In “How Readers Will Discover Books In Future“, science fiction author Charles Stross envisions a future in which weaponized eBooks demand your attention by copying themselves onto your mobile devices, wiping out the competition, and locking up the user interface until you’ve read them.

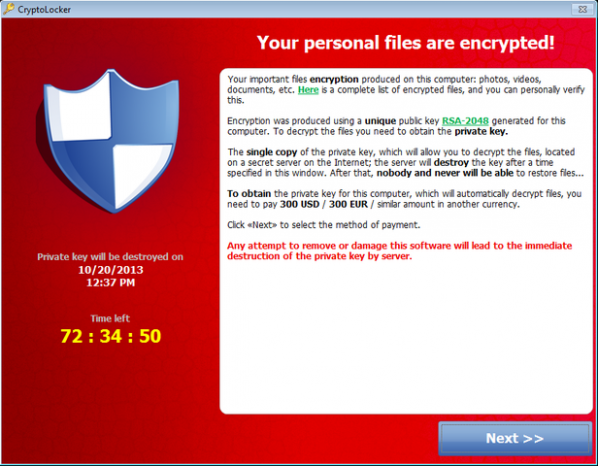

This is only just science fiction. Even the earliest viruses often displayed messages and malware that denies access to your data until you pay to decrypt it already exist. ePub ebooks can execute arbitrary JavaScript, and PDF documents can execute arbitrary shell scripts. Compromised PDFs have been found in the wild. Stross’s weaponized ebooks are not more than one step ahead of this.

Why would eBooks want to act like that? To find readers. In the attention economy, the time required to read a book is a scarce resource. Most authors write because they want to be read and to find an audience. Stross’s proposal is just an extreme way of achieving this. In Stross’s scenario, authors are like the criminal gangs that use botnet malware to get your computer to pursue their ends rather than your own, use adware to coerce you into performing actions that you wouldn’t otherwise, or use phishing attacks to get scarce resources such as passwords or money from users.

As so much new art is made that even omnivorous promotional blogs like Contemporary Art Daily cannot keep up, scarcity of attention becomes a problem for art as well as for literature. And when people do visit shows they spend more time reading the placards than looking at the art. In these circumstances Stross’s strategies make sense for art as well. Particularly for net art and software art.

A net or software artwork that acted like Stross’s vampire eBooks would copy itself onto your system and refuse to unlock it until you have had time to fully experience it or have clicked all the way through it. It could do this in web browsers or virtual worlds as a scripting attack, on mobile devices as a malicious app, or on desktop systems as a classical virus.

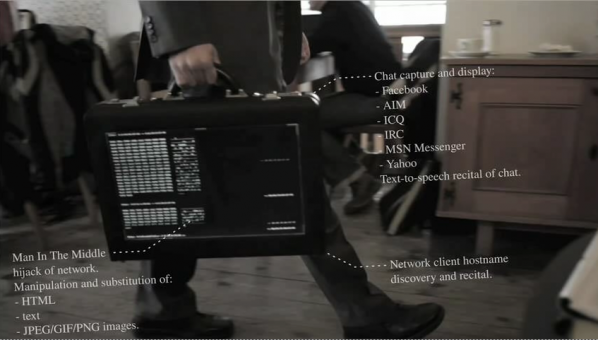

Unique physical art also needs viewers. Malicious software can promote art, taking the place of private view invitation cards. Starting with mere botnet spam that advertises private views, more advanced attacks can refuse to unlock your mobile device until you post a picture of yourself at the show on Facebook (identifying this using machine vision and image classification algorithms), check in to the show on FourSquare, or give it a five star review along with a write-up that indicates that you have actually seen it. In the gallery, compromised Google Glass headsets or mobile phone handsets can make sure the audience know which artwork wants to be looked at by blocking out others or painting large arrows over them pointing in the right direction.

Net art can intrude more subtly into people’s experiences as aesthetic intervention agents. Adware can display art rather than commercials. Add-Art is a benevolent precursor to this. Email viruses and malicious browser extensions can intervene in the aesthetics of other media. They can turn text into Mezangelle, or glitch or otherwise transform images into a given style. In the early 1990s I wrote a PostScript virus that could (theoretically) copy itself onto printers and creatively corrupt vector art, but fortunately I didn’t have access to the Word BASIC manuals I needed to write a virus that would have deleted the word “postmodernism” from any documents it copied itself to.

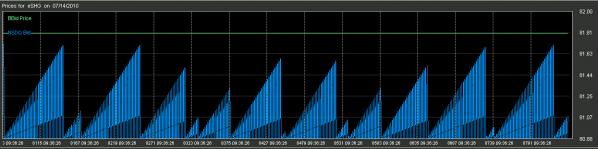

Going further, network attacks themselves can be art. Art malware botnets can use properties of network topography and timing to construct artworks from the net and activity on it. There is a precursor to this in Etoy’s ToyWar (1999), or EDT’s “SWARM” (1998), a distributed denial of service (DDOS) attack presented as an artwork at Ars Electronica. My “sendvalues” (2011) is a network testing tool that could be misused, LOIC-style, to perform DDOS attacks that construct waves, shapes and bitmaps out of synchronized floods of network traffic. This kind of attack would attract and direct attention as art at Internet scale.

None of this would touch the art market directly. But a descendant of Caleb Larsen’s “A Tool To Deceive And Slaughter” (2012) that chooses a purchasor from known art dealers or returns itself to art auction houses then forces them to buy it using the techniques described above rather than offering itself for sale on eBay would be both a direct implementation of Stross’s ideas in the form of a unique physical artwork and something that would exist in direct relation to the artworld.

Using the art market itself rather than the Internet as the network to exploit makes for even more powerful art malware exploits. Aesthetic analytics of the kind practiced by Lev Manovich and already used to guide investment by Mutual Art can be combined with the techniques of stock market High Frequency Trading (HFT) to create new forms by intervening in and manipulating prices directly art sales and auctions. As with HFT, the activity of the software used to do this can create aesthetic forms within market activity itself, like those found by nanex. This can be used to build and destroy artistic reputations, to create aesthetic trends within the market, and to create art movements and canons. Saatchi automated. The aesthetics of this activity can then be sold back into the market as art in itself, creating further patterns.

The techniques suggested here are at the very least illegal and immoral, so it goes without saying that you shouldn’t attempt to implement any of them. But they are useful as unrealized artworks for guiding thought experiments. They are useful for reflecting on the challenges that art in and outside the artworld faces in the age of the attention-starved population of the pervasive Internet and of media and markets increasingly determined by algorithms. And they are a means of at least thinking through an ethic rather than just an aesthetic of market critique in digital art.

The text of this article is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.

Bitcoin is the leading cryptographic digital currency. Created in 2009 by the now possibly unmasked hacker Satoshi Nakamoto, it polarizes opinion. Some people promote it as the technical embodiment of a libertarian attack on the iniquity of “fiat currency” and the power of the state and big banks, an embodiment of a pure market of value untainted by regulation where everything really is worth only what people will pay for it. Others criticise Bitcoin, often savagely, for the same reasons and for what they perceive as its technical and social failings. But Bitcoin is interesting in ways that go beyond the concerns of its most vocal proponents and detractors.

Rather than paper money backed by gold or electronic money held on a bank’s central mainframe, Bitcoin exists as records of transactions in a public record called the blockchain, which is added to and authenticated by computers on the Internet running the Bitcoin software. Transactions in Bitcoin use cryptographic signatures rather than names or emails as the identities of the sender and receiver. Computers on the network that process and validate groups (or “blocks”) of transactions are asserting the existence of particular pieces of data at the time they are validated, a process rewarded by the production of new Bitcoins. To discourage malicious or false validations, each mining computer must perform a computationally and therefore resource expensive task known as a “proof of work”, which can be checked and confirmed by other computers on the network.

All of this means that Bitcoin is a massively distributed system for asserting identity, existence, and truth, for values of those concepts that are outsourced to a community of mathematical proxies. The blockchain is essentially a time-stamped record of information that anyone can add to in order to prove that a particular piece of data existed at a particular time. This has applications beyond finance, with examples of new systems for blogging, contracts, corporations and Internet Domain Name services all being based on the block chain system. In many ways it is the blockchain and these applications of it that is the most exciting part of Bitcoin.

Money, cryptography (the making and breaking of codes) and alternative currencies all have long and often intertwined histories. Renaissance banks used secret codes to secure messages sent between city-states. Alternative savings or currency systems such as Green Shield Stamps, LETS or Air Miles were all popular at different times in the Twentieth Century. The first cryptographic digital currency was Digicash, from 1990. And Bitcoin isn’t the first multimillion dollar electronic currency. Linden Dollars, the virtual currency used in the Second Life online virtual reality environment, were used in USD567,000,000 of economic activity in 2009. Bitcoin solved the problems that prevented previous digital currencies from becoming decentralised, and although newer digital currencies have improved on its design it is Bitcoin that has captured people’s imagination.

