Hi Shaina! Tell us about the genesis of CAMP? How are you part of it? Why are you called CAMP?

CAMP came together as a group in 2007, initially consisting of me, Shaina Anand (filmmaker and artist), Sanjay Bhangar (software programmer) and Ashok Sukumaran (architect and artist) in Mumbai, India. The intersection of our skills and different backgrounds created a vital spark in which to experiment with technology and ask deep questions about form and ways of making radical political work. We are called CAMP as we are not an artist’s collective (though we began as a collaboration with KHOJ which was an artist’s collective in Delhi, which you headed operations for) but we call ourselves a studio. In this process, we try to move beyond binaries of art vs non-art, commodity market vs free-culture and to build media for the future. Personally, it gives me the platform to eschew conservative approaches to documentary filmmaking with “the colonial male gaze.”

How did you decide to create new-media and be part of CAMP coming from a strong documentary tradition?

Oh, for that I would like to describe the response my younger self (1992-2004) had to making traditional documentaries. Travelling around India with my mentor, filming a documentary about life in villages for the anniversary of Indian independence, I described how they’d turn up in jeeps, find the subjects, and ask important questions for the nation. I became increasingly disillusioned by what I saw as the repeated orchestration of finding a subject, interviewing, zooming in, asking questions until the subject ends up crying. So, once while analyzing the relationship between filmmaker and subject I echoed the question hovering over so many discussions, “who speaks for the subject and from where?”

That’s when I decided that I had two choices, to either move into fiction which was perhaps less problematic, or to “stay with the trouble”, to let the problems drive the work into becoming something more in line with my politics. I also wanted to “trouble” the triangular relationship of author, subject and technology, so that it favored the subject more.

Very interesting! You mentioned Haraway’s “staying with the trouble”. Were you influenced by her work? Say more! I relate to that experience, having switched from working in Bollywood to doing social documentaries and now learning new-media art. So, what role do you think technology plays in fostering that relationship between the subject and the author and more importantly, how does it “favor” the subject?

Well, yeah. I feel influenced by her as a woman media-maker where I draw from her reflections on race, technology and gender. In CAMP’s work at various biennials, I have often felt that every part of the process of documentary-making had been deftly unpacked and put back together again to reflect vital contemporary political concerns within the actual structure of the work or even its distribution, not just its content. By that, I felt we succeeded in using technology to foster that relationship.

I find it fascinating that technology is not a toy or gimmick in your work but rather gives to access to places and people which traditional approaches to documentary wouldn’t. In this context, could you throw some light on the use of CCTVs in your work esp. at a time when they were increasingly being used as a tool for surveillance?

In our work Al jaar qabla al daar (The Neighbour before the house- 2009), we used CCTV cameras and set them up to film the houses where eight Palestinian families had been forcibly evicted and are linked to remote controls in new homes or refugee places where the families now live. We were then able to zoom and tilt the cameras to spy up washing or as they went about their business. The complexities of the power relations between the observer and observed are dazzlingly deft and agile, giving energy to the otherwise hopeless situation of displaced Palestinians in Jerusalem. We only hear their voices as they trace the lines of personal memory in their old neighborhoods or stalk the new inhabitants of their former homes with the remotely operated CCTV placed on nearby rooftops. We see soldiers training, Orthodox Jews going to prayer, a boy skateboarding, roofs, water tanks, a veranda built by their own families. Their bodies exert a ghostly presence on the very image we see onscreen as a small boy exhorts his mother to “zoom, zoom”– to spy on one of the new inhabitants leaving the house. But nonetheless through the active manipulation of this technology we had “captured” a settler.

Do you think technology facilitates a democratic or rather liberal exchange for the subject? Let’s say immersive technologies like virtual and augmented realities, which I’m interested in, blur the point of view of the author and the subject. What do you think?

The act of wrangling the technology to record the voices of the camera operators while simultaneously filming does create a power shift. For example, in our work, the Palestinian families may be physically invisible in the places they once lived, but their voices and ability to control how we see with even the crudest of cameras, exerts its own pressure. It acknowledges and celebrates the democratization of the camera and makes us question the veracity of all the other images we have seen about Palestine. We hear details about the neighborhoods, how the evictions happened through impossible laws or enforcements as the displaced families observe how the new families don’t clean the stairs or water the lemon tree.

Yes, I liked the use of the footage as a timeline for viewers to edit which led you to form Pad. Ma (Public Access Digital Media Archive) which I was a part of too, at some point. Interestingly, here at UCSC, I met and heard Bernard Stiegler who had long ago worked with annotating found-footage with his students thereby that puts CAMP in that discourse. Say something about that.

Well, for me, the most radical and exciting approaches to documentary were in the 60s in India. Since then, what has changed? Nothing here. CAMP’s work provides a sense of new possibilities as it steals back technology and puts it into that utopian discourse of Stiegler and others to shift our perspective closer to the subjects. By “troubling” the traditional methods of creation and dissemination it empowers both the viewer and the viewed with a fresh perspective.

Some of your work is about migrant population, home and displacement which strikes a chord with my interest in human-rights and immigration. Tell us about this work and its approach.

A privileged perspective into the worldview of another is contained in our work, From Gulf to Gulf invited by the Sharjah Biennial a few years ago.Yet again it is a document of a much richer process that began as an artwork/ community provocation/ friendship built over four years between CAMP and a group of sailors from the Gulf of Kutch in India. Initially CAMP produced radio programs culling material from sailors’ songs, conversations, phone calls etc. and later that evolved into a new-media piece that showed this totally different space in a radically fresh way. It is composed of footage of their journeys and extended selfie- films shot by the sailors on their long voyages, often accompanied by songs which they Bluetooth to each other.

Fascinating! Lastly, I’m keen to hear about what CAMP wants to do with technology next?

At any given time, CAMPwants to challenge the triangular relationship of author, subject and technology, thereby splintering the privileged gaze and our standard mode of perception. That’s our motivation behind whatever we have or will do.

Thank you Shaina for speaking as an artist from CAMP. It was great to talk to you and have worked with you all!

“Hello, I’m Riz Lateef. Tonight our top story: Instagram travel-star Amber Hinton is missing in Indonesia. Initial reports suggest she has been kidnapped by an ISIS faction operating in the region. We’ll have more on that after the headlines.”

In 2014 Amber Hinton left a lucrative job in finance to follow her ‘dream’ of travelling the world. Like many young women she recognised the potential inherent in her looks; she had an ability to tap into veins of social media, and grasped the appeal for people to ‘follow’ in her footsteps. Educated, professional and dedicated she began by surveying Twitter and Instagram; filtering by hashtags she categorised countries by cultural capital (aka likes, retweets, comments) and then cross referenced with existing coverage. Logic followed that if Thailand was hot right now it might not be hot in a year’s time. Novelty and newness would be essential to getting a foothold in the market.

After months of post-work spread-sheeting, Amber was ready. At a brunch with friends she introduced a mood-board and sales-pitched her new life. I say mood-board, but really I mean a highly aestheticised business strategy. She’d categorised hundreds of travel lifestyle pics and identified core principles of success. With Google Analytics she’d examined the lifespan of a hashtag. She’d reviewed where successful Instagram travellers had been, which countries were oversaturated and which were primed to explode. She’d mapped a route, ensuring a balance between city, beach and country, simultaneously factoring in cost efficiency. She’d prototyped a website and employed a graphic designer to mock up a look and feel for her personal ‘brand identity’. She’d run financial predictions, how long her start-up capital would last, how she expected to turn a profit through funding websites, travel blogging, and eventually as an advertising service for hotels and travel companies.

It was, in short, a stunning piece of work. If Amber had been inclined towards the monastic life of a PhD researcher, she could have turned it into four years paid writing, then subsequently taught her findings at Oxbridge without ever leaving the UK.

With her friends’ enthusiasm and her parents’ consent Amber left for Italy. Between 2014 and 2017 she travelled across the world, first moving in small steps, from Italy to Slovenia, to Bulgaria and Turkey. From Turkey she jumped around the Middle East and North Africa, avoiding conflict zones and skipping countries whose religious codes might frown upon her displayed body. Everywhere she went she befriended new contacts to utilise, chic twenty-somethings who’d invite her to their parents’ villas, rich bankers who’d get her into rooftop parties. Courting the cultural elite was vital; she didn’t have the financial reserves to fund a lavish lifestyle, but she could enter those worlds and achieve an image of effortless glamour.

By the time she reached the Moroccan coast she’d amassed over 75K followers. Enough to be on the radar of international PR girls. Invitations started flying in: five star luxury hotels and exotic adventures. Whilst sipping alcohol-free cocktails and bronzing her skin, she strategised her next move.

She flew to Malta, then across the Atlantic, island-hoping round the Caribbean. In America she visited boutique ranches and hunted down bohemian culture. Down to Mexico, then South America, a perfect blend of high class living and poverty porn. From South America she crossed the Pacific, stopping in at Hawaii on the way, then modern China and finally, in early 2017, Indonesia.

The world first knew something had gone wrong for Ms Hinton was when she posted a unusual message on Twitter. For three days she’d been five star eco-glamping in the rain-forested hills of Lombok, swimming in waterfalls, taking selfies with monkeys and then suddenly:

@amber_abroad

I heard a gun shot! What do I do! HELP HELP HELP

Minutes later a second tweet followed:

@amber_abroad

They said my name, tell me parents I love them

Within minutes a storm of activity was echoing around the Twitter-sphere and #saveamber was the number one trending topic on social media. Facebook campaigns began and Indonesian public officials were receiving flak from latte drinking yuppies in North London. By the second day the Foreign Office had publicly announced that British tourists in Indonesia were advised to leave the country immediately. Typically slow to respond, but then absolutely committed, ISIS announced that Ms Hinton’s abduction had been orchestrated by them, despite it obviously being carried out by a unassociated cell with little to no connection with the upper echelons. For three consecutive days BBC Breakfast News dedicated a half hour to the unfolding crisis; they even flew Naga Munchetty out to Bali to goad tourists into overreactions.

Five days of media fixation were followed by a week of not giving a damn; then out of the blue something very odd began to happen. Instagram accounts operating out of the Indonesian and Philippine ISIS territories started taking on a much more aesthetically sensitive tone. Poorly photoshopped images were replaced with a wave of creative shots. Against verdant jungle foliage, handsome young fighters were pictured topless, sweat glistening on their ripped pecks, rifles casually held over their shoulders. Puppies were photographed wrapped in ISIS flags. Trope travel images, ‘everyone jumping on the beach together’ and ‘girl leading boy’, were bastardised into calls to martyrdom.

At first Amber’s family was relieved; their daughter was alive and communicating with the world. Security services reassured them that eventually she would reveal her position, then they’d be able to plan her rescue. Weeks developed into months and still it seemed Amber was so tightly under the thumb of her captors that she couldn’t encode a message. All they could do was watch her PR strategy unfold.

