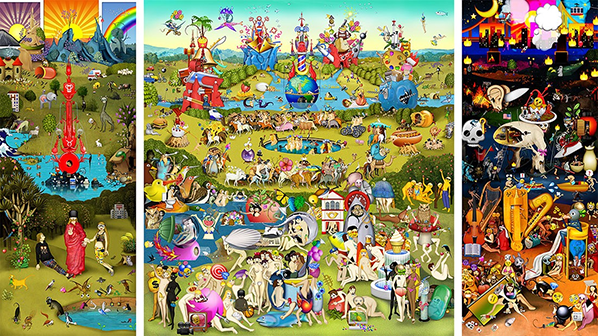

In 2019 we celebrate the 150th anniversary of Finsbury Park, and we time travel through its past and future with the launch of our Citizen Sci-fi programme and methodology. Dominant sci-fi franchises of our time, from Black Mirror to Westworld, have captured popular attention by showing us their apocalyptic visions of futures made desperate by systems of dominance and despair.

What is African-American author, Octavia E. Butler’s prescription for despair? Sci-fi and persistence. Sci-fi as a tool for getting us off the beaten-track and onto more fertile ground, and persistent striving for more just societies.The 2015 book Octavia’s Brood honoured her work, with an anthology of sci-fi writings from US social justice movements and this inspired us to try a new artistic response to the histories and possible futures of Finsbury Park.

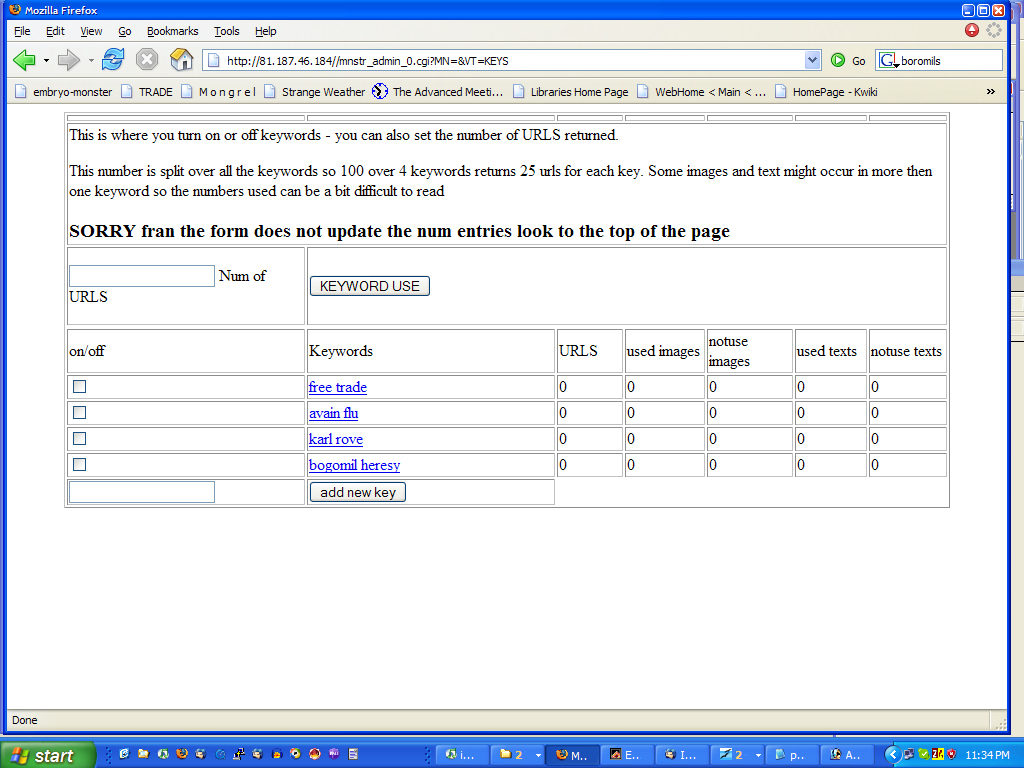

Furtherfield’s Citizen Sci-Fi methodology combines citizen science and citizen journalism by crowdsourcing the imagination of local park users and community groups to create new visions and models of stewardship for public, urban green space. By connecting these with international communities of artists, techies and thinkers we are co-curating labs, workshops, exhibitions and Summer Fairs as a way to grow a new breed of shared culture.

Each artwork in the forthcoming exhibition invites audience participation – either in it’s creation or in the development of a parallel ‘people’s’ work – turning every idea into a portal to countless more thoughts and visions of the past and future of urban green spaces and beyond.

So where do we start? Last year we invited artists, academics and technologists to join us in forming a rebel alliance to fight for our futures across territories of political, cultural and environmental injustice. This year both our editorial and our exhibition programme are inspired by this alliance and the discoveries we are making together.

To kick off this year’s Time Portals programme at Furtherfield, in April we will host the launch and discussion around Jugaad Time, Amit Rai’s forthcoming book. This reflects on the postcolonial politics of what in India is called ‘jugaad’, or ‘work around’ and its disruption of the neoliberal capture of this subaltern practice as ‘frugal innovation’. Paul March-Russell’s essay Sci-Fi and Social Justice: An Overview delves into the radical roots and implications of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). This is a topic close to our hearts given our own recent exhibitions Monsters of the Machine and Children of Prometheus, inspired by the same book. Meanwhile we’ve been hosting workshops with local residents exploring our visions for Finsbury Park 150 years into the future. To get a flavour of these activities Matt Watkins’ has produced an account of his experience of the Futurescapes workshop at Furtherfield Commons in December 2018.

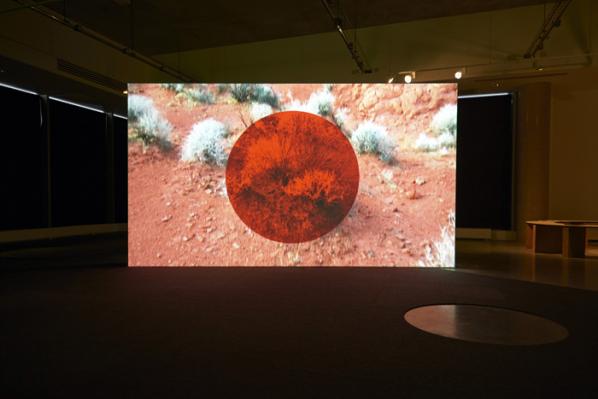

In May we will open the Time Portals exhibition which features several new commissions. These include Circle of Blackness by Elsa James. Through local historical research James will devise a composite character to embody the story of a black woman from the locality 150 years ago and 150 years in the future. James will perform a monologue that will be recorded and produced by hybrid reality technologist Carl Smith and broadcast as a hologram inside the Furtherfield Gallery throughout the summer. While Futures Machine by Rachel Jacobs is an Interactive machine designed and built through public workshops to respond to environmental change – recording the past and making predictions for the future while inspiring new rituals for our troubled times. Once built, the machine occupies Furtherfield Gallery, inviting visitors to play with it.

Time Portals opens on May 9th (2019) with other time traveling works by Thomson and Craighead, Anna Dumitriu and Alex May, Antonio Roberts and Studio Hyte. Visitors will be invited to participate in an act of radical imagination, responding with images, texts and actions that engage circular time, long time, linear time and lateral time in space towards a collective vision of Finsbury Park in 2169.

From April onwards, a world of activities, workshops with local families and their enriching noises, reviews, interviews and an array of experiences will unfold. Together we dismiss the dystopian nightmares and invite communities to join us in one of London’s first “People’s Parks” to revisit and recreate the future on our own terms together.

Marc Garrett will be interviewing Elsa James, about her artwork Circle of Blackness, and Amit Rai about his book Jugaad Time. Both will soon be featured on the Furtherfield web site.

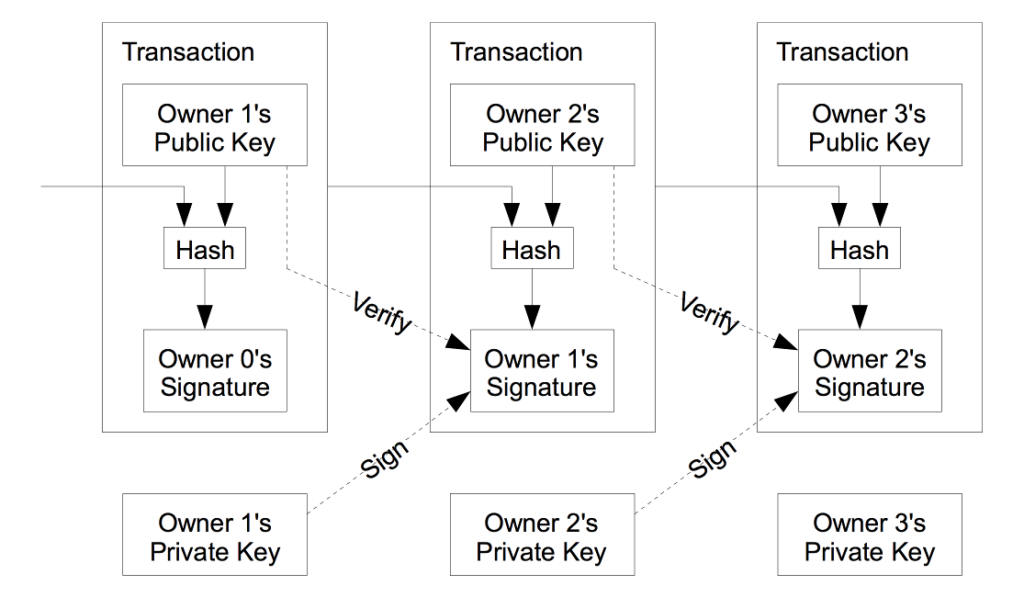

Data structures hold information in a way that makes it easier to be manipulated by software, given particular constraints on computing resources such as the time or space taken up. A linked list takes very little space in a computer’s memory on top of the space taken up by the data it contains and is very quick to add new data to but it is very slow to search from the beginning to the end of the list.

In contrast, a “hash table” data structure makes looking up information much faster by calculating a unique identifier “hash” for each item that can be used as an index entry for the data rather than having to search all the way through a long list of links. Think of a hash as a very large, very unique number that can be reliably calculated for any piece of data – any file containing the text “Hello world!” will have the same cryptographic hash as any other. The cost of this fast access is that the table must be allocated and configured in full before data can start to be stored in it.

A “binary tree” balances speed and storage space by storing data in a structure that looks like a tree with two branches at the end of each branch, creating a simple hierarchy that takes very little initial extra storage space but that given its structure is relatively fast to search compared to a linked list.

