits and combine them with silken materials, to then begin forming their own ideas into speculative objects and artworks.

DAY 2

Innovator, scientist and intermedia artist, Gjino Sutic will introduce the concept of ‘bio-tweaking’: improving and hacking living organisms, for example through metabolism hacking, neuro-tweaking, tissue engineering and organ growing. Participants will work together with science writer Frank Swain to construct narratives around their work. In the final session, participants will map out their ideas in discussion with the group.

If you would like to attend the 2-day workshop please send a statement of no more than 100 words and explain why you would like to attend and a brief summary of your background.

Deadline: 5pm, 18 May 2015

Please email: admin@artscatalyst.org

**Participants must be able to attend the full 2 day workshop**

**Please note spaces are limited**

Participants are encouraged to bring their own laptops, inspirational materials, tablets and cameras along, to enrich the tool set for story crafting.

Veronica Ranner is a designer, artist and researcher living and working in London. She researches the burgeoning domain of the bio–digital — a converging knowledge space where digitality and computational thinking meet biological matter. She dissects and creates tangible and immaterial manifestations of such collisions, examining hereby the polyphonic potential of alternative technological futures. Her current doctoral work explores paradigm shifts in reality perception by coupling speculative (bio)material strategies and information experience through design research. Veronica holds a degree in Industrial Design from Pforzheim University, a Masters in Design Interactions (RCA), and has worked trans-disciplinary with a variety of science institutions and biomedical companies, and she teaches and lectures internationally. Her work is exhibited internationally, including at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem (2012), Science Gallery, Dublin (2012), China Technology Museum, Beijing (2012), Ventura Lambrate, Milan (2013) and French Design Biennale, St. Etienne (2013). She is currently pursuing a PhD at the Royal College of Art’s Information Experience Design programme and is interested in complex networked cycles, emerging (bio-) technologies and biological fabrication, systems design, material futures and new roles for designers.

Clemens Winkler, designer and researcher at the Zurich University of the Arts, Switzerland.

Luke Franzke, designer and researcher at the Zurich University of the Arts, Switzerland.

Frank Swain, science writer and journalist.

Gjino Sutic, innovator, scientist and artist; Director of the Universal Institute in Zagreb, Croatia.

Other experts joining discussions during the workshops will be Bio-informatician Dr Derek Huntley (Imperial College).

The project is a collaboration between The Creative Exchange Hub at the Royal College of Art, Tufts University (Boston, MA), The Arts Catalyst (London), and Imperial College (London), and hosted and in collaboration with Furtherfield (London). The project is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

With Virginia Barratt, Francesca da Rimini, Cory Doctorow, Shu Lea Cheang, Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc, Andrew McKenzie, Angela Oguntala, Dr. Richard Stallman, Stelarc, Jacob Wamberg, Lu Yang

Inspired by the Phillip K Dick short story “The Electric Ant” this year’s CLICK seminar curated with Furtherfield explores how identity and perceptions of reality have changed in a world where humans, society and technology have merged in unexpected ways. Who are we, what’s real, where can we expect to go from here, and how can we get there together?

From future shock to FOMO (fear of missing out), accelerating technological change has disrupted our perception of ourselves and the world around us. Pervasive computing, genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, drones and robotics, neural interfaces and implants, 3D printing, nanotechnology, big data and ever more technologies are redrawing the boundaries of what it means to be human and what it means to be you.

At the same time the design and unintended consequences of technology are creating new mass behaviours. And the productive forces of social media, peer production, hacker culture and maker culture are creating new possibilities for creation and expression. All of this changes how we relate to one another within society as part of the public.

This years CLICK festival, co-curated by Furtherfield sets out to explore questions related to identity and perceptions of reality in a world where humans and technology have merged in unexpected ways.

Virginia Barratt. VNS Matrix founder, cyberfeminist, Virginia Barratt is a PhD candidate at the University of Western Sydney in experimental poetics. Her doctoral topic is panic, engaging tensions between ontological meltdown/psychic deterritorialisation and ontological security. Panic is remediated from its pathological narrative and reimagined as a space of urgency/agency from which to act. Her work of performative text, SLICE, is forthcoming from Stein and Wilde.