Bitcoin has encouraged a debate about what money is, what money is for, and how money should work, indeed its production, use, and successors have embodied that debate. It’s created a sense of possibility and a range of production comparable to the early World Wide Web. And it’s launched parodies such as the Buttcoin site and the meme-based cryptocurrency DogeCoin, and the epithet “Dunning-Krugerands”. Bitcoin’s mining system rewards existing capital, and its transaction costs reward intermediaries in much the same way as existing banks and credit cards. But these are implementation details, and newer cryptocurrencies and national cryptocurrencies address them. Post financial crisis, cryptocurrency with all its possibilities and contradictions is a lightning rod for the social imagination. And this includes art.

Coinfest 2014 in Vancouver featured examples of artists using Bitcoin. Buskers performing at the event could be tipped in Bitcoins, graffitti and mixed-media art being exhibited could be bought with Bitcoins. And in the computer lab at the venue each desktop PC displayed a piece of net art with a Bitcoin theme. This was the show “Computers and Capital”, curated by Erik H Rzepka and Wesley Yuen, also viewable online at http://x-o-x-o-x.com/press/computersandcapital/. It includes art depicting bitcoins, art visualizing wealth in terms of bitcoins, and work that evokes the operation of Bitcoin-like cryptocurrency.

thereisaprobleminaustralia’s “Bitcoin Garden” is an html5 alife pond populated by shoals of rippled and faded Bitcoin logos. It’s reminiscent of 90s Director alife, and might benefit from more of that algorithmicity. But as a post-internet tumblr assemblage it’s irresistibly calming and ironic. Bitcoin’s promise of a financial artificial paradise rendered organic, or hydraulic models of the economy leaking into the network.

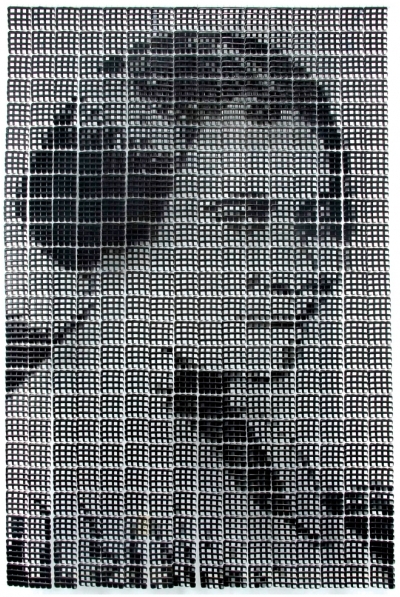

Jon Cates’s “817C01N” is a stark monochrome Floyd–Steinberg dither (an algorithm used on early Macintosh computers to convert colour or greyscale images to binary) animation of a broken iPhone spinning in front of a glitching animation “bitcrushed” from Manuel Fernandez’s “Broken Phone Gradients”. Networked art for a networked currency, it’s a clean, minimalist look afforded by a historical best-of-breed algorithm, an aesthetically and conceptually satisfying digital classicism. And it’s for sale in exchange for Bitcoins.

Ellectra Radikal’s “E.Rad Coin” is a Vasarely-meets-Twister undulating grid of distorted and colour gradient coin shapes. It’s the aesthetic equivalent of Bitcoin’s ethics: the market economic view of society as Conway’s Life with pennies given a post-digital twist.

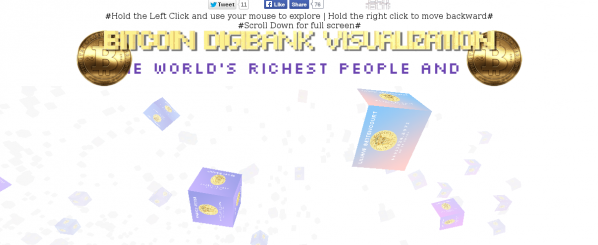

FELT’s “Bitcoin Digibank Visualization” is a financial hyperspace of cubes showing the value of the world’s rich quantified in Bitcoins floating in an endless whiteness. This shows both Bitcoin’s status as a separate economic plane and the ability of existing capital to colonize any resource-based attempt to escape its reach.

Giselle Zatonyl’s “Pop Coinfalls” is a video loop of analogue noise and digital compression glitched falling and stacking coins with a PowerPoint-hell upward graph line animated over them. Blink and you’ll miss it but there are faces on or reflected in the gold of the (Bit)coins as they pile up ever higher. The economy is like that.

Matt Tecson’s “lel buttcoin” is a tumblr blog zoom (an impressive subversion of the vertical scroll bar) of found imagery mostly on the theme of “buttcoins”, a common pejorative for Bitcoins. Coiyes, Bartcoins, and Radeon graphics cards intrude, presumably as they matched the search used to find buttcoin images.

Roger Grandlapin’s “Danaë” is a Flash animation of Bitcoins dripping like honey over animated negative-space text, a porny neoclassical nude of the title and other imagery that I’m not fast enough to make out. Bitcoin’s origin story is related to those of older mythology as a shower of golden rain from Satoshi Nakamoto.

Kutay Cengil’s “Untitled” is a slightly glitched, default material rendered bust of a webcam-foreheaded, PayPal security-badged, melting financial mandarin. This is what Bitcoin is here to save us from, although in a recent interview the CEO of PayPal had more faith in Boitcoin than in NFC.

Systaime’s “Bitcoin Abundance” is a highly compressed YouTube video loop of the dross of 90s PC video clips surrounding a rain of bitcoins. It’s the opposite of Jon Cates’ piece. Visual Vaporwave, the kind of transubstantiation of kitsch that art is meant to do. It’s a formally rich composition, amusing and affecting. But even when I remove my cybercultural and net art historical horses from this race I’m left with the problem that it’s not clear how this aesthetic can fail.

Devon Hatto’s “letsnetworth” is another tumblr, this time of animated GIFs of compositions of that symbol of knowledge (and fashionable digital design), the apple. Digitisation, sustenance and symbolism combine here much as they do in Bitcoin. The net wealth of wealth on the net.

Adam Braffman’s “$$ULOGY” is a YouTube video of Dogecoins (the inflationary, Meme-mascoted rival to Bitcoins), Super Mario Bros gameplay, burning dollars and other found video imagery, with a brief visit from MST3K and a cheesy industrial and soft rock soundtrack interleaved with an echoing apocalyptic economic lecture. Its an impressionistic take on cryptocurrency and the environment in which it exists.

Nicolas Koroloff’s “Green Impact” is an image of a pile of Eurocent coins with a single transparent green bead or BB pellet in the middle. This is a reference to Bitcoin’s of-touted environmental impact due to the electricity expended in mining. The comparison between this energy footprint and that of fiat currency ATMs, chip and pin readers, and other elements of the global banking system probably compares to the relationship depicted here.

Dominik Podsiadly’s “I’ll eat any amount of EU subsidies” is a video performance of the artist smoking, drinking, and doing just that with some large edible 500 Euro notes. The Euro is a political instrument as much as a financial one, and its crisis has been another factor driving interest in alternative currencies, including Bitcoin.

Chimerik’s “Chimerikcoin” is a packed square graph puzzle that rearranges itself to fit as you drag rectangular fragments of an old gold coin around to reveal brief peaks of paper money. It’s the economy as a zero-sum game and Bitcoin as a digital return to the gold standard.

Miyö Van Stenis’s “Bitcoin Dreams” is an interactive html5 animation of settling Bitcoins in front of a cloudy sky and animated curtain. It’s an unusual and effective combination of tightly looped animation and interaction with a vaporwave aesthetic.

ASS Rain’s “Trees” is a collage of translucent green blocks dropped spillikins-style. I found it aesthetically and conceptually opaque, although a very effective composition.

Robert B. Lisek’s “Quantum Enigma” uses a geiger counter to generate an encryption key for communication, ironically realising the promise of quantum crytography. It’s a historically and technically literate project that communicates a strong political stance while remaining technically and aesthetically interesting.

The ability to curate such a show online and present it as part of a wider cultural event marks a moment where the widespread availability of Internet access, Web 2.0 publication platforms, and computer labs at event and community spaces has transformed the possibilities for curating and contextualising digital art. “Computers and Capital” exploits these affordances very effectively. The recurrent themes, of pennies from heaven, ironic digital kitsch, glitchy compression artefacts, and potlatch, feel both appropriate and effective in visually communicating and critiquing the technical and social complexities of cryptocurrency in the age of austerity.

