Part of Furtherfield Open Spots programme.

Please join us for a drop-in ‘clipsourcing’ workshop led by Swedish artist Josefina Posch in collaboration with artist and new media developer Mike Blackman (UK).

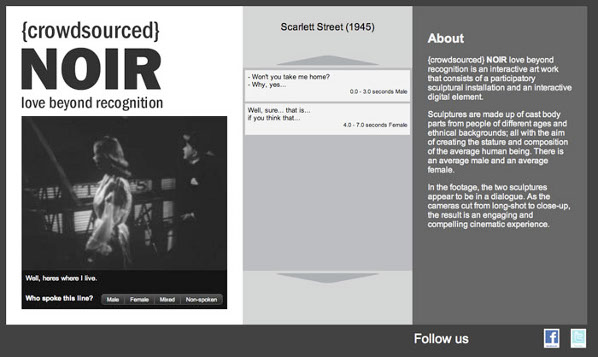

Using online tools specifically created for the project, participants will identify who the speakers are, contribute keywords, and rate short movie clips from the online public domain Film Noir Archive. The contribution will help shape the final interactive piece that will be streamed live at Futherfield Gallery in December 2012.

See images of the workshop on Flickr.

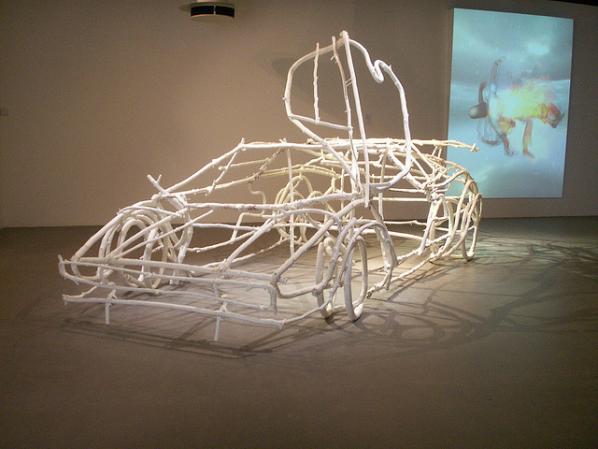

{crowdsourced} Noir / Love Beyond Recognition is a process-based artwork encompassing a sculptural installation and an interactive stream across the World Wide Web. The origin of both parts of the project is based upon the notion of ‘crowdsourcing’. The principle being that more heads are better than one. By canvassing a large crowd of people for ideas, skills, or participation, the quality of content and idea generation will be superior. In this instance, crowdsourcing will be applied through the use of clipsourcing tools which have been developed to aid in project-related tasks that can only be achieved through human interaction/intervention. This way, the crowd will help the artist achieve these tasks whilst adding a democratic element to the final outcome of the project.

During Spring and Summer 2012, an interested public will be able to both participate and contribute to the project’s creative process in two distinct ways: in Sweden as models, whereby a cast will be taken of a chosen body part (the body parts will later be assembled to full figure sculptures) and in the UK by taking part in a workshop at Furtherfield Gallery to help source short clips from the Online Public Domain Film Noir Archive through our online tool. The final iteration of the project will be exhibited in Gothenburg, Sweden in December 2012 with live interactive streams at Furtherfield Gallery, London.

Josefina Posch

Josefina Posch is a Swedish artist that has worked and exhibited extensively abroad, including at the 52nd Venice Biennale, Fondazione Pistoletto’s Cittadellarte, Sculpturespace NY and a residency at Duolun Museum of Modern Art Shanghai. During her 3 month residency at Art Space, Portsmouth, in Autumn 2010, she began her collaboration with artist and new media developer Mike Blackman in the development of her digital concepts.

The project is supported by Arts Council England/British Council and the Gothenburg City Arts Council.

We are collecting childhood rhymes from around the world spoken by many generations of local residents of the borough for a sound installation as part of the Cultural Olympiad Festival.

Please come to Furtherfield Gallery in Finsbury Park on Saturday 21 July, 11-3pm to take part!

See images of the launch on Flickr.

Artist and composer Michael Szpakowski has worked with local children and their families to create a generative sound sculpture that invokes the collective memory of childhood, drawing on the memories of Haringey residents from all over the world.

A collective memory of childhood will be launched on Saturday 28 July 2012, 2-5pm.

To add your voice to this sound installation come to the gallery on Saturday 21 July between 11am and 3pm. You will meet the artist Michael Szpakowski who will be recording with you and other local residents any childhood rhymes, skipping songs or lullabies.

+ For more information please contact Ale Scapin

Michael Szpakowski is an artist, composer and film-maker who devises and facilitates many of our Outreach projects with young people. Participants create films, games and performances that explore the tools and processes of co-co-creation in a digitally connected world. The work engages young people, meeting them where they are in a constructive, imaginative and inclusive way. With DVcam in hand he finds poetry in the everyday, music in a London pavement and if called upon could find a way to inspire the imaginations of curbstones with his enthusiasm, experience and skill-sharing abilities.

www.somedancersandmusicians.com

Featured image: “Born in 1987: The Animated GIF” from the site’s page.

Marc Garrett interviews Katrina Sluis, the new curator of the Digital Programme at The Photographers’ Gallery, London. We discuss about the gallery’s recent show Born in 1987: The Animated GIF and what kind of digital exhibitions and projects we can expect from the gallery in the Future.

An edited selection shown on the London Photographers’ Gallery’s new digital wall, during the final weeks of the show. http://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/the-wall-2

The exhibition microsite. An open conversation where anyone can join in and contribute their own GIFs. http://joyofgif.tumblr.com/

Marc garrett: You have joined The Photographers’ Gallery and as part of the new digital programme launched the exhibition “Born in 1987: The Animated GIF”. Could you tell us about this project?

Katrina Sluis: The digital programme presents projects both online and offline, which respond to recent dramatic shifts in the digital image as it becomes increasingly screen-based and networked. As part of this new programme we have launched ‘The Wall’ – a permanent exhibition space on the ground floor of the Gallery, visible both to visitors and passersby on Ramillies street. The Wall itself is a 2.7 x 3m Sharp video wall which we installed after considering a number of different technologies. We were conscious not to use digital projection as it would locate the project within traditions of cinema and video art, and we wanted the screens to respond to the reception and distribution of images within wider visual culture.

For the opening show, we decided to focus on the animated gif for a number of reasons. Firstly, the gif is a uniquely screen-based image format, in which the specific characteristics and limitations of the image file are inherent to the form, in contrast to the other kinds of images the gallery might show which might adopt digital techniques but result in traditional print-based photographic work destined for the gallery space.

I also wanted to disrupt certain expectations about the screens – the fetishisation of resolution and image quality, and what kinds of photographs The Wall’s programme might seek to address. The animated gif in this sense is very interesting – it is one of the first image file formats native to the web, and although it is 25 years old this year it has been undergoing a resurgence on platforms such as Tumblr. In a commissioned essay for the show, Daniel Rubinstein speculates that current resurgence of the gif “is not only part of the nostalgic turn towards the blurred, the unsharp and the faded but it is also a marker of a moment when the history of the network becomes the material from which the digital image draws its living energy.”[1] Frequently authorless and contextless, the gif image works on a different economy in which its value is based not on its uniqueness and scarcity (as in certain forms of art) but its circulation and proliferation. Although there have been significant practitioners of the gif form, it is a format which ultimately resists canonization. And, in the context of a photography gallery, it opens up other debates concerning medium specificity and the ‘post-photographic’.

In approaching the exhibition, I was keen to ask a diverse range of photographers, writers, organizations and other practitioners to contribute a gif for the show. In keeping with the unmonumental nature of the form, I asked contributors to respond within a short timeframe of 7 days. For many contributors, this was the first time they had made a gif; but other contributors already had large followings on Tumblr and some were established net artists. This opening show and associated Tumblr site (http://joyofgif.tumblr.com) became a starting proposition for the project in order to then open up The Wall to gif contributions from the wider public. We will continue to update The Wall with public responses on a daily basis until the final day of the show on 10th July.

MG: At first, some may assume that the first part of the exhibition title ‘Born in 1987’, refers to the fact that today so many young people using computers these days were born in 1987. Yet, the GIF format, short for ‘Graphics Interchange Format’, was introduced to the world of computers by CompuServe in 1987. Was the title of the show deliberately playing with both notions?

KS: I like this idea! The title does self consciously play with the way in which the digital is valorised for its endless ‘newness’ and novelty but yet has this long and frequently overlooked history of creative experimentation. You can also see this reflected in the recent hype around the work of Kevin Burg and Jamie Beck who have (problematically and entrepreneurially) re-branded the gif as the ‘cinemagraph’.