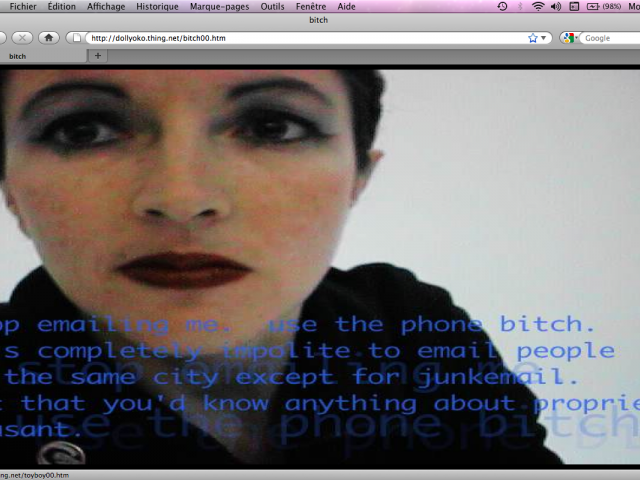

Francesca da Rimini explores the poetic and political possibilities of internet-enabled communication, collaborative experimentation and (tel)embodied experiences through projects such as her award-winning dollspace. As cyberfeminist VNS Matrix member she inserted slimy interfaces into Big Daddy Mainframe’s databanks, perturbing the (gendered) techno status quo. Her doctoral thesis at the University of Technology Sydney investigated cultural activism projects seeding radical imaginations in Jamaica, Hong Kong and the UK. A co-authored book, Disorder and the Disinformation Society: The Social Dynamics of Information, Networks and Software, will be out in May 2015.

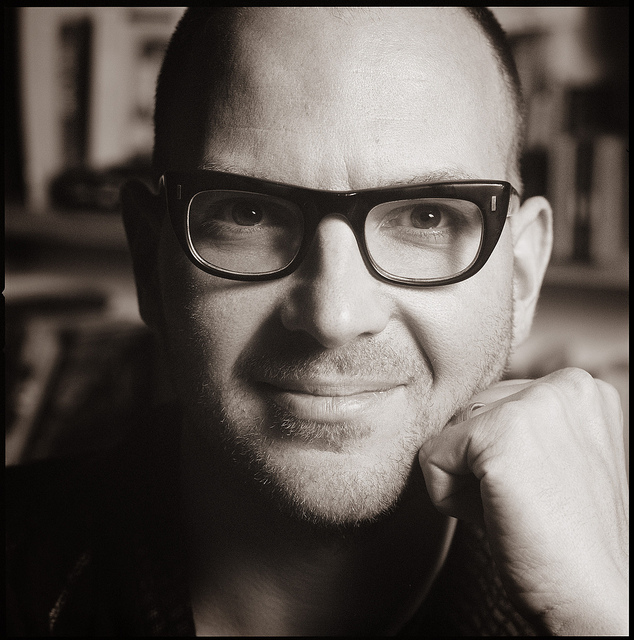

Cory Doctorow is assigned the label Internet philosopher, who writes, blogs and debates about online rights. Doctorow is convinced that copyright is an out-dated idea that damages the Internet and criminalizes peoples’ online actions improperly. According to Doctorow the current regulations of copyrights are obsolete by the unstoppable copy machine we call the Internet, which continues to produce samples of available online material such as pictures, music and text. Cory Doctorow is also an award-winning science fiction author and co-editor at boingboing.net.