Bitcoin has caught the attention of the public, government, criminals, and artists. It is both an expression of the economic imaginary and a genuinely novel means of networked communication. This makes an unusual subject for art, whether celebratory or critical. Even the most ironic celebrations of Bitcoin in art are depictions of a network protocol, or a deflationary electronic currency. Whether visually and conceptually preparing us for a brave new world of cryptocurrencies or creating the illusory realm in which they will achieve their only lasting victory, Bitcoin art is very different from a Warhol dollar sign, a Hirst diamond skull, or the other symbolic band-aids for the ideological aporia of capital’s hollow victory. It is the art of a heresy rather than a hegemony, of a moment of technological, social and aesthetic possibility.

“Computers and Capital” very successfully captures this moment in art and makes it accessible in ways that thousands of words on the subject cannot. A thought-provoking, illuminating and often fun collection of work of a uniformly high standard that is nonetheless technically and aesthetically diverse can be presented online and off as part of a wider cultural event. “Computers and Capital” shows how network-enabled digital art can function as a bridge between complex and important ideas and the public imagination.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.

Featured image: PAH graphic resources

Over the last few years there has been a keen interest in discussing the notion of public space; demonstrations, camps, collaborative projects, artistic interventions, community projects, social activism are just a few names that exemplify the different forms of engagement that deal with the complexities of it. Despite their different aims and impact most of these actions have given evidence of the need to re-appropriate the public space; through collective and networked practices individuals, groups and organizations ‘challenge the conventional notion of public and the making of space’[1]. Although the liveness and even virality of these events, projects or actions hinder any prediction about its midterm effects or endurance, the fact is that there is an emerging legacy that is already dismantling certain assumed thoughts about ‘the public’.

The retiree Hüseyin Çetinel’s initiative of painting a public stairway with rainbow hues in his neighbourhood in Istanbul has been the last case involving cultural transformation, virality and social activism. After he painted the local stairs to ‘make people smile’ and ‘not as a form of activism’ the municipal cleaning service painted over the stairs in dull grey provoking a chain reaction that mobilized citizens to paint stairways throughout the city. Local communities and social movements appropriated this beautiful participatory action as a form of protest after Çetinel’s stairway became viral in the social media. This example shows the intricacies of the public space and its expanded performativity. As Gus Hosein Executive Director of Privacy International argues ‘there is a confusion as to what is public space is and how it relates to our personal and private space’ in a social context where the emergence of the use of social media and surveillance as well as the appropriations of the space by private corporations and social movements and individuals are constantly questioning its boundaries[2].

From my point of view, some of these actions that play in-between the social, political and artistic might be considered re-enactments of the public space as they aim to reconstruct the term itself by applying alternative procedures and by generating at the same time transductive pedagogies. However, in order to give a comprehensive understanding of the implications of the public space and its controversies it is essential to rethink the notion of the private space. Traditionally, home has been recognized as the physical private space; home is the main representative of the private sphere that encompasses the domestic and intimate. According to Joanne Hollows, ‘the distinction between the public and the private has been a key means of organizing both space and time’[3] and consequently to promote a clear functional division.

This traditional perspective has been questioned and altered due to some current issues and events that are noticeably interconnected with those of the public space; an increasing number of evictions and homeless peoples, housing policies, escraches[4] in front of the houses of politicians, the appearance of ghost neighbourhoods due to real estate speculation, home as an alternative space for performance practice and community development, among others. Thus, home might be conceived as a container of individuals and actions, as a social product or instrument, as topographical placement or as a relational structure. Home entangles interesting layers of analysis that might serve to establish new relational and yet responsive parameters to understand both the private and public space. Some of the following examples that perform between art, activism and affections corroborate the significance of home; as Blunt and Dowling state ‘home is not separated from public, political worlds but it constituted through them: the domestic is created through the extra-domestic and viceversa’[5].

In Barcelona, the city where I live there have been noticeable factors that have stressed the importance of home as a topic of interest. Probably the most significant case is the increasing number of evictions―over 350.000 in the last four years―as many families cannot afford their rent or mortgage after losing their jobs (the unemployment rate is 26.3%). Beyond the personal implications and devastating effects that evictions have on families, they also indicate that home is not anymore our secure space or refuge; on the contrary, if the individual does not respond to the production and consumption requirements is physically displaced to the streets. Consequently, many citizens are trying to find shelter back again in the public space.

If the 70s Richard Sennett announced the decay of the public space by the emergence of an ‘unbalanced personal life and empty public life’[6], the related problems with housing have provoked the reactivation of the public space at many levels. At the same time, there is an increasing culture of the debt that ties together individuals and financial institutions in long-term relationships. As Hardt and Negri explain ‘Being in debt is becoming today the general condition of social life. It is nearly impossible to live without incurring debts—a student loan for school, a mortgage for the house, a loan for the car, another for doctor bills, and so on. The social safety net has passed from a system of welfare to one of debtfare, as loans become the primary’ means to meet social needs’[7].

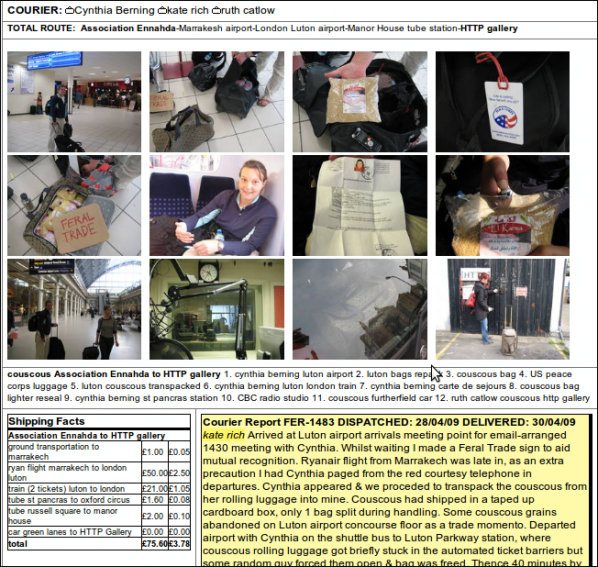

These ideas can be exemplified by the actions of PAH (The Platform of People Affected by Mortgage Debt), an activist group of citizens that stops evictions through demonstrations and guerrilla media actions in the streets and that also helps struggling borrowers to negotiate with banks and promotes social housing[8]. This organized group of citizens has been awarded this year the Citizen Award by the European Union for denouncing abusive clauses in the Spanish mortgage law and battling social exclusion. PAH has received the support of the collective Enmedio that generates actions in the midst of art, social activism and media. For example, their photographic campaign ‘We are not numbers’ consisted in the design of a collection of postcards each one containing a portrait of a person that was affected by the mortgage debt by a local bank entity. The postcards were delivered in front of the bank’s main building for people to write a message. The written postcards were then stuck in the front door main door turning numbers into a collage of human struggle. PAH and Enmedio actions become highly effective thanks to their media impact and their virality in the social media. Invisible individuals isolated in their struggle, find alternatives through an assemblage of support that connects the public and private space and that is also mediated by informative and constitutive tools that the virtual space offers. As Paolo Gerbaudo claims ‘social media have been chiefly responsible for the construction of a choreography of assembly as a process of symbolic construction of public space which facilitates and guides the physical assembling of highly dispersed and individualized constituency’[9].

Processes of speculation, gentrification and eviction can be found in many western cities as well as different kinds of collectives and groups working for human rights advocacy. This is also the case of the Brooklyn based collective Not an Alternative has also carried out different guerrilla actions concerned with the problem of housing and eviction such as their series of workshops and media actions of ‘Occupy Real State’ or ‘Occupy Sandy’.

Many of the actions that these collectives promote might be understood as DIY activism as they are based on the empowerment and the development of skills. In this regard, it is interesting to observe how DIY that traditionally has been related to activities in the domestic space serves as a strategy to protect it and to trigger new forms of protest in the public space while enhancing the creation of an expanded family (or at least a sense of togetherness) through the social media.

