In 2019 we celebrate the 150th anniversary of Finsbury Park, and we time travel through its past and future with the launch of our Citizen Sci-fi programme and methodology. Dominant sci-fi franchises of our time, from Black Mirror to Westworld, have captured popular attention by showing us their apocalyptic visions of futures made desperate by systems of dominance and despair.

What is African-American author, Octavia E. Butler’s prescription for despair? Sci-fi and persistence. Sci-fi as a tool for getting us off the beaten-track and onto more fertile ground, and persistent striving for more just societies.The 2015 book Octavia’s Brood honoured her work, with an anthology of sci-fi writings from US social justice movements and this inspired us to try a new artistic response to the histories and possible futures of Finsbury Park.

Furtherfield’s Citizen Sci-Fi methodology combines citizen science and citizen journalism by crowdsourcing the imagination of local park users and community groups to create new visions and models of stewardship for public, urban green space. By connecting these with international communities of artists, techies and thinkers we are co-curating labs, workshops, exhibitions and Summer Fairs as a way to grow a new breed of shared culture.

Each artwork in the forthcoming exhibition invites audience participation – either in it’s creation or in the development of a parallel ‘people’s’ work – turning every idea into a portal to countless more thoughts and visions of the past and future of urban green spaces and beyond.

So where do we start? Last year we invited artists, academics and technologists to join us in forming a rebel alliance to fight for our futures across territories of political, cultural and environmental injustice. This year both our editorial and our exhibition programme are inspired by this alliance and the discoveries we are making together.

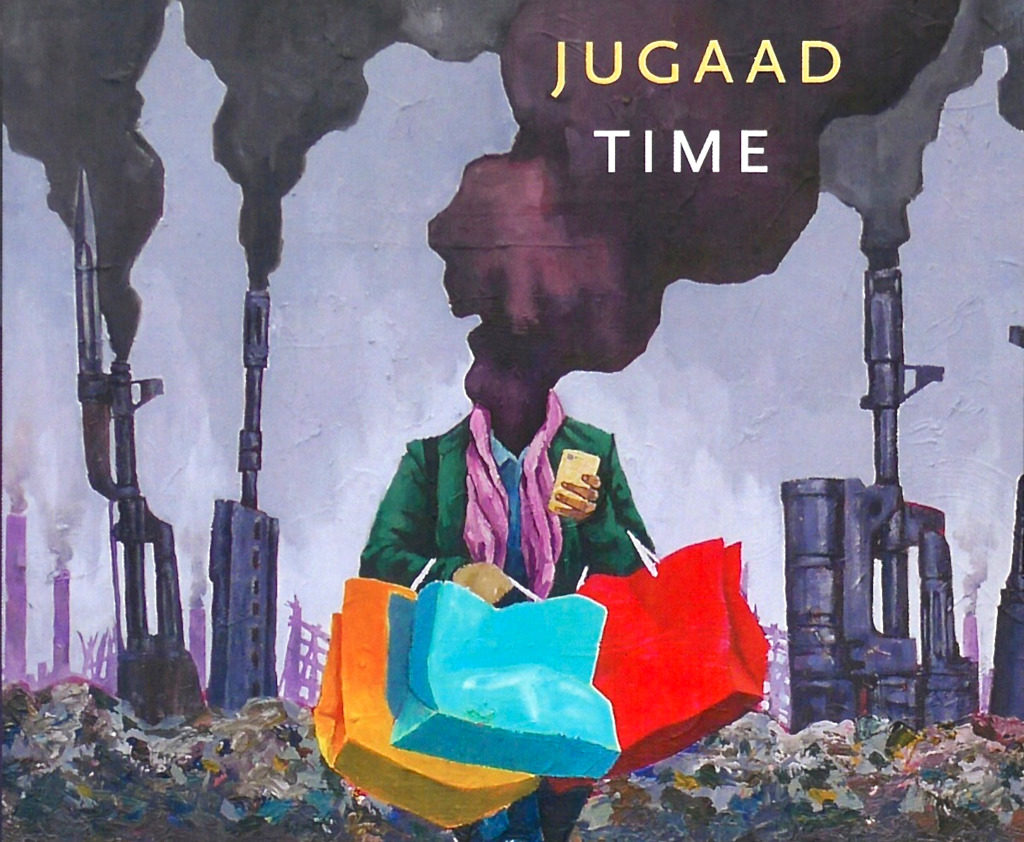

To kick off this year’s Time Portals programme at Furtherfield, in April we will host the launch and discussion around Jugaad Time, Amit Rai’s forthcoming book. This reflects on the postcolonial politics of what in India is called ‘jugaad’, or ‘work around’ and its disruption of the neoliberal capture of this subaltern practice as ‘frugal innovation’. Paul March-Russell’s essay Sci-Fi and Social Justice: An Overview delves into the radical roots and implications of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). This is a topic close to our hearts given our own recent exhibitions Monsters of the Machine and Children of Prometheus, inspired by the same book. Meanwhile we’ve been hosting workshops with local residents exploring our visions for Finsbury Park 150 years into the future. To get a flavour of these activities Matt Watkins’ has produced an account of his experience of the Futurescapes workshop at Furtherfield Commons in December 2018.

In May we will open the Time Portals exhibition which features several new commissions. These include Circle of Blackness by Elsa James. Through local historical research James will devise a composite character to embody the story of a black woman from the locality 150 years ago and 150 years in the future. James will perform a monologue that will be recorded and produced by hybrid reality technologist Carl Smith and broadcast as a hologram inside the Furtherfield Gallery throughout the summer. While Futures Machine by Rachel Jacobs is an Interactive machine designed and built through public workshops to respond to environmental change – recording the past and making predictions for the future while inspiring new rituals for our troubled times. Once built, the machine occupies Furtherfield Gallery, inviting visitors to play with it.

Time Portals opens on May 9th (2019) with other time traveling works by Thomson and Craighead, Anna Dumitriu and Alex May, Antonio Roberts and Studio Hyte. Visitors will be invited to participate in an act of radical imagination, responding with images, texts and actions that engage circular time, long time, linear time and lateral time in space towards a collective vision of Finsbury Park in 2169.

From April onwards, a world of activities, workshops with local families and their enriching noises, reviews, interviews and an array of experiences will unfold. Together we dismiss the dystopian nightmares and invite communities to join us in one of London’s first “People’s Parks” to revisit and recreate the future on our own terms together.

Marc Garrett will be interviewing Elsa James, about her artwork Circle of Blackness, and Amit Rai about his book Jugaad Time. Both will soon be featured on the Furtherfield web site.

On a blustery cold and wet Sunday in the build up to Christmas I joined a group of people at Furtherfield Commons to discuss the future of Finsbury Park. I finally arrived after prowling around their darkened Gallery in the centre of the park, only to discover the event was being hosted in their other space in the far southeastern corner of the park. This brief detour gave me a moment to breathe in one of my local parks and I experienced a familiar feeling of vulnerability as the night drew in and cold drops of rain started to make themselves felt. The few brave families and exercisers were beginning to retreat as I crossed the open stretch of field that runs parallel to the roaring Seven Sisters Road. Drawn by the welcoming light coming from the building in the small gardens behind the legendary Rowans Ten Pin Bowling and guided by the sound of the drumming, a regular feature of this corner of the park, I entered the workshop and was greeted with mince pies, tea and other goodies, and met the 11 other workshop participants.

Timed to coincide with the 150th anniversary of Finsbury Park, this workshop for local residents, aimed to tap into our experiences and imaginations to generate future visions of the park. The event was led by Dr Rachel Jacobs, who is a local with a special affection for the park, and she started by sharing it’s stories and describing some of the features that are no longer in existence including a bandstand and the many trees that have been removed over the years.

We started by identifying features of the park that we would like to ‘lose’ and those we wanted to ‘protect’. Answers were varied but along similar themes. Many people shared a desire to preserve the trees and if possible, have more. The lake featured prominently with many people wanting to maintain the space and the sanctuary it provides for birds. Rose, one of my fellow workshoppers, gleefully called for those people who feed bread to the ducks to be poisoned.

The underground reservoir, a cathedral-like temple to water supply was hailed as a hidden gem that could be utilised as a space during the colder months by Polly a local resident and manager of Space4. Simon, Chair of Friends of Finsbury Park, suggested we consider uses for Manor House Lodge (another building that had escaped my attention). Zeki prioritised the the rocks in the park for protection – especially at the amphitheatre space beside the play park. There were wistful expressions of personal connections to conkers, squirrels and swans. The things that people wanted to lose were more elusive: the atmosphere that the park creates at night; its association with crime and a lack of safety. Gab who overlooks the park from his 8th floor flat, feels the park can be scary and in his words, sometimes ‘sly’. Removing the fences was suggested as a possible remedy.

