This conversation follows in a series of interviews with women who work at the intersection of art and technology. As someone who works as an artist, curator, organizer, professor, researcher, and board member Sue Gollifer embodies this intersection across many venues.

Sue Gollifer has been a professional artist and printmaker for more than thirty years, Gollifer has exhibited her work worldwide and been collected by major international public institutions. A pioneer of early computer art, she has continuously explored the relationship between technology and the arts and has written extensively on this subject. Gollifer is a Principal Lecturer in Fine Arts and the University of Brighton where she is also the Course Leader of the MA Digital Arts Program. She has been instrumental in shaping major international arts communities including: the Design and Artists Copyright Society (DACS), the Computer Arts Society (CAS), and the College Arts Association, (CAA), ISEA, SIGGRAPH, Lighthouse Brighton, and many others. Gollifer is currently also the Director of the ISEA International Headquarters.

Rachel Beth Egenhoefer: Given the many hats you wear as an artist, curator, organizer, professor, many people describe you as many things… how do you describe yourself?

Sue Gollifer: I am an artist.

RBE: But you do other things too?

SG: I know I do. At the moment I’m more of a curator and an organizer, but at the end of the day I am still an artist.

RBE: How do you define your role as an artist in relation to being on the many board of directors you are on (such as ISEA, CAA, DACS, and others)?

SG: I’m not a theorist or in a senior management position but I think that these organizations need people who have a broad sense of the discipline to be on their boards to make sure that people like me and people like you have a voice.

RBE: So you see yourself as representing artists?

SG: Yeah, and I think the fact that I have a European background gives me a broader image as well. When I think about being on the board of some local organizations like Lighthouse or Phoenix in Brighton they value that I’m also part of an International network such as CAA and SIGGRAPH and ISEA. It’s quite reciprocal too. The bigger organizations value my spectrum.

RBE: What do you learn as an artist from doing all these other organizational things?

SG: I think what it does is it starts me making work. It’s like any of those things. But I think it started off when I was a consultant to Higher Education in the UK and I just got used to facilitating and networking and telling people about things. And I realized I was really quite good at that.

RBE: Networking?

SG: Yeah. But not just networking. I organize a lot of mailing lists, where I act as a kind of filter for people, letting them know about events and festivals, and ideas that are going on.

RBE: So given that you work in all of these roles, as an artist, as an organizer, as a filter, what changes have you seen over the years of working in these fields?

SG: Well, technologies have changed our lives with the Internet and mobile phones. You know I travel a lot, but half the time people don’t know that I’m not really there, because I still do what I’m doing somewhere else. Where you are doesn’t really matter. You still kind of function, which has its good points and its bad points really, cause you’re always on call.

RBE: What about changes in content or questions that people are asking? Either in art practice or education or conferences and festivals, have there been any changes?

SG: I think the reason why ISEA is successful is because, although we all have our distributed networks and we’re always in constant touch, I think the act of physically bringing people together is really important. But I do think also that a lot of the organizational things like content management systems and the ways that you hear about various festivals and things is made so much easier. At the same time there are so many of them. It’s really important with my ISEA hat on that I’m thinking about the “un-conference” and that you don’t get stuck in a rut. There is a changing landscape and environment and you need to keep up with that.

But with my educator’s hat on, thinking about PhDs and research papers, there’s a lot more to do with money and research and getting money from science backgrounds now. But the idea of research gets lost. What they value is that people are writing about stuff, they’re not actually doing it, but writing about it, using research as evidence.

RBE: What is the role of research in art?

SG: I don’t know. What do you think? Do you think it’s the work? Do you think it’s making the work?

RBE: Well, I think research can inform the work, and work can inform research. But I think the point you brought up about research and the sciences and the value of it, it seems like it can become problematic when it is seen as a moneymaker. Or when the purpose of it is to get money and not the purpose being to inform the work.

SG: Yeah, I was involved in a science project and there was a lot of money in it and they obviously valued the significance of the artists being in there but really you have to fit your research around the money rather than the other way around. It just got out of sink.

RBE: Does that map at all on to how conferences and festivals are set up? Does the work dictate what will be at the event, or does the event dictate what will be made by artists?

SG: Well, to get back to the research thing. Research as evidence of something, even if you are putting work in an exhibition or putting work in a paper or something, you still need evidence.

RBE: But as far as themes or content, how is that dictated? For example the upcoming ISEA is all about “Machine Wilderness”. Was that a result of artists making a lot of work in that realm and we should have a festival about it, or do you think that it was a decision to have a festival about this and encourage artists to think and make work like this?

SG: Well when people put in a bid to host ISEA, they put in what they think the nature of what ISEA will be about. Obviously when we look at proposals we look at not only the relevance but also the integrity of the people delivering it. “Machine Wilderness” in this case is very much around the themes that Andrea Poli is interested in. The theme of ISEA in Istanbul was “Contained/ Uncontained” which was similar but also a bit broader.

RBE: How do you see the differences in cultures influencing different ISEA’s? ISEA purposely has the festival in different cities around the world, how does that influence the work or the field or what people are thinking and doing?

SG: Well if you take the case of the ISEA in RUHR, Germany, it was to do with the Creative Industries, and creating awareness of new industries. You know we come in and inform people about new things. There’s the idea that we can change things. Or bring things to a city in a way of education and outreach. It shouldn’t be just us sitting in a dark room talking to each other.

RBE: So you see it as a way to bring new media awareness to these different cities?

SG: Yeah.

RBE: But then what do the artists and participants get in return? Or what does ISEA get in return?

SG: You get to travel and meet people! I think you get a different perspective.

We did have two bids coming through for ISEA2014 from Zayed University, Dubai, UAE and Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, BC. Recently the ISEA Board agreed that the Dubai bid, with its focus on the burgeoning field of art and technology in the Arab World would provide a unique opportunity for ISEA to connect audiences and artists from the Middle East with the international electronic art community.

A strong aspect of the bid was the focus on women’s education and ensuring that young women have the potential to influence the future of the region and develop international contacts.

I hope that ISEA can leave a legacy somewhere. I mean otherwise we might as well just have it over Skype calls. The overarching theme of ISEA2014 ‘Location’ will explore strands such as Technology; Science & Art East Meets West; Emerging Economies/Emerging Identities; Nomadic Shifts and Digital Archaeology and Collaborative Spaces.

RBE: This interview is part of a series of interviews with women using art and technology. What do you think is important in having a female voice in today’s art world?

SG: I talk to my students about my role and my job and things like that, and my female students think that it’s really great that I run a digital arts course. If I were a man it would be very very different. I think it’s equally important that students aren’t just taught by women, but women of all ages, those that are married, not married, children, no children. I think we do have to establish role models to a certain extent.

I was a feminist in the 60s and 70s but I never thought that we should be different. I just wanted to be accepted for who I was really. That might be a bit anti-feminist, but I always fought for women for education and opportunities. This goes back to the Dubai thing to a certain extent, the university there started off because one of the princesses wanted to learn about art but there was no place to do so. So it started and went on to have a validated degree. And maybe one day it will have a masters program and women can apply for scholarships and travel abroad?

RBE: Do you think it’s important to have “Women Art & Technology” as a separate category? Or should it just be “Art & Technology”?

SG: Art and Technology.

RBE: Aside from being a female role model for your students and talking about the female voice, what else do you think is important for your students to know right now or learn right now?

SG: Code! (laughs) But I don’t like to think we’re bringing them up differently?

RBE: Or even taking gender out of it, what do young people need to know?

SG: They need to be aware of things. But it depends on what they are trying to do and what direction they want to go in… A big thing is confidence. A lot of my women students do lack confidence.

RBE: Why do you think that is?

SG: I don’t know what it is.

RBE: So what do you do to boost their confidence?

SG: I give them a voice. I give them a space and an opportunity in the class.

When I used to do interviews for undergrad programs in Printmaking, it always started off that the women had better grades, better portfolios, better skills, but at some point it switches. And they loose that confidence and that voice. I don’t know what it is really.

Do you find that?

RBE: The program I teach in has a majority female students. I think that it might be easier for them. I do wonder though sometimes if they are more confident when they are in a classroom with me verses one of my male colleagues or just a different background. But I think there’s also the other end of the spectrum where they are overly confident because they are growing up in this world where you have to be liked constantly on Facebook. You know, like me, like my image, like me, like me, like me… They need to be constantly validated and that spirals into “I’m amazing”. But those aren’t the ones who are asking the tougher questions; those are the ones who want to be liked.

SG: There’s another aspect. Maybe not about confidence, but I think there’s a smoke and mirrors element. There are some men that seem to have all the jargon without actually any credibility. And the women I know with credibility don’t necessarily tell everyone that they do it.

RBE: There are actually studies about that, and how male and female brains are wired differently to behave differently.

SG: I think they address issues in a different way.

RBE: What are you working on now?

SG: Alan Turing!

RBE: What is your role in the Turing Project?

