Emilie Giles interviews artist Mary Flanagan about Tiltfactor’s latest social game, Pox: Save the People. http://www.tiltfactor.org/pox

Emilie Giles: Can you give an introduction to POX: Save the People, and why Tiltfactor was keen to produce a game which explored issues around immunisation?

Mary Flanagan: POX: Save the People is a 1-4 player board game that takes on the public health issue of disease spread. We developed the game after wishing to pursue some public health issues and having prototypes games on cholera and HIV awareness at the lab. A local, and quite open, public health group called Mascoma Valley Health Initiative up in the New Hampshire region of the US approached us with the problem of the lack of immunization. At first, a game about getting people immunized seemed like one of the most “un-fun” concepts imaginable. But that sinking feeling of impossibility almost always leads to good ideas later, so I agreed to take the project on. We decided we could make something fun from the topic, and ruled out nothing, from crazed needles to taking the point of view of the disease whose main purpose in life is to spread around.

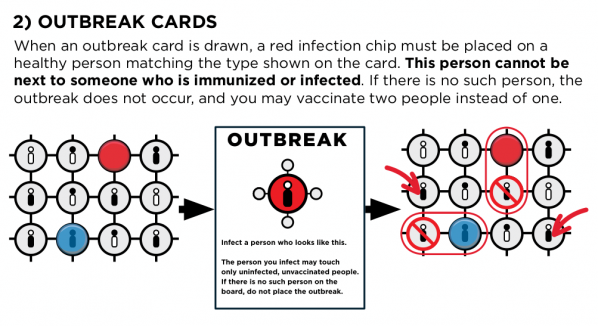

In our final version of the game, the board is modeled after a community, with the spaces representing people. The game begins with two people being infected with an unnamed disease, and the illness speads. Players try to contain the disease and save lives. There are vulnerable people among the population noted in yellow, and these people — pregnant women, young babies, and those in frail health — cannot be vaccinated.

EG: Schools have the option to download a sample lesson plan which incorporates the game into a science class. Please explain how you feel play can encourage learning in an educational environment.

MF: Play is one of the best ways to learn something — certainly tried and true classrooms such as Montessori method schools use play as a part of the curriculum. In the best scenario, play provides experiment space, where failure is ok. In games related to pedagogy, players can test the rules of the system at hand. POX players, for example, can try to cure all of the people on the board to test if this is a good strategy. They can test out best ways to avoid the spread of a disease. Ultimately, they get to make the meaningful choices from within the game rules. Playing POX while learning about real world diseases makes the phenomena more concrete, and gives the learner agency to think about what he or she might do to solve the problem.

The lesson plan for schools was edited by both trained teachers in US middle schools as well as doctors at Dartmouth’s medical school. Truly, then, the game is produced by a community. We could not have created the game to this level of quality without our partners, friends, and supporters.

EG: In most games, a competitive element is introduced to result in a ‘winner’ and ‘loser’. POX deliberately avoids this convention, encouraging players to work together in order to stop the virus. Why was the game designed for this mode of play?

MF: One of the ethos of Tiltfactor games is cooperative play. We like to make games in which players can use collaborative strategy. We define collaborative strategy games as those in which:

1. Games (or in some situations, components of games) where if one player reaches the lose state, everyone playing also loses;

2. The extent to which players win is positively correlated to the success of other players.

Often the most interesting games do not fit comfortably into stereotypical models of play. And because we make games about less traditional topics — public health, layoffs, GMO crops, and other political and social challenges –it is important that the game model itself reflect that. In educational scenarios or in community development, games mirror more closely the ways in which people work together to solve problems. So, the reason that POX is a cooperative game are deeply set in the lab ethos towards problem solving — we can only solve problems together.

EG: You are working on a digital version of the game for the iPad. What was your rational for approaching the topic through both a digital and physical platform and do you think these result in a different type of engagement?

