“None but those who have experienced them can conceive of the enticements of science.” Mary Shelley, Frankenstein.

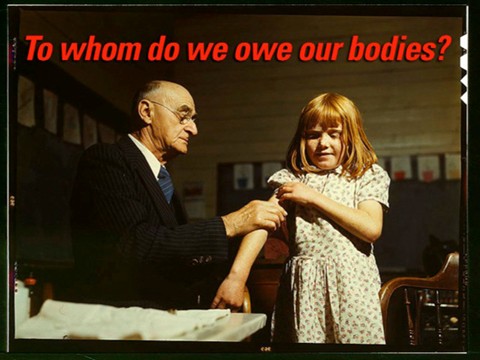

Rachel Falconer writes about the cyberfeminist art collective subRosa, a group using science, technology, and social activism to explore and critique the political traction of information and bio technologies on women’s bodies, lives and work.

Following a recent interview with the founding members of the collective, Hyla Willis and Faith Wilding, this article presents subRosa’s trans-disciplinary, performative practice and questions what it means to claim a feminist position in the mutating economies of biotechnology and techno-science.

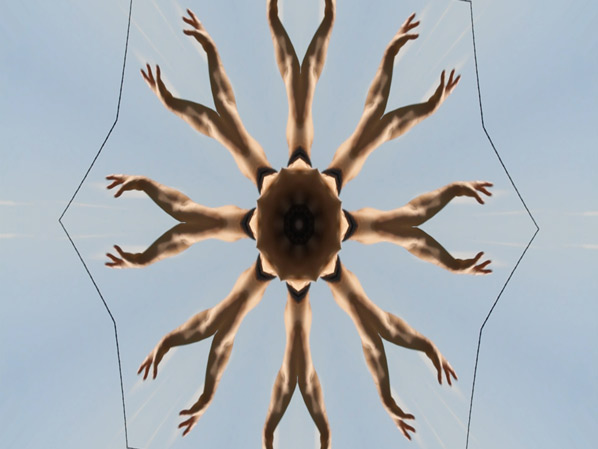

The technological redesigning and reconfiguration of bodies and environments, enacted through the economies of the biotech industry, is an emerging feature of contemporary life. As these new ‘bits of life’ enter the biotech network, there is a slippage in our mental model of what constitutes the body, and more specifically, ‘life’ itself. As radically new biological entities are generated through the processes of molecular genetic engineering, stem cell cultivation, cloning, and transgenics, bio-artists and bio-hackers co-opt the laboratory as a site of critical cultural practice and knowledge exchange. Human embryos, trans-species and plants are constructed, commodified, and distributed across the biotech industry, forming the raw materials for bio-art, DIY biologists and open science culture.[1] These corporeal products and practices exist within new and alien categories, transgressing the physical and cognitive boundaries set by biopunk science fiction and edging towards the possibility of a destiny driven by genetics and life sciences. With the eternal rhetoric of a high-tech humanity, and the threat of Michel Foucault’s[2] biopolitics constantly on the horizon, today Harraway’s[3] myth of the cyborg exists in the form of corporeal commodities travelling through the global biotech industry. Scientific research centres stock, farm, and redistribute biological resources, (often harvested from the female scientists themselves). Cells, seeds, sperm, eggs, organs and tissues float on the biotech market like pork belly and gold. Seeds are patented, and other agro-industrial elements are remediated and distributed as bits of operational data across the biotech network. We/cyborgs[4], are manifested as a set of technologies and scientific protocols, and, as a result, the female body in particular, is reconfigured into a global mash-up of cultural, political and ethical codes.

The increasingly pragmatic realisation of the biotech revolution has provoked a ‘cultural turn’ in science and technology studies in general, and feminist science studies in particular. Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s dOCUMENTA (13) proposed an interdisciplinary approach to the role of science for ‘culture at large’. Certainly, by foregrounding the heavy hitters in the field such as Donna Haraway and Vandana Shiva, dOCUMENTA (13) laid claim to addressing the global conflicts of biotechnology. However, the feminist agenda was not specifically addressed, and the key issues of the impact of biotechnologies on feminist subjectivities were only paid minimal lip service. With the exception of Shiva[5], the tone of dOCUMENTA (13) hinted at a positivist, emancipatory take on biotechnology and technoscience without assuming a critical position. There was very little public debate or critical analysis engaging the philosophical, ethical, and political issues of feminism and female subjectivities within the realm of biotechnology.

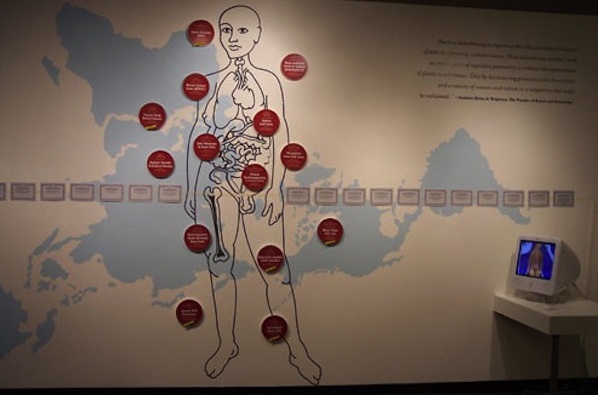

Notably absent from last year’s dOCUMENTA (13), the activist feminist collective subRosa’s performative, interdisciplinary projects are channelled towards embodying feminist content, practices, and agency, and laying bare the impact of new technologies on women’s sexuality and subjectivities – with a particular emphasis on the conditions of production and reproduction. Through their research-led practice and pedagogical mission, the collective analyse the implications and conditions of the constantly surveyed female body, whilst mapping new possibilities for feminist praxis. subRosa interrogate the conditions of surveillance, private property rights, and other control mechanisms the female body is subjected to by ART(Assisted Reproductive Technologies). The collective’s hybrid, interdisciplinary practice navigates the multiple identities the female body has taken on through techno-scientific development, including: the distributed body, the socially networked body, the cyborg body, the medical body, the citizen body, the soldier body and the gestating body. In contrast to the overarching and pervasive illustration of the technoscientific cultural landscape painted by dOCUMENTA(13), the current members and founders of the collective, Hyla Willis and Faith Wilding, are very clear in their critical intent. The collective choreograph and place themselves within globalized bio-scenarios in order to question the potential for resistance and activism within these constructs.

subRosa’s overarching vision to create discursive frameworks where feminist interdisciplinary conversations and experiments can take place, is research-led and takes its cue from the canon of radical feminist art practices. Cell Track: Mapping the Appropriation of Life Materials has featured in a number of exhibitions, most recently in Soft Power. Art and Technologies in the Biopolitical Age, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain. This project consists of an installation and website examining the privatization and patenting of human, animal and plant genomes in the context of the history of eugenics. Cell Track highlights the disparity between the bodies that produce stem cells and the corporations that control the products generated from them. Bringing together scientists, cultural practitioners and wider publics in the construct of the gallery space, subRosa generate discourse around the patenting and licensing of DNA sequences, engineered genes, stem cell lines and transgenic organisms. The project’s participatory aim is to set up an activist, feminist embryonic stem cell research lab in order to produce non-patented stem cell lines for distribution to citizen scientists, artists and independent biotechnologists. This environment of shared knowledge production and speculative, alternative, research activity is at the heart of subRosa’s social practice.

Due to the pedagogical nature of subRosa’s activities, the collective’s critical stance towards IVF and ART has proven to be particularly provocative, and their scepticism towards the emancipatory language of ‘choice’ co-opted by ART, has been met with some resistance by other feminist practitioners. However, it is in this very agonism[6] that subRosa wish to become more visible, and they welcome criticism and debate in the public discursive spaces that they create. In a recent interview, Faith Wilding and Hyla Willis both expressed their desire to generate an expanded, and deeper discussion about the wider issues involved in ART in particular and biotechnology’s effect on female identity in general. subRosa’s potential to reach wider publics and audiences is partially determined by the socio-political context of the communities in which they operate. Perhaps in reaction to this, subRosa’s focus is now shifting towards embracing the aforementioned ‘cultural turn’ in science as they address the position of feminist scientists themselves.

The imperative to reclaim feminist discourses and narratives in science is of growing concern to subRosa, as they believe that feminist agency lies in the practice of science itself. By relocating lab-work from the dominant scientific institutions to the public environment of the gallery, subRosa provide the critical space in which new feminist scientific praxis can operate,[7] and new dialogues and discourses can be created. Their conviction that political and critical traction lies in practice as discourse, and the potential of face to face encounters, is demonstrated in their recent project for the Pittsburgh Bienal: Feminist Matter(s): Propositions and Undoings (2011). In this installation, SubRosa take Virginia Woolf’s[8] assertion that ‘tea-table thinking’ provides an effective antidote to the male-driven ‘war-mentality brewed in boardrooms and command centers’ as their main conceit. Redeploying Woolf’s idea toward the rethinking of the traditionally male-dominated discipline of science, Wilding and Willis’ installation brings traces of the science laboratory to the intimacy and hospitality of the kitchen table, and in turn, also situates what is normally a private, feminized space in a more public domain.

