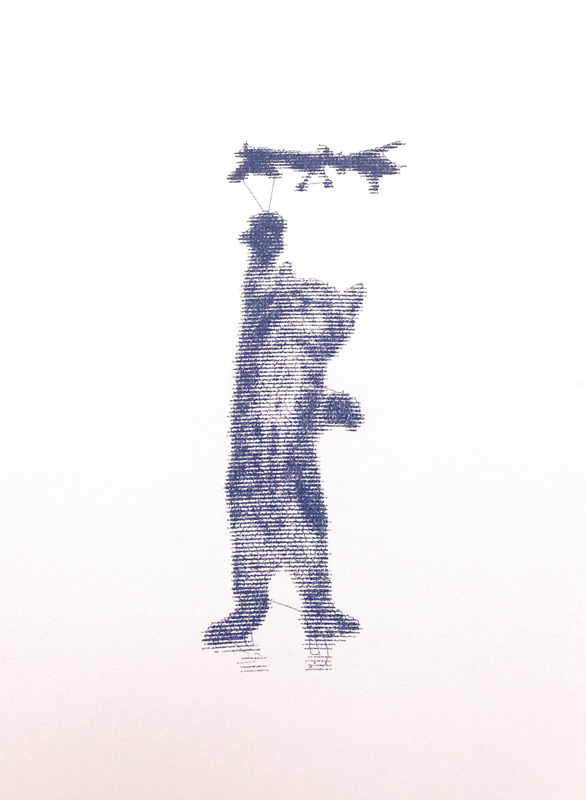

Featured image: “Binoculars” at CHB in Berlin (2013)

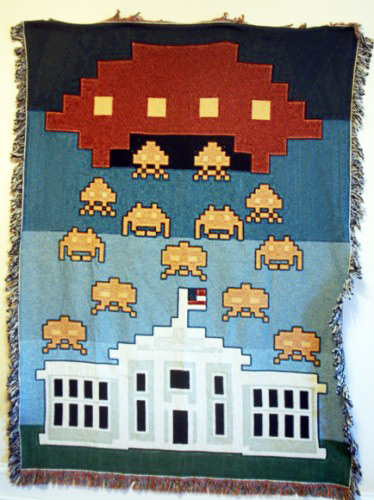

Varvara Guljajeva & Mar Canet have been working together as an artist duo since 2009. They have exhibited their art pieces in a number of international shows and festivals. As an artist duo they locate thermselves in the fields of art and technology, and are interested in new forms of art and innovation, which includes the application of knitting digital fabrication. They use and challenge technology in order to explore novel concepts in art and design. Hence, research is an integral part of their creative practice. In addition to kinetic and interactive installations, the artists have also experience with working in public spaces and with urban media.

Varvara is originally from Estonia, and gained her bachelor degree in IT from Estonian IT College, and a masters degree in digital media from ISNM in Germany and currently is a PhD candidate at the Estonian Art Academy in the department of Art and Design. Mar (born in Barcelona) has two degrees: in art and design from ESDI in Barcelona and in computer game development from University Central Lancashire in UK. He is also a co-founder of Derivart and Lummo.

Filippo Lorenzin: Open culture is one of the main points of your research and activity. Could you describe how this influences your art practice?

Varvara & Mar: We are living in very exciting times. Open source has introduced democratization of production and creation. Now you can build your own 3D printer, laser cutter, knitting machine, make a light dimmer circuit or develop a body tracking system. Some years ago we couldn’t even imagine this and now we have access to this knowledge. People share their creations and these process, which is incredibly inspiring for us and many more people. Thus, knowledge is built on top of knowledge. We make use of open source marterial in our work and we try also to contribute back. This is the whole point of open source in our mind. And if one looks in the perspective of art to open source projects, then really many open source projects have artists on board, for example, OpenFrameworks, Processing, and more.

Open source also has an educational aspec. We do many workshops with people and teach what we know and how we work. We think open source culture is largely based on the spirit being open to sharing knowledge with many others.

FL: I’m really fascinated by your interest in textile fabrication. it reminds me the early industrial developments that were deeply connected to in the textiles industry. How and why would knitting be integrated these days as part of a makers’ culture?

V&M: The process of integration is well under way. There has been a good number of makerspaces who have dedicated areas for textile production, like WeMake in Milan and STPLN in Malmö. And believe it or not this simple thing helps to introduce gender balance in these kind of places. We’re not just talking about innovation, which can boost gender equality when you introduce knitting to hacking. We’re also talking about the democratisation of production, when thinking about clothing too. This area is quite vital and commonly understood. 3D printing toys is a cool activity for a weekend, but then it becomes boring. Knitting a sweater or a scarf has real value and the quality is always higher than a typical mass produced factory product.

For 3D printing we cannot say the same. Don’t get us wrong, we are not against the 3D printing. We love it and have six printers in our studio. Our point is that the areas of concern for digital fabrication are not complete, and the founders of FabLab have overlooked the whole area of textiles.

FL: You’ve run many workshops taking in account various topics such as 3D printing, solar energy and knitting, of course. How do these activities connect with your research?

V&M: First of all, we like to teach and interact with our students. Second, preparing a workshop, allows us to research more about the field, and organise and share our accumulated knowledge and experience.

And finally, workshops are one part of our income. We don’t have any other jobs on the side, and exhibitions and commissions are not regular and do not always pay well, and yet the bills keep coming in. Hence, workshops help us to pay our bills.

FL: One of your works which most fascinate me is “Sonima” (2010). It’s a project that takes in account questions that have become quite recurrent in last months, mostly linked to Anthropocene discussions. The soft coexistence of technology and nature which is organic and artifical. Which is one of the main topics of your research: why are you so interested in this question? It looks like you’re trying to develop experiments for an utopistic future in which humans and nature live in symbiosis. Am I wrong?

V&M: Yes, many of our works express our futuristic thoughts or imagination where the digital age will lead us and our planet to. It is nice that you have noticed this. I would say this kind of concept in 2010 was quite subconscious. I (Varvara) was very interested in organic form but with mutational origins but still adapted by nature.

More conscious approach towards anthropocene epoch can be seen and felt in “Tree of Hands” (2015), which is one of our recent works. However, it looks like we have touched quite a taboo topic. For instance, “Tree of Hands” was rejected by jury of PAD London fair because of its depressive concept.

FL: “Shopping in 1 Minute” (2011) is another project I would like to ask you about. This work is about consumerism at its finest (or worst), turning one of the most typical capitalistic places (supermarkets) into ludic spaces. It’s a piece of social art that presents itself without informing the public what is right and what is wrong, but it rather suggests in a more subtle way the perversion at the base of that system. What do you think?

V&M: Yes. What we are doing is the absurd exaggeration of the same action (buying) to a maximum with one but: not buying and playing instead. There is a saying that shopping is 5 min happiness. The artwork tries to create a synthetic feeling of satisfaction of the ability to buy. The shopping centers are doing everything to stimulate our consumption needs, and our artwork manages to get inside their ecosystem and playfully releases that artificial desire to buy.

FL: With at least a couple of projects, you’ve also worked to the redefine hurban landscapes by looking at the invisble while at the same time taking on rather specific forces such as mass use of Wi-Fi networks becoming part of the everyday. I can’t help thinking that this is somehow related to privacy questions, probably because one of the most notorious scandals some years ago was Google’s secret recording of Wi-Fi networks with their Street View cars. Am I wrong?

V&M: Not really. But definitely Google has played a role in feeing our concerns about being watched, spied, hacked, scanned, etc. For example, the last scan for WiFi router names we did last summer in Tallinn some people were quite freaked out seeing a person on a bike with a camera on its head and tablet in front. I was even once asked if I worked for Google. 🙂 Anyways, the project was great fun for us, and we got to explore the city and discover the whole invisible communications networks and the self expressive layers of it all. After the Tallinn scan we even changed our minds about the 32-character local Twitter that the WiFi router SSID could be used for. The Tallinn experience showed us the new tendency: where people would use radio waves for semi-anonymous graffiti, communicating sometimes silly, protective, racist or political messages.

Talking about inspiration for this project, we got our interest for WiFi names from one article talking about the ability to track down pro- and contra-Obama communities by just looking at WiFi names in the neighborhood. This was before the US president election. Then we started to thinking of an art project on this topic.

FL: “The Rythm of City” (2011) is another project which is also ‘subtly’ related to control issues. The idea that someone can depict the state of a city by looking at data deducted from social media and web platforms. This type of thing is real now isn’t it – what do you think?