MG: Do you consider this project to be net art, if so, how does it relate to other forms of net art?

KS: The project (and The Wall’s programming) does pose certain problems as it seeks to relocate certain forms of online practice(s) into the space of the art museum. At the same time, the project exists in an online context with its own very different life on Tumbr, where the work circulates in a very different context with a very different audience. I think there are many interesting opportunities which emerge from this intersection of the institutional frame of the museum (with its associated issues of cultural and curatorial authority and the legacy of aesthetic modernism) and the values and politics which inform certain kinds of networked arts practices.

But I also think the project also needs to be understood in the specific context of The Photographers’ Gallery, its history and audience. Whilst the project shares the concerns of net art by raising questions concerning authenticity, authorship and ‘the social’, it is also motivated by the need to rethink familiar notions of photography and temporality, indexicality and the economy of the image – concerns which presently haunt the field of photography theory.

![Kennard Phillipps. GIF image by Peter Kennard and Cat Phillipps. Born in 1987: The Animated GIF. The Photographers' Gallery 2012 [2]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/fuck-the-markets-latest1.gif)

![Rad Racer glitch 3. GIF image by tracekaiser. Born in 1987: The Animated GIF. The Photographers' Gallery. 2012 [3]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/tumblr_m5tqfl62wl1qew2moo1_400.gif)

MG: In what way do you see this form of creativity relating to others who may not be so well versed with net art culture, or digital networked practices?

KS: The Wall presents an opportunity for the Gallery to collaborate with diverse communities who can bring their distinct expertise and experiences to the programme, and the net art community has much to offer in this respect. For this reason, we aim to develop The Wall’s future programme through the framework of ‘collaborative research’, in which our audience, along with the organizations we partner with, are potential co-researchers. The co-researcher model developed as an approach to research democracy in the Social Sciences, particularly in the approach of Action Research in the NHS but in a more relevant cultural example was used extensively in the Tate Encounters: Britishness and Visual Culture research project. Co-research recognises both the collaborative and collective nature of meaning construction, through a process which attempts to trace and reveal the complex manufacture of meaning.

At the same time, there is still another related project to be done in highlighting and responding to digital projects whose life is online – this is of course something I admire Furtherfield for doing so brilliantly. On a smaller scale and with a more narrow focus, we hope to launch a blog which will draw attention to online work which relate to photography as it becomes polluted, valorized, hybridized and networked.

![GIF image by Paul Flannery. Born in 1987: The Animated GIF. The Photographers' Gallery. 2012 [4]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/tumblr_m442xish4q1rvlji4o1_500b_0.gif)

MG: Some, may view this this exhibition as relating to Internet Folk Art. There is an interesting article by Kenneth Goldsmith[1] where he discusses the digital theorist Rick Prelinger’s claim “that archiving is the new folk art, something that is widely practiced and has unconsciously become integrated into a great many people’s lives, potentially transforming a necessity into a work of art.”

Now, this is not directly relating to the show itself, but it resonates something regarding the inclusiveness of the show. So, in respect of it ‘possibly’ possessing aspects of Folk Art, what connections do you see as relevant or not, and what does it mean to you?

KS: By focusing on the gif the show does problematise the distinction between artist and audience, in which participation, openness and the ‘crafting’ of the image becomes key. However I have reservations about the use of the term Internet folk art, which could be construed as imposing a certain modernist logic on the discussion, burdening it with an analogue modeling of high and low culture. The research approach has been adopted precisely to avoid the trap of binary nominalism, and to problematise the tendency to shoe horn internet practices into the language of cultural studies and aesthetics.

MG: The Photographers’ Gallery was the first independent gallery in Britain devoted to photography and has been going since the 70s. It is the UK’s primary venue for photography and has been dedicated in establishing photography as an essential medium, representing its practice in culture and society. It seems that The Photographers’ Gallery is going through another transition. You have already mentioned how hybridized and networked the nature of future projects will be. So what kind of exhibitions and projects can we expect in the future?

KS: Because digital technology is not in itself a new photographic medium, but essentially a hybrid and converged set of technological practices, it raises many interesting problems, both theoretical and practical for a Gallery focused on photography. To the computer, the photograph is indistinguishable from the other binary blobs of data we used to call books, films and songs. The crisis of digitization and medium specificity now extends to the domain of the camera – Digital SLRs are coveted for their ability to shoot high quality digital video, and we turn to our mobile phones when we want to take snapshots. This is a very rich context for the programme to explore, and ideally the future projects will respond to the technical, creative and cultural languages of photography as produced by computer engineers, web developers, photographers, artists, networked communities, social scientists and other practitioners.

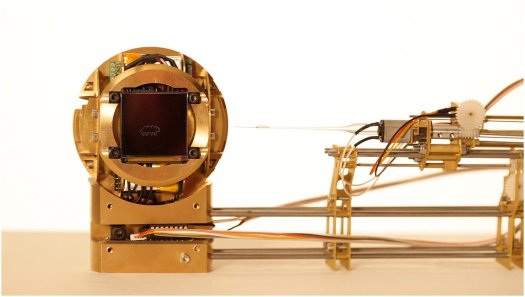

Our next show on The Wall (opening 13th July) features the practice based research of Susan Sloan into portraiture using motion capture and 3D animation techniques widely used in entertainment, medicine and the military. Her motion studies refer to the traditions and conventions of portraiture and the changing role of the camera as a recording device. At the same time, her work raises questions concerning the convergence of painting, animation, film and photography in the digital realm.

The future digital programme which will occupy different spaces and address various photographic practices including augmented reality, social media, electronic publishing, interactive media, mobile computing and synthetic imaging.

The Joy of GIF – the London Photographers’ Gallery’s new digital wall. Article by Wendy McMurdo.

http://www.foam.org/foam-blog/2012/may/photographers-gallery

Sign up: ale[at]furtherfield.org

See images of the walk on Flickr.

Public exploratory radiation walk around Finsbury Park, measuring mobile phone radiation levels and discovering what type of radiations we are exposed to on a daily basis. As we walk, we will unravel a parallel, hidden story of the local area along with technical data and possible medical effects of the radiation. Participants will measure radiation levels, GPS positions and marked levels on a large map of the area, creating a collaborative artwork (poster sized map of local radiation) to be made available for display as part of the exhibition after the event.

Participants are encouraged to listen to the sounds we will be hunting for (GSM, 3G, Tetra) here.

Dave Miller

Dave Miller is a South London based artist and currently a Research Fellow in Augmented Reality at the University of Bedfordshire. Through his art practice Dave draws out the invisible forces that make life difficult. His work is about caring and being angry, as an artist. His art enables him to express feelings about the world, to attempt to explain things in a meaningful, yet subjective way, and make complexed information accessible. Recurrent themes in his work are: human stories, injustices, contentious issues and campaigning. Recently he’s been very bothered by the financial crisis.

+ Finsbury Park Radiation Walk is part of Invisible Forces at Furtherfield Gallery.

+ More Invisible Forces events.

3 Keys – The River Oracle by the Hexists is the opening act of the Moving Forest 12 hour performance.

+ Listen to the sounds of Act 0 ‘Omen’ for the Moving Forest London 2012

1. Introduction ‘Output 1’

2. Omen Section 1 ‘Output 3 and 4’

3. Omen Section 1 ‘Output 5’

+ And download the score for the Hackney Brook.

Cybernetic systems and game theory are about anticipating and influencing human behaviour using algorithmic code, databases, social media etc – the industries of data-mining, data profiling and data protection can be said to be the new ‘magic’ by which biopolitical control of our bodies and identities is maintained.

3 Keys – The River Oracle with The Hexists is a game of chance and divination in association with The Moving Forest, Act 0. It attempts to invoke the relationship between the divinatory functions of our contemporary ‘influencing machines’ (cybernetic systems and game theory using data-mining, data profiling and data protection) and traditional magical ones, creating new machines in the process. Using tools such as cards, dowsing, stick throwing to interpret phenomena in the landscape, historical and current, ‘readings’ can be cast, allowing associative action, language and thought to determine what might happen in the future, to create a path, an artwork.

In 3 Keys (version 3), participants will follow the Hackney Brook, an old subterranean river that begins near Finsbury Park and ends up in the River Lea near the site of the Olympics, using different exercises to interpret the landscape and cast readings. We will ‘mark’ the route along the way with objects and stories and other inscriptions. The river is the oracle and we are the transmisson. The documentation and divination tools will be made available for display in the exhibition after the event.

IMAGES FROM THE WALK ON FLICKR

Rachel Baker

(The Hexists)

Rachel Baker is a network artist who collaborated on the influential irational.org. Her art practice explores techniques used in contemporary marketing to gather and distribute data for the purposes of manipulation and propaganda. Networks of all kinds are “sites” for Baker’s public and private distributed art practice, including radio combined with Internet (Net.radio), mobile phones and SMS messaging, and rail networks.

