Exhibition Tour and Artists Talk (Magnus Eriksson and Geraldine Juárez)

Saturday 03 May 2014, 2pm

Exhibition tour led by Magnus Eriksson and Geraldine Juárez followed by a live walk-through of the Piratbyrån archive and talk about some overlooked gems from their history at Furtherfield Commons. Expect to learn some Swedish while we are at it!

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

Contact: info@furtherfield.org

Curated by Rachel Falconer & Furtherfield

EXHIBITION TRAILER – Piracy as Friendship

@Furtherfield “Don’t contact future. Future will contact you!”

“For the last sixty years, capitalism has been running a pretty tight ship in the West. But in increasing numbers, pirates are hacking into the hull and the holes are starting to appear. Privately owned property, ideas, and privileges are leaking into the public domain beyond anyone’s control.” – Matt Mason, The Pirate’s Dilemma

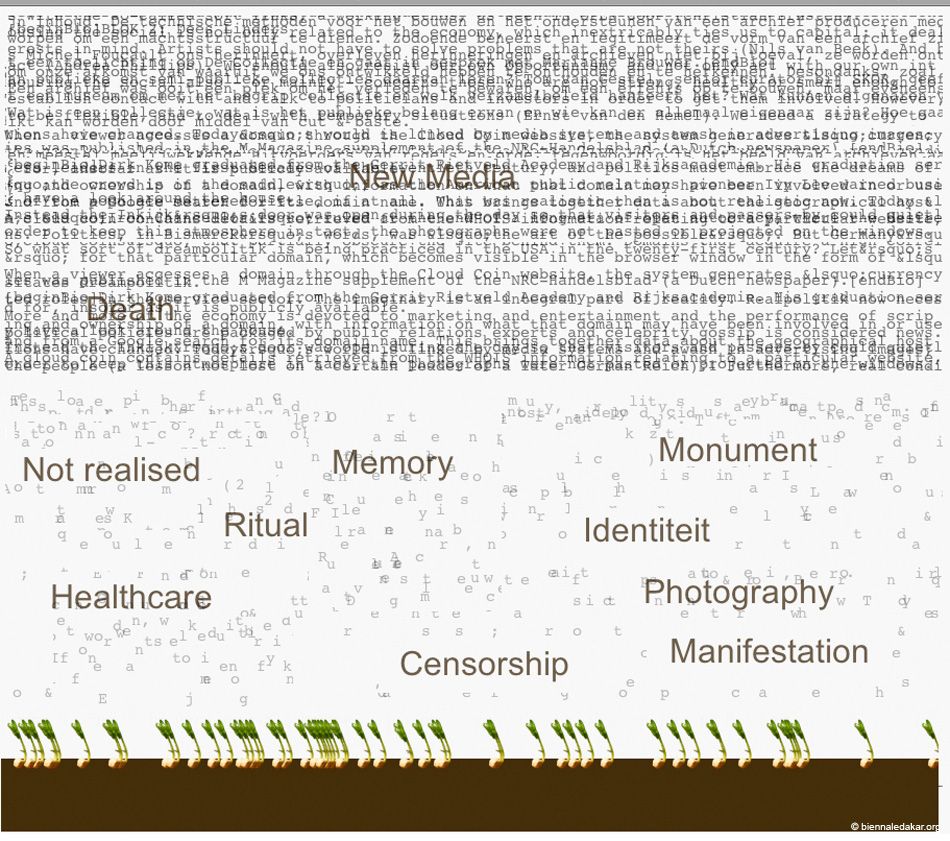

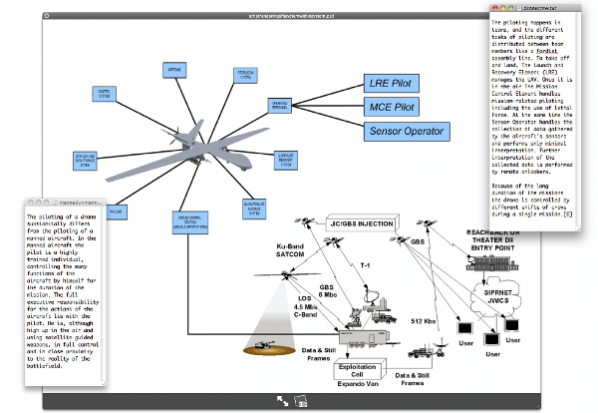

Piratbyrån and Friends traces the stories of cultural sharing and affinity-building among the activities and values of the members of Piratbyrån (The Bureau of Piracy). This Swedish artist/activist group was established in 2003 to promote the free sharing of information, culture and intellectual property. The exhibition presents screenings, installations and artworks by founding and more recent members, keen to tell the story of the group on their own terms. It features newly commissioned work by artists Geraldine Juarez and Evan Roth, and a new networked audio collaboration which mediates their rich archive and foregrounds the role of piracy as an agent of innovative disruption and cultural transmission.

“The specific character of friendship as a form of social relationship is that it does not presume a permanent interaction. Friendships are a type of serial solidarity. The story of friendship is a story of meetings.” Viktor Misiano – The Institutionalization of Friendship.

Piratbyrån have always resisted clear definition. Created on the Internet as a loose friendship group with a shared commitment to media and piracy in the shifting ecologies of digital copyright law, Piratbyrån operated through a number of different identities. From the #discobeddienti IRC chatroom, to the infamous Pirate Bay, to the determinedly analogue SX23 bus trip to Manifesta 7, and their subsequent disbandment in 2010, Piratbyrån consciously cultivated an air of mystery and intrigue around their many activities.

Piratbyrån have always had a particular commitment to the value of friendship as a shelter for culture and a space to understand, imagine and experiment as a community from the edges of the Internet.

The exhibition features newly commissioned sculptures and installations by artists James Cauty, Geraldine Juárez and Evan Roth and a screening programme that includes Steal This Film by Jamie King and Piratbyrån and Friends by Geraldine Juarez.

Tapecasts (2013-2014) – Piratbyrån and Friends

SK23 Suit (2008) – Lina Persdotter Carlsson / Piratbyrån

S23m Manifesta Bus Trip (2008) – Piratbyrån & Simon Klose

S23x Belgrade Bus trip (2008) – Piratbyrån

Polymarchs posters (1980-1990) – Jaime Ruelas

Sharing is Caring Map (2008) – Sara Wolfert / Mathias Tervo / Piratbyrån

Kopimi Totem (2014) – Evan Roth

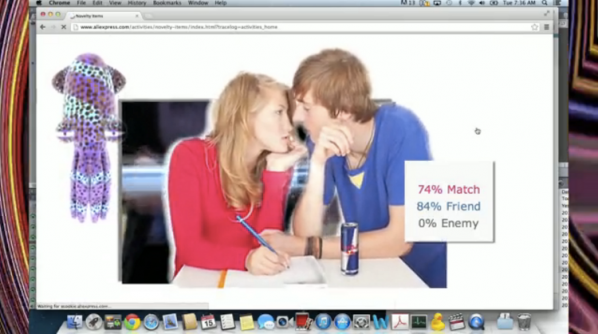

Torrent Tent (2014) – Geraldine Juárez

Riot Chat (2014) – Palle Thorsson

Smiley Riot Shield 2 (Second Edition) and PB2 (2014) – James Cauty

Piratbyrån (The Bureau for Piracy) was started by a bunch of hacking, coding, reading, listening, philosophising, clubbing, rioting, carding, chatting, loving, slacking people in 2003 as an antidote to Hollywood’s representatives in Sweden – Antipiratbyrån.

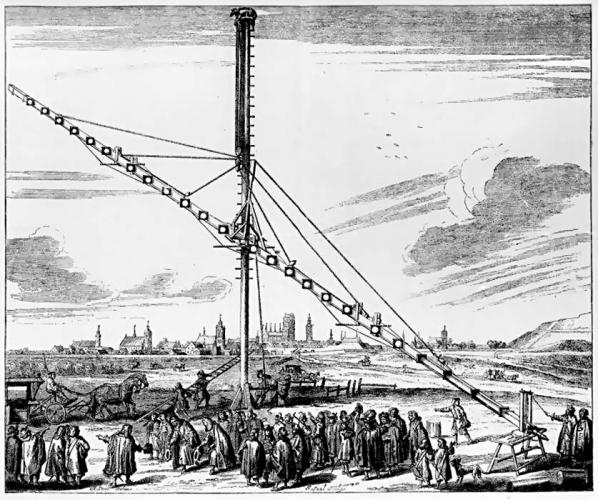

In 2007 – after having kickstarted the Swedish debate over file-sharing, which by the time had become a major issue in the previous years national election and after having created The Pirate Bay as a side-project that became the world largest file-sharing system – the people from Piratbyrån had grown tired of the file-sharing debate and its endless repetitions of for-or-against, legal-or-illegal, payment-or-gratis. At the last day of April in a Walpurgis fire on the top of the highest mountain in Stockholm the masked members burned the remaining copies of a book on file-sharing they had published some years earlier and declared the debate dead. The video documentation of this ritual, set to the soundtrack of KLF’s “What Time is Love”, found its way to the Indian Raqs Media Collective group who was just about to curate the next Manifesta biennial in Bolzano, Italy.

The loose network of Piratbyrån, now loaded with 7000 Euros of art budget and a sizable amount of cash from selling Pirate Bay t-shirts, decided to purchase, renovate and decorate a 1970s city bus, stack it with 23 people, and head down south.

The ongoing relation with the bus – named S23m/x/k respectively for each trip – would later make an exodus from the exhibition in Italy to head across Eastern Europe and end up at the trial against Pirate Bay. It became one of the most significant undertakings of Piratbyrån and shaped their thoughts on the tensions between digital abundance and crowded space, collective decisions and freedom of choice, and that which can be copied and that which can’t. The bus became a line of flight from the collective subject that had been built, a subject which was very associated with The Pirate Bay and also with Swedish politics, including the Pirate Party.

