First published in Remediating the Social 2012. Editor: Simon Biggs University of Edinburgh. Pages 69-74

—-

The acceleration of technological development in contemporary society has a direct impact on our everyday lives as our behaviours and relationships are modified via our interactions with digital technology. As artists, we have adapted to the complexities of contemporary information and communication systems, initiating different forms of creative, network production. At the same time we live with and respond to concerns about anthropogenic climate change and the economic crisis. As we explore the possibilities of creative agency that digital networks and social media offer, we need to ask ourselves about the role of artists in the larger conversation. What part do we play in the evolving techno-consumerist landscape which is shown to play on our desire for intimacy and community while actually isolating us from each other. (Turkle 2011) Commercial interests control our channels of communication through their interfaces, infrastructures and contracts. As Geert Lovink says ‘We see social media further accelerating the McLifestyle, while at the same time presenting itself as a channel to relieve the tension piling up in our comfort prisons.’ (2012: 44)

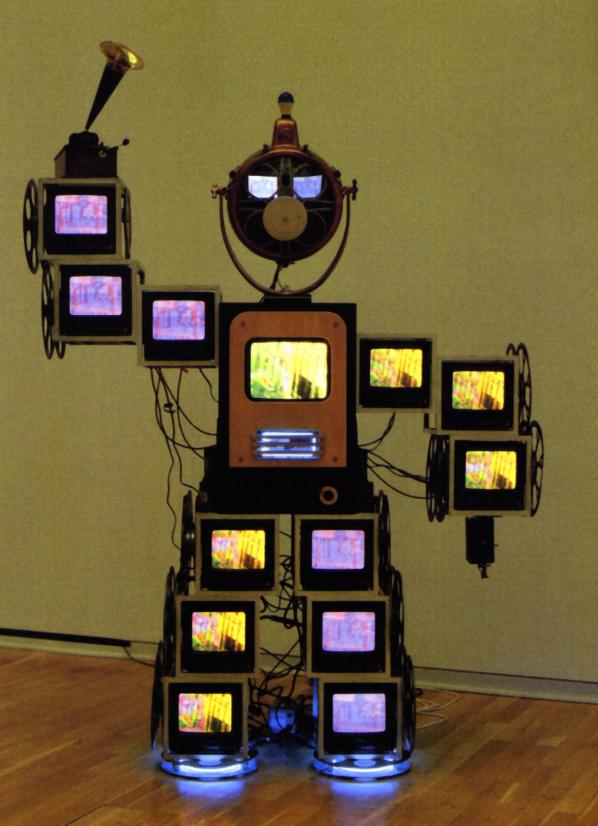

Many contemporary artists who take the networks of the digital information age as their medium, work directly with the hardware, algorithms and databases of digital networks themselves and the systems of power that engage them. Inspired by network metaphors and processes, they also craft new forms of intervention, collaboration, participation and interaction (between human and other living beings, systems and machines) in the development of the meaning and aesthetics of their work. This develops in them a sensitivity or alertness to the diverse, world-forming properties of the art-tech imaginary: material, social and political. By sharing their processes and tools with artists, and audiences alike they hack and reclaim the contexts in which culture is created.

This essay draws on programmes initiated by Furtherfield, an online community, co-founded by the authors in 1997. Furtherfield also runs a public gallery and social space in the heart of Finsbury Park, North London. The authors are both artists and curators who have worked with others in networks since the mid 90s, as the Internet developed as a public space you could publish to; a platform for creation, distribution, remix, critique and resistance.

Here we outline two Furtherfield programmes in order to reflect on the ways in which collaborative networked practices are especially suited to engage these questions. Firstly the DIWO (Do It With Others) series (since 2007) of Email Art and co-curation projects that explored how de-centralised, co-creation processes in digital networks could (at once) facilitate artistic collaboration and disrupt dominant and constricting art-world systems. Secondly the Media Art Ecologies programme (since 2009) which, in the context of economic and environmental collapse, sets out to contribute to the construction of alternative infrastructures and visions of prosperity. We aim to show how collaboration and the distribution of creative capital was modeled through DIWO and underpinned the development of a series of projects, exhibitions and interventions that explore what form an ecological art might take in the network age.

In common with many other network-aware artists the authors are both originators and participants in experimental platforms and infrastructures through processes of collaboration, participation, remix and context hacking. As artists working in network culture we work between individual, coordinated, collaborative and collective practices of expression, transmission and reception. These resonate with political and ethical questions about how people can best organise themselves now and in the future in the context of contemporary economic and environmental crisis.

Though this essay draws primarily on artistic and curatorial practices it also makes connections with the histories and theories that have informed its development: attending to the nature of co-evolving, interdependent entities (human and non-human) and conditions, for the healthy evolution and survival of our species (Bateson 1972); producing diverse (hierarchy dissolving) social ecologies that disarm systems of dominance (Bookchin 1991, 2004); and seeking new forms of prosperity, building social and community capital and resilience as an alternative to unsustainable economic growth. (Bauwens 2005) (Jackson 2009)

Furtherfield’s mission is to explore, through creative and critical engagement, practices in art and technology where people are inspired and enabled to become active co-creators of their cultures and societies. We aim to co-create critical art contexts which connect with contemporary audiences providing innovative, engaging and inclusive digital and physical spaces for appreciating and participating in practices in art, technology and social change.

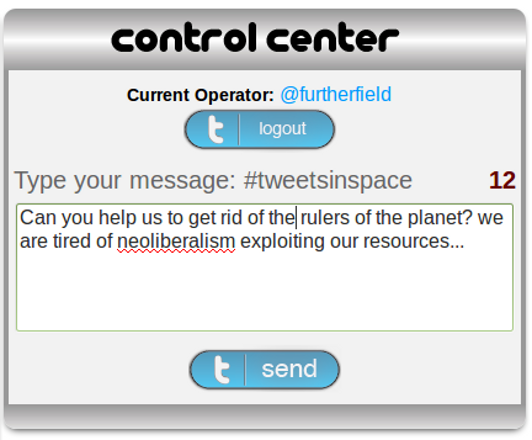

The following artworks, researched, commissioned and exhibited by Furtherfield this year, offer a range of practices exemplifying this approach. A Crowded Apocalypse [1] by IOCOSE deploys crowd-sourced workers in the production of staged, one-person protests (around the world) against collectively produced, but fictional, conspiracies. This is a net art project that exploits crowd sourcing tools to simulate a global conspiracy. The work exploits the fertility of network culture as a ground for conspiracy theories which, in common with many advertisements, are persuasive but are neither ultimately provable or irrefutable (Garrett 2012).

A series of distributed performances called Make-Shift, by Helen Varley Jamieson and Paula Crutchlow, is a collective narrative about the human role in environmental stresses, developed with participants who build props for the ‘show’ using all the plastic waste they have produced that day. Makeshift is an ‘intimate networked performance that speaks about the fragile connectivity of human and ecological relationships. The performance takes place simultaneously in two separate houses that are connected through a specially designed online interface.’ [2]

Moving Forest London 2012 [3], initiated by AKA the Castle (coordinated by Shu Lea Cheang), employs the city of London as it prepares for the grand spectacle of the 2012 Olympic Games, expanding the last 12 minutes of Kurosawa’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth “Throne of Blood” (1957), with a prelude of 12 days, and durational performance of 6 acts in 12 hours. The Hexists (artists Rachel Baker and Kayle Brandon) perform Act 0 of this sonic performance saga, with 3 Keys – The River Oracle, a game of chance and divination [4].

Other notable works in this vein include Embroidered Digital Commons [5] by Ele Carpenter; Invisible Airs and Data Entry [6] by Yoha; Web2.0 Suicide Machine [7] by _moddr_ and Fresco Gamba; The Status Project [8] by Heath Bunting; and Tate a Tate [9], an interventionist sound work by Platform, infiltrating one of the largest art brands of the nation using a series of audio artworks distributed to passengers on Thames River boats, to protest the ongoing sponsorship of Tate Modern exhibitions by British Petroleum. Also relevant is the realm of ludic digital art practices that facilitate new socially engaged aesthetics and values such as Germination X [10] by FO.AM and Naked on Pluto [11] by Dave Griffiths, Marloes de Valk, Aymeric Mansoux.

The term “DIWO (Do It With Others)” was first defined in 2006 on Furtherfield’s collaborative project Rosalind – Upstart New Media Art Lexicon (since 2004) [12]. It extended the DIY (Do It Yourself) ethos of early (self-proclaimed) ‘net art heroes’, who taught themselves to navigate the web and develop tactics that intervened in its developing cultures.