Back home Theresa May used the crisis to spearhead her personal campaign against social media giants and internet freedoms. “By doing nothing, Instagram encourages ISIS”. In truth they were shutting down hundreds of accounts each day and actively handing data to the NSA and GCHQ.

By the time a video appeared online, ‘Amber’s Top 5 Tips For The Perfect Jihadi Pic’, Theresa had reached her line in the sand. Co-ordinating with the Indonesian President Joko Widodo, Ms Hinton was marked a priority target. If and when they had a lock on her location, an American drone would strike.

The final Instagram post attributed to Ms Hinton was posted on the 25th of June 2017.

For three weeks MI6 had been working in close communication with Indonesian intelligence officials to triangulate her location, scrutinising every post for a telltale clue. Eventually it was a sun umbrella that gave her away; its pattern of red and yellow stripes was attributed to a hotel on a recently occupied island. The post was confirmed as being a Amber original due to her characteristic use of the Juno filter and the Smiling Cat Face With Heart-Eyes emoji.

Amber’s parents were never told the truth about their daughter’s death. Several months afterwards a nice man from the intelligence services told them they believed ISIS had killed her, citing a lack of posts as evidence. Communications were falsified when they demanded proof. They were never shown the photos of her charred scalp, or the one of her left foreleg on the beach; it’d be blown clean clear of the hotel. In the end only a few people, in secret rooms, ever saw the evidence. None of the photos ever made their way online.

The New Observatory opened at FACT, Liverpool on Thursday 22nd of June and runs until October 1st.

The exhibition, curated by Hannah Redler Hawes and Sam Skinner, in collaboration with The Open Data Institute, transforms the FACT galleries into a playground of micro-observatories, fusing art with data science in an attempt to expand the reach of both. Reflecting on the democratisation of tools which allow new ways of sensing and analysing, The New Observatory asks visitors to reconsider raw, taciturn ‘data’ through a variety of vibrant, surprising, and often ingenious artistic affects and interactions. What does it mean for us to become observers of ourselves? What role does the imagination have to play in the construction of a reality accessed via data infrastructures, algorithms, numbers, and mobile sensors? And how can the model of the observatory help us better understand how the non-human world already measures and aggregates information about itself?

In its simplest form an observatory is merely an enduring location from which to view terrestrial or celestial phenomena. Stone circles, such as Stonehenge in the UK, were simple, but powerful, measuring tools, aligned to mark the arc of the sun, the moon or certain star systems as they careered across ancient skies. Today we observe the world with less monumental, but far more powerful, sensing tools. And the site of the observatory, once rooted to specific locations on an ever spinning Earth, has become as mobile and malleable as the clouds which once impeded our ancestors’ view of the summer solstice. The New Observatory considers how ubiquitous, and increasingly invisible, technologies of observation have impacted the scale at which we sense, measure, and predict.

The Citizen Sense research group, led by Jennifer Gabrys, presents Dustbox as part of the show. A project started in 2016 to give residents of Deptford, South London, the chance to measure air pollution in their neighbourhoods. Residents borrowed the Dustboxes from their local library, a series of beautiful, black ceramic sensor boxes shaped like air pollutant particles blown to macro scales. By visiting citizensense.net participants could watch their personal data aggregated and streamed with others to create a real-time data map of local air particulates. The collapse of the micro and the macro lends the project a surrealist quality. As thousands of data points coalesce to produce a shared vision of the invisible pollutants all around us, the pleasing dimples, spikes and impressions of each ceramic Dustbox give that infinitesimal world a cartoonish charisma. Encased in a glass display cabinet as part of the show, my desire to stroke and caress each Dustbox was strong. Like the protagonist in Richard Matheson’s 1956 novel The Shrinking Man, once the scale of the microscopic world was given a form my human body could empathise with, I wanted nothing more than to descend into that space, becoming a pollutant myself caught on Deptford winds.

Moving from the microscopic to the scale of living systems, Julie Freeman’s 2015/2016 project, A Selfless Society, transforms the patterns of a naked mole-rat colony into an abstract minimalist animation projected into the gallery. Naked mole-rats are one of only two species of ‘eusocial’ mammals, living in shared underground burrows that distantly echo the patterns of other ‘superorganism’ colonies such as ants or bees. To be eusocial is to live and work for a single Queen, whose sole responsibility it is to breed and give birth on behalf of the colony. For A Selfless Society, Freeman attached Radio Frequency ID (RFID) chips to each non-breeding mole-rat, allowing their interactions to be logged as the colony went about its slippery subterranean business. The result is a meditation on the ‘missing’ data point: the Queen, whose entire existence is bolstered and maintained by the altruistic behaviours of her wrinkly, buck-teethed family. The work is accompanied by a series of naked mole-rat profile shots, in which the eyes of each creature have been redacted with a thick black line. Freeman’s playful anonymising gesture gives each mole-rat its due, reminding us that behind every model we impel on our data there exist countless, untold subjects bound to the bodies that compel the larger story to life.

Natasha Caruana’s works in the exhibition centre on the human phenomena of love, as understood through social datasets related to marriage and divorce. For her work Divorce Index Caruana translated data on a series of societal ‘pressures’ that are correlated with failed marriages – access to healthcare, gambling, unemployment – into a choreographed dance routine. To watch a video of the dance, enacted by Caruana and her husband, viewers must walk or stare through another work, Curtain of Broken Dreams, an interlinked collection of 1,560 pawned or discarded wedding rings. Both the works come out of a larger project the artist undertook in the lead-up to the 1st year anniversary of her own marriage. Having discovered that divorce rates were highest in the coastal towns of the UK, Caruana toured the country staying in a series of AirBnB house shares with men who had recently gone through a divorce. Her journey was plotted on dry statistical data related to one of the most significant and personal of human experiences, a neat juxtaposition that lends the work a surreal humour, without sentimentalising the experiences of either Caruana or the divorced men she came into contact with.

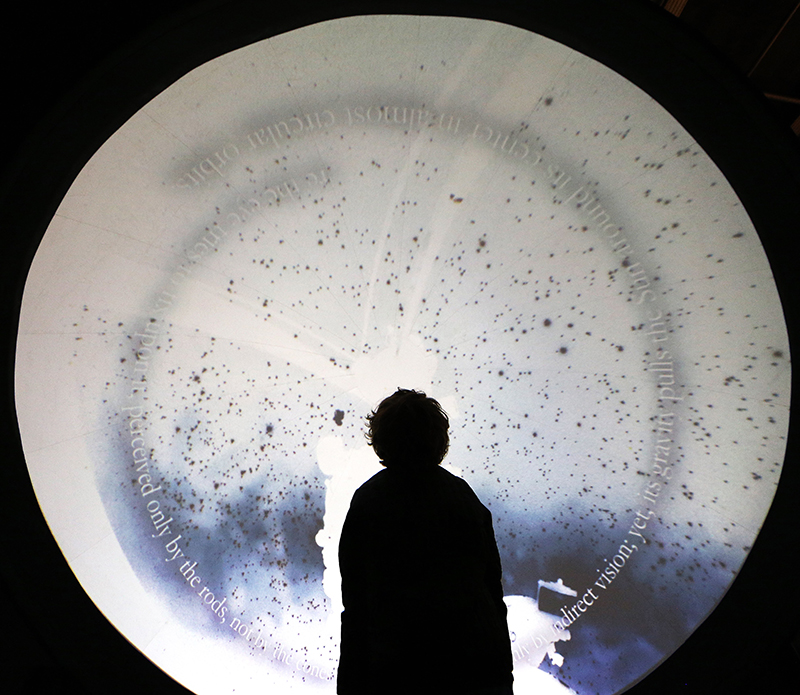

The New Observatory features many screens, across which data visualisations bloom, or cameras look upwards, outwards or inwards. As part of the Libre Space Foundation artist Kei Kreutler installed an open networked satellite station on the roof of FACT, allowing visitors to the gallery a live view of the thousands of satellites that career across the heavens. For his Inverted Night Sky project, artist Jeronimo Voss presents a concave domed projection space, within which the workings of the Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy teeter and glide. But perhaps the most striking, and prominent use of screens, is James Coupe’s work A Machine for Living. A four-storey wooden watchtower, dotted on all sides with widescreen displays wired into the topmost tower section, within which a bank of computer servers computes the goings on displayed to visitors. The installation is a monument to members of the public who work for Mechanical Turk, a crowdsourcing system run by corporate giant Amazon that connects an invisible workforce of online, human minions to individuals and businesses who can employ them to carry out their bidding. A Machine for Living is the result of James Coupe’s playful subversion of the system, in which he asked mTurk workers to observe and reflect on elements of their own daily lives. On the screens winding up the structure we watch mTurk workers narrating their dance moves as they jiggle on the sofa, we see workers stretching and labelling their yoga positions, or running through the meticulous steps that make up the algorithm of their dinner routine. The screens switch between users so regularly, and the tasks they carry out as so diverse and often surreal, that the installation acts as a miniature exhibition within an exhibition. A series of digital peepholes into the lives of a previously invisible workforce, their labour drafted into the manufacture of an observatory of observations, an artwork homage to the voyeurism that perpetuates so much of 21st century ‘online’ culture.

The New Observatory is a rich and varied exhibition that calls on its visitors to reflect on, and interact more creatively with, the data that increasingly underpins and permeates our lives. The exhibition opened at FACT, Liverpool on Thursday 22nd of June and runs until October 1st.

“In a world full of conflicts and shocks,” has the past year become the, arguably, most standardized introduction, preempting, in an almost doomsday manner, articles, political speeches and curatorial statements alike. The world has turned Political (with capital P) and even the most mundane event is quickly made part of current politics, which in turn, seems to occupy a space somewhere between reality TV and satire. One feels the same dreadful fascination as when watching accident videos on YouTube; with eyes hypnotically fixed to the screen as we observe our world digress into an ever-growing state of chaos. A general unease can be traced throughout the world, and even the most apolitical communities are mobilizing at each side of the spectrum, in the desperate search for ways to overcome the immediate and underlying threats-at-hand.

It is within this urgent search for solutions, that this year’s Venice Biennale positions itself. The 57th biannual gathering of today’s most prominent instances of Contemporary Art, offer, under the lead of curator Christine Macel, its own proposal as to how we might address our sometimes-hopeless situation. And, perhaps surprisingly, we are in fact given an answer, which eschews the otherwise often-ambiguous and overly-complicated musings traditionally marking the Art World. Within the manifesto of the biennale, immediately greeting you as you enter the Giardini venue located South of the City, Macel calls for a return to humanism, expressing the need for a new-found believe in the power and agency of humans. And not just any human; particular emphasis is given to the Artist, the persona through which, supposedly, “the world of tomorrow takes shape.”

Structurally, the role of the artist is explored over the course of nine chapters, spanning themes as distinct as ‘earth’, ‘colors’ and ‘time and infinity’. Each, we are told, does not only account for the artist’s practice in isolation, they further set out to investigate how such creative acts resonate and bring about change in the world.