SG: I’m putting together with Anna Dumitriu the exhibition ‘Intuition and Ingenuity’, a group exhibition that explores the enduring influence of Alan Turing – the father of modern computing – on art and contemporary culture. 2012 will be the 100th anniversary of the birth of Alan Turing, one of the greatest minds Britain has produced; the world today would have been a very different place without his ideas.

I’m also curating a projected drawing Exhibition for the Drawing Research Network (DRN) conference in Loughborough in September.

I have also just been part of selection partnership for two newly commissioned pieces of work for Brighton Festival, ‘Sea of Voices’, and ‘Voices of the SEA’. Plus reviewing work for SIGGRAPH art gallery 2012 and for ISEA2012, and papers for the journal ‘Digital Creativity’, of which I am assistant editor.

RBE: What excites you about the future?

SG: I don’t know really. I hate to get gloomy about the future, but I do think it’s going to get worse. I mean you live in San Francisco and I live in Brighton so I don’t think it’s hit us quite yet, but I am starting to notice a lot of shops closing. And I know that things I took for granted like buying a house, having children and having a job, I don’t think they have these choices anymore.

RBE: How do you think this will impact the art community?

SG: There are surprisingly good opportunities for the use of vacant shops and offices for exhibition spaces and studios and surprisingly people buy art because they think it’s an investment for the future.

RBE: Do you have anything else you want to tell the Furtherfield readers?

SG: I think it’s going to be interesting and exciting in the future, despite all this, I think it’s going to be exciting to see what comes next.

Other interviews in this series:

Woman, Art & Technology: Interview with Lynn Hershman Leeson By Rachel Beth Egenhoefer

Women, Art & Technology: Interview with Sarah Cook

Sign up: ale[at]furtherfield.org

To accompany Invisible Forces, Furtherfield invites all gallery visitors to take part in a programme of public play, games, making and discussion led by alert and energetic artists, techies, makers and thinkers: Class Wargames, The Hexists, Dave Miller, Olga P Massanet and Thomas Aston.

Saturday 23 June 2012 – 1-5pm

Summer Board Games and Picnic with Class Wargames and Kimathi Donkor

Saturday 30 June 2012 – 1-5pm

Summer Board Games and Picnic with Class Wargames

Wednesday 04 July 2012 – 9-11am

3 Keys – The River Oracle – The Hexists

as part of Moving Forest by AKA The Castle

Wednesday 11 July 2012 – 11-5pm

Technologies of Attunement – Olga P Massanet and Thomas Cade Aston

Saturday 21 July 2012 – 2-5pm

Dave Miller’s Finsbury Park Radiation Walk

It’s a bizarre thing when you stumble upon the “new art movement” filtering through discursive chatter. Is it actually a movement, or is it simply a bunch of like-minded individuals telling me its a movement?

Behold The New Aesthetic then – a new art meme in visual culture whimsically constructed by James Bridle, which manifests itself in a Tumblr blog, a presentation for Web Directions South, Sydney and an original blog post. Recent attention to it has reached feverish proportions coming off the back of a SXSW panel in March and a generally positive endorsement by Bruce Sterling in Wired, plus some group responses on the creators project. More recently, the computational media scholar and philosopher Ian Bogost has posted his own thoughts for The Atlantic.

As a meme should do, “the New Aesthetic” has fulfilled its role – it has a lot of people talking about it. Like any meme which dices visual culture with some sort of research element, it has artists, writers, even media and aesthetic scholars measuring their own opinions on it in rank order without anyone knowing exactly where it’s going, what it really is or who exactly is doing it. In our noisy and crowded “I can’t believe I got 50+ retweets” over-networked epoch, this is quite an achievement even if you don’t take it that seriously.

But here’s the question: can the new aesthetic be more than a meme? More to the point, does it want to be? Is it capable of a direction? Can it be serious?

That said (and as Bridle avers) this isn’t really a prominent “movement” of ideas as such. Neither does it present material which it would deem ‘arty’. Instead, it’s an extremely broad and oblique orientation which seeks to document the subtle (and sometimes explicit) changes within our information saturated existence. It simply contextualises the contingent manifestations of computational activity, and how they are reversing and revising computational and human activities back in on themselves. Bridle’s tumblr simply presents the new aesthetic for what it is, much akin to perusing through pictures in a Facebook profile, a Reddit top ten list or clicking on Stumbleupon – simple snapshots of “stuff” which echo a blurring between the world of networks, machines and everything outside of it (with a particular emphasis on where it goes a bit wrong, hence a certain infatuation with glitchyness). Quoting Bridle’s Tumblr page;

“It is a series of artefacts of the heterogeneous network, which recognises differences, the gaps in our overlapping but distant realities.”

In another video presentation ‘We fell in love in a coded space‘ at Lift12, Bridle terms this ‘network realism’ – instances where the amalgamation of computational networked activity blurs with non-computational activity, to such an extent that it reduces any observer to nothing but a curious, passive node, gleefully whittling through instances of vaguely creative stuff. For Bridle, this occurs not just in industry but also architecture, finance, storage, fashion and now an attempt at aesthetic understanding. It’s an infatuation with the alterity of bots, algorithms, pixels and realised fictions. In this presentation however, Bridle is largely concerned with how one can respond or understand the ‘desires’ of bots, unaware that anthropomorphising the situation may not reap the rewards required. In this interpretation the new aesthetic is charged with the task of asking how we can think and orient ourselves computationally, whether it be designers, thinkers, writers, scholars or artists.

Sterling himself, mostly issues praise with a pinch of amusing impatience, as if the New Aesthetic movement should progress faster than it actually is doing, with more ideas and more focus. Kyle Chayka states that artists are already embracing it as a ‘contextual seedbed, rather than a label’. Jonathan Minard understands it as a new method of reflection concerning cultural tool-making, where the ‘dumb tools’ of machinic interface scream images back at us.

Digital Humanities scholar David Berry has blogged a similar view echoing that the new aesthetic is tapping into what he calls ‘Computationality’, a historical paradigm frame-making of sorts, which constructs specific meaning-making practices. Visualisation revolves around processes and patterns and so the list making exercise of Bridles’s Tumblr blog would seem apt in this regard, as it issues unparalleled amounts of pattern making not just as content, but as form. The archive is a jamboree of other pattern recognising events; security face recognition, retro 8bit encapsulation, satellite visuals and generally messing about with an Xbox 360 Kinect. James George mentions something similar but suggests that the new aesthetic should question the critical distance between artistic activity and technological use. It resembles a massive screen dump from a digital artist’s delicious account. Quoting Bridle again in an interview with The Design Observer Group;

“The New Aesthetic is not criticism, but an exploration; not a plea for change, rather a series of reference points to the change that is occurring. An attempt to understand not only the ways in which technology shapes the things we make, but the way we see and understand them.”

To most of the established readers here, it’s easy to criticise the “newness” of the New Aesthetic, in the same way the 90’s trope “New Media” has been quickly bundled away as if it never existed (Marius Watz makes this point). For those of you who have been studying such issues concerning hacking, play, enumeration, collecting, remixing, glitch-ing, (see Rosa Menkman in particular) in the broader realm of the computational arts, there really isn’t anything novel to gawk at: this is more of a rearrange or a rebadge. Indeed, internet discussion has been rife with such criticism, from the triteness of using Tumblr as the ‘official site’, to quick dismissals concerning the New Aesthetic’s distinct lack of any historically serious ‘substantial practice’ – not that it wanted it in the first place (Indeed it’s a pity that it has contingently replaced an identical term for a movement unrelated to Bridle’s own, coined by arts writer Michael Paraskos and realist artist Clive Head. Moreover, depending on how one looks at it, Paraskos and Head’s own movement has similar views espoused by Bridle’s version, including perhaps a direct opposition to conceptualism and foregrounding art as a material practice).

If Bridle were not so sincere about the whole affair, one would be mistaken that this was a too-cool-for-school strategy straight out of a Nathan Barley episode. But thats an easy misread. As Bogost states, Bridle is just curious about the weirdness of the network we all rely on and revel in. But there is a point where fascination with creativity turns into ADHD. The New Aesthetics tumblr site, already does just that, without any hint of standing still. “What’s going to come next? What can we do next? What are the limitations? What happens if I click that? What is that doing there?”

However both Bogost and Greg Borenstein issue a different view about the new aesthetic. They both discuss it in relation to a recent trend in philosophy called Object Oriented Ontology (OOO), a movement to which I am extremely sympathetic to. Bogost explains OOO succinctly enough;

“If ontology is the philosophical study of existence, then object-oriented ontology puts things at the center of being. We humans are elements, but not the sole elements of philosophical interest. OOO contends that nothing has special status, but that everything exists equally–plumbers, cotton, bonobos, DVD players, and sandstone, for example. OOO steers a path between scientific naturalism and social relativism, drawing attention to things at all scales and pondering their nature and relations with one another as much as ourselves.”