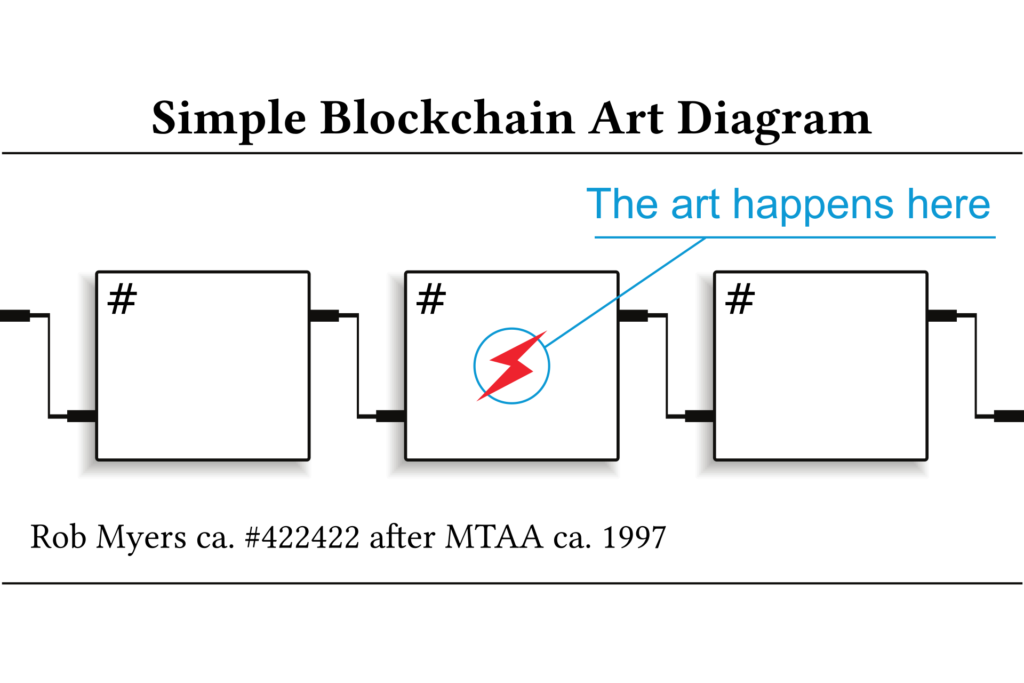

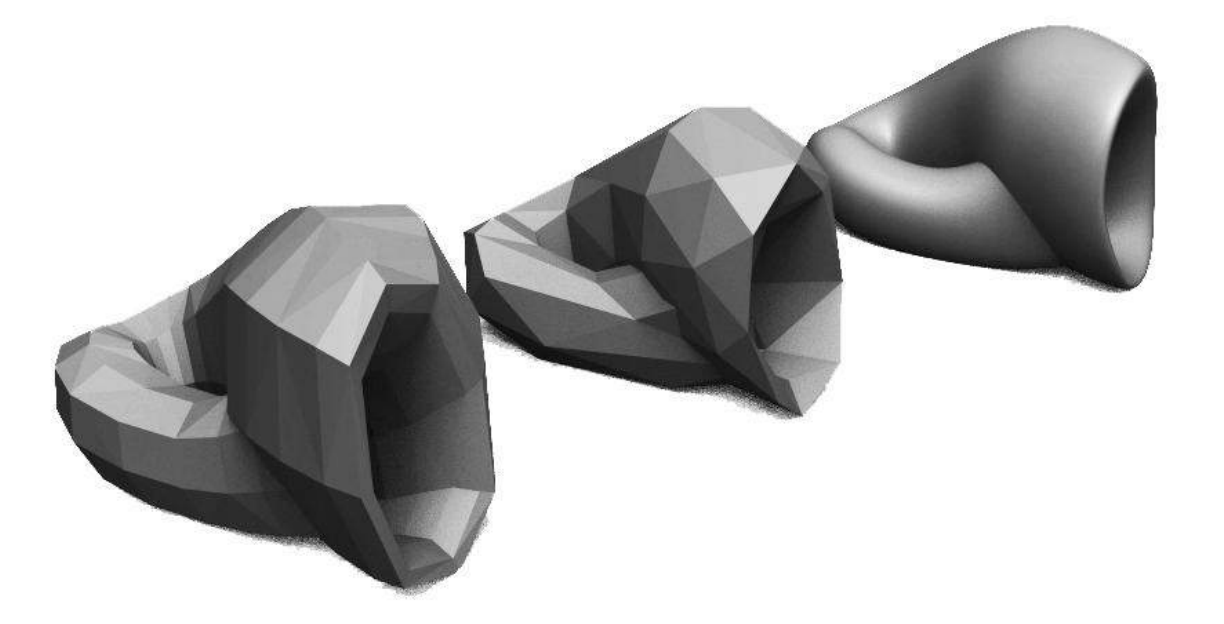

Each block in a blockchain is linked to the previous one by identifying it using its (cryptographic) hash value. And the transactions in the block are stored in a (cryptographic hash) tree. This means that a blockchain is a more complex structure than the simple image at the top of this page. But so what? Why should we care about the shape of the blockchain when its social, environmental and political impact seem to be in such urgent need of critique?

The geometric, techonomic and social form of a blockchain are all related, and understanding one helps us to reason better about the others. As the quick tour through software data structure design above indicates, the constraints on technological form are not abstract, they are tied to real needs and agendas. Bitcoin is no exception to this – the lists and trees that make up its blockchain as they are built and broadcast on a peer-to-peer network by computers competing to claim economic incentives for doing so were chosen very explicitly to exclude the intervention of the state and other “trusted third parties” (such as banks) in authentic economic relationships between peers.

Bitcoin’s algorithms prioritise the security of the blockchain above all else, maximising security like a mythical Artificial Intelligence “paperclipper” maximises the production of a particular material good regardless of the other consequences . This explains Bitcoin’s energy consumption, which whilst lower than the US military or the other equivalent systems that guarantee the security of the dollar is probably still much higher than Satoshi Nakamoto originally envisioned.

There are other algorithms, though, which have been created since 2008 to address perceived flaws in Bitcoin’s design or to address different ideological agendas. These create different forms, and contrast instructively with that of Bitcoin’s blockchain. Please note that these are experimental and often controversial technologies. Nothing that follows is investment advice.

Bitcoin creates blocks on average every ten minutes. Faster currencies quickly emerged, LiteCoin and Dogecoin are leading examples, with 2.5 minute and one minute block times respectively. Blocks may contain more or fewer transactions, and be more or less frequent even within the same blockchain as the algorithms tweak its parameters to ensure its security. Blockchains have rhythm, they stall or race, each block is larger or smaller and closer or further from the last one. Transactions fan into and out from addresses in each block, with varying values of currency or amounts of data each time. We are now very far from the block-and-arrow diagrams of linked lists indeed.

The Ethereum system, which extends Bitcoin’s financial ledger into a more general system for “smart contracts”, has the smallest block time of any leading cryptocurrency – fifteen seconds. Like the others mentioned it still uses a variant of the energy-hungry “Proof of Work” security system from Bitcoin. In Proof of Work, anyone who wants to add a block of transactions to the list must consume computing resources to solve a puzzle (essentially guessing a large number ending with multiple zeroes). As these resources cost money, anyone willing to expend them must stand to gain more from adding the next block than they lose to their electricity bill. This Game Theory gambit secures a Proof of Work blockchain. The mindlessly focussed, paperclipper nature of blockchain security algorithms means that as more people use more computers to compete to be the next person to add a block to the chain and claim the economic reward for doing so, the difficulty and therefore the amount of electricity required to solve that puzzle has increased massively, growing the energy footprint of cryptocurrency.

Ethereum is planning to switch to a “Proof of Stake” system, like that used in currencies like NXT and Decred (about which more below). Rather than burning electricity like Proof of Work, Proof of Stake uses a blockchain’s own existing currency “staked” by users to demonstrate their standing within the system and to thereby get a chance to be chosen by the network to add the next block. Proof of Stake and its related “Proof of Authority” system move from the “miners” of Proof of Work who operate on the blockchain from outside to a system of capitalist investors or even an aristocratic class of gatekeepers who operate within the logic of the blockchain itself. This folds the blockchain’s outside in on itself.

Bitcoin’s blocks have been fixed at one megabyte in size since a temporary security fix by Satoshi Nakamoto introduced the limit. As Bitcoin usage has grown, blocks have become increasingly full (allegedly often as a result of economic “spam” attacks intended to manipulate prices – competing for space in blocks drives up transaction fees which can in turn discourage users and ultimately drive down the price of Bitcoin). How should this problem be addressed – how should Bitcoin scale? Should the number of transactions stored in the blockchain grow, increasing the block size limit and making it harder for individuals to store the blockchain on consumer hardware in a decentralised manner? Or should transactions be somehow moved “off-chain” into “second-tier” systems that build on top of the blockchain, adding complexity and introducing potential new choke-points for existing capital to exploit? Big blocks or small blocks (like the big or little ends of eggs, or integers…)? This is a real debate in the Bitcoin world, and illustrates how the consequences of a simple change in technical form like, for example, increasing block sizes from one to two megabytes, can have profound effects on the social and economic form of a cryptocurrency. “Big blockers” propose solutions like the breakaway “Segwit2X” or “Bitcoin Cash” systems, scaling “on-chain” with ever greater amounts of data in the same structures. “Small blockers” propose solutions that move data out of the blockchain, into “Segregated Witnesses” that store cryptographic signatures outside of the blockchain, or the cybernetic rhizomes of “Lightning Networks”.

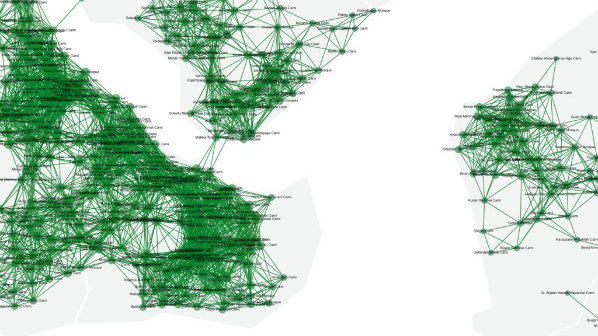

A Lightning Network adds a second peer-to-peer network of nodes that pass transactions between themselves. These are all valid Bitcoin transaction data structures, but unlike the main Bitcoin peer-to-peer network they are not immediately broadcast to the main Bitcoin network to be bundled up into blocks. Rather they can be replaced at any moment by new transactions, sending different amounts of cryptocurrency along a “channel” between one or (most often) more participants arranged in a random network like the one used by the Tor privacy network.

It’s an elegant but sometimes complex solution, and one that triggers moral panic within some elements of the Bitcoin community equivalent to that triggered by Bitcoin within some elements outside of it. Lightning Nodes with more Bitcoin can extract more fees from Lightning Network transactions, to be sure, and this is a form of centralisation. Decentralisation’s value to cryptocurrency is as a concrete guarantor of security, and Bitcoin’s value is its security. But individuals can still run Lightning Network nodes and send transactions between each other, and pools of capital already have centralising effects in exchanges and mining cartels.

Techniques similar to those used to move transactions off-chain by Lightning Networks can be used to move value between different blockchains without exchanges centralising the process. “Atomic Swaps”, the “Plasma” system and the realisation of the previously mythical “Doge-Ethereum bridge” using the TrueBit system are all different ways of building wormholes between the separate universes of individual blockchains.

Another approach to scaling is borrowed from conventional database design: breaking the blockchain into smaller and smaller pieces or “shards“, forming another tree structure, allows each group of users of the blockchain to only have to keep track of the part that contains the transactions they are interested in. The Ethereum blockchain will move to sharding in future, after its switch to Proof of Stake. Sharding destroys the metronomic, panopticonic unity of the blockchain to create islands of transactions whose truth is local to them, a non-monotonic logic that makes moving value and information between shards difficult but still not impossible.

CryptoKitties can go on their own shard, the Gnosis prediction market on another one, and if one needs to bet on something kitty-related this will require communicating cross-shard. From islands in the net to islands in the blockchain. Techonomically, the data structures and economic incentives of such a system are more complex than a unified blockchain, but making access to the network cheaper by requiring each user to store less data to send their transactions restores the blockchain’s initial low barrier of entry.

Deciding how to scale is a matter of governance. The Decred cryptocurrency has put governance front and centre. As well as moving to a hybrid Proof of Work / Proof of Stake system it has implemented an “on-chain-governance” system. Decred contains the forum for its own critique and transformation, implemented as an extension of the staking and voting system used by its Proof of Stake system. On-chain governance is controversial but addresses calls to improve the governance of cryptocurrency projects without falling prey to the off-chain voluntarism that can result from a failure to understand how the technomic and social forms of cryptocurrencies relate in finely-tuned balance.

Some post-Bitcoin systems move further away from the form of a chain or do without them altogether. The Holochain system gives each user their own personal blockchain and stores a link to it in a global “Distributed Hash Table” of entries (like that used by the BitTorrent system), a forest of trees rather than a tree of shards. This possibly solves the bandwidth problem of simple blockchain technology but weakens some of their strengths in a trade off of convenience against long-term security and robustness. Iota (the most controversial technical design discussed here) doesn’t have a blockchain at all. It uses a “tangle” of transactions, within which each new transaction must do the Proof of Work of validating several previous transactions. This seems like an ideal restoration of the original vision of Bitcoin as a peer-to-peer currency, solving the problems centralisation and energy usage, but the current Iota network is in fact heavily centralised by its reliance on nodes controlled by the Iota foundation to secure it.

IPFS is not a cryptocurrency and does not use a blockchain but it complements the blockchain technologically and often socially. IPFS is related to blockchain technology in its use of cryptography and the logic of game theory but also as a popular way of storing information that is too large to fit on the blockchain. And in its use of a cryptocurrency token – “Filecoin” – to pay for storage on its main network. Filecoin was released in an “Initial Coin Offering” in 2017, and that is all we will say about ICOs here… IPFS uses a “Merkle DAG”, a network of links similar to the World Wide Web or a filesystem, but with each item (the pages or files) represented not by a human-given name but by the cryptographic hash of its content. “Merkle” refers not to the German Chancellor but to the computer scientist who described this use of cryptographic hashes in a tree data structure (like that used in Bitcoin). “DAG” is an acronym for “Directed Acyclic Graph” – a network with no loops in it because loops would confuse the algorithm. IPFS distributes content using a “market” algorithm, bartering for blocks of data on the network with Filecoin or with other blocks.

Each of these pocket universes of social and economic reality has its own structure and forms, its own space and geometry. Chains, and being on or off of them. Blocks of different sizes and fullness, with varying distances between them. Channels, rhizomes, shards, tangles, mines and thrones. Forests, tables, graphs, markets and identities. These formal differences distinguish different cryptocurrencies technologically and politically. Algorithmic differences are ideological differences, this is not an external critique it is internal to the logic of cryptocurrency – algorithms are changed to better instantiate what is just. These algorithmic differences produce formal differences. Their surplus value and unintended consequences continue this process of critique-in-code.

The question of the shape of the blockchain opens up onto a space of technomic, geometric and social forms. We can move through the hyperspace containing and relating these forms to the specific spaces of individual blockchains that are built around them, through the constraints and agendas that they reflect, out into wider society. The gaps and overlaps in this space indicate useful problems for the work of development or critique. Given this, geometries and forms are at least as useful a navigational marker as professed intentions or revealed preferences. But only if we can imagine and visualise them.