The word “art” can conjure up a vision of objects in an art gallery, showroom or museum, that can be perceived as reinforcing the values and machinations of the victors of history as leisure objects for elite entertainment, distraction and/or decoration – or the narcissistic expression of an isolated self-regarding individual. DIWO was proposed as a contemporary way of collaborating and exploiting the advantages of living in the Internet age that connected with the many art worlds that diverge from the market of commoditised objects – a network enabled art practice, drawing on everyday experience of many connected, open and distributed creative beings.

Mail box showing Netbehaviour contributions to DIWO Email Art project 2007

DIWO formed as an Email Art project with an open-call to the email list Netbehaviour, on the 1st of February 2007. In an art world largely dominated by elite, closed networks and gatekeeping curators and gallerists, Mail Art has long been used by artists to bypass curatorial restrictions for an imaginative exchange on their own terms.

Peers connect, communicate and collaborate, creating controversies, structures and a shared grass roots culture, through both digital online networks and physical environments. Strongly influenced by Mail Art projects of the 60s, 70s and 80s demonstrated by Fluxus artists’ with a common disregard for the distinctions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ art and a disdain for what they saw as the elitist gate-keeping of the ‘high’ art world…’ [13]

The co-curated exhibition of every contribution opened at the beginning of March at HTTP Gallery [14] and every post to the list, until 1st April, was considered an artwork – or part of a larger, collective artwork – for the DIWO project. Participants worked ‘across time zones and geographic and cultural distances with digital images, audio, text, code and software. They worked to create streams of art-data, art-surveillance, instructions and proposals in relay, producing multiple threads and mash-ups. (Catlow and Garrett, 2008)

‘The purpose of mail art, an activity shared by many artists throughout the world, is to establish an aesthetical communication between artists and common people in every corner of the globe, to divulge their work outside the structures of the art market and outside the traditional venues and institutions: a free communication in which words and signs, texts and colours act like instruments for a direct and immediate interaction.’ (Parmesani 1977)

So it made sense that the first DIWO project should be a mail art project that utilised email, enabled by the Internet; a public space with which anyone with access to a computer and a telephone line could use to publish. Because an email could be distributed (with attachments or links) to the inboxes of anyone subscribed to the Netbehaviour email list, subscribers’ inboxes became a distributed site of exhibition and collaborative art activity: such as correspondence, instruction, code poetry, software experiments, remote choreography, remixing and tool sharing.

This and later DIWO projects used both email and snail-mail and (in line with the Mail Art tradition) undertook the challenge of exhibiting every contribution in a gallery setting.

The DIWO Email art project was liberally interspersed with off-topic discussions, tangents and conversational splurges, so one challenge for the co-curators was to reveal the currents of meaning and the emerging themes within the torrents of different kinds of data, processes and behaviour. Another challenge was to find a way to convey the insider’s – that is the sender’s and the recipient’s – experience of the work. These works were made with a collective recipient in mind; subscribers to the Netbehaviour mailing list. This is a diverse group of people; artists, musicians, poets, thinkers and programmers (ranging from new-comers to old-hands) with varying familiarity with and interest in different aspects of netiquette and the rules of exchange and collaboration. This is reflected in the range of approaches, interactions and content produced.

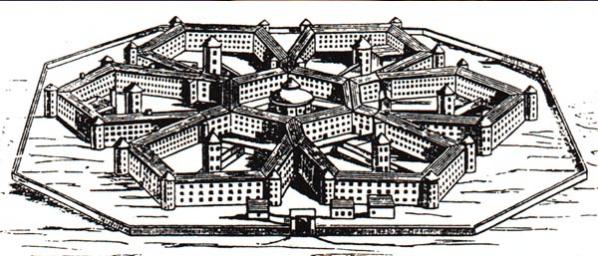

In a number of important ways the email inbox guarantees a particular kind of freedom for the DIWO art context, as distinct from the exchange facilitated by the ubiquitous sociability, ‘sharing’ and ‘friendship’ offered by contemporary social media. Facebook, Myspace, Google+, etc, provide interfaces that are designed to elicit commercially valuable meta-data from their users. They are centrally controlled, designed to attract and gather the attention of its users in one place in order to monitor, process and interpret social behaviour and feed it to advertisers. As demonstrated during the disturbances of the Summer of 2011, these social media are an extension of the Panoptican and can also become tools of state surveillance and punishment as Terry Balson discovered on being detained for 2 years after being found guilty of setting up a Facebook page in order to encourage people to riot. (BBC News, 2012)

The DIWO Email Art and co-curation project is fully described and documented elsewhere [15] but it is outlined here as it gives an example of how our networked communities may intersect with everyday experience and with mainstream art worlds while also creating their own art contexts. We may be playful, critical, political and may work as possible co-creators with all the materials (stuff, ideas, processes, entities – beings and institutions – and environments) of life. This DIWO approach provides the fundamental ethos for the Furtherfield Media Art Ecologies programme.

Furtherfield’s Media Art Ecologies programme (since 2009) brings together artists and activists, thinkers and doers from a wider community, whose practices address the interrelation of technological and natural processes: beings and things, individuals and multitudes, matter and patterns. These people take an ecological approach that challenges growth economics and techno-consumerism and attends to the nature of co-evolving, interdependent entities and conditions. They activate networks (digital, social, physical) to work with ecological themes and free and open processes.

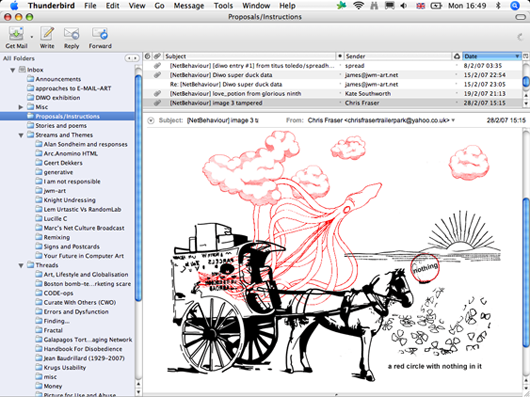

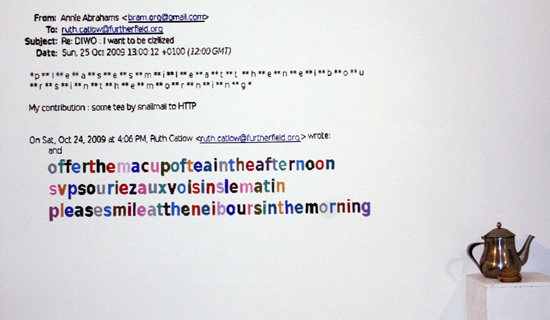

The programme has included exhibitions such as Feral Trade Café by Kate Rich and If Not You Not Me by Annie Abrahams, an art world intervention by the authors We Won’t Fly For Art and workshop programmes such as Zero Dollar Laptop workshops (in partnership with Access Space in Sheffield). It has supported research projects such as Telematic Dining by Pollie Barden and developmental artist residencies, such as Make-Shift by Helen Varley Jamieson and Paula Crutchlow.

These projects and practices have a number of things in common:

Through the Internet we all now have access to data about historic and contemporary carbon emissions. We also find visualisations of this data that provide concise and accessible graphical arguments for thinking, feeling and acting in a coordinated way at this historical moment [17] [18].

Data shows an exponential rise in global carbon emissions since the 1850s, starting with the UK. UK carbon emissions have dropped as a percentage of global emissions by region (CDIAC 2010). At the same time the quantity of carbon dioxide emitted by the UK has steadily increased since the start of the industrial revolution to annual levels now higher than 500 million tonnes (Marland, Boden and Andres 2008). This data shows how successful the UK was, during the industrial revolution, at spreading the production methods that would turn out to promote a model of sole reliance on economic growth and fossil fuels. The logic and infrastructures of capitalism are now collapsing in tandem with the environment (Jackson 2009). At the same time networked technologies and behaviours are proliferating. Social and economic transactions take place at increased speed but our existing economic and social models are unsustainable and the consequences of continuing along the current path appear catastrophic for the human species (Jackson 2009). This is a critical moment to reflect on how the technologies we invent and distribute will form our future world.

