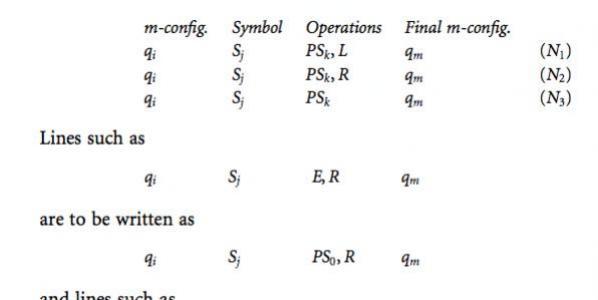

This conversation follows in a series of interviews with women who work at the intersection of art and technology. Amy Alexander’s work as an artist, performer, musician, and professorapproaches art and technology from a performing arts perspective, often examining intersections of art and popular culture.

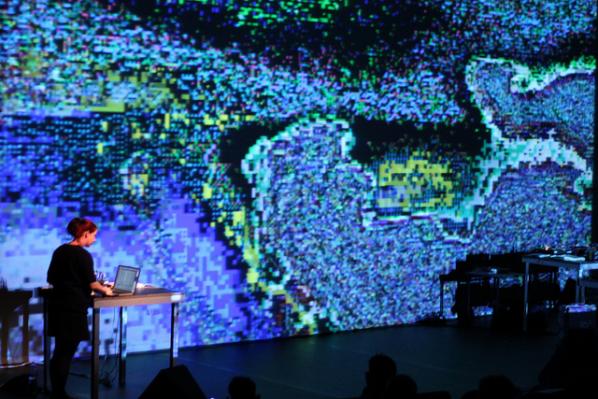

Amy Alexander is an artist and researcher working in audiovisual performance and digital media art. She has worked under a number of pseudonyms including VJ Übergeek and Cue P. Doll. Coming from a background in film and music, she learned programming and began making time and process-based art on the Internet in the mid-1990’s with the Multi-Cultural Recycler and plagiarist.org. Amy has performed and exhibited on the Internet, in clubs and on the street as well as in festivals and museums. Her work has appeared at venues ranging from the Whitney Museum and Ars Electronica to Minneapolis‚ First Avenue nightclub. She has written and lectured on software art and audiovisual performance, and she has served as a reviewer for festivals and commissions for new media art and computer music. She is an Associate Professor of Visual Arts at the University of California, San Diego. During summer/fall of 2012, Amy is Artist-in-residence at iotaCenter in Los Angeles.

Rachel Beth Egenhoefer: You’ve taken on many roles as an artist, musician, performer, coder, organizer, professor. How would you explain what you do to the “average Joe” who has not idea what a code artist is?

Amy Alexander: I usually don’t try to explain to people what a code artist is. I generally just tell them about the types of projects I or my students do, (“museum installation,” “club performance,” etc.) and what some of them are about. Then I explain that it’s done by writing software, building electronics, making videos, etc. But the point is more about the projects, not about how specifically they are made.

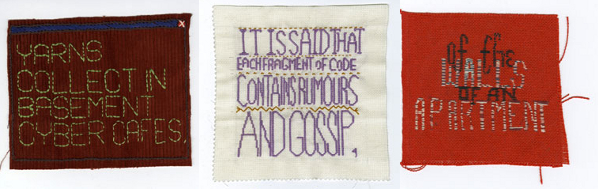

I also think talking about code-as-art is both less necessary and less difficult than it was five or ten years ago. What motivated me and a lot of other code artists back then was a concern that algorithms had a cultural impact that wasn’t well-recognized. Nowadays, people are familiar with the idea that Google sorts your search results in a particular way, websites you visit develop demographic profiles of you, etc. – they’re already concerned about algorithms. So I think it frees up both artists and audiences to focus on other aspects of the work. Of course, there are definitely some situations in which focusing on algorithms-as-art is important. Just like photographers sometimes focus on the nature of photographs, video artists on video, etc.

RBE: You’ve worked as yourself, as well as other performers such as Cue P. Doll and Übergeek. Can you describe the differences between some of your characters, and how do you see identity as a key element in your body of work?

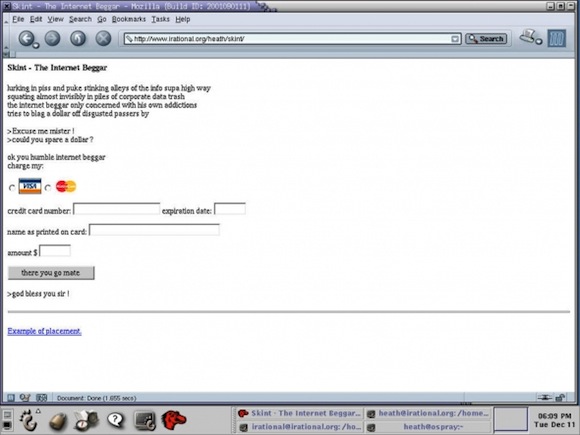

AA: Some of the online characters just evolved. I tend to anthropomorphize things, and I like to break into characters; I’ve just always done those things. So in some cases when I’m developing a project from a particular perspective, a character emerges who personifies that perspective. For example, The Original Plagiarist.org (1998) website was a collection of projects in which grandiose attempts to opportunistically plagiarize from the Internet always turned out to be transparent. So the character of Plagiarist emerged as the proud proprietor of this site and creator of all its projects – and the only person who couldn’t see the futility of the plagiarisms.

Übergeek is different, since I physically go out and perform as her. She’s both a theatrical character and actual club performer – in varying proportions depending on the context of the show. The theatrical character is a geeky rockstar wannabe. That opens up space for Übergeek to exaggeratedly escape the physical restrictions of performing on a computer – by waving around an “air mouse,” dancing on a DDR pad, etc. The club performer comes from my growing up performing music. I’d never thought about it, but the zone musicians go into to perform is really like playing a character. You have to become someone else. A few years ago I heard Steve Schick explain that when he has to perform a difficult piece of music, he imagines he’s someone else – and that other guy can play the piece. Eventually I realized that any performance of any kind I’d done that I’d been remotely satisfied with, whether music, VJ show, or performance art – I’d mentally become some other person. Going into character is really important, even if the character is just, “the performer.” It can be easy to forget the crossovers between performing arts and visual arts, but there’s a lot we can learn from one another.

RBE: Do you think this happens to us when we interact online, that we become performers? (Some people believe for instance that Facebook is really a performance of ourselves, not our real selves) Do you see any intersections of performance in “online” vs “physical/ in person” interactions? (I realize this gets into an entirely different question, the idea of intentional performance and unintentional, but perhaps you see an overlap?)

AA: I think there’s an overlap, but there’s also an overlap between the kind of “performances” we do online and those we do in “real life.” I don’t buy the dichotomy that the physical world is real/true and the online world is fake. We perform different sides of ourselves in different real life situations – work, friends, family, large group, small group, etc. Sometimes we perform more consciously than others. On the other hand, sometimes we feel less inhibited in online interactions, so we behave more naturally.

That’s not to say there’s no difference between online and offline interactions – but then again, these differences didn’t just suddenly emerge when the Internet came along. Think back to when people sometimes had pen pals by snail mail, for example. The relationships could be friendly, intimate, or performative. When things like immediacy and nonverbal communication disappear, that invites a different kind of behavior – be it more natural, more performative, or a combination.

RBE: What connections do you see between identity, code, and performance?

AA: I guess I’ve responded to identity & performance in the question above. As for code & performance: people have pointed out that code parallels musical notation, in that both are executable languages. If you think about scores by people like John Cage, where scores could actually be diagrams or verbal instructions to the performers, the connection between performance and instruction set becomes even clearer. This is interesting historically and theoretically, but for many of us who use code in performance, the connection becomes self-evident in practice. Code launches processes and actions, and performance *is* processes and actions, and there’s a back and forth between the performer and software. It’s not that much different for me performing software than performing a musical instrument; if I play violin, I finger, bow, pluck in various ways to get various sounds. You can think of the violin as interface, the notes and gestures as parameters, or whatever. But to be honest, trying to create precise analogies is a recipe for disaster. The point is, you perform both of them, and you have to learn how to do it. The difference with software is, you build your own instrument; that’s both a blessing and a curse. So you try to balance playability with flexibility, and so on. Because of my experience playing music, I keep trying to build ones that will accommodate clumsy performers like me!

RBE: Do you see all code as being “performed”? (Or perhaps is saying code is executable the same as saying code is performed?)

AA: It depends on which sense of the word “performed” you’re using. In the sense that means to do some sort of process – like to perform your job duties – yes. You can think of data as nouns and algorithms as action verbs. You “run” code, and though the physical metaphor might be an exaggeration, in general, some sort of an action happens. So in that sense, the processor is performing the code.