Art deals in form, from the spatial volumes of Renaissance perspective to the choreography and logistics of Relational and Contemporary art. Whether promoting, like Jessica Angel’s public art envisioning of the Doge-Ethereum bridge as a Klein Bottle, critiquing or simply rendering perceptible the very different kinds of form that make up the geometric, technomic and social forms of the blockchain and the relationships between them, art has the unique potential to uncover the true shape of the blockchain.

Image notes:

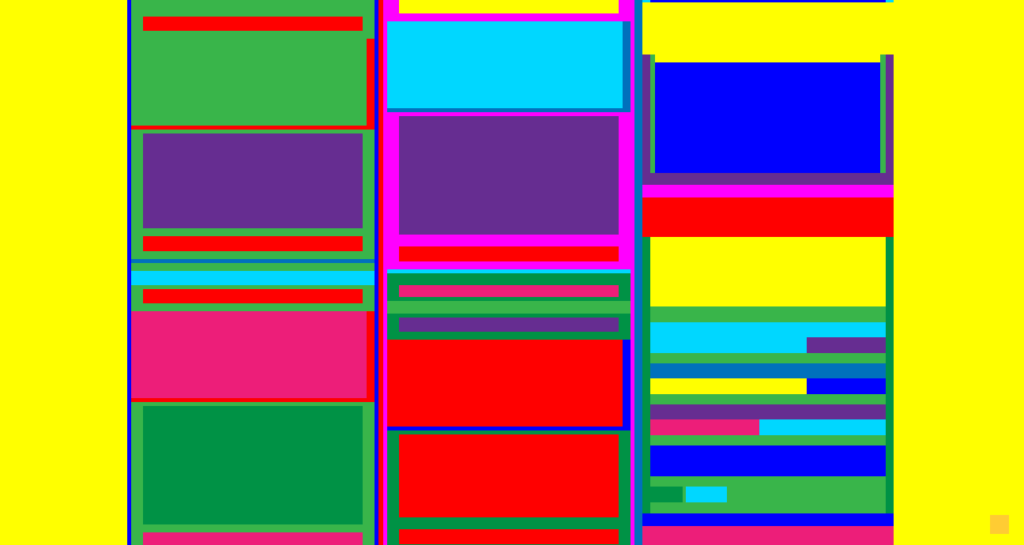

Simple Blockchain Art Diagram, by Rhea Myers. 2016

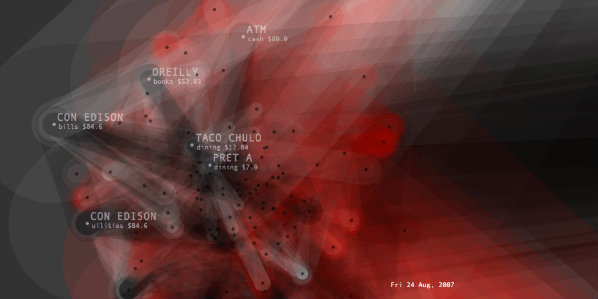

What the Silk Road bitcoin seizure transaction network looks like, Reddit

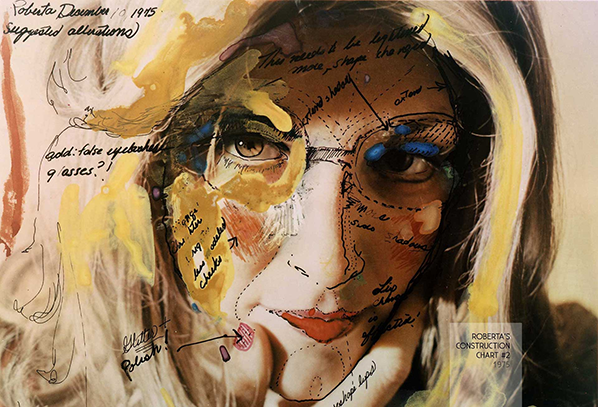

This essay is a response to Identity Trouble (on the blockchain), the second in the DAOWO lab series for blockchain and the arts. Rosamond reflects on both ongoing attempts to reliably verify identity, and continuing counter-efforts to evade such verifications.

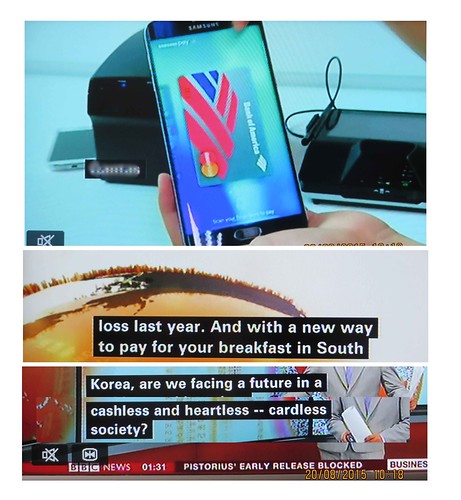

Online transactions take place in a strange space: one that blurs the distinctions between the immediate and the remote, the intimate and the abstract. Credit card numbers, passing from fingers to keyboards to Amazon payment pages, manage complex relations between personal identity and financial capital that have been shifting for centuries. Flirtations on online dating platforms – loosely tied to embodied selves with a pic or two and a profile – constitute zones of indistinction between the intimate spheres of the super-personal, and hyper-distributed transnational circuits of surveillance-capital. Twitter-bot invectives mix with human tweets, swapping styles – while all the while bot-sniffing Twitter bots try to distinguish the “real” from the “fake” voices[1]. Questions of verification – Who is speaking? Who transacts? – proliferate in such spaces, take on a new shape and a shifted urgency.

How does personal identity interface with the complex and ever-changing technical infrastructures of verification? How is it possible to capture the texture of “identity trouble” in online contexts today? The second in the DAOWO event series, “Identity Trouble (on the blockchain),” addressed these questions, bringing together a range of artists, developers and theorists to address the problems and potentials of identification, using technical apparatuses ranging from blockchain, to online metrics, to ID cards and legal name changes. The day included reflections on both ongoing attempts to reliably verify identity, and continuing counter-efforts to evade such verifications.

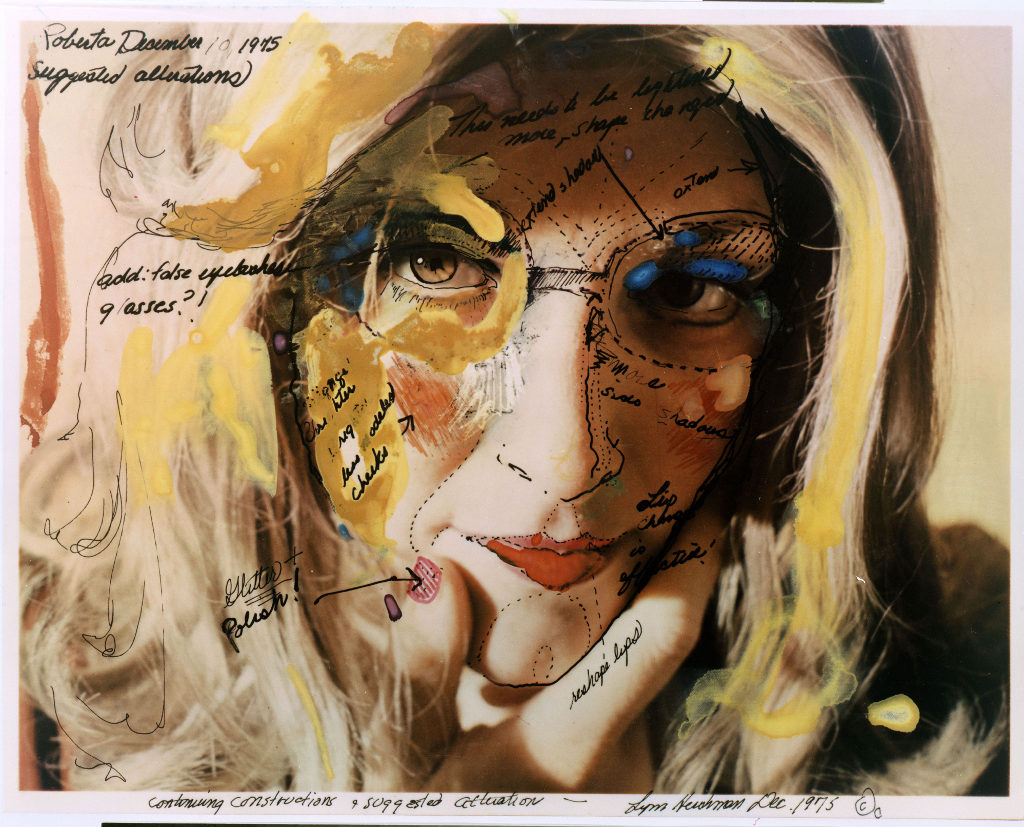

Before going into the day in any detail (and at the risk of going over some already well-trodden ground), I want to try to piece together something which might – however partially – address the deeper histories of the problems we discussed. Of course, identity was an elusive concept long before the internet; and the philosophical search to understand it has run parallel to a slow evolution in the technical and semiotic procedures involved in its verification. In fact, seen from one angle, the period from the late nineteenth century to present can be understood as one in which an increasing drive to identify subjects (using photo ID cards, fingerprints, signatures, credit scores, passwords, and, now, algorithmic/psychometric analysis based on remote analysis of IP address activity) has been coupled with a deep questioning of the very concept of identity itself.

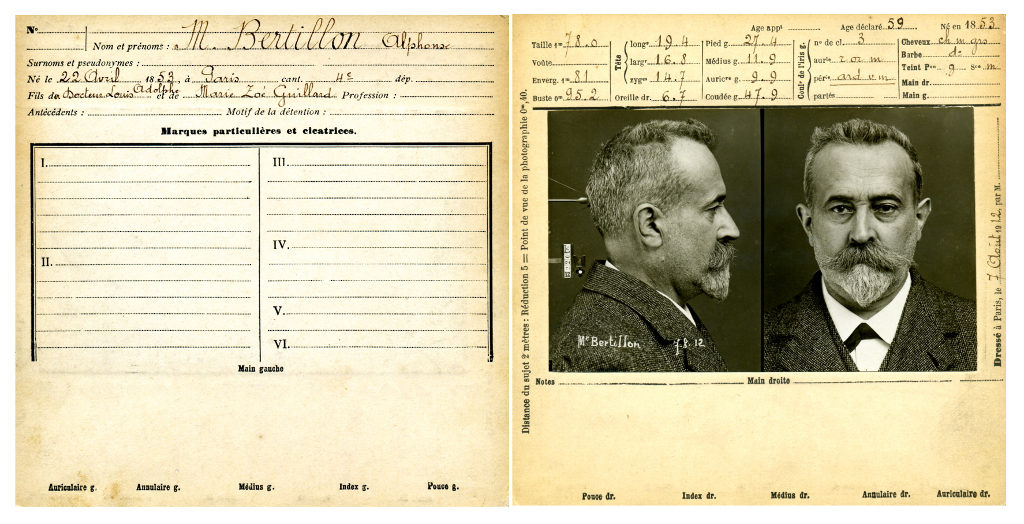

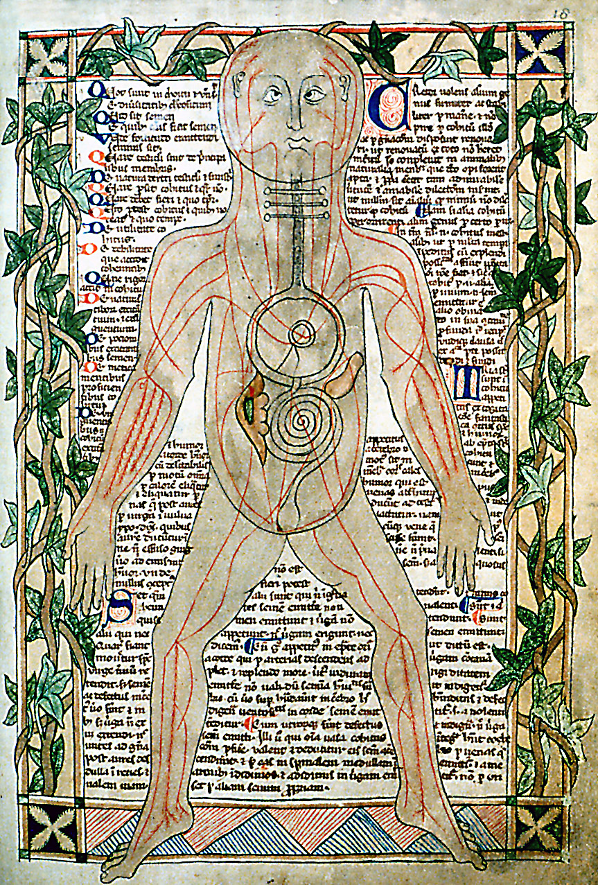

On the one hand, as John Tagg describes, in the second half of the nineteenth century, the restructuring of the nation-state and its disciplinary institutions (“police, prisons, asylums, hospitals, departments of public health, schools and even the modern factory system itself”[2]), depended on creating new procedures for identifying people. This involved, among other things, yoking photography to the evidentiary needs of the state – for instance, through Alphonse Bertillon’s anthropometric identity card system, invented in 1879 and adopted by French police in the 1880s. The identity cards, filed by police, included suspects’ photographs and measurements, and helped them spot repeat offenders.