These tables stage a dialogue between one or two visitors in response to the presentation of female figures in science, both the popularly acknowledged and the underexposed. subRosa foreground women scientists past and present and reimagine an alternative, feminized history of science and technology. The installation explores feminism and participatory practices as modes of scientific research, with the aim of generating dialogue and discourse around the questioning of the dominant historical narrative of science. Specially tailored installations reside on each table, evoking lab work while celebrating the history of the women protagonists they play host to – from anarchist painter Remedios Varo to geneticist Barbara McClintock.

subRosa’s pedagogical imperative is at once inclusive and provocative, and their role as facilitators of a discursive space outside the traditional institutions and control structures of science, is where their radical aspirations lie. Pedagogical art practices often teeter on the brink of propaganda, and subRosa are quite comfortable with the propagandistic label. Considering the economic and cultural climate in the USA with regard to the politics of reproduction, their work has been particularly well received in the context of European cultural institutions, whereas in the USA there is greater interest for the work in academic institutional settings. Perhaps this could be symptomatic of the general privileging of discourses around intersex, transgender and queer subjectivities. The dominant bias of the gatekeepers of the artworld to showcase queer practices is evident in the promotion of artists such as Ryan Trecartin and Carlos Motta on the international circuit. Curators have tended to position artists addressing the gendered ‘Other’ within a contemporary queer framework, whilst keeping feminist art practices on the peripheries of 1960s/1970s retrospective nostalgia. This tendency presents a muddying of the waters for contemporary feminist art practices such as subRosa.

This may also be part of a more general tendency to demonize and move away from feminist identities and discourses in wider society. The academic shape shifting from ‘women’s studies’ to ‘gender studies’ to ‘queer studies’ has diminished the feminist conversation and, therefore, the impact and receivership of feminist art practices. This has rendered the popular conception of ‘Queer’ as acceptable and non-aggressive. Furthermore, the term ‘Queer’ and the subsequent morphing into the verb ‘queering’, has been co-opted by transdisciplinary academic discourse, and is now an expansive, all embracing cultural term – a phenomenon that has met with a certain amount of scepticism from the queer community.

This privileging of the expansive ‘othering’ of queer rhetoric has often resulted in feminism being rejected as a radical and out-dated political identity by art practitioners themselves. This ambivalent attitude is perhaps also indicative of the wider feminist debate, in which post-feminism has splintered into fragmented, diluted groups, each policing their own identity politics with little sense of a bigger struggle. However, the collaborative, interdisciplinary environments orchestrated by subRosa signal a return to the indisputably material actuality of the female body. Through their insistence on the possibilities of feminist bench-side practices, and the forensic unpicking of the power/control structures inherent in biotechnology, subRosa expands the feminist lexicon through the empirically re-appropriated organic materiality of the body.

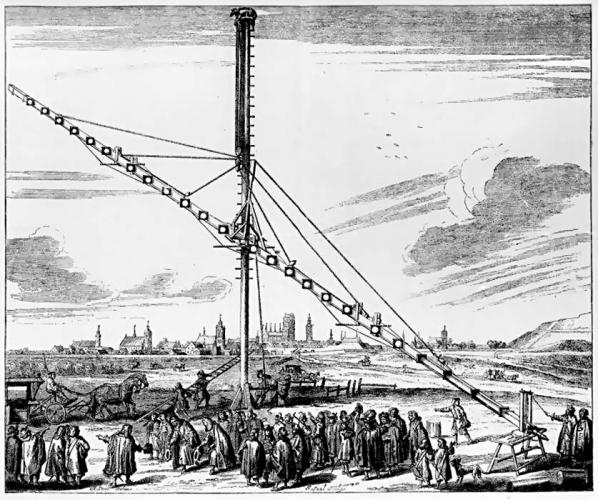

Featured image: PAH graphic resources

Over the last few years there has been a keen interest in discussing the notion of public space; demonstrations, camps, collaborative projects, artistic interventions, community projects, social activism are just a few names that exemplify the different forms of engagement that deal with the complexities of it. Despite their different aims and impact most of these actions have given evidence of the need to re-appropriate the public space; through collective and networked practices individuals, groups and organizations ‘challenge the conventional notion of public and the making of space’[1]. Although the liveness and even virality of these events, projects or actions hinder any prediction about its midterm effects or endurance, the fact is that there is an emerging legacy that is already dismantling certain assumed thoughts about ‘the public’.

The retiree Hüseyin Çetinel’s initiative of painting a public stairway with rainbow hues in his neighbourhood in Istanbul has been the last case involving cultural transformation, virality and social activism. After he painted the local stairs to ‘make people smile’ and ‘not as a form of activism’ the municipal cleaning service painted over the stairs in dull grey provoking a chain reaction that mobilized citizens to paint stairways throughout the city. Local communities and social movements appropriated this beautiful participatory action as a form of protest after Çetinel’s stairway became viral in the social media. This example shows the intricacies of the public space and its expanded performativity. As Gus Hosein Executive Director of Privacy International argues ‘there is a confusion as to what is public space is and how it relates to our personal and private space’ in a social context where the emergence of the use of social media and surveillance as well as the appropriations of the space by private corporations and social movements and individuals are constantly questioning its boundaries[2].

From my point of view, some of these actions that play in-between the social, political and artistic might be considered re-enactments of the public space as they aim to reconstruct the term itself by applying alternative procedures and by generating at the same time transductive pedagogies. However, in order to give a comprehensive understanding of the implications of the public space and its controversies it is essential to rethink the notion of the private space. Traditionally, home has been recognized as the physical private space; home is the main representative of the private sphere that encompasses the domestic and intimate. According to Joanne Hollows, ‘the distinction between the public and the private has been a key means of organizing both space and time’[3] and consequently to promote a clear functional division.

This traditional perspective has been questioned and altered due to some current issues and events that are noticeably interconnected with those of the public space; an increasing number of evictions and homeless peoples, housing policies, escraches[4] in front of the houses of politicians, the appearance of ghost neighbourhoods due to real estate speculation, home as an alternative space for performance practice and community development, among others. Thus, home might be conceived as a container of individuals and actions, as a social product or instrument, as topographical placement or as a relational structure. Home entangles interesting layers of analysis that might serve to establish new relational and yet responsive parameters to understand both the private and public space. Some of the following examples that perform between art, activism and affections corroborate the significance of home; as Blunt and Dowling state ‘home is not separated from public, political worlds but it constituted through them: the domestic is created through the extra-domestic and viceversa’[5].

In Barcelona, the city where I live there have been noticeable factors that have stressed the importance of home as a topic of interest. Probably the most significant case is the increasing number of evictions―over 350.000 in the last four years―as many families cannot afford their rent or mortgage after losing their jobs (the unemployment rate is 26.3%). Beyond the personal implications and devastating effects that evictions have on families, they also indicate that home is not anymore our secure space or refuge; on the contrary, if the individual does not respond to the production and consumption requirements is physically displaced to the streets. Consequently, many citizens are trying to find shelter back again in the public space.

If the 70s Richard Sennett announced the decay of the public space by the emergence of an ‘unbalanced personal life and empty public life’[6], the related problems with housing have provoked the reactivation of the public space at many levels. At the same time, there is an increasing culture of the debt that ties together individuals and financial institutions in long-term relationships. As Hardt and Negri explain ‘Being in debt is becoming today the general condition of social life. It is nearly impossible to live without incurring debts—a student loan for school, a mortgage for the house, a loan for the car, another for doctor bills, and so on. The social safety net has passed from a system of welfare to one of debtfare, as loans become the primary’ means to meet social needs’[7].

These ideas can be exemplified by the actions of PAH (The Platform of People Affected by Mortgage Debt), an activist group of citizens that stops evictions through demonstrations and guerrilla media actions in the streets and that also helps struggling borrowers to negotiate with banks and promotes social housing[8]. This organized group of citizens has been awarded this year the Citizen Award by the European Union for denouncing abusive clauses in the Spanish mortgage law and battling social exclusion. PAH has received the support of the collective Enmedio that generates actions in the midst of art, social activism and media. For example, their photographic campaign ‘We are not numbers’ consisted in the design of a collection of postcards each one containing a portrait of a person that was affected by the mortgage debt by a local bank entity. The postcards were delivered in front of the bank’s main building for people to write a message. The written postcards were then stuck in the front door main door turning numbers into a collage of human struggle. PAH and Enmedio actions become highly effective thanks to their media impact and their virality in the social media. Invisible individuals isolated in their struggle, find alternatives through an assemblage of support that connects the public and private space and that is also mediated by informative and constitutive tools that the virtual space offers. As Paolo Gerbaudo claims ‘social media have been chiefly responsible for the construction of a choreography of assembly as a process of symbolic construction of public space which facilitates and guides the physical assembling of highly dispersed and individualized constituency’[9].

Processes of speculation, gentrification and eviction can be found in many western cities as well as different kinds of collectives and groups working for human rights advocacy. This is also the case of the Brooklyn based collective Not an Alternative has also carried out different guerrilla actions concerned with the problem of housing and eviction such as their series of workshops and media actions of ‘Occupy Real State’ or ‘Occupy Sandy’.

Many of the actions that these collectives promote might be understood as DIY activism as they are based on the empowerment and the development of skills. In this regard, it is interesting to observe how DIY that traditionally has been related to activities in the domestic space serves as a strategy to protect it and to trigger new forms of protest in the public space while enhancing the creation of an expanded family (or at least a sense of togetherness) through the social media.