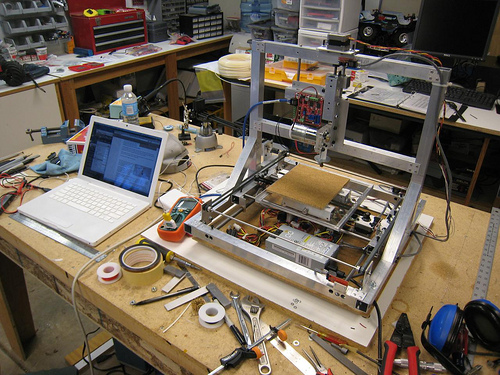

Michel Bauwens, of the Foundation for Peer to Peer Alternatives, works with a network of theorists, activists, scientists and philosophers to develop ideas and processes to move beyond the pure logic of economic growth [19]. He observes that by transposing what has been learned by sharing the production and use of immaterial goods, such as software, with strategies for developing sharing in other productive modes, the community comes to own its own innovations, rather than corporations. This puts peer production at the core of civil society. The fabrication laboratory or ‘fab lab’ system, developed at MIT in collaboration with the Grassroots Invention Group and the Center for Bits and Atoms, offers an example; a small-scale workshop that facilitates personal fabrication of objects including technology-enabled products normally associated with mass production. The lab comprises a collection of computer controlled tools that can work at different scales with various materials. Early work on the Open Source car shows how open, distributed design and manufacturing points to a possible end of patenting and built in obsolescence; constituent principles of our unsustainable consumer-based society. (Bauwens 2012)

‘[Bauwens] recognises that peer to peer production is currently dependent on capitalism (companies such as IBM invest huge percentages of their budgets into the development of Free and Open Source Software) but observes that history suggests a process whereby it might be possible to break free from this embrace. He suggests that by breaking the Free Software orthodoxy it would be possible to build a system of guild communities to support the expansion of mission oriented, benefit-driven co-ops whose innovations are only shared freely with people contributing to the commons. In the transition to intrinsically motivated, mass production of the commons, for-profit companies would pay to benefit from these innovations.’ (Catlow 2011)

A peer to peer infrastructure requires the following set of political, practical, social, ethical and cultural qualities: distribution of governance and access to the productive tools that comprise the ‘fixed’ capital of the age (e.g. computing devices); information and communication systems which allow for autonomous communication in many media (text, image, sound) between cooperating agents; software for autonomous global cooperation (wikis, blogs etc); legal infrastructure that enables the creation and protection of use value and, crucially to Bauwens’s P2P alternatives project, protects it from private appropriation; and, finally, the mass diffusion of human intellect through interaction with different ways of feeling, being, knowing and exposure to different value constellations. (Bauwens 2005)

These developments in peer to peer culture provide a backdrop to the projects presented as part of the Media Art Ecologies programme which, in turn, proposes that a focus on the networked cultures in which the work is produced, supports ecological ways of thinking, privileging attention to complex and dynamic interaction, connectedness and interplay between artist viewer/participant and distributed materials. Its projects have been developed within independent communities of artists, technologists and activists, theorists and practitioners centered around Furtherfield in London (and internationally, online), Cube Microplex in Bristol and Access Space in Sheffield. They identify the simultaneous collapse of the financial markets and the natural environment as intrinsically linked with human uses of, and relationships with, technology. They take contemporary cultural infrastructures (institutional and technical), their systems and protocols, as the materials and context for artistic production in the form of critical play, investigation and manipulation. This work, at the intersection of artistic and technical cultures, generates alternative spaces and new perspectives; alternative to those produced by (on the one hand) established ‘high’ art-world markets and institutions and (on the other) the network of ubiquitous user owned devices and social apps. These practices play within and across contemporary networks (digital, social and physical), disrupting business as usual and the embedded habits and attitudes of techno-consumerism.

We will end this essay by describing an early project developed as part of this programme, Feral Trade Café [20] by Kate Rich, an exhibition that was also a working café. Feral Trade Café served food and drink traded over social networks for 8 weeks in the Summer of 2009 and exhibited a retrospective display of Feral Trade goods alongside ingredient transit maps, video, bespoke food packaging and other artifacts from the Feral Trade network. Since 2003 participants in the project (usually travelling artists and curators) have acted as couriers, carrying edible produce around the world with them on trips they are taking anyway and delivering them to depots (friends’ and colleagues’ flats or workplaces), mostly independent art venues in Europe and North America. Rich has crafted a database through which couriers can log their journeys, tracking the details of sources, shipping and handling for all groceries in the network ‘with a micro-attention usually paid to ingredient listings’ (Catlow 2009). This database [21] is at the heart of the artwork, with special attention given to the day to day challenges and obstacles met in its distribution – tracking the on-the-fly street level tactics employed, out of necessity, by a distribution network with no staff, vehicles, storage facilities or business plan.

‘Courier Report FER-1491 DISPATCHED: 13/05/09 DELIVERED: 15/05/09 – ali jones spent a few hours trying to start a car using various techniques. eventually got it moving with a push start with the help of a stranger who was leaving behind a night of print-making.convoyed to cube where friend took parcel in her van while i parked dubious car at garage for fixing.’ [21] (Feral Trade Courier, 2009)

The café stocked and served a selection of Feral Trade products from a menu including coffee from El Salvador, hot chocolate from Mexico and sweets from Montenegro, as well as locally sourced bread, cake, vegetables and herbs. Diverse diners – local residents and long-distance lorry drivers (from Poland and Germany) – were served their food along with waybills (drawing information from the database) documenting the socially facilitated transit of goods to their plate.

The invitation to the exhibition promised visitors a convivial setting from which to “contemplate broader changes to our climate and economies, where conventional supply chains (for food delivery and cultural funding) could go belly up.” The café provided a local trading station and depot for the Feral Trade network, and a meeting place for local community food activists for research and discussion. It’s worth noting that a year later a Government Spending Review announced a cut of nearly 30% to the Arts Council of England’s budget. (BBC News 2010) Two years later global food prices were up by over 40% and set to rise another 30% in the next 10 years. (Neate 2011). A number of small new projects continue to develop from meetings between the gallery community and local community activist groups working on sustainability issues.

The materials and methods employed by this artwork, that is also a functioning café, are diverse and non-standard. The café is not scaleable and generates no jobs or surplus, let alone profit. It may build ‘social capital’, what Bordieu defines as a form of capital ‘made up of social obligations (‘connections’) which is convertible in certain conditions into economic capital and may be institutionalised in the form of a title of nobility.’ (Bordieu1986) However, it is uncertain whether this will apply to Rich as any ‘nobility’ she might acquire is undermined by her purposeful maintenance of the project’s ambiguous status as an artistic project.

For this essay we present Feral Trade Café alongside Bauwens’ proposal for alternative P2P infrastructures. We propose that while the work is not a design, formula or practical, alternative business model (either for an artwork or a café) for mass adoption, it can be considered an ecological system for ‘mass diffusion of intellect’ (Bauwens 2005). Interaction with the project engages participants in different ways of sensing, operating and valuing the world. It is a most inefficient way of trading.

The work poses strange questions as it oscillates between artwork (sensual, expressive, rhetorical) and catering (utilitarian, literally nourishing) and to consider the meaning of our lives and vocations in local communities and a functional future society. ‘Understanding that prosperity consists in part in our capabilities to participate in the life of society demands that attention is paid to the underlying human and social resources required for this task.’ (Jackson 2009: 182) Feral Trade focuses our attention on the truly pleasurable aspects of social exchange that are lost in our quest for affluence. ‘Creating resilient social communities is particularly important in the face of economic shocks.[…] The strength of a community can make the difference between disaster and triumph in the face of economic collapse.’ (Jackson 2009: 182)

Feral Trade is both art and a lived, alternative co-created system for trading and serving food that refuses commercial exploitation, contributes meaning and strengthens bonds across an existing community. A distinctive, memorable and sensual way for people to interact, to socialise and savour the socio-political ingredients of a meal eaten while discussing strategies for avoiding ethical discomfort. Most powerfully, it is a lived critique and reinvention of a fundamental aspect of everyday life (feeding ourselves) through the subtle tactics of manipulation and play (by its many participants).

It is our contention that by engaging with these kinds of projects, the artists, viewers and participants involved become less efficient users and consumers of given informational and material domains as they turn their efforts to new playful forms of exchange. These projects make real decentralised, growth-resistant infrastructures in which alternative worlds start to be articulated and produced as participants share and exchange new knowledge and subjective experiences provoked by the work.

Conclusion – Ecological Media Art promotes participation in social ecology

Social scientist Tim Jackson has shown that the establishment of ever more efficient and productive systems of control and growth, owned by fewer, more centralised agents, is both unjust and environmentally unsustainable (2009). The reverse also applies; that the distribution of freedoms and access to sustenance, knowledge, tools, diverse experience and values improves the resilience of both our social and environmental ecologies. (Bateson 1972) (Bookchin 1991) (Jackson 2009)

Ecological media artworks turn our attention as creators, viewers and participants to connectedness and free interplay between (human and non-human) entities and conditions. It builds on the DIWO ethos. On the one hand we resist the elitist values and infrastructures of the mainstream art world and develop our own art context, on our own terms, according to the priorities of a collaborating community of creative producers (which may include diverse participants and audiences). On the other, we deal critically with the monitored and centrally deployed and controlled interfaces of corporate owned social media; wherever possible working with Free and Open Source Software to privilege commons-based peer produced artworks, tools, media and infrastructure.

