DoggieWoggiez! PoochieWoochiez! is a new video work (2012) by Everything is Terrible!, a self-described “found footage chop shoppe”. DoggieWoggiez! PoochieWoochiez! is an active catalog which describes, invents and destroys concepts as it arranges video footage into flows of multiple cuts that map the use of dogs in cinema and television. The structure of this review takes hints from the work it overlays. We dispensed with “original” writing and didactic detailing of what we as critics experienced. Instead, we unraveled multiple threads left hanging after watching DoggieWoggiez! PoochieWoochiez! We neglected to offer an appraisal of the worth of the work, and add to the number of words already in the world. Instead, we traced the flows passing through the video and developed a program of citations that provide a map of exit and entrance points-a map, as any map, that is as much about those making as about the territory described-which we hope will provide openings for a reader who has not yet watched the work, and provide expanded intersections for those who already have.

“This is the scenario: You are terminally ill, all medical treatments acceptable to you have been exhausted, and the suffering in its different forms is unbearable. Because the illness is serious, you recognize that your life is drawing to a close. Euthanasia comes to mind as a way of release.” [note]Humphry, Derek. Final Exit. New York: Delta Trade Paperback, 2001. 1.[/note]

“Success consists of simply getting up one more time than you fall.” [note]Jerry Maguire. Dir. Cameron Crowe. Gracie Films and TriStar Pictures. 1996. Sign on the locker room wall.[/note]

“From whatever angle you approach it, the present offers no way out. This is not the least of its virtues. From those who seek hope above all, it tears away every firm ground. Those who claim to have solutions are contradicted almost immediately. Everyone agrees that things can only get worse. ” [note]The Invisible Committee. The Coming Insurrection. Cambridge, MA: Semiotext(e) Intervention Series, 2009. 23.[/note]

“A positive anything is better than a negative nothing.” [note]Jerry Maguire. Sign on the locker room wall.[/note]

“I think it’s because dog movies and dog footage tends to be the dumbest. It’s like the lowest common denominator amongst everything we’ve found, the most mediocre footage imaginable. I think that was a big motivator, and we just like dogs. It’s a nicer way to deliver horrible things about humanity. Instead of watching people be racist, which makes you feel terrible, you get to watch dogs be racist, and you’re like, ‘That’s a little better.'” [note]Gilgamesh, Commodore. Interview by Ben Munson. “Everything Is Terrible!’s Commodore Gilgamesh”. The A.V. Club, 2012. Web, Jan. 2012. http://www.avclub.com/madison/articles/everything-is-terribles-commodore-gilgamesh,68313/[/note]

“Americans spent $50.96 billion on their pets in 2011. That’s an all-time high, and for the first time in history more than $50 billion has gone to dogs, cats, canaries, guppies and the like, the American Pet Products Association reports. Food and vet costs accounted for about 65 percent of the spending. But it was a service category one that includes grooming, boarding, pet hotels, pet-sitting and day care that grew more than any other, surging 7.9 percent from $3.51 billion in 2010 to $3.79 billion in 2011.” [note]T&D Staff. “Pet ownership responsibility has not changed.” The Times and Democrat. Web. March 10, 2012. http://thetandd.com/news/opinion/pet-ownership-responsibility-has-not-changed/article_c3fd2738-6a73-11e1-a700-001871e3ce6c.html[/note]

“So we have a corpse on our backs, but we won’t be able to rid ourselves of it just like that. Nothing is to be expected from the end of civilization, from its clinical death. In and of itself, it can only be of interest to historians. It’s a fact, and it must be translated into a decision. Facts can be conjured away, but decision is political. To decide on the death of civilization, then to work out how it will happen: only decision will rid us of the corpse.” [note]The Invisible Committee. 94.[/note]

2:39 . Black and white footage of a clothed dog sleeping in hay.

2:41 . Saint Bernard laying on the floor trying to drink champagne out of a bottle.

2:42 . Black and white footage of a dog holding a bottle labeled “Hard Cider” in his mouth and drinking.

2:43 . Dog with bandana sitting at table licking the foam from a beer.

A hand pouring beer into a dish filled with dog food.

2:44 . A club. Multiple young women filling the face of a puppet dog full of liquor bottles.

2:45 . A dog wearing a jersey with the number one peeing on a referee’s ankle.

2:47 . A dog lifting its leg on a pants suit leg.

A bulldog in a spiked collar peeing on a floor mat that says “I [heart] Acting.”

2:48 . A dog peeing on a metal catwalk, shot from below.

2:49 . Jack Nicholson holds a small dog up and away from his chest as the dog pees.

A man lying on a floor is shot below and through a dogs legs, the dog’s urine stream is hitting him in the face.

2:51 . A similar shot, reversed. Another man, wearing a fur hat, is buried to his neck in sand and ice. A dog urinates into his mouth.

2:51 . The same bulldog in spiked collar lifts his leg to pee. A small rocket comes out of from beneath him.

2:52 . A similar shot from the other side, a different dog is urinating flames.

“I am for an art that embroils itself with the everyday crap & still comes out on top.” [note]Oldenburg, Claes. “I Am for an Art…,” Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings. eds. Stiles, Kristine and Selz, Peter. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. 335.[/note]

“Trash collection is the business of public sanitation; its recycling, the very height of capitalist alchemy, turns everything into grist for commodification’s mill. But it is also a strategy of aesthetic sublimation that, according to Thomas Crow, is internal to modernism (he has analyzed the cyclical aspect of this in terms of the incorporation of the ‘low’ by the ‘high’)” [note]Bois, Yve-Alain and Krauss, Rosalind. “A User’s Guide to Entropy.” October. 78.Autumn 1996. 47.[/note]

“Classification in the widest sense is, along with astronomy, probably one of the oldest scientific pursuits undertaken by man. In the most general terms classification is the process of giving names to a collection of objects which are thought to be similar to each other in some respect. The ability to sort similar things into categories is obviously a primitive one, since it would seem to be a prerequisite of the development of language, which consists of words which help us to recognize and discuss the diSerent types of events, objects and people we encounter; each noun in a language is a label used to describe a class of things which have striking features in common. Thus for example, we name animals as cats, dogs, or horses and such a name collects individuals into groups.” [note]Everitt, B.S.. “Unresolved Problems in Cluster Analysis.” Biometrics. 35.1. 169.[/note]

“I am for an art that imitates the human, that is comic, if necessary, or violent, or whatever is.” [note]Oldenburg, Claes. 335.[/note]

“What is it that moves over the body of a society? It is always flows, and a person is always a cutting off [coupure] of a flow. A person is always a point of departure for the production of a flow, a point of destination for the reception of a flow, a flow of any kind; or, better yet, an interception of many flows.” [note]Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 1987. 28.[/note]

“I am for the art of things lost or thrown away, coming home from school.” [note]Oldenburg, Claes. 335.[/note]

“Cluster analysis, also called data segmentation, has a variety of goals. All relate to grouping or segmenting a collection of objects into subsets or “clusters,” such that those within each cluster are more closely related to one another than objects assigned to different clusters. An object can be described by a set of measurements, or by its relation to other objects.” [note]Friedman, Jerome; Tibshirani, Robert and Hastie, Trevor. The Elements of Statistical Learning. 2nd ed. published online: Springer, February 2009. http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~tibs/ElemStatLearn/ 501.[/note]

“And now, we have to start from scratch with this movie and go through thousands of VHS tapes and find those three minutes and put them in a pile until we have enough to make an hour-long movie. And yeah, it made it harder because we just fucking hate those movies.” [note]Gilgamesh, Commodore.[/note]

“Central to all of the goals of cluster analysis is the notion of the degree of similarity (or dissimilarity) between the individual objects being clustered. A clustering method attempts to group the objects based on the definition of similarity supplied to it.” [note]Friedman, Jerome; Tibshirani, Robert and Hastie, Trevor. 502.[/note]

“[Claes Oldenburg] quickly saw that it didn’t take anything to make a Ray Gun: any right angle would suffice, even blunted, even barely perceptible. The Ray Gun is the ‘universal angle’: ‘Examples: Legs, Sevens, Pistols, Arms, Phalli-simple Ray Guns. Double Ray Guns: Cross, Airplanes. Absurd Ray Guns: Ice Cream Sodas. Complex Ray Guns: Chairs, Beds. Mondrian didn’t need to reduce everything to the right angle: everything is already a right angle. During the time of The Store, Oldenburg made huge numbers of Ray Guns (in plaster, in papier mache, in all kinds of materials in fact), but he soon saw that he didn’t even need to make them: the world is full of Ray Guns. All one has to do is stoop to gather them from the sidewalks (the Ray Gun is an essentially urban piece of trash: Oldenburg produced their anagram as Nug Yar:New York). Even better: he didn’t even need to collect them himself; he could ask his friends to bring them to him (he limited himself to accepting or refusing the find’s addition into the corpus, according to purely subjective criteria). Finally, there are all the Ray Guns one can’t move- splotches on the ground, holes in the wall, torn posters-but which one could photograph. The “inventory”is potentially infinite. And what should be done with this invasive tide? Put it in the museum.” [note]Bois, Yve-Alain and Krauss, Rosalind. 49-50.[/note]

“I am for the art out of a doggy’s mouth, falling five stories from the roof.” [note]Oldenburg, Claes. 355.[/note]

2:54 . A dog and man lay side-by-side. The dog’s legs are up and its belly is exposed to the camera. Voiceover: “Being a thief isn’t bad enough, you have to be a lush too.”

2:56 . A golden retriever puppy faces the camera with a drunken expression. The dogs lips move as he says “That’s the weirdestest grape juice ever.” He laughs.

3:02 . A dog jumps off a large desert rock onto another rock. He yells “Hasta la vista, kitty.” A mountain lion is shown launching into the air.

3:05 . Maniacal laughter is played over footage of a tree frog sitting on the top of a dog’s head.