Despite these actions, the public space is still home for many individuals. In the UK, different associations are concerned about the impact that the implementation of the bedroom tax might have, especially in London where the number of rough sleepers rises every year with an increase of the 62% since 2010-2011. The scenario is not different in many other European cities where beyond these worrying numbers there is also an increasing number of regulations and policies that difficult the life in the public space. As Suzannah Young stresses, ‘homeless people often need to use public space to survive, but are regularly driven off those spaces to satisfy commercial or even state interests’. Public space is often only open to ‘those who engage in permitted behaviour, frequently associated with consumption’[10]. The increasing number of quasi-public spaces―’spaces that are legally private but are a part of the public domain, such as shopping malls, campuses, sports grounds’ and so forth― questions again the boundaries of the private and public space, especially when ‘some EU cities use the criminal justice system to punish people living on the streets for doing things they do in order to survive, such as sleeping, eating and begging’[11]. All these policies have clear implications in the use of space and it is potential possibilities. The fact that the public space becomes home involves the reconsideration of the uses of the public space and the understanding of it through the eyes of the people that fully inhabit it. The London collective The SockMob run the Unseen Tours, alternative city tours guided by a group of homeless. Their embodied knowledge appears as a key aspect to develop these DIY versions of the city while promoting relationships between the homeless and the tour participants.

Where is home? In which ways access to spaces gives us opportunities and rights as individuals? In which ways all these site-specific initiatives that often have a transnational reach re-construct the notions of private and public space? How these DIY and media actions are generating new forms of visual arts activism? Despite the fact that these queries might need further analysis, I believe that the qualities of space becomes visible and tangible through these interactive and responsive actions with the spaces. Recently, an international group of activists, visual artists and scholars have published a handbook in which their consider these forms of activism militant research. According to them, ‘militant research involves participation by conviction, where researchers play a role in the actions and share the goals, strategies, and experience of their comrades because of their own committed beliefs and not simply because this conduct is an expedient way to get their data. The outcomes of the research are shaped in a way that can serve as a useful tool for the activist group, either to reflect on structure and process, or to assess the success of particular tactics’[12]. Hence, the idea of some hands-on, the acquisition of skills and the performance of theory appear as key aspects to disentangle and analyse the qualities of the space.

From an artistic perspective home has been crucial in many historical periods of dictatorship to construct an underground scene of the arts; in many of these cases, the evidence of artistic practice appears through testimonials and documentation (photographs, fanzines, recordings, etc.). Again different forms of media help to make the clandestine public, crossing the sphere of the private into the public realm. Thus, the importance of documentation enhances different temporalities of reception and impact in the public realm. In this regard, a differed presentation of the artistic works triggers a reconsideration of the attributes of the spaces too. Currently, homes serve as a basic space for artists to present their work; in the case of music, this is a widely known practice in the US that is becoming more and more common in other countries and other art forms. Homes serve as a personal curatorial space for fine arts artists through the open studio festivals too; artists make their private space open for others as a strategy to show their work publicly. At the same time, in some artistic disciplines self-curation through digital portfolios is becoming increasingly used to showcase artworks. One way or another, home remains often the main space for creativity, production and curation through and expanded DIY conception of their profession.

Home becomes even more crucial in a context marked by the arts cuts and the economic crisis. In this regard, there are initiatives that see an opportunity in the relationship between the public and private space not only to exhibit or perform art but also to trigger a counter-performative form of showing works. This is the case of the domestic festivals that try to challenge the concepts of cultural enterprise and institution by proposing home as a legitimate space of the artistic experience. Friends, neighbours and acquaintances offer a room or a space in their house for artists to perform there (examples can be found in different cities such as Santiago de Chile, Madrid, Berlin, Barcelona, etc.). At the same time, the format wishes to transform the spatial and affective relationships that citizens have with the space, by inverting the spatial dichotomy between the public and the private. Hence, the idea goes beyond to a practical solution to have a space to perform as it also aims to give visibility to performing practices that have not been yet legitimized by the public sphere and they are in danger to remain in a sort of clandestinity (as they are not part of the current cultural market). In this regard, there is also a sense of evicted or homeless art that is trying to produce a social context of experience and articulation beyond the immediate effects of the power that governs at many level the public sphere. These kinds of initiatives generate ‘an activity that undermines the exclusion by letting occur, at the very boundary which separates the public from the “secret”’, an articulation which challenges the prevailing framework of representation and legitimation’[14].

The intersection between art, activism and affections help to explain the multiple and complex questions that configure the notion of home. With these examples I just wanted to stress the importance of home in the discourses that address the concepts of public space/public sphere/publicly. Thus homes ‘are thereby metaphorical gateways to geopolitical contestation that may simultaneously signify the nation, the neighbourhood or just one’s streets’[15]. From a transnational perspective, home seems to pose the crucial questions that connect us with what is happening inside, outside and in-between the spaces and gives us a different perspective to analyse current artistic and social practices that engage with our mode of action, production and identity.

I guess this is all from my home.

Public Screening and Discussion at Furtherfield

Contact: info@furtherfield.org

Visiting Information

THE EVENT HAS LIMITED AVAILABILITY.

PLEASE RSVP TO BOOK YOUR PLACE TO ALESSANDRA

Cornelia Sollfrank will present her latest film Giving What You Don’t Have. It features interviews with individuals Kenneth Goldsmith, Marcell Mars, Sean Dockray, Dmitry Kleiner, discussing with Sollfrank their projects and ideas on peer-to-peer production and distribution as art practice. It includes the projects ubu.com or aaaaarg.org, which combine social, technical and aesthetic innovation; they promote open access to information and knowledge and make creative contributions to the advancement and the reinvention of the idea of the commons.

The post-screening discussion will be led by Cornelia Sollfrank, Joss Hands & Rachel Baker.

On the basis of the interviews of Giving What You Don’t Have, we would like to discuss some of the issues they represent such as new forms of collaborative production, the shift of production from artefacts to the provision of open tools and infrastructures, the development of formats for self-organisation in education and knowledge transfer, (the potential and the limits of) open content licensing as well as the creation of independent ways of distributing cultural goods. An implicit part of Giving What You Don’t Have is a suggested reconceptualization of art under networked conditions.

Cornelia Sollfrank is a postmedia conceptual artist and interdisciplinary researcher and writer. She studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich and fine art at the University of Fine Arts of Hamburg (1987-1994). Since 1998 she has taught at various universities and written on issues in the nexus between media, art and politics. In 2011 Sollfrank completed her practice-led interdisciplinary research at Dundee University (UK) and published her PhD thesis with the title Performing the Paradoxes of Intellectual Property. In addition to her work in the artistic and academic fields, Sollfrank gathered experience in the private sector by working as product manager for Philips Media for two years (1995-1996).

Joss Hands‘ research engages the relationship between media, culture and politics. His recent work has explored the role of digital media in direct action, protest and activism, culminating in his book @ is For Activism: Dissent Resistance and Rebellion in a Digital Culture, published by Pluto Press in 2011. His previous research has explored the role of new media in formal democracy and governance as well as its cultural, economic and social impact. He has published in a number of journals such as Information, Communication and Society, Philosophy and Social Criticism and First Monday as well as writing commentary for publications such as Open Democracy, IPPR Journal, The New Left Project, and others.

Rachel Baker is a network artist who collaborated on the influential irational.org. Her art practice explores techniques used in contemporary marketing to gather and distribute data for the purposes of manipulation and propaganda. Networks of all kinds are “sites” for Baker’s public and private distributed art practice, including radio combined with Internet (Net.radio), mobile phones and SMS messaging, and rail networks. She has presented and exhibited work internationally at various new media and electronic art festivals.

Giving What You Don’t Have is an artistic research project commissioned by the Post-Media Lab, Leuphana University.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England.

LIVE LINK HERE

In collaboration with Annie Abrahams and Emmanuel Guez, Furtherfield presents two new ReadingClub sessions based on excerpts from McKenzie Wark’s A Hacker Manifesto [version 4.0] and the ARPANET dialogues.

ReadingClub proposes a text and an interpretive arena to 4 readers. These readers write together their reading of a text inside the text itself. The audience sees an evolving, cinematographic picture of thoughts and collaborative writing in the making.

Join the performance online at readingclub.fr and use the chat window to exchange, discuss and comment on the performance.

Monday 21 October 2013, 8pm London Time – A Hacker Manifesto [version 4.0]

Online performance session based on an excerpt from A Hacker Manifesto [version 4.0] by McKenzie Wark – with Aileen Derieg, Cornelia Sollfrank, Dmytri Kleiner and Marc Garrett.

Drawing in equal measure on Guy Debord and Gilles Deleuze, A Hacker Manifesto offers a systematic restatement of Marxist thought for the age of cyberspace and globalization. In the widespread revolt against commodified information, McKenzie Wark sees a utopian promise, beyond the property form, and a new progressive class, the hacker class, who voice a shared interest in a new information commons.

Tuesday 22 October 2013, 8pm London Time – The ARPANET dialogues

Online performance session based on an excerpt of the ARPANET dialogues from 1975-1976 – with Alessandro Ludovico, Jennifer Chan, Lanfranco Aceti and Ruth Catlow.

The ARPANET dialogues is an archive of rare conversations within the contemporary social, political and cultural milieu convened between 1975 and 1979 that were conducted via an instant messaging application networked by computers plugged into ARPANET, the United States Department of Defense’s experimental computer network. All participants in the conversation were given special access to terminals connected to ARPANET, many of them located in US military installations or DOD-sponsored research institutions around the world.

