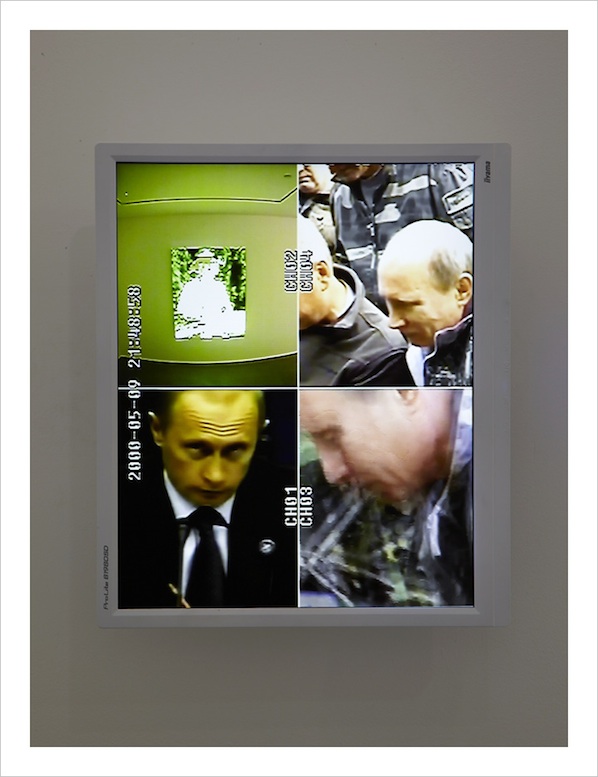

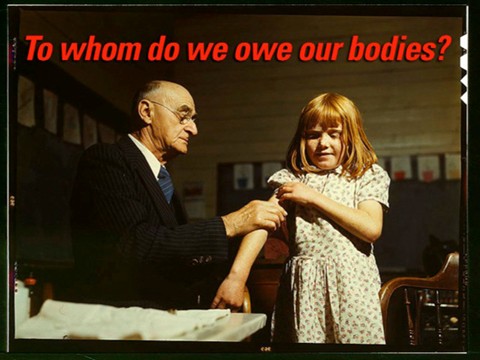

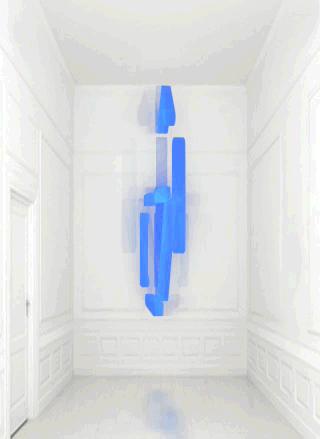

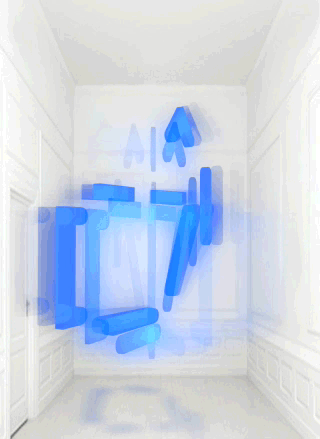

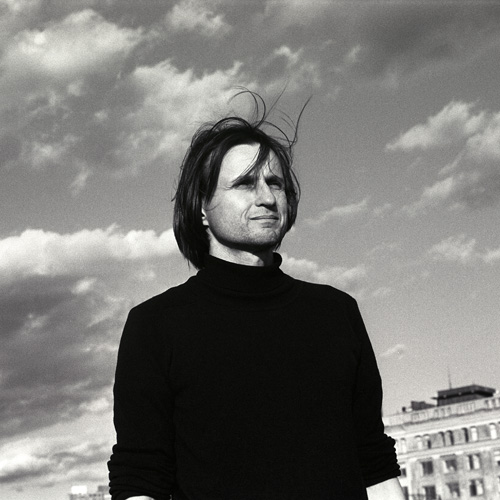

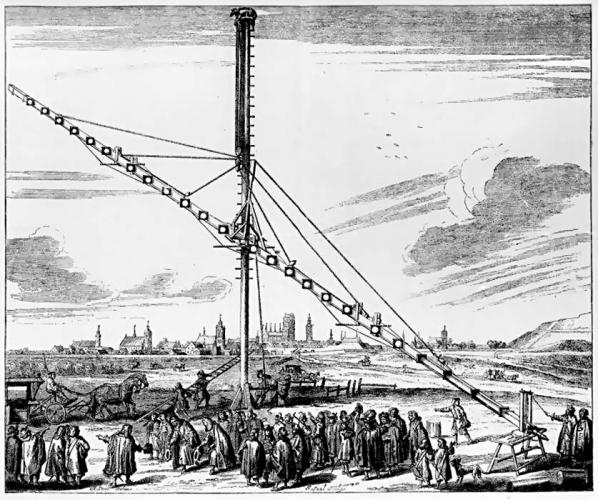

Featured image: UBERMORGEN, CCTV, A Parallel Universe, (2013)

Rachel Falconer’s article is written in response to an interview conducted with lizvlx and Hans Bernhard from Ubermorgen. ‘userunfriendly’ is their first solo exhibition in London and presents a performative study of creeping paranoia. It is on show at Caroll/Fletcher Gallery through October until 16th November 2013.

“You one of those right wing nut outfits?” inquired the diplomatic Metzger. Fallopian twinkled. “They accuse us of being paranoids.” “They?” inquired Metzger, twinkling also. “Us?” asked Oedipa. The Crying of Lot 49 [1]

The Edward Snowden soap opera is far from over as the media and social commentators continue to perform a one-way polylogue with the absconded, muted Snowden. The furore and essentialist reactions directed towards Snowden, the latest in a burgeoning breed of leaky information gatekeepers, has resulted in a pervading sense of neuroses creeping across the digital commons. One of the many media stunts to emerge from this backdrop of encroaching paranoia was Kevin Poulsen’s encrypted open letter to Snowden on the Wired website [2] . With the theatrical opening gambit of: “Don’t read this if you aren’t him”, this mimetic conceptual poke served only to simulate a tunnel vision debate about the authenticity of the encryption, and several bravado attempts to crack the PGP key.

The Snowden case is symptomatic of our current condition of post-panoptic surveillance, whereby practices of data and behavior tracking have led to an extension of Foucault’s panoptic theories beyond the notion of hierarchical surveillance. Recent debates about post-panoptic practices indicate a shift from direct, embodied surveillance, to distributed, mobile surveillance manifested in the likes of PRISM, XKeystore and Tempra. The normalization of the “need to watch and be watched” generated by our information society is ruptured in this instance by Snowden.

The combination of public outcry – exemplified by the recent anti-surveillance march in Washington – and the intensified interest in the phenomenon of mass surveillance on the hype cycle, has resulted in a number of workshops and art exhibitions dedicated to “giving the power back to the people”. Eyebeam recently hosted PRISM Breakup [3], a three-day event programme of workshops and talks which sought to offset the publically perceived imbalance in our mutual surveillance society by making the tools of the anti-surveillance trade accessible to everyone. This strategy of using the ecology of the art institution as an alternative site of knowledge production, and a locus of retreat and pedagogical resistance, is well rehearsed in the history of contemporary art. However, by concentrating on providing the tools of counteraction against the omnipresent, invisible, panoptic enemy of surveillance, perhaps the bigger picture of the phenomena of neurotic binarisms and shifting psychological territories are in danger of being overlooked.

In contrast to these oppositional tactics, the artists and digital actionists, UBERMORGEN, approach phenomena such as Snowden, and other symptoms of perceived hyper-capitalism from a fuzzier, more ambiguous subjectivity. In their quest for knowledge production and social dialogue, the artists present and re-present the conditions of our global socio-political situation as physical and ephemeral catalysts of open-ended investigation. Through their encounter with the digital, they craft physical manifestations of data, acting as a mobile research unit producing knowledge about real life conditions that spike their interest. Their widely questioned claim to neutrality is defended in their Manifesto; they are very specific about their position as actionists as opposed to activists, and place the physicality of the human body and neurological system at the core of their practice: “we are not activists. we are actionists in the communicative and experimental tradition of viennese actionism – performing in the global media, communication and technological networks, our body is the ultimate sensor and the immediate medium”.[4]