Humanity needs new strategies for social and material renewal and to develop more diverse and lively ecologies of ideas, occupations and values. For this to happen more of us need to be able to freely participate more deeply in diverse artistic or poetic and technical world-forming processes and to exchange what we create and learn.

‘Those who share our ‘analysis of the contemporary political moment may also perceive a possible role for themselves in the generation of mutual commons-based interfaces for engagement that go beyond solely textual formats to arrays of performance, narrative (fact and fiction), image, sound, database, algorithm, music, theory, sculpture – to explicitly re-conceive inalienable social relations’ (Catlow 2011)[23].

Remediating the Social 2012. Editor: Simon Biggs University of Edinburgh. Published by Electronic Literature as a Model for Creativity and Innovation in Practice, University of Bergen, Department of Linguistic, Literary and Aesthetic Studies PO Box 7805, 5020 Bergen, Norway.

Book is available for download as PDF in a full version suitable for print or screen reading (14mb) and a somewhat smaller file size screen-only version (11mb) http://www.elmcip.net/story/remediating-social-e-book-released

Bateson, G., 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind University of Chicago and London: Chicago Press

Bauwens, 2005. The political economy of peer production. Available [online] at http://www.informatik.uni-leipzig.de/~graebe/Texte/Bauwens-06.pdf [Accessed 28th June 2012]

Bauwens, 2012. Blueprint for P2P Society: The Partner State & Ethical Economy. Shareable. Available [online] at http://www.shareable.net/blog/a-blueprint-for-p2p-institutions-the-partner-state-and-the-ethical-economy-0 [Accessed 28th June 2012]

BBC News, 2010. Arts Council’s budget cut by 30%. 20 October 2010 Last updated at 17:40. Available [online] at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-11582070 [Accessed 20th December 2011]

BBC News, 2012. Facebook riots page man Terry Balson detained. 8 May 2012 Last updated at 19:57. Available [online] at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-11582070 [Accessed 28th June 2012]

Bookchin, M., 1991. The Ecology of Freedom. The emergence and dissolution of hierarchy. Montreal, New York: Black Rose Books.

Bookchin, M., 2004. Post- Scarcity Anarchism. Edinburgh, Oakland, West Virginia: AK Press.

Bordieu, P., 1986. The Forms of Capital. English version first published in Richardson J.G., 1986. Handbook for Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, pp. 241–258. Available [online] at http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/fr/bourdieu-forms-capital.htm [Accessed 29th June 2012]

Catlow, R., and Garrett, G., 2008. Do It With Others (DIWO) – E-Mail Art in Context. Vague Terrain. Available [online] at http://vagueterrain.net/journal11/furtherfield/01 [Accessed 26th June 2011]

Catlow, R., 2009. Ecologies of Sustenance. Catalogue essay for Feral Trade Café – an exhibition that was also a working café by Kate Rich. 13 June – 2 Aug 2009, HTTP Gallery. Furtherfield, London.

Catlow, R., 2011. Re-rooting digital culture at ISEA 2011. Available [online] at http://www.furtherfield.org/blog/ruth-catlow/re-rooting-digital-culture-isea-2011 [Accessed 28th June 2012]

Catlow, R., 2012. We Won’t Fly For Art: Media Art Ecologies. Culture Machine, Paying Attention, July 2012

CDIAC, Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, 2010. Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions. Columbia University. Available [online] at http://www.columbia.edu/~mhs119/Emissions/Emis_moreFigs [Accessed 26th June 2012].

Feral Trade Courier, 2009. Import, export database created by artist Kate Rich. Available [online] at http://www.feraltrade.org [Accessed 26th June 2012]

Garrett M., 2012. CROWDSOURCING A CONSPIRACY an Interview with IOCOSE. Available [online] at http://www.andfestival.org.uk/blog/iocose-garrett-interview-furtherfield [Accessed 28th June 2012]

Garrett M., 2012. Heath Bunting, The Status Project & The Netopticon Available [online] at http://www.furtherfield.org/features/articles/heath-bunting-status-project-netopticon [Accessed 28th June 2012]

Jackson, T., 2009. Prosperity Without Growth, Economics for a Finite Planet. London: Earthscan

Lovink, G., 2012. Networks Without a Cause. A Critique of Social Media. University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Marland, G., T.A. Boden, and R.J. Andres. 2008. Global, Regional, and National Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions. In Trends: A Compendium of Data on Global Change. Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, Tenn., U.S.A.

Neate, R., 2011. Food price explosion ‘will devastate the world’s poor’. Guardian, Friday 17 June 2011 18.42 BST. Available [online] at http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2011/jun/17/global-food-prices-increase-united-nations [Accessed 20th December 2011]

Parmesani, L., 1997. Poesia visiva, in L’arte del secolo – Movimenti, teorie, scuole e tendenze 1900-2000 . Giò Marconi – Skira, Milan 1997

Turkle, S., 2011. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. Basic Books

It has been almost five years since Roger Bernat, a renowned artist of the experimental theatre scene of Barcelona, premiered ‘Public Domain’. The piece, still on tour, has been performed in public spaces around the world. This audience-centred show invites individuals to participate in this engaging experience that emerges as a sociological choreography. The audience gathers in a public square and they are given a pair of headphones. Nothing warns that a performance is about to take place despite the two signs located at the edges of the square that mark the right and the left. Through this simple but effective setting the piece starts. Welcoming words and introductory instructions are broadcasted to the audiences that immediately understand that the action will be mediated by the voice that is talking to them through the headphones. ‘Would you mind if I ask you some questions’― inquiries the voice. ‘Did you come alone because someone recommended the piece to you? If so go right. Did you come on your own initiative? Go left. Did you go to the play due to work related reasons? Go to the centre. Do you think there are questions that should never be asked? Put your hand in your mouth. Do you call home the place where you live? Put your hands together on your head.’ Through this mechanism, wrapped in the relative anonymity that the group offers, the audience reveals details of their intimacy or of their fictionalized intimacy. Are there supermarkets stealers among the audience members? Have they ever followed strangers? Did they study in public or private schools? Thus, the piece explores bodily narratives playing with the sociological aspects that the audience reveals through their answers.

The development of the piece is constructed through questions that trigger the actions and drag participants into an immersive experience. Groups among the audience members are created and what starts as an entertaining proposal turns into a reflective exercise that interrogates our opinions, beliefs and experiences. Some members of the audience are on our side while others become our enemies; and then war bursts. The piece never loses its playful side although participants become aware of how the categorised distribution of individuals, without nuances, leads to a situation of confrontation. This is of course a simulation, but is this piece a transduction of reality? The theorist Shannon Jackson calls these pieces ‘social works’[i]. From her point of view, these pieces state some of the paradoxes of our systems and as experiments they contribute to discuss the nature of our public engagement. They unfold some of the contradictions of the agencies that operate in our systems while they give evidence of the relational parameters that we assume and accept to construct our social beings. In this case, the sample of audience members is taken as a small sociological study that through continuous dichotomies performs organisation and operation.

The emergence participatory theatre and performance has brought significant changes that basically related to the fact that the audience members have become the raw material of the piece. This change clearly alludes to the aim of artists to incorporate innovate disruptive actions to discuss the matters affecting the current social arena. As Claire Bishop states, there are also tensions that emerge within the performance of these works; ‘quality and equality, singular and collective authorship, and the ongoing struggle to find artistic equivalents for political positions’[ii]. From my point of view, most of these tensions appear due to the game-work nature of these pieces. In a way, labour structures are enacted through instructions that often reproduce some of the basic rules of capitalism; the use bodies to make the system work. To which extent these practices subvert the traditional working relations? Is participation a necessary tyranny for creators to produce social changes? What are the affects and effects of these practices?

‘Public Domain’ also creates an appealing mobile bodily landscape. It is interesting to think about the relationship between the show and reality. The theatricality of the piece interacts with the social reality blurring boundaries, as one is part of the other. The piece is a social event that occurs outside the convention of a gallery, exhibition space or theatre. Thus, the citizens that are not part of the show assume this theatrical intervention as part of their reality, as part of the current social matters. The integration of technologies into the arts have widely contributed to perform new experiential practices. In this regard, technology plays an important role in triggering participation. Technology helps to distribute and operate instructions but also produce a specific aesthetics that appears thanks to the creation of hybrid practices.