But in the other sense of the word – intentional performance, performing arts, performance art, etc. – running code is innately no more of a performance than breathing. People like John Cage have made interesting performances out of breathing, and people like Alex McLean have made interesting performances out of running code. But it’s not that way on its own, except in the Cagean sense of it being performance if you think of it that way. I think that’s interesting, but I’m personally more interested in code’s cultural, rather than formal, implications. In other words, I’m not so excited that processes are dynamic and self-repeating for their own sake. I’m more interested if, for example, that means we have increasing difficulty finding unpopular or obscure information online, because the popular perspectives have formed an algorithmic echo chamber.

RBE: Your newest work is using audiovisuals, performance, solar energy, and the history of dance in cinema. How did you arrive at this combination of ideas?

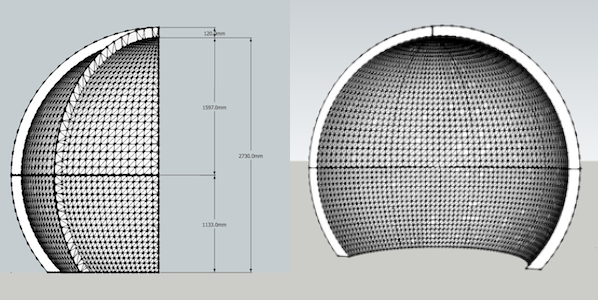

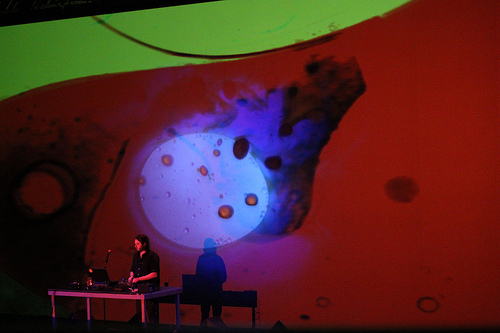

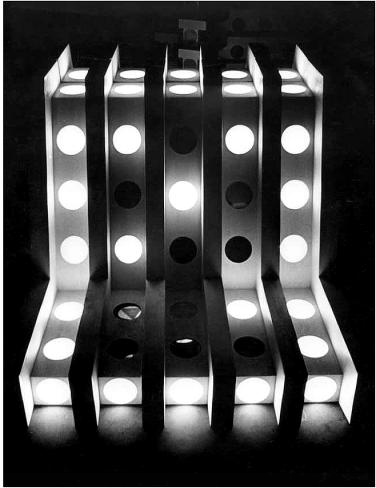

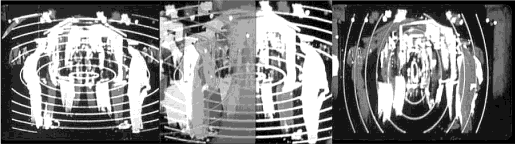

AA: The project is Discotrope: The Secret Nightlife of Solar Cells. It’s an audiovisual performance – a collaboration with Annina Rüst, with algorithmic sound design by Cristyn Magnus. There’s really two parts to the project: the projection system, and the content and performances that we develop for it. The system is a disco ball where some of the mirrors have been replaced by solar cells. The cells power the motor that turns the ball. We project video onto the ball instead of colored light. The result is, reflected, fragmented video images move around the room. Since the video projections “solar”-power the ball, the speed at which the images move around the room varies with the brightness of the images.

The way this all came about was I’d been interested in the philosophy behind hybrid cars and various other things – that when we “waste” energy, we might actually be creating it. I kept wondering if this idea could be applied to media somehow, and I kept trying various experiments with video: could the talking heads on cable news power an LED? etc. Never quite found the right outlet for this idea, though. At some point, Annina and I came across a disco ball, and we noticed the similarity between its mirrors and small solar cells. Then the idea of projecting videos onto it hit us, and it all came together as a “media-powered” system. Of course, that was just the general idea. After Annina built the initial prototype of ball, it took many hours working with it the studio for the “instrument” to reveal itself – i.e. how exactly does a video-powered disco ball become useful visually and performatively? Figuring that part out was just elbow grease – but getting from rough idea to what-is-this-really always is for me; I have to get my hands on things and play with them.

The content framework we’re working with for at least our initial round of performances is “the history of dancing ‘at’ cameras.” Since it’s a disco ball, we envisioned performing it at community dance parties, etc., and so people dancing seemed like the obvious thing to project. We started from the idea of projecting the people at the party onto it live – but we realized we also wanted to expand beyond that. Again, the elbow grease process: I’d try different clips of people dancing on YouTube, old movies, TV shows. Eventually a connection emerged between early cinema clips and contemporary YouTube clips. In both cases, people dance pretty much like vaudeville performers, directly for the audience – as opposed to cinematic narrative style, in which the viewer is a fly on the wall. In the dancing “at” cameras style, there’s a more direct, intimate connection between dancer and audience. We’ve written some things about this on the Discotrope blog – and I’ll probably write more there soon. Another thing we became interested in is how representation (gender, physical, etc.) does and doesn’t change from early movie camera demos and Hollywood films to YouTube, where people are generally self-cast and self-directed. And I’m really interested in the relationship between all of this and the muddy space between exhibitionism, voyeurism, and surveillance. That’s a theme that’s run through a number of my projects, and dancing at cameras certainly exemplifies that murkiness.

Of course, a lot of the dancing at cameras perspective relates to film history in general – cinema’s origins in theatre and vaudeville, the development of montage, etc. So it’s interesting to see it return with YouTube. Teresa Rizzo has written a really interesting article related to this called, YouTube: The New Cinema of Attractions.

RBE: When you say “people dancing at cameras” I immediately thought of surveillance cameras. Is your disco ball a type of surveillance camera?

AA: I’m really interested in the blurring between surveillance, exhibitionism, and voyeurism. The Multi-Cultural Recycler, SVEN, and CyberSpaceLand all hit on that theme in one way or another; this time it’s cinematic dancers. The cinema/YouTube performers who appear in Discotrope all knew they were on camera, so overtly it’s more about exhibitionism and voyeurism. Glamorous 1950’s female burlesque dancers did their strip tease acts for the camera; sixty years later, not-so-glamorous scantily-clad men proudly stomped through the Single Ladies dance on YouTube. One group does work-for-hire within the Hollywood studio system; the other does what they want. Does that make one voyeurism and the other exhibitionism, or is it more complicated than that? in some cases, we see the performers much differently than they probably saw themselves. Does that make it surveillance? I think it’s all very muddy, and that’s what I find interesting.

The flip side is that there are people in some of Discotrope’s YouTube videos doing things like dancing in Walmart, which gives the video a surveillance camera look even though it’s obviously not surveillance (in the traditional sense, at least.) People turn the tables on surveillance video and make their own production numbers in surveilled/controlled areas – for fun and as a type of resistance. That’s one of my favorite parts of Discotrope. Then we get to recreate those Walmart spaces in the big Discotrope projection. It makes it even more like an old Hollywood production number, and it makes it weirdly immersive. This is fun for us, because Walmarts are not the kind of thing normal people like to recreate immersively. 🙂

RBE: For this piece you are creating something for other people to perform with. Are there any differences for you in creating work that you will perform vs. others performing?

AA: Ah, those pesky multiple senses of “performance” again!. 🙂 I do the visual performances for Discotrope, so for now I’m primarily building the software system for myself to perform. So far Annina is the only other person who performs with the software. Like anything, it’d require some tweaking to be distributed for more general use, though I’ve tried to make it not too terrible in that regard. 🙂 More challenging/interesting might be for performers to get the feel for moving the ball – like anything, it takes practice to get proficient.

But perhaps you’re talking about performers in terms of the audience who can dance to Discotrope, or the parts of the show where audience members can dance on camera interactively. In this case, they’re both performer and audience at the same time. That’s an interesting challenge, because in designing the show, we have to think about them in both ways.

RBE: You are starting a residency at the iotaCenter in Los Angeles, what will you be working on there?

AA: It’ll be mainly exploratory/preliminary research; things will likely be changing/developing as I go along. But my general plan is to explore two threads: gestural and spatial cinematic performance. In performing CyberSpaceLand over the years, I found myself unconsciously developing certain gestural/structural performance techniques that were much different than what I’d consciously designed for the piece. That spawned some ideas about gesture, time and space that I’m going to try to take further. The spatial thread grew out of some things we’ve played with in Discotrope in terms of deconstructing cinematic narrative in a 360 degree space. I’ll be exploring these spatial cinema ideas both in regards to Discotrope and as broader research.

iotaCenter’s a great place for doing research in abstract / formal and experimental cinema, visual performance history, etc. They’ve got a terrific collection of films and texts. I’m hoping to also use the opportunity to get together with other experimental cinema and visual performance folks in LA. It’d be great to organize some fun/intellectually-stimulating/breathtakingly-earthshattering screening/performance events.