What was originally thought to be a historic moment, when figures from within and without the established art canon first encountered the disruptive effects of digital network communications, turned out to be an ongoing research project by Bassam El Baroni, Jeremy Beaudry and Nav Haq.

Further reading:

“This pre-Internet chatroom conversation between Jim Henson, Ayn Rand, Yoko Ono and Sidney Nolan is fake. But it’s amazing” – Robert Gonzalez in io9, December 2012.

“Ronald Reagan has joined the chatroom” – Interview by Richard Fischer, CultureLab with Jeremy Beaudry, one of the artists behind the project, April 2011.

The ReadingClub is a project by Annie Abrahams and Emmanuel Guez, inspired by Brad Troemel’s Reading Group and the Department of Reading by Sönke Hallman.

The project is supported by Dicréam.

+ More information about ReadingClub

Richard Stallman[1] the outspoken promoter for the Free Software movement, hates Facebook with a passion. He proposes that we should all leave Facebook and either find or build our own alternatives. The evidence offered by Stallman’s and the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s (EFF), who have been fighting for Internet freedoms since the 90s [2] shows how necessary it is that we understand and are more pro-active in managing the personal data that we give away through our online activities.

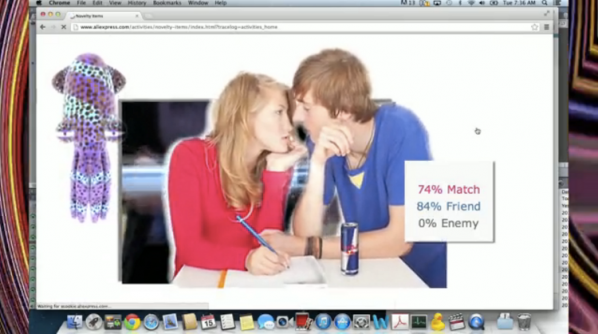

When we subscribe to Web 2.0 platforms such as Facebook we are at the mercy of the data brokers. These companies trade in people’s personal data; information which is aggregated by monitoring user actions and interactions across social media. This information can include “names, addresses, phone numbers, details of shopping habits, and personal data such as whether someone owns cats or is divorced.”[3] Fast moving developments in social media, make it difficult to keep up with the effects and consequences of these platforms. This is why the work of groups such as Commodify Inc. is so valuable. They bring imaginative and critical attention to the situation, sharing their knowledge of these daily networked complexities and correcting what they see as its negative effects.

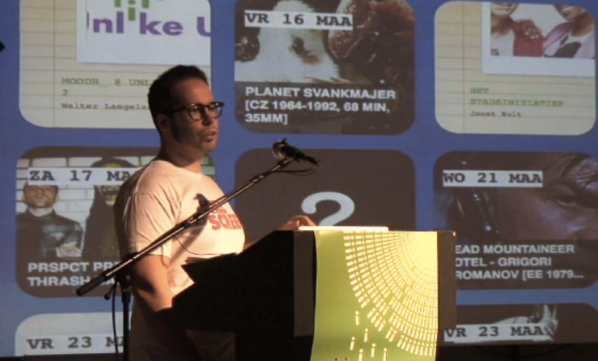

Commodify Inc. is an artist-run Internet startup producing projects to help individuals capitalize on their online monetary potential. Their intention is to correct the imbalance of power in markets where users have no control over the transactions made with their personal data. They have completed various artistic projects and interventions on social media like, Fame Game, Give Me My Data, and Web 2.0 Suicide Machine. The co-founders are Birgit Bachler, Walter Langelaar, Owen Mundy, Tim Schwartz, with additional contributors Joelle Dietrick and Steven Alvarado.

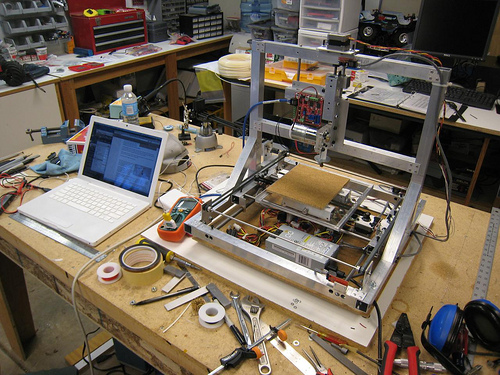

Their new project Commodify.Us, was initiated when Owen Mundy and Tim Schwartz were invited by moddr_ to a residency in their lab in the summer of 2012 – when they were still a part of the WORM collective in Rotterdam. They worked on an initial idea that would succeed previous experiences of their already well-known and respected projects.

Commodify.Us is currently in beta phase. It promises to provide a platform for people to regain control over the commercial exploitation of their own personal data.

Intrigued by this project I contacted one of the co-founders, Walter Langelaar via email and asked him a few questions about this new platform.

Marc Garrett: Commodify.Us is for people to have greater control over their data. And it works when users export their data from social media websites and upload it to your platform. How will these users gain more control over their data and why is this important?

Walter Langelaar: Commodify.Us provides a platform for you to regain control over the commercial exploitation of your personal data. After exporting your profile data from social media websites and uploading the data to Commodify.Us, you can directly get in contact with interested buyers. On the importance for users I would say that it’s part raising awareness surrounding the monetization of profile data, and part creating a platform where people might work out and discuss how to do this themselves.

MG: It proposes to re-imagine the potential of relational data, creating a casting agency for virtual personas. I’m wondering what this may look like?

WL: We were too. In an early stage of the project we played with the idea that peoples’ various profiles could function like that within an agency; a client would ask for a specific set of qualities and/or characteristics within a set of profiles, and we could provide for this based on the uploads and their licensing options as set by the user. In the end we abandoned this idea for clarity.

MG: Commodify.Us offers people the opportunity to be part of an economy where interested buyers will pay to use the data supplied, unlike existing social media websites. How does this work?

WL: We are gearing up for a launch where the main goal will be to get a critical mass of around, a 1000 profiles. We anticipate that only with this kind of mass or volume will our initiative take hold with the potential buyers we have in mind, and the same goes for the more creative projects that could use the (open) data. Regarding the open profile data and otherwise licensed profiles that allow for reuse, we are researching the idea of ‘Fair Data’ (as in Fair Trade) and how to implement this as a profitable protocol for the end-user.

“Net activists construct tools whose intervention potential can be initiated by users under net conditions. These tools enable activists to develop new strategies in the data space of the Internet because they offer new means: New means afford new ends.”[4] (Dreher)

In his publication Networks Without a Cause: A Critique of Social Media, Geert Lovink lays down the gauntlet and asks us to “collectively unleash our critical capacities to influence technology design and workspaces, otherwise we will disappear into the cloud.” Anna Munster opens her excellent survey, Data Undermining: The Work of Networked Art in an Age of Imperceptibility, by saying “The more data multiplies both quantitatively and qualitatively, the more it requires something more than just visualisation. It also needs to be managed, regulated and interpreted into patterns that are comprehensible to humans.”[5] Commodify.Us goes one step further by allowing users to manage, regulate, repattern and reappropriate their own data using tools that share an essential functionality (if not purpose) with the power tools of Web 2.0.

Those previously seen as rebellious hacktivists are moving into new territories that deal with concepts of service. There has been a significant rise of artists exploring technology to influence mass Internet activity, against the domination of corporations who are data mining and tracking our on-line activities. Another example is TrackMeNot developed by Daniel Howe and Helen Nissenbaum. This is an extension created for the Firefox browser. “It hides users’ actual search trails in a cloud of ‘ghost’ queries, significantly increasing the difficulty of aggregating such data into accurate or identifying user profiles.”[6]

Howe and Nissenbaum mention they are aware their venture is not an immediate solution. However, the more we hear of and join these imaginative strategies “whereby individuals resist surveillance by taking advantage of blind spots inherent in large-scale systems” [7], and the more we adapt our behaviours to adopt these new ‘activist’ services, the more we demonstrate the demand for these new alternatives. And by so doing, we argue for the value of services that we can trust not to steal or manipulate our social contexts for financial and political gain.

A significant value offered by the Commodify.Us platform is the power to manage our own data. The simple act of downloading our own data from Facebook, and then uploading it to Commodify.Us supports us to rethink what all this information is. What once was just abstract data suddenly becomes material that we can manipulate. Alongside this realization arrives the understanding that this material was made by our interactions with all these platforms, and that other people are spying on us and making money out of it all. Once this data material is uploaded onto the Commodify.Us platform, it asks if we want this stuff to be a product under our own terms, or if we wish to make art out of it using their tools.

This is a cultural shift that demonstrates how contemporary Hacktivists are developing software that promises to offer realistic service infrastrucutures. When I interviewed Charlie Gere in 2012[8] he said that these artists “are not part of the restricted economy of exchange, profit, and return that is at the heart of capitalism, and to which everything else ends up being subordinated and subsumed. Thus they find an enclave away from total subsumption not outside of the market, but at its technical core.” For me, this kind of work is of central importance to the contemporary era, and it only occurs where artists cross over into territories where their knowledge of networks directly contributes to the building of alternative structures of social independence.

In conjunction with Shu Lea Cheang and Mark Amerika exhibition, Furtherfield is pleased to host Shu Lea Cheang’s Seeds Underground Party.