While nothing was really the same after the bus had returned, Piratbyrån formally lasted until 2009, when the tragic death of one of the founding members – Ibi Kopimi Botani – defined the end of an era. The Internet had already transitioned to another phase and it is not until now, and enough time has passed, that we as a culture are ready to reflect on what exactly happened during those years.

Piratbyrån always had an implicit friendship with the KLF. They share the same historical web of connections and share a similar trajectory, but their activities are shifted in time by roughly a decade. The only contact between the two is a response from Bill Drummond when Piratbyrån sent a link to the documentation of the Walpurgis ritual. It read:

> Thank you for your email.

> I have just read the text at the link.

> I enjoyed it and understood it.

It is probably good that they didn’t exist at the same time because the gap in time gives the relation an infinite unresolvable tension of unfulfilled connectivity and unlimited possibilities.

James Cauty

For Piratbyrån, James Cauty’s personal work resonates with the themes of abundance and rarity, presence and absence, functionality and waste, control and chaos, and draws on the same symbolic language that mixes clarity with suggestion. There is also a similar urge to *stir things up* and *stick ones nose where it doesn’t belong*.

Evan Roth

Speaking of stirring things up, FATLAB was for Piratbyrån another one of those instantly recognisable friends that had never met; the art group that Piratbyrån never became, the “the unsolicited viral marketing wing of the open-source movement”, the graffiti crew of the World Wide Web. FATLAB was born when the file-sharing debate was buried and the new web 2.0 era transformed the web.

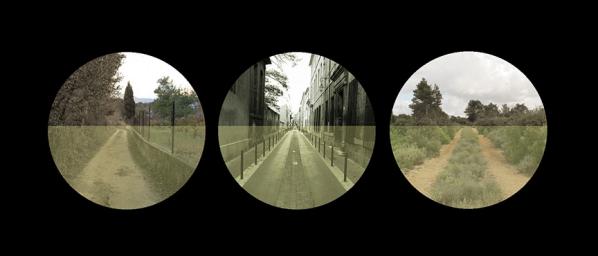

Evan Roth, co-founder of FATLAB, has made a piece for the exhibition that in a subtle but direct way captures the concept of KOPIMI; how meetings and connections leave traces and makes you a carrier of ideas and information, sometimes without you even recognising it.

Jaime Ruelas & Polymarchs

The soundsystem collective Polymarchs and their illustrator Jaime Ruelas, probably happily unaware of the existence of Piratbyrån, embodies a scene in Mexico where piracy has always been a way of life and a mode of existence. They have materialised, expressed and lived what was only hinted at in glowing screens up in Sweden. Having outlasted all of the above mentioned collectives and managed to stick together for decades, they also highlight both the potential strength and – as a contrast – the fragility of so called “confidential projects”; those moments when friendships turn into expressive units and the borders between the intimate and the public are blurred.

Geraldine Juárez

Last but not least, Geraldine Juárez is the reason this exhibition came together at all. She began to read the Swedish-language blogs of Piratbyrån members through Google translate – whose mistranslations made them sound like they came from the near future instead of the near past, until she finally came into contact with Piratbyrån by translating updates from the trial – or Spectrial, as it was known – into Spanish. Now she returns the favor of time-travelling by re-awakening Piratbyrån one last time, to allow their archive to again live up, their ideas to be carried over to others and perhaps even some sense made from what happened, although these things can only be interpreted, misunderstood and re-appropriated – never explained.

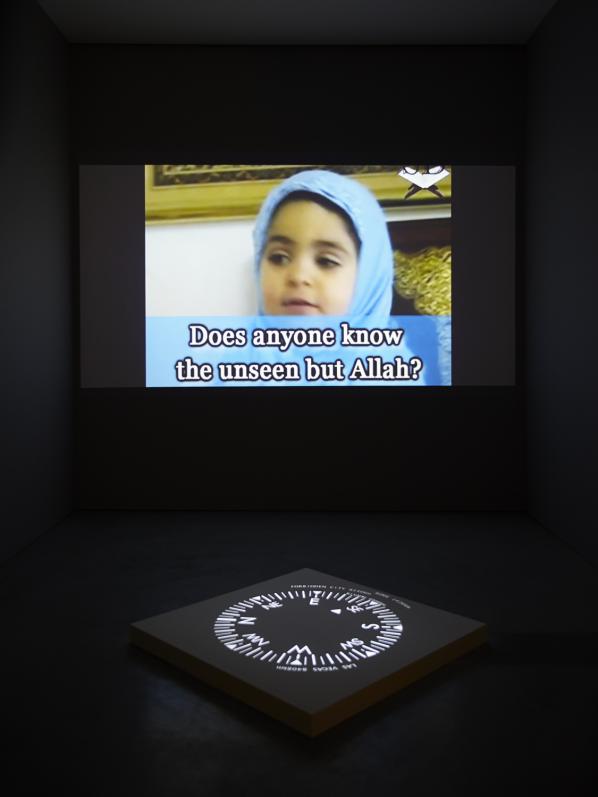

Inside the tent that she has crafted for the exhibition – a torrent for piracy as the last shelter of culture – there will be a collection of tapes prepared and circulated by Piratbyrån and friends, perhaps giving some seed for thoughts and guidance in the process of excavating the archive of Piratbyrån.

About co-curator Rachel Falconer

Rachel Falconer is a curator, writer and producer working at the intersections of technology, the media and contemporary art. She currently holds the position of Head of Art and Technology at SPACE and runs the art and technology programme at The White Building and SPACE MediaLab. She is Co-Editor at Furtherfield and a founding member of the collective Hardcore Software.

Her curatorial practice is hybrid and interdisciplinary in approach and her current activity and research focuses on the pathologies surrounding social spaces and human behaviours engaged with networks and new technologies.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England

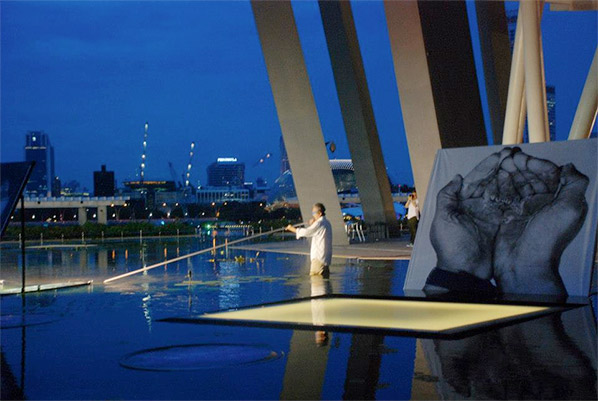

The artist and curator Art Clay was born in New York and lives in Basel. He is a specialist in the performance of self created works with the use of intermedia and has appeared at international festivals, on radio and television television in Europe, Asia and North America. His recent output focuses on large media based performative works and spectacles using mobile phone devices. He has received prizes for performance, theatre, new media art, music composition and curation. As an educator, he has taught media and interactive arts at various art schools and universities in Asia, Europe and North America including the University of the Arts in Zurich. He is the initiator and Artistic Director of the ‘Digital Art Weeks International’ and the Virtuale Switzerland.

Eva Kekou: Could you tell us about your work and what inspires you?

Arthur Clay: The question about inspiration has been posed to me before and most often in the moment when people first see the program that the Digital Art Weeks (DAW) is offering. As an artist I am very much inspired by the every day. I think it is important to be aware of the things around you and by so doing, my artwork seems to have more of a present day dialogue and the events I curate more to do what is actually going on in the society around me. So basically, everything and nothing and all the things in between inspire me. There are no rules, but with a lot of effort to try and come closer to things might be the one I apply the most.

On the one hand, I am a practicing artist and most of this work is concerned with sound. On the other hand, I believe that curation is an art in itself and requires a high level of creativity. It is easier for me to make an artwork in comparison to harmonizing a group of artworks. The two meet in the fact that I grounded the DAW projects in order to provide a platform for my own work and that of others, who think in like minded ways.

EK: You were the curator for the Augmented Reality exhibit “Window Zoos & Views” in collaboration with the participation of the School of Digital Media and Infocomm Techology from Singapore Polytechnic. On the project site, it mentions that the main element of the project was inspired by an image of a car driving down Singapore’s legendary Orchard Road. Could you tell us a bit more about this and the project?

AC: As DAW Director, I am confronted with the same situation each time we bring the festival: Representation and integration. By representation is meant that we have institutions both public and private that act as stakeholders and in turn expect a high level of visibility; talking about integration is much more complex, because there are many levels of integration that must be addressed. First off, the festival structure demands that we integrate local artists into the program along with the international artists participating. Integration of local artists can also mean or entail a high level of knowledge and skill transfer. We do all this during what we like to call the “Exploratory Phase”, which is basically entails dropping the DAW team into a unfamiliar city and making every effort to make it familiar. This includes becoming aware of the general culture the festival will address, how digital that culture is, the art and non art spaces that will become the stage of the festival, and of course trying to find out who is doing what in terms of arts and technology.

To get back to your question about the image of the car driving down the street, the most important element of integration is becoming aware of what is going on in the world of things in which the festival is to be presented. The car we are talking about was a car whose windshield was plastered with cartoon stickers. So, imagine you’re self-sitting at the wheel of that car driving down Singapore’s Orchard Road. It is a really surreal experience; the stickers take on a kind virtual elelment as it floats down Orchard road. The image sparked my imaginations and the AR Parade project was born, which was a very important part of the “Window Zoos and Views” exhibit. Basically, the AR Parade mimicked the effect of the stickers on the car window, but instead of a car windshield, we used an iPhone app to view the images. It was very cool, popular on the street and got a lot of clicks.

EK: There were various artists in the festival showing Augmented Reality art as installations. This included artists such as Tamiko Thiel (DEU), John Cleater (USA), Will Pappenheimer (USA), Lily & Honglei (CHN), Marc Skwarek (USA), Lalie S. Pascual (CHE), John Craig Freeman (USA), and Curious Minds (CHE). It must of have taken a lot of time and energy to organize this, especially the technological aspects of the project. How difficult was it to set all of this up?