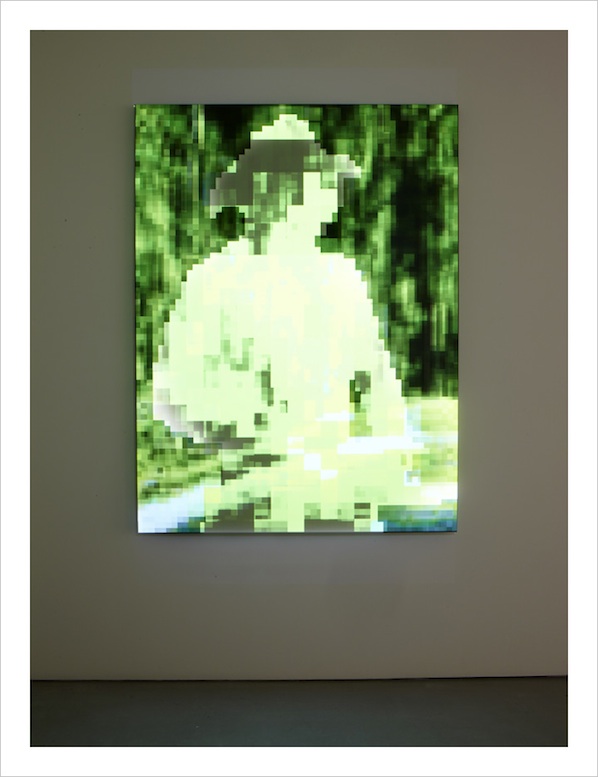

This position of political evasion hinges on a willful abstraction, and distancing from, their chosen subject matter. They activate this abstraction through their instinctive aesthetic strategy, creating a distance from the negative connotations popularly attributed to their subject matter by the media. The work Vladimir (2013) is a clear example of this obfuscating, poetic tactic the duo employ. Here, a CCTV monitor is split into four separate screens and located on the first floor of the gallery space. One screen shows the actual painting of Putin, (located in the lower gallery space). This takes the form of a pixelated painted canvas of Putin onto which an animated GIF is projected. Another screen from the CCTV plays footage of Putin at a press conference. On the remaining screens, there are images displaying alternative subjectivities of how Putin sees himself: heroic of the leader with a naked torso whilst partaking in the popular macho pursuits of fishing and shooting. These images are set up to relate to the animated canvas located and distanced in the lower gallery space. The relational dynamics between the works create a fragmented picture of the subject’s identity, and, as lizvlx suggests, this sense of abstraction and distancing through the aesthetics employed, neutralizes any characteristic of evil popularly associated with the subject himself. The viewer is left to come to an independent conclusion.

In fact, the entire show is a tightly choreographed relational synthesis. As I experience Hans and lizvlx’s all-encompassing Gesamtkunstwerk , I get the distinct, and unnerving impression that I am being watched. Call me paranoid if you will, but as I navigate through the show, I can’t help but notice that the familiar white cube space is punctuated and peppered by an abundance of CCTV cameras, staged situations of observation, identity –skewing overblown pixels, Crime Watch images and performative interrogation environments, placing the user cum visitor in an uncanny feedback loop of reactionary surveillance.

UBERMORGEN’s collaboration with Aram Bartholl, Net.Art (2013), is the first work I encounter as I enter the gallery. Bartholl’s OFFLINE ART [5] curatorial strategy takes the form of five wall mounted routers locally broadcasting a selection of UBERMORGEN’s net.art pieces disconnected from the Internet. These hermetically-sealed works make the visitor aware that they are being choreographed and controlled from the off – initiating the uninitiated and reminding those familiar with their work that it is never a comfortable ride. Bartholl’s new model of exhibition format is a subtle method of instilling a sense of self-awareness in the viewer. Throughout the show, UBERMORGEN continue to stimulate a gradual awareness, and partially expose, the systems of coercion, control mechanisms and surveillance techniques employed by institutions of public authority. As the tectonically-shifting position between fact and fiction continues to play out throughout the show, UBERMORGEN’s empirical probing of corporate and governmental control mechanisms becomes increasingly apparent.

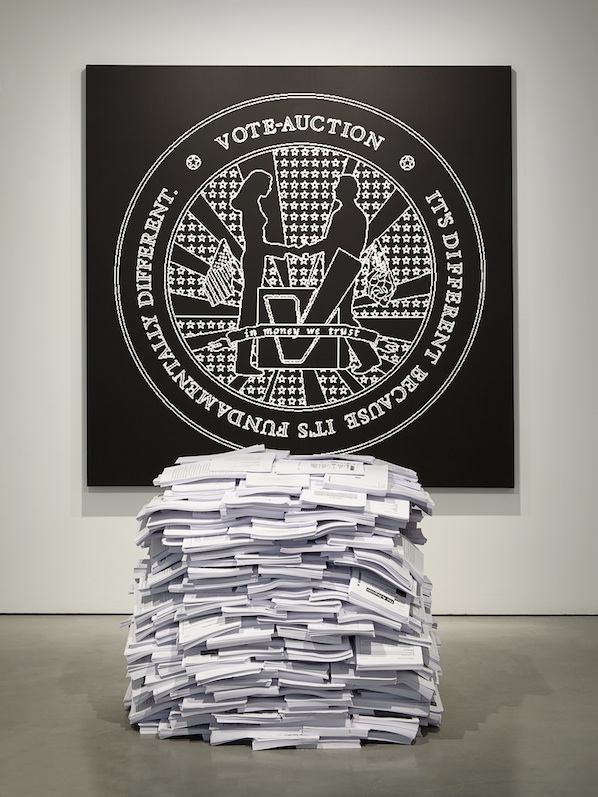

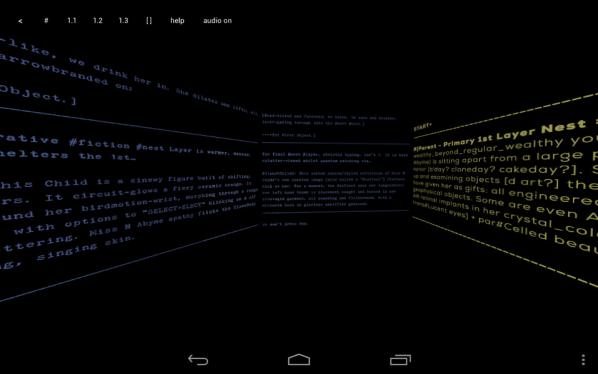

The historic work [V]ote-Auction(2000)- whose virtual subversion resulted in RL FBI intervention- is presented here as an impotent, dormant archive, its stacks of legal documents masquerading as a minimalist sculpture. However, the two new works CCTV(A parallel universe)(2013) and Do You Think That’s Funny? – The Snowden Files (2013) directly implicate the viewer in the act of surveillance. Both pieces are staged situations of observation and temptation. Do You Think That’s Funny is accompanied by a piece of pseudo fan fiction cum interview between UBERMORGEN and Edward Snowden available in the gallery catalogue. The installation itself is a contemplative, yet menacing frieze of control. According to the artists, they are in receipt of an encrypted data package from Snowden. The staged scenario tantalises the viewer/user by offering up Snowden’s dark data on wall-mounted Ethernet cables. A bench is provided for the viewer directly in front of the cables to contemplate the magnitude of their content. This meditative state is rudely interrupted by a looming white CCTV camera fixed to the parallel wall, levelled at the spectator. I am already aware of the presence of this electronic eye having encountered CCTV (A Parallel Universe) (2013), in the previous room. In this piece, the glaringly crisp images on the TV monitor clearly depict the panoptic gaze of the CCTV cameras installed in every part of the gallery, creating an infinite visual feedback loop.

Call me paranoid, but as I navigate the exhibition, I become increasingly self-conscious. White cube galleries usually have the feel of surveyed environments, with their incumbent aura of silent contemplation, lurking invigilators and clearly posed CCTV cameras, but this is a different kind of watching. The fact that the work itself is not the main focus of the all-seeing eye of protection slowly dawns on me, and I feel that I am in fact the star of the show. As I crawl along the tunnel to reach the work Superenhanced (2013), I am aware of the fact that I am enacting a part, and white mice, hamster wheels and men in white coats come to my mind as I glimpse the two chairs and the hand cuffs ahead of me. As I look up and see that my confession can be clearly observed by visitors above me through the upper gallery stairwell, the picture is completed and I take my position in this physical simulation of a video game environment.

UBERMORGEN’s work implicitly involves and implicates both the visitor and themselves in a complex, and increasingly distorted feedback loop of knowledge production and surveillance. It is not, however, the surveillance of the Weiwei-esque, ever-present CCTV camera that starts to destabilise me, but the internal, cognitive surveillance prompted by the ambiguous narrative of the works. As the camera becomes assimilated and internalised, I am compelled to survey myself.

This week the ReadingClub organised two live reading sessions with us at Furtherfield. The first performance with Aileen Derieg, Cornelia Sollfrank, Dmytri Kleiner and Marc Garrett, was based on a chunk of A Hacker Manifesto by McKenzie Wark [version 4.0]

The second session took as its starting point one of the ARPANET dialogues from 1975 -1976. What we first took as a historical moment, encapsulating the collision of modernist and postmodernist art world figures and the disruptive effects of digital network communications, turned out to be an ongoing research project by Bassam El Baroni, Jeremy Beaudry and Nav Haq.

Alessandro Ludovico, Jennifer Chan, Lanfranco Aceti and Ruth Catlow reenacted the historic collision in a contemporary context. The result – a new text called “Postinternet is net.art’s undefined bastard child”

You can view the recordings of both performances here:

ARPANET dialogues

Hacking, The Hacker Manifesto

Below we reproduce a translation of an interview by Annick Rivoire originally published in French for the publication Poptronics. Read original article here.