Kayle Brandon

(The Hexists)

Kayle Brandon is a inter-disciplinary Artist/researcher, whose work is sited within the public, social realm. She predominantly works in collaborative and collective fields; a working method which informs much of her ethos around the making of art. Her main areas of interest are in the relationships between the natural and urban worlds and Human/Non-human relations. She investigates this field via physical intelligence, provocative intervention, observation, self-guided exploration and collective experiences.

First presented at Transmediale.08. Berlin 2008, Moving Forest London maps an imaginary castle and a camouflaged forest revolt onto the hyper-playground of the London metropolis on the eve of Olympics 2012. Presented by a temporarily assembled troupe AKA the castle, Moving Forest brings together diverse visual/sonic/electronic/digital/ performance artists along with writers, walkers, coders, hackers, mobile agents, twitters, networkers and the general public to realize a contemporary version of a classic play.

http://www.movingforest.net/

DOWNLOAD A PRESS RELEASE HERE

+ 3 Keys – The River Oracle is part of Invisible Forces at Furtherfield Gallery.

+ More Invisible Forces events.

The insights of American anarchist ecologist Murray Bookchin, into environmental crisis, hinge on a social conception of ecology that problematises the role of domination in culture. His ideas become increasingly relevant to those working with digital technologies in the post-industrial information age, as big business daily develops new tools and techniques to exploit our sociality across high-speed networks (digital and physical). According to Bookchin our fragile ecological state is bound up with a social pathology. Hierarchical systems and class relationships so thoroughly permeate contemporary human society that the idea of dominating the environment (in order to extract natural resources or to minimise disruption to our daily schedules of work and leisure) seems perfectly natural in spite of the catastrophic consequences for future life on earth (Bookchin 1991). Strategies for economic, technical and social innovation that fixate on establishing ever more efficient and productive systems of control and growth, deployed by fewer, more centralised agents have been shown conclusively to be both unjust and environmentally unsustainable (Jackson 2009). Humanity needs new strategies for social and material renewal and to develop more diverse and lively ecologies of ideas, occupations and values.

In critical media art culture, where artistic and technical cultures intersect, alternative perspectives are emerging in the context of the collapsing natural environment and financial markets; alternatives to those produced (on the one hand) by established ‘high’ art-world markets and institutions and (on the other) the network of ubiquitous user owned devices and corporate social media. The dominating effects of centralised systems are disturbed by more distributed, collaborative forms of creativity. Artists play within and across contemporary networks (digital, social and physical) disrupting business as usual and embedded habits and attitudes of techno-consumerism. Contemporary cultural infrastructures (institutional and technical), their systems and protocols are taken as the materials and context for artistic and social production in the form of critical play, investigation and manipulation.

This essay presents We Won’t Fly for Art, a media art project initiated by artists Marc Garrett and I in April 2009 in which we used online social networks to activate the rhetoric of Gustav Metzger’s earlier protest work Reduce Art Flights (from 2007) in order to reduce art-world-generated carbon emissions... Download full text (pdf- 88Kb) >

Published in PAYING ATTENTION: Towards a Critique of the Attention Economy

Special Issue of CULTURE MACHINE VOL 13 2012 by Patrick Crogan and Samuel Kinsley.

Sign up: ale[at]furtherfield.org

Saturday 23 June 2012, 1-5pm

Summer Board Games and Picnic with Class Wargames and Kimathi Donkor

Join us for a day of debate around the leader of the Haitian Revolution, Toussaint Louverture, now regarded as an important icon of anti-slavery struggles. Class Wargames interviews the artist Kimathi Donkor who created the history painting Toussaint Louverture at Bedourete to mark 200 years since the independence of Haiti. The event will kick off with a picnic in the park and continue with an afternoon of collective playing of Guy Debord’s The Game of War, a Napoleonic-era military strategy game where armies must maintain their communications structure to survive – and where victory is achieved by smashing your opponent’s supply network rather than by taking their pieces.

In a short film by Ilze Black, Dr Richard Barbrook and Fabian Tompsett of Class Wargames interview Donkor about the work. Alex Verness from Class Wargames will be documenting the day by taking xenographs of participants.

IMAGES FROM THE TALK ON FLICKR

Saturday 30 June 2012, 1-5pm

Summer Board Games and Picnic with Class Wargames

Join us for a talk about gaming the 1791-1804 Haitian Revolution led by Richard Barbrook and Fabian Tompsett of Class Wargames. The event will kick off with a picnic in the park and continue with an afternoon of collective playing of Richard Borg’s Commands & Colors, a Napoleonic-era military strategy game.

IMAGES FROM THE EVENT ON FLICKR

Class Wargames

Class Wargames is an avant-garde movement of artists, activists, and theoreticians engaged in the production of works of ludic subversion in the bureaucratic society of controlled consumption.

The members of Class Wargames are Dr. Richard Barbrook, author and senior lecturer in the Department of Politics & IR at the University of Westminster; Rod Dickinson, artist and lecturer at University of the West of England; Alex Veness, artist and co-founder of Class Wargames;Ilze Black, media artist and producer; Fabian Tompsett, initiator of London Psychogeographical Association and author; Mark Copplestone, author and figure designer; Lucy Blake, Software developer; Stefan Lutschinger, lecturer, artist and researcher; and Elena Vorontsova, World Radio Network and journalist.

Kimathi Donkor

Kimathi Donkor lives and works in London. He attained his B.A. at Goldsmiths and an M.A. at Camberwell College of Art, both in Fine Art. In 2011 he received the Derek Hill Award painting scholarship for the British School at Rome; and, in 2010, his paintings were exhibited in the 29th São Paulo Biennial, Brazil.

+ Summer Board Games and Picnic is part of Invisible Forces at Furtherfield Gallery.

+ More Invisible Forces events.

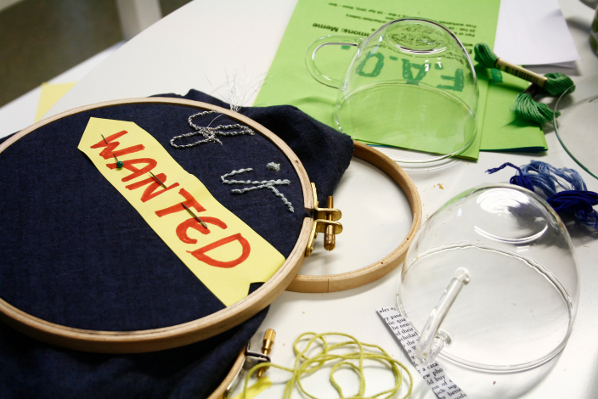

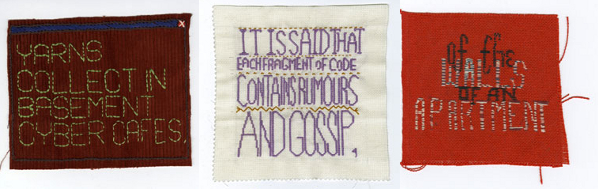

As part of the Being Social exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery in Spring 2012, Ele Carpenter and Emilie Giles facilitated embroidery sessions with gallery visitors who stitched a term from the Raqs Media Collective’s text ‘A Concise Lexicon of/for the Digital Commons’ (2003).

View images from the workshops

The Embroidered Digital Commons is a collectively stitched version of ‘A Concise Lexicon of/for the Digital Commons’ by the Raqs Media Collective (2003). The project seeks to hand-embroider the whole lexicon, term by term, through workshops and events as a practical way of close-reading and discussing the text and its current meaning.

Crafters, programmers, artists, makers, and people interested in working collaboratively, or taking part in participatory projects gathered to each stitch a few words of the term meme, as described below. The resulting patches will be turned into a short film depicting the sequence of embroideries.

In 2003 the Raqs Media Collective wrote ‘A Concise Lexicon of/for the Digital Commons’. The full lexicon is an A-Z of the interrelationship between social, digital and material space. It weaves together an evolving language of the commons that is both poetic and informative. The terms of the lexicon are: Access, Bandwidth, Code, Data, Ensemble, Fractal, Gift, Heterogeneous, Iteration, Kernal, Liminal, Meme, Nodes, Orbit, Portability, Quotidian, Rescension, Site, Tools, Ubiquity, Vector, Web, Xenophilly, Yarn, and Zone.

The concept of the digital commons is based on the potential for everything that is digital to be common to all. Like common grazing land, this can mean commonly owned, commonly accessed or commonly available. But all of these blurred positions of status and ownership have complex repercussions in the field of intellectual property and copyright. The commons has become synonymous with digital media through the discourse surrounding free and open source software and creative commons licensing. The digital commons is a response to the inherent ‘copy n paste’ reproducibility of digital data, and the cultural forms that they support. Instead of trying to restrict access, the digital commons invite open participation in the production of ideas and culture. Where culture is not something you buy, but something you do.