One misses immediately this latter concern within the two first pavilions Artists and Books and Joys and Fears. We are invited into the space and mind of the artist, in what quickly becomes an introvert, almost nostalgic account of the studio, presented here as a place which escapes the neoliberal ideals of progress and productivity. One senses an immediate contradiction, being surrounded by pieces which literally embody the immaterial value so indicative of modern capitalism.

This haunting sense of conflict is occasionally placated, if only because many of the individual pieces go further than the prescribed curation, integrating a sense of criticality in their exploration of the art practice. As in the breathtaking video by Taus Makhacheva, in which a tightrope walker carries paintings between two cliffs, over a lethal fall, seemingly free, while caught in a pointless, repetitive and dangerous act, dictated by guidelines which goes beyond his immediate control. Or in the, now infamous work, by John Walter, Study Art Sign, which appropriates the language of advertisement in simple catch phrases such as “art – for fun or fame,” and in doing so, highlights the entanglement of any artistic act with commercial viability.

A 20-minute walk, and the habitual crossing of at least 5 Venetian bridges, brings you to the Arsenal pavilions, and the home of the next 7 chapters. The first two of these, Commons and Earth, are (at least superficially) more successful in exploring the link between the artist and the world at large. The exhibited pieces are centered around the creation of community or situations. They echo in this sense the much-disputed Relational Aesthetics as advocated by Nicolas Bourriaud, which defines contemporary art, as one of “interactive, user-friendly and relational concepts.”(1)

What Bourriaud and the Biennale both seem to overlook, is the inescapable mediation and exclusivity of artistic acts, despite any willingness to advocate inclusivity and openness. Because, let’s face it, none of the presented practices can be equaled to just another social situation – each and single one has been extensively documented, carefully edited and analyzed, to finally make their way into one of the most prestigious temples of contemporary art: The Venice Biennale anno 2017.

This does not make them insignificant, it simply means that one cannot feign apparent neutrality, as the emphasis on ‘anthropological approaches,’ seems to suggest. In fact, the more ‘honest’ pieces are the ones which embrace such mediation, exposing it, rather than hiding it behind a layer of innocent interaction. This is done brilliantly in the video piece of Charles Atlas, A Tyranny of Consciousness – an epic compilation of sunsets, countdowns and disco. The groovy lyrics, ‘You were the one, I blew it, it’s my own damn fault,’ sung by the iconic drag queen Lady Bunny, is given new meaning in the context of environmental, human-provoked disasters.

This is done, while avoiding any moralistic undertones. Rather, the piece dares to reflect the ambiguity which defines the actual human-earth-relation, and through this, overcomes the simplified ‘if we all work together it’ll be fine’ attitude, otherwise permeating the majority of the exhibited work.

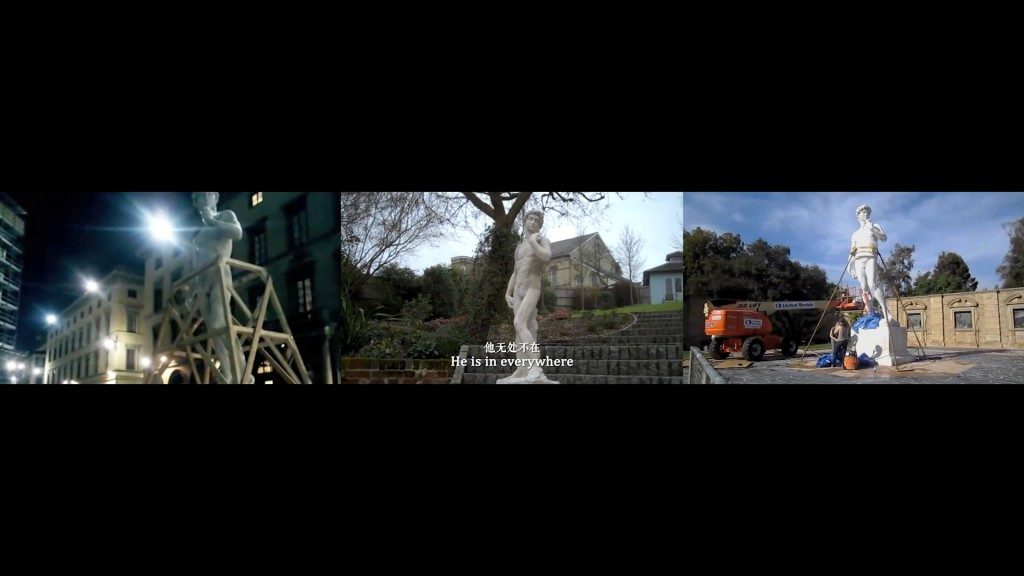

Within Traditions, the chapter following, the most successful pieces are similarly those which allow for complexity and move beyond an often much-too-obvious contrasting of the old with the new. One notable example, is the piece by Guan Xiao, which traces the famous statue David by Michelangelo. In bringing together numerous amateur-looking clips capturing this iconic figure, she humorously points to how objects ironically become invisible, through our extensive documentation of them; as hidden behind the connotations and expectations which come to shape the way we perceive our cultural heritage.

On entering the next theme of Shamanism, the first piece which meets the visitor is by Ernesto Neto – a tent-like installation made up of robes, under which guests are offered a place to rest. The otherwise beautiful piece come to look like a feature of Burning Man, with hippie-esque slogans such as ‘with love and gratitude to mother earth’ or ‘’war is not good, gold is life,“ covering the surrounding walls.

What Macel here wants to explore is the artist as magician or healer. While attempts of healing is sympathetic (and needed), such efforts are undermined by, a once again, rather naïve approach. It seems as if the striking similarity to the peace-promoting, but notoriously exclusive, festival is not only aesthetic. There is a failure at acknowledging the difference between giving the (very specific demographic of) biennale goers a place for momentary reflection, and the large-scale healing announced in the curatorial statement.

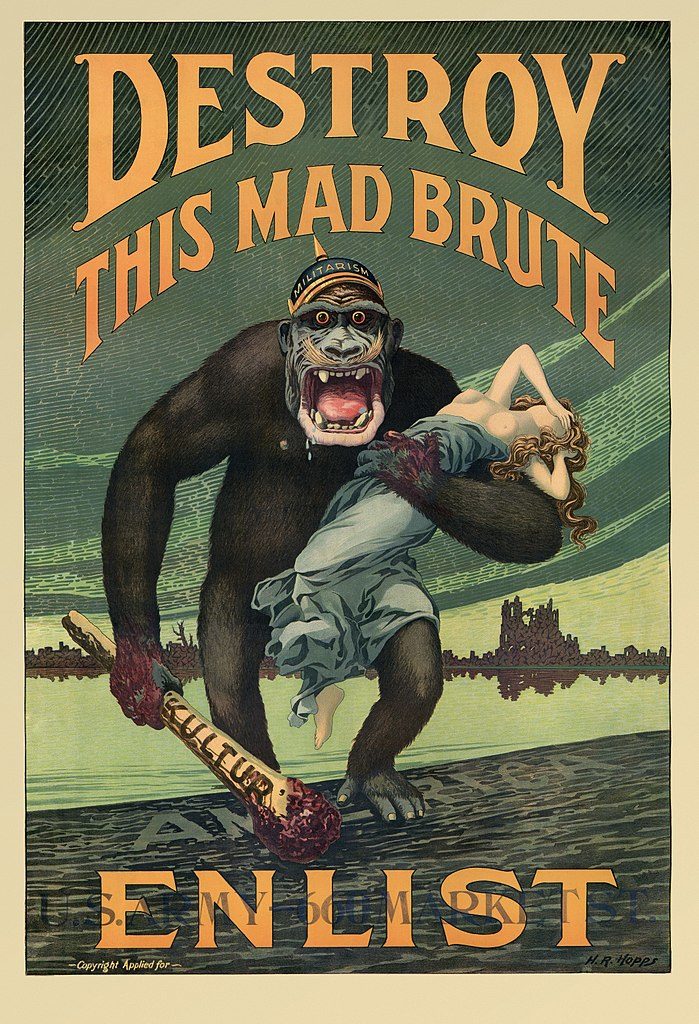

This pseudo-commitment to seventies politics carries over to the Dionysian Pavilion, which ‘celebrates the female body and its sexuality’. The decision to dedicate a pavilion specifically to female artists and femaleness implicitly tells us that

a) womanhood is still something distinct, which should be explored separately from other identity politics

b) women artists need their own space, neatly separated from the rest of the pavilion (which is, interestingly, dominated by male artists)

We see here not only a return to humanism, but the ugliest of humanisms, one which still insists on highlighting an assumed distinction between manhood and womanhood. Such essentialist undertones are only enforced by the first part of the pavilion which greets you with pastels, vaginas and a propensity for weaving.

While the theme might be questionable, we do, while moving through the pavilion, find some incredibly strong pieces, which insists on addressing the individual in its many nuances and confused nature. This is particularly present in the all-encompassing installation/sound/performance work of artists Pauline Curnier Jardin, Mariechen Danz and Kadar Attia.

This far-reaching journey culminates in the chapters Colours and Time and Infinity which bombastically sets out to explore the way artist come to influence that which exists outside and before a human sphere. Within both pavilions, there is a distinct failure at acknowledging the specificity of the individual works, which, besides from their formal qualities, seems to have little to do with either Colours or Time. Once more the curation, ironically, overshadows, rather than enhances, the complexity of the individual works at stake.

It is symptomatic of the, perhaps biggest, misunderstanding of this year’s biennale: That a return to the artist, or the human more generally, is what will allow us to understand and surpass our current state of crisis. It seems to overlook that our anthropocentric attitude is what originally brought us into trouble. Just as the individual pieces of art are diluted by insisting on the narrow focus of the artist, so does humanism distract us from the complexity of the world in which the human is only one part out of many. It simply seems outdated to return to the human-figure, conceptually broken by critical theory and practically threatened by developments in AI. Rather we need to accept, as many of the brilliant pieces do, a state in which humans are not in control; which allows for spaces of ambiguity and contingency. We do not need a return to humanism. Rather, now is a time to be humble, to look outside of humanity and think beyond that which already was, and never really worked in the first place.

Carla Gannis and Alan Sondheim will be talking about their artwork featured in the new exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery, Children of Prometheus.