3:06 . A Weimaraner sleeps under a blanket. Voiceover: “Do dogs dream? She dreams she’s a dear”

A ripple dissolve into the same dog with her head stuck through a tapestry of deer so that it appears that there is a deer with a dog head.

“Are there Oedipal animals with which one can ‘play Oedipus,’ play family, my little dog, my little cat, and then other animals by contrast draw us into an irresistible becoming? Or another hypothesis : Can the same animal taken up by two opposing functions and movements, depending on the case?” [note]Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. 233.[/note]

“Writing about the dog who befriended him and his fellow-inmates in a concentration camp, and whom they named Bobby, Levinas says that this dog was ‘the last Kantian in Nazi Germany,’ because his joyful greetings reminded the prisoners of their human dignity. Yet, when questioned closely about the ethical status of nonhuman animals, Levinas is reluctant to ascribe to animals that ‘ethical face’ which he elsewhere has called (as Martin calls Sylvia’s face) ‘an epiphany.’ By contrast, says Levinas, the animal face is merely ‘biological,’ incapable of demanding the ethical response. Levinas denies that the dog can have a face in the ethical sense: ‘the phenomenon of the face is not in its purest form in the dog,’ he writes. ‘I cannot say at what moment you have the right to be called ‘face.’ The human face is completely different and only afterwards do we discover the face of the animal.’ In an article subtitled ‘Levinas Faces the Animal,’ Peter Steeves, with gentle irony, stages another face-to-face encounter between Levinas and Bobby, asking the philosopher: ‘What could Bobby be missing? Is his snout too pointy to constitute a face? Is his nose too wet? Do his ears hang low, do they wobble to and fro? How can this not be a face?'” [note]Chaudhuri, Una. “(De)Facing the Animals Zooësis and Performance.” TDR: The Drama Review. 51.1. 16.[/note]

“We’ve always had a thing with how people treat little people at Everything Is Terrible!, like it’s really weird and creepy. Anybody who’s like a second-class being, when they’re used in videos, it comes across very creepy and gross. I think it’s the same thing with humans and dogs. They’re weirdly sexualized, they’re weirdly turned into little kids at the same time.” [note]Gilgamesh, Commodore.[/note]

“…individuated animals, family pets, sentimental, Oedipal animals each with its own petty history, ‘my’ cat, ‘my’ dog. These animals invite us to regress, draw us into a narcissistic contemplation, and they are the only kind of animal psychoanalysis understands, the better to discover a daddy, a mommy, a little brother behind them (when psychoanalysis talks about animals, animals learn to laugh): anyone who likes cats or dogs is a fool.” [note]Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. 240.[/note]

“I think that’s a big reason why people use dogs the way they do, because I think we kind of hate ourselves so we dress up dogs like ourselves to mock ourselves. So you dress a dog up like a drunk human, and then you laugh at how ridiculous it is, but I think it’s therapeutic. We’re letting off steam about how much we hate ourselves.” [note]Gilgamesh, Commodore.[/note]

3:13 . A close-up of a shaggy dog who speaks. “It’s not a dream”.

3:16 . A large dog outside a car tells a small dog inside a car, “Bitches ain’t got no business being inside your head” The voice is or is similar to Samuel Jackson’s.

3:17 . A bloodhound with an ice pack on its head also has cartoon dream bubbles floating around it. The woman inside the bubbles says, brightly “Wake up!”

Another dog, turning his head to the camera, says “Who are those jokers?”

Return to the bloodhound, the floating woman says “It’s me, Jan.”

3:20 . A dog dressed as a pauper is grabbed from above and dragged to the side.

A dog wearing a bandana says “Great danes! This is terrible. But what can I do…”

This trails into a golden retriever saying “…I’m a dog.”

“What difference does it make if someone is terminal? We are all terminal.” [note]Gupta, Sanjay. “Kevorkian: ‘I have no regrets'” CNN Health. June 14, 2010. http://articles.cnn.com/2010-06-14/health/kevorkian.gupta_1_kevorkian-dr-jack-euthanasia-assisted-suicide?_s=PM:HEALTH[/note]

layla commented: 4-21-2008 9:01 PM “In 2007 Guillermo Vargas Habacuc a so called artist took an abandoned dog from the streets tied him to a very short rope to a wall in an art gallery and left a kettle of food on the other side of the room beyond his reach and left him there to slowly die of hunger and thirst. The socalled artist of such cruelty and the visitors of the gallery of art watched the agony of this animal. The dog finally died of famine surely after a painful absurd and incomprehensible torture. The prestigious Centralamerican Biennial of Art decided that this horrible act committed by this guy was art and Guillermo Vargas Habacuc has been invited to repeat his cruel actions in said Biennial in 2008. i seen this post on facebook and a few pictures of the poor innocent dog starving to death it broke my heart and i had to see if peta was aware of this sick man who thinks this i some great at creation.” [note]layla. comment. “Artist Starving Dog?” The Peta Files. April 21, 2008. Date of access: March 28, 2012. http://www.peta.org/b/thepetafiles/archive/2008/04/21/artist-starving-dog.aspx[/note]

olivia commented: 5-10-2008 5:35 PM “i hate you. you should be put in the poor dog’s possision. you can’t imagine how many people hate you. almost more than a million. just so you know thats not art. the dog died because of you. you should go to prison because of this. you broke peoples’ hearts. i am really upset at you i could write all day long if i have to because you just waisted a life i wish i could waiste youres!!!!!! do you wish all the animals should die? you just made my day so so so horrible. im going to tell everyone what you just did. just so you know i’m cring. i hate hate hate hate you. you should be ashamed of your self. so listen to this just because you think your all that doesn’t mean that you can kill an other animal. i have 7 animals and you are not going to touch them! that dog did nothing to you. if heshe did doesn’t mean you should kill him! please don’t touch any other animal!!!!!! you suck!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! P.s i hate youuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu” [note]olivia. comment. ibid.[/note]

Renate commented: 5-5-2008 1:34 PM “Here’s a thought let’s tie up Guillermo Vargas at one of his own exhibits and starve him to death!” [note]Renate. comment. ibid.[/note]

Rainie M commented: 4-28-2008 2:59 PM “Oh Gods! How can anyone be so bloody heartless? Dead or dying animals are NOT art…things like this only come from sick minds. Is the human race devolving so much that we have come down to this as entertainment? If you want Art go to a Museum . Geez this is just sick…” [note]Rainie. comment. ibid.[/note]

Tucker commented: 4-26-2008 10:43 AM “THIS IS DOWN RIGHT UNCALLED FOR DIGUSTINGCRUEL AND THESE PEOPLE NEED TO BE LOCKED UP AND CHARGED BIG TIME!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! I AM CRYING SO HARD RIGHT NOW IT IS UNBELIEVABLE WHAT $IN PEOPLE DO TO ANIMALS AND THIS ALL NEEDS TO STOP NOW AND BIG TIME CHARGES AND JAIL TIME NEED TO BE STRONGER AND LONGER IN ALL STATES AND AROUND THE WORLD!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! SAVE THE ANIMALS!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!” [note]Tucker. comment. ibid.[/note]

Angie commented: 4-24-2008 12:55 PM “I am so sickend by this whole so called art.. I am a artist myself. ! And i think someone need to tie this guy up and not feed him any food and have people watch him starve . Then he will realize how it feels. He gives a bad name to other artist out there!” [note]Angie. comment. ibid.[/note]

yf commented: 4-22-2008 2:32 PM “you know he really shoudl have starved himself and then do a ‘selfportrait’.. much more apt.. silly stupid man.. so pointless.. so banal.. people KNOW what skeletal skin and bones animals look like .. we have seen them.. we know what skeletal starved humans look like too infact.. we dont’ need a dumb dimwit 12 brained idiot to INTENIONALLY starve a dog in ORDER to produce his pointless ‘artwork’.. what a dumb stupid peabrained twit !” [note]yf. comment. ibid[/note]

Kristin Gleeson commented: 4-22-2008 1:29 AM “Yeah I’ve seen something like this before but what was it? Oh yeah the HOLOCAUST. Thousands of people collected subdued and starved to death. Was that an artistic masterpiece? If you call this art you’d have to call Hitler an artist I mean after all he was trying to make a culturally altering statement as well. It’s not art it’s sadistic immoral and completely disgusting. This poor creature did not deserve this and neither does any other animal on the planet.” [note]Gleeson, Kristin. comment. ibid.[/note]

“Do not imitate a dog, but make your organism enter into composition with something else in such a way that the particles emitted from the aggregate thus composed will be a canine as a function of the relation of movement and rest, or of molecular proximity, into which they enter.” [note]Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. 247.[/note]

“Its efficiency is striking. There is nothing extra, superfluous or obscure about Mr. Kulik’s performance. For all intents and purposes, he is a dog: he can be scary and unpredictable and territorial. After all, he’s in his prime, about 5 dog years old; visitors who wish to enter his cage may do so one at a time and must put on the quilted overalls and arm-guards that hang near the chained and barred door to his cage.” [note]Smith, Roberta. “On Becoming a Dog By Acting Like One.” New York Times. April 18, 1997. http://www.nytimes.com/1997/04/18/arts/on-becoming-a-dog-by-acting-like-one.html[/note]

“The choice of the term ‘pack’ for this older and more limited kind of crowd is intended to remind us that it owes its origin among men to the example of animals, the pack of animals hunting together. Wolves, which man knew well and from whom many of the dogs he uses derive, had impressed him very early. Their occurrence as mythical animals among so many peoples, the conception of the were-wolf, the stories of men who, disguised as wolves, assailed and dismembered other men, the legend of children brought up as wolvesall these things and many others prove how close the wolf was to man.” [note]Canetti, Elias. Crowds and Power. New York: Viking Press, 1966. 96.[/note]