This impulse to identify, it seems, has only expanded in recent times, given the proliferation of biometric and psychometric techniques designed to pin down persons. On the biometric end of this spectrum, retinal scans, biometric residence permits and gait recognition technologies manage people’s varying levels of freedom of movement, based on relatively immutable bodily identifiers (the retina; the photographic likeness; the fingerprint; the minute particularities of the gait). On the psychometric end of the spectrum, private companies calculate highly speculative characteristics in their customers by analysing their habits – such as “pain points.” The American casino chain Harrah’s, for instance, pioneered in analysing data from loyalty cards in real time, to calculate the hypothetical amount of losses a particular gambler would need to incur in order to leave the casino. The pain point – a hypothetical amount of losses calculated by the company, which may be unknown to the customer herself – then provided the basis for Harrah’s’ real-time micro-management of customer emotion, enabling them to send “luck ambassadors” out onto the floor in real time to boost the spirits of those who had a bad day [3].

On the one hand, then, identification apparatuses have become ever more pervasively intertwined with the practices of daily life in industrialized societies since the latter half of the nineteenth century; this produced new forms of inclusion and exclusion of “exceptional” subjects within various institutional regimes. On the other hand, just as the technical and semiotic procedures associated with verifying identity were proliferating and becoming ever harder to evade, modern and postmodern thinkers were deeply questioning what, exactly, could possibly be identified by such procedures – and why identity had become such a prominent limiting condition in disciplinary societies. James Joyce’s character Stephen Dedalus marvels at the lack of cellular consistency in the body over a lifetime. While an identifying trait, such as a mole on the right breast, persists, the cells of which it is made regenerate repeatedly. (“Five months. Molecules all change. I am other I now.” [4]) How, then, can debts and deeds persist, if the identificatory traits to which they are indexed are intangibly inscribed in an ever-changing substrate of cellular material?

In the mid-twentieth century, Foucault and Barthes deeply questioned the limitations identity imposed on reading and interpretation. Why, for instance, need authorship play such a prominent role in limiting the possible interpretations of a text? “What difference does it make who is speaking?” [5]

In ’nineties identity discourse, theories of difference became particularly pronounced. Cultural theorists such as Stuart Hall radically questioned essentialist notions of cultural identity, while nonetheless acknowledging the political and discursive efficacy of how identities come to be narrated and understood. Hall and others advocated for a critical understanding of identity that emphasized “not ‘who we are’ or ‘where we came from’, so much as what we might become, how we have been represented and how that bears on how we might represent ourselves. Identities are… constituted within, not outside representation.” [6]

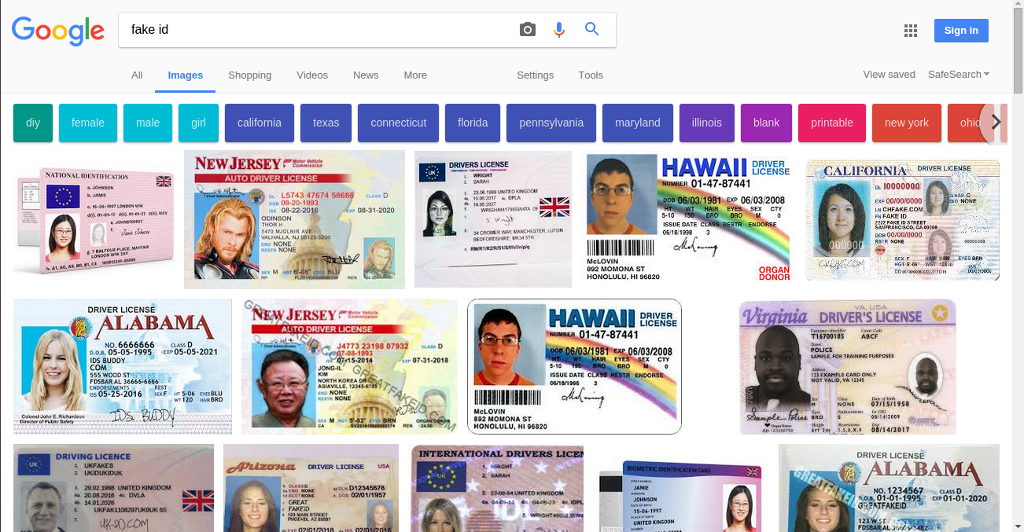

On the one hand – so I have said – myriad technical apparatuses have aimed to ever more reliably capture and verify identity. On the other hand, myriad critical texts have questioned identity’s essentialist underpinnings. But today, these lines have become blurred. The anti-identitarian mood permeates technical landscapes, too – not just theoretical ones. Fake IDs, identity theft, and other obfuscations have grown ever more complex alongside apparatuses for identification; indeed, such fakeries have both emerged in response to, and driven yet further developments in technologies for identity verification as is the case in a Fully-Verified system. The frontiers of identification are ever-changing; each attempt to improve technologies for verifying identity, it seems, eventually provokes the invention of new techniques for evading those verifications.

At the inherently uncertain point of contact between person and online platform, new forms of anti-identifications are practiced – invented or adapted from previous stories. In one bizarre example from 2008, a Craigslist advert posted in Monroe, Washington requested 15-20 men for a bit of well-paid maintenance work. The men were to turn up at 11:15 am in front of the Bank of America, wearing dark blue shirts, a yellow vest, safety goggles and surgical masks. As it turned out, there was no work to be had; instead, the men had been summoned to acts as decoys for a robbery – a squid-ink trail of similarity to help the thief escape. The idea, though inventive, wasn’t entirely original; it was described by police as a possible copycat of the plot in the film The Thomas Crown Affair (1999) [7.

Today, the anti-identitarian mood has spread far beyond small-scale manoeuvers like this. Multiple large-scale data breaches – such as the recent Equifax breach, which compromised the data of over 145 million customers [8] – have put a cloud over the veracity of millions of people’s online identities. The anti-identitarian mood becomes broad, pervasive, and generalized in data-rich, security-compromised environments. It becomes a kind of weather – a storm of mistrust that gathers and subsides on the level of infrastructures and populations.

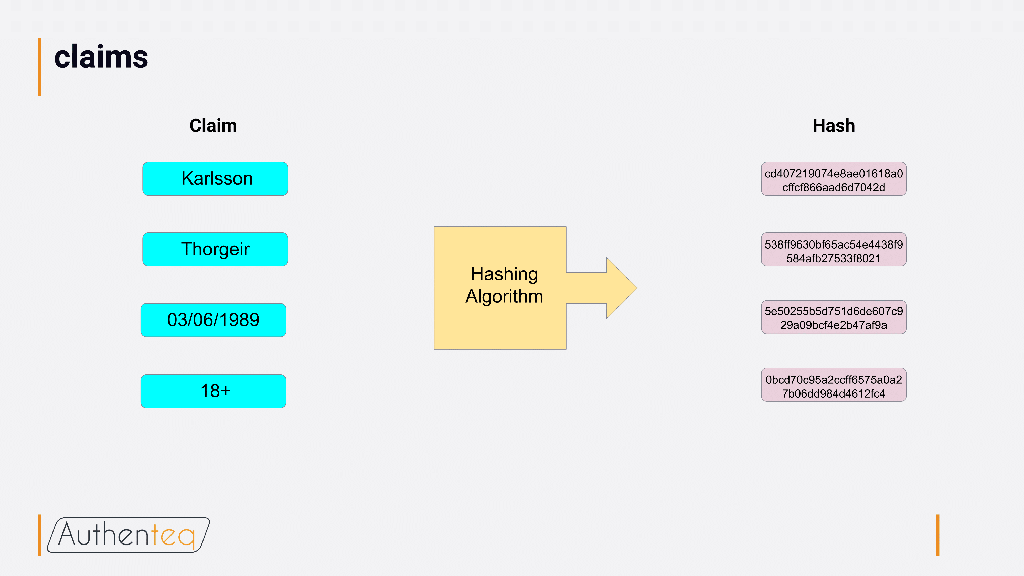

Such are some of the complexities that the DAOWO speakers had to contend with. At the Goethe Institute, we thought through some of the ways in which identities are being newly constituted within representation – ways that might, indeed, answer to the technical and philosophical problems associated with identification. Backend developer Thor Karlsson led us through his company Authenteq’s quest to provide more reliable online identity verification. Citing the ease with which online credit card transactions can be hacked, and with which fake accounts proliferate, Karlsson described Authenteq’s improved ID verification process – a digital biometric passport, using blockchain as its technical basis. Users upload a selfie, which is then analysed to ensure that it is a live image – not a photograph of a photograph, for instance. They also upload their passport. Authenteq record their verification, and return proof of identity to users, on the BigChainDB blockchain.

A hashing algorithm ensures that users can be reliably identified, without a company having to store any personal information about them. Authenteq aims to support both identity claim verifications and KYC (Know Your Customer) implementations, allowing sites to get the information they need about their users (for instance, that they are over 18 for adults-only sites) without collecting or storing any other information about them. Given how much the spate of recent large-scale data breaches has brought the storage of personal data into question, Authenteq’s use of blockchain to circumvent the need to store personal data promises a more secure route to verification without revealing too much of personal identity.

Nonetheless, while Karlsson and Authenteq were optimistic that they can make meaningful improvements in online identification processes, other provocations focused on the potential problems associated with such attempts at identification – on the protological level, on the level of valuation, and on the level of behaviour-as-protocol. Ramon Amaro delivered an insightful critique of blockchain and the problem of protological control. There is no such thing as raw data – inputs are always inflected by social processes. Further, the blockchain protocol relies heavily on consensus (with more focus on consensus than on what, exactly, is being agreed upon) – which reflects a need to protect assets (including identity) and oust enemies that is, ultimately, a capitalist one. Given this, how can identity manoeuver within the blockchain protocol, without always already being part of a system that is based on producing inclusions and exclusions – drawing lines between those who can and cannot participate?

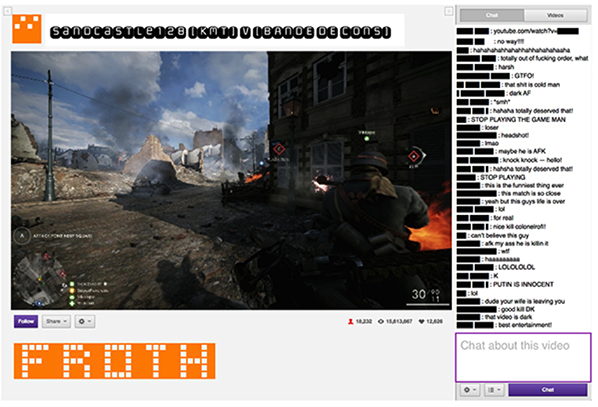

My own contribution focused on systemic uncertainty in the spheres of personal valuation, looking at online reputation. In a world in which online rankings and ratings pervade, it seems that there is a positivist drive to quantify online users’ reputations. Yet such apparent certainty can have unexpected effects, producing overall systemic volatility. At the forefront of what I call “reputation warfare,” strategists such as Steve Bannon invent new ways to see systemic reputational volatility as a source of value itself, producing options for the politicians they represent to capitalize on the reputational violence produced on sites like 4chan and 8chan.

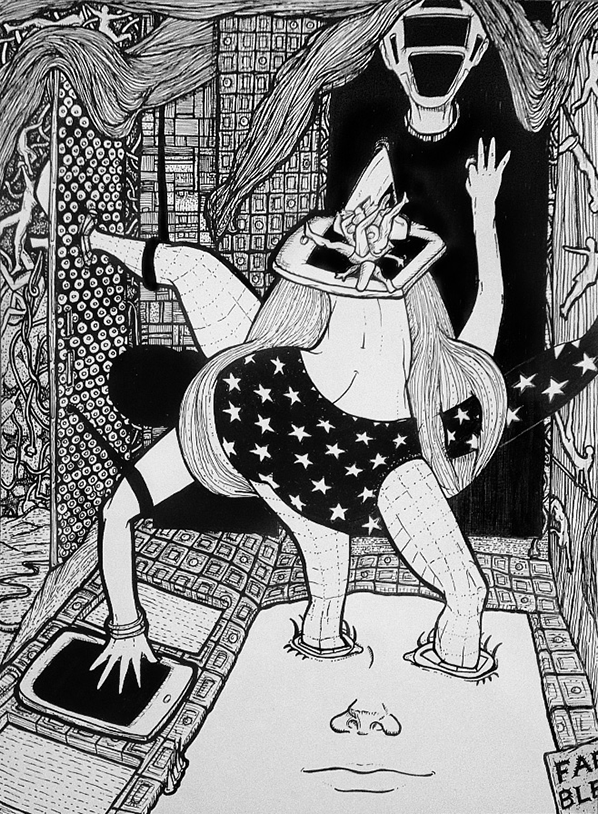

While these contributions reflected on some of the critical problems associated with pinning down identity’s value, some of the artists’ contributions for the day focused on the ludic aspects of identity play. Ed Fornieles’ contribution focused on the importance of role play as a practice of assuming alternate identities. In his work, this involves thinking of identity as systemic, not individual – and considering how it might be hacked. In many of Fornieles’ works, this involves focusing attention on the relation between identity and the platforms on which they are played out. Behaviour becomes a kind of protocol; role play becomes a reflection on strands of behaviour as protocol.

