This article is co-published by Furtherfield and The Hyperliterature Exchange.

Millie Niss, the writer and new media artist, died of swine flu with complications at 5 a.m. on 29th November 2009. Her mother and longtime collaborator, Martha Deed, was with her then. She had been in hospital for four weeks, mostly in intensive care, after picking up the virus, which quickly became serious in her case, probably because she already had respiratory difficulties due to a rare condition known as Behcet’s Disease. She was 36 years old.

The news would have been sad to hear about anyone, but it was especially sad in Millie’s case because she was one of the people in the new media community with whom I felt particularly close. I met her at the trAce “Incubation” conference in Nottingham in 2004. When I first arrived at the conference, I was directed to the part of the room where Michael Szpakowski was because he and I had already struck up an e-mail friendship, and he’d left a message for me at the door. I found him talking to Millie. Michael was only there for that first evening because he had to go and see his father, but Millie was there for the rest of the conference, and I sat next to her at many events. She was dark-haired, overweight and funny: very easy to talk to. Later in the conference, she gave a presentation about how to attach behaviours to objects in Flash, which I attended along with Jim Andrews and others. She kept saying beforehand that she was feeling pretty nervous about it, but she seemed very natural and nerveless when it came to the event. In the beginning, she asked for suggestions from the audience – I think for an initial idea on which to base her Flash piece – and at first, nobody said anything. She suddenly became acerbic – “Oh come on – don’t make me pick on someone like you were a bunch of school kids!” Immediately you could see her as a teacher and imagine how she would have controlled a classroom. I suggested spiders, which set the ball rolling, and from that point onwards, everything went very rapidly. She quickly and expertly demonstrated how to set up a drawing of a spider as a symbol, and attach a behaviour to it so that when the mouse pointed to it, a sound file played. Another thing I remember was that she was very critical of certain aspects of Flash – how you had to import things into your library and then drag them from the library to the stage before you could do anything with them. You could feel her personality’s force, her opinions’ sharpness, and her sense of humour and fun.

From that time onwards, she and I regularly exchanged e-mails. She knew that I worked in the National Health Service, and because she was very much in the mill of health care herself, we had some lengthy correspondence about how the UK system worked, compared with how things worked in the USA. She also sent me two glass unicorns through the post – occasionally, she would run little competitions on her “Sporkworld” website and offer glass unicorns to participants as prizes. The first of these unicorns went to my daughter Rachel, and the second is still sitting on my study window-ledge in a white cardboard box. He used to stand out on his own four feet, but unfortunately, he had an accident with the curtain, and one of his legs got knocked off. I stuck it back on with Superglue, but it fell off again. Millie knew all about this, and I sent her a photograph of the unicorn on my window-ledge – I think I even sent her a second photograph, showing how he looked after his accident and temporary repair. She was always very interested in Rachel and liked to hear my stories about her. Perhaps they reminded her of her childhood, or perhaps she just liked kids.

One thing which came across from Millie’s correspondence, as well as from her work and her occasional online commentaries, was her sense of perspective on new media art. She was grateful to it because it provided an outlet for her creativity which she had never managed to find through traditional print; but all the same, she remained aware that it was a small and specialised field and that a good deal of new media work might seem incomprehensible to “ordinary” people. Her comments about other new media artists reflected this grounded attitude. She preferred work which didn’t reach for the hi-tech solution that a lo-tech one would do – work, in other words, which didn’t employ technology for its own sake, and where the form was dictated by content rather than the other way round. Likewise, she wasn’t particularly bothered whether her output complied with the dictates of new media theory – whether it was interactive, non-linear, coded or networked. The pieces on her website exhibit a cheerful mixture of genres and media: Flash, video, poetry, prose, photography, sound files and plain old HTML rub shoulders in much the same way that political commentary, literary criticism, observations of places and people, food appreciation, nature notes, raucous humour and occasional obscenity rub shoulders in her blog. The groundedness of her art, and her sense of responsibility towards her audience, is demonstrated by the way in which she habitually presented videos on her site in different sizes and resolutions – for example, “Warhol’s Campbell’s Brodo” is available 8.85mb, 6.23 MB and 2.43 MB – so that people with slower connections could sacrifice a bit of quality to save a long wait if they so desired. Similarly, her introduction to “Warhol’s Campbell’s Brodo” explains that “brodo is the Italian word for soup and the restaurant’s name”. Without talking down to her audience or limiting what she wanted to say, she was always at pains to be as clear and user-friendly as she could – and this insistence on clarity and user-friendliness, her desire to reach out to an audience of “ordinary” people whenever possible, was one of the things which made her voice such a distinctive and refreshing one in the new media world.