RBE: This interview is going to be part of a series of interviews with women working in art and technology. What do you consider to be important today about being a woman working in art & technology? Do you think it is still useful to discuss the female voice as a separate voice in the field?

AA: It’s a tricky subject, because we both need to hear women’s voices and avoid tokenizing or homogenizing them. Women artists working with technology do tend to have different perspectives than men, and there are far fewer of us. So often when the dominant themes emerge, they tend to be the “masculine” themes by virtue of sheer numbers. A corollary is that often women artists feel pressured to focus on gender issues or certain types of social issues. Again, it’s a problem of critical mass and self-perpetuating themes. Since a fair number of women are already involved with those topics and many women’s interests overlap there, they have momentum. But this ends up discouraging women from discussing or doing work on other topics they’re interested in, So, while we need to talk about shared experiences among women in art and technology, we also need to recognize that they have a diverse range of work and perspectives.

RBE: How have you seen perceptions of gender change through the years either in teaching, performing, or working as an artist?

AA: It’s interesting to think that the first programmers were women, and that at the time it was considered clerical work. (See Researcher reveals how “Computer Geeks” replaced “Computer Girls” by Brenda Frink.)

As men started to fill programming jobs, the perception of programming shifted. It became something “technical” that was somehow inherently “man’s work,” even though it had been clerical “women’s work” only a few decades earlier. I’ve seen something similar happen as a female computing artist. I think there are more of us now – at least we don’t seem to be the novelty we were ten or fifteen years ago. And I’ve seen a shift in attitudes and perception among undergraduate computing arts students: by now both the men and women have grown up playing video games and doing a variety of Internet activities that might have seemed like “boys-with-toys” pastimes a decade ago. So their perceptions of what they’re learning to do as computer artists is a little more open and less gendered. But unfortunately, there are still circular perceptions in all age groups that whatever technical work women are doing can’t be too serious by virtue of the fact that a woman did it. It would seem to parallel the current political debate in the US about the pay gap between women and men. There are always arguments that women’s jobs aren’t as demanding, and they usually end up with someone saying, “I can’t believe we’re still talking about this in 2012!” So on one hand, the more things change, the more they stay the same. On the other hand, as more women computing artists emerge, we’ll hopefully soon achieve sufficient critical mass for world domination. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

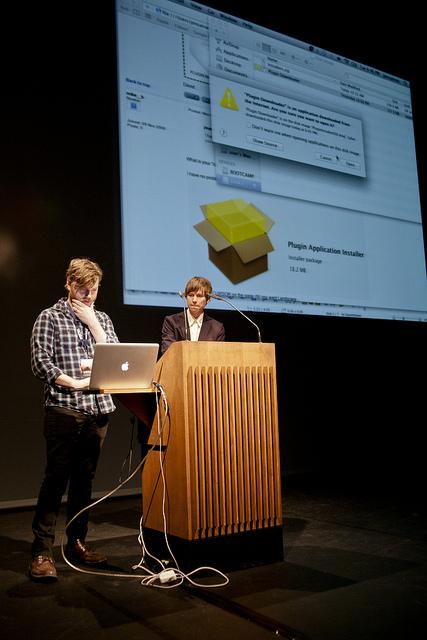

Andreas Broeckmann writes on art, machine aesthetics, and digital culture. He is director of Leuphana Arts Program at the university in Lüneburg, and has played key roles at transmediale – festival for art and digital culture, ISEA2010 RUHR, TESLA-Laboratory for Arts and Media, Berlin, and V2_Organisation Rotterdam, Institute for the Unstable Media. Lawrence Bird interviewed him on our current experience of media and civil society. Image: A. Broeckmann, transmediale 2007 (© Jonathan Gröger)

Lawrence Bird: It’s often said that we inhabit the city differently today because of our engagement with media and media technologies. This has been one of your main concerns, and it makes for a very interesting intersection of media theory and public realm theory. Where does this preoccupation come from on your part?

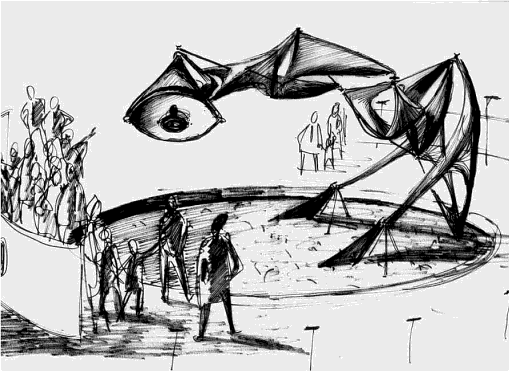

Andreas Broeckmann: I have arrived at these questions not so much from a theoretical or academic perspective, but in response to specific artistic practices that I was interested in. For my own thinking about this area, the works that the artist group Knowbotic Research were working on in the 1990s were seminal. The participative public installation “Anonymous Muttering” (1996), for instance, initiated a radical clash of the physical urban space with the virtual ‘space’ of the internet, interlacing the activities of the participants in a way that created a strange intermediate zone – maybe we could say that it allowed people to place themselves _in_ the medium. In the series of projects that followed under the title “IO-dencies” (1997-99), Knowbotic Research further explored the possibilities of becoming active, of acting in a virtual environment in a manner that was connected to activities and events in the physical space.

I was working quite closely with the group at the time, presenting some of the projects in Rotterdam where I was a curator at the V2_Organisation, co-authoring texts, organising workshops, etc.. This was a great opportunity to think through the issues of the new, hybrid public sphere that was opening up because of the Internet. In order to understand the works, it was necessary to develop a differentiated conception of what it meant to “be public” or to “become public”. The topic returned, for instance in projects I was involved in by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer in Rotterdam, or a publication on Polish video art by the WRO agency, or a major curatorial on a media facade in Berlin, or, for that matter, more recent projects by Knowbotic Research, like “Be Prepared Tiger”, or “MacGhillie”. Personally, I believe that privacy in all its guises – from camouflage and the absence of surveillance to “a room of one’s own” – is one of the great privileges of a modern individual. Contemporary media and communication technologies have transformed the possibilities of being private dramatically, just as the notion of what it means to be public is subject to drastic changes. And artists are articulating these changes which we are all part of, giving us opportunities to reflect on what is going on, and to imagine how things might also develop otherwise. I think that my interest in the relationship between publicness and intimacy is fed both by a personal sense of urgency and and concern, and by the inspiration I get from artists, not to fall into despair.

Lawrence Bird: Fascinating. So would you say that in the direction media are now evolving, there’s actually an increased scope for private “being” — not just in terms of a potential for increased anonymity and independence, but in terms of a richer and more developed individuality? To a greater degree — or perhaps qualitatively different — than was possible in earlier stages of modernity?

Andreas Broeckmann: Unfortunately not… I say that privacy is a privilege exactly because it is becoming such a rare condition these days. The developments that we speak about are, of course, not unidirectional and homogeneous, but very diffused and heterogeneous, and open to quite different interpretations. For many people, a platform like Facebook or Google-Plus is a way of discovering a new form of sociality in which they try out different ways of being public and being private.As for myself, having been brought up with the Critical Theory analyses of the Frankfurt School, I find it difficult not to see these optimistic readings as dangerously naive – it would be a bit like exploring your inner self in the highly regulated and commercial spaces of a shopping mall… I would not go so far as to say that privacy has completely disappered — as though we were now living in a global village of Big Brother containers, or in a vastly extensive version of the Truman Show. But I do think that today we lack a more widespread critical sense of resistance to the regimes of commodification that have taken the place of what were once “privacy” and “social relations”.

Lawrence Bird: You spoke about the concern of “falling into despair”. How general would you say that motivation is? I don’t know if you’ve thought about it this way, but I’m thinking in terms of Occupy, and the other social movements, many of them enabled by media and engaged by artists, which seem to generate new, and some evidence suggests quite lasting, relationships of trust and hope. Many of these seem to come in response to a recent loss of faith in corporations, governments, financial institutions — older social groups that had an important role in old definitions of “public”. I wonder if your comment connects with a widespread yearning for hope, in response to conditions that might well produce despair?

Andreas Broeckmann: I dare not speculate about the longevity of the relationships that have been built by the different branches of the Occupy movement, but I am skeptical about the longevity of anything that is built on specific internet-based media platforms. Facebook, for instance, was launched in 2004, that’s eight years ago, and the German and many other non-English Facebook services are no older than four years. That’s a very short time, and we might want to remember that platforms like Google (*1998), Facebook, Flickr (*2004) or Twitter (*2006) are not part of the natural environment, but recent services offered by profit-oriented companies which, just as well as they may rule the internet world throughout the 21st century, might also get drowned in the swamps of global capitalism (whose regime includes “customer confidence”).