MEME

“Meme: The life form of ideas. A bad idea is a dead meme. The transience as well as the spread of ideas can be attributed to the fact that they replicate, reproduce and proliferate at high speed. Ideas, in their infectious state, are memes. Memes may be likened to those images, thoughts and ways of doing or understanding things that attach themselves, like viruses, to events, memories and experiences, often without their host or vehicle being fully aware of the fact that they are providing a location and transport to a meme. The ideas that can survive and be fertile on the harshest terrain tend to do so, because they are ready to allow for replicas of themselves, or permit frequent and far-reaching borrowals of their elements in combination with material taken from other memes. If sufficient new memes enter a system of signs, they can radically alter what is being signified. Cities are both breeding grounds and terminal wards for memes. To be a meme is a condition that every work with images and sounds could aspire towards, if it wanted to be infectious, and travel. Dispersal and infection are the key to the survival of any idea. A work with images, sounds and texts, needs to be portable and vulnerable, not static and immune, in order to be alive. It must be easy to take apart and assemble, it must be easy to translate, but difficult to paraphrase, and easy to gift. A dead meme is a bad idea.”

Ele Carpenter

Ele Carpenter is a curator based in London. Her creative and curatorial practice investigates specific socio-political cultural contexts in collaboration with artists, makers, amateurs and experts. She is a lecturer in Curating at Goldsmiths College, University of London.

Since 2005 Ele has facilitated the Open Source Embroidery project using embroidery and code as a tool to investigate the language and ethics of participatory production and distribution. The Open Source Embroidery exhibition (Furtherfield, 2008; BildMuseet Umeå Sweden, 2009; Museum of Craft and Folk Art, San Francisco, 2010) presented work by over 30 artists, including the finished Html Patchwork now on display at the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park. Ele is currently facilitating the ‘Embroidered Digital Commons’ a distributed embroidery exploring collective work and ownership 2008 – 2013.

Emilie Giles

Emilie Giles is an alumnus of MA Interactive Media: Critical Theory and Practice at Goldsmiths College. Since graduating in 2010 her time has been spent co-organising MzTEK, a women’s technology and arts collective, as well as completing an internship with arts group Blast Theory and working for social video distributors Unruly. She is currently involved with TESTIMONIES, a project which explores oral history in relation to the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games largely through social media.

Emilie’s own practice revolves around notions of pervasive gaming, married with urban exploration and psychogeography. Her most recent focus lies in taking fundamental gaming principles from Geocaching and exploring the consequences of adding an emotional dimension.

Sign up: ale[at]furtherfield.org

To accompany Invisible Forces, Furtherfield invites all gallery visitors to take part in a programme of public play, games, making and discussion led by alert and energetic artists, techies, makers and thinkers: Class Wargames, The Hexists, Dave Miller, Olga P Massanet and Thomas Aston.

Saturday 23 June 2012 – 1-5pm

Summer Board Games and Picnic with Class Wargames and Kimathi Donkor

Saturday 30 June 2012 – 1-5pm

Summer Board Games and Picnic with Class Wargames

Wednesday 04 July 2012 – 9-11am

3 Keys – The River Oracle – The Hexists

as part of Moving Forest by AKA The Castle

Wednesday 11 July 2012 – 11-5pm

Technologies of Attunement – Olga P Massanet and Thomas Cade Aston

Saturday 21 July 2012 – 2-5pm

Dave Miller’s Finsbury Park Radiation Walk

Featured image: Artist Suguru Goto discusses his work.

London 2012: there is of course one event which springs to mind when we think about this city and the year we’re in, but there is also another significant event happening in London right now, one which is very important for the digital and media arts world. It is the year that Watermans Arts Centre is holding the International Festival of Digital Art 2012.

As well as showcasing an array of digital art by internationally renowned artists, the programme also offers the opportunity for members of the public to get involved in discussions around themes that the Festival touches on through the seminar series accompanying the shows. These are in collaboration with Goldsmiths, University of London. Nearly three months in, the Festival has launched two exciting shows,Cymatics by Suguru Goto and UNITY by One-Room Shack Collective.

The first show, Cymatics, is a kinetic sound and sculpture installation that expresses Goto’s vision of nature. To enter it, the audience step through a door into a boxed, dark room within which they are presented with a touch screen interface, a shallow metal tank holding water and a screen showing a video feed of the water in the tank. The piece invites the audience to move the water in the tank by manipulating sound waves via an interactive screen. The result of the interaction is a stunning variety of geometric shapes, demonstrating the distortion that sound waves can have on a substance. This occurrence reveals the bridge between technology and nature, which fits into Goto’s re-occurring theme within his work of the relationship between man and machine.

The seminar which coincided with the show, Interactivity and Audience Engagement, was chaired by Régine Debatty and featured on the panel Tine Bech, Graeme Crowley and Tom Keene, all who which explore audience engagement in different ways within their work. Tine Bech is a visual artist and researcher whose installations invite audiences to engage in playful interactions, from chasing a motion reactive spotlight in Catch Me Nowto sound triggering shoes in Mememe. Tom Keene is an artist technologist whose focus intersects participation, communication and technology. His work is multidisciplinary, investigating the way we communicate, mediated by technology. His practice is diverse, from exploring the potential relationships between networked everyday objects in Aristotles Office to inviting a community to comment on their local issues through signs in Sign X Here. Graeme Crowley is a designer and artist who has created installations for prominent public areas, including The Wall of Light, commissioned by Arrowcroft Plc for the centre of Coventry and Spiral/Bloom commissioned for a hospital in Rochford by the NHS.

I found the juxtaposition of these three practitioners very interesting as each of them explore the interaction between audience and technology in varying ways. Bech’s work is very tactile and sculptural, almost making people forget the technology behind it. She likes to look at technology as something we can mould and which can be used to explore the wider issues which art can bring up, rather than just focussing on the tech itself and how ‘shiny’ (to use her own term) it is. In contrast to this, within Keene’s practice technology feels very prominent, visually as well as conceptually. Crowley’s focus is different again as it mostly operates within the commercial sphere. It therefore is produced for greater public consumption and needs to withstand being a permanent exhibit, becoming part of the architecture it is planted on rather than something which is temporary. The talks given by each panel member and discussions which accompanied them were all diverse and brought up interesting points around the idea of audience engagement and interactivity. Members of the audience entered into these discussions with ease, creating an open dialogue which itself was participatory and engaging.