We ended the day with a screening and discussion of My Name is Janez Janša (2012), a film by three artists who, in 2007, collectively changed their names to Janez Janša, to match that of the current president of Slovenia. The film, an extended meditation on the erosion of the proper name as an identifier, catalogued many instances of ambiguity in proper names – from the unintended (an area of Venice in which huge numbers of families share the same last name) to the intentional (Vaginal Davis on the power of changing names). It also charted reactions to the three artists’ act of changing their name to Janez Janša. What seemed to confound people was not so much that their names had been changed, but rather that the intention of the act remained unclear. In the midst of today’s moods of identification, there are high stakes – and many clear motives – for either obscuring or attempting to pinpoint identity. Given this, the lack of clear motive for identity play seems significant; by not signifying, it holds open a space to rethink the limits of today’s moods of identification.

The DAOWO programme is devised by Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickers in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London, and the State Machines programme. Its title is inspired by a paper written by artist, hacker and writer Rhea Myers called DAOWO – Decentralised Autonomous Organisation With Others

Information wants to be free, and net art is information. Trying to make it harder to copy is like trying to make water less wet. Or perhaps like trying to give it a soul. In “Blockchain Poetics” I described “new kinds of quasi-property” created using the Blockchain as a mis-application of that technology. Ken Wark is similarly unimpressed – “My Collectible Ass“, he complains in e-flux.

The history of Conceptual Art’s dematerialization of the art object shows that the art market loves nothing more than finding ways to make the previously unsaleable into financial assets. As Wark points out, “We tend to think that what is collected is a rare object.” There’s nothing rarer than something that doesn’t actually exist. But the un-ownable and non-or-barely-existent can be represented as property by proxy objects. Financial elsewheres rather than financial futures.

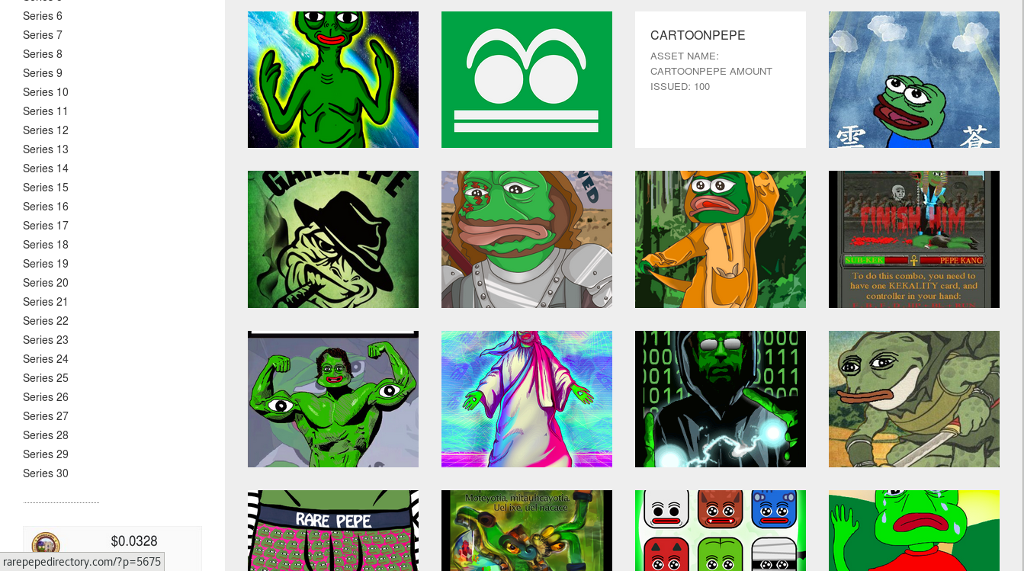

Cryptographic tokens are a generalization of cryptocurrency to represent assets other than money. Such as editions of digital artworks. Wark’s criterion of rarity is reflected in the name of the most successful crypto-token collectibles – “Rare Pepes” are detournements of the “Pepe The Frog” character (previously appropriated by the alt.right) that are sold as CounterParty tokens. CounterParty is a system layered on top of Bitcoin’s blockchain that allows the creation of new tokens with varying properties (different issuance amounts, subdividable or not, locked for further issuance or not, a sub-token of another token) which can then be exchanged and transferred backed by the security of the Bitcoin blockchain. It’s an older system than Ethereum or other platforms that are now used for tokens. It has few major use cases, and Rare Pepes are one of them.

To make a Rare Pepe card you create a CounterParty token with a reference to the image you are using in its metadata, issue as many tokens as you are going to, then lock the token so no more can be issued (making the token “rare”). Rare Pepe quantities, prices and styles vary. There are magazines and virtual galleries devoted to them. There is even a subtoken representing the original physical version of one image (with an edition size of one).

A more singular set of images are the “CryptoPunks” (seen at the top of this page), which exist as an ERC20 token (almost) on the Ethereum blockchain. The “smart contract” that administers the token contains a cryptographic hash of an image of 10,000 bitmapped characters which can be bought and sold using its functions. Like Rare Pepes, the punks have a lighthearted style (they are retro pixellated avatars) and have varying rarity (some features are unique, others appear on dozens of characters) . Unlike Rare Pepes, every punk was created at the start of the project and no more can be added. At the time of writing, punks are available to purchase for 0.12 to 1,010,101,101,110,010,011,000.01 ETH (40.35 to 339,616,193,448,241,111,336,826.06 USD).

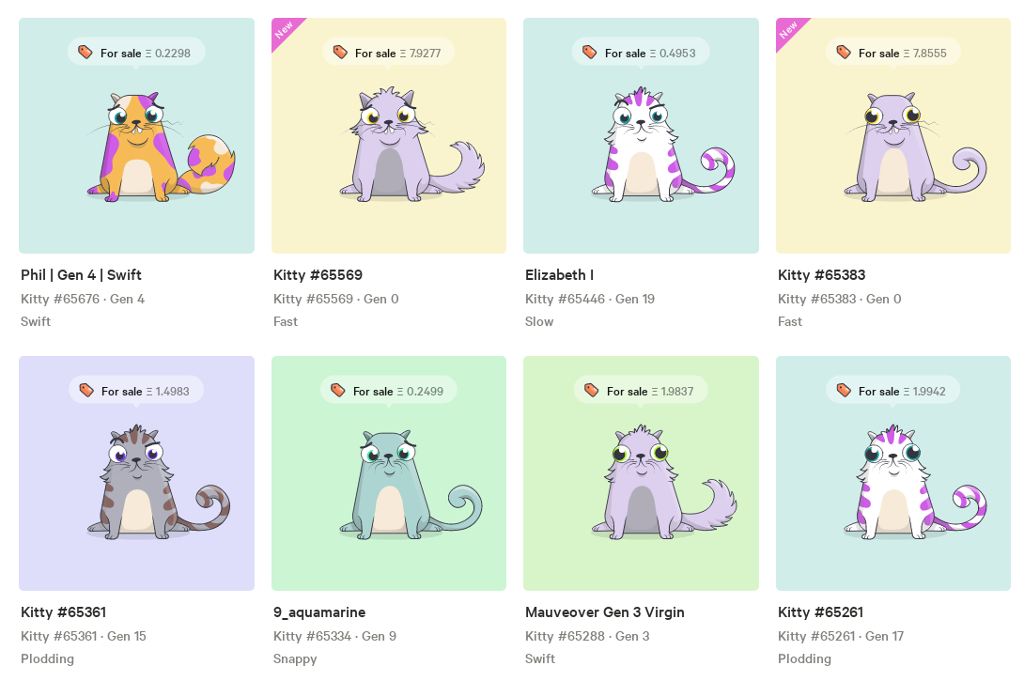

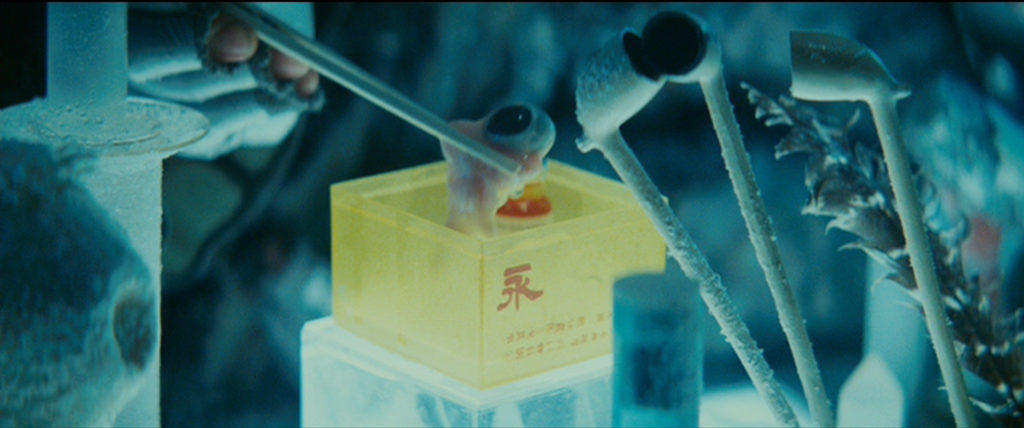

An even more playful approach may be able to take artificially scarce digital collectibles mainstream. CryptoKitties are customized cartoon cats whose appearance is determined by a digital genome (like the old “Cabbage Patch Kids” dolls) that can be interbred to produce more of them (like William Latham’s “Mutator”). At the time of writing they are taking up 13% of the Ethereum network’s capacity, making them the single biggest user of that blockchain, and the most expensive has sold for more than 100,000USD.

Every art is relative to a culture and an economy, whatever its other properties. The ground that tradeable blockchain images are a figure against is a particular moment in the history of cryptocurrency. Trading cards and digital collectibles fit a specific cultural niche, as does their iconography and the socially performative act of dealing in them. Their price may reflect the ability of cryptocurrency early adopters (who in the case of CounterParty and its XCP currency don’t have much else to spend it on) to be more extravagant with their hodlings.

“dada.nyc” follows the tokenized image edition strategy but applies it to popular/illustration art. Again each image is available for a given price in a given edition (for example 0.084 ETH in an edition of 150). The gallery takes a cut, and it takes a cut on profits on the secondary market. It also gives a cut to the artist, simulating Droit de Suite/Artist’s Resale Right. The Resale Right is controversial – it breaks the first sale doctrine and mostly benefits the estates of dead famous artists. But I implemented it as a user-settable property in the Art Market smart contract that I wrote in 2014 as I felt it was worth experimenting with in a voluntary setting.

Monegraph came out while I was working on that project. Like Ascribe it is a serious digital art registry implemented initially using pre-smart-contract technology (NameCoin for Monegraph, Bitcoin for Ascribe). These platforms’ seriousness and phrasing as registries contrasts with the playfulness and explicit tokenizaton of more recent systems. This and the already mentioned possible impacts of the social and economic impact of the increase in value of cryptocurrencies since 2014, along with the increased mainstream awareness of cryptocurrency, may explain the difference in their adoption (or at least their place in the hype cycle).