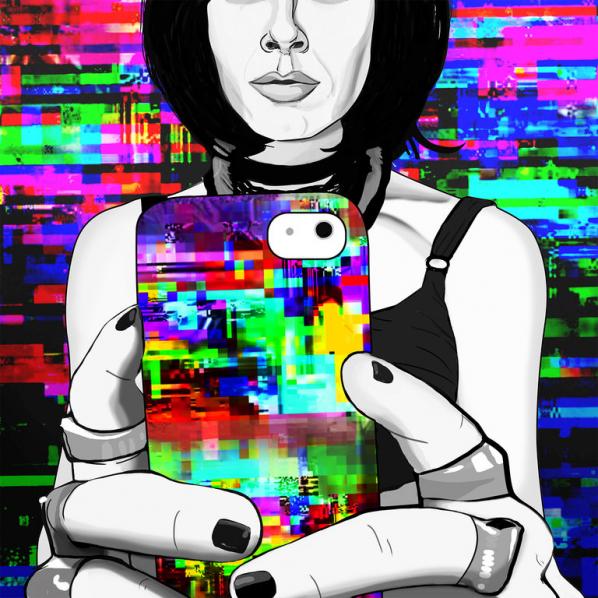

In the exhibition Carla Gannis updates Hieronymus Bosch’s famous triptych in her Garden of Emoji Delights replacing medieval religious symbolism with an emotion-inspired iconography for the 21st century. Bosch’s painting was made between 1490 and 1510. In the original, the left panel depicts God presenting Eve to Adam, the central panel is a broad panorama of socially engaged nude figures, fantastical animals, oversized fruit and hybrid stone formations. The right panel is a hellscape and portrays the torments of damnation. Gannis’s contemporary version plays on the original themes, and even expresses hedonism. However, there is another message looming in the work. That, even though we are entwined today in our digital networks, products of hyper-capitalism, and technological devices, learned culture, and acquired values: we are all feral beings at our core.

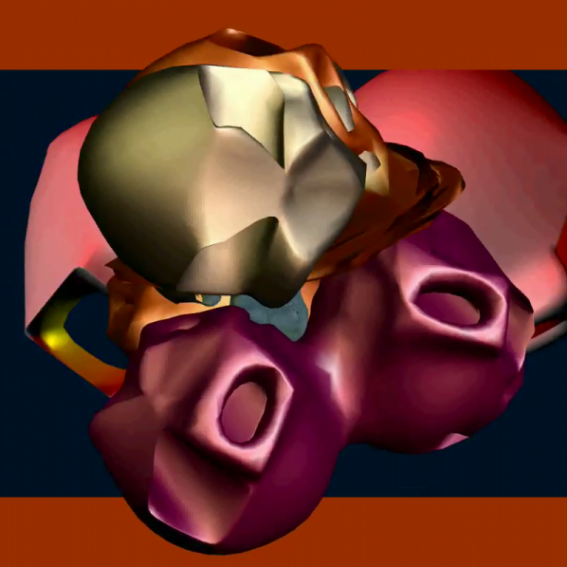

In the exhibition, Alan Sondheim presents Avataurror, a series of 3D printed avatars and videos representing distorted, wounded, problematic bodies, and their relationship to states of violence and genocide, where cracks and wounds are eternally everywhere and nowhere. Most of what Alan does, is grounded in philosophy – ranging from phenomenology to current philosophy of mathematics to his own writing. “I’m interested in the ‘alien’ which isn’t such of course, which is blankspace. (The alien is always defined within edge spaces and projections; we project into the unknown and return with a name and our fears and desires.)”

Carla Gannis is an artist who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. She received a BFA in painting from The University of North Carolina at Greensboro and an MFA in painting from Boston University. In the late 1990s she began incorporating net and digital technologies into her work. Gannis is the recipient of several awards, including a 2005 New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) Grant in Computer Arts, an Emerge 7 Fellowship from the Aljira Art Center, and a Chashama AREA Visual Arts Studio Award in New York, NY. She has exhibited in solo and group exhibitions both nationally and internationally. She is currently Assistant Chair of Digital Arts at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

Alan Sondheim was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania; he lives with his partner, Azure Carter in Brooklyn NY. A cross-disciplinary artist, writer, and theorist, he has exhibited, performed and lectured widely. Recently, Sondheim had a successful residency at Eyebeam Art + Technology Center in New York; while there he worked with a number of collaborators on performances and sound pieces dealing with pain and annihilation. He also created a series of texts and 3D printing models of ‘dead or wounded avatars.’ His ideas explore death, sex, space, time, terror and how these effect our psyche and the body.

More information about Children of Prometheus.

FREE

BOOKING IS ESSENTIAL – BOOK HERE

STRICTLY NO LATE ADMITTANCE

Choose Your Muse is a series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

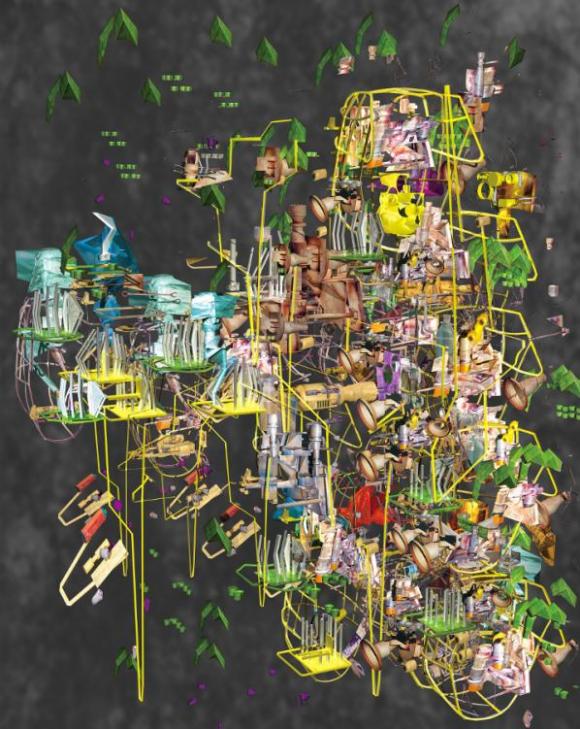

Ryota Matsumoto is a principal and founder of an interdisciplinary design office, Ryota Matsumoto Studio, and an artist, designer and urban planner. Born in Tokyo, he was raised in Hong Kong and Japan. After studies at Architectural Association in London and Mackintosh School of Architecture, Glasgow School of Art in early 90’s, he received a Master of Architecture degree from University of Pennsylvania in 2007. Before establishing his office, Matsumoto collaborated with a cofounder of the Metabolist Movement, Kisho Kurokawa, and with Arata Isozaki, Cesar Pelli, the MIT Media Lab and Nihon Sekkei Inc. He is currently an adjunct lecturer at the Transart institute, University of Plymouth.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Ryota Matsumoto: As I have collaborated with the founders of the Metabolist movement of the 60s, Kisho Kurokawa and Arata Isozaki, and had the opportunity to meet Cedric Price at Bedford Square, I am keenly aware of the participatory techno-utopian projects by the Situationist International group. Some of the projects by Japanese Metabolism, Yona Friedman, and Andrea Branzi drew inspiration from the concept of unitary urbanism and further developed their own critical perspectives. Their work has helped me to create my own theoretical platform for the status quo urbanism and its built environment.

MG: How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

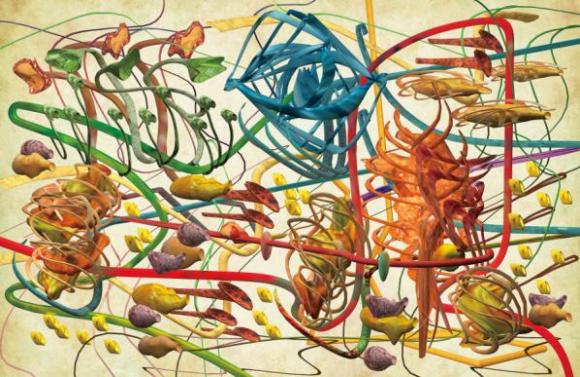

RM: I identify with the free-spirited and holistic approaches of these theorists on the relationship between language, narrative, and cognition. They embraced a wide range of media for visual communication that simultaneously defied categorization as either art or architecture and denounced the rigid policy-driven urban planning. Who would have thought of using photomontage, computer chips, PVC, or anything else they could get their hands on for architectural visualization in those days? Furthermore, their urban strategy of mobile/adaptable/expandable architecture and the theory of psychogeography dérive resonate with my own creative thinking. I interpret urbanization as the outcome of self-generating, spontaneous and collective intelligence design process and believe that the strategic use of hybrid media with incorporation of multi-agent computing provides an alternative approach for both art and design practice.

MG: How is your work different from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

RM: The utopian aspirations of the groups in the 60s were very much the product of the counter-cultural movement of the time: they were politically engaged and had optimistic outlooks for technology-driven progress of cities. In contrast, while I tend to address the current socio-cultural agendas of urban and ecological milieus, my work doesn’t necessarily evoke or represent the utopian or dystopian visions of spatial cities.

MG: Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

RM: I explore and question both sustainable and ethical issues of the urban environment that have been influenced by the socio-political realities of the Anthropocene, using visual/cognitive semantics, analogical reasoning, and narrative metaphors. As human population and energy use have grown exponentially with great acceleration, the interactive effects of the planet transforming processes on the environment are impending issues that we have to come to terms with. Thus, my projects hinge on how trans-humanism, the emergence of synthetic biotechnology, and nano-technological innovations can help us respond to the current ecological crisis.

“The themes of my work hinge on how the scientific tenets of trans-humanism, the emergence of synthetic biotechnology and Nano technological innovations might respond to the Anthropocene epoch, and, eventually foster critical thinking in relation to the underlying agendas of the increasing dominance of human-centric biophysical processes and the subsequent environmental crisis.” [1] (Matsumoto 2017)

With my recent work, the symbiotic interplay of the advanced biosynthetic technologies and the preexisting obsolete infrastructures has been explored to search for an alternative trajectory of future environmental possibilities. In short, new technologies can complement old ones instead of completely replacing them, to avoid starting over from a blank slate or facing further ecological catastrophes.

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

RM: I was fortunate enough to experience firsthand Hong Kong’s rapid urbanization driven by the staggering economic growth throughout 70s and early 80s. In hindsight, it could be called the beginning of rising prosperity in the Pearl River Delta region. I was fascinated by the fact that both the unregulated Kowloon Walled City and the newly-built Shanghai Bank Tower stood only a few miles apart from each other around the same period. They could be seen as two sides of the same coin, as they both represented the rapid and chaotic economic growth of Hong Kong at that time. It suddenly dawned on me that the juxtaposition and coexistence of polar-opposite elements connoted both visual tension and harmony in a somewhat intriguing way, regardless of their nature, function, and field. That contradiction nurtured and defined my own aesthetic perceptions in both visual art and urban design.

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and social change?

Although it might sound like a career detour at first, it is always helpful to go off the beaten path before starting out as an artist. In my case, my experience as an architectural designer and urban planner certainly helped me to break the creative mold and approach my work with a broader perspective. Even now, I still firmly believe that it is always helpful to learn and acquire the wider knowledge and skills from other fields, and that opening up your mind to new ideas will allow you to discover your own unique path in your life.

RM: Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

The retrospective of Le Corbusier’s work is the last exhibition I’ve seen and it was very fascinating. He is a great innovator, who had managed to continually reinvent himself to stay ahead of the curve over the course of his life. If you are interested in 20th century architecture encompassing early modernism and the Brutalist movement, it is definitely worth visiting.