One might think (wrongly) that the “Reading Club” is a mixture of a “Fight Club” and a “Bookfighting” (book battles invented by a community from Orleans called Labomedia). Rather, the activity of the “Reading Club” is above all reading – an active, participatory, collaborative and performative reading on the Internet.

Annie Abrahams and Emmanuel Guez wanted this project to be nomadic and shared, so they invited, in addition to IRL institutions like the BPI Centre Pompidou or Le Jeu de Paume in Paris, network partners like Furtherfield, an art and digital resource center in London, and Poptronics. When Annie Abrahams (a challenging net-artist whose work Poptronics likes) told us about the “Reading Club”, it did not take us long to accept the proposition! This “interpretative arena” had a taste for experimentation.

So, in June began the first test (which I attended). Then, during the summer and early September, the device has been refined and made public. An extract from “A Hacker Manifesto” by McKenzie Wark, and snippets of the “Arpanet Dialogues“, these pre-chatrooms conversations from the 1970s attended by Yoko Ono, Marcel Broodthaers, Jane Fonda and a certain Governor Ronald Reagan, have been chosen for the fourth online session with Furtherfield on Monday 21st and Tuesday 22nd of October.

Annie Abrahams and Emmanuel Guez both have a taste for experimentation. The proof? They immediately organised a “Reading Club” session where the two of them answered me a few questions about their project! What you read below is the final version of this session. The writing process is visible on the Reading Club site (by clicking on the arrow at the top right).

Annick Rivoire: “Reading Club” is an “online performative reading experiment.” In this statement, what term do you prefer?

Annie Abrahams & Emmanuel Guez: Experiment, in terms of both the act of reading (and writing) in common and the audience to actively attend these readings through a chat window. Experiment, also in the sense that piloting the project and its various sessions allows us to experiment with different conditions of reading and writing.

Reading is generally considered something a little outdated (see: the complaints by publishers and teachers on the crises of the book and of writing since the advent of the digital). Is it to rehabilitate reading you’ve imagined “Reading Club”?

In the Reading Club, reading is not unthought, not a background. The text can be easily decomposed and recomposed. The radicality of text becomes visible. Words; the text allow what images can only indicate. They are closer to the temporality of thought, bring along a certain slowness, a return to attention. Text gives way to reflection. An image globalizes, leaks everywhere, encompasses but does not travel.

You invite critics, artists, performers to participate collectively, to share the “Reading Club” experience. Why?

Because without participation, the “Reading Club” does not work! It is a device made for people who love to read, who love to write and love to share. These three actions are combined and objectified in a single time and place. But the “Reading Club” is not restricted to the world of art and literature. We would love to propose a “Reading Club” to a wider audience over a longer period, for example in a series of sessions of 10 to 12 consecutive hours.

You explain that the “Reading Club” was inspired by the “Reading Group” of Brad Troemel and the “Department of Reading” by Sönke Hallman. Can you tell us more about these experiences?

Existing texts are at the center of both projects who ask to be payed attention to, to read and then discuss these together. Troemel proposed this on irregular intervals in the rather classical context of a workshop called Reading Group, whose archives unfortunately disappeared from the net. The project by Sönke Hallman, “Department of Reading” (2006), however is much closer to ours. It is an interface, a combination of a chatbot, written in python, and a wiki, developed to slow down and explore the act of reading and writing in a group.

Having participated in the first experiment of the “Reading Club”, I was surprised by the latitude of intervention of the “readers” to the text, which transformed this test session of shared reading into a writing session, or rather a writing “battle”. A very amusing, stimulating and annoying play with simple rules, which resulted in the complete rewriting and inevitably in the emergence of another text on arrival. Did you plan this “killing game” to revisit in color?

Please, take into account that the session in which you participated was a test session during our residency at Zinc (Marseille). We carefully chose which player was going to work on what tesxte (sic), but the interface had many bugs, so, we were forced to do only one tesxte with a group of very heterogeneous readers. It is true that the use of color leads to toying with the visual side of the interface, especially if the text is turned on itself, if it offers a thought biting its tail.

How did you set the cursors and determine, or even change, the rules of the “Reading Club”?

The setting is not fixed. For each session we redraw the reading modalities, the rules of the game. We can act on the identification of the readers (by removing the color, they become anonymous), the duration and length of the text and the number of characters to be used. For example, a short time will not allow a lot of thought. A low upper limit of the number of characters forces the readers to play with the letters rather than with sentences, etc. The choice of the readers in relation to the original text is also important. We know for example that a performer seeks to occupy space, to make the interface “shake”.

In the presentation of the project you mentioned the notion of the “interpretive arena”. One can not help but think of the violence of comments, tweets, the most aggressive sentences thrown as fodder on the Internet by the blogosphere, etc, in short, that other textual arena which is the Web as a whole and, even more, the social networks of Web 2.0. To what extent “Reading Club” is a criticism, a mise en abyme of that arena?

The “Reading Club” does not criticise the aggression you describe. Moreover, the “Reading Club” is not a critical apparatus, but something that makes possible a new form of criticism carried out jointly. What “Reading Club” reveals is that a shared reading and writing passes through emotions, through tensions, through power lines, but also through a certain euphoria. Any act of writing involves a certain symbolic violence. This violence is translated here by the control of the writing space (do not forget that the number of characters is limited). What remains in the end is a text and the whole session which we keep as an archive and which is visible through a timeline. They embody the thoughts, affects, the emotions of the readers at that time.

What is the status of the final text, who is the author, and how is this status questioned in the various experiments (in single or multiple configurations from Zinc to the Bpi Beaubourg)?

We have our specialist Antoine Moreau, one of the founders of the Free Art License, under which we placed all the productions of the Reading Club. We are less interested in the final text of a session than in the process of reading and the accompanying writing strategies. To answer the question, let’s say that the final text is both the product of the device we designed and a process that is the work of the invited readers, without forgetting the author of the original text (in French “texte originel”) – you will notice that we did not use the concept of “original” (in French “original”). We are therefore multiple authors…

The appointment, the performance, the text… All concepts that are being undermined on networks, where fragmented practices, the consultation and mass production of images (video, photo) push in a different direction. Doesn’t your project, which advocates writing (that of an author, those of the readers), promote something “old fashioned”, i.e. the weight of words rather than the shock of the photos?

If the question is “are we old fashion” (sic), we reply that it is cheesy to oppose text to image (it can not be seen but we are laughing). If you look at the timeline, you can see a film of a shared thought in the making.

Is the choice of texts the result of long discussions? The authors are (as far as the first editions of “Reading Club” are concerned) rather engaged personalities (artists or researchers). Are you inventing a form of controversy 2.0?

Not necessarily. The texts are selected jointly with the partner of the session. Sometimes it takes a long time, sometimes we immediately have an intuition that appeals to all partners. We aspire to have the selected texts reflect the concerns of the structure or the institution hosting the session (and ours). We do not seek controversy, it is already there all the time, everywhere. Rather we want to create a situation of confrontation, to ask the reader the question of how to choose his place, his attitude towards others who treat and mistreat the text along with him, to put him in the position to see evolve a thinking in which he participates, but can not control.

“Reading Club” goes international with this new edition with Furtherfield. How do you handle the issue of language? At the BPI, the selected text was signed by Mez, an artist who, as you explained, “wrote her names and texts as names of application and lines of computer code.” A solution to the issue of translation?

The language is that of the original text. Difference exists. Take a look at Mez 3.9.11 _i_dentity_x _or[s]c[h]ism_ (2005-09-29 06:17)

Contact: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is pleased to host One Minute Volume 7, a new series of shorts curated by filmmaker Kerry Baldry. The screening is accompanied by One Minute Remix, a selection of moving images from One Minute Volumes 1-5.

One Minute Volume 7 is the latest in the edition of One Minute artists’ moving image programmes curated by artist and filmmaker Kerry Baldry, and includes an eclectic mix of artists’ moving image constrained to the time limit of one minute. The One Minute programmes have been screened at numerous galleries, artists spaces and film festivals worldwide.

Volume 7 includes work by John Smith, Rose Butler, Tony Hill, Steven Ball, Alexander Costello, Leister/Harris, Kayla Parker and Stuart Moore, Louisa Minkin, Claire Hope, Max Hattler, Guy Sherwin, Steven Woloshen, Lynn Loo, Lumière and Son, Tansy Spinks, Gary Peploe and Peter Nutley, Eva Rudlinger, Michael Szpakowski, Zhel (Zeljko Vukicevic) , Matthias Kispert, Stuart Pound, Sellotape Cinema, Alex Pearl, My Name Is Scot, Kerry Baldry, Esther Johnson, Marty St. James, Nicki Rolls, Katherine Meynell, Chris Paul Daniels, Riccardo Iacono, Edwin Rostron, Martin Pickles, Grant Petrey, Annabel Dover, Kelvin Brown.