Despite these actions, the public space is still home for many individuals. In the UK, different associations are concerned about the impact that the implementation of the bedroom tax might have, especially in London where the number of rough sleepers rises every year with an increase of the 62% since 2010-2011. The scenario is not different in many other European cities where beyond these worrying numbers there is also an increasing number of regulations and policies that difficult the life in the public space. As Suzannah Young stresses, ‘homeless people often need to use public space to survive, but are regularly driven off those spaces to satisfy commercial or even state interests’. Public space is often only open to ‘those who engage in permitted behaviour, frequently associated with consumption’[10]. The increasing number of quasi-public spaces―’spaces that are legally private but are a part of the public domain, such as shopping malls, campuses, sports grounds’ and so forth― questions again the boundaries of the private and public space, especially when ‘some EU cities use the criminal justice system to punish people living on the streets for doing things they do in order to survive, such as sleeping, eating and begging’[11]. All these policies have clear implications in the use of space and it is potential possibilities. The fact that the public space becomes home involves the reconsideration of the uses of the public space and the understanding of it through the eyes of the people that fully inhabit it. The London collective The SockMob run the Unseen Tours, alternative city tours guided by a group of homeless. Their embodied knowledge appears as a key aspect to develop these DIY versions of the city while promoting relationships between the homeless and the tour participants.

Where is home? In which ways access to spaces gives us opportunities and rights as individuals? In which ways all these site-specific initiatives that often have a transnational reach re-construct the notions of private and public space? How these DIY and media actions are generating new forms of visual arts activism? Despite the fact that these queries might need further analysis, I believe that the qualities of space becomes visible and tangible through these interactive and responsive actions with the spaces. Recently, an international group of activists, visual artists and scholars have published a handbook in which their consider these forms of activism militant research. According to them, ‘militant research involves participation by conviction, where researchers play a role in the actions and share the goals, strategies, and experience of their comrades because of their own committed beliefs and not simply because this conduct is an expedient way to get their data. The outcomes of the research are shaped in a way that can serve as a useful tool for the activist group, either to reflect on structure and process, or to assess the success of particular tactics’[12]. Hence, the idea of some hands-on, the acquisition of skills and the performance of theory appear as key aspects to disentangle and analyse the qualities of the space.

From an artistic perspective home has been crucial in many historical periods of dictatorship to construct an underground scene of the arts; in many of these cases, the evidence of artistic practice appears through testimonials and documentation (photographs, fanzines, recordings, etc.). Again different forms of media help to make the clandestine public, crossing the sphere of the private into the public realm. Thus, the importance of documentation enhances different temporalities of reception and impact in the public realm. In this regard, a differed presentation of the artistic works triggers a reconsideration of the attributes of the spaces too. Currently, homes serve as a basic space for artists to present their work; in the case of music, this is a widely known practice in the US that is becoming more and more common in other countries and other art forms. Homes serve as a personal curatorial space for fine arts artists through the open studio festivals too; artists make their private space open for others as a strategy to show their work publicly. At the same time, in some artistic disciplines self-curation through digital portfolios is becoming increasingly used to showcase artworks. One way or another, home remains often the main space for creativity, production and curation through and expanded DIY conception of their profession.

Home becomes even more crucial in a context marked by the arts cuts and the economic crisis. In this regard, there are initiatives that see an opportunity in the relationship between the public and private space not only to exhibit or perform art but also to trigger a counter-performative form of showing works. This is the case of the domestic festivals that try to challenge the concepts of cultural enterprise and institution by proposing home as a legitimate space of the artistic experience. Friends, neighbours and acquaintances offer a room or a space in their house for artists to perform there (examples can be found in different cities such as Santiago de Chile, Madrid, Berlin, Barcelona, etc.). At the same time, the format wishes to transform the spatial and affective relationships that citizens have with the space, by inverting the spatial dichotomy between the public and the private. Hence, the idea goes beyond to a practical solution to have a space to perform as it also aims to give visibility to performing practices that have not been yet legitimized by the public sphere and they are in danger to remain in a sort of clandestinity (as they are not part of the current cultural market). In this regard, there is also a sense of evicted or homeless art that is trying to produce a social context of experience and articulation beyond the immediate effects of the power that governs at many level the public sphere. These kinds of initiatives generate ‘an activity that undermines the exclusion by letting occur, at the very boundary which separates the public from the “secret”’, an articulation which challenges the prevailing framework of representation and legitimation’[14].

The intersection between art, activism and affections help to explain the multiple and complex questions that configure the notion of home. With these examples I just wanted to stress the importance of home in the discourses that address the concepts of public space/public sphere/publicly. Thus homes ‘are thereby metaphorical gateways to geopolitical contestation that may simultaneously signify the nation, the neighbourhood or just one’s streets’[15]. From a transnational perspective, home seems to pose the crucial questions that connect us with what is happening inside, outside and in-between the spaces and gives us a different perspective to analyse current artistic and social practices that engage with our mode of action, production and identity.

I guess this is all from my home.

Curated by Rosa Menkman & Furtherfield.

Opening Event: Saturday 8 June 2013, 2-5pm

with Glitch Performance by Antonio Roberts at 3pm

Open Friday to Sunday 11-5pmContact: info@furtherfield.org

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

IMAGES OF THE OPENING ON FLICKR

READ Glitch as a Symbolic Art Form BY ROB MYERS

WATCH VIDEO OF THE OPENING

“The glitch makes the computer itself suddenly appear unconventionally deep, in contrast to the more banal, predictable surface-level behaviours of ‘normal’ machines and systems. In this way, glitches announce a crazy and dangerous kind of moment(um) instantiated and dictated by the machine itself.” Rosa Menkman [1]

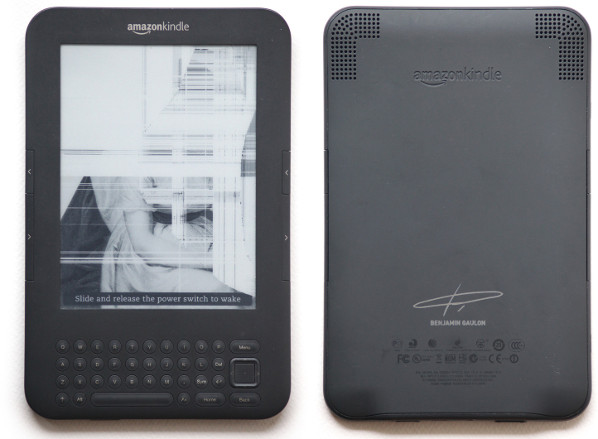

Glitches are commonly understood as malfunctions, bugs or sudden disruptions to the normal running of machine hardware and computer networks. Artists have been tweaking these technologies to deliberately produce glitches that generate new meanings and forms. The high-speed networks of creation and distribution across the Internet have provided the perfect compost to feed this international craze. The exhibition shows various approaches by artists hacking familiar hardware and their devices which include mobile phones, and kindles. They disrupt both the softwares and the digital artefacts produced by these softwares, whether it be in the form of video, sound and woven glitch textiles.

Glitch art subverts the way in which we are supposed to relate to technology, causing playful, imaginative disruptions. It is a low-tech and dirty media approach with a punk attitude. These artists appropriate the medium and forge expressions that go beyond what the mainstream art world expects artists to do, it is unstoppable – it is Glitch Moment/ums.

Copies of Rosa Menkman’s groundbreaking Glitch Art critique The Glitch Moment(um) will be available for purchase during the exhibition.

![numbermunchers from the untitled [screencaptures] series by Melissa Barron](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/melissabarton.jpg)

Empty Spinning Circle become Full (part b) (2012) from the Further Abstract series by Alma Alloro

One Square in colors (2012) from the Further Abstract series by Alma Alloro

untitled [screencaptures] (2010) by Melissa Barron

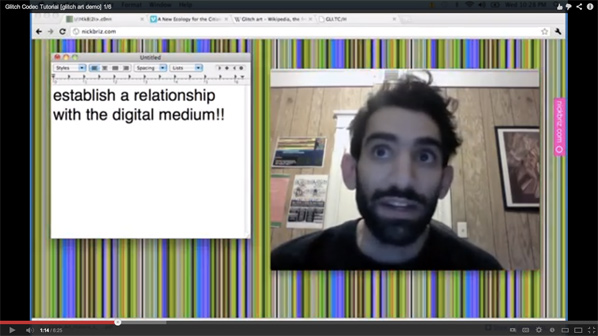

The Glitch Codec Tutorial by Nick Briz

KindleGlitched (2012) by Benjamin Gaulon

Thoreau Glitch Portrait (2011) by José Irion Neto

Copyright Atrophy (2013) by Antonio Roberts

What Revolution? (2011) by Antonio Roberts

Beyond Yes and No (2013) by Ant Scott

Glitch artists and enthusiasts are invited to add their work to GLI.TC/H 0p3nr3p0.net, a Glitch Art repository coded by and developed by Joseph ‘Yølk’ Chiocchi & Nick Briz. The submissions will be showcased during Glitch Moment/ums at Furtherfield Gallery. To include your work in the 0P3NR3P0 component of Glitch Moment/ums submit a link to any visually wwweb based file (html, jpg, gif, youtube, vimeo, etc.) and your piece will automatically be included in the line-up (one work per artist).

