To read Part 1 of this article visit this link:

http://www.furtherfield.org/articles/trajectories-how-reconcile-careerist-mentality-our-impending-doom-part-14

To read Part 2 of this article visit this link: http://www.furtherfield.org/articles/trajectories-how-reconcile-careerist-mentality-our-impending-doom-part-24

Drawing together the diagnoses which recur throughout the literature of the moment, such as Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Fisher 2009), First as Tragedy, Then as Farce (Zizek 2009a) and The Coming Insurrection (The Invisible Committee 2009) alongside the key suggestions, ideas and solutions from these two manifestos, our ‘plan of action’ begins to materialise.

In the spirit of Pascal’s famous ‘wager’ (Hajek 2008) the plan aims to cover all bases: our active and / or passive responses to the situation. Encouraging the belief that we might still be able to use our roles as artists to incite the radical change to our societal structure (in the art world and globally) needed to avert climate catastrophe, whilst simultaneously developing philosophies for coping with our lives – finding meaning and happiness – should our active response fail.

The seven points below offer a set of guidelines for rethinking our lives, which should act as the starting points for redefining our roles as artists and thinking about how it might be possible to reconcile ‘the careerist mentality’ into which we have been inculcated with the possibility of ‘our impending doom’:

1. stand back and view the world objectively

The main focus of Uncivilisation and our greatest existential priority is to enable ourselves to grasp perspective, not only of the relative insignificance of our individual career plans within the wider world, but more pertinently of the fragility of our entire species within the greater timescales of the universe. Once this mind shift is achieved it becomes easier to distil what is actually important in our lives – happiness and our two unending desires for survival and meaning (Kingsnorth & Hine 2009, p.2). Only then will the remaining six points become easier to implement.

2. offer an external critique of the system

In our new ‘state of mind’ it becomes easier to see the systems in which we have been blindly functioning. From beyond the grasp of the dominant hegemony we can offer a vital ‘external critique’. As Chantal Mouffe suggests, our duty as artists then becomes to challenge the “given symbolic order” and the “existing consensus” (Mouffe 2007) – to revivify the belief that ‘an alternative’ is possible.

3. develop ways or working outside institutions

Our criticisms should extend to the hegemony of the art world, severing our dependence on “legitimisation” (Araeen & Appignanesi 2009, p.500). We must have the courage of conviction in our ideas to find ways of operating outside of art world institutions, especially the marketplace. We require what Mark Fisher describes as a “positive disengagement” – a protest of sorts – which should take the form of “collective activity” (Fisher 2006) to help us break out of our entrepreneurial solitude…

4. escape solipsism; work with and not against peers

As individual artists, working alone, we typify the global trend towards what Adam Curtis calls the “empire of the self” (Curtis 2002), in which anxiety and paranoia are rife. For Araeen, it is this “extreme self-centred individualism of art today” which is “a disturbing symptom of its detachment from our collective humanity” (Araeen 2009, p.679). And so, we must prioritise “collective activity” (Fisher 2006), learning to work in co-operation rather than competition with our friends. Peer support will relieve our paranoia and allow our capacities for empathy to be resuscitated.

5. reject ego and embrace anonymity

Collaboration will enable us to surrender our egos to the collective force; liberating our ideas from their “containment” (Araeen & Appignanesi 2009, p.500). We should “flee visibility” and embrace the new powerful, but faceless forms of resistance being pioneered by The Invisible Committee – encouraging us to turn our “anonymity… to our advantage” (The Invisible Committee 2009, pp.112-3).

6. create free ideas, not objects for sale

Our role as artists should be to focus on the creation of ideas, not the production of objects. The rejection of commodity is an important part of our ‘disengagement’ from the marketplace. Our ideas should not remain private property and should be gifted to the ‘creative commons’ for the ‘public good’ (Blackburn 2009). As Hakim Bey suggests in his book Immediatism, “The more imagination is liberated and shared, the more useful the medium” (Bey 1994, p.36).

7. abandon the trajectory; find motivation in immediacy, not legacy

We must cease to think of our art as a means to an end; a way of getting somewhere – into a book, a magazine, an exhibition etc, as it is pointless to base our motivations on a future which will, very likely, not be able to function as the present does. We should abandon the very notion of a career trajectory and learn to focus our attentions on the reality of now. Without an overpowering emphasis on the future our anxieties will begin to dissolve and we will be able to unearth the absolute state of happiness that exists in the “continuous present” (Crisp 1996, p.54). We must remain alert and not complacent, notice and appreciate the things which are actually good and, as Kurt Vonnegut suggests, continually remind ourselves “if this isn’t nice, I don’t know what is” (Vonnegut 2003).

The ‘plan of action’ forms the basis of a new ideology, which acts as a counterpoint to neoliberalism – advocating our extrication from the system of capital that is the “ultimate cause” (Fisher 2009, p.70) of our environmental crisis. Heavy on words such as ‘abandon’, ‘reject’, ‘stand back’ and ‘disengage’ it calls us to make radical changes. It demands that we overcome our “path dependency” (Abbing 2002, p.96) by shifting our goals away from the fantasy status of the ‘successful’ artist. It all makes our new role seem far less glamorous than our dreams may have envisaged – insisting that we renounce our vanity, abandon our egos, move towards collectivism and anonymity; in short, commit “career suicide” (Sharp 2010, p.52).

But would it really be so beneficial to scrap everything and start again – to admit that our lives up until this point had been “lost causes” (Zizek 2009b)? The emphasis of this essay is on the possibility of reconciliation. Therefore, it aims to explore what positive characteristics of ‘the careerist mentality’ that has driven us to take this individualistic path, we might be able to “salvage” (Williams 2009) and, in doing so, reconfigure to become a positive force that can help us put the plan into action all the more effectively: to take the necessary risks and make a stand for the ‘right’ ethical choice.

Counter to Kant’s belief that the fields of ethical decision making (part of ‘practical reason’) and aesthetic decision making (part of ‘judgement’) be kept separate (Guyer 2004), it appears that the gravity of the situation we face means that these two spheres must begin to coincide. Indeed, in his final book Chaosmosis: An Ethico Aesthetic Paradigm, Felix Guattari argues for the culminating phase of art to be one in which it has an integral relationship with ethics (Guattari 2006). And so, the ethical implications of the ‘plan of action’ become difficult to ignore. Its focus on ‘tugging our attention away’ from our obsession with our own lives to reconnect with our “collective humanity” (Araeen 2009, p.679) is clearly a moral proposition, soliciting a shift from prudent self-interest towards more altruistic behaviour.

The conflict that emerges between the self-interest of ‘the careerist mentality’ and the apparently selfless altruism called for by several points of the ‘plan of action’ has long been the concern of moral philosophy. The recurring question being whether they can ever coexist or be reconciled. In her essay Altruism Versus Self-Interest: Sometimes a False Dichotomy, Neera Kapur Badhwar argues that in certain cases, where individuals display particular characteristics, reconciliation of these traditional polarities is possible (Badhwar 1993).

Badhwar’s essay is based on the analysis of extreme instances of altruism (in this case the behaviour of those who rescued / harboured Jews from the Nazis in the Second World War). What is interesting, and indeed relevant, is the way in which she demonstrates how these definitive acts of altruism are able to coexist with self-interested motivations. Her argument is based on an extension of the categories of self-interested motivation from “feeling virtuous, becoming famous, gaining wealth” (Badhwar 1993, p.101) – equate these to the artist’s extrinsic motivations “money, recognition, fame” (Abbing 2002, p.82) – to include “integrity and self-affirmation” (Badhwar 1993, p.101) – read the artist’s intrinsic motivations of “inner gratification or private satisfaction” (Abbing 2002, p.82). Even though she acknowledges that these altruistic acts were carried out with an “awareness of the risk, in the absence of expectations of material, social, or psychological rewards [and with] the spontaneity of their choice to help” (Badhwar 1993, p.96), she demonstrates that it was precisely because these individuals took the risk that they were able to satisfy the:

“fundamental human interest, the interest in shaping the world in light of one’s own values and affirming one’s identity.” (Badhwar 1993, p.107)

Furthermore, she unearths another peculiarity at the heart of the dichotomy of individualism / collectivism (Triandis 1995) which also becomes key to the possibility of reconciliation. The individuals that she studied were compelled to carry out these altruistic acts because they were able to perceive of themselves as part of the “collective humanity” (which Araeen demands we reconnect with) and so had a more developed capacity for empathy. But, moreover, that it was something inherent in their individualism that gave them the “confidence in the value of their mission, and their own capacities for carrying it out” (Badhwar 1993, p.100): to stand away from the crowd and to stand up for what they believed to be right.