“Saying it would be too confusing, a judge has denied the petition of a so-called ‘furry’ to legally change his name to Boomer the Dog. Forty-four-year-old Green Tree resident Gary Guy Mathews says he filed for the name change in June because he’s a fan of a short-lived 1980s NBC television series called “Here’s Boomer,” which featured a dog that rescued people.” [note]Today Staff and wire. “Judge won’t let man call himself ‘Boomer the Dog’.” Today News. August 12, 2010. http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/38673766[/note]

Where’s Waldo, #1.5 – Sun Aug 15, 2010 10:31 PM EDT “This boy ain’t wired right. I’ve heard of men wanting to be a women and women wanting to be men but this is a new one on me. Mom and Dad must have raised the poor kid in a kennel instead of a crib. Wonder what his favorite pup food was? Of course maybe he’s smarter than any of us thinks……or maybe not.” [note]Where’s Waldo. comment. ibid.[/note]

dave-735909, Thu Aug 12, 2010 10:21 AM EDT “Why can’t we just respect people’s constitutional right to be crazy?” [note]dave-735909. comment. ibid.[/note]

Susi-Oh, Thu Aug 12, 2010 12:10 PM EDT “My sentiments exactly but how far do you want to take this? Should we just let him bark back when you ask him a question? Can you introduce a guy like that with a straight face? He’s big for a dog and might scare little children. Actually, even without the name change he looks a bit scary.” [note]Susi-Oh. comment. ibid.[/note]

Janet A., #15 – Thu Aug 12, 2010 10:59 AM EDT “If this idiot was truly a dog, we’d put him to sleep for being insane. Just a thought.” [note]A., Janet. comment. ibid[/note]

wchall1949, #2 – Thu Aug 12, 2010 10:15 AM EDT “OMG – the really frightening thing here is that this guy is allowed to marry & reproduce!!! Truly scary!! What a moron!!!” [note]wchall1949. comment. ibid.[/note]

Sues-343312, #2.1 – Thu Aug 12, 2010 11:22 AM EDT “Well he is 44 yrs old has managed to not procreate up to now. Let’s just hope he meets up with a spayed female” [note]Sues-343312. comment. ibid.[/note]

3:26 . A close-up of a crying child, with a dissolve of snow over his face. He says “Daddy…”

Close up of an adult man, he says “I don’t have a daddy.”

A girl wears a party hat. Lying on her bed, she talks to her brother, also wearing a party hat. She says “I just miss him so much…”

Cut to a different girl in pigtails addressing a bloodhound wearing a king’s crown and fur cape. She says “I miss him too.”

3:30 . Close-up of a crying boy. “I miss him, mom.”

Angry-looking farmer standing under a tree. He says “Your mother passed on.”

3:32 . A woman lays on a bed with a girl. “…to join the angels.”

A man looks up to the sky and gestures upwards “She’s in heaven.”

A woman with a party hat “watching over you right now.”

3:37 . A boy addresses a dog. “My dad used to do that.”

A boy and his mother talk as she drives. The boy says “He wants a dad.”

A woman sits next to a boy outside with a rocky hill behind them. He is looking through binoculars. She says “You remind me a lot of your dad sitting there.”

“When they’re your best friend it turns into this weird, gross, furry pile where you can’t tell where the lines are between human and dog, master and slave, and sex, and it’s just ugh.” [note]Gilgamesh, Commodore.[/note]

“Bestiality lowered a man to the level of a beast, but it also left something human in the animal.” [note]Murrin, John M. “‘Things Fearful to Name’: Bestiality in Colonial America.” Pennsylvania History. 65.Explorations in Early American Culture. 1998. 10.[/note]

“A man has appeared before Limerick District Court charged with ordering his Alsatian dog to have sex with a 43-year-old mother of four, who died from an adverse allergic reaction to the intercourse.” [note]Staff. “Woman died from allergic reaction to sex with dog” thejournal.ie. Web. Mar 7, 2011. http://www.thejournal.ie/woman-died-from-allergic-reaction-to-sex-with-dog-172620-Jul2011/[/note]

“Addressing the consent issue, Daniels writes, ‘[T]he truth is that animals, particularly domesticated ones, don’t consent to most of the things that happen to them.’ Animal sexual autonomy is regularly violated for human financial gain through procedures such as AI. Such procedures are probably more disturbing physically and psychologically than an act of zoophilia would be, yet the issue of consent on the part of the animal is never raised in the discussion of such procedures. Should the day Bentham speaks of arrive when animal rights are recognized by society and the law, an argument which speaks only to the zoophile’s right to fair exercise of his property rights in the animals he owns may prove an insufficient legal justification for acts of zoophilia.” [note]Cutteridge, Brian Anthony. “For the Love of Dog: On the Legal Prohibition of Zoophilia in Canada and the United States.” Sex, Drugs and Rock & Roll: Psychological, Legal and Cultural Examinations of Sex and Sexuality. eds. Gavin, Helen & Bent, Jacquelyn. Oxford, UKL Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2010.[/note]

“In 1812 in a similar case in strongly Federalist Seneca County, New York,William Moulton, a fifty-eight-year-old veteran of the Revolutionary War and a prominent Democratic-Republican, was accused of buggering a bitch, which then delivered a litter of puppies that ‘had large heads, no hair on them nor tails, and on the side of their head they had small ears.'” [note]Murrin, John M. 35.[/note]

“I am for the majestic art of dog-turds, rising like cathedral.” [note]Oldenburg, Claes. 335.[/note]

“The right of sovereignty was the right to take life or let live. And then this new right is established: the right to make live and to let die.” [note]Foucault, Michel. “Society Must Be Defended” Lectures at the Collège De France 1975 – 1975. New York: Picador, 2003. 241.[/note]

“Though a single gull had already struck Melanie on the forehead the day before, the choice of the children’s party for this first fully choreographed attack suggests the extent to which the birds take aim at the social structures of meaning that observances like the birthday party serve to secure and enact: take aim, that is, not only at children and the sacralization of childhood, but also at the very organization of meaning around structures of subjectivity that celebrate, along with the day of one’s birth, the ideology of reproductive necessity.” [note]Edelman, Lee. No Future. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004. 121.[/note]

“Death is outside the power relationship. Death is beyond the reach of power, and power has a grip on it only in general, overall or statistical terms…death now becomes, in contrast, the moment when the individual escapes all power, falls back on himself and retreats, so to speak, into his own privacy. Power no longer recognizes death. Power literally ignores death.” [note]Foucault, Michel. 248.[/note]

“Physician assisted suicide is fundamentally inconsistent with the physician’s professional role.” [note]Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, American Medical Association. “Physician-Assisted Suicide.” CEJA Report. 8 – I-93. Web. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/ethics/ceja_8i93.pdf[/note]

“Even worse their comments continue to make no distinction between hierarchical and non-hierarchical organizations and institutions — simply rejecting all organization — which is tantamount, if you think about it for a minute, to proposing a future that lacks workplaces, religious centers, families, any kind of assemblies, and so on — a future in which lone individuals or small groups fend for themselves (a vision seemingly not too far from what they propose).” [note]Spannos, Chris. “The Coming Insurrection or the Arrival of Suicidal Nonsense?” ZNet. July 23, 2009. Web. Date of access: March 28, 2012. http://www.zcommunications.org/the-coming-insurrection-or-the-arrival-of-suicidal-nonsense-by-chris-spannos[/note]

‘It is critical that the medical profession redoubles its efforts to ensure that dying patients are provided optimal treatment for their pain and other discomfort. The use of more aggressive comfort care measures, including greater reliance on hospice care, can alleviate the physical and emotional suffering that dying patients experience. Evaluation and treatment by a health professional with expertise in the psychiatric aspects of terminal illness can often alleviate the suffering that leads a patient to desire assisted suicide.” [note]Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, American Medical Association.[/note]

“Their vision of a commune offers very little guarantee of its own basic existence. There are no proposed methods for deciding what will be produced or consumed nor how much of each or its distribution in a socially responsible way.” [note]Spannos, Chris.[/note]

“The euthanasia of animals has been acknowledged by most animal protection organizations, including [The Humane Society of the United States], as an appropriate and humane means of ending the suffering of an animal in physical distress. It is also used widely to end the lives of animals who have severe behavioral problems, including aggression, and cannot be adopted into an appropriate new home because they pose a threat to the health and safety of people or other animals.” [note]The Humane Society of the United States. “Statement on Euthanasia.” Humane Society of the United States Website. July 15, 2009. Date of access: March 28, 2012. http://www.humanesociety.org/about/policy_statements/statement_euthanasia.html[/note]

“Once we know where it is we want to go, we can then act with the urgency needed to organize and build institutions and movements able to win change and create the necessary foundations for a future society.” [note]Spannos, Chris.[/note]

“Those who demand another society should better start to realize that there is none left. And maybe they would then stop being wannabe-managers.” [note]The Invisible Committee. 86.[/note]

“This is the dog’s real trick, the height of animal acting. Not surprisingly, the imitated action is one of violence and must have been somewhat complicated; because all pet dogs, and dog performers most of all, must be nonviolent and cooperative, the animal actor here must go against its ‘nature’ in order to successfully set up the final tableau. That animals can be domesticatedmade to forego violence in order to serve peopleis the triumph of human culture over nature. That they can then be trained to appear violentto attack humansis the ironic confirmation of this subjection.” [note]Peterson, Michael. “The Animal Apparatus From a Theory of Animal Acting to an Ethics of Animal Acts” TDR: The Drama Review. 51.1 Spring 2007. 37.[/note]

“Should you battle on, take the pain, endure the indignity, and await the inevitable end, which may be days, weeks or months away? Or should you take control of the situation and resort to some form of euthanasia, which in its modern-language definition has come to mean ‘help with a good death’?” [note]Humphry, Derek. 1.[/note]

“At the final stage of this evolution, we see the first socialist mayor of Paris putting the finishing touches on urban pacification with a new police protocol for a poor neighborhood, announced with the following carefully chosen words: ‘We’re building a civilized space here.’ There’s nothing more to say, everything has to be destroyed.” [note]The Imaginary Party. “How to?” Tiqquin Website. Date of access: Mar 28, 2012. http://www.clairefontaine.ws/tiqqun/how.pdf 8[/note]

3:43 A montage of eerily smiling children’s’ faces. Audio is the word “dad” played over and over as it overlaps and becomes “dog”. The words dad and dog are repeated in a loop. The video becomes a distorted montage of psychedelic faces of children and dogs. Eventually the words dad and dog becomes god.