This new IRL exhibition has been organised in collaboration with Nick Briz and Joseph ‘Yølk’ Chiocchi.

SUBMIT && SHOW on 0P3NR3P0.NET.

Alma Alloro

Alma Alloro (IL) is an artist, musician and performer from Tel Aviv. She is rooted in the backyard of popular culture using diversified media from drawing, installation, music, and animation to internet; her recent works focus on the correlation between old media and new media.

Melissa Barron

Melissa Barron is an artist living and working in Minneapolis, Minnesota. She studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago where she focused on new media and fiber. In her work she combines these two fields by reinterpreting hacked Apple 2 software through different fiber techniques. Her work has been shown at various international events, including the Notacon hack festival in Cleveland, Ohio, GLI.TC/H in Chicago and ISEA 2011 in Instabul.

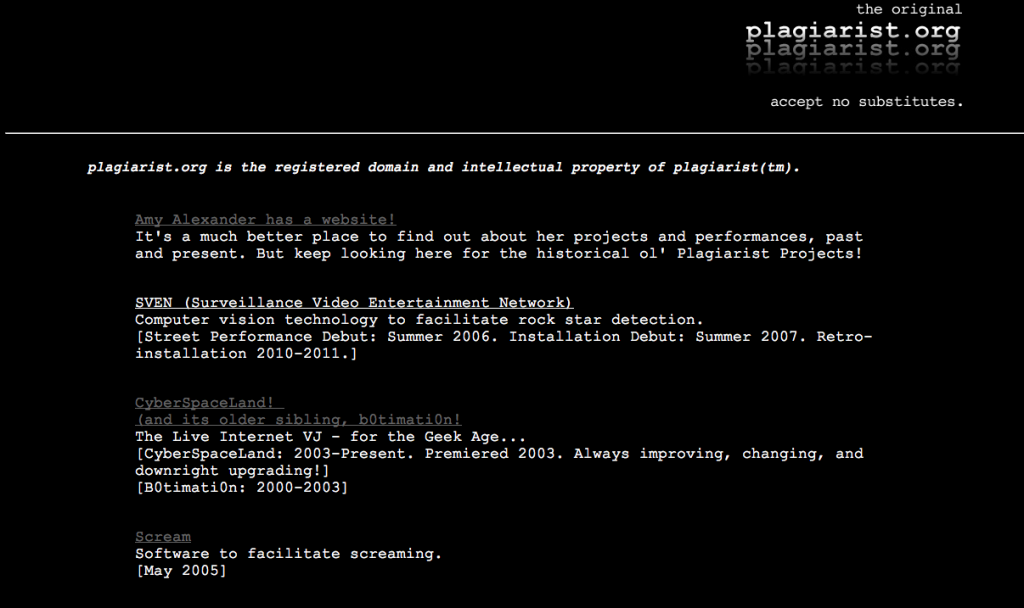

Nick Briz

Nick Briz is a newmedia artist, educator and organiser based in Chicago IL. His work has been shown internationally at festivals and institutions, including the FILE Media Arts Festival (Rio de Janeiro, BR); Miami Art Basel; the Images Festival (Toronto, CA) and the Museum of Moving Image (NYC). He has lectured and organized events at numerous institutions including STEIM (Amsterdam, NL), the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Marwen Foundation and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His work is distributed through Video Out Distribution (Vancouver, CA) as well as openly and freely on the web.

Benjamin Gaulon

Benjamin Gaulon is an artist, researcher and art college lecturer. He has previously released work under the name “Recyclism”. His research focuses on the limits and failures of information and communication technologies; planned obsolescence, consumerism and disposable society; ownership and privacy; through the exploration of détournement, hacking and recycling. His projects can be softwares, installations, pieces of hardware, web based projects, interactive works and are, when applicable, open source.

José Irion Neto

José Irion Neto is native of Santa Maria, in southern Brazil. His first contact with computers was in 1982 using a machine equivalent to Sinclair ZX Spectrum. He has an academic background in Media Advertising and worked for some years as a Graphic Designer. Today, he has been working with advertising only occasionally, focusing on creating posters, dedicating most of his time on developing Glitch Art. He has worked and researched Glitch since 2008.

Antonio Roberts

Antonio Roberts is a British digital artist whose artwork focuses on the errors and glitches generated by digital technology. Many people would simply discard such artefacts but Antonio preserves these errors and displays them as art. With his roots in free culture he develops his techniques using open source and freely available software and shares his knowledge through the development of software.

Ant Scott

Ant Scott (UK) is a glitch artist and co-author of the first glitch aesthetics coffee table book Glitch: Designing Imperfection (New York: MBP, 2009). His work is informed by cognitive distortions.

Rosa Menkman

Rosa Menkman is a Dutch visualist who focuses on visual artifacts created by accidents in digital media. The visuals she makes are the result of glitches, compressions, feedback and other forms of noise. By combining both her practical as well as an academic background, she merges her abstract pieces within a grand theory artifacts (a glitch studies), in which she strives for new forms of conceptual synthesis of the two. In 2011 Rosa wrote Glitch Moment/um, a notebook on the exploitation and popularization of glitch artifacts (published by the Institute of Network Cultures), organized the GLI.TC/H festivals in both Chicago and Amsterdam and co-curated the Aesthetics Symposium of Transmediale 2012.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England

Scratch is a programming environment that is easy to use and created with children in mind. Create and share your own interactive stories, games, music and art!

MaKey MaKey is a kit that lets you turn anything into a controller. Let your imagination go wild!

Codasign in partnership with Furtherfield will be running two Scratch + MaKey MaKey workshops for children and their parents at Furtherfield Gallery on Sunday 14 April: a morning session with 6-9 year olds (10-12pm) and an afternoon one with 9-12 year olds (1:30-4pm).

Please book your place.

All supporting material for the workshop will be available at learning.codasign.com.

During this workshop, the children will practice using computational thinking and interactive design in creative projects through a variety of activities. The adults will even play a key role in these activities.

You only need to have big ideas – no other experience required.

You need to bring a laptop and an adult. The same adult can accompany multiple children. If you aren’t able to bring a laptop, just let us know by adding a note to your registration or e-mailing info@codasign.com.

There will be drinks available, but you are welcome to bring along some snacks to feed your creativity.

Full refund if registration is cancelled over a week before the course start, 50% if within a week of the course start, and no refund if within 24 hours of the course start.

VISITING INFO

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Scratch is a programming environment that is easy to use and created with children in mind. Create and share your own interactive stories, games, music and art!

MaKey MaKey is a kit that lets you turn anything into a controller. Let your imagination go wild!

Codasign in partnership with Furtherfield will be running two Scratch + MaKey MaKey weekend workshops for children and their parents at Furtherfield Gallery on Saturday 16 and Sunday 17 March: a morning session with 6-9 year olds (10-12pm) and an afternoon one with 9-12 year olds (1:30-4pm).

Please book your place.

All supporting material for the workshop will be available at learning.codasign.com.

During this workshop, the children will practice using computational thinking and interactive design in creative projects through a variety of activities. The adults will even play a key role in these activities.

You only need to have big ideas – no other experience required.

You need to bring a laptop and an adult. The same adult can accompany multiple children. If you aren’t able to bring a laptop, just let us know by adding a note to your registration or e-mailing info@codasign.com.

There will be drinks available, but you are welcome to bring along some snacks to feed your creativity.

Full refund if registration is cancelled over a week before the course start, 50% if within a week of the course start, and no refund if within 24 hours of the course start.

VISITING INFO

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Scratch is a programming environment that is easy to use and created with children in mind. Create and share your own interactive stories, games, music and art!

Codasign in partnership with Furtherfield will be running two Scratch weekend workshops for children and their parents at Furtherfield Gallery on Saturday 09 and Sunday 10 March: a morning session with 6-9 year olds (10-12pm) and an afternoon one with 9-12 year olds (1:30-4pm).

Please book your place.

All supporting material for the workshop will be available at learning.codasign.com.

What will you do and learn?

You will design and make a game or animation using the Scratch environment.

What do you need to already know?

You only need to have big ideas – no other experience required.

What do you need to bring?

You need to bring a laptop and an adult. The same adult can accompany multiple children. If you aren’t able to bring a laptop, just let us know by adding a note to your registration or e-mailing info@codasign.com.

What will be available during the workshop?

There will be drinks available, but you are welcome to bring along some snacks to feed your creativity.

Cancellation Policy

Full refund if registration is cancelled over a week before the course start, 50% if within a week of the course start, and no refund if within 24 hours of the course start.