Following Badhwar’s argument, it becomes possible to identify the first of the characteristics of ‘the careerist mentality’ we should aim to salvage. For it is our “flair, self-assurance, and… sense of audacity” (Abbing 2002, p.95) which we shall have to depend on in order to take the risk necessary to make a stand against the mainstream.

What might it look like if we took the risk? What might we end up with if we followed the points in the ‘plan of action’ to the word? It is possible that rather than resulting in a radical new type of art practice, what would actually take place is a shift away from art and into the field of activism.

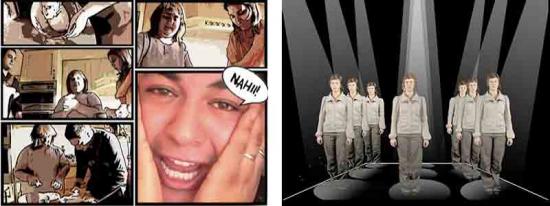

The Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army (CIRCA) was formed in 2003, to mark the official state visit of George W Bush to London at the onset of the Iraq war. It aimed to bring together “the ancient practice of clowning and the more recent practice of nonviolent direct action” (CIRCA 2003) – staging a series of strategic protests as part of an ongoing offensive against the evils of ‘war’ and ‘capitalism’. Before the protests at the G8 Summit at Gleneagles in 2005, the Rebel Clown Army embarked on a national recruitment tour of the United Kingdom. Anyone and everyone was invited to join, the only stipulation being that Basic Rebel Clown Training (BRCT) was first undertaken.

Much like the ‘plan of action’, the BRCT process focuses on the individual’s emancipation – on “transformation” and “personal liberation” from the dominant hegemony (CIRCA 2003). This internal reprogramming enables clownbatants, as they are known, to shut off their previous assumptions about hierarchical power structures and to step back and see the world with fresh eyes. From this new perspective the absurdity of a situation in which a line of protesters face-up against a line of police, becomes apparent. Beyond the signifiers of each others’ uniforms, Ranciere’s notion of the omnipresence of equality becomes evident (Ranciere 2007) and play and humour then perhaps do seem the natural human responses. Against the forward planning tactics of a traditional army (and indeed the career-minded artist) CIRCA’s emphasis is on spontaneity: “because the key to insurgency is brilliant improvisation, not perfect blueprints” (CIRCA 2003).

In a uniform which combines camo and greasepaint, clownbatants (as Point 5. suggests) ‘reject ego and embrace anonymity’ and so their inhibitions and embarrassment become irrelevant. So much more becomes possible without the worry of how they are perceived, of how others will judge them. Their individual subjectivities come together as a collective force of resistance. Their creativity exists in a space beyond the system of capital and they are utilising it to actively fight back.

The founders of the Rebel Clown Army were so aware of the importance of creativity in the process of resistance and of the potential for an evolution between art and activism, that they later set up the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (Lab of ii) as “a space to bring artists and activists together” (Harvie et al. 2005, p.249). The idea was to enable situations where they could work together and transfer skills – cultivating confidence in their “creative capacity as [a] fundamental tool for social change” (Lab of ii 2005). Functioning across the public realm, art world institutions and sites of traditional protest, the Lab of ii manages to successfully infiltrate and subvert different aspects of the hegemony. Most recently at Tate Modern in London, where under the banner of Disobedience Makes History – a two-day workshop on “art-activism” – they deliberately disobeyed the curator’s orders, encouraging participants to aim public attacks relating to the climate crises directly at the museum’s sponsors BP (Jordan 2010, p.35).

To read Part 4 of this article visit this link: http://www.furtherfield.org/articles/trajectories-how-reconcile-careerist-mentality-our-impending-doom-part-44

————

References:

Araeen, R., 2009. Ecoaesthetics: A Manifesto for the Twenty-First Century. Third Text, 23(5), 679-84.

Araeen, R. & Appignanesi, R., 2009. Art: A Vision of the Future. Third Text, 23(5), 499-502.

Badhwar, N.K., 1993. Altruism Versus Self-Interest: Sometimes a False Dichotomy. In Altruism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 90-117.

Bey, H., 1994. Immediatism, Oakland, California: AK Press.

Blackburn, S., 2009. Do we need a new morality for the 21st century? The Guardian Culture Podcast. Available at: www.guardian.co.uk/culture/audio/2009/nov/02/cambridge-festival-of-ideas.

CIRCA, 2003. About the Army. Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army website. Available at: www.clownarmy.org/about/about.html [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Curtis, A., 2002. The Century of the Self, BBC 4.

Crisp, Q., 1996. The Naked Civil Servant, London: Flamingo.

Fisher, M., 2006. Reflexive Impotence. k-punk blog. Available at: k-punk.abstractdynamics.org/archives/007656.html [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Fisher, M., 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, Ropley, Hampshire: 0 Books.

Guattari, F., 2006. Chaosmosis: An Ethico Aesthetic Paradigm. In Participation. London / Cambridge, Mass.: Whitechapel / MIT Press.

Guyer, P., 2004. Immanuel Kant. In E. Craig, ed. Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. London: Routledge.

Hajek, A., 2008. Pascal’s Wager. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at: plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/pascal-wager [Accessed May 3, 2010].

Harvie, D. et al. eds., 2005. Shut Them Down!, Leeds / New York: Dissent! / Autonomedia.

Jordan, J., 2010. On refusing to pretend to do politics in a museum. Art Monthly, (334), 35.

Kingsnorth, P. & Hine, D., 2009. Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto. Available at: www.dark-mountain.net/about-2/the-manifesto.

Lab of ii, 2005. About Us. The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination website. Available at: www.labofii.net/about [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Mouffe, C., 2007. Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces. Art & Research, 1(2). Available at: www.artandresearch.org.uk/v1n2/mouffe.html [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Ranciere, J., 2007. Hatred of Democracy, London: Verso.

Sharp, C., 2010. Career Suicide. Art Review, (40), 52-4.

The Invisible Committee, 2009. The Coming Insurrection, Los Angeles / Cambridge, Mass.: Semiotext(e).

Triandis, H., 1995. Individualism and Collectivism, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Vonnegut, K., 2003. Knowing What’s Nice. In These Times. Available at: www.inthesetimes.com/article/knowing_whats_nice [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Williams, E.C., 2009. Putting the punk back in salvage (where it was not to begin with). Socialism and/or Barbarism blog. Available at: socialismandorbarbarism.blogspot.com/2009/08/putting-punk-back-in-salvage-where-it.html [Accessed May 4, 2010].

Zizek, S., 2009a. First As Tragedy, Then As Farce, London: Verso.

Zizek, S., 2009b. In Defense of Lost Causes, London: Verso.

To read Part 1 of this article visit this link:

http://www.furtherfield.org/articles/trajectories-how-reconcile-careerist-mentality-our-impending-doom-part-14

To read Part 2 of this article visit this link: http://www.furtherfield.org/articles/trajectories-how-reconcile-careerist-mentality-our-impending-doom-part-24

To read Part 3 of this article visit this link: http://www.furtherfield.org/articles/trajectories-how-reconcile-careerist-mentality-our-impending-doom-part-34

Returning to Badhwar’s essay, it is important to note the impulsive and/or compulsive nature of the acts of altruism that she studied – “the spontaneity of their choice to help” (Badhwar 1993, p.96). She observes that:

“Those who acted spontaneously, then, acted with a sense that they had no alternative but to help, and that, under the circumstances, helping was nothing special… [Their actions were] a spontaneous manifestation of “deep-seated dispositions which form one’s central identity” or character.” (Badhwar 1993, p.97)

Of course, impulsion and / or compulsion are not the sorts of qualities which can be taught or learnt. As is suggested, you really have to believe in what you are doing in order to act instinctively – in a way which is not premeditated or over-deterministic. In this sense you cannot simply follow a ‘plan’ to be altruistic as this is in its essence self-defeating. It is, however, possible to develop one’s “character” or “identity”, so that we do begin to notice when things are wrong or unjust and we really do feel compelled to act to change them. This is done through periods of self-reflection but also, more importantly, by acquiring knowledge.

Oliver Ressler uses his research-based practice as a way of not only acquiring knowledge for himself, but of disseminating it to others – via video, installation and public realm contexts. His 2008 film What Would It Mean To Win? in collaboration with Zanny Begg focuses on the counter-globalisation protests at the G8 Summit in Heiligendamm in Germany in 2007. The documentary sections of which probe members of resistance movements to consider just what form society might take if they were to ‘win’ what they have been fighting for. His creation of a bank of knowledge about social alternatives is extended in Alternative Economics, Alternative Societies – a documentary, installation and billboard project which presents ideas and proposals for alternative economic and societal models, which all use the rejection of the system of capital as a starting point (Ressler 2007). The research from this project was published as a book in 2007.