I would refute the assumption, implicit in your question, that many of the people who protested on the squares in Madrid, Cairo, Washington or Athens last year were people who previously had faith in their governments, or the institutions of capitalism. Of course they didn’t, and quite rightly so. What was special about last year was that there is a new, articulate generation of people who would not put up with the situation of stasis, hopelessness and frustration that has paralysed major parts of global societies since 2003 when, in February of that year, millions who took to the streets around the world in protest, were not able to stop the US government and their allies from starting the war on Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. The inflection of this event is different in different parts of the world, but I believe that we share that moment. And this is where the protests in the Arab countries, and those in Spain and Greece, hit the squares on a parallel trajectory: In the same year of 2003, the German government started the implementation of what was called the “Agenda 2010”, a project based on the EU’s 2000 Lisbon agreement of economic restructuring, with the aim of making Europe more competitive on the global market. Since then, in Germany we have seen an erosion of the welfare state, drops in income for lower and middle classes and a huge increase in precarious jobs. But some economists also say that the reason for Germany’s relatively healthy economic situation today, compared with, for instance, Greece or Spain, is that these countries failed to reform their debt-pampered economies. Which is why there is a certain reluctance today in Germany to protect privileges for the Greek middle class, privileges which German citizens already had to give up years ago.

above: Tahrir Square on February 11, by Jonathan Rashad (CC-BY-2.0, 2011).

My point is that if we take things into a more extended historical perspective, and if we count our lives not in short Twitter months, we can see how the struggles, the hopes and the despairs of today are part of a broader set of transformations. And we can see that in these transformations there are forces at work which have a huge inertia and which need to be worked on and battled with both patience and long-term strategies. Like any other revolution, and like in the theatres of the Occupy movement, the one in Egypt may have started on Tahrir Square and the mobilisation of people through media-based social networks, but to complete that revolution, a difficult and drawn-out political struggle needs to be fought. Maybe that is the necessary realisation that hit “the movement” this past winter.

Lawrence Bird: And what form might those long-term strategies take? It’s a huge question perhaps, but do you have any ideas about the shape this restructured public sphere might have to take, what forms of governance and participatory democracy for example, to sustain a more permanent change?

Andreas Broeckmann: Personally, I believe that for the foreseeable future many political struggles will continue to happen in the ‘arenas’ of political institutions like governments, parliaments and other election-based structures, in political parties, public administrations, in transnational and inter-governmental decision-making bodies, in trade unions and NGOs. It is a realm that will only partly be affected or influenced by the online world, and even if the emerging public sphere of the Internet and its social media forums implies a huge expansion and diversification of the mass media dominated public sphere of the 20th century, this expanded public sphere will not necessarily have a bigger impact on political processes than the ‘old’ public sphere did. The experience of the ‘movement’ in Egypt today might be analoguous to that of the APO (the extra-parliamentarian opposition of the students movement) in 1960s and 70s West Germany, i.e. realising the necessity of getting involved in existing state institutions (“the long march through the institutions”), which brought members of that generation to power some 25 years later in universities, in parliaments, in national governments. The relevance and standing of the new Egyptian parties is not proven or disproven in the first elections; it is decided when in ten or twenty years from now they may or may not have been able to change the social consensus about democracy, rights, and freedom.

Lawrence Bird: A confession here: I’m an architect, so I always assume, perhaps naively, that a built infrasructure can play a role in these kinds of transformations. In your opinion, might a material intervention be a necessary part of those changes — distinct from, though perhaps in dialogue with, the mediated public realm? What kind of physical (urban) spaces might serve as a counterpoint or moderator to the transience of the Twitter world — and are those spaces any different from the urban spaces we have now?

Andreas Broeckmann: I doubt whether architecture in the narrower understanding of the term will play much more than a symbolical role in these struggles and transformations. Of course, the built environment, especially the way in which public space is configured, plays a significant role in how public life can unfold in cities. And there are political issues to be fought over: for instance, I find it curious how in many of the European cities the authorities allow the construction of one shopping mall after the other, pushing the social and commercial activity of shopping into privatised and highly regulated control spaces, and then those same authorities are surprised when the neighbourhoods in the vicinity of these malls deteriorate because the normal shops are abandoned or have to be closed, making room for trash and money laundering businesses. The resistance against such developments can at times most effectively be fought in local parliaments that, at least in Germany, have to give their consent to such major construction projects. This makes it necessary to join a political party, get elected into the local parliament, sit around in meetings, deal with all sorts of issues of public interest, etc., and be there when the application for the next shopping mall is up for decision…

Of similar relevance is the designing of the digital sphere through software ‘architectures’ – both in terms of individual applications and services, and in terms of the overall technical infrastructure, both hard- and software, and its governance. The critical discussions around the status of ICANN and, more recently, the public protests against law-making initiatives like SOPA and ACTA, have shown that protests can in fact have an impact on such structures. Yet, that impact will remain cosmetic if the public outcry is not followed up by sustained political work through which the drafting of and the decision-making on such laws is factually influenced. This is what lobby groups do, and this is what social movements also have to do, finding whatever possible and suitable political instrument or institution through which to act.

The major arena of constructing and designing the new political sphere will be in law-making, and I believe that the movement needs critical lawyers, historians of economy and charismatic intellectuals more urgently than architects – although, of course, everybody has an important role to play and no-one who wants to contribute should be sent away.

Lawrence Bird: And how about artists — do they have a role in this? To provoke, perhaps? To articulate social and political conditions? Would you say that whatever that role is, it can be part of the sustained transformation you’re talking about — or do they need to step down into a governance role to take part in that (Vaclav Havel being one example).

Andreas Broeckmann: In my understanding of art, there is no particular role that it can, or even “should” play. I would argue that the most important aspect of art for society is its autonomy and the fact that it has no particular responsibility. Art can beautify, it can decorate, it can irritate, it can disturb, it can question, it can affirm, it can simplify or complicate. Such an “open program” of course implies that individual artists or groups, or specific projects, will take a particular political stand, will try to influence a social or political situation — will seek real impact. This is a form of activism that art can borrow from political groups and movements, but it is not the activism that is crucial for the artistic practice, it is the transgressive articulation that artists may achieve in their own dealing with social realities. I want to emphasize that this is my understanding of art, and I fully respect people who think that art can and must be more engaged in social processes in order to be relevant. But again, I think that what art can give us most importantly is what happens in a zone of freedom that is morally, aesthetically and sometimes also politically more risky than anybody who acts in the political arena — save for the mavericks — would want to be.

So the question, “what should artists do,” can in my understanding only ever be answered: “they should do whatever they do.” It must be the best thing that they can do, they have to be precise in their formulations and realisations, they have to be committed, diligent, and daring. It is wonderful if they can, in that way, help proliferate good ideas and push the political situation in a good direction. But by the same token I believe that it is equally wonderful if artists ask questions that are impossible to answer, or pointing out unsolvable ethical dilemmas, or remove the mask of an opponent only to don it themselves.

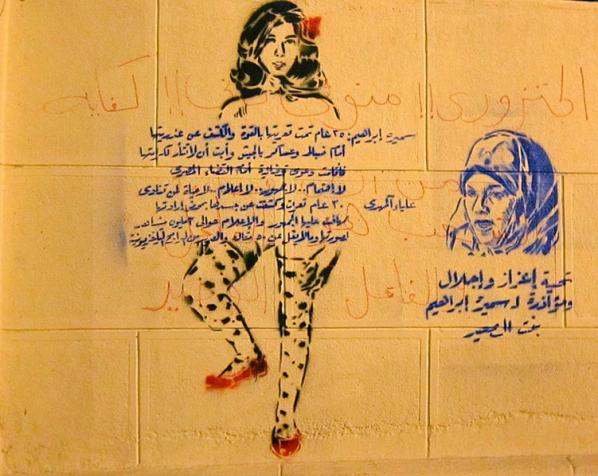

There is, in my eyes, certainly no obligation to go into politics like Havel did. Artists are not always people with a high moral reputation, and stepping into the political arena like Havel did requires stamina and a certain habitus. And there are many ways in which people can intervene in social and political processes. Take the example of Aliaa Magda Elmahdy who posted a photograph of herself naked on her website and sparked a huge debate about the situation of women in the Islamic world. This was not an art project, but it shows what work in the realm of symbols can achieve.

Lawrence Bird: If I could I’d like to steer the conversation in the direction of your thinking on “the wild” — perhaps it relates through the transgressive nature of art you’ve just been discussing, and the tricky relationship of that to civic functions, governance, and related realms of responsibility. Cities have been conceived as set apart from the wilderness — within the city lay the realm of humanity, civility, politics; outside its walls, the wild, monsters, raw life. Girorgio Agamben makes the case that the violence of our times equates to the obliteration of that line: between political life (zoe) and bare life (bios).