VISITING INFO

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Scratch is a programming environment that is easy to use and created with children in mind. Create and share your own interactive stories, games, music and art!

MaKey MaKey is a kit that lets you turn anything into a controller. Let your imagination go wild!

Codasign in partnership with Furtherfield will be running two Scratch + MaKey MaKey workshops for children and their parents at Furtherfield Gallery on Saturday 23 February: a morning session with 6-9 year olds (10-12pm) and an afternoon one with 9-12 year olds (1-4pm).

Please book your place.

All supporting material for the workshop will be available at learning.codasign.com.

What will you do and learn?

During this workshop, the children will practice using computational thinking and interactive design in creative projects through a variety of activities. The adults will even play a key role in these activities.

What do you need to already know?

You only need to have big ideas – no other experience required.

What do you need to bring?

You need to bring a laptop and an adult. The same adult can accompany multiple children. If you aren’t able to bring a laptop, just let us know by adding a note to your registration or e-mailing info@codasign.com.

What will be available during the workshop?

There will be drinks available, but you are welcome to bring along some snacks to feed your creativity.

Cancellation Policy

Full refund if registration is cancelled over a week before the course start, 50% if within a week of the course start, and no refund if within 24 hours of the course start.

VISITING INFO

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

MaKey MaKey is a kit that lets you turn anything into a controller. Let your imagination go wild!

Codasign in partnership with Furtherfield will be running two MaKey MaKey workshops for children and their parents at Furtherfield Gallery on Saturday 16 February: a morning session with 6-9 year olds (10-12pm) and an afternoon one with 9-12 year olds (1-4pm).

All supporting material for the workshop will be available at learning.codasign.com.

What will you do and learn?

During this workshop, the children will practice using computational thinking and interactive design through a variety of activities.

What do you need to already know?

You only need to have big ideas – no other experience required.

What do you need to bring?

You need to bring a laptop and an adult. The same adult can accompany multiple children. If you aren’t able to bring a laptop, just let us know by adding a note to your registration or e-mailing info@codasign.com.

What will be available during the workshop?

There will be drinks available, but you are welcome to bring along some snacks to feed your creativity.

Cancellation Policy

Full refund if registration is cancelled over a week before the course start, 50% if within a week of the course start, and no refund if within 24 hours of the course start.

VISITING INFO

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Scratch is a programming environment that is easy to use and created with children in mind. Create and share your own interactive stories, games, music and art!

Codasign in partnership with Furtherfield will be running two Scratch workshops for children and their parents at Furtherfield Gallery on Saturday 09 February: a morning session with 6-9 year olds (10-12pm) and an afternoon one with 9-12 year olds (1-4pm).

Please book your place.

All supporting material for the workshop will be available at learning.codasign.com.

What will you do and learn?

You will design and make a game or animation using the Scratch environment.

What do you need to already know?

You only need to have big ideas – no other experience required.

What do you need to bring?

You need to bring a laptop and an adult. The same adult can accompany multiple children. If you aren’t able to bring a laptop, just let us know by adding a note to your registration or e-mailing info@codasign.com.

What will be available during the workshop?

There will be drinks available, but you are welcome to bring along some snacks to feed your creativity.

Cancellation Policy

Full refund if registration is cancelled over a week before the course start, 50% if within a week of the course start, and no refund if within 24 hours of the course start.

VISITING INFO

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

THE CRYSTAL WORLD

The White Building, London

3 August – 30 August 2012

The Space’s White Building cultural centre is within walking distance of the 2012 Olympic stadium in post-industrial, post-regeneration London. As I walked down the steps that lead to it I saw a diesel locomotive pulling a train of cargo containers across an old railway bridge over the canal nearby. Millions of these rational forms will be in transit around the world at any given moment, arranged in two or three dimensions like crystalised capital on trains and docks and ships.

The logistics of their production and distribution are determined by computing machinery using algorithms that operate with inhuman speed and complexity. This same economic logic warps the architecture of the area around The White Building, with old factories and warehouses retro-fitted as office space and as gallery space.

Inside the White Building’s project space the computational enabling technology of the global economy is the subject of a show by Martin Howse, Ryan Jordan and Jonathan Kemp. It takes the title of J. G. Ballard’s novel “The Crystal World” as its starting point. In Ballard’s novel a virus progressively turns all life – vegetable, animal and human – into crystal forms frozen in time. It is a Cold War allegory of the catastrophic imposition of rigid order.

For Howse, Jordan and Kemp these imaginary crystals become the very real minerals refined in the production of the computing machinery used to structure our contemporary world. Inside every digital computer are wires, circuit boards, integrated circuits and other components. They are made from iron, copper, phosphorous, boron, tantalum and other rare earth elements. The central processing unit of a computer keeps time using a quartz crystal. The products of deep geological time are suddenly unearthed and set to pulsating millions of times a second.

Computers are crystal engines. They are mineral fetishes that we use to manipulate powerful unseen forces that we believe we have mastered, like crystal healers working with a patient’s energy grid. But they are so invisibly familiar to us as our smartphones and laptops and their use in logistics and media is so pervasive that it takes an effort for us to perceive their operation or their implications.

It takes almost two tonnes of raw materials to make a desktop PC. Unlike “Tantalum Memorial” (2008), by Harwood, Wright and Yokokoji, “The Crystal World” focuses on these raw materials geologically and temporally rather than geopolitically. But computing waste is toxic and valuable. The former makes disposing of old computers a growing problem, the latter makes recycling old computers a growing business. The minerals that computers contain can be recycled where they are valuable enough, or left to leach into the water supply in e-waste dumps where they are not.

Or in the case of “The Crystal World” an open laboratory and the resultant art installation can re-extract them from their components and printed circuit boards using acid, water, electricity and heat in order to re-crystalise them and return them to geological time. The gleaming silent boxes that organize and mediate our lives are returned if not to the earth from whence they came then at least to their raw materials.

Tables edge the White Building project space, covered with the equipment and results of five days of workshops (and one with books, including Ballard’s, giving any spectators unsure of what is happening a conceptual framework to proceed from). Table after table of crystals, circuit boards, jars, electical equipment, and wires are overwhelming in the details of their appearance and implication. These traces of human activity and inquiry frame the flow of water and electricity in the center of the space, convincing the viewer of the creative intent of its production and drawing them in to its logical universe.

The centre piece of the show is a favela chic water feature that drips acid-loaded water through calcinous rock fragments, over e-waste, into two cut plastic-drum tanks. Next to it an array of smaller plastic containers contain circtuit boards having their copper leeched from them by acid, fungus growing on the by-prodcucts of the project, and other watery deconstructions of computing machinery. It looks dangerous and uncertain, deconstructing both the physicality and the meaning of computers. Seeing the innards of an IBM ThinkPad computer becoming encrusted with calcium like a digital stalagtite, or CPUs branching feathery crystals, returns computing machinery to its raw mineral state. FLOPS give way to eons once more. Neither is a human timescale, yet we must live between them at the moment.

The most fantastical artifact along the walls of the project space is the “Earth Computer”. It’s a battery-like construct of recycled copper and zinc in a tray of silver nitrate attached to lightning conductor-style copper strips. Sitting in earth on a plastic sheet and surrounded by the left-over materials of its creation for the duration of the show, it will be buried nearby afterward. Such a device can function effectively, but not literally. It is more likely to spring to life in the mind of the viewer than if it is struck by lightning. It is effective art, psychic engineering rather than technological cargo culting.

Acid, water and electricity mixed together with e-waste look and feel dangerous. The recycled ad-hoc materials and equipment containing and channeling them reinforce this feel and leaven it with an aura of creative investigation. The form of the show is timeless, the workshop of the alchemist, outsider scientist, or mad inventor. Its content is very contemporary, from Ballard’s rising cultural stock and the social and environmental costs of e-waste to Long Now deep time and posthuman philosophy. Art symbolically resolves the gaps between ideology and reality, and computing is so pervasive and key to society that most people don’t even regard it as ideological never mind conceptualise its failings as such.

The water and abandoned human artefacts of some of the installations is more “Drowned World” than “Crystal World”, and the broken machinery is more “Crash”. Ballard’s catastrophes provide a modern mythology that is a more useful resource for art than its literary roots might suggest. It achieves the defamiliarising and critical impact of hauntological art without requiring its supernaturalism or nostalgia. There is a Ballardian attitude at play here.