Ressler’s book can be seen as a companion to that of art collective Superflex who in 2006 initiated and published Self-organisation / Counter-economic Strategies. As a “toolbox of ideas”, the book puts forward a series of proposals for self-organised models of social and economic systems that also aim to offer an alternative to capitalism (Bradley et al. 2006). Both books aim to spark debate about the negative effects of our current social order and (as Point 2. suggests) ‘to revivify the belief that ‘an alternative’ is possible’.

What is interesting is that the more we learn about the connections between capitalism and environmental catastrophe – the more self-reflection we undertake – the more ‘responsibility’ we inherit. In his famous essay exploring the moral differences between active and passive action Killing and Starving to Death, James Rachels illuminates this notion:

“There is a curious sense, then, in which moral reflection can transform decent people into indecent ones: for if a person thinks things through and realises that he is, morally speaking [in the wrong]… his continued indifference is more blameworthy than before.” (Rachels 2006, p.73)

And so the self-reflexive artist enters into a spiral. The more knowledge that they research and acquire – the more their conscience is likely to compel them to act. The question then becomes whether art is the most efficient way of effecting real change.

According to Artur Zmijewski, his recent work Democracies – a series of documentary clips depicting different protest movements from around the world – is not art. “Art”, according to Zmijewski, “is too weak to present political demand” (Prince 2009, p.6). Artists have in the past reached a similar conclusion – turning to existing political systems as a more direct means of effecting change. In 1980 Joseph Beuys was instrumental in setting up the Green Party in Germany, running as its candidate for the European Parliament, and, in 1988 Maria Thereza Alves co-founded the Green Party in Brazil. In a recent lecture Alves points out that it becomes the role of the artist to “judge in each situation whether art or politics provides a better solution” (Alves 2010).

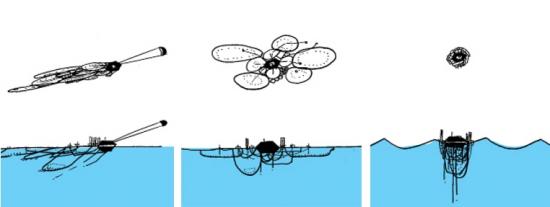

As well as proposing theoretical solutions in book form, Superflex have also attempted to find practical solutions to real life problems in Africa. Although falling under the umbrella of their artistic practice, these projects seem more akin to the sort of thing you might expect to see being pioneered by a charity or a development agency. In 1996-7 they worked with engineers to develop the Supergas system, which is capable of turning compostable waste in the form of human / animal dung into “sufficient gas for the cooking and lighting needs of an African family”, thereby allowing them to “achieve self-sufficiency in energy” (Superflex 1997). The realisation of the Supergas system seems to epitomise the marriage between creative thinking and functionality which Araeen calls for by presenting the example of the desalination plant. What is interesting about this project, and indeed Beuys’ and Alves’ involvement in Green politics, is how it shifts our perception of the role of the artist when viewed as an important component part of a wider practice…

It has been suggested that the most successful campaigning bodies, such as Greenpeace, function “through multi-pronged channels of official, semi-official and illicit activity to negotiate specific ends” (Perry 2010, p.8). They operate under several different ‘hats’ – as a registered charity for raising funds (sometimes even stooping so low as to employ the cynical marketing strategies of the ‘charity-mugger’ on the street) and, at once, as a band of renegade activists aboard the Rainbow Warrior causing real disruption to cruel and exploitative practices and playing tactical media games. They demonstrate a “positive disengagement” (Fisher 2006) from the mainstream, coupled with a savvy co-option of the system, where it clearly presents itself as a more productive solution.

It is possible that the new model for a ‘reconciled artistic practice’ could take a similar form, where the artist (or preferably the collective of artists) balances a variety of activities across different fields. Described as “a group of freelance artist-designer-activists committed to social and economic change” (Myers 2007), Superflex do not ‘abandon’ the art world altogether and, in addition to the projects described above, they continue to work on commissions for its major institutions. For example, in 2009 they made a series of short films The Financial Crisis (Session I-V) for the art market’s number one annual trade fair – Frieze. Like the Lab of ii and following in a long lineage of institutional critique, Superflex appear to understand the benefits of being able to use the system by infiltrating it, criticising and beginning to change it from within.

In now seems evident that our success at adapting to this multi-pronged mode of operation, which straddles real political action, activism and art world insider jobs, depends on our flexibility in approaching different tasks – our ability to wear these different ‘hats’ with conviction and our adeptness at switching between roles. So here it becomes possible to identify the second of the characteristics of neoliberalism which we might aim to salvage. For it is “the very hallmarks of management in a post-Fordist, Control society” – our ‘flexibility’, ‘nomadism’ and ‘spontaneity'” (Fisher 2009, p.28) which we must now begin utilise, as well as our ability to cope with and adapt to change. Both very useful skills to have as the temperatures begin to rise and the food stocks begin to run low.

The final characteristic particular to the career-minded artist, which we must aim to reconfigure as central to our new roles in the twenty-first century, is our work-ethic, which results from our comparatively high levels of intrinsic motivation (Abbing 2002, p.82). The acceleration of work rates is something which has developed across the board under neoliberalism to the extent that we are now “bound” to our work in an “anxious embrace”…

“Managers, scientists, lobbyists, researchers, programmers, developers, consultants and engineers, literally never stop working. Even their sex lives serve to augment productivity.” (The Invisible Committee 2009, p.47)

However, it is the artist’s ability and willingness to work twenty-four-seven often in situations completely removed from wage-labour relations, that makes us ‘exceptional’ (Abbing 2002) and offers the potential, even, to act as a paradigm for a general approach to work in a world beyond capital. For it is this position of “radical autonomy” which presents the opportunity for “real education of our socialised senses and human potentials that releases development in all directions” (Ray 2009, p.546). We continue, over the course of our lives, to relentlessly acquire knowledge, self-reflect and develop, adapt, evolve and act – not for money, but because something inside us – something inherent in our ‘character’ – compels us to. If we could only succeed in “freeing” a small fraction of this exceptional motivation “from the self-destructive narcissist ego” (Araeen 2009, p.683) and releasing it in a more selfless and functional direction, it could still be a hugely positive force for change.

Following Aristotle’s classic assertion that moral excellence is found in a person’s rational capacity to choose the mean between extremes (Mautner 2005, p.43), the introduction to the Cambridge reader on Altruism, in which Badhwar’s essay is published, suggests that:

“The most challenging task of a moral theory is to strike a balance between the weight we give to our own interest and the weight we give to those of others. A theory that directs us to give too much to others is as deficient as one that directs us to give too little.” (Paul et al. 1993, p.ix)

And, so it seems that ‘a reconciled practice’ will also, to a certain extent, be about compromise. It will be about attempting to ‘strike a balance’ between the time we invest in each of the various facets of our activity – direct political action or more conventional art world activity – and about how we best use our judgement as to when to focus on one thing over another. If we can achieve this equilibrium in our ‘multi-pronged approach’ to practice, and indeed in our lives in general, then this is perhaps also where we will find our “private satisfaction” (Abbing 2002, p.82): our happiness.

In a recent interview Ranciere reminds us “that there are certain situations where only reality can be taken into account – there is no room for fiction” (Charlesworth 2010, p.75). What this suggests is that perhaps the balance between the ‘selfish’ and ‘selfless’ activity which artists undertake will only really begin to shift when we are directly confronted with the realities of climate change. As James Lovelock suggests it may well take until the point of real global disaster – such as an event on the scale of the Pine Island glacier breaking off into the ocean causing tsunamis and an immediate and permanent sea rise of two metres (Hickman 2010, p.12) – until we are, through absolute necessity, able to totally reconfigure our motivations. Perhaps only when we do come face-to-face with this “worst kind of encounter with reality” (Kingsnorth & Hine 2009, p.11) will we, as artists, be able to assume our fully functional role in society.

When Franny Armstrong, founder of the 10:10 Campaign, says “if you’re not fighting climate change or improving the world, then you’re wasting your life” (Armstrong 2009a, p.8), she is essentially reinforcing the ‘wager’ set out in our ‘plan of action’. However the future pans out, do you really want to look back on this pivotal moment in the history of our species and say ‘I did nothing’, ‘I did not make a stand’, or do you want to be able to say the opposite and to retain what should be our most commanding of all human motivations – our integrity.

——-

Abbing, H., 2002. Why Are Artists Poor?: The Exceptional Economy of the Arts, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Alves, M.T., 2010. The Friday Event. The Glasgow School of Art. Available at: www.gsaevents.com/fridayevent/alves [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Araeen, R., 2009. Ecoaesthetics: A Manifesto for the Twenty-First Century. Third Text, 23(5), 679-84.

Araeen, R. & Appignanesi, R., 2009. Art: A Vision of the Future. Third Text, 23(5), 499-502.

Armstrong, F., 2009a. Franny Armstrong: If you’re not fighting climate change or improving the world, then you’re wasting your life. The Guardian, 8.