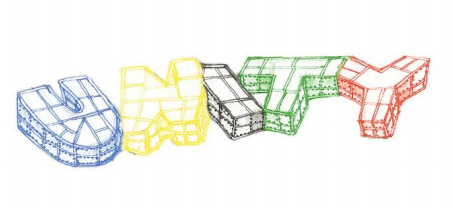

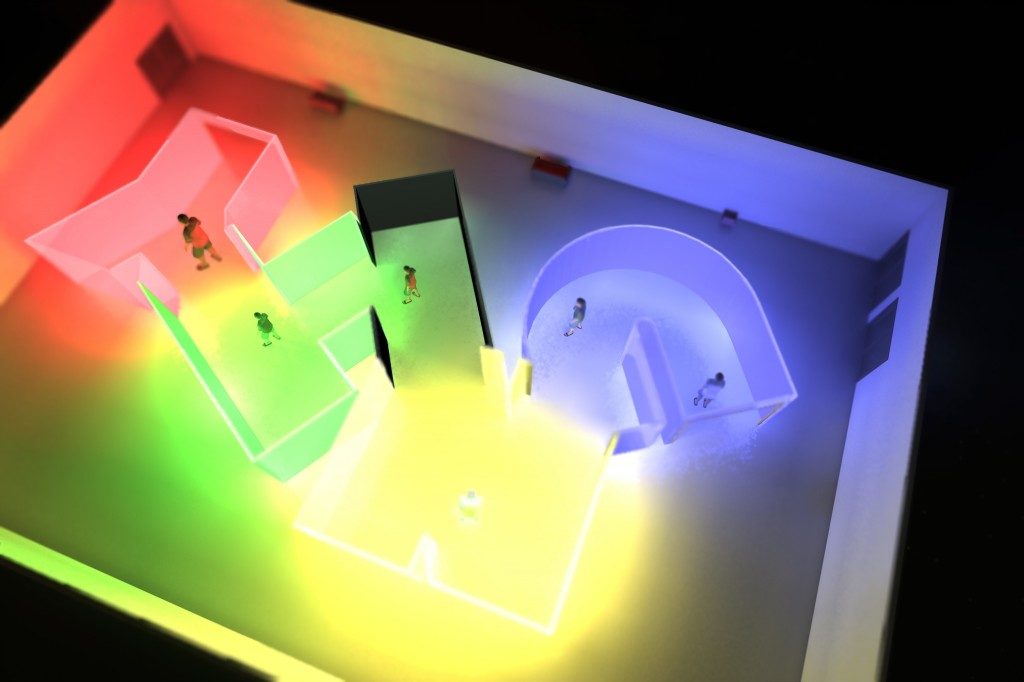

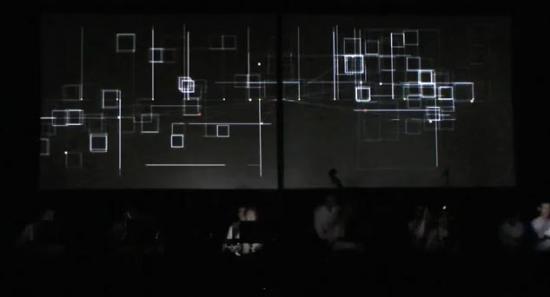

UNITY, by One Room Shack is the current exhibit as part of the International Festival of Digital Art 2012, bringing a piece of work to the gallery which aims to embody the Olympic spirit, visually as well as conceptually.

Design for Unity

The installation takes the form of a transparent maze, angular in its structure and illuminated with different coloured LED lights in each section. Each illuminated section of the structure forms a different letter, all together spelling the word ‘unity’. As the audience navigate their way through the installation, their movement is picked up by motion sensors, triggering the LEDs at each point to turn on. These each represent a particular colour of the Olympic rings.

The ideologies of the Olympic Games linked with an immersive space explores the value of ‘being together’, something which the African humanist philosophy Ubuntu also speaks about.

UNITY is effective in exploring the theoretical concepts embedded within it through a playful and simple interactive structure. As an individual you step from section to section with the different groups of LEDs individually illuminating you as you go through the work. When a group of people interact with the piece at the same time however, the piece lights up as a whole, echoing the values of being together that UNITY invites us to explore. It is through enabling this experience, that the work celebrates and explores human connections.

I do find it interesting how the piece has such a strong stance towards the more idealistic ideologies of the Olympics, especially when taking into account the anti Olympics sentiment present in London. The event does bring people together, but unfortunately as we’ve seen in East London and also at previous Olympic locations across the globe, they also have the ability to put local communities at risk through rising rents and eviction [1]. UNITY looks at ‘…understanding the implication of UNITY on humanism in a neo-liberal world where hyper-capitalism and love of excess trump compassion and selflessness.’ [2] but in reality, the Olympics have unfortunately become something which arguably embody these traits. This said, I do think that UNITY is an incredibly beautiful piece in its visual execution and that its interaction compliments the theoretical idea which it is looking to address.

I look forward to the remainder of the International Festival of Digital Art 2012 and the eclectic ideas within media and digital art which the programme explores. I interviewed Irini Papadimitriou, Head of New Media Arts Development at Watermans, about the Festival:

Emilie Giles: First of all, can you tell us what the premise is behind the International Festival of Digital Art 2012?

Irini Papadimitriou: The idea behind the Festival started from a decision to develop a series of shows that could form a discussion rather than being one-off exhibitions and help engage more people in the programme. In the last year we have been focusing more in participatory and/or interactive installations so I thought it’d be interesting to dedicate this project and discussions in exploring more ideas behind media artworks that invite audience engagement as a way of understanding our work in the past year.

Since this was going to take place in 2012 we felt it would be necessary to open this up to international artists so this is how the open call for submissions came up last year. We received so many great proposals it’s been very hard to reach the final selection, but at the same time the opportunity of having a year-long festival meant we could involve as many people as possible and hear many voices not only through the exhibitions (this is just one part of the Festival) but also with other parallel events such as the discussions, presentations of work in progress by younger artists and students, the publication, a Dorkboat (coming up in June with Alan Turing celebrations), as well as collaborations with other organisations or artists’ networks and online.

EG: Touching on your last answer, the Festival has a clear aim then to engage people in discussion rather than just being viewers of a show. Do you think that within media and digital art there is a particular need for this approach?

IP: I think that hearing people’s thoughts and responses and enabling discussion is important for all exhibitions and art events but specifically for the Festival (since the aim is to question & explore audience participation). It was very relevant to hear ideas and views from other artists, technologists, practitioners etc but also audiences, rather than just the participating artists.

Also, and this is my view, I think as media and digital art use technologies that many of us are not particularly familiar with or if we use technologies it will be most probably as consumers, it’s important to talk about and discuss the process (as well as impact of technologies) both for the artists as well as for audiences.

EG: The themes chosen for the programme are diverse and each relevant to media and digital art in their own way. What are the reasons for each focus and why?

IP: The themes explored in the Festival result mainly from the selected proposals and discussions with the artists. There were so many things to talk about so having these themes was a way to start from somewhere and help understand better the installations shown throughout the year. The seminars that we are organising are an opportunity for the artists to talk about their work and share their ideas with both audiences but also with other artists invited to take part in the panels. It is also a way of discussing these themes and presenting other work that raises similar issues. The seminars are shaped around the themes such as perception and magic in digital art, sound and gesture, geographies, virtual spaces as artistic mediums and of course participation and interaction. We are currently working on a publication with Leonardo Electronic Almanac which will be coming out in the next couple of months and will include essays from artists, academics and students as well as interviews with the artists behind the selected proposals. Again the catalogue has the Festival themes as a starting point but we tried to combine different content and ways of communicating these.

EG: How do the pieces featured in the exhibition question audience engagement, participation and accessibility ?

IP: The artists presenting work are exploring participation and audience engagement in different ways and I think we will have also interesting outcomes from the seminars and the publication which will allow us to explore these ideas further.

In the current installation, UNITY, One Room Shack collective are using the playful structure of a maze (in the form of the word UNITY with each letter lighting up in the colours of the Olympic rings) inviting people to walk inside to reflect and draw upon the complex nature of human reality and ‘difficult’ aspects of human existence.

Michele Barker and Anna Munster who will be showing HokusPokus later on are interested in exploring how we perceive actively in relation to our environment, how we see, what we see and how this makes us ‘interact’. HokusPokus inspired from neuroscience examines illusionistic and performative aspects of magic to explore human perception, movement and senses. The tricks shown in HokusPokus have not been digitally manipulated; they will unfold temporally and spatially, amplifying and intensifying aspects of close-up magic such as the flourish and sleight of hand.

The Festival will close with an installation by American artist Joseph Farbrook, Strata-Caster, which was created in Second Life mirroring the physical world, exploring positions of power, ownership, identity and drawing parallels between virtual and physical worlds. An interesting and important part of the installation is the use of a wheelchair by visitors to enter and navigate Strata-Caster.

EG: How have the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games inspired the Watermans International Festival of Digital Art?

IP: As we are trying to explore what participation is we thought it would be an interesting link (rather than inspiration) between the Festival and the Games/Cultural Olympiad since they are meant to symbolise, promote and inspire values like creativity, collaboration, participation, engagement etc. The Festival isn’t about the Olympics and participating artists didn’t have to propose work that linked to the Games, but we did receive many proposals that reflected on the Games, what they represent and the meaning of participation, so some of these proposals are being shown as part of the Festival, such as One Room Shack’s UNITY and Gail Pearce’s Going with the Flow.

How can designers and programmers work more harmoniously? How can the tools being created better meet the needs of users? There is a need for designers to have a greater role in the production of the tools that they use, aside from just reporting bugs, requesting features or designing logos for open source projects. This is where the Libre Graphics Research Unit comes in. The Libre Graphics Research Unit (LGRU) is a traveling lab where new ideas for creative tools are developed. The unit has grand aims, looking to bring aspects of open source software development to artistic practices. The programme, sponsored by many organisations in Europe, is split into four interconnected threads:

The first meeting, Networked Graphics, took place in Rotterdam from 7-10 December, 2011 and was Hosted by WORM. This second meeting, Co-Position, for which I was present, took place at venues across Brussels from 22-25 February 2012. Co-Position is described by LGRU as:

[…] an attempt to re-imagine lay-out from scratch. We will analyse the history of lay-out (from moveable type to compositing engines) in order to better understand how relations between workflow, material and media have been coded into our tools. We will look at emerging software for doing lay-out differently, but most importantly we want to sketch ideas for tools that combine elements of canvas editing, dynamic lay-out, networked lay-out, web-to-print and Print on Demand.

The meeting saw the coming together of many international artists, theorists and developers for four days of work around this subject. As some of the sessions of the meeting took place simultaneously I’m unable to give a full synopsis of the event. Instead, what is presented below are some of the key issues raised at the meeting.