AC: In one word: impossible. It is new area of technology, a new approach to curating art, and above all you are dealing with a non-art public – basically anyone who is on the street. That is a big challenge. Add to it the new type of management skills that such an international project work requires and I think you are close to the impossible that I am referring to. For such exhibitions, “Management 2.0” skills are a necessity. The artists, the tech people, and the curators and admins meet and work solely in virtual space. So there are no walls, no tables, and there is no going for coffee together after the meeting. It is a different world from all sides.

Another interesting aspect of this work is that you have to develop a feel for the city and develop a dialogue with it. For the Hong Kong show we did for SIGGRAPH Asia, Monika Rut and I spent about a week working on site, visiting the different areas of the city to check things out and to get a feeling for which works should go where and why. We travel with a lot of special equipment so that we can make tests on site and produce a mock up of the exhibition and test how the experience of viewing the exhibit will be. It is very inspiring but exhausting work and the dialog between Monika and I helped greatly in making all the decisions. Basically, we get to know the cities we are working in quite well and the kick back is, you get to know where the best coffee houses and local restaurants are.

EK: Why hold the DAW in Asia, and what kind of differences do you experience culturally when working in Asia compared to working in Europe?

AC: The DAW is at home in Asia and much of our curating has to do with having visitors get pro-active. This means that it is not just about looking at an artwork, it also entails actually touching the artworks in many cases. In Asia, the museum visitors are not that schooled in museum etiquette. They like to touch things and this is great for the kind of work we like to do. Things break, but it is kind of a “I Like” thing for us.

The other aspect to consider is that you have a language barrier, because no one is going to understand anything if it is not translated. Here, it is also important to know that the approach Europeans take in terms of explaining artworks, does not really come over so well in Asia. Things are often inspired by poetics of nature in Asia and are much less conceptual than works coming from Europa.

Last but not least, the role of size also plays a large part in Asian arts. When a dynasty was at its peek, it produced very large artworks, monuments etc. So size is historically a sign of wealth and prosperity in Asia. When a dynasty fell, they produced much smaller works. So the bigger the better, so to say. For a European artist this is completely meaningless, however, bigger artworks have more visibility. So when you are curating group exhibits in Asia that artists from diverse countries, it is a challenge to keep balance in terms of impact of the works.

EK: Getting back to There DAW AR Float Parade, which was the first of its kind and celebrated as the coming age for Augmented Reality art. Could you tell us more about this aspect of the festival’s project and how it turned out?

AC: Knowledge transfer plays a major role in getting a project like the AR Parade to work. The DAW has an “OutReach Program”. This is a program that invites creative leaders from around the world to hold workshops before or during the festival. The contents of the AR Parade in Singapore were the results of a workshop with the AR artist John Craig Freeman and the Curious Minds group. John Craig dealt with the technical details and the bootstrapping a group of twenty-five creative industry students from the Singapore Polytechnic. The members of the Curious Minds art group hung around, integrated the group into the DAW, taught the students about public interaction, and came up with how to go about actually making the AR Parade happen and come to life.

The proof of a good project for me is when it takes on its own life on after its initial presentation. After the Singapore DAW, the AR parade went to Hong Kong and in 2015 it will be shown marching down the Bahnhofstrasse in Zurich as part of the Virtuale Switzerland festival – the world’s first festival “virtual biennale” that focuses solely on virtual artwork. For this we want to go a bit deeper into the creative industry world and see if we can act as modern alchemists and pick up on the float parade from New York and turn Miss Kitty into an artwork by shifting context from the real to the virtual.

Live- Performance “Beads are the Breath of the Landbridge “ with 1st Nations artists, Peter Morin. (DAW Singapore 2013)

EK: What is your view regarding the social contexts of the DAW?

AC: Basically, we are concerned about things and we make an effort to improve things that are within our reach to improve. For the festival in Taipei that will take place in 2015, we are really trying to make people aware of the role of creativity in general. Artists are highly creative people and the world really needs good ideas as well as a more social approach. We try to provide an answer to the question: “How is what we do of benefit to the society in which we are operating?” We think this should be more a question that businesses should be asking themselves. The future needs fewer companies who are “profit first, prosperity second” and more social entrepreneurships that embrace social needs as part of their business model.

EK: Could you tell us what themes and aims we can expect from of the DAW project in the future?

AC: We are off to Seoul, South Korea in 2014 and the theme there is “Creativity and Convergence”, which is a hot topic in Asia, because the government feels that innovation is intimately connected to being creative and thinking out of the box. I think they’re thinking of what makes the West tick and in an odd and ironic way to imitate – which is not exactly creative, but then again I have lot of respect for Asia and admire the work ethic of Asian people. So I think they will do well by addressing these themes. In 2015, we are off to Taipei and the theme (working title) there is “ImagiNation” and here we are trying to run a kind of “Skills-Festival” and platform creative businesses and the approaches that they have taken. It is a new approach and if you think about what Beuys said, “Everyone is an artists”, we might stretch it a bit and also say “everything is art.” At least this is the start and interestingly enough we are working with groups from the labor department in Taiwan, with knowledge transfer departments of universities, and with spin off and start up companies from Switzerland. It is very exciting and really what the DAW is about: creating a platform for research and experiments in social-cultural context.

Digital Art Weeks International

The DAW INTERNATIONAL’s is concerned in general with the bridge between the arts and sciences in cultural context with the application of digital technology in specific. Consisting of symposia, workshops and cultural events, the DAW program offers insight into current research and innovations in art and technology as well as illustrating resulting synergies, making artists aware of impulses in technology and scientists aware of the possibilities of application of technology in the arts.

The Virtuale Switzerland

The Virtuale Switzerland is a biennale for virtual arts. It focuses on the use of public space and mobile communication technologies, inventing “playful” new strategies to coax the public into the festival as “real” visitors with a unique experience of the virtual. The Virtuale Switzerland encompasses Artworks using Augmented Reality, Urban or Location Based Gaming, and Digital Heritage applications. It is interdisciplinary in nature, bridging areas such as art and technology, digital heritage and tourism, as well as digital culture and art mediation.

The end of boom and bust ended with the credit crunch. Following the global financial crisis of 2008, the Eurozone crisis has produced technocracy and poverty rather than democracy and wealth. Reactions to these failures of monetary policy are informed by technology as never before, from austerity being imposed thanks to an Excel spreadsheet bug to the rise of the anti-statist cryptographic currency of Bitcoin.

Against this backdrop of monetary failure and technological critique, _MON3Y AS AN 3RRROR | MON3Y.US is an ambitious online survey of net art depictions and critiques of money and its institutions curated by the pseudonymous curator “Vasily Zaitsev”. As well as the work from 70 or so artists invited to participate an open call for work increased the number of pieces in the show in total to around 200. I only consider the invited artists here, but the work in the open call section is well worth looking at as well.

The show web site has a simple HTML interface, starting with a single image and a pull-down menu of other works. Disable your pop-up blocker and you’re ready to start.

Miron Tee’s “Shame” is the image that fronts the show, an image of a dollar modified to show George Washington peering out nervously from behind the oval frame in the center.

Dominik Podsiadly’s “Joy to ide” starts the pull-down menu with a flowing grid of Euro signs on a blue background to the sound of “Ode To Joy” playing backwards. It’s an all-over, closed temporal loop of the kind that animated GIFs exemplify and encourage, the Euro falling forever.

Nuria Güell’s “How to expropriate money from the banks” is a more direct action based work of culture jamming explaining presented in a well laid out document in the style of HSBC’s First Direct brand.

Paolo Cirio’s “Loophole for All” makes offshore tax havens, those loopholes in taxation regimes that allow corporations and the super-rich to avoid repaying society, available to everyone through a web site interface.

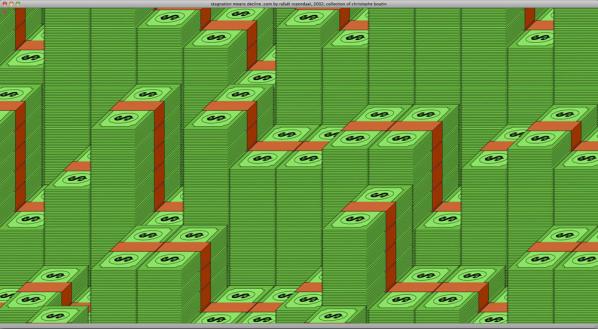

Rafaël Rozendaal’s “Stagnation Means Decline” is a screenful of geometric pixel-art dollar bill stacks that fill the screen with their edges only to be obscured by new columns like an economic game of Life.

Filipe Matos’s “Crash” is an undulating animated monochrome concrete poetry American flag with the stars made from the letters of “me” and the stripes as “you”.

Adam Ferriss’s “paper$hredder” is a Vimeo video clip of American dollar bills speeding by faster and faster until they dissolve into a blur.

Aaron Koblin + Takashi Kawashima’s “Ten Thousand Cents” is a composite image of a hundred dollar bill crowdsourced by paying people a cent to paint each piece through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service.

Maximilian Roganov’s “When the Mao was small, he worked for CIA” is a looped animated GIF colour 3D scan of a dollar bill, polygonally glitched or possibly crumpled over time.

Dave Greber’s “Self Portrait With Dog” video is aptly titled, apparently taking place as the custom graphic on a Visa Mastercard.

Agente Doble | UAFC’s “Watermark will not appear on purchased artwork” is a million dollar blank artwork if you email them and purchase it, otherwise it’s just a url on a blank web page.

JUST DO IT’s “Fifty Euros Inside/Fifty Euros Outside” are animated GIF loops of fifty Euro notes pulsating as if to sound waves on an oscilloscope.