Armstrong, F., 2009b. What is 10:10? 10:10 Campaign website. Available at: www.1010uk.org/1010/what_is_1010/arms [Accessed April 10, 2010].

AVOID, 2010. Will the Copenhagen Accord avoid more than 2C of global warming? AVOID website. Available at: ensembles-eu.metoffice.com/avoid [Accessed May 3, 2010].

Badhwar, N.K., 1993. Altruism Versus Self-Interest: Sometimes a False Dichotomy. In Altruism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 90-117.

Bey, H., 1994. Immediatism, Oakland, California: AK Press.

Blackburn, S., 2009. Do we need a new morality for the 21st century? The Guardian Culture Podcast. Available at: www.guardian.co.uk/culture/audio/2009/nov/02/cambridge-festival-of-ideas.

Bradley, W. et al. eds., 2006. Self-organisation / Counter-economic Strategies, New York: Sternberg Press.

Brown, W., 2009. What will be the legacy of recession? The Guardian Culture Podcast. Available at: www.guardian.co.uk/culture/audio/2009/oct/26/culture-cambridge-festival-ideas.

Cameron, D., 2009. The Age of Austerity. The Conservative Party website. Available at: www.conservatives.com/News/Speeches/2009/04/The_age_of_austerity_speech_to_the_

2009_Spring_Forum.aspx [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Charlesworth, J.J., 2010. Jacques Rancière Interview. Art Review, (40), 72-5.

CIRCA, 2003. About the Army. Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army website. Available at: www.clownarmy.org/about/about.html [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Crisp, Q., 1996. The Naked Civil Servant, London: Flamingo.

Curtis, A., 2002. The Century of the Self, BBC 4.

Deleuze, G., 1990. Society of Control. L’Autre Journal, (1). Available at: www.nadir.org/nadir/archiv/netzkritik/societyofcontrol.html.

Fisher, M., 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, Ropley, Hampshire: 0 Books.

Fisher, M., 2006. Reflexive Impotence. k-punk blog. Available at: k-punk.abstractdynamics.org/archives/007656.html [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Fowkes, M. & Fowkes, R., 2009. Planetary Forecast: The Roots of Sustainability in the Radical Art of the 1970s. Third Text, 23(5), 669-674.

Guattari, F., 2006. Chaosmosis: An Ethico Aesthetic Paradigm. In Participation. London / Cambridge, Mass.: Whitechapel / MIT Press.

Guyer, P., 2004. Immanuel Kant. In E. Craig, ed. Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. London: Routledge.

Hajek, A., 2008. Pascal’s Wager. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at: plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/pascal-wager [Accessed May 3, 2010].

Harvey, D., 2007. A Brief History of Neoliberalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harvie, D. et al. eds., 2005. Shut Them Down!, Leeds / New York: Dissent! / Autonomedia.

Hickman, L., 2010. James Lovelock: Fudging data is a sin against science. The Guardian, 10-12.

Hillcoat, J., 2009. The Road, Dimension Films.

IPCC, 2001. Special Report on Emissions Scenarios. GRID-Arendal website. Available at: www.grida.no/publications/other/ipcc%5Fsr/?src=/climate/ipcc/emission [Accessed May 3, 2010].

Jordan, J., 2010. On refusing to pretend to do politics in a museum. Art Monthly, (334), 35.

Kerr, A., 2010. Goldsmiths: But is it Art?, BBC 4.

Kingsnorth, P. & Hine, D., 2009. Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto. Available at: www.dark-mountain.net/about-2/the-manifesto.

Lab of ii, 2005. About Us. The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination website. Available at: www.labofii.net/about [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Mamudi, S., 2008. Lehman folds with record $613 billion debt. MarketWatch website. Available at: www.marketwatch.com/story/lehman-folds-with-record-613-billion-debt?siteid=rss [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Mautner, T., 2005. Aristotle. In The Penguin Dictionary of Philosophy. London / New York: Penguin, pp. 40-4.

Mouffe, C., 2007. Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces. Art & Research, 1(2). Available at: www.artandresearch.org.uk/v1n2/mouffe.html [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Myers, J., 2007. Superflex. Frieze Magazine, (106). Available at: www.frieze.com/issue/review/superflex [Accessed May 9, 2010].

Paul, E.F., Miller, F.D. & Paul, J. eds., 1993. Altruism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Perry, C., 2010. Art v the Law. Art Monthly, (333), 5-8.

Priddle, A., 2009. School of Saatchi, BBC 2.

Prince, M., 2009. Art & Politics. Art Monthly, (330), 5-8.

Prince, M., 2010. Remakes. Art Monthly, (335), 9-12.

Rachels, J., 2006. Killing and Starving to Death. In The Legacy of Socrates: Essays in Moral Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 60-82.

Ranciere, J., 2007. Hatred of Democracy, London: Verso.

Ray, G., 2009. Antinomies of Autonomism: On Art, Instrumentality and Radical Struggle. Third Text, 23(5), 537-46.

Ressler, O., 2007. Alternative Economics, Alternative Societies. Oliver Ressler website. Available at: www.ressler.at/alternative_economics [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Sharp, C., 2010. Career Suicide. Art Review, (40), 52-4.

Strawson, P.F., 2008. Social Morality and Individual Ideal. In Freedom and Resentment and Other Essays. London / New York: Routledge, pp. 29-49.

Superflex, 1997. Supergas. Superflex website. Available at: superflex.net/tools/supergas [Accessed May 5, 2010].

Thatcher, J., 2009. Crunch Time. Art Monthly, (332), 5-8.

Thatcher, M., Margaret Thatcher Quotes. About.com website. Available at: womenshistory.about.com/od/quotes/a/m_thatcher.htm [Accessed May 2, 2010].

The Invisible Committee, 2009. The Coming Insurrection, Los Angeles / Cambridge, Mass.: Semiotext(e).

Triandis, H., 1995. Individualism and Collectivism, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Vonnegut, K., 2003. Knowing What’s Nice. In These Times. Available at: www.inthesetimes.com/article/knowing_whats_nice [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Walker, J., 2002. Left Shift: Radical Art in 1970s Britain, London / New York: I.B. Tauris.

Williams, E.C., 2009. Putting the punk back in salvage (where it was not to begin with). Socialism and/or Barbarism blog. Available at: socialismandorbarbarism.blogspot.com/2009/08/putting-punk-back-in-salvage-where-it.html [Accessed May 4, 2010].

Zizek, S., 2009a. First As Tragedy, Then As Farce, London: Verso.

Zizek, S., 2009b. In Defense of Lost Causes, London: Verso.

Jaron Lanier

You Are Not A Gadget

2010

Allen Lane

ISBN 1846143411

Jaron Lanier’s book “You Are Not A Gadget” is a timely polemic, a cry of the soul in an increasingly soulless Web 2.0 world. I found reading it a frustrating and inspiring experience. For every time I wanted to throw the book at the wall in exasperation there was a time where Lanier spoke to a part of me that the cultural transition from 90s cyberpunk to 2010s cyberpreppy had optimised out.

Lanier is asking the right questions. What happens to our conception of what it means to be human when the way we represent our humanity is reduced to snippets of media on (micro-)blogs and social networking sites? How can we support a middle class of independent artists when the technology and economics of the Internet makes money directly only for the vectorialist media barons of Web 2.0? Will the technologically enabled troll class become a political threat akin to historical fascism?

These are questions that need asking, and Lanier asks them in an intelligent and open way. This is all the more impressive given his background as a champion of cyberculture. Lanier is not fearful or dismissive of the changes that the technology he championed has wrought. He is looking them in the eye and challenging their new proponents to explain the gap between their claims and their reality.

The problem is that Lanier’s answers crash and burn from a lack of detailed knowledge of non-cyber culture. He contrasts the managerialism and capitalism that he mis-identifies as materialism with a naive and easily exploited mystificatory spirituality. He accepts unquestioningly the music recording industry’s claim that the Internet has destroyed the economic and cultural value of music. And his characterisation of commons-based peer production as digital Maoism is wide of the mark.

To address just one of his examples; the cultural smog of the contemporary Internet follows the exhaustion of mass culture, it has not produced it. Napster is not to blame for the X Factor. The Beatles, generally regarded as a cultural highpoint of mass culture, were a reactionary throwback to earlier rock and roll tropes and were identified as such by Cliff Richard at the time. The well of mid-20th century black American music was returned to in the 1960s, 1970s 1980s and 1990s and was dry by the era of the parochial third-order nostalgia of Britpop. Crucially, Britpop pre-dates Napster and mass adoption of the MP3 file format. Lanier’s adopted narrative doesn’t add up.