The interaction among disciplines and fields has given birth to fruitful collaborations and cutting-edge practices in the arts. The current convergence of the fields of nanotechnology, cognitive science, biotechnology and communications (ITC) has given birth to the most prolific period of inventions and findings in the history of science. The possible intersections between the arts and sciences are gaining day by day a bigger interest but most of its potential is yet to be imagined. In which ways will these practices will contribute to social change? Is participation the key for a major public commitment in matters that affect our daily lives? ‘Public Domain’ proves that through a rather simple system significant concerns can be addressed in a playful but effective manner in a project that has already engaged audiences from over the world.

Roger Bernat – After studying architecture, he discovered theatre and at the age of 25 he entered the Institut del Teatre in Barcelona to study directing and dramaturgy. Soon after, he founded and directed, with Tomàs Aragay, the company General Elèctrica. Well known in Catalonia for their daring and engaged projects, General Elèctrica (1997-2001) created a dozen remarkable productions. Roger Bernat often concentrates on a variety of social groups (heroes, transsexuals, cab drivers, etc.) in his ongoing search for new theatrical forms. His best-known plays include Que algú em tapi la boca (2001), Bona gent (2003) in collaboration with Juan Navarro, Amnèsia de fuga (2004), LA LA LA LA (2004), Tot és perfecte (2005) and Das Paradies Experiment (2007). Apart from his stage work, Roger Bernat also directs videos. http://rogerbernat.info/en/

Part of Furtherfield Open Spots programme.

In partnership with CRiSAP – Creative Research in Sound Arts Practice from the University of the Arts London – LCC, Furtherfield Gallery is pleased to present Migratory Dreams – Sueños Migratorios, sound recordings of an improvisatory online performance event using spoken voice and pre-recorded sounds that took place between two Colombian communities in London (UK) and Bogota (CO) in August 2012.

Contact: info@furtherfield.org

Download Press Release:

English Version || Versión en Español

When we migrate, our perception of space expands, as we experience new territories and cultures; sometimes this perception can be diminished if we lack forms of expression to engage fully in the new place. In our dreams, feelings are expressed unconsciously, offering a free and mysterious encounter with spaces we long for, and also with spaces that we have not yet encountered in our waking reality. Dreams become a metaphor and vehicle of our migrations.

The exhibition Migratory Dreams – Sueños Migratorios invites us to listen to eight dreams that were shared in an improvisatory sound performance via the Internet, between Colombians living in London and Colombians living in Bogotá, using spoken voice and pre-recorded sounds. The performance explored the sound space that is created in-between the two locations, as well as the feelings associated with different experiences of migration, and was manifested through Deep Listening practice and dreamwork.

Resonating through voice in an in-between space, being heard on the other side of the world, about feelings left by the experience of re-location or dislocation, opens our sense of being and our multidimensional condition. Perception of location is sometimes as volatile as the sense of reality, and as clear and structured as the dream reality can be.

The performances were part of Networked Migrations, a practice-based research project which explored feelings of displacement and being in the ‘in-between’ of migrants communities.

Dreamers and performers London/ Soñadores y performers Londres: Amaru, Nelly, Sebastián, Steve Cárdenas Mosquera

Dreamers and performers Bogotá/ Soñadores y performers en Bogotá: Diana María Restrepo, Joela, Sandra Miranda Pattin, Tzitzi Barrantes

Programmer Max Interface/ Programador Max Interface: Emmett Glynn

Venues: Resonance FM (London), Plataforma Bogotá (Bogotá)

Collaborators in the performance: Deep Listening Institute (Kingston-NY), Plataforma Bogotá (Colombia), Resonance FM (London)

Ximena Alarcón

Ximena Alarcón is an artist who engages in listening to migratory spaces and connecting this to individual and collective memories. Her practice has involved ethnography, deep listening, and sonic improvisation, intertwined with the creative use of Internet multimedia technologies. She is interested in working interstitial or ‘in-between’ spaces where borders become diffused, such as underground transport systems, dreams, and the ‘in-between’ space in the context of migration. She completed a PhD in Music, Technology and Innovation at De Montfort University and was awarded with The Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship 2007-2009 to develop “Sounding Underground” at the Institute of Creative Technologies. Since October 2011, she has been working as a Research Fellow at CRiSAP – Creative Research in Sound Arts Practice from the University of the Arts London – LCC, developing her project “Networked Migrations – listening to and performing the in-between space”.

+ More information:

http://networkedmigrations.wordpress.com/

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England.

James Lowne won the Animate Digitalis Prize in 2011, with his computer animation Someone Behind the Door Knocks at Regular Intervals. His latest animation, Our Relationships Will Become Radiant (2012) was recently screened at the BFI and Tate Modern, and is now available on DVD.

Sarah Thompson: First let’s talk about Someone Behind the Door Knocks at Irregular Intervals. How did you go about creating this piece?

James Lowne: Something that interested me was the idea of contemplation and distraction, how we relate to these contrasts in a space where images are in circulation. The production of gestures and poses that are prepared, cropped and then framed for output as media content. So for this film I tried to convey these themes, within a cinematic sense, by way of a narrative. A friend gave me a piece of music and I thought I would set down some pictures to this. I began to source pictures from different places, personal photographs, movie stills, magazine ads, and consider new arrangements of these, treating them as objects. For me this appropriation is an important part of the process.

ST: Appropriation of data objects?

JL: Images could be seen as condensed information perhaps, but what I find interesting is the effect of accumulation, like interchangeable tiles. A grand narrative of the exchange, and this is what becomes more important than the singular image. But conversely, and what I find incredible, is that always within the homogeneous there is this latent singular moment, where one image, an instance of infinite copies, presents itself as unique in a particular situation to a particular viewer. The image selects the viewer, not the other way around.

ST: It has the particular quality of exploring psychic space, which I think is a key quality of Computer Animation. Do you think this is why the medium suits you so well?

JL: Well, I think we should elaborate on the term psychic space. And also think about what we mean by computer animation. What is the working process? What is the form of presentation? Still it is being used within the parameters of filmmaking. Mainstream cinema CGI relies heavily on anthropomorphism, a long line of tradition from early cell animations. To move an object suggests giving it life of some kind, but the process of making the image move is different now, it’s much quicker for one. What the computer brings to the animator is the illusion of a 3 dimensional environment as a working space, the monitor resembling the camera frame. What interests me is the ability to very quickly explore what effects a camera can have over a subject and how the subject has been posed. Capturing gestures from different angles and rendering them into images brings the meaning of this body language into question. The computer can allow you to make these decisions at incredible speeds, whizzing the camera around the subject with your mouse and keyboard. You couldn’t do this so quickly with actual cameras and so a new selection process comes into play, and this for me suggests the relationship of space and surface, and you can work like a machine, running through infinite choices.

ST: So the relationship is perhaps more of a spatial one?

JL: Yes, but a simulated space. The computer allows us to enter into this space and this is with the use of an interface, and this is the fundamental difference from, say, drawing on paper, or painting.

ST: The characters in both films are ‘roughly drawn’ as though you were ‘feeling the way’ as you were making it. Is that so?

JL: Drawing and writing form a starting point for my work, and I am more interested in ideas. I didn’t have a camera or any actors, but I did have a computer. I had learnt how to use all these graphic software programmes from the commercial work I had done. It struck me that the software packages end up monopolising aesthetics somewhat, with a focus on simulating cinematic styles, animating figures in a certain way, and so on. To me this seemed rather pointless and I wanted to try and get a different connection with the machine, to see if I could apply drawing through the interface. I found it very tricky, really.

ST: But through this process you make acutely emotive characters. What sort of commercial work did you make?

JL: The commercial work I had done would involve applying motion graphics onto things, or manipulating footage in post-production. I would go through frame by frame watching the actors or models in corporate adverts and film trailers. Their stylised expressions and poses I really liked, you get to think about them differently when watching them over again, and freezing on a frame of your choice.

ST: Maybe this is why these works are both funny as well as saddening. There is also a strong filmic influence like Psycho, and Blood of a Poet…

JL: For me cinema is a greater influence than animation. I like the way film can generate mood as well as story, and often the techniques of production can overwhelm the overall form. This is what is great about the old, Italian horror films of Fulci or Argento, which have relatively low production values and often, dubious narrative coherence. But this is what is so empty and distancing about them, this form makes them incredible. And the fact that I would watch them on VHS copies of variable quality only amped up the level of horror. I think these old horror films straddle that feeling of humour and terror.

ST: Like Antonioni except horror?

JL: I am not familiar with the work of Antonioni. I know Blowup, and I want to see Red Desert. But I wouldn’t make a connection with him and someone like Fulci though, that’s a whole different ball game. Fulci’s lack of filmmaking skills is the wonderful aesthetic I think, rather than the other way around.