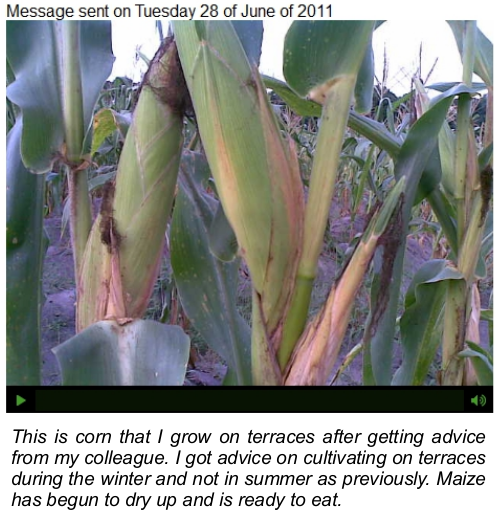

In certain parts of the world, the vast farmlands have been colonised by genetically modified crops for our staple foods (i.e. wheat, soybeans, corns). Introduced 30 years ago, the transgenic biotechnology has since been commercialised by the patent-protected corporate sectors. Taking over the wholesale markets, the Herbicide-tolerant and pest-resistant seeds promise higher yields and profits without much ecological concerns. This year, the European Union is about to adopt a new seed policy, which favours the seed industry corporations by making all seeds subject to strict regulation. It is feared that this will hurt organic varieties and prevent seed exchange by seed farmers and savers.

Join us for a seed exchange party where packets of seeds change hands and go underground in the fields around Finsbury Park and beyond.

Bring your self-harvested homegrown seeds of sorts! Sign on to trade seeds, to adopt and germinate, to broadcast and track their distribution. Share some food, drinks and seeds stories while we celebrate the harvest season together in the relaxing setting of Finsbury Park.

+ To join Seeds Underground Party, and trade and track your seeds, please register on http://seedsunderground.net

Click on TRADE and select Furtherfield, London from the “join a seeds underground party” pull down menu.

Seeds Underground holds seed exchange parties where packets of seeds change hands and go underground in the fields across nation borders.

+ More information:

now@seedsunderground.net

www.seedsunderground.net

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England

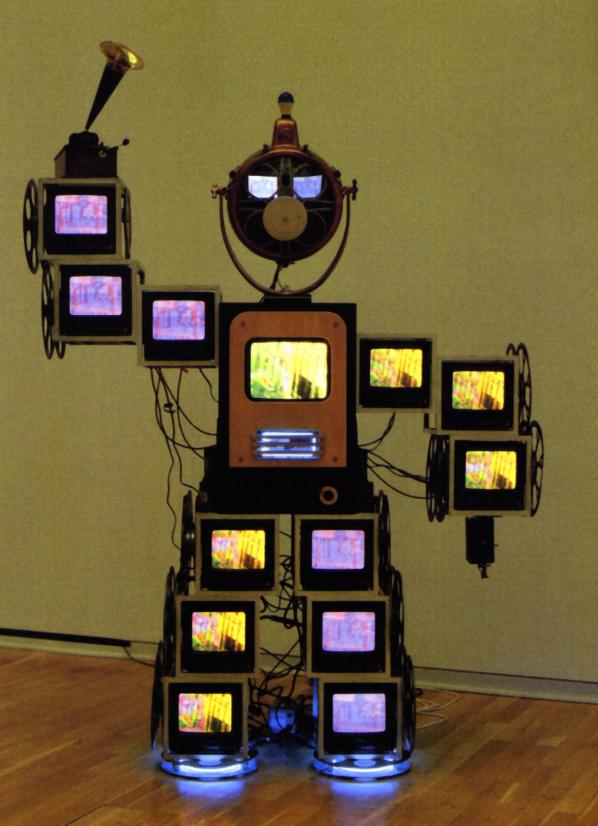

Featured image: Outsider Art

The 55th Venice Biennale has arrived, and with it brings a new state of trends which are pontificated around, with a chuckle, a sense of forced opportunity and the shrugged sigh of ‘well, everyone’s doing this now apparently.’

The trend in question consists in a renewed attention towards Outsider Art (as famously termed by Roger Cardinal), or perhaps more famously the return of Jean Dubuffet’s ‘Art Brut’, under the modern moniker of ‘Folk Art’; the famous definition given to artworks, constructed outside of the critical art world system or outside the world of aesthetic critique. Specifically, Outsider Art denotes a straightforwardness of practice, which deliberately rejects, or remains unaffected by artistic techniques and instead embellishes a bold directness or authentic personal vision. This, we are told, is a renewed return to the interests of authentic practitioners, giving spectators the chance of ‘trying to see more’ in the broadest sense. These are artists who exist without official global branding, nor the ease of stylistic marketing, nor the calculated requirements of visitor numbers.

Outsider artworks (echoing Dubuffet) are aesthetically valuable, precisely insofar as they haven’t been created for the sole purpose of critique, nor for being deliberately market-friendly (the last point is quite contentious). They are what they are. Or at least, ‘what they are’ is grouped around a deviation from the mainstream ‘norm’.

Massimiliano Gioni, the latest curator of the world’s oldest contemporary art exhibition, titled its flagship show “The Encyclopedic Palace” after the self-taught artist Marino Aurtit (1891 – 1980), and his elaborate proposal to build a house of knowledge in Washington D.C. Gioni warned that the Biennale would not trace the familiar ‘who’s who’ of previous festivals (despite having its usual art stars), but will, in part, follow the aesthetic footsteps of the ‘illustrious nobody’ and ‘dilettante’, like Aurtit. Gioni even joked that this biennale, may be exposed as a “thrift-store biennial’ – yet his entire intention is to “break away from this pressure of the new“. True to his word, you wouldn’t exactly find an entire room dedicated to Carl Jung’s Red Book manuscript, or Rudoph Steiner’s blackboard drawings, at major art fairs.

Just last week, the Hayward Gallery has been one of the first public-funded galleries in Europe to host a major event which focuses entirely on Outsider art: “An Alternative Guide to the Universe“. Unlike Gioni’s effort, the entire Hayward gallery is filled with self-taught, yet highly skilled obsession-led projects from the private wing of the aesthetic fringe: the intricate math puzzles of George Widener or the technical drawings of Karl Hans Janke, a schizophrenic inventor who envisioned rockets running on clean energy. There is, like most major art shows these days – lots of ‘stuff’ here – all of it inherently odd and some, self-knowingly disturbing – like the Bostonian bachelor Morton Bartlett, who created his own peculiar family of female dolls, or Eugene von Bruenchenhein’s awkward images of his wife acting in unsettling roles, like a non-deliberate Cindy Sherman series. Speaking of Sherman-seque photographs, Lee Godie’s 20’s style, self-portraits (also showing at the Hayward) are a firm favourite with private collections. Godie, who died penniless in 1994, and lived homeless on the streets of Chicago, sold her photographs on the streets for roughly $30, yet they can now expect to fetch $15,000.

Linking the two exhibitions is the remarkable charity The Museum of Everything, showing the work of Nek Chand at the Hayward and having their own pavilion at the Venice, of the back of previous shows in Moscow and Paris this year. Elsewhere in London, the Wellcome Collection showed off the successful show Souzou, exhibiting Outsider Art from Japan.

But over and above, these recent shows, why have the mainstream become so interested in Outsider Art? Or have they always been interested? Why are curators so fascinated with the darker side of the outsider, the other? Why are Bartlett’s unintentionally disturbing contemporary prints worthy of a 2007 solo show at the Julie Saul Gallery, in New York? The trend could be looked at as a self-realised view of the art world turning in on itself. It has finally realised how insular it has become, and needs to do something more cultural than a retrospective of a modern master here, or a lucrative solo show of some flavour of the month there. It has decided to become more ‘open’. The self-taught, yet sincere visions of mental patients, spiritual mediums, eccentric historians and utopian visionaries have once again reignited the art market’s purview. Certain works, never deliberately constructed for the whims of curators and spectators are now, insatiably lucrative.

The irony of this is… well, beyond irony. There is a deep sense of self-cannibalism at the heart of reclaiming the autobiographical eccentricities of others. As the lucrative self-direction of the art market now casts it’s eye over the purchase of collectable outsider art, and all its naive aesthetic principles, they cannot but be aware of the paradox within the trend itself. The recession-proof art market, self-knowingly creates inequality with one hand, whilst branching out of its self-constructed insular network with the other. Whilst it gobbles up, callow drawings from psychiatric patients and innocent pieces from batchelors for a tidy sum, the market simultaneously disgorges itself with folk, liberal, self-esteem. Clearly this is not an unprecedented trend, but the scale with which outsider art is being collected, exhibited and purchased in the last few months, as well as its public funded backing, certainly brings with it a large dose of incredulous cynicism.

The turn to Outsider Art is, unexpectedly not new and the mainstream art world has a habit of doing this every decade or so. Such aesthetic interest on the ‘darker’ element of outsider art, can be traced back to 1922, when psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn published ‘Artistry of the Mentally Ill‘, a collection which included ten self taught artists battling with schizophrenia. In 1929, MoMA’s first director Alfred Barr, identified self-taught art as one of the three major movements in modern art, alongside Surrealism and Abstraction. MoMa even organised the show “American Folk Art: The Art of The Common Man in America 1750 – 1900” in 1932. Even the Hayward appears to be repeating itself, as it organised (with Roger Cardinal no less) the show “Outsiders: Artists without Precedent or Tradition” in 1979.

As Jane Kallir wrote 10 years ago, in the article “Outsider Art at a Crosswords” for Raw Vision magazine, the history of Outsider Art is draped in a dialectical contradiction that even Hegel couldn’t have made up. For our purposes, she sums it up perfectly.