But I come to praise Lanier, not to bury him in data. His is an ambitious critique, an important challenge to deeply ingrained cybercultural beliefs. We should all be so brave as to face the consequences of what we believe in so directly. And his final conclusions, not those of a disappointed cyber-hippy who should have been careful what he wished for but of someone who has kept faith in the potential of technology for us to realise ourselves, are as inspirational as they are accusatory.

You can google any number of blow-by-blow disagreements with Lanier’s thesis. And his own FAQ on the book is in many ways more convincing than the book itself. But if you have any interest in contemporary culture as it is mediated by technology you owe it to yourself to find your own points of difference and agreement with Lanier and to look beyond that to the spirit of what he is saying.

Which is that we should not be reifying and reducing our selves and our experiences into packets of data that the social robber barons of Web 2.0 can sell to marketing companies and government agencies. We should be using virtual reality and the other affordances of information technology to expand our consciousness and to grow as socialised individuals.

Web 2.0 can be oppressively straight and conformist. It doesn’t have to be like this. Don’t dismiss Lanier’s ambition to create a virtual reality system that could let him experience being an octopus. Wonder what it would be like to try it yourself, and how you would explain it to your friends.

Not the entries on your Facebook Friends list, your actual friends…

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Article by Rosa Menkman

Based on an interview with the Critical Glitch Artware Category organizers and contenders of Blockparty and Notacon 2010: jonCates, James Connolly, Eric Oja Pellegrino, Jon.Satrom, Nick Briz, Jake Elliott, Mark Beasley, Tamas kemenczy and Melissa Barron.

From April 15-18th, the Critical Glitch Artware Category (CGAC) celebrated its fourth edition within the Blockparty demoparty and this time also as part of the art and technology conference Notacon.

The program of the CGAC consisted of a screening curated by Nick Briz, performances by Jon Satrom, James Connolly & Eric Pellegrino, and DJ sets by the BAD NEW FUTURE CREW. There were also a couple of artist presentations and the official presentation of a selection of the (115!) winners within the Blockparty official prize ceremony.

The fact that CGAC was coupled with a demoscene event is somewhat extraordinary. It is true that both the demoscene and CGAC or ‘glitchscene(s)’ focus on pushing boundaries of hardware and software, but that said, I (as an occasional contender within both scenes) could not think about two more parallel, yet conflicting worlds. The demoscene could be described as a ‘polymere’ culture (solid, low entropic and unmixable), whereas CGAC is more like an highly entropic gas-culture, moving fast and chaotically changing from form to form. When the two come together, it is like a cultural representation of a chemical emulsion; due to their different configuration-entropy, they just won’t (easily) mix.

But all substances are affected (oxidized) by the hands of time; there is always (a minimal) consequence at the margin. And this was not the first time these two cultures were exposed to each other either; Criticalartware had been present at Blockparty since 2007. Moreover, a culture can of course not be as strictly delineated as a chemical compound; it was thus clear that this year the two were reacting to each other.

While over the last couple of years the demoscene has been described in books, articles and thesis’, this particular kind of ‘fringe provocation’ is not what these researchers seem to focus on; they (exceptions apart) concentrate on the exclusivity of the scene and its basic or specific characteristics. The ‘assembly’ of these two cultures during Blockparty could therefore not only serve as a very special testing moment, but also widen and (re)contextualize the scope of the normally independent researches of these cultures. So what happened when the compounds of the chemicals were ‘mixed’ and what new insights do we get from this challenging alliance (if there is such a thing)?

The demoscene is often described as a bounded, delimitated and relatively conservative culture. Its artifacts are dispersed within well-defined, rarely challenged categories (for the contenders, there is the ‘wild card’ category). Moreover, the scene is a meritocracy – while the contenders (that refer to themselves with handles or pseudonyms) within the scene have roles and work in groups, the elite is ‘chosen’ by its aptitude.

The demoscene also serves a very specific aesthetics, as enumerated by Antti Silvast and Markku Reunanen this week on Rhizome (synced music and visuals, scrolling texts, 3d objects reflections, shiny materials, effects that move towards the viewer – tunnels and zooming – overlays of images and text, photo realistic drawing and adoption of popular culture are the norm). In the same article Silvast and Reunanen declare that: ‘Interestingly, even though we’re talking about technologically proficient young people, the demosceners are not among the first adopters of new platforms, as illustrated by numerous heated diskmag and online discussions. At first there is usually strong opposition against new platforms. One of the most popular arguments is that better computers make it too easy for anybody to create audiovisually impressive productions. Despite the first reactions, the demoscene eventually follows the mainstream of computing and adopts its ways after a transitional period of years.'[1]

More about this can be read at Rhizome’s week long coverage of the demoscene. Silvast and Reunanen’s statement might be most interesting when we move along to see what happened during the meeting of the two scenes.

Co-founded by jonCates, Blithe Riley, Jon Satrom, Ben Syverson and Christian Ryan in 2002, Criticalartware is a radically inclusive group that started as a media art history research and development lab. Since 2002 the group has shifted and transitioned. Criticalartware’s formation was deeply influenced by the Radical Software platform (publications and projects). Since then it has been an open platform for critical thinking about the use of technology in various cultures. Criticalartware applies media art histories to current technologies via Dirty New Media or digitalPunk approaches. Through tactics of interleaving and hyper threading it permeates into cultural categories of Software Studies, Glitch Art, Noise and New Media Art.

During the first phase of Criticalartware (from 2002 – 2007), the group was a collaborative of artist-programmers/hackers. It also functioned as a media art histories research and development lab. In this form, Criticalartware had become an internationally recognized and reviewed project and platform.

When this phase ended in 2007, jonCates, Tamas Kemenczy and Jake Elliott were the remaining active members of Criticalartware. During this time, Elliott and Kemenczy wanted to take the project in a new direction; into the demoscene. This direction has ultimately defined the second phase of Criticalartware; an artware demo crew, making work for and appearing annually at the Blockparty event and Notacon conference in Cleveland.

2010 marked the next important transition for the Criticalartware crew, when it started using the phrase ‘Critical Glitch Artware’- Category. Criticalartware now not only organizes itself around the demoscene but also around the concept of the glitch. While a glitch (not to be confused with glitch art) appears as an accident or the result of misencoding between different actors, CA’s Glitch-art category exploits this possibility in an metaphorical way. Criticalartware is now foregrounding these glitch art works (with an emphasis on the procedural/software works) that have been on a ‘pivotal axis’ of the crew for a long time.

CGA, just like the demoscene, can be described as an open (plat)form for artistic activity/culture/way of life/counter culture/multimedia hacker culture and (unfortunately a bit of ) a gendered community. CA are about pointing out ideas or concepts within popular culture and incorporating (standardizing) these as machines or programs in a reflexive and critical self-aware manner.

CA can also be described as an investigating of standard structures and systems. They are often amongst early adopters of technology, in which they (politically) challenge and subvert categories, genres, interfaces and expectations. But the CGA – artists do not feel stuck in a particular technology, which makes it aesthetically, at least at first sight hard to pinpoint a common denominator.

There is not a real organization within this scene. The artists and theorists are scattered over the world, connected in fluid/loosely tied networks dispersed over many different platforms (Flickr, Vimeo, Yahoo groups, Youtube, NING, Blogger and Delicious).

Because of its bounded, intricate conservative qualities, the demoscene has been an easy target for outsiders to play ‘popular’ ironic pranks on, to misunderstand or misrepresent. A growing interest for the demoscene by outsiders has compelled jonCates and the Criticalartware crew to articulate their position towards the demoscene more extensively. In an interview with me, jonCates articulates Criticalartware’s points and contrasts these with problematic representations of the demoscene within two works by the BEIGE Collective (that in 2002 existed along side the Criticalartware crew in Chicago).

When the BEIGE collective went to the HOPE (Hackers on Planet Earth) Conference in 2002 they made a project called: TEMP IS #173083.844NUTS ON YOUR NECK or Hacker Fashion: A Photo Essay by Paul B.Davis + Cory Arcangel.

jonCates writes to me that ‘this problematic project characterizes or epitomizes a kind of artists as interlopers positionality that i + Criticalartware as a crew has always attempted to complicate. we do not want or understand ourselves as seeking out an ironic or sarcastically oppositional position in relation to the contexts that we choose to work in. we have not set out to ridicule the demoscene or otherwise make ridiculous our relations to the demoscene. in contrast, we set out to operate within a specific demoscene through multi-valiant forms of criticality, playfullness, enthusiasm, respect, interest, admiration, etc… this has also been in efforts to connect this specific demoscene to our experimental Noise & New Media Art scenes or what you Rosa referred to earlier as glitchscene…’

Another point of contention for jonCates is the Low Level All-Stars project by BEIGE (in this case, Cory Arcangel) + Radical Software Group (Alexander R. Galloway). this work is described as ‘Video Graffiti from the Commodore 64 Computer’ (2003) by Electronic Arts Intermix who sells/distributes this work as a video in the context of Video Art.