Mitch Posada’s “$$$” is a Flash video of Silicon Graphics-era-style VR models of skeletons exploding and morphing into their constituent polygons while texture mapped with Deutschmarks.

Emilio Vavarella’s “Money Complex” is a tube map-style world map with banknote-collage continents and a key for numeric labels that can be zoomed in on by moving the mouse to reveal their often incongruous labels. It’s one of the more complex works in the show art historically and conceptually.

Lorna Mills & Yoshi Sodeoka’s “Money2” is a Vimeo video loop collage of roughly extracted elements from videos of commodity fetishism, fire and death.

Fabien Zocco’s “Cloud” is a generative composition of black dollar signs scattered up over a yellow background over time like a plume of smoke.

Jasper Elings’s “Territory” is an animated GIF loop of a dollar bill flag blowing in the roughly simulated wind on a white background. It’s not the only such piece in the show.

Robert B. Lisek’s “FuckinGooglExperiment” is online statistical analysis code that tries to correlate the change in Google’s stock price with changes in their PR strategy. It also uses the excellent Fluxus livecoding environment.

Alfredo Salazar Caro | TMVRTX’s “How to make money on internet remix” is a tightly tiled video loop of a rotating stack of dollar bills in a lava-lite-like flow of colour psychedelia.

Anthony Antonellis’s “How to make money on the internet” is simply that rendered block of spinning virtual hundred dollar bills, plucked from the era of RenderWare and VRML.

Gustavo Romano’s “Pieza Privada #1” is another piece of net art for sale at a specific price, with a carefully described contract and application form.

Tom Galle’s “One Million Dollars For iPhone” is an app available on the iTunes Store that allows you to count a virtual million dollar wad on your iPhone.

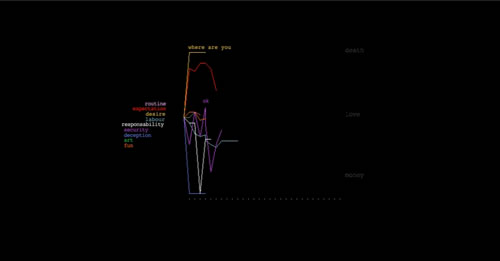

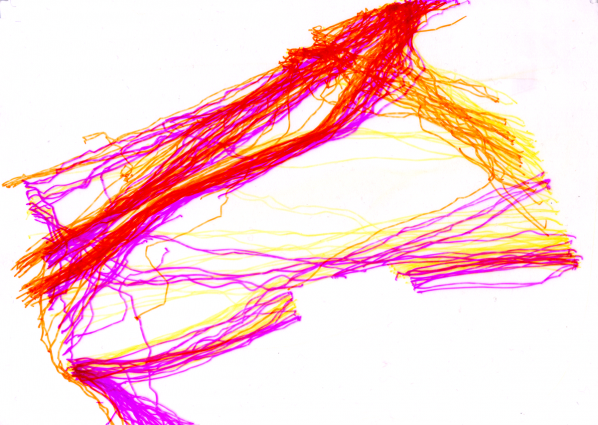

Geraldine Juarez’s “Love Not Money” tracks the associations of various words with “death”, “love” and “money”. I had to Google this one: it’s a Processing visualisation of a personal stock market tracking the artist’s conceptual assets over six weeks. I love it.

Nick Kegeyan’s “C.R.E.A.M. (Cash Romney Eat A Lot of Money)” is simple, direct and effective video burst of an American news interview subject morphing into a cloud of falling texture mapped dollar bills.

Dafna Ganani’s “Apple Dollar Explosion” is another descriptively titled piece, a Maya-looking apple texture mapped with a dollar bill spinning against a grey background then exploding into its constituent polygons.

Haydi Roket’s “$” takes a dollar bill portrait and literally deconstructs it by pixelating it in increasingly primitive ways, first as 4-bit grey patterns, then in monochrome ANSI characters, alternating to inverse video and changing the contrast to give a flickering effect.

Jennifer Chan’s “Infinite Debt” is a video of a twenty Euro not being dipped in batter and fried mixed in with a collage of clipart images and video on the cynical economics of contemporary art and consumerism.

Frère Reinert’s “Money as a waste of time” is a deliberate excercise in futility; a blurred, zoomed in silent video of the MacOS X SBOD on a white backdrop.

Cesar Escudero’s “Captura de pantalla 2013-03-08 a las 21.46.23” is a Mac OS X desktop image of a gas masked protester who appears to be reaching for a folder named “$$$$$$$”.

Jefta Hoekendijk’s “Money Is Data” is an animated GIF loop of a glitchily texture mapped virtual fifty Euro note in artificial colours.

V5MT’s “¥€$ or N0T” is a rap video or Designers republic album cover-style animation of monumental metal morphing currency symbols made from struts and spheres like newton’s cradles or molecular diagrams.

Addie Wagenknecht’s “How To Make $$$$$” is a grid of money counterfeiting video tutorials, which are apparently a genre. Playing all at the same time they become an all-over aesthetic rather than incitement to a crime.

Gusti Fink’s “infinite loop of money drowning in water oil” is a slow, monumental simulation of a platinum visa card sliding into dark liquid that the camera pans over as if it were a sinking ship.

Marco Cadioli’s “You are here” shows globe and landscape maps constructed of dollar bills, with a pin or map icon to show your place in the economy.

Keigo Hara’s “Making Of Fake Bills” is more halftoned (or possibly shape grammared) dollar bills.

Jan Robert Leegte’s “Currency Graph” shows European flag yellow bars over a European flag blue gradient background. It’s a mutated and abstracted evocation of news information graphics aesthetics in CSS and JavaScript.

Ellectra Radikal’s “Disolved €uro” is a flickering autotraced, find edged and glitched animated zoom into a hundred Euro note that renders it spatial and architectural.

Paul Hertz’s “5,000,000$” it the purest glitch art piece in the show, rows of corrupted and miscoloured banknote imagery that looks like nothing so much as classic street art.

Aoto Oouchi’s “It’s all good” is an uncanny New Aesthetic 3d rendering of liquid or possibly mirrored texture mapped banknotes pouring from a wall.

Kim Laughton’s “Landscape” is a rendered and collaged landscape of banknotes, resembling nineteenth century engravings of dramatic landscapes thanks to the inconography and texture of its source material.

Andrey Keske’s “Tell Me What You Want” is a search engine-style text box prompt that shows the economic coercion inherent in neoliberal use of technology by only allowing you to finish one word beginning with “M”.

A Bill Miller’s “3xpl0d3m0n3y” combines a grainy analogue glitch aesthetic explosion of a dollar bill into waveform stripes into a black space of drifting Matrix-green dollar signs.

Martin Kohout’s “Watching $100 Note Unveiling Video” has a ChatRoulette look, with the unseen unveiling causing a small smile to break out on the depicted viewer’s otherwise affectless face.

Marc Stumpel’s “pH0r 7|-|3 L0\/3 0Ph /\/\0|\|3’/” is a glitched and colourised monochrome television popular music performance from the age of mass media. Again I had to Google it but the song is ‘For the love of money’ by The O’Jays.

Benjamin Berg’s “$(0x24)” (the hexadecimal number that represents the dollar sign in ASCII) is a colourful and stripy glitch animation that resembles test cards, 8 and 16 bit graphics, and even woodcut as it breaks down.

LaTurbo Avedon’s “$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$” is an ambient modern html5 animtion of the avatar-artist reclining on money texture-mapped couches floating up and down a Google image search page for the word “millions”.

Nicolas Sassoon’s “BILL” is a flickering green screen terminal or slow scan TV-style rendering of a 500 Euro note that plays with the visual language of digital images: the letters and stars are highly pixellated but the backdrop to them is a smooth gradient.

Curt Cloninger’s “i want KANDY” loops images of a dancing sniper camouflaged figure montaged with dollar bills and fruit over a more slowly changing background collage of the american flag, a dollar bill, and fruit making a post MTV-styleguide image of the military-economic-entertainment complex.

Systaime’s “ʞooqǝɔɐɟ Dollars” video portrays a world where curvily rendered dollar bills rain over an amateur video of tourists at a beach with a sky of quickly cycling Facebook pages.

Erica Lapadat-Janzen’s “Money Troubles” is a PhotoShop Pop Dada montage of exploitatively normative female beauty and monetary and drug excess that subverts the imagery of the fashion pages.

Milos Rajkovic’s “Mind Wheel” is a wonderfully Gilliamesque collaged animation depicting a mental wage labourer.

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion’s “Cutting Grass” depicts the pointless and trivial labour that video games such as “The Legend Of Zelda force players to engage in for unrealistic rewards such as gold coins and rubies so they can get on with their quest.

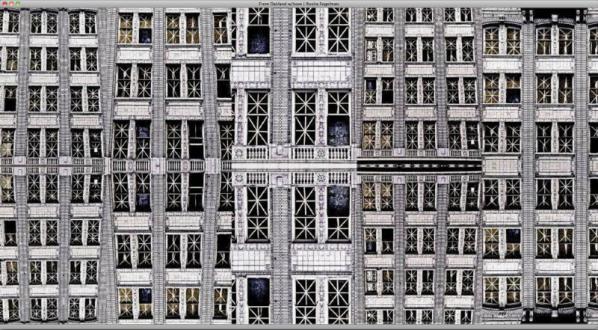

Rozita Fogelman’s “From Oakland w/Love” is a point-and-click kaleidoscopic archtitectural portrait of gentrified Bay Area architecture.

Georges Jacotey’s “am I enough political now” is a Chatroulettish video selfie of an augmented reality Euro flag and symbol drawing and dancing session.

Δεριζαματζορ Προμπλεμ Ιναυστραλια’s “Major Problem” is a rendering of a stack of dollar bills as seen through heat haze or under water, rippling and undulating against a white background.

Lars Hulst’s “0 €uro” is a rendering of a zero Euro note.