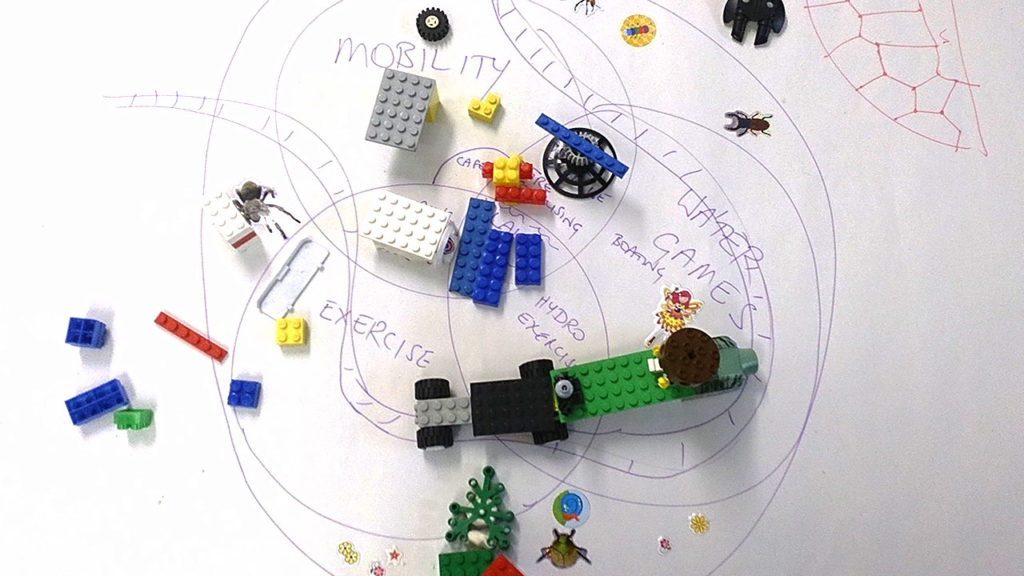

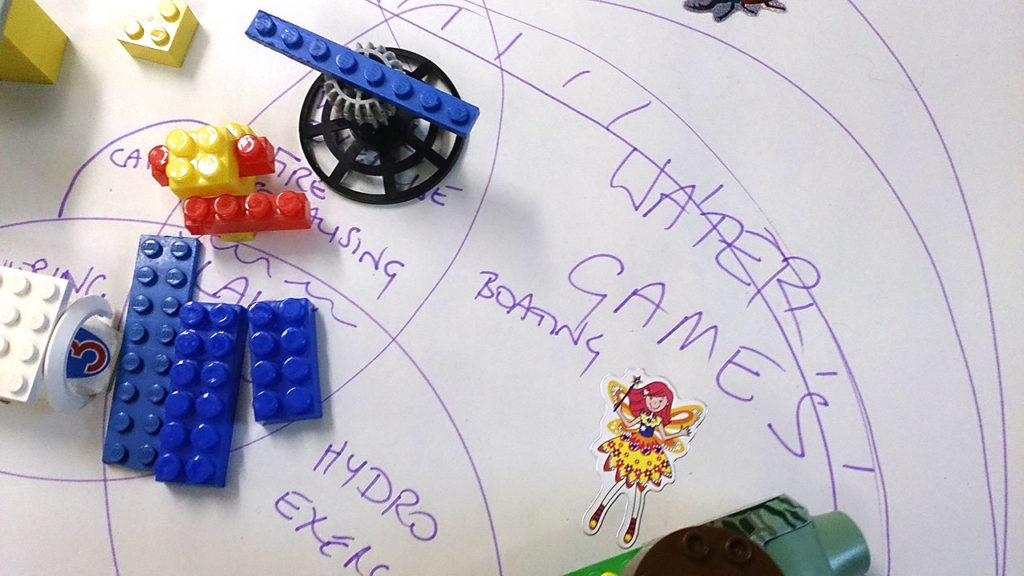

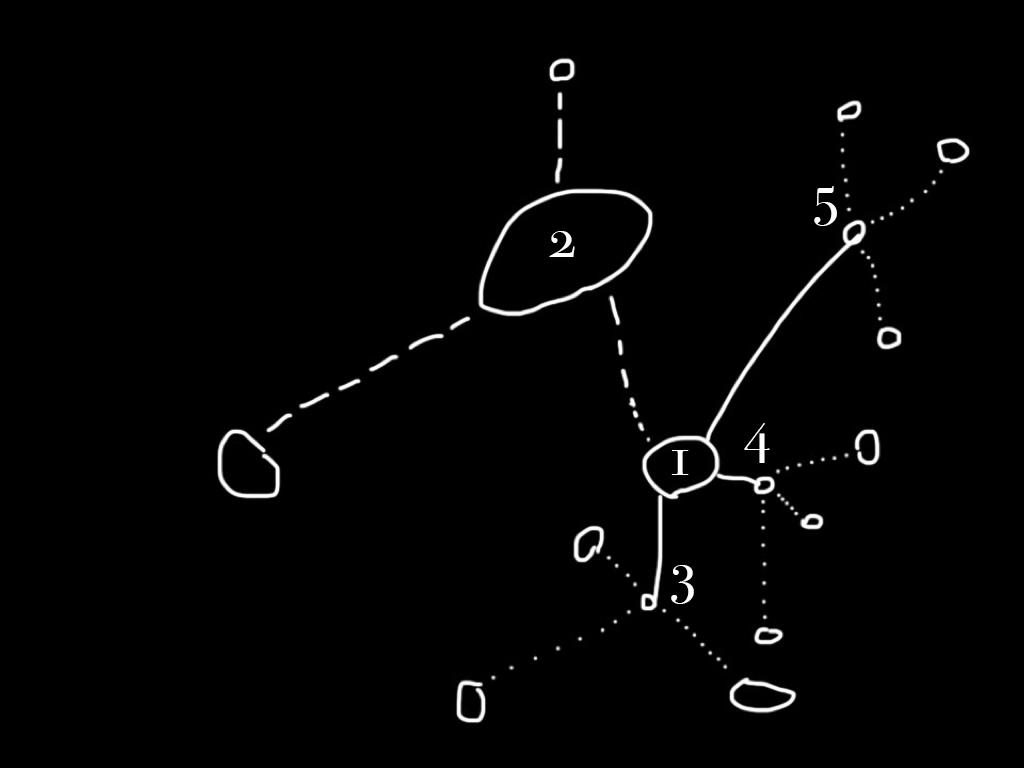

Next, we were introduced to an initially bemusing process based on Play Your Place, designed by artists Ruth Catlow and Mary Flanagan, to introduce playful and game-like activities to public consultation. We were each asked to select different cards with random words that we were told would help us to disrupt our conventional view of problem solving. The cards were divided into provocative statements, for example mine were: ‘London is no longer’ and ‘getaway car’. Then a spinning wheel contained words associated with game features, like ‘mission’, ‘protagonist’, ‘goal’ or ‘reward’. After drawing or writing out our scenarios based on the random words we had to pick a segment of the wheel in which to place our ideas.

I asked if London is no longer, why is that so? Perhaps the park has eaten London. I was making the park the protagonist, the hero of the story. My ‘getaway car’ card prompted me to imagine Finsbury Park criss-crossed by many roads. So what if a part of the park could move very slowly, a moving park that people could take in the rest of the park from and jump on and off.

Zeki, one of the youngest participants had the cards ‘maps‘ and ‘someone caring for the park’ they assigned it the wheel word ‘reward’. He imagined the rocks in the park could become an area where people could come and paint and draw on the rocks. People will be able to look at the drawings and climb on the rocks. He said this suited ‘reward’ because you get a nice place.

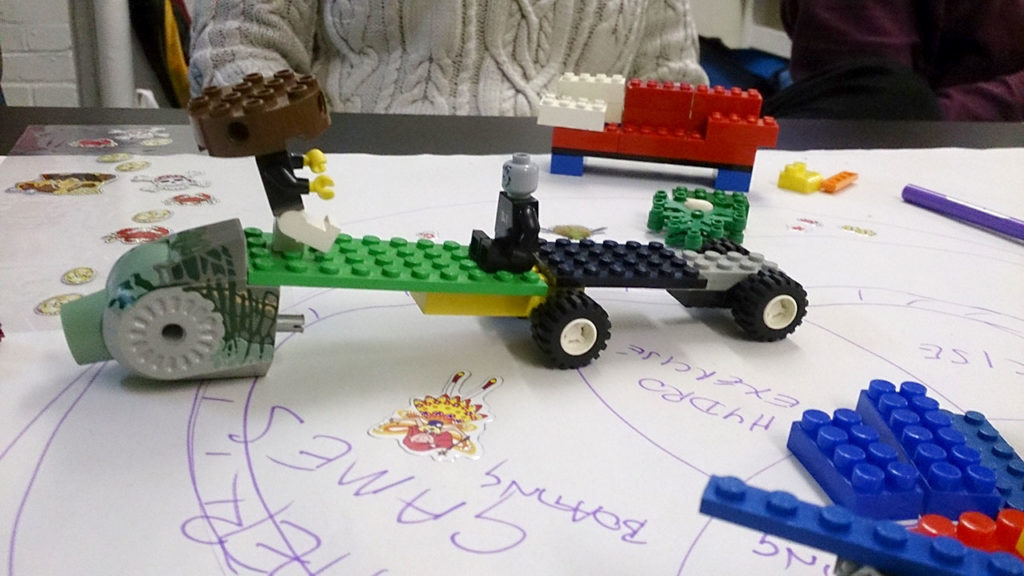

Finally we worked with lego and plasticine, felt and coloured paper, to make a representation of our scenarios. Time flew by before we were then asked to talk about what we had created.

Simon and Talal ended up using a lot of lego. They said they weren’t that confident ‘creating’ but their riotous explosion of lego pieces described the Finsbury Park Lodge with lots of tropical trees growing around them. They included a clocktower which they felt the park needed. Ominously on the edge of their diorama there was, in their words: ‘the threat of a forest fire’.

Ilenia and Gab created intricate visions of the park modelled from tiny pieces of plasticine. Ilenia created crosses to represent all the buildings that she was going to destroy. She said “All the fences will be replaced by nice trees. The lake will be larger than it is now. There will be more people using the park.” Gab described the a tree as becoming “a colourful multi-form creator. It will be very friendly and very different from normal. Everything will be very colourful and this will be linked to representing climate change.” Emma who earlier in the workshop explained her love of conkers ended up building robot conkers.

The outcomes were unexpected and realised in a wonderfully ad hoc way with a rich mix of ideas. Rachel and the Furtherfield team were on hand to support and provide more insight. Although the process of drawing cards and selecting from a wheel was initially quite perplexing, staying with the uncertainty of the process meant that we came up with ideas that were novel and unhindered by more formal or conservative notions of preserving or enhancing Finsbury Park. The two hour time limit, meant that everything moved along at pace that kept the idea generation restless. I believe I speak for all who took part in anticipating the results of the wider project.

What can possibly be made from such a kaleidoscope of raw material, I wondered on my way home in the pouring rain? Perhaps my plant car or Emma’s robot conkers will see the light of day or the darkness of the underground reservoir.

Futurescapes is an Innovate UK Audience of the Future Design Foundations project that uses Finsbury Park as a test case to examine the commercial potential for using immersive experiences as a tool for collaborative placemaking for public spaces and integrated public services. Furturescapes is a partnership project with Furtherfield, The Audience Agency and Wolf in Motion.

Join us in Edinburgh at the first DAOWO ‘Blockchain & Art Knowledge Sharing Summit’ of 2019

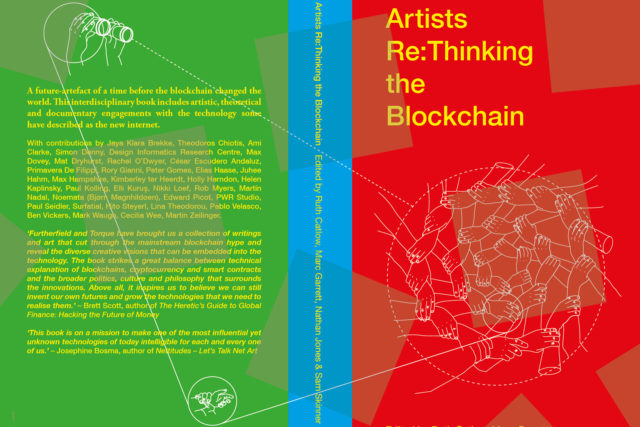

DAOWO (Distributed Autonomous Organisations With Others) Summit UK facilitates cross-sector engagement with leading researchers and key artworld actors to discuss the current state of play and opportunities available for working with blockchain technologies in the arts. Whilst bitcoin continues to be the overarching manifestation of blockchain technology in the public eye, artists and designers have been using the technology to explore new representations of social and cultural economies, and to redesign the art world as we see it today.