The link to OOO is fairly self-evident. If one of the most prominent aspects of the new aesthetic is an obsession with how a machine “sees” the world, OOO is a commitment to the seeing of things in widest possible sense. But while Borenstein generally aligns OOO to the new aesthetic with exuberant equivalence, Bogost’s view is one of general optimism, but not broad acceptance. For a start, the new aesthetics is based on a continual divide and repair between two opposing realms; the physical and the digital, each coming together and breaking apart endlessly, like throwing a box of magnets.

One of the main stipulations of being an OOO advocate is the realist eruption of what counts as a thing, and how that thing contingently relates to different types of entities. This is why Bogost decenters computation in the new aesthetic, and emphasises the multitude of things that escape the physical/digital divide. Their adventures are always-already strewn across the ontological landscape. One of the other main stipulations involves us lacking secure knowledge in fully understanding discrete units on their own terms – we can never experience their being in the same way we experience our being.

If one has read Bogost’s latest publication, Alien Phenomenology (and if you haven’t, I’d urge you to do so immediately), one would understand Bogost’s view that the new aesthetics misses out not just speculating on the hidden lives of objects other than computers and humans, but it also hovers on the inescapable problem of anthropomorphising machines and objects to within an inch of their lives. The alien aesthetics challenge is provocative.

“[T]his Alien Aesthetics would not try to satisfy our human drive for art and design, but to fashion design fictions that speculate about the aesthetic judgments of objects. If computers write manifestos, if Sun Chips make art for Doritos, if bamboo mocks the bad taste of other grasses–what do these things look like? Or for that matter, when toaster pastries convene conferences or write essays about aesthetics, what do they say, and how do they say it?”

There is an interesting discussion to be had in OOO about the usefulness of anthropomorphising the infinitesimal non-human relationships between the properties of things. Whilst others (including Bogost) see it as an inevitable factor of being one finite human entity amongst a crowd of other finite entities, I see it as a hinderance.

In particular, I’m interested in the way the new aesthetic never manages to access computation ‘just’ as it is. It only takes computation seriously when it functions as a qualitatively intelligent system, which meets or surpasses rational intelligence, or, it directly flips into “dumb tools” of (mis)communicative manipulation for the whims of human mental acts.

But I digress. Last year Bridle released a book called “Where the F**k Was I?”, which accurately sums up the mentality of the movement. The really interesting element of the new aesthetic is that it presents genuinely interesting stuff, but Bridle’s delivery strategy is set to ‘gushing disorientation’. At present, it’s the victim of the compulsive insular network it feeds off from. It presents little engagement with the works themselves instead favouring bombardment and distraction. Under these terms, aesthetics only leads to a banal drudgery, where everything melts together into a depthless disco. Any depth to the works themselves are forgotten.

Memes require instant satisfaction. Art requires depth.

Featured image: ‘Promised Land’ design of transmediale 2k+12

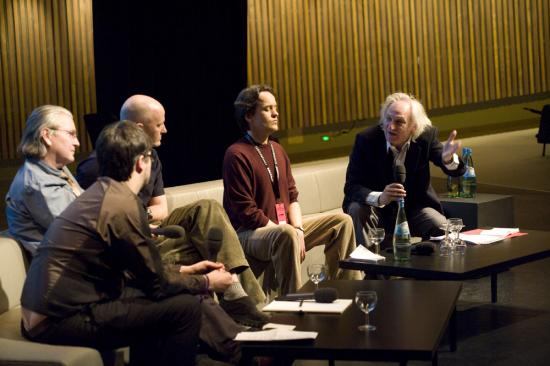

Everything is not connected was the title of one of the talks organised as part of the in/compatible symposium at transmediale 2k+12 (2012), precisely the keynote speech of Graham Harman for the section titled systems. But this year’s programme of transmediale was all about connectedness, or I’d better say, about a curatorial structure of connectedness and subtle linkage.

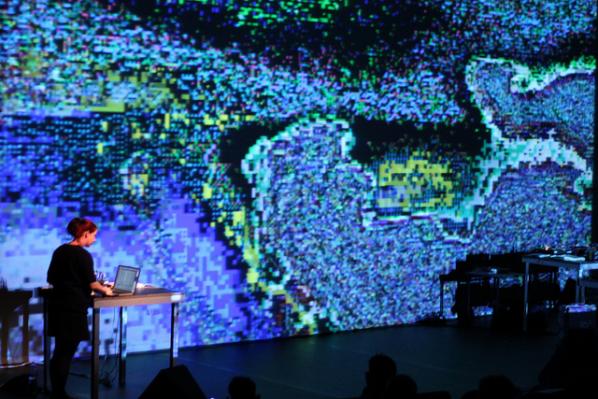

The festival’s format was one of visual and conceptual reminders, and this became evident at the very beginning and during the opening ceremony, in the auditorium of the the Haus der Kulturen on the 31st January.

At the moment of opening a power point presentation, the new artistic director Kristoffer Gansing seemed to experience a technical problem as his file would not open. A technical assistant was then called on stage to fix it, and while we all giggled and looked at each other thinking that this was somewhat like a paradox for a festival devoted to the exploration of art, technology and media culture, we soon realised that the dooming technical failure was a pretext for one of the Prepared Desktop performances by glitch-artist jon.satrom.

Thus, from the very start, we experienced what Gansing often defined as a festival which “is an incompatible being”, suggesting that the 25th edition of transmediale would be different, perhaps more oriented to a multidirectional engagement with its audience and, surely, aimed at making us aware of how much technology is intrinsically part of our everyday lives – physically, mentally and also politically. It seems that Gansing had worked towards making us feel like explorers in order to experience what he described in his curatorial statement as the “in/compatible moment”, the “moment of stasis” resulting from the clash between things that were supposed to flow and converge peacefully within a system. That unforeseeable clash generated by an incompatibility which, according to him, is to be seen (and perhaps also sensed) as a moment full of potentials, as a gap which allows a new rearrangement of the elements of a given system – be it artistic, social, economic or political.

This ‘curatorial tactic’ marked the rich programme of transmediale 2012, which spanned from exhibitions to academic research networks, from online artistic interventions to talks and live performances – worth a mention is also the overall design of the festival’s contextual material, called the Promised Land design theme, which with its retro digital-pop aesthetic [1] seemed to have been devised to reinforce the idea of the clash, the tensions at work within the notion of technological convergence (“the myth” of contemporary society), starting from the very aesthetics of it.

The connectedness I mentioned above is very tangible when looking back at the main themes discussed at the in/compatible symposium – which was divided into three thematic segments:

systems, publics and aesthetics – in that they could be found as extensions across the whole programme, which in turn was developed across six sections:

1- the exhibition Dark Drives. Uneasy Energies in Technological Times curated by Jacob Lillemose

2- The Ghost in the Machine performance programme curated by Sandra Nauman

3- the video programme Satellite Stories curated by Marcel Schwierin

4- 25 Years, a series of events, amongst which talks and video screenings, about “areas of conflict between old and new” that were devised to mark the 25th anniversary of the festival

5- Featured Projects, a series of special parallel projects, such as web-based and site-specific

interventions

6- last but not least, the new addition of reSource for transmedial culture, an “interface between the cultural production of art festivals and collaborative networks of art and technology, hacktivism and politics” presented as a series of ongoing events (workshops, discussions, lectures and performative interventions) curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli.

Taking a step back to look at the overall thematic framework of the festival before digging into the specifics of each programme, what should be emphasised is the effort that was made to strengthen the transdisciplinary nature of the festival as a whole. In fact, each section of the programme inserted itself into the wider discourse of cultural production; putting a stress on how deeply technology is intertwined with the every day while looking at the relationship between art and technology from a socio-economic and political perspective that was permeated by an historical orientation. And the latter is precisely what makes this 25th edition different from those I had experienced before.

Gainsing’s perspective – as it was often stated by his collaborators throughout the festival – is that of a media archeologist; and in this sense he occupies a specific place in the media theory-scape of the city of Berlin, which houses the Institute for Time Based Media (Berlin University of Arts) where Siegfried Zielinski is the Chair of Media Theory. As many might know, Zielinski is the theorist who coined the term (or better still, founded the field of) media archaeology with his book Deep Time of the Media (MIT Press, 2002). I would then say that the methodological approach of the artistic director, as well as that of the four festival’s curators, was the one which looks at a present “linked to a past pointing at a possible future”, adopting a perspective that is different and finds “something new in the old” rather than seeking “the old in the new” (quotes from Zielinski, 2002). This is probably the reason of the festival’s holistic character, of the existence of critical and aesthetic linkage between the various panel discussions and performances, research projects and art installations.

This year’s symposium, across three different but converging angles, looked at the tension between functionality and disruption in order to address how the gap existing between the two has been (and could be) “productively used” by artists, as well as by society at large, in relation to available technology – mostly digital and web-related.