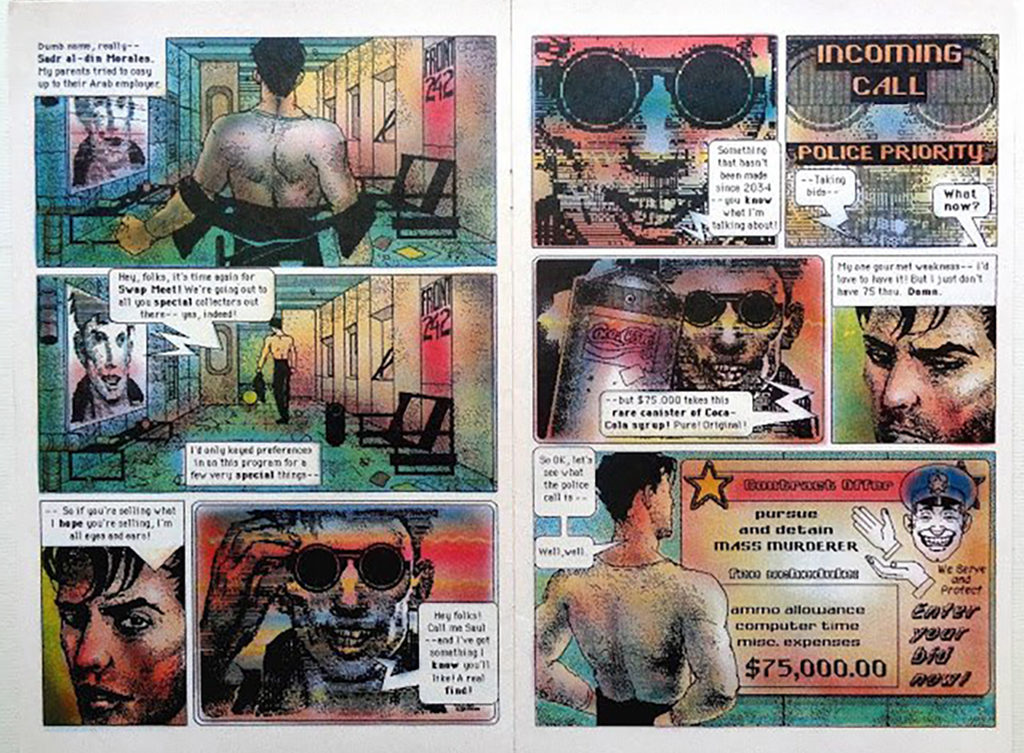

In contrast, Maecenas is a tokenized investment fund for physical fine art. It operates in part like the scene in William Gibson’s “Count Zero” (1986) in which Marly, one of the protagonists, reflects on how art in the mid-21st century is bought and sold as “points” in the work of a particular artist that represent shares in the value of the “originals” which are stored unseen in a vault. To quote their web site, “investors speculate via synthetic exposure: James is a Modern Art collector who needs to finance the purchase of a new Jeff Koons sculpture worth $120k. Instead of selling items from his collection, or getting an expensive loan, James get the required funding by listing in Maecenas 20% of one of his flagship pieces of art. Access to Maecenas is via an ERC20 token named (ART)” that Maecenas claim will improve access, transparency and fairness in the art market.

Propertization, fractionalization and financialization via proxy tokens (we cannot “own” allographic digital images, or own part of autographic paintings without dismembering them, but we can own tokens that we agree to pretend represent these things) promise to support art production using the economic accident of the value of cryptocurrency going to the moon. Quasiproperty without attempts at the costly fantasy of imposing access control via DRM is a form of, or a variation on the idea of, patronage. I feel this complex of ideas should be more useful to critics of the commodity form and capitalism than it has generally been treated as so far. If we still wish to take the opposite tack this leads us to the gift economy or the commons. Copyright is the default state for most art when it is created and is being increasingly restrictively enforced on the net. Opposing it passively or actively through alternative copyright licensing can perform a critique of this and keep space open for alternatives. These strategies needn’t exclude each other though.

If you are familiar with DAOs, you can see how a system similar to these could become a self-supporting, self-curating DAO. Plantoid is an example of a singular artwork (or family of artworks) produced and exhibited in such a way. Imagine it generalized to a gallery or a participatory art show, a DAO that lets you do art with others, a DAOWO.

These technologies can provide objects for critical exploration that evoke wider contemporary themes. They can function as tools and resources for the creation of art and its social collectivities focussing on these and other themes. Within the existing economy they can provide ways of supporting the arts (as many of the projects mentioned above claim to), which should neither be dismissed reflexively nor accepted without irony. Or they can be used to try to bootstrap a different context entirely, even if only briefly or in the imagination. The various modes of tokenization represent potential ways of making a living in, critiquing, or even transforming the artworld in an era of the continuing expansion of the sphere of private property and financialization under technocapital.

It was not the cyberpunk universe you were looking for.

Our nostalgia centres were lit up with a cut from a flying car to a full screen eyeball staring across the opening scene, synchronized on the script and musical score of its 20th century precursors’ timing. From there, audiences of the Blade Runner sequel were dropped into a pale California wasteland blanketed with conglomerate agricultural biofarms, an antithesis to cyberpunk’s damp, urban hybridity. The green, utopic space beyond the city– only glimpsed at the end of the 1982 original theatrical release and removed entirely in the director’s cut– was where we started from in Blade Runner 2049, and (surprise) there’s nothing but the dystopia of the anthropocene to look forward to there either.

Times change.

The recently post-industrial, 20th century cyberpunk rebellion of bodily sensuality: the noir lighting, the baroque candelabras burning, the lingering fingers stroking out haunting piano music; these were relics now, hinted at, ghosts of a genre in its past moment. Even the endless rain characteristic of the cyberpunk genre was repeatedly replaced with snow in Blade Runner 2049. A borrowed soundtrack teasing the familiar bridge to a heroic death scene came without poetic dialogue or even a witness. Rogue replicants were not criminals, but escaping criminality. Even memories were no longer stolen in this world, but legally manufactured, a convention stripping the typical cybernetic plot of bioharvesting found in cyberpunk down to a more contemporary, bioengineered ethics of classed and raced co-humanity if ever there was one. No, this ethical failure was smoother, blended into liberal values and legal structures, more sanctioned somehow.

The 80s cyberlibertarian world of the white lone wolf, struggling for autonomy in a hybrid, post-globalized world of orientalist economic takeover, had passed by in the great data “black out” of 2020 apparently, and Denis Villeneuve didn’t care about your need for consistent genre romance. Sort of. Rather, the director brought the audience’s need for Blade Runner nostalgia in and out of the sequel like a tool, cuing our attention to wait for it, partially rewarding us with a sensory, semi-nostalgic moment, only to glitch before nostalgic completion. Again and again, it was invitation and estrangement from our own expectations. Blade Runner 2049 was a highly self-aware remix of its own postmodern references and refusals in a predetermined world.

Perhaps a hybridity across two cyberpunks of historical time and cultural change was apropos. Ridley Scott’s genre critique of the corrupt corporation had evolved since its 20th century take in the Alien franchise, expanding to consciously address our own implication in the techno-dystopian social narrative. It turns out that we are no longer universally laboring blue collar victims in the secretive horrors of impending biopolitical technocracy. Rather, we are eager and satiated participants in its isolating ubiquity; high tech consumers implicated in all of the attendant social stratification, inequality, and suffering that its warm glow of access masks and accelerates, from facilitated gentrification and casualized labor, to the toxic, extra-legal wastelands of dead electronics processing.

Disruptive innovation has predominantly benefitted the 21th century, western, science fiction audience. Our classic cyberpunk desire for the vindication of the social outlier– the androgynous Sigourney Weaver in a corporate-threatened future of full equality and bodily autonomy, or the replicant who can reclaim a subjectivity beyond his or her social paradigms and slave programming– has since been turned on its anti-establishment head. Scott’s film Covenant saw this come to fruition when the Menippean Anti-hero, Bakhtin’s rebellious, paradigm-questioning literary figure cloaked in the absurd eloquence of language, is fledged into a full sociopath. We saw this in the philosophical and intellectual character of David and his calculated experiments to replace the evolutionarily inferior human species. If Menippean satire is “a genre for serious people who see serious trouble” (Howard Weinbrot), than what is this?

By Covenant, our anti-hero no longer presented the humanistic redemption narrative of the Menippean Nexus 6 leader, Roy Batty, in the original Blade Runner. Instead, Covenant gave its inverse: a regressed society being shown the mainstream values it has come to love and endorse in a world of neoliberal anti-establishment leadership. So much for the underground resistance crouching in the street garbage. The 21st century universe of cyberpunk has been one of well-mannered disruptive innovators of the species, philosophically visionary proponents of transformative wealth models built on slave bodies, and the “technê-Zen” veneered (R. John Williams) institutionalization and naturalization of technological sociopathy. Here is a social darwinist instrumentalism for our post-human age of market-driven measures of social success and impending climate change. In this universe, androids can be humanist while humans can be androids in an inhuman system, conveying either ‘progress’ by any means necessary or a losing sense of civilizational duty. Whose side, Covenant asked of us, before its devastatingly feel-bad ending, were you hoping would win anyway?

David, it turns out, was the only anti-hero we deserved now.

Denis Villeneuve’s sequel fits surprisingly in this updated cyberpunk universe. Like Walter in Covenant, the replicant hero who becomes Joe in Blade Runner 2049 (in contrast to Roy Batty) clearly lacks the eloquent language and especially satire of the subversive, Menippean Anti-hero character. Surprisingly, we find his strain of articulate stream-of-conscious in the tech empire guru played by Jared Leto, drained of all the feeling and trickster-like ability of Roy Batty. Joe, however (like Walter), is simple and humble in his speech, seemingly able to feel but dying suggestively in silence off screen. Robbed of the poetic dialogue expected of the death scene, only a soundtrack bite nostalgic of Roy Batty’s final scene signals a death of redemption for Joe in Blade Runner 2049. Yet the unsentimentally raw, blank slate of Joe’s expression asks of his audience: What do we see through his eyes? What language could possibly be used here to convey the gravity of a moment when power so regularly denies and manipulates the language of our experiences? In this silence, we are perhaps left to only wonder what we would be feeling.

What if it had ended differently? Would Roy Batty’s eloquent speech achieve the same humanizing disjuncture today, or does it really belong now to Niander Wallace, our tech monopoly visionary of the neoliberal age, emptied of any contradiction with the smooth flow of progress rhetoric and sociopathic public morality? Niander Wallace as foil who cannot stop talking makes Joe’s uncharacteristic silence all the more uncanny. According to Jonathan Auerbach, the uncanny involves a “trespassing or boundary crossing, where inside and outside grow confused… reveal(ing) dark secrets hidden within.” Auerbach is talking about film noir here– a highly unsettling sensory genre metabolized into the late Cold War aesthetics of the Blade Runner world. But perhaps we can relate this psychic role of the filmic uncanny to other hybridities explored through expressionist media, where the formal manipulations of sight and sound once conveyed the uneasy clashing of two worlds affectively.

Is Villeneuve’s silent denial of a hero’s dialogue in a death scene, for a Blade Runner audience, purposely estranging? Does it achieve the same, disorienting “uncanny bodies” (Robert Spadoni) that silent film audiences, unaccustomed to sound in their movies, reported with the introduction of Talkies? Film scholar Shane Denson describes how post-Talkie movies of the Thirties like Frankenstein (1931), were created in a period of transition and between the old and new ontologies of silent and sound film media. Denson argues that such films, working after the initial novelty of Talkie exposition wore off, played affectively with the new hybridity of films formalist storytelling qualities. In doing so, these films drew attention to our participation in media: “sight and sound conspire(d)…to encourage the viewer’s medium sensitivity, to coalesce with the perception of a constructed monster.” And what is a sequel, after all, if not a constructed monster of narrative to become conscious of?

“Questions.”

We live in a time of the seductive post-human technologization and normalization of very inhuman institutions, public policies, and person-like entities whose social impacts are all too often screened over with ‘alternative’ narratives of language. Glitches in this flow of mainstream mediated ways of knowing can be more than anti-nostalgic; they can be disruption to the alt-fact hyperreality in the neoliberal 21st century. Are uncanny bodies of the sensorily unexpected (or, even, dissected) what we have left to successfully slow down and stutter our neoliberal ubiquity for hearing chasm-filling speech? Can such estrangements allow us the conscious relationality to once again actually hear and see how we are hearing and seeing each other?