This summit will focus on potential impacts, technical affordances and opportunities for developing new blockchain technologies for fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies.

Programme

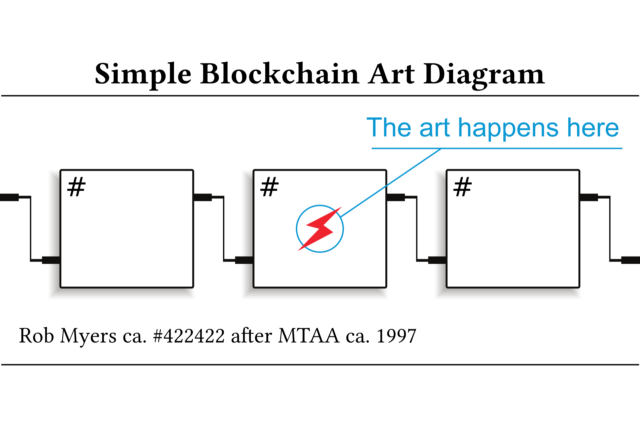

Although the term ‘blockchain’ has trickled downstream into the public domain, the principles behind the technology remain mysterious to many. Embodied within physical assemblages or social interventions that mine, hash and seal the evidence of human practices, creatives have provided important ‘coordinates’ in the form of artworks that help us to unpick the implications of the technology and the extent to which it re-configures power structures.

Hosted by Prof Chris Speed and Mark Daniels with panellists:

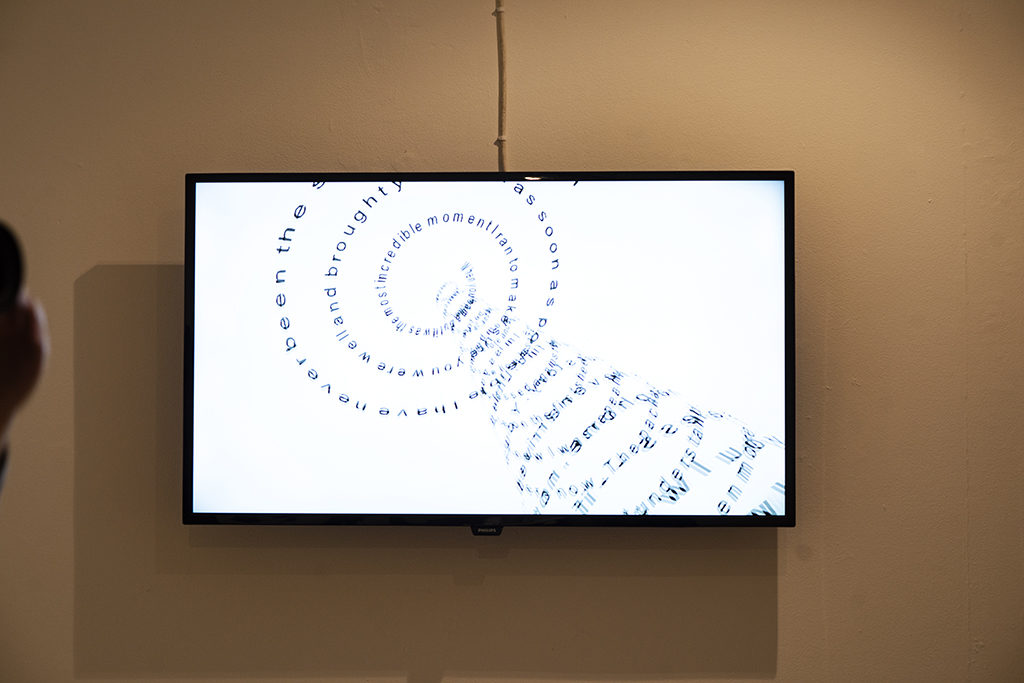

Pip Thornton – The Value of Words in an Age of Linguistic Capitalism

Bettina Nissen & Ailie Rutherford – Designing feminist cryptocurrency for Govanhill

Evan Morgan – GeoPact

Jonathan Rankin – OxChain, Pizza Block

Larissa Pschetz – Karma Kettles

Contributors include:

Ruth Catlow, Furtherfield and DECAL

Mark Daniels, New Media Scotland

Clive Gillman, Creative Scotland

Marianne Magnin, Arteïa

Prof Chris Speed, Design Informatics, University of Edinburgh

Ben Vickers, Serpentine Galleries

Through two UK summits, the DAOWO programme is forging a transnational network of arts and blockchain cooperation between cross-sector stakeholders, ensuring new ecologies for the arts can emerge and thrive.

DAOWO Summit UK is a DECAL initiative – co-produced by Furtherfield and Serpentine Galleries in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London. This event is realised in partnership with the Department of Design Informatics at the University of Edinburgh and New Media Scotland.

OxChain is a major EPSRC research project which explores how Blockchain technologies can be used to reshape value in the context of international development and the work of Oxfam, involving the Universities of Edinburgh, Northumbria and Lancaster.

“À la recherche de l’information perdue” was a performance that Cornelia Sollfrank contributed to the ‘Post-Cyber Feminist International’ event at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London.1 The event in November 2017 marked the twentieth anniversary of the First Cyberfeminist International (documenta X, Kassel, Germany, 1997) organized by the Old Boys Network, paying homage to its productive format and legacy. In her own words, Sollfrank set out to offer an “one-hour lecture performance that makes a (techno-)feminist comment on the entanglements of gender, technology and information politics,” with the rationale that “with the technological landscape vastly changed since the first Cyberfeminist International, we are living in a time well beyond the imagined future of the early cyberfeminists. Expanding upon this particular genealogy, this convening purposefully constellates thinkers to consider a new vision for “post-cyberfeminism” that is substantive and developed, without being exclusionary of contestation.”

I was surprised at the invitation of the charismatic woman I came to know as “Coco” to attend her performance. My surprise, which I bet is going to surprise Coco in turn, was due to two reasons. I had published two academic papers on WikiLeaks (2012, 2014 with Robinson), later included in a monograph charting on digital activism from 1994-2014 (2015), and at the time I was working on another paper on ‘Leaktivism and its Discontents’ examining the DCLeaks, CIA Vault7Leaks and DNCLeaks (2018). Although I took a critical view of the ideological and organizational conflicts within WikiLeaks as an organization internally, and examined the impact of that organization externally on academic debates in three disciplines between 2010-2012, and followed the leaks religiously in my scholarship, I had not written or commented on the rape allegations against Julian Assange.2 The related legal requirements, however, were what forced him to be stranded in the Ecuadorian Embassy from the 12th of June 2012 to the time of writing in 2018, in the first place. On March 6th, 2016, I was one of the signatories urging Swedish and UK Permanent Representatives to the United Nations in Geneva, to respect the United Nations’ decision to free Julian Assange. Moreover, as my work almost in its entirety has not focused on gender aspects of technology, or gender studies (apart from say examining ethno-patriarchal racist ideologies in anti-migrant discourses on digital networks in 2010-2013 for the Project, see et al. 2018),3 I felt rather intrigued by the invitation to the event, and its technofeminist context and agenda. If Coco was brave enough to invite me to watch her performance and trust me to comment on it, considering both my research (see references), and critical but supportive stance to Julian Assange’s quest for freedom, then I had to also be brave enough to take up the challenge!

As academics we are encouraged not to write in the first person. In fact, “do not use the first person in your scholarship” is served up in higher education establishments around the world, bar in certain sub-disciplines who take a certain pride in reflecting on the situated knower and their reflective positionality. In my own scholarship, I have used the first person sparingly. Here, in this text however, I feel obliged to do so, as I watched an artist perform and I would like to convey the thoughts aroused in the internal empire; and also understand whether and if so, how it has transformed me. After all, that is what art is for, right?