4:03 The montage audio and video end abruptly.

A small dog says “I know something we can do.”

A shot of a Bernese, who says “Poop” then winks.

DoggieWoggiez! PoochieWoochiez! $20

http://www.everythingisterrible.bigcartel.com/product/doggiewoggiez-poochiewoochiez

http://www.everythingisterrible.com/

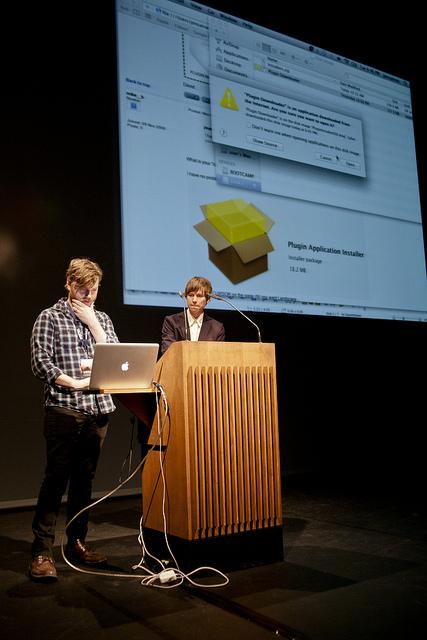

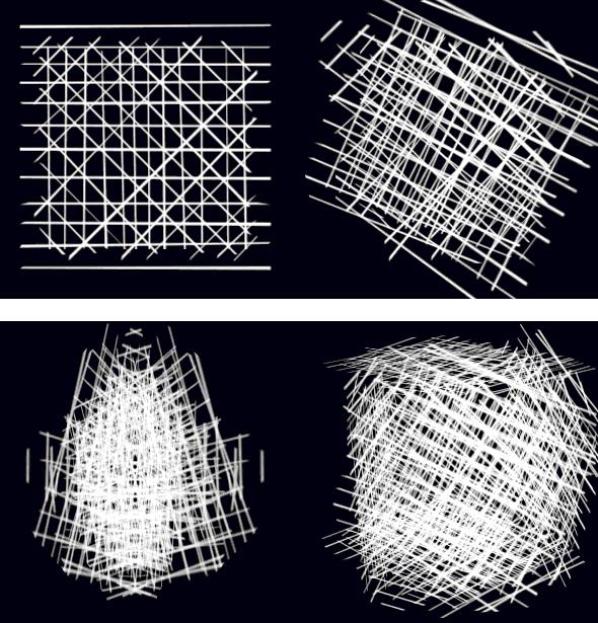

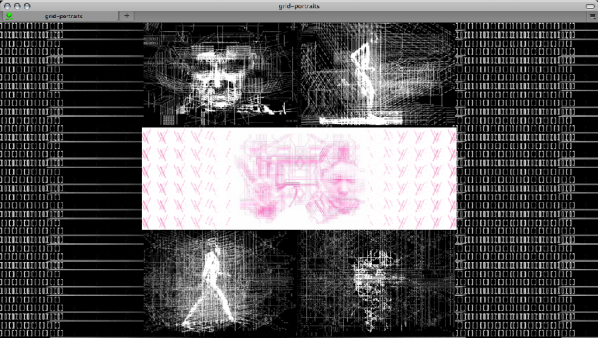

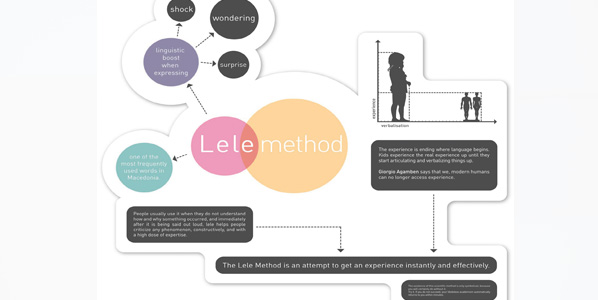

How can designers and programmers work more harmoniously? How can the tools being created better meet the needs of users? There is a need for designers to have a greater role in the production of the tools that they use, aside from just reporting bugs, requesting features or designing logos for open source projects. This is where the Libre Graphics Research Unit comes in. The Libre Graphics Research Unit (LGRU) is a traveling lab where new ideas for creative tools are developed. The unit has grand aims, looking to bring aspects of open source software development to artistic practices. The programme, sponsored by many organisations in Europe, is split into four interconnected threads:

The first meeting, Networked Graphics, took place in Rotterdam from 7-10 December, 2011 and was Hosted by WORM. This second meeting, Co-Position, for which I was present, took place at venues across Brussels from 22-25 February 2012. Co-Position is described by LGRU as:

[…] an attempt to re-imagine lay-out from scratch. We will analyse the history of lay-out (from moveable type to compositing engines) in order to better understand how relations between workflow, material and media have been coded into our tools. We will look at emerging software for doing lay-out differently, but most importantly we want to sketch ideas for tools that combine elements of canvas editing, dynamic lay-out, networked lay-out, web-to-print and Print on Demand.

The meeting saw the coming together of many international artists, theorists and developers for four days of work around this subject. As some of the sessions of the meeting took place simultaneously I’m unable to give a full synopsis of the event. Instead, what is presented below are some of the key issues raised at the meeting.

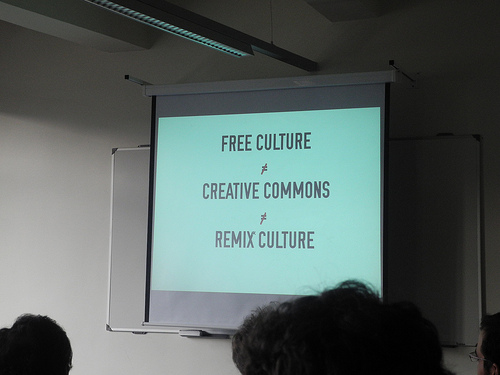

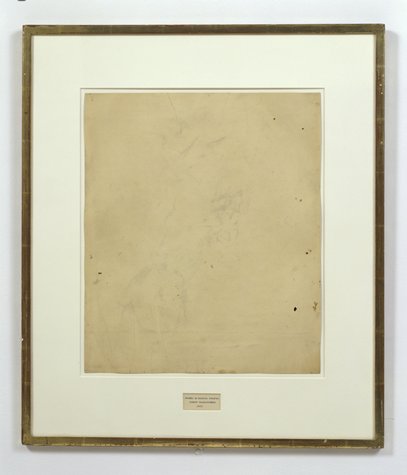

The subject of copyright cannot be avoided when discussing digital art and collaborative practices. There is a definite need to foster a safe and welcoming environment for artists and designers to produce, share and remix their work. Licensing of artwork under Copyleft licences – such as Creative Commons – helps to create this environment.

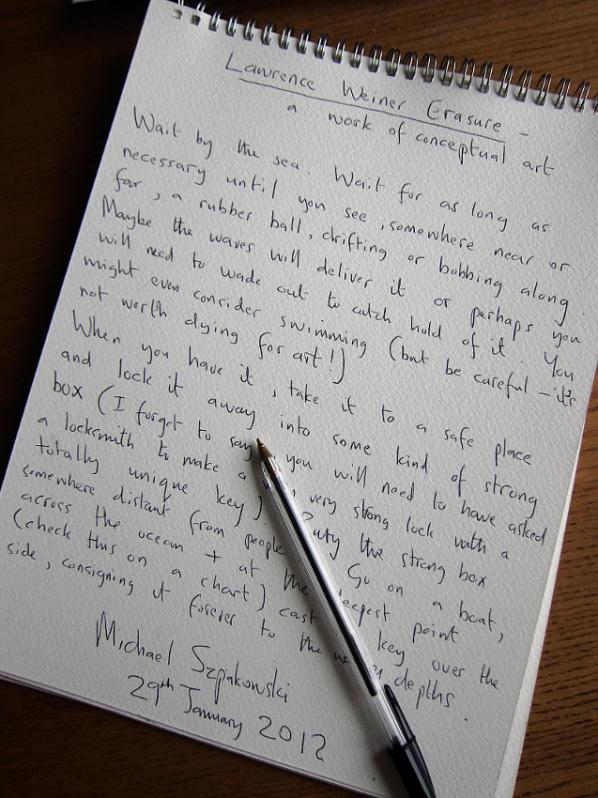

In his presentation, entitled “Libre Workflows – A Tragedy In 3 Acts”, Aymeric Mansoux was quick to point out that Creative Commons licences do not cover the source of the artwork. To put it into context, a JPG is covered by a Creative Commons licence but is the XCF/PSD file? Mansoux also considered what is actually a finished piece of artwork? In a remix culture is an artwork ever finished? Mansoux refers to this quote from Michael Szpakowski for further elaboration:

I’ve found it helpful to think of any artwork, be it literary, visual art or music as a kind of fuzzy four dimensional manifold. So the “complete” artwork is the sum of all its instances in time, and all epiphenomena. The entire artwork, seen this way, is a real and precisely enumerable sum, a concrete, not imaginary, set, which could be knowable in its entirety by something long lived and far seeing enough.