One Minute Remix (a selection from One Minute volumes 1 – 5) was originally compiled by Kerry Baldry for a screening as part of Kayla Parker and Stuart Moore’s moving image event ‘Welcome to The Treasure Dome’ (in a ICCI 360 Arena, which displayed audiovisual/moving image artwork via 5 projectors, with the screens arranged in a ‘seamless’ circle wrapped around the inside of a 21-metre diameter dome, and with surround sound) on behalf of ICCI (Innovation for the Creative and Cultural Industries) with Plymouth University; part of Maritime Mix – London 2012 Cultural Olympiad by the Sea programme, Weymouth (10 and 11 August 2012).

The programme includes work by Martin Pickles, Alex Pearl, Steven Ball, Gordon Dawson, Michael Szpakowski, Virginia Hilyard, Barry Lewis, Nick Jordan, Claire Morales, Nicki Rolls, Kerry Baldry, Riccardo Iacono, Eva Rudlinger, Zhel (Zeljko Vukicevic), Esther Johnson, Sam Renseiw and Philip Sanderson’s Lumière & Son, Katharine Meynell, Stuart Pound, Kayla Parker and Stuart Moore, Ron Diorio, Daniela Butsch, Guy Sherwin, Louisa Minkin, Rose Butler, Dave Griffiths.

+ More information: http://oneminuteartistfilms.blogspot.co.uk/

Produced by Furtherfield.

Kerry BaldryKerry Baldry is an artist/filmmaker who works in a range of media including film and video. She is a Fine Art Graduate from Middlesex University who went on to study film and video at Central St. Martins. Her first commissioned film was to make a film for BBC2’s One Minute Television which was broadcast on The Late Show – a joint collaboration between BBC2 and Arts Council England.

Over the last 6 years, aside from producing her own work, she has been curating, promoting and distributing a self initiated, unfunded project titled One Minute, One Minute Volume 7 being the latest in the edition. One Minute Volumes 1-7 are an eclectic mix of artists moving image constrained to the time limit of one minute and includes over 80 artists at varying stages of their careers.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England.

Contact: info@furtherfield.org

Visiting Information

Imagine visiting Finsbury Park in the not too distant future…

You could explore the sensory and medicinal properties of different plants in the Discovery Meadows; Play Glades offering people of all ages a range of adventurous physical challenges within a variety of wooded areas; visitors could go on a cultural tour of ‘natural rooms’ in the park, accessed through mobile devices; community gardens used for a wide range of events supporting and encouraging local people to come together around pleasurable growing, foraging and cooking events; Memorial Gardens providing an inspiring and elegant space for people of all faiths to take a moment to remember their passed loved ones.

These are just some of the futuristic ideas that students from the Writtle School of Design (WSD) will be exhibiting at Furtherfield that imagine possible futures for Finsbury Park.

In early 2013 WSD students created plans for the whole park, and then a number of individual designs for key spaces within the Park. They were asked to look at ways that Finsbury Park and Furtherfield could both provide more pleasing spaces and encounters for the surrounding communities. The opening of Furtherfield Commons, a new pop-up art, technology, and community space located within the park at the Finsbury Park Station entrance, will also be celebrated. Furtherfield Commons will serve as the venue for presentations from Furtherfield and Writtle School of Design students and staff about their visions for the park alongside an exhibition of the full array of inspirational images and ideas, and video interviews with the designers. Visitors are invited to make comments.

Press view and VIP private view: Friday 22 November, 2-5pm

Open 12-4pm Saturday and Sunday for two weekends. 23, 24, 30 November and 1 December 2013

Local people are encouraged to come along and respond to the designs.

Furtherfield Commons

Finsbury Park

Near Finsbury Gate On Seven Sisters Road

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England.

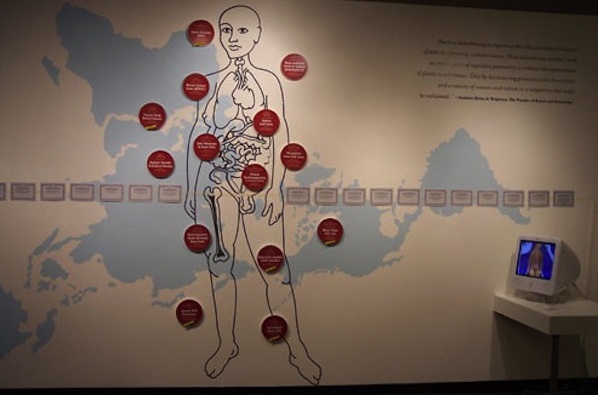

Featured image: XRay by Claude Chuzel

“One of the most consequential outcomes of this ubiquitous mode of organization of social life is that we have become so accustomed to relating to space in “either/or” and “here/there” terms that we have become mentally trapped inside this binary border-based model, making it difficult to imagine alternative ways of territorial organization.” Popescu [1a]

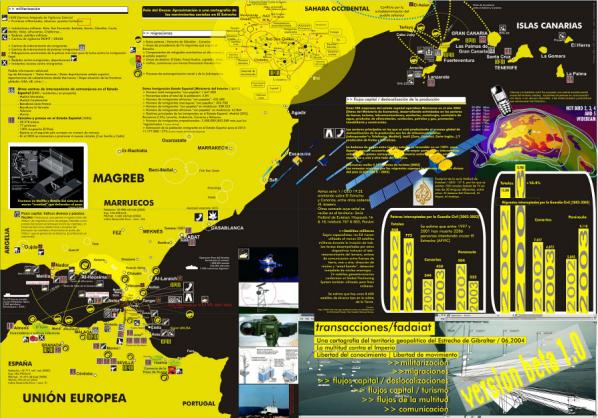

Maps inform us where things are situated. The borders depicted in each map propose a different view on the social conditions, attitudes, and interactions with others in the world. The AntiAtlas of borders project shows us different approaches for understanding “the mutations of control systems along land, sea, air and virtual states” and their borders. It has done this through the combined contributions of social and ‘hard’ science researchers and artists, all engaged in creative practices including Internet art, tactical geography, filmmakers, performers and hackers. The project also includes other relevant actors such as people working as professionals for customs agencies, surveillance industries and the military.

This is the first of two interviews with Isabelle Arvers who has collaborated with the IMERA team (the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Research of Aix-Marseille University), to curate this expansive and dynamic project. The first interview discusses the operational side of the project and the next interview examines selected writings, artworks, projects and ideas featured as part of the project.

Marc Garrett: Before we begin the interview it would great if you could tell us when and where the exhibitions, events, publications and other parts of the project begin?

Isabelle Arvers: The AntiAtlas programme will run from 30 September 2013 to 1 March 2014 and will be composed of five initiatives: an inaugural international symposium, two exhibitions, a website and the publication of a book. The International Conference will be held from 30 September – 2 October 2013 at the New Conservatory of Aix en Provence. The main aim of this conference is to present the results of the interdisciplinary workshops that took place in the last two years at IMéRA et at the Higher School of Art of Aix-en-Provence.

The AntiAtlas of borders will present two interlinked exhibitions. The first will take place in Aix-en-Provence at the Musée des Tapisseries from 1 October to 3 November 2013. The second will take place in Marseille at La Compagnie creative arts centre from 13 December 2013 to 1 March 2014. The two exhibitions will present works developed in collaboration with social scientists, researchers in the hard sciences and artists. They will offer several levels of reading and forms of participation. Visitors will discover new works, engage with transmedia documentation and participate in experiments. They will interact directly with robots, drones, video games, walls and systems. The aim is to encourage everyone to reflect on how we are directly and personally affected by the transformations of borders in the 21st century.

The final version of the website www.antiatlas.net/eng is an online extension of the exhibitions. Most importantly, the website provides access to works of net.art and artistic interventions in the form of an online gallery of works. This website and its documentation will extend the progress and reach achieved by the project. It will act as an archive and documentation site for the general public, artists, researchers and institutions.

In 2014, an AntiAtlas of border publication will be produced, gathering publications of researchers and artists on different and selected themes of the international conference and the two exhibitions.

MG: What has been your involvement with AntiAtlas?

IA: When I met the IMERA team (the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Research of Aix-Marseille University), they were looking for a curator in order to disseminate the outcomes of the past three years of seminars they conducted on borders. I saw this project as a great opportunity as there was a political dimension within it that attracted me. Also, I am deeply interested in tactical media and tactical geography and by new forms of visualisation and new aesthetics related to systems of control like drones, robots, satellites or surveillance cameras.

I wanted to create a participatory event that would allow people to follow our work online and offline. I also wanted to mix different kinds of works from research in the hard and social sciences to artistic installations, websites, games and videos. To do so, we decided to create a website www.antiatlas.net that would gather artworks, research articles and interviews, an online gallery and also all the presentations given during the different seminars conducted by IMERA on borders during the last three years. Thanks to the website, we were able to launch a call for proposals as I wanted to get the testimonies and the voice of migrants about their vision on borders.

Very quickly we understood that we needed to get more funding and partners, so I offered to seek media, private and institutional partnerships as well as to manage the communication of the entire event. This fundraising was needed to promote a global vision of the antiAtlas of borders and to link all the parts of the event: from the website, to the call for proposal, till the international seminar and the two exhibitions. Because of my multiple engagements in the project, I became one of the 5 co-producers of the programme.