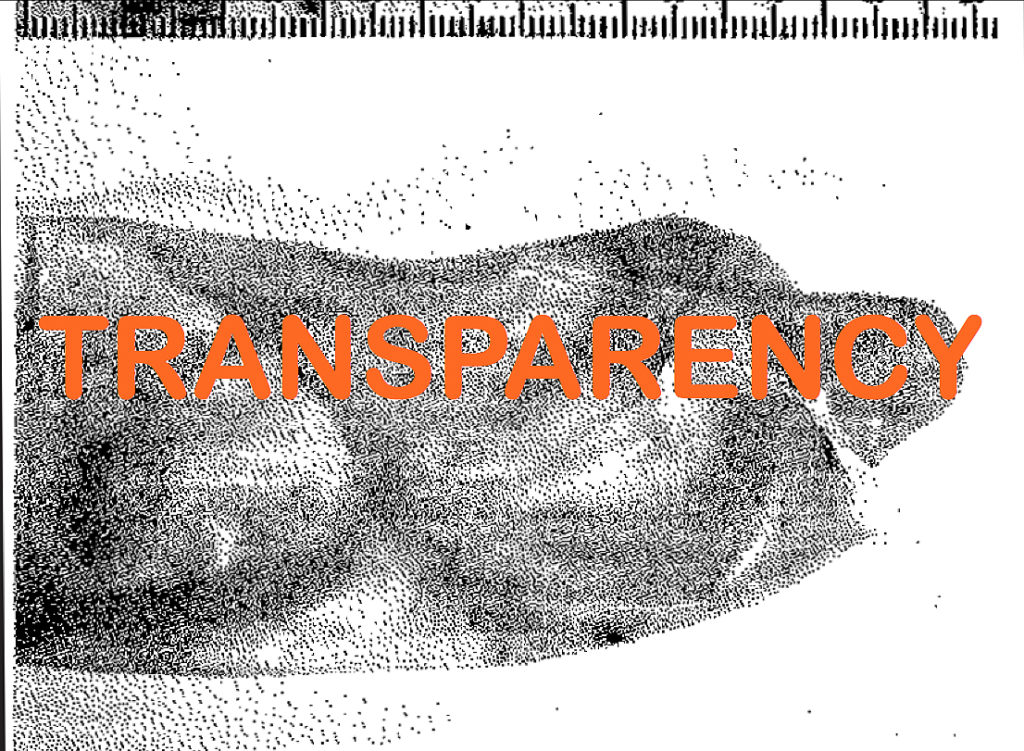

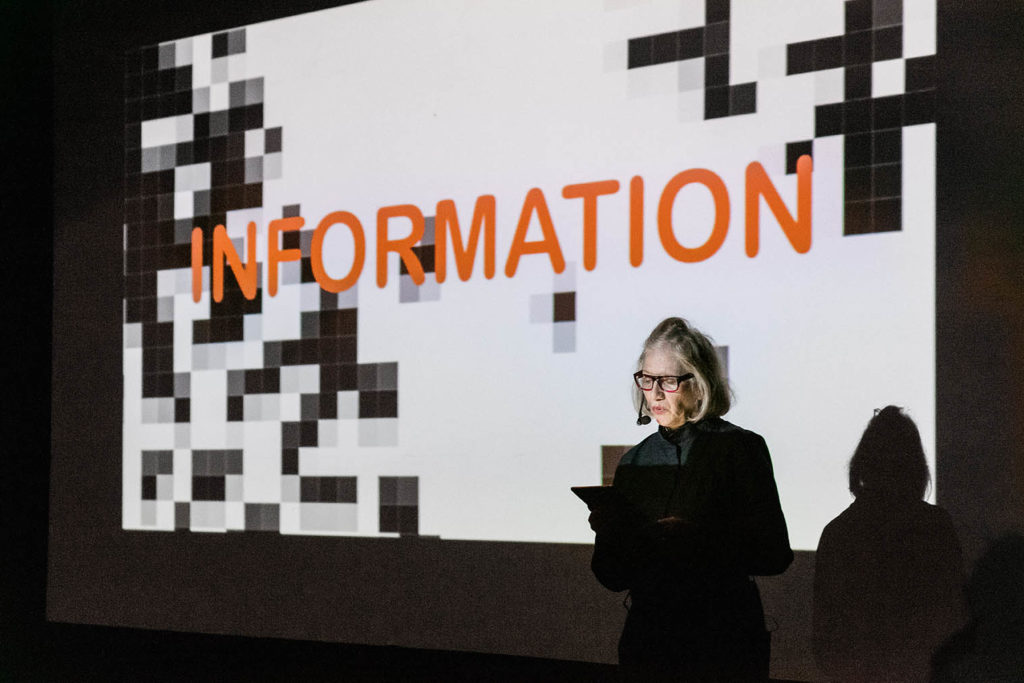

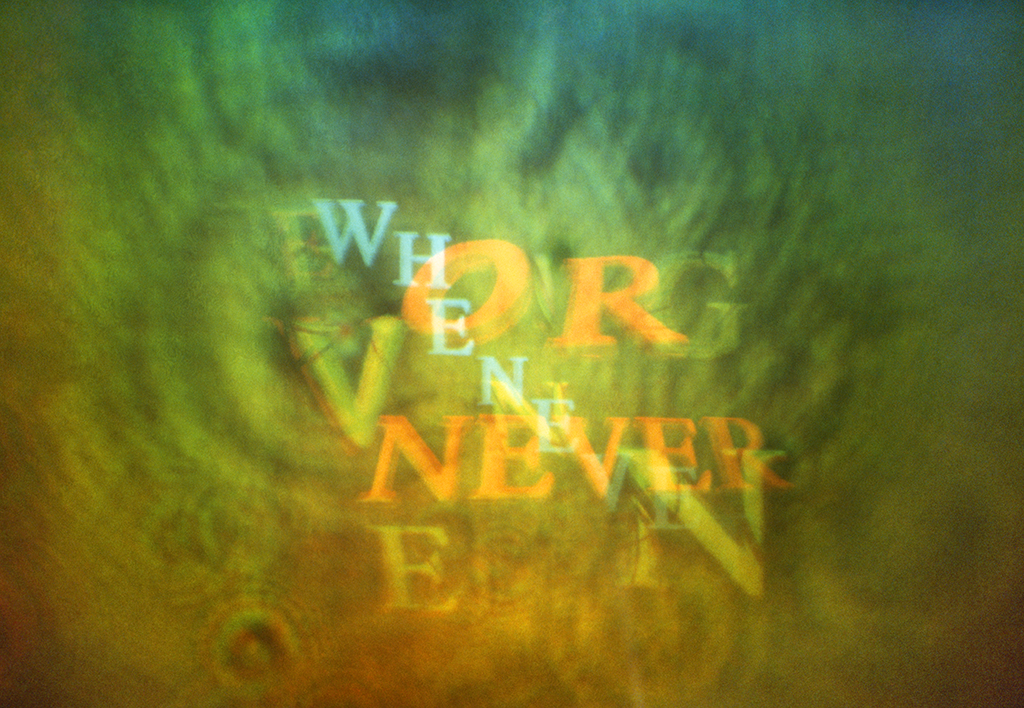

Sollfrank’s performance consists of her reading a text, overlaid by electronic sounds, and the projection of changing images behind her. There are nine images: orange font capital letters on a black and white pixel background: INFORMATION, ORGANISATION, ZEROS+ONES, BINARY WORLDS, PURE DIFFERENCE, CYBERFEMINISM, GENDER+TECHNOLOGY, NAKED INFORMATION, TRANPARENCY. The first image background is a very close zoom in to a black-and-white image and each image background zooms out to the final one. Only the last two images reveal the subject of the image: the photograph of the ripped condom used by Julian Assange during sexual intercourse with one of the women that subsequently accused him of rape, table by the Swedish police and published in their report. This was the final image of her lecture below.

The structure of the lecture is an assemblage really of separate elements she uses to launch her critique. In introducing her performance, she asks:

“On the road to freedom, one has to make sacrifices; but what remains when the way gets swampy and forks into affective structures? Rape can be performed in many ways.

So, what is missing? What are we looking for?

Has it been lost at all? Maybe it just multiplied, and stayed a much as it has gone away? Who knows?

We all create reality collectively and long ago have become zombies of transparency.”

Here, already I am baffled by the sentence “Rape can be performed in many ways.” I hadn’t thought about the “performativity” of rape. I make a mental note of this. Who “performs” during a rape? Can you perform before, during, or after a rape? What are the “many ways” a rape can be performed? This thought grabs me immediately at the start of her performance. But I relieve myself of it, thinking I got to be self-policing: this is the kind of thought that gets you into hot water: she must mean either literally the various categories of rape in Sweden, or this is some kind of allegory on reactive affect, discursive violence, a form of sexual misconduct, or again literally the case of broken trust found in a broken condom? I don’t have time to think, as Sollfrank swiftly moves on to the first section “INFORMATION,” where she talks about theoretical approaches to information: structure, knowledge, signal, message, meaning, process. In the sentence,“Julian Assange is accused of rape,” the information is coded in words and letters, the meaning of that structure is conveyed and at the pragmatic level, the receiver finds value in that information depending on whether he/she is interested in this person, his organization, what he represents, subjectively decoding this information to create meaning. The next piece of the puzzle is, of course, “ORGANISATION.” Sollfrank quotes the WikiLeaks organisation mantra: “One of our most important activities is to publish original source material alongside our news stories so readers and historians alike can see evidence of the truth.” Assange faced criticism for his centralised style of leadership in the organisation, which caused people to leave it. And obviously his political aims are somewhat inconclusive. Here, in this part of the lecture, I recognise my own writing, when Sollfrank says: “Maybe, the man and his organisation are an empty signifier, filled ideologically to reflect the discursive mood of anyone.” I had made that argument in ‘WikiLeaks Affects’ (2012), analyzing the diverse actors who supported Assange and the public feelings of him as a traitor or hero, the overflow of affective structures and the acceleration offered by digital networks (digital materialisation of the revolutionary virtual that may or not happen in the real).

But Sollfrank extends this argument by asking: “Why do they all express their particular feelings, even though these are uniformly rooted in their own individual causes and systems of belief?” Yes, what is at stake when Assange’s organisation jump-scaled globally after the release of the Collateral Damage video in 2010? Would the strong tradition of the women-protective Swedish state have taken on the same exact legal process for someone less than Assange? Letting him leave for the UK, after a police station visit, but then after the leaks occurred, recall him for further questioning? The saga between the Swedish government and Assange,culminated in Swedish prosecutors dropping their investigation into Assange, bringing to an end a seven-year legal standoff on May 19, 2017.4 In February 2018, a judge, nevertheless, upheld the warrant for his arrest. On 28 March 2018, Ecuador cut Assange’s Internet connection at its London embassy refuge “in order to prevent any potential harm,” caused by his social media posts denouncing the arrest of a Catalonian separatist leader, which Ecuador officials claimed “to put at risk” Ecuador’s relations with European countries. Assange might well be an obnoxious bastard to whom rape charges might be thrown at and dropped, but he becomes a target for Sollfrank for another reason…

This is where the performance goes SURREAL. Of the ONE and ZERO, Sollfrank makes beautiful poetry of this, in her “BINARY WORLDS” section:

“The man is the ONE, and ONE is everything. And the female has nothing you can see. Woman functions as a hole, a gap, a space, a nothing that is not the same, identical, identifiable, … a fault, a flaw, a lack, an absence outside the system of representations and auto-representations. Lacan lays down the law and leaves no doubt when he syas: ‘There is woman only as excluded by the nature of things. She is not “all,” “not whole,” “not-one,” and whatever she knows can only be described as “not-knowledge.” There is no such thing as THE woman, where the definite article stands for the universal. She has no place like home, nothing of her own, other than the place of the Other which,” writes Lacan, “I designate with a capital O.”

And it remains up to us, the audience, to make the association she would never express herself: the ONE mal god, is it him?

In “PURE DIFFERENCE,” Sollfrank finally gets irritated herself! “ONE, the definite, upright line; and ZERO the diagram or nothing at all: penis and vagina, thing and hole; a perfect match… Now the only thing that counts is whether there is something to see, and there seems to be something missing with the Zero. What makes the <woman> in this respect? …Why not admit that we are as blind for the invisible sexual difference as between a Zero and a ONE, because we always have to see pictures and that means something else?”

“CYBERFEMINISM” is brought in to help answer some of the questions here, but its focus has been how to use technology to fight “Big Daddy Mainframe,” technology as a way to dissolve sex and gender. The cyberfeminist techno-utopian expectations did not digitally or otherwise materialise, and Sollfrank asks: “What is between your legs NOW? Zeroes and ones? Liberated data? Digital slime? The warm machine still awaits your intention, but never forget the flesh.” What Sollfrank goes on to declare in “GENDER & TECHNOLOGY” is that “Big Daddy rules supreme.” That is my least favorite part of the lecture. Yes, engrained spheres of masculinity are still ubiquitous within all techno-cultures, and Sollfrank offers the GamerGate example with men harassing women, trolling, doxxing, cyberstalking, intimidation and policing experienced by women and queers are real. Indeed.