The strong connection existing between all panels – grouped under systems, chaired by Christopher Salter; publics, chaired by Krystian Woznicki; aesthetics, chaired by Rosa Menkman– was given by the historical approach of their explorations into the present. Their positions were those according to which it is not technology that impacts society, but it is almost the reversal: it is society – and artists – who, with their behaviours and actions, transform it, generating a new language and new possibilities within established systems, or failing systems. One way to embrace this type of perspective was described by Graham Harman in his keynote speech: it is through differentiating “between background and foreground” and bringing the latter “into consideration”, through accepting obsolescence as something inherent to the state of the technological thing and through embracing the fact that mediums change, that new ways of thinking and understanding reality can be established.

In this regard, the in/compatible aesthetics panels brought about interesting paradoxes in relation to media archeology and technological historicism, such as the necessity to move away from nostalgia for the past and avoid what could perhaps be termed as techno-romanticism. Through a series of panels, spanning from Uncorporated Subversion. Tactics, Glitches, Archeologies to Unstable and Vernacular. Vulgar and Trivial Articulations of Networked Communication, this section of the symposium presented a variegated array of artistic and research practices (from artist Olia Lialina to media theorist Jussi Parikka) that are concerned with establishing methods for challenging given systems, their codes and protocols, in order to establish new languages and modes of operation. All of them presented different artistic scenarios embedded in current socio-cultural frameworks, stressing the fact that “cultural history is shaped by users more than its inventors” (quote from artist and programmer Dragan Espenschied‘s presentation during the Unstable and Vernacular panel).

The publics section dealt with “forms of activism and social resistance” that emerge from incompatibility with the economic-political systems. In the instance of the Norifumi Ogawa in his talk Social Media in Disaster, during which he gave a very detailed insight into the “productive and effective” uses of social media during the recent Japanese earthquake and the consequent accidents at the Fukushima’s nuclear plant.

According to the exhibition curator Jacob Lillemose, Dark Drives “explores the idea that uneasy energies exist in technological times” and offers “a thematic reading and an historical mapping of the last fifty years, expressing a critical attitude to existing phenomena as well as exploring possibilities of reinvention”. And it does so with “no promise of overcoming” them (quotes from Lillemose’s curatorial statement).

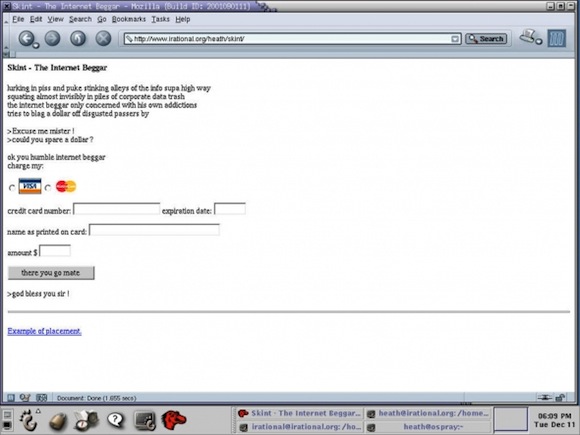

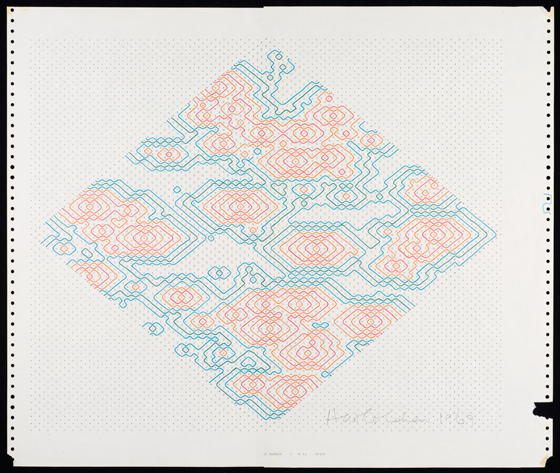

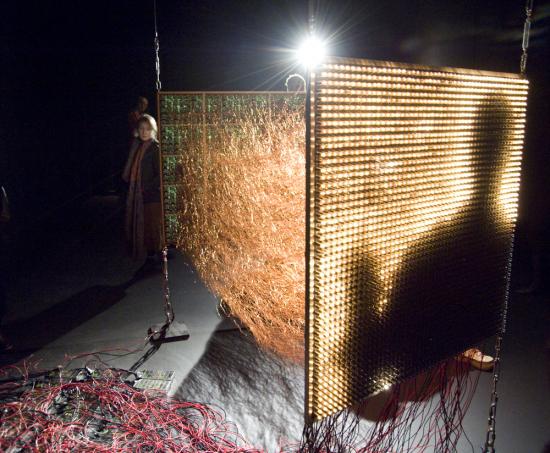

In fact, the exhibition included works by 36 artists spanning different cultural fields as well as periods. The inclusions ranged from Ant Farm’s Media Burn, Chris Burden’s Doorway to Heaven and William S. Burroughs/Antony Balch’s The Cut-Ups (late 60s and 70s) to Art 404’s 5 Million Dollars 1 Terabyte, Constant Dullaart’s Re: Deep Water Horizon (HEALED) and jon.sotrom’s QTzrk (2010/2011), all while moving through the practices of artists attached to the net.art movement, such as Heath Bunting’s Skint – The Internet Beggar and JODI – the latter with a new light installation, LED PH16/1R1G1B, dated 2011–. Included were also works produced in the 80s by music bands like SPK with their Information Overload Unit. Not only, but the show also presented works which are usually not associated with the conventional art circuit, such as the TV programme Web Warriors produced by Christopher Zimmer (2008) and the music video Come to Daddy by Chris Cunningham/Aphex Twin (1997), along with, as a reversal, old(er) media-oriented work, such as the series of computer prints Leaves by Sture Johannesson, which can be read as early pieces of conceptual art.

This condensed list is to say that the amount of artistic and cultural material on display in the exhibition and the trajectories that it opened were broad to such an extent that Dark Drives functioned more as a general narrative survey than a show with a clear proposition. It was a survey of how uneasy energies might materialise as consequences of the modes and methods in which technology is used and understood, with no much distinction drawn between technology in electronic, computational or digital times.

Dark Drives did not aim to address further its initial statement, nor to narrow down the kind of relationships (and their reasons) between historical instances and contemporary ones; and from my perspective this was its flaw. However, this is the kind of exhibition that a festival like transmediale eventually needed, because to my knowledge this sort of display and curatorial approach had not been presented before: an exhibition which finally embraced the inclusion, with no hierarchies or differentiation in terms of choices of display, of works conventionally shown in gallery spaces along with those traditionally related to (ahem) the still-existing ‘niche of new-media experts’.

Dark Drives might not be a very daring exhibition if placed outside the context of a media art festival like transmediale, but it is certainly almost subversive in this context, and in comparison with its precedents. The exhibition installation was clever and atmospheric and, as it was for the festival’s format, it was dotted by visual and aesthetic reminders. I’ll give you an example amongst many and various ones that you could have spotted in the show: formulas by Peter Luining (2005), which is a video about manipulating a screen-grabbed image in Photoshop till it becomes a black screen, was shown just a work before jon.sotrom’s Qtzrk (2011), another video based on the process of image deformation – in this case through the use of QuickTime 7; the latter, was, in turn, shown just another work before Heath Bunting’s Skint – The Internet Beggar (1996), a website that operates as a service through exploiting the potentials offered by the network system. The three works all adopted the framework of computer desktop as a display platform for their artistic interventions, but also as a production space. And although each artist’s agenda and research area were different, their proximity made these distinguishing elements more evident, highlighting various ways of activating modes of production that diverge from those of the system within which these artists operate.

Similarly to what I have just described, it was Dark Drives as a whole that guided the visitor all the way through its display towards specific thematic directions, which were suggested by the installation in conjunction with the many visual and aesthetic links. But simultaneously, the visitor would also be free to follow the other and many trajectories arising from the content of each specific work, and this flexibility made the exhibition an attractive narrative territory ready to be employed for further explorations.

This section of the programme has been devised as an ongoing project by curator and researcher reSource is an initiative that started before transmediale festival with the gathering of an international network of PhD researchers for a conference and workshop held at the University of Arts in Berlin last November. The outcome of this collaborative network was launched on the second day of the festival, in the form of a research newspaper titled World of the News – Thank you & Goodbye . This newspaper operates as a platform in which an array of researcher, most of whom practising artists, presented a series of essays and interviews looking at the “unresolved questions and paradoxes of media technology” and how they might impact (and redefine) not only artistic production but also research processes and academic conventions, such as peer-review systems or the definition of what is currently accepted as ‘proper research’ within the academia.

World of the News gathers a very well-thought through research material, and it does challenge academic formats, bringing forth the necessity (and preciousness) of collaboration and dialogues across disciplines, forms and formats.

The above is only one of the activities that were part of reSource; in fact, its programme was divided into five different sub-themes, Methods, Activism, Networks, Markets and Sex, each of which ranged from panels to presentations and workshops.