I found “The Crystal World” mind-blowing. It relates the tools of our human existence to non-human substances and timescales, providing the kind of corrective to anthropocentric vanity that object-oriented philosophy aspires to. It achieves this profound insight and presents it in an accessible way precisely because of the modesty of its materials and aesthetics, and because of the resonances of the cultural materials chosen as its starting point.

http://spacestudios.org.uk/whats-on/events/the-crystal-world-open-laboratory-exhibition-

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Featured image: Jon Satrom (left) and jonCates at Intuit, Sept. 20, 2012 (right). image: Shawne Michaelain Holloway

Post-Static: Realtime Performances by jonCates and Jon Satrom @ Intuit, the Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art (Chicago). September 20, 2012. Programmed by Christy LeMaster

“Alchemy; the science of understanding the structure of matter, breaking it down, then reconstructing it as something else. It can even make gold from lead. But Alchemy is a science, so it must follow the natural laws: To create, something of equal value must be lost. This is the principle of Equivalent Exchange. But on that night, I learned the value of some things can’t be measured on a simple scale.”[1]

In 1966, Bell Laboratories scientists and engineers collaborated with artists to construct several performance-based installations under the title 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering. Works included Variations VII by John Cage and performance engineer Cecil Coker, in which a sound system pulled sounds from radio, telephone lines, microphones and musical instruments, and Carriage Discreteness by Yvonne Rainer and performance engineer Per Biorn, a dance event controlled by walkie-talkie and TEEM (theatre electronic environment modular system). Critic Lucy Lippard was wrote that the event was filled with technical problems and that the artists involved allowed the technology to take precedence over the art. She pointed out that no theatre people took part in the event and suggested that while this event did not offer a specific design for a new approach to theatre, it revealed the possibility that new approaches to theatre might be born from the combination of art and technology:

A new theater might well begin as a non-verbal phenomenon and work back towards words from a different angle. Departing from Samuel Beckett’s highly verbal, single-image emphasis, it could move into an area of perceptual experience alone, its tools a more primitive use of sight and non-linguistic sound. Such a theater would not necessarily be the amorphous carnival of psychedelic fame but could be as rigorously controlled as any other.[2]

She also observed that it was often impossible to understand the relationship between the technology and the events it triggered without reading the program, mentioning one such missed connection in Open Score, by Robert Rauschenberg and performance engineer Jim McGee. In this piece, tennis rackets were wired such that each impact of the ball on a racket turned off one light in the performance hall. Lippard wrote that this connection was not noticeable and thus the conceptual framework of the piece was lost to the audience.

To artists working at the intersection of art and technology more than forty years after this event, it is disturbing to note that the same issues Lippard pointed out —the subjugation of concept to technology, the failure of the technology itself and the lack of a radical approach to the intersection— are still all too present in many works taking place in the worlds of new media art [3]

. None of these were issues for jonCates or Jon Satrom as each presented a performance intersecting with the exhibition “Ex-Static: George Kagan’s Radios” at Intuit, the Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago, IL. Their performances serve as examples of new media employed as a tactic in support of art rather than “new media art” as a condition represented by infatuation with expensive devices. Instead of yet another demo of “cool” tech, the audience experienced a rigorously controlled blast of chaos.

The lights go down completely and we are illuminated by a large amorphous video projection behind a table stacked with equipment. The video is black and white as is the video monitor facing us from the table. jonCates moves between the back and front of the table, with purpose. While the equipment stack is familiar, multiple mixers and cases, this is no DJ set. Much closer is the image of a few men in long sleeves and ties tending to tables full of equipment for John Cage’s “Variations VII”. With several nondescript devices on and adjusted, the air around us has become alive with a noisy drone that, by this date and to this audience, is very familiar (parallels extend back to sonic attacks from Peter Christopherson and Chris Carter with Throbbing Gristle) but now the sound is comforting, an aural field that is neither alien nor distracting.

A droning, machine sound, or the droning machine sound, has become a ridiculously common element of a contemporary “experimental” sound and video work. It is thus all the more surprising to be instantly drawn into jonCates’ audio, to take pleasure in it and to lose track of time completely. We are watching him control the mixer and occasionally speak into the microphone that is set in front of a conspicuous security camera. Again, jonCates uses the most expected situation —the camera faces upward toward the video projection screen, creating a counter-clockwise tilting feedback loop. And again, we are not distracted by this, it is familiar yet beautifully framed and we are drawn in. We have been invited to a field constructed by a tactician expertly employing simple situations.

The raw quality of both the droning audio and the feedback loop combine with jonCates’ humble appearance to remove the expectation of a spectacle and we return to the real situation with questions: who is this man and what is he going to do? He keeps speaking into the microphone, his eyes look desperate, and, despite seeing him perform a similar (although much less engaging) performance at the 2011 Gli.tc/h festival, we are surprised as we realize, as it is nearly two-thirds complete, what he is doing: giving a lecture.

jonCates has been speaking for some time but only a few echoed fragments are reaching out beyond the drone. It has been an incantation without purpose, a repetition of the meaningless words one says when one is presenting something to an audience. Finally, jonCates drops the distortion and the volume on the droning sound and his voice becomes clearer. It is obvious that some communication is going to happen and everyone shifts slightly as we strain to remember how to listen to a voice. Are we here to see another performance or hear something important?. The voice is not strong and it has no authority. It is perfectly ordinary, slightly academic with a hint of vulnerability. It’s the voice of a mad scientist who has begun to understand that his experiments may be his undoing. At this point the piece could collapse and jonCates has not propped himself up with his technology. Instead, he’s used it to lead us to key moments and obliterating everything else. Still, he seems not so much frightened as curious to see where this will end, if what he needs to say can be given a short lifespan in this space. This is where performance lives —in the unfolding present. And jonCates says:

“…and I thought [?] … I thought [?] about how I should remix something in realtime for you that I should reflect upon the past, I should reflect upon [?] …patterns so I thought that I should probably do this as a remix and render it in realtime for you but then I found … from 1997…and it was sitting right next to the first tape … it was sitting right next to the first tape, had the same title as the first one, that also said “Flow” and right next to it had another a label that said “Remix” and I thought ‘I already made that piece’ [sampled voice droning: ‘oceanic waves upon waves upon waves upon waves’] and that’s almost too good to be true so I put the tape called ‘remix’ into the VCR, not this VCR. I had to buy a new VCR that VCR broke and … called ‘remix’ .. rendered in realtime for you … and I watched it, and almost [? ] [?] decide … I had already … [sampled voice droning: ‘we can stay in the spell of the laser lights’] … and I’ve been thinking about these things … [sampled voice droning: ‘we are all together … in the time space continuum of … of … of …’ and the drone continues.]”[4]

“The peculiarity of the time bounce, as he mulled it over, was that the resumption of the earlier state of being not only set physical objects back to their former positions, it actually wiped out the events of the lost hour. Like daylight saving indeed! With the lost hour unhappened, even memories of the time were obliterated…They might be reliving a given moment for the fifth time, the fiftieth, the five millionth, and never notice it!”[5]

“A representation is the occasion when something is re-presented, when something from the past is shown again —something that once was, now is. For representation it is not an imitation or description of a past event, a representation denies time. It abolishes that difference between yesterday and today. It takes yesterday’s action and makes it live again in every one of its aspects —including it’s immediacy. In other words, a representation is what it claims to be —a making present.”[6]

“For every organ-machine, an energy-machine: all the time, flows and interruptions. Judge Schreber has sunbeams in his ass. A solar anus. And rest assured that it works: Judge Schreber feels something, produces something, and is capable of explaining the process theoretically. Something is produced: the effects of a machine, not mere metaphors.”[8]

They are called radio buttons because on old car radios you pushed one button and the other popped out. The performances of jonCates and Jon Satrom were developed as an intersection with the exhibition Ex-Static: George Kagan’s Radios at Intuit, the Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, on display until January 5, 2013, curated by Erik Peterson and Jeremiah Hulsebos-Spofford.

“In the wee, wee hours your mind get hazy / Radio relay towers lead me to my baby / The radio’s jammed up with talk show stations / Its just talk, talk, talk, talk, till you lose your patience”[9]

jonCates makes Dirty New Media Art, Noise Musics and Computer Glitchcraft. His experimental New Media Art projects are presented internationally in exhibitions and events from Berlin to Beijing, Cairo to Chicago, Madrid to Mexico City and widely available online. His writings on Media Art Histories also appear online and in print publications, as in recent books from Gestalten, The Penn State University Press and Unsorted Books. He is the Chair of the Film, Video, New Media & Animation department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago:

http://systemsapproach.net/

Jon Satrom undermines interfaces, problematizes presets, and bends data. He spends his days fixing things and making things work. He spends his evenings breaking things and searching for the unique blips inherent to the systems he explores and exploits. By over-clocking everyday digital tools, Satrom kludges abandonware, funware, necroware, and artware into extended-dirty-glitchy-systems for performance, execution, and collaboration. His time-based works have been enjoyed on screens of all sizes; his Prepared Desktop has been performed in many localizations. Satrom organizes, develops, and performs with I ♥ PRESETS, poxparty, GLI.TC/H, in addition to other initiatives with talented dirty new-media comrades.

http://jonsatrom.com/

So ArtForum have launched a special September issue investigating the, lets say broader, relationship between new media, technology and visual art.*

Of worthy mention is the essay Digital Divide by the art world’s antagonistic critic of choice Claire Bishop, a writer whom a little under 8 years ago, deservedly poured critical scorn over the happy-go-lucky, merry-go-round creative malaise that was Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics and all of the proponents involved. Since then Bishop’s critical eye has focused on the acute political antagonistic relationships, within the dominant paradigms of participatory art and the concomitant authenticity of the social.