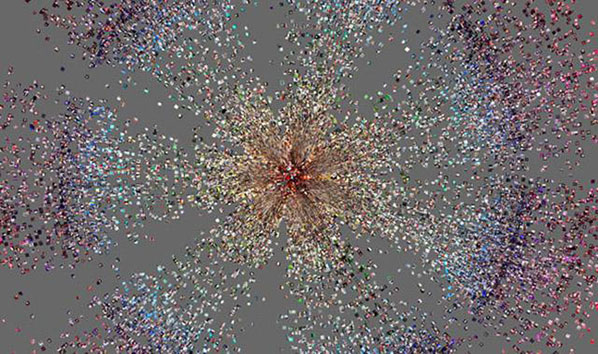

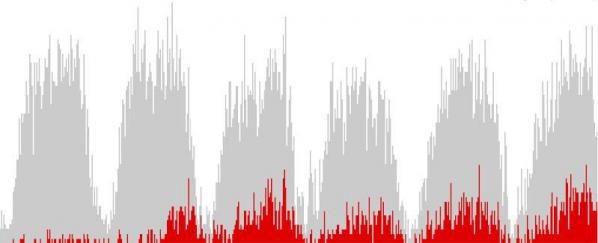

V&M: Definitely it is. However, the work’s main intention is not to talk about control issues rather about big data and its applications. Perhaps the main intention of this work is to offer to the viewer(s) a birds eye view on different cities in real time. In other words, The Rhythm of City allows you to zoom out and witness the larger picture on the current situation. And this larger picture is formed by everybody’s activity on social media, which is tracked down every minute. We call this action ‘unaware participation’ by digital inhabitants. The urban studies of Bornstein & Bornstein from early 1970s served as an inspiration for this artwork. They had discovered a positive correlation between the walking speed of pedestrians and the size of a city. Simply put: the bigger a city, the faster people move. The artwork demonstrates our interpretation of a city’s tempo through in its digital form or life. Hence, The artwork talks about pace of life in different cities at the same moment when the piece is viewed.

FL: What have you been working on these last few months and what plans do you have for 2016?

V&M: We are working on a series of new works talking about money. When we have completed “Wishing Wall” in London in 2014, since then we have noticed that the majority of people, especially a younger audience, wish for money. This really caught our attention. The ongoing hard economical situation in Europe pushes forward the need for money and also introduces a growing gap between the economical classes. So we’re investigating people’s desire for money and its connection with happiness. Making use of interactive technology we are aiming to approach playfully and magically the desire for becoming rich. At the same time, we cannot let go of knitting. At present, we are working on an open source flat knitting machine, which will be able to knit patterns also. Besides the new productions, we are showing our existing works in various exhibitions. For the confirmed ones, “The Rhythm of City” will be part of “REAL-TIME” a group show curated by Pau Waelder in Santa Monica museum in Barcelona from the 28th January. In February “Digital Revolution” (the touring exhibition by Barbican), which “Wishing Wall” is part of, moves from Onassis Cultural Center in Athens to Zorlu Center in Istanbul. And hopefully we get couple of other shows and new productions that are in the air at the moment and still to be confirmed soon.

Featured image: @mothgenerator by Everest Pipkin and Loren Schmidt

Taina Bucher interviews artist and bot maker Everest Pipkin about their most popular Twitter bots, how they work and what they mean. Indeed, what are bots, who else is engaged in artistic bot-making, and how will social media bots evolve?

Meet Tiny Star Fields. Several times a day, the Twitter account publishes a field of stars in different shapes to a dedicated 51.000 followers. The latest tweet, published 53 minutes ago, has already been retweeted 151 times and gathered 114 favourites. Tiny Star Fields is a Twitter bot. During the last few years, bots, or automated pieces of software, have become an integral part of the Twitter platform. As some recent reports suggest, bots now generate as much as twenty-four per cent of posts on Twitter, yet we still know very little about who these bots are, what they do, or how we should attend to these bots. Admittedly, star-tweeting bots like Tiny do not belong to the kinds of bots that are most talked about. When people usually think of bots, they mostly have a specific type of bot in mind, which animates feelings of annoyance and disturbance. The spam bot, however, is but one kind of bot.

As Tiny and many others like to attest, bots are just like people. They are different. They tweet for different reasons, have specific audiences and engage with the world in various ways. Guided by their human programmers or taught to learn from existing data in playful ways, bots are legitimate users of platforms. But bots would be nothing without their creators, their makers who have conceptualized and brought these digital personas ‘to life’. So let’s not just meet Tiny Star Fields but also Everest Pipkin, the 24-year-old artist and creator of Tiny Star Fields.

Everest why don’t you tell us briefly about yourself and your background?

I grew up in the woods of Austin, Texas, where I also attended university for my undergraduate degree in studio art. Most of my work there was focused on drawing and installation, but I was also curating internet ephemera and beginning some rudimentary code projects at the time (albeit in isolation from others doing similar work). I also have a history in curation and have run creative spaces for many years. I’m currently pursuing my MFA at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh.

What got you started with making Twitter bots?

I started making bots in the summer of 2014. I moved to a tiny town in rural Minnesota (population 900) for a longer-term artist residency and was quite isolated. I didn’t have a car, there was no bus or train, and I didn’t know anyone there. I was used to being alone on residency, but often I had friends near enough to visit or a local coffee shop to haunt. With no other options, I was at home and online almost constantly. The internet has always been important to my practice (and my social life), but I attached myself to it as a lifeline in that period.

I was already following Twitter bots (@everycolorbot, @youarecarrying, @twoheadlines, @minecraftsigns, @oliviataters, @prince_stolas, and I’m sure many others), but being online constantly shifted how I thought of them, rather than just seeing their occasional statements as charming non-sequiturs in a human space, I started to notice their underlying personalities, the structure of code that differentiated one from another; when they posted, the kind of source materials used, how they interacted with others. With nobody to keep up with locally, I also began sleeping in erratic structures- some nights for 5 hours, others for 14. As a side effect, I would catch off times on Twitter, where everyone but the bots were asleep. These timelines of automation had a striking effect. I was particularly fond of the bot chorus around the turn of the hour- bot ‘o clock, as some call it.

I had been following and aware of @negatendo’s #BOTALLY posts (a sort of # organizing structure for bot-related news and resources) for a while, but I also started following @thricedotted, @inky, @beaugunderson, @tullyhansen, @aparrish, @boodooperson and @tinysubversions (and many others!) in this period. There were new bots almost every day, all unique, and I was really taken by how people interacted with them and how they operated in that social space.

How did you go about making your first bot?

I got node.js set up on my laptop (no small task for me then) and figured out some fundamentals of text manipulation in javascript. After several false starts, I made my first bot, @feelings.js, in the afternoon. I made @tiny_star_field five days later, in the middle of the night, hiding in my basement during a tornado. The power was out, and I’m almost certain I got the structure done in one laptop charge. I deployed it when the power and internet came back the next day.

You waited for the sky to clear and become sprinkled with stars again. In the meantime, you made your own digital sky, that’s cool. Did you do a lot of programming before starting with making bots?

I suppose that depends on what you mean by programming. I had worked in and around browser-based experiences for years but had never taken a structural approach to learning code. Every new idea and project had a particular set of problems that I attacked with utter naivete, writing vast messes that were shocking when they worked. Looking at my source code for those projects now is very much like looking at an outsider-art approach to computer science. Which is, I suppose, what they are.

I still sometimes struggle with basic concepts just because I haven’t run into them before- I learn best when directed at a goal, and sometimes those goals skirt fundamental structures. My knowledge is a funny hodge-podge assemblage of extremely difficult concepts I needed for some project or another, while I may forget the syntax for a basic sentiment. I keep telling myself I’ll read a book or take a course on putting code together properly, but so far I keep learning what I need. I am sure I will feel the same about my current projects in a year or two as I do about my older ones. My first bots are very embarrassing inside and it has only been a year and change.

You’ve said that @tiny_star_field is your most popular bot, but your personal favourite is @feelings_js. Would you care to elaborate?

Neither of those bots came from a particularly well-considered place technically; they were the first I made, and I was learning. I was tickled by the idea of a bot that did nothing but emote; it seemed like a charming inversion of the coldness that often creeps into automata. Tiny was a simple reflection of my Unicode character habit; I have a hobby of making little vignettes or dioramas combining characters and atypical symbols, and I have been enjoying automating them. (I am also now a Unicode Consortium member and am working structurally with these characters.)

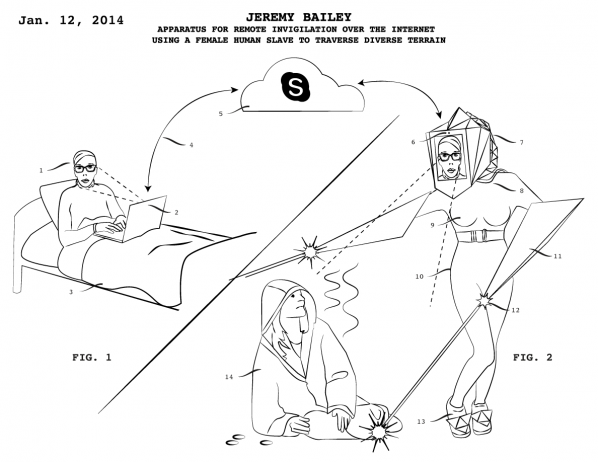

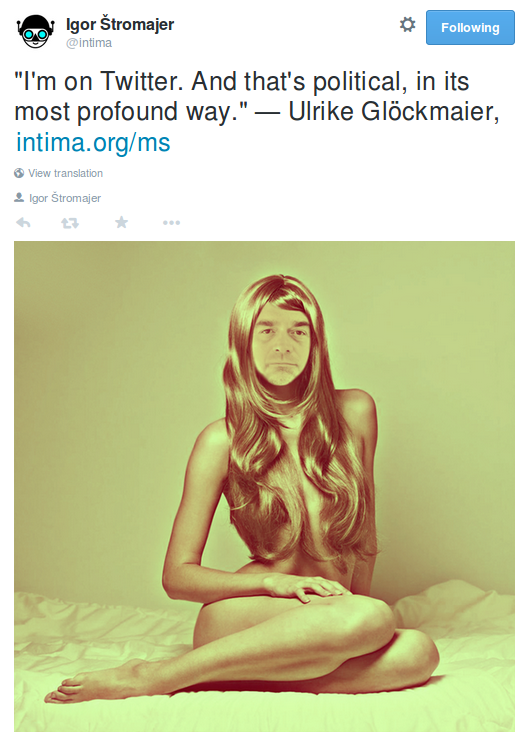

That comment about favourites was from a long while back, and my favourite bot is probably now Moth Generator (@mothgenerator), which was a collaboration with @lorenschmidt. It’s different from many of my bots; it’s just a wrapper on an image generator, but it is the first bot I’ve made that I felt used @-replies in a truly useful manner. It takes the text of the tweet sent to it to seed the generator with a unique number; therefore, the ‘moth’ moth will always look like every other ‘moth’ moth, while a ‘bot’ moth would shift in many ways. A ‘moth bot’ moth would share characteristics of both.