Low Level All-Stars has been shown at Deitch Projects in NYC in 2005 and circulated in the contemporary art world. jonCates writes to me saying the work seeks ‘to isolate + thereby establish cultural values for this ‘quasi-anthropological’ view of demos as found object + functioning as a tasteful ‘testament to a lost subculture.’ It is now being offered online as an educational purchase for $35 dollars.

However, as jonCates and Criticalartware work in the demoscene demonstrates, the demoscene subculture is not lost, nor over. jonCates moves on by writing that ‘the demoscene is a vibrant whirld wit a dynamic set of pasts + presents. this is another of which many (art) whirlds are possible. we seek to make those whirlds known to each others + ourselves out of respect, curiosity, investment, inclusiveness, criticality, playfullness, etc…’

The Criticalartware crew has been taking part in Blockparty since 2007, when it won the last place in a demo competition and was disqualified. One year later, in 2008, through a number of efforts (including Jake Elliott’s presentation Dirty New Media: Art, Activism and Computer Counter Cultures at HOPE, the Hackers on Planet Earth conference in NYC in 2008). CA was able to mobilize and manifest the concept of the Artware category at Blockparty, a category which Blockparty itself retroactively recognized CA for winning.

In the same year (2009) CA organized a talk at Blockparty in which they revealed the “secret source codes” of the tool they used to develop the winning artware of the year before.

By 2010 CA wanted to expand the concept of Artware within the demoscene, which lead to the development of the ‘Critical Glitch Artware Category’ event. Within the CGAC Compo there where 115 subcategory winners, which showed some kind of glitch-critique towards systematic categorization of Artware. Jason Scott (the organizer of Blockparty) personally invited CGAC to pick 3 winners and present their wares at the official Blockparty prize ceremony. Besides these three winners, CGACs efforts got extra credits when Jon Satrom’s Velocanim_RBW also won the Wild card category compo.

Therefore, not only did CA intentionally open up the Blockparty event to outsiders of the demoscene, it also provided a place for new media art and the glitchscene within the demoscene and got Blockparty to accept and invite the CA within their program. Thus, the outsiders (CA) moved towards the inside of the event, while the insiders got introduced to what happens outside of the demoscene (event), which led to conversations and insights into for instance bug collecting, curating and coding.

The Critical Glitch Artware Category has been accepted by, at least, the fringe of Blockparty 2010. Even though the category itself is not (yet) visible on the website, Satrom’s winning work Velocanim_RBW is. Moreover, CGAC was part of the official prize ceremony, streamed live on Ustream, the live Blockparty internet television stream. So how does CGAC redefine or reorganize the fringe between them and the demoscene and how does the demoscene redefine and reorganize the structure of CGAC?

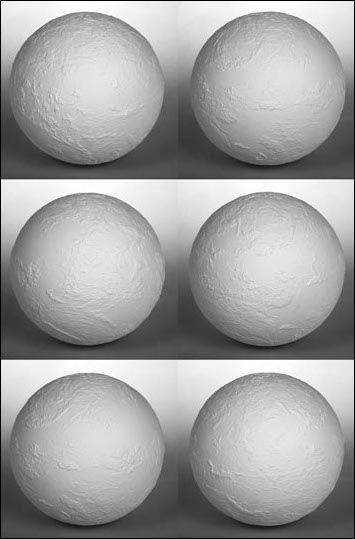

For now, I think crystallized research into the aesthetics of the demoscene can also help describe the aesthetics within CGAC. Custom elements like rasters, grids, blocks, points, vectors, discoloration, fragmentation (or linearity), complexity and interlacing are all visually aesthetic results of formal file structures. However, the aesthetics of CGA do not limit themselves, nor should they be demarcated by just these formal characteristics of the exploited media technology.

Reading more about the demoscene aesthetics, I ran into a text written by Viznut, a theorist within the demoscene (who also wrote about ‘thinking outside of the box within the demoscene’). He separates two aesthetic practices within the scene: optimalism (an ‘oldschool’ attitude) which aims at pushing the boundaries in order to fit in ‘as much beauty as possible’ in as little code necessary, and reductivism (or ‘newschool’ attitude), which “idealizes the low complexity itself as a source of beauty.'[2]

He writes that “The reductivist approach does not lead to a similar pushing of boundaries as optimalism, and in many cases, strict boundaries aren’t even introduced. Regardless, a kind of pushing is possible — by exploring ever-simpler structures and their expressive power — but most reductivists don’t seem to be interested in this aspect”.

A slightly similar construction could be used for aesthetics within Glitch Art. Within the realm of glitch art we can separate works that (similar to optimalism) aim at pushing boundaries (not in terms of minimal quantity of code, but as a subversive, political way, or what I call Critical Media Aesthetics; aesthetics that criticize and bring the medium in a critical state) and minimalism (glitch works that just focus on the -low- complexity itself – that use supervisual aesthetics as a source of beauty). The latter approach seems to end in designed imperfections and the (popularized) use of glitch as a commodity or filter.[3]

Of course these two oppositions exist in reality on a more sliding scale. Debatebly and over simplified I would like to propose this scale as the Jodi – Mille Plateaux (old version) – Beflix – Alva Noto – Glitch Mob – Kanye West/Americas Next Top Model Credits continuum; A continuum that moves from procedural/conceptual glitch art following a critical media aesthetics to the aesthetics of designed or filter based imperfections.

This kind of continuum forces us to ask questions about the relationships between various formalisms, conceptual process-based approaches, dematerializations and materialist approaches, Software Studies, Glitch Studies and Criticalartware, that could also be of interest or help to future research into the demoscene. When I ask jonCates what other questions CGAC brings to the surface, he answers:

“when i asked Satrom to participate in the CRITICAL GLITCH ARTWARE CATEGORY event + explained the concept that Jake + i had developed to him he was immediately interested in talking about it as form of hacking a hacker conference, by creating a backdoor into the conference/demoscene/party/event. im also excited about this way of discussion the event + our reasonings + intentions, but i want to underscore that this effort is also undertaken out of respect for everyone involved, those from the demoscene, glitchscenes, hackers, computer enthusiasts, experimental New Media Artists, archivists, those who are working to preserve computer culture, Noise Artists + Musicians, etc… so while this may be a kind cultural hack/crack it is not done maliciously. we are playful in our approach (i.e. the pranksterism that Nick refers) but we are not merely court jesters in the kingdom of BLOCKPARTY. we have now, as of 2010, achieved complete integration into the event without ever asking for permission. perhaps that is digitalPunk. + mayhaps that is a reason for making so many categories +/or so many WINNERS! 🙂

…also, opening the category as we did (with a call for works [although under a very short deadline], an invitational in the form of spam-styled personal/New Media Art whirlds contacts + mass promotional email announcements of WINNERS! (in the style of the largest-scale international New Media Art festivals such as Ars Electronica, transmediale, etc…) opens a set of questions about inclusion.

…whois included? who self-selects? whois in glitchscenes? are Glitch Artists in the demoscene? etc… this opening also renders a view on a possible whirld, which was an important part of my intent in my selection of those who won the invitational aspect of the CRITICAL GLITCH ARTWARE CATEGORY. by drawing together (virtually, online + in person) these ppl, we render a whirld in which an international glitchscene exists, momentarily inside a demoscene, a specific timeplace + context.”

Lately the demoscene seems to get more and more attention from “outsiders”. Not only ‘pranksters’, artists and designers who are interested in an “old skool” aesthetic, but also researchers and developers that genuinely feel a connection or interest to a demoscene culture (I use ‘a’ because I think there still should be a debate about if there might be different demoscene cultures).

This development makes it possible to research a subculture normally described as ‘closed/bounded’ and to see where and how these different cultures are delineated. The tension between Blockparty/Notacon and Critical Glitch Artware Category is one that takes place on a fringe. They do not come together, but while it would be easy to just think that probably the CGAC sceners were just ignored (and maybe flamed) by the demosceners half of the time, some more interesting and important developments and insights also took place.

The CGAC-crew has over the years shown itself to be volatile, critical and unexpected, but it has also shown respect to the traditions of the demoscene and in doing so, earned a place within this culture (at least at Blockparty). This gave the CGAC-democrew not only the opportunity to put a foot in the backdoor of a normally closed system, but also to give some more insights into what they expose best: they confronted the contenders with their (self-imposed) structures and introduced them to (yet to be understood and accepted) new possibilities.

So what happens when a polymere is confronted with entropic gasses? I think the chemical compounds get the opportunity to measure the entropic elasticity of their dogmatic chains.

Also read:

Carlsson, Anders. Passionately fucking the scene: Skrju.

http://chipflip.wordpress.com/2010/05/20/passionately-fucking-the-scene-skrju/ Chipflip. May 20th, 2010.