Nick Briz’s “a return to secularism” is a video documentary of twenty dollar bills being printed with the words “a return to secularism” flashing over it, framed by a repeated loop of the words “in God we trust” being crossed out on a dollar bill where they were added in the 1950s.

Jon Cates’s “MØN3¥-Δ$-3ɌɌɌØɌ” is a Classic Mac monochrome bitmap or fax aesthetic PDF essay for the show and an exposure of the print on demand economics of that essay in the same style.

León David Cobo’s “Conversation With Machine” has a 1990s broadcast graphic feel, showing the soundwaves of the feedback of a conversation with Siri asking it for money in Euro blue and yellow.

Guayayo Coco’s “Money | GLıɫcʜ ᴬᴺᴰ GLıɫɫɛʀ” is a video of a journey through a VRML-style virtual environment of discrete polygonal objects texture mapped with dollar bills, corporate logos and more abstract patterns with a radio channel-surfing soundtrack.

Vince Mckelvie’s “MONEY” is a reactive interactive deconstruction of a hundred dollar bill into a grid that reacts to the viewers’ mouse movement, revealing pulsating colours behind. It’s a good example of how suitable html5 is for this kind of thing.

Ciro Múseres’s “YOU HAVE WON” is a classic net.art style HTML bomb of overlaid text and links with content from financial web sites such as Barclays, Halifax and Santander that continuously adds and removes layers in different shades red, black, blue and green text to make new compositions.

Adam Braffman’s “Money Loading” is an animated GIF of the frame of a 100 dollar bill with a “Loading…” speech bubble in the centre. It makes the show’s themes of absent and delayed wealth more obviously explicit.

Rollin Leonard’s “Portrait of a NetArtist” is an two-frame animated GIF of the artist naked in the bath with bundles of fake hundred dollar bills with which they are lighting their cigar.

Thomas Cheneseau’s “100€ sequence” is a grid of glitched sections of a hundred Euro note that moires with colour as you scroll it. There’s a link to the facebook album that constitutes the actual work, and it works much better as a clickable album than as a static single image.

Yemima Fink’s “This is not money” is an abstract postmodernist collage of graphical quotations from the counterfeit-resisting elements of banknotes that is both witty and a very effective defamiliarisation of the iconography of banknotes and the power that they represent.

Mathieu St-Pierre’s “Untitiled” is a glitched jpeg of a dollar bill that in its straightforward application of glitch aesthetics makes the most direct link between them and the economic “glitch” of 2008.

Kamilia Kard’s “Amazon VIP girls” is the lone tumblr in the show, with an aesthetic that is either post-internet or pre-Google depending on how old you are applied to the supposedly perfect clothing models used by web sites.

José Irion Neto’s “Untitled” is a glitched banknote that turns JPEG artefacts into Klimt patterns.

There are definite historical trends and formal themes within the included work. Polygonal, texture-mapped, 90s-style VR-style objects that spin or explode. Net art and functional web sites that track or create financial and legal entities and transactions. Looped animations of textures, rendered flags, or video detournements. The imagery of accumulation, consumption, and destruction, always ironically. Imagery and symbols presented in simple loops fast or slow for contemplation. Graphs and maps of real and imagined economic signifiers.

In terms of genre, _MON3Y AS AN 3RRROR | MON3Y.US includes classic VR and video art, more modern GIF loops, textual and institutional net.art, glitch art, even some New Aesthetic. The language of computer graphics, texture mapping and polygons, allows the imagery of banknotes to be defamiliarised and deconstructed. Less often, personal experience and iconography displace the cultural imagery of wealth, consumption and debt.

This historical, formal and genre coverage of the variety of artworks included in the show comprehensively illustrates the chosen theme of “money and error”. This creates its own genre and lineage for the included artworks, which gain by comparison to their newly identified peers. They also contribute to the social and economic critique of the show. It’s a very successful balancing act, which the simple interface and presentational strategy of the show’s curation are key to achieving.

_MON3Y AS AN 3RRROR | MON3Y.US is an almost overwhelmingly successful in its comprehensive review of net art’s critical depiction of and engagement with money. By taking a technologically simple but historically, conceptually and logistically ambitious approach to net.curation for net.art it demonstrates the effectiveness and lasting value of net art’s contributions in this area and the power of online thematic curation to draw together and contextualise this value without giving in to the often perceived need for offline institutional underwriting.

Featured image: Sam Meech, Punchcard Economy, 2013. Photo courtesy of FACT.

The new exhibition “Time & Motion” at FACT in Liverpool, UK, takes the pulse of punchcard protocol and creative capital in our own “Modern Times”.

The exhibition Time & Motion: Redefining Working Life at FACT Liverpool is a collaboration between FACT and the Creative Exchange at the Royal College of Art – an initiative which looks at how arts and humanities researchers can work with industry to effect digital innovation. Rachel Falconer reviews the exhibition in the context of the paradoxical dynamics of cognitive capital and the changing landscape of the labour market.

Now self-employed,

Concerned (but powerless),

An empowered and informed member of society

(Pragmatism not idealism),

Will not cry in public,

Less chance of illness,

Tires that grip in the wet

(Shot of baby strapped in back seat),

A good memory,

Still cries at a good film,

Still kisses with saliva,

No longer empty and frantic like a cat tied to a stick,

That’s driven into frozen winter shit

(The ability to laugh at weakness),

Calm,

Fitter,

Healthier and more productive

A pig in a cage on antibiotics.

Fitter Happier, Radiohead.

The frantic quest for the elusive Shangri-La of work/life balance is a neurotic luxury afforded only to the always-on, hyper-connected generation of precariously unstable home office workers[1] in our hypercapitalist society. The working rhythms of this emergent class of “precariat” [2] are far removed from the forensically prescribed scientific management resulting from the time and motion studies associated with Taylorism at the beginning of the last century. This shift in working patterns generated by the digital revolution is the primary focus of the exhibition Time and Motion, Redefining Working Life currently at FACT, Liverpool. From an archival, filmic view of the automated, (Western) industrial factory labourer to contemporary portraits of the global information worker’s state of perpetual imbalance and non-stop, hyper-connectedness [3] the participating artists expose the – often contradictory – ecologies of labour, consumption, and the conditions in which they operate. The exhibition also marks the collaboration between FACT and Creative Exchange at the Royal College of Art – an initiative which looks at how arts and humanities researchers can work with industry to effect digital innovation and confront contemporary modes of production.

Taking the archival stimulus of time and motion measurement as its title and industrial work patterns as a starting point, the exhibition Time & Motion is the latest in a series of exhibitions and symposia addressing immaterial labour and new working patterns in the age of globalisation and creative capital.[4] Rather than following the well-trodden path of casting the figure of the artist as digital labourer, or attempting to portray an expansive, post-colonial view of nomadic, labouring diasporas, Time and Motion reflects a more subversive and fragmented approach to the politics of work, rest and play in the global information economy.

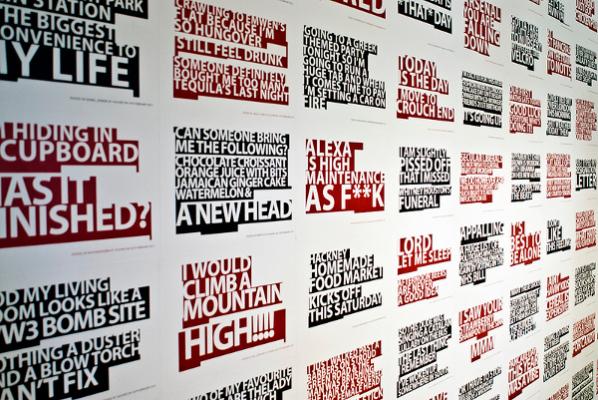

Sam Meech’s Punchcard Economy is at once a homage to the textile industry and a recognition of the contemporary precariat. With more than a symbolic nod to northern England’s textile heritage, Punchcard Economy consists of a machine-knitted reinterpretation of the Robert Owen’s 8-8-8 ideal work/life balance.[5] The piece was produced on a domestic knitting machine using a combination of digital imaging tools and traditional punchcard systems. During a residency at FACT last year, Meech collected punchcards from visitors detailing their working hours. This data was then translated into a knitting pattern which was used to generate the final work – a banner depicting the contemporary working day. Any hours worked outside the eight-hour day appear as a glitch within the fabric. This banner – historically a symbol of the working class and trade unions – also denotes the fragmentation and blurring of national class structures in the era of globalisation.

The move towards a flexible, open labour market has not eroded the class system completely, but a more fragmented global class struggle has emerged. The “working class”, “workers”, “proletariat” are terms that have been embedded in our (Western) culture for centuries, and used as badges of honour by some, and terms of derision by others. By incorporating a large cross-section of working society under one banner, Meech has literally – in stitching different socio-economic groups together into the very fabric of the working day – rendered the once potent archaic class signifiers as little more than evocative labels.[6]

“75 Watt” by artist Cohen Van Balen and choreographer Alexander Whitley also riffs on the trope of the long fought for 8 hour working day. Deriving its title from a quote from Marks’ Standard Handbook for Mechanical Engineers: “A labourer over the course of an 8-hour day can sustain an average output of about 75 watts”, the film is a subversive ballet of the complex and often skewed relationships between production, consumption and distribution in the post-industrial age. The film features a group of Chinese labourers working an assembly line, (playing on the stereotypical “Made in China” trope). The object they produce, however, has no logical use. The purpose of the exercise is simply to choreograph the combined movements performed by the labourers in the manufacturing process. The work examines the nature of mass-manufacturing on differnt levels; from the geo-political context of hyper-fragmented labour to the bio-political condition of the human body on the assembly line. Echoing the Taylorist ideal, here we see engineering logic taken to its conceptual extreme; through the scientific management of every single movement we witness the passage of factory labourer to a man-machine.