The subject of copyright cannot be avoided when discussing digital art and collaborative practices. There is a definite need to foster a safe and welcoming environment for artists and designers to produce, share and remix their work. Licensing of artwork under Copyleft licences – such as Creative Commons – helps to create this environment.

In his presentation, entitled “Libre Workflows – A Tragedy In 3 Acts”, Aymeric Mansoux was quick to point out that Creative Commons licences do not cover the source of the artwork. To put it into context, a JPG is covered by a Creative Commons licence but is the XCF/PSD file? Mansoux also considered what is actually a finished piece of artwork? In a remix culture is an artwork ever finished? Mansoux refers to this quote from Michael Szpakowski for further elaboration:

I’ve found it helpful to think of any artwork, be it literary, visual art or music as a kind of fuzzy four dimensional manifold. So the “complete” artwork is the sum of all its instances in time, and all epiphenomena. The entire artwork, seen this way, is a real and precisely enumerable sum, a concrete, not imaginary, set, which could be knowable in its entirety by something long lived and far seeing enough.

From their home town of Porto, Portugal, Ana Carvalho and Ricardo Lafuente produce Libre Graphics Magazine with ginger coons who is based in Toronto, Canada. For the production of the magazine they use Git, with their repository being hosted on Gitorious. As a tool for sharing files between collaborators Git is very useful. However, they explained that they feel they are not making effective use of all that Git has to offer. Part of this comes from the complexity of using Git. There are more than 140 commands in Git, each with their own unique function. These are usually entered via the command-line, but there are a number of programs with a Graphical User Interface (GUI) available. Programs with a GUI are usually favoured over command-line programs as they remove some of the complexity. Carvalho and Lafuente have found, however, that many of of these GUI programs simply replace commands with buttons, which doesn’t remove any of the complexity in using Git. What is needed is an easy to use specialised tool for the production of art.

In this work session, presented by Ana Carvalho and Eric Schrijver, the work group imagined how to adapt existing version control tools to meet the needs of artists and designers. The session began by taking a look at how people currently implement version control. A common practice is to manually make backups, renaming files to differentiate between stages. This can be an effective way of making different versions, but it doesn’t address other issues such as making comparisons or merging changes. The ineffectiveness of these manual methods is soon very apparent. The work group was introduced to the Open Source Publishing (OSP) Visual Repository viewer, which begins to respond to some problems with current version control systems by providing thumbnails of files in a repository.

Using this as a basis we began to look at other functions that the OSP Visual Repository viewer should have, such as the ability to compare graphical files in different ways and to revert back to previous versions or merge versions. Although there was no time to produce working code we did seek to address the complex task of merging and comparing not only the ouput file but also the working files (svg/xcf/psd).

Every good work of software starts by scratching a developer’s personal itch.

This quote from The Cathedral and the Bazaar by Eric Steve Raymond could not be more accurate in describing the motivations behind the development of Laidout, developed by Tom Lechner, a comic artist from Portland, Oregon. Perhaps one of the most impressive software demonstrations of LGRU, Laidout is a program for laying out artwork on pages with any number of folds, which don’t even have to be rectangular.

In an attempt to devise new tags that can be added to the SVG specification, Michael Murtaugh and Stephanie Villayphiou presented a work session that looked at the different ways language is interpreted by both humans and computers. To address this the work group took part in a task that saw them act as an interpreter of commands. With nothing more than a list of tags used in SVG files the work group would attempt to construct shapes.

The results varied from person to person and highlighted an important question: How can computers interpret ambiguity

Using the Richard A Bolt “Put that there” demonstration, Murtaugh showed how human-computer interaction is still based around using very clear, unambiguous commands that can be easily interpreted by computers. In SVG only the most basic of shapes – rectangles, circles and lines – are represented. But, as the work group participants asked, could there be tags to represent more complex shapes, such as a horse?

On the final day of the meeting I took part in a roundtable discussion, chaired by Angela Plohman and featuring myself, Stephanie Vilayphiou, Camille Bissuel and Ana Carvalho. The discussion first went over all that we had achieved over the four days at the meeting, and then the discussion focused on how and why we share our artwork. Expanding on the earlier quote from Szpakowski, how can we make sharing all of our artwork – including the early stages and inspirations behind it – an easier and integrated part of making artwork? In addition to sharing our final, “finished” artworks do we want to also share our processes and ideas behind the artwork? More importantly, can software easily aid this?

Other topics debated in the discussion revolved around opening up our artwork and processes to others. By opening up the development process of our artwork do we do so to invite collaborators and contributions or just observers? The Blender Open projects, for example, are highly regarded as an example of the work that can be made using open source software. The files used to make these projects are are released upon completion of the project, but the development process remains closed to the team of artists and developers. Would opening up this process to contributors add any value or could having too many ideas dilute the original vision of the project.

Although no conclusions around these topics were made, it was nonetheless important for everyone at the meeting to think critically about their practice

A concern of mine is that research is not always acted up on and exciting possibilities exist only as theory. However, I feel that the approach of Libre Graphics Research Unit, which combines research and practice, will ensure that the work undertaken at the meetings is implemented. It is actively working with developers and users to try and create solutions.

At the Co-Poistion meeting not one final product was made, but the initial vision for the future of layout was formed.

The next meeting, Piksels and Lines, takes place in Bergen, Norway and is organised by Piksel.

This show is curated jointly by Helen Sloan of SCAN and the John Hansard Gallery, Southampton. There is both curatorial interest in the technological aspects of the work as well as the subject matter of the war artist. Sloan was approached by the Arts Council in terms of initiating a project for the ‘Interact’ series of commissions, on which she worked with David Cotterrell. In 2007, Coterrell went to Afghanistan as artist-in-residence for a month in a field hospital. At his residency in 2008, at SEOS (now Rockwell Collins), a company that makes flight simulators. He explored the nature of representation itself, and particularly ‘the suspension of disbelief’. This relates to our relationship with digital data, and how often we regard it as more real, due to its nominal representation of reality and our use of this as information.

What appear to be ‘A-life critters’, are in fact scaled down human forms. Trawling across a dust-sculpted landscape, the real of the chalk dust intersects with the virtual projections of the A-life program which is mapping the movement of these forms to the reality of the sculpted landscape.

David Cotterrell doesn’t want to show pictures of the atrocities of war, but instead focuses on the complex experience of lived space in territorial combat and its mapping. He presents a kind of ‘topo-analysis’ of an imaginary space, with nominal figures located and moving in spatial relationship to one another. In Observer Effect the gallery viewer triggers the movement of the virtual entities who are attracted by a ‘sphere of influence’ to the viewers position in the gallery space. In this way, the phenomenon of space, location and relationship and the concomitant fear of combat, casualty, and mortality are implicit in the context of this exhibition.

Cotterrell has chosen to interrogate image making using technology, much as Vilém Flusser recommended, together with a lack of acceptance of the ‘normal’ indexical uses of photography and film about which he is ambivalent, although he used these media in Afghanistan.

What these works achieve is the proposition of a ‘possible world’ where depersonalisation is understood as part of the virtual, nominal, mapped collective fantasy, which somehow then relates to the changing ‘world view’ of the Western citizen. It is also where the reference to science fiction comes from, ‘Monsters of the Id’ referring to the film Forbidden Planet. Science fiction is perhaps referred to in order to re-conceptualise our thinking as part of this Western view. In this sense it is about empowering us to think differently about the portrayal of conflict itself in the twenty-first century and to understand it as lived experience within specifically managed environments.

This is largely achieved through Cotterrell’s translation of his own experience as war artist in Afghanistan. He seems to want his experience to affect the viewer in a way which is different from that which he witnessed, to a reliance on the imagination instead, provoked by the portrayal of the landscape and militarised environment. Instead the exploration is one of attempting to convey the sense of isolation he felt in the military field hospital.

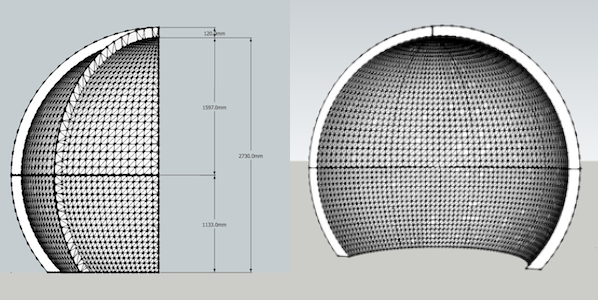

What becomes apparent on seeing this work, is that we are being presented with data objects, which we are then encouraged to relate to, as though they are the nominal representation of real subjects. It is significant that the work is realised with new technology. All three main works in the show explore a similar landscape but use three different projection systems. In Observer Effect the system relates to interaction with the gallery visitor who influences the installation in spatial relativity, through a device that senses and then calculates, through the algorithms and maths of a game engine, their relationship to the virtual space. Alternatively, in Searchlight 2, there is a synthesis between real and virtual as the figures traverse the landscape. He has said in relation to this piece that ‘from a great distance we lose empathy with the figures crossing the landscape’. In Apparent Horizon, the viewer encounters a semi-immersive relationship with video projected onto specially designed hemi-spheres, a view of the horizon, and a lengthy period of waiting for something to happen, which captures the tension between periods of violence. In this sense the artist has worked both as a war artist and as an artist using and developing the application of new technologies.