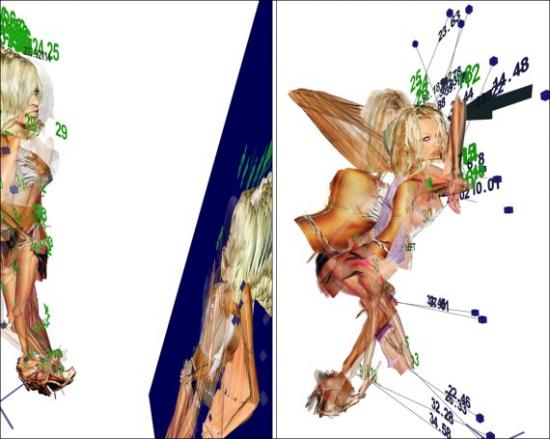

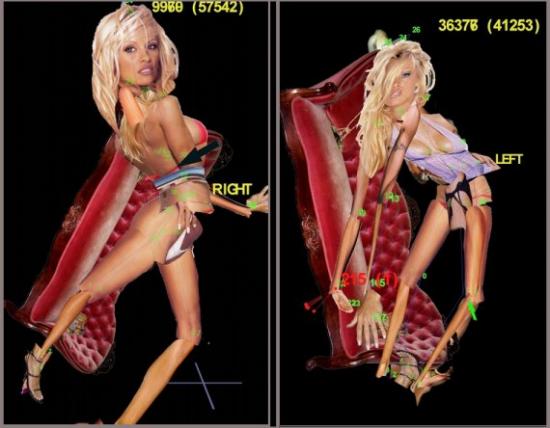

Patrick Lichty, renowned conceptually-based artist, writer, curator and activist. He has exhibited internationally since 1990. Featured image: taken by Anne Helmond.

Introduction.

Patrick Lichty is an individual who seems to be like a non-stop engine. A hungry human being, engulfed in a prolific journey of constant exploration, whether it be making artworks, writing, activism, curating, collaborating, researching or teaching; he’s deeply involved and engaged in media arts culture. Since 1990, he has pursued art and writing that explores how we relate to one another through technology and how we relate to it. This includes art, media, and computer technology. “Media are one of the “glues” of civilization, and this glue is as fundamental in representing all aspects of society, culture, and interpersonal relations. I explore this through critical theory, conceptual New Media art, and performance/social intervention.”

Lichty also works in almost all forms of Digital 3D – Animation, VR, Fabrication, Physical Computing. Translating the work for display through video, animation, live installation, electronics, virtual reality, physical computing, robotics, digital fabrication and imaging. As well as realising virtual works into traditional forms such as plates for print, paintings, expanding the focus of his work in a broader context.

Lichty’s work, concepts and practice do not rest in one place, it crosses over into many areas of creative production. By getting his hands dirty with the medium of technology, with its relational aspects. The spirit of the work goes beyond singular catch phrases and one-liners, adding complexity and value which only media art and its ever widening scope can demonstrate.

It’s big art with big ideas, interwoven with micro levels of human emotion, asking questions about life and more. This two part interview aims to clarify some questions I have been wanting to ask Patrick Lichty for a while now, so hang on and lets see what happens…

Start of Interview:

Marc Garrett: You have been deeply engaged in the creation of net art, networked art, media art and related activities at various levels, whether it has involved you making it, writing about or curating it. What inspired you to choose which is, now unquestionably, one of the most contemporary and expansive forms of creativity, in the first place?

Patrick Lichty: This is a question that has come up repeatedly. “Why did you choose (what is now called) New Media, or the intersection between society, technology, and culture?” It is really a matter of examining my native culture, which has been that of technological culture. I was raised by an artist who gave me my first electronics set at the age of 8, and my first computer by the age of 17, while raising me on a steady diet of science fiction. I was a child of McLuhan; growing up in the electric networks on a diet of very hot media. However, I do also paint, and when I think it’s appropriate, I also do use traditional media. In short, I speak this culture because it’s my native language.

MG: To kick off this interview I thought it would serve our readers well to discuss your work from a perspective of themes. Over the years, exploration through your practice has crossed over into many different disciplines and fields. So lets begin with Psychogeography. To those who are unfamiliar with this practice, the most well defined and serious use of it was in 1955 by Guy Debord: “a whole toy box full of playful, inventive strategies for exploring cities … just about anything that takes pedestrians off their predictable paths and jolts them into a new awareness of the urban landscape.”

“Of all the affairs we participate in, with or without interest, the groping quest for a new way of life is the only thing that remains really exciting. Aesthetic and other disciplines have proved glaringly inadequate in this regard and merit the greatest indifference. We should therefore delineate some provisional terrains of observation, including the observation of certain processes of chance and predictability in the streets.” Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography. Guy Debord

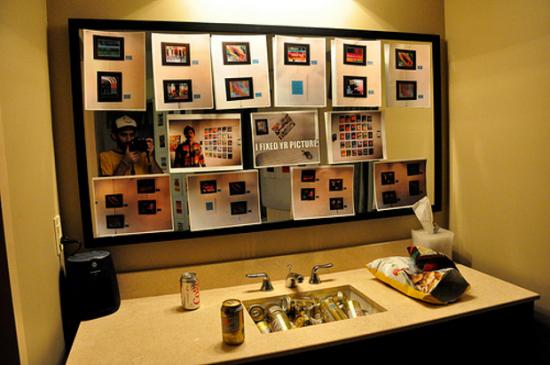

Patrick, one of your projects which springs to mind, is a work called SPRAWL “…an exploration of the suburban American landscape, examining the macrocosmic issues related to suburban expansion by considering the microcosmic issues of the experiences of a bellwether area of the US: Stark County, Ohio. In navigating the landscape you will view over thirty panoramic photographs of sites that are now forever changed by the area’s development as well as interviews on video and historical documents which create a map of the larger social landscape of the surrounding community.”

A complex and involved project. What inspired you to examine the ‘suburban American landscape’ in such a way, and how long did it take to complete?

PL: In talking about Debord’s definition, I’d like to talk about my own interpretation of the idea of Psychogeography. If you consider the word etymologically in contrast with Debord’s meaning, you can say that it should not be limited to the urban landscape, but the relationship of human interaction with any landscape. From this, we move out of the city to any relation between community and space, which is my interest, and I like to term as a practice of ‘land use interpretation’ to borrow Matt Coolidge’s (CLUI) term. All of my work in this range, from SPRAWL to the three projects in varying stages of completion (the Hulett Project, Ghosts of Adak, and SPRAWL 2011) come from a personal observation that expands to a macroscopic discourse through the larger exploration/research of the space.

SPRAWL began as a 3-year personal investigation of my own distress about suburban sprawl in the late 1990’s near my home town, and linking this to the larger national conversation regarding sprawl at the time. For reference, I was born in nearby Akron, Ohio – the subject of Chrissie Hynde and The Pretenders song My City Was Gone, which describes the colonization of an industrial city and its countryside by sprawl and shopping malls, so if SPRAWL has a soundtrack, that would be it. I began SPRAWL in 1998, as a series of panoramic photographs of various sites near my home, with just a vague impression that they were a cohesive body of work. Also, the idea of nostalgia for the pastoral farmland of my younger days seemed far too simple to be satisfying, so I knew there was something to it. So, when the Smithsonian American Art Museum put out a call for works dealing with landscape online, I felt this was a fantastic place to really explore this idea in a larger context. Then they offered me the commission, the project went from a set of 32 panoramas to a hyperdocumentary in about three solid months of production, including travelling back to Ohio from Louisiana, interviewing, doing on-site footage, and performing historical research.

What I think is important about SPRAWL is that it’s ‘sensable research’, in that it managed to manifest the ideas I had about this problem, learning a lot more about community ecology, allowing the articulation of a microcosmic issue in macroscopic terms. In more personal terms, it allowed the development of my question of social issues related to my concern with the understanding that my perspective was only one of many, and from examining a multitude of perspectives, I could learn what the larger issues were, and create a discourse with a larger community.

MG: On your website, for the Ghosts of Adak there is a statement of yours, saying “My father and I have something in common. He was born in 1921 and spent 2-1/2 years in the North Pacific campaign on Adak Island in the Western Aleutian Islands in Alaska. I have heard about it since 1962. So I went there for 10 days. And I found him all over again.”

I also visited another site to find out about the community living there, and on this site called Alaska Tracks. Ned Rozell writes “Adak’s having a tough time, and the community of about 200 people in the mid-Aleutians has been struggling since the Navy pulled about 6,000 people out in 1997. It’s got a feel to it now like the Love Canal area of Niagra Falls had in the 1980’s, like everyone took off and left a few ghosts behind.”

How was your 10 days stay there and what did you learn?