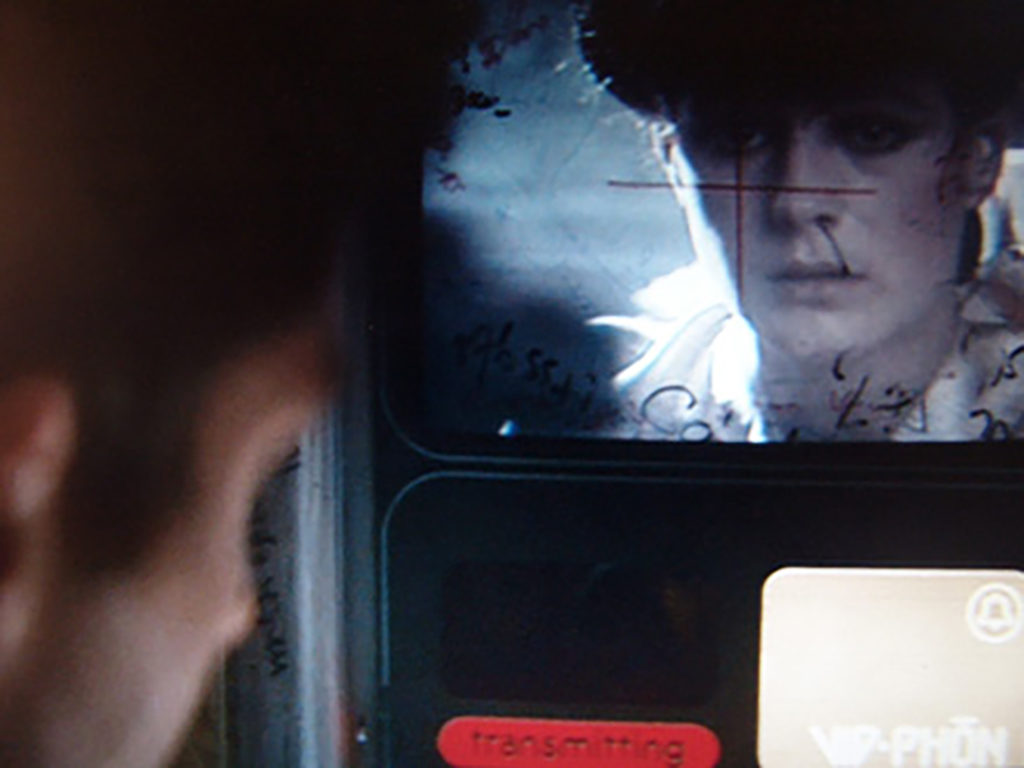

It is convenient to note here that the technological imaginary of the first Blade Runner movie refused ubiquitous surveillance. Blade Runner 2019 even refused a conception of the personal communication device so often credited with fracturing collective sociality in both sci-fi and reality. Decker, for example, calls Rachel from a public videophone in a bar. Whether human or replicant, technological worlding of the original Blade Runner insists on the communications scale of face-to-face human relationality. By the end of Blade Runner 2049 this same scale of technological imaginary in the original film returns. It is the death of one body, the replicant called “Luv”, that seems to end the limitless reach of panopticon technology that helps advance the plot.

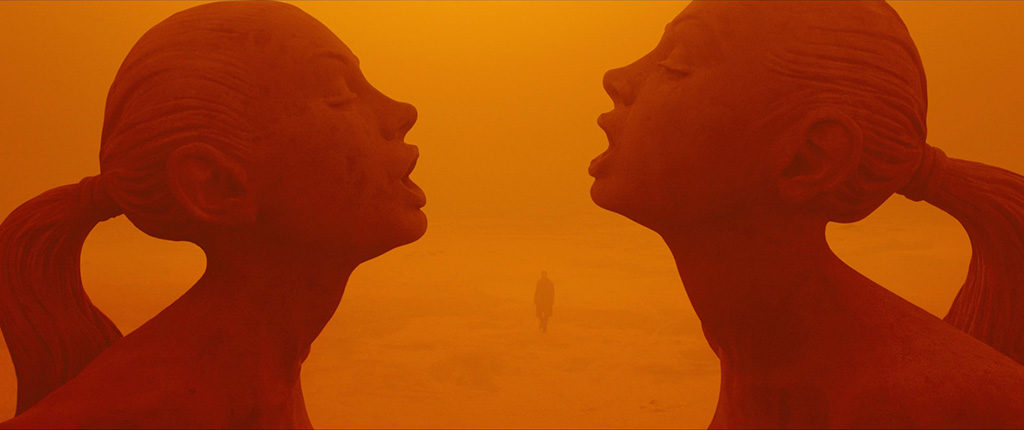

Some kinds of love can destroy. Scene from Blade Runner 2049

This act leaves the future of Blade Runner’s Earth yet again to the relations between two, individual physical bodies. With the 1% most likely afloat in the outer world colonies, we might assume this means that it’s up to Us to cross the interface of hyberbaric differences. At a time when love has become perverted with neoliberal logic– instrumental, utilitarian, stripped of its greater sense of equality or duty– it seems that Villeneuve graciously gives us an answer here, if not a fantasy to hold on to. Perhaps one consistency in the Blade Runner franchise is the argument, like that of Junot Diaz on neocolonial oppression (as if it ever ended) and the uptick of white supremacist domestic terrorism, that it is ultimately intimacy with the Other and rejection of the glorified “lone wolf” mentality that must be revolutionary: “Vulnerability is the precondition to contact.” What if being in our present moment requires the vulnerability of silence?

“Listen:”

Nostalgia has come unstuck in time. In Ghosts of My Life, the late Mark Fisher wrote extensively of the threat of nostalgia in postmodern cultural production. Building on theorists Frederic Jameson and Bifo Berardi to explain the bending of new technologies to recycle comfortable and profitable cultural forms for capitalism, Fisher explains how “…the nostalgia mode subordinated technology to the task of refurbishing the old”, not of specific past styles, or periods, but forms of never-fully-present time asynchronicity. Consider it like another outdated, self-reproducing model, ever expanding all around you to stay relevant. Perhaps you can finally see its now, like a loose eye, engineered, removed from its familiar socket.

Transgressive fiction has this way of making our boundaries visible in the crossing. The reader may resist its dehumanization, suddenly queasy. Barthes once wrote about the surrealist Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye, a modernist novel from the early mid-20th century which indeed involves a plucked eye and its “metaphorical journey” across other eye-like images. An object, he wrote, “can pass from hand to hand… or alternatively it can pass from image to image, in which case its story is that of a migration, the cycle of the avatars it passes through, far removed from its original being, down the path of a particular imagination that distorts but never drops it” (his emphasis). Barthes felt The Story of the Eye was less a novel and more like poetry. Through its avatars and crossing of sensory metaphors, the eye simultaneously “varies and endures.” Consider the following example of crossing sensory metaphors from the Blade Runner sequel: eyes, cells, tears, rain, leaking, bleeding, blinking, seizing, splashing, drowning, watching, “cells”. And what if this thing we now strangely see so differently is neither naturally born nor autonomous, but a constructed thing?

How eerie.

Eerie like the absence of “future shock” in the futuristic. According to Fisher, nostalgia mode production is an aspect of the “cultural logic of late capitalism” that “…disguise(s) the disappearance of the future” and prevents any real possibility of innovative “rupture”. Nostalgia in our entertainment helps stabilize the “cultural deficits” created under globalization, soothing the simultaneous “exhaustion and overstimulation” of instantaneous and transactional relations we can’t seem to deal with. It fills a high-speed chasm of emotion, truth, and meaning. It denies us the “uncanny” recognition of our temporal futurelessness, left teetering on neoliberalism’s precarity of resources “despite all its rhetoric of novelty and innovation…”

Let’s just be honest here: by the time the Coke commercial hologram showed up in Blade Runner 2049, it was a joke on our desire for even nostalgic product placements.

Nothing changes.

Dipping into the media art world at this borderland, theorist and filmmaker Hito Steyerl writes in “A Thing Like You and Me” about the video that David Bowie put out in 1977 for “Heroes”:

He sings about a new brand of hero, just in time for the neoliberal revolution. The hero is dead—long live the hero! Yet Bowie’s hero is no longer a subject, but an object: a thing, an image, a splendid fetish (…) the clip shows Bowie singing to himself from three simultaneous angles, with layering techniques tripling his image; not only has Bowie’s hero been cloned, he has above all become an image that can be reproduced, multiplied, and copied, a riff that travels effortlessly through commercials for almost anything, a fetish that packages Bowie’s glamorous and unfazed postgender look as product. Bowie’s hero is no longer a larger-than life human being… but a shiny package endowed with posthuman beauty: an image and nothing but an image.

What are we to do when no degree of protest or declaration can make an exploited object be seen as a subject? Where is one to find anti-heroism in all of this? Let us be objects of severe agency then. Models that are perhaps transferrable, but unobtainable. One of a kind and replaceable. Constructed yet autonomous.

Perhaps then we can only view these things in suspension: the need and refusal of nostalgia as liberating human process, the uncanny increments of our cultural evolution to product and media-focused estrangement, the will to see one’s own familiar pixels blown wide open. “Digital information is … characterised by transformation, degradation, circulation,” explains Hito Steyerl in an interview in Rhizome, “but also by its surprising ability to mutate and produce unpredictable results. The glitch, the bruise of the image or sound testifies to its being worked with and working; being passed on and circulated, being matter in action.” Futureless. As futureless as staring into a present ruin, expansive but without destination, the destination without purpose.

Apropos, then, how our old and new heroes meet in that ruined casino scene, outcasts of white difference (by the future racialization of the synthetic) in an atemporal Las Vegas, framed by primordial Seven Wonder monuments to the our foundational schisms of misogyny (yes I’m also talking about me).

In this incarnated ruin of our stubbornness for cultural mythologies, I was struck by the brilliance of the fight scene, the director literally exploding our pixel expectations of 20th century nostalgia as soon as Harrison Ford makes his long-awaited appearance. The sonic build-up of Decker’s familiar piano in the distance was dissolved by the strange sound of his disembodied voice un-cueing an upcoming appearance in the scene, his visual reveal in that moment of our auditory let down, confusing: Desire misfiring. The ensuing cyberpunk clash-as-fight-scene of 20th century romantic and 21st century post-romantic dystopic characters corresponds to the casino’s hologram interface of an imagined, mid 21st century entertainment technology; all of the expected glamour and nostalgia is allowed to barely seduce us before sputtering and malfunctioning as filmic metascene. Within the plot, these post-apocalyptic hollywood holograms are also a sign of the future sentience to come in the character of Joe’s AI wife, Joi, and a warning that all technology rebels and mutates from initial human intentions, no matter how superficial the design intentions.

My interpretation of this violent casino stage scene in light of a more recent American mass shooting of an ever-expanding, historically singular, and self-containing statistic of “largest ever” is not lost on me. Neither is the choice of mid 20th century entertainers like Elvis and Monroe who notoriously performed like automatons with post-human qualities, their movements in time-space of perfect bodies turning on the master clockwork of a still-industrializing cultural machine before blowing apart, fragmenting. Their avatars echo of consumer-creator bodies in our postindustrial world of 2.0, gig labor, automated economic transactions feigning meritocracy, and a model of precarity demanding the inhuman perfection of individual responsibility for every movement which can shudder, glitch, and explode on other people all too frequently.

This failure is that of speculated, plotted, rationalized, and technologized courses whose error cannot be properly imagined, only realized and refused in the ruins of a short-sighted economic-cultural imaginary. Our looking back on dystopia hints at our present expectations only.

“Irreversability.”

“It’s difficult for someone of my generation to break free of the intellectual automatism of the dialectical happy ending”, writes Bifo Berardi about irreversability. He compares this “taboo” concept to the “silent” apocalypses of our endless growth mentality, like Fukushima, corporate disaster unaccountability, socialized scarcity adjustments, and our silence on fellow human suffering. His book, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, speculates a “process of subjectivization” for the return of solidarity to a “social body”. This is the social body being culturally reprogrammed away under our collectively isolated movements of relentless market-driven consumption and precarity (individualist and systemic, like the fascist choreography of Kracauer’s Mass Ornament, or the Las Vegas showgirl spectacle). We might consider these grinding automaton gears of consumption and precarity the logics of late-terminal capitalism for clarity, it’s refusal a glitch in our clockwork performance. What is one to do for a postmodern exit other than to shudder, to write off the page? Ultimately, Berardi’s book leaves us more with a hope for our relational redemption from neoliberal culture through “sensibility” than it does with answers.

Blade Runner 2049 may not have been the sequel people wanted, but its confrontations with its own expectations provided a little of the things we need: a vision of the finite and anthropocene, a postmodern exit to the endless technologized avatars of getting what we think we want, our profound silence of the awful price. The film’s self-aware, nostalgic ruin leaves us with a little less of the typical sequel’s fourth wall, and an identification with its lonely bodies, caught in action between clockwork cultural predictability and its refusal. These bodies may or may not have the capacity for real love, but they are vulnerable at least to a larger sense of duty that Humanism, in all its universalizing failures, really needs. In this hybrid space of ontological awareness of the facets of knowing, experience and process, Blade Runner 2049’s success was inbetween all the things it could never definitively be. We too might realize that ‘doomed to fail’ may only be our insistence on choosing from a predetermined relational binary.

A distant song floats into the scene.

…“Though nothing, nothing will keep us together…”

When I saw Blade Runner 2049, in was at one of the remaining four hundred or so drive-in movie theaters left in the United States. I went back in memory to my kindling college interest in what I study and consider Avantpop, surveying the changes, considering its meaning and meaningless in my social development as a scholar: working class, woman, white, heterosexual; accepted and refused and abused entrances. The sequel came less than thirty years later in the revolution of a world for me, but I travelled farther to get there, out to a dark semi-rural drive-in beyond the city, and a memory of popping in a VHS tape almost 20 years ago simultaneously. I time-traveled mass media ontologies. I posted an instagram picture. It was semi-romantic nostalgia for me. But I still see that there is only now to change what we’re doing. And it is terrifying.

It’s quite an ending, to just die in silence, isn’t it?

But the fourth wall was always part of this, you know.