He talked about computer programming having a tendency towards ‘megalomaniac control’, and that the installation was addressed towards ‘how an audience inhabits a gallery’, with no ‘fetishizing of computers’. The residency at SEOS has obviously affected the nature of the technology employed in the work, with two ‘black boxes’ enabling aspects of the projections, as well as the hemi-spheres as immersive hardware. The system of Observer Effect is adaptive and therefore responds to the accumulated impact of viewers in the gallery. He talked about how a commercial games company would find it easy to make, but for him it had been a steep learning curve.

Cotterrell was able to return to Afghanistan in early 2008, due to support from the RSA, and was therefore able to look at the territory of the desert ‘outside the bubble of the military’, which had given him a limited understanding of the environment, a sense of dislocation, and the apprehension of casualties brought from the desert war zone. On this occasion he grew a beard and was able to disguise himself sufficiently so that he could interact with different groups of Afghani people and to gain a ‘pluralism of experience’, as on this occasion he was not part of the chain of command. In this second journey, he was ‘low value’ and therefore able to wander more freely.

Initially, he found it difficult to deliver art work in response to what he had experienced in Afghanistan. He was aware of the historical dilemma of the conflict between medicine and war. But for him, the trauma was ‘quieter’ and involved loss of identity. For example, the twenty-one year old soldier who after severe injury was ambiguous about what would happen for the rest of his life.

He found the operating theatre at the field hospital was ‘like a stage set’, and he took photographs of the surgeons, but found that the documentation ‘didn’t document’ sufficiently his lived experience. At one point he left a video camera running, documenting the arrival of casualties and then, when he was back at home, he edited the footage and left only the moments when attendant individuals ‘allowed their guard to drop’. He questioned though, whether ‘it was right to document trauma’. This left him with the ‘impossibility of conveying content’.

As war artist he has chosen to explore the military and political relationships with the technological portrayal of soldiers and civilians within a territorial combat zone. This is sufficient for Cotterrell in order to convey the sense of isolation and the particular landscape of Afghanistan. In this way, apprehending the virtual or nominal as a way of perceiving what could be real, and is real in a conflict situation, puts the viewer in a complex position, of both suspending disbelief and recognising the construct. The final work Monsters of the Id, includes in a small installation an army tent, desk and military communications equipment. This conjures up an image of Cotterrell’s experience as a war artist, although in fact it is his portrayal of how we might think of it – as naïve in other words.

For the team of curators, gallery staff, and the artist, it has been curatorially important to work within the gallery space and Cotterrell claims that the ‘virtual can only really be understood in a gallery context.’ This is enabled through the works being not fully immersive so that you can stand back and reflect. As such the show is all about ‘the manipulation of imagery’ informed by the residencies in Afghanistan and at SEOS.

The exhibition continues till 31 March 2012 at the John Hansard Gallery, Southampton

Featured image: Martijn de Waal, co-founder of The Mobile City, introduces the conference (image courtesy Virtueel Platform)

On Feb. 17th Amsterdam hosted Social Cities of Tomorrow, a conference on new media and urbanism. Adapting its title from Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of Tomorrow, but taking equal inspiration from the work of Archigram, the conference presented a snapshot of the direction cities are moving today: as conventional means of planning and designing are renegotiated through our engagement with new media technologies:

Organized by The Mobile City and Virtueel Platform, the event showcased best-practise examples of the use of media in urban analysis, design, art and activism. These ranged from “Homeless SMS”, a text-messaging system designed to provide information to the 70% of homeless Londoners who own cell phones; “Amsterdam Wastelands”, an on-line mapping of disused sites in Amsterdam and Zaanstad; “Koppelkiek”, a game project in which residents of a troubled area of Utrecht collected “couple snapshots” (in couples of friends, relatives or complete strangers), promoting social interaction through play; and “Urbanflow”, and New York-based project to rethink the contents of urban screens. In all, a dozen such projects were presented at the conference.

http://www.socialcitiesoftomorrow.nl/showcases

Immediately preceding the conference an intensive three-day workshop took place at ARCAM, the Amsterdam Centre for Architecture. This event brought together two dozen interdisciplinary creatives from around the world to tackle urban issues in four current case-studies: Haagse Havens, Den Haag; Zeeburgereiland; Strijp-S Eindhoven; and the Amsterdam Civic Innovator Network (a proposal to open up Amsterdam’s civic resources to distributed control by citizens). Working with local stakeholder organizations, the participants brainstormed how to leverage new media to solve intractable or new problems in these real-world sites.

http://www.socialcitiesoftomorrow.nl/workshop/the-four-cases

Also at ARCAM, a roundtable discussion on the alternative forms of trust emerging out of new media conditions was held, with panelists (below, left to right) Tim Vermeulen, Henry Mentink, Rietveld Landscape, Scott Burnham, Michiel de Lange (image courtesy Aurelie).

Keynote speakers Usman Haque, Natalie Jeremijenko, and Dan Hill concluded the conference with a panel discussion that placed the presentations in the context of distributed technology, contemporary art, social innovation, and architecture (image courtesy Virtueel Platform).

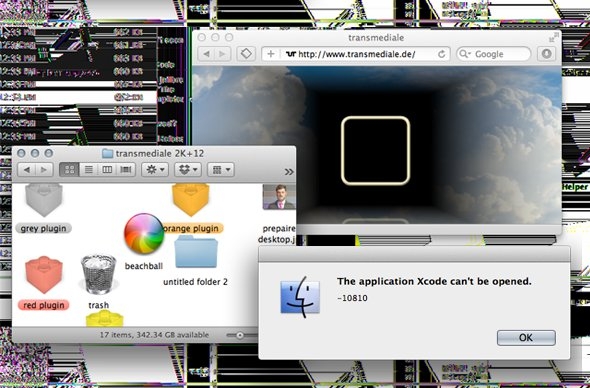

Featured image: ‘Promised Land’ design of transmediale 2k+12

Everything is not connected was the title of one of the talks organised as part of the in/compatible symposium at transmediale 2k+12 (2012), precisely the keynote speech of Graham Harman for the section titled systems. But this year’s programme of transmediale was all about connectedness, or I’d better say, about a curatorial structure of connectedness and subtle linkage.

The festival’s format was one of visual and conceptual reminders, and this became evident at the very beginning and during the opening ceremony, in the auditorium of the the Haus der Kulturen on the 31st January.

At the moment of opening a power point presentation, the new artistic director Kristoffer Gansing seemed to experience a technical problem as his file would not open. A technical assistant was then called on stage to fix it, and while we all giggled and looked at each other thinking that this was somewhat like a paradox for a festival devoted to the exploration of art, technology and media culture, we soon realised that the dooming technical failure was a pretext for one of the Prepared Desktop performances by glitch-artist jon.satrom.

Thus, from the very start, we experienced what Gansing often defined as a festival which “is an incompatible being”, suggesting that the 25th edition of transmediale would be different, perhaps more oriented to a multidirectional engagement with its audience and, surely, aimed at making us aware of how much technology is intrinsically part of our everyday lives – physically, mentally and also politically. It seems that Gansing had worked towards making us feel like explorers in order to experience what he described in his curatorial statement as the “in/compatible moment”, the “moment of stasis” resulting from the clash between things that were supposed to flow and converge peacefully within a system. That unforeseeable clash generated by an incompatibility which, according to him, is to be seen (and perhaps also sensed) as a moment full of potentials, as a gap which allows a new rearrangement of the elements of a given system – be it artistic, social, economic or political.

This ‘curatorial tactic’ marked the rich programme of transmediale 2012, which spanned from exhibitions to academic research networks, from online artistic interventions to talks and live performances – worth a mention is also the overall design of the festival’s contextual material, called the Promised Land design theme, which with its retro digital-pop aesthetic [1] seemed to have been devised to reinforce the idea of the clash, the tensions at work within the notion of technological convergence (“the myth” of contemporary society), starting from the very aesthetics of it.