From their home town of Porto, Portugal, Ana Carvalho and Ricardo Lafuente produce Libre Graphics Magazine with ginger coons who is based in Toronto, Canada. For the production of the magazine they use Git, with their repository being hosted on Gitorious. As a tool for sharing files between collaborators Git is very useful. However, they explained that they feel they are not making effective use of all that Git has to offer. Part of this comes from the complexity of using Git. There are more than 140 commands in Git, each with their own unique function. These are usually entered via the command-line, but there are a number of programs with a Graphical User Interface (GUI) available. Programs with a GUI are usually favoured over command-line programs as they remove some of the complexity. Carvalho and Lafuente have found, however, that many of of these GUI programs simply replace commands with buttons, which doesn’t remove any of the complexity in using Git. What is needed is an easy to use specialised tool for the production of art.

In this work session, presented by Ana Carvalho and Eric Schrijver, the work group imagined how to adapt existing version control tools to meet the needs of artists and designers. The session began by taking a look at how people currently implement version control. A common practice is to manually make backups, renaming files to differentiate between stages. This can be an effective way of making different versions, but it doesn’t address other issues such as making comparisons or merging changes. The ineffectiveness of these manual methods is soon very apparent. The work group was introduced to the Open Source Publishing (OSP) Visual Repository viewer, which begins to respond to some problems with current version control systems by providing thumbnails of files in a repository.

Using this as a basis we began to look at other functions that the OSP Visual Repository viewer should have, such as the ability to compare graphical files in different ways and to revert back to previous versions or merge versions. Although there was no time to produce working code we did seek to address the complex task of merging and comparing not only the ouput file but also the working files (svg/xcf/psd).

Every good work of software starts by scratching a developer’s personal itch.

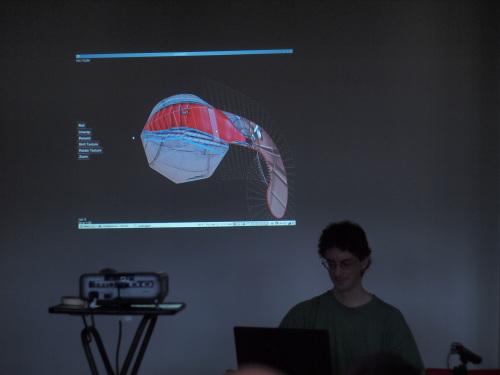

This quote from The Cathedral and the Bazaar by Eric Steve Raymond could not be more accurate in describing the motivations behind the development of Laidout, developed by Tom Lechner, a comic artist from Portland, Oregon. Perhaps one of the most impressive software demonstrations of LGRU, Laidout is a program for laying out artwork on pages with any number of folds, which don’t even have to be rectangular.

In an attempt to devise new tags that can be added to the SVG specification, Michael Murtaugh and Stephanie Villayphiou presented a work session that looked at the different ways language is interpreted by both humans and computers. To address this the work group took part in a task that saw them act as an interpreter of commands. With nothing more than a list of tags used in SVG files the work group would attempt to construct shapes.

The results varied from person to person and highlighted an important question: How can computers interpret ambiguity

Using the Richard A Bolt “Put that there” demonstration, Murtaugh showed how human-computer interaction is still based around using very clear, unambiguous commands that can be easily interpreted by computers. In SVG only the most basic of shapes – rectangles, circles and lines – are represented. But, as the work group participants asked, could there be tags to represent more complex shapes, such as a horse?

On the final day of the meeting I took part in a roundtable discussion, chaired by Angela Plohman and featuring myself, Stephanie Vilayphiou, Camille Bissuel and Ana Carvalho. The discussion first went over all that we had achieved over the four days at the meeting, and then the discussion focused on how and why we share our artwork. Expanding on the earlier quote from Szpakowski, how can we make sharing all of our artwork – including the early stages and inspirations behind it – an easier and integrated part of making artwork? In addition to sharing our final, “finished” artworks do we want to also share our processes and ideas behind the artwork? More importantly, can software easily aid this?

Other topics debated in the discussion revolved around opening up our artwork and processes to others. By opening up the development process of our artwork do we do so to invite collaborators and contributions or just observers? The Blender Open projects, for example, are highly regarded as an example of the work that can be made using open source software. The files used to make these projects are are released upon completion of the project, but the development process remains closed to the team of artists and developers. Would opening up this process to contributors add any value or could having too many ideas dilute the original vision of the project.

Although no conclusions around these topics were made, it was nonetheless important for everyone at the meeting to think critically about their practice

A concern of mine is that research is not always acted up on and exciting possibilities exist only as theory. However, I feel that the approach of Libre Graphics Research Unit, which combines research and practice, will ensure that the work undertaken at the meetings is implemented. It is actively working with developers and users to try and create solutions.

At the Co-Poistion meeting not one final product was made, but the initial vision for the future of layout was formed.

The next meeting, Piksels and Lines, takes place in Bergen, Norway and is organised by Piksel.

MONODROME: Art’s debt in times of crisis

AB3 Athens Biennale 2011 Monodrome

Curated by Nicolas Bourriaud and X&Y

23 October-11 December 2011

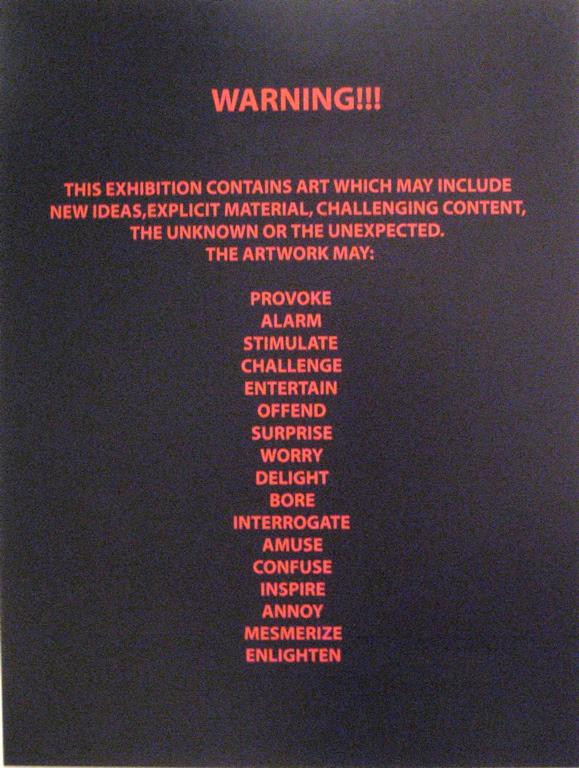

Athens Biennale 2011 was the third edition of this institution and was entitled “Monodrome”, meaning “One way street” after the 1928 text “Eisenstrasse” by Walter Benjamin. The concept of the title is obvious; after the first Athens Biennale in 2007 prophetically entitled: “Destroy Athens”, the second Biennale “Heaven” in 2009, “Monodrome” comes as a closure to this trilogy. Why Walter Benjamin? Because he was a “defeated intellectual”, according to the curators. German-Jewish philosopher, an emblematic figure of 20th century thought, gave an end to his life at the french-spanish border while trying to escape the Nazis. “He was unable to overcome his personal dead-end as a subject”, says Poka-Yio of X&Y and he continues: “The title of this exhibition after Benjamin’s text refers to a collective dead-end” currently at stake and it’s only possible fate: a cloud of doom. “Monodrome” aimed to provoke debate around “something that has fallen apart, but to also offer the possibility of a glimpse at something new to come”.

Indeed, this Biennale took place at a specific moment in Greek and global history, where all 20th century utopian narratives (i.e. modernism, ecology, metaphysics) are crashing, introducing to the whole world a humiliating and disturbing, both socially, as well as nationally, dystopian non-future. Athens, the cradle of democracy was – at the time – “rocking the world”, by suffering the experimental imposition of a non-democratic supernational regime stamped with the mark of over-privatization, a situation that immediately started spreading all over Europe. Now – that the exhibition has come to an end – nearly everyone on this planet feels that “the time” {our world – as we know it – has come to} “is out of joint”, “the very place of spectrality” (Jaques Derrida, “Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International“ Routledge, 1994: 82).

What’s art got to do with this? “Artists usually have premonitions of what’s going to happen, it is often that artists precede with their work social changes; artists are mostly intuitive, it’s at the core of their existence, this how they create” Poka-Yio says. Nicolas Bourriaud and X&Y had to deal with a situation that can be called no less than a “crisis management”. The exhibition was organized practically with no funding and was based mainly on the contribution of all participants and volunteers. The social events that were taking place during the very opening of the show were probably amongst those of the most significant importance in Greece’s postwar history. The energy and emotional vibe caused by this historical moment were the background of the Biennale and made it both a great challenge and a responsibility for the curatorial team.

Despite these critical financial and social circumstances, the Biennale was successfully realized against all odds and it can be said, that it was well received by the audience – an accomplishment on behalf of the curators who selected the works, planned and organized it. The curators of the 3rd Athens Biennale 2011 felt that “the widening situation for which Greece is a much derided yet overexposed case-study must become the focus of cultural investigation, in a way that it is no longer poignant – or even moral – to simply keep making exhibitions in the way that had become the norm in previous years”.

In order to address these issues, besides investigating the exhibition’s conceptual framework, the curators decided “to experiment with the Biennale exhibition format itself, by transforming it into an invitation to create a political moment rather than stage a political spectacle by making a call to a sit-in of collectives, political organizations and citizens involved in the transformation of society”. At another level, as the exhibition was designed and produced, its various stages of development were providing the basis for a feature film directed by Nicolas Bourriaud. Social media also played an important role in the communication strategy of this Biennale, as every event, talk, happening or performance was recorded and presented at AB3 youtube channel and one could follow it via facebook, twitter and other social platforms, as vimeo, flickr and tumblr.

The conceptual framework, upon which the theoretical thread was build, was a deep dive in the folds of Greek history. The curatorial strategy chose “to represent an ongoing crisis through historical fragments, a Benjaminian technique”. Walter Benjamin, provided with his text “Eisenstrasse” the tools for looking at history in a fragmented way, for he, according to the curators, introduced theoretical tools for looking into history with terms of “here and now”, by often making references to the city and to the popular culture of his time. “One way to talk about history is to include history”, says Nicolas Bourriaud. “The exhibition was structured as text; its narrative unfolds as one searches in the ruins and tries to read their meaning”, as one “tries to find out about new possibilities of giving meaning”.