By shifting the purpose of the labourer’s actions from the efficient production of objects to the performance of choreographed acts, mechanical movement is reinterpreted into dance. The artists ask: “What is the value of this artefact that only exists to support the performance of its own creation? And as the product dictates the movement, does it become the subject, rendering the worker the object”?

This operatic construction line also points towards the ultimate failure of scientific management. Taylorism was always dictated by the needs of capitalist exploitation, but in its pure form it proved to be inefficient in drawing on workers’ talent and potential. In time the bourgeoisie recognised the inadequacies in Taylorism, and Taylorist methodology was mostly withdrawn by the 1930s. However, this was not the end of time and motion measurement. More recent management theories include Theory X and Theory Y introduced by Douglas McGregor in the 1960s.[7] Contemporary Taylorism takes the form of the Lean practices introduced into major departments of the British civil service (including HMRC, DWP, MOJ, and MOD). Workers incorporate “efficiency savings” as an integral part of their job, and work priorities are monitored by the soft panoptic gaze of non-hierarchical “collaborative practice”. Here,workers time their work processes, identify forms of waste, and propose changes in work practices. This “bottom-up” approach goes hand in hand with the new language of management – as managers morph into “leaders”. As efficiency savings are made from workers’ suggestions, the “leaders” try to enforce impossible targets, and decide whose post is next to be eliminated – hence the creation of the precariat. As part of the precariousness of employment, workers not only worry about losing their jobs, but also have to propose measures which, in the name of efficiency, might put them out of work. Added to this the increasing automation of work and the burgeoning AI scene, where does human cognition stand in all of this?

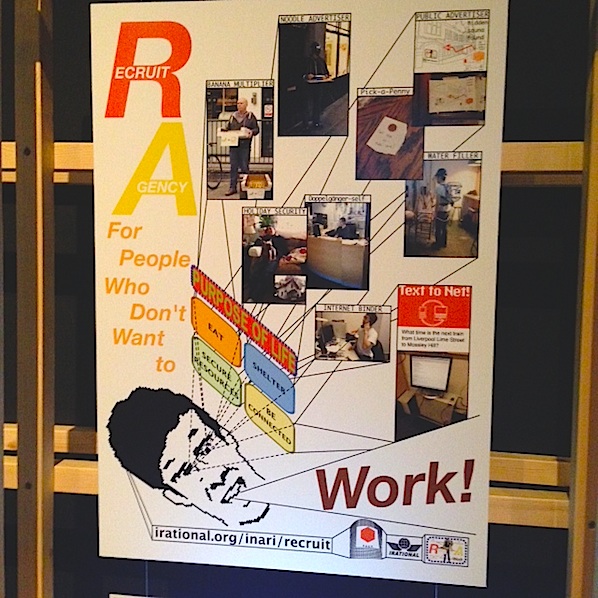

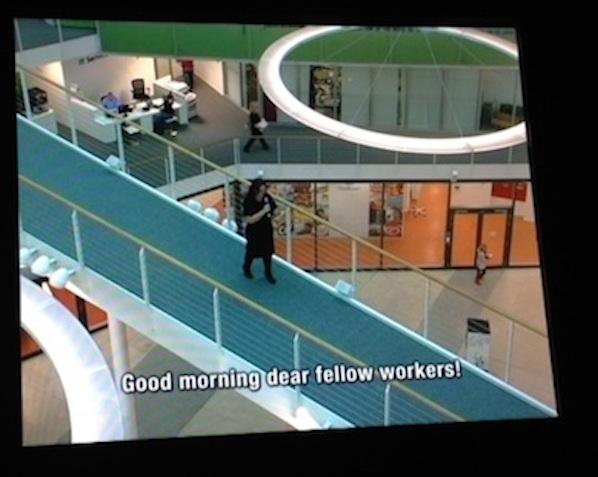

Inari Wishiki’s set of ludicrious alternative employment models (such as Banana Multiplier), are in reminiscent of the subversive, performative models of the Fluxus movement. Inari’s online work Recruit Agency for People Who Don’t Want To Work dramatizes this staging of an alternative labour market. The website includes documentation of a series of performances by the artist exploring the premise that with the proliferation and development of technology, we as humans have lost our place in the world of work, and yet still need to appear to be “useful” in order to earn a living.

Recruit Agency For People Who Don’t Want To Work is a set of systems which allow people to engage in the act of commerce while abandoning “all the meaningless rituals of having to be useful in order to earn money”. In INARI TRADING CARD, the artist documents the way in which “essential” workers function as a social infrastructure. He observes that “money was naturally following those workers according to their essential motions, unlike that of workers who seek after money”. These set of performances are an ironic counterpoint to the hyper-efficiency promoted by neo-Taylorism, and point towards the informal norms that are in tension with the industrial time norms still permeating social analysis, legislation and policymaking in the globalization era.

In his text “The Value of Time Spent” in the accompanying catalogue to the exhibition, Mike Stubbs supports this strategy of “design for disassembly” and novel values of exchange. Stubbs maintains that these alternative ecologies of exchange are necessary in order to allow us to question how we spend our time, and for us to lay bare the new patterns of professional fulfilment and social relations inherent to our hyper-mediated society.

The classic distinction between the workplace and the home was forged in the industrial age, and when today’s labour market regulations, labour law and social security systems were constructed, the norm was a fixed workplace. This model has now fragmented and crumbled and the term social factory, popularized by Tiziana Terranova and others, is applied to describe this shift “from a society where production takes place predominantly in the closed site of the factory to one where it is the whole of society that it is turned into a factory – a productive site”.[8] The production is one of value, where the collective efforts of intelligence and creativity are networked, controlled and exploited. Labour takes place everywhere, and the discipline or control over labour is universally exercised. But policies are still based on a presumption that it makes sense to draw sharp distinctions between the workplace and home – and between workplace and public space. In a tertiary market society, this model is obsolete, leaving the information worker increasingly pressurized and isolated.

One of the recurring themes in Time & Motion is this hybrid and compromised locus and infrastructure of the work place. Harun Faroki’s moving image work A New Product presents an insider’s view of the paradoxical construction of so called “fluid” working environments. He describes his new film as: “Scenes from meetings within a company which advises corporations how to design their offices — and the work done there. The film shows that words are not just tools, they have become an object of speculation.” In this work, he stages the brainstorming sessions of a business consultancy specialising in the design of workspaces, offices and new concepts for mobile work hubs. The resulting seductive imagery of the ideal workspace is an exercise in brand development pastiche rendered as pseudo video game.

Time & Motion also stages a co-working space, developed by the RCA CX team, which weaves together venue, audience, workspace and digital space – presenting the entrance space of the gallery space into a live research ‘lab’. Visitors are encouraged to participate in the research, interaction and interventions, and workshops, salon discussions, and hacking and making sessions are woven into the experimental fabric of the exhibition.

The ‘CX Co-Working Space’ features three design interventions. The first, Hybrid Lives, features video work by Karen Ingham and an interactive installation responding to data traffic, dressed with ‘co-working furniture’. Where Do You Go To? is a wall-mounted moving freize showing the output from an app, co-designed with a group from the BBC, with the mission to connect remote workers through exchanging, Snap-chat-like (pre-hack) images of desks and workspaces. According to Ben Dalton, one of the main developers, this sharing of ‘desk context’ helps form a synergy of ‘headspace’ between remote workers.

Taking its cue from Frances Cairncross’s 1995 “The Death of Distance”, where the compelling vision that, over time, the communications revolution would release us from geographic locations, the project illustrates how digital space has redefined our working lives. However, for all its good intentions, this gesture towards remote solidarity seems to be muddying the new principles and rhythms of work with Taylorist and later Fordist ideals of panoptic surveillance and somehow stands in direct opposition to the emancipatory rhetoric of convergence culture.

Time and Motion focuses primarily on a particular demographic of labourer (generally the global information worker), and paints the picture of a tertiary lifestyle which involves multitasking without control over a narrative of time use, and habitual fractured thinking – where non-stop interactivity (a digital version of Taylorist motion) is crack cocaine for the drones. For this category of workers, the workplace is everyplace – diffuse, unfamiliar, a zone of insecurity. We are left with a “thin democracy” in which people are disengaged from political activity except when jolted into consciousness by a shocking event or celebrity meltdown witnessed virally on Youtube during office hours. As more work and labour takes place outside the pre-determined workplace – in the hybrid environments of cafes, trains and across the domestic landscape – the very idea of a work/life balance seems like an alien ideal to aspire to.In an open tertiary society, the industrial model of time, and the bureaucratic time management of factories and office blocks, breaks down. There is no stable time structure and we are increasingly losing our grip on our own time. Time and Motion at FACT interrogates the impact of this fragmentation on the aesthetic forms of contemporary art, and contemplates how artists might offer a critique of our neo-Taylorist predicament.

Read and learn how to solve a Rubiks Cube with the layer-by-layer method. It can be learned in an hour.

Featured image: Screenshot of Apodemy by Katerina Athanasopoulou

Eva Kekou interviews Katerina Athanasopoulou about her film Apodemy commissioned by The Onassis Cultural Center on the theme of Emigration for Visual Dialogues 2012, and her hybrid art practice of live action, animation and film. In 2013 Athanasoppulou won the Lumen Prize, described by the Guardian as “The World’s Pre-eminent Digital Art Prize”. She works as an Animation Director, collaborates with other artists and companies, and is an Animation Lecturer at the London College of Communication.

What is your background and what brought you to London?

I studied Painting at the School of Fine Arts of Aristotle University in Thessaloniki. My work involved large canvases painted in a serendipitous way, building layers, erasing and restarting, seeing where my lines were going to take me. I was frustrated by the stillness of the final piece, longing to recreate the gesture in time that had created it. At the same time, I was passionate for cinema and animation so I tried it out in my own computer at home. In a way, I discovered animation for myself, as there was no film nor digital element in my course. That meant that there was no right and wrong way to go and it was such a joy to be producing moving images, to be able to finally paint in time! My first films were digital cutouts and manipulated live action. The big change came when I arrived in London in 2000 to do an Animation MA at the RCA, where suddenly completely new creative possibilities appeared. Short film festivals were also a source of great inspiration, places to meet like-minded filmmakers and watch films all day long.