MF: Yes — we’re also creating an iPad version and have an online version to launch as well. It is fascinating to make multiplatform games like this– we are a small lab so we’re doing most everything ourselves, including packaging, promotion, and research.

The differences between the platforms for the game are so dramatic, we’ve decided to conduct a study with the same game and different platforms, because watching people play the same game, the same rules, on a different platform clearly results in an different play experience. It is clear to me that very different things are going on, and I want to back up claims with data. For example, players play much faster if the game is computer based via an online game or the iPad. Players seem to like pressing buttons fast. In the board game, for example, observation shows us that players pick up pieces and discuss the moves with the other players, considering this option and that. The game piece actually becomes a kind of thinking object, I don’t know for sure, but it is very different. The speed up in time with a computer-based game appears to cut down conversation and meaningful dialogue that we’ve recorded in our last study on the board game. So, this is something that as games makers we’d really like to understand better, and share with others.

As an artist, I’m known to make media art and works that engage with play and game culture. In the laboratory context, I love developing and researching games with my team. I have amazing people to work with: Sukdith Punjasthitkul is my project manager who has a background in underground Asian culture, public health, and tennis; Zara Downs is a graphic designer and rural hipster who loves biology; Max Seidman is my accomplished undergraduate engineering student who has racked up several games in his time at the lab, and he loves wearing vests. Matt Cloyd is working with me, a recent graduate who is involved in sustainability issues in communities. Erika Murillo is a new student team member obsessed with social issues and animation. The list goes on. Part of the mission of what we do is to help the next generation who care about social issues have the tools to push what we do now, further.

EG: Your point about how you’ve found players to engage more in dialogue when involved in a board game is very interesting. Non digital games such as board games and pervasive urban games have become more popular over the past few years; do you think players are desiring a more socially interactive experience?

MF: Board games are enjoying a renaissance, it is true. First, because I think people really like playing together in a physical space. Perhaps the new technologies — Wii and Kinect — remind people of that. Perhaps they played recently at a family gathering and remembered how much fun they are. It is impossible to say. Second, there are some really well-designed games out there right now, and available in many countries (in part, due to online purchase power), that are certainly worth playing. People do really like playing with each other in physical space, and they still enjoy watching sports in person. Technology can help facilitate this as with mobile games and pervasive games, but it is not a requirement for a good game. I think different kinds of conversations may happen over board games as compared to digital games, but this is something that needs some data behind it. So, we’ll be doing a study on these nuances in my lab very soon.

EG: Looking at Huizinga’s idea of ‘the magic circle’, there is a clear boundary between play and non-play. What were the challenges in designing a game which straddles this boundary, on one hand trying to entice participants through play and interaction, and on the other attempting to create real life social change?

MF: Emilie, this is the riding question for all of game design engaged with social issues, and behind all of the debates on how gamification can incite real behavioural and social change. You’ve hit the nail on the head! There are many forms of play, some which stay within the game in a nice neat package, like our board game, and some that bleed over into real life, such as ARGs. But one should not be fooled into thinking that this means that the former is useless for education and social change, and the latter is obviously better at it. We are about to release our pilot study on the learning in the game, and the results are surprising, showing that learning transfers out of the game as players can apply concepts in the game to new topics. We’re careful researchers. As artists, and as people critical of flippant comments about games and change, we don’t take research lightly. We don’t, for example, cite major gains on attitudinal change and make assumptions on long term behavioural change from a 40-minute game play session. That would be bad science. So we scale our questions accordingly, and in fact, are still surprised and pleased by the effect the game has. I’ll update you on the specifics when the paper is published this autumn!

The deeper issues on the limits of how games can incentivise real behavioural and social change can get rather dark. How Pavlovian do we want to be in influencing people? Even those in social change arenas have to pause and think. Education and influence for good is what we strive for. Designers and companies can only go so far before we have something much more sinister at hand. This is why our team’s work on the Values at Play project (http://www.valuesatplay.org) remains relevant.