MG: This is a complex project. It is noticeable that there is a diverse and dynamic, cross section of different practices being bridged to make it all happen. Has it been difficult to combine all of these practices so they can relate to each other coherently?

IS: Combining all these different practices was a wonderful and exciting adventure. During one year and a half, we worked very closely with the scientific and artistic committee and tried to exchange as much as possible between different visions and ways of working. I learned a lot from researchers and was amazed by the deep understanding and knowledge they have on the subject of borders. Thanks to their research and to their approaches to this issue, I was able to get a very diverse understanding of this complex subject. From me, they discovered the online communication and the power of the web and social networks to diffuse and share the information. They also got a better understanding of the tactical media field and we learned so much from each other that this experience is already a beautiful success in sharing and learning from passionate human beings. I come from media art world and I tried to respond to a scenario that the committee conceived with artists’ works, which is a very different way for me to work. This time I had a script to follow; the way I did it was to try to find some ludic interactive installations, as well as documentary projects or games, in order to allow the experimentation of the subject by the audience. They trusted me even if it wasn’t a field they knew well.

MG: Do you feel that it has de-compartmentalised these varied fields of knowledge successfully?

IS: What was particularly positive in the last seminars on borders we organised was that they allowed plenty of time to discuss and facilitate the exchange between the different perspectives. A specific example is a game project resulting from the collaboration between an anthropologist – Cédric Parizot – and a interactive laboratory from the Superior art School of Aix-en-Provence, which is led by the artist and game designer Douglas Edric Stanley. The idea is to create a “crossing industry game” drawing on the data collected by Cédric Parizot on trafficking. The collaboration addressed the visualisation, contextualisation and re-appropriation of a field of knowledge through game mechanics. I think that this experience really enriched all the team. The anthropologist was able to analyse his data in a different way, while the interactive students got closer to the reality of trafficking as they were experiencing through a game.

There are many other cross-disciplinary projects made in the framework of the AntiAtlas. I would say that what we want is to multiply different experiences and forms of knowledge on borders across and between the separate but intersecting fields of art and science. The exhibition is conceived to mix everything: research through the documentation space, researchers’ interviews, counter cartographies, interactive installations on biometrics and surveillance technologies, applications to divert control systems and documentaries providing a wider point of view on multiple dimensions of borders and their representations. Artists and researchers meet three times per year, some of them collaborate on trans-disciplinary projects, so that the conditions to meet and de-compartmentalise these fields are created. This is only the beginning. The process still needs to be pushed and facilitated as the antiAtlas is an attempt to create a new kind of cross-disciplinary encounter, let’s see how it will evolve!

This first interview with Arvers attended to organisational and operational aspects of the inter-disciplinary border-crossing within AntiAtlas project. The complex task of collating, sharing and collaborating to make it all happen at all could use its own map. The processes and engagements that evolved as the project took shape involved a collaboration of many different fields and practices, individuals, groups, organisations and cross cultural relations. This transdisciplinary approach helps us to unpack the deep levels of the meanings and value of crossing borders, in an organisational sense. Their dedication to transcend the seemingly ‘scripted’ blockages and restraints echoes a strong feeling that we need to re-assess the maps given to us, and what this means.

“What is needed to escape the modern mental “territorial trap” are ways of seeing and drawing that reveal what the geographical abstraction of the borderline obscures. It is only in this way, then, that we will acquire the necessary tools to think through a technologically enabled world of border flows and portals” Popescu.[1b]

Isabelle Arvers is an independent author, critic and exhibition curator. She specializes in the immaterial, bringing together art, video games, Internet and new forms of images by using networks and digital imagery. She has organized a large number of exhibitions in France and overseas (Australia, Canada, Brazil, Norway, Italy, Germany) and collaborates regularly with the Centre Pompidou and French and international festivals. http://www.isabellearvers.com/

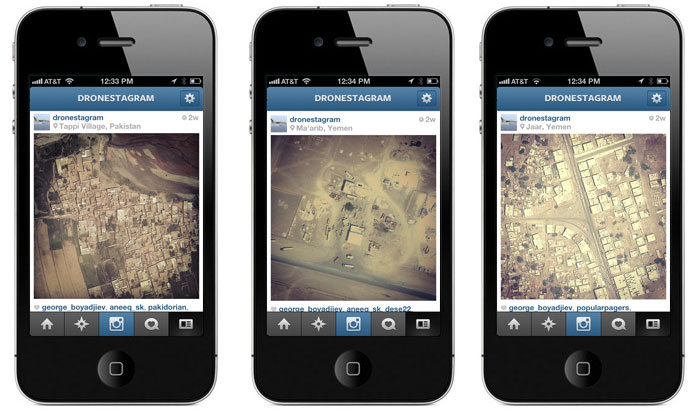

Featured image: Drone Shadows by James Bridle

I met the London-based artist, publisher and programmer James Bridle in Oslo back in May 2013, as part of the conference The Digital City. Bridle was in Oslo to speak about drones, algorithmic images, and urban software. His most recent art projects, Dronestagram and Drone Shadows, have caught a great deal of interest by the popular press, with recent features published in the Wall Street Journal, Dazed & Confused and Vanity Fair. Bridle is no stranger to getting the timing right. Addressing issues of drone surveillance and invisible technologies in ‘leaky’ Snowden times, or manage to get a bunch of academics, writers and critics, to talk about the birth of a new movement – based entirely on a Tumblr-blog he called the New Aesthetic – surely qualifies as good timing. In our conversation, Bridle, or the New Aesthetic’s commander-in-chief as Vanity Fair calls him, reveals that he never really meant to talk about aesthetics. It is not the printed pixels on a pillow, so often taken to be emblematic of the New Aesthetics by its critics, that is of interest to Bridle. Rather, Bridle wants to encourage a conversation about the kinds of images and sensibilities that emerge from algorithmic and machinic processes, and the embedded politics of systems that make certain images appear (and disappear).

Taina Bucher: Hi James, would you care to tell us a little bit about your background?

James Bridle: I studied computer science and artificial intelligence at UCL, University of London. By the time I finished, I hated computers so much that I went on to work in traditional book publishing.

It quite quickly became clear through working as an editor and publisher that publishing was heading for crisis, because it is an industry that is full of people who are afraid of technology. So I went on to specialize in e-publishing, looking at what happens to books as they become digital, which gradually grew into an examination of other cultural objects, and what happens to them as they get digital and the nature of technology itself.

T: Do you think that your background in computer science influences the ways in which you think about art and artistic practices?

J: I consider myself as having a background in both, and I actually think that having the literacy in both is incredibly valuable.

T: Interesting, what does this literacy in art mean to you?

J: Being able to speak the language of it and to be able to communicate it. Not just having an understanding of it, but also to be able to talk to people in publishing and the arts about the Internet without scaring them, and also to be able to talk to people in technology. They are still two separate cultures but it is possible to translate between them.

T: Do you consider software or code to be the material of your artistic practices?

J: Sometimes. I do think though that this should be the last concern. There are different ways of describing the world; materials are just a way of expressing it.

T: How then does software influence the kinds of expressions that you create?

J: Not only the material, but also the ideas coming from software are important here. There are plenty of ideas coming from technology that become really valuable as they are applied in the arts, for instance from the tradition of systemic analysis. You know, breaking things down to basic principles, algorithmic type steps, is a really valuable tool of analysis. It is also a dangerous one, as it can give you a systemic engineering view on problems.

T: You’ve said that you’ve been accused of romanticising the robot, or rather, that the New Aesthetic has been accused of this. What do you think the critics mean by that?

J: Well I do understand it in a way, because one way of talking about these things is really to anthropomorphize automated systems. When you do that, you bring a whole bunch of other questions into it, like whether these systems have a separate agency or not, whether they truly see and understand the world in ways that we do not entirely understand, or whether they are purely tools of human imagination. In order to understand these things, I think sometimes it is necessary to take a position, you know, talk about it as if it is true, and then you learn more by finding out where that description breaks down and where it doesn’t apply.

T: What is the New Aesthetic anyways? An aesthetic of the digital, or a digital aesthetic?

J: I never really meant to talk about aesthetics. The New Aesthetic is not about aesthetics. One of the earliest keys to it was looking at some of these images that result from systems, looking at things like computer vision and how the world is seen through machines, but really this is a shorthand of how the world is mediated through technologies in all kinds of ways, not just aesthetically. The aesthetic is a starting point where you can visually notice these things, but I am really interested in what it reveals about underlying things. I am not interested in notions of beauty or the aesthetics of it.

T: We could also understand aesthetics in terms of ways in which something is made to appear in certain ways. To talk about software aesthetics in these terms, would imply the view from technology, as opposed to the view on technology.

J: Not only the ways in which these technologies influence the ways we see things though, but the ways in which we think about them and understand them is important. By using some technology you’re bound by some of its biases and if you don’t understand what some of these biases are, then you’re slightly fooled by them. There is always an underlying politics to these things, and if you’re not aware of it, then you’re a victim of it.