What’s the effect of English education in your work and in the way you appreciate art?

When I became a student in the UK, I was at the same time delighted and terrified by the informality of the teacher-student relationship, like addressing your tutor by their first name. I was really impressed by the enthusiasm for research and for the creative journey itself. Process becomes a major part of the work and that frees you from concentrating only on the outcome. I saw how Animation can be enlisted in very different ways, from a more commercial manner to very left-field experimental practices so that was an exciting new point of view for me. At the same time, the early 2000s were a time of conflict between analogue and digital practices – which of course has not quite gone. As an educator myself, I love the intensity of the way that students debate their work, so the English system of education still very much inspires me.

What was your creative practice up to the Lumen Prize.

Since 2002 I have been making short experimental films that have been screened in film festivals and galleries, my process being one of playfulness and embracing chance. I like to try out different ways of creating moving images, and I try to make each film follow a different road, even though it’s very tempting – and at times fruitful – to revisit old concepts. In the last three years I have developed a big interest in Architecture and how that can be depicted in time, through 3D, 2D and live action. Animation for me is Alchemy, I combine elements together, in textured space and time and see what happens. These experiments some times involve diving into live action that I have captured on location, and other times are about creating that space digitally.

Animation Installation is a field I’m fascinated by at the moment, devising ways of materialising the digital element, of making it even more about light and shadow. My latest film, Triptych 1, was made especially for the facade of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and reimagines it as built of interconnecting corridors.

Talk to us about the theoretical and philosophical background of Apodemy.

Apodemy was commissioned by the Onassis Foundation (Stegi) on the theme of Emigration and the Economic Crisis. It was to be part of an Art Show in an old archaeological park in Athens, called Plato’s Academy Park, where the philosopher is believed to have taught. The title of the Installation was Visual Dialogues so I was drawn to Plato’s Dialogues where I discovered the metaphor of the human soul as a birdcage. I was very keen to instil in the work philosophical elements related to the space itself. With migratory birds being one of my initial ideas about the piece, the solution of a travelling birdcage in an abandoned half-finished city became apparent. The marble arms were part of Plato’s birdcage metaphor, where he describes how, as we grow up we fill our mind/birdcage with ideas/birds. When we need to recall something, we put our hand in the cage and grab a bird. I imagined those hands to be aggressive, so they became statue fragments carried by cranes that eventually mar the trolley cage’s journey. Theo Aggelopoulos inspired me with his images of a Lenin statue traversing the river and of a single arm, floating accusingly yet innocently. In times of political upheaval we like to break down our past heroes, in an attempt to cleanse ourselves of mistakes. Only that sometimes those past leaders still come back to haunt us.

What techniques did you use?

I designed the city on the computer in 3D and then started to drive cameras inside it, discovering it on the road, like I was exploring a real landscape. The film was built like a documentary, following the migration journey of a cage that is also a trolleybus, the yellow kind that I was riding in Athens when – in the late nineties – everything was promising.The construction industry ground to a halt when the crisis took hold so, today, many buildings remain unfinished and look like birdcages themselves. After the City was built, I started making the birds and the bus. Then I moved it inside the city, following a broken road which eventually leads to the fall. The entire film developed through trial and error, it was my first 3D film and I had limited time and resources. But restriction breeds creativity and, in the two months that I had to complete it, I tried to make a film designed in a minimal but impactful way.

What does the Lumen Prize mean to you and how can such a recognition make a difference in your work and life?

Winning the Lumen Prize was a great honour, especially amongst so many great works from entirely different platforms. The prize revolves around fine digital art and encompasses film, installations, interactive work, print, sculpture, collage. Amongst such a plethora of forms, it meant a lot that Apodemy was awarded, both in terms of my digital animation practice, but also as it’s a film that’s about the collapse of my country of origin. The Lumen Prize show has already been to New York and will also be part of the Digital Symposium at Chelsea College of Art and Design in March, as well as in Hong Kong in June. It’s wonderful that Lumen is propelling the film further forwards, and it’s been great to meet some of the other artists involved. Seeing the works by Nicolas Feldmyer, Kalos&Klio, Margarita Koulikourdi, Vasileios Chlorokostas and others has been very inspiring.

What draws you to animation?

Through cinema, we immerse ourselves in different waters, achieving a kind of immortality. One could argue that also happens whilst reading, or listening to music – yet somehow film combines literature and poetry and music too and almost all the senses get involved. What’s more interesting for me is the connection between moving image and the imagined: it’s almost like we dream other people’s visions and we physically try to make that disconnection from reality by favouring watching films in dark rooms. The cinema I’m interested in is one of spectacle, that transforms reality into a surreal play, that explores light and shadow and looks for monsters under the bed. At the same time, I’m currently very curious about taking animation off the screen and applying it in space, by projecting rooms, objects, corners. For me, there’s no greater magic than instilling life in the inanimate and create moving worlds that don’t depend on cameras and actors – what’s in your head can be made real, a real that’s still beautifully elusive and chimeric, that doesn’t contain all the answers but asks exciting questions.

What are your future plans?

I have been working on an experimental narrative of an obsessive mother that cocoons her children, which may work as a single screen work or perhaps as an installation that includes a film. I’m also researching the Architecture of Melancholy, which lies somewhere between cabinets of curiosities and abandoned homes. I always have several experiments on the go, it’s really about finding the right time and opportunity to commit to a project. As delightful as animation is, it takes time to complete, but it also means that ideas may have time to mature and not be rushed. As long as my ideas keep me entangled, I’m happy.

See Katerina Athanasopoulou’s work online at kineticat.co.uk

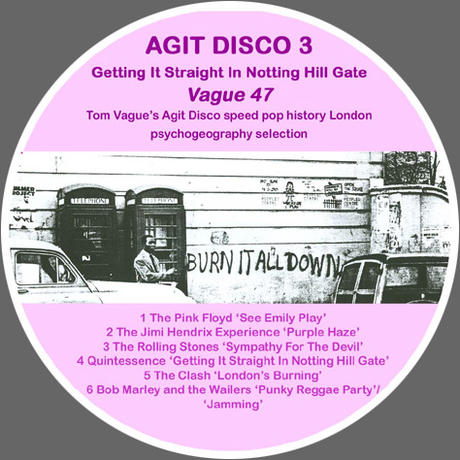

Marc Garrett reviews Stefan Szczelkun’s book Agit Disco. He is an artist and author interested in culture and democracy. In the early Seventies he was fortunate to be part of the Scratch Orchestra and has since been involved with a series of artists collectives. His doctoral research into the Exploding Cinema collective was completed at the RCA in 2002. Recently his collaborative project Agit Disco was published as a Mute book in 2012. He has been on the Mute magazine editorial board since 2009, and currently working on photographic and performance projects.

“Just cause we can’t see the bars

Don’t mean we ain’t in prison.”

Kate Tempest (2009) [1]

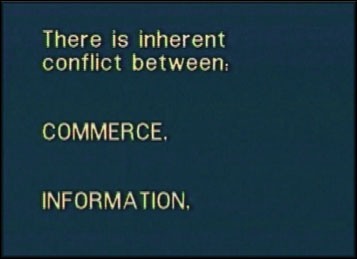

The subtle and not so subtle domination by market interests of cultural production and dialogue denies us all access to a wide spectrum of creative expression, especially those that engage in subjects that conflict with the agendas of those in power. Agit Disco by Stefan Szczelkun combats this contemporary trend by focusing on music, politics, DIY culture, and freedom of expression. In doing so he starts to redress the lack of representation across the board for those in grass roots culture and working class lives, whose freedoms to have a voice in society are so commonly restricted.

The future does not look good for those who value cultural and social diversity; who look for a variety of activist histories and experiences to be seen and represented on their own terms. The UK government is changing university regulations so that private companies can become universities. This means tutors will end up replacing educational courses once devised with the public good in mind with modules designed for maximum profit. Luke Martell, a critic of the marketisation and privatisation of education and lecturer of Sociology at the University of Sussex, says “This will lead to a different content to education. Critical thinking is being replaced by conformity to cash. Money-spinning management and business courses are expanding and lower-income adult education is being closed down.” [2] (Martell 2013) Already, most researchers, academics and those in professional fields of practice mainly work within insider frameworks, “there is a qualitative difference between the conditions of people living in marginalized communities and those in middle-class suburbia.” [3] (Smith 2012)

The knock on effect of an unquestioning culture of compliance with the ‘free market’ is enormous. How ironic it is that the term ‘free market’ is attributed with so much value and (a presumed) logic when in actuality it constrains people’s freedoms and makes those who are already rich even richer. Because the politicians are not effected by the results personally, and because it also serves their interests, they have handed over their social responsibilities to these market systems. The neoliberal defaults that caused the financial crisis are untouched by our democratic processes. These out of reach, distant power systems are fixed towards property bias and occupy and govern our everyday experiences. How does freedom of expression fit into this and on whose terms?

“The more our physical and online experiences and spaces are occupied by the state and corporations rather than people’s own rooted needs, the more we become tied up in situations that reflect officially prescribed contexts, and not our own.”[4] (Garrett 2013)

Agit Disco offers a breath of fresh air, in the fug of the developing marketisation of everything. It presents grounded examples of difference that contrast with the dominating view of entertainment systems. Published through Mute Books in 2012, it features 23 playlists put forward by 23 different writers, artist and activists. It began as a set of mixed CDs and images, each chapter includes annotations and illustrations. Its contributors are Sian Addicott, Louise Carolin, Peter Conlin, Mel Croucher, Martin Dixon, John Eden, Sarah Falloon, Simon Ford, Peter Haining, Stewart Home, Tom Jennings, DJ Krautpleaser, Roger McKinley, Micheline Mason, Tracey Moberly, Luca Paci, Room 13 – Lochyside Scotland, Howard Slater, Johnny Spencer, Stefan Szczelkun, Andy T, Neil Transpontine, and Tom Vague.