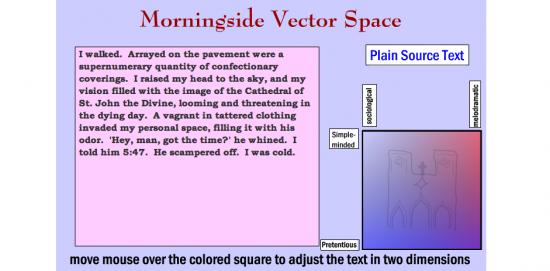

However, this is not to say that she was any Luddite or uninterested in the theory of any description. One of her best-known pieces of work – a collection of six pieces – is the Oulipoems, reproduced in Volume One of the Electronic Literature Collection in 2006. As Millie explains in her introduction, “Oulipoems is a series of six interactive poetry Flash works… loosely based on the Oulipo movement in French literature, which focused on texts based on constraints… and also on mixtures of literature and mathematics.” One of the Oulipoems is “Morningside Vector Space”, which rewrites a description of a simple incident in various ways, depending on how we move the mouse cursor over a coloured square. The source text reads:

Yesterday, I was walking on Amsterdam Avenue. There were cracks in the sidewalk. I looked up and saw the tall and unfinished Cathedral of St. John the Divine. A man approached me. ‘Excuse me, do you have the time,’ he said. I told him at 5:47. He walked (sic) away. It was windy. The coloured square is marked to indicate the inflexions this text will be given if we hover over different areas – from “Simple-minded” to “Pretentious” on the x-axis and from “Sociological” to “Melodramatic” on the y-axis. If we point to the “Simple-minded” corner, we get this:

I walked. On the sidewalk. By the big church. There was a man. He wanted the time. I gave him my watch. He left. I was cold.

The intersection of “Pretentious” with “Melodramatic” yields this:

A vagrant in tattered clothing invaded my personal space, filling it with his odor. ‘Hey, man, got the time?’ he whined…

The intersection of “Pretentious” with “Sociological” produces:

The sidewalk, unmaintained by the municipality, contained evidence of substance abuse…

– and so forth.

A number of observations come to mind about this piece. First of all, although it isn’t tremendously technically sophisticated, it does reveal a very competent grasp of Flash and object-oriented coding. This grasp is also displayed in many of Millie’s other pieces. Secondly, it demonstrates the “mixture of literature and mathematics” to which Millie refers in her Introduction to the Oulipoems – the idea that different styles of writing can be mapped onto a graph and summoned by pointing at different vectors – and in doing so, it demonstrates a willingness to experiment with text, and an openness to the idea that text in digital literature may sometimes be manipulable by the audience, rather than fixed into a single unquestionable form by the author. Thirdly, “Morningside Vector Space” is funny and accessible. The labels with which Millie marks out her vectored space are humorous, and the texts with which she illustrates these different writing styles are exaggerated for comic effect. At the same time, there is an undercurrent of social observation, with a suggestion of political edge: “I was observing a mixed-income neighborhood on the borders of a low socioeconomic enclave… Lacking funds for a watch, he had to rely on others in the community to be on time for his appointment with the social services…”

Lastly, perhaps least obvious is a powerful sense of place. The piece’s title refers to Morningside Heights, an area of Manhattan in New York. The texts allude to Amsterdam Avenue, a street in Morningside, and the Cathedral of St John the Divine, which stands there. St John the Divine is also known as St John the Unfinished because although it was begun in 1892, it remains incomplete to this day – hence the description of the cathedral as “tall and unfinished”. The coloured vector space in Millie’s piece contains another reference to the cathedral, in the shape of a wobbly but recognisable line drawing of its facade. This sense of place is an important aspect of Millie’s output – not only in videos about places such as “Jewel of the Erie Canal” or “A Hecatomb in Cheektowaga” but also in new media works such as “The Talking Escalator at Penn Station”and “Unscenic Postcards” – and like her interest in politics, it demonstrates her commitment to the “real” world, as well as her talent for observation and comment.