In light of what you’ve already said about art and transgression, and the value of that; and the precarious status of privacy today, and the danger of that; your understanding of media and the political movements underway today which involve some significant transgression of the boundaries of authority, I’m willing to bet you have a more nuanced take on this issue. What’s our condition now with regards to the edge of the wild? Is it a constantly shifting boundary, what Agamben refers to as the caesura? Does it imply a human condition interdigitated with an inhuman condition, like a werewolf, or cyborg? Does our humanity in fact find its source in the wild?

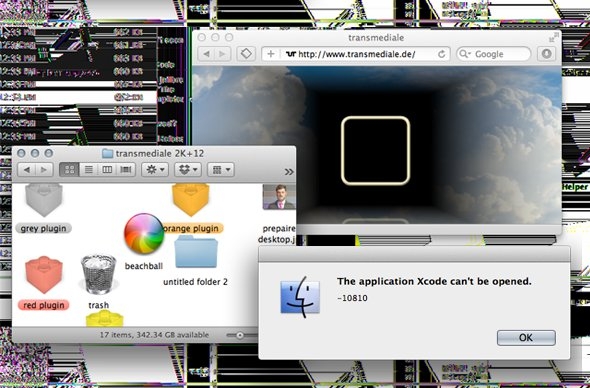

Andreas Broeckmann: The questions that you raise are of course extremely complex and very difficult to do justice in the current context. So allow me to shirk the anthropological discussion, which I guess I don’t have a particularly original opinion on anyway. When I spoke about the “wild” as an aspect of digital art a few years ago, it was in a half ironic, and half romantic way: ironic in the sense that art that makes use of digital media is technically conditioned and requires a “tamed” environment to function at all; even what is referred to as ‘glitch aesthetics’ is predicated on general functionality, the glitch being only a minor aberration, not a substantial fault. Yet, as you would gather from what I said before, I am also ‘romantically’ attached to the idea of an artistic practice that transgresses these technical functionalities and explores failure, dysfunctionality, misuse, or uncontrollability as categories of aesthetic experience. I’m thinking of artists like Gustav Metzger, Jean Tinguely, Herwig Weiser, or JODI, who in their works perform, we might claim, the potential wildness of technology. This is mostly a controlled, at times even metaphorical wildness, whereas the true wilderness of technology, if we want to go there, is probably the realm of the accident that Paul Virilio has so poignantly written about. An “art of the accident”, as we entitled a festival in Rotterdam in the late 1990s, is, I believe, only possible in the realm of metaphors.

What I’m currently wondering about is whether in our 21st-century cybernated world a notion of “nature” as something different from culture maybe disappears completely, as we have full Google-ised view and total measurability of what happens on Earth, from millimetre shifts of tectonic plates to carbon dioxide output of cattle. In such a world, there would be no room any more for the “wild”, only for different degrees of pollution on the one hand, and endangerment of species on the other…

In the long run I have trust in the finality of all existence, and the futility of all human efforts. But in the short term, that is, in our lives, I believe that we have to work to make the world a little better, or at least do our best to not make things worse than they are.

Opening Event: Saturday 13 October 2012, 1-4pm

co-hosted with The Festival of Mint – A Celebration of Local Growing – serving mint tea and mojito

Contact: info@furtherfield.org

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE FOR PRINT HERE

+ See images of the exhibition on Flickr.

To be alive is to be wild. And we humans have a will that shapes the world with language, song, lust, labour and play. And for those of us who connect with it, a network of machines now extends our reach, amplifies our urges and quickens our exchanges.

The artists in this exhibition work and play with living organisms and technical things, systems and language, to explore how our relation to the natural world is changing. They introduce us to the unruly life going on in other natural webs of communication, knowledge and feral exchange. Gallery visitors (humans and dogs) are invited to view videos, interact with art installations and social media and undertake walks in the surrounding park with its other animals and edible plants.

Mary Flanagan travels overland and undersea in virtual worlds. Her journeys in the worlds are caught on video. Her avatar scouts the boundary lines of ‘heritage’ landscapes built by “residents”. Her walks are inspired by Thoreau, the great American writer and walker, who knew that ‘all good things are wild and free’.

![Aquitaine from the [borders] series by Mary Flanagan](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/borders-acquitaine-web.jpg)

Andy Deck calls attention to echoes of the wild in language. Despite the many entertaining digital visions of nature beamed to the flat screen, a wealth of intuitions relating to nature still survive in colorful expressions passed down for centuries. He invites you to help him build a bestiary of animal idioms using social media and a gallery installation.*

Sarah Waterson has invented a set of cartographic tools for dogs (and their human friends) to develop an interspecies psychogeography. Her electronic mapping system generates sniff data, routes and photographic journals supporting communication, collaboration and knowledge-sharing between companion species.

Helen Varley Jamieson and Paula Crutchlow dramatise the private actions and global consequences of our domestic lives in a long-running series of networked performances located in peoples’ homes. Dave’s Quiz (part 2) is an interactive extension of their provocation to discuss and appreciate relationships between personal, state and corporate responsibility around issues of consumption and disposal in late-capitalism.

Artists duo Genetic Moo invite us to discover a dark, interactive sea of wiggling, luminescent creatures that gorge on torch light. They fantasize an evolutionary digression through the lens of human sensuality, drawing on images made by early scientists as they first found micro organisms or Animacules swarming in every sea, pond and pool of saliva.

Disquieted by the environmental impact of constant technological upgrades, Dominic Smith works with open knowledge from the DIY mycology movement to create a system that combines the waste products from the tools and fuels of the contemporary coder. Out-of-date software manuals and coffee grounds are shredded to create a compost for fruiting oyster mushrooms to be harvested and consumed by visitors.**

This exhibition is dedicated to Jay Griffiths, author of WILD: An Elemental Journey (2006).

* Crow_sourcing is a 2012 Commission of New Radio and Performing Arts, Inc. for its Turbulence website. It was made possible with funding from the Jerome Foundation. http://Turbulence.org/Works/crow_sourcing

** Dominic Smith developed this iteration of the shredder concept, originated by Julian Priest, David Merritt & Adam Hyde, as part of the geekosystem project. It is an experimental transposition of software development methods taking an organic, material form. It’s also worth noting that in his 1998 net art work Shredder 1.0 Mark Napier took the texts and images from pages of the WWW and jumbled them in colourful abstractions to reveal their ‘rawness’ once freed from the strict orthodoxies of web page design.

Crow_sourcing by Andy Deck

[borders] by Mary Flanagan

Animacules by Genetic Moo

make-shift: Dave’s quiz (part 2) by Helen Varley Jamieson & Paula Crutchlow

Shredder by Dominic Smith

Laika’s Dérive – The dogs de Tour by Sarah Waterson

Paula Crutchlow

Paula Crutchlow is a performance maker and director who co-authors live events across a variety of forms. As a co-founder and director of Blind Ditch she combines digital media and performance to engage audience and participants in distinct and active ways. Her work often uses a mix of score/script, improvisation and structured interaction to focus on boundaries between the public-private, and issues surrounding the construction of identity and the politics of place. Paula is currently the Creative Advisor for Adverse Camber directing work with some of the UK’s leading storytellers, she was an Associate Lecturer in Theatre at Dartington College of Arts, Devon 2001-10, and teaches Digital Performance Practice at the University of Plymouth.

Andy Deck

Andy Deck specializes in collaborative processes and electronic media. As a Net artist and software culture jammer, Deck combines code, text, and image, demonstrating patterns of participation and control that distinguish online presence and representation from previous artistic practices. In addition to numerous online exhibitions, his work has appeared in exhibitions like net_condition (ZKM), Unleashed Devices (Watermans Art Centre), and Animations (PS1-MoMA). He is also a co-founder of Transnational Temps, a media arts collective concerned with making Earth Art for the 21st Century.TM After showing in EcoMedia, a ground-breaking series of european exhibitions, Transnational Temps mounted the 2010 oil-related exhibition Spill>>Forward in New York. In 2011 Deck received first prize in the interactive division of the LÚMEN_EX Digital Art Awards. Deck’s work, currently shown by the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Artport and the Tate Online, has been commissioned by these and other prestigious institutions. Deck lives and works in New York City.

Mary Flanagan

Mary Flanagan is an artist focused on how people create and use technology. Her collection of over 20 major works range from game-inspired systems to computer viruses, embodied interfaces to interactive texts; these works are exhibited internationally at venues including the Laboral Art Center, The Whitney Museum of American Art, SIGGRAPH, Beall Center, The Banff Centre, The Moving Image Center, Steirischer Herbst, Ars Electronica, Artist’s Space, The Guggenheim Museum New York, Incheon Digital Arts Festival South Korea, Writing Machine Collective Hong Kong, Maryland Institute College of Art, and venues in Brazil, France, UK, Canada, Taiwan, New Zealand, and Australia. Her three books in English include Critical Play (2009) with MIT Press. Flanagan founded the Tiltfactor game research laboratory in 2003, where researchers create game interventions for social change.