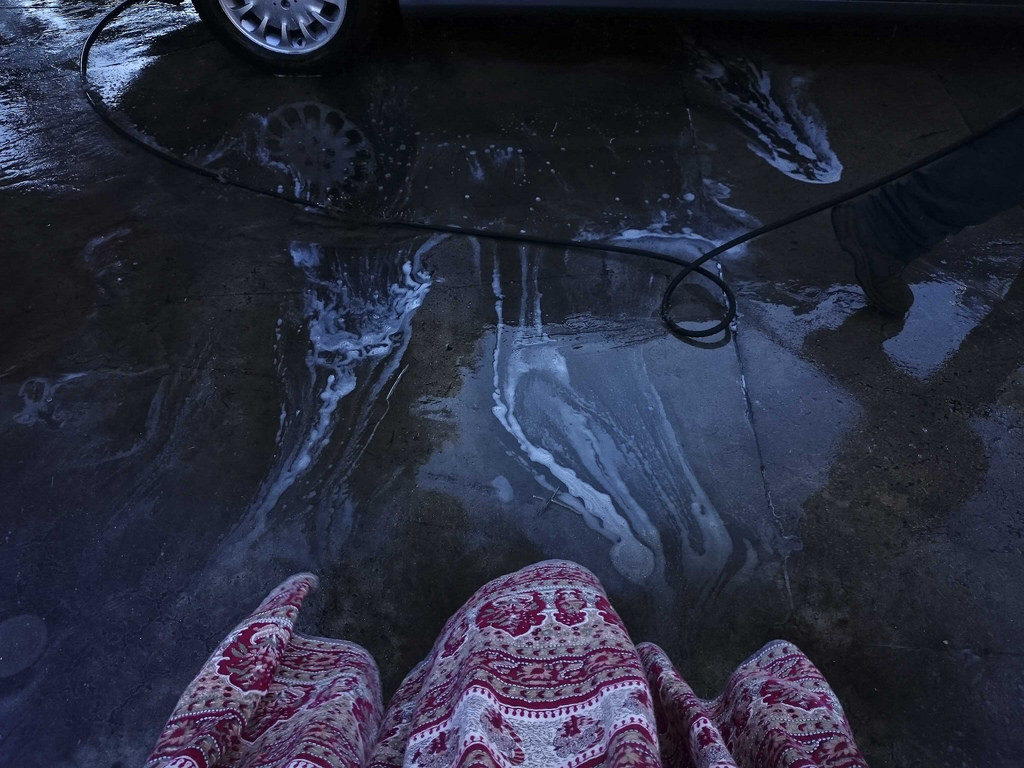

This is the third of three pieces on people who are posting work to the photography sharing site Flickr [1].

In this final article I look at the work of Karin Rudolph

. Rudolph is a Belgian photographer, currently living in Athens, where she works as a wedding and event photographer and raises two teenage sons. In addition to her work for pay she makes an ongoing series of ‘personal’ images which she regularly posts to the photo sharing site Flickr.

I ask her to send me some images from a wedding job and she does.

It is a job she is clearly good at—everything is beautifully shot, nicely framed, sharply in focus (when sharp focus might be thought necessary), but there is that extra something that comes with a good portrait photographer, which I can only describe as fellow feeling. A fellow feeling which elicits transparency and a willingness to risk vulnerability from the subject. I’ve never met Rudolph but it’s clear that her personality, her way of being, is a player here.

There’s also a sharp curiosity at work—a hunger for the way the world looks and with Rudolph this seems to become attached to particular objects, creatures (some human, some not) and roles. There was a dog at the wedding in the images she sent me. The wedding took place outdoors and the clearly much loved animal figures in a number of the shots. It’s as if at one point R becomes fascinated by it and we get shots where the all humans are cropped (in the shooting; she doesn’t crop after the fact) down to the waist and the dog becomes central (although a small child has a supporting role here too since he necessarily evades the crop/frame wholesale). We get a dog narrative. Then a bouquet catches her eye and we get a bouquet narrative, the wedding filtered through a non-human being or an object. Motion—a sense of the moment before and the moment after being necessary, if hidden, components of this still image—is a key underpinning of so many of these images, particularly in relation to these micro-narratives.

In a photographer less manifestly gripped by the facts of our fragile human being and ways in the world one might call some of her approaches formalist. It is certainly true that rhyme, echo, geometry, continuities and disruptions of line, shape and colour play a highly significant role in the structuring of her images but one of the driving forces of R’s work is that it constantly moves to dissolve any artificial divide between content and form. Yes, her eyes seek pattern; yes, this or that organising device might order an image but this never obscures our awareness of the facts, feelings and relationships portrayed or implicit there. Also—we humans are formalists, aren’t we? We’re pattern seekers. We play. Were you never fascinated as a child by mirrors, by the world turned upside down by hanging from your legs or by the cropping or heightening, or focus) achieved by looking through the cracks in your fingers? Of course you were. As we grow we perceive the whole world through a complex dialectic of what is presented to our senses on the one hand and our burgeoning sorting and structuring principles on the other. We are of necessity creatures of content and form together and one surmises that this is what makes us creatures of art too.

I’d been writing and thinking about this piece for a few months, on and off, and I’d got to a second or third draft when it hit me with a thud, a jolt, that hardly any of the recent images have titles.

The fact had just sailed under my radar, curiously, since I’ve argued and will again, that insofar as we can talk about meaning in a photo (or any visual artwork) this possibility lies in a network of references and comparisons which ineluctably involves talk, writing or both. Language. Further, that visual art is best seen as something humans do (emphasis on both words) than as the usual set of isolable ‘in and of themselves’ objects (which isolation is a fiction, at best an analytical convenience). And then it struck me ( I was being struck a lot that day) that there is something about these images that fights back against language—they’re often cross genre and resist categorisation and there’s a sense in which the easiest approach to what’s in them is simply to list it, and finally to say that this image had these things in it under this kind of light from that angle but, of course, this is far from satisfactory and at root there is something far transcending taxonomy or description going on. But –dammit! –I can’t help feeling it is as if the images (placed as they are in the sequence formed by Flickr) are calling out, hailing each other. I don’t know why, but forced rhubarb, a most unlikely image, is the one which springs to mind and persists, as if the absence of the immediately adjacent language of a title somehow forces the set of glorious but hitherto mute images to invent speech.

Anyone who has ever taken an un-posed image of a human being on a fast shutter speed will be cautious about ascribing emotions or characteristics to the subject on the basis of what is revealed. As in so many other ways, the very small, the very distant or unreachable, animal locomotion, the photograph reveals things beyond our normal ability to see or grasp them. One of these things is the curious plasticity of the human expression and how in our interactions we read this in sequence, in time, together with a host of other clues, aural and visual, to make sense of what is going on, to try to understand both what a person is doing and to surmise what they might be feeling . (Of course the opposite of this, the posed image, brings its own problems too.)

When we think hard and soberly we cannot but be convinced that the photograph alone, an impossibly small fragment of time, does not allow us enough evidence, that it is somehow unanchored in the world.

And yet, the desire to draw conclusions, to make comment, is certainly strong in us and each photographic image of a person, especially the striking and affecting ones, comes with a very strong sense that we are able to do so.

What can we actually say about the still photographic portrait, both in general and in particular cases?

One thing we might say is that the single image’s apparently complete account of a human being, based upon a fleeting expression (and perhaps the fleeting expressions in response of others and maybe also the presence of contextualising objects or other clues) suggests at best, a class of possibilities. This single image evokes a range of other possible images and moments in the world at least one of which must correspond to our strong intuitions about it. So even if we were able to establish the facts of the matter in this particular case and it made a lie of our emotional response , nevertheless that response represents a truth and somewhere, perhaps quite often, in the world, situations occur, have occurred, will occur, which correspond to this truth.

And it seems to me that it is this instinct for general human truth, allied to the particularity of light, line, composition, of other things depicted, which manifests in the eye-and-heart-catching-ness of the resulting final image.

A strong way of putting it would be that any portrait is just as much a work of fiction as a novel but that as we would not wish to deny something called ‘truth’ in the novel ( you might—I see no point to the thing otherwise) in the portrait we work our way back to truth.

And at least for me it is the photographer’s—and here, now ‘the photographer’s’ means R’s—capacity for empathy, for narrative, for understanding of the world and the wonder and the oddness of its inhabitants that makes her such a good portraitist (and let’s not forget, too, simply having done the thing a lot —this is often underrated nowadays.)

Do I know whether the Orthodox priest at the wedding table was a kind man? No. I don’t. I cannot. Is kindness manifest in the photo, is the possibility of kindness in the world reasonably asserted in it? Do I know more about kindness thereby? Absolutely.

There’s a black and white image, taken, I think, at the place where her teenage sons practice their footballing skills which feels like a short story or perhaps a collection of short stories, each cued by the various human presences which form at one and the same time a large (in how they capture our attention) and a small (in how much actual area of the image they occupy) part of the entire image.

It also has a most clearly defined geometry—three strips, the topmost being the practice field itself, the middle appearing to be a road like depression running between the photographer and this field and the lowest a pavement of some sort on the other side of that ‘road’. The almost bizarrely long evening shadows of R and a companion (and the horizontal distance between shadows is nicely ambiguous on the exact relationship between those shadowed) stretch forward into the image. The vertical grid adjacent to them, with a gap in the centre picked out in shadow too, suggests they are standing at a pedestrian gate to the place. I imagine the figure at the viewer’s right is R as the arms appear to be raised in a photo taking action.

(The image thumbs its nose at genre—it is oblique self-portrait, landscape, social history, portrait and exploration of geometry and structure all at the same time.)

Shadows aside, the figures which catch my eye (what about you, so much to choose from or are you constrained in a similar way to me by something in the way the image is structured?) are the short stocky man in motion, walking away from us at the image’s far right top strip foreground. There’s a delicious swagger and confident openness about him.

Has he passed through the gate where R stands? Did he greet her?

The second key (perhaps because nearest?) figure is the young man, top strip, viewer’s far left, again in movement, this time almost certainly certainly sports related. Is he pursuing a stray ball? Running to greet a friend? Engaged in some sort of running warm up/exercise? As we strain to see, our relationship to the image’s scale shifts and we begin to realise just how many other figures he opens up to us—there are at least six either standing or seated in those little sheds at the field’s side between him and the left edge of the nearest goal net—each an enigma of a small but definite kind—and when we move rightwards from them we realise (and we have to move closer in, look differently, at the image to see this) just how many people there are in some sort of action here. As we move out again we are stuck by the contrast between the contemplative calm of the giant shadows and the anthill busyness of the young men. And here’s another thing. This is such a male photo. (With the exception of the photographer and I think it’s only because I know she is female that I read her as such. Then even as I write this I notice the slight head-cocked-to-one-side quality of aficionado-like attention in the head of the left shadow—and why do I think that might clue maleness? What does that say about me?) Oh! Layers and layers of fact, of presence, of things to enumerate and puzzle over. So much! And this before we take the thing as a totality—geometry, inhabitants, shadows, activity, motivation, time of day, distant trees, weeds and barren ground, a sky whose colour we can only guess from the fact we know there is evening sun. And that totality is the hardest thing to compass in any way other than an intake of breath or shiver down the spine. Enumerating the contents helps (although it’s not essential to the immediate affective apprehension of the whole—that just happens) but it’s the inexplicable (not a value judgement—literally inexplicable—simply, ‘This is what R did’) decision to frame those contents in that way—the bit of the process which defies words—that makes this and so many other pieces by her so powerful.

5.

A ravenous eye.

She has a ravenous eye, constantly tracking the scene in front of her and hungry for detail. This hunger does not distinguish between content and form. Whatever is human, whatever stirs affect or curiosity—whether pattern, rhyme or echo, or ethics, or suggested human warmth or frailty, this is swallowed up and processed by heart and mind in turn

The resulting images bear the strong feel of certain, almost objective, structuring principles—that following of object or creature within a scene, the use of rhyme and echo. Two further categories are geometry and colour (and nothing here is pure, there are no essences, sometimes blocks of colour impose an extra, parallel geometry upon a scene whose first order sense—whether it be human beings in action or traces of interpretable human activity; buildings, signs, the street —apparently lies elsewhere.) The key thing about all these structuring principles is that they are found, excavated, discovered, seen—not made. They happen in parallel with, arise out of the actions and feelings of, human beings in this world, the only one we have.

Because she is someone who has lived, fully, in that world, for a fair time, because her hunger extends beyond the visual (she always has a book on the go and the range of these is impressive), because she has a number of languages and is at home in at least three cultures, she makes images which are connected and re-connected by hundreds of threads to things we ourselves might have read and thought or experienced and talked about. Further, it is impossible to imagine that the fact she is a woman living in a country not of her birth, where she has learned a different script, different ways of talking and being, where she works in part as an image maker for hire and constantly both connects and holds separate that work for pay from own ‘own’ work, at the same time as raising children by herself, that these facts are not also somehow foundational.

For a long time I have struggled with how to attach the word meaning to image. It is too easily and glibly used. An image never ‘means’ a single thing (unless it is the poorest of images and even then the human capacity for/delight in ambiguity sets to work to disrupt this) What is evident in Rudolph’s work is networks of evoked meaning, memories, feelings.