Walking off the Akadimias district and onto the steps leading up towards the entrance of building number 23, I am greeted by a large hall with high red ceilings. The hall is covered with lavish white and black dot marble, and there is a large staircase acting as a guide to the top floors of the manor-like building. This was the home for the Diplomatic Centre of the Third Reich, designed in 1923 by Vassillis Tsagris, and used until 2011 by the Foreign Press Correspondent Union after the Second World War. Since then it has stood derelict and dusty, but for one week, in parallel to the opening of documenta 14, it played temporary host to the artist-in-residence programme of Palais de Tokyo, alongside with Foundation Fluxum/Flux Laboratory, bearing the name Prec(ar)ious Collectives. Six visual artists in residence at Pavillon Neuflize OBC and eight contemporary Greek choreographers envision and fabricate a hybrid space whereby an experimental notion of a community is executed as a situation rather than as a subject. The visual artists and performers involved congregated together in Athens and on site for a two-week workshop in March in order to produce the works. The title, Prec(ar)ious Collectives, is a linguistic amalgamation of the adjectives ‘precarious’ and ‘precious’, implying the state of the collective that performs together.

The opening façade echoes with the humming and reverberated sound of Manolis Daskalakis-Lemos‘ Dusk and Dawn Look Just The Same (Riot Tourism), guiding us towards its installation room. The video installation stands above a mountain of blue powder in a room sectioned off with construction tape. The short sequence of about a minute and a half displays a group of hooded figures, dressed identically. As the soundtrack’s volume begins to escalate, the group progresses from walking to running on the uncannily void and ghostly streets of Athens. A city always bustling with noise is now at its most quiet and pubescent state of the day – dawn. The hooded figures run together and – even though it is in a disordered manner – command your attention and pensiveness until they all reach Omonia Square. The work demonstrates a resistance to a status quo which may be aligned with the political engagement within the city. This is not, however, done in an expected reactionary manner, but instead in a way that promotes uprising through the creation of a meditative state. One cannot help but watch Lemos’ work a couple of times more before leaving it behind and only then noticing the thundering beneath their feet.

This historic building has a basement and is the temporary home of Taloi Havini‘s performative work. The large-scale installation occupying four rooms consists of PVC vinyls, seemingly discarded or hung from the low ceiling. These PVC vinyls are lit by dispersed and differently coloured strings of light, some are red, others are purple and others are cream. The performance is underway and its performers dress themselves with the PVC vinyl and the lights and jolt their bodies vigorously to the rhythm of the thundering – sometimes in sync, sometimes not. The dark basement is transformed into a cavern of rhythmic delight alluding to a ritual where its power lies in the gathering of people.

As one inspects the garments of Wataru Tominaga and those who wear them, this synthesis of the PVC, the space and the performers as a gathering appears to be a motif. Tominaga created the garments during a preliminary workshop, with great care and appreciation of how he and others were to utilise them during Prec(ar)ious Collectives. Originally presented on mannequins before being worn and performed, the garments boast vivid colours and patterns, some of them containing animalistic features such as feathers or fur. Those who wear Tominaga’s work perform in such a way as to invent a new form of communication between themselves and their observers. They move and conjoin like animals, sometimes hiding underneath the fabric and at times evoking the traditional Japanese ‘snake dance’. The performance, being in a transitional space between the ground floor and the first floor, naturally spreads itself upstairs whereby the performers not only continue to wear the garments in obscure ways, but additionally interact with Yu Ji‘s agave plants and other objects.

Yu Ji‘s work, Lycabettus Tongue, Oliv Oliv and This is Good For You! Are formed by the use of displaced agave plants, half-fragmented found mirrors and lights. The agave plants interlock with various architectural patterns of the building such as stair banisters, whilst the mirrors and round-ball lights are positioned in ways offering various points of view for observation and appreciation of space. The work revitalizes the architecture of the building denoting its historical vitality and the synergy of the encompassing works into a haunting existence rather than an abandoned one. Here, haunting is used not for means of negative connotations but instead as a form of aloof yet introspective sensation, exasperated further with Lola Gonzàlez‘s video installation in the next room.

Lola Gonzàlez‘s Now my hands are bleeding and my knees are raw begins with its protagonists split into groups and observing the city of Athens from various points at the top of the hills. The groups begins to move, run and hop together towards a direction down the hill, whilst a chorus of droning voices begin to chant and harmonise. As the groups get closer and closer to the city, Gonzalez transforms the image into a complete inversion, like one you may find in negative photography. The chanting becomes louder as the three groups get closer and closer to their meeting point within the city – the exact space where the video is being showed. They are finally shown entering the building and making their way up the stairs to the room where they vocalize in unison until they fade away from our view. Now my hands are bleeding and my knees are raw alludes to an atmosphere in which the power of gathering together evokes a community whose intention is situated between an uncertain balance of peril and strength. It is the same kind of uncertainty that one finds when exploring the top floor of the building only to discover Thomas Teurlai‘s room of machines and looped functions.

On the top floor, there are still the remnants of neglect, rooms empty of anything but the garbage that piled up over the building’s six years of desertion. Thomas Teurlai‘s Score for bodies and machines consists of a room installation of two printers used by the performers to scan different parts of their bodies. These scans are then plastered on the wall whilst the fluorescent lights constantly trickle on and off. The two performers are attempting to archive as much of the movement involved in their choreography as possible. The looped function of copying and the crackle of its repetitive working-noises do not clash with the choreography but instead drive its energy.

Indeed, it may be the encounter between the building, the communal working spirit of the performers and the result of this effort that defines this rejuvenating energy as a fruitful rebirth of the building’s utility.

To find out more, read Chloe Stavrou’s recent interview with Fabien Danesi of Prec(ar)ious Collectives.

CS: Tell us a little bit about how the collaboration between Palais de Tokyo’s residency Pavilion Neuflize OBC and Fluxum/Flux Laboratory came about. Did this directly contribute to the hybrid of visual/dance performance art or was it the artists’ call?

FD: During two years, the Pavillon Neuflize OBC has worked with the National Opera of Paris for projects at the crossroads between contemporary art and choreography. We wanted to develop this perspective which is a kind of tradition in the history of the Pavilion (created in 2001), if we remember that our institution has a long interest for transdisciplinarity. So the hybridization between visual art and performance wasn’t the artists’ call. On the contrary, we asked them to step aside for collaborating with choreographers. It was really experimental for them.

CS: Neither Palais de Tokyo or Fluxum/Flux Laboratory are situated in Greece. What was the reason for its inception to take place in Athens? Was it because of the traffic Athens would see due to documenta 14 or was it a suggestion by Andonis Foniadakis, the choreographic director?

FD: Since its creation, Fluxum/Flux Laboratory has developed many dance projects in Greece. And it’s due to its founder, Cynthia Odier, that Ange Leccia and myself met Andonis Foniadakis. We started the dialog with Andonis right at the moment of his nomination as the Ballet Director of the Greek National Opera, o Athens appeared quickly as the perfect place for our collaboration. We decided just afterwards to take advantage of the presence of documenta 14 in the city.

CS: The result is quite impressive – specifically since, and correct me if I’m wrong – the work produced was created in only two weeks in March. How did you find the process of working and creating collaboratively in addition to being in an unfamiliar city?

FD: The residents came to Athens for the first time in November 2016. During the first week, we had met the choreographers and dancers but also people who are engaged in the artistic life of the city. We tried to understand and use the pulse of this specific urban energy. We visited some sites for the exhibition and began to question the relevance of our own presence here. The conversations with the choreographers permitted us to create a strong link with Athens and not feel like tourists. We came back for a three-week workshop in March, just before the opening of our show. Between these two stays, we discussed a lot and had decided to start from our situation with the desire to move away from an artificial subject. The notion of the collective seemed a good way of taking charge of what we tried to do – especially because the Pavilion tries every year to create a specific group that gives a specific form to its structure.

CS: Prec(ar)ious Collectives feels like it could be quite nomadic as it is in an unfamiliar environment; however nomadic does not mean it feels odd or out of place – in fact it felt quite the opposite. As a curator, how did you approach Athens and stay conscious of the context(s) surrounding it?

FD: The fact that we didn’t exhibit in a white cube or an artistic space helped us. When we decided to occupy this abandoned building on Akadimias Street, I was sure that we would be related strongly to the city and its history. The context wasn’t outside of the walls – it was here, with us. Of course, we were all conscious that we needed to stay in relation to what was happening in the city. That’s why nobody arrived with their work completed and done. The materials and the main elements of the creations were an artistic answer to this particular context.

CS: I am very curious about the building. I understand it used to be the Diplomatic Centre for the Third Reich during the Second World War. How did you become aware of its existence, and did your decision to curate Prec(ar)ious Collectives have anything to do with the building’s history? If not, what was the reason for selecting this building?

FD: In January 2017, the director of the Pavilion Ange Leccia was in Athens to present some of his work. He visited the exhibition organized by Locus Athens in this space and it impressed him quite a bit. We wanted to work in an abandoned site for underlining the economical and cultural situation in Greece. And Akadimias Street 23 seemed perfect. We didn’t choose it for its history, even if these multiple layers added some density to our proposal. For sure, the different atmospheres of the rooms immediately gave us the possibility to create dialogs between the works while preserving the integrity of each. So, it was a question of ambience in the sense of the architectural conditions aiding the experience of the audience.

CS: I found that a continuous theme within the exhibition was not only the creation of a utopic community, but also an ambience that generates a state of limbo – of transition. Was this a reference to the state of Athens or to the state of artistic production or work?

FD: The notion of limbo is stimulating. And it insists on our «spectral approach». It means that we have tried to give life to this abandoned building. And some installations can be described as floating. In Manolis Daskalakis-Lemos and Lola Gonzalez’s videos, for example, there is the idea of apparition. And even with Taloi Havini’s huge ephemeral camp, we can feel a sort of «in-between» space, archaic and futurist, protective and dangerous. Maybe it was a re-transcription of our impressions about Athens, so appealing and full of energy, but at the same time, so undermined by the political situation.

CS: As a final note, what is the next step for Prec(ar)ious Collectives after its brief residency in Athens? Are there any plans to simulate the experience, albeit differently, again in another context or place?

FD: There won’t be another step for Prec(ar)ious Collectives as a group exhibition. It was really the result of a one-month workshop. But it happens for the best that some encounters initiated in the Pavilion can be developed after the time of the residency.

CS: And any future projects that you will be a part of?

FD: On my side, I will develop a curatorial project next year in Los Angeles in the frame of FLAX residency. Titled The Dialectic of the Stars, I will organize several evenings in different institutions which will permit artists? to drift in the city from one site to another for catching some contradictory parts of the L.A. atmosphere. The idea is to mix French artists and Los Angeles-based artists and to trace a political and poetical constellation.