One of the proposed panel was titled Coded Cultures – Sub-Curatorship Beyond Media Arts and drew on a previous event organised by the group 5uper.net in Vienna, Coded Culture: The City as Interface (2011). Although aimed at addressing questions about curatorship and media art festivals, thus the public sphere, I wonder why curatorship as a practice within the field of new media and, supposedly within what was termed as “beyond new media art”, were not discussed more in depth, especially given the changes that transmediale exhibition itself proposed. If Joasia Krysa presented her specific approach to curating as a system that is informed by technology and thus embraces its inherent systems, like software codes and protocols of Internet and digital technology, in order to change the hierarchy of power; the other invited curators seemed to lack a depth in the discourse. The whole panel unfortunately stranded in general statements such as “technology changes the role of the curator” or “the curator does not want to define itself as a curator anymore, but as a coordinator and a producer”; a cliched conversation that – opportunely – ended with Krysa throwing on the table of discussion Christine Paul’s definition of “curator as filter feeder”.

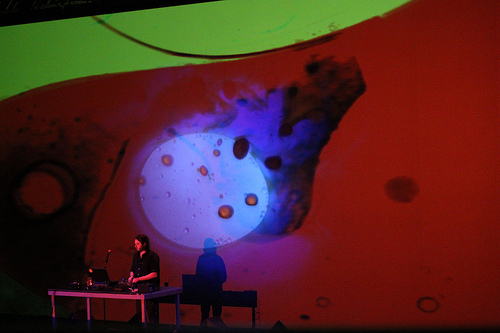

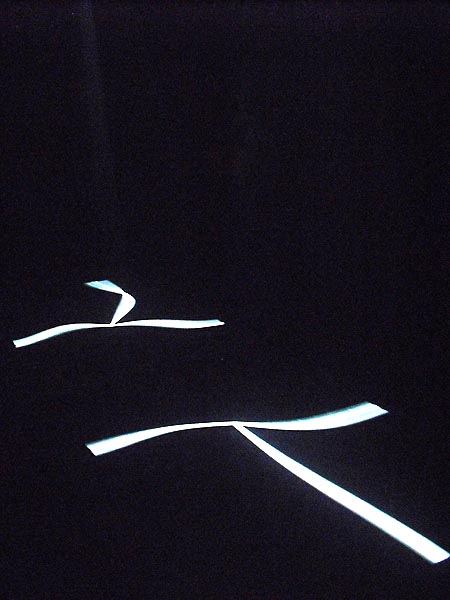

Many other were the events presented at transmediale, such as the visually stunning, and purely analogue, performance of Joshua Light Show for the The Ghost in the Machine performance programme . At different times during the week of the festival Joshua Light Show performed with different musicians, such as the one man band Oneohtrix Point Never, bringing to light the beauty and magic that old(er) media can (still) give to a public of a “transmedial” festival.

As a final round-up, it is also to be noticed that in/compatible embraced slightly more extensively the sphere of online production and distribution, specifically in conjunction with the 25 Years, Satellite Stories and Featured Projects programmes.

If when browsing the transmediale website you experience some strange episodes, such as pages merging into each other when scrolling up and down, that is because of a site-specific intervention by Danja Vasiliev and Gottfried Haider – the developers of a Content Manipulation System called HOTGLUE which allows to construct websites directly in a web-browser.

Also as part of 25 Years there was a video installation <collaborative documenting / archiving on netart.activities> initiated by artist Constant Dullart and art historian and artist Robert Sakrowski. The duo had devised an open database system which employes YouTube as a repository for net.art projects. This project tackles issues related to hardware and software obsolescence in relation to the (often impossible) access to early net.art projects, and proposes a way of archiving them by filming an ‘audience-in-action’ during the browsing; a strategy which is also useful for tracking users’ behaviours and thus highlight the changes brought about by technological development. Dullart and Sakrowski also led a workshop at the transmediale headquarter, as well as presenting their work during the panel discussion web.video the new net.art?.

As a last mention, the video programme Satellite Stories was launched at the opening night with Screening Re-enactment Videospiegl, a looped video screening which connected the present of the festival with its history, its archive. In fact the festival first opened in 1988 as VideoFilmFest, and the Videospiegl selection of early videos is now accessible on transmediale website; hopefully marking the start of an archive which will be online and for all.

The online activity described here is certainly not enough for a festival like transmediale, which should investigate thoroughly the relationship between art festivals, artistic production and online distribution; but at least it seems a start for what is a much needed new exploration to be carried out by the organisers.

There is one more issue that I feel was only and often superficially addressed by this edition of transmediale. There were many mentions, in theory, of capitalism and its ramificated systems, such as the closeness of network systems which before were open and the consequent failure of techno-utopian ideals. However, there was little evidence of this in the artworks on display, nor in the site-specific installations presented. I don’t support the idea that artists should be literally political, or activists, but when I experienced jon.satrom’s performance at the opening, it came across as a sort of exercise in showing what can be done through bending technology to generate new languages and approaches to that which is established. In a way it reminded me again that we often operate within boxes, and rarely attempt to challenge the form and format of what is given to us. But then, most of us already know this. And although in/compatible as a festival did not want to give answers but generate a context for formulating questions, as Gainsing specified in his presentation, I felt the need of a next step, a step made of actions, which to me was only fully present in the reSource programme of Tatiana Bazzichelli. When I rethink of jon.sotrom’s performance, and I am very aware I am using him as an example to point to a larger scenario (my apologies to the artist!), I cannot refrain from thinking that the system he was challenging was that of an Apple Macintosh software, built on visual tricks like Spaces, Mission Control, etc; a system that perhaps needs to be challenged at a deeper level since, for instance, its reliance on the exploitation of developing countries workers?

This is just a final thought.

That said, I am really looking forward to seeing how transmediale will move forward, will it take the next step from this initial change?. It will be interesting to see how this merging of historical perspectives, academic research and artistic innovation will stir up more conversations and, as I said, more actions for another exploration of the relationship between contemporary cultural production, media and technology.

Please note: since the richness of the programme, I have highlighted my personal experience of the festival, so that this review highly reflects the choices I made about what to attend and what I (unfortunately) left out from my jammed daily schedule.

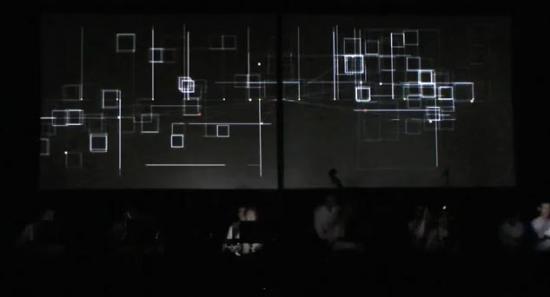

The video works of A Bill Miller seem to be at once futuristic and something recalled from our childhood (those of us who grew up with computers in some form or other) in what might be considered as a hauntological affectation that seems like a memory of the future from our childhood, with lines and simplicity of many early computer programs, forming complex ghosts of our pasts across the screen. These are a reminder that what computer graphics can do, doesn’t have to be composed of 3D, with million of vectors and a painful, failing attempt at verisimilitude. Just as theatre, with it’s artificial simplified set designs and symbolism. It can sometimes be more real, offering a greater empathy than a well designed and directed film. Often, there can be greater beauty and compulsion when engaged in simple works than those of greater complexity.

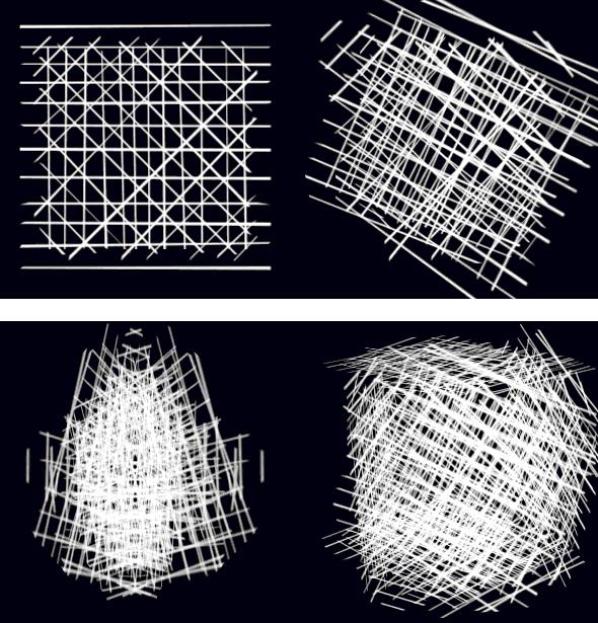

“We exist within a built environment that is constantly mediated by the grid. Grids organize space through coordinate mapping and patterns of development. Grids compress, redisplay, and reorder information. Grids are an enforcement system imposed upon both nature and culture. I respond to this ubiquity by creating gridworks. These forms examine the blurred boundary between the machine and the human – the tool of data collection and the interpretive mind.”