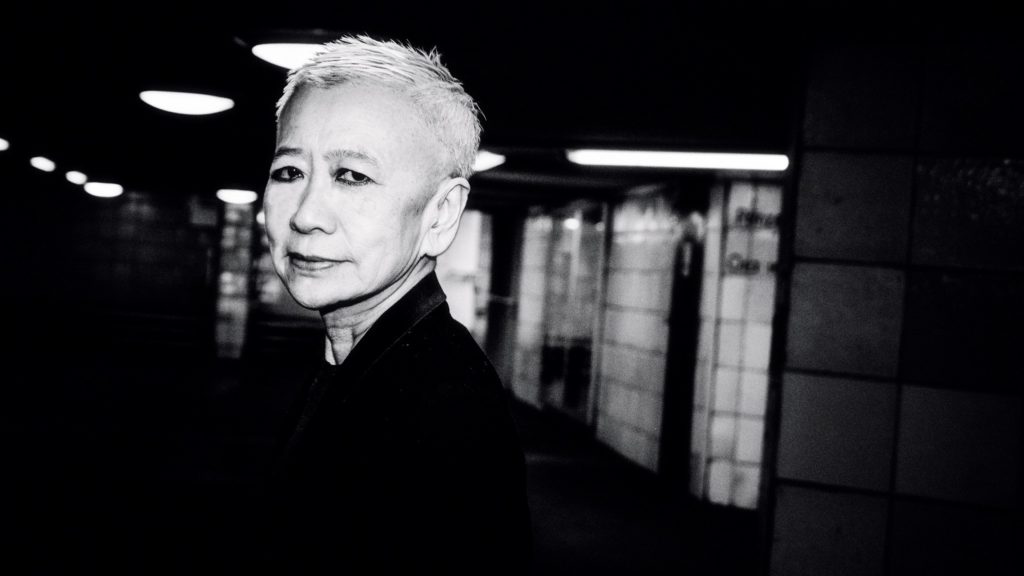

Shu Lea Cheang is known for her pioneering work in the field of media art and she is a true multidisciplinary and activist artist whose work spans from film to net art and performance (online, and in galleries) and video installation. Beginning the 1981 she was involved in the media activist’ collective ‘Paper Tiger TV’. Among her important multimedia works is the ‘Brandon Project’ (1998-99). Guggenheim Museum’s first official engagement with the then-emerging medium of internet art and one of the first works of this medium commissioned by a major institution. Following the production of the cyber porn film ‘I.K.U.’ (2000)(first porn film to be shown at the Sundance Festival) she focused on questions of copyrights and economy in media culture. Shu Lea Cheang holds a BA in history from the National Taiwan University, and a MA in film studies from New York University.

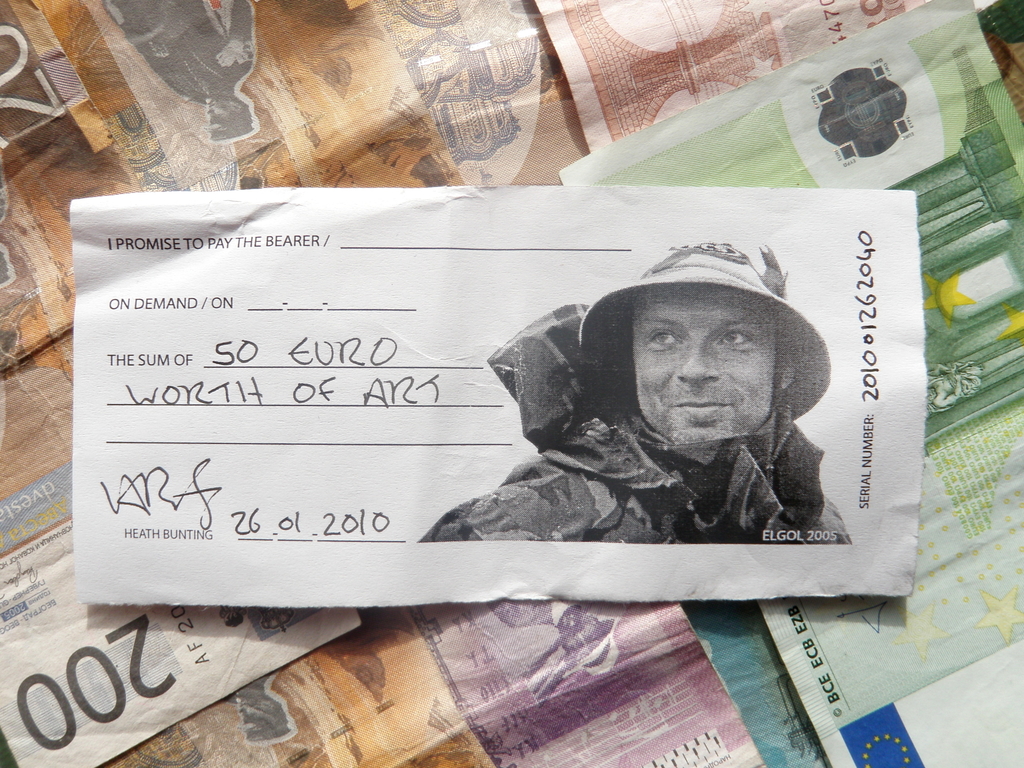

Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc (US). In a world before the Internet – information, transmission and dissemination was a controlled and regulated endeavour. The advent of the information superhighway, which is currently littered with social media sites run by billion dollar corporations, has blurred the lines of community ownership of one’s personal information and the individual. By incorporating herself she effectively wrestled the control of her digital self, back from corporations and took an active role in the sale of her information. Morone has been motivated by an underlying fascination with the relationship between technology, human beings, and the socio-economic political implications the melding of the two produce. That social concern, spurned Jennifer to create Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc.