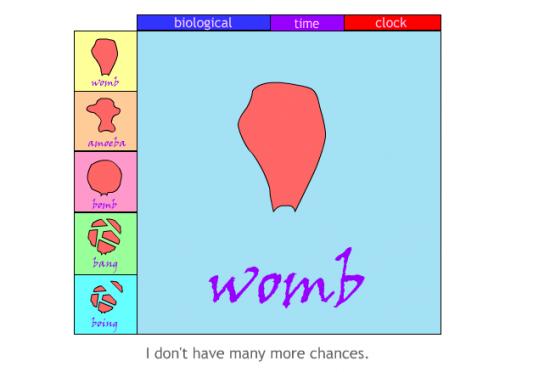

Another of Millie’s Flash pieces, and one of her most personal artworks, is “Biological Time Clock”. In a central pane, the words “womb”, “amoeba”, “bomb”, “bang”, and “boing” appear, accompanied firstly by Millie’s voice intoning the same words, and secondly by drawings of a womb, an amoeba, a womb inflated to the point of bursting, a womb breaking into pieces, and another slightly different drawing of a womb in bits. Underneath this pane appears a randomised sequence of phrases, arguing both for and against getting pregnant and giving birth: “It’s not for me”, “I’d be nurturing”, “I’m more than a womb”, “I’m not together enough”, “maybe I should do it while I can”, and so forth. There are also buttons that allow you to add extra sound effects, such as Millie saying “tick-tock” or chanting “biological”.

There are feminist aspects to the piece – one of the anti-pregnancy phrases is “I don’t want to be a breeding cow”, and another is “I’m more than a womb” – mixed with what seem to be more autobiographical notes, such as “why am I alone?” and “I don’t want to lose my creativity”. However, a question that seems to go to the heart of the piece is what is the word “boing” doing in there? The drawing which accompanies this word is enigmatic. Still, it may be meant to suggest that the womb, which broke apart at “bomb”, is now somehow bouncing back together again – and by implication, that no matter how many times the author talks herself out of childbirth, her consciousness of her womb keeps coming back to bother her afresh. But the word “boing” serves another purpose by introducing into the piece the quirky, unpretentious, comical note essential to Millie’s art. If the word sequence at the heart of the poem were simply “womb, amoeba, bomb, bang,” then both the message and the tone would seem much starker. With “boing” on board, there is a playful and funny element to the piece, a release from serious description into exaggeration, which seems to suggest that Millie herself isn’t taking it completely seriously, and we don’t have to take it completely seriously either.

In some ways, this insistence on the quirky and the wacky might be considered a weakness or a limitation in Millie’s art, flinching away from completely direct and honest engagement with her subject matter, symptomatic of a tendency to let both herself and her audience off the hook, especially if her subject-matter happens to be personal. But it should be borne in mind that Millie had more personal subject matter to deal with than most of us, and her insistence on humour was an essential part of her strategy for dealing with it. One of the anti-pregnancy arguments on “Biological Time Clock” is “I’m not well…” and it is impossible to write about Millie’s art without taking her mental and physical ill health into account, if only because so much of her art deals with it. For many years she was considered – and considered herself – to be mentally ill with Bipolar Disorder. Millie’s experiences of mental illness and the health and social care professionals with whom it brought her in contact are memorialised in “The Adventures of Spork, the Schizophrenic Skua”. As described on Millie’s site:

Millie Niss created Spork… to be a sympathetic and intelligent character who was also an indigent client of the mental health system. The cartoons began to express frustrations about how mentally ill people and welfare recipients are treated, but later on, other issues and pure silliness were added to the Spork series.

Eventually, after years of treatment for mental illness, Millie was diagnosed with Behcet’s disease, a severe disorder of the immune system which can cause depression along with ulcers, skin lesions, stomach problems and inflammation of the lungs. Before this diagnosis, however, she suffered attacks of dangerously acute depression, and one part of her website is devoted to suicide (http://www.sporkworld.org/suicide). The way in which she tackles this subject makes it clear how her sense of humour, far from demonstrating an unwillingness to confront her inner demons, was really evidence of her mental toughness and self-discipline in dealing with them – a refusal to give in to self-pity:

I was often, very often ready to kill myself, but I hate guns and wouldn’t want to use one. And lying on a gun license application was out of the question: I would not sign my name to a paper which said I was not intending to kill myself or was not mentally ill… Hanging was reputed to be painless and so we thought getting sentenced to death was the perfect out: that way you could have the benefit of dying without the guilt of doing it to yourself. It was unfortunate that you had to do something awful to get sentenced to death, though… A big question was the suicide note. Should you leave one or not, and if so what should you say in it? The argument for not leaving a note was a strong one: someone might find the note and stop you from doing it… The desire to write a suicide note that was a literary masterpiece kept me alive at times. I couldn’t kill myself until I thought of something good enough.