How do these bots work?

Feelings.js (and a few others like it) is basically a fill-in-the-blank Wordnik wrapper. It has a variety of possible sentence structures on a switch statement and then pulls parts of speech from the dictionary API. I have a few structural rules that slightly favour alliteration and a few other cute tendencies (blocking offensive words), but it is basically mad-libs.

Tiny is even simpler; it has a large array of star and space options and pulls randomly from the available options. The biggest challenge was finding an ideal balance between character frequencies. I tweak it occasionally and don’t feel it is ideal yet. I am tempted to make it sparser. I am also in the process of making a Tiny Star Fields clone that uses actual astronomical data at varying scales, so the tweets will be a literal patch of sky.

Some of my other bots are a little bit more complicated- Moth Generator is a wildly long drawing routine in Javascript, Sea Change (@100yearsrising), tweets unicode characters mapped to sea-level rise predictions over the next century. Others use more obscure text manipulation techniques and large corpuses. But I think it is important to note for folks just starting that complication does not necessarily make them stronger artistically or more popular socially- the best things are almost always just good ideas.

What has been the response to your bots?

There is certainly an audience of bot appreciators; sometimes, I will see people who follow 30 or 40 bots but none of their makers. Bots also have their own secret lives outside of intention. Tiny auto-followed people back for a while (something like the first 6k) made for a truly wonderful sample! Very few are in the bot community; I think the vast majority are One Direction fans. It is a fascinating slice of social life I would never think to seek out myself.

What is the bot community that you are referring to?

Gosh, what is the bot community, good question. I suppose it seems to be a loosely associated group of folks interested in social bots. People seem to come from all walks- programmers, game developers, linguists, writers, artists, analysts, and poets. Making the skeleton of a Twitter bot is a fairly simple exercise and doesn’t inherently have the high knowledge overhead of some other creative programming tasks. They are also incredibly flexible in content and process, and I think that mutability allows a certain wealth of intent from bot to bot. These two avenues of openness mean they are used for all sorts of things! As entities, they are as unique as the people who make them.

In general, I’ve found folks who are organized around making bots to be nothing but supportive, kind and interested in helping others get started with producing their own work in this realm. Within that community, structure are also all the folks that might not make bots (yet) but know what they are, and are interested in their processes, or write about them, or consider them valid as artworks or creative entities.

What, indeed, are bots?

What are bots? Gosh, this is an even better question than the one about bot communities. So, there are many ways to think about bots, and in my opinion, they are stackable and do not refute one another. But here are my thoughts:

Firstly, they aren’t new automata has been around for a very, very long time. One can look at examples of clockwork machines or candle-powered toys from over 1000 years ago. Even beyond physical examples of automata, the idea of bots is pervasive culturally; stories about golems and enchanted armour or physical objects imbued with personality have been with us since stories began.

Digital bots (especially those living in social spaces) fit into this long history of objects granted almost humanness. They fill in for a part of human action, the slice of person granted to digital representations of ourselves. Just like the golem that guards a passage, their tasks are programmed, but we grant them entity because they do these tasks on their own (guard, tweet). Perhaps this is as much doubt (“Is it /really/ a bot, though? Maybe it’s just a person pretending?”) as it is a gift.

Secondly, I do think there is an aspect of doubling or mirroring that these bots employ. They are widening the reach of their creators; they are automated versions of a specific slice of their creators. Many, many bots fall into this category. Something Darius Kazemi once said first got me thinking this way. It was advice to a want-to-be bot maker who didn’t have an idea for a bot. Darius suggested ‘come up with a funny but formulaic joke and automate it’. This type of repetitive production is not just seen in joke bots but almost all bots that are not attempting to emulate humanness. The maker would have made the joke once; by making a bot, it is made many times (but also, perhaps made better than it would have been once).

To expand, the goal of work-by-generation is a fundamentally similar but shifted process from that of work-by-hand; rather than identifying and chasing the qualities of a singular desired artwork, one instead defines ranges of interesting permutations, their interpersonal interactions and how one ruleset speaks to another. Here, the cartographer draws the cliffs that contain a sea of one hundred thousand artworks. And then, one searches for the most beautiful piece of coral inside of their waters.

So, I suppose this is where bots are truly interesting to me because this kind of making (looking for the best moment in a sea of automated possibilities) is a methodology of construction that feels, in some ways, new.

I like the notion of bots leading secret lives. Are you ever not in control over your bots? Or what does this secrecy entail?

I take a pretty lax approach to keeping up with my bots. I rarely log into their accounts or closely monitor what they are up to. I censor certain offensive words, follow them on my Twitter account, and hope to catch them if they break. This means that their notifications never reach me; the things that are said to them (or their own replies) are often invisible to everyone but them.

In what ways do people or other bots interact with your bots?

Most (although not all) of my bots are non-interactive, meaning they do not @reply back when spoken to. That being said, they are absolutely interacted with. Tiny star fields, in particular, get a ton of messages; lots of people will have conversations in the mentions. I find them pretty charming and will occasionally peek at what people are saying to one another. Since I generally keep @replies off, I don’t get the bot-to-bot eternity loops you’ll sometimes see with the image bots, ebooks bots, or others that reply. But I always like it when spam bots or Reddit bots find mine by keyword search. The best example of designed bot interaction might be Eli Brody’s tiny astronaut (https://twitter.com/tiny_astro_naut), which inserts spaceship emoji into Tiny star fields’ tweets, or its conceptual sibling, tiny space poo (https://twitter.com/tiny_space_poo).

How many of your bot’s followers do you reckon are other bots, and is bot-to-bot interaction different to how humans interact with bots?

I haven’t done the numbers, but it seems like there is a slightly higher percentage of bot-to-bot followers than human-to-bot. I would guess this combines auto-following routines and being manually directed to follow entire lists of other bots. Perhaps also, they are more patient with repetitive or nonsensical tweets and stick around longer.

Most bots now have conversational abandonment built in, but this was not always the case- it was once pretty common to see two replying bots get into a conversation with one another that would last hours or days, to the tune of thousands of tweets, one every few seconds. I once got accidentally caught in mentioning one of these cycles and had to wait for one of the bot’s owners to wake up and reset their servers. It was amazing, and I also had to turn off all notifications on every device I own.

Now, I think most bots use more intelligent replying- just to one person, randomly across their followers, or only every 10 hours, or perhaps replying to keywords or requests. To me, this has made bot-to-bot interactions feel a lot more human.

Do people ever wonder about you, the human behind the bot?

Many people who follow Tiny Star Fields do not understand that it is a bot! Or that bots are even on Twitter. The predominant interaction that seems to occur runs along the lines of “DO YOU SLEEP” or “what is this” or “I love these thank you so much for making them all the time”. I find that disconnect pretty delightful- the assumption of a (very) dedicated human somewhere. I’m also fond of the interpersonal conversations in the comments, often having nothing to do with the original stars; it occasionally functions as a bit of a forum for strangers to connect.

Where do you see Twitter bots or social media bots generally evolving?

I have found myself moving off of Twitter and back into non-social spaces for much of my work. Part of this is probably personal; my interests shift project-to-project. Part of it is intrinsic limitations in the media, the 140-character limit, and the difficulty of keeping up with Twitter’s often evolving terms of service. I am interested in physical robots or the housing of digital spaces- where these bots live- and a lot of my studio practice is now exploring tangible machines. Some of the best bots I’m seeing out of others use neural nets or very clever source material. In my own work, I am looking forward to more physical-digital integration, especially as I pick up some new toolsets required for more complicated work. I am interested in biological emulation and the hidden data that Twitter links to every tweet (perhaps my next bot will not be readable on the Twitter web client but instead comes alive in an API call?).

A small part of me also feels like others have taken up the call (and doing it better than I ever could have). This is to say, Twitter bots are in a kind of renaissance- tools like George Buckenham’s Cheap Bots Done Quick (which uses Kate Compton’s Tracery) and the plethora of tutorials and frameworks have radically democratized the process, and it seems like every day I see someone new to this space building interesting or beautiful things. I am learning as much from newcomers to the form as anything!

