In recent times we have often heard that we’re facing the end of the world as we know it because of factors such as potential nuclear wars, self-sufficient machines, international political crises, and global environmental disaster. However, people in every single age have believed they were heading towards the end of the world. The feeling of being trapped at the end of a road leading nowhere is crucial to understanding why we have needed to apply definitions such as “post-truth” and “alternative facts” to centuries-old rhetorical strategies – creating new terms for the last age of humankind as we know it.

Whilst it may be true that propaganda has been strategically important in shaping opinions since King Darius, the nature of media – from cinematic newsreels created by 1910s national bureaus to today’s social media landscape – plays a crucial role in shaping how strategic messages are created and disseminated. Although we have shifted from the broadcast model of the 20th Century to a mode of prosumption, we are still dealing with the same questions: what effective power does language have? When does a message become propaganda? To what degree can individuals be defined as passive (or active) agents when they share officially approved information? Given these questions, it is no surprise that a number of contemporary artists working with the internet and digital cultures are responding to a perceived crisis of “truthiness” with strategies deriving from the 1910s activity of the Dadaists, a cultural elite who worked in Europe and the U.S. in war times.

Since the 1980s, early artists working with the internet claimed a connection between online art and Dada. It is now important to consider the reasons why, more than two decades later, new generations are still playing in the same field discovered by the Dadaists. The first Dada group was founded in 1915 in Zurich, one of the safest places in Europe, by artists and poets who could afford the journey and the stay. In such a city, anything could be said and written without caring too much about the actual consequences. Broadly speaking, this perceived freedom of expression is analogous to the promises of today’s social media, where everyone purportedly has the same right to share opinions and get involved in discussions as everyone else, without feeling obliged to be politically correct. A sense of detachment is among the features shared by the original Dadaists and contemporary artists with an interest in political questions. Often working in isolated environments, today’s artists use detachment as a strategy by distancing themselves from what’s happening behind the borders and commenting on the daily news, attending to how ‘facts’ have been narrated rather the ‘facts’ themselves.

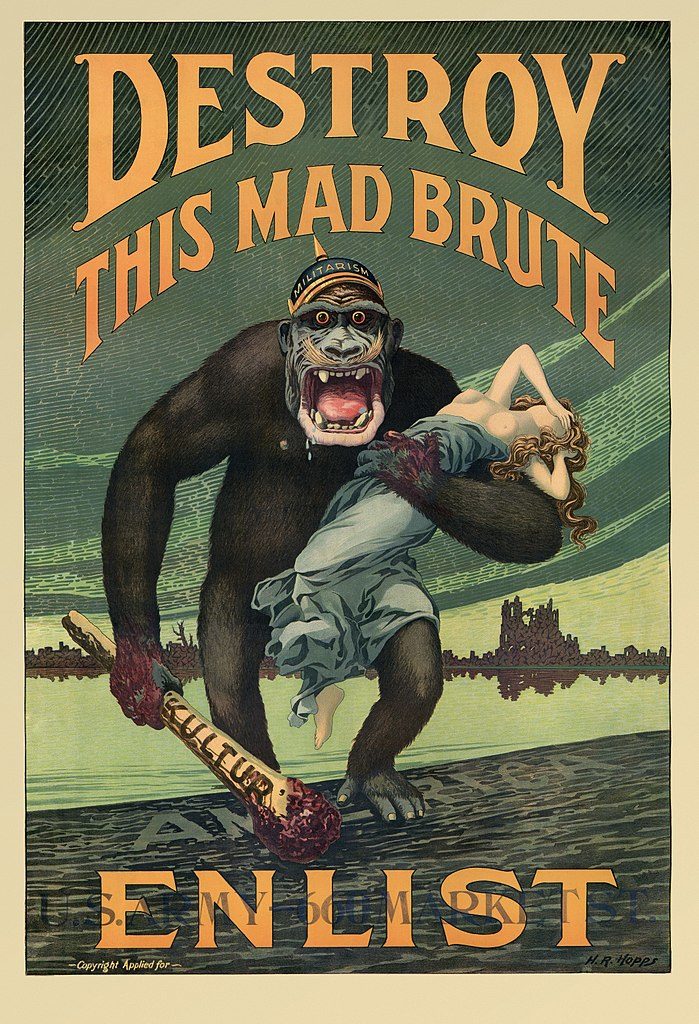

Another important feature shared both by contemporary artists and the Dadaists is a focus on the ‘flatness’ of communication, which was adopted in strategies of advertising, propaganda and manifesti. This flatness arises since every sentence is an exclamation and the reader’s attention is diverted by unexpected changes and incessant slogans, making the message a discourse without hierarchies. This mechanism makes every part important and urgent, such that, no one part is actually necessary for the economy of the message.