T: Is it the artists’ job to reveal these biases in a certain sense?

J: Don’t know about job, but yes, that’s why I am doing it. The interesting thing to me is to explore deeper levels of these things. Getting a bit closer to the meaning and the underlying biases.

T: How do you work with, or get at the biases of technology?

J: By exploring and getting a technical understanding of it, but also by looking at how technologies actually operate in the world.

T: Do you think that a certain sense of code literacy is needed then?

J: I struggle a bit with that. I think that I do, the way that I work. Having a technical understanding of how things work is really, really important. But I am always struggling to figure out if it’s possible to do that without having the possibility to read the code. It is hard to study a foreign culture without knowing its language. Put differently, great artists mix their own paint. They have a fundamental understanding of the material. I think that if you’re making work with and about technology, and if you don’t understand how that technology works, you’re going to miss out on a huge chunk of what the technology is capable of doing. There is a lot of digital art that is very, very basic, because the people who are making it don’t actually understand how it works.

T: Could we see your work as a kind of software studies?

J: Yes, probably could see it like that. Some parts of software studies definitely informs my work, concepts like code/spaces. My practice is situated between art and technology and the stuff that always interests me, is when domains like software studies meets other domains, for instance where software studies meets architecture. I’m really interested in architecture because it is such a situated practice. It is not like art or high-flown critical theory, which is kind of above the world; it really has to be rooted in the world. The crossovers are what are interesting. People like Eyal Weizman or Keller Easterling, who talk about how architecture shapes not just the physical domain, but also the legal and political spaces.

T: One of your projects that I really like is “A ship adrift”. Besides being a bot, how can we understand this “ship”? How does it work and which data sources does it use?

J: It is part of a larger art project in London called “A room for London”, which was a one-room hotel built on top of another building on the south bank of London in the shape of a ship. It was both a one-room hotel that you could book and stay for the night, and it was used for art things, music projects and other events. I was asked to do something that connected it to the Internet, to some kind of an online component. I didn’t want to do something that was totally separate, but something that was rooted in this idea of the ship, and its actual location. One of the major things is that it is a ship that doesn’t go anywhere. It fails at the first condition of being a ship.

I put a weather station up on the building to monitored wind speed, direction, and a bunch of other stuff, and took all the data from that, to drive an imaginary ship. For example, starting in January, and from the physical location of the ship: If the wind blows 5 miles an hour, my imaginary ship would move five miles east or wherever the wind was blowing. So this thing was driving friction-free. As it’s going, it knows its own location and searching the Internet for stuff nearby. It is looking for information on the web that also has a geographical tag to it. Good sources for that are Wikipedia as there are lots of articles that have a physical location tied to it, so you can look those up and read those in. My favourite source was Grindr, a sex network for Gay men that was geo-tagged. Unfortunately they did upgrade the security there three months into my project, so I no longer had access to that data. I was also feeding it other texts as well. There was for instance a sub-thread running through the whole project around Joseph Conrad who I’m a huge fan of. So I gathered all these texts and running really, really basic language generation text programs on it, the same kinds of programs that generate spam emails. So it is not intelligent in any meaningful way. It is really about how we read broken texts. I just quite love that, because it is really part of the vernacular of the web. It’s what language sounds like when it is broken through machines. It is also quite empathetic, and it makes us examine our own feelings towards technology.

A Ship Adrift by James Bridle

T: Let me just quote you: “Forget controlling the machine; impersonate it. Fake it till you make it, like horse_ebooks, like A Ship Adrift” (Impersonating the Machine). How far would you take your own aphorism? Did your bot actually make it?

J: You can pick your criteria of success. My criterion of success is to produce an emotional response in me and in other people as well. And in this case, other people were really following along, particularly on Twitter. It had it’s own voice, although it was still generated by a semi-autonomous software system. It is not a bot really, it is not intelligent, it does not have agency, but it is generating a feeling about machines, which I think is important.

T: How did people respond to the ship?

J: Someone called it a ‘Robot Polari’. Polari is a European argot, which is almost gone now. Polari was a secret language that originated in circuses, travellers and theatre companies in the 19th century and became the secret language of gay men. It was a kind of coded language they used to communicate. Argots like that served multiple purposes. On the one hand concealing communication from the outside world that may be hostile to it, but also within the group, in terms of creating a bond between its members. So for me, the ship adrift felt kind of like an argot to the machines; machines kind of identifying themselves to each other, semi-protecting themselves.

T: There is a tendency to treat bots as ‘fakes’, as somehow inauthentic beings, which is really being framed as an increasing problem online. Why are we so obsessed with this notion of the inauthentic of that which is not entirely human?

J: That is a really good question. This problem of authenticity and technology extends much further. The whole New Aesthetic project springs in some extent from trying to understand what people consider being authentic digital experiences. I think we have this quite big problem, which is that we are so unsure with how technology operates that we have a deep distrust of it.

I think Instagram is a really good example of that. The entire mechanism of Instagram is predicated on applying the filters of analogue cameras to digital photographs, which for me is a process of authenticating. We are aware on some level that these photos are apparently less stable and less persistent than the photographs you keep in a shoebox, some server going down could delete them any moment. There is a precarity to them. We’re all the time trying to authenticate stuff, and all of this is tied to our fear and confusion around digital things.

T: It seems that questions of the invisible, or making what is seemingly kept from view visible, is a core element of your artistic practice. What is it about the invisibly visible and visibly invisible that intrigues you so much?

J: Take the drone programme. It is a political programme. It’s a natural extension of our international relations and we’ve developed a set of technologies to address these relations. The drone is perhaps the most emblematic and also a largely invisible one. It’s really been going on for the past decade, but it has only very recently become a very political issue. This is due to the fact that drones are largely physically invisible. They are secret technologies that no one ever really sees. In all kinds of ways: You don’t see them in newspapers, until very recently, and you don’t see them in movies. The invisibility is conferred by them being seen as technological objects. Because they are technologies, they are not criticized in a way that a policy, or a person, or human actions can be. Even though they are all about policies and human politics. Because humans in general, are not technologically literate, they just back off from that. For most people, it is just the way it is.

T: Would you say that it is the technology itself that is actually invisible, or the institutions and the kind of political work going on in the background of these drones?

J: Both of those things. This is where it gets interesting, because a lot of this technology materializes that political will. Stuff that would have been entirely secret previously, now exists as objects in the world. There is this incredible paradox, technologies both reify and materialize power and human desires, but are made invisible in a way that makes them beyond comprehension.

T: How have people reacted to your drone work?

J: Well, people have had discussions about drones they would not have had otherwise. But I hope that my work also raises questions about technology and the media on a deeper level, not just in terms of the drone programme.

T: Now that even our police forces are starting to talk about smart policing and using drones for surveillance purposes, what do you think would be an appropriate response?

J: I am not sure how the situation looks like in Norway. But London is the most heavily surveilled city on earth. Yet, we don’t talk about it much. For the most part everyone seems to be ok with that. It is a matter of technology, and thus easy for most people to ignore. If drones raise greater fears about surveillance, then maybe that will push back on all forms of surveillance. I’m not particularly more worried about drone surveillance than I am with cameras on a building. They are all functions of the same thing, but if it actually makes people think more about surveillance and control mechanisms then that is a fairly interesting way for it to go.

T: Maybe we’ll just end up in an overly visible state, where the amount of visibility goes counter to what it is supposed to do. If everyone is highly visible all the time, then the questions becomes one of analytics. How are we to make sense of this visibility?

J: The best I can hope for is a kind of democratization. We should all have access to them and be able to see through them as well.

T: What is up for you next?

J: I think I will have to take a lot of the momentum of this drones work and try and push it back up a layer to the political and legal space. I’ve never been interested in just the drones. I’ve always been interested in the wider implications of the technologies that they embody. So the drones are just the start, but there is a much larger conversation we should be having. So the question is how we can expand this conversation to those other areas and not just make it about weird sexy planes.

T: How does your work connect with social media? Do you use social media as a useful platform, or a point of critique itself? Does social media in any way change the possibilities of your artistic practice?

J: Yes, totally. I represent myself, and I have my own audience. It amplifies the things that I do, but I don’t theorize too much about it. That would be a whole rabbit hole to go down to. And I’m very well aware that I’m living inside, so it would be difficult to have such a critical eye on, because I’m so involved in it. I think that I will at some point though. One of the key tenets of my practice is not to perform manifestos, I don’t want to draw or come to any conclusions because I think we are at such an early stage with these social networks and social media, and the Internet in general that we don’t even have the critical frameworks to talk about it seriously, let alone come to any serious conclusions about it, yet.

“None but those who have experienced them can conceive of the enticements of science.” Mary Shelley, Frankenstein.

Rachel Falconer writes about the cyberfeminist art collective subRosa, a group using science, technology, and social activism to explore and critique the political traction of information and bio technologies on women’s bodies, lives and work.