Walter Benjamin, as a character, for the needs of this exhibition’s narrative concept was brought in a paradox dialogue with another character, a fictional one: Saint Expery’s Little Prince. This narrative plot brings this real life character, the emblematic intellectual, to meet the hero of a children’s novel, because: “a child can pose questions in an intelligent manner representing the inner child to be found in everyone” says Xenia Kalpaktsoglou of X&Y team of Athens Biennale co-founding curators. Little Prince poses all fundamental questions of “being” to the philosopher and the intellectual strives to give back the right answers. This imaginary dialogue took place in the form of sketches spreading like a graffiti-comic all over the walls of the exhibition’s main venue building. “As the intellectual retreats defeated in the face of the escalated distress, the Little Prince keeps questioning this condition with the disarming innocence and the plainspoken boldness of a child”.

The real protagonist of the exhibition, however, was Diplareios School, the main venue, a nearly disused old building located at the heart of downtown Athens in an underprivileged area, right across the City Hall and the old big open market. The local color and the smells of the market square, crowded with immigrants, ethnic shops and – especially at night – the presence of junkies, dealers and prostitutes was part of the exhibition’s “aura”. This building was literally used as a “panopticon” of both contemporary and ancient Athens and has a long history. It was built for the purposes of housing a School of Design, meant to be “the Greek Bauhaus”. Among many of its uses, it was requisitioned during the German Occupation and during the time when Athens was so badly over-built, it was hosting the offices of Urban Planning public service. The second exhibition venue was “Venizelos Museum”, a former military basis also used during the Greek dictatorship as the headquarters of torture investigating anti-regime citizens (former ΕΑΤ – ΕΣΑ).“The space is the artwork”, Bourriaud says. “Not just a venue. It’s previous functions manifest its character; it is a real protagonist”.

Diplareios School is an allegory of modern Greece surrendering itself to abandonment. Looking around all one sees is worn walls and graffiti, all one hears are the voices of protests and the ubiquitous noise of the city. The curatorial strategy for this Biennale was quite different from the two previous exhibitions, “Destroy Athens” in 2007 and “Heaven” in 2009. No big names of the international art market to be found among the artists. No self-referential patterns in this exhibition, other than “questions on the reasons behind the political crash, the crisis of moral values, the dead-end”. It was in fact a much more “introvert” exhibition, focused on the local scene, featuring mainly emergent Greek artists. The exhibited artworks in their majority came form Greece: “to include the local, to talk about local artistic production was one of our aims for this exhibition” according to Bourriaud.

Only to mention a few, Spyros Staveris, an emerging Greek photographer with a video art photo-documentation following the “Aganaktismenoi” social movement in Athens at its very birth. In the same room, “Ηommage a Athenes” a sound installation by Vlassis Kaniaris, with recorded sounds of the recent Athenian protests. One could not but mention the remarkable work of young Greek sculptror Andreas Lolis who is making cartboard boxes and felizol sculptures out of marble. “In my artwork, I try to make time stop. The reason why I am using marble, is because I want to make these fragile objects eternal”. “We all use cartboard boxes. People sleep in them. When I looked down from the windows of the Biennale venue and saw people on the terraces sleeping in cartons, it only came to me as a natural thing to co-exist with this situation – not to record it”. “This is the best time for Art. Not the art market, Art. When I recently saw the artworks of Athens Fine Art School graduates, I realized that the bubble-effect’s gone, now. These young artists, living this situation have grown into reality. There’s so much truth in their artworks”.

Another captivating artwork featured at the Biennale was “EXIT” by the Greek collective “Under Construction”, an installation of old rusty worn office desks; “in fact we present an allegorical image of Greece, using old equipment of public services, eroded now from abandonment. The hard to distinguish faded “EXIT” ‘statement’ does not exist, at least not literally”.

Rena Papaspyrou’s “Photocopies” is another stunning installation, where phone numbers printed on fragments of paper are posted on the wall. “Extending the decay of the wall, this piece secretly interacts with the graffiti notes on the wall waving alternative histories of the numerous uses of the building”. Thus the interaction between Papaspyrou’s installation and the Diplareios building creates a sense of dialogue, both in concept as well as in form.

One may wonder whether any international artists were presented in this exhibition. Lucas Lenglet, Jakob Kolding, Norman Leto, Caroline May, Josef Dabernig, Józef Robakowski only to mention a few, and of course, Julien Prévieux’s “A La Recherche du Miracle Economique”.

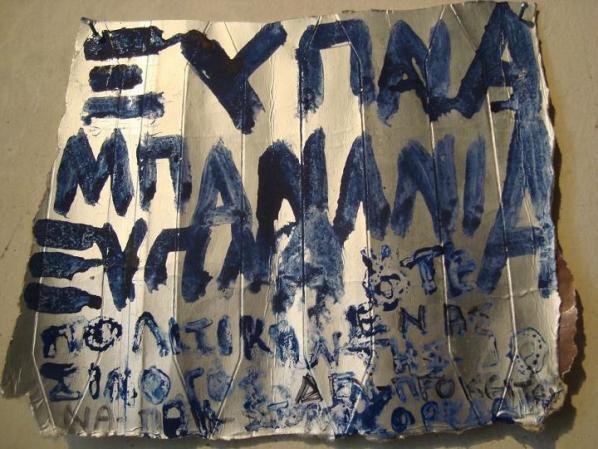

“This is a fragmented exhibition”, Bourriaud says: “one can see in this exhibition various media, film, collages, photographs, sculptures, drawings, paintings”. Amongst the artworks, the visitor would encounter several objects that have nothing to do with art but were used as tools for the exhibition narrative: a time lapse, a trip down to memory lane. For example, an object used for this purpose was a placard, that the curators found discarded after a recent protest in Athens. On the placard was written: “WAKE UP BANANA REPUBLIC”.

Also, the lost opportunity of Greek design; some of the works of students of Diplareios School were exhibited; they had been left in the old School. Posters by Greek National Tourism Organisation by Michael and Agnes Katzourakis. Pictures of Andreas Papandreou with Gaddaffi during the “good old days”. Air stewart and pilot uniforms from The Olympic Airways. In the attic of the old School, the crescendo of the exhibition’s narrative: as one faces the image of the ancient monument of the Acropolis through the dirty windows of the old School, a dead pigeon that was found there and was respectfully kept by the curators as a symbol, an omen.

The 3rd Athens Biennale 2011 was a double project; in both the form of an international exhibition and a feature film. The return of Walter Benjamin as a ghost that comes to haunt the city of Athens during this crisis period is the theme of a film directed by Nicolas Bourriaud. “It is a feature film, a film as an exhibition, a documentary based on actual characters, a docu-fiction and an experimentation with the platform of the Biennale”, says Bourriaud. “The film will be a work of fiction albeit based on real events. This is the first time that the relationship between contemporary art and filmic language is investigated in this way”. A catalogue will document the whole process of the 3rd Athens Biennale, and a DVD edition, including the movie and documents on participants’ works, will be published. Following the completion of the Biennale, the film in its final format will be distributed both in the art world and the cinema circuit. The executive producer of the movie is Kino Prod (www.kino.fr) in Paris.

Ironically, and sadly, “Monodrome“’s TV trailer was censored by the Greek National Broadcaster (ERT), who was also the major communication sponsor of the Biennale. The director of this 26’’ spot, Giorgos Zois, a talented young Greek filmmaker who has already won several international distinctions and prizes – according to his official statement as an answer to this act – attempted to “deliver the theme of the 3rd Biennale MONODROME (meaning one-way) in a series of slow-motion images of a forcibly accelerated reality depicting the one-way contemporary condition. Instinctively and suspiciously the national Greek television judged the content to be against the law that forbids “messages that contain elements of violence, or encourage dangerous behaviors, or insult human dignity”. “Apparently the daily transmission of aggressive porn-like governmental policies, does not count as an insult to viewers”. You can watch the trailer here:

This show is curated jointly by Helen Sloan of SCAN and the John Hansard Gallery, Southampton. There is both curatorial interest in the technological aspects of the work as well as the subject matter of the war artist. Sloan was approached by the Arts Council in terms of initiating a project for the ‘Interact’ series of commissions, on which she worked with David Cotterrell. In 2007, Coterrell went to Afghanistan as artist-in-residence for a month in a field hospital. At his residency in 2008, at SEOS (now Rockwell Collins), a company that makes flight simulators. He explored the nature of representation itself, and particularly ‘the suspension of disbelief’. This relates to our relationship with digital data, and how often we regard it as more real, due to its nominal representation of reality and our use of this as information.

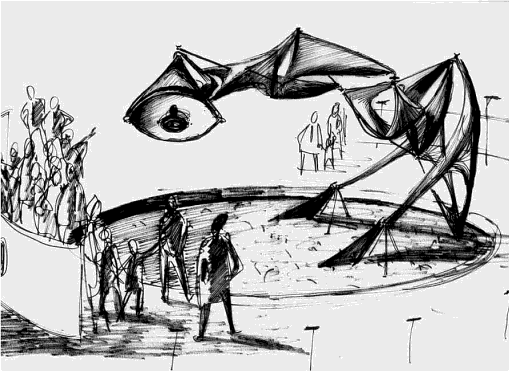

What appear to be ‘A-life critters’, are in fact scaled down human forms. Trawling across a dust-sculpted landscape, the real of the chalk dust intersects with the virtual projections of the A-life program which is mapping the movement of these forms to the reality of the sculpted landscape.