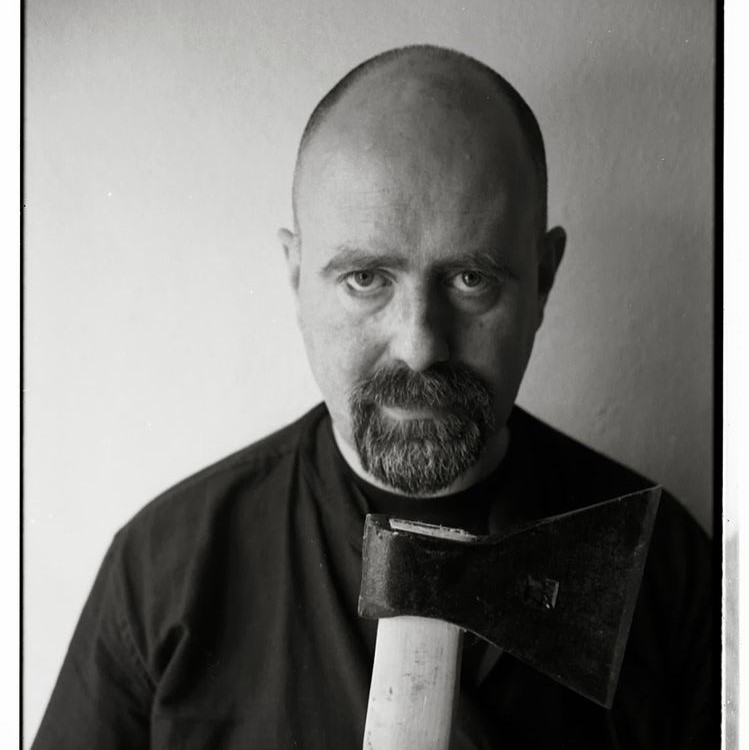

Andrew McKenzie (UK). The British Andrew McKenzie is the core of The Hafler Trio. His professional career began more than 3 decades ago and through the years he has worked with different professions such as audio designer, psychotherapist, hypnotherapist and workshop leader in Creative Thinking. McKenzie is also co-founder of Simply Superior where he teach creative processes that challenge the way you think in order to make you realize what you know, and are aware of not knowing. McKenzie’s projects and present goals all involve applying everything learned by experience over the last 48 years for the benefit of other. Andrew McKenzie defines himself as a mood engineer, specializing in changing people’s lives.

Angela Oguntala (US/DK) is a designer whose work sits at the intersection of technology, design, and futures studies. Currently, she heads up an innovation lab for Danish designer Eskild Hansen, envisioning and developing future focused products and scenarios. In 2014, she was chosen by a panel consisting of the United Nations ICT agency, Ars Electronica, and Hakuhodo (Japan) as one of the Future Innovators for the Future Innovators Summit at Ars Electronica – called on to give talks, exhibit her work, and collaborate on the theme ‘what it takes to change the future’.

Dr. Richard Stallman launched the free software movement in 1983 and started the development of the GNU operating system (see www.gnu.org) in 1984. GNU is free software: everyone has the freedom to copy it and redistribute it, with or without changes. The GNU/Linux system, basically the GNU operating system with Linux added, is used on tens of millions of computers today. Stallman has received the ACM Grace Hopper Award, a MacArthur Foundation fellowship, the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Pioneer Award, and the Takeda Award for Social/Economic Betterment, as well a several doctorates honoris causa, and has been inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame in 2013.