Like a lot of people, my first encounter with the work of A Bill Miller was on the small screen. Despite the numerous festivals and exhibitions that his works have appeared in1, this may be the only chance viewers have to enjoy them. Which is a shame because they really work well when expanded on to a larger screen. Even if you only get to view them on a larger television screen, it’s worth doing. Even some of the work that is small in scale and scope, benefits from being shown on as large a screen as possible. It takes a broader and more encompassing screen to really engage the viewer completely into the work. For some of the black and white work, the overlaying of ASCII letters (reduced to just shapes when not ‘read’ as alphanumeric characters) shows how some works can explore the technical palette of the production software as possible. Which isn’t to say that some of the works aren’t also complex and (literally) multilayered.

There is a psychic landscape explored in Miller’s works. A landscape that feels as though it sits just behind the everyday, observable world we inhabit. Not in a David Lynch, behind the picket fence, kind of way, but inside the mind’s eye, at a point where the brain hasn’t yet coalesced the datastreams of visual stimulation into a recognisable image. It’s that in-between space that seems to at the heart of some of the Gridworks: the spaces between being held in check by the grids. And clean white spaces are beautiful in themselves, but they also divide the elegance of those lines so that the work is about those spaces and the tension of being held in check: stopping them from bleeding into one another. The psychic landscape they map out is the same one that we have to face everyday as we negotiate our way through the ongoing datastream of western life. Work, rest, work, rest, shop, consume. Those days that you feel as though you’ve experienced and understood everything and life begins to blur into one continuous event: all it takes is to step back and really focus on individual moments to remind ourselves that life is actually full of thousands of unique and wonderful moments.

Works like Gridfont 7 suggest that the elegance of a few lines carefully placed can lead to great complexity through simple juxtaposition and rotation of basic forms. Just like so many other things in life, greater complexity begins to emerge from a gradual build up of even the simplest of those elements. Some of the work begins as a few short, hand-drawn lines before they re-adjust themselves and become a hive of geometric shapes: a honeycomb forming from the arrangement and connection of lines. Some works have the colour-bleed of early video work where over-saturated colours refuse to hold their place in the ordered spaces and begin to wander slightly.

gridworks_textanimation2010 is made from pure ASCII text characters, and “transmits an unreadable message that is aesthetic and abstract.” It’s stark black & white play of the non-text elements of written communication gives the impression of loss and emptiness, like lines of communication broken down through digital channels. This could be extracted from a relationship being held together via email or it could be text messages sent between two unreliable narrators each hoping to convince the other of some shared moment. A line of Xs brings to mind censorship but the blank underlines suggest space for the other party to fill in the blanks that we don’t always admit to when trying to maintain the peace in a relationship. Things are constantly being said, but nobody is ever saying anything to each other. Those are the worst accusations of Internet communications but they’re just as guilty of being performed in every other channel. They just become more visual on the Internet and even more so in works like this.

In case these descriptions suggests that the works are dry and overloaded with metaphor and meaning, they can be enjoyed on their purely aesthetic merits. Gridworks2000-anim09 is a work that can only be described as beautiful in its elegance and deceptive simplicity.

Although these works are positioned within media art, they (like many moving image art work) could be considered as cinema (and let’s face it, cinema could do with a fresh burst from a ruptured blood vessel right now). These are part of a cinema of special effects where the use of computer graphics enhances the moving image and steps away from verisimilitude. As mentioned previously, this lack of verisimilitude is part of the reality of these works. An added element of what makes them hauntological ghosts within the screen.

It’s imprinted into the very nature of cinema that it is a ghostly illusion or special effect, either computer generated or produced in the camera that belongs to every moment of cinema’s history. In fact it is even an illusion to believe that we are viewing an actual moving image when we watch a film or video. Either way, cinema is created on-the-fly by our own eye. The trick of creating moving images is to know how the brain responds to them and leverage that response to your own desires. The cross slicing of lines in Miller’s Gridworks feels so much like early computer graphics that at times it’s hard to step beyond thinking about technology’s desire for the new and the increasing momentum of the special effect algorithm and find the beauty in their simplicity. It’s in there and doesn’t take much effort to uncover. Like a good oyster in a restaurant, the reward can be unusual and pleasurable, but you have to get in and expend some energy to extract it.

FILE RIO 2012, Electronic Language International Festival, Art Galery of Oi Futuro, Rio de Janeiro, BR, Mar 12-Apr 8th

Scan2Go, New Media Caucus year long online exhibition, Released at CAA 2012

<terminal> monitors, Austin Peay State University, Clarksville, TN, 2/20-3/2

A/Vworkssssss, One Night Event/Performance, Borg Ward Collective, MIlwaukee, WI Jan 3

Streaming Festival 6th Edition, Het Nutshuis, The Hague, Netherlands, Dec. 1-18 2011

FestivalMulti2011_Especial – Curator David Quiles Guillo, Video Art Program, Rio de Janiero, BR, Nov-Dec 2011

Sheroes, One-Night Interactive Installations (Monthly), Toronto, CA, Nov. 18 and Dec. 23

GLI.TC/H Chicago – Live Video Performance, Chicago, IL Nov. 3-7

GLI.TC/H Program at FLIP Animation Festival, Birmingham, UK, Oct. 29

Punto Y Raya Festival, Museo Reina Sofia Madrid, November 3-6, 2011

BYOB Sao Paulo, Rojo Nova Sao Paulo, Oct. 29

Video On Paper Zine http://videoonpaper.tumblr.com/

3ra Convocatoria Belica, Valencia, Venezuala, September 2011 http://mvs.260mb.com/index2.html

I AM NOT A POET Festival, Edinburgh Aug.8-21 http://tkunst.wordpress.com/

Darko Aleksovski interviews OPA (Slobodanka Stevceska and Denis Saraginovski). OPA (Obsessive Possessive Aggression) is an artistic collaboration, based in Macedonia, whose focus is researching the social, cultural and everyday issues, as well as the ways of looking, thinking and behaving of a certain community in the shifting social and political conditions.

Their project entitled “Bollocks” is a complex and yet very simple interactive installation, made out of a video/image projection in a room in which only one viewer at a time is allowed to see it. The project was first shown at the Authorial Through The Appearance 3 exhibition in Veles, Macedonia (2009). Then it was modified in a second version entitled as “Bollocks for Everybody” for the Small Gallery in Skopje, Macedonia. After that the project was shown at the fifth edition of the AKTO- Festival for Contemporary Arts (2010) where it was awarded with the annual Dragisa Nanevski Award for interdisciplinary achievments. The project was also shown in Studio Golo Brdo, Rovinjsko Selo, Croatia (2011).

Darko Aleksovski: “Bollocks” is a project which was shown on several occasions in art festivals and group exhibitions. Once it was exhibited as “Bollocks for Everybody!”. Can you tell us what was first: its idea, or its title?

OPA: Our initial idea was to relate one specific phenomenon of the Macedonian cultural life: much stronger “gravitation” than in the other parts of the world. It means everything is much harder here, for every single “motion” connected to arts and culture, you need several times more energy compared to other places. It could be because of our institutions, or the specific mentality, or the geographical, political and economic situation of the country – it is a matter of larger analyses. However we didn’t have intention to speak about those reasons into this work, but simply to remind of the existence of the issue. That’s why the work (visually) is about seating and waiting. In the video-image we sit and endlessly wait for something to happen. And when the spectator enters, (s)he triggers the sensor and we both leave the image. So the spectator gets nothing and sees an image of two empty chairs. In the Macedonian colloquial speech you would say the spectator gets “tashak” or “tashaci” (Macedonian: ташак, ташаци). So that is the original title of the work – “Tashaci”, given when the work was completely shaped. “Bollocks” is the best English translation that we could find, but it still doesn’t represent the expression best.

And “Bollocks for Everybody” is the title of the second version of the work, created for the windows of Mala Galerija (The Small Gallery) located in a shopping mall in Skopje.

For our solo presentation in Mala Galerija, we made two different settings of the same work: (1) On the windows of the gallery there was a projected video-image of two empty chairs. When the casual passers by trigger the sensor, our figures were entering the video-image facing the spectator. (2) But inside the gallery we installed the original version of the work, which was intended for the regular visitors of the cultural events, this time invited for the official finissage of the exhibition.

DA: Is the project primarily concerned with the general Macedonian cultural context, or it is dealing with more universal issues?

OPA: We could say that this work is emanated from these local issues, thus it is concerned with the Macedonian cultural context. Translated into the general context it speaks more about the art system, the expectations of the audience, the immateriality of the artwork, about the things that we always miss out, the absurdity, the nothingness…

DA: On one occasion, you say that the inspirational thought about the project is: ‘Art is always in another place’. Does the project speak of ignorant art or ignorant audience?