But here’s also where the binary lures to manifest itself. Extending Assange’s obnoxious techno-geek persona accused of rape and making him the master signifier of patriarchy reproduced in digital networks and especially technoculture would in turn reproduce exactly the same that fills the empty signifier Assange with the baggage of their own beliefs. Watch out and not fall into the same trap here, although it might be beautiful just to fall.

Sollfrank’s contribution here is really not on Assange’s signifier as a male God of ONE the personification of toxic masculinity, it is more her critique of his ideology of TRANSPARENCY, in the last section of her performance.

The inconvenient question remains, what information at which moment and from whom? If it is not related to a political goal, transparency becomes an end in itself – an ideology, and we: its zombies. With transparency as the new imperative: How do we distinguish … between accountability, surveillances and privacy invasion? Liberating public data and protecting private ones? All data are made of similar substance and follow the same logic; who might be able to stop the flow, once it is flowing? Who would want to interrupt the continuum, to crack and leak and disrupt the flow – of capital? No way!

The performance finishes with “Naked information is incapable of generating a myth, I live off that which others do not know about me. And will I ever know myself? In contrast to calculating, thinking is not self-transparent. There is nothing more intransparent than the subject to herself – no matter how much data I have and share. Information is just information, only once you know what you are looking for, the search can begin.”

Sollfrank’s performance approached information from all the sides she started with: structure, knowledge, signal, message, meaning, process. I had to reflect on why I never wrote about the Swedish case in all the scholarship I developed on WikiLeaks over the years. I felt Assange is an easy target to be used as a prop to talk about sexism reproduced in digital networks, techno-patriarchy and cyberfeminism, filling him in as an empty signifier to whatever the pet subject and the ideological discursive purpose happens to be. And yet, I think here Sollfrank does something brilliant, bringing a picture of the ripped condom as a background to her red-font words. Because she is connecting meanings to structures, material, affective, digital and interrogating trust, extending to the trust that a condom should not be ripped, interrogating the winner takes all justification register of transparency as an ideology, surveillance as the normal, and the end of secrecy, the quest of truth at all costs, even disrupting democracy, even the neoliberal capitalist kind. When there is no true self, even in itself, the search for lost information can be the point or utterly pointless, the same way as ZERO and ONE. This is what Sollfrank I think transformed with her art in my (post-cyberfeminist?) soul machinery.

Link to most recent performance at the hacker convention 35c3 in Leipzig:

1 https://www.ica.art/whats-on/season/post-cyber-feminist-international

2 https://diem25.org/urging-sweden-and-the-uk-to-free-julian-assange

4 https://www.theguardian.com/media/2015/oct/12/timeline-julian-assange-and-swedens-prosecutors

Associate Professor in Media and Communication at the University of Leicester. Her work contributes to theorising cyberconflict, and exploring the potential of ICTs and network forms of organization for social movements, resistance and open knowledge production.

artist, researcher and university lecturer, living in Berlin (Germany). Recurring subjects in her artistic and academic work in and about digital cultures are artistic infrastructures, new forms of (political) self-organization, authorship and intellectual property, techno-feminist practice and theory. She was co-founder of the collectives women-and-technology, – Innen and old boys network, and currently is research associate at the University of the Arts in Zürich for the project ‘Creating Commons.’ Her recent book Die schönen Kriegerinnen. Technofeministische Praxis im 21.Jahrhundert was published in August 2018 with transversal texts, Vienna. For more information, pls visit: artwarez.org

In thinking about the relationship between science fiction and social justice, a useful starting-point is the novel that many regard as the Ur-source for the genre: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). When Shelley’s anti-hero finally encounters his creation, the Creature admonishes Frankenstein for his abdication of responsibility:

I am thy creature, and I will be even mild and docile to my natural lord and king, if thou wilt also perform thy part, the which thou owest me. … I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, who thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. … I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.

Popularly misunderstood as a cautionary warning against playing God (a notion that Shelley only introduced in the preface to the 1831 edition), Frankenstein’s meaning is really captured in this passage. Shelley, influenced by the radical ideas of her parents, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, makes it clear that the Creature was born good and that his evil was the product only of his mistreatment. Echoing the social contract of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the Creature insists that he will do good again if Frankenstein, for his part, does the same. Social justice for the unfortunate, the misshapen and the abused is what underlies the radicalism of Shelley’s novel. Frankenstein’s experiments give birth not only to a new species but also to a new concept of social responsibility, in which those with power are behoved to acknowledge, respect and support those without; a relationship that Frankenstein literally runs away from.

The theme of social justice, then, is there at the birth also of the sf genre. It looks backwards to the utopian tradition from Plato and Thomas More to the progressive movements that characterised Shelley’s Romantic age. And it looks forwards to how science fiction – as we would recognise it today – has imagined future and non-terrestial societies with all manner of different social, political and sexual arrangements.

Shelley’s motif of creator and created is one way of examining how modern sf has dramatized competing notions of social justice. Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot (1950) and, even more so, The Caves of Steel (1954) ask not only the question, ‘can a robot pass for human?’, but also more importantly, ‘what happens to humanity when robots supersede them?’. Within current anxieties surrounding AI, Asimov’s stories are experiencing a revival of interest. One possible solution to the latter question is the policing of the boundaries between human and machine. This grey area is explored through use of the Voigt-Kampff Test, which measures the subject’s empathetic understanding, in Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) and memorably dramatized in Ridley Scott’s film version, Blade Runner (1982). In William Gibson’s novel, Neuromancer (1984), and the Japanese anime Ghost in the Shell (1995), branches of both the military and the police are marshalled to prevent AIs gaining the equivalent of human consciousness.

Running parallel with Asimov’s robot stories, Cordwainer Smith published the tales that comprised ‘the Instrumentality of Mankind’, collected posthumously as The Rediscovery of Man (1993). A key element involves the Underpeople, genetically modified animals who serve the needs of their seemingly godlike masters, and whose journey towards emancipation is conveyed through the stories. It is surely no coincidence that both Asimov and Smith were writing against the backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement, but it is also indicative of the magazine culture of the period that both had to write allegorically. In N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy (2015-7), an unprecedented winner of three successive Hugo Awards, the racial subtext to the struggle between ‘normals’ and post-humans is made explicit.

Jemisin, like Ann Leckie’s multiple award-winning Ancillary Justice (2013), is indebted to the black and female authors who came before her. In particular, the influence of Octavia Butler, as indicated by the anthology of new writing, Octavia’s Brood (2015), has grown immeasurably since her premature death in 2006. Butler’s abiding preoccupation was with the compromises that the powerless would have to make with the powerful simply in order to survive. Her final sf novels, Parable of the Talents (1993) and Parable of the Sower (1998), tentatively posit a more utopian vision. This hard-won prospect owes something to both Joanna Russ’s no-nonsense ideal of Whileaway in The Female Man (1975) as well as the ‘ambiguous utopia’ of Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed (1974). Leckie, in particular, has acknowledged her debt to Le Guin, but whilst most attention has been paid to the representation of non-binary sexualities in both the Ancillary novels and Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), what binds both authors is their anarchic sense of individualism and communitarianism.

Whilst sf has, like many of its recent award-winning recipients, diversified over the decades, there is little sense of it having abandoned the Creature’s plaintive plea in Frankenstein: ‘I am malicious because I am miserable.’ It is the imaginative reiteration of this plea that makes sf into a viable form for speculating upon the future bases of citizenship and social justice.

When I first heard about MoneyLab, it was back in 2013 or the beginning of 2014, when I was doing my masters in London. A friend of mine handed a flyer to me and I was intrigued by the strange typography and the combination of bright colours. However, I didn’t quite believe that any kind of initiative could really start an alt-economy movement. Not that I didn’t believe in local currency or creative commons, but those gentle approaches generally seemed to lack traction, just like liberals do with voters. I naturally thought MoneyLab was one of those initiatives.

However, as Bitcoin was becoming a hype, the name popped up again; MoneyLab itself was also becoming a hype. While bitterly regretting not being able to be associated as the first wave of participants, I started to think that maybe MoneyLab might be the framework that can really push out alternative economic attempts as mainstream culture. My stance towards economic shifts was somewhat similar to that of William Gibson’s; he said in an interview with the British newspaper The Guardian, ‘What would my superpower be? Redistribution of wealth’. How did that change after reading the MoneyLab Reader 2?

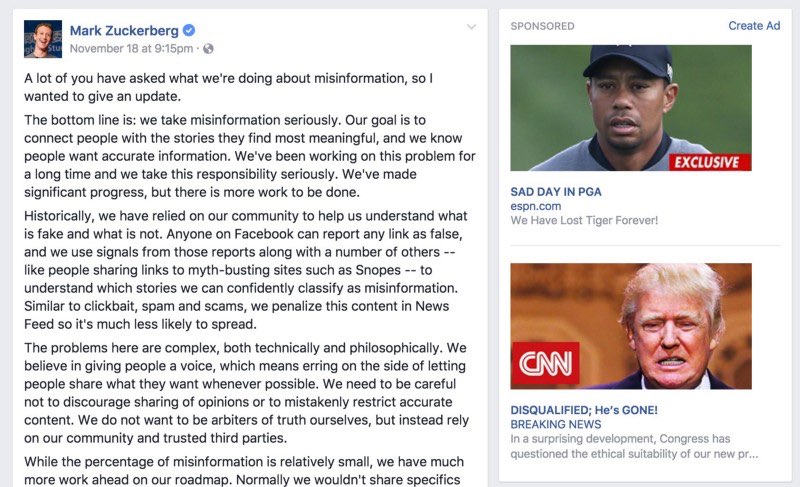

Before going into the details of what blockchain technology can really do, it is crucial to understand a new “unit of value” created in modern society (Pine and Gilmore 1999). Since the most prominent piece of technology of our era is undoubtedly smartphones (with Apple being the first 1 trillion dollar publicly listed company in the US), a lot of transactions are inevitably conducted through apps and web services. The proliferation of the so-called “payments space” signifies the era of UX design, which is the third paradigm of HCI (Human-Computer Interaction), “tak[ing] into account…affect, embodiment, situated meaning, values and social issues” (Tkacz and Velasco 2018). In other words, experience has become the deciding factor of customers’ choices. With vast amounts of data generated at the back of sleek interfaces, one can precisely oversee the users’ behaviour, which then is fed back into the system.