“Outsider art is not a game that the artists themselves are allowed to play. An artist is anointed an “outsider” by members of the mainstream who have determined that he or she, for whatever reasons of mental incapacity or biographical circumstance, is incapable of fully comprehending or adhering to mainstream traditions.”

Outsider art suffers from a necessary, yet expected paradox. Once the mainstream embraces its status, it can only become suffocated, and, quoting Kallir again, “[o]nly when the mainstream’s attention is engaged elsewhere can any sort of truly isolate art flourish.” This is why, she argues, previous historical booms of Outsider art, between the two World Wars, eventually petered out. The “insiders” seek to hoover up the “outsiders”, negating the latter, and extending the former – making such dichotomies either useless or pointless. But it’s not as if the mainstream exists without distinctions, it’s just that these distinctions are inanely hypocritical. You know things are bad when even Will Gompertz notices.

Moreover, the historical return to Outsider art does little to characterise what it actually is, rather than characterise what the mainstream wants it to be: and this return is no different. In a hyper-connected epoch, it gets even worse. Who decides when an artist is an outsider? Legitmately, all artists may consider themselves to be outsiders (and especially the fringe of exceptional ‘media arts’ – although we’ve been here before).

As Rosie Jackson writes (no relation), outsider art becomes a ‘convenient cipher’ for everything the mainstream wishes it could ever be: “uncensored, meaningful, compulsive activities hammered out in blood, sweat and tears.” Every historical return to Outsider art retains a basic notion of ‘openness’ and ‘difference’ along some lines, yet such terms also fail to help understand the work ‘as’ work, and instead only understands it as ‘other’, through an insular structure that filters membership on its own terms. This recent interest the posthumous fringe, takes on the basis of carrying a cultural conscience in the art market.

In my eyes, the commercial art market seems to be integrating itself with the broad appeal of cultural capitalism (or capitalism with a conscience). The famous and sweaty pop stalinist, Slavoj Žižek, has previously articulated the logic of cultural capitalism quite well. Even the most unaware consumers in the Western world are acquainted with this modest shift in capitalist values. Corporations embrace the problems of poverty, and so market their products with ‘built in’ commitments for helping out the poorest in the world – the ones who fell over at the start of the ‘global-race’. One would call it capitalism with a human face, but we have gorged out on irony, for too long.

Žižek calls on two particular noteworthy examples; Starbucks Coffee and TOMS Shoes. Go round the corner to a local Starbucks and they will go to great lengths about how you, the consumer are not just ‘buying a coffee’ – instead they are buying coffee with a built-in disclaimer: that a portion of the customer’s money will help the workers who cultivate the coffee-beans and distribute that portion onwards. Similarly the incredibly successful TOMS Shoes, goes one step further with their ‘one for one‘ commitment: when you purchase a relatively cheap pair of TOMS Shoes, a portion of the profits accumulated, help manufacture another pair of shoes which are given to a child in poverty. We get the product, they get the profit, a child without shoes gets some shoes – what’s not to like?

Žižek tentatively retorts that charitable capitalism is, clearly better than the ‘business as usual’ practices of speculation and exploitation, in quasi-abstract way. But, he avers, one cannot fail to see the paradox of this gesture. The consumer is buying, not just the product, but the cultural impact of the company’s ethics. As a result, there is what Žižek calls, a ‘semantic overinvestment or burden‘ in being a consumer here. You don’t just simply buy a product and consume it, your consumerist ethical redemption is included in the price. In a typical Žižekian rejoinder, he borrows from Oscar Wilde’s lucid declaration in ‘The Soul of Man Under Socialism‘ that;

“Just as the worst slave-owners were those who were kind to their slaves, and so prevented the horror of the system being realised by those who suffered from it, and understood by those who contemplated it, so, in the present state of things in England, the people who do most harm are the people who try to do most good.”

Even though the slaves were momentarily protected from brutal oppression, the kind acts of conscience from their masters, masked the reasons behind their inequality, failing to change the inherent systems that determined their slavery in the first place. Rather uncompromisingly, Žižek argues that commodifiable charitable exchange that grounds cultural capitalism, degenerates the unequal situation even further. Capitalism partially modifies its operations to address inequality by marketing products that appeal to consumer conscience, whilst marginally improving the conditions for poor communities: communities which the market has indirectly caused, through profit accumulation in the first place. Instead the only proper ethical act, should be to modify state regulation to such an extent that inequality and descent into poverty become impossible: not a consumerist disclaimer designed to partially help the poorest through a system which self-inflicts the very reasons for poverty (i.e. if Starbucks really wanted to reconfigure its ethical marketing, it should start by paying its expected levels of corporate tax).

This recent focus on outsider art is largely (but not exactly) based on a similar turn of hypocrisy, but instead of appealing to consumerist cultural value, it appeals to the elite’s bloated levels of aesthetic cultural value, not the works or the artists themselves. Instead of modifying and reconstructing the market to regulate and protect the careers of living artists working today and help artists who are marginalised through no fault of their own, the art world twists itself into valuing outsider artworks which keep the attendee’s conscience happy, yet mask its inherently peculiar logic. ‘You are not just appreciating an artwork, you are appreciating a different, alternative way of life.’

If you think I’m joking about how literal this comparison is, you only have to look at the 2011 exhibition, Mindful: which brought together the choice cut of the YBA market, in order to raise funds and awareness about the stigma of mental health. Although the show was not ‘Outsider Art’ as such, it dipped its toe in from both angles; mainsteam artists grappling with issues on mental health and the pragmatic benefit of making art for those who suffer from it. Again, this is not to say that the results of the show, or the work of artists, (outsider or otherwise) are without merit – this is about the latent hypocrisy of providing audiences with cultural and ethical overinvestment, the terms upon which are already decided by mainstream principles. The fact that one of the sponsors was Starbucks, tells you everything you need know.

The conclusion to draw from this, is that the art market’s endorsement of Outsider Art contributes to it’s insularity rather than genuinely addressing the actual structure which contributes to the problems that outsider artists face. Outsider art only remains interesting, or opens up a productive discussion so long as the mainstream finds it lucrative enough to include such a discussion on its own terms. The mainstream artworld finds itself in a curious place then: for whilst it knocks down with its right hand, what it builds with the left, it curiously remains as it is, as it was, and ever present. To paraphrase Wilde, “It is much more easy to have sympathy with outsider artists than it is to have sympathy with thought.”

————————

If you would like to donate money directly to charities who specialise in the exhibition of marginalised artists, you can do so at the following links.

Outside In: an arts agency which provides a platform for artists who find it difficult to access the artworld.

And of course, Furtherfield.

Featured image: Thomson and Craighead, Here (2013)

Visiting Jon Thomson and Alison Craighead’s survey exhibition, Never Odd Or Even, currently on show at Carroll / Fletcher Gallery, I found myself confronted with an enigma. How to assemble a single vision of a body of work, impelled only by the dislocated narratives it offers me? ‘Archaeology’ is derived from the Greek word, arche, meaning ‘beginning’ or ‘origin’. The principle that makes a thing possible, but which in itself may remain elusive, unquantifiable, or utterly impervious to analysis. And so it is we search art for an origin, for an arising revelation, knowing full well that meaning is not something we can pin down. Believing, that the arche of a great work is always just about to take place.

In an essay written especially for the exhibition, David Auerbach foregrounds Thomson and Craighead’s work in the overlap between “the quotidian and the global” characteristic of our hyperconnected contemporary culture. Hinged on “the tantalising impossibility of seeing the entire world at once clearly and distinctly” [1] Never Odd Or Even is an exhibition whose origins are explicitly here and everywhere, both now and anywhen. The Time Machine in Alphabetical Order (2010), a video work projected at the heart of the show, offers a compelling example of this. Transposing the 1960 film (directed by George Pal) into the alphabetical order of each word spoken, narrative time is circumvented, allowing the viewer to revel instead in the logic of the database. The dramatic arcs of individual scenes are replaced by alphabetic frames. Short staccato repetitions of the word ‘a’ or ‘you’ drive the film onwards, and with each new word comes a chance for the database to rewind. Words with greater significance such as ‘laws’, ‘life’, ‘man’ or ‘Morlocks’ cause new clusters of meaning to blossom. Scenes taut with tension and activity under a ‘normal’ viewing feel quiet, slow and tedious next to the repetitive progressions of single words propelled through alphabetic time. In the alphabetic version of the film it is scenes with a heavier focus on dialogue that stand out as pure activity, recurring again and again as the 96 minute 55 second long algorithm has its way with the audience. Regular sites of meaning become backdrop structures, thrusting forward a logic inherent in language which has no apparent bearing on narrative content. The work is reminiscent of Christian Marclay’s The Clock, also produced in 2010. A 24 hour long collage of scenes from cinema in which ‘real time’ is represented or alluded to simultaneously on screen. But whereas The Clock’s emphasis on cinema as a formal history grounds the work in narrative sequence, Thomson and Craighead’s work insists that the ground is infinitely malleable and should be called into question.