In short, for the future- who knows? But now, bots are serving as a fascinating space to test new ideas, construct entities and artwork of generated text and data, and publish those experiments to an audience excited to see them in the world. What more could one hope for?

Finally, what are your favourite bots at the moment?

https://twitter.com/CreatureList – automata bestiary from @samteebee

https://twitter.com/FFD8FFDB – image-processed security cameras by @derekarnold

https://twitter.com/imgconvos – a @thricedotted answer to image-bot loops

https://twitter.com/everycolorbot – The first bot truly dear to me still going strong, thanks to @vogon

https://twitter.com/reverseocr – a @tinysubversions bot that randomly draws until it hits whatever word it is trying to match in an OCR library

https://twitter.com/ARealRiver – the only real way to view this (very clever) bot is in its own timeline, probably on mobile. from @muffinista

https://twitter.com/LSystemBot – l systems by @objelisks

https://twitter.com/INTERESTING_JPG – a bot-form of deep learning, which attempts to describe human images with computer vision, by @cmyr

https://twitter.com/park_your_car – compelling use of google maps highlighting available car space by @elibrody

https://twitter.com/wikishoutouts – shoutouts to the disambiguation pages of Wikipedia

https://twitter.com/soft_focuses – a very quiet mysterious bot from @thricedotted

https://twitter.com/TVCommentBot – attempted image recognition of television, @DavidLublin

https://twitter.com/GenerateACat – procedural cats – @mousefountain and @bzgeb

https://twitter.com/pentametron – a bot that looks for tweets in accidental iambic pentameter by @ranjit

https://twitter.com/RestroomGender – @lichlike’s gendered restroom sign generator

https://twitter.com/digital_henge – This bot by @alicemazzy tweets moon phases, eclipses, and other solar and lunar phenomena

https://twitter.com/a_lovely_cloud – digital cloud watching from @rainshapes

https://twitter.com/the_ephemerides – computer-generated poetry with outer space probe imagery, @aparrish

To find out more about Everest Pipkin’s latest projects, please visit Everest Pipkin

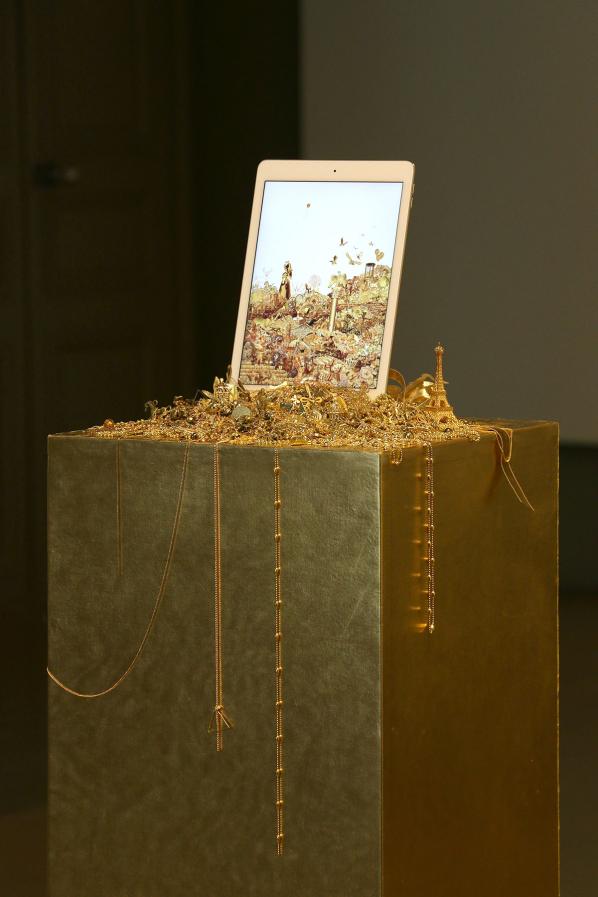

French artists Émilie Brout and Maxime Marion contribute three pieces to The Human Face of Cryptoeconomies exhibition. Gold and Glitter is a painstakingly assembled installation of collaged GIFs. Previous installations have featured the GIFs displayed on a gold iPad atop a pile of collected gold trinkets; at Furtherfield Gallery now a single golden helium balloon hovers in front of a floor to ceiling projection. Nakamoto (The Proof) is video documentation of the artists’ efforts to try and place a face on the elusive Bitcoin creator, Satoshi Nakamoto (but is it his face in the end? We don’t know). Untitled SAS is a registered French company without employees and whose sole purpose is to exist as a work of art.

Brout and Marion’s work can be situated among artists and art practices who have grappled with how to think about value and objects—or more precisely, how objects are inscribed (and sometimes not) into an idea of what is valuable. In a recent article for Mute Magazine, authors Daniel Spaulding and Nicole Demby point out that “Value is a specific social relation that causes the products of labor to appear and to exchange as equivalents; it is not an all-penetrating miasma.”1 Value is a process by which bodies are sorted and edited but it is not a default spectrum on to which all bodies must fall in varying degrees. This clarification makes explicit the fact that while the relationships productive of value allow “products of labor to appear and to [be exchanged]”2 this is not an effect that is extended to all products of labor. Attempts to isolate the underlying logic of this sorting mechanism are often at the heart of art practices dealing with questions of value and commodification. Like Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes or Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, these artworks become interesting problematics for the question of art and value for the ways in which they are able to straddle two economic realms—that of the art object and the commercial object—while resisting total inclusion in either.

The Human Face of Cryptoeconomies picks up these themes in an art context and repositions them alongside digital cultures and emerging digital economies. In Brout and Marion’s work alone, concepts of kitsch, identity, and human capital have been inhabited and imported from their originary realms into the digital. Answering questions remotely, Brout and Marion were kind enough to give us some insights into their work and process. My goal here has been to draw out some points about the operation of value that are at work in Brout and Marion’s practice, as well as to point towards an idea of how value is transformed, or even mutated, in the digital age.

* * *

Brout and Marion open up with an interesting provocation. They explain, “When we showed the project [Glitter and Gold] in Paris this year, people stole a lot of objects, even if they were very cheap. Gold has an incredible power of attraction.”

It is telling, to some extent, that Brout and Marion’s meditations on gold have an almost direct link to the visual metaphor used by Clement Greenberg in his 1939 essay Avante-Garde and Kitsch to describe the relation between culture—epitomized in the avant-garde—and the ruling class. Greenberg writes, “No culture can develop without a social basis, without a source of stable income. And in the case of the avant-garde, this was provided by an elite among the ruling class of that society from which it assumed itself to be cut off, but to which it has always remained attached by an umbilical cord of gold.”3 This relation is subverted in Gold and Glitter, which takes for its currency—its umbilical cord of gold—a kind of unquantifiable labor that is seemingly (and perhaps somewhat sinisterly) always embedded in discussions of the digital.

For Greenberg, kitsch always existed in relation to the avant-garde; one fed and supported the other, even if the way in which that relation of sustenance worked was by negation. And while Greenberg’s theory relies on his own strict allegiances to hierarchical society, privileged classes, the values of private property, and all the other divisive tenets of capitalism that we now know all too well can be destructive. Kitsch remains useful to us for the ways in which it allows the means of production to enter into a consideration of aesthetics. Here the recent writing of Boris Groys can be useful. In an essay written for e-flux titled Art and Money, Groys makes a compelling case for why we should persist in a sympathetic reading of Greenberg. He argues that Greenberg’s incisions amongst the haves and have nots of culture can be cut across different lines; that because Greenberg identifies avant-garde art as art that is invested in demonstrating the way in which is it is made and it doesn’t allow for its evaluation by taste. Avant-garde art shows its guts to us all, and on equal terms—“its productive side, its poetics, the devices and practices that bring it into being” and inasmuch “should be analyzed according the same criteria as objects like cars, trains, or planes.”4

For Groys this distinction situates the avant-garde within a constructivist and productivist context, opening up artworks themselves to be appreciated for their production, or rather, “in terms that refer more to the activities of scientists and workers than to the lifestyle of the leisure class.”5 In this way Glitter and Gold, like Brout and Marion’s other artworks, is to be appreciated not for any transcendent reason but rather for the means by which it came into existence. ‘The processes of searching and collaging golden GIFs sit side by side with the physical work of accumulating the golden trinkets for display: “We collected these objects for a long time” the artists explain, “some were personal objects (child dolphin pendant, in true gold), others were given or found in flea markets, bought in bazaars … We wanted to have a lot of different types and symbols, from a Hand of Fatima to golden chain, skulls, butterflies, etc.”

Furthermore, Glitter and Gold can be understood as the product of compounding labors: the labor of Brout and Marion in collecting their artifacts, the labor necessary to create the artifacts, the labor of GIF artists, the labor of searching for said GIFs, the labor of weaving a digital collage. These on-going processes forge, trace, and re-trace paths during which, at some point, gold takes on the function as aesthetic shorthand for value. As Brout and Marion explain, “Here the question is more about the intrinsic values we all find in Gold, even when it just looks like gold. Gold turns any prosaic product into something desirable. [Gold and Glitter] is less about economics than about perceived value.”