In these passages, Millie combines a sharp, satirical, almost gleeful insight into the ironies and self-contradictions of the suicidal mindset with an understated – but nevertheless essential and genuinely tough – conviction of her individuality and status as an artist. As she insists in “Biological Time Clock”: “I have a brain”, “I’m more than a womb”, and “I don’t want to lose my creativity”. In “Suicide”, the idea that she doesn’t want to kill herself until she can devise a sufficiently well-written suicide note is a good joke at her own expense. Still, it also points to something deeper: her writing is her way of dealing with depression and her reason for not succumbing. It gives her a sense of self-worth, and the discipline of art allows her to detach herself from her feelings and sublimate them, thereby gaining some form of control over them.

In an article entitled “Suicide, Art, and Humor”, which she published on Michael Szpakowski’s website “, Some Dancers and Musicians”, Millie wrote that “The artist has a duty, some might say, to produce art. But with that comes the more fundamental duty to stay alive.” This is a typically grounded remark: the artist’s duty to life is “more fundamental” than her duty to art. Referring to her own “Suicide” piece, she goes on: “I was at least trying to be funny… Art is a force that tends towards life… While you are writing a despairing poem, you are, in the act of writing, temporarily suspended from the act of despairing.” The effort to be funny and thereby entertain an audience, art as an affirmation of life, and art/humour as a defence against despair – all of these ideas were essential to Millie’s work.

The same values are apparent on the Sporkworld Microblog, which Millie shared with her mother, Martha Deed. They are present even in the very last days of her final illness. Here is an entry from 16th November: “We like to keep a chipper tone here, and we do not intend this to be a place to list complaints. We also insist that any personal events must be… transformed from raw anecdote into something with literary intent.” Martha actually wrote this, but Millie approved it, and it reflects a shared philosophy that runs right through the site’s contents. “Raw anecdote” is inadmissible, not only because it may lack the “chipper tone” that the Microblog seeks to maintain, but because it also lacks the discipline and detachment of real art. The word “raw” suggests something of the harshness of unfiltered experience. The artist’s job is not to pass on this harshness to the audience direct and unmediated, but to control it through an effort of will, to fit it into a composition, to comment on it, reason about it, make jokes about it and turn it into an element in discourse; and thus to humanise it.

After Millie’s death, Martha published a poem on the Microblog entitled “Travelling with H1N1”, which contains the following lines:

even if it is difficult to be funny

while intubated, you will fight and fight and fight…

you will be sending email on your way to the fluoroscope

with subject lines like

I never thought I would write email while intubated”…

The sense of humour, the refusal to give in, and the determination to fight back against her difficulties by finding something to say about them were all there until the very end. Martha relates that in the intensive care Unit (ICU), although she couldn’t speak because she was on a ventilator, she kept her lines of communication open by writing things down. She struck up a friendship with a nurse supervisor, Tom, who “was astonished at her ability to tolerate the ventilator and keep up a running conversation in her notebooks… He continued to visit her in the ICU and received her candid evaluations of her care there – both good and bad – and he found her to be very funny and brave.”

Mentioning the Sporkworld Microblog, and the fact that it was shared with Martha Deed, brings us to Millie’s frequent and long-term collaborations with her mother. Millie is known as “Spork Major” on the Microblog, while Martha is “Spork Minor”. Apart from the blog, they collaborated on many other works – Martha co-wrote the “Oulipoems” texts, for example, and “Jewel of the Erie Canal” is credited to them both. But one of the largest, most ambitious and most formally developed of their collaborations is News from Erewhon, a series of parallel surreal fictions created by the process of “guided free association”.

News from Erewhon is by no means a perfect work of art. Firstly, the title makes a rather distracting reference to Samuel Butler’s satirical, pseudo-Utopian novel “Erewhon”, which doesn’t really seem to have much to do with the rest of the book. Secondly, each chapter is accompanied by a number of images which zoom up in front of the words and then quickly fade away to allow us to read on. The Introduction argues that these add “another level” to work and that the pictures “appear only briefly to affect the viewer in an almost subliminal manner”. In fact, their main effect is to make you lose your place. Luckily, Millie provides a button which allows us to switch the images off.