Genetic Moo

Genetic Moo build living installations in pixels and light. The duo have been creating interactive art since 2008. Virtual creatures are constructed from choreographed video clips, combining elements of the human and the animal. They respond in a variety of life-like ways to audience motion, sound and touch and vary in size from the tiny Animacules to the all encompassing Mother. The works are driven using Open Source and Flash Software utilizing a variety of interactive interfaces. The programming behind the work is just complex enough to make the creatures appear more believable and create rich user driven narratives.

Schauerman and Pickup both gained Masters degrees from the Lansdown Centre of Electronic Arts. Their work has been exhibited extensively including the De La Warr Pavilion (2010); Watermans (2010) The Wellcome Collection (2011) and Glastonbury (2011). One of their works, Starfish, received a John Lansdown Award for Interactive Digital Art at Eurographics (2007) and was nominated for an Erotic Award (2012).

Helen Varley Jamieson

Helen Varley Jamieson is a writer, theatre practitioner and digital artist from New Zealand. In 2008 she completed a Master of Arts (research) at Queensland University of Technology (Australia) investigating her practice of cyberformance – live performance on the internet – which she has been developing for over a decade. She is a founding member of the globally-dispersed cyberformance troupe Avatar Body Collision, and the project manager of UpStage, an open source web-based platform for cyberformance. Using UpStage, she has co-curated online festivals involving artists and audiences around the world. Helen is also the “web queen” of the Magdalena Project, an international network of women in contemporary theatre.

Dominic Smith

Dominic Smith is an artist who engages with project hierarchy, ownership of ideas and heuristic curatorial strategies. Dominic is a founding member of ptechnic.org. He has exhibited and performed at Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Zealand, at the ICA in London, CCA Glasgow, AV Festival, Newcastle and Eyebeam NY. He has a doctorate with CRUMB at Sunderland University that examines the relationship between open source production methods, and art/curating methods. Dominic is also the current curator of thepixelpalace.org through which he also developed and runs basic.fm

Sarah Waterson

Sarah Waterson has practised as a new media artist for the past twenty years. Her works include electronic installations, collaborations with performers, video and audio work, generative and software based artworks, VR environments and data visualisations and ecologies. Interdisciplinary and collaborative practice informs the development and ultimately the design of these artworks. Her current interests include data mapping, data ecologies and cross species collaboration.

Sarah’s recent interactive installations have included: Laika’s Dérive (Performance Space, Carriageworks 2011), 33ºSouth (collaboration with Juan Francisco Salazar, Casula Powerhouse 2009), a custom made data mapping system that juxtaposes the cities of Sydney (Australia) and Santiago (Chile) trope, a e-literature project developed for the Second Life environment (SWF 08, ongoing), subscapePROOF (collaboration with Kate Richards, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne), and subscapeBALTIC (ISEA2004, Helsinki, Finland). Sarah is a senior lecturer in interactive media at the School of Humanities and Communication Arts, University of Western Sydney, Australia.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England

Part of Furtherfield Open Spots programme.

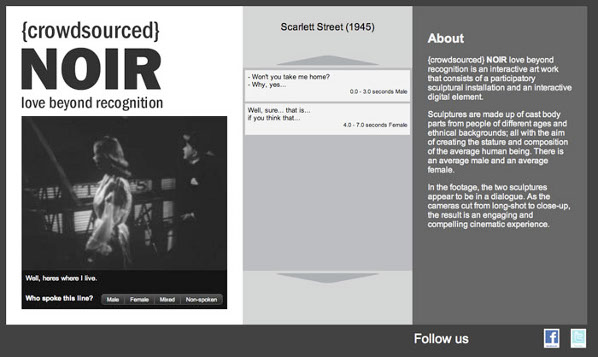

Please join us for a drop-in ‘clipsourcing’ workshop led by Swedish artist Josefina Posch in collaboration with artist and new media developer Mike Blackman (UK).

Using online tools specifically created for the project, participants will identify who the speakers are, contribute keywords, and rate short movie clips from the online public domain Film Noir Archive. The contribution will help shape the final interactive piece that will be streamed live at Futherfield Gallery in December 2012.

See images of the workshop on Flickr.

{crowdsourced} Noir / Love Beyond Recognition is a process-based artwork encompassing a sculptural installation and an interactive stream across the World Wide Web. The origin of both parts of the project is based upon the notion of ‘crowdsourcing’. The principle being that more heads are better than one. By canvassing a large crowd of people for ideas, skills, or participation, the quality of content and idea generation will be superior. In this instance, crowdsourcing will be applied through the use of clipsourcing tools which have been developed to aid in project-related tasks that can only be achieved through human interaction/intervention. This way, the crowd will help the artist achieve these tasks whilst adding a democratic element to the final outcome of the project.

During Spring and Summer 2012, an interested public will be able to both participate and contribute to the project’s creative process in two distinct ways: in Sweden as models, whereby a cast will be taken of a chosen body part (the body parts will later be assembled to full figure sculptures) and in the UK by taking part in a workshop at Furtherfield Gallery to help source short clips from the Online Public Domain Film Noir Archive through our online tool. The final iteration of the project will be exhibited in Gothenburg, Sweden in December 2012 with live interactive streams at Furtherfield Gallery, London.

Josefina Posch

Josefina Posch is a Swedish artist that has worked and exhibited extensively abroad, including at the 52nd Venice Biennale, Fondazione Pistoletto’s Cittadellarte, Sculpturespace NY and a residency at Duolun Museum of Modern Art Shanghai. During her 3 month residency at Art Space, Portsmouth, in Autumn 2010, she began her collaboration with artist and new media developer Mike Blackman in the development of her digital concepts.

The project is supported by Arts Council England/British Council and the Gothenburg City Arts Council.

Featured image: Still from Me and Mrs Sloan (Susan Sloan (2007). Motion-captured animation of artist’s mother.

Susan Sloan’s exhibition of motion captured portraits on The Wall at The Photographers Gallery raises issues in terms of data object relations and computer animation – or ‘animatography’.

In critiquing the work by Susan Sloan, currently on show on The Wall, what emerges is the artist’s concern with the essential qualities of the data space that she is utilising. What has become apparent is the distinct new medium of animatography, as used in virtual reality art works like Sloan’s, as well as in the more ubiquitous moving image; a language which is not composed uniquely by the author/animator, but also by the apparatuses of computing and software development which are then engaged with by artists and other individuals, “they [photographs] are produced, reproduced, and distributed by apparatuses, and technicians design these apparatuses. Technicians are people who apply scientific statements to the environment.” [1] In this way, a piece of proprietary software like SoftImage, can be seen as an apparatus much like a camera or an easel.

In answer to the Photographers Gallery’s questioning of the impact the digital is having, I would argue that the critical and theoretical discussion of computer animation use in virtual art works should focus on the creative exploration of data object relations. I am also suggesting that the term animatography be applied when talking about the medium of computer animation, and the following discussion focuses on the development of an awareness of how this language is utilised in art in virtual space.

The medium of animatography can be explored as an essentially synthetic medium which extends the languages of animation into one of data object descriptions; the use of data to describe virtual objects, and the complexity of these descriptions. Sloan’s work very much explores the nature of applying data to ‘objects’ or rather, as it means in psychoanalytic terms, subjects. The work is composed of complex object descriptions, comprising 3-D modelling techniques as well as motion capture data.

First it is necessary to look at data object relations in terms of psychoanalytic theory, then its applicability to animatography. Susan Sloan’s work, highly explorative of this as it is, is looked at to further elucidate the relationship between data, psychoanalytic theory and animatography.

To understand this approach it is first necessary to outline a theory of object relations as explored by Peter Fuller in relation to art works. Fuller applied D.W.Winnicott’s major psychoanalytic concept of the ‘potential space’ [2] and found that he could relate this theory to his study of aesthetics, and it has informed the development of a theory of animatography, which is based on our relationship with ‘data objects’, in aesthetic and cultural terms.

Winnicottís theory describes a baby’s gradual development and awareness of herself as a ‘separate autonomous human being’ [3] in relation to, at first, her mother. While up until that point she has felt at one with her mother, several months after birth, at a key moment, this recognition of autonomy starts to occur. Fuller writes, “This process of discovery seems to be a vital period of human growth. During it, the baby, necessarily posits the idea of a ëpotential space.” [4] He quotes Winnicott’s definition of potential space as: “the hypothetical area that exists (but cannot exist) between the baby and the object (mother or part of mother) during the phase of the repudiation of the object as not me, that is at the end of being merged in with the object.” [5]Fuller then points out that “Much in Winnicott’s view, depended on this ‘potential space’ between the subjective object and the object objectively perceived, between me-extensions and the not-me.” [6]

Potential space, Fuller explains, is important to creativity and to understanding aesthetic experience. The ‘location of cultural experience’ is derived from the ‘potential space’ where ” – if he has sufficient trust in his environment – the individual can explore the interplay between himself and the world, not as mere fantasy, but as cultural products which can be seen and enjoyed by others.” [7]

Similarly the cultural products of computer animation and therefore the aesthetics of animatography can be seen to derive from a relationship to the potential space, as transitional objects of meaning and value generated through a type of work and/or play. For Winnicott, “play is the paradigm of cultural activity” [8] and “cultural activities are those in which the experiences of the potential space are still operative.” [9] If we take Winnicott’s and Fuller’s theories, the potential space exists for artists, animators and a participating audience in which a play of separation; where a perception of what is me and what is ‘not-me’, takes place. There is no essential difference here between traditional media and animatography, apart from the specific differences of the nature of data itself, and therefore how we relate to data object descriptions.