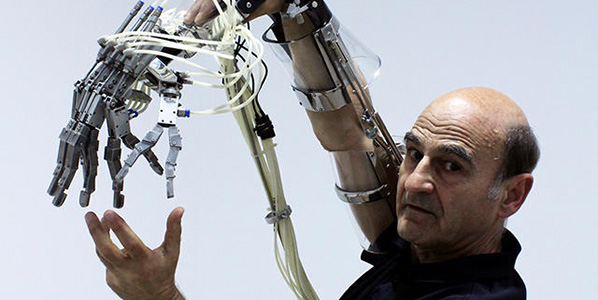

Stelarc (AU). An extra ear. A third arm. Six legs. A walking head. The Australian performance artist Stelarc is questioning and challenging whether or not it is possible to optimize the abilities of the human body. Stelarc has since the 1960s not hesitated to include advanced technology in his projects. After having examined several test on his own body, he announce a manifest claiming that the human body is out-dated and no longer meets the information society we live in. Stelarc uses his artwork to convey how the human body hypothetically will appear in the nearest future, if the technology is considered an extra dimension to the evolution.

Jacob Wamberg, Professor of Art History at Aarhus University. Principal Investigator for Posthuman Aesthetics. In the posthuman field, he has co-edited The Posthuman Condition: Ethics, Aesthetics and Politics of Biotechnological Challenges (2010) with Mads Rosendahl Thomsen et al., and is now working on tracing the early contours of the posthuman paradigm (ca. 1900-1930), focusing on Dada, Futurism and Functionalism.

Shanghai based artist Lu Yang utilize a range of mediums known from pop culture such as Japanese manga and anime, online gaming, and sci-fi. She mixes these with discourses of neuroscience, biology, and religion, when she asks what it means to be human in the 21st century. Her depictions of the body, death, disease, neurological constructs, sexuality/asexuality, gender is unsentimental, confrontational and in their morbid humor not for the squeamish. Lu Yang is one of the most influential Chinese contemporary artists rising at the moment. She is a graduate from the China Academy of Art New Media. Her work has the last couple of years been internationally shown at museums and galleries and she has in 2014 been residency at AACC in New York and Symbiotica in Australia.

Please visit the CLICK website to purchase your ticket.

Ticket: 350 DKK. / Student: 250 DKK.

Explore and discuss the data surveillance processes at play in Finsbury Park through a process of rapid group ethnography. Arrive from 5.30pm at Furtherfield Commons, the community lab space in Finsbury Park, for a short introduction to the project. We will leave at 6pm for a 90 minute walk around the area followed by food and discussion.

Please bring:

This walkshop event is part of the research and development for the Museum of Contemporary Commodities.

The telluro-geo-psycho-modulator is the latest experiment in a series of playful explorations and elaborations of a general thesis extracted from the neuroscientist Michael Persinger’s work, that our brain states are modulated by the interference patterns created by our immersion in natural weak geomagnetic fields, and that such patterns cause the feeling of “anomalous experiences” including those of ghosts or god.

The workshop aims to begin equipping participants with a method to explore such potentialities between the earth and our psyches through the construction of an experimental interface (developed with Martin Howse).

A short introduction (20 min) to participants will briefly cover the theory of weak geo-magnetic field effects on psyche, including demonstrating an entirely synthetic electronic amplifier/helmet configuration. This will ground participants in both the practical and playful nature of the project.

The brain is electro-chemical, and the existence of fundamental commonalities between all 7 billion human brains by which a similar physical stimulus can affect them is not a new concept – however, this workshop tests the idea that it is the induction by very low electromagnetic fields that disrupt a sense of self through the creation of anomalous experiences.

In the workshop particpants will build a simple circuit with which to test this thesis by connecting the earth’s telluric currents directly to our brains. On the second day we will then test the circuits outdoors in Epping Forest.

During the workshop and field trip participants will build electronic circuits and hand wind copper coils to construct:

The workshop is estimated to take around 4-6 hours for around 8 or so participants. All materials are supplied, however if participants have a soldering iron, please bring it along.

Each participant is asked to pay £15. This is to cover material costs – participants get to keep their circuits which can also be used with other circuits (eg. audio).

Featured image: By Instagram users lynellspencer and banditqueen555

I’ve been thinking about the idea of home a lot recently. I’ve been traveling over three continents for the last 6 months, living out of hostels, surfing friend’s couches, and even staying in local homes through Couchsurfing or personal connections. In terms of my home, I’ve grown comfortable with no privacy, sleeping in a room of strangers with only a tiny locked box for security. While I knew in my head the contemporary home is always shifting, I didn’t start considering the impact of that until my own housing situation became so erratic.