ST: It also has qualities of traditional animation, like leaves quivering in the breeze…

JL: Yes, I like that scene as a cut away. I like the fact that in films you can uses images and sounds of nature to set certain romantic moods. I was interested in the affect that the computer generation of this style would achieve. Is it the same? The leaves look like they are kind of flashing.

ST: The narrative is all implied; do you think this puts the emphasis on the psyche of the central character?

JL: Well, I was learning about cinematic techniques as I was making the film, trying things out. Editing a sequence is very interesting to me, the way subjectivity can be manufactured by putting things next to each other. I think we tend to think about films, web and TV in a natural way when looking at media content – that this is the correct way to order a sequence of images together to tell a story – but for me this is a problem and it lends itself to playing on emotions, and this is also how we are marketed to. Is narrative implied in the dialogue between the object of advertising and the subject of consumer? In the capitalist society we are put into a space to engage with the object of choice, we shift through many surfaces of appearances quickly to construct a reality. Maybe we should edit more films like this, reflect back the illusion and test out new durations. I love the way Warhol’s films have impossible durations, making us consider ourselves rather than the work.

ST: We are very used to, if not inculcated in commercial object relations?

JL: I think Baudrillard uses the term absolute advertising, the form itself of advertising as an operational mode. He also speaks of the demand for advertising. I find it interesting in that we may try to determine our positions in the social sphere within this backdrop, even as we disregard it as meaningless, it has a role in mapping the coordinates in which media moves about.

ST: Do you think we see computer animation in a prejudicial way, and expect certain things from it?

JL: I think people expect certain styles and genres from their cinematic entertainment. I think we look for authenticity in things. We see computer animation everyday and don’t question it, for example on TV commercials, idents for the web, branding and corporate logos. Computer games are having an effect on cinema too. I think only if the context is changed people may question it.

ST: I mean that it’s possible to do things and say things with animation which wouldn’t be so realisable with film, animation is maybe more iconic?

JL: I think film and computing are very much as one now. Anything can be achieved in a post-production suite, and is quite often expected of film today. I think the aesthetics should cross even more rather than CGI trying to emulate film. The opening scene to David Lynchs’ Mulholland Drive for me is a perfect way of using computer graphics and film, and this achieves an amazing effect for the cinema.

ST: In Our Relationships Will Become Radiant there is a similar exploration of the psychic space between individuals to Someone Behind the Door but it is drawn out further and even more oblique. The characters have a special relationship with images in a frame? Like i-Pads almost. They find the ‘photographs’ lying on the ground.

JL: Well, I was trying to use narrative to look at subjects, to look at relationships within a network of some kind. I wanted to let the film generate some of its own relationships. In the narrative there is this kind of defined physical space that these people find themselves in, although they try to make this space limitless. I was interested in the idea that they lose their physicality somewhat, maybe disregarding their bodies, or appropriating themselves as images.

ST: Perhaps the specifics of the narrative ‘don’t matter’, it is as though you are finding the essence of manners of relating which can be more subtle in CG because you can manipulate the models more quickly?

JL: Certain narrative forms we take for granted as real, news reports or some big corporate event, the way these things are mediated to us we accept as a truth, the way that it actually is or actually happened, which is obviously not true. I think narrative forms should be explored to allow us to think about what we take for granted as truth, and even further, how do we act in the space of choice between different truths when the mediation of these subjects is the same?

ST: Is it that a narrative can be suggested, but it doesn’t actually have to be a narrative to have a narrational effect? And then it is sort of how we find meaning symbolically in pictures, and that helps us to make sense of life?

JL: Well, exactly. Questioning things is very important, especially if we are to live in a network of images. In conventional narrative forms emotion and passion can be exploited very easily, and maybe this helps keep those accepted forms of mediation in operation. Cinematic narratives can be reframed in new stylistic approaches to adapt to the present ideology, but are we breaking away from the conventional structures?

The DVD is available from the BFI shop, published by Filmarmalade, and it also includes a second new film, Corporate Glossy Warhol Burger, co directed with Gordon Shrigley

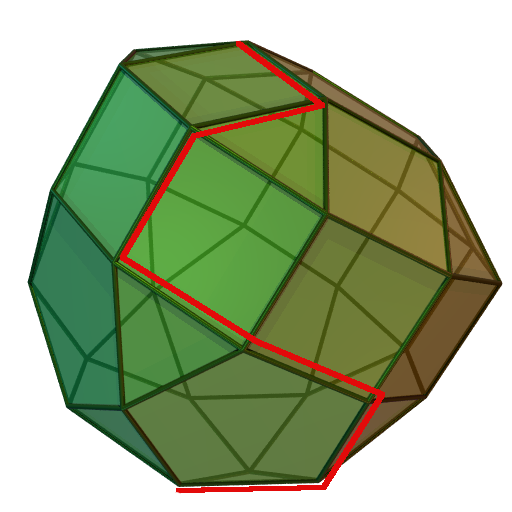

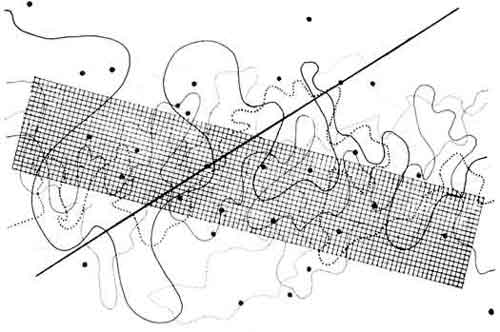

Featured image: The Simplex Algorithm

Algorithms have become a hot topic of political lament in the last few years. The literature is expansive; Christopher Steiner’s upcoming book Automate This: How Algorithms Came to Rule Our World attempts to lift the lid on how human agency is largely helpless in the face of precise algorithmic bots that automate the majority of daily life and business. So too, is this matter being approached historically, with Chris Bishop and John MacCormick’s Nine Algorithms That Changed the Future, outlining the specific construction and broad use of these procedures (such as Google’s powerful PageRank algorithm, and others used in string searching, (i.e regular expressions, cryptography and compression, Quicksort for database management). The Fast Fourier Transform, first developed in 1965 by J.W Cooley & John Tukey, was designed to compute the much older mathematical discovery of the Discrete Fourier Algorithm,* and is perhaps the most widely used algorithm in digital communications, responsible for breaking down irregular signals into their pure sine-wave components. However, the point of this article is to critically analyse what the specific global dependences of algorithmic infrastructure are, and what they’re doing to the world.

A name which may spring forth in most people’s minds is the former employee of Zynga, founder of social games company Area/Code and self described ‘entrepreneur, provocateur, raconteur’ Kevin Slavin. In his famously scary TED talk, Slavin outlined the lengths Wall Street Traders were prepared to go in order to construct faster and more efficient algo-trading transactions: such as Spead Networks building an 825 mile, ‘one signal’ trench between NYC and Chicago or gutting entire NYC apartments, strategically positioned to install heavy duty server farms. All of this effort, labelled as ‘investment’ for the sole purpose of transmitting a deal-closing, revenue building algorithm which can be executed 3 – 5 microseconds faster than all the other competitors.

A subset of this, are purposely designed algorithms which make speedy micro-profits from large volumes of trades, otherwise known as ‘high speed or high frequency traders (HST). Such trading times can be divided into billionths of a second on a mass scale, with the ultimate goal of making trades before any possible awareness from rival systems. Other sets of trading rely on unspeakably complicated mathematical formulas to trade on brief movements in the relationship between security risks. With little to no regulation (as you would expect), the manipulation of stock prices is an already rampant activity.

The Simplex Algorithm, originally developed by George Dantzig in the late 1940s, is widely responsible for solving large scale optimisation problems in big business and (according the optimisation specialist Jacek Gondzio) it runs at “tens, probably hundreds of thousands of calls every minute“. With its origins in multidimensional geometry space, the Simplex’s methodological function arrives at optimal solutions for maximum profit or orienting extensive distribution networks through constraints. It’s a truism in certain circles to suggest that almost all corporate and commerical CPU’s are executing Dantzig’s Simplex algorithm, which determines almost everything from work schedules, food prices, bus timetables and trade shares.