If we add to this theory of ‘potential space’ with feminist psychoanalytic theory, which, in contrast to a generally masculine approach sees positivity in closer connectedness: “Chodorow herself suggests that care and socialisation of girls by women produces attributes which could (and should) be regarded positively; a personality founded on relations and connection, with flexible rather than rigid boundaries, and with a comparatively secure sense of the non-hierarchical nature of gender difference.” [10] We can see Sloan’s work as a carefully constructed interplay between artist and subject. Also, what does it mean to be described by data, which has automation at its heart, and yet requires a lot of skill to achieve this level of detail?

In virtual environments, the avatar is a key aspect for enabling a realisation of the ‘world’ to take place through human-computer interaction. In the works currently on show, Sloan looks intensely at the animated portrait, which inevitably relates to the condition of the avatar, while raising questions of perception to do with notions of reality and authenticity. Portrayed through animatography, the data object of the portrait model is related to as a me-extension, as well as sometimes being felt to be not-me, but a representative of the self, in terms of the freedom of self portrayal in this genre. In this sense, Sloan’s work suggests avatars ‘which really look like you’, through which the complex psychological reaction of what is me and not-me can be apprehended.

As such animatography could be said to have a physicality, in terms of the data it is composed of. Projecting the imagination into a notional space, the artist can at the same time make that space pragmatic in symbolic terms. A fantasy, and yet a data driven reality. This paradox between perceiving the physicality of data and the perception of the animatographic illusion as simply a fantasy lies at the heart of this relationship.

Susan Sloan’s Me and Mrs Sloan (2007), explores data object relations in the form of a motion captured portrait of her mother synthesized with motion captured movement by herself. It is a work about the potential space itself. In this instance, the artist has modelled the head and upper torso of her mother, in 3-D animation software, and then animated the head and shoulders, based on subtle motion captured material of herself. In this way, the data object is her mother combined with herself in terms of the motion captured material. It is Sloan’s work, and therefore the dialogue with what is ‘not-me’ is a fascinating one. The motion captured material is also ‘not-my-mother’, and instead it is a record of Sloan’s slight movements. In terms of locating ‘cultural experience’ (Fuller, 1980) this is a study of whether and how the potential space exists, when working with animatography. What is isolated or exposed, is that we relate to the ‘data object’ in the form of Sloan’s mother, as if the essence of potentiality in the relationship is somehow captured, in a way that explores what it means to relate to data that is ‘all-there-is’. This helps to establish that there is a cultural experience in the work, by the subject of the work itself.

The work explores synthesis in data terms, the portrait model with the motion captured movement used to animate it. In this sense identity is blurred artificially, and a synthetic effect is created, yielding a potential space in animatographic terms. In this work a synthetic identity, in this case between mother and daughter, becomes possible, which is like an advanced form of the avatar in multi-user platforms.

The concept of ‘potential space’ can be used to understand the nature and significance of data object relations in animatography, the me-extensions and the not-me, through programming a computer or manipulating a computer program to make animation is what this work points to in technical terms.

Animation is principally iconic, which means that there is more me-ness in its structure and execution than the traditional film image, which is partly composed of the indexical. [11]It can be argued that the engagement animatographers have with the portrayal of data object relations is precisely what identifies the need for animatography as a separate discipline, one which can culturally embody the unavoidable relationship we now all have with data objects in a more ubiquitous sense.

Data object relations in terms of Sloan’s work, has been considered in relation to psychoanalytic theory and its applicability to animatography. Through analysing a preoccupation with object relations, and specifically ‘the potential space’ as found in Winnicott’s theory, evidence of the potential space is found to exist as subject matter within Susan Sloan’s work. This is potentially an important aspect in critiquing art which explores subtle synthesis as an aspect of data object relations.

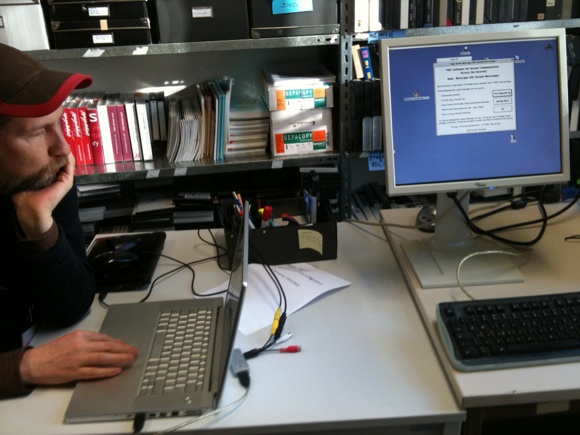

Dr Stephen Bell and Susan Sloan at the NCCA (National Centre for Computer Animation) in Bournemouth, United Kingdom

An interview with Katrina Sluis, Digital Curator at the Photographers’ Gallery By Marc Garrett

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/interview-katrina-sluis-digital-curator-photographers-gallery

Featured image: “Born in 1987: The Animated GIF” from the site’s page.

Marc Garrett interviews Katrina Sluis, the new curator of the Digital Programme at The Photographers’ Gallery, London. We discuss about the gallery’s recent show Born in 1987: The Animated GIF and what kind of digital exhibitions and projects we can expect from the gallery in the Future.

An edited selection shown on the London Photographers’ Gallery’s new digital wall, during the final weeks of the show. http://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/the-wall-2

The exhibition microsite. An open conversation where anyone can join in and contribute their own GIFs. http://joyofgif.tumblr.com/

Marc garrett: You have joined The Photographers’ Gallery and as part of the new digital programme launched the exhibition “Born in 1987: The Animated GIF”. Could you tell us about this project?

Katrina Sluis: The digital programme presents projects both online and offline, which respond to recent dramatic shifts in the digital image as it becomes increasingly screen-based and networked. As part of this new programme we have launched ‘The Wall’ – a permanent exhibition space on the ground floor of the Gallery, visible both to visitors and passersby on Ramillies street. The Wall itself is a 2.7 x 3m Sharp video wall which we installed after considering a number of different technologies. We were conscious not to use digital projection as it would locate the project within traditions of cinema and video art, and we wanted the screens to respond to the reception and distribution of images within wider visual culture.

For the opening show, we decided to focus on the animated gif for a number of reasons. Firstly, the gif is a uniquely screen-based image format, in which the specific characteristics and limitations of the image file are inherent to the form, in contrast to the other kinds of images the gallery might show which might adopt digital techniques but result in traditional print-based photographic work destined for the gallery space.

I also wanted to disrupt certain expectations about the screens – the fetishisation of resolution and image quality, and what kinds of photographs The Wall’s programme might seek to address. The animated gif in this sense is very interesting – it is one of the first image file formats native to the web, and although it is 25 years old this year it has been undergoing a resurgence on platforms such as Tumblr. In a commissioned essay for the show, Daniel Rubinstein speculates that current resurgence of the gif “is not only part of the nostalgic turn towards the blurred, the unsharp and the faded but it is also a marker of a moment when the history of the network becomes the material from which the digital image draws its living energy.”[1] Frequently authorless and contextless, the gif image works on a different economy in which its value is based not on its uniqueness and scarcity (as in certain forms of art) but its circulation and proliferation. Although there have been significant practitioners of the gif form, it is a format which ultimately resists canonization. And, in the context of a photography gallery, it opens up other debates concerning medium specificity and the ‘post-photographic’.

In approaching the exhibition, I was keen to ask a diverse range of photographers, writers, organizations and other practitioners to contribute a gif for the show. In keeping with the unmonumental nature of the form, I asked contributors to respond within a short timeframe of 7 days. For many contributors, this was the first time they had made a gif; but other contributors already had large followings on Tumblr and some were established net artists. This opening show and associated Tumblr site (http://joyofgif.tumblr.com) became a starting proposition for the project in order to then open up The Wall to gif contributions from the wider public. We will continue to update The Wall with public responses on a daily basis until the final day of the show on 10th July.

MG: At first, some may assume that the first part of the exhibition title ‘Born in 1987’, refers to the fact that today so many young people using computers these days were born in 1987. Yet, the GIF format, short for ‘Graphics Interchange Format’, was introduced to the world of computers by CompuServe in 1987. Was the title of the show deliberately playing with both notions?