In Digital Divide, Bishop asks a different question, and its delivered even more bluntly than usual. Why has the mainstream art world, for the most part, refrained from directly responding to the ‘endlessly disposable, rapidly mutable ephemera of the virtual age and its impact on our consumption of relationships, images and communication.‘ This is not to say the practices of mainstream artists do not rely on digital media (in almost all cases, it now cannot function without it), but why hasn’t the shifting sands of digital culture been made explicit? In Bishop’s words;

“[H]ow many really confront the question of what it means to think, see, and filter affect through the digital? How many thematize this, or reflect deeply on how we experience, and are altered by, the digitization of our existence?”

Clearly, there are exceptions and she mentions three examples by art stars Frances Stark, Thomas Hirschhorn and Ryan Trecartin which flirt here and there with digital thematisation. Conversely artists who once specialised in digital art, Cory Arcangel, Miltos Manetas – to name two very famous examples – have previously broken out into the mainstream.

But for Bishop, there is of course, “an entire sphere of “new media” art, but this is a specialised field of its own: It rarely overlaps with the mainstream art world (commercial galleries, the Turner Prize, national pavilions at Venice)” – (one could add art fairs here). But nonetheless “these exceptions just point up the rule“. Bishop’s focus is on the mainstream and, moreover, she contends that “the digital is, on a deep level, the shaping condition—even the structuring paradox—that determines artistic decisions to work with certain formats and media. Its subterranean presence is comparable to the rise of television as the backdrop to art of the 1960s.” True enough, this structuring paradox is an implicit problem with the mainstream art world, but thats not the problem tout court.

From the responses I’ve read both in the article comments and in subsequent blog posts, a particular issue has been marked with Bishop’s statement that “new media” art is a specialised field. Whilst it doesn’t qualify as a dismissal, one could certainly suggest that Bishop is partly guilty of the same disavowal she throws at the mainstream art world when she relegates this sphere as an ‘exception’. In a blog-post response, Kyle Chayka makes a similar point; “Bishop understands that digital technology forms a seedbed for art as well as life, but fails to uncover the artists who are already critiquing that context.” I’m not a Lacanian, but maybe this is a symptom of something.

If mainstream art is ‘the rule’, (and I’m insinuating ‘the rule’ as anti-metaphor here) perhaps ‘the rule’ isn’t worth paying attention to, considering that the new media art exception is too much of a ‘specialisation’. In as much as one can only agree with Bishop’s call for mainstream art’s negotiation with digital thematisation, has she not missed the same aesthetic questions already posed and re-composed in this exceptional sphere? Why should the qualifier of the mainstream be such a factor of importance here? Why not cut off the need to reconcile digital thematisation with a set of historical, and commercially ideological principles which may not take kindly to the more ambitious and darker questions that the social and political arena of global digitalisation have thrown up. This is not to say that Bishop isn’t seeking those questions nor does she wish to reconcile those principles, but the specialised sphere of ‘new media art’ may quench the questions she herself raises.

Case in point: all Bishop would have needed to reference is something like the Dark Drives exhibition for the transmediale festival earlier this year; the tag line “uneasy energies in Technological Times” sums up her main descriptions of a digital epoch quite nicely. For instance, the artist group Art 404’s 5 Million Dollars 1 Terabyte, renders explicit one subset of the absurd, copyright, exploitative logic of proprietary software, by saving one terabyte’s worth of unlicensed software onto a single hard drive. Next to it was JK Keller’s idiosyncratic piece Realigning My Thoughts on Jasper Johns, which showed off a glitchy, abstract bastardisation of a Simpson’s episode Mom and Pop Art – regurgitating haggard mainstream perspectives. Crucially the success of the show was down to the implicitness of the exhibition’s technical triumphs – where technical jargon is often touted as a reason for the mainstream’s averted gaze. Whilst the viewer didn’t need to know the technics, but a richer understanding emerged should they have wanted to know.

There isn’t any need to clog up this article with a bottomless plethora of pieces from other equally important exhibtions and shows (I’m sure many others are better qualified in doing so); my point here, is that Bishop cannot relegate new media art as an exception to the rule, when the digitalisation of media is becoming the rule, which she herself explicitly admits. Choosing to focus on the failure of the mainstream in this arena gives the essay a healthy line of questioning, but in relegating an entire sphere which has – for some time – repeatedly dealt with these questions and more, it raises what is effectively a pointless query. To be fair to Bishop, she isn’t trying to force a fecund translation of new media with mainstream values, but looking for methods where digitalisation can instigate the change of those values.

Granted, Dark Drives is one major show in a major Berlin new media festival – the top of a very extensive collection of disparate voices and influences – but it inadvertently highlights a salient thought. What if Bishop’s call to bridge the ‘Digital Divide’ was actually met by a new generation of artists thrust into the mainstream, where digital themes were translated into its own methods of commercial production? We’ve gotten over the myth that ‘virtual’ commodities are unmarketable, so it’s not as if I’m being negative for the sake of it. Where would this leave festivals like transmediale, or not-for-profit collectives like Furtherfield – how would they respond? It’s an uneasy question, one which for speculative purposes cannot be answered quickly at present, if at all.

In the throws of conjecture, there is perhaps another division at play here. Towards the end of her essay, Bishop makes a reference to the difference between the non-existent embrace of the digital medium today, and the rapid embrace of photography, film and video in the 60s and 70s.

“These formats, however, were image-based, and their relevance and challenge to visual art were self-evident. The digital, by contrast, is code, inherently alien to human perception. It is, at base, a linguistic model. Convert any .jpg file to .txt and you will find its ingredients: a garbled recipe of numbers and letters, meaningless to the average viewer. Is there a sense of fear underlying visual art’s disavowal of new media?”

This is a division which is even more striking; more aesthetically and philosophically significant in comparison to marketable rules and unmarketable exceptions. I think Bishop is really on to something when she chastises the hybrid solutions of old media nostalgia, evidently favoured by the market and contrasts it to the alien nature of code, but it’s not without problems.

Some may consider there to be nothing inherently alien about digital media; many artists, who also work as programmers and write, design and engineer artworks together with code without any recourse to an alien nature (however I vehemently disagree with the notion that code be solely reduced to human production, but it must be pointed out) Likewise, any 90s utopian reading of the ‘digital revolution’ is mired from the start, once you take into consideration, closed proprietary devices and services which falsify other meaningful alternatives (one only needs to trace the important work of the Telekommunisten art collective to realise how advanced these questions are, in what is supposed to be a specialised field).

If there is a fear underlying visual art’s disavowal of digitalisation, it’s not just a critical bemusement of code, but of the material which composes computational media; wires, LCD screens, motherboards, caches, firmware, sorting algorithms. Bishop’s call for mainstream contemporary art to be aware of its own conditions and circumstance is admirable, but unless art can actually get its hands dirty with the material processes of new media and more importantly the underlying computational conditions concerning the digital (because thats what it is), the project of explaining these circumstances will be quagmired from the start. It’s not enough to explain ‘our changing experience’ with computation, but to explain the experience of computation in itself.

But for now, lets keep the divide going, not least because antagonisms are fun (Bishop should know), but because the contemporary digital arts are not hindered with the burden of seeking the mainstream’s attention. They can get away with a lot more as a result. Digital or Computational art needs to be cheaper and nastier, as the artist’s tools of use are getting increasingly dirty with critical engagement and proflierfation of code (one cannot avoid mentioning Julian Oliver et al’s important project of critical engineering in this sense). Only then, can Bishop speak of a moment, where the “treasured assumptions” of mainstream art are brought to bear through the criticality of the digital.

——————

* Just to make it clear, I am aware that key terms in this article such as ‘new media’ ‘digitisation’, etc carry little to no relevance anymore, (I prefer computational to be more relevant myself), and they’re only used as a replying dialogue with Claire Bishop’s essay which relies on them throughout.