Mostly from working class backgrounds the contributors were invited to focus on politics and music, and share memories relating to what the tunes meant to them at the time. In the preface Szczelkun states, his selection of contributors comes from his own worldview and personal contacts. Anthony Iles, in his introduction says most who have contributed “are closely associated with anti-authoritarian politics and DIY culture.”[5] (Iles 2012) Contributors offer insights into the connections between their music and the politics of the time. Louise Carolin says, “When I was a teenager in the ‘80s I lived through one of the golden ages of British chart pop, listening to music that was by turns, political, danceable, challenging and entertaining. I attended CND rallies, marched against South African Apartheid, ran the feminist group at school and went to GLC-funded music festivals.”[6] (Carolin 2011)

What adds depth to Louise’s story, as with the rest of the contributions is that many readers feel connected with these histories, and I am one of them. It highlights an indigenous, working class culture and their personal struggles in a period when neoliberalism was in its early stages of world domination. To say that these are merely anecdotal or subjective would completely miss the point. It calls for an awareness and understanding about people giving an account for themselves in relation to music, politics and their social contexts on their own terms.

Just as it is important to ask contextual and critical questions of why a particular artwork is being shown at a certain venue or seen in an art magazine. It is also necessary to observe who published Agit Disco and why? It is no coincidence that it’s a Mute publication, Szczelkun has been on its editorial board since 2009, and has written various articles, reviews and interviews for Mute.

Agit Disco resonates with Mute’s dedication to DIY culture. Indeed, Mute has an excellent history in independent publishing alongside its DIY methods of production. Mute’s earliest incarnation used Financial Times’ pink paper, broadsheet printing cast offs. Later on a traditional magazine format. From 2005 onwards it moved onto its online site, and developed a publishing platform that allowed the publication of its POD (Print On Demand) magazine. [7] The design and production of Mute and its platforms have come a long way enabling a pamphlet-like production and distribution, echoing Thomas Paine’s own DIY releases of the Rights of Man.[8]

DIY Culture (and its distribution channels) offer a vital alternative to mainstream frameworks and their dominating hegemonies as a way to route around the restrictions to content, freedom of thought and free exchange. We have to contend with networked surveillance strategies initiated by corporations and state secret services. Censorship exists in many forms and recently there has been a rise of self censorship by workers and academics worried about losing their jobs if bosses see their interactions on Facebook or similar Web 2.0 social networks.[9] And the worrying antics of Britain’s GCHQ, in collaboration with America’s National Security Agency (NSA), targeting organisations such as the United Nations development programme, the UN’s children’s charity Unicef [10] reveal a greater investment in the surveillance of everyone, and the downgrading of privacy and fundamental human rights.

The credo that Anyone Can Do It reached a mass of individuals and groups not content with their assigned cultural roles as disaffected consumers watching the world go by. Like the Situationists, Punk was not merely reflecting or reinterpreting the world it was also about transforming it at an everyday level. Sadie Plant states that with the “emergence of punk in the late 70s […] lay the possibility of a threatening political response to the vacant superficiality of contemporary society.” [11] From this, a whole generation of diverse artists emerged; and through their practices they critiqued the very society they lived in, questioning authority and the authenticity of established politics, language, art, history, music and film.

Has the process of appropriating people’s civilian personas, and then replacing their social contexts with a corporate role as consumer created a more selfish world, lacking compassion for others and less interest for societal and ethical change? Ubermorgan discussed in a recent interview with Stevphen Shukaitis that people are in a state of ‘mediality’. “What we refer to as reality very often is just mediality, and also because that’s how human nature often prefers to observe reality, you know, via some media.” [12] Perhaps our constant interactions through different interfaces of proprietorial frameworks distances ourselves to what is important. In the 21st Century demonstrations and civil disobedience are policed intensively, and even though much of contemporary activism exists on-line. The frontline, or the heart of politics is still mainly a physical matter; it is still in our streets, our homes, our bodies, in our neighbourhoods and communities.

As Oxblood Ruffin a Canadian hacker and member of the hacker group Cult of the Dead Cow (cDc) and the founder/director of Hacktivismo, said “I know from personal experience that there is a big difference between street and on-line protest. I have been chased down the street by a baton-wielding police officer on horseback. Believe me, it takes a lot less courage to sit in front of the computer.” [13]

So Agit Disco reminds us that music is a vital way of both bringing people together in a space, story telling and communicating with each other, sharing what is happening with people’s lives. It is usually at the moment of censorship that we then realise how essential this freedom of expression stuff really is. For instance, nine months after Islamic militants had taken over in northern Mali they announced that all music is banned. “It’s hard to imagine, in a country that produced such internationally renowned music as Ali Farka Touré’s blues, Rokia Traoré’s soulful vocals and the Afro-pop traditions of Salif Keita. […] The armed militants sent death threats to local musicians; many were forced into exile. Live music venues were shut down, and militants set fire to guitars and drum kits. The world famous Festival in the Desert was moved to Burkina Faso, and then postponed because of the security risk.” [14] (Fernandes 2013)

In her article The Mixtape of the Revolution, Fernandes says that in Africa many rappers are “speaking boldly and openly about a political reality that was not being otherwise acknowledged, rappers hit a nerve, and their music served as a call to arms for the budding protest movements.”[15] Regarding Egypt, the rapper Mohamed el Deeb in an interview with Fernandes said, “shallow pop music and love songs got heavy airplay on the radio, but when the revolution broke out, people woke up and refused to accept shallow music with no substance.” [16] Music, politics and grass roots dissent are concrete expressions and an essential part of our collective freedoms. Alongside this, independent publishing as an alternative voice to the marketed franchises that dominate our gaze, sight, ears and minds, are needed more than ever. Yet, independent voices are being silenced and whittled down by wars, oppression and the neoliberal created financial crisis and its resulting austerity cuts.

What is to become of us if we lose our skills of discernment and slump into a homogenous consumer class, to define ourselves solely through marketed stereotypes and ideologies?

Agit Disco offers a festival of dance and dialogue for independent minded individuals and groups around the upturned burning car in the barricade against the coming zombie apocalypse.

It has been fun listening to all of the playlist contributions provided in Agit Disco. Below is my own Agit Disco playlist. You are welcome to add your own playlist in the comments section below (with links)…

Damien Dempsey – ‘Dublin Town’ (2000)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=brhO8pqTNHU

Asian Dub Foundation – ‘Modern Apprentice’ (2000)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zgtWhjaOgQ4

Dan Le Sac & Scroobius Pip – ‘Great Britain’ (2010)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YeV2cExvnMI

Kirsty MacColl – ‘Fifteen Minutes’ (2005)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MSQrH3JUQ2s

Jeffrey Lewis – ‘Do They Owe Us A Living?’ (2007)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jWU-W0SzVE0

The Pop Group – ‘Forces of oppression’ (1979)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Txzmbu6o-gg

Kieron Means – ‘I Worry For This World’ (2005)

https://play.spotify.com/track/6AI2QujkrP6B2nfIUK55lY

Robyn Archer – ‘Ballad on Approving of the World’ (1984)

https://play.spotify.com/album/3hNQY8q9sO3M0R6es2d3ka

Robyn Hitchcock – ‘Point it at Gran’ (1986)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_HFkimK9FAU

Sound of Rum – ‘End Times’ (2011)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9dWPe7Au68A

Silver bullet – ’20 Seconds to comply (final conflict)’ (1990)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=24b6pYGT9MM

Maze – ‘Color Blind (Featuring Frankie Beverly)’ (1977)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COY4gKLwV2I

Akala – ‘Bullshit’ (2006)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mxpxpQ7j8Sg

Sarah Jones – ‘Your Revolution’ DJ Vadim (2000)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E62SZ1CmBOI

Julian Cope – ‘Soldier Blue’ (1991)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8dGOr-JpOmI

June Tabor – ‘A place called England’ (2009)

https://play.spotify.com/track/3YB6sSlLfB8kmMrrm5COKX

For over 17 years, Furtherfield has been working in practices that bridge arts, technology, and social change. Over these years, we have been involved in many great projects and collaborated with and supported various talented people. Our artistic endeavours include net art, media art, hacking, art activism, hacktivism and co-curating. We have always believed it is essential that the individuals at the heart of Furtherfield practice in arts and technology and are engaged in critical enquiry. For us, art is not just about running a gallery or critiquing art for art’s sake. The meaning of art is in perpetual flux, and we examine its changing relationship with the human condition. Furtherfield’s role and direction as an arts collective is shaped by the affinities we identify among diverse independent thinkers, individuals and groups who have questions to ask in their work about the culture.

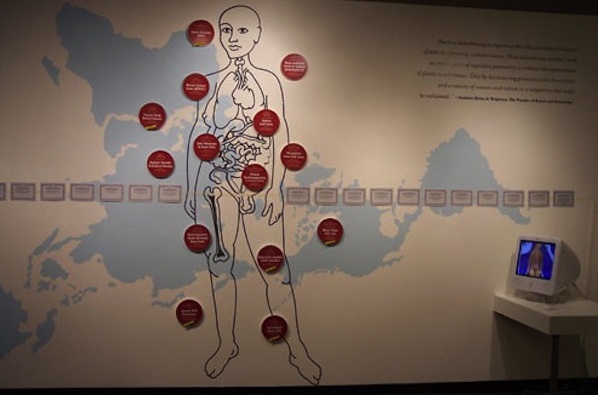

Here I present a selection of Furtherfield projects and exhibitions featured in the public gallery space we have run in Finsbury Park in North London for the last two years. I set out some landmarks on the journey we have experienced with others and end my presentation with news of another recently opened space (also in the park) called the Furtherfield Commons.