Following a recent interview with the founding members of the collective, Hyla Willis and Faith Wilding, this article presents subRosa’s trans-disciplinary, performative practice and questions what it means to claim a feminist position in the mutating economies of biotechnology and techno-science.

The technological redesigning and reconfiguration of bodies and environments, enacted through the economies of the biotech industry, is an emerging feature of contemporary life. As these new ‘bits of life’ enter the biotech network, there is a slippage in our mental model of what constitutes the body, and more specifically, ‘life’ itself. As radically new biological entities are generated through the processes of molecular genetic engineering, stem cell cultivation, cloning, and transgenics, bio-artists and bio-hackers co-opt the laboratory as a site of critical cultural practice and knowledge exchange. Human embryos, trans-species and plants are constructed, commodified, and distributed across the biotech industry, forming the raw materials for bio-art, DIY biologists and open science culture.[1] These corporeal products and practices exist within new and alien categories, transgressing the physical and cognitive boundaries set by biopunk science fiction and edging towards the possibility of a destiny driven by genetics and life sciences. With the eternal rhetoric of a high-tech humanity, and the threat of Michel Foucault’s[2] biopolitics constantly on the horizon, today Harraway’s[3] myth of the cyborg exists in the form of corporeal commodities travelling through the global biotech industry. Scientific research centres stock, farm, and redistribute biological resources, (often harvested from the female scientists themselves). Cells, seeds, sperm, eggs, organs and tissues float on the biotech market like pork belly and gold. Seeds are patented, and other agro-industrial elements are remediated and distributed as bits of operational data across the biotech network. We/cyborgs[4], are manifested as a set of technologies and scientific protocols, and, as a result, the female body in particular, is reconfigured into a global mash-up of cultural, political and ethical codes.

The increasingly pragmatic realisation of the biotech revolution has provoked a ‘cultural turn’ in science and technology studies in general, and feminist science studies in particular. Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s dOCUMENTA (13) proposed an interdisciplinary approach to the role of science for ‘culture at large’. Certainly, by foregrounding the heavy hitters in the field such as Donna Haraway and Vandana Shiva, dOCUMENTA (13) laid claim to addressing the global conflicts of biotechnology. However, the feminist agenda was not specifically addressed, and the key issues of the impact of biotechnologies on feminist subjectivities were only paid minimal lip service. With the exception of Shiva[5], the tone of dOCUMENTA (13) hinted at a positivist, emancipatory take on biotechnology and technoscience without assuming a critical position. There was very little public debate or critical analysis engaging the philosophical, ethical, and political issues of feminism and female subjectivities within the realm of biotechnology.

Notably absent from last year’s dOCUMENTA (13), the activist feminist collective subRosa’s performative, interdisciplinary projects are channelled towards embodying feminist content, practices, and agency, and laying bare the impact of new technologies on women’s sexuality and subjectivities – with a particular emphasis on the conditions of production and reproduction. Through their research-led practice and pedagogical mission, the collective analyse the implications and conditions of the constantly surveyed female body, whilst mapping new possibilities for feminist praxis. subRosa interrogate the conditions of surveillance, private property rights, and other control mechanisms the female body is subjected to by ART(Assisted Reproductive Technologies). The collective’s hybrid, interdisciplinary practice navigates the multiple identities the female body has taken on through techno-scientific development, including: the distributed body, the socially networked body, the cyborg body, the medical body, the citizen body, the soldier body and the gestating body. In contrast to the overarching and pervasive illustration of the technoscientific cultural landscape painted by dOCUMENTA(13), the current members and founders of the collective, Hyla Willis and Faith Wilding, are very clear in their critical intent. The collective choreograph and place themselves within globalized bio-scenarios in order to question the potential for resistance and activism within these constructs.

subRosa’s overarching vision to create discursive frameworks where feminist interdisciplinary conversations and experiments can take place, is research-led and takes its cue from the canon of radical feminist art practices. Cell Track: Mapping the Appropriation of Life Materials has featured in a number of exhibitions, most recently in Soft Power. Art and Technologies in the Biopolitical Age, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain. This project consists of an installation and website examining the privatization and patenting of human, animal and plant genomes in the context of the history of eugenics. Cell Track highlights the disparity between the bodies that produce stem cells and the corporations that control the products generated from them. Bringing together scientists, cultural practitioners and wider publics in the construct of the gallery space, subRosa generate discourse around the patenting and licensing of DNA sequences, engineered genes, stem cell lines and transgenic organisms. The project’s participatory aim is to set up an activist, feminist embryonic stem cell research lab in order to produce non-patented stem cell lines for distribution to citizen scientists, artists and independent biotechnologists. This environment of shared knowledge production and speculative, alternative, research activity is at the heart of subRosa’s social practice.

Due to the pedagogical nature of subRosa’s activities, the collective’s critical stance towards IVF and ART has proven to be particularly provocative, and their scepticism towards the emancipatory language of ‘choice’ co-opted by ART, has been met with some resistance by other feminist practitioners. However, it is in this very agonism[6] that subRosa wish to become more visible, and they welcome criticism and debate in the public discursive spaces that they create. In a recent interview, Faith Wilding and Hyla Willis both expressed their desire to generate an expanded, and deeper discussion about the wider issues involved in ART in particular and biotechnology’s effect on female identity in general. subRosa’s potential to reach wider publics and audiences is partially determined by the socio-political context of the communities in which they operate. Perhaps in reaction to this, subRosa’s focus is now shifting towards embracing the aforementioned ‘cultural turn’ in science as they address the position of feminist scientists themselves.

The imperative to reclaim feminist discourses and narratives in science is of growing concern to subRosa, as they believe that feminist agency lies in the practice of science itself. By relocating lab-work from the dominant scientific institutions to the public environment of the gallery, subRosa provide the critical space in which new feminist scientific praxis can operate,[7] and new dialogues and discourses can be created. Their conviction that political and critical traction lies in practice as discourse, and the potential of face to face encounters, is demonstrated in their recent project for the Pittsburgh Bienal: Feminist Matter(s): Propositions and Undoings (2011). In this installation, SubRosa take Virginia Woolf’s[8] assertion that ‘tea-table thinking’ provides an effective antidote to the male-driven ‘war-mentality brewed in boardrooms and command centers’ as their main conceit. Redeploying Woolf’s idea toward the rethinking of the traditionally male-dominated discipline of science, Wilding and Willis’ installation brings traces of the science laboratory to the intimacy and hospitality of the kitchen table, and in turn, also situates what is normally a private, feminized space in a more public domain.

These tables stage a dialogue between one or two visitors in response to the presentation of female figures in science, both the popularly acknowledged and the underexposed. subRosa foreground women scientists past and present and reimagine an alternative, feminized history of science and technology. The installation explores feminism and participatory practices as modes of scientific research, with the aim of generating dialogue and discourse around the questioning of the dominant historical narrative of science. Specially tailored installations reside on each table, evoking lab work while celebrating the history of the women protagonists they play host to – from anarchist painter Remedios Varo to geneticist Barbara McClintock.

subRosa’s pedagogical imperative is at once inclusive and provocative, and their role as facilitators of a discursive space outside the traditional institutions and control structures of science, is where their radical aspirations lie. Pedagogical art practices often teeter on the brink of propaganda, and subRosa are quite comfortable with the propagandistic label. Considering the economic and cultural climate in the USA with regard to the politics of reproduction, their work has been particularly well received in the context of European cultural institutions, whereas in the USA there is greater interest for the work in academic institutional settings. Perhaps this could be symptomatic of the general privileging of discourses around intersex, transgender and queer subjectivities. The dominant bias of the gatekeepers of the artworld to showcase queer practices is evident in the promotion of artists such as Ryan Trecartin and Carlos Motta on the international circuit. Curators have tended to position artists addressing the gendered ‘Other’ within a contemporary queer framework, whilst keeping feminist art practices on the peripheries of 1960s/1970s retrospective nostalgia. This tendency presents a muddying of the waters for contemporary feminist art practices such as subRosa.

This may also be part of a more general tendency to demonize and move away from feminist identities and discourses in wider society. The academic shape shifting from ‘women’s studies’ to ‘gender studies’ to ‘queer studies’ has diminished the feminist conversation and, therefore, the impact and receivership of feminist art practices. This has rendered the popular conception of ‘Queer’ as acceptable and non-aggressive. Furthermore, the term ‘Queer’ and the subsequent morphing into the verb ‘queering’, has been co-opted by transdisciplinary academic discourse, and is now an expansive, all embracing cultural term – a phenomenon that has met with a certain amount of scepticism from the queer community.

This privileging of the expansive ‘othering’ of queer rhetoric has often resulted in feminism being rejected as a radical and out-dated political identity by art practitioners themselves. This ambivalent attitude is perhaps also indicative of the wider feminist debate, in which post-feminism has splintered into fragmented, diluted groups, each policing their own identity politics with little sense of a bigger struggle. However, the collaborative, interdisciplinary environments orchestrated by subRosa signal a return to the indisputably material actuality of the female body. Through their insistence on the possibilities of feminist bench-side practices, and the forensic unpicking of the power/control structures inherent in biotechnology, subRosa expands the feminist lexicon through the empirically re-appropriated organic materiality of the body.