All the payments spaces are essentially digital. This means transactions leave digital traces whether you like it or not. The idea of a cashless society exactly stems from this interest, the authorities can have better understandings of how people make money; in other words, where black money flows. Brett Scott has been pointing out the danger of a cashless society for quite some time now, I saw another variation in this book.

According to Jaya Klara Brekke, blockchain technology can make money programmable, “allow[ing] for very fine-grained (re)programming of the medium of money, from what constitutes, and how to measure, value-generating activity to the setting of parameters on the means and conditions of exchange – what is spendable, where and by whom” (Brekke 2018). The overall impression I got from the MoneyLab Reader 2 about what blockchain technology can really do is basically this. Making a currency programmable using smart contracts.

More than a couple of authors discuss how “contingency” should take place in designed currencies. Contingency is different from randomness; in fact, it could mean exactly the opposite. For example, when coins are distributed in a perfectly random manner, you have absolutely no control in the handling process. If contingency is embedded in a system, it means there are exploitable gaps, which seem to almost randomly benefit people. On the other hand, some individuals would find ways to make use of these gaps, which are considered to be legitimate. Brekke discusses how the way in which contingency is programmed into a currency will be a key for the future of finance, both in terms of experience and redistribution of wealth. Therefore, currency designers will be the next UX designers.

A number of ideas applying blockchain technology to both physical and cultural objects are mentioned in this book, from a self-maintaining forest to blockchain-based marriage. “Terra0” is the concept of an autonomous forest which can “self-harvest its own value” (Lotti 2018). Utopian views of a human-less world are prevalent, but in reality, a healthy forest requires an adequate amount of human intervention. In addition, the value of a forest cannot be determined by itself; trade routes, demand and supply, they are all drawn by human movements. For example in Japan, domestic wood resources are generally not profitable because of the expensive labour costs. Illegally cut trees without certification from Southeast Asia dominate the market, putting domestic ones in a bad position. When a forest itself is not profitable, how can it accumulate capital autonomously? Besides, the oracle problem has not been discussed at all. Unless everything is digital in the first place, there always needs to be somebody to put data onto the blockchain. In other words, the transcendence of the boundaries between the physical and the digital is not possible without human intervention. Blockchain marriage would face a similar problem; who might be the witness if circumventing the government official? Max Dovey investigates the notion of “crypto-sovereignty” while introducing an example of a real blockchain marriage where they “turn[ed] ‘proof of work’… into ‘proof of love’”(Dovey 2018). Just as the sacramental bond between spouses can be broken before Death Do Them Part, so can any cryptographic marriage unravel despite having been recorded in an immutable ledger. Whatever repercussions may exist for divorce, there are no holy or technological mechanisms to prevent it.

Platform co-ops is one of the largest topics in the book besides Universal Basic Income (UBI). A platform co-op is often a cooperatively owned version of a major platform that is supposed to be able to pay better fees to the workers. Also, a platform co-op is often associated with “lower failure rate”; 80% of them survive the first five years when only 41% of other business models do (Scholz 2018). While embracing the positive aspects of platform co-ops, I have this question stuck in my head: can you not make a platform co-op based on a new idea rather than copying existing ones?

Most platform co-ops seem that they are looking at already successful and established concepts such as rental marketplaces for rooms and ride hailing services. As a result, platform co-ops are considered more to be a social movement than an innovation. Why not just run a business right at the centre of Capitalism without being motivated by profit? Many platform co-ops challenge the main stream services such as Airbnb or Uber, however those services operate based on scale; if they have the largest user base, it will be very difficult to take them on, unless they die themselves like Myspace… Moreover, more hardware side of development can be happening around co-ops, but I don’t hear anything except for Fairphone. When can I stop using my ThinkPad with Linux on it?

After reading the MoneyLab Reader 2: Overcoming the Hype, now I’m thinking of how I should design my own currency. Of course whether cryptocurrencies are actually currencies is up to debate; depending on who you ask, Ethereum is a security (SEC), a commodity (CFTC), taxable property (IRS) or a currency (traders).

MoneyLab 2 authors overall suggest that we should not limit our imagination to fit in the existing finance systems, but think beyond. You don’t necessarily need to cling to cryptocurrencies but they may help you shape your ideal financial system.

Futurescapes connects local groups with our wider team of designers, researchers, techies and visionaries, to co-create new visions of Finsbury Park using immersive technology.

Furtherfield disrupt and democratise arts and technology so that more people can be involved in the business of shaping their cultures and places. Our current focus is on ways to connect the governance and funding of culture to the communities that they serve.

We are currently developing a three year programme called Citizen Sci-Fi, in the heart of Finsbury Park where we have 2 venues: a gallery and a lab. Using the model of citizen science and citizen journalism we are crowdsourcing the imagination of park users and local community groups to create new visions and models of stewardship for public, urban green space.

Like many other public spaces, Finsbury Park has immense economic, social and natural value, yet there is a disconnect between the ‘owners’ of public space and the people that use (or should be) using them. Local councils have limited funds, the ‘superdiverse’ local population are not engaged in public consultations; and there are conflicts between park users and stakeholders.

Immersive models can be used as a tool for engagement through co-design, to discover how the council, park stakeholders including nearby property developers, and park users imagine its future and their involvement with it. Placemaking is recognised as a core part of regeneration, requiring a foundation of strong partnerships cutting across the public and private sectors, where social, cultural and ‘natural’ capital interleave to create stronger bonds and local identity.

We aim to co-design an immersive platform to facilitate the co-design of development in and around public spaces. It will engage with and directly benefit a number of stakeholders:

By coordinating and connecting Furtherfield’s international community of artists, techies and thinkers, and the groups that we work with in Finsbury Park, we have the opportunity to combine the powerful insights of grounded communities with experimental practitioners. We want to find a way to empower a long term collaboration across all these layers.

Futurescapes is an Audiences of the Future Design Foundations project, funded by Innovate UK (part of UK Research & Innovation)

ART AFTER MONEY, MONEY AFTER ART is a workshop with Max Haiven, author of Art After Money, Money After Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization.

In a world turned into a casino is it any wonder that corporate gangsters increasingly run the show? What are the prospects for a democratization of the economy when new technologies appear to further enclose us in a financialized web where every aspect of life is transformed into a digitized asset to be leveraged? Ours seems to be an age when art seems helpless in the face of rising authoritarianism, or like the plaything of the worlds speculator-plutocrats, and age when “creativity” has become the buzzword for the violent reorganization of work and urban life towards an endless “now” of competition and austerity.

And yet… we are witnessing an effervescence of imaginative struggles to challenge, hack and reinvent “the economy.” Artists, technologists and activists are working together not only to refuse the hypercapitalist paradigm but reinvent the methods and measures of cooperation towards different futures. This workshop brings together many of these protagonists and their allies for a discussion on the occasion of the publication of Max Haiven’s new book Art After Money, Money After Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization.

Haiven will kick off the conversation with a short presentation of key themes in the book as they impinge upon the question of working at the intersection of “art” and new technologies (including but not limited to blockchains) to create alternative economic paradigms. The central question is, to what extent can these efforts surpass the (important) desire to redistribute wealth in a world of growing inequalities and, additionally, aim for a much more profound and radical collective reimagining of who and what is valuable.

Austin Houldsworth

Dan Edlestyn

Brett Scott

Cassie Thornton

Kate Genevieve

Emily Rosamond

Jonathan Harris

Ruth Catlow and Martin Zeilinger will chair discussions and the event is sponsored by Anglia Ruskin University

Pluto Press are happy to offer a Furtherfield discount on the book. Add Art After Money to the cart and use the discount code ART15 to get the book at £15.

On the 7th September, the Disruption Network Lab opened its 14th conference in Berlin entitled “INFILTRATION: Challenging Supremacism“. The two-day-event was a journey inside right wing extremism and supremacist ideology to provoke direct change, second appointment of the Misinformation Ecosystems series that began in May. In the Kunstquartier Bethanien journalists, activists, researchers, and infiltrators had the chance to discuss the increasing presence of movements that want to oppose immigration, multiculturalism and political correctness, sharing their experiences and proposing a constructive critical approach, based on the motivation of understanding the current debates in society as well as transforming mere opposition into a concrete path for inspirational change.

“How can you hate me when you don’t even know me?” With this question Daryl Davis tried to crumble the wall of ignorance and fear that he believes to be the basis of racial hatred. This 65 year-old author, activist and blues man, who played for decades with Chuck Barry, Jerry Lee Lewis and B.B. King, has spent 35 years studying race relations and befriending members of the Ku Klux Klan to turn them away from racism. In the context of increased supremacist ideologies and right-wing extremism, the Disruption Network Lab invited Davis to speak about racism and his interactions with individuals holding racist beliefs.

Growing up, Davis lived a privileged life as the son of a U.S. Foreign Service officer, travelling around the world and studying in an international context surrounded by children of other Foreign Service workers. His first shocking encounter with racism occurred when he was 10 years old in a 1968 Massachusetts. He was marching in a parade carrying the US- flag in front of his scouting group as people yelled racial epithets and threw rocks and bottles at him. His parents later explained that those people were targeting just him because of the color of his skin. Someone who knew absolutely nothing about his person and his life wanted to inflict pain upon him for no other reason than that. Because of this hateful reaction from so many white spectators along the route, Davis started wondering the fatidic question.

Ignorance causes fear and obviously the theses of supremacists and racist groups are built on these two components. Many years ago Davis decided to sit with them and listen to their point of view, contradicting their falsehoods using dialogue. Davis is convinced that if we do not fight ignorance it will escalate to destruction, “ignorance breeds fear; fear breeds hatred; hatred breeds destruction” as he previously stated. So, when someone says he thinks white people are superior, Daryl faces them and answers: “we are equal.” On this basis, Davis befriended hundreds of KKK-members and convinced them to rethink their choices. According to the media, he has persuaded more than two hundred of them to throw away their hoods and robes, their stereotypes and beliefs. His activity became national news as he befriended the KKK-member Roger Kelly and CNN broadcasted a story on their unusual relationship. When they first met, Kelly was “Maryland’s Grand Dragon”. Kelly didn’t know Davis was a black man and agreed to meet him. During their first meeting he spewed a lot of stereotypes, but – as Davis narrates – by the end of the evening they could agree on a few topics. The Grand Dragon told Davis they would never agree on racial issues; he said his Klan views on race and segregation were “cemented.” They continued to meet and converse about difficult and controversial matters for a long period: Kelly would attend Davis’s house and Davis would go to KKK-rallies. It took a few years but Kelly’s cemented beliefs got weaker, until he decided to quit the Klan and run for local elections. He had meanwhile become “Imperial Wizard” – which means national leader of the Klan.

