In 2011, Rachel Clarke and Claudia Hart co-curated The Real-Fake, a post-media exhibition engaging art made in synthetic spaces, shot with virtual cameras, and emerging from “other spaces” like code-space and biotech. In 2016, Clarke and Hart together with Pat Reynolds updated the show at the Bronx Artspace, with over 50 artists working in immersion, virtuality, game space, digital photography, and so on. Two months after the launch of real-fake.org, and in the first month of the US Trump presidency, which could be argued as the first presidential campaign simulated in Baudrillard’s terms, Claudia Hart and I talk about what “real-fakeness” is, how it arrived as an art notion, and how it has informed two exhibitions.

PL: What, in your mind does the show represent as an expression of contemporary culture?

CH: The Real-Fake remake opened on November 19, slightly after the election. I was actually in the air when Trump won, landing in Bucharest, several hours later. The culture there is still overshadowed by the history of the totalitarian regime of Nicolae Ceaușescu. The contemporary art museum actually sits in a corner of his Palace of the People, which was built in the style of WWII Italo-fascist Neoclassicism. The whole experience was ominous and frightening in relation to the autocratic, punitive Trump. I began obsessively tracking “fake news”, both because of its relationship to the kind of propaganda used by the Trump/Bannon team to hijack the presidency, but also because of the hacking of the democratic party and collusion of the Republicans with the government of Vladimir Putin.

In both the 2011 and the 2016 versions of the Real-Fake exhibition, we tried to deconstruct, for simplicity’s sake, what I’m now calling “post-photography”, or what Steven Shaviro termed as the “Post-Cinematic.” This relates to digital simulations of the real made with current technologies of representation and post-mechanical reproduction. Post Photography can be defined by what it is NOT in relation to everything documentary and verité about photography. It suggests a radical paradigm shift with significant cultural ramifications. Post Photography does not purport to “slice” from life, but rather is a parallel construction of it, numerically modeled with the same techniques used by scientists, and also by the game and Hollywood special effects industries. The artists working with it all use specialized compositing and 3D animation software. But instead of capturing the real in an indexical fashion, Post Photography artists use measured calculations to simulate reality.

Our deconstruction of the post-photographic real-fake was made in relation to cultural myths about the truth, through viewing the work of 50 artists. They are all part of a larger community acutely aware of the implications of using a computer model of the real as opposed to traditional capture technology. The issues implied by this choice have obviously been made manifest at our own historical juncture, when the culture of science and climate-change deniers rule America. The manufacturing of fake truth in the form of misinformation and ubiquitous infotainment are now profoundly epic.

I’m currently reading Gabriella Coleman’s Hacker, Hoaxer Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous (Verso, 2014) a history of hacker culture related to both the esthetics of “Real-Fakeness” and also the actual milieu that it emerged from. I’m inspired at the moment by that book, and the brilliant essay “Tactical Virality” by Hannah Barton (Real Life, February 14, 2017) because they’ve helped me to articulate what I now feel is the relationship of The Real-Fake to our current cultural and political quagmire. What excited me about the Barton article is that she finds language to talk about the fake news, meaning in larger terms, the fake media strategy so successfully implemented by the Trump/Bannon team. Both of these men are fake-media production experts, and individually built lucrative empires with their expertise. Fake news is a product, and one can trace its lineage from the first alt-right radio flamers, through Fox, Breitbart and now, embodied in the personage of Steve Bannon, straight into the oval office. Fake news is a semiotic morph, a kind of hybrid of advertising and spectacular entertainment covered by a gloss surface of “news” or facts, that can be output in a range of forms from talking-head news commentators, to pseudo down-and-dirty cinema verité documentary. It is a knowing contemporary version of propaganda, and in fact, as reported by Joshua Green in Bloomberg Politics in 2015 even, in a chilling profile of Steve Bannon (https://www.bloomberg.com/politics/graphics/2015-steve-bannon/), Andrew Breitbart himself called Bannon out as “the Leni Riefenstahl of the Tea Party movement.”