Do you have a clear idea of what this project will become? Also, I noticed that it is part of an artist residency program at Eyebeam R&D Atelier NYC. How do you intend to present this work, in a space, on-line or something else?

PL: That’s a book in itself, and probably will be, which is part of your next question. First, why – My father is nearing 90, and for most of my life, he had gone on about this “place” that he had been for a period of time, and recounting endless stories about it. No place else had that sort of impact on him. Does not talk about Seattle, or San Francisco, or even Chicago (all places he had spent time) like that. I also think that as he is nearing 90, and in that he and I have a very strong bond (actually both Lodge brothers, if you can believe that), and I wanted to know about him in the deepest way possible, and probably in so doing, learn about myself and the site. But then, that fits the process.

The issue with Adak is that it is a tremendously complex place even before I overlay my own emotional architectonic. It was the site of the Northern Pacific campaign of the United States versus Japan during the Second World War, mainly as a diversion from Midway. I had made a deal with the CEO of the facility to exchange the photos for a room, a 40-something Niigata-born guy with petrochemical ties, whose father might have been my father’s enemy, and ideologically, probably was mine, but the personal nature of the trip put that on hold. There were a lot of external and internal conflicts that I had to navigate just to get there.

In short, Adak is currently the remains of the Adak Naval Base and surrounding facilities, which is basically a minor port, petrochemical storage facility, a fishery, and home of the westernmost airport linked to the Continental US, further west than Hawaii. If you rent a car, you rent one of the trucks a local offers, the gas comes from the tank farm, and the ‘hotel’ is a number of duplexes that the residents rent out to visitors. There is a General Store, a cafe at lunchtime, and the old VFW becomes the tavern for dinner, offering an entree or some microwaveable snacks along with a full bar. You sign a disclaimer to absolve the Corporation of any liability if you encounter black mold, fall into an old stairwell, sinkhole, run into an old unexploded shell, etc. I’m speaking a little darkly about this place, but it’s pretty rugged with radically changing weather, frequent earthquakes, and they’re still cleaning up the old artillery ranges.

On the other hand, it’s one of the most amazing places to be. It’s right at the edge of civilization, a volcanic arctic island withn no trees and some of the most amazing wildlife you’ve ever seen – eagles, otters, seals, birds. I can see why my father talked about it so much.

One other thing of note is that while doing the project, I’ve run into all sorts of people who have served, lived, or even been born there, as there was a 6,000-person family facility. On the plane from Minneapolis to Anchorage, I ran into an airline pilot who had just been on a caribou hunt there, and he gave me his GPS information and a lot of pictures. On another trip, I ran into a woman who was born there. It was unbelievable.

What did I learn? I learned about a history that few remember, I learned about my own history and how it affects me. I also learned about the local culture, its history, how Alaskan culture meshes with corporate interests to create a lot of the issues seen in mass media. There isn’t a lot of concern for the area from the locals, and actually the Military was doing a decent job with the cleanup. From a more personal level, I also came to understand that everything is transitory. Art, culture, society, all ephemeral in terms of a mountain. Human beings don’t matter very much to a volcano, but definitely the other way around.

When I was walking on the western (uninhabited) side of the island, I had napped on some tundra and realized I didn’t have my GPS or keys – all my keys. I knew where I slept, and I leave my keys in the car a lot. The worst that could happen was that I would have to walk 5 miles into town in a cold drizzle, get Jimbo the Constable to let me into my car and get the truck in the morning. In the end, I learned that if it isn’t a landmine, it’s not that big of a deal.

“Do you have a clear idea of what this project will become? Also, I noticed that it is part of an artist residency program at Eyebeam R&D Atelier NYC. How do you intend to present this work, in a space, on-line or something else?” This is really tough for me – no, I don’t have a clear idea yet because it’s so hard to frame. It probably needs to be a book, but it isn’t going to be done for a couple more years. I’d like it to be a hyperdocumentary like SPRAWL, but not in the same way. Also, I think it would make a great presentation, and the images are really beautiful. As I mention, it’s terribly hard to frame this project, and I think it should be allowed to be large.

MG: Let’s talk about a piece you created with The Yes Men. As many in the know, know – and of course those who have fallen foul to the Yes Men’s activist-pranks; they are legendary cultural saboteurs. They have impersonated World Trade Organization corporate spokespersons, including Dow Chemical Corporation, Bush administration spokesmen on TV, at various business conferences around the world. In order to demonstrate some of the mechanisms that keep bad people and ideas in power. Focusing attention on the dangers of economic policies that place the rights of capital before the needs of people and the environment. They have more recently become more known to a world-wide audience for The Yes Men, a movie.

Could you inform myself, and readers about the mock industrial video ReBurger and how it came about?

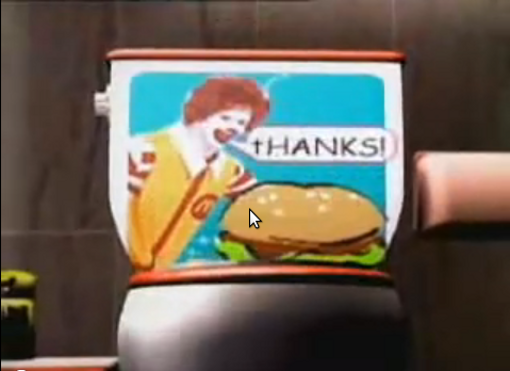

PL: Right. The animation work for The Yes Men is a strange beast, because it came from previous work for a group called RTMark, from which some of us came from to do Yes Men, which is well documented in the two movies. Again, the process for these animations, which I later edit into industrial videos is also an odd one. Usually, when there is an intervention (and I have sometimes appeared in person), Mike will give me a call and say something like, “Hey Patrick, we have this idea for this, for that company…” In this case, it was an idea for recycling feces for the Third World, and not much beyond that general concept. At first, I was thinking of translating dietary fiber to textile manufacture, creating a suit that would look like S**t, but shortly thereafter, brainstorming created the McDonald’s parody. I knew it was going to be shown at Plattburgh College, but beyond that, I didn’t have much context. So, that’s where my process in context with the larger presentation sort of diverges. Mike, Andy and Matt were developing the presentation, and I started in on the simple metaphor of eating shit. In short, I get some basic ideas together, and then produce the clips (not the full industrial video).

Beyond that basic joke, it’s really just exaggeration – the idea of an international infrastrucure for the collection of post-consumer waste, the branded toilet, and the special product names, like “McDung”. The scene that seems to get people is the one of the Ronald McDonald Colostomy Machine (the paste dispenser) as it creates the brown coil of reprocessed waste and then presses it into nice patties. For me, this is the use of pure literal metaphor, and maybe that’s why it works. Maybe it’s because it stands for a corporation that offers “choices” for healthy eating that few choose, and McDonalds willingly contributes to the obesity and illness of billions. In my opinion, ReBurger just tells the truth.

But the reason why people like the video is also a reason why it was a real problem for the sale of the movie at Sundance 2003. Although it was obvious fair use, many in the film industry were also buyers looking at the movie. Mike Bomnano told me that the legal departments of the movie companies were trying to determine the degree of risk of satiring McDonald’s, complete with branding. This was obviously Fair Use under US Copyright, but again, the possibility of an egregious law suit could have happened. In the end, McDonalds decided to ignore the piece, which was great, since I believe it’s one of the stronger Yes Men pieces.

MG: In the UK, June 1997, the infamous McLibel Trial (mcspotlight.org) came to an end. The case was between McDonald’s and a former postman and a gardener from London, Helen Steel and Dave Morris. It ran for two and a half years and became the longest ever English trial. “…Helen and Dave decided that they would stand up to the burger giants in court. They knew each other well from their involvement in community based campaigns in their local North London neighbourhood and felt that although the odds were stacked against them, people would rally round to ensure that McDonald’s wouldn’t succeed in silencing their critics.” The defendants were denied legal aid and their right to a jury, so the whole trial was heard by a single Judge, Mr Justice Bell.

“The verdict was devastating for McDonald’s. The judge ruled that they ‘exploit children’ with their advertising, produce ‘misleading’ advertising, are ‘culpably responsible’ for cruelty to animals, are ‘antipathetic’ to unionisation and pay their workers low wages. But Helen and Dave failed to prove all the points and so the Judge ruled that they HAD libelled McDonald’s and should pay 60,000 pounds damages. They refused and McDonald’s knew better than to pursue it.” Mcspotlight.

I can imagine that McDonald’s were considering their past experience, with cases such as the McLibel Trial. “The legal controversy continued. The McLibel 2 took the British Government to the European Court of Human Rights to defend the public’s right to criticise multinationals, claiming UK libel laws are oppressive and unfair that they were denied a fair trial. The court ruled in favour of Helen and Dave: the case had breached their rights to freedom of expression and a fair trial.”