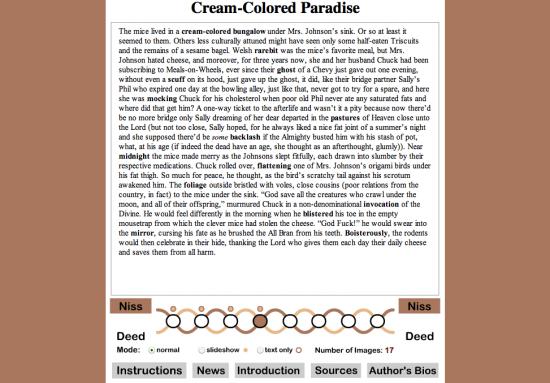

Nevertheless, the texts themselves are fascinating. They were written in an almost Oulipo-like manner. Several words were picked randomly from chosen books; then, using these words as “seeds” and incorporating them into their writing as they went along, both Millie and Martha produced a series of eight “miniature fictions, situated halfway between poetry and prose”. As the Introduction says, these fictions suggest “a bizarre alternate universe, whose characters and settings evoke themes such as war and peace, the workplace, and religion. These themes… weave in and out of the texts like strands in a braid. The two authors can also be seen as separate, interacting strands.” The image of strands in a braid suggests both the closeness with which Martha and Millie were able to work together and the fact that they always retained their distinct identities and styles, and News from Erewhon is a good demonstration of this. Millie’s sections are generally longer than Martha’s and more narrative in style, whereas Martha’s tend to be more surreal and poetic. Both, however, display a constant flow of inventive wit. One of the funniest of the lot is Millie’s fourth:

The mice lived in a cream-colored bungalow under Mrs Johnson’s sink. Or so at least it seemed to them. Others less culturally attuned might have seen only some half-eaten Triscuits and the remains of a sesame bagel… “God save all the creatures who crawl under the moon, and all of their offspring,” murmured Chuck in a non-denominational invocation of the Divine. He would feel differently in the morning when he blistered his toe in the empty mousetrap from which the clever mice had stolen the cheese. “God Fuck!” he would swear into the mirror, cursing his fate as he brushed the All Bran from his teeth.

Seed-words for the passage are shown in bold. Here is an extract from Martha’s equivalent passage:

A cream-colored bungalow? How could you? It will curdle in the sun, and this is July, she said… Your invocation of natural disasters has blistered the mirror of my mind, he moaned.

Both writers, it will be noted, start by cheating: instead of introducing the “cream-colored bungalow” into their stories in a literal-minded way, they bring it in obliquely. Martha imagines a bungalow, not the colour of cream, but actually painted with cream on the outside – hence the objection that “it will curdle in the sun” – while in Millie’s story, the bungalow only exists at all in the collective imagination of a family of mice. Martha sticks more closely to an underlying structure suggested by the seed words, producing a more densely written text and poetic texture. This is particularly evident in the alliteration – “colored”, “could”, and “curdle” or “mirror”, “mind”, and “moaned”; but also in the lilting rhythm – “Your invocation of natural disasters has blistered the mirror of my mind, he moaned”. Millie, on the other hand, shows something of the novelist’s delight in incidental detail – “Triscuits”, “sesame bagel”, “under Mrs Johnson’s sink”, and “he brushed the All Bran from his teeth”. Her passage seems to take a serious turn with the phrase “God save all the creatures who crawl under the moon” – simultaneously poetic, literary and religious – yet this moment of gravity is almost immediately reversed by an explosion of comical blasphemy – “God Fuck!”

It would be too simplistic to suggest that Martha was always the more focused and disciplined partner in collaborative work. It should be remembered that Millie was the techno-savvy one, and therefore the design and construction of the Sporkworld site, the Microblog and News from Erewhon were all carried out by her. Her work in this area is always individualistic rather than textbook. Still, at the same time, it exhibits both a powerful emphasis on user-friendly functionality and a considerable visual flair. She may have presented herself as the mercurial, comical, slightly wacky half of the partnership, but there was always a sharpness, toughness, self-discipline and a determination to succeed just under the surface.