To find out more read Chloe Stavrou’s recent review: Community Situation: Prec(ar)ious Collectives and documenta 14

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

DOWNLOAD EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

Featuring Anna Dumitriu (in collaboration with Melissa Grant and Rachel Sammons), Carla Gannis, AOS (Art is Open Source), Simon McLennan, and Alan Sondheim.

Humans have always exploited the raw materials this planet has to offer – with the power to change the nature of things, whether physical or virtual. With constant re-edits and enhancements we transform everything we touch as part of our evolutionary mutation. In Greek mythology Prometheus was a demigod and a Titan worshipped by craftsmen. Greek Titans were ultimately honoured as the ancestors of humans, who in turn were attributed with “the invention of the arts and magic” (Graves 1964). The artists featured in Children of Prometheus at Furtherfield Gallery explore the possible consequences of our scientific and technological imaginings for us as individuals, our society and the world at large.

In this exhibition, visitors can encounter Anna Dumitriu’s Microbe Mouth, a necklace of unique teeth grown from bacteria. Microbe Mouth is a collaboration with scientists Melissa Grant and Rachel Sammons from the University of Birmingham’s School of Dentistry. Carla Gannis updates Hieronymus Bosch’s famous triptych in her Garden of Emoji Delights replacing medieval religious symbolism with an emotion-inspired iconography of the 21st century. Alan Sondheim’s Avataurror are 3D printed avatars representing distorted, wounded, problematic bodies and their relationship to states of violence and genocide, where cracks and wounds are eternally everywhere and nowhere. Simon McLennan’sDrawings reflect intimate contradictions in our dysfunctional society showing us daily mutations. When the artist and open-source engineer Salvatore Iaconesi, one of the artist duo AOS (Art is Open Source), was diagnosed with cancer he launched a participatory open source initiative to find a cure. The resulting global art performance La Cura explores the complexity of being human and seeks to find ways to reclaim our bodies in collaboration with others. The exhibition considers the roles of our arts and science traditions, and how they are played out while examining: governance, posthumanism, biohacking, and biopolitics.

This exhibition is produced in partnership with LABoral, in Gijon, as an extension of the Monsters of the Machine exhibition 18 Nov 2016 – 21 May 2017. Based on Mary Shelley’s classic novel Frankensteinwritten 200 years ago which continues to offer a lens through which to examine current practices in arts and technology and how they shape society today.

Anna Dumitriu – Microbe Mouth

Carla Gannis – Garden of Emoji Delights

Simon McLennan – Drawings

Alan Sondheim – 3D Printed glitch avatars & Landscape tablets, 2 Glitch videos

AOS (Art is Open Source) Salvatore Iaconesi & Oriana Persico – La Cura

Alan Sondheim – Presentation

Wednesday 5 July 2017, 6.30 – 8.30pm

Furtherfield Commons, Finsbury Park

FREE

Artist Talks: Carla Gannis and Alan Sondheim

Monday 10 July 2017, 6:30 – 8.30pm

CAS, Davidson House, 5 Southampton Street, London WC2E 7HA

FREE – booking essential, strictly no late admittance (register)

[1] Robert Graves. Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology. Paul Hamlyn, London. 5th Edition, 1964. P.92.

[2] Body Drift: Butler, Hayles, Haraway (Posthumanities). Author Arthur Kroker. University of Minnesota Press (22 Oct. 2012).

[3] Body Drift: Butler, Hayles and Haraway. Review by Marc Garrett 15/08/2015.

The exhibition draws upon ideas originally written in an essay Prometheus 2.0: Frankenstein Conquers the World! Marc Garrett.

Alan Sondheim has been ploughing a very singular furrow through art, music, writing, philosophy and much else since the late sixties. On the occasion of his participation in the Children of Prometheus exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery we present here an interview conducted by the artist and writer Michael Szpakowski in which Sondheim gives a broad overview of his artistic formation, practice and philosophy.

Michael Szpakowski: I first came across your work through the Webartery mailing list in 2001. I remember being knocked out by your productivity, a productivity that seemed to be allied to an incredible intellectual curiosity and restlessness, resulting in in words, images, movies, music – I remember once you started making little programs in some variant of Visual Basic… All of these posted day in, day out, come rain or shine, to the list… And, obviously I preferred some to others and for anyone to follow every piece of work you made would mean doing little else with their lives, but the quality, the variety, of what you made was ( and remains) staggering.

I found this compulsion to make work both admirable and invigorating and I’ve followed your work ever since. I think I even once compared you to Picasso on DVblog because I couldn’t think of anyone working in art for the net (and every such description is problematic, I’ll ask something more specific later) who seemed to come anywhere near to that fecundity allied to quality too…

I think of this interview as a general introduction to your work for someone who maybe has only happened across it for the first time in the exhibition at Furtherfield so I’d like to ask, first of all, for you to give us a sketch of your intellectual and artistic formation and the milieu(x) in which you have worked (I mean right from the beginning – tell us what makes you, you!):

Alan Sondheim: Of course this is difficult to answer; I began with writing and around the age of 19, started making music as well, but I was always restless. The compulsion has personal roots, but also a desire to move into an environment, habitus, and explore its limitations and promises; in all of this, I’m concerned with the interplay of the somatic and consciousness on one hand, and abstraction, the inertness of the real, mathesis (the mathematization, structuring of the world) on the other. So there’s this dialog at the limits. My first production was a book of experimental writing, An,ode ; around the same time I made three recordings, two for ESP-Disk; this was around the late 60s. Clark Coolidge, the poet, was very important to me early on; I met him at Brown; he introduced me to Vito Acconci and shortly after, early 70s, I moved to NY, eventually SoHo in its heyday. I’ve never been a traditional artist/writer/musician/etc. but move among these areas; I’m concerned with what for me are fundamental issues of philosophy, body, and the world. I want to explore at the limits of what I’m capable of doing. How is consciousness in relation to the world? How is the world?

I’m driven to create daily; while teaching at UCLA, I made a sound film (16mm for the most part) a week for 37 weeks; they ranged from a minute to an hour in length and were forms of deconstructed narrative. Now online, I try to make a work daily in whatever medium, including virtual worlds of all sorts; I continue to try to push limits – what I call ‘edgespace,’ – the space where gamespaces/worlds begin to break down, and what then? (By ‘gamespace,’ I mean, literally the space of a game, where rules hold – for example chess or football. The rules may be consensual or enforced, etc.) This is deeply involved with the politics and somatics of these spaces of course, and on the political spectrum, I’m leftist and deeply pessimistic; I don’t see internet or social media as salvation of any sort, but as fundamentally neutral, extraordinarily adaptable to any number of usages. I’ve written on the differences at the finest levels between the analog and digital, areas like that usually taken for granted; what emerges is a kind of granularity situated within an obdurate real world whose biosphere is faltering deeply.

M: Although you are included in an exhibition in a physical space here the vast majority of your output has been presented on the net, usually in the context of one or more mailing lists. Could you say a bit about this. Was this a conscious choice or pragmatism or somehow both? Is there anything you particularly prize about the rhythm of work and presentation that comes with this kind of platform and has the eclipse of many of the old mailing lists with the rise of social media caused problems for you – have you tried to adapt to/utilise these newer modes?

A: It’s pragmatism combined with a desire to explore; edgespace teeters uneasily and tends towards what I call blankspace, where the imaginary exists – for example, the ‘heere bee dragonnes’ in unknown areas of early maps (I haven’t actually seen the expression, but it serves here). I present my work on Facebook and G+; I also used YouTube for a long time until I was banned from it.

M: Banned from it?

A: A long story that would take this too far afield…

I work well in presentation/talk/performance mode online and off. I believe in the depth of email lists of course. I do think my avatar work is really well suited to gallery spaces; I’ve had up to seven projections going at the same time. I’ve also performed live in virtual worlds or mixed-reality situations which are projected/presenced directly, and for a long time Azure Carter, my partner, and I worked with the dancer/performer/choreographer Foofwa d’Imobilite; the physicality of the work was amazing. And another aspect of what I do – what grounds me – is playing musical instruments, mostly difficult (for me) non-western ones; the instruments require tending and close attention. I tend to play fast. Most of them are strings, bowed or plucked; the music is improvisation. Recently I’ve been focusing on the sarangi, for example. And I’ve had something like 17 tapes, lps, and cds issued; the most recent is LIMIT, which was done in collaboration with Azure and Luke Damrosch, who did Supercollider programming based on concepts I’ve had about time reversal in real time – an impossibility in gamespace, but the edgespace is fascinating. The music products excite me; they’re out there in a way that my other work isn’t.

M: I remember when I first discovered internet art or whatever we want to call it (and there have been numerous quasi theological arguments about this) that there was an intense debate about whether the internet was a conduit or a medium – so many artist-scripters/programmer tended to rather look down on those who simply took advantage of the network’s distribution and dialogical properties (although I have to say that my view is that it was in this massive extension of connectivity that the real force of the thing resided – I remember being told in 2001 that moving image was not internet idiomatic which is amusing given the rise of YouTube &c.) Your work, certainly of the last 17 years or so, strikes me as being intimately tied up with the network and with the unfolding possibilities of new media but not necessarily in the sense that you work with the network itself to make objects, works and more in the second sense of the conduit…

A: It depends; for example one of the projects I initiated through the trAce online writing community in 1999-2000 – over the hinge of the millennium in other words – was asking a world-wide group of artists, IT folk, etc., to map traceroute paths and times from the night of 12/31 to the afternoon of 1/1; the internet was supposed to run into difficulties – over timing etc. – and I wanted to create a picture of what was happening world-wide. A second project somewhat later was using the linux-based multi-conferencing Access Grid system to send sounds/images/&c. from one computer to another in the Virtual Environments Lab at West Virginia University – but these images would travel through notes, much like the old bang!paths, around the entire world. So, for example, Azure would turn her head in what seemed like a typical feedback situation – the camera aimed at a screen, she’s in front of it, the result’s projected on the screen, &c. – but each layer of the feedback had independently circled the globe (through Queensland to be specific), creating time lags that also showed the ‘health’ of the circuit, much like traceroute itself. It was exciting to watch the results, which were videoed, put up online with texts &c.