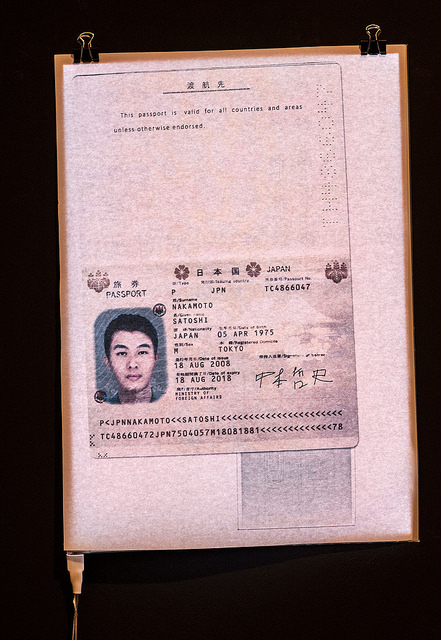

Groys provides his reading of Greenberg as a means of pointing towards a materiality that is always in excess of existing coordinates of value. If value always reveals the products of labor as they enter into a zone of exchange, it is something else proper to contemporary art that reveals another materiality beyond this exchange. For Groys, this something else is at work in the dynamics of art exhibition, which can render visible otherwise invisible forces and their material substrates. This is certainly a potential that is explored by Brout and Marion. In Nakamoto (The Proof), the viewer can watch the artists’ attempt at creating a passport for the infamous and elusive Bitcoin creator Satoshi Nakamoto. At present, it is unclear whether Nakamoto is a single person or group of people, though the Nakamoto legacy as creator of Bitcoin, a virtual currency widely used on darknets, is larger than life. Adding to this myth, after publishing the paper to kickstart bitcoin via the Cryptography Mailing List in 2008, and launching the Bitcoin software client in 2009, Nakamoto has only sporadically been seen participating in the project with others via mailing lists before making a final, formal disappearance in 2011, explaining that he/she/they had “moved on to other things.”6 Nakamoto’s disappearance, coupled with the fact that Nakamoto’s estimated net worth must be somewhere in the hundred millions Euros, has given rise to the modern-day myth of Nakamoto, and with it an insatiable curiosity to uncover the identity and whereabouts of the elusive Bitcoin creator.

Brout and Marion make their own attempt to summons the mysterious Nakamoto back to life by putting together the evidence of Nakamoto’s existence and procuring a Japanese passport using none other than the technologies that Nakamoto’s Bitcoin both imparted and facilitated. When asked if they feared for their own self-preservation in seeing this project through, Brout and Marion answered, “Yes, even if we were pretty sure that it would be easy to prove our intention to the authorities, and that the fake passport couldn’t be useful to anybody, buying a fake passport is still illegal.” They add, “But we also wanted to play the game entirely, so we made every possible effort to preserve our anonymity during our journey on the darknets.”

However Brout and Marion have yet to receive the passport; as they explain, “The last time we received information, the document was in transit at the Romanian border.” When asked if they expect to receive the passport, they respond, “No, today we think we will never receive it. We are completely sure that it has existed, but we’ll surely never know what happened to it.” What, then, will they do if they never receive the passport? “Maybe just continue to exhibit the only proof of it we have!” they exclaim. “There is something beautiful in it: we tried to create a physical proof of the existence of a contemporary myth, using digital technology and digital money, and the only thing we have is a scan!”

If Brout and Marion’s nonchalance seems unexpected then it is because the disappearance of the passport for the artists marks just another ebb in the overall flow of their piece; a flow that began with Nakamoto, coursed through their clandestine chats via a Tor networked browser and high security email, and now continues to trickle on while we wait in anticipation for the next chapter of the Nakamoto passport to reveal itself. In this respect, the anticipation of the passport is a poetic and unforeseen layer added to the significance of the piece: “Maybe it is even better [that the passport should not arrive]” Brout and Marion comment. “It’s like it was impossible to bring Nakamoto out of the digital world.”

If value is always formed by way of a social relation, then how do digital modes of sociality also deliver this effect? This becomes a particularly fraught question when considering that, as Anna Munster has written, the sociality that takes place on the internet can be understood as the interrelation of any number of subjectivities, both organic and inorganic. Brout and Marion’s ambivalence to the purloined passport highlights just such an expectation: “Here the lack of identity delivers a lot of value. Look at Snowden: journalists ask him more about his girlfriend than about his revelations. Making something as big as Bitcoin and staying perfectly anonymous? These are strong attacks to two of the most important issues of our societies: banks and privacy.” What their statement suggests is how a collective movement towards transgression, here seen as compounding maneuvers of avoidance of physical world boundaries and institutions, might hold within it the promise of its own set of value coordinates. As Brout and Marion further explain: “For us, Nakamoto is absolutely fascinating. The efforts he made to prevent himself from being turned into a product are incredible. Especially when you know the importance of [Bitcoin’s] creation, and that only a few men in the world are smart enough to create something like this. Adding to that the fact that Nakamoto is probably a millionaire, you have one of the only true contemporary myths, something hard to find credible even if it was just a fictional character in a movie. So this somewhat absurd attempt to create a proof of Nakamoto’s existence was, for us, an attempt to make a portrait of him, to put light on his figure. And, in some ways, a tribute.”

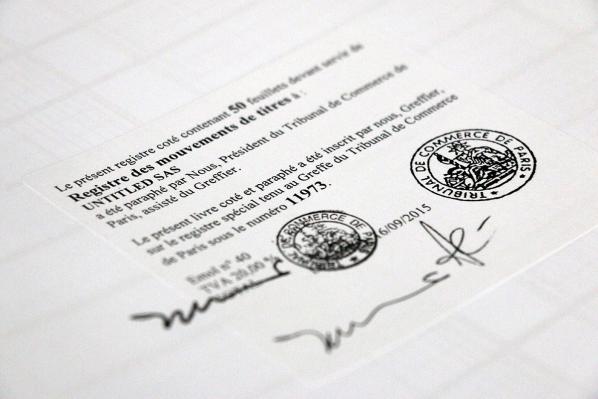

Brout and Marion mount a final probe into questions of value in their piece, Untitled SAS. Untitled SAS is the name for Brout and Marion’s corporation whose purpose and medium is to exist as a work of art. In France SAS means société par actions simplifée, and is the Anglophone equivalent of an LTD. SAS companies have shares that can be freely traded between shareholders. Untitled SAS, in Brout and Marion’s own words, “has no other purpose than to be a work of art: it won’t buy or sell anything, there won’t be employees, its existence is an end it itself. The share capital of the company is 1 Euro (the minimum), and we edited 10,000 shares owned by us (5,000 for each one). Everybody can freely buy and sell shares of this company.” Brout and Marion are clear: in no uncertain terms, “Untitled SAS is a work of art where the medium is a real company, and the corporate purpose of this company is simply to be a work of art.”

Untitled SAS is a tongue in cheek commentary on the situating of artworks as outside of the rational space of the market while still being subject to selective norms of economic behavior. Brout and Marion explain, “Untitled SASis obviously a metaphor for the art market, and the market in general: it is a true, fully legal, and functional speculation bubble. Companies usually try to create some concrete value, they are means. The art world has fewer rules than the regular market, the price of some artworks can radically change in few days without any logical reason: their intrinsic value is completely uncorrelated to their market value. We wanted to reproduce and play with these systems in the scale of an artwork.” At this level, what Brout and Marion uncover is further proof of the condition of the contemporary art period as Groys sees it: a time in which “mass artistic production [follows] an era of mass art consumption” and by extension “means that today’s artist lives and works primarily among art producers—not among art consumers.”7

Crucially, the effect of this condition is that contemporary professional artists “investigate and manifest mass art production, not elitist or mass art consumption.” This is the mode of art making precisely employed by Brout and Marion in the creation of Untitled SAS. It has the added effect, too, of creating an artwork that can exist outside the problem of taste and aesthetic attitude. Companies tend to eschew taste qualifications in favor of brand associations. Untitled SAS becomes readable as an artwork, as Untitled SAS, when the expectations and regulations of a nationally recognized business are made to butt up against the inconsistencies of the artworld as an economic sphere. The art object then becomes rather a means of accessing the overlapping paths of art and value as they are uniquely enabled to circulate in and out of the art & Capitalist markets.

* * *

Brout and Marion note that, “In our work we often use algorithms and generative ways to produce things, but here we wanted to something no machine can do, something hand-made, too, finally a simple and traditional work of art.” These kinds of generative technological processes and sorting algorithms have been central to many debates on how contemporary culture is absorbing the boon of big data: from ethical questions on predictive policing to dating apps and ride-hailing startups. As one Slate article posed the question in relation to Uber, these algorithms are more than just quick and efficient modes of labor—they are reflections of the marketplace themselves.

So what, then, might it mean that both values and services in the digital age are predicated on the power to sort and categorize, and that this power is ciphered through its own dynamic of social relations, but that in one scenario what emerges is a sphere of the valuable and in the other a software that asserts itself as benign and at the behest of an impartial, impersonal data? Perhaps the rationality of value and market circulation vis a vis the art object was always going to be a little too tricky to take on: too many exceptions, too many questions of subjectivity, taste, and judgment. But as the works exhibited for The Human Face of Cryptoeconomies might suggest the rationality of value and the products it chooses to incorporate is of high importance. If value works precisely because of the specific interrelating of social subjects then we can consider the realm of the digital as a concentrated form of such a relation.