The connectedness I mentioned above is very tangible when looking back at the main themes discussed at the in/compatible symposium – which was divided into three thematic segments:

systems, publics and aesthetics – in that they could be found as extensions across the whole programme, which in turn was developed across six sections:

1- the exhibition Dark Drives. Uneasy Energies in Technological Times curated by Jacob Lillemose

2- The Ghost in the Machine performance programme curated by Sandra Nauman

3- the video programme Satellite Stories curated by Marcel Schwierin

4- 25 Years, a series of events, amongst which talks and video screenings, about “areas of conflict between old and new” that were devised to mark the 25th anniversary of the festival

5- Featured Projects, a series of special parallel projects, such as web-based and site-specific

interventions

6- last but not least, the new addition of reSource for transmedial culture, an “interface between the cultural production of art festivals and collaborative networks of art and technology, hacktivism and politics” presented as a series of ongoing events (workshops, discussions, lectures and performative interventions) curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli.

Taking a step back to look at the overall thematic framework of the festival before digging into the specifics of each programme, what should be emphasised is the effort that was made to strengthen the transdisciplinary nature of the festival as a whole. In fact, each section of the programme inserted itself into the wider discourse of cultural production; putting a stress on how deeply technology is intertwined with the every day while looking at the relationship between art and technology from a socio-economic and political perspective that was permeated by an historical orientation. And the latter is precisely what makes this 25th edition different from those I had experienced before.

Gainsing’s perspective – as it was often stated by his collaborators throughout the festival – is that of a media archeologist; and in this sense he occupies a specific place in the media theory-scape of the city of Berlin, which houses the Institute for Time Based Media (Berlin University of Arts) where Siegfried Zielinski is the Chair of Media Theory. As many might know, Zielinski is the theorist who coined the term (or better still, founded the field of) media archaeology with his book Deep Time of the Media (MIT Press, 2002). I would then say that the methodological approach of the artistic director, as well as that of the four festival’s curators, was the one which looks at a present “linked to a past pointing at a possible future”, adopting a perspective that is different and finds “something new in the old” rather than seeking “the old in the new” (quotes from Zielinski, 2002). This is probably the reason of the festival’s holistic character, of the existence of critical and aesthetic linkage between the various panel discussions and performances, research projects and art installations.

This year’s symposium, across three different but converging angles, looked at the tension between functionality and disruption in order to address how the gap existing between the two has been (and could be) “productively used” by artists, as well as by society at large, in relation to available technology – mostly digital and web-related.

The strong connection existing between all panels – grouped under systems, chaired by Christopher Salter; publics, chaired by Krystian Woznicki; aesthetics, chaired by Rosa Menkman– was given by the historical approach of their explorations into the present. Their positions were those according to which it is not technology that impacts society, but it is almost the reversal: it is society – and artists – who, with their behaviours and actions, transform it, generating a new language and new possibilities within established systems, or failing systems. One way to embrace this type of perspective was described by Graham Harman in his keynote speech: it is through differentiating “between background and foreground” and bringing the latter “into consideration”, through accepting obsolescence as something inherent to the state of the technological thing and through embracing the fact that mediums change, that new ways of thinking and understanding reality can be established.

In this regard, the in/compatible aesthetics panels brought about interesting paradoxes in relation to media archeology and technological historicism, such as the necessity to move away from nostalgia for the past and avoid what could perhaps be termed as techno-romanticism. Through a series of panels, spanning from Uncorporated Subversion. Tactics, Glitches, Archeologies to Unstable and Vernacular. Vulgar and Trivial Articulations of Networked Communication, this section of the symposium presented a variegated array of artistic and research practices (from artist Olia Lialina to media theorist Jussi Parikka) that are concerned with establishing methods for challenging given systems, their codes and protocols, in order to establish new languages and modes of operation. All of them presented different artistic scenarios embedded in current socio-cultural frameworks, stressing the fact that “cultural history is shaped by users more than its inventors” (quote from artist and programmer Dragan Espenschied‘s presentation during the Unstable and Vernacular panel).

The publics section dealt with “forms of activism and social resistance” that emerge from incompatibility with the economic-political systems. In the instance of the Norifumi Ogawa in his talk Social Media in Disaster, during which he gave a very detailed insight into the “productive and effective” uses of social media during the recent Japanese earthquake and the consequent accidents at the Fukushima’s nuclear plant.

According to the exhibition curator Jacob Lillemose, Dark Drives “explores the idea that uneasy energies exist in technological times” and offers “a thematic reading and an historical mapping of the last fifty years, expressing a critical attitude to existing phenomena as well as exploring possibilities of reinvention”. And it does so with “no promise of overcoming” them (quotes from Lillemose’s curatorial statement).

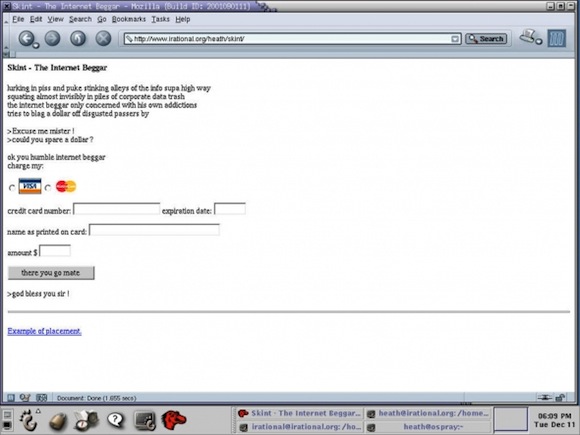

In fact, the exhibition included works by 36 artists spanning different cultural fields as well as periods. The inclusions ranged from Ant Farm’s Media Burn, Chris Burden’s Doorway to Heaven and William S. Burroughs/Antony Balch’s The Cut-Ups (late 60s and 70s) to Art 404’s 5 Million Dollars 1 Terabyte, Constant Dullaart’s Re: Deep Water Horizon (HEALED) and jon.sotrom’s QTzrk (2010/2011), all while moving through the practices of artists attached to the net.art movement, such as Heath Bunting’s Skint – The Internet Beggar and JODI – the latter with a new light installation, LED PH16/1R1G1B, dated 2011–. Included were also works produced in the 80s by music bands like SPK with their Information Overload Unit. Not only, but the show also presented works which are usually not associated with the conventional art circuit, such as the TV programme Web Warriors produced by Christopher Zimmer (2008) and the music video Come to Daddy by Chris Cunningham/Aphex Twin (1997), along with, as a reversal, old(er) media-oriented work, such as the series of computer prints Leaves by Sture Johannesson, which can be read as early pieces of conceptual art.

This condensed list is to say that the amount of artistic and cultural material on display in the exhibition and the trajectories that it opened were broad to such an extent that Dark Drives functioned more as a general narrative survey than a show with a clear proposition. It was a survey of how uneasy energies might materialise as consequences of the modes and methods in which technology is used and understood, with no much distinction drawn between technology in electronic, computational or digital times.

Dark Drives did not aim to address further its initial statement, nor to narrow down the kind of relationships (and their reasons) between historical instances and contemporary ones; and from my perspective this was its flaw. However, this is the kind of exhibition that a festival like transmediale eventually needed, because to my knowledge this sort of display and curatorial approach had not been presented before: an exhibition which finally embraced the inclusion, with no hierarchies or differentiation in terms of choices of display, of works conventionally shown in gallery spaces along with those traditionally related to (ahem) the still-existing ‘niche of new-media experts’.

Dark Drives might not be a very daring exhibition if placed outside the context of a media art festival like transmediale, but it is certainly almost subversive in this context, and in comparison with its precedents. The exhibition installation was clever and atmospheric and, as it was for the festival’s format, it was dotted by visual and aesthetic reminders. I’ll give you an example amongst many and various ones that you could have spotted in the show: formulas by Peter Luining (2005), which is a video about manipulating a screen-grabbed image in Photoshop till it becomes a black screen, was shown just a work before jon.sotrom’s Qtzrk (2011), another video based on the process of image deformation – in this case through the use of QuickTime 7; the latter, was, in turn, shown just another work before Heath Bunting’s Skint – The Internet Beggar (1996), a website that operates as a service through exploiting the potentials offered by the network system. The three works all adopted the framework of computer desktop as a display platform for their artistic interventions, but also as a production space. And although each artist’s agenda and research area were different, their proximity made these distinguishing elements more evident, highlighting various ways of activating modes of production that diverge from those of the system within which these artists operate.

Similarly to what I have just described, it was Dark Drives as a whole that guided the visitor all the way through its display towards specific thematic directions, which were suggested by the installation in conjunction with the many visual and aesthetic links. But simultaneously, the visitor would also be free to follow the other and many trajectories arising from the content of each specific work, and this flexibility made the exhibition an attractive narrative territory ready to be employed for further explorations.