OPA: It is more about the expectations. About the expectations of where the “real” art should be, what should it look like, what is the art like in other places (always better than our), while we miss the things that are happening (or could happen) here, in front of us. One other interesting interpretation of this thought is that the art is happening during the process of creation. The artist touches it for a moment, and everything that we see as an exhibited object is only a document, a trace of the existence of the art, a way for the artist to share with the rest of the world what (s)he had experienced.

DA: Do you think interactive art is one of the easiest ways to communicate with the audience today?

OPA: It is one of the ways, but it doesn’t have to be the only or the easiest way. Anyway the art today should be in the things that surround us, or incorporated into our everyday life. It should reach us other ways than just through the galleries. It should try to surprise us, confuse us, shake our solid image of the world and make us think and reconsider our attitudes.

DA: How do you feel about joking with/ in art? Do you think a joke in an artwork should be considered a serious statement?

OPA: Humor is one very helpful tool to address the social and the political issues, or the things that bother you and the things that hurt you. It doesn’t mean that if the work involves humor it doesn’t have a serious statement. Thus it is often present in our work. One other tool that we often use in our work is entertainment. Often it is the first thing that catches the audience, it “steals” their time and attention, and than through it we try to convey our message.

DA: Absence is something one finds in many of your works. The absence of connection with reality, absence of objects, even absence of a final artwork, or project. What kind of presence do you think this absence refers to?

OPA: It is really exciting if you succeed, while acting with the art language, to make an artwork that would be communicated but not perceived as an artwork at first. In that case, the work has a direct communication with the audience, not burdened with the fact that art has “special place” in our society. It becomes a kind of subversion of the everyday life – you can experience art without knowing what’s in front of you, yet the situation you have experienced, is an artwork. What we do in our work is about creating “situations”, or often creating the artwork together with our audience. Whether this artwork is either immaterial or difficult to possess.

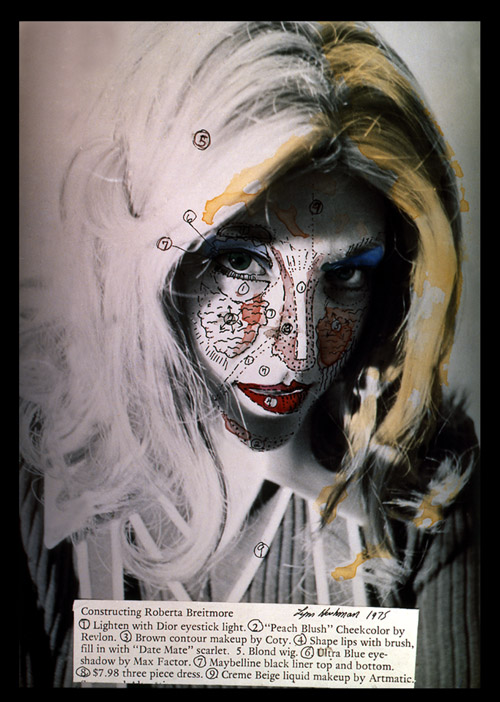

Featured image: Lynn Hershman Leeson Portrait (Photo Credit: Ethan Kaplan)

Woman, Art & Technology is a new series of interviews on Furtherfield. Over the next year Rachel Beth Egenhoefer will interview artists, designers, theorists, curators, and others; to explore different perspectives on the current voice of woman working in art and technology. I am honored to begin this series with an interview with Lynn Hershman Leeson, a true pioneer in the field who has recently produced !Women Art Revolution- A Secret History.

Over the last three decades, artist and filmmaker Lynn Hershman Leeson has been internationally acclaimed for her pioneering use of new technologies and her investigations of issues that are now recognized as key to the working of our society: identity in a time of consumerism, privacy in a era of surveillance, interfacing of humans and machines, and the relationship between real and virtual worlds. She has been honored by numerous prestigious awards including the 2010-2011 d.velop digital art and 2009 SIGGRAPH Lifetime Achievement Awards. Hershman also recently received the 2009 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, an award which supported her latest documentary film !Women Art Revolution – A Secret History.

Rachel Beth Egenhoefer: Your most recent project is the film “!Women Art Revolution” which you have been collecting materials for and working on for the past forty years. Why is now the time to present it as a finished work?

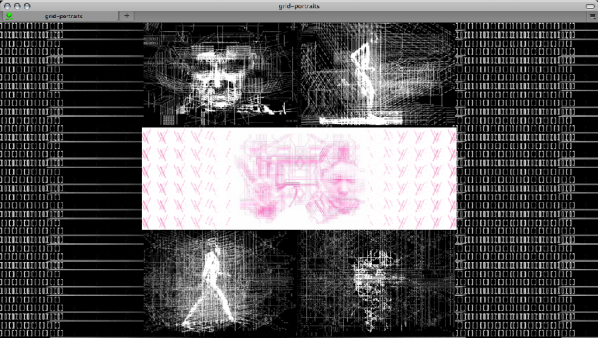

Lynn Hershman Leeson: TECHNOLOGY! The film is one narrative, but I’ve put the entire 12,428 minutes online through Stanford University Library, making all the narratives and aterials accessible, so in effect there are no out takes. Also the RAWWAR org archive/website allows people to continue the story online. So the story continues to grow beyond the single narrative, which technology allows us to do now.

Additionally, I wanted to push out into public view the graphic novel, curriculum guide, and the story to affect the legacy while women who created the movement could be appreciated.

RBE: Can you expand on how you see the RAWWAR story continuing online? Or maybe what is the goal of the archive/website? Do you envision people adding to it?

LHL: Yes, it was made specifically so that people, especially younger generations will be able to add information. At the Walker Art Center, they have scanning stations and are training people how to upload work onto the site. My hope is that people from around the world will add materials and it will be a living repository of this type of growing and accessible information.

RBE: The film has been touring in the U.S., what has the response been?

LHL: Incredible. It has been in over 60 cities, and standing ovations in San Francisco, Houston, Toronto, Sundance, Berlin and Mexico City. People seem deeply affected by this secret history and seem to appreciate knowing about it.

RBE: Has the response varied either with geography or current events?

LHL: Not really, it seems vibrantly appreciated worldwide despite it being about women in America.

RBE: Can you explain the grammar behind the title “!Women Art Revolution”?

LHL: If you mean why the ! first, it was so we would be listed first, rather than under W. It didn’t work, but that was why we did it originally. It also is a wild exclamation at the start, which is what the movement was.

RBE: The film is described as presenting the relationships between the Feminist Art Movement and the anti-war and civil rights movements, showing how historical events sparked feminist actions. Do you see any connections to be made with the current Occupy Movements?

LHL: Yes, absolutely. In some ways because it is about how the disempowered and invisible people were able to gain their place in culture; how people who had their voices silenced were able to amplify their message and subverted social systems, with work that expressed censorship, freedom of expression, social justice and civil rights and directly made political change. It is an inspiring story of reinvention.

The goals were clearer than with Occupy. But the disenfranchised edges of culture is similar.

RBE: A lot of your early works dealt with issues of identity. How do you think the notion of identity has changed over the years?

LHL: It has become more technological, more global, more cyborgian. We now, because of the internet are linked globally and that has resulted in a “hive mind” and in turn, that seems to be a cohesion and holding together the individual fracturing that had occurred over the last two decades

RBE: Can you expand on the idea of the “hive mind that seems to be holding together the individual fracturing”? What makes up the hive, what is fracturing us? Is this good or bad or neither?

LHL: The hive is social media and people who participate in the Internet grammar. There is a congealing through access to information. As individuals, I think we have been fracturing, rupturing, split for decades and have become multi faceted and multi taskers. But there’s a price in the lack of personal cohesion that results. I think that having a common reference or ‘hive’ is a very good thing, as it tests our idea of ‘reality’, and serves as a hub of communication.

RBE: Do we make our own hives? Or are those defined for us (either by others/ FaceBook/surveillance/ etc)?

LHL: We are all part of global re-patterning that is happening live on a global scale and it is naive to assume we can act independently or not be connected or affected. We are constantly challenged, influenced by peripheral and pervasive information and in turn we have become fodder for surveillance and digital integration.

RBE: Some contemporary artists and thinkers have been critical of our online selves and physical selves. Sherry Turkel for instance has described people as “performing themselves” online by constantly updating Facebook profiles, tweets, etc to show an ideal version of ourselves. Can you draw any distinctions between virtual, physical, and performative selves?

LHL: I think we perform ourselves every day, not only on social media, but in all interactions. I do not think all images or versions of ourselves are ideal. There is absolutely a difference between real/physical and virtual selves. They each have a context, reference and function. As far as being performative, that depends upon the distinction used for how it is used. One can, in fact, consider life itself and everything one does as performance.

RBE: This interview is going to be part of a series of interviews with women working in Art & Technology. What do you consider to be important today about being a woman working in art & technology?