So, with Bannon/Trump, we have entered into a paradoxical social-media semiotic in which that which most strongly resembles what Stephen Colbert dubbed as “truthiness” must be suspected as being the biggest lie.

PL: And to focus this back to art, perhaps what we might say is that instead of Picasso’s axiom of artists telling lies to reveal the truth, to make a fake “real” is to go through the machinations of media manipulation that Robert Reich talked about, like pulling the media in and driving conversation until it’s “almost real.” Maybe that’s the quality of “Real-Fakeness,” or even “Fake-Realness” (to do a structural inversion). And with “Simulationists” as we are, and postinternet artists, perhaps veracity and verisimilitude aren’t the point anymore. Maybe it’s just what’s in the boxes and “teh netz”.

CH: Exactly. All of these players are deploying the representational tactic of structural inversion, one of the techniques used to grab audience attention and leverage in the Internet media economy. Bannon’s professional canniness in rerouting the attention economy into fake news, was that flaming mis/information could be sold as a very lucrative attention-economy product. Likewise Trump made a fortune within this economy. Both are experts in the tactics required to make a thing go viral, in hacking the media/entertainment system for maximum clicks. Their approach obviously works. And you can see this in some of the work in the show.

PL: Jean Baudrillard famously wrote about the simulated image in media culture that finally is believed to supplant the Real, i.e. “The Desert of the Real”. Do you think this is where we are with the notion of “Real-Fakeness”?

CH: Tactically viral fake news resembles the Situationist practice of détournement – what Barton called “virtuosic prank-like acts designed to turn expressions of the capitalist system against itself.” This impulse lurks behind most of the hacker culture that Gabriella Coleman documented. Even with the most sincere and political of intentions, hacker culture denizens share a position of deep Duchampian irony. Hackers are all, more or less, in it for the lulz – a kind of dark, aestheticized Nietzschean “lol” which injects noise as agents of chaos, being much different than tactical artists who fight the system. This darkness characterizes a time in which artists and cultural commentators routinely meditate on how one might psychically navigate the end of civilization, for example Roy Scranton’s brilliant Learning to Die in the Anthropocene,” (CIty Light Books, 2015) and the Morehshin Allahyari /Daniel Rourke 3D Additivism project that I feel so profoundly connected to.

And in case of point, Morehshin is a “real-fake” artist.

PL: I have a lot of support for it, too. I think that projects like 3D Additivism are really significant on so many levels, as things like tactical aesthetics, media art, and criticism lend themselves to collective projects. I mean, most likely more than half of my work and collaborations are collective; RTMark, Terminal Time, Yes Men, Second Front, Pocha Nostra, Morehshin’s My Day Your Night project with Eden Unulata… It just seems that these areas of work build community, and that’s something I’ve always believed in. 3D Additivism really addresses critical aspects of the explosive nature of digital making, its pitfalls, and how to deal with these Anthropocene issues through the problematics of the very technology that it critiques. That’s the issue with ”real-fakeness”; it lives in this tactical center where it’s by necessity earnest, yet ersatz at the same time, kind of like Dubai.

CH: Exactly. What this specifically means in terms of the work we exhibited was that it routinely coopts strategies of representation often found in advertising slogans, media products and propaganda, to serve an alternative agenda – sometimes to propose a ludic reality and sometimes to propose a more utopian one as opposed to the dystopic one of Fake News. This is the premise of REAL FAKE art, and is related to the Simulations discourse of Baudrillard.

PL: And then the Real-Fake artist takes the Real, verisimilitude, and détourns it into sets of aesthetic tactics that reframe the nature of the work itself, radically shifting its art historical context.

CH: The approach of the artists in the Real-Fake is the tactic of détournement that the Situationists introduced in the late 1950s and 60s. They were also countering a reactionary Cold-War culture, ironic in terms of Trump’s oligarchical relationship to Moscow. The idea of Situationist détournement, which is so connected to the ideologies and tactics of hacker culture, is to irritate conservative, Capitalist hegemonic power. I mean YOU were part of The Yes Men, and détournement strategy was very influential to that group. The tactic of détournement tweaks entrenched bureaucratic power structures … there is nothing intrinsically political about it in itself. It’s a kind of publicity stunt, a way of grabbing media attention and thumbing one’s nose at the powers that be. It is the posture of the trickster. To quote Barton, détournement “can be reduced to an ideologically flexible logic of inversion and appropriation.”