David Cotterrell doesn’t want to show pictures of the atrocities of war, but instead focuses on the complex experience of lived space in territorial combat and its mapping. He presents a kind of ‘topo-analysis’ of an imaginary space, with nominal figures located and moving in spatial relationship to one another. In Observer Effect the gallery viewer triggers the movement of the virtual entities who are attracted by a ‘sphere of influence’ to the viewers position in the gallery space. In this way, the phenomenon of space, location and relationship and the concomitant fear of combat, casualty, and mortality are implicit in the context of this exhibition.

Cotterrell has chosen to interrogate image making using technology, much as Vilém Flusser recommended, together with a lack of acceptance of the ‘normal’ indexical uses of photography and film about which he is ambivalent, although he used these media in Afghanistan.

What these works achieve is the proposition of a ‘possible world’ where depersonalisation is understood as part of the virtual, nominal, mapped collective fantasy, which somehow then relates to the changing ‘world view’ of the Western citizen. It is also where the reference to science fiction comes from, ‘Monsters of the Id’ referring to the film Forbidden Planet. Science fiction is perhaps referred to in order to re-conceptualise our thinking as part of this Western view. In this sense it is about empowering us to think differently about the portrayal of conflict itself in the twenty-first century and to understand it as lived experience within specifically managed environments.

This is largely achieved through Cotterrell’s translation of his own experience as war artist in Afghanistan. He seems to want his experience to affect the viewer in a way which is different from that which he witnessed, to a reliance on the imagination instead, provoked by the portrayal of the landscape and militarised environment. Instead the exploration is one of attempting to convey the sense of isolation he felt in the military field hospital.

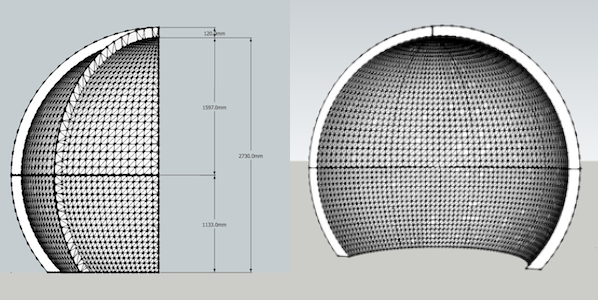

What becomes apparent on seeing this work, is that we are being presented with data objects, which we are then encouraged to relate to, as though they are the nominal representation of real subjects. It is significant that the work is realised with new technology. All three main works in the show explore a similar landscape but use three different projection systems. In Observer Effect the system relates to interaction with the gallery visitor who influences the installation in spatial relativity, through a device that senses and then calculates, through the algorithms and maths of a game engine, their relationship to the virtual space. Alternatively, in Searchlight 2, there is a synthesis between real and virtual as the figures traverse the landscape. He has said in relation to this piece that ‘from a great distance we lose empathy with the figures crossing the landscape’. In Apparent Horizon, the viewer encounters a semi-immersive relationship with video projected onto specially designed hemi-spheres, a view of the horizon, and a lengthy period of waiting for something to happen, which captures the tension between periods of violence. In this sense the artist has worked both as a war artist and as an artist using and developing the application of new technologies.

He talked about computer programming having a tendency towards ‘megalomaniac control’, and that the installation was addressed towards ‘how an audience inhabits a gallery’, with no ‘fetishizing of computers’. The residency at SEOS has obviously affected the nature of the technology employed in the work, with two ‘black boxes’ enabling aspects of the projections, as well as the hemi-spheres as immersive hardware. The system of Observer Effect is adaptive and therefore responds to the accumulated impact of viewers in the gallery. He talked about how a commercial games company would find it easy to make, but for him it had been a steep learning curve.

Cotterrell was able to return to Afghanistan in early 2008, due to support from the RSA, and was therefore able to look at the territory of the desert ‘outside the bubble of the military’, which had given him a limited understanding of the environment, a sense of dislocation, and the apprehension of casualties brought from the desert war zone. On this occasion he grew a beard and was able to disguise himself sufficiently so that he could interact with different groups of Afghani people and to gain a ‘pluralism of experience’, as on this occasion he was not part of the chain of command. In this second journey, he was ‘low value’ and therefore able to wander more freely.

Initially, he found it difficult to deliver art work in response to what he had experienced in Afghanistan. He was aware of the historical dilemma of the conflict between medicine and war. But for him, the trauma was ‘quieter’ and involved loss of identity. For example, the twenty-one year old soldier who after severe injury was ambiguous about what would happen for the rest of his life.

He found the operating theatre at the field hospital was ‘like a stage set’, and he took photographs of the surgeons, but found that the documentation ‘didn’t document’ sufficiently his lived experience. At one point he left a video camera running, documenting the arrival of casualties and then, when he was back at home, he edited the footage and left only the moments when attendant individuals ‘allowed their guard to drop’. He questioned though, whether ‘it was right to document trauma’. This left him with the ‘impossibility of conveying content’.

As war artist he has chosen to explore the military and political relationships with the technological portrayal of soldiers and civilians within a territorial combat zone. This is sufficient for Cotterrell in order to convey the sense of isolation and the particular landscape of Afghanistan. In this way, apprehending the virtual or nominal as a way of perceiving what could be real, and is real in a conflict situation, puts the viewer in a complex position, of both suspending disbelief and recognising the construct. The final work Monsters of the Id, includes in a small installation an army tent, desk and military communications equipment. This conjures up an image of Cotterrell’s experience as a war artist, although in fact it is his portrayal of how we might think of it – as naïve in other words.

For the team of curators, gallery staff, and the artist, it has been curatorially important to work within the gallery space and Cotterrell claims that the ‘virtual can only really be understood in a gallery context.’ This is enabled through the works being not fully immersive so that you can stand back and reflect. As such the show is all about ‘the manipulation of imagery’ informed by the residencies in Afghanistan and at SEOS.

The exhibition continues till 31 March 2012 at the John Hansard Gallery, Southampton

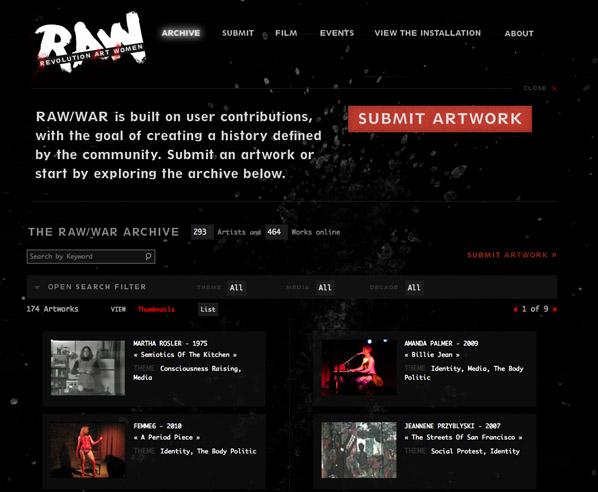

Women, Art & Technology is a series of interviews that seeks to find different perspectives on the current voice of women working in art and technology. The series continues with curator Sarah Cook.

Sarah Cook is a curator and writer based in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, and co-author with Beryl Graham of the book Rethinking Curating: Art After New Media (MIT Press, 2010). She is currently a reader at the University of Sunderland where she co-founded and co-edits CRUMB, the online resource for curators of new media art, and where she teaches on the MA Curating course. Most recently she curated the Mirror Neurons exhibition that is part of the AV Festival running through till March 31, 2012, in New Castle.

Rachel Beth Egenhoefer: Over the last few years you have curated a number of exhibitions in relation to festivals of media art. Could you start by giving us a brief description of the AND (Abandon Normal Devices) Festival and your involvement in it last year?

Sarah Cook: My involvement in the AND Festival was to curate a small group exhibition for the galleries at Liverpool John Moore’s University Gallery (in the Art and Design Academy Building). The exhibition was a part of AND but was also curated for the crowd of academics attending the Rewire conference which I was co-chairing. Rewire was the Fourth International Conference on the Histories of Media Art, Science and Technology. A three-day, peer reviewed, international event, the conference had over 150 speakers and three keynote lectures including one by Andrew Pickering, author of the book The Cybernetic Brain. The exhibition, Q.E.D., included seven projects all of which questioned how we can know anything but looking at documentation of it (a problem for art historians of course!). In 2011 the AND Festival had as its theme questioning belief and the structures of belief, so this exhibition complemented their huge and diverse programme.

I had been involved in previous Media Art Histories conferences – having co-curated the exhibition “The Art Formerly Known As New Media” for the first one, Re:Fresh!, which was held in Banff in 2005.

RBE: Could you give us a few examples of work from your exhibition that you felt really abandoned normal devices or methods of production and presented new perspectives?

SC: I selected works in which the artists might have abandoned normal ways of making art, to undertake experiments of sorts, experiments demonstrating phenomena in the world. (Q.E.D. is from the Latin ‘Quod Erat Demonstrandum’ meaning what was to have been demonstrated or what was required to be proved). I wanted a show in which skepticism was the norm, and a perfectly valid methodology for artists to employ as they go about investigating, modeling or representing the world around them.

So there was documentation of Norman White and Laura Kikuaka’s 1988 project Them Fuckin’ Robots — an attempt to create one male and one female electro-mechanical sex machine, without sharing in advance any information about materials, function, or how they would connect.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg and Sascha Pohflepp’s work-in-progress, Yesterday’s Today, was part of their Southampton University commission investigating the limits and possibilities of models for describing knowledge. They started with the oldest predictive model known to science, and a very British one at that, the weather forecast, and attempted to cool the gallery space to the predicted temperature for the day. There was a heatwave in Liverpool that week in September, so it was a great to experience reality and a model of reality simultaneously.

Axel Straschnoy, along with his many collaborators at the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University (Ben Brown, Garth Zeglin, Geoff Gordon, Iheanyi Umez-Eronini, Marek Michalowski, Paul Serri, Sue Ann Hong), showed the documentation of their attempts to create a robot that performs art and a robot that watches and appreciates performance art. The informal video interviews with the artificial intelligence engineers discussing how a robot might want to make art are brilliant and often funny.