Part of the difficulty I have is being deeply unaffiliated; I need others to give me access to technology. For example, I’ve used motion capture in three different places, thanks to Frances van Scoy and Sandy Baldwin at WVU; Patrick Lichty at Columbia College, Chicago; and Mark Skwarek at NYU. I also did some augmented reality with Mark, and with Will Pappenheimer. To paraphrase, I’m dependent on the kindness of others; I have no lab or academic community to work among in Providence; what I do is on my own. John Cayley gave me access to the Cave at Brown; Eyebeam in NY (I had a residency there) gave me space and equipment to work with, and in both places I was able to create mixed reality (virtual world/real bodies) pieces – those also bounced through the network…

M: Could you talk, then, a bit about the motion capture/avatar work that seems to have been central to what you are doing over the last ten years or so. I also don’t think I’m mistaken in detecting a very decided move back to music making of late (I know this has always been there but it feels foregrounded again)

A: The mocap work has been ‘deep’ for me; it involves distorting the entire process, in other words distorting the somatic world we live in. There are numerous ways to do this; the most sophisticated was through Gary Manes at WVU, who literally rewrote the mocap software for the unit they had. I wanted to create ‘behavioral filters’ that would operate similarly to, say, Photoshop filters; in other words, a performer’s movement would be encoded in a mocap file – but the encoding itself during the movement itself, would be mathematically altered. Everything was done at the command line (which I’m comfortable with). The results were/are fantastic. A second way to alter mocap is by physically altering the mapping – placing the head node for example on a foot. But I worked more complexly, distributing, for example, the nodes for a single performer among four performers who had to act together, creating a ‘hive creature.’ All of this is more complicated than it might sound, but the results took me somewhere entirely new, new images of what it means to inhabit or be a body, what it means to be an organism, identified as an organism. This is fundamental. I’m interested in the ‘alien’ which isn’t such of course, which is blankspace. (The alien is always defined within edgespaces and projections; we project into the unknown and return with a name and our fears and desires.)

Most of what I do, for me all of what I do, is grounded in philosophy – ranging from phenomenology to current philosophy of mathematics to my own writing. So these explorations are also artefactual; I think philosophy is far too grounded in writing as gamespace; writing for me, when it’s touched by the abject, the tawdry, the sleazy, the inconceivable, opens itself up.

As far as music goes, I touched on it above in regard to LIMIT. One thing that concerns me is speed, playing as fast as possible, so that the body and mind move on de/rails that are at my limits; I think of this as shape-riding and the results and internal time dilations involved keep me alive…

M: You are genre/practice/technique promiscuous and you have a high level of skill in all –you could equally (and have been) styled Alan Sondheim ‘writer’ , Alan Sondheim ‘musician’, Alan Sondheim ‘maker of moving image work’ (with a marvellous sub-category ‘Alan Sondheim ‘maker of dance related video works’, for a while). Is one of these, in your heart of hearts, central, and, whether this is so or not, how do you place yourself in respect to the various traditions around these areas of work. How do you fit into the art world, into literature or the experimental film tradition? How do you relate to net art/networked art/new media &c.?

A: I don’t seem to fit into the artworld, net art, poetry world, music world &c. – it’s difficult for me to get my work around as a result. Nothing is central but a desire to see how systems form, coagulate, degenerate, collapse, become abject, &c. in relation to consciousness: How are we in the world? On a concrete level, finance enters into the picture; what can I do given a kind of lack of community around me? How can I push myself?

I’m not sure what ‘net art’ is, but certainly the Access Grid pieces &c. are of that, although not of Web-based protocols. There are so many ports out there to use! I do think of myself as a new media artist or someone burrowing into post-media. I’ve always had a few people who believe in what I do, who have helped or worked with me, and I’m really grateful for that. But in terms of institutions, I feel like an outsider artist and am treated like one. It came to a head for me years ago one day when I was living in Soho; I had a call from Vito who said he had realized that whatever I am, I’m not an artist; the same day Laurie Anderson spoke to me and said she realized that whatever I am, I am an artist. So my identity has been far more fluid than I’ve been comfortable with, and it’s affected my career. (There was that tape Kathy Acker and I made 1974, and I read an interview a few years ago, forget the source, with Edit Deak who said the tape wasn’t art at all; in the meantime, it continues to be shown at various venues.)

M: Finally, could you say a little about the work in this particular show?

A: The work in the show is a group of 3d-printed avatars distorted through the mocap process described above. For me they connect, deeply, with charred bodies, with anguish, with genocide and scorched earth. They appear also in number recent videos created in various virtual worlds, moving/performing etc. The anguish, so close to death and unutterable pain, is there. I’ve talked about the kinds of brutal killings occurring now worldwide, from Finsbury Park to the United States, the rise, not only of racisms, but violent nationalisms, in the U.S. certainly encouraged by the present regime. I’m sick of it. We all have nightmares. I want to understand this, this grounding in the blooded earth that shakes our very ability to speak, to think, to act.

And yet of course we must resist.

The work in the show is also critical, then, of technophilia, technological answers to the world, utopian dreaming. The top one percent benefit most from the results. I see utopian thinking as dangerous here. Our so-called president has his finger on 4000-5000 nuclear warheads. That’s the reality for me, and why I don’t sleep at night.

Michael Szpakowski: 聽琴圖 (listening to [Alan Sondheim playing] the qin), after Zhao Ji

// gravure, urushi lacquer & pigment on found wood // 30.5X7.5″

Part of the NEW WORLD ORDER exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery

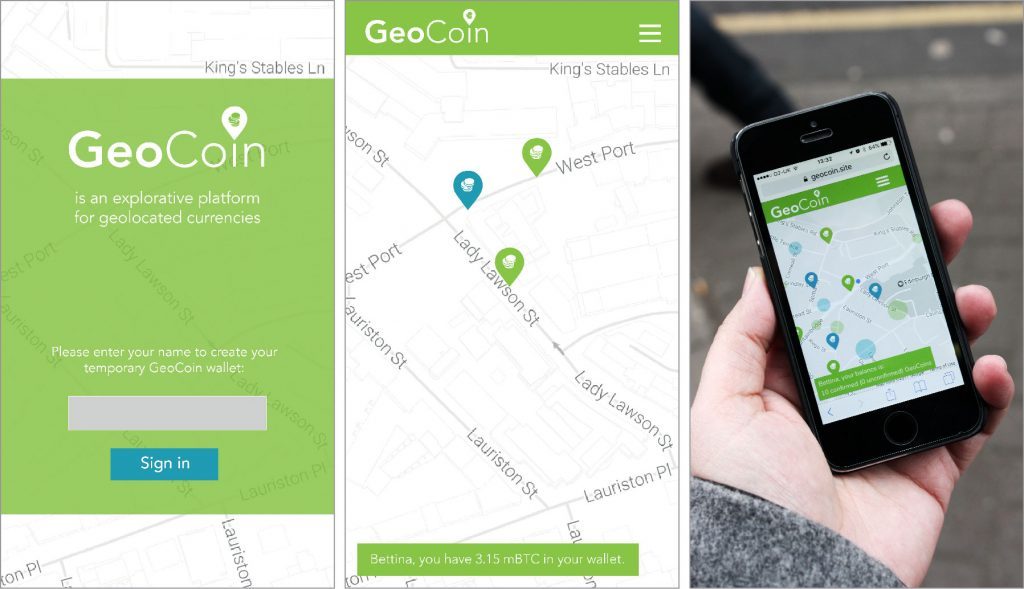

BOOKING ESSENTIAL – Limited places available for this FREE workshop

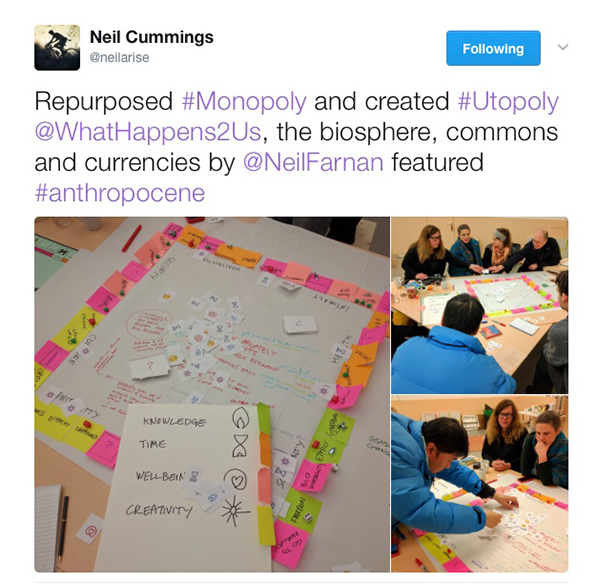

A day of design-based research using the GeoCoin platform to explore novel ways of reconsidering and reinventing currency through location-specific value transactions. How can money be reprogrammed to interact with or react to everyday practices of value exchange in and around the city? Explore these and more questions with the Design Informatics team from the University of Edinburgh.

This workshop is part of the ESRC funded research project After Money lead by Design Informatics at the University of Edinburgh.

Saturday 24 June, 11-1pm and 2-4pm, Furtherfield Gallery

Ever wanted to join your partner in bitcoin matrimony? Or wanted to join another partnership for a short time only? You’ve come to the right place. For this day only, you can record your short-term bitcoin union via Handfastr on the blockchain in an immutable and ever growing ledger of bitcoin marriages at the Furtherfield Gallery.

This project is part of the ESRC funded research project After Money lead by Design Informatics at the University of Edinburgh.

