film, 2008. By Zanny Begg and Oliver Ressler.

What Would It Mean To Win? was filmed on the blockades at the G8 summit in Heiligendamm, Germany in June 2007. In their first collaborative film Zanny Begg and Oliver Ressler focus on the current state of the counter-globalisation movement in a project which grows out of both artists’ preoccupation with globalisation and its discontents. The film, which combines documentary footage, interviews, and animation sequences, is structured around three questions pertinent to the movement: Who are we? What is our power? What would it mean to win?

Almost ten years after ‘Seattle this film explores the impact this movement has had on contemporary politics. Seattle has been described as the birthplace for the ‘movement of movements’ and marked a time when resistance to capitalist globalisation emerged in industrialised nations. In many senses it has been regarded as the time when a new social subject ‘the multitude’ entered the political landscape. Recently the counter-globalisation movement has gone through a certain malaise accentuated by the shifts in global politics in the post 911 context.

The protests in Heiligendamm seemed to re-assert the confidence, inventiveness and creativity of the counter-globalisation movement. In particular the five finger tactic where protesters spread out across the fields of Rostock slipping around police lines proved successful in establishing blockades in all roads into Heiligendamm. Staff working for the G8 summit were forced to enter and leave the meeting by helicopter or boat thus providing a symbolic victory to the movement.

‘What Would It Mean To Win?’, as the title implies, addresses this central question for the movement. During the Seattle demonstrations ‘we are winning’ was a popular graffiti slogan that captured the sense of euphoria that came with the birth of a new movement. Since that time however this slogan has been regarded in a much more speculative manner. This film aims to move beyond the question of whether we are ‘winning’ or not by addressing what would it actually mean to win.

When addressing the question ‘what would it mean to win?’ John Holloway quotes Subcomandante Marcos who once described ‘winning’ as the ability to live an ‘infinite film program’ where participants could re-invent themselves each day, each hour, each minute. The animated sequences take this as their starting point to explore how ideas of social agency, struggle and winning are incorporated into our imagination of politics.

The film was recorded in English and German and exists also in a French subtitled version. ‘What Would It Mean To Win?’ will be presented in screenings in a variety of contexts and will also be part of the upcoming installation ‘Jumps and Surprises’ by Begg and Ressler, which will present a broader perspective of different approaches to the counter-globalisation movement.

Concept, Interviews, Film Editing, Production: Zanny Begg & Oliver Ressler

Interviewees: Emma Dowling, John Holloway, Adam Idrissou, Tadzio Mueller, Michal Osterweil, Sarah Tolba

Camera: Oliver Ressler

Animation: Zanny Begg

Sound: Kate Carr

Image Editing: Markus Koessl

Sound Editing: Rudi Gottsberger, Oliver Ressler

Special thanks to Turbulence, Holy Damn It, Conrad Barrett

Grants: Bundesministerium fr Unterricht, Kunst und Kultur

College of Fine Art Research Grants Scheme, Sydney

A review of THE THIRD MIND at Le Palais de Tokyo

Curated by Ugo Rondinone

THE THIRD MIND

Le Palais de Tokyo

13, avenue du president Wilson 75116 Paris

September 7th – January 8th

I first want to congratulate the guest curator Ugo Rondinone and the new director of Le Palais de Tokyo, Marc-Olivier Wahler, for mounting a really high-quality group show (*) that criss-crosses an assortment of generational frontiers and stylistic barriers. Ugo Rondinone is an artist known for his talent for building systems of connections and given the visual results of this exhibit; he has, in large part, very good taste in art. I particularly enjoyed his assembling excellent works of Brion Gysin – William S. Burroughs, Ronald Bladen, Lee Bontecou, Andy Warhol, Nancy Grossman, Cady Noland, Martin Boyce, Paul Thek and Emma Kunz.

I think what might be interesting about this disquieting show, is to look at how this group show differs in its conjoining (or not) from other group shows by pinning it to the collaborative work of Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs from the early 1960s known as The Third Mind. Also we can place THE THIRD MIND in the context of wider connections and ponder at what point does homage turn into exploitation?

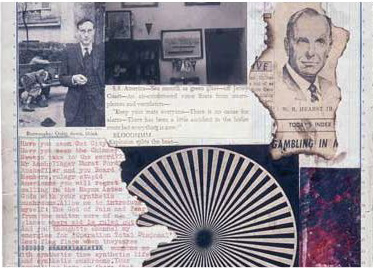

First some background. Beat writer Burroughs and the artist Brion Gysin, known predominantly for his rediscovery of the Dada master Tristan Tzara’s cut-up technique and for co-inventing the flickering Dreamachine device, worked together in the early 1960s on a publishing project that used a chance based cut-up method. A cut-up method consists of cutting up and randomly reassembling various fragments of something to give them a completely new and unexpected meaning. 1+1=3 (**) In the recent biography of Allen Ginsburg, Celebrate Myself, Ginsburg’s archivist, Bill Morgan, excellently recounts some of the genesis of Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs forays into radical Dada cut-up technique and collaboration based on Ginsburg’s diary entries.

Gysin in the mid 1950’s pointed out to Burroughs that collage technique has been a regular tool in painting and graphics since half a century. This came as late news to the young Beat writers of that time, so it is perhaps not surprising that Ginsburg’s first exposure to Burroughs’s use of the cut-up was met with distain – Ginsburg considered it something along the lines of a parlor trick. (p. 318) Even more, Ginsburg speculated from NYC that Burroughs had lost his mind through lack of sex (note: Burroughs lusted after Ginsburg in vain). As a joke, Ginsburg and Peter Orlovsky cut up some of their own poems and rearranged them and sent them to Burroughs with the note ‘Just having a little fun mother’. (pp. 318 – 319). However Burroughs was so dedicated to the random cut-up method that he often defended his use of the technique. When Ginsburg and Orlovsky arrived in Tangiers in 1961, Burroughs was working on an even more advanced use of the cut-up; he and Ian Sommerville were cutting and splicing audiotapes and Burroughs was making collages from newspapers and photographs while proclaiming that poetry and words were dead. (pp.331-332)

Burroughs however soon began work on a cut-up novel, the Soft Machine – drawing material from his The Word Hoard. (**) This manuscript was soon being ‘assembled’ and edited by Ian Sommerville and Michael Portman; Burroughs’s companions. Sommerville was regularly speaking of building electrical cut-up machines.

Burroughs would soon begin collaborating on a book project with Brion Gysin using the cut-up method; cutting up and reassembling various fragments of sentences and images to give them a new and unexpected meaning. The Third Mind is the title of the book they devised together following this method – and they were so overwhelmed by the results that they felt it had been composed by a third person; a third author (mind) made of a synthesis of their two personalities.

Ginsburg remained highly skeptical for some time, but following his travels in India came to appreciate the cut-up technique; even while never employing it.

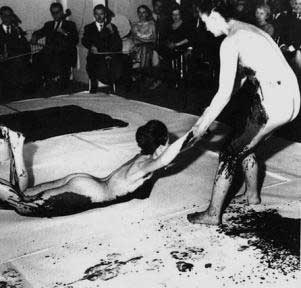

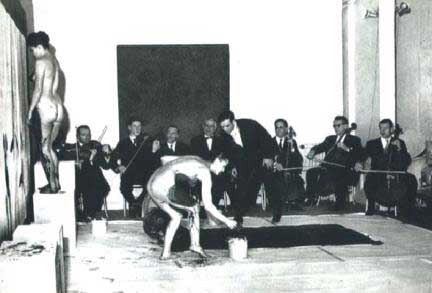

Now for THE THIRD MIND show itself. Two major works (themselves multitudinal) advance well Rondinone’s thesis of the third mind. Of course, foremost is the Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs collaboration The Third Mind. An entire gallery is devoted to the maquettes for this unpublished book from the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art – and it does not disillusion the 4th mind: that of the viewer/reader. It is a golden hodgepodge

feast and serves as the underpinnings of the exhibit.

Then there is the glamorous video installation/accumulation of Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests from 1964-1966: a group of silent b&w three-minute films in which visitors to the Warhol factory try to sit still. Here we see an interlaced presentation that visually connect the youthful faces of Edi Sedgwick, Susan Sontag, Nico, John Giorno, Jonas Mekas, Gerald Melanga, Jack Smith, Paul Thek, Lou Reed and the distinguished Marcel Duchamp. The presentation is structurally connectivist given its 4 directional presentation as a low laying sculpture. It is incredibly enjoyable. Plus the room is ringed with black haunting photograms called Angels by the fascinating Bruce Conner from 1973-75.

In terms of a more traditional synthetic associational curatorial fission, the strongest effect was achieved for me in the Ronald Bladen, Nancy Grossman, Cady Noland gallery. Everything here is screaming in harmony of power, sex and violence. The entire space felt hard as nails ? most all of it a macho silver and black. Bracketing the huge gallery were long rows of Nancy Grossman’s famous black-leathered heads, aggressively sprouting phallic shapes like picks and horns. Ronald Bladen’s 1969 minimal masterwork The Cathedral Evening aggressively dominates the interior space with a mammoth triangle breach. This is backed up by his famous Three Elements from 1965. Then, giving the gallery a sense of an almost palpably Oedipal contest, is a large group of superb black on silver Cady Noland anthropological silkscreens on metal from the early 1990s.

The other room that really collectively worked for me held Paul Thek and Emma Kunz. Three wonderful Paul Thek Meat Piece are there; weird post-minimal sculptures that sickly encase flayed body sections in wax in long yellow transparent plexiglas shrines that literally shine. This meat-machine mix is counter-pointed with the healing magnetic-field ephemerality of Emma Kunz’s geometric drawings, done with lead and colored pencils or chalk on graph paper. It was easy to envision some fierce spiritual forces zapping each other throughout that area.

Other rooms bring the connectivest bent to a jolting halt. I simply admired Martin Boyce’s huge neon sculpture (Boyce channeling Dan Flavin), but it produced no associative effects with what else was in the room. Worse of all was a room entirely devoted to the work of Joe Brainard. What was that doing there? One strains to see (or imagine) even a 2nd mind in that space. So the unavoidable thought arises, well, Rondinone must like this stuff – so that is at least two minds in synch. But does Rondinone think there is anything still interesting in a Gober sink? His The Split-up Conflicted Sink from 1985 also played a huge flat note for me in this supposed visual symphony, as did the overly unembellished black crosses of Valentin Carron, the stupid car bashed installation by Sarah Lucas, and the cloying faux-naive canvases of Karen Kilimnik. How to connect this boring, stupid and naive work to the third mind connectivity theme?

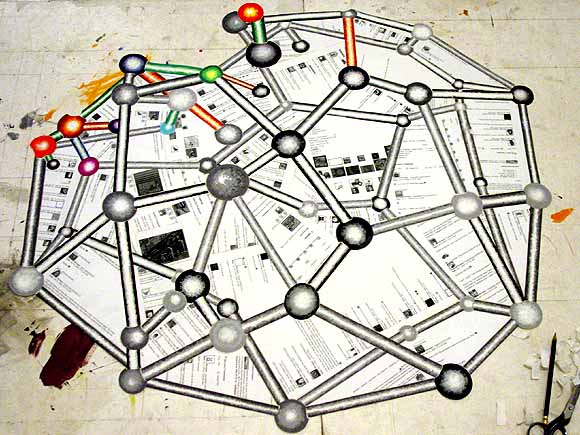

OK. I will. On thinking about the show on my way home, I concluded that the show’s relationship to connectivity is gravely naive and passe (if pleasant in a quaint, charming way) in lieu of the multi-networked world in which we now reside. By now various theories of complexity have established an undeniable influence within cultural theory by emphasizing open systems and collaborative adaptability. One ponders if Rondinone has ever even heard of the theories of Tiziana Terranova, Eugene Thacker or other cultural workers involved in the issues of human-machine symbiosis as interface within our inter-network media ecology. So yes, part of the pleasure for me was bathing in this old fashioned naivety, having just spent some serious time reading and writing on the topics of conspiratorial shadow activities (****) and viral software logic based on complex inter-connectionism (*****). Placed against issues of avant-garde cybernetics, the coupling of nature and biology via code, media ecologies, distributed management teams, internet mash-up music, artificial life swarms, the political herd mind, and Negri/Hardt’s multitudes; THE THIRD MIND played in my mind like a romp through a kindergarten playpen. Nice. It felt good to forget about that pervasive nagging political/cultural feeling of stalemate created by the resilience of our current reality in that it assimilates everything.

But no, Ugo Rondinone did not randomly cut and reassemble art to create a new third meaning. He did not cut-up anything. He did, like every music dj, fashion designer, and group show curator, remix contemporary expression from recent decades to permit new meanings to emerge from the mix. The ideas in the collaborative work of Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs were not needed to achieve this end – and perhaps they were poorly intellectually served here (even though it was great to see the work). There was no use of chance or randomness evident here (even the re-shuffled catalogue pages I heard was rather suspiciously non-random) that is necessary for a really unexpected – and perhaps disastrous – result. This show did not go that far. There was no randomly reassembling of various fragments of something to give them a completely new and unexpected meaning (like I saw in the show Rolywholyover: A Composition for Museum by John Cage at the Guggenheim Museum in Soho NYC in 1994). THE THIRD MIND is just a standard, but good, heterogeneous art show where the whole is greater than its parts. Which is as it must be.

The show contains work from: Ronald Bladen, Lee Bontecou, Martin, Boyce, Joe Brainard, Valentin Carron, Vija Celmins, Bruce Conner, Verne Dawson, Jay Defeo, Trisha Donnelly, Urs Fischer, Bruno Gironcoli, Robert Gober, Nancy Grossman, Hans Josephsohn, Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs, Toba Khedoori, Karen Kilimnik, Emma Kunz, Andrew Lord, Sarah Lucas, Hugo Markl, Cady Noland, Laurie Parsons, Jean-Frederic Schnyder, Josh Smith, Paul Thek, Andy Warhol, Rebecca Warren, and Sue Williams. Also applause to Marc-Olivier Wahler for cutting Le Palais de Tokyo into large but manageable discrete spaces. What a relief from the prior cavernous chaos.

(**) Recently I heard Martin Scorsese speak about how any editing together of two shots in a film creates a third subjective image effect in the mind of the viewer.

(***) The Word Hoard is a collection of Burroughs’s manuscripts written in Tangier, Paris, and London that all together created the super mother-load manuscript that served as the basis for much of Burroughs’s cut-up writings: The Soft Machine, Nova Express, The Ticket That Exploded, (together referred to as The Nova Trilogy or Nova Epic). Even Naked Lunch was taken from sections of The Word Hoard. There was also produced a text called Dead Fingers Talk in 1963 which contains excerpts from Naked Lunch, The Soft Machine and The Ticket That Exploded – combined together to create a new narrative. Also, via Burroughs’s artistic collaborations with Brion Gysin and Ian Sommerville, the cut-up technique was combined with images, Gysin’s paintings, and sound, via Somerville’s tape recorders. Some of these recordings can be heard here.

There were also a number of cut-up films that were produced which can

be seen here:

http://www.ubu.com/film/burroughs.html

William Buys a Parrot (1963)

Bill and Tony (1972)

Towers Open Fire (1963)

Ghost at n?9 (Paris) (1963-72)

The Cut-Ups (1966)

IF/THEN

A Book Review of Digital Contagions: A Media Archaeology of Computer Viruses by Jussi Parikka (Peter Lang Books, 2007, 327 pages) by Joseph Nechvatal.

{loop:file = get-random-executable-file;

if first-line-of-file = then goto loop;

prepend virus to file;}

-Fred Cohen, Computer Viruses: Theory and Experiments

We cannot be done with viruses as long as the ontology of network culture is viral-like.

-Jussi Parikka, The Universal Viral Machine

One could be forgiven for assuming that a book with the title ‘Digital Contagions: A Media Archaeology of Computer Viruses’ would be of sole interest to those sniggering hornrimmed programmers who harbor an erudite loathing of Bill Gates and an affection for the Viennese witch-doctor. Actually, it is a rather game and enthralling look, via a media-ecological approach, into the acutely frightening, yet hysterically glittering, networked world in which we now reside. A world where the distinct individual is pitted against – and thoroughly processed by – post-human semi-autonomous software programs which often ferment anomalous feelings of being eaten alive by some great indifferent artificiality that apparently functions semi-independently as a natural being.

Though no J. G. Ballard or William S. Burroughs, Jussi Parikka nevertheless sucks us into a fantastic black tour-de-force narrative of virulence and the cultural history of computer viruses (*), followed by innumerable inquisitive innuendoes concerning the ramifications for a creative and aesthetic, if post-human, future. Digital Contagions is impregnated with fear and suspicion, but we almost immediately sense that it also contains an undeniable affirmative nobility of purpose; which is to save the media cultural condition -and the brimful push of technological modernization in general – from catastrophically killing itself off.

This admirable embryonic redemption is achieved by a vaccination-like turning of tables, as Parikka convincingly demonstrates that computer viruses (semi-autonomous machinic/vampiric pieces of code) are not antithetical to contemporary digital culture, but rather essential traits of the techno-cultural logic itself. According to Parikka, digital viruses in effect define the media ecology logic that characterizes our networked computerized culture in recent decades.

We may wish to recall here that for Deleuze and Guattari, media ecologies are machinic operations (the term machinic here refers to the production of consistencies between heterogeneous elements) based in particular technological and humane strings that have attained virtual consistency. Our current inter-network ecology is a comparable combination of top-down host arrangements wedded to bottom-up self-organization where invariable linear configurations and states of entanglement co-evolve in active process. Placing the significant role of the virus in this mix in no uncertain terms, Parikka writes that, ‘the virus truly seems to be a central cultural trope of the digital world’. (p. 136) Indeed digital viruses are recognized by Parikka as the crowning culmination of current postmodern cultural trends – as viruses, by definition, are merger machines based on parasitism and acculturation. So it is not only their symbolic/metaphoric power that places them firmly in a wider perspective of cultural infection; it is their formal structure, in that they procure their actuality from the encircling environment to which they are receptively coupled.

Moreover, with the love of an aficionado, Parikka lucidly demonstrates that computer viruses are indeed a variable index of the rudimentary underpinning on which contemporary techno culture rests. He astutely anoints the indexical function of the virus by establishing not only its symbolic melancholy power in relation to the human body and sex, but by folding the viral life/nonlife model (**) into key cultural areas underlying the digital ecology; such as bottom-up self-organization, hidden distributed activity and ethereal meshwork. In that sense Parikka describes network ecology as both actual and virtual, what I have elsewhere identified as the viractual. (Briefly, the viractual is the stratum of activity where distinct actualizations/individuations are materialized out of the flow of virtuality.) But some viruses do not simply yield copies of themselves, they also engage in a process of self-reproducing autopoiesis: they are copying themselves over and over again but they can also mutate and change, and by doing so, Parikka maintains, reveal distinguishing aspects of network culture at large.

I would add that they mimic the manneristic aspects of late post-modernism in general, particularly if one sees modernism as the great petri dish aggregate in which we still are afloat. So computer viruses are recognized here as an indexical symptom also of a bigger cultural tendency that characterizes our post-modern media culture as being inserted within a modern (purist) digital ecology. This aspect provides the book with a discerning, yet heterogeneous, comprehension of the connectionist technologies of contemporaneous techno culture. But beyond the techno-cultural relevance, the significance of the viral issues in Parikka’s book to ALL cultural production is evident to anyone who has already recognized that digitalization has become the universal technical platform for networked capitalism. As Parikka himself points out, digitalization has secured its place as the master formal archive for sounds, images and texts. (p. 5) Digitalization is the double, the gangrel, that accompanies each of us in what we do – and which accounts for our cultural feelings of vacillating between anxiety and enthusiasm over being invaded by something invisible – and the sneaky suspicion that we have been taken control of from within.

To begin this caliginous expedition, Digital Contagions plunges us into a haunting, shifting and dislocating array of source material that thrills. Parikka launches his degenerate seduction by drawing from, and intertwining in a non-linear fashion, the theories of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (for whom my unending love is verging on obsession), Friedrich Kittler, Eugene Thacker, Tiziana Terranova, N. Katherine Hayles, Lynn Margulis, Manuel DeLanda, Brian Massumi, Bruno Latour, Charlie Gere, Sherry Turkle, Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela, Deborah Lupton, and Paul Virilio. These thinkers are then linked with ripe examples from prankster net art, stealth biopolitics, immunological incubations, the disassembly significance of noise, ribald sexual allegories, antibody a-life projects, various infected prosthesis, polymorphic encryptions, ticklish security issues, numerous medical plagues, the coupling of nature and biology via code, incisive sabotage attempts, anti-debugging trickery, genome sequencing, parasitic spyware, killer T cell epidemics, rebellious database deletions, trojan horse latency, viral marketing, inflammatory political resistance, biological weaponry, pornographic clones, depraved destructive turpitudes, rotten jokes, human-machine symbiosis as interface, and a history of cracker catastrophes. All are conjoined with excellent taste. The shock effect is one of discovering a poignant nervous virality that has been secretly penetrating us everywhere.

Digital Contagions’s genealogical account is proportionately impressive, as it devotes satisfactory space to the discussion of historical precedent; including Turing machines, Fred Cohen’s pioneering work with computer viruses, John von Neumann’s cellular automata theory (i.e. any system that processes information as part of a self-regulating mechanism), avant-garde cybernetics, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the Creeper virus in the Arpanet network, the coupling machines of John Conway, the nastily waggish Morris worm, Richard Dawkins’s meme (contagious idea) theory; and even the under known artistic hacks of Tommaso Tozzi. Furthermore, the viral spectral as fantasized in science fiction is adequately fleshed out, paying deserved attention to the obscure but much loved (by me, anyway) 1975 book The Shockwave Rider by John Brunner and the celebrated cyberpunk novel by Neal Stephenson, Snow Crash; among other speculative books and hallucinatory films.

But the pinnacle of interest, for me, of this engaging and educative read is its conclusion where Parikka sketches out an alternative radical media-ecological perspective hinged on the viral characteristics of self-reproduction and a coupling of the outside with the inside typical of artificial life (a-life). He correctly maintains that viral autopoiesis undertakings, like Thomas S. Ray’s Tierra virtual ecology art project, provides quintessential clues to interpreting the software logic that has produced, and will continue to produce, the ontological basis for much of the economic, political and cultural transactions of our current globalizing world.

Here he has rendered problematic the safe vision of virus as malicious software (virus as infection machine) and replaced it with a far more curious, aesthetic and even benevolent one; as whimsical artificial life (a-life). Using viral a-life’s tenants of semi-automation, self-reproduction, and host quest; Parikka proposes a living machinic autopoiesis that might provide a moebius strip like ontological process for culture.

Though suppositional, he bases his procedure in formal viral attributes – not unlike those of primitive artificial life with its capability to self-reproduce and spread semi-autonomously (as viruses do) while keeping in mind that Maturana/Varela’s autopoiesis contends that living systems are an integral component of their surroundings and work towards supporting that ecology. Parikka here picks up that thread by pointing out that recent polymorphic viruses are now able to evolve in response to anti-virus behaviors. Various viruses, known as retroviruses, (***) explicitly target anti-virus programs. Viruses with adaptive behavior, self-reproductive and evolutionary programs can be seen, at least in part, as something alive, even if not artificial life in the strongest sense of the word. Here we might recall John Von Neumann’s conviction that the ideal design of a computer should be based on the design of certain human organs – or other live organisms. The artistic compositional benefit of his autopoiesic virality theory, for me, is in allowing thought and vision to rupture habit and bypass object-subject dichotomies.

I wish to point out here that although biological viruses were originally discovered and characterized on the basis of the diseases they caused, most viruses that infect bacteria, plants and animals (including humans) do not cause disease. In fact, viruses may be helpful to life in that they rapidly transfer genetic information from one bacterium to another, and viruses of plants and animals may convey genetic information among similar species, helping their hosts survive in hostile environments.

Already various theories of complexity have established an influence within philosophy and cultural theory by emphasizing open systems and adaptability, but Parikka here supplies a further step in thinking about ongoing feedback loops between an organism and its environment, what I am tempted to call viralosophy. Viralosophy would be the study of viral philosophical and theoretical points of reference concerning malignant transformations useful in understanding the viral paradigm essential to digital culture and media theory that focuses on environmental complexity and interconnectionism in relationship to the particular artist. Within viralosophy, viral comprehension might become the eventual – yet chimerical – reference point for culture at large in terms of a modification of parameters, as it promotes parasite-host dynamic interfacings of the technologically inert with the biologically animate, probabilistically.

So the decisive, if dormant, payload that is triggered by reading this book, for me, is an enhanced understands of pagan and animist sentiment which recognizes non-malicious looping-mutating energy feedback and self-recreational dynamism that informs new aesthetic becomings which may alter artistic output. Possibly heuristic becomings (****) that transgress the established boundaries of nature/technology/culture and extend the time-bomb cognitive nihilism of Henry Flynt. This affirmative viral payload forces open-ended multiplicities onto art that favor new-sprung conceptualizations and rebooted realizations. Here the artist comes back to life as spurred a-life, and not as a sole articulation of the pirated environment of currency. So the so-called art virus is not to be judged in terms of its occasional monetary payload, but by the metabolistic characteristics that make art reasonable to discuss as a form of extravagant artificial life: triggered emergence, resilience and back door evolution.

(*) A computer virus is a self-replicating computer program that spreads by inserting copies of itself into other executable code or documents. A computer virus behaves in a way similar to a biological virus, which spreads by inserting itself into living cells. Extending the analogy, the insertion of a virus into the program is termed as an “infection”, and the infected file, or executable code that is not part of a file, is called a “host”.

(**) Scientists have argued about whether viruses are living organisms or just a package of colossal molecules. A virus has to hijack another organism’s biological machinery to replicate, which it does by inserting its DNA into a host.

(***) Retroviruses are sometimes known as anti-anti-viruses. The basic principle is that the virus must somehow hinder the operation of an anti-virus program in such a way that the virus itself benefits from it. Anti-anti-viruses should not be confused with anti-virus-viruses, which are viruses that will disable or disinfect other viruses.

(****) A heuristic virus cleaner works by loading an infected file up to memory and emulating the program code. It uses a combination of disassembly, emulation and sometimes execution to trace the flow of the virus and to emulate what the virus is normally doing. The risk in heuristic cleaning is that if the cleaner tries to emulate everything, the virus might get control inside the emulated environment and escape, after which it can propagate further or trigger a destructive retaliation reflex.

Joseph Nechvatal

Mid-September 2007, Marrakech

The exhibition was curated by critical game theorist Corrado Morgana in partnership with Marc Garrett and Ruth Catlow Furtherfield’s HTTP Gallery. It included works by Axel Stockburger, TheGhost, Corrado Morgana, Ziga Hajdukovic, Progress Quest and JODI. The exhibition was accompanied by a short publication with a keynote text by Axel Stockburger.

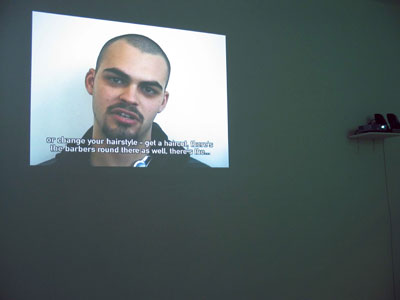

Zero Gamer positions itself as a meaningful interruption of the playing process in order to facilitate a platform for reflection. The works addressed different aspects of digital gameplay, although they did not take the form of playable games themselves. Rather, their purpose was to allow the audience to engage with different crucial issues arising from the hugely complex field of games and gaming but without actually playing. The artists employed different strategies to enable this, ranging from intervening with mechanics such as artificial intelligence and in-game physics to removing game tokens and hazards enabling discussions about the meaning of player engagement. Zero Gamer does not stand for a return to more traditional forms of aesthetic production. On the contrary, it points in the opposite direction, placing itself as the necessary interstice between gaming cycles.

Zero Gamer was first presented by HTTP Gallery at the London Games Festival Fringe in 2007. The remixed exhibition, Zero Gamer (GOLD) was on show at HTTP Gallery between 2-18 November 2007.

Zero Gamer text by Ruth Catlow, Marc Garrett (HTTP/Furtherfield.org) and Corrado Morgana 2007.

On Archive.org – Wayback machine – https://bit.ly/3ya6nqe

List of artworks

Mario Trilogy: Mario battle no.1 (2000), Mario is drowning (2004) and Mario is doing time (2004). by Myfanwy Ashmore

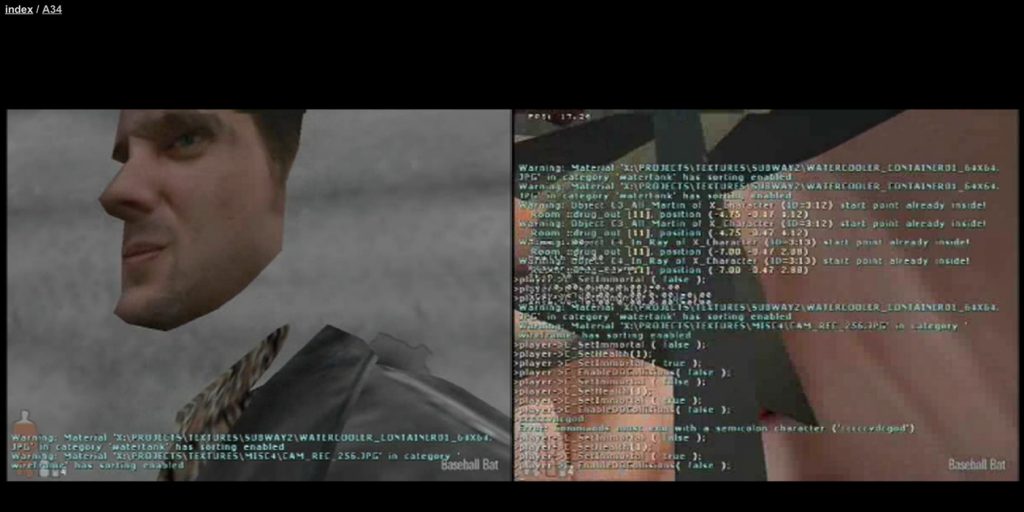

Max Payne Cheats Only (2004). By JODI

Boys in the Hood (2006). By Axel Stockburger

CarnageHug (2007). By Corrado Morgana

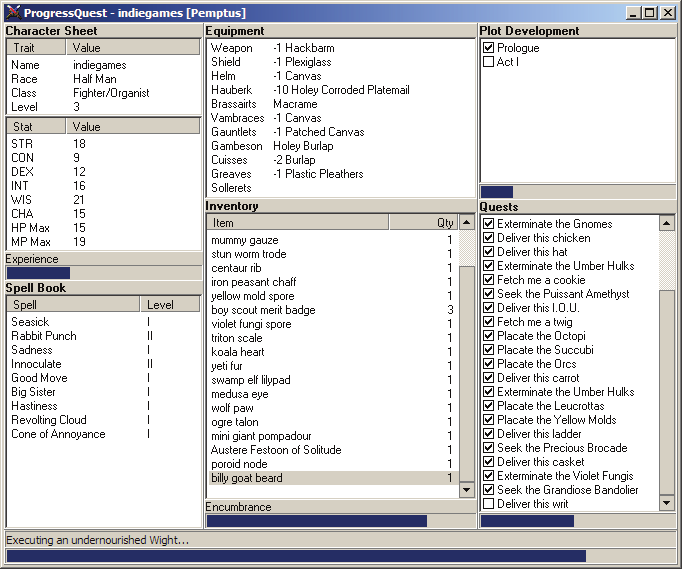

Progress Quest (2004). By Eric Fredricksen

1d Tetris (2002). By Ziga Hajdukovic

Youtube Showreel

Breen and Alyx by Wo0Yay

Launch Line by TheGhost

Real Action Tetris by Mega64

Hamster Video Game uploaded by Jason the Vid Guy

Tetris The Absolute The Grandmaster2 Plus Death Mode uploaded by madeofwin

Space Invaders in Real Life uploaded by ChugaTheMonkey

Self-playing Mario by Diagram

TAS video – Megaman 3,4,5 and 6 by Angerfist and Baxter

Exhibition Images

2nd part of Auriea Harvey’s and Michael Samyn’s retrospective on Furtherfield. In the 1st interview they discussed about the history of their previous incarnation as net art collaborators, Entropy8Zuper! This time Maria Chatzichristodoulou (aka Maria X), talks with them about their mutation into Tale of Tales and why and how this change came about…

Click here to read the 1st interview

‘Who are you?’ I ask. I am a bit confused: although I know them as Entropy8Zuper!, their most recent piece, The Endless Forest, is created by Tale of Tales. Auriea explains that E8Z! was very personal, as it was the merging of entropy8 (herself) and zuper! (Michael). ‘E8Z! is just the two of us’ says Michael.

It has always been like that, our little personal corner of the web… But with Tale of Tales, we took a step towards an audience in the sense that we wanted to make things the wider audience could enjoy actively.

In 2002 E8Z! Found the for-profit company Tale of Tales. Tale of Tales’s brief is to produce alternative commercial video games for a niche market that does not enjoy the violence and blood-shedding of most mainstream games. According to their website, their aim is to design and develop immersive websites and multimedia environments with a strong emphasis on narration, play, emotion and sensuality.

http://tale-of-tales.com/information.html (retrieved August 2006)

It seems to me that the current work of ToT is very different from E8Z!’s early work. Do they feel that they have lost something? Yes, they have, says Michael, but that was something they wanted to lose. The shift from E8Z! to Tale of Tales was a natural evolution for them. The main differences between the two have to do with their maturity as artists and as a couple, and the technological developments that took place from 1999 to 2003: E8Z! Produced work for each other, while ToT’s main aim is to reach audiences; E8Z! was operating on the crossover between art and design, while ToT looks at the cross-pollination of art and video games; E8Z! Produced work for the web while ToT’s pieces are downloadable.

ToT’s most well-known work? In fact, the only developed work they have released? Is The Endless Forest (2005-). This is a hybrid, multi-layered piece that operates on several levels: it is an online multiplayer game, it is also a social screensaver, a live performance environment, a virtual world, and a collective fairytale: In The Forest, you are a deer. You live deep in the idyllic, peaceful forest. You spend your time roaming around the forest with other deer. You eat, sleep under the shadow of the trees, drink water from the lake, rest by the ancient ruins, play with other deer and collect flowers. There are also things you cannot do in the forest: you cannot speak, for example. This is not just any forest… In The Endless Forest, magical things can happen: beasts can fly, all the flowers can bloom at once, stones can fall from the sky, and the rain can be gold. Nobody knows what the Twin Gods will come up with to entertain themselves… While in the Forest, there are no goals to achieve or rules to follow. Being there is what this experience is about.

So how did The Endless Forest start?, I ask. I actually know that the prototype was commissioned by the Musee d’Art Moderne Grad-Duc Jean (last visit 27/04/2007) (Museum of Modern Art of Luxemburg) in September 2003. (Now that I think about it, this is rather strange given Auriea and Michael’s comments about net artists selling their work to Museums!) “At that time ToT were working on 8, a research project which they tried to turn into a commercial game. This was the first time that they were trying to produce a commercial video game, and it was hard to find a balance between the mainstream publishers’ requirements and their wish to produce an alternative, non-violent and non-sexist title. 8 was still quite traditional in that it was based on action, had a clear-cut narrative and the player had to perform certain tasks in order to achieve his/her aim. So The Forest came up as a reaction against these very specific sets of rules about how a game should function. ToT came up with the idea on a train-ride back from Luxembourg: the train was driving through a forest (Ardennes) and they could see deer roaming in it… It was a bit of a joke to start with,” They giggle.

[M:] So next to that (8) was The Endless Forest, which was sort of an anti-game. It was like ‘you play a deer, in a forest, and you can’t talk, and you can’t level up’, ha ha! And there’s lots of things you can’t do, and that’s, like, cool! ? Once ToT created a forest it took a long time for the project to fully emerge. Originally they were not at all clear about what this forest would be or how it would evolve. There was not a single deer in the prototype forest that was presented, for example.

One of the reasons E8Z! had decided to stop Wirefire was that they found its ‘liveness’ both limited and limiting. Wirefire could only be live once per week, while Auriea and Michael were performing in it:

M: It only lived an hour per week, while there were still people who were very valid and active participants there. They could probably do a performance themselves or whatever. So that’s where the idea of a persistent world came from. Everybody could be present in the environment, and there’s no division between the artist and the audience.

So the idea was to create The Forest as a persistent world depending for its aliveness on its inhabitants rather than its creators. It took a while to get it started as they were busy working on 8. They only went back to work on The Forest in 2005 once it was clear that 8 was too weird and different a game for it to get commercial funding. By then, they had also realised how difficult and expensive these games are to produce, and what building the full design of The Endless Forest would mean in terms of money and time… Eventually, they came up with the idea of chopping the Forest’s complex design into pieces, seeking arts funding to produce each piece and release these sequentially.

From the very beginning of their career, first as E8Z! and then ToT, Auriea and Michael have explored ways for their work to be financially self-sustainable: as E8Z! they did a great many commercial projects, for example projects like Museum of Sex (2002), Making Waves and Next Wave Festival (2002-3), Oblomow (2006); and never sought arts funding. Instead, they sustained their art through the income generated by their web design. They even tried to raise money through the art itself: skinonskinonskin was presented as a pay-per-view project, whereas the Godlove Museum has recently been rebuilt in flash and is available to download for a fee of 20 euros. And, although as ToT they have been dependent on arts funding for the development of The Endless Forest and have not generated any income as yet, their brief is to produce commercial games people will want to pay for.

The Endless Forest is available to download and play for free. This is because it was released piece by piece, and so ToT felt that they couldn’t charge for the first very basic version of the game. Auriea explains that another reason they don’t charge is that this is their first game environment, and they wanted to have as many people/deer in the forest as possible in order to test how the environment works and receive feedback from players. This is a way for them to demonstrate their abilities as game developers and become known in the gaming world. They think that this approach worked as there are more than 13,000 deer currently roaming in the forest (!), and they can see that there is an audience out there interested in their work. This is unlike most net art practices, which are normally accessible online and open to all. Why do Auriea and Michael think that it is OK to ask people to pay to view their work?

It all started because they only wanted a ‘serious’ audience to be able to access their work, explains Auriea. To them, skinonskinonskin was a very personal project, and they wanted to ensure that it would only be accessed by people who would make an informed and conscious decision to visit it. This was more of a symbolic gesture than a real attempt to generate income, claims Auriea. People had to pay minimal fees, and the money generated was shared. Charging people to view the project was just a way of protecting the piece ? and themselves? by anyone who wasn’t interested enough in it.

Charging for downloads of the Godlove Museum is not the same: this time, they really felt that, since re-building the project on a more sustainable technical platform to make it fully accessible was really hard work, it is only fair to ask people who want to download this new version of the project to pay a fee. They did not know whether this would work, and they saw it as an experiment in e-commerce. They both find it difficult to understand why paying for net art is so taboo: people pay for books, magazines, movies, music and games… They pay for a night out with friends. They often pay exuberant prices to collect art objects shown in galleries. Why is it taboo to charge people to view and/or download a net art piece? E8Z! ask. People even pay for the technology to view the piece, like their hardware, software, and Internet connection, says Michael, rather baffled. The only thing they refuse to pay for is the art itself…

I have to admit that I am the culprit of this attitude myself. When I realised I could download a new version of the Godlove Museum for 20 euros, I thought, ‘Well, that’s only fair; that’s not more than I would pay for a book’, but for some reason, I was still resistant to the idea… In the end, I didn’t buy it. I can’t even explain why I didn’t buy it! Why this resistance to pay for art on the Internet? I ask E8Z!:

A: I think it’s the arts community and the way they’re used to relating to what people produce. ‘Art should be free’ someone said to us, you know. We’re like, well, you pay for movies and music… But the sad thing is that most people wouldn’t look at it seriously, even if it were free and online. And I think that this is what happened with net art: people stopped looking at it seriously, stopped examining it. With games, it is completely different. People seriously look at it. They’ll play a game that lasts twenty hours, you know? They’ll play it all the way through, and then they’ll play it repeatedly and again so they can do a speed run and then do it in two hours. And then they’ll record it and put it on YouTube. So it’s a different audience, and that’s the audience that we decided we like better. Not only will they look at, dissect and criticise what you’re working on, but they’ll also pay for it.

Michael thinks that the privacy of a net art experience is another factor that deters people from paying for it: it lacks social status. Visiting a gallery, going to the cinema, and going out with friends are all social activities that may help define one’s identity as a popular, well-educated, cultivated, intelligent person. On the other hand, viewing art online in the privacy of one’s house is something that no one will even know… Why on earth would one want to pay for such a ‘pervert’ experience? Laughs Michael. Whatever the reasons this doesn’t work, it doesn’t: hardly anyone has paid to download the Godlove Museum…

Tale of Tales considers it extremely important that they eventually produce projects people will want to pay for. Whether this is called art or entertainment is, for them, irrelevant. They have never wanted to work within a pure art context, says Auriea, as art means nothing to the culture. Absolutely nothing. They have always worked on the borderline between art and something else, like crafts or entertainment, that is more relevant or accessible to popular culture. They think that games are much more successful in involving their users in two-way communication than many ‘interactive’ art projects have been.

It emerges that they have both been keen game-players themselves. Auriea gets very excited talking about the first games she played. Tomb Raider, for example, was a huge inspiration, she laughs. There has been a very strong community element about many MMO (Massively Multiplayer Online) games, and ToT greatly like this. It reminds them of the early Internet. It is about communication, exchange, and limited hierarchy.

M: For many game-players, playing becomes interwoven within the fabric of their lives, and this is another element that Auriea and Michael like about games: this blurring of the boundaries between reality and fiction, when the fairytale becomes part of one’s everyday life. This is how they experienced Wirefire while it was still active, as another space, always available, where they could withdraw together once per week. They hope that this is how The Forest experience will be for its players:

A: So you go in the forest and play for five minutes and then you go off and do whatever you want. Or you come back to your machine, you notice that it’s playing, you ran around for a little while and then you stop. And so it becomes a part of your life, you know… Something that you play for a few minutes, but then it stays with you for the rest of the day. Or something you think about every now and then… Or you want to go back and visit a certain place, you know… For us that’s what Wirefire was too, like this place we visited for an hour every week.

Do they think that The Endless Forest is similar to other popular virtual environments like Second Life? Yes, they both think that it is, because, like Second Life, the main aim of the environment is for people to socialize, hang out together, have fun and possibly collaborate, while it lacks the central attributes of other MMO games such as specific rules, tasks, targets, violence and competition. On the other hand it differs from Second Life in that is is an authored environment. Whereas SL duplicates elements of RL within a virtual context, The Forest is a fairytale world and places its users straight within a specific narrative. Auriea and Michael’s work has always been about story-telling: they might not produce linear stories with plots, but they like to create narrative environments that transport audiences/users from their everyday lives into the context of open-ended, multi-layered fictional worlds.

ToT are currently developing a new project called The Path. This is a single-player PC game they hope will become a commercial project that people will be willing to pay for. The Endless Forest experience makes them think that there is an audience out there that appreciates their work, and this is an audience that they would like to approach. Incidentally, although there are no official studies or statistics, ToT have evidence from the players that participate in the Forum. that the majority of their players are female, which is unlike most other MMORPGs. ToT hope that, eventually, they will become independent of public arts funding by being able to generate commercial income.

[M:] There is an audience there, so we think that maybe we should work together with the audience rather than the funders. Maybe that’s a deal we can do with them, like ‘you pay, we make, OK?’ ha ha! We’ll see, it’ll be an experiment…

I think that by now it wouldn’t come as a surprise to say that, when asked about their influences (other than games!) Auriea and Michael refer to paintings: they talk about Baroque and Gothic art; Michael also talks about old Flemish painters. They talk about their love of craftmanship and they attempt to shock me by stating that ?cathedrals are the best 3D narrative environments?. They consider themselves ‘conservative’ (this is a word they repeat quite often) because they insist on story-telling, figuration, and content. They are against cynicism. They believe in hope and beauty. Through their art they want to affect communities and give people joy. And they talk about their work with such affection, as if they speak of a child: Auriea describes how she feels physically ill when their server is down…

Do they come from another time?

Well, whatever era they come from, I wish the best of luck to these two pragmatic-dreamers-in-love…

Among twenty snowy mountains,

The only moving thing

Was the eye of the blackbird.

Edward Picot, originally from Hertfordshire in the UK, now lives in Kent with his wife and daughter. He completed his Ph.D in English Literature in 1997 and then published his thesis in book-form ‘Outcasts from Eden: Ideas of Landscape in British Poetry since 1945’. It deals with modern landscape poetry in the context of the environmental crisis, and includes substantial essays on five postwar British poets Philip Larkin, R S Thomas, Charles Tomlinson, Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney. It also examines the recurring myths of Eden and the Fall, which have been used to assert and explain the superiority of the countryside or natural world (seen as Eden) to the urban environment (seen as the result of the Fall).

His day job is with the health service but he makes time in his schedule for self-publishing online, where you will find various types of work. He publishes something new every month; usually a piece of criticism for one month, then followed by a visual work the next. In 2003 he set up another web site called The Hyperliterature Exchange[1], a review and directory of Hyperliterature works for sale on the Web, with links to the places where it can be bought. Featuring works by artists and poets such as Mac Dunlop, Peter McCarey, Martha Deed and many others this is well worth investigation.

Edward Picot’s visually playful, web art interpretation of Wallace Stevens’s poem Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird[2] is a curious artwork for many reasons. Once you have visited the work it lingers in the mind and on each return it maintains a strong freshness. So what is it in this work that compels me to re-experience its particularly strange and magical reasoning?

Most of Picot’s web artwork communicates to a younger generation as well as for adults. For instance the Flash piece created in 2006 called Frog-o-Mighty[3], was a collaboration between himself and his daughter Rachel. In this piece they used as the main props for the story ornaments from their living-room window-sill, and also the window-sill as the setting, the scenery. On his web site Edward says “Many of my recent creative pieces have been either entirely or partially inspired by the games I play with my daughter Rachel. They therefore feature a lot of jokes and toys.” Frog-o-Mighty first appeared online in Autumn 2006 as part of the Art of the Animal Net Art Exhibition, curated and designed by poet and net artist Jason Nelson.

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird is an altogether more complex affair, even though it is as equally as approachable as Frog-o-Mighty when first experienced. The poem was originally written by the American poet Wallace Stevens[4], who was born in Reading, Pennsylvania on October 2, 1879, and died at the age of seventy-six in Hartford, Connecticut on August 2, 1955. Stevens main focus and interest was to write on ideas that “revolved around the interplay between imagination and reality and the relation between consciousness and the world.”

Unlike Frog-o-Mighty, Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird has a little more interaction, but not much. The only two sections where you can interact (as in clicking) are either at the beginning where you can find some interesting information about the work or at the first page, the main interface for the actual piece itself. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not desperately asking for interaction here. In fact, there are many out there who dispute interaction and the process of just habitually clicking away. Interaction itself, can become more of a means to an end. Sometimes it is nice to just let a work appear and happen in front of you.

Picot says “the idea for this version of Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird came to me a couple of years ago, when I was working on my own one Saturday and there was a heavy fall of snow. In the middle of the afternoon, whilst waiting for the kettle to boil for my umpteenth cup of coffee, I happened to glance out of the window. In the carpark outside grows a crab-apple tree, which bears very bright red fruit in winter, and because of the snow the apples were looking particularly vivid. On one branch of the tree perched a blackbird – a startling contrast with both the white snow and the red fruit. Pretentious soul that I am, I was immediately reminded of Wallace Stevens’ poem, and almost as immediately it occurred to me that the crab-apple tree would make an excellent interface for a new media version, with the bright red apples acting as buttons to call up the different sections.”[5]

On first entering, you immediately come across a silhouette of a crab-apple tree. There are few plants that create greater intrigue or visual impact during all four seasons than the flowering of a crab-apple tree. Colours can range from dark-reddish purples through the reds and oranges to golden yellow and even some green. On this occasion they are deep red and the tree itself bares no leaves so we must assume that it is winter. Crab-apples are usually no larger than 2 inches in diameter, a perfect fruity, nature-nurtured confectionary for a blackbird to peck into. The Celtic year has 13 months and each month is associated with a particular tree and its contribution to mankind, together with its forms of healing and associating for the month they represent. “The crab-apple is the ancient mother of all orchard trees and Britain’s only indigenous apple tree. The flowers are valuable to insects and the fruit is important to birds.”[6]

Before we even touch upon the role of the blackbird or delve into specific areas of the work’s inner content, there are some interesting elements of symbolism at play. Whether this is deliberate or not, it is of course the artists’ prerogative to leave different measures of ambiguity hanging loose according to their process and decision making, which of course can add an extra nuance to the whole mix. In the Garden of Eden story in the Biblical book of Genesis God charges both Adam and Eve to tend the garden in which they live, commanding Adam not to eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil – we know the rest. Picot’s decision to use the archetypal image of a tree as the interface, offers some interesting parallels that may be not as binary, absolute or as literal as the Biblical book of Genesis. Yet it introduces us to elements that symbolically touch upon religion and metaphysics, which weave in and out through the whole piece.

Much of the religious flavour does echo from Wallace Stevens himself, although not with obvious traditional or orthodox values. He believed that God was a human creation. Yet he was interested in something as equivalent which ruled the universe, our hearts and minds. Through his poetic reasoning he found that complete contact with reality was a closer conduit towards discovering the truth of what we really are. Proposing that, ‘with the right idea, we may again find the same sort of solace that we once found in divinity.’ He felt that humanity could find truth and our own heaven(s) through sensuous apprehension of the world. “This supreme fiction will be something equally central to our being, but contemporary to our lives, in a way that god can never again be.” [7] Whether he felt that god was ever a reality is not clear, yet it is interesting that he believed that humanity could replace whatever void with something equally significant and relevant. He also thought that reality was and is a product of our imagination, this shapes the world.

The various contexts created throughout the “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” might be considered from the romantic point of view as haphazard attempts at defining or identifying the writing subject’s relation to an object that is already ambiguous in itself and is a symbol rich in potential for producing hopes and fears. On ‘Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird’. Helen Vendler.

This mixture of existential realism, metaphysical and spiritual reflection through the process and practice of poetic discourse settles neatly with Picot’s own contemporary version of, Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird. As you explore the various audio/visual presentations within each section, which feature stanzas from the poem. Each of the Stanzas introduces or guides you into a specific theme or micro-journey that unfolds before your eyes. The first one begins quite simply, with the visitor being taken to a cartoon image of a mountainous vista then the blackbird, then a zooming into its eye. From then on as you move through the different sections you are taken into different worlds and situations.

It consciously acknowledges the original spirit of the text, whilst introducing a response that at the same time attempts to deal with what these words may mean today. This interpretation of the poem not only gives us the opportunity to appreciate how special the original work is by following the text, whether in order, or haphazardly, but it also creates a moment in time that opens up a rare experience of two creative minds as a kind of collaboration.

There are various other clues within the whole work which can enlighten you of the different influences to Picot’s work. If you click on the eighth crab-apple you are taken to a bookshelf. One of the books on the shelf is called ‘Seeing Things’ which is Oliver Postgate’s autobiography. In the UK, Oliver Postgate [8] was responsible right from the late 1950’s to this day for, the most imaginative and magical children’s television. “He is the creator and writer of some of the most popular children’s television programmes ever seen in Britain. Pingwings, Pogles’ Wood, Noggin the Nog, Ivor the Engine, The Clangers and Bagpuss, were all made by Smallfilms, the company he set up with Peter Firmin, and were shown on the BBC between the 1950s and the 1980s, and on ITV from 1959 to the present day. In a 1999 poll, Bagpuss was voted most popular children’s programme of all time.” My personal favourites are Noggin the Nog, Bagpuss and The Clangers.

Moving away from the mystical and magical elements that reside in the piece, there are a few darker moments to experience. One of them is the portrayal of the real-life disaster such as the Hurricane Katrina disaster on Louisiana and connected regions. Images of newspaper reportage, snippets of the carnage and the hurricane are shown, as well as the blackbird flying across the scenery.

The blackbird whirled in the autumn winds.

It was a small part of the pantomime.

The role of the blackbird seems to me a kind of spectre, a shadow of ours, Stevens’s and Picot’s consciousness. It takes us through the scenes, introducing with each stanza various points of reference, like a guide. It sees what we see, but opens our eyes to re-imagine or remember certain things, letting us come to terms with our own conclusions alongside the poetry, an important trigger and voice of the work.

I am hesitant in continuing with unearthing more of this work. What I will conclude with is that, what I find personally interesting in Picot’s version of Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird. Is that, it is connected to so many different things that exist outside of the work itself. There are jokes, puns, and some darker moments but all presented in a playful light. The world is a backdrop yet at the same time it still manages to maintain a fresh and simple narrative that can be understood at many levels. It revels in its small bites of aspects of human nature; simple yet profound. On the whole, it is a delightful and beautiful experience that can move you and have you thinking about metaphysical matters as well as real situations. It breaths life into our grey and seriously battered worlds, shining a kind of light which asks us to slow down a little and let go of our socially engineered sensibilities and open ourselves up to a snippet of richness that is not trying to impress how clever it is but how imagination can also be about play.

The Hyperliterature Exchange[1]

http://hyperex.co.uk/

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird – Wallace Stevens [2]

http://www.english.uiuc.edu/maps/poets/s_z/stevens/blackbird.htm

Frog-o-Mighty – 2006, Edward Pictot. [3]

http://www.edwardpicot.com/frog-o-mighty/

Wallace Stevens: Biography and Recollections by Acquaintances:[4]

http://www.english.uiuc.edu/maps/poets/s_z/stevens/bio.htm

Thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird – notes [5]

http://edwardpicot.com/thirteenways/notes.html

Celtic Tree Alphabet (Ogham Calendar). [6]

https://orders.mkn.co.uk/tree/birthdaytree/$USD

Southworth, James G. Some Modern American Poets, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1950, p. 92.[7]

http://teenink.com/Past/2001/April/Books/13Ways.html

Oliver Postgate [8]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_Postgate

14th July – 9th September 07.

TheSpace4, Peterborough.

Summerbranch is a hyperreal cross-media woodland environment created by Igloo during a residency at Artsway Gallery in the New Forest in 2005. Installed across the three rooms of TheSpace4 gallery in Peterborough from 14th July – 9th September.

The first room contains lenticular prints, a non-interactive projection on one wall, and a suit of an extreme form of sniper camouflage that looks like some moss monster. This sets the scene for presenting an engrossing and haunted hyperreal landscape. That landscape consists of an archetypal woodland. Trees, rocks, ferns and water are scattered across a gently undulating leaf mould and moss ground.

This landscape is first presented as lenticular prints of a virtual scene. Whenever it appears, the level of detail of this virtual environment is astonishing. The SVGA data projectors used in the gallery and the ridges of the lenticular prints break the scene down into coarser pixels or bands than a modern widescreen monitor or high-resolution inkjet print could display it with. The richness of the textures and shading and the density of high-polygon modelling would seem obsessive if not for the convincing illusion of place that necessitates and follows from them.

Lenticular prints are popular with the creators of kitsch religious, commemorative and marketing items such as postcards and cereal box novelties. Consumer cameras capable of capturing the multiple images required to make lenticular prints have been available for decades. In the 1960s, Andy Warhol used large-scale lenticular prints of flowers as part of an installation. But unlike video and VR, there has been no popularization of Lenticular Print technology or techniques for popular production rather than popular consumption.

As you walk by the lenticular prints, they spin, pan, or zoom in and out. The effect is disorienting when the movement of the scene does not relate easily to your own movement. You have to adjust your movements to their framerate and dissociate what your eye sees from what you know your body is doing. You have to suspend your disbelief and accept the veracity of the imaginary scenes that the images present.

On the far wall, a video projector cuts slowly between scenes from what initially appears to be the same virtual environment as the lenticular prints. But it is a real wood, possibly the model for the renderings, recorded by a motionless video camera with a sniper costumed figure lurking in some of the shots. Its haunted emptiness makes it seem as unreal as its presumably inspired virtual environment. The thousands of tiny non-events of light motion and sound in calm woodland are hypnotic. The colours and motion are gentle and gradual, contrasting the harsher lenticular images. The prints and projection complement each other, redoubling the reality of the archetypical woodland(s) that they present.

I found that the walls of the middle room broke this effect. They are covered with wallpaper prints of the virtual forest scene rendered in layered low-resolution pastel-coloured pixels. I have spoken to several other people about the work in this room, all of whom have loved it, so possibly I have failed to see this work in some important way. That possibility raises its head again in my experience of the third room, although in a different way.

The third room is darkened and contains two wall-scale projections of Virtual Realities of the forest scene, one night and one day. Each has a plinth in front of it with a trackball and two buttons on it. Moving forward with one of the buttons is very smooth, but rotating with the trackball is unforgivably headache-inducing. This breaks the suspension of disbelief each time you look around. Fortunately, the visual and sonic richness of the world quickly envelops you again once you stop turning.

Virtual Reality (VR) emerged from late Cold War-era academic and military research. Summerbranch is not a training program for the European Theatre of World War 3, complete with Soviet Troops. It is a simulation of the New Forest, not the Black Forest, and it is at peace, apparently empty of human presence apart from the viewer. But it is haunted by the history of VR both technologically and by the presence of the sniper outfit in the first room.

Early VR systems from the 1980s used advanced display hardware linked to one or more minicomputers. By the early 1990s, cheaper custom hardware was available, and by the mid-1990s, VR was being created using internet-based software on stock personal computers. There were exhibitions of VR at the ICA in London, and excitement grew around the artistic use of the medium. But VRML 2, the HTML of virtual reality, destroyed any company that tried to implement it, and modem-bound internet users baulked at downloading hundreds of kilobytes of mesh and texture data for every location they visited.

Net-based VR and its artistic use had imploded by the end of the 1990s. “First Person Shooter” (FPS) games such as the Quake series surpassed older VR systems and software in power and popularity by the turn of the millennium. The VR torch is being carried by online environments such as Second Life that combine broadband download speeds with the ability to create new environments and objects within the software rather than expensive and cumbersome software intended for architecture or film use.

Using a single-person environment rather than an online VR system is not a technologically determined decision. As well as the unwanted destructive attentions of “griefers”, an online environment would draw other viewers who would destroy the solitude of the piece. There is little point in creating a gallery-based single-user work online, even if the rendering engine can do it. And Second Life currently would have trouble rendering all the details of Summerbranch. Artistic use of computing machinery should be based on the tools fitting the task, not artistic or technological fashion. Igloo has used the right technological tools for the artistic job.

If you are present when one of the environments has to be restarted due to your unseen avatar in the virtual world getting stuck on the edge of a hill polygon, you can see that the environment is rendered using Unreal Engine, a commercial FPS game engine. A decade ago, this kind of environment would not have been possible even with custom “Superscape” hardware.