KS: I like this idea! The title does self consciously play with the way in which the digital is valorised for its endless ‘newness’ and novelty but yet has this long and frequently overlooked history of creative experimentation. You can also see this reflected in the recent hype around the work of Kevin Burg and Jamie Beck who have (problematically and entrepreneurially) re-branded the gif as the ‘cinemagraph’.

MG: Do you consider this project to be net art, if so, how does it relate to other forms of net art?

KS: The project (and The Wall’s programming) does pose certain problems as it seeks to relocate certain forms of online practice(s) into the space of the art museum. At the same time, the project exists in an online context with its own very different life on Tumbr, where the work circulates in a very different context with a very different audience. I think there are many interesting opportunities which emerge from this intersection of the institutional frame of the museum (with its associated issues of cultural and curatorial authority and the legacy of aesthetic modernism) and the values and politics which inform certain kinds of networked arts practices.

But I also think the project also needs to be understood in the specific context of The Photographers’ Gallery, its history and audience. Whilst the project shares the concerns of net art by raising questions concerning authenticity, authorship and ‘the social’, it is also motivated by the need to rethink familiar notions of photography and temporality, indexicality and the economy of the image – concerns which presently haunt the field of photography theory.

![Kennard Phillipps. GIF image by Peter Kennard and Cat Phillipps. Born in 1987: The Animated GIF. The Photographers' Gallery 2012 [2]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/fuck-the-markets-latest1.gif)

![Rad Racer glitch 3. GIF image by tracekaiser. Born in 1987: The Animated GIF. The Photographers' Gallery. 2012 [3]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/tumblr_m5tqfl62wl1qew2moo1_400.gif)

MG: In what way do you see this form of creativity relating to others who may not be so well versed with net art culture, or digital networked practices?

KS: The Wall presents an opportunity for the Gallery to collaborate with diverse communities who can bring their distinct expertise and experiences to the programme, and the net art community has much to offer in this respect. For this reason, we aim to develop The Wall’s future programme through the framework of ‘collaborative research’, in which our audience, along with the organizations we partner with, are potential co-researchers. The co-researcher model developed as an approach to research democracy in the Social Sciences, particularly in the approach of Action Research in the NHS but in a more relevant cultural example was used extensively in the Tate Encounters: Britishness and Visual Culture research project. Co-research recognises both the collaborative and collective nature of meaning construction, through a process which attempts to trace and reveal the complex manufacture of meaning.

At the same time, there is still another related project to be done in highlighting and responding to digital projects whose life is online – this is of course something I admire Furtherfield for doing so brilliantly. On a smaller scale and with a more narrow focus, we hope to launch a blog which will draw attention to online work which relate to photography as it becomes polluted, valorized, hybridized and networked.

![GIF image by Paul Flannery. Born in 1987: The Animated GIF. The Photographers' Gallery. 2012 [4]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/tumblr_m442xish4q1rvlji4o1_500b_0.gif)

MG: Some, may view this this exhibition as relating to Internet Folk Art. There is an interesting article by Kenneth Goldsmith[1] where he discusses the digital theorist Rick Prelinger’s claim “that archiving is the new folk art, something that is widely practiced and has unconsciously become integrated into a great many people’s lives, potentially transforming a necessity into a work of art.”

Now, this is not directly relating to the show itself, but it resonates something regarding the inclusiveness of the show. So, in respect of it ‘possibly’ possessing aspects of Folk Art, what connections do you see as relevant or not, and what does it mean to you?

KS: By focusing on the gif the show does problematise the distinction between artist and audience, in which participation, openness and the ‘crafting’ of the image becomes key. However I have reservations about the use of the term Internet folk art, which could be construed as imposing a certain modernist logic on the discussion, burdening it with an analogue modeling of high and low culture. The research approach has been adopted precisely to avoid the trap of binary nominalism, and to problematise the tendency to shoe horn internet practices into the language of cultural studies and aesthetics.

MG: The Photographers’ Gallery was the first independent gallery in Britain devoted to photography and has been going since the 70s. It is the UK’s primary venue for photography and has been dedicated in establishing photography as an essential medium, representing its practice in culture and society. It seems that The Photographers’ Gallery is going through another transition. You have already mentioned how hybridized and networked the nature of future projects will be. So what kind of exhibitions and projects can we expect in the future?

KS: Because digital technology is not in itself a new photographic medium, but essentially a hybrid and converged set of technological practices, it raises many interesting problems, both theoretical and practical for a Gallery focused on photography. To the computer, the photograph is indistinguishable from the other binary blobs of data we used to call books, films and songs. The crisis of digitization and medium specificity now extends to the domain of the camera – Digital SLRs are coveted for their ability to shoot high quality digital video, and we turn to our mobile phones when we want to take snapshots. This is a very rich context for the programme to explore, and ideally the future projects will respond to the technical, creative and cultural languages of photography as produced by computer engineers, web developers, photographers, artists, networked communities, social scientists and other practitioners.

Our next show on The Wall (opening 13th July) features the practice based research of Susan Sloan into portraiture using motion capture and 3D animation techniques widely used in entertainment, medicine and the military. Her motion studies refer to the traditions and conventions of portraiture and the changing role of the camera as a recording device. At the same time, her work raises questions concerning the convergence of painting, animation, film and photography in the digital realm.

The future digital programme which will occupy different spaces and address various photographic practices including augmented reality, social media, electronic publishing, interactive media, mobile computing and synthetic imaging.

The Joy of GIF – the London Photographers’ Gallery’s new digital wall. Article by Wendy McMurdo.

http://www.foam.org/foam-blog/2012/may/photographers-gallery

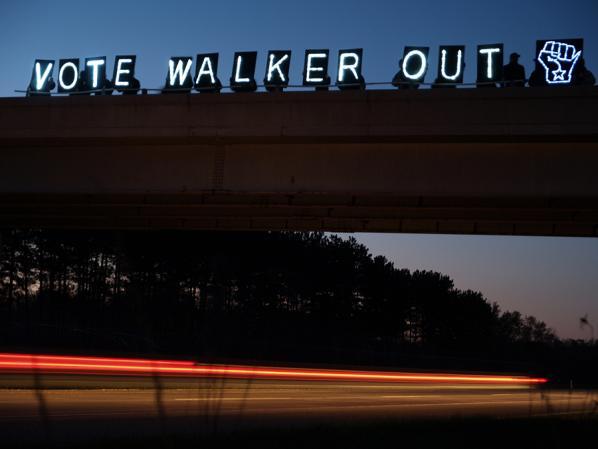

Featured image: corporations are not people – the Overpass Light Brigade

Overpass Light Brigade in Tosa from Overpass Light Brigade on Vimeo.

Wisconsin has arguably been ground zero for union busting, DIY social movements, corporate takeover of government, and divisive – and often misinformed – political debate in the US for more than a year. And the Overpass Light Brigade (OLB), initiated by Milwaukee artists Lane Hall and Lisa Moline, have been a guiding light – literally – in how ground-up messaging and change can happen. Now a collaboration between many people, the OLB relies on an ever-widening community of activists, artists, thinkers, and do-ers for their “Signs of Resistance.” After a few rounds of local rye whiskey at Milwaukee’s Riverwest Public House Cooperative – one of the only co-op bars in the country – I did an email back and forth with OLB co-founder Lane Hall to find out more about what makes them tick, how they see themselves, and where the movement they are a part of is headed.

Nathaniel Stern: What is OLB? It feels more “struggle-” rather than “goal-” orientated, despite that its first mainstream recognition is in relation to a specific campaign. Can you talk a bit about its history: how it started, where it headed, and what it might become?

Lane Hall / Overpass Light Brigade (OLB): On November 15 of last year a rally was organized by grassroots groups in Wisconsin in order to kick off the Recall Walker campaign. It was to begin right after work, at 5:00 pm. Both Lisa Moline (co-founder of OLB) and I had been very active in what we now think of as the Wisconsin Uprising, and we asked ourselves the simple question, “How do we achieve visibility for graphic messages when it is dark at 4:30?” We began to tinker with off-the-shelf Christmas lights, and found some battery-powered strings of LEDs. We built our first sign, a 3′ x4′ panel that spelled out RECALL WALKER. When we arrived at the rally, we were immediately asked to be behind the speakers. That sign got on the Rachel Maddow and Ed Schultz show that evening, so we knew we had hit on something that afforded powerful visibility. That first sign is now, incidentally, in the archive of the Wisconsin State Historical Society.

We then proposed a second design challenge to ourselves: how do we get messages out to masses of people, since we can’t command the airwaves like Walker’s Koch-fueled campaign? Once we decided to go out on highway overpasses, we “scaled-up” the letters so that we could spell out words, refrigerator magnet style, one letter per 2′ x 3′ placard.