PL: Right. And this relative, flexible set of significations inevitably creates paradoxes and contradictions that hegemony/Deep Power/the Superstructure can’t process.

CH: In real-fake simulations, the détournement is of representations that are “impossible” – that appear both real and unreal at the same time, being inherently uncanny in the Freudian and Mori-an sense – both dead and alive simultaneously, it is a paradoxical state in which opposites collide. What happened in the prelude to the 2016 US presidential election then is that is that pro-Trump fake news, advised by Bannon, tactically assumed that position by playing the “outsider’ card, and pantomiming resistance. However, we all know they simultaneously bequeathed the benefits of it onto a gang of billionaire plutocrats – the richest oligarchs and corporate leaders in the world. They seized the power of the news media, itself already perceived by the masses as truthy “information,” which this oligarch gang, for the most part, owned (Fox News for example, is owned by the rightist Rupert Murdoch). It was done to further consolidate power and seize the government. They then staged a “return of the repressed” (or the emergence of a new ‘oppressed’), for the Trump “base” – a fringe hate-mongering hyper-aggressive “wrestling” culture to borrow from a related ethos. This demographic was duped into believing that they were speaking their truth to entrenched liberal governmental power, although they were actually being used and manipulated as mouthpieces of a feudal corporate bloc who by then had completely co-opted the federal government. Videos of this radical fringe were then recorded to flame hate and racism, opening Pandora’s Box for white Middle Americans to enact similar cultural forbiddens that had been oppressed by the corporate institutional repression of “Political Correctness”: sexism, racism and religious xenophobias. Hate was linked to the First Amendment, and it unified Trump supporters, and Fake News coopted Yes Men tactics to oppose the Left, the strategy of détournement. But as was recently said, détournement is not ideologically married to the Left, and yes, this is where we are at right now. The question at this time is if we can re-take these strategies to take some power back.

PL: On the other hand, Western society is confronted with the notion of Fake News, “Alternative Facts”, and the like. Again, I will draw on Picasso saying that artists tell lies to reveal the truth. Do you think this is the difference between “Real-fakeness” and “Alternative Facts”, which are propositions that willfully try to obscure reality for their own ends?

CH: In her article, Gabriella Barton analyzes how fake news manages to go viral. Our current media ecosystem, the one in which fake news played out during the election, is a fluid information economy in which stories bring together groups on the basis of group identity around their positions. These need not have any relation to fact…they are actually reflections/inversions of ideologies, and can be thought of as contemporary mythologies in the sense of Roland Barthes. That’s structurally how fake-news is used to manipulate the populace, and how the populace makes certain fakeries go viral. In the culture of social media, where clicks are king, people create their identities by associating themselves with “links” to such media mythologies, pseudo info bytes that resemble information and news, in order to associate themselves with whatever community they identify with.

Barthes’ 1957 Mythologies examined our tendency to create versions of myths from the ubiquitous media that surrounds us. Trump/Bannon came to the same conclusions as Barthes, though doubtfully by reading him, surely as a result of their first-hand experience as media-moguls. They’ve pushed Barthes’ insight to its ultimate conclusions, creating fictional mythologies that simulate information as news in order to build their community. This community is ultimately nihilistic, and is unified primarily by their fear and an anxiety about the loss of their white dominance in an emergent, global post-industrial culture. The Trump/Bannon team built their base, giving them material to construct individual identities by viralizing propaganda and simulated information.

What I’d like to propose alternatively is that now as media artists specifically, we can similarly build mythologies not of authoritarian dominance but of resistance. For example: I love Catwoman! I find her to be an emotional paradigm symbolizing resistance. I wish I had invented her myself. I wish I was her! I’d like to propose to contemporary media artists that they perform alternative mythological identities of resistance created in the space of public media, as a means of creating community. I believe in community and believe it’s only through community that we can drive a wedge into autocracy. I think we can use media to mythologize emotional truths of resistance, Barthean mythologies that are more communal and constructive, to inspire activism and resistance.