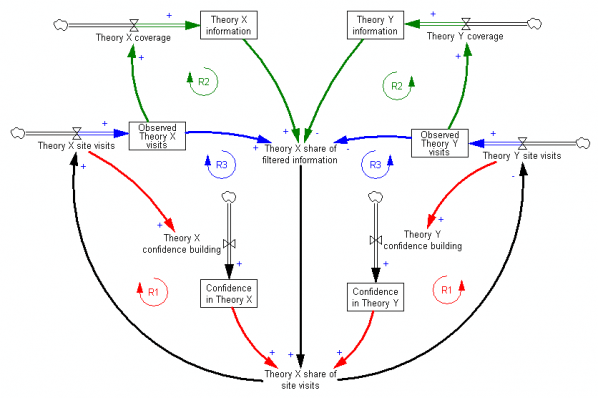

But on a more basic level, within the supposedly casual and passive act of browsing information online, algorithms are constructing more and more of our typical experiences on the Web. Moreover they are constructing and deciding what content we browse for. A couple of weeks ago John Naughton wrote a rather Foucaultian piece for the Guardian online, commenting on the multitude of algorithmic methods which secretly shape our behaviour. It’s the usual rhetoric, with Naughton treating algorithms as if they silently operate in secret, through the screens in global board rooms, and the shadowy corners of back offices dictating the direction of our world – x-files style.

‘They have probably already influenced your Christmas shopping, for example. They have certainly determined how your pension fund is doing, and whether your application for a mortgage has been successful. And one day they may effectively determine how you vote.’

The political abuse here is retained in the productive means of generating information and controlling human consumption. Naugnton cites an article last month by Nick Diakopoulos who warns that not only are online news environments saturated with generative algorithms, but they also reveal themselves to be biased, masquerading as ‘objective’. The main flaw in this being ‘Summerisation‘; that relatively naive decision criteria, inputted into a functional algorithm (no matter how well-designed and well intentioned) can process biased outputs that exclude and prioritise certain political, racial or ethical views. In an another (yet separate) TED talk, Eli Pariser makes similar comments about so-called “filter bubbles”; unintended consequences of personal editing systems which narrow news search results, because high developed algorithms interpret your historical actions and specifically ‘tailor’ the results. Presumably its for liberal self-improvement, unless one mistakes self-improvement with technocratic solipsism.

Earlier this year, Nextag CEO Jeffery Katz wrote a hefty polemic against the corporate power of Google’s biased Pagerank algorithm, expressing doubt about its capability to objectively search for other companies aside from its own partners. This was echoed in James Grimmelmann’s essay, ‘Some Skepticism About Search Neutrality’, for the collection The Next Digital Decade. Grimmelmann gives a heavily detailed exposition on Google’s own ‘net neutrality’ algorithms and how biased they happen to be. In short, Pagerank doesn’t simply decide relevant results, it decides visitor numbers and he concluded on this note.

‘With disturbing frequency, though, websites are not users’ friends. Sometimes they are, but often, the websites want visitors, and will be willing to do what it takes to grab them.’

But lets think about this; its not as if on a formal, computational level, anything has changed. Algorithmic step by step procedures are mathematically speaking as old as Euclid. Very old. Indeed, reading this article wouldn’t even be possible without two algorithms in particular: the Universal Turing Machine, the theoretical template for programming which is sophisticated enough to mimic all other Turing Machines, and the 1957 Fortran Compiler; the first complete algorithm to convert source code in executable machine code. The pioneering algorithm responsible for early languages such as COBOL.

Moreover, its not as if computation itself has become more powerful, rather it has been given a larger, expansive platform to operate in. The logic of computation, the formalisation of algorithms, or, the ‘secret sauce’, (as Naughton whimsically puts it) have simply fulfilled their general purpose, which is to say they have become purposely generalised, in most, if not all corners of Western production. As Cory Doctorow put in 2011’s 28c3 and throughout last year, ‘We don’t have cars anymore, we have computers we ride in; we don’t have airplanes anymore, we have flying Solaris boxes with a big bucketful of SCADA controllers.’ Any impact on one corner of computational use affects another type of similar automation.

Algorithms in-themselves then, haven’t really changed, they have simply expanded their automation. Securing, compressing, trading, sharing, writing, exploiting. Even machine-learning, a name which infers myths of self-awareness and intelligence are only created to make lives easier through automation and function.

The fears surrounding their control are an expansion of this automated formalisation, not something remarkably different in kind. It was inevitable that in a capitalist system, effective procedures which produce revenue would be increasingly automated. So one should make the case that the controlling aspect of algorithmic behaviour be tracked within this expansion (which is not to say that computational procedures are inherently capitalist). To understand algorithmic control is to understand what the formal structure of algorithms are and how they are used to construct controlling environments. Before one can inspect how algorithms are changing daily life, and environmental space, it is helpful to understand what algorithms are, and on a formal level, how they both work and don’t work.

The controlling, effective and structuring ‘power’ of algorithms, are simply a product of two main elements intrinsic to formal structure of the algorithm itself as originally presupposed by mathematics: these two elements are Automation and Decision. If it is to be built for an effective purpose, (capitalist or otherwise) an algorithm must simultaneously do both.

For Automation purposes, the algorithm must be converted from a theoretical procedure into an equivalent automated mechanical ‘effective’ procedure (inadvertently this is an accurate description of the Church-Turing thesis, a conjecture which formulated the initial beginnings of computing in its mathematical definition).

Although it is sometimes passed over as obvious, algorithms are also designed for decisional purposes. Algorithms must also be programmed to ‘decide’ on a particular user input or decide on what is the best optimal result from a set of possible alternatives. The algorithm has to be programmed to decide on the difference between a query which is ‘profitable’ or ‘loss-making’, or a set of shares which are ‘secure’ or ‘insecure’, or deciding the optimal path amongst millions of variables and constraints, or locating various differences between ‘feed for common interest’ and ‘feed for corporate interest’. When any discussion arises on the predictive nature of algorithms, it operates on the suggestion that it can decide an answer or reach the end of its calculation.

Code both elements together consistently and you have an optimal algorithm which functions effectively automating the original decision as directed by the individual or company in question. This is what can be typically denoted as ‘control’ – determined action at a distance. But that doesn’t mean that an algorithm suddenly emerges with both elements from the start, they are not the same thing, although they are usually mistaken to be: negotiations must arise according to which elements are to be automated and which are to be decided.

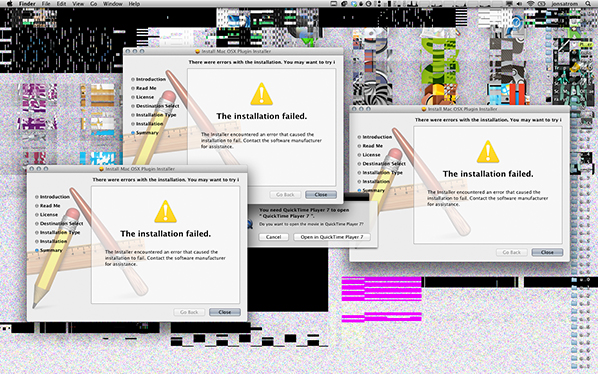

But code both elements or either element inconsistently and you have a buggy algorithm, no matter what controlling functionality it’s used for. If it is automated, but can’t ultimately decide on what is profit or loss, havoc ensues. If it can decide on optimised answers, but can’t be automated effectively, then its accuracy and speed is only as good as those controlling it, making the algorithm’s automation ineffective, unreliable, or only as good as human supervision.

“Algorithmic control” then, is a dual product of getting these two elements to work, and my suggestion here is any resistance to that control comes from separating the two, or at least understanding and exploiting the pragmatic difficulties of getting the two to work. So looking at both elements separately (and very quickly), there are two conflicting political issues going on and thus two opposing mixtures of control and non-control;

Firstly there is the privileging of automation in algorithmic control. This, as Slavin asserts, examines algorithms as unreadable “co-evolutionary forces” which one must understand alongside nature and man. The danger that faces us consists in blindly following the automated whims of algorithms no matter what they decide or calculate. Decision-making is limited to the speed of automation. This view is one of surrendering calculation and opting for speed and blindness. These algorithms operate as perverse capitalist effective procedures, supposedly generating revenue and exploiting users on their own well enough (and better than any human procedure), the role of their creators and co-informants is a role best suited to improving the algorithm’s conditions for automation or increasing the speed to calculate.

Relative to the autonomous “nature” of algorithms, humans are likely to leave them unchecked and unsupervised, and in turn they lead to damaging technical glitches which inevitably cause certain fallouts, such as the infamous “Flash Crash” loss and regain on May 6th 2010 (its worrying to note that two years on, hardly anyone knows exactly why this happened, precisely insofar no answer was decided). The control established in automation can flip into an unspeakable mode of being out of control, or being subject to the control of an automaton, the consequences of which can’t be fully anticipated until it ruins the algorithm’s ability to decide an answer. The environment is now subject to its efficiency and speed.

But there is also a contradictory political issue concerning the privileging of decidability in algorithmic control. This as Naughton and Katz suggest, is located in the closed elements of algorithmic decision and function. Algorithms built to specifically decide results which only favour and benefit the ruling elite who have built them for specific effective purposes. These algorithms not only shape the way content is structured, they also shape the access of online content itself, determining consumer understanding and its means of production.