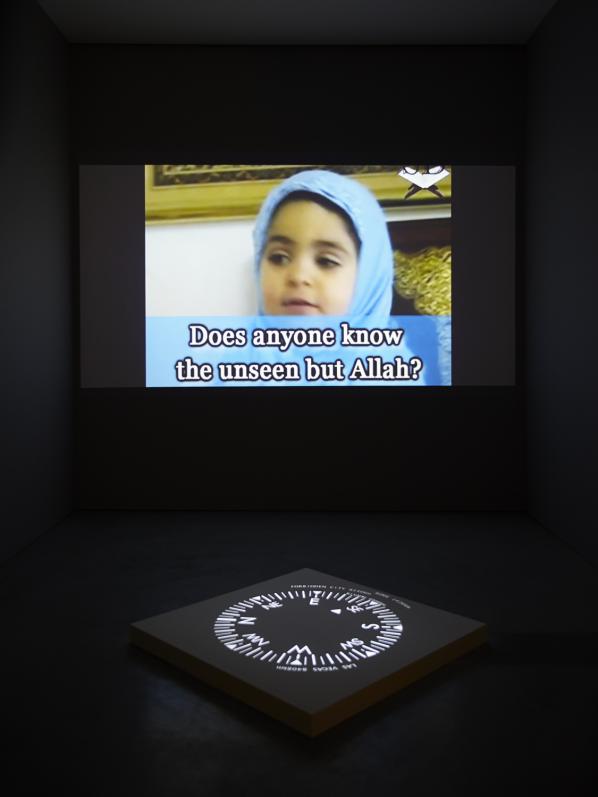

Another work, Belief (2012), depicts the human race as a vast interlinked, self-reflexive system. Its out-stretched nodes ending at webcams pointing to religious mediators, spiritual soliloquists and adamant materialists, all of them searching to define what it means to be in existence. Projected on the floor of the gallery alongside the video a compass points to the location each monologue and interview was filmed, spiralling wildly each time the footage dissolves. Each clip zooms out of a specific house, a town, a city and a continent to a blue Google Earth™ marble haloed by an opaque interface. Far from suggesting a utopian collectivity spawned by the Google machine, Belief once again highlights the mutable structures each of us formalise ourselves through. As David Auerbach suggests, the work intimates the possibility of seeing all human kind at once; a world where all beliefs are represented by the increasingly clever patterns wrought through information technology. Instead, culture, language and information technology are exposed as negligible variables in the human algorithm: the thing we share is that we all believe in something.

Never Odd Or Even features a series of works that play more explicitly with the internet, including London Wall W1W (2013), a regularly updated wall of tweets sent from within a mile of the gallery. This vision of the “quotidian” out of the “global” suffers once you realise that twitter monikers have been replaced with each tweeter’s real name. Far from rooting the ethereal tweets to ‘real’ people and their geographic vicinity the work paradoxically distances Thomson and Craighead from the very thing twitter already has in abundance: personality. In a most appropriate coincidence I found myself confronted with my own tweet, sent some weeks earlier from a nearby library. My moment of procrastination was now a heavily stylised, neutralised interjection into Carroll / Fletcher gallery. Set against a sea of thoughts about the death of Margaret Thatcher, how brilliant cannabis is, or what someone deserved for lunch I felt the opposite of integration in a work. In past instances of London Wall, including one at Furtherfield gallery, tweeters have been contacted directly, allowing them to visit their tweet in its new context. A gesture which as well as bringing to light the personal reality of twitter and tweeters no doubt created a further flux of geotagged internet traffic. Another work, shown in tandem with London Wall W1W, is More Songs of Innocence and of Experience (2012). Here the kitsch backdrop of karaoke is offered as a way to poetically engage with SPAM emails. But rather than invite me in the work felt sculptural, cold and imposing. Blowing carefully on the attached microphone evoked no response.

The perception and technical malleability of time is a central theme of the show. Both, Flipped Clock (2009), a digital wall clock reprogrammed to display alternate configurations of a liquid crystal display, and Trooper (1998), a single channel news report of a violent arrest, looped with increasing rapidity, uproot the viewer from a state of temporal nonchalance. A switch between time and synchronicity, between actual meaning and the human impetus for meaning, plays out in a multi-channel video work Several Interruptions (2009). A series of disparate videos, no doubt gleaned from YouTube, show people holding their breath underwater. Facial expressions blossom from calm to palpable terror as each series of underwater portraits are held in synchrony. As the divers all finally pull up for breath the sequence switches.

According to David Auerbach, and with echoes from Thomson and Craighead themselves, Never Odd Or Even offers a series of Oulipo inspired experiments, realised with constrained technical, rather than literary, techniques. For my own reading I was drawn to the figure of The Time Traveller, caused so splendidly to judder through time over and over again, whilst never having to repeat the self-same word twice. Mid-way through H.G.Wells’ original novel the protagonist stumbles into a crumbling museum. Sweeping the dust off abandoned relics he ponders his machine’s ability to hasten their decay. It is at this point that the Time Traveller has a revelation. The museum entombs the history of his own future: an ocean of artefacts whose potential to speak died with the civilisation that created them. [2] In Thomson and Craighead’s work the present moment we take for granted becomes malleable in the networks their artworks play with. That moment of arising, that archaeological instant is called into question, because like the Time Traveller, the narratives we tell ourselves are worth nothing if the past and the present arising from it are capable of swapping places. Thomson and Craighead’s work, like the digital present it converses with, begins now, and then again now, and then again now. The arche of our networked society erupting as the simulation of a present that has always already slipped into the past. Of course, as my meditation on The Time Traveller and archaeology suggests, this state of constant renewal is something that art as a form of communication has always been intimately intertwined with. What I was fascinated to read in the works of Never Odd Or Even was a suggestion that the kind of world we are invested in right now is one which, perhaps for the first time, begs us to simulate it anew.

On second day of summer, Maja Kalogera & Med-i-kids from AKC Medika in Zagreb, will gather in Finsbury Park in front of Furtherfiled Gallery. They will present Classical Sitting Squatters. They are quite a joyful bunch, they recite, chirp, sing, blink, sit still, just name it. You are invited to join them/us for a drink and meet them in ‘person’, on Saturday 22 June 2013, between 11am and 5pm.

Classical Sitting Squatters (CSS) is an installation made of a dozen full-sized figures or ‘sitting’ sculptures. They are reciting poetry of Gertrude Stein, Dylan Thomas and Emily Dickinson, on the input of the passers-by.

Med-i-kids is an open group of street artists which connected in Medika, Zagreb. Their mission is to make public artworks to raise awareness and question the many dogmas present in Croatian society, the very same society positoned in third place as one the most courrupted countries positioned.

Maja Kalogera is an artist, curator and catalyst who consistently places herself at the convergence of art and technology. Born in Zagreb, she holds B.F.A. from School of Applied and Visual arts, Zagreb and M.Arch. from Architecture University, Zagreb. From 1999 she is member of the online collective wowm.org. Her creative work over the past 15 years has included a wide range of mediums: digital and interactive media, photography, painting, video and film. In 2005, she founded Center for synergy of digital and visual arts, a Zagreb based NGO, that provides her unique approach focused on synergy between traditional art media with new, digital media. In her own artwork she is interested in ways how people participate in physical and virtual spaces. Lately she started to collaborate with med-i-kids on socially engaged projects.

Opening Event: Seeds Underground Party – Sat 31 August, 2-5pm

Contact: info@furtherfield.org

Visiting Information

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

ABOUT THE ARTWORKS

ABOUT THE ARTISTS

EVENT: SEEDS UNDERGROUND PARTY

TALK: SHU LEA CHEANG – ART, QUEER TECHNOLOGIES AND SOCIAL INTERFERENCE

LOCATION

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

WATCH VIDEO OF THE OPENING

This exhibition by Mark Amerika (US) and Shu Lea Cheang (US/FR) at Furtherfield Gallery marks a significant moment for contemporary art. Amerika and Cheang are both ‘net native’ artists. They share many of the obsessions of the growing multitude of artists who have grown up with the net since the early 1990s.

They are also big “names” – internationally established artists who regularly show their work, to critical acclaim, at contemporary art galleries around the world. They have crossed over into the mainstream art world whilst maintaining a critical edge.

Amerika is a media artist, novelist, and theorist of Internet and remix culture, named a “Time Magazine 100 Innovator” in their continuing series of features on the most influential artists, scientists, entertainers and philosophers into the 21st Century.

Cheang is a multimedia artist who works with net-based installation, social interface and film production. She has been a member of the Paper Tiger Television collective since 1981 and BRANDON, a project exploring issues of gender fusion and techno-body, was an early web-based artwork commissioned by the Guggenheim Museum (NY) in 1998.

Both artists continue to shape and be shaped by contemporary networked media art cultures of remix, glitch, social and environmental encounters.

Shu Lea Cheang and Mark Amerika at Furtherfield Gallery provides a physical interface in a local setting in the heart of a North London park to the thriving, international, networked art scene.