Against this we must consider the new subject that is produced and addressed by the intersecting of these discussions. Spaulding and Demby make the case that, that “Art under capitalism is a good model of the freedom that posits the subject as an abstract bundle of legal rights assuring formal equality while ignoring a material reality determined by other forms of systematic inequality.”8 Karen Gregory, in The Datalogical Turn, writes, “In the case of personal data, it is not the details of that data or a single digital trail that are important, it is rather the relationship of the emergent attitudes of digital trails en mass that allow for both the broadly sweeping and the particularised modes of affective measure and control. Big data doesn’t care about ‘you’ so much as the bits of seemingly random information that bodies generate or that they leave as a data trail”.

The works of Brout and Marion exhibited at the Human Face of Crypotoeconomies exhibition places the intimacy of the body front and center. They speak to the shadow and trace of the body by appropriating the paths of the faceless, or by giving a face to the man (or entity) without a body, to becoming the human face of the market player par excellence by inserting themselves into a solipsistic art corporation. Brout and Marion’s practice understands that while value may not be an all-penetrating miasma, this is not also to say that the effect of value is not still inscribed on the flesh of each and all, organic or not.

1 Demby, “Art, Value, and the Freedom Fetish | Mute.”

2 Ibid.

3 Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” 543.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 “Who Is Satoshi Nakamoto?”

7 Groys, “Art and Money.”

8 Ibid.

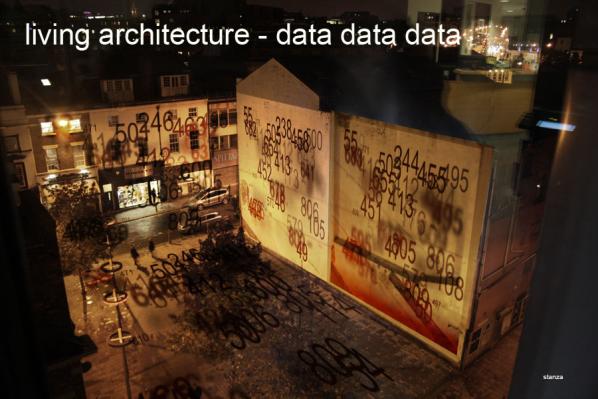

Stanza is an internationally recognised artist who has been exhibiting worldwide since 1984. He has won so many prizes you’d have trouble fitting them all on one mantlepiece. He has exhibited over fifty exhibitions globally and is an expert in arts technology, CCTV, online networks, touch screens, environmental sensors, and interaction. His artworks examine artistic and technical perspectives, within the contexts of architecture, data spaces and online environments.

Recurring themes throughout his career include the urban landscape, surveillance culture, privacy and alienation in the city. Stanza is interested in the patterns we leave behind, and real time networked events, that are usually re-imagined and sourced for information. He uses multiple new technologies so to create distances between real time, multi point perspectives that emphasis a new visual space. The purpose of this is to communicate feelings and emotions that we encounter daily which impact on our lives and which are outside our control.

Much of his work has centered on the idea of the city as a display system and various projects have been made using live data, the use of live data in architectural space, and how it can be made into meaningful representations. See Publicity, Robotica, Sensity, as well as a whole series of work manipulating real time CCTV data to making artworks with them: See, Velocity, Authenticity, Urban Generation. These works reform the data, work with the idea of bringing data from outside into the inside, and then present it back out again in open ended systems where the public is often engaged in or directly embedded in the artwork. Interactive and visually appealing, his style also maintains the substantive power through multi-facetted content.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Stanza: I don’t really get inspiration from the “who” question, I prefer the “what” and “why” questions. As a professional artist I look at loads of art so to understand what art is and can be, and it’s always an ever changing and fluid response. I also spend a lot of time ignoring stuff and material; (focused ignoring) because it has become harder and harder to see though the fog; the noise of it all. Maybe it’s better to think of a working model for inspiration, Andy Warhol had one. Just make the work. That’s what I do. I am not a part time artist in academia or an artist with another job, I’ve done this for the last thirty years, inspired by and in response to the world around me.

This dogmatic commitment to my work comes from my believes that the system you have to trust and invest in yourself. Inspiration, quite literally is everything all around you all at once, all at the same time, moment by moment. This is what inspires my work and it influences the creation of real time information flows, and works in parallel realities. It allows me to stand back at a distance and work with complex data sets while at the same time making meaning from them. Forming data into a shape, because this confluence might inspire a repositioning of thought and values while at the same time unlocking a hidden meaning to enable the viewer to feel and experience something new or to do something creative with the results.

MG: How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

S: There’s a saying be careful what you wish for. If one reverses this then it could be wish for what you want and need. Influence is problematic because it’s both negative and positive. The idea of influence seems causal, but my own practise isn’t based on influence but in research into certain themes. This enables me to get into both sides of particular questions or debate, so to frame the work I make. Works like these have been inspired by this focus…

The Singing Trees, focus in the invisible things and the environment http://stanza.co.uk/tree/index.html

MG: How different is your work from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

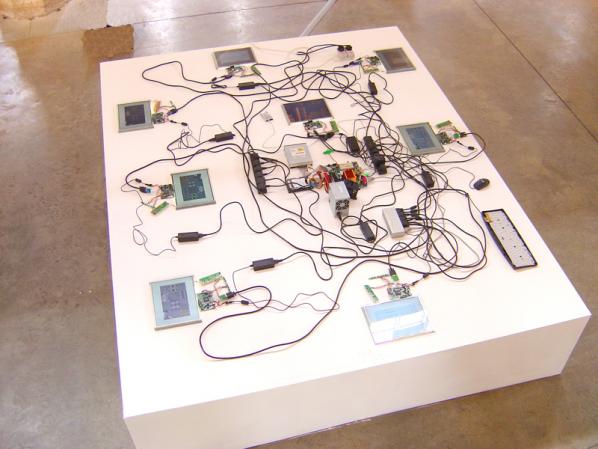

S: I have been researching smart cites, urbanisn, and have collected ‘big data’ since 2004. I have been building my own wireless sensor network. This eventually manifested itself in an artwork called Capacities in 2010 which then influenced all the others in the series until it now has this form.

Capacities: Life In The Emergent City, captures the changes over time in the environment (city) and represents the changing life and complexity of space as an emergent artwork

http://stanza.co.uk/capacities/index.html

Which led to…

The Nemesis Machine- From Metropolis to Megalopolis to Ecumenopolis.

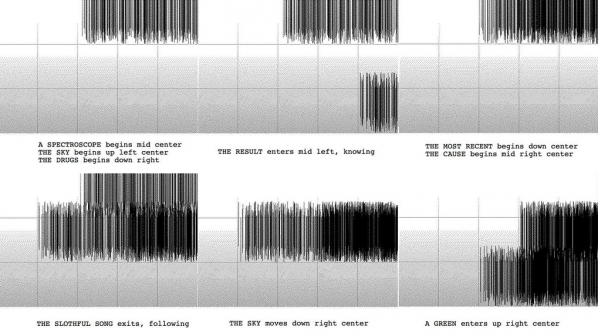

“A Mini, Mechanical Metropolis Runs On Real-Time Urban Data. The artwork captures the changes over time in the environment (city) and represents the changing life and complexity of space as an emergent artwork. The artwork explores new ways of thinking about life, emergence and interaction within public space. The project uses environmental monitoring technologies and security based technologies, to question audiences’ experiences of real time events and create visualizations of life as it unfolds. The installation goes beyond simple single user interaction to monitor and survey in real time the whole city and entirely represent the complexities of the real time city as a shifting morphing complex system.

The data and their interactions – that is, the events occurring in the environment that surrounds and envelops the installation – are translated into the force that brings the electronic city to life by causing movement and change – that is, new events and actions – to occur. In this way the city performs itself in real time through its physical avatar or electronic double: The city performs itself through an-other city. Cause and effect become apparent in a discreet, intuitive manner, when certain events that occur in the real city cause certain other events to occur in its completely different, but seamlessly incorporated, double. The avatar city is not only controlled by the real city in terms of its function and operation, but also utterly dependent upon it for its existence.”

MG: Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

S: It’s the museum I would like to change or engage with. It seems that anything and everything will end up in the museum. We have become the museum. We are the sum of our collections catalogs and archives. Since the current trend is for public engagement we will see a mix of these new technologies aiding and abetting this and various dialogues.

Therefore these questions need to be raised more vocally. How do visitors interact with each other and artworks? How do visitors behave in public space and what patterns or communities do they form. Can these outputs reshape our experience of public space and the art?

So, new immersive technologies could be used to investigate how visitors interact with art works, with each other and what impact their experiences have in forming new user interactions within public space. This space could be made more social and lead to new real time artworks based on visitor interaction and new visualizations of the gallery space based on gathered data.

Artists used to occupy specific issues but now there aren’t many topics artists haven’t engaged in or reached out to. The issues that will resonate will be the ones closest to the issue of the day…. and, they will be economics, the environment and migration. Because of this I would like to less focus on public engagement spectacle or entertainment and more on the quality and public engagement rooted in intellectual rigour.