Perhaps Trump will implode eventually. Since he’s seized power, he’s made many references to fake news in tweets. To quote Barton again:

This is tactical virality now reified as strategy by a sitting administration defending the executive branch’s power. In his Twitter performances, incoherence has become a coherent approach, seeking to pre-emptively absolve Trump of accountability.

So, in response, I’d like to believe that, if we follow Barthes’ thought to its logical extreme, Trump is now inverting his own inversion, a reification and draining of his own mythological power. Then, if the Goddess is on our side – he folds in upon himself!

PL: Do you think what we are doing with “Real-Fakeness”, Simulationism, and the like is sampling reality as a medium, a toolkit?

CH: Yes! I hope! I’m a simulations artist and real-fakeness is my tool. I hope that with it we can both inspire resistance and build an alternative world. Aside from lending my body to street manifestations and calling my congress-people, it’s what I can do now.

PL: How does all of this express itself in your work, and how do you feel you speak to the simulated spirit of the times?

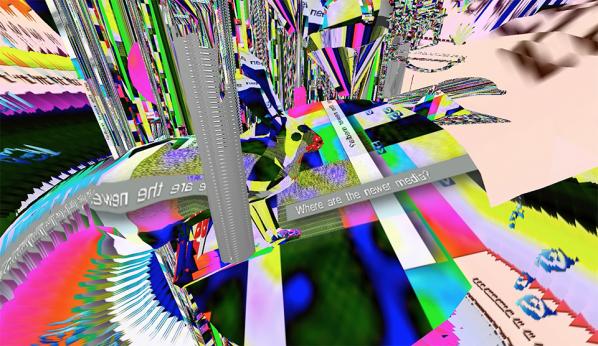

CH: At the moment I’m developing several projects, post-Trump. The one that is most relevant to this converstion is The Beauty of the Baud, that I’m working on with LaTurbo Avedon – the virtual artist living only in the spaces of social media – meaning Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Tumblr. She also is the curator of Panther Modern, a museum that also only exists virtually, exhibiting the post-photographic documentation of the exhibits that happen there. LaTurbo invites artists who work with VR software to create shows, offering each a room in her museum. She then displays simulated documentation of them at panthermodern.org.

Since 2007, I’ve developed a curriculum at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, called X3D, a group of 8 classes that work with simulations technologies in the context of post-photography and experimental media. The Beauty of the Baud is a project led by LaTurbo Avedon and I in collaboration with one of those classes, my Experimental 3D 2017 class.

LaTurbo built “Room 17,” a special Panther Modern exhibition hall, to show works created by my Intro X3D class, a group of 14 Art Institute students using simulations software for the first time. Acting as both guest critic and curator of the first Panther Modern group exhibition, she is choosing 14 works, one from each student, out of a selection of renderings of solo shows, each produced for Room 14, The Beauty of the Baud room, inside Panther Modern. The whole thing is conceived in relationship to the 30th birthday of The Hacker’s Manifesto. We are also reading the Coleman book, and discussing it as we go.

The Beauty of the Baud will be shown online, in Panther Modern in May, 2017. Then a portfolio of archival prints of the computer-model images will be offered for sale, all proceeds from it donated to either international immigrant assistance, inner city education or climate research – my students are debating which among themselves even now. Both an exhibit in “real” as well as “virtual” life, The Beauty of the Baud will include the student portfolio, plus conceptually related works by LaTurbo Avedon and I, and will geographically be situated in Bucharest – the city that inspired me to go down this route in the first place- with the Romanian curator Roxana Gamart in her Möbius gallery. She is in conversation with several institutions there as well, and we are working on something for that context.

I’m very psyched about the Beauty of the Baud. It’s helping me to process it all. As an artist, at this moment in time, I’m afraid it’s the best I can do.