During his key note Davis explained that his search for the answer to his question began one night in 1983. After having played in a country music bar a white man approached him and offered him a drink. The man later told him that it was the first time he had ever sat down and had a drink with a black man because he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Davis thought at first that the man was joking, but he wasn’t. The bluesman decided to talk to him, focusing on the fact that “they are just human beings,” he says “I respect these people when they sit, talk and listen. It’s just about difference of opinion. If you talk with them you can find things in common.” Someone might disagree with Daryl Davis that Fascism, Racism, Supremacism cannot be considered opinions, that they are crimes and that normalizing their cult is dangerous. But Davis prefers dialogue to posturing and fights. Davis believes in addressing ignorance through communication and education, to ease fear and prevent destruction. His efforts at dialogue are represented by his collection of hoods and robes from former Klan members he has befriended over time. Davis thinks that society should give these people a chance to express their views publicly to challenge them and force them to actively listen to someone else, dialoguing, to passively learn something. Many of them are anti-Semitic, neo-Nazi, Holocaust-denial and racist white supremacist, but he sees them mostly as victims of ignorance, fearing something that they just do not know. For these reasons he talks with them trying to overcome their prejudices. “Always keep the lines of communication with your antagonist open, because when you’re talking, you’re not fighting.”

Davis offers an extreme example of breaking down stereotypes to change the minds of white supremacists. It can be deeply understood only in the context of his US-American background and cultural formation. His keynote speech tended to get soaked in clichés, enriched by several “I am proud of my country” and “my country is great.” Maybe it is just a way to subtract right winged racists the monopoly over the patriotic discourse, through a moderate and gentle approach, to disrupt their one-way narrative, that conflates patriotism with rabid nationalism, showing them that he has traits in common with them. All in all his underlying convincement is that racism comes from a lack of personal knowledge of the African American experience and history, for example in music, and from a lack of personal relationships of a certain part of the white community with human beings that are not white. He thinks that by befriending ignorant racists they could relent, change their minds, have a change of heart and learn how to respect others. Davis is conscious about the fact that such an uncommon approach can be considered, at least, controversial. Many disapprove of it, pointing out that he is offering them a prominent stage in the national and international spotlight.

Davis´ activity can also be dangerous. In the past thirty years he has been attacked because of what he does. However, he is not afraid of the Klan or of racist groups. He has cultural tools to face dialectics, he has a strong identity and doesn´t want to fight against someone´s else idea of identity. On the contrary he is convinced that people of all backgrounds shall come together, getting along without losing their sense of identity or individualistic dimension, as no one shall be forced to accept an idea. Matt Ornstein has directed a documentary about Daryl Davis, that the Disruption Network Lab decided to screen during the third day of this 14th Conference. Entitled “Accidental Courtesy: Daryl Davis, Race and America.”

In Germany, individuals and organizations have been mobilizing to prevent the access of neo-Nazi to public platforms and media to spread Negationism and racist propaganda, in a collective lucid reasoning. Dialoguing with neo-Nazis, allowing them to exhibit symbols and to represent reactionary bigotry and hatred as something normal is not accepted by many people in Germany and the audience of the Conference showed reservations about Davis ‘words. Davis replied that his approach pays back. To those who tell him that he is giving racist and violent groups a platform to be normalized and to be part of the public discourse, he reminds them that most of those KKK-members that he approached decided afterwards to quit the group. It took him courage and dedication, he went to KKK-rallies, listened to their hymns, watched them set on fire giant wooden crosses during liturgical rites, witnessing moments of collective frenzy, delirium and hatred.

The documentary shows the efforts to dialogue with representatives from the movement Black Lives Matter too, that sadly ended up in a moment of misunderstanding and dramatic confrontation. Davis and Black Lives Matter have met again and have found a way to work together, going the same way approaching the issue of racism and discrimination with two alternative techniques, that are not mutually exclusive. However, Davis approach is markedly distant from this grassroots movement that organizes demonstrations and protests.

The audience of the 14th DNL Conference challenged Daryl Davis as his approach “we are all human beings” looks fragile in days of uncertainties, when extreme right movements are gaining consensus upon lies and discrimination. Inevitably, the debate after Davis ‘speech focused on the cultural shift represented by Donald Trump´s election and what came after that on a global scale. Davis said that in his opinion what is happening works as a bucket of cold water, that wakes people up and makes them engage and fight for change, reacting with indignation. Davis explained that in his opinion the #MeToo campaign came out as a positive consequence to Donald Trump´s election. “Obama was not elected by black people, who are all in all 12% of the US-population. Things change if we dialogue together, creating the bases for that change. In this way we can accomplish things that just few decades ago were thought to be unachievable.”

The panel of September the 7th represented a cross-section of the research being conducted by journalists, researchers and artists currently working on extreme-right movements and alt-right narrative. By accessing mainstream parties and connecting to moderate-leaning voters, right wing extremists have managed to exercise a significant influence on social and political discourse with an impact that is increasingly visible in Europe. The speakers on this first day of the Conference reported about their experiences with a focus on what is happening in their countries of origin: Sweden, Germany and Slovenia. Interconnecting three methodologies of provoking critical reflection within right-wing political groups, the panel reflected on possible strategies of cultural and political change that go beyond mere opposition.

Recalling all this, the moderator Christina Lee, Head of Ambassador Program and Hostwriter, introduced Mattias Gardell, first panelist of the day, Swedish Professor of comparative religion at Uppsala University, who dedicated part of his studies to religious extremism and religious racism, addressing groups such as the Nation of Islam and its connections to the KKK and other American racist activists, to focus than on the rise of neo-Paganism and its meaning for the radical right. Among his publications, a book on his encounters with Petter Mangs, “the most effective and successful racist serial killer” Sweden has ever encountered, as he writes, and recent analyses of the “lonely wolf” tactic of militant action and groups from the extreme right and the radical Islamism, that are operating under the radar, to avoid being detected and blocked by authorities.

At the time of the Conference, parliamentary elections were about to take place in Sweden. The country was then set for political uncertainty after a tight vote where the far right and other small parties made gains at the expense of traditional big parties. Gardell reported that in Sweden the political and social climate of intolerance has risen. More than half of the mosques have been assaulted or set on fire and minorities are continuously under threat. During his speech he focused on how new radical nationalist parties and movements are investing in narratives built on positive images of love and community, nostalgic sentiments and promises to return the once good society and its original harmony. They are nationalist and ‘identitarian’ groups (as they call themselves), from different nations and united under their belief in separation on the base of national identities. They often portray themselves as common citizens, worried about the vanishing of their country and identity due to a program of multicultural globalism that aims at substituting national identities and people by means of a white genocide: a constant sense of paranoia, that Gardell also perceives in a country like Sweden, where the economy is flourishing, and inequalities hit mostly migrants and non-white population.

These groups work to spread the idea of a “white nostalgia”, a rhetorical discourse based on their efforts to reiterate a rosy, but hazy period, when life was better for the white native population of a certain territory. They ambiguously evoke a moment in history, that has probably never existed, at which national identities were free from external contaminations and people were wealthy sovereign citizens. This propaganda emerges into a multi-faced production in music, film and visual arts. It is not the “angry white men” image alone that can contain such a new fragmented and liquid reality; in fact, explained Gardell, the opposite is true. They often offer a narrative, that appears to be built on love rather than on hate. Love for their nation, love for their hypothetical race, for their selected groups and communities. It is not an imaginary love, it is a deep true feeling that they feel and upon which they construct their sense of collectivity.

Gardell underlined the importance of studying every-day-Fascism, focusing on its essence made up of ordinary individuals that like football, accompany children to school, listen to music and therefore have things in common with their neighbors and colleagues to whom they might appear as moderate people. “You can’t defeat national socialism with garlic. You have to face the fact that Fascism has been supported by millions of ordinary people who considered themselves to be good and decent citizens” he said. It is necessary to unveil the false representation of a political view, evoked through posters of blonde children and pictures of smiling women, that are designed to embody a bright future and a safe homeland. It is necessary to oppose the program of selective love and restricted solidarity that extreme right and nationalist groups promote. Therefore, says Gardell, we need to challenge those representations of love for nation, homeland and family built on a language that is impressive-sounding but not meaningful or sincere at all. And not just because “white nostalgia” is a fictional invention, but – more important – because on the collective and public sphere, love and solidarity are meaningful only if they are universal and express the value of equality unless they are just synonyms for privilege from which just few people can benefit.

At the moment, ultra-nationalist and radical right parties assembling the new political scene, appear to be able to influence traditional parties and vast parts of the population using love as a political weapon, affecting the social and political landscape in many countries, succeeding in making those traditional parties copy their agenda. Their recurrent themes exploit desire for individual social retribution, the tradition of a misogynic masculinity, the enhancement of self-government tendencies and isolation in opposition to openness and solidarity. A rhetoric that exploits the presence of nonwhite minorities and economic instability of this late capitalism, creating hateful propaganda. An intense online activity of manipulation supports the point of view of these ultra-nationalists. As the DNL Conference “Hate News” (May 2018) showed, online facts can become irrelevant against a torrent of abuse, memes and hate.

Online and offline, right extremists can easily find supporters in isolated realities, in the countryside or in close web-communities. Consequently, it is important to act locally and be focused, disrupting their ability to contaminate small groups. Young people are still intrigued by the gruesome and brutal part of the black metal scene, by the fringes of anarcho-fascists and by hooligans, feeding into an international network of neo-Nazi black labels and groups. But there are now also presentable faces, new political formations with attractive slogans supported by glossy music bands and influencers that are building a narrative of love. Mattias Gardell concluded his intervention saying that these groups are currently on the rise throughout Europe, whilst a storm of Fascism is coming again, widely, to hurt exposed individuals and communities, as it is already doing. He is disillusioned and reminded the audience of the Disruption Network Lab that it is necessary to focus and act to defeat it, knowing that it will cause blood.

The analyses of Mattias Gardell introduced topics covered by the second panelist of the day Richard Gebhardt, political scientist and journalist, who gave an insight into Hooliganism based on his direct researches from the last four years in Germany and England, where the Football Lad’s Alliance established itself as a complex reality. He focused on the reasons that pushed this violent collective to become a political movement, connected in Germany to the foundation of Pegida (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West), and the increasing popularity of the parliamentary party AfD (Alternative for Germany), which is today – according to opinion polls and surveys – the second biggest political formation in Germany.