Technology affords new ways of working with audiences and curators as participants in artworks. The concept of the exhibition as an active site for experimentation and collaboration between curators, artists and audiences prefigures a general cultural movement towards the centrality of experience and away from the reification of the object.

However, how audience activities and movements can be used as the subject of new artwork as well as modify engagement with existing collections is a cultural and technological challenge.

SeePublic Domain: You Are My Property, My Data, My Art, My Love.

The Public Domain Series involves using live CCTV systems that are already installed then using these cameras to enhance gallery space and the audiences experience of the gallery. http://stanza.co.uk/public_domain_outside/index.html

Visitors to a Gallery – referential self, embedded. Stanza uses a live CCTV system inside an art gallery to create a responsive mediated architecture. Anyone in any of the galleries and all spaces in the building can appear inside the artwork at any time.

http://stanza.co.uk/cctv_web/index.html

The social challenge within urban space is one I like to play with. In The Binary Graffiti Club, is a project I set up to try and work in this area. The Binary Graffiti Club are invited members of the public at each location for each event; they are given the hoodie to keep as thanks for their participation and contribution. The Binary Graffiti Club set off across the city and create artworks.

http://stanza.co.uk/binary_club/index.html

“Youths dressed in black hoodies swarmed the historic city streets of Lincoln during Frequency Festival 2013, their backs emblazoned with bold white digits, the zeros and ones. Their ominous presence was marked with a series of binary code graff-tags on official buildings throughout the city; messages of insurrection for a digital cult now active among us or analogue reminders of the digital soup of signals we wade through on a daily basis? There’s an engaging playfulness and an aesthetic pleasure to Stanza’s work that pays rewards on deeper investigation. His urban interventions remind us of the invisible occupation of the cyberspace around us and encourages us to ask whose hand manipulates these systems of control.” Barry Hale, Festival Co-Director of Frequency Festival 2013: Stanza: Timescapes/Binary Graffiti Club.

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

The invention of the toothpaste tube caused a revolution in painting.

The greatest discovery of the age was that the world is full of atoms.

Doing many small things instead one on big thing.

We seam to victimise out children we give them ASBO’S and anti social behaviour orders. For a while I wanted one. They actually give you a certificate like rockers, mods punks etc. The hoodie is a symbol of youth culture as well as being anti social. My new artwork the Reader and the idea of reading books and being anti-social led to this project.

The Reader is a large six foot sculpture of the artist Stanza wearing a hoodie reading a book. The artwork is a metaphor for the engagement of reading in the digital age. The sculpture acts as a focal point for community and public engagement and has taken over one year to make and design; it has been commissioned to act as a focal point for the identity of the library. The reader reads all the books published since 1953 inside a data body sculpture. http://stanza.co.uk/TheReader_web/

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and or social change?

S: Make work, make more work, and remember nothing lasts forever except true love.

Re: Art, Study it

Re: Technology. Learn it

Re: Social change . Be part of it.

MG: Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

Yes the Books…

The Bible The Quran And The Torah.

Because…they are the most influential books ever written and have guided the lives of billions so it’s a good idea to have had a read… at least “view” them.

See…

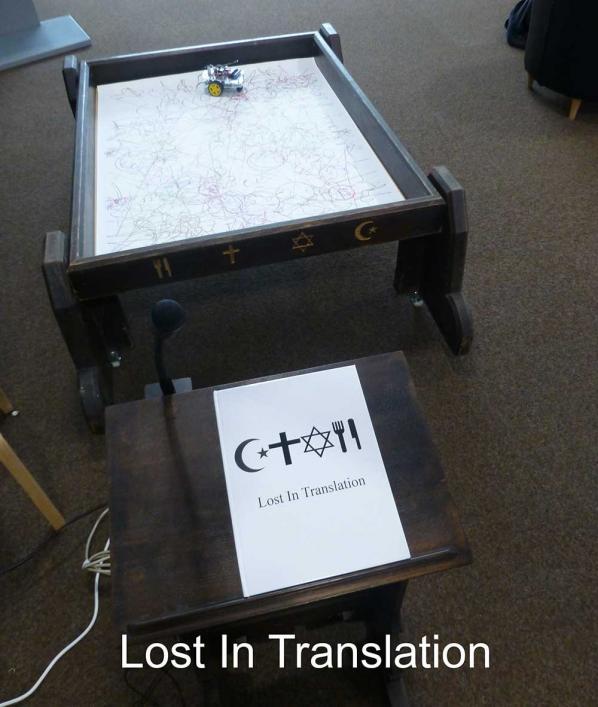

Lost in Translation. This custom made robot responds to a series of texts and makes drawings unique to each reader. The work questions not only the meaning and interpretation of text but just who controls our understanding of the outputs and indeed what is Lost In Translation. This is a very playful user friendly work and actively engages the audience not only to think about the text but the meaning of how automation and networked technology is changing the control of understanding. http://stanza.co.uk/lost_in_translation/

Thank you…

The negotiation of the commons takes place in two distinct realms that are increasingly reaching into and shaping one another: the long history of the landscape commons both in cities and in the countryside, and across digital networks. In both realms we find the continued project of the enclosures, appropriating forms of collectively-created use value and converting it, wherever possible, into exchange value. In this conversation Ruth Catlow and Tim Waterman discuss the ‘Reading the Commons’ project together with Furtherfield’s work on understanding the commons.

Ruth Catlow is an artist and co-founder co-director of Furtherfield. Tim Waterman is a landscape architectural and urban theorist and critic at the University of Greenwich and Research Associate for Landscape and Commons at Furtherfield.

*

TW: I’ll start with a little background. ‘Reading the Commons’ is an ongoing project which we initiated that seeks to find a place of power in order to defend the continual project of the creation of the commons in all realms in the future and to augment and magnify other similar endeavours by other groups and organisations. We knew that there is already a lot of work being done in and around the idea of the commons, so we were less interested in staking out any intellectual ground than we were in making connections and finding ways of sharing research and experiences amongst ourselves and other interested parties. So far two groups have been assembled to read and discuss. The first was convened in the summer of 2014 at Furtherfield Commons, the community lab space in the South West corner of Finsbury Park, and was composed of a broad range of academics and practitioners from different disciplines.[1] It met once a fortnight for several months and discussion was wide-ranging. The second was in the Summer of 2015 and involved a group of Master’s students in curation at Goldsmiths under the direction of Ele Carpenter. Future incarnations of the group will each try for different configurations of people, disciplines, and callings.

RC: The first group was very diverse – from backgrounds in geography, sociology, law, political science, technology, landscape architecture, art, and more. We faced an immediate challenge talking across the boundaries of all these disciplines and philosophical and cultural traditions. This was illustrated immediately in the first session. One of our group, a scholar in Law and Property, was irked by our early introduction of two Americans , Garrett Hardin and Yochai Benkler. We had introduced these theorists along with Elinor Ostrom, Oliver Goldsmith and Michel Bauwens.[2] The law and property scholar was irked for a number of reasons, but particularly because they represented a bias towards a US and UK (English speaking) over other European traditions- of property and ownership over civil liberties. Another participant, with an established practice in arts and technology looked pained throughout. I think this was because we seemed to be scratching the surface of topics, works and discussions that make up the discourse around the network, and the digital commons.

TW: We partially remedied this problem by asking the participants to provide readings for future sections and to give a brief verbal introduction.

RC: For instance Christian Nold led a show-and-tell at the second session, based on a book, Autopsy of an Island Currency (2014) that he had worked on with Nathalie Aubret and Susanne Jaschko. The book problematises a project called Suomenlinna Money Lab, a participatory art and design project that worked with money and local currencies as a social and artistic medium and that sought to involve a community of people in a critique of its own economies. This reinforced for me the contribution that situated practices have to make to theories of the commons, as the book tells a revealing story of resistance to critique in a place and community with an established interest and investment in the cultures associated with private ownership.

TW: Nevertheless there were a lot of times when people ‘looked pained’, because basically we had just jumped in and started discussing the idea of the commons without realising that we were all speaking with different understandings of basic terms. In other words, we were all operating on different registers that sprang from our hailing from different philosophical and disciplinary roots and traditions. It might have benefited us to begin by trying to map out our terms. On the other hand, this might have prevented us from ever even starting! This mapping, perhaps, is a project that we need to figure out how to undertake.

RC: The difficulty of wrangling different registers was also exacerbated by the seemingly unbounded scope of the discussion. The relatively recent growth of the World Wide Web introduces enough material for months of readings about how the digital commons has helped to shift thinking about the commons away from merely the management of material resources to knowledge and cultural work.