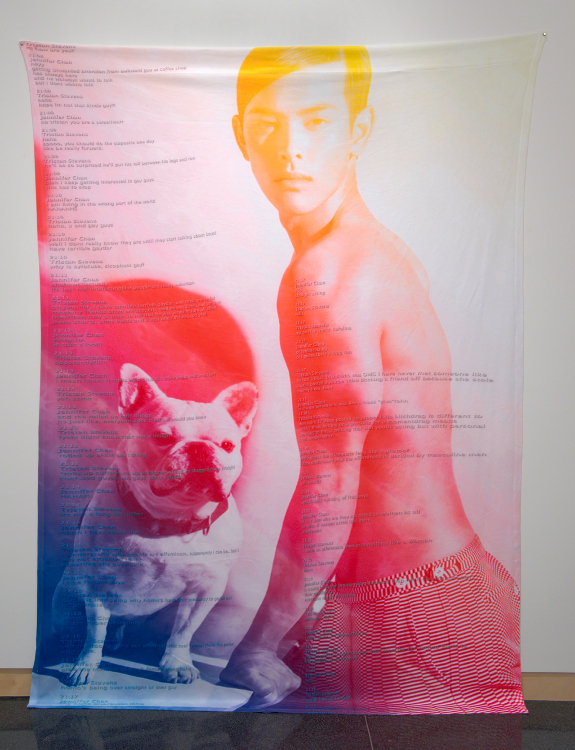

The exhibition features Cheang’s UKI viral love installation and Composting the Net. These are shown alongside pieces from The Museum of Glitch Aesthetics (MOGA), Amerika’s latest work in his collaborative series of transmedia narratives.

The exhibition features large stills from two performance installations. UKI viral love is the sequel to Cheang’s acclaimed cyberpunk movie I.K.U. (premiered at Sundance Film Festival, 2000) conceived in two parts – a viral performance and a viral game. The story is about coders dispatched by the Internet porn enterprise, GENOM Corp, to collect human orgasm data for mobile phone plug-ins and consumption. In a post-net crash era they become data deprived and these coders are suddenly dumped into an e-trashscape environment where coders, twitters, networkers are forced to scavenge from techno-waste.

![UKI – Trash Mistress [Radíe Manssour] (2009) by Shu Lea Cheang – Photo by Rocio Campana](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/radie.jpg)

In 2009, Cheang moved into the art studio at Barcelona’s Hangar medialab with 4 tons of E-trash, collected in Barcelona’s city recycling plant in one day. Amidst the rubble of wires, cables, boards, keyboards and computers, along with the coders and the hackers, UKI the defunct replicants are part of the e-trashscape seeking parts and codes to resurrect themselves.

UKI viral love is developed with collaborations and residencies at HangarBCN [artistas residentes] (Barcelona, Spain), Medialab Prado [Playlab] & [Desvisulizar] (Madrid, Spain) and, LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial [Plataforma Cero] (Gijón, Spain). The work presented at Furtherfield Gallery is the first physical installation of UKI in a gallery setting.

Composting the Net sources Internet net cultures’ accumulated data. It appropriates open (un)moderated mailing list communities, used for collaboration, sharing information and dialogue, and reprocesses the information into a virtual compost. For this exhibition Cheang composts the Spectre mailing list, a channel for practical information and exchange for media art and culture in “Deep Europe”, initiated in August 2001. The abundant info-data is reused and given extra life – an artistic legacy beyond its original purpose. It is also a celebration of the independent spirit of net culture that exists outside of corporate dominated Web 2.0 platforms such as Facebook.

Amerika’s The Museum of Glitch Aesthetics (MOGA) features the work of The Artist 2.0, an online persona whose personal mythology and body of digital artworks are rapidly being canonized into the annals of art history. The narrative traces the life of the artist and his ongoing commitment to a practice of ‘glitch aesthetics’. MOGA features a wide array of artworks intentionally corrupted by technological processes, including net art, digital video art, digitally manipulated still images, game design, stand-up comedy, sound art, and electronic literature.

Featured in the Furtherfield Gallery exhibition are three works from the MOGA series: Lake Como Remix, The Comedy of Errors and 8-Bit Heaven.

Museum of Glitch Aesthetics was commissioned by Abandon Normal Devices for the 2012 AND Festival.

In conjunction with Shu Lea Cheang and Mark Amerika exhibition opening, Furtherfield is pleased to host Shu Lea Cheang’s Seeds Underground Party on Saturday 31 August, 2-5pm. Join us for a seed exchange party where packets of seeds change hands and go underground in the fields around Finsbury Park.

+ More information about the Seeds Underground Party.

To coincide with the exhibition, on Monday 02 September The White Building hosts a special talk by Shu Lea Cheang who will be in conversation with curator and writer Omar Kholeif.

+ More information about the Event.

Mark Amerika

Mark Amerika’s work has been exhibited internationally at venues such as the Whitney Biennial of American Art, the Denver Art Museum, the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, and the Walker Art Center. In 2009-2010, The National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens, Greece, hosted Amerika’s comprehensive retrospective exhibition entitled UNREALTIME. He is the author of many books including remixthebook (University of Minnesota Press, 2011) and his collection of artist writings entitled META/DATA: A Digital Poetics (The MIT Press, 2007). Amerika is a Professor of Art and Art History at the University of Colorado at Boulder and Principal Research Fellow in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Science at La Trobe University.

Shu Lea Cheang

As an artist, conceptualist, filmmaker, networker, Shu Lea Cheang (USA/France) constructs networked installation and multi-player performance in participatory impromptu mode. She drafts sci-fi narratives in her film scenario and artwork imagination. She builds social interface and open network that permits public participation. Engaged in media activism with transgressive plots for two decades (the 80s and 90s) in New York City, Cheang concluded her NYC period with the first Guggenheim Museum web art commission/collection BRANDON (1998-1999). Cheang has expanded her cross-genre-gender borderhack performative works since relocating in Eurozone in 2000. Currently situated in post-net BioNet zone, Cheang is composting the city, the net while mutating virus and hosting seeds underground parties.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England.

This exhibition is sponsored by Rowans Tenpin Bowl, Carroll/Fletcher and Arts Catalyst.

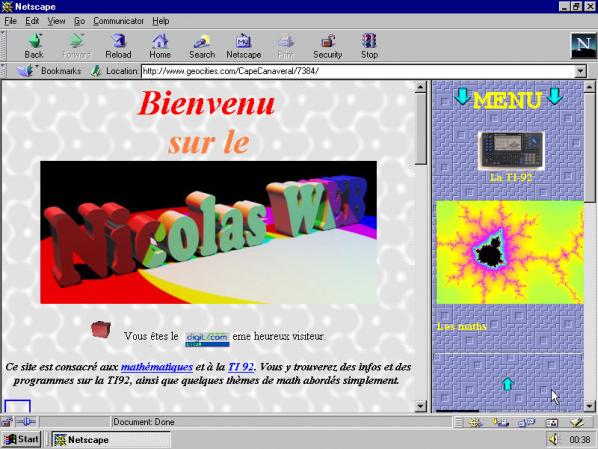

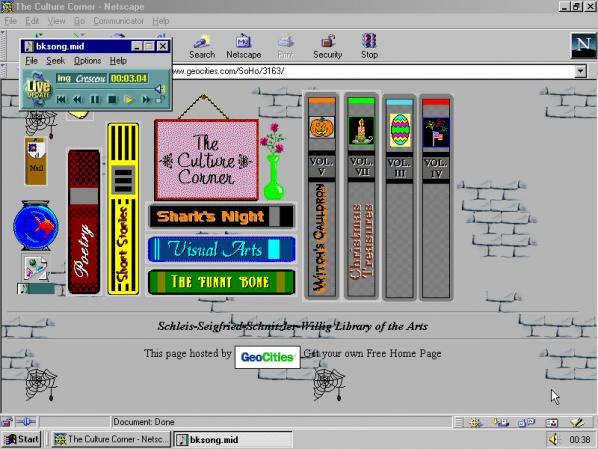

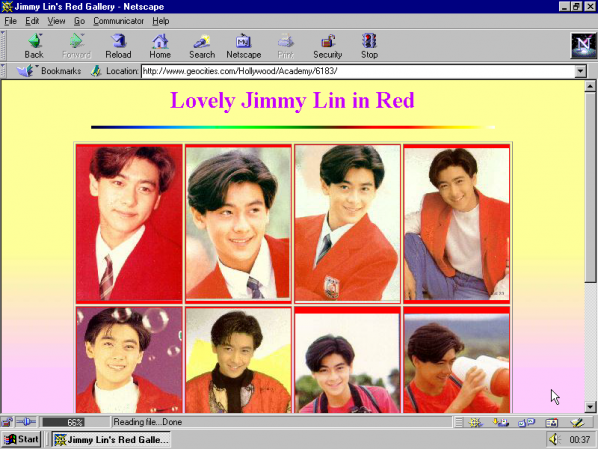

Featured image: A random Geocities homepage, last updated sometime around 1997

Daniel Rourke visits the Photographers’ Gallery in central London and reviews their latest exhibit One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age by artists Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied, on THE WALL. Over an eight week period (18 April – 17 June 2013) they feature a non-stop stream of video captures of what they term as the lost city and its archival ruins. A documentation of a past visual culture of the web and the creativity of its users with new pages changing every 5 minutes. The project provides a glimpse into web publishing when users were in charge of design and narration in contrast to the automated templates of Facebook, YouTube and Flickr.

Sifting through a dormant internet message board, or stumbling, awestruck, on a kippleised [1] html homepage, its GIF constellations still twinkling many years after the owner has abandoned them, is an encounter with the living, breathing World Wide Web. At such moments we are led, so argues Marisa Olson, ‘to consider the relationship between taxonomy à la the stuffed-pet metaphor and taxonomy à la the digital archive.’ [2] How such descript images, contrived jumbles of memory and experience, could once have felt so essential to the person who collated them, yet now seem so indecipherable, stagnant, even – dare we admit it – insane to anyone but the most hardened retro-web enthusiast.