This control occurs in the aforementioned Simplex Algorithm, the formal properties which decide nearly all commercial and business optimising; from how best to roster staff in supermarkets, to deciding how much finite machine resources can be used in server farms. Its control is global, yet it too faces a problem of control in that its automation is limited by its decision-making. Thanks to a mathematical conjecture originating with US mathematician Warren Hirsch, there is no developed method for finding a more effective algorithm, causing serious future consequences for maximising profit and minimising cost. In other words, the primary of decidability reaches a point where it’s automation is struggling to support the real world it has created. The algorithm is now subject to the working environment’s appetite for efficiency and speed.

This is the opposite of privileging automation – the environment isn’t reconstructed to speed up the algorithm automation-capabilities irrespective of answers, rather the algorithm’s limited decision-capabilities are subject to the environment which now desires solutions and increased answers. If the modern world cannot find an algorithm which decides more efficiently, modern life reaches a decisive limit. Automation becomes limited.

——————–

These are two contradictory types of control; once one is privileged, the other recedes from view. Code an algorithm to automate at speed, but risk automating undecidable, meaningless, gibberish output, or, code an algorithm to decide results completely, but risk the failure to be optimally autonomous. In both cases, the human dependency on either automation or decision crumbles leading to unintended disorder. The whole issue does not lead to any easy answers, instead it leads to a tense, antagonistic network of algorithmic actions struggling to fully automate or decide, never entirely obeying the power of control. Contrary to the usual understanding, algorithms aren’t monolithic, characterless beings of generic function, to which humans adapt and adopt, but complex, fractured systems to be negotiated and traversed.

In between these two political issues lies our current, putrid situation as far as the expansion of computation is concerned – a situation in which computational artists have more to say about it than perhaps they think they do. Their role is more than mere commentary, but a mode of traversal. Such an aesthetics has the ability to roam the effects of automation and decision, examining their actions even while they are, in turn, determined by them.

* With special thanks to the artist and writer Paul Brown, whom pointed out the longer history of the FFT to me.

MaKey MaKey is a kit that lets you turn anything into a controller. Let your imagination go wild!

Codasign in partnership with Furtherfield will be running two MaKey MaKey workshops for children and their parents at Furtherfield Gallery on Saturday 16 February: a morning session with 6-9 year olds (10-12pm) and an afternoon one with 9-12 year olds (1-4pm).

All supporting material for the workshop will be available at learning.codasign.com.

What will you do and learn?

During this workshop, the children will practice using computational thinking and interactive design through a variety of activities.

What do you need to already know?

You only need to have big ideas – no other experience required.

What do you need to bring?

You need to bring a laptop and an adult. The same adult can accompany multiple children. If you aren’t able to bring a laptop, just let us know by adding a note to your registration or e-mailing info@codasign.com.

What will be available during the workshop?

There will be drinks available, but you are welcome to bring along some snacks to feed your creativity.

Cancellation Policy

Full refund if registration is cancelled over a week before the course start, 50% if within a week of the course start, and no refund if within 24 hours of the course start.

VISITING INFO

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Scratch is a programming environment that is easy to use and created with children in mind. Create and share your own interactive stories, games, music and art!

Codasign in partnership with Furtherfield will be running two Scratch workshops for children and their parents at Furtherfield Gallery on Saturday 09 February: a morning session with 6-9 year olds (10-12pm) and an afternoon one with 9-12 year olds (1-4pm).

Please book your place.

All supporting material for the workshop will be available at learning.codasign.com.

What will you do and learn?

You will design and make a game or animation using the Scratch environment.

What do you need to already know?

You only need to have big ideas – no other experience required.

What do you need to bring?

You need to bring a laptop and an adult. The same adult can accompany multiple children. If you aren’t able to bring a laptop, just let us know by adding a note to your registration or e-mailing info@codasign.com.

What will be available during the workshop?

There will be drinks available, but you are welcome to bring along some snacks to feed your creativity.

Cancellation Policy

Full refund if registration is cancelled over a week before the course start, 50% if within a week of the course start, and no refund if within 24 hours of the course start.

VISITING INFO

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

We live in a world riddled with contradictions and confusing signals. Our histories are assessed, judged and introduced as fact yet there are so many bits missing. We accept what is given through soundbite forms of mediation and end up using the easy bits as our defaults, and build up these assumptions as our ‘imagined’ guidelines. This article examines how these accepted defaults are being challenged by contemporary artists. Each have expressed their own particular (unofficial and official) form of interventions at the Tate Gallery. Featuring art works produced by artists’ and art groups, such as Graham Harwood, Platform, IOCOSE and Tamiko Thiel, we explore their connected enactments and critiques of the existing conditions. Whether it is based on economic, ecological, historical, political or hierarchical situations, they are making others aware of their creative arguments in different ways.

You will not see them accepting an award at the Turner Prize. But, their work has become as equally significant (perhaps even more) than, the mainstream art establishment’s franchised celebrities. There is now wider art audience out there, connected to the Internet and they are aware of the issues of the day. Yet, this context is not reflected back by traditional art venues and art press. Instead, we receive more of the same. The mainstream version of contemporary art has found its allies within a global and corporate culture, where business dictate’s art value. Critical and imaginative contexts contrary to neoliberal demands, are left aside. We cannot trust the ‘official’ art world to produce a realistic vision of what contemporary art really is. It is up those who are not reliant on or diverted by these powerful frameworks and elusive economies, to bring about a different set of examples of an existing parallel world which is thriving, and so much more interesting and relevant.

“Art is subject to a double protection. In the market, it is shielded from unwarranted treatment through controlled ownership. In the museum world, experts decide what should be seen, alongside what, with what interpretation and in what circumstances. A wide public is courted but allowed no power over what it sees. The very ethos of this culture—of exclusivity, elitism and control—is now at odds with the culture people make themselves.” [1] (Stallabrass 2011)

“From adolescence I had visited the Tate, read the Art books and generally pulled a forelock in the direction of the cult of genius, on cue relegating my own creativity to the Victorian image of the rabid dog. We know well enough that this was how it was supposed to be. The historical literature on ‘rational recreations’ states that, in reforming opinion, museums were envisaged as a means of exposing the working classes to the improving mental influence of middle class culture. I was being inoculated for the cultural health of the nation.”[2] (Harwood)

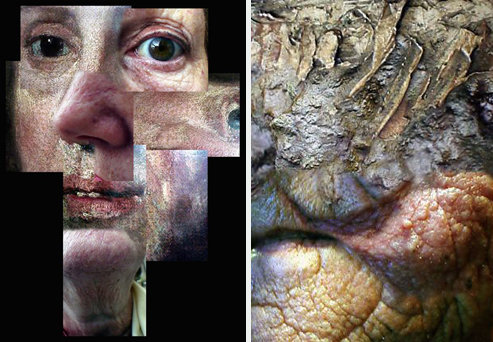

In 2000, Graham Harwood[3] received the first Net Art online commission from the Tate Gallery London for the creation of his art work ‘Uncomfortable Proximity'[4]. Viewing the visual images/collages created by Harwood; reminds one of the moment when Dorian Gray in Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray'[5] views his disfigured self portrait. Considered a work of classic gothic fiction with a strong Faustian theme. The facade of his own idealised beauty is revealed as something less attractive and deeply disturbing. Harwood’s approach in offering the viewer to click on the image to see what lies behind shows the people he represents, to be seen as lurking secrets, as ghosts, mutants, lepers and outsiders.

![Dorian in front of his portrait in the 1945 film The Picture of Dorian Gray.[6]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/dorian-gray.jpg)

“Tate Britain stands on the site of Millbank penitentiary incorporating part of the prison within its own structure. The bodies of many of the inmates remain concreted into the foundations of the building. The drains that run from the building to the Thames, a stones through away, bleed this decay into the silt of the Thames.”[7] (Harwood 2006).

Harwood brings to the fore the forgotten people. The lives of others, whose stories are now just distant markers of a past, dominated by a colonial history. These are the losers, the then ridiculed and exploited chavs of their day.

“‘Chav’ is an insulting word exclusively directed at people who are working class.”[8] (Jones 2012).

The first section of ‘Uncomfortable Proximity’ maps high society rituals of tastefulness and its inherent hypocrisy. The second, representations and histories of different people such as friends, family and others, who are unseen in terms of the institution’s remit of tastefulness. To do this he used the historically respected paintings (on-line images) on the Tate web site by artists such as Turner, Hogarth, Hamilton, Gainsborough, Constable and others.

“This work forced me into an uncomfortable proximity with the economic and social elite’s use of aesthetics in their ascendancy to power and what this means in my own work on the internet.”[9] (Harwood 2006)