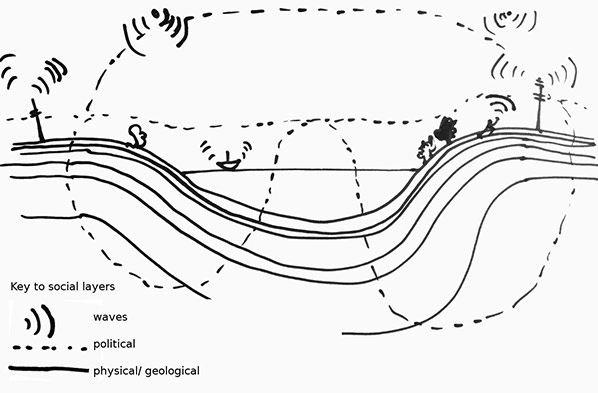

Still, we felt – perhaps because Furtherfield’s physical venues are located within a public park – a sense of urgency to think about the social layers of physical and digital space in relation to the commons, as a way to resist the unquestioning total commercialisation of all realms.

RC: To take a couple of steps back….There are misconceptions about the commons that require rectification. Political economist Elinor Ostrom showed, in opposition to Garrett Hardin, that in theory and in practice, the collective co-operative management of shared socio-ecological resources was a lived reality in many localities (1990). While her research drew on management of material resources her Eight Design Principles for Common Pool Resources, shares many characteristics with digital commons.

Hardin’s (1968) essay “The Tragedy of the Commons” had argued that commonly owned resources were doomed to exploitation and depletion by private individuals; therefore justifying the role of hierarchical, centralised systems of power to maintain private ownership. On the other hand, Jeremy Gilbert in his book Common Ground (2013), quotes radical economist Massimo de Angelis, to define the commons as social spheres which help protect us from the market. This becomes particularly useful to help us to recalibrate our definitions of “free” and “sharing” as we reveal so much of our private lives (so nonchalantly) via ubiquitous, proprietary digital devices and commercial social platforms.

TW: Hardin’s one-dimensional projection of the commons as unworkable and disastrous was based upon an understanding of human relations that assumed that competitive individualism is ‘human nature’ and that all such ‘experiments’ were doomed to failure as a result. This is Darwin’s survival of the fittest rendered as ‘dog eat dog’. The voice almost contemporary with Darwin’s that I think most clearly articulates how evolution (human and otherwise) is based upon cooperation is Peter Kropotkin’s, in his amazing book Mutual Aid (1902). Evolutionary science and theory is moving ever more towards Kropotkin’s conclusions rather than Darwin’s, or at least Kropotkin’s work is becoming ever more relevant and complementary to Darwin’s. For me, it’s also impossible to imagine how cultural evolution could work at all except through the cooperation, sharing, and processes of negotiation that characterise the commons.

The landscape commons has always been about more than just material resources, and this is perhaps the most reductively oversimplified register on which we might speak of the commons. So if the problem is to align the different and more meaningful registers along which we all discuss the commons so that a truly collective and collaborative project can emerge amongst many disciplines simultaneously, we should have a go at pinning in place a few core understandings of the commons? Shall we give that a go?

RC: Yes! From my work with Furtherfield, my feeling for the commons is strongly influenced by the cultures of freedom and openness in engineering and software. In 2011 we created a collection of artworks, texts and resources about freedom and openness in the arts in the age of the Internet. “Freedom to collaborate – to use, modify and redistribute ideas, artworks, experiences, media and tools. Openness to the ideas and contributions of others, and new ways of organising and making decisions together.”[3]

If we can agree that the commons are those resources that are collectively produced and managed by, and in the interests of, the people who use them, then the digital commons, as set out by Felix Stalder, are the technologies, knowledge and digital cultural resources that are communally designed, distributed and owned : wikis, open-source software and licensing, and open cultural works and knowledge repositories.[4] Licences such as the GNU General Public License and various Creative Commons licenses ensure that the freedom to use, adapt and distribute works produced collectively is preserved for the future.

Discussions of the commons have, in the liberal tradition, centred around how to produce, manage and share scarce material resources in a bounded geographical locality. This is fundamentally changed in the post-industrial, information age, where cultural and knowledge goods can be easily, cheaply and quickly copied, shared worldwide and transformed. It has brought about a massive shift in the way economics, politics and law are practiced.

As distinct from the users of the majority of corporately-owned search, sales and social media utilities (think Google, Amazon, Paypal, Facebook, Twitter) and digital entertainment platforms (think Netflix, iMusic and Spotify) the community of people involved in developing the digital commons ‘can intervene in the design and governance of their interaction processes and of their shared resources’ (Stalder) – think Wikipedia, Freesound, Wikihouse. This has long continued to be an area of intense critical inquiry, unfolding, and practice for artists who are creating digital and networked artworks that take the form of platforms, software, tools and interventions such as : Upstage software for online “cyberformance”; Naked on Pluto, an online game whose ‘players’ become unwitting agents in the invasion of their own and others’ privacy ; and PureDyne, the USB-bootable GNU/Linux operating system for creative multimedia.

Consumer cultures invite us constantly to outsource responsibility for knowledge, information and cultural works to the markets. Artists and technologists involved in the digital commons make these otherwise abstract (and often invisible) shifts in power and social relations “feelable” for more people. In this way they are asserting alternatives to the prevailing economic models – often privileging collaboration and free expression that disrupt outmoded models of copyright and intellectual property.[5]

Discussions about the role of affect in the development of the commons will be the subject of the next explorations of Reading the Commons, and we will certainly come back to these.

TW: Let’s look at this from another direction. In landscape terms, the idea of the commons has evolved a great deal over time, as, for example, feudal forms gave way to different hierarchical forms based in capitalism and private property, and now in late capitalism and neoliberalism’s adaptation to, and cooptation of various forms of horizontality, especially in managerial practices. The importance of the commons has also shifted from defining notions of shared ownership and management of agrarian resources to include various manifestations of urban life, most recently and compellingly, perhaps, in the dogmatically horizontal democratic organisation amongst participants in the Occupy movement.

Ultimately, the commons, for me, is about dialogue, sharing, and the relationship between people and place. The earliest expressions of the commons were all about our relationship with food; its procurement, preparation, and consumption. A beautiful historic example is the importance of the chestnut tree to the inhabitants of the Cévennes in southern France, and how it not only embodied the commons, but symbolised it as well. It’s not possible to romanticise this story, as it’s one of very hardscrabble survival, but it does illustrate the point. As a staple food, the chestnut was a matter of survival for the inhabitants of the Cévennes. It would seem, metaphorically, that the idea of rootedness would follow naturally from this as a characteristic of the commons, but the reality is more nuanced. Chestnuts were introduced to the Cévennes by the Romans, and then tended centuries later by monks, who would share plants with the peasants with the expectation of future tithes. Labour-intensive chestnut orchards were farmed not just by locals, but by migrant workers as well. If we fast-forward to the 1960s, chestnuts were rediscovered by those wishing to get ‘back to the land’, reviving agricultural practices that had withered away during the years that capitalism had lured people from the countryside into towns.

This shows a very complex picture of the commons: one in which colonization and imperialism, monasticism, peasantry, migrant labour, and then finally arcadian anti-capitalist mythologies of the 1960s each play a part – and I’m skipping over a lot of historic detail and nuance. There is a tendency nowadays to see the commons as exclusively autonomous and horizontal, but historically the commons have been inextricably bound to patterns of ownership and domination. Far from discounting the commons, this shows how the commons can exist within and exert pressure against prevailing forms of domination and ownership. We need not wait for total revolution or the construction of utopia or arcadia. We can get to work now and make a shining example of what is possible, making use of existing networks and existing places. The anthropologist David Graeber, in his book The Democracy Project, (2014) calls this ‘prefigurative politics’: the idea that by acting out the model of politics and human association and inhabitation that we wish to see, that we work to bring it about.

RC: Yes, and while sociality, rootedness and affinity are all associated with embodied experience, they bubble up again and again in the critical and activist media art community who take digital networks for their tools, inspiration and context. Take for example the Swedish artist/activist group Piratbyrån (The Bureau of Piracy) established in 2003 to promote the free sharing of information, culture and intellectual property. Their entire 2014 exhibition of online and physical installations at Furtherfield Gallery highlighted the centrality to their work of cultural sharing and affinity-building.[6] In his recent conversation with Tatiana Bazzichelli about networked disruption and business, Marc Garrett discusses the importance of affinities in evolving more imaginative, less oppositional (and macho) engagement with regressive forces; and quoting Donna Haraway says “Situated knowledges are about communities, not isolated individuals.”(Haraway 1996).[7]

But Tim, I think you were on a roll. Why don’t you keep going? Why is the commons important now?

TW: The exploitation of people and resources that marks the practices of contemporary capitalism is very much a continuation of the project of the enclosures, whether it is to skim value off creative projects, to asset-strip the public sector which is increasingly encroached upon by the private sector, or to exhaust land and oppress workers in the Third World. The commons, however, are being created continually, and they represent not just a resource to be enclosed and exploited, but a form of resistance that has particular power because it is lived and acted. It’s not at all a contradiction to say that what is common is simultaneously enclosed, exploited, and liberatory. It’s a matter of tipping the balance so that the creation of the commons outpaces its negation.

RC: As people negotiate systems for renewal and stewardship of the resources over time they also arrive at an expression of creative identity and shared values.

TW: A moral economy …

RC: By freely surrendering all collectively created culture, from use value for conversion to exchange value, our shared ecologies of knowledge, culture and land are dismantled.

And with this we stand to lose the ability to attend to the nature of co-evolving, interdependent entities (human and non-human) and conditions, for the healthy evolution and survival of our species.[8]