RBE: I understand your work with AND has lead to a new project recently launched with the AV Festival.

SC: Yes, I have curated an exhibition for the AV Festival, taking place across Newcastle, Sunderland and Middlesborough through March 2012. The show is at the National Glass Centre in Sunderland and is called Mirror Neurons. While AV Festival has a theme of Slowness, Mirror Neurons seeks to question time delay, media processing, and the time it takes for our cognition to kick in when we are in the presence of art – interactive, reactive or not. One of the pieces which was in Q.E.D is in this show also: Scott Rogers’ Self-Flowing Flask – a glass object made based on a drawing by 17th century scientist and inventor Robert Boyle, shown alongside a digitally created animation of it. There is a real sense of confusion by viewers when they see the object: Does it work? Could it work? How would it work? And then when they see the animation they have to work out if it is real or not.

RBE: You mention “Slowness” as the theme for the AV Festival. “Slowness” is also a trending theme right now with slow food, slow craft, etc. How do you see slowness in relationship to technology which is usually portrayed as something “fast”?

SC: The theme of slowness was chosen by AV Festival director Rebecca Shatwell, and so I was glad to leave exploration of that notion to her and her programme, which is stacked with fantastic works of art in moving media (film and video) and sound and performance. In the exhibitions I’ve curated for AV Festival, which include both Mirror Neurons, and a new commission from New York-based artist Joe Winter – also on view at the National Glass Centre in Sunderland – I’ve focused less on the theme of slowness than on the human action of recognising time passing, the lag between our perception or understanding of time and space, and our acknowledgement of our own actions within it.

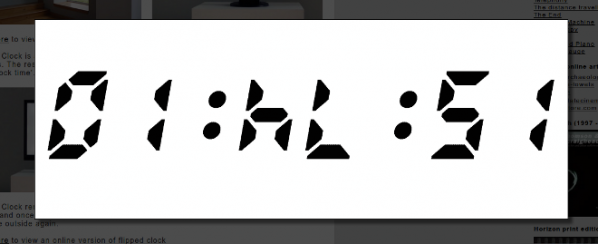

There are some works in Mirror Neurons which seem, on the surface, to be about time, but which play with the possibility of shifting time, or at least reprocessing it or subjecting it to a new set of rules, with computer technology. By the same token, these works then also implicate you, the viewer, in the time of their action, in your realization of what it is those works are ‘doing’. For instance, Thomson & Craighead’s work Flipped Clock, is a standard computer digital clock, but with the numerals rotated, so that it is defamiliarised and causes you to do a double take and spend a moment working it out. And Michael Snow’s WVLNT (Wavelength for those that don’t have the time) was 45 minutes, now 15!!, in my mind collapses time and space, by superimposing scenes from his 1967 structuralist film – not speeding it up but overlaying it, and seeing through it from beginning to end within the same frames.

Last comes Joe Winter’s work (which was also included in Q.E.D in the form of wall-based works which appear to be representations of astronomical or geological phenomena, but are made from standard office photocopier images or meeting room whiteboards). For the AV Festival I commissioned him to make a new work for the National Glass Centre also. …a history of light: variable array is comprised of a series of sculptural works which appear like lovingly-made office in-box trays to hold documents. Only they are ranged on white pedestals across a sunny balcony space, and contain coloured craft paper and plates of glass produced by Cate Watkinson. The idea is that over the time of the exhibition (1 March to 20 May) the sunlight will fade the coloured paper, through the plates of glass, and abstract images, based on the patterns and effects in the glass, will result. The images are both created, and destroyed, by the light, over time. Joe’s previous works have all dealt in conceptions of time – deep time, geological time, astronomical time and media time – and his work takes its aesthetics from the media and technology which surrounds us, in mundane spaces such as the office cubicle or the classroom, which while might contain ‘fast’ technology, such as computers, also contains quite ‘slow’ or old or timeless technology, such as chalk, or paper.

RBE: This interview is going to be part of a series of interviews with women working in Art & Technology. What do you consider to be important today about being a woman working in art & technology? Do you think it is still useful to discuss the female voice in the field?

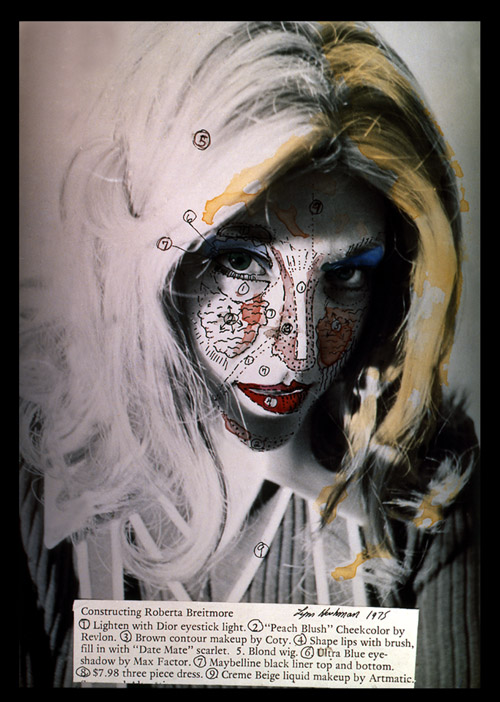

SC: I suppose there is an interesting generational break in the art and technology world at the moment as regards women’s work. I am keenly aware of (and tremendously grateful for) the work of a slightly older generation of women than me, including curators, who set up networks, facilitated international exchange, built the platforms which new media artists can work on. This generation also includes important women artists who worked with technology, gaining access to labs and high tech equipment to make work – some understanding it technically better than others, many working with the help of (often male) programmers.

In the exhibition Mirror Neurons is the work of Catherine Richards, a media artist from Canada whose work I wrote about in my PhD dissertation. For her career to date she has investigated how our bodies are plugged in to the electromagnetic spectrum which surrounds us, making Faraday Cages and copper-woven blankets to insulate us from these signals. Other of her work makes visible the connection between us, as electric beings, and our techno-environment. For the work on view in Sunderland, which was made in 2000, she worked with expert vacuum physicists and scientific glass producers at the National Research Council of Canada. For other works she has collaborated with software engineers (it was an early web-based project of hers which led in part to the invention of the software Java). She plays an important role also teaching art students, reminding them of the history of media art, which is often overlooked, and of where these technologies we take for granted come from.

Now that technologies are more ubiquitous there is a younger generation of women artists working in the field, under their own initiative. For instance, the new Pixel Palace programme at the Tyneside Cinema included three women artists in residence earlier this year – working in sound, film and digital media. Sometimes I do wonder what the preceding generation is up to; have they been able to keep up with new technologies or stuck with older ways of doing things? Have they changed tactics and after working so hard to establish themselves in what was then a rather male technological world, decided to move on? Like any field, the art and technology world will have its share of ‘old boys’ but I suppose in my work I strive to always value the collaborative relationships I have with artists and other curators, of any generation and any gender.

Also read – Woman, Art & Technology: Interview with Lynn Hershman Leeson By Rachel Beth Egenhoefer.

“It is not accidental that at a point in history when hierarchical power and manipulation have reached their most threatening proportions, the very concepts of hierarchy, power and manipulation come into question. The challenge to these concepts comes from a redsicovery of the importance of spontaneity – a rediscovery nourished by ecology, by a heightened conception of self-development, and by a new understanding of the revolutionary process in society.” Murray Bookchin. Post-scarcity and Anarchism (1968).

The rise of neo-liberalism as a hegemonic mode of discourse, infiltrates every aspect of our social lives. Its exponential growth has been helped by gate-keepers of top-down orientated alliances; holding key positions of power and considerable wealth and influence. Educational, collective and social institutions have been dismantled, especially community groups and organisations sharing values associated with social needs in the public realm. [1] Bourdieu.

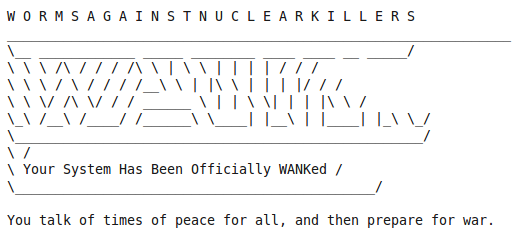

In this networked society, there are controversies and battles taking place all of the time. Battles between corporations, nation states and those who wish to preserve and expand their individual and collective freedoms. Hacktivist Artists work with technology to explore how to develop their critical and imaginative practice in ways that exist beyond traditional frameworks of art establishment and its traditions. This article highlights a small selection of artists and collaborative groups, whose work is linked by an imaginative use of technology in order to critique and intervene into the opressive effects of political and social borders.

In June 2000, Richard Stallman [2] when visiting Korea, illustrated the meaning of the word ‘Hacker’ in a fun way. When at lunch with some GNU [3] fans a waitress placed 6 chopsticks in front of him. Of course he knew they were meant for three people but he found it amusing to find another way to use them. Stallman managed to use three in his right hand and then successfully pick up a piece of food placing it into in his mouth.

“It didn’t become easy—for practical purposes, using two chopsticks is completely superior. But precisely because using three in one hand is hard and ordinarily never thought of, it has “hack value”, as my lunch companions immediately recognized. Playfully doing something difficult, whether useful or not, that is hacking.” [4] Stallman

The word ‘hacker’ has been loosely appropriated and compressed for the sound-bite language of film, tv and newspapers. These commercial outlets hungry for sensational stories have misrepresented hacker culture creating mythic heroes and anti-heroes in order to amaze and shock an unaware, mediated public. Yet, at the same time hackers or ‘crackers’ have exploited this mythology to get their own agendas across. Before these more confusing times, hacking was considered a less dramatic activity. In the 60s and 70s the hacker realm was dominated by computer nerds, professional programmers and hobbyists.