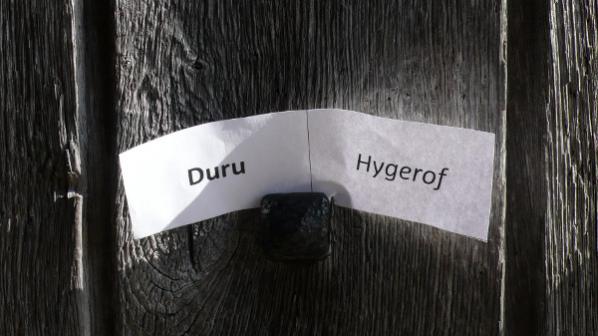

Old Words Made New.

Ethical knowledge, sacred spaces, forgotten histories and challenging predispositions.

Furtherfield is pleased to present the excellent cross cultural project DISCLOSURE: Old Words Made New. We have collaborated with Medieval Studies Graduate Students from King’s College London, and artist Erica Scourti to reversion a contemporary representation on the subject of medieval social lives, based on the theme of ‘ethical knowledge’ through Old English. With a combination of works in the Finsbury Park surroundings, sound installations, collaborative writing, and performance.

The project is part of Colm Cille’s Spiral project, a collaboration between Difference Exchange, King’s College London and Furtherfield, and takes place alongside a commission by artist Erica Scourti. It relates to a series of contemporary art and literature commissions and dialogues rethinking the legacy of 6th Century Irish monk Colm Cille, or St Columba, that unfolds across Ireland and the UK, starting and ending in Derry-Londonderry for City of Culture 2013.

Come and add an Old English phrase to the Wordhoard painted onto the walls of Furtherfield Gallery!

Help us create a visual hoard of words, received from scholars all over the world, which will show the extent of the current study of Old English. Explore the memories of our site-specific work at Bradwell-on-Sea, a church built in 654 by St Cedd, by watching our recording of the event. Walk through Finsbury Park listening to the sounds of Old English poetry and meditating on trees that bleed.

For the event, Erica Scourti will present another iteration of her video postcard project, currently existing as a series of empty, annotated videos on her Instagram profile. As a one-off, the full set of over 100 videos emailed out to friends, family and online contacts over the summer period will be screened, the only time they will be shown publicly. Also, the metadata the recipients provided for each video will form the basis of a sound piece that will play throughout the afternoon.

The project has explored new ways to understand and interpret the language and social contexts of a time where Christianity was at its early phase of using its people through networks around the UK, whilst pagan culture was still thriving.

The question posed to the King’s College students was “If we existed in a contemporary society where the Internet could no longer be trusted because of systems of networked surveillance, what would be the different ways in which we could communicate?”

In July 2013 they showcased their findings at a live public event at the historic Bradwell-on-Sea Church, which is now being held at Furtherfield.

A warm thanks to Kings College lecturers Professor Clare Lees, Dr Joshua Davies, Dr James Paz for collaborating.

Other Colm Cille’s Spiral projects have taken place across the UK and Ireland as part of Derry-Londonderry City of Culture and can be explored at www.colmcillespiral.net

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England.

Featured image: PAH graphic resources

Over the last few years there has been a keen interest in discussing the notion of public space; demonstrations, camps, collaborative projects, artistic interventions, community projects, social activism are just a few names that exemplify the different forms of engagement that deal with the complexities of it. Despite their different aims and impact most of these actions have given evidence of the need to re-appropriate the public space; through collective and networked practices individuals, groups and organizations ‘challenge the conventional notion of public and the making of space’[1]. Although the liveness and even virality of these events, projects or actions hinder any prediction about its midterm effects or endurance, the fact is that there is an emerging legacy that is already dismantling certain assumed thoughts about ‘the public’.

The retiree Hüseyin Çetinel’s initiative of painting a public stairway with rainbow hues in his neighbourhood in Istanbul has been the last case involving cultural transformation, virality and social activism. After he painted the local stairs to ‘make people smile’ and ‘not as a form of activism’ the municipal cleaning service painted over the stairs in dull grey provoking a chain reaction that mobilized citizens to paint stairways throughout the city. Local communities and social movements appropriated this beautiful participatory action as a form of protest after Çetinel’s stairway became viral in the social media. This example shows the intricacies of the public space and its expanded performativity. As Gus Hosein Executive Director of Privacy International argues ‘there is a confusion as to what is public space is and how it relates to our personal and private space’ in a social context where the emergence of the use of social media and surveillance as well as the appropriations of the space by private corporations and social movements and individuals are constantly questioning its boundaries[2].

From my point of view, some of these actions that play in-between the social, political and artistic might be considered re-enactments of the public space as they aim to reconstruct the term itself by applying alternative procedures and by generating at the same time transductive pedagogies. However, in order to give a comprehensive understanding of the implications of the public space and its controversies it is essential to rethink the notion of the private space. Traditionally, home has been recognized as the physical private space; home is the main representative of the private sphere that encompasses the domestic and intimate. According to Joanne Hollows, ‘the distinction between the public and the private has been a key means of organizing both space and time’[3] and consequently to promote a clear functional division.

This traditional perspective has been questioned and altered due to some current issues and events that are noticeably interconnected with those of the public space; an increasing number of evictions and homeless peoples, housing policies, escraches[4] in front of the houses of politicians, the appearance of ghost neighbourhoods due to real estate speculation, home as an alternative space for performance practice and community development, among others. Thus, home might be conceived as a container of individuals and actions, as a social product or instrument, as topographical placement or as a relational structure. Home entangles interesting layers of analysis that might serve to establish new relational and yet responsive parameters to understand both the private and public space. Some of the following examples that perform between art, activism and affections corroborate the significance of home; as Blunt and Dowling state ‘home is not separated from public, political worlds but it constituted through them: the domestic is created through the extra-domestic and viceversa’[5].

In Barcelona, the city where I live there have been noticeable factors that have stressed the importance of home as a topic of interest. Probably the most significant case is the increasing number of evictions―over 350.000 in the last four years―as many families cannot afford their rent or mortgage after losing their jobs (the unemployment rate is 26.3%). Beyond the personal implications and devastating effects that evictions have on families, they also indicate that home is not anymore our secure space or refuge; on the contrary, if the individual does not respond to the production and consumption requirements is physically displaced to the streets. Consequently, many citizens are trying to find shelter back again in the public space.

If the 70s Richard Sennett announced the decay of the public space by the emergence of an ‘unbalanced personal life and empty public life’[6], the related problems with housing have provoked the reactivation of the public space at many levels. At the same time, there is an increasing culture of the debt that ties together individuals and financial institutions in long-term relationships. As Hardt and Negri explain ‘Being in debt is becoming today the general condition of social life. It is nearly impossible to live without incurring debts—a student loan for school, a mortgage for the house, a loan for the car, another for doctor bills, and so on. The social safety net has passed from a system of welfare to one of debtfare, as loans become the primary’ means to meet social needs’[7].

These ideas can be exemplified by the actions of PAH (The Platform of People Affected by Mortgage Debt), an activist group of citizens that stops evictions through demonstrations and guerrilla media actions in the streets and that also helps struggling borrowers to negotiate with banks and promotes social housing[8]. This organized group of citizens has been awarded this year the Citizen Award by the European Union for denouncing abusive clauses in the Spanish mortgage law and battling social exclusion. PAH has received the support of the collective Enmedio that generates actions in the midst of art, social activism and media. For example, their photographic campaign ‘We are not numbers’ consisted in the design of a collection of postcards each one containing a portrait of a person that was affected by the mortgage debt by a local bank entity. The postcards were delivered in front of the bank’s main building for people to write a message. The written postcards were then stuck in the front door main door turning numbers into a collage of human struggle. PAH and Enmedio actions become highly effective thanks to their media impact and their virality in the social media. Invisible individuals isolated in their struggle, find alternatives through an assemblage of support that connects the public and private space and that is also mediated by informative and constitutive tools that the virtual space offers. As Paolo Gerbaudo claims ‘social media have been chiefly responsible for the construction of a choreography of assembly as a process of symbolic construction of public space which facilitates and guides the physical assembling of highly dispersed and individualized constituency’[9].

Processes of speculation, gentrification and eviction can be found in many western cities as well as different kinds of collectives and groups working for human rights advocacy. This is also the case of the Brooklyn based collective Not an Alternative has also carried out different guerrilla actions concerned with the problem of housing and eviction such as their series of workshops and media actions of ‘Occupy Real State’ or ‘Occupy Sandy’.

Many of the actions that these collectives promote might be understood as DIY activism as they are based on the empowerment and the development of skills. In this regard, it is interesting to observe how DIY that traditionally has been related to activities in the domestic space serves as a strategy to protect it and to trigger new forms of protest in the public space while enhancing the creation of an expanded family (or at least a sense of togetherness) through the social media.