A century ago, a political or artistic group couldn’t be defined as such if it didn’t publish at least a founding manifestoin a newspaper. To write a manifesto meant to impose a vision of the world, to claim the priority of some values in respect to other interpretations. Nowadays people rarely make manifesti, but a spectacular exception is Google’s list of guidelines for Material Design. These aim to spread the word about a “unified system that combines theory, resources, and tools for crafting digital experiences”, a mission recalling those stated by avant-garde and modernist groups to rebuild the world according to a unifying principle embracing all aspects of human beings. Artist Luca Leggero followed the guidelines provided by Google to make #MaterialArt (2017), colourful plastic art sculptures challenging the definitions of artwork and design pieces. Leggero critiques Google’s objective to reconstruct reality under its terms by putting into practice an accelerationist strategy; if everything must become part of the Google-branded world, why not art?

In the 1910s, groups published as many manifesti as possible in order to maintain interest among the public.4 To respond to their dogmatic and flat communication mode, however, Dadaists created countless statements that were not linked with each other whatsoever. For the Zurich group, the goal was to generate noise in the endless stream of commercial and political propaganda; it was a joyful activity that, with its randomness, confirmed the nonsense of all the other official communications. Today, the production of noise, and the disruption of corporate and political communication platforms is the aim of many artists’ practices, but only a few of them are so incisive as Ben Grosser’s. “ScareMail” (2013) is a web browser extension that originated in the midst of the 2013 NSA surveillance scandal. For every new email, it adds an algorithmically generated narrative comprising terms that would likely ring an alarm bell at the NSA.

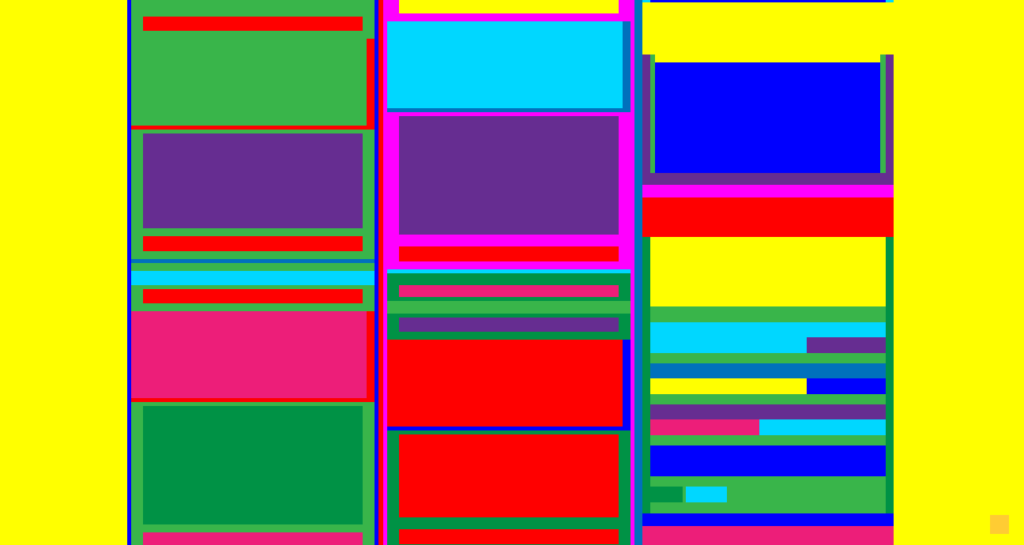

Given the importance of ‘flat’ communicative hierarchies in Dada practice, it’s not surprising how many Dada artists studied the concepts of randomness and entropy as a way of making new realities. There is not just one reality, they seemed to claim, but too many to even imagine; there is not just one imposing point of view, but many – and these may not concur with each other. An exemplary case is a series of collages by Hans Arp arranged according to the Laws of Chance, which didn’t mean they were made without the exercise of any control, but that the artist arranged the pieces automatically, by will. An interest in automatism can be found in many contemporary artists using algorithms as artistic tools, such as Rafaël Rozendaal with Abstract Browsing (2014), a Chrome extension that turns any website into a colourful composition. HTML is a language and as such, it can be read by the browser in many ways, not only the one used by developers and designers. Rozendaal’s work shows the random potential innate in anything, while suggesting there are alternative ways to consume given contents.

“Abstract Browsing” (2014), Rafaël Rozendaal

The production of noise seems to have been the most disruptive response to nationalist propaganda and corporate advertising produced by the original Dada groups. Most of these artists challenged the dogmatic, exclamatory tone used in the official language of war bulletins and newspaper adverts. Taking advantage of this tone and using it in chance-driven messages allowed them to reveal the absurdity of the dogmatic nature of propaganda and advertising.

Many contemporary artists are more or less consciously keeping alive these practices and producing their own kinds of noise in the face of fake news and alternative facts. Nowadays, not only do governments and advertising companies subtly practice dogmatic and exclamatory strategies, but it is even taken for granted they can and indeed do put into practice such disruptive ways to spread messages. When propaganda exploits guerilla strategies, and is generated in the same way art projects disrupt media environments, how should artists respond? This is one of the most challenging issues some artists want to address and the next few years will be a rich (and noisy) testing ground for many of them.