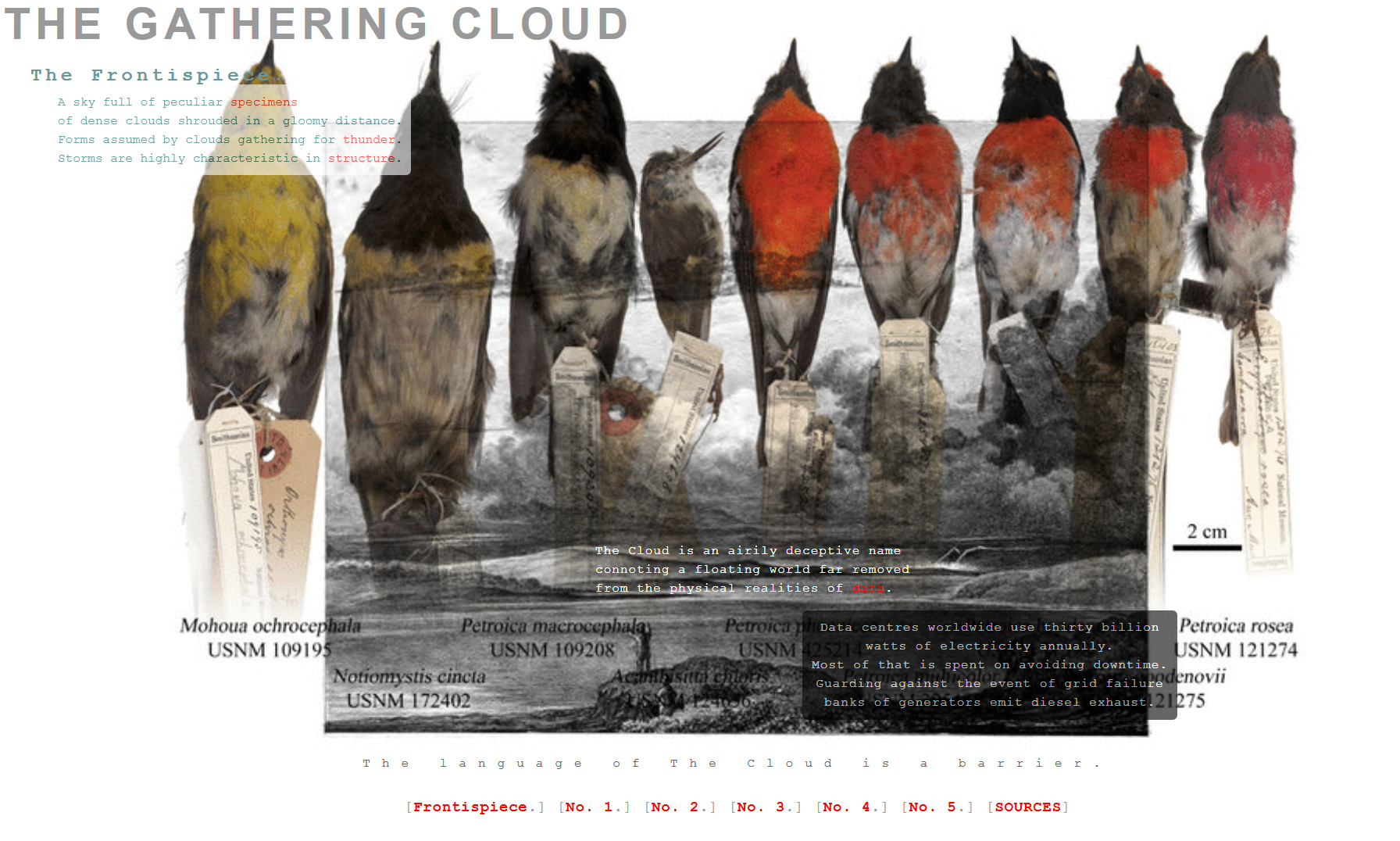

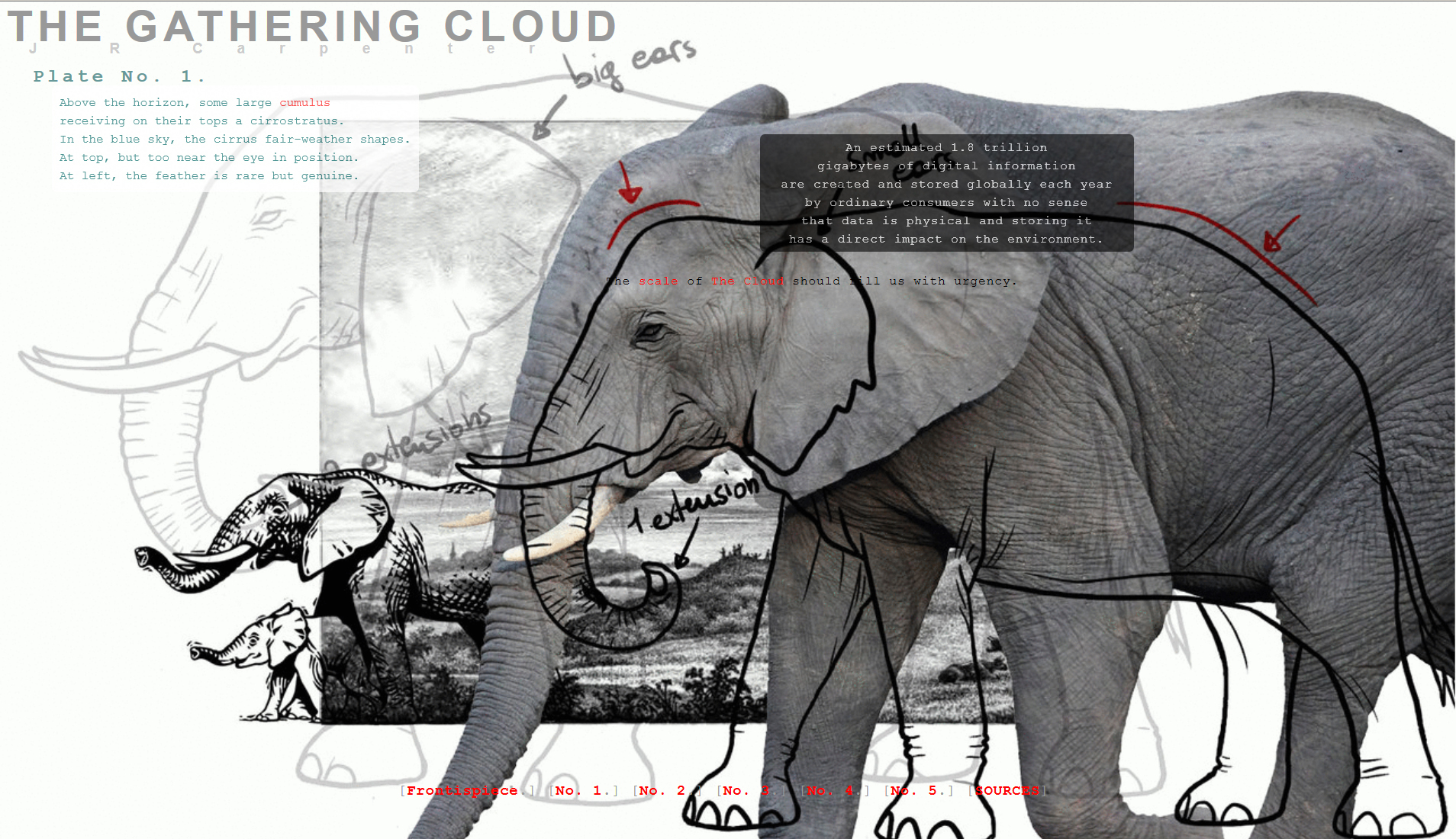

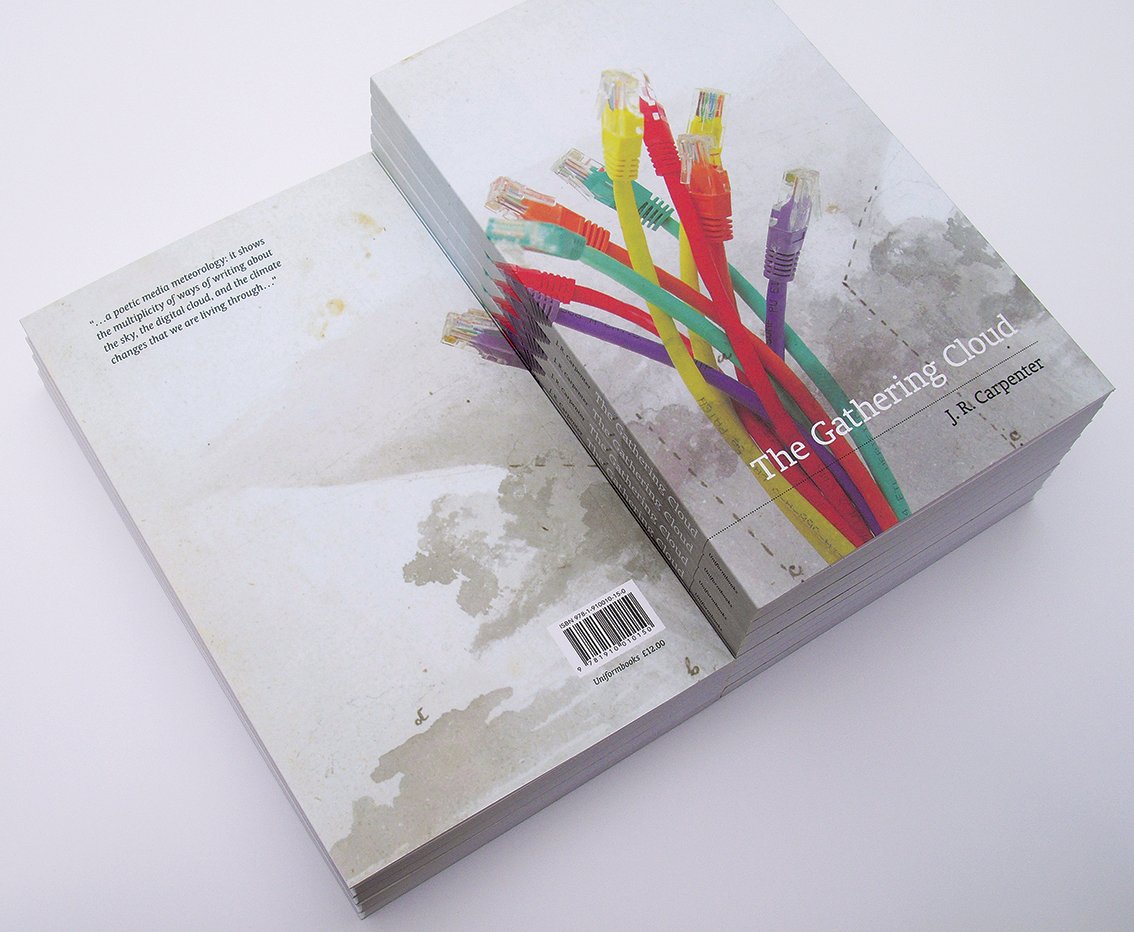

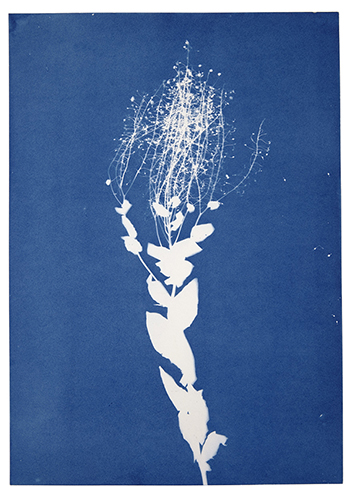

The Gathering Cloud makes slow reading. Let’s start with the title. It trips off the tongue, doesn’t it? Rolls around in the mind like a marble you’ve had since childhood. But there’s something unfamiliar about it, too. ‘The gathering cloud’ evokes a threat – the gathering crowd, perhaps; words haunted by expectation; a riot just about to begin. The gathering cloud sounds material and immaterial at the same time. It could signal rain, or warmth, or happiness for shepherds and fishermen, if only you knew how to read it. Could the ancients interpret celestial data? Can Google analysts do it now?

Every sentence in JR Carpenter’s literary artwork, The Gathering Cloud, is as resonant and expansive as its title. The work is so full of meaning, in fact, that it pushes beyond its own borders. Both a piece of digital literature commissioned by Neon Digital Arts Festival, and a book published by Uniform Press, The Gathering Cloud hovers, as an aesthetic experience, in between (it also exists as a printed A3 zine, distributed in more informal ways).

Its theme is climate change. Or, more precisely, the material effects of technologies euphemistically named ‘cloud computing’ on the health of the planet. Or the systems of knowledge that reveal and obscure our relationships to our world. Or the impossible responsibility of human actions that have a global impact. Or, in Carpenter’s characteristically succinct language in the afterword (‘Modifications on The Gathering Cloud’):

The Gathering Cloud aims to address the environmental impact of so-called ‘cloud’ computing and storage through the overtly oblique strategy of calling attention to the materiality of the clouds in the sky.