LHL: Ada Lovelace wrote the first computer language, Mary Shelley envisioned artificial intelligence, Hedy Lamar invented spread spectrum technology, which led to cell phones. Women have been enormously prescient in visioning and affecting the future of the world through technological linkage systems.

RBE: Do you think it is still useful to discuss the female voice as a separate voice in the field?

LHL: I think the female voice is critical in all aspects of the future and should not be limited to a category.

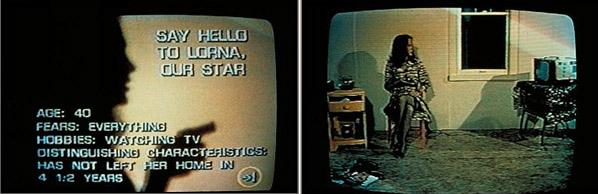

RBE: One of your earlier works, LORNA, depicts a woman who never leaves her apartment and becomes more and more fearful as she watches ads and news on the TV. Some might say television media has gotten far worse since the 80s in both fear mongering and controlling conversations. What do you think about the current state of the media?

LHL: Right, the idea of media as totally affecting our outlook has shifted. Media is no longer omniscient! The 99% are activating their voices and warbling into existence. There are other problems with social media… deeper ones that splay into the cracks of fractured identities and insist on more disruption and lack of focus. But perhaps that is what is affecting our constantly changing evolution.

RBE: If LORNA were around today what would she be thinking or doing in her little 1 room apartment?

LHL: Blogging and all forms of social media including excessive and obsessive shopping, no doubt. She would probably not really be agorophobic either. She would, however, probably be paranoid. She would use a webcam and notice all the ones surrounding her no matter where she moved.

RBE: Do you have hope for change in the future?

LHL: Hope? It is inevitable. I believe in the next generation! They always, in their amnesiac optimism re invent the future in ways that can’t be predicted.

RBE: You have been involved in academia for some time, what do you think is important to be teaching in the Universities right now?

LHL: Independent thinking and creativity, the maintenance of ethics and a profound sense of humor!

RBE: Do you have any new projects you are working on?

LHL: Yes, at least 3 .A new film which is part 3 of my trilogy about the evolution of the human specis, a new installation that uses scanned beating heart cells, and a long term project about Tina Modotti.

Find our more on Lynn Hershman Leeson and Woman Art Revolution here: http://www.lynnhershman.com/http://womenartrevolution.com/

Taina Bucher interviews curator Gaia Tedone about her latest online curatorial project called ‘Is Seeing Believing?’ as part of the TRUTH programme at or-bits.com, an online platform for the display of contemporary arts and production of new works. Born in Italy, in 1982 Gaia Tedone holds an MFA in Curating from Goldsmiths, and has for the past year been one of the curatorial fellows at the Whitney Independent Study Program, New York. She has been involved in a number of art projects and worked with institutions such as Whitechapel Gallery, James Taylor Gallery, The David Roberts Art Foundation and Tate Modern.

Taina Bucher: Tell me a bit about your background for doing curatorial work. How did it get started and what are some of the thematic interests that have been important to your work?

Gaia Tedone: I started doing curatorial projects in London, where I was living and working for the past five years. The time spent at Goldsmiths was extremely formative from a practical and intellectual point of view. I was involved in a number of projects – some of them in collaboration with institutions in London, such as the series of talks Curating Fictions organised at Whitechapel Gallery, others were developed within the academic context, as for instance IM magazine and the publication A Fine Red Line (A Curatorial Miscellany) which I edited with fellow curators Isobel Harbison, Ilaria Gianni, Nazli Gürlek, Rosa Lleo and Yannis Arvanitis. The latter experience led us to establish the curatorial collective IM projects – a platform for editorial projects for which I contributed for the following two years.

The MFA in Curating at Goldsmiths and the Whitney Independent Study Program have both helped me to locate my interest in the history of art production within today’s global context and to look at the ways in which specific economic and political contexts shape the production and circulation of art. These two complementary programmes of study informed my research interests, which are located at the intersection between the fields of new media and cultural studies.

This year, within the context of the Whitney Program, I was exposed to a number of seminal authors and texts that since the 70s have contributed to the development of the field of cultural studies, and I was deeply inspired by the recent work of David Harvey and the political philosopher Chantal Mouffe. This intense year of research has informed the conception and realization of the exhibition Foreclosed. Between Crisis and Possibility that I co-curated with ISP fellows Jennifer Burris, Sofía Olascoaga, and Sadia Shirazi at The Kitchen in New York.

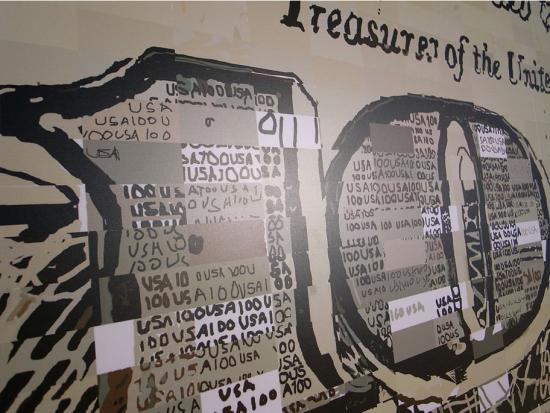

The exhibition, which included works by Kamal Aljafari, Yto Barrada, Tania Bruguera, Claude Closky, Harun Farocki, Allan Sekula and David Shrigley, took the current housing crisis in the U.S. as the departing point to explore other meanings of the word foreclosure, which also evokes processes of exclusion and a shutting down of recognition.

Taina Bucher: How did you get into doing online curatorial work?

Gaia Tedone: I was invited few months ago by Marialaura Ghidini to collaborate with her and Christine Takengny on the autumn issue of or-bits.com. Marialaura had some preliminary thoughts on how she wanted to develop the programme, and after few Skype meetings we established a common ground upon which we built three parallels projects. The programme curated by Marialaura was launched in early October with works by Angus Braithwaite/David Raymond Conroy/Adelita Husni-Bey/Iocose/ M+M (Marc Weis and Martin De Mattia)/Richard Sides and my response followed shortly after that. Is Seeing Believing? is my first curatorial work online.

Taina Bucher: How do you feel about exhibiting art online, what are the challenges and benefits? In what ways does the conceptual work with developing a project online differ from curating exhibitions in a more offline institutionalized setting?

Gaia Tedone: or-bits.com provided me with technical support in terms of coding and web-design, while I was left totally free to develop my own curatorial strategy. My original idea was to build up a True or False web-based questionnaire, mainly text-based. However, the project developed in a slightly different direction and I was happy to adapt its format to the eclectic contributions I was receiving. Once I gathered all the content, I chose to mimic the format of an online newspaper, as this seemed the best visual strategy to actually play with the ideas being put forth while maintaining an inner coherence for each artist’s contribution.

I found the context of the web extremely challenging from a curatorial perspective, as it required the ability to work simultaneously on different elements, from the editing of content to the formalization of a coherent visual output, employing an approach both flexible and rigorous. It felt like a condensed version of a ‘traditional’ show, yet faster in pace and with a different degree of curatorial control. It came together fairly organically. The Web I think poses a number of important questions, especially in relation to the short attention span we generally dedicate to what we read or look at when surfing the net. Would the type of art being produced have to play or interject whit this? How would it change the public’s experience or engagement? These are all open questions for me.

Taina Bucher: What is the idea behind your current exhibition on or-bits?

Gaia Tedone: The theme TRUTH developed out of several conversations inspired from Žižek’s text Good Manners in the age of Wikileaks and a shared interest in somehow questioning the democratic claim of the web as a space of freedom, in light of the recent developments of Wikileaks and of the role that social media played during the Arab Spring. In a world in which everyone can be the author of his/her own news, how do we assess what is true or false? And how is this shifting power’s relationships and individual agency?

Within this larger framework, the project Is Seeing Believing? specifically focuses on the relationship between image and belief and develops from the engagement with two particular images: first, the image of Caravaggio’s iconic painting The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1601-1603), depicting Apostle Saint Thomas’ unwillingness to believe without direct, physical and personal evidence in Jesus Christ’s Resurrection. Second, the image published in the news showing President Obama, Hilary Clinton, Joe Biden, along with members of the national security team, watching Bin Laden’s death live.

The latter image, which quickly became one of the most publicly viewed in occasion of Bin Laden’s death, claims to present a less crude version of the story, but in fact it does not. On the contrary, it carries the absence of the image we are actually looking for – the one of Osama Bin Laden’s death body – affecting the viewer on multiple levels. On the one hand, by making the relationship between political power and media control even more visible; on the other, by acknowledging the necessity to see an image in order to believe in a fact. Then again, to what extent does it really matter if what we are looking at is the actual event or other people witnessing it? Has seeing become believing? These are some of the questions and preoccupations that have animated the conception and realization of this online project.

Taina Bucher: ‘Is Seeing Believing?’ is an exhibition displayed in the format of a newspaper. Who are the contributing artists?