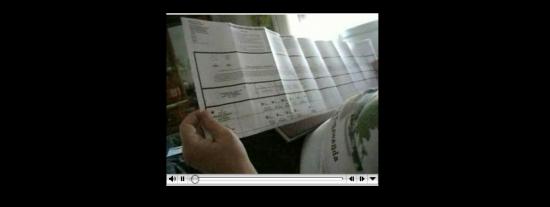

On the other hand, Millie’s work undoubtedly has an impulsive element, and in the collaborations, this makes a compelling contrast with Martha’s more studied approach. “God Fuck!” is one example; another is “Voting”, a video made in November 2008 showing Millie’s difficulties, as a disabled individual, in trying to deal with her postal vote form. Her ballot paper combines a list of presidential, senatorial, and Congress options and several constitutional issues specific to North Tonawanda, the town in which Millie and Martha live. As a result, it’s a huge sheet about the size of a tablecloth, with as many creases as an Ordnance Survey map, and just as difficult to flatten or re-fold. Step by step, Martha takes Millie through the different options on offer, with Millie keeping up a gunfire of questions and acerbic commentary, interspersed by short periods of silence during which she gasps for breath. Both Martha and Millie are represented on-screen mainly by their hands – first Martha’s, as she manipulates the ballot paper and fills it out in accordance with Millie’s instructions; then Millie’s, towards the end of the process, as she signs the outside of the envelope to authorise her vote. Apart from this, they are represented by their voices: Martha’s calm and methodical, Millie’s staccato and satirical, but both become increasingly impatient as the difficulties of dealing with the ballot paper become increasingly apparent. Ultimately, Martha can’t get it folded to fit the official envelope. Then Millie has to rehearse her signature because her hands are so afflicted with arthritis that she struggles to hold a pen. Then the envelope is difficult to sign because it’s so fat and unshapely with the ballot paper inside it. Then it turns out that the envelope will have to be taken to the Post Office and weighed because it isn’t pre-franked or freepost; at which point –

MILLIE: Okay, so we’re gonna have to pay postage on top of this… and it has to be weighed because it’s so fucking heavy!

(Slightly shocked pause.)

MARTHA (elaborately self-restrained): Did you mean to put the word “effing” in?

MILLIE (immediately): I did! I absolutely did! I mean, it’s a matter of free speech. The Supreme Court would have upheld my right to say fucking on my own blog. There have been efforts to make it impossible to say that.

MARTHA (holding up the envelope, with a noticeable change of subject): Okay, I think we actually have it done.

It’s a wonderful piece of film-making. Whether or not you agree with what Millie seems to be hinting, that there is a deliberate attempt on the part of the establishment in the USA to discourage people at the margins of society from taking part in the democratic process, or whether you prefer the view that bureaucrats have no conception of the difficulties faced by the people on the receiving end of their bureaucracy; the point that the postal ballot, which is supposed to make it easier for disabled people to vote, actually makes it almost intolerably difficult, has been well and truly established by the end. But the real strength of the video lies partly in the interplay between the two main characters and partly in the underlying theme of Millie’s disability and how they handle it. As with Millie’s work, her illness is central to the meaning of the piece, yet it isn’t about the experience of being ill. It’s about how illness changes your relationship with the rest of society – one of her most powerful themes. But it’s also about coping with that situation through the help of others – in this case, Martha – and through a supreme effort of will.

Much of the poignancy of the piece lies in the soundtrack: Millie gasping for breath on the one hand and Millie rattling off her machine-gun-like commentary on the other. You can’t ignore how ill she is and doesn’t ignore it herself, but she won’t let it shut her up. The video is a gradual crescendo of comedic impatience, culminating in the obscenities at the end. Her outspokenness is a refusal to be silenced by society and the universe, which has trapped her spirit inside such an inappropriate body. She overcomes her difficulties by externalising them. She makes them the subject of her art, and by doing so, she finds her voice.

No doubt Millie would have become an artist of some description, whatever body, circumstances and state of health she was born into. She was sufficiently remarkable for that. But without her ill health, the work she left behind would have been very different: less spiky, poignant, funny and perhaps less urgent. Her output is not defined or limited by her health, but her health gave her her most important themes and powerful moments. The supreme irony of her art is that, like the knotty grain of a piece of burr elm, the things that made her imperfect were the same things that made her unique and beautiful.

©Edward Picot, December 2009