Using multiple media to present the virtual scene as a complement to the recording of the real scene creates a hyperreal landscape. The reality of this is altered, but not interrupted, in the VRs by the motion-captured dance of moss-covered dancing female forms if you can find them among the foliage. Layer upon layer of invocation of nature, technology and mystery building up to produce the final effect of the work, which consists as much in what is absent as in what is present in it. This experience of the work is hard to put into words, which for a piece of art is a strong sign of its effectiveness.

I did not see the dancing female forms when I first used the VRs, and if the sniper/moss monster forms are in the VRs, I did not find them. Despite trying, I didn’t see them in the video projection on first viewing. Would my experience of the work have been any better if I had found them immediately? Would it have been any worse had I not found them at all? Would this have been a success or failure on the part of the artists or on the part of myself as the viewer? I do not have the answers to these questions, but I suspect that an interactive Fine Art context allows for a more varied, exclusive and hard-won experience than a game or an educational interactive context. Interactive aesthetics very quickly become interactive ethics.

Technically speaking, there is little new for the veteran of art virtual reality. What is new is the way that Igloo places Summerbranch in relation to contemporary art practice and to art history, not as a challenge but as a continuation. There is both a loss and a gain here. The loss is VR’s formal and experiential radicality as an artistic medium, a thread that I hope other practitioners will revive. The gain is a recognition of VR’s broader artistic value to the mainstream art practice, similar to that gained by photography as an art medium after the 1970s.

VR, video and lenticular prints are all low cultural, technological forms with long pedigrees. But they are still unfamiliar enough to have the appearance of modern technology and to surprise and interest people. All are ways of creating 3D illusions mechanically, and deploying them to create illusions of the same imagined world gives a more persuasive reality to that world.

Summerbranch succeeds spectacularly in making the hyperreal experience a rich contemplative encounter with the uncanniness of romantic nature, historical myth and rationalistic technology. This is a rich dialogue between the practices and histories of art and technology. And it is an engaging and meditative artistic spectacle.

Igloo are https://gibsonmartelli.com/works/

Workshops to create and film a drama promoting an enthusiasm for maths at Mayfield Primary School.

Participants: 28 children aged 8-9 years old from Mayfield Primary School

Artist: Michael Szpakowski (video artist, composer and facilitator)

In a series of workshops to promote an enthusiasm for maths within the school, a class of children aged 8-9 years old created and filmed a drama in 9 parts in which they cracked a series of knotty maths problems that they encountered during a school day. Pupils puzzle and ponder over how many minutes they have before they have to leave for school, how to organise rows and columns for school assembly, how it feels to crack a hard Maths problem. These short films, where we see the pupils trying to work out maths problems together, continue to serve as playful teaching tools within the school.

Partners:Creative Partnerships, Mayfield Primary School.

How Entropy8 and Zuper! became one: Entropy8Zuper!

3rd of April 2007, 7pm; I am standing outside a tall, narrow building in the centre of Gent, Belgium, waiting for Entropy8Zuper! to let me in. In that same morning, I talked to Auriea on the phone for the first time: our long relationship that developed online and took diverse manifestations –them the performers, me the audience; them the artists, me the curator; me the researcher, them the case-study…– was about to materialise. Our flesh bodies would soon be situated in the same actual space. On that morning it already took a voice: it was Auriea&s deep voice which I had heard before –but now, for the first time, it wasn’t computer-mediated.

The first time I saw a piece by Entropy8Zuper! was in 2001, at the Medi@terra festival in Greece (which I was co-directing at the time). That piece was Wirefire –and that was it… It meant I was hooked! I still have fading memories of “people without bodies mak(ing) love???1: I remember logging on my laptop on Fridays at about 1am (my time in Athens, Greece). I was there to watch the weekly performance of Wirefire that was on every Thursday night at midnight Belgium time for almost four years. The story behind Wirefire was about a couple, dispersed2, making love online, for and with audiences. Their act of virtual love-making was not a photorealistic representation of their encounter –it was love translated into audiovisual poetry: Auriea and Michael were mixing images, flash movies, animations, sounds, live streams and text files to create “compelling and seductive narratives???3 that all narrated the same story: “being digital and being in love???.4

Auriea opens the door. I see an elegant black woman, tall and slim, with long rasta locks, inviting me in what is both their house and studio. Michael is standing behind her: he is of about the same hight as her, also slim, white, with greying hair and what looks to me like a massive beard. Both seem to be in their late thirties or early fourties. Soon, we are sitting around a long dining table, on some funky, squeaky chairs. This is their living-dining room, simple, modern, and playful. There, over a few glasses of Bordeaux, Auriea and Michael talk to me for three hours about their art, life, and love-affair (which has a lot to do with both…).

How entropy8 and zuper! became one…

I have always been fascinated by Entropy8Zuper!’s love-story, which clearly was the inspiration for a lot of their early work. What I already knew was that they met and fell in love online while based in different countries (well, continents…), that they started working together while physically afar, and that they eventually decided to move in together. So Auriea gave up her life in NYC and moved to Belgium to live with Michael. But I didn’t know all the detail: Where and how did they meet? Did they fall in love at first (virtual) sight? What happened then? How difficult was it for both of them to decide to give up their lives for each other? Why is it that their work is so intrinsically interlinked with their love-affair?

“I guess it starts in Hell??? says Auriea. “What is she talking about???? I think. “I mean, in hell.com5??? she laughs. Oh god, that’s funny… What a semantically rich beginning to a career soaked in symbolism! Entropy8Zuper! have based a lot of their work (Godlove Museum, Wirefire) on allegory, and have used ‘grand narratives’ such as the Bible and folk fairytales as sources of inspiration. Auriea explains how she joined hell.com while Michael was already a member, how she knew and admired his work, and how they met there in January 1999 during a rehearsal for a collaborative, online video-performance using i-visit.6 Exactly how this happened is, Auriea says, “shrouded in mystery???.

Image from Godlove.

A: I had a web-cam running all the time –this is why I was interested, I had a streaming web-cam online. It was black and white and I used to do sort of informal online performances. So anybody who came to my web-page would see me sitting at my desk but sometimes I would do fun things with the camera. So when I showed up I was talking to Lia7 -do you know Lia? She is from Austria (…) And Michael didn’t have a web-cam so I remember he was broadcasting images of fruits and vegetables, ha ha! (…) maybe subconsciously I was attracted! (…) Yeah, that’s when we started talking and, I don’t know, it became sex-chat more or less instantly (…) which was odd because, you know, we don’t do that! Ha ha!

So it was love at first sight! And this –can you imagine?– despite the fact that Michael looked like a cauliflower!… That is how the roller-coaster of their relationship starts: the next day, Auriea says, Michael sent her an html page: “I was very excited and so I made one in return. It went back and forth like that, and that’s how skinonskinonskin got made.??? skinonskinonskin is E8Z!’s first piece. Not surprisingly, it talks about love, desire, and fantasies of sexual encounters. Originally, the piece was not even meant for audiences, it was only meant for each other. Until the hell.com server operator found the directory, ‘fell in love’ with the project, and suggested that they open it up to audiences… Eventually, E8Z! presented the piece during the hell.com pay-per-view event (September 1999): they charged audiences for admission to the skinonskinonskin website. The event was quite successful and any income generated was split between the hell.com collective.

Image from skinonskinonskin

After skinonskinonskin came Genesis (1999), chapter one of the Godlove Museum. This was while they were trying to suppress their online passion and just work together. Genesis was supposed to be their business website, “this totally animated crazy thing, you know?!??? shouts Auriea, and it was launched the same day they physically met for the first time:

A: (…) when we finally met in person, this occasion was complete fate in some ways… He was going to be in San Francisco, and I had to be in San Jose and I thought ‘this is ridiculous, we are going to be there in the same week’, you know… So I went to San Francisco, and that is where we met in person. We launched entropy8zuper.org the same day that we met! We met, we launched the site, and then we sat and…

M: …talked! Ha ha! Amongst other things..

A: At the Triton Hotel in San Francisco (…). We were very big on doing these kind of symbolic acts, like meeting in Hell for the first time and then launching the website the first time we met in person…

A lot of E8Z!’s work is autobiographical (skinonskinonskin, most of the Godlove Museum, Wirefire), in that it is centred around their private lives, their remote love-affair, and their dramatic get-together. “I think it was based on that very heavily??? says Auriea, “but we tried to get away from that after a while???. It seems that their love affair, while very romantic, was also quite traumatic for both of them: they were both in relationships and Michael had two kids; they lived in very different cities; they both had different lives and different visions of the future… Within a period of just a few months, they decided to abandon their separate lives in order to start a joint one. This was beautiful, but it was also painful, says Michael. This is why their work of that period is so self-referential: to them it functioned a bit as therapy. Some of it was even too personal or too painful to publish…