Gebhardt’s intervention began indeed with a quotation by the leader of the alt-right party Alternative for Germany: “We will hunt them down.” The parliament member was suggesting that the new members of parliament from his political formation would use their new powers to hold Angela Merkel’s government to account for its refugee policies “to reclaim their country and people.”

At the time of the Conference only a few days had passed since right-wing extremist thugs and neo-Nazis organized an assault on foreigners in the German city of Chemnitz on the 26th and 27th of August, in reaction to a murder that happened a few days before. It was a shocking moment for many Germans. However, in the following days politicians and members of the German government have tried to downplay the events, showing that big moderate parties tend to favor a certain kind of narration. Far-right violence in Germany has indeed seen a sharp rise in the last period. In this context the guest talked about the group “Hooligans gegen Salafisten” also known as HoGeSa (Hooligans against Salafists) and its origins.

On October 26, 2014, in Cologne the HoGeSa organized its first rally against Salafism. The number of participants can be ultimately estimated around 4.000 people, violent hooligans, who threw stones, bottles and firecrackers. They gathered in Cologne Central Station, with several speakers and live music, and to later march through the streets of Cologne. Xenophobic and neo-Nazi slogans were frequent, and so was the Hitler salute. During the riots dozens of police officers were injured and several police cars were damaged. Police were surprised by the inclination to excessive and unpredictable use of force. In that year thousands of refugees were traveling to Germany from conflict-ridden Middle Eastern countries and the HoGeSa was already targeting them.

In the days immediately after the demonstration, leading German politicians and prominent jurists sought to give a lighter representation of the events. The first official comments to the HoGeSa demonstration were not referring to it as a neo-Nazi demonstration, stressing the fact that hooligans are “for the most part politically indifferent” and that “they are not political but antisocial. They meet just to fight and drink.” The motto “Fußball ist Fußball und Politik bleibt Politik“ (football is football, politics stays politics) was repeated often but did not sound convincing at all. The Hooligans gegen Salafisten represented undeniably a new network of neo-Nazis, that had joined forces with football hooligans, nationalists and other right-wing extremists. Thousands of football supporters appeared to have left their football clubs of choice behind in favor of uniting against a common enemy: Islam. They chose their name HoGeSa hoping to receive popular support by recalling the fight against Islamist extremists.

Nonetheless, not every hooligan is a neo-Nazi. Press reported that in Hannover, for example, hooligans and ultras distanced themselves from the demonstration of HoGeSa and non-fascist football Ultras and that groups in Aachen, Dortmund, Duisburg, Braunschweig and Düsseldorf say they have been threatened, chased down and beaten by these Nazi-hooligans. Gebhardt suggested to the audience of the Conference a book, “Among the Thugs” by Bill Buford, to better understand the dynamics behind hooliganism. The book follows the adventures of Bill, an American writer in England, as he explores the world of soccer hooligans and “the lads”. Setting himself the task of defining why young men in England riot and pillage in the name of sports fandom, Bill travels deep into a culture of violence both horrific and hilarious.

Gebhardt portrayed these extreme right-wing rioters from HoGeSa as men, claiming to be equally distant from conservative and progressive parties, who want to be seen just as football supporters that are not carrying any ideological content, neither that of the Left nor of the Right. However, the nonpolitical hooligan is a myth: they are the heirs of a fascist tradition based on prevarication, arrogance and violence, that plays with the aestheticization of fighting and war, the glorification of militarism and pseudo-heroism. They are not worried citizens, they are thugs “ready for a civil war.” They claim to speak for the silent majority of their community, defending their country and their people. The work of Gebhardt can be seen in a documentary “Inside HoGeSa” (2018) and in his articles online.

The last guest of Friday’s Conference was a member of the project ”Janez Janša, Janez Janša and Janez Janša,” who run for office in Slovenia at the last 2018 elections, confronting the leader of the conservative Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS), and former Prime Minister, Janez Janša. “Old names, new faces” was their motto.

In 2007 three artists decided to legally change their name to Janez Janša and joined the right conservative Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS, which was originally a moderate political formation). Janez Janša is also the name of the former President of Slovenia. All of a sudden, there were at least four Janez Janšas in the country: the three artists and the politician famous for his aggressiveness and contentiousness with the opposition and anyone who dares to criticize his choices. At the time President Janša made a public statement about the artists and pro-government media started to comment on their name change criticising their “politicized art”. The activity inside the SDS of the artists served to explore the bureaucratic and political systems of their home country. Their work of investigation is instead much more complex. It reveals how the perceptual influence of a name can interfere with social dynamics. Both on a collective and subjective dimension, they researched the meaning of identity and sectioned how their private life was affected by such name change. They proved that names are just a convention, an instrument, but with a relevant role. Janša remembered as an example that the Slovenian Democratic Party, despite this name, turned into a radical, right and conservative party between 2000 and 2005. Nowadays it is engaged in anti-migrant rhetoric and populist right-wing propaganda.

The artist illustrated how, in the last decade, the Janšas responded with art, cleverness and culture to campaigns of hate and propaganda, an approach that is the base for their political interventions. Their experience was the subject of the documentary from 2012, “My Name Is Janez Janša” and is internationally known. Artists and academics are still pondering about the meaning of the Janez Janšas experience, political critique, art work, activism, provocation or never-ending joke.

During the conclusive debate all panellists agreed that the world they have been in touch with and that they described in the Conference is mostly a world of men. Women are generally present as an accompaniment and/or an accessory. It is certainly a characteristic of Fascism, described in literature and art, as designated in the book “Male Fantasy” by Klaus Theweleit, where the author talks about the fantasies that preoccupied a group of men who played a crucial role in the rise of Nazism. Proto-fascists seeking out and reconstructing their images of women. Another aspect that all three guests agreed on, is the fact that individuals are massively not voting or taking part in public life, since they are increasingly distrustful of traditional media and politicians. European moderate politicians have on the other side the responsibility of a systematic dismantlement of social rights, they justified and supported an unequal economic system of wealth distribution for too many years. Now, scandals and arrogance in public and institutional life do not seem to affect the popularity of extreme right parties, that are ridiculing the excess of fair play and the interests of those moderate politicians.

Focusing on new strategies to directly provoke change, the Conference on the 8th of September began with a performative conversation between Stewart Home (artist, filmmaker, writer, and activist from London), and Florian Cramer, (reader in 21st Century Visual Culture at Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam), moderated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, artistic director of the Disruption Network Lab. The universe of the extreme-right seems to have embraced a path of transgression, arrogance and nonconformity, employed to suggest that its members are holders of a new alternative approach in cultural, political and social criticism. What comes out from such a wave of counterculture is an articulated patchwork that flirts with violence, discrimination and authoritarism.

Bazzichelli asked the audience to question the nowadays extreme right self-definition of their political offer as an “alternative,” considering that the issue of transgression and counterculture has been widely developed by academic and artistic Left, and that experimentation, theorisation and political antagonism have been growing together in the left-leaning universe. In such a perspective, “working on something alternative” – explained Bazzichelli – is supposed to be synonymous with creating a strong criticism of media and society, through political engagement, art and intellectual efforts. An alternative that could enhance a positive, constructive contribution in the collective socio-economic discourse. Today, words like “infowar” and “alternative” tend instead to be associated with a far-right countercultural chaotic production. On this basis, Bazzichelli introduced the lecture by Stewart Home and Florian Cramer, that investigated if and to which extent it is possible to affirm that ideas and values driven from the Left are now reclaimed and distorted in an extreme-right alternative narrative.

In an historical excursus on art, literature and subcultures, the two speakers focused on the 1970s-1990s counter-cultural currents that used radical performance, viral communication and media hoaxes and examined the degree to which they may be seen as playbooks for the info warfare of the contemporary extreme right. With their presentation they suggested that it is improper to state that the alt-right has now occupied established leftist countercultural territories. There have been several examples of a parallel development and interpenetration of very opposite points of view over time. Tommaso Marinetti, father of Futurism and its Manifesto about “War, the World’s Only Hygiene,” mixing anarchist rebellion and violent reaction became then a fervent supporter of the Italian Fascism, that glorified the new futuristic approach. However, Futurism means also sound poetry, since discordant sound had a vital role in Futurist art and politics; an experience that developed into the noise movement with an influence that reached post-industrial musicians and further.

Cramer remembered that Futurism represents also an avant-garde and counterculture from the 1900s, that had similarities with Dadaism. In fact, though Dadaism was anti-war and antibourgeois, they shared a spirit of mockery and provocative performances, mixing distant genres and a massive use of communication, experimental media and magazines. Always considering the beginning of the 20th Century, the lecturers recalled the production of the painter Hugo Höppener Fidus, expression of the Life Reform Movement, linked both to the left- and the right-leaning political views, that strongly influenced Hitler and Nazism, showing roots of an alternative counterculture that went both into the political extreme right and left.

In the 1970s and 1980s, in subcultural production and artistic performances it was frequent the use of fascist symbols as provocation and transgression, for example in the punk scene, which ranged notoriously from left wing to right wing views as pseudo-fascist camp in post-punk culture turn into actual Fascism. A conscious ambiguity, part of experimentation, that – particularly in the U.S. – meant also leaving space to things that were in contrast to each other. In the context of US underground culture, the speakers mentioned publications like those from Re/Search “Pranks!” on the subject of pranks, obscure music and films, industrial culture, and many other experimental topics. Pranks were intended as a way of visionary media manipulation and reality hacking. Among the contributors, you could find artists from the industrial movement, like the controversial Peter Sotos and Boyde Rice, who became today established part of right-winged countercultural movement.

Talking about the present, Cramer and Home also mentioned Casa Pound, a neofascist-squat and political formation from Rome, that adopted the experience described by the anarchist writer Hakim Bey of the “temporary autonomous zones,” that redefined the psychogeographical nooks of autonomy – as well as appropriated the name of Ezra Pound, a member of the early modernist poetry movement.

All this suggests that the so-called alt-right has probably not hijacked counterculture, by for example deploying tactics of subversive humour and transgression or through cultural appropriation, since there is a whole history of grey zones and presence of both extreme right and left in avant-garde and in countercultures, and there were overlooked fascist undertones in the various libertarian ideologies that flourished in the underground. Home and Cramer reminded their common experience in the Luther Blissett project, based on a collective pseudonym used by several artists, performers, activists and squatter collectives in the nineties. The possibility to perform anonymously under a pseudonym gave birth to a mixed production, with undefined borders, in few cases expression of reactionary drives. An experience that we can easily reconnect to the development of 4chan, the English-language imageboard very important for the early stage of Anonymous, that